ELLINGTON SYMPHONIC A GUIDE TO THE ORCHESTRAL

SYMPHONIC ELLINGTON

https://www.loc.gov/item/2023867653/.

“This man had the most prolific output of any genius I can think of, and that includes the old masters. Let’s not forget what a great genius he is.”

RAY NANCE, TRUMPETER, VIOLINIST, AND SINGER 1

1 Ray Nance, Duke Ellington Society New York Chapter, 1975, on sound cassette Sc Audio C-471 side 1, New York Public Library, https://www.nypl.org/research/research-catalog/bib/b10830136

INTRODUCTION

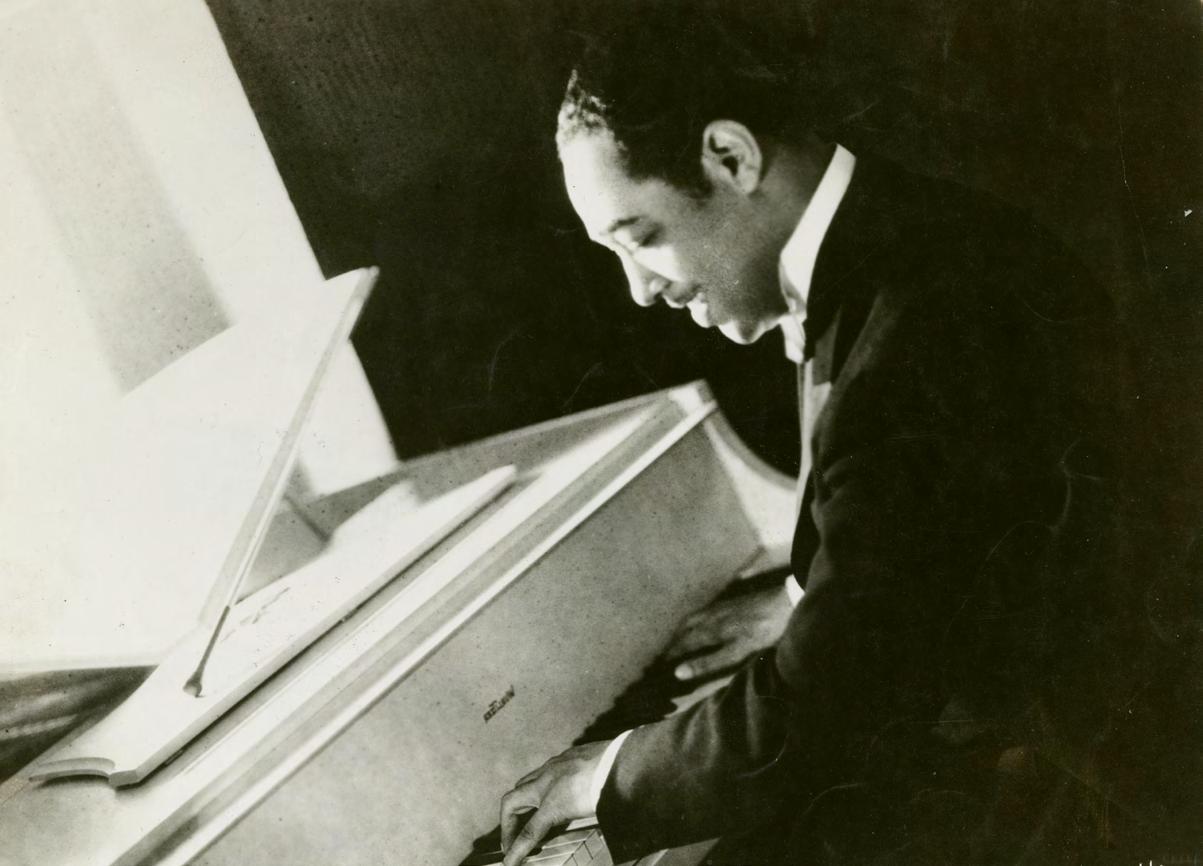

Edward Kennedy Ellington—known since childhood as “Duke”—was one of the most important composers, pianists, and bandleaders in American history. Revolutionary in his approach to rhythm, harmony, and orchestration, Ellington’s works enjoyed broad success from the 1920s, especially as performed by his signature big band of hand-picked jazz musicians. As time went on, the music of Duke Ellington audaciously entered the realms of ballet, opera, Broadway, sacred music, and the symphony orchestra.

Though his work grew out of the improvisatory frameworks and player-driven ethos of jazz, the highest compliment Ellington paid to music he loved—including his own—was to call it “beyond category.” Such defiance of artistic boundaries is characteristic of Ellington’s

approach to his work with the symphony orchestra and his exploration of extended forms. These two trajectories are intertwined, as Ellington often took the invitation to write for or perform with a symphony orchestra as an opportunity to create large-scale suites.

As scholars such as David Schiff have observed, “symphonic Ellington” is a broad category that encompasses a range of works, including those that Ellington originally wrote for symphony orchestra (The Golden Broom and the Green Apple, Celebration, and The River), those written for the Ellington Orchestra alongside symphony orchestra (Grand Slam Jam, Harlem, and Night Creature), and pieces that were originally written for the Ellington Orchestra and later arranged for the symphony (Black, Brown, and Beige;

2 Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. “Duke Ellington at the piano” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1930 - 1960. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/ items/89528d46-2d88-13f5-e040-e00a180606f2

New World A-Comin’, and Selections from the Sacred Concerts). Both Ellington and his orchestrators tend to take one of two approaches to Ellington’s symphonic works: a “concerto grosso” approach where a jazz band is included as a separate ensemble in dialogue with the symphony orchestra, or a more integrated approach where the material is adapted to symphonic forces, with or without the addition of big band instruments.

Delving into Ellington’s catalog of works and vast discography, the collaborative nature of his artistry becomes immediately apparent. Across a half-century of the Maestro’s recordings, one can enjoy the marvelous interpretations of Ella Fitzgerald, Teddy Wilson, Ben Webster, Max Roach, Charles Mingus, and many others. In the 1930s, Ellington began a decades-long association with fellow composer-arrangerpianist Billy Strayhorn, with whom he produced many of his best-known works. (This artistic partnership is the central focus of the Lush Life concert program discussed later in this catalogue.) During and after Ellington’s lifetime, dozens of arrangers additionally worked with his titles, many of which are scored for the symphony orchestra and performed around the world to this day.

Collaboration was a core part of Ellington’s artistic DNA; as he articulated, “You can’t write music right unless you know how the man that’ll play it plays poker.” In all of Ellington’s work with symphony orchestra, then, there is an inherent tension between his deeply personal approach to composing for his own band and the iterative nature of the symphonic medium.3 And yet, the Maestro’s interest in extended forms and musical narrative has much in common with the 19th-century tone poems of the symphonic tradition. Ellington’s focus on “tone color” closely resonates with the increasing focus on timbre in 19th- and 20thcentury concert music. (Like the composers Alexander Scriabin, Olivier Messiaen, and Aaron Jay Kernis, Ellington had sound-color synesthesia.4) And while Ellington did not need the symphony orchestra to enter classical

“Much like the oeuvre of Milhaud, Barber, Bernstein, and Gershwin, the linguistic accent—jazz—is secondary to the underlying genius of Ellington’s ear for harmony, orchestration, and rhythm.”

WILLIAM

EDDINS MUSIC DIRECTOR EMERITUS OF THE EDMONTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

spaces—he was invited to play at Carnegie Hall annually from 1943 on with his jazz orchestra— he was clearly interested in doing so.

