Students explore the latest research in the School of Applied Sciences

SCIENCE MATTERS

Do solar panels disrupt bats’ behaviour? Safeguarding UK rivers

C OULD FRANKENSTEIN

ENCOURAGE MORE DIVERSE

DISCUSSIONS IN SCHOOLS?

Meet the writing team

The student writers whose articles are featured in this issue

Alex Agace MSc in Science Communication

Ell Barron Msc in Science Communication

Ajay Bater MSc in Science Communication

Giorgio Graffino MSc in Science Communication

Evie Gardner MSc in Science Communication

Tanith Robbins MSc in Science Communication

Sarah Adams MSc in Science Communication

Camila Orozco Arbelaez MSc in Science Communication

Sarah Hanney MSc in Science Communication

Joseph Yeadon MSc in Science Communication

Anya Brentnall MSc In Science Communication

Science Matters issue 19 School of Applied Sciences

Safeguarding UK & European rivers

UWE PROFESSORS LEVERAGE AI AND DIGITAL MODELLING TO MONITOR AND