Article STEM,aNon-PlaceforWomen?Evidencesand TransformativeInitiatives

EvaCernadas 1,2,*,† ,EvaAguayo 2,3,† ,ManuelFernández-Delgado 1 andEncinaCalvo-Iglesias 2,4

1 CentroSingulardeInvestigaciónenTecnoloxíasIntelixentes(CiTIUS),UniversityofSantiagodeCompostela, 15782SantiagodeCompostela,Spain;manuel.fernandez.delgado@usc.es

2 CentroInterdisciplinariodeInvestigaciónsFeministasedeEstudosdeXénero(CIFEX),UniversityofSantiago deCompostela,15782SantiagodeCompostela,Spain;eva.aguayo@usc.es(E.A.);encina.calvo@usc.es(E.C.-I.)

3 DepartmentofQuantitativeEconomics,UniversityofSantiagodeCompostela, 15782SantiagodeCompostela,Spain

4 DepartmentofAppliedPhysics,UniversityofSantiagodeCompostela,15782SantiagodeCompostela,Spain

* Correspondence:eva.cernadas@usc.es

† Theseauthorscontributedequallytothiswork.

Abstract: Numerousstudies,diagnoses,andprojectshavebeencarriedoutinrecent yearstoanalyzethelowfemalepresenceinSTEMstudies.However,progresshasbeen limited,andthefemalepresenceisstilllowincertaindegreesrelatedtoinformationand communicationtechnologies,physics,andengineering.Manyoftheactionshavebeen aimedatattractingwomentothesefields,butfewhavetriedtochangethecultureofthese disciplines,whichmakethemanon-placeforwomen.Thispaperanalysesthemeasures carriedoutinSpanishpublicuniversities,andspecificallyattheUniversityofSantiago deCompostela,tocontributetomakingthesedisciplinesaplaceforwomen.Computer engineeringworkshopsforprimaryandsecondaryeducationareproposed,incorporating agenderperspective.Thesetransformativeactivitieswerehighlyvaluatedandwelcomed bynon-universityteachers.Theideasinspiringtheseinitiativesmighthelpbothtoattract girlstoSTEMdegreesandtogenerategenderequalityenvironments,inordertochange theandrocentriccultureofthisfield.

AcademicEditors:NigelParton,Rosa MonteiroandLinaCoelho

Received:7March2025

Revised:16May2025

Accepted:13June2025

Published:17June2025

Citation: Cernadas,Eva,Eva Aguayo,ManuelFernández-Delgado, andEncinaCalvo-Iglesias.2025. STEM,aNon-PlaceforWomen? EvidencesandTransformative Initiatives. SocialSciences 14:384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ socsci14060384

Copyright: ©2025bytheauthors. LicenseeMDPI,Basel,Switzerland. Thisarticleisanopenaccessarticle distributedunderthetermsand conditionsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY)license (https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/).

Keywords: genderequality;genderbias;gendergap;STEM;ICT;artificialintelligence; education;computationalthinking

1.Introduction

Genderequalityisafundamentalhumanrightnecessaryforapeaceful,prosperous, andsustainableworld UN (2015).Unfortunately,thegendergapiscommoninoursociety, as Taboada (2024)pointedoutinrelationtothepresenceofwomeninthenewsofdigital media; Ferran-Ferreretal. (2023)referringtoWikipedia; Lunnemannetal. (2019)inthe Nobelprizehistory; Goldin (2024)relatedtowomen’spay;and QueraltJiménez (2024)in socialmediaorinleadershipofhighereducation Meza-Mejiaetal. (2023).Thisgendergap ispresentinSTEMdisciplinesandisdetrimentalforthequalityofresearchandinnovation inengineeringprojects.

Accordingto Cimpianetal. (2020),someSTEMfieldssuchasphysics,engineering,andcomputerscience(PECS),continuetobeunderrepresentedfieldsforwomen. Eurostat (2024)reportedthatonly32.8%ofSTEMgraduatesintheEuropeanUnionwere womenin2021.Inscienceandengineering,thereport“Shefigures”20241 showsthatthe persistenceofverticalsegregationinacademiccareerisverypronounced:womenrepresent only20%ofthehighestpositions,comparedto30%inallfields.Likewise,womencontinue

tobeunderrepresentedasauthorsinengineeringandtechnology,andrepresentonly9%of patentapplicants;inaddition,themajorityofteamsassociatedwithinventionsaremade upsolelyofmen.AnalyzingthecountriesoftheG20,the UNESCO (2024b)reportentitled “Changingtheequation:securingSTEMfuturesforwomen”concludesthat“noprogress hasbeenobservedinthepastdecadeintheproportionofwomenwhostudyandgraduate inSTEMsubjects”.Thisreportproposesactionscloselyrelatedtotheroleofuniversities totrainfutureprofessionalsinthisfield,andteachersfornon-universityeducation.Page 27quotesthatuntilnowuniversities“aremorefocusedonmeasuringwomen’saccessto highereducation(aboutfourinfiveuniversitiestrackgenderinapplicationrates)than trackingtheiroutcomesandsuccessrates(lessthantwo-thirdsofthemtrackwomen’s graduationratesandhaveplansaimedatclosingthegap).Informationaboutperformance andthefactorspushingwomenawayfromSTEMchoicesisessentialtobetterinform policyresponses”.

ThispaperdiscussesandanalyzeswhytherearesofewwomeninsomeSTEMfields, despiteeffortstoincreasetheirparticipation.Toexplainthissituation,wewillusethe conceptofnon-place,introducedby Augé (1995)and Calvo-Iglesias (2015).Bridging thisgendergapinSTEMisimportantbecause,as Oreskes (2020)asserts,“Scienceisa collectiveeffort,anditworksbestwhenscientificcommunitiesarediverse.Thereason issimple:heterogeneouscommunitiesaremorelikelythanhomogeneousonestobe abletoidentifyblindspotsandcorrectthem”.Thepersistenceofthegendergapin thesefieldshasledustoreviewtheactionspromotedbySpanishuniversitiesandtoask ourselveswhytheinitiativesdevelopedarenotbeingeffective.Amongthepossiblecauses, Samper-Gras (2022)considerstheandrocentricapproachthatcontinuestopermeatethe STEMfield,withoutforgettingthatwhenscientific-technicalareasareattractivefroma socioeconomicpointofview,mengoontooccupythesefieldsandwomenareleftonthe margins.Inthiscontext,wepresentanalternativeeducationalproposalthatattemptsto overcomegenderstereotypesbyrecognizingtheimportantcontributionsofwomento STEM,takingintoaccountthedifferentmotivationsforusingtechnologyandtryingto improvewomen’sself-perceptionoftheirtechnologicalskills.Intheremainingsections ofthepaper,theconceptofnon-placeinSTEMisextendedinSection 2.Section 3 collects theactionsintheSpanishuniversitiestopromotegenderequalityinSTEMdisciplines, customizedinSection 3.1 forourUniversityofSantiagodeCompostela(USC).TheSection 4 presentsanalternativeexperienceforintroducingcomputerthinkingconceptsinprimary andsecondaryschools,withtheintentiontocreateaspaceofbelongingtogirls.Section 5 showcasesanddiscussestheexperiencesinUSCpromotinggenderequalityinhigher educationandinouroutreachactivitiesinsociety.Finally,conclusionsaresummarizedin Section 6

2.STEM,aNon-PlaceforWomen

In1965,AliceRossiformulatedthequestion“Whysofew?”,initiatingalineofresearchonscience,technology,andfeminism.Inthispioneeringresearchwork,Rossi denouncedtheabsenceofwomenintheproductionofscientificknowledge,andthegenderbiasinscienceandtechnology. Tomassini (2021)listsmultipleinvestigationsthat havebeencarriedoutsincethen.Thisresearchhasservedtodelveintothefactors(influenceofstereotypes,powerrelations,andgendermodels)thatinfluencethechoice ofSTEMvocationsandtheunderrepresentationofwomeninsomeSTEMareasthat enjoygreatprestige,lowunemploymentrates,broadcareeropportunities,andhigher salaryratioscomparedtootherfields. Cheryanetal. (2025)identifiedoneofthefactors influencingthisunderrepresentationofwomen:theexistenceofmaleorganizationalculturesinwhichmasculinityisrootedininstitutionalpracticesandideas.Inthesameline,

Casadetal. (2021)pointoutthefactorsthatcontributetogenderinequalitiesandthe abandonmentofwomeninSTEMacademicfields:genderstereotypespresentinrecruitmentandpromotionprocesses,thelackofsupportivesocialnetworks,andcold,ifnot hostile,academicclimates. Msambwaetal. (2024)reviewtheempiricalevidenceonthe factorsaffectinggirls’participationinSTEMsubjects,findingthatonly10%ofthestudies indicatedthatgirls’poorparticipationcouldbeattributedtopersonalfactors,and61%to environmentalfactorslikenegativeattitudes,lackofcareerplans,lackofcollaboration, interest,poorself-concept,self-efficacy,andlowmotivation.Giventheseunwelcoming contexts,wecouldtalkaboutSTEMfieldslikeanonplaceforwomenbyreferringto theconceptintroducedbytheFrenchanthropologistMarc Augé (1995)todefinespaces ofnon-belongingandapparenttransit:“Ifaplacecanbedefinedasaplaceofidentity, relationalandhistorical,aspacethatcanbedefinedneitherasaspaceofidentitynoras relationalorhistorical,willdefineanon-place”(pp.77–78).

Thisnon-placeisespeciallymarkedinthefieldofinformationandcommunication technologies(ICT),oneofthemostmasculinizedareaswithinSTEMdisciplinesaccording tothe WorldEconomicForum (2022),whichshowsthatfemaleICTgraduatesrepresent 1.7%ofthetotalnumberofgraduatescomparedto8.7%ofmen.TheSpanishorganization UnidadMujeresyCiencia (2025)showsinits“FemaleScientistsinFigures2025”report thatComputerSciencedegreesandPhDshavealowproportionoffemalestudents(17.2%). Theseswrittenbywomencompriseonly18.8%.Wecanalsoobservethat,intheSpanish labormarket,46.3%ofprofessionalsarewomen,butifwefocusonICT,thisparticipation2 reducesto29.8%.Accordingto GonzálezRamosetal. (2017),thisraisestheneedfora structuralchangeincompanies. Berrío-Zapataetal. (2019)and Jaffe (2021)alsosuggest thatICTisanon-placeforwomen,fromwhichtheyhavebeenexcludedbyerasingtheir historicalachievementsincomputerscience,discouragingtheirparticipationineducation incomputerscienceandintheworkplace.Similarly, Collettetal. (2022)showintheir report,“TheEffectsofAIontheWorkingLifesofWomen”,thenon-placeindifferent aspectsofAIprofessionals:womencompriseonly7%ofICTpatents,onlyfounded10%of start-upsinG20countries,only20%ofacademicstaffinAI,andsoon.