To sound the music of Duke Ellington in the orchestral hall is both an appropriate celebration of his musical legacy and a chance for symphonic audiences to be introduced to a vital strand of American music-making. It is also an overdue reclamation of Ellington’s status as a quintessential American composer who has left an inexorable mark on over five decades of artistic creation and culture, with echoes resounding across musical fields, civil rights, cultural diplomacy, and more. Wise Music is pleased to present the following guide to our symphonic arrangements of Ellington’s suites and other largescale works, with special thanks to conductors William Eddins, JoAnn Falletta, and Thomas Wilkins for contributions born out of their extensive personal experience in programming and conducting Ellington’s music. Together, we hope these resources will further the 21st-century swell of interest in symphonic Ellington.

3 This tension was often on display in Ellington’s reluctance to allow orchestrators to score solos for the same instruments as they had originally been performed on in quintessential performances by particular greats of the Ellington Orchestra, such as Johnny Hodges’ heart-breaking alto sax solo in Black, Brown, and Beige. (Maurice Peress, “My Life with Black, Brown and Beige,” Black Music Research Journal 13, no. 2 (1993), 151. https://doi.org/10.2307/779517.)

4 James, Stephen D., and J. Walker James, “Conductor of Music and Men: Duke Ellington through the Eyes of His Nephew,” in The Cambridge Companion to Duke Ellington, edited by Edward Green (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 42.

SAMPLE PROGRAMS

“A few years ago, while preparing a Duke Ellington Festival subscription weekend, I had a conversation with a reporter from the LATimes who said ‘I don’t know how one could list America’s top ten composers and not have Duke Ellington on that list.’ I am in complete agreement, and therefore, the first order for me is to take him seriously. But the second is equally important. That is to take him literally. His voice, his style, and his musical language and vernacular.

I find myself giving permission for there to be a ‘groove’ as well as sometimes explaining the difference between a musical gesture and a ‘lick.’ One is counted, the other is felt.”

THOMAS WILKINS

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ARTISTIC PARTNER FOR EDUCATION AND EXTERNAL ENGAGEMENT, PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR OF THE HOLLYWOOD BOWL ORCHESTRA, PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR OF THE VIRGINIA SYMPHONY, AND INDIANA UNIVERSITY’S HENRY A. UPPER CHAIR OF ORCHESTRAL CONDUCTING

1. ALL-AMERICAN

1: CITY LIFE

• Philip Glass, Days and Nights in Rocinha

• André Previn, Music for Boston

• Sarah Kirkland Snider, Something for the Dark

• Duke Ellington, Harlem

2. ALL-AMERICAN 2: SUITES FROM THE STAGE

• Duke Ellington, Three Black Kings

• Missy Mazzoli, Orpheus Undone

• Samuel Barber, Medea’s Dance of Vengeance

• John Adams, The Chairman Dances

“I’ve paired Harlem with Bernstein’s Symphonic Dances – two different composers with similar ideas of groove and swing. On a program with the “Planets” of Holst, I’ve included Ellington’s NewWorldA-Comin’. Recently, during a Boston Symphony Orchestra week, we created another two-program set. Both programs included the Sacred Concerts suite that I had curated for the LA Phil festival. That opened the door to us being able to present that program at a local cathedral.

In the end, the possibilities are endless if taken seriously. What I have been most pleased by has been the visceral, joyful responses of every audience and quite frankly every orchestral musician, who’ve had the experience of this exposure. And the question is always the same: ‘Where has this music been all my life?’”

THOMAS WILKINS

5 Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. “Duke Ellington and his Orchestra” New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/ items/1a7bdc00-a96a-0131-1c03-58d385a7b928

3. BALLET IN CONCERT

• Duke Ellington, The River

• Sergei Prokofiev, Suites from Romeo and Juliet

4. ENVISIONING JUSTICE, PEACE, AND EMPATHY

• George Lewis, Weathering

• Duke Ellington, New World A-Comin’

• Dmitri Shostakovich, Symphony No. 12 in D minor, Op. 112, “The Year 1917”

5. ALL-AMERICAN

3: CONCERTO GROSSO

• Gabriela Lena Frank, Concertino Cusqueño

• Aaron Jay Kernis, Concerto with Echoes

• Duke Ellington, Night Creature

“I have put these extraordinary pieces on programs of all types—from all-American (with Charles Ives and John Corigliano) to portraits of great cityscapes (Rome, Paris, and Harlem), early twentieth-century expressions of a changing world (Bartok, Stravinsky, and Ellington) to American/French programs with their mutual love of jazz (Ravel, Milhaud, ThreeBlackKings). Be prepared, however, that Duke Ellington will be the star of the show!”

JOANN FALLETTA

MUSIC DIRECTOR OF THE BUFFALO PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA, MUSIC DIRECTOR LAUREATE OF THE VIRGINIA SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR OF THE BREVARD MUSIC CENTER, AND CONDUCTOR LAUREATE OF THE HAWAII SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

WORKS

“After recording many CDs for the NAXOS label, I must say that the most exciting and brilliant of those projects was our exploration of the orchestral music of Edward Kennedy Ellington. Orchestral music? Bandleader Duke Ellington? Yes, indeed, orchestral music it is, and on the highest level. The Duke refused to be limited […] He resisted labels as an artist, asking only to be called an American composer. It is surprising that his orchestral music did not immediately fill concert halls, but now his tone poems have become sensational additions to symphonic concerts.”

JOANN FALLETTA

BLACK, BROWN, AND BEIGE 1943

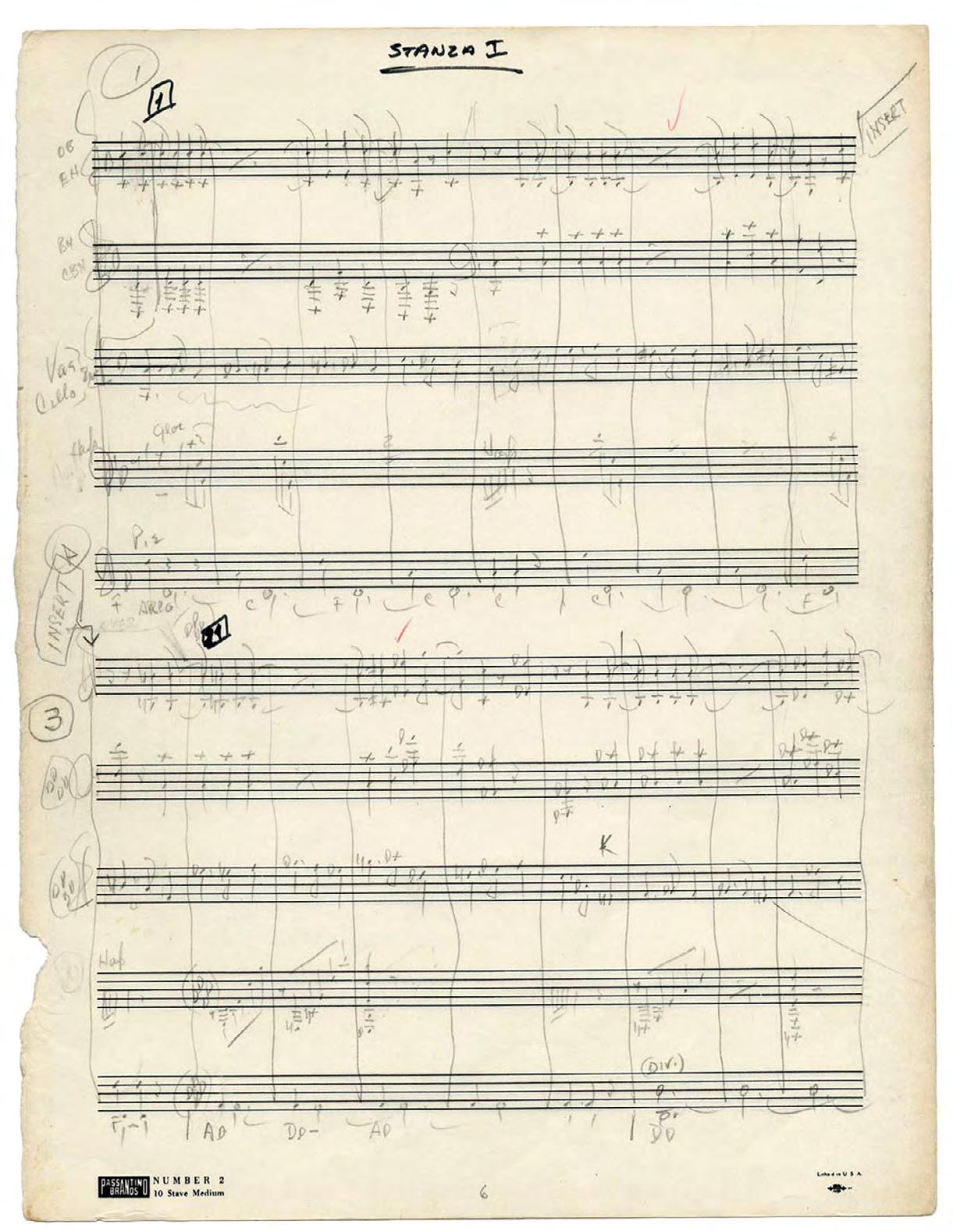

Ellington often introduced Black, Brown, and Beige as the Ellington Orchestra’s most “serious” and “certainly [their] longest” work.8 He conceived it as a “tone parallel” to the Black American experience that would musically depict a trajectory from enslavement to military service in World War II. He wrote a long scenario (sometimes called “Boola,” after its protagonist) that eloquently sets this history in verse, but the scenario was never published.9

Indeed, Ellington seems to have felt conflicted over just how open to be about this scenario.

“The original presentation of Black, Brown,andBeige in its full 50-minute form, with Betty Roché singing the blues […] was really one of the gigantic moments of music history.”

LEONARD FEATHER6 JAZZ PIANIST, COMPOSER, AND PRODUCER

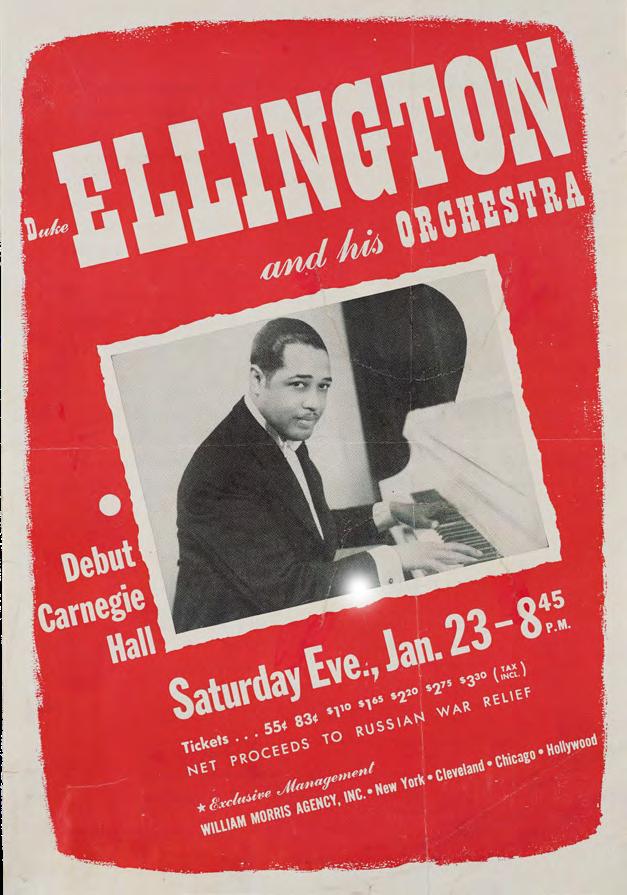

FLYER FOR ELLINGTON’S 1943 CARNEGIE HALL DEBUT, AT WHICH BLACK,BROWN,AND BEIGE WAS PREMIERED7

When the Ellington Orchestra premiered Black, Brown and Beige at their Carnegie Hall debut in January 1943, Ellington was uncharacteristically halting in his prefatory remarks.

One can almost hear him weighing how much to reveal of the more painful chapters of the scenario and its implicit critiques of American society. Many of these critiques, including the marked contrast between Black service members’ sacrifices abroad and the segregation they faced at home, would surface in other Ellington works, including New World A-Comin’.

6 Leonard Feather, Duke Ellington Society New York Chapter, 1975, on sound cassette Sc Audio C-474 side 1, New York Public Library, https://www.nypl.org/research/research-catalog/bib/b10830136

7 Carnegie Hall Archives, https://www.carnegiehall.org/About/History/Carnegie-Hall-Icons/Duke-Ellington#&gid=1&pid=1.

8 Duke Ellington, oral remarks before Black, Brown, and Beige at Carnegie Hall on January 1943 and on later occasions when the band performed excerpts from the original work (https://open.spotify.com/track/6MsHIO8prpyn7dk5lzvSLa?si=7fc1688ad44b4e4c).

9 Duke Ellington, “Black, Brown, and Beige” (unpublished script), Box 3 (series 4) folder 6-7, Duke Ellington Collection, National Museum of American History. https://sova.si.edu/record/nmah.ac.0301/ref17915?t=W&q=Boola

While nearly all the critics praised the January 1943 Carnegie Hall concert overall, many withheld such praise from Black, Brown, and Beige and often lambasted its length and what they saw as its lack of coherent form.

Ellington was nonchalant in his reaction to the criticism (“Well, I guess they didn’t dig it” was his reported reaction), but he seems to have in fact taken the piece’s initial reception to heart; the Ellington Orchestra performed Black, Brown, and Beige in its entirety only one time after the 1943 premiere.

Today, Wise Music is pleased to offer two symphonic arrangements of Black, Brown, and Beige which represent different negotiations of Ellington’s hybrid masterwork.

ORCHESTRATED BY MAURICE PERESS

3(pic+afl).2+ca.2+bcl.asx.2+cbn/4431/ timp.2perc.dmkit/hp/jazz bass/str (18 min)

Materials for this arrangement have recently been engraved.

Conductor Maurice Peress first heard the Ellington Orchestra perform the “Black” movement of Black, Brown, and Beige at a concert on the White House lawn in 1965, which he described as “an epiphany.”10 As an orchestral conductor with a lifelong love affair with jazz (and Ellington’s music in particular), Peress soon approached Ellington to ask whether he would consider a symphonic arrangement. Ellington’s initial answer—“What’s wrong with it how it is?”—was characteristically tongue-in-cheek, but after significant dialogue, Ellington asked Peress to orchestrate Black, Brown, and Beige in 1970.11

At Ellington’s suggestion Peress’ orchestration sets only the “Black” movement from the original 1943 Carnegie Hall version of the piece, which was what Peress heard performed at the White House in 1965 and the section that had enjoyed the kindest critical reception at the premiere.12 It is divided into three sections: “Work Song,” “Come Sunday,” (of which Ellington later arranged a vocal version for

10 Peress, “My Life with Black, Brown and Beige,” 148.

11 Peress, “My Life with Black, Brown, and Beige,” 149 and 151.

Mahalia Jackson, and which became a jazz standard in its own right) and “Light.”