ICTalsodeservesspecialattentionwithinSTEMbecausetechnologyandAIsystems areincreasinglyinteractingwithourdailyactivitiesandwillhaveanimpactonshapingfuturesociety.Therefore,the UNESCO (2023)report“Harnessingtheeraofartificial intelligenceinhighereducation”alsoexpressesconcernaboutthesignificantlylowerparticipationofwomenthanmeninSTEMfieldsandinAI-relatedacademicresearch,dueto itsimplicationsforthecreationoffairandinclusiveAIsystemsinrelationtoeducation.AI canbepredictive,whichisnormallyatypeofmachine-learningalgorithmthatanalyses dataandforecastsfutureeventsorresults,orgenerative,whichisspecializedinproducing newcontent.Inbothcases,computerslearnandrecognizepatternsfromexamples.The diversityandcharacteristicsoftheexamplesusedinthistrainingshapethefuturebehavior ofAIsystems,influencingtheirsocialimpact.AIsystemshavemanysocialimplicationsderivedfrom:who,how,andwhatdataarecollectedtotrainAIsystems? Criado-Pérez (2019). TheseimplicationsincludeintellectualpropertyofdatausedandgeneratedbyAI DornisandStober (2024);legal,ethical,andprivacyissuesofdatacollectedtotrainAI Veliz (2021); Zuboff (2019);sustainability Crawford (2021);andculturaldamage Katiraietal. (2024).Amongalltheseimplications,wemainlyfocusongenderbiasofAI. WhileAIcanbringbenefitstosomeindustrialsectors,thesesystemsposeseriousrisks tosocietywhenhumanfutureorwell-beingdependsondecisionsmadebyAIsystems. Infact,thereisastrongevidenceofgenderbiasinAIsystemswhich,togetherwiththe presenceofAIsystemsinourlives,couldperpetuateoramplifythepersistentgenderbias ofoursociety.The UNESCO (2024a)reportalertsaboutthegenderbias(intersectedby

otherbias)inthreeLargeLanguageModels(LLM),OpenAI’sGPT-2andChatGPT3-5, andMeta’sLlama2,demandingthedesignofmoreinclusive,responsibleandegalitarian AIsystems. ShresthaandDas (2022)reviewed120academicstudiesongenderbias inautomateddecision-makingsystems,mainlyinawidespreadamountoffieldslike: naturallanguageprocessing(NLP),automatedfacialanalysis,advertisement,marketing, recruitmentsystems,robotics,medicine,andmore.

GenderbiasemergesinthetextgeneratedbyLLMs,beingpropagatedthrough otherAIsystemsthatuseinternallytheLLMstoanalysetext.Otherrecentstudies foundmoregenderbiases: Simonetal. (2023)inrecruitmentsystemsfromsocialnetworkslikeLinkedInandFacebook,whichaffectstheprofessionaldevelopmentofwomen; Schiebinger (2021)inmachinetranslators,likeGoogleTranslate,where FarkasandNémeth (2022)foundgenderbiasevenforalanguagewithgendered neutralpronounssuchasHungarian; Zacketal. (2024), Ayoubetal. (2024),and Desaietal. (2024)inAIsystemsbasedonLLM,suchasChatGPT,inthehealthcare field; BuolamwiniandGebru (2018)infacerecognitionsystems; Wuetal. (2025) alsofoundgenderdifferencesintext-to-imagegenerationmodels,evenwhenneutralpromptsareused,bothintheobjectpresenceandimagelayout.Sincethese comercialsystems,suchasDALL-E,Midjourney,StableDiffusion,andAdobeFirefly,presentasexualizationofwomenandstereotypicalchildren’srepresentations, Sandoval-MartinandMartínez-Sanzo (2024)suggestedthattheycanbereinforcingtraditionalstereotypesassociatedwithgenderrolesfromchildhood,whichcanimpacttheir futuredecisionsregardingstudiesandoccupations.AnotherimpactofgenerativeAI systemsispointedoutby Engel-HermannandSkulmowski (2024),whowarnaboutthe naiverealismofAIimagegeneratorsandtheirimpactinscientificandeducationalcontexts, duetotheirlackofaccuracyandprecision.

Intheeducationalcontext, Jarquín-Ramírezetal. (2024)carriesoutacritical analysisabouttheuseofgenerativeAI,suchasChatGPT,exposingtechnooptimistic opinionsandwarningabouttheiruse Chomsky (2025),whichcandiscouragethe developmentofcriticalthinkinginstudents.Forexample,intheclinicalcontext, VicenteandMatute (2023)warnthathumanoverrelianceonAIadvicecouldleadhumanstoaccepttherecommendationsofAIalgorithms,evenwhentheyarenoticeably biasedorerroneous.Asstatedby Avraamidou (2024),scienceeducationneedshumancenteredfeministAIthatprovidetheframeworksand“toolstoprioritizealgorithmic literacyandunderstandingofhowAIperpetuatesexistingbiases,racism,andsystemsof oppression”forthedesignofsociallyjust,AI-basedcurriculathatforegroundtheidentities, subjectivities,values,andculturesofalllearners. Beltrán (2023)statesthatwomenand girlssufferdiscriminationandviolenceintechnology-relatedtasks,suchasusingsocial networks TortajadaandVera (2021),unlockingtheircellphones,orplayingvideogames MihuraLópezetal. (2023).Forexample, DelaTorre-SierraandGuichot-Reina (2025) examinedgenderrepresentationinmainstreamvideogames,concludingthatwomenare significantlyunderrepresented,relegatedtosecondaryroles,anddepictedwithsubmissive attitudes,unrealisticbodytypes,andsubjectedtovariousformsofviolence,perpetuating thetendencytomasculinizefemalefigures.Onotherhand, Lavalleetal. (2025)showthat womenwhoplayvideogamesfeelmoreintegratedintoSTEMdegreesandhavesimilar hobbiestoclassmates,and Hosein (2019)alsoshowsthatgirlswhowereheavygamers at13–14yearswerefoundtobemorelikelytopursueaSTEMdegree,althoughthiswas influencedbytheirsocio-economicstatus.However, Butcheretal. (2023)suggestthat womenwhoexperiencehostilesexismingeekcultureandcontinuetoparticipatemight haveageneraltoleranceoftoxicgeekmasculinity.Inaddition, MachadoandIshitani (2024) identifiedasetofrecommendationstobeincludedingamestostimulatewomen’sinterest

incomputing.So,thereisacontroversysurroundingtheuseoftechnologyandvideo gamestoattractgirlstoSTEMcareers.Therefore,itisnecessarytorethinkhowweteach engineering,whatexamplesweuse,andhowweassesscompetencies,inordertobuilda placeforgirlsandnotconsiderthemjustasguests.

3.TheRoleofSpanishUniversitiesPromotingGenderEqualityinSTEM

TheprocessofinstitutionalizationofequalityinSpanishuniversitiesisbasedon OrganicLaw3/2007forEffectiveEqualitybetweenWomenandMenandOrganicLaw 4/2007ontheModificationoftheOrganicLawonUniversities(LOMLOU),complemented byregionalregulations.Thisframeworkregulatesthemandatoryimplementationof equalityplansandunitsaskeyelements.OrganicLaw2/2023oftheUniversitySystem consolidatesthepresenceofequalityunitstoensurecompliancewithcurrentlegislation onequalitybetweenmenandwomen.Also,theNetworkofGenderEqualityUnitsfor UniversityExcellence(RUIGEU3 foritsacronyminSpanish)wascreatedin2009,atthethird annualmeetingofequalityunitsofSpanishuniversities.Currently,50publicuniversities and4privateuniversitiesaremembersofRUIGEU,whichconstitutesaspaceforsharing knowledge,experiences,resources,andgoodpractices,aswellasgeneratingsynergiesand jointinitiativesinthefaceofthechallengesassociatedwiththeimplementationofequality policiesintheuniversityenvironment.

In2021,RUIGEUelectedanExecutiveCommitteetoimplementtheoperatingregulationsandestablishedsixspecificworkinggroups:(1)equalityunitsandplans;(2)teaching andtrainingwithagenderperspective;(3)researchandtransferwithagenderperspective;(4)preventionandactionagainstharassment;(5)conciliationandco-responsibility; and(6)communication.Oneofthefirstactivitiesundertakenwasthediagnosisin RUIGEU (2022)about“Universityequalitypolicies”intheuniversitiesthatmakeup thenetwork.Tothisend,eachRUIGEUthematicworkinggroupwasresponsiblefor designingaquestionnaireandthesubsequentanalysisoftheresponsesofallthemember equalityunits.Inthisdiagnosis,thereareseveralspecificreferencestothepromotionof genderequalityinSTEMareas.Firstly,thepromotionofwomen’saccesstoSTEMdegrees ismentionedasoneofthelinesofaction.Inthechapterfocusedonthemainstreamingof thegenderperspectiveinresearchandtransfer,severalinitiativeswererelatedtomentoring programsforyoungfemaleresearcherssuchas:ExcellenceMentoring,forthedevelopment ofSTEMtalent;InspiraSTEAM;AlumniMentoring;FEMenGin,fortheaccompaniment andcreationofwomennetworksinengineeringandarchitecture;andFELISE.Likewise, thechapterfocusedonmainstreamingthegenderperspectiveintrainingandteaching highlightsthedifficultiestoimplementgenderperspectiveinuniversityteaching,especially inSTEMdegrees.

Thestudiesof Castaño-ColladoandVázquez-Cupeiro (2023)and AscencioCortésetal. (2025)aboutgenderequalityinhighereducationshowthat,despitetheimplementation ofequalitypoliciesandplans,institutionalandculturalresistancepersistsandlimits theireffectiveness. Alcalde-GonzálezandBelli (2024)statethatmotherhoodcontinuesto penalisewomeninacademia,becausetheacademiccareermaintainsanandrocentricvision, alinearpaththat,according Reverter (2024),doesnotallowforbreaksduetocare.In particular,intheSTEMfield, EpifanioandCalvo-Iglesias (2024)notethelackofmeasuresto addressthestructuralfactorsattherootofinequality,andrecommendtopromoteactions to:(1)fightagainstgenderstereotypesbeforeaccessinguniversity;and(2)favortheaccess andpermanenceoffemalestudentsinSTEMareas,wheretheirpresenceisintheminority. Thus,theyproposedtorecognizetheworkofstudents,teachers,andresearcherscarried outusingagenderperspective,andtomakevisibletheexcellenceoffemaleresearchersin theSTEMarea.