To begin, Peress adds alto sax, drum kit, and jazz bass to standard orchestral forces. This relatively lean list of additions brings an important and appropriate rhythmic and timbral component, while keeping the instrumentation manageable. Peress changes one key signature (opening “Work Song” in D major rather than the E-flat major of the original Carnegie Hall performance), omits the piano of the original Carnegie Hall version and shortens several solo moments, especially where they might not translate well to the acoustic environment of a symphonic hall (such as an extended plucked bass solo in “Light”).

At Ellington’s suggestion, he also integrates material from “Come Sunday” in a codetta at the end of “Light,” which both he and Ellington felt ended too abruptly to serve as the finale of the entire work.13 Besides these adaptations, Peress is faithful to the musical and formal structure of the original “Black.” And indeed, Ellington appears to have approved of the orchestration; Peress writes that Ellington listened to a recording of a 1970 performance by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and “made no fuss” over Peress’ decisions besides requesting a more deliberate tempo for the opening of “Work Song.”14 For orchestras seeking a version of Black, Brown, and Beige with a direct connection to Ellington, Peress’ version has much to offer.

“Ellington did not shy away from sending a powerful message of equality to his listeners. When he performed at the famous Cotton Club in Harlem, even his family was not permitted to enter the Club, which was only open to ‘whites.’ His powerful Black,Brown,andBeigeis one of the strongest artistic statements about human rights, and this threemovement work is one of the most sophisticated of American compositions.”

JOANN FALLETTA

12 Sjef Hoefsmit and Andrew Homzy, “Chronology of Ellington’s Recordings and Performances of ‘Black, Brown and Beige,’ 1943-1973.” Black Music Research Journal 13, no. 2 (1993), 170. https://doi.org/10.2307/779518

13 Peress, “My Life with Black, Brown, and Beige,” 153.

14 Peress, “My Life with Black, Brown, and Beige,” 153-154.

ADAPTED BY JEFF TYZIK

2(pic).1+ca.2+bcl.asx.2/4331/timp.perc.dmkit/ hp/jazz bass/str (35 min)

Materials for this arrangement are fully engraved.

Compared to the Peress orchestration, Jeff Tyzik’s 1998 adaption of Black, Brown, and Beige restores a significant amount of material from the “Brown” and “Beige” movements of the work. Tyzik—a Grammy Awardwinning pops conductor and highly-regarded arranger—orchestrates the complete “Black,” with the exception of a few shortened solos and piano-focused transitions. (As Tyzik observes, Ellington played surprisingly little piano on Black, Brown, and Beige, so omitting it from the orchestration makes sense to keep the forces economical.)

Tyzik also takes on the majority of “Brown,” omitting only the final section “Mauve,” also known as “The Blues”. (“Mauve” is the lone vocal section of the piece; it featured singer Betty Roché’s beautifully plaintive voice in the original Carnegie Hall performance and was always performed with a singer when Ellington programmed excerpts of Black, Brown, and Beige thereafter.) The first two sections of Brown are “West Indian Dance,” Ellington’s “salute to the West Indian influence,” and “Emancipation.” This latter section depicts both the “younger generation that had so much to look forward to when the Emancipation Proclamation […] came as a skyrocket” and an older generation of formerly enslaved people “who had earned the right to sit down and rest.”15

Tyzik then moves straight into the second and third sections of the original “Beige”: “Last of Penthouse” (also called “Sugar Hill Penthouse”16) and “Finale,” which takes on the wartime context of Black, Brown, and

Beige’s 1943 premiere by exploring how “we find the black, brown, and beige right in there for the red, white, and blue.”17

Though Tyzik based his arrangement on early recordings of the suite, the sections included in this arrangement are also reflective of Ellington’s practice throughout much of the rest of his life, as he often presented these sections as excerpts throughout the 1940s and 1960s.18 Considering the ongoing scholarly reconsideration of Black, Brown, and Beige’s critical reception after the Carnegie Hall premiere, performances of Tyzik’s pragmatic arrangement offer a wonderful opportunity to introduce orchestral audiences to more of the original work.

“My goal in orchestrating Ellington’s music for symphony orchestra is to symphonically enhance the music without changing his original musical intent. Ellington’s music is melodically rich, so there is a lot to work with when it comes to giving the orchestra interesting and challenging parts to play.”

JEFF TYZIK COMPOSER,

ARRANGER, AND PRINCIPAL POPS CONDUCTOR OF THE ROCHESTER PHILHARMONIC, DALLAS SYMPHONY, DETROIT SYMPHONY, AND OREGON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRAS

15 Edward Kennedy Ellington, oral remarks before “Brown,” Duke Ellington Carnegie Hall Concerts January 1943, https://open.spotify.com/track/217mt7Cxda7d4ohT4kARkY?si=044b17c5865f4ba0

16 This section draws on Billy Strayhorn’s preexistent composition Symphonette-Rhythmique. See Walter van de Leur, Something to Live For: The Music of Billy Strayhorn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 80.

17 Edward Kennedy Ellington, oral remarks before “Black,” Duke Ellington Carnegie Hall Concerts January 1943, https://open.spotify.com/track/217mt7Cxda7d4ohT4kARkY?si=044b17c5865f4ba0

18 Hoefsmit, Sjef, and Andrew Homzy. “Chronology of Ellington’s Recordings and Performances of ‘Black, Brown and Beige,’ 1943-1973.” Black Music Research Journal 13, no. 2 (1993): 161–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/779518

NEW WORLD A-COMIN’ 1945

Despite the mixed reviews of Black, Brown, and Beige at its premiere, Ellington’s 1943 Carnegie Hall debut was successful enough that he was annually invited back to the iconic venue thereafter.19 The Maestro often took these concerts as opportunities to premiere new large-scale works for his Ellington Orchestra. New World A-Comin’ numbers among these works and was premiered at Carnegie in December 1943, just eleven months after Ellington’s debut at the hall.20

Its title is drawn from a book by the celebrated Black author Roi Ottley, which traced the lives of Black Americans in Harlem in the ‘20s and ‘30s, examining the ways that they were asked to defend the US abroad while being subjected to intense racism at home. In borrowing Ottley’s title, Ellington implicitly aligned himself with Ottley’s politics and his list of careful demands for justice and equality in post-war America. For this reason, jazz scholars have often read New World A-Comin’ as a spiritual successor to Black, Brown, and Beige (where Ellington had veiled the political stance of his Boola scenario.21) In a virtuosic exchange between the Duke Ellington Orchestra and Ellington on the piano, New World A-Comin’ articulated Ellington’s vision of a “place in the distant future where there would be no war, no greed, no categorization, no non-believers, where love was unconditional, and no pronoun was good enough for God.”22

Ellington quickly brought New World A-Comin’ into a symphonic context, as it was featured in his very first concert with symphony orchestra in 1949.23 At the Robin Hood Dell in Philadelphia (now known as the Dell Music Center), musicians from the Philadelphia

Orchestra performed New World A-Comin’ alongside the Ellington Orchestra in a kind of concerto grosso for jazz band and symphony orchestra. Ellington clearly was interested in this performance arrangement and used the term “concerto grosso” for slightly later works.24

Like Black, Brown, and Beige, New World A-Comin’ exists in two symphonic arrangements: one by Maurice Peress and one worked on by Jeff Tyzik (in this case, as an editor for the celebrated Black composer and arranger Luther Henderson).