InitiativestopromotegendermainstreaminginSpanishhighereducationcanbeplanned andpromotedbypublicinstitutions,orbeindividualinitiativescarriedoutbyoneormore universityteachers.Withinthefirsttype, Rodríguez-JaumeandGil-González (2024)present thecollection“Guidesforgendermainstreaminginuniversityteaching”,developedby GenderEqualityPoliciesworkinggroupoftheVivesNetworkofUniversitiesandtranslated todifferentlanguages.Theseguidesproviderecommendationstointroducethegender perspectiveinbothvisibleandhiddencurriculums,includingobjectives,contents,methodologies,teachingresources,instrumentstoevaluate,andcompetencestobeachievedby thestudents,amongotherskills.Theysuggesttoreflectonsex-genderinequalitiesinthe professionalfieldofeachdiscipline,aswellastheirimpactonbothprofessionalpractice andresearch.Inaddition,theyalsoprovideguidelinesforconductinggender-sensitive research.Likewise, Peñaetal. (2021)and Lusaetal. (2024),attheUniversitatPolitècnicade Catalunya,and Marco-Simóetal. (2023),attheUniversitatObertadeCatalunya,showthe introductionofgender-relatedcompetenciesintheseuniversitiestomeettherequirements oftheCatalanAgencyforUniversityQualityAssurance.HigherPolytechnicSchoolof ZamoraalsodevelopedanengineeringwithaGenderPerspectiveproject González-Rogado etal. (2025).

RegardingindividualteachingexperiencestopromotegenderequallyinSTEMdegrees, González-GonzálezandGarcía-Holgado (2021)organizedaworkshopwithteachersaboutstrategiestogendermainstreaminginengineeringstudies; Rueda-Pascual etal. (2021)introducesgenderperspectiveinacomputerengineeringdegreeinthe UniversityofValencia;and Pérez-SánchezandSánchez-Maroño (2023)carryouta pilotexperienceinamachine-learningsubjectforamaster’sdegreeattheUniversityofCoruña.InrelationtotheAIfield, CernadasandCalvo-Iglesias (2020)and CernadasandCalvo-Iglesias (2022)proposetoincludetransversallythegenderperspective inthemajorityofsubjectsofthedegreesandmastersonAI. Calvo-Iglesiasetal. (2022) visualizesfemalemodelsrelatedtoeachthemeinanySTEMcourse. Cernadasetal. (2023) usecooperativelearningtopromoteequalityinbasiccomputingprogrammingcourses. Prendes-Espinosaetal. (2020)pointoutthescarceexistenceofscientificliteratureongender equalityeducationthroughtechnologiesinareviewofeducationalpracticesinformal contextsthatworkongenderequalityandICT(earlychildhood,primary,secondary,and highereducation). Calvo-IglesiasandAguayo-Lorenzo (2023b)compiledvariousinitiativesdevelopedbyresearchcentersanduniversitiestopromotethevisibilityofwomen inscientificandtechnologicaldisciplinesandtoserveasapoleofattractionforgirlsand youngwomentoscienceandengineering.ParticularlyinGalicia,wecanmentionthe activitiescarriedoutintheframeworkoftheEuropeanprojectICT-Go-Girls;theprogram “Exxperimentaenfemenino”inthecampusofOurense Carballoetal. (2020),Universityof Vigo;mentoringactivitiesintheFacultyofComputerScienceoftheUniversityofCoruña carriedoutbytheassociation“HelloSisters”;ortheworkcarriedoutbythe“ChairofFeminisms4.0”oftheUniversityofVigointhefightagainstdigitalsexismandthepromotion offeminisminthedigitalenvironment.

3.1.InitiativesinUniversityofSantiagodeCompostela(USC)

TheUSChasbeenapioneerintheimplementationofequalitypolicies,creatingthe GenderEqualityOffice (GEO)in2006andpreparingits“FirstStrategicPlanforEqualOpportunitiesbetweenWomenandMen”in2009.Beforedraftingitsfourthequalityplan,the USCevaluateditsthirdequalityplan(period2021–2024)inordertointroducecorrective measuresintotheplanbeingdrafted,diagnosingweaknessessuchasthelimitedincorporationofthegenderperspectiveinresearchandteaching,orthegendergapinscientific andtechnologicaldisciplines.Themostconsolidatedactionwithinthefieldofteaching,

research,andtransferistheannualcallforawardsfortheintroductionofthegenderperspectiveinteachingandresearch,whichstartedin2010.Itisworthnotingthatthisaction waschosenin2015bytheEuropeanInstituteforGenderEquality(EIGE)asoneoftheten bestgoodpracticesforpromotinggenderequalityinuniversitiesandresearchcentresfrom amongmorethan50acrosstheEuropeanUnion,andincludedintheonlinetool(GEAR) tosupportresearchorganizations(suchasuniversities)inthecreation,implementation, monitoring,andevaluationofgenderequalityplans.However,thedetailedanalysisof Aguayo-LorenzoandCalvo-Iglesias (2024)revealedagreaterparticipationoftheSocial SciencesandHumanitiesareascomparedtoSTEM.Inaddition, Alonso-Ruidoetal. (2025) foundthatgendertrainingisscarceevenineducationgrades.Inthetechnologicalfield, wehighlightthefollowingaward-winningexperiences: Calvo-Iglesias (2020)onbiographiesofSTEMwomenintheformWikipedia; CernadasandFernández-Delgado (2021)on ethicsembeddedintheteachingofmachine-learningsubjectsand Regueiraetal. (2023)on educationaltechnologythatincorporatesacriticalfeministpedagogy.

TheUSCgendergapreport4 showsthattherearegenderdifferencesamongUSC teachingandresearchstaff.Differencesareatthelevelofrepresentationinprofessional categories,inconsolidationandinpositionsofgreaterrecognition,butalsoatthelevelof participationinthespacesanddecisionmakingwithdirecteffectsontherecognitionof meritsandintheremunerationreceived.Inaddition, Alonso-ÁlvarezandDiz-Otero (2022) identifiedstrongresistancestoconciliationmeasuresinUSC.Therefore,theGEOandthe InterdisciplinaryCenterforFeministResearchandGenderStudies(CIFEX)developeda goodpracticeguidetoensurethattheworkingandmaterialconditionsofwomenatUSC aremoreappropriatefortheirprofessionalactivity.

Inrelationtothepresence,promotion,andretentionarea, Calvo-IglesiasandAguayoLorenzo (2023a)developedtheprogram“Unhaenxeñeiraoucientíficaencadacole”5 (inEnglish“Onefemaleengineerorscientistineachschool”).Itincludesscienceand technologyworkshopsaimedatprimaryschoolstudents,tomakefemalerolemodels visibleindegreesinwhichtheyareunderrepresented.Asreportedby Calvo-Iglesiasand Aguayo-Lorenzo (2023b),thousandsofstudentsparticipatedinthisprogramsinceitbegan in2016,arrivinginhistentheditionof2025toalmost200schoolsfromalloverGalicia. Thesuccessofthecomputerworkshops,whichwerealwaysverywellevaluated,ledthe authorstodesignacollectionofonlineactivitiestointroducetheconceptsofcomputational thinkingandartificialintelligencetostudentsofelementaryandsecondaryschool,tohelp createaplaceforgirlsandwomeninthisfield.Thisprogramofactivitieswillbeexplained inmoredetailinthefollowingsection.

4.AnAlternativeProposal:InformaticsandLife

Inthissection,analternativeproposaltointroducecomputationalthinking(CT)and engineeringconceptswithagenderperspectiveispresented.Section 4.1 contextualizes andjustifiesthemethodologyused,andSection 4.2 describestheonlinematerialprovided toschoolteachersinordertoallowthemtoimplementCTactivitiesintheirclassrooms.

4.1.Methodology

TheneweducationallegislativeframeworkinSpain(LOMLOE)includesCTasan essentialskill,butaccordingto González-Gallegoetal. (2025),itscorrectimplementationrequiresgivingteachersthenecessarytrainingandresources.Thegoalistoprovide studentswiththenecessaryskillstomeetthedemandsofanincreasinglytechnologicalsociety.SincethereisnospecificmethodologyforimplementingCTprojectsin educationalinstitutions,theseonlineactivitiesweredesignedtofacilitateteachers’introductionofCTinprimaryandsecondaryschool,forstudentsbetween9to15years,

incorporatingagenderperspective.Theseactivitiesarenecessaryinprimaryschool whengenderstereotypestakeroot Bianetal. (2017)andhindergirls’perceptionof theirowntechnologicalskills,eveniftheyperformsimilarlytoboys Sánchez-Canut etal. (2025). MateosSilleroandGómezHernández (2019)statethatgirls’lowselfperceptionimpactsthechoiceofprofessionalprojectsinadolescenceandearlyadulthood. Gómez-Trigueros (2023)claimsthatnegativeevaluationsintheself-perceptionoffuture femaleteachersregardingtheirabilitytoselect,assess,andusethemostappropriatedigital technologiesfortheirfutureteachingtask,couldleadtoteachers’disinterestinorunderuse oftechnologies.

Theterm computationalthinking wasdescribedin2006by Wing (2006)asafundamental skillforeveryone,involvingusingcomputerscienceconceptstosystematicallysolve problems. González-Gallegoetal. (2025)collectotherrecentdefinitions,manyofthem centeredinproblemsolving,robotics,electronics,programming,andothertechnological issues.CTcanbeaddressedeitherasathemethatiscross-curricularoverallthesubjects,or alternativelyasanindependentsubjectofcomputerscience,thatusesprimarilytechnology todevelopCTprojects.However,thestudyof González-Gallegoetal. (2025)confirmsthat girlsinsecondaryschoolshowlessinterestintechnology,anditsuseasaprimaryelement coulddampentheirinterestinthistypeofcontent.Therefore,weconsiderthatCTmustbe developedasacross-curriculartheme,designingprojectsthatincreasegirls’confidence andprovidethemwithSTEMrolemodels.

Recently, Ayusoetal. (2021)reportsthatgirlsalreadyinprimaryschoolperceive themselvestobelesscompetentthanboysinmathematics.Thiscouldalsohappenin relationtotechnologyasmentionedatthebeginningofthissection,andfurthermore, technologycouldbeuncomfortableforgirls(seeSection 2).Inthisrespect,ouractivities areplannedinawaydoesnotrequirecomputermaterialsorprogramminglanguages suchasScratch6,as Shuteetal. (2017)and Kimetal. (2013)note.Forexample,Scratch couldberelatedbystudentstovideogames,thatisaveryspecifictopicincomputer science,whichareperceivednegativebygirlsduetotheirgenderbias,asmentionedin Section 2.Videogames,accesstoonlinecommunities,andthetimespentonthemare conditionedbygenderandcangenerateaprivilegedenvironmentforboys,bothinterms ofleisureopportunities,andlearninganddevelopmentofdigitalcompetence Regueiraand Alonso-Ferreiro (2022).Theexamplesusedweregender-neutralandrelatedtoeveryday lifeasrecommendedintheInspiraSTEMguide7 forintegratingagenderperspectivein STEMdisciplinesinprimaryeducation,since,asdifferentstudiescompiledby Merayoand Ayuso (2023)conclude,girlsaremoreinterestedinSTEMsubjectswhentheyaretaught fromanappliedandpracticalperspective.

Theproposedactivitiesarerelatedtoothersubjectslikemaths,naturalandsocial sciences,andlanguages,followingexperiencesanddidacticmethodologiescommonin theteachingofthesedisciplinesateacheducationallevel.Intheseactivities,students areencouragedtodesigntechnology,ratherthanuseit,byteachingthemtheunderlying conceptssotheyunderstandhowtechnologyworks.Sincetechnologymustalwaysbeatthe serviceofpeople,wewillneedtoverifyitscorrectoperationfromdifferentperspectives, instillingcriticalthinkingbyteachinghowtechnologyworksandhowtoevaluateits correctfunctioning.

4.2.OnlineMaterialforSchoolTeachers

TheproposedactivitiesaregroupedunderthetitleAinformáticaeavida8 (“Informaticsandlife”),whichisavailabletoallGalicianschoolsinthelocallanguageunder freeregistration.Theonlinematerialenclosesinstructionstoteachers,togetherwithother materialtodownloadlikeimages,files,presentations,softwaretools,videos,andcomputer

programsforanadvanceduseofthematerialinthelasttwoactivities.Asmentioned,CT andAIconceptsareintroducedasanextensionofhowhumanssolvedifferentsituationsin life,andrelatethemtothecontentsoflanguage,mathematics,ornaturalsciencesspecific tothateducationalstage,usingplayfulandfunactivities.Inaddition,wehavetriedto findactivitiesthatshowtheimportanceofcomputinginhelpingotherdisciplinesand improvingsocietytomotivategirls MerayoandAyuso (2023).Wealsowanttohighlight thattheactivitiesthatusetechnologynevercollectdatafromstudentsorinvadetheirright toprivacy.

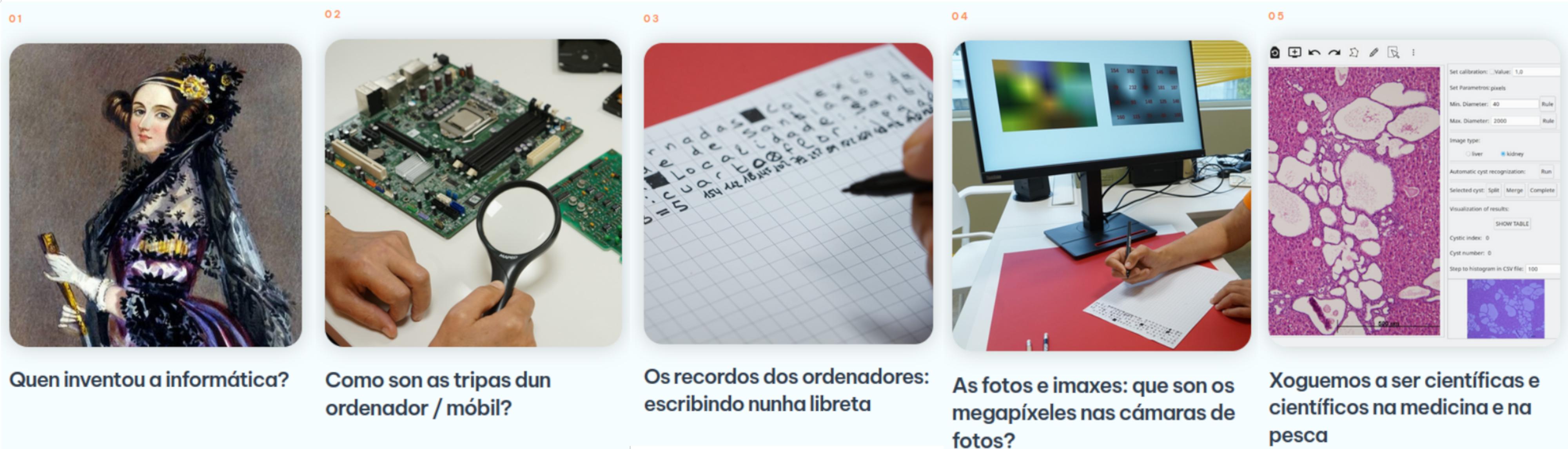

Engineeringisanancientdiscipline,predatingcomputersandrobots,thatproduces devicesandservicestoimprovepeople’slives.CTisrootedinallengineeringdisciplines. Webelieveitisimportanttousetheword“engineering”fromchildhood,sothatgirls associateengineeringwiththisusefulknowledge Paderewski-Rodríguezetal. (2017). Typically,thesuggestedactivitiesincludeexercisesofvaryingdifficultylevels.Forthe youngeststudents,teachersshouldpickuptheonesthatdonotrequiretechnologyintheir development.Fortheoldestones,teacherscandevelopthemostadvancedexercises,in whichstudentscandeveloptheirfirstprofessionalcomputerprograms.Theprovided materialgivesagerecommendationsforeachactivity.Insteadofusing Scratch,wepropose theuseofprofessionalprogramminglanguageslike Python9,thevocabularyofwhichis veryclosetohumanlanguages,specificallytheEnglishlanguage.So,activitiesforthe oldeststudentsaredevelopedinPythoninordertolearnprogrammingasataskofwriting astoryinanewlanguage,normallyinsecondaryschool.Inthisway,studentsacquire digitalcompetence,butuseitasaoccasionaltoolatourservicetosolveproblems,andnot asaprominenttoolintheclassroom.Figure 1 showsascreenshotofthewebpage.Theten activitiesincludedare:

1. Queninventouainformática?(“Whoinventedcomputing?”):addressestherole ofwomeninthebirthofcomputerscience,makingvisiblemanyfemalescientists andprofessionalsinthisfield.Italsoincludesmaterialsandinstructionsfordevelopinggamesthatexploretheinspirationandimportanceofsomefemalescientists’ inventions,usingtheparadigmofunpluggedcomputationalthinking.

2. Comosonastripasdunordenador?(“Whataretheinsidesofthecomputerlike?”): explainstheoperationandpartsofacomputerbyestablishinganalogiesbetweenthe computerhardwareandourhumanbody.Itrelatesengineeringtobiology,whichis frequentlyveryenjoyedbygirls.

3. Osrecordosdosordenadores:escribindonunhalibreta(“Memoriesofcomputers: writinginanotebook”):usesasquarednotebookpagetoexplaintheprocessof storinginformationonacomputer’smemoryorharddisk.

4. Asfotoseimaxes:quesonosmegapíxelesnascámarasdefotos?(“Photosandimages: whataremegapixelsincameras?”):definestheconceptofpictureelement(pixel) inthedigitalimagesanditscapacitymeasures,relatingimagesizewithcamera characteristics.Thestorageofcolorimagesintheharddiskisalsointroduced.

5. Xoguemosasercientíficasecientíficosnamedicinaenapesca(“Let’splayatbeing scientistsinmedicineandfishing”):theobjectiveofthisactivityistoshowthe interrelationofcomputersciencewithothersciences,suchasmedicineorbiology.As otherengineeringfields,computerscienceprovidestoolstohelpotherdisciplines. Theworkenvironmentofscientistsinbiomedicineandbiologyissimulatedthrough tworesearchsoftwareproductssharedwithstudents,STERAppandCystAnalyser, describedby Mbaidinetal. (2021)and Cordidoetal. (2020),respectively.Software toolsandvideoscanbedownloadedtosimulatethediaryworkofresearchersinthe biomedicalandfisheringlabs.

6. Medindocélulascontandopuntos(píxeles)nasimaxes(“Measuringcellsbycounting pixelsinimages”):theobjectivehereistomakestudentsawarethatalltheresults providedbyacomputerprogramhavetobeverifiedwiththeestablishedmethod, thatis,italwayshastobevalidatedbypeopleinordertoensurethatcalculations areright.Inthiscase,studentsvalidatethattheCystAnalysersoftwaremeasures correctlytheareaofirregularobjectsinimages.

7. Aescaladixital:medindoarealidadequenosrodea(“Thedigitalscale:measuring therealityaroundus”):thisactivityintroducestheconceptofcalibrationtorelate pictureelementswithtruthmeasuresofobjects,inthiscase,theareaofgeometric shapesinimages.Providematerialsandinstructionstodiscusswithstudentshow humansmeasurethesurfaceareaofgeometricshapecomparetohowcomputersdo.

8. Medindoarealidadenascienciasnaturaisesociais(“Measuringrealityinnaturaland socialsciences”):theconceptofadigitalscaleallowsustomeasureeveryobjectinthe worldwhichcanbecapturedbyadigitalcamera.Thistechnologyisusedtomeasure theareaofaplantleaf,andtheextensionofaregiononamap.

9. Enquesepareceuncontoaunprograma?(“Howisastorysimilartoacomputer program?”):ICTprofessionalsuseprogramminglanguagestobuildcomputerprograms.Ourgoalsaretointroducetheconceptofprogramminglanguageasifitwere thelearningofanotherhumanlanguage,thatpeopleusestocommunicatewitha computer.

10. Queéaintelixenciaartificial?(“Whatisartificialintelligence?”):Thisactivityis openaccess10.Wemodelacomputerprogramasaboxthatreceivesdatatoprovide ananswer.Inclassicalprogramming,theprogrammersetsrulestotheprogramin ordertoachieveapositiveansweroroutcometotheinputdata.Supervisedmachinelearning(SML)algorithmsareaspecifictypeofcomputerprogram,whichrepresent themajorityofprogramswithinAI.InSMLprograms,theprogrammergivesto theboxexamples(data)andthedesiredanswer(outcome)inorderforthebox(AI system)tolearntherulestoproducetheoutcomefromthedata,inaprocesscalled training.OncetheboxorAIalgorithmistrained,itcanoperatetogiveanswers toexamplesnotseeninthetraining.Manypeopleinsocietydonotunderstand thedifferencesbetweenclassicalandSMLprograms.Thisactivityexplainsboth conceptswithoutusingtechnology,throughthesortingofspaghettibytheirlength (classicalprogramming),andthedistancetraveledbyaballkickedbyagirl(ML program).Dependingontheeducationallevel,thisactivitycanbeextendedby puttingonamini-playintheclassroomwiththestudents,orcreatingprogramswith aprofessionalprogramminglanguagelikePython11 fortheoldeststudents.Since AIsystemsintroducebiasindifferentways,thisactivity,usingcommonexamples, explainshowthedifferenttypesofbiasareencodedintheMLalgorithms.Gender biasisnormallyduetobiasindatausedfortraining,andinthecriteriaforthe outcomeverification.Otherbiasesareduetothestatisticalrepresentationofminority groups.Theprovidedexamplesallowustoreflectwiththestudentsaboutgender biasinAIsystems,followingtherecommendationof VicenteandMatute (2023).