ARRANGED AND EDITED BY MAURICE PERESS

Solo pf + 2(pic).2.2+bcl.2/4431/timp.perc. dmkit/hp/str [+ dance band] (14 min)

The score for this arrangement is engraved; parts are handwritten and neatly copied.

Peress modeled his 1983 version of New World A-Comin’ on the two-ensemble arrangement of the Robin Hood Dell performance. Scored for symphony orchestra, it also features a “dance band” with a flexible number of saxophones, trumpets, and trombones.25 In what is likely an effort to make the arrangement more accessible to orchestras, Peress notes the dance band as optional and includes much of its material in doublings in the symphonic parts. The result is an arrangement that offers a wide range of options to orchestras while preserving the fundamental spirit of Ellington’s version. Like many of Peress’ Ellington arrangements, this version makes more extensive melodic use of the string section than the Henderson arrangement discussed below, giving it more of a “Broadway” or “pops” sound.

19 Carnegie Hall, “Carnegie Hall Icons: Duke Ellington” (https://www.carnegiehall.org/About/History/Carnegie-Hall-Icons/ Duke-Ellington).

20 Carnegie Hall appearance listing (https://www.carnegiehall.org/About/History/Performance-History-Search?q=&dex=prod_ PHS&event=33502&pf=Duke%20Ellington_).

21 Graham Lock reads NWAC as a “conceptual successor” to BBB, while David Schiff goes even further to term it a “conceptual replacement” to BBB. David Schiff, “Symphonic Ellington? Rehearing New World A-Comin’,” The Musical Quarterly, Volume 96, Issue 3-4, Fall-Winter 2013, 468-469, https://doi-org.ezproxy.csbsju.edu/10.1093/musqtl/gdt011

22 Ellington, Music is My Mistress, 183.

23 https://manncenter.org/vault-7-24-49

24 Ellington, Music in My Mistress,183.

25 David Schiff, “Symphonic Ellington? Rehearing New World A-Comin’,” 466.

ARRANGED BY LUTHER HENDERSON AND EDITED BY JEZZ TYZIK, WITH A PIANO TRANSCRIPTION BY JOHN NYERGES

Solo pf + 2.2+ca.3+bcl.2/4331/timp.perc. dmkit/jazz bass/str

Materials for this arrangement are fully engraved.

Often referred to as Ellington’s “classical arm,” American composer, arranger, and pianist Luther Henderson enjoyed a long and productive relationship with the Ellington family, stretching from his school days with Duke Ellington’s son Mercer through the many symphonic arrangements he made of Ellington Orchestra works in consultation with the Maestro. For New World A-Comin’, Henderson based his arrangement on a 1945 recording that Ellington made for a Treasury Department-sponsored radio show.27 In this version of the piece, Ellington tightened up its form to a leaner 11 minutes while retaining its fundamental “bone structure.”28 Henderson’s arrangement preserves these cuts and makes

a few others, many of which serve to increase the soloist’s importance as a kind of “firstperson narrator”.29 Henderson’s choice of instrumentation is similar to that of the Peress arrangement, but without the added jazz band. David Schiff has described Henderson’s orchestration as “an amplified version of the Ellington orchestra with the horns (French and English) taking the place of the sax section.”30

John Nyerges’ transcription of Ellington’s piano part—which he always performed from memory and evidently never wrote down—completes an arrangement that cogently explores Ellington’s vision for a freer, more just future.

“Ellington is a category within himself. He’s a whole world and a whole school— and it’s not just musical, it’s social and psychological.”

26 William P. Gottlieb, photographer. Portrait of Duke Ellington and Sonny Greer, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., ca. Nov., 1946. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2023867645/

27 David Schiff, “Symphonic Ellington? Rehearing New World A-Comin’,” 466.

28 David Schiff, “Symphonic Ellington? Rehearing New World A-Comin’,” 467.

29 David Schiff, “Symphonic Ellington? Rehearing New World A-Comin’,” 467.

30 David Schiff, “Symphonic Ellington? Rehearing New World A-Comin’,” 470.

31 Leonard Feather, Duke Ellington Society New York Chapter, 1975, on sound cassette Sc Audio C-474 side 1, New York Public Library, https://www.nypl.org/research/research-catalog/bib/b10830136

GRAND SLAM JAM 1949

ARRANGED BY LUTHER HENDERSON, EDITED BY MAURICE PERESS

22(ca)2(bcl).2asx+2tsx[+bar].2/4431/ timp.2perc.vib.dms/hp/str (8 min)

Score for this arrangement is engraved; parts for this work are handwritten.

Grand Slam Jam was written for the same Robin Hood Dell concert at which the concerto grosso version of New World A-Comin’ was premiered, making it the first of Ellington’s works originally scored for symphonic forces and jazz orchestra. Ellington later reworked this piece under the title Non-Violent Integration—a perfect example of his approach to advancing the rights and status of Black Americans through strategically garnering respect and acclaim, even in segregated spaces.32

This symphonic arrangement by Henderson is subtitled “An improvisation for Symphony Orchestra, Jazz Soloists, and Optional Dance Band.” As with Peress’ arrangement of New World A-Comin’, it may be performed without the dance band, as the band’s material is integrated into the symphonic parts (here, in cue-sized notes to be performed only in the absence of a band). Henderson directs conductors to “include whatever jazz soloists are available” and gives examples of soloist configurations that Ellington employed; all chosen soloists trade off reading from a single “solo” line. The flexibility of this arrangement makes it a wonderful selection for orchestras with principals who have jazz backgrounds. ELLINGTON—PERHAPS ABOUT TO HIT A NON-MUSICAL GRAND SLAM—OUTSIDE A SEGREGATED MOTEL WHILE ON TOUR IN 1955.33 WHEN POSSIBLE, ELLINGTON SHIELDED HIS BAND MEMBERS FROM SOME OF THE INDIGNITIES OF SEGREGATION BY TRAVELING IN THEIR OWN PULLMAN CAR COMPLETE WITH SLEEPING QUARTERS

“Duke was like a father, a best friend...a great leader, the greatest musician, the greatest handling of his men, handling of the public... He never got ruffled under any conditions.”

RAY NANCE

32 As Harvey Cohen observes, “[b]efore Duke Ellington’s rise to fame in the late 1920s and early 1930s, no African American had ever been so widely hailed around the world as a serious artistic figure, without the stereotypes usually affixed to African American creators.” Harvey G. Cohen, “The Marketing of Duke Ellington: Setting the Strategy for an African American Maestro,” The Journal of African American History 89, no. 4 (2004), 291. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134056

33 Charlotte Brooks, LOOK Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-09451. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2009632168/

HARLEM 1950

In his autobiography Music is My Mistress, Ellington writes that Harlem was commissioned by the NBC Symphony Orchestra and renowned conductor Arturo Toscanini as part of a larger project to musically depict New York. The aging Toscanini never ultimately completed the project or conducted the work,34 and Harlem was instead premiered at the Metropolitan Opera House with the Ellington Orchestra alone in 1951. It was later performed with its intended forces at Carnegie Hall in 1955, with Ellington conducting both his own band and the Symphony of the Air.35

Ellington explained the piece’s program thus: “[Harlem] has always had more churches than cabarets. It is Sunday morning. We are strolling from 110th Street on Seventh Avenue, heading north through the Spanish and West Indian neighborhood toward the 125th Street business area. Everybody is nicely dressed, and on their way to or from church. Everybody is in a friendly mood. Greetings are polite and pleasant, and on the opposite side of the street, standing under a street lamp, is a real hip chick. She, too, is in a friendly mood. You may hear a parade go by, or a funeral, or you may recognize the passage of those who are making our Civil Rights demands.”

His note presents a scene of both liveliness and respectability, emphasizing the dignity and humanity of Harlem’s inhabitants. Throughout the piece, its program is punctuated by trumpet calls that employ the plunger mute and a descending third to famously musicalize the two syllables of “Harlem.”

Harlem enjoys two closely related symphonic arrangements: one by Henderson/Peress and a second based on the Henderson/Peress arrangement, edited by John Mauceri.

ARRANGED BY LUTHER HENDERSON AND MAURICE PERESS

3(pic).2+ca.2+bcl.2asx(cl)+2tsx(2cl) +barsx(bcl). 2/0421/timp.perc.dmkit/hp/str (18 min)

Score and parts for this arrangement are currently handwritten; newly engraved materials are forthcoming in 2025.

Of the two available arrangements, this earlier version by Henderson and Peress features more orchestral doublings, giving the upper winds and strings a greater role in the work. Its more extensive use of the drumset also preserves a particular kind of jazz sound in a symphonic context.

Henderson was responsible for the original symphonic arrangement of the 1955 Carnegie Hall premiere, so this version bears a direct connection to Ellington.

“To me it was like a dream come true to be connected with Mr. Ellington. And then he gave me the chance to do things that he knew I was capable of doing, and he did that for all his men. And that was one of the great secrets of his success, because he wrote music for his men.”

RAY NANCE

34 Duke Ellington, Music is My Mistress, 188-189. (See, for example, Stanley Slome, “Duke Ellington and the Classical Connection,” for a discussion of the fact that Toscanini and the NBC Symphony seem never to have premiered the piece; https://ellingtonweb.ca/Slome-Harlem.htm).

35 Carnegie Hall archival performance listing (https://www.carnegiehall.org/About/History/Performance-History-Search?q=&dex=prod_ PHS&page=2&event=29228&pf=Duke%20Ellington_).

ARRANGED BYLUTHER HENDERSON AND MAURICE PERESS, EDITED

BY JOHN MAUCERI

3(pic).2+ca.2+bcl.2asx(cl)+2tsx(cl)+ barsx(bcl).2/0521/ timp.perc.dmkit/hp/str (18 min)

Score and parts for this arrangement are currently handwritten; newly engraved materials are forthcoming.

This later edition by conductor John Mauceri strips out many of the doublings of the Henderson/Peress version, creating more soloistic moments that allow for principals with a jazz background to take greater liberties in shaping Ellington’s lines. Mauceri based these reduced doublings on his analysis of Ellington’s performance practice via recordings, including Harlem’s full 1955 premiere.

“Ellington’s blazing Harlem opens with a gravelly trumpet firecracker intoning the name of his home—HAR-LEM—and continues with splendid brass writing that pays homage to New York and to jazz itself. It is a grand tribute replete with blazing colors, avant-garde timbres and a soulful helping of ‘down-home’ blues that is irresistible.”

(https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.92.58).

NIGHT CREATURE 1956

Ellington’s Night Creature was commissioned by Symphony of the Air, an orchestra formed in 1954 by members of the recently disbanded NBC Symphony. The piece was premiered at the same 1955 Carnegie Hall concert where the concerto grosso version of Harlem was first heard.38 It is a whimsical piece, exploring the romance and mystery of after-hours nightlife in three movements, featuring “blind bugs, boogie-woogie monsters, and a dazzling queen who reigns over all Night Creatures.” 39

ADAPTED BY RAYBURN WRIGHT AND ORCHESTRATED BY DAVID BERGER

2.1.2(bcl).2asx.2tsx.barsx.1/2431/2perc.dmkit/ hp.pno/jazz bass/str (17 min)

Score and parts for this arrangement are handwritten, and the arrangement requires a drummer with the ability to improvise on notated patterns.

In 1974, famed American choreographer Alvin Ailey debuted his beloved dance work Night Creature, which has become an enduring staple of the Ailey repertory. The arrangement of Night Creature used by Ailey includes a reed section, drum kit, piano, jazz bass,

and large trumpet section to draw in many of the characteristic timbres of the Ellington Orchestra.40

ORCHESTRATED BY DUKE ELLINGTON AND LUTHER HENDERSON, EDITED BY GUNTHER SCHULLER

Symphony orchestra: 3.2.3+bcl.2/4431/ timp.2perc/hp/str

Jazz orchestra: 2asx.2tsx.barsx/4tpt.3tbn/ pno/drums/db (17 min)

Score and parts for this arrangement are fully engraved.

Henderson orchestrated the original 1955 version of the piece for the Ellington Orchestra and Symphony of the Air, and this arrangement comes out of that version and its concerto grosso model. Like the Wright/Berger version, it employs a five-piece reed section, plus piano, drum kit, and jazz bass. But here, the big band instruments are separated out into a discrete “jazz orchestra” with added trumpets and trombones. While the drum kit part is more fully notated than in Wright/Berger’s version, other members of the jazz orchestra are often given lead sheet-style notation with “ad lib” solo invitations.

THE NUTCRACKER SUITE 1960

FREELY ARRANGED BY DUKE ELLINGTON AND BILLY STRAYHORN, ARRANGED AND ADAPTED BY JEFF TYZIK

2.1+ca.2+bcl.asx(tsx).2/4331/dmkit/ jazz bass/str (31 min)

Score and parts for this arrangement are fully engraved.

Ellington and Strayhorn’s jazzy reimagining of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker is a towering achievement of adaptation. It is well-known from a beloved 1960 Ellington Orchestra recording, which is the basis of

a frequently-performed jazz band edition.

Jeff Tyzik’s arrangement for symphony orchestra almost mirrors Tchaikovsky’s own orchestration, adding a single saxophone player, drum kit, and jazz bass to create a microcosm of the Ellington Orchestra.

In 2022, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Gustavo Dudamel brilliantly juxtaposed the two Nutcrackers on one concert program. In doing so, they built a bridge across continents, centuries, and styles, producing a musical event “beyond category,” to use the Maestro’s signature phrase.

38 James Lincoln Collier, Duke Ellington (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 284.

39 Duke Ellington, scenario for Night Creature, qtd. in program notes by John Henken (https://www.laphil.com/musicdb/pieces/516/night-creature).

40 https://www.alvinailey.org/performances/repertory/night-creature

THE RIVER 1970

ORCHESTRATED BY RON COLLIER

2(pic).2(ca).2.2/4.3.2+btbn.1/timp.2perc/ pf.hp/str (30 min)

Score and parts for this work are fully engraved.

Commissioned by American Ballet Theatre for choreographer Alvin Ailey, The River is Ellington’s only largescale suite that was intended for dance from its beginning. The work follows a waterway through its various stages, from a spring to rapids, a lake to a vortex. Ellington also saw this narrative as a spiritual one, with the moment the river reaches the sea serving as a kind of rebirth. In a 1983 interview, Ailey explained Ellington’s deep engagement with his theme: “Once he decided that he was going to write this river piece as a ballet, he had all the world’s water music on recordings. He had the scores and everything. He had Handel’s Water Music; he had Debussy’s La Mer; he had Benjamin

Britten’s Peter Grimes. He said, ‘I’ve been listening to this to see what other people have done with water music’.”41

Canadian composer and arranger Ron Collier worked with Ellington on a number of projects throughout his life, and Collier orchestrated seven of Ellington’s original twelve movements for the American Ballet Theatre premiere in 1970. Unlike many symphonic Ellington arrangements, Collier’s does not include a full drum kit; instead, sticks and brushes on suspended cymbal often give a more minimal but tasteful nod to the drum kit sound. As one might expect of water music, several beautiful flute solos are featured (such as particularly lovely solos over hushed strings at the opening and close of the “Lake” movement). In general, both the music and the orchestration are light-footed, sweeping dancers and audience alike onwards and out to sea.