Figure1. IlustrativeimagewiththetenactivitiesoftheprogramAinformáticaeavida(“Informatics andlife”).Thenumbersinthefigurearetheactivities:(01)Whoinventedcomputing?;(02)Whatare theinsidesofthecomputerlike?;(03)Memoriesofcomputers:writinginanotebook;(04)Photosand images:whataremegapixelsincameras?;(05)Let’splayatbeingscientistsinmedicineandfishing; (06)Measuringcellsbycountingpixelsinimages;(07)Thedigitalscale:measuringtherealityaround us;(08)Measuringrealityinnaturalandsocialsciences;(09)Howisastorysimilartoacomputer program?;and(10)Whatisartificialintelligence?.

5.ResultsandDiscussion

InFebruary2024,theCentroSingulardeTecnoloxíasIntelixentesdaUSC(CiTIUS)12 madethefirsteditionofthe Ainformáticaeavida activityprogramavailabletoschools. Only15schoolsregisteredforthisfirstedition.InMarch2024,Dr.Cernadasparticipated inthe ArtificialIntelligenceandEducationSymposium withaninvitedplenarytalktodiscuss genderbiasesinartificialintelligencesystemsandpresentedtheprogram Ainformática eavida totheeducationalcommunity.TheconferencewasorganizedbytheGalician regionalgovernment(XuntadeGalicia)andwasattendedby610non-universityteachers. InMay2024,Dr.Cernadashasconductedatrainingcoursetoprimaryandsecondary schoolteachers.Thiscourse,entitled Gettingstartedwithartificialintelligenceineducation wasorganizedbytheRegionalCentreforTrainingandInnovationofourregion(Xunta deGalicia).BothparticipationswereevaluatedbyXuntadeGaliciathroughasatisfaction questionnaireamongteachers.Inthefirstsymposium,therewere610teachersenrolled and353filledthequestionnaire.Inthesecondcourse,therewere18teachersenrolledand 9filledthesatisfactionquestionnaire.Table 1 reportsthefourquestionsofthequestionnaire withtheirscores(rangedfrom0to5)andaverage/deviationvalues.Allthescoresare closeto4,withanaveragevalueabove4thatmeansapositivereceptionofteachersfor alternativeinitiativestothepredominantteachingofAI.

Table1. Questionsandscoresinthequestionnaire.

QuestionnairePlenaryCourse No.Answers3539

QuestionScore(0–5)

Adaptationofcontent,time,andmediatotheattendee’sneeds3.893.88 Masteryofthesubjecttaught4.384.38 Communicationskills3.934.14 Methodologicaladequacyandresourcesused3.903.71 Average4.034.02 Deviation0.240.29

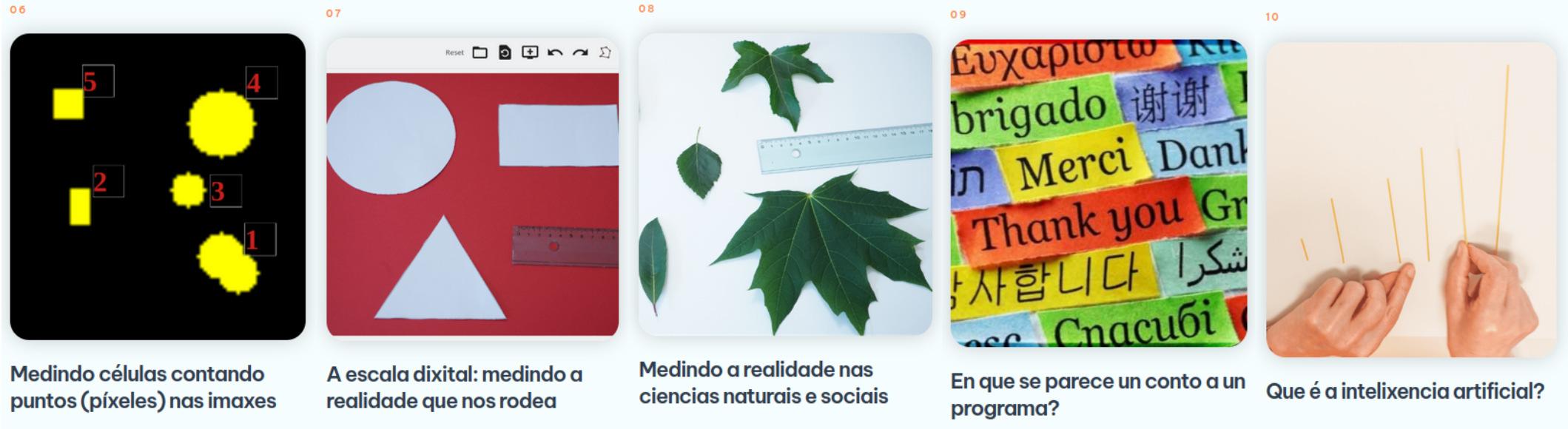

Figure 2 showsphotographsdevelopingworkshopsinaschoolclassroomsandscreenshotsofthematerialsoftheprogram.Attheendoftheworkshops,wehadinformal conversationswiththeschoolteacherstogathertheirfeedback.Theyrecognizedthatthis wayofapproachingthesubjectofcomputerscienceandartificialintelligenceisnotthe usualone.Ingeneral,theyweresurprisedbecauseweproposeanalternativetoworkin theclassroomonconceptsthatareveryrelevanttodayandnecessaryforthetrainingof students,butwithacompletelydifferentapproach,prioritizingthecriticalandconceptual learningthatunderliesthetechnology,insteadofbeingenduserswhoworkwiththetools asblackboxesandwithoutunderstandingtheirinternalfunctioning.Webelievethatthisis awaytoempowerstudentsandcanbeabeginningtodismantletheoppressivetoolsofthe technopatriarchyfollowingFreire’spedagogy.Wedonotusecommercialsoftwarebecause, toparaphraseAudreLorde,themaster’stoolsdonotservetodismantlethemaster’shouse. Furthermore,byusingtechnologyasanothertool,onthesamelevelasapenciloranotebook,wecangeneratecooperativeworkenvironmentsbasedongenderequalitytocreate equalopportunitiesforboysandgirls.Goodexperienceshavealsobeengainedinprevious activitieswithyoungerstudents,wheretheconceptsfromactivities2and9wereapplied tobuildarobotwithourbodies CernadasandFernández-Delgado (2025).Ourcomputer programwasacookierecipe,andweranitwiththecookingrobot(ourbodies)tomake thecookies,seethechapter“Lainteligenciaartificialexplicadadesdelasprimerasetapas educativas”intheonlinebook Inteligenciaartificialenlaeducación.Desarrolloyaplicaciones13 (pp.66–78).Theseexperiencessuggest,aspointedoutby Fernandez-Moranteetal. (2020), thatthegirlsprefercollaborativeandgroupwork.Thepreferencesofgirlsforcooperativelearningwasalsoobservedteachingbasicprogrammingcoursesinhighereducation Cernadasetal. (2023).Asnotedby Cheryanetal. (2025),genderdisparitiescanbereduced byincreasingthepositiveexperiencesofwomenandgirlsinSTEM.Thisexperiences canbeimplementedusingneutralexamplesorthoseclosertoagirl’slife.Accordingto Hallströmetal. (2015),girlsandboyslearntoapproachandhandletechnologydifferently. Forexample,therobotbuiltbyourbodycanbeusedtodanceaprogram(thechoreographyisthecomputerprogram),similarto SepúlvedaDuránetal. (2025),whocarryout aninterventionfocusedonthedevelopmentofCTthroughbodyexpression,music,and movementwithelementaryschoolstudents.

PhotographdevelopingworkshopsinaschoolclassroomandscreenshotsofAinformática eavidamaterials.

OnFebruary2025,CiTIUSopenedtheregistrationtothesecondeditionofthe A informáticaeavida activitiesprogramtocelebratetheInternationalDayofWomenand GirlsinScience.BytheendofMarch,morethan30educationalcentersfromGaliciahad registeredfortheprogram.Wehaveplannedtodesignaspecificquestionnairetocollect theteachersandschoolperceptionattheendoftheacademicyear.Thishighparticipation showsthatthereisaneedfortrainingbynon-universityteacherstomeetthenewtraining needsindigitalskillsandthatresourcesarescarce.Though,INTEF(NationalInstituteof EducationalTechnologiesandTeacherTraining)haslaunchedaMOOCcourseInitiationto RoboticsandProgrammingwithagenderperspective.Therearealsoexperiencesinthe literature Valdeolivasetal. (2022)of,throughanaction-researchexperience,workingon thedesignofdidacticactivitiesonaspectsrelatedtogenderandeducationalroboticsto improvelearningintheuniversityclassroombasedonarealeducationalcontext.

6.Conclusions

Manyinternationalandnationalreportsanalyzethecausesofthelowerparticipation ofwomenintheSTEMfields.Despiteallinstitutionaleffortstoachievefullgenderequality, differencesinfemalerepresentationintheSTEMfieldsstillpersistasanon-place,mainlyin areassuchasICT,computerscienceandengineering,orartificialintelligence.AIsystems andtechnologyingeneralaretoolsthatwerelyonmoreandmoreinourdailylives. However,theirusemayhavesocialrisksthatarenotyetsufficientlystudied,including genderbias.

ThispaperalsoanalysestheroleofSpanishuniversitiesinpromotinggenderequality inacademiaand,specifically,intheSTEMfield.Toovercomethissituation,wepropose introducingengineeringcontentfromearlychildhoodwithagenderperspective,exercising cooperationbetweenbothgendersonequalterms,andrethinkinghowengineeringis introducedinschoolsandwhatexamplesweuse.Basedontheexperienceinschoolswith face-to-faceworkshopsdrivenbythegenderequalityoffice,weproposeanalternativeway ofintroducingcomputerthinkinginprimaryandsecondaryschoolswithAinformáticaea vida(“Informaticsandlife”)program.Theseactivitiestakeintoaccountintheirdesignthat thebehaviorandenthusiasmofgirlsandboysintheclassroomisinfluencedbythetypeof

activitybeingcarriedoutandproposeexamplesclosetoeverydaylife.Theseprogramhas attractedtheinterestofthenon-universityteachers,whohaverateditverypositivelyboth throughthesatisfactionsurveyandinthecommentsinpersonorbye-mail.However,a moreappropriateevaluationinstrumentisneededtobeabletodeterminetheimpactof theeducationalproposal.Therefore,inthenexteditions,twoquestionnaireswillbesentto theparticipatingcenters,aninitialonetoascertainthereasonsthatledthemtoparticipate inthisprogramandtheirexpectations,andanotheronetoknowtheirassessment.Inthe future,wewillcontinuewiththeseactivities,tryingtoimprovethemwiththecontributions ofthenon-universityteacherswhohaveputtheseactivitiesintopractice.Atthesame time,webelievethattheseactivitiescouldbeenrichedbyshowingnotonlyfemaleSTEM referentsbutalsomaleallies,toofferboysreferentsinthenewmasculinities.

Inaddition,itwillbenecessarytointroducethegenderperspectiveatallstagesof education,fromchildhoodtohighereducation,whichwillvaluethestrengthsofgirls andwomenintheSTEMfields—aneducationaimedatinclusionofallgendersgrowing andrespectingeachother.Theseinitiativeswillnotbeabletosucceediftheviolence, harassment,professionalcontempt,anddiscriminationthatwomenendureinSTEM environmentsarenoteliminated.

AuthorContributions: Conceptualization,E.C.andE.C.-I.;methodology,E.A.,E.C.-I.andE.C.;software,E.C.andM.F.-D.;validation,E.A.andE.C.;formalanalysis,E.A.,E.C.-I.andE.C.;investigation, E.A.,E.C.-I.andE.C.;resources,M.F.-D.andE.C.;datacuration,M.F.-D.andE.C.;writing—original draftpreparation,E.A.,E.C.-I.andE.C.;writing—reviewandediting,E.C.,E.A.,E.C.-I.andM.F.-D.; supervision,E.C.andE.C.-I.;projectadministration,E.C.;fundingacquisition,E.C.Allauthorshave readandagreedtothepublishedversionofthemanuscript.

Funding: ThisworkhasreceivedfinancialsupportfromtheXuntadeGalicia—Conselleríade Cultura,Educación,FormaciónProfesionaleUniversidades(CentrodeinvestigacióndeGaliciaaccreditation2024–2027,ED431G-2023/04)andtheEuropeanUnion(EuropeanRegionalDevelopment Fund—ERDF).

InstitutionalReviewBoardStatement: Notapplicable.

InformedConsentStatement: Notapplicable.

DataAvailabilityStatement: Nonewdatawerecreated.

Acknowledgments: Weacknowledge:theCiTIUSforhostingtherepositoryofactivitiesinthe program Ainformáticaeavida;AdriánCordido,researcheroftheMedicineSchoolofYaleUniversity (USA)bytheinformationalvideoaboutgeneticdiseasesandresearchmethodologyinthebiomedical field;RosarioDomínguezPetitandSoniaRábadeUberos,researchersofSpanishResearchCouncil (CSIC)bytheinformationalvideoaboutthemanagementofmarineresourcesandtheresearch methodologyusedinfisherylabs;andthecommunicationareaofCiTIUS,AndrésRúizHiedra, SandraBlancoVázquezandNoeliaGallegoCampos,bythephotosoftheprogram.

ConflictsofInterest: Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Abbreviations

Thefollowingabbreviationsareusedinthismanuscript:

STEMScience,technology,engineering,andmaths ICTInformationandcommunicationtechnologies

AIArtificialintelligence

CTComputationalthinking

GPTGenerativepre-trainedtransformer

Notes

1 https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/592260 (accessedon12June2025).

2 InformesobreEmpleabilidadyTalentoDigital2024.

3 ReddeUnidadesdeIgualdaddeGénerodeExcelenciaUniversitaria.

4 https://cifex.usc.gal/actividade/informe_fenda_salarial (accessedon12June2025).

5 https://unhaencadacole.gal/ (accessedon12June2025).

6 https://scratch.mit.edu/ (accessedon12June2025).

7 Guíaparadocentes:IntegracióndelaperspectivadegéneroenlasdisciplinasSTEMdeeducaciónprimaria.Link: https://inspirasteam.net/guias-docentes/ (accessedon12June2025).

8 https://tec.citius.usc.es/ainformaticaeavida/ (accessedon12June2025).

9 https://www.python.org/ (accessedon12June2025).

10 https://tec.citius.usc.es/ainformaticaeavida/que-e-a-intelixencia-artificial/ (accessedon12June2025).

11 SeeNote9.

12 https://citius.gal/news/news/citius-publishes-a-informatica-e-a-vida-workshop-to-promote-equality-in-technology-learning/ (accessedon12June2025).

13 https://oei.int/oficinas/secretaria-general/publicaciones/inteligencia-artificial-en-la-educacion-desarrollo-y-aplicaciones/ (accessedon12June2025).

References

Aguayo-Lorenzo,Eva,andEncinaCalvo-Iglesias.2024.Clavesparaunadocenciauniversitariaconperspectivadegénero.In Calidade InnovaciónPedagógica:ExperienciasDocentesyTecnológicasAplicadasalAula.Madrid:Dykinson,pp.172–85. Alcalde-González,Verna,andSimoneBelli.2024.Managingthework-careconflictinthescientific-academicfield:Aqualitativestudy ontheexperiencesofwomenresearchersinSpain. RevistaEspanoladeInvestigacionesSociologicas 188:3–20.[CrossRef] Alonso-Álvarez,Alba,andIsabelDiz-Otero.2022.¿Nadandocontracorriente?Resistenciasalapromocióndelaconciliaciónenlas universidadesespañolas. RevistaInternacionalDeSociología 80:e208.[CrossRef]

Alonso-Ruido,Patricia,AlexandraMiroslavaRodríguez-Gil,IrisEstévez,andBibianaRegueiro.2025.Igualdaddegéneroysexismo: unamiradadesdelaperspectivadelestudiantadodeCienciasdelaEducación[Genderequalityandsexism.Theviewsof EducationSciencesstudents]. EDUCAR 61:53–68.[CrossRef]

AscencioCortés,MaríaSoledad,YasnaAnabalónAnabalón,andEmmanuelVega-Román.2025.¿Cambioinstitucionaldegéneroen EducaciónSuperior?Resistenciasyperspectivasdesdeunarevisiónsistemáticadelaliteraturacientífica[InstitutionalGender ChangeinHigherEducation?ResistanceandPerspectivesfromaScopingReviewofLiterature]. RevistaFuentes 27:15–30. [CrossRef]

Augé,Marc.1995. Non-Places:IntroductiontoanAnthropologyofSupermodernity.London:Verso. Avraamidou,Lucy.2024.CanwedisruptthemomentumoftheAIcolonizationofscienceeducation? JournalofResearchinScience Teaching 61:2570–74.[CrossRef]

Ayoub,NoelF.,KarthikBalakrishnan,MarcS.Ayoub,ThomasF.Barrett,AbelP.David,andStaceyT.Gray.2024.Inherentbiasinlarge languagemodels:Arandomsamplinganalysis. MayoClinicProceedings:DigitalHealth 2:186–91.[CrossRef]

Ayuso,Natalia,ElenaFillola,BelénMasiá,AnaC.Murillo,RaquelTrillo-Lado,SandraBaldassarri,EvaCerezo,LauraRuberte, M.DoloresMariscal,andMaríaVillarroya-Gaudó.2021.GenderGapinSTEM:ACross-SectionalStudyofPrimarySchool Students’Self-PerceptionandTestAnxietyinMathematics. TransactionsonEducation 64:40–49.[CrossRef] Beltrán,Marta.2023. MR.INTERNET:CómoseRelacionanlaTecnologíayelGéneroycómoteAfectaaTi.Pamplona:NextDoorPublishers. Berrío-Zapata,Cristian,EsterFerreiradaSilva,TamaradeSouzaBrandãoGuaraldo,andÂngelaMariaGrossideCarvalho.2019. ExclusãoDigitaldeGênero:quebrandoosilêncionaCiênciadaInformação.[Exclusióndigitaldegénero:Rompiendoelsilencio enlacienciadelainformación]. RevistaInteramericanadeBibliotecología 43:eRv1/1–eRv1/14.[CrossRef]

Bian,Lin,Sarah-JaneLeslie,andAndreiCimpian.2017.Genderstereotypesaboutintellectualabilityemergeearlyandinfluence children’sinterests. Science 355:389–91.[CrossRef]

Buolamwini,Joy,andTimnitGebru.2018.Gendershades:Intersectionalaccuracydisparitiesincommercialgenderclassification. ProceedingsofMachineLearningResearch 81:77–91.

Butcher,Madeleine,ElizabethL.Cohen,ChristineE.Kunkle,andDanielTotzkay.2023.Geekgirltoday,scientisttomorrow?Inclusive experiencesandefficacymediatethelinkbetweenwomen’sengagementinpopulargeekcultureandstemcareerinterest. InternationalJournalofScienceEducation 13:276–91.[CrossRef]

Calvo-Iglesias,Encina.2015.Elno-lugardelascientíficas.In Locas,escritorasypersonajesfemeninoscuestionandolasnormas:XIICongreso InternacionaldelGrupodeInvestigaciónEscritorasyEscrituras.Sevilla:Alciber,pp.212–20.

Calvo-Iglesias,Encina.2020.PreparingbiographiesofSTEMwomeninthewikipediaformat,ateachingexperience. IEEERevista IberoamericanadeTecnologíasdelAprendizaje/ 15:211–14.[CrossRef]

Calvo-Iglesias,Encina,andEvaAguayo-Lorenzo.2023a.PromotingFemaleSTEMVocationsWithintheSDGFramework.Paper presentedatthe17thInternationalTechnology,EducationandDevelopmentConference,Valencia,Spain,March6–8.pp.2245–48. [CrossRef]

Calvo-Iglesias,Encina,andEvaAguayo-Lorenzo.2023b.TalleresonlineparafomentarlasvocacionesCTIMfemeninas.In Educación, Tecnología,InnovaciónyTransferenciadelConocimiento.Madrid:Dykinson,pp.177–86.