THE GOLDEN BROOM AND THE GREEN APPLE 1965

EDITED BY MAURICE PERESS

3(pic).3(ca).3(bcl).3(cbn)/4441/timp.perc.dms/ hp/str (15 min)

Score and parts for this arrangement are handwritten, and the drum part requires an improvising drummer. Newly engraved score and parts are forthcoming.

Together with The River, The Golden Broom and the Green Apple is one of the few Ellington works originally conceived for symphony orchestra. It was premiered by the New York Philharmonic with Ellington conducting on July 30th, 1965, and Ellington’s autograph sketches held by the Yale Library show parts for symphonic instruments not included in the

Ellington Orchestra.42 Maurice Peress was present at the premiere and observed that the orchestration by Joe Benjamin (Ellington’s bassist and copyist at the time) suffered from some awkward bowings that obscured the phrasing of a “charming musical essay about two young women, one worldly wise and citified, the other a fresh young lass from the country.”43 After the premiere, Peress “vowed to do this piece […] symphonic justice” and later “cleaned up” the score and parts for performances in the late 1960s.44 Since then the piece has enjoyed relatively few performances, making it a work that is ripe for rediscovery.

41 Alvin Ailey, qtd. in https://www.laphil.com/musicdb/pieces/3822/the-river-suite

42 French-American Festival Program (July 30, 1965), ID 7269, New York Philharmonic Shelby White and Leon Levy Digital Archives, New York, NY, https://archives.nyphil.org/index.php/artifact/28e6a926-096b-4009-be20-f12799757cd7-0.1/ fullview#page/1/mode/2up; Autograph manuscript of The Golden Broom and the Green Apple (undated), Misc. Ms.404p1, Gilmore Music Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT, https://onlineexhibits.library.yale.edu/s/hot-spots/ item/2132#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=157%2C618%2C1113%2C744

43 Peress, “My Life with Black, Brown, and Beige,” 149.

44 Peress, “My Life with Black, Brown, and Beige,” 150.

SELECTIONS FROM THE SACRED CONCERTS 1965-1973

AIN’T BUT THE ONE AIN’T NOBODY NOWHERE DAVID DANCED HEAVEN THE MAJESTY OF GOD MY LOVE

SOMETHING ‘BOUT BELIEVING TELL ME IT’S THE TRUTH ORCHESTRAL ADAPTATIONS BY CHARLES FLOYD

solo vocalist +3.2+ca.2+bcl.2+cbn.2asx.2tsx. barsx/4.4.2+btbn.1/timp.2perc.dmkit/pf/ str.jazzdb.

Selected songs also include one to three additional singers or vocal ensemble; David Danced includes tap dance; and Something ‘Bout Believing and My Love include windchimes. (3-8 min each or 43 min for all eight songs)

Score and parts for these arrangements are fully engraved.

In 1965, Ellington was invited to present a concert of sacred music at San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral as part of a year-long celebration of its completion.

ELLINGTON AND THE ELLINGTON ORCHESTRA AT GRACE CATHEDRAL, SEPTEMBER 16, 196546 46 Photo courtesy of the Grace Cathedral Archives.

Ellington was a devout Christian, and regarded this as “a great opportunity.”47 Mixing newly composed and reworked material from earlier in his career, Ellington put together a “lyrical sermon” that he regarded as the most important music he ever created. Over the course of 1965 to 1973, Ellington put together two more such programs to create the Second and Third Sacred Concerts. The sincerity of Ellington’s convictions and his genuine love for humanity shine through in these beautifully orchestrated songs.

“Of all man’s fears, I think men are most afraid of being what they are—in direct communication with the world at large […] Yet, every time God’s children have thrown away fear in pursuit of honesty—trying to communicate themselves, understood or not—miracles have happened.”48

DUKE ELLINGTON

THREE BLACK KINGS 1974

On April 4, 1968, Ellington’s annual Carnegie Hall concert was overshadowed by the tragic news of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, which was announced from the stage before the start of the show.49 Ellington had long admired Dr. King. In 1963, he reimagined King as the protagonist of the spiritual “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho” in “King Fit the Battle of Alabam,” a tribute to King’s courage in the face of police violence in Birmingham that April.50 The River is also dedicated to Dr. King.

Towards the end of his life, Ellington wished to musically honor King once more. The result was Three Black Kings, a suite in which Ellington exalts Dr. King alongside the biblical figures King Balthazar and King Solomon. In this triptych, Ellington envisioned an evocative, richly textured homage to a history of Black greatness. Unfortunately, Ellington did not manage to finish Three Black Kings before his death in 1974, leaving it to his son Mercer—an accomplished composer, arranger, and bandleader in his own right—to complete.

Alvin Ailey choreographed Mercer Ellington’s completed version of the work in 1976, leading to the subtitle of the Henderson arrangement: “Ballet for Orchestra.” Three Black Kings finishes out the trilogy of Ellington works set to dance by Ailey, which also includes Night Creature and The River. It also has the most robust arrangement history of all symphonic Ellington suites, with four symphonic arrangements currently available.

“I wanted to celebrate [Ellington’s] daring, his beauty, his wit, his enormous spirit […] this great man who through his music, through his personality, and through his love of humanity healed some of the wounds of this century.”51

ALVIN

AILEY

ARRANGED BY LUTHER HENDERSON

2+pic.2+ca.2+bcl.2+cbn/4441/timp.perc. dmkit/egtr.hp.pf/str (15 min)

Score and parts for this arrangement are fully engraved.

Henderson’s symphonic arrangement uses palm-muted electric guitar, marimba or thumb piano, and harp to create a unique timbre for the beautiful flowing ostinato of the first movement. In general, the orchestration heavily features the harp, utilizing it throughout as well as for the first solo of the second movement. Solo passages are generally written-out, and the orchestration includes no saxophones— a choice that honors Ellington’s preferences, since according to Peress, Ellington “did not want to introduce the saxophone into his symphonic works since the orchestra had so many colors of its own.”52

“Ellington’s LeTroisRoisNoirs(ThreeBlack Kings)is the last outburst of one of the most creative artistic minds of the 20th century. It is noteworthy that Ellington intended this work for a ‘classical’ orchestra, and therefore a ‘classical’ audience. The ballet version is suitable for most any occasion, whether on a general program of American music or as a counterpart to other tone poems of the classical genre. As this work is a story about persons (real or legendary) it is well suited to join Strauss’ Till Eulenspiegel or Grieg’s Peer Gynt for example, or act as an opening work to accompany a 20th-/ 21st-century concerto.”

WILLIAM EDDINS

49 https://www.carnegiehall.org/About/History/Carnegie-Hall-Icons/Duke-Ellington

50 https://slate.com/culture/2013/01/martin-luther-king-tribute-by-duke-ellington-my-people-50-years-later-video.html

51 Alvin Ailey, qtd. in Patricia Willard, “Dance: The Unsung Element of Ellingtonia,” The Antioch Review 57, no. 3 (1999), 413. https://doi.org/10.2307/4613888.

52 Peress, ”My Life with Black, Brown, and Beige,” 150. Though it was ”a decision that was not made lightly,” Peress did ultimately decide to go against Ellington’s general wishes in using saxophone in his orchestrations of some works, such as the haunting alto sax solo of ”Come Sunday” in Black, Brown, and Beige and the tenor sax used throughout Peress’ arrangement of Three Black Kings discussed below.

VERSION FOR SOLO TENOR SAXOPHONE AND ORCHESTRA, EDITED BY MAURICE PERESS

Solo tsx + 3(pic).2+ca.2+bcl.2+cbn/4431/timp. perc.trap set/hp.pf/str+jazz bass (19 min)

The score for this arrangement is engraved; parts are handwritten.

Peress’ arrangement strips out the electric guitar but adds a solo tenor saxophone, which is featured in the second and third movements. Like many of Peress’ Ellington arrangements, there is extensive use of the strings throughout, and piano often replaces the harp from the above Henderson version. A trumpet is featured prominently at several moments where it is absent in the Henderson arrangement, such as the second solo of the second movement as well as a later solo moment with orchestra bells. A few solo fills are left to the discretion of the performers. This arrangement is likely to be an attractive option to those who find a saxophone sound integral to Ellington but would like to avoid the logistical complications of hiring a full saxophone section.

CONCERTO GROSSO VERSION, ARRANGED BY LUTHER HENDERSON

Orchestra: 2+pic.2+ca.2+bcl.3(cbn)/4001/ timp.perc/hp.pf/str

Jazz band: 2asx.2tsx.barsx.4tpt.4tbn(btbn). dmkit(cga).egtr.pf.bass (19 min)

Score and parts for this arrangement are handwritten.

This second arrangement by Henderson offers a jazz band plus symphony orchestra version of the piece, with a full reed section of two altos, two tenors, and one baritone saxophone (with clarinet doublings). The larger forces offer an opportunity for a fuller sound at key moments, though Henderson exercises significant restraint in sections such as the opening Balthazar texture.

MARTIN LUTHER KING MOVEMENT ONLY, ARRANGED BY LUTHER HENDERSON WITH REDUCED ORCHESTRATION BY TERENCE BLANCHARD

2222/2330/[timp].perc.dmkit/pf.[cel]/str (7 min)

Score and parts for this arrangement are fully engraved.

This latest version of Three Black Kings features only the Martin Luther King Jr. movement, which provided the impetus for Ellington’s composition and is in many ways the beating heart of the work. Based on Henderson’s first arrangement for symphony orchestra, Terence Blanchard’s 2021 orchestration reworks this gospel-inflected movement for leaner orchestral forces. Blanchard’s deep experience as a trumpeter, arranger, and composer with equal facility in jazz and orchestral idioms is on full display in this skillful adaptation.

“My particular favorite of the tone poems is ThreeBlackKings, and in it Ellington presents fascinating musical sketches of three important Black men of history […] The third movement (and the reason he began the piece) is to make clear his love for and admiration of the deceased Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. His movement is a portrait of a Sunday morning in Harlem right after the church service, the King family walking in their best clothes, peaceful and content on a beautiful day. That movement never fails to bring me to tears.”

JOANN FALLETTA

THE ESSENTIAL ELLINGTON: MUSIC OF ELLINGTON AND STRAYHORN 1995

ARRANGED BY JEFF TYZIK

2222/4331/timp.2perc.drmkit/pf.hp/jazz bass/ str (12 min)

ELLINGTON PORTRAIT 1998

ARRANGED BY JEFF TYZIK

2+pic.1+ca.2+bcl.asx.2/4331/timp.2perc. dmkit/hp.pf/jazz bass/str (16 min)

Score and parts for this arrangement are fully engraved.

In the 90s, Jeff Tyzik created two orchestral medleys of Ellington and Strayhorn’s most popular tunes. Each medley takes seven of their greatest short-form hits, then connects and orchestrates them for symphonic forces.

The Essential Ellington contains miniature masterpieces like “Take the A Train,” while Ellington Portrait incorporates such hits as “Sophisticated Lady,” “Mood Indigo,” and more. The instrumentation is similar for each, including forces of harp, drumkit, and jazz bass. Ellington Portrait also incorporates a slightly expanded wind section including an alto sax and more doublings. These fast-moving tours through Ellington’s masterful handling of the popular song are proven crowd-pleasers and loving homages to the Maestro.

LUSH LIFE: THE MUSIC AND STORY OF DUKE ELLINGTON AND BILLY STRAYHORN 2019

ARRANGED BY JEFF TYZIK

solo vocalist + 2.2(ca).2.2asx(ssx).2tsx.1barsx (bcl).2/4331/2perc(timp).dmkit/hp.jazz pf/ gtr. jazz bass/str (95 min, including 20 min intermission)

Score and parts for these arrangements are fully engraved.

Created as a co-production between Schirmer Theatrical and Greenberg Artists, Lush Life is a concert program celebrating the music and collaborative partnership of Ellington and Strayhorn. From celebrated jazz standards that Ellington and Strayhorn created together (“Take the A Train,” “Satin Doll,” and more) to their playful reworking of The Nutcracker Suite

discussed above, Lush Life presents a crosssection of works by this unparalleled musical duo. The orchestral arrangements by Jeff Tyzik feature his usual pragmatism and sensitivity, as well as an expanded reed section. The concert program package includes a featured vocal soloist, all performance materials, and optional black and white projections featuring archival imagery of Ellington and Strayhorn performing; together, these resources create a streamlined evening that beautifully honors two exceptional musical voices.

FURTHER RESOURCES

An essential Ellington collection is housed at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. It comprises four hundred cubic feet of archival materials spanning approximately 1923-1988 and divided into sixteen series of sound recordings, photographs, scores and parts, correspondence, and more.54

The Library of Congress (LOC) holds several photo collections with notable images of Ellington, such as the William P. Gottlieb Collection and the LOOK Magazine Photograph Collection. Notably, the LOC also houses a collection of Billy Strayhorn’s manuscripts and estate papers, which includes many of his compositions and arrangements for the Ellington Orchestra.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture holds a few advertising materials (postcards and posters), letters, financial records, photos of Ellington, and issues of EBONY Magazine featuring him, along with a single autograph lead sheet for “Caribee Joe.”

The New York Public Library holds several photo collections that include images of Ellington and a number of Ellington-related posters, as well as a collection of newspaper clippings (held in the Performing Arts Research Collections) and sound recordings of meetings of the New York Chapter of the Duke Ellington Society (in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture).

The National Museum of African-American Music holds a collection of material culture items related to Ellington (including a suit, sports jackets, and medals) as well as an extensive discography of Ellington’s music on CDs and vinyl.

SPECIAL THANKS

Special thanks to Carnegie Hall, Grace Cathedral, Jazz at Lincoln Center, Jeff Tyzik, JoAnn Falletta, the National Museum of American History, the New York Philharmonic, the Richard Avedon Foundation, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Thomas Wilkins, William Eddins, and the Yale University Irving S. Gilmore Music Library.

For general enquiries regarding the catalogue of Duke Ellington please contact your local Wise Music Office or visit wisemusicclassical.com

Bergamo

Berlin

Copenhagen

Hong Kong

Leipzig

London

Los Angeles

Madrid

New York

Paris

Reykjavík

Sydney

Tokyo

G. Schirmer & Associated Music Publishers

G. Schirmer Australia

Chester Music

Novello & Co

Alphonse Leduc

Edition Wilhelm Hansen

Edition Peters

Editions Transatlantiques

Choudens

Le Chant du Monde

Unión Musical Ediciones

promotions@wisemusic.com wisemusicclassical.com