Calvo-Iglesias,Encina,EvaCernadas-García,andManuelFernández-Delgado.2022.ProvidingfemalerolemodelsinSTEMhigher educationcareers,ateachingexperience.PaperpresentedattheXIIInternationalConferenceonVirtualCampus,Arequipa, Perú,September29–30.pp.1–4.[CrossRef]

Carballo,Julia,AlmaMaríaGómez-Rodríguez,andMaríadelasNievesLorenzo-González.2020.Providingfemalemodelsand promotingvocations:Apracticalexperienceinstemfields. IEEERevistaIberoamericanadeTecnologiasdelAprendizaje 15:317–25. [CrossRef]

Casad,BettinaJ.,JillianE.Franks,ChristinaE.Garasky,MelindaM.Kittleman,AlannaC.Roesler,DeidreY.Hall,andZacharyW. Petzel.2021.Genderinequalityinacademia:ProblemsandsolutionsforwomenfacultyinSTEM. JournalofNeuroscience Research 99:13–23.[CrossRef]

Castaño-Collado,Cecilia,andSusanaVázquez-Cupeiro.2023.Resistanceandcounter-resistancetogenderequalitypoliciesinSpanish universities. Papers 108:e3105.[CrossRef]

Cernadas,Eva,andEncinaCalvo-Iglesias.2020.Genderperspectiveinartificialintelligence(AI).In ProceedingsoftheVIIIInternational ConferenceonTechnologicalEcosystemsforEnhancingMulticulturality,Salamanca,Spain,21–23October2020.EditedbyFrancisco García-PenalvoandAliciaGarcía-Holgado.ACMIntlConfProcSeries.Piscataway:IEEE,p.4.[CrossRef]

Cernadas,Eva,andEncinaCalvo-Iglesias.2022.Perspectivadegéneroeninteligenciaartificial,unanecesidad. CuestionesdeGénero: DelaIgualdadylaDiferencia 117:111–127.[CrossRef]

Cernadas,Eva,andManuelFernández-Delgado.2021.Embeddedethicstoteachmachinelearningcourses:Anexperience.Paper presentedattheXIInternationalConferenceonVirtualCampus,Salamanca,Spain,September30–October1,pp.1–4.[CrossRef]

Cernadas,Eva,andManuelFernández-Delgado.2025.Experiencesteachingmachinethinkingwithgenderperspectiveinschools.In VirtualCampusesandSmartE-LearningEnvironments.Singapore:SpringerNature,p.10.

Cernadas,Eva,ManuelFernández-Delgado,MarLorenzo,andMaríaFerraces.2023.Promotingequalityinhighereducationcomputer programmingcoursesthroughcooperativelearning.PaperpresentedattheXIIIInternationalConferenceonVirtualCampus Porto,Portugal,September25–26.pp.1–4.[CrossRef]

Cheryan,Sapna,EllaJ.Lombard,FasikaHailu,LinhN.H.Pham,andKatherineWeltzien.2025.Globalpatternsofgenderdisparities instemandexplanationsfortheirpersistence. NatureReviewsPsychology 4:6–19.[CrossRef] Chomsky,Noam.2025.NoamChomsky:TheFalsePromiseofChatGPT. TheNewYorkTimes.Availableonline: https://www.nytimes. com/2023/03/08/opinion/noam-chomsky-chatgpt-ai.html (accessedon12June2025).

Cimpian,JosephR.,TaekH.Kim,andZacharyT.McDermott.2020.Understandingpersistentgendergapsinstem. Science 368: 1317–19.[CrossRef]

Collett,Clementine,GinaNeff,andLiviaGouvea.2022. TheEffectsofAIontheWorkingLifesofWomen.Paris:UNESCO.[CrossRef] Cordido,Adrián,EvaCernadas,ManuelFernández-Delgado,andMiguelA.García-González.2020.Cystanalyser:Anewsoftware toolfortheautomaticdetectionandquantificationofcystsinpolycystickidneyandliverdisease,andothercysticdisorders. PLoSComputationalBiology 16:1–18.[CrossRef]

Crawford,Kate.2021. TheAtlasofAI:Power,Politics,andthePlanetaryCostsofArtificialIntelligence.NewHaven:YaleUniversityPress. Criado-Pérez,Caroline.2019. InvisibleWomen:DataBiasinaWorldDesignedforMen.NewYork:AbramsPress. DelaTorre-Sierra,AnaMaría,andVirginiaGuichot-Reina.2025.Womeninvideogames:Ananalysisofthebiasedrepresentationof femalecharactersincurrentvideogames. SexualityandCulture 29:532–60.[CrossRef]

Desai,Pooja,HaoWang,LindyDavis,TimothyM.Ullmann,andSandraR.DiBrito.2024.Biasperpetuatesbias:ChatGPTlearns genderinequitiesinacademicsurgerypromotions. JournalofSurgicalEducation 81:1553–57.[CrossRef][PubMed] Dornis,TimW.,andSebastianStober.2024. CopyrightLawandGenerativeAITraining—TechnologicalandLegalFoundations.Baden-Baden: NOMOSVerlag.Availableonline: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4946214 (accessedon12June2025). Engel-Hermann,Patricia,andAlexanderSkulmowski.2024.Appealing,butmisleading:AwarningagainstanaiveAIrealism. AI Ethics 5:3407–13.[CrossRef]

Epifanio,Irene,andEncinaCalvo-Iglesias.2024.Actionsforgenderequalityinscientific-technicalareasinSpanishuniversities. EducaciónXX1 27:19–36.[CrossRef]

Eurostat.2024.WomenTotalledAlmostaThirdofSTEMGraduatesin2021.Availableonline: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/ products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20240308-2 (accessedon12June2025).

Farkas,Anna,andRenátaNémeth.2022.Howtomeasuregenderbiasinmachinetranslation:Real-worldorientedmachinetranslators, multiplereferencepoints. SocialSciences&HumanitiesOpen 5:100239.[CrossRef]

Fernandez-Morante,Carmen,BeatrizCebreiroLópez,andLorenaCasalOtero.2020.Capacitarymotivaralasniñasparasu participaciónfuturaenelsectorTIC.Propuestadecincopaíses[Trainandmotivategirlsfortheirfutureparticipationintheict sector.Proposalfromfivecountries]. Innoeduca.InternationalJournalofTechnologyandEducationalInnovation 6:115–27.[CrossRef]

Ferran-Ferrer,Núria,Juan-JoséBoté-Vericad,andJuliàMinguillón.2023.Wikipediagendergap:Ascopingreview. Profesionaldela Información 32:1–13.[CrossRef]

Goldin,Claudia.2024.NobelLecture:AnEvolvingEconomicForce. AmericanEconomicReview 114:1515–39.[CrossRef]

González-Gallego,Sofía,MarianaHernández-Pérez,JoséA.Alonso-Sánchez,PedroM.Hernández-Castellano,andEduardoG. Quevedo-Gutiérrez.2025.Acriticalexaminationoftheunderlyingcausesofthegendergapinstemandtheinfluenceof computationalthinkingprojectsappliedinsecondaryschoolonstemhighereducation. FrontiersinEducation 10:1–24.[CrossRef]

González-González,CarinaS.,andAliciaGarcía-Holgado.2021.Strategiestogendermainstreaminginengineeringstudies:A workshopwithteachers.PaperpresentedattheXXIInternationalConferenceonHuman-ComputerInteractionMálaga,Spain, September22–24.pp.1–5.[CrossRef]

GonzálezRamos,AnaM.,NúriaVergésBosch,andJoséSaturninoMartínezGarcía.2017.Womeninthetechnologylabourmarket. RevistaEspañoladeInvestigacionesSociológicas 159:73–90.[CrossRef]

González-Rogado,AnaBelén,AnaBelénRamos-Gavilán,MaríaAscensiónRodríguez-Esteban,andAliciaGarcía-Holgado.2025. Perceptiondisparitybetweenwomenandmenonthegendergapinstemataspanishuniversity. IEEERevistaIberoamericanade TecnologiasdelAprendizaje 20:1–11.[CrossRef]

Gómez-Trigueros,IsabelMaría.2023.ValidacióndelaescalaTPACK-DGGysuimplementaciónparamedirlaautopercepcióndelas competenciasdigitalesdocentesylabrechadigitaldegéneroenlaformacióndelprofesorado[Validationofthetpack-dggscale anditsimplementationtomeasureself-perceptionofteacherdigitalcompetenciesandthedigitalgendergapinteachertraining]. Bordon.RevistadePedagogia 75:151–75.[CrossRef]

Hallström,Jonas,HeleneElvstrand,andKristinaHellberg.2015.Genderandtechnologyinfreeplayinswedishearlychildhood education. InternationalJournalofTechnologyandDesignEducation 25:137–49.[CrossRef]

Hosein,Anesa.2019.Girls’videogamingbehaviourandundergraduatedegreeselection:Asecondarydataanalysisapproach. ComputersinHumanBehavior 91:226–35.[CrossRef]

Jaffe,Sarah.2021. WorkWon’tLoveYouBack:HowDevotiontoOurJobsKeepsUsExploited,Exhausted,andAlone.NewYork:Bold TypeBooks.

Jarquín-Ramírez,MauroRafael,HéctorAlonso-Martínez,andEnriqueDíez-Gutiérrez.2024.AlcancesylímiteseducativosdelaIA: ControleideologíaenelusodeChatGPT[EducationalscopeandlimitsofAI:ControlandideologyintheuseofChatGPT]. DIDAC 84:84–102.[CrossRef]

Katirai,Amelia,NoaGarcia,KazukiIde,YutaNakashima,andAtsuoKishimoto.2024.Situatingthesocialissuesofimagegeneration modelsinthemodellifecycle:Asociotechnicalapproach. AIEthics 5:1769–86.[CrossRef]

Kim,Byeongsu,TaehunKim,andJonghoonKim.2013.Paper-and-pencilprogrammingstrategytowardcomputationalthinkingfor non-majors:Designyoursolution. JournalofEducationalComputingResearch 49:437–59.[CrossRef] Lavalle,Ana,MiguelA.Teruel,AlejandroMaté,andJuanTrujillo.2025.Studyofgenderperspectiveinstemdegreesandits relationshipwithvideogames. EntertainmentComputing 52:100889.[CrossRef] Lunnemann,Per,MogensH.Jensen,andLiselotteJauffred.2019.GenderbiasinNobelprizes. PalgraveCommunications 5:46. [CrossRef]

Lusa,Amaia,MartaPeña,andElisabetMasdelesValls.2024.Includinggenderdimensioninoperationsmanagementteaching. JournalofIndustrialEngineeringandManagement 17:373–84.[CrossRef]

Machado,MônicadaConsolação,andLucilaIshitani.2024.Recommendationsforgamestoattractwomentocomputingcourses. EntertainmentComputing 50:100633.[CrossRef]

Marco-Simó,JosepMaria,María-JesúsMarco-Galindo,ElenaPlanasHortal,andMaríaJoséGarcíaGarcía.2023.Alignmentofthe institutionalstrategywiththeteachingactionintheimplementationofthegenderperspective.designandimplementationinthe caseoftheUOC. IEEERevistaIberoamericanadeTecnologíasdelAprendizaje 18:374–83.[CrossRef] MateosSillero,Sara,andClaraGómezHernández.2019. LibroBlancodelasMujeresenelÁmbitoTecnológico. Madrid:Ministeriode Economía,ComercioyEmpresa.

Mbaidin,Almoutaz,SoniaRábade-Uberos,RosarioDominguez-Petit,AndrésVillaverde,MaríaEncarnaciónGónzalez-Rufino,Arno Formella,ManuelFernández-Delgado,andEvaCernadas.2021.STERapp:Semiautomaticsoftwareforstereologicalanalysis. applicationintheestimationoffishfecundity. Electronics 10:1432.[CrossRef] Merayo,Noemí,andAlbaAyuso.2023.Analysisofbarriers,supportsandgendergapinthechoiceofstemstudiesinsecondary education. InternationalJournalofTechnologyandDesignEducation 33:1471–98.[CrossRef][PubMed]

Meza-Mejia,MónicadelCarmen,MónicaAdrianaVillarreal-García,andClaudiaFabiolaOrtega-Barba.2023.Womenandleadership inhighereducation:Asystematicreview. SocialScience 12:555.[CrossRef]

MihuraLópez,Rocío,TeresaPiñeiroOtero,andAntonioSeoaneNolasco.2023.‘Nosoyunagamer’sexismo,misoginiaytoxicidad comomoduladoresdelaexperienciadelasmujeresvideojugadoras. InvestigacionesFeministas 14:215–27.[CrossRef]

Msambwa,MsafiriM.,KangwaDaniel,CaiLianyu,andAntonyFute.2024.Asystematicreviewofthefactorsaffectinggirls’ participationinscience,technology,engineering,andmathematicssubjects. ComputerApplicationsinEngineeringEducation 32: e22707.[CrossRef]

Oreskes,Naomi.2020.Racismandsexisminsciencehaven’tdisappeared. ScientificAmerican 323:81.[CrossRef]

Paderewski-Rodríguez,Patricia,MaríaIsabelGarcía-Arenas,RosaMaríaGil-Iranzo,CarinaS.González,EvaM.Ortigosa,andNatalia Padilla-Zea.2017.Initiativesandstrategiestoencouragewomenintoengineering. IEEERevistaIberoamericanadeTecnologiasdel Aprendizaje 12:106–14.[CrossRef]

Peña,Marta,NoeliaOlmedo-Torre,ElisabetMasdelesValls,andAmaiaLusa.2021.Introducingandevaluatingtheeffectiveinclusion ofgenderdimensioninstemhighereducation. Sustainability 13:4994.[CrossRef]

Pérez-Sánchez,Beatriz,andNoeliaSánchez-Maroño.2023.Gendersensitivecontentinmachinelearningsubjects.Paperpresentedat theXVIIInternationalTechnology,EducationandDevelopmentConference,Valencia,Spain,March6–8.pp.2382–90.[CrossRef] Prendes-Espinosa,M.,P.García-Tudela,andI.Solano-Fernández.2020.Genderequalityandictinthecontextofformaleducation:A systematicreview. Comunicar 63:9–20.[CrossRef]

QueraltJiménez,Argelia.2024.Desinformaciónporrazóndesexoyredessociales.Gendereddisinformationandsocialnetworks. InternationalJournalofConstitutionalLaw 21:1589–619.[CrossRef]

Regueira,Uxía,andAlmudenaAlonso-Ferreiro.2022.LacompetenciadigitaldelalumnadodeEducaciónPrimariadesdela perspectivadegénero:Conocimientos,actitudesyprácticas. EstudiosSobreEducación 42:57–77.[CrossRef]

Regueira,Uxía,AngelaGonzález,andAdrianaGewerc.2023.Tecnoloxíaeducativaconlentesvioletas:Unhaexperienciade ensino-aprendizaxenauniversidade.In Epistemoloxíasfeministasenacción:VIIIXornadaUniversitariaGalegaenXénero.Pontevedra: UniversidadedeVigo,pp.61–72.

Reverter,Sonia.2024.¿Porquéladesigualdadlaboralentremujeresyhombrespersisteenlasuniversidadesespañolas?[Whydoesthe inequalitybetweenwomenandmenpersistinSpanishuniversities?]. CuadernosdeRelacionesLaborales 42:269–86.[CrossRef]

Rodríguez-Jaume,MaríaJosé,andDianaGil-González.2024.InnovacióndeGéneroenlaDocenciaUniversitaria(GenderInnovation inUniversityTeaching). RevistaLatinoamericanadeEducaciónInclusiva 18:167–82.[CrossRef]

Rueda-Pascual,Silvia,MarianoPérez-Martínez,MiriamGil-Pascual,IgnacioPanach-Navarrete,andSergioCasas-Yrurzum.2021. Includinggenderperspectiveinacomputerengineeringdegree.PaperpresentedattheXIInternationalConferenceonVirtual Campus,Salamanca,Spain,September30–October1,pp.1–4.[CrossRef]

RUIGEU.2022.Laspolíticasdeigualdaduniversitarias:Diagnósticodelosgruposdetrabajo.In InformedelaReddeUnidadesde IgualdaddeGéneroparalaExcelenciaUniversitaria.ReddeUnidadesdeIgualdaddeGéneroparalaExcelenciaUniversitaria. Availableonline: https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/handle/11162/242904 (accessedon12June2025).

Samper-Gras,Teresa.2022.Aloimportante,yavanellos.unapropuestacontextualdesdelosnuevosmaterialismosparacomprender porquéhaytanpocasmujeresencienciastécnicas. CuestionesdeGénero:DelaIgualdadylaDiferencia 17:209–31.[CrossRef] Sandoval-Martin,Teresa,andEsterMartínez-Sanzo.2024.PerpetuationofGenderBiasinVisualRepresentationofProfessionsinthe GenerativeAIToolsDALL·EandBingImageCreator. SocialScience 13:250.[CrossRef]

Sánchez-Canut,Sònia,MireiaUsart-Rodríguez,BeatrizLores-Gómez,andSoniaMartínez-Requejo.2025.Brechadegéneroen lacompetenciadigitalprofesional:Construcciónyvalidacióninicialdeuninstrumentoparasumedición[Gendergapin professionaldigitalcompetence:Constructionandinitialvalidationofaninstrumentforitsmeasurement]. Feminismo/s 45: 139–72.[CrossRef]

Schiebinger,Londa.2021.Genderedinnovations:Integratingsex,gender,andintersectionalanalysisintoscience,health&medicine, engineering,andenvironment. Tapuya:LatinAmericanScience,TechnologyandSociety 4:1867420.[CrossRef]

SepúlvedaDurán,CarmenMª,AzaharaArévaloGalán,andCristinaMariaGarcíaFernández.2025.Pensamientocomputacional desenchufadoeneducaciónprimaria:Unapropuestaenelámbitosteamdesdeeldesarrollodelaexpresióncorporal. RETOS 67: 12–26.[CrossRef]

Shrestha,Sunny,andSanchariDas.2022.ExploringgenderbiasesinMLandAIacademicresearchthroughsystematicliterature review. FrontiersinArtificialIntelligence 5:976838.[CrossRef]

Shute,ValerieJ.,ChenSun,andJodiAsbell-Clarke.2017.Demystifyingcomputationalthinking. EducationalResearchReview 22:142–58. [CrossRef]

Simon,Vivian,NetaRabin,andHilaChalutz-BenGal.2023.UtilizingdatadrivenmethodstoidentifygenderbiasinLinkedInprofiles. InformationProcessingandManagement 60:103423.[CrossRef]

Taboada,Maite.2024.Reportedspeechandgenderinthenews:Whoisquoted,howaretheyquoted,andwhyitmatters. Discourse& Communication 19:93–113.[CrossRef]

Tomassini,Cecilia.2021.Gendergapsinscience:Systematicreviewofthemainexplanationsandresearchagenda. EducationinThe KnowledgeSociety 22:25437[CrossRef]

Tortajada,Iolanda,andTeresaVera.2021.Presentacióndelmonográfico:Feminismo,misoginiayredessociales. Investigaciones Feministas 12:1–4.[CrossRef]

UN.2015.UnitedNations:TransformingOurWorld:The2030AgendaforSustainableDevelopment.Availableonline: https://www. un.org/en/deve-lopment/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessedon 12June2025).

UNESCO.2023.HarnessingtheEraofArtificialIntelligenceinHigherEducation:APrimerforHigherEducationStakeholders. Availableonline: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386670 (accessedon12June2025).

UNESCO.2024a.ChallengingSystematicPrejudices:AnInvestigationintoGenderBiasinLargeLanguageModels.Technical Report.InternationalResearchCenterofArtificialIntelligence(IRCAI).Availableonline: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark: /48223/pf0000388971 (accessedon12June2025).

UNESCO.2024b.ChangingtheEquation:SecuringSTEMFuturesforWomen.Availableonline: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark: /48223/pf0000391384 (accessedon12June2025).

UnidadMujeresyCiencia.2025.CientíficasenCifras2025.Availableonline: https://www.ciencia.gob.es/Secc-Servicios/Igualdad/ CientificasCifras.html (accessedon12June2025).

Valdeolivas,M.Gracia,M.ÁngelesLLopis,FrancescEsteve,andVirginiaViñoles.2022.Larobóticaeducativaconperspectivade género:Unainvestigacióncolaborativauniversidad-escuela.In Edutec2022Palma-XXVCongresoInternacional PalmadeMallorca: EDUTEC,pp.2018–20.

Veliz,Carissa.2021. PrivacyisPower:WhyandHowYouShouldTakeBackControlofYourData.London:TransworldPublishersLTD. Vicente,Lucia,andHelenaMatute.2023.Humansinheritartificialintelligencebiases. ScientificReports 13:15737.[CrossRef] Wing,JeannetteM.2006.Computationalthinking. CommunicationsoftheACM 49:33–35.[CrossRef] WorldEconomicForum.2022.GlobalGenderGapReport.Availableonline: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gendergap-report-2022 (accessedon12June2025).

Wu,Yankun,YutaNakashima,andNoaGarcia.2025.Revealinggenderbiasfromprompttoimageinstablediffusion. Journalof Imaging 11:35.[CrossRef]

Zack,Travis,EricLehman,MiracSuzgun,JorgeA.Rodriguez,LeoAnthonyCeli,JudyGichoya,DanJurafsky,PeterSzolovits,DavidW. Bates,Raja-ElieE.Abdulnour,andetal.2024.AssessingthepotentialofGPT-4toperpetuateracialandgenderbiasesinhealth care:Amodelevaluationstudy. TheLancetDigitalHealth 6:e12–e22.[CrossRef] Zuboff,Shoshana.2019. TheAgeofSurveillanceCapitalism:TheFightforaHumanFutureattheNewFrontierofPower.London: ProfileBooks.

Disclaimer/Publisher’sNote: Thestatements,opinionsanddatacontainedinallpublicationsaresolelythoseoftheindividual author(s)andcontributor(s)andnotofMDPIand/ortheeditor(s).MDPIand/ortheeditor(s)disclaimresponsibilityforanyinjuryto peopleorpropertyresultingfromanyideas,methods,instructionsorproductsreferredtointhecontent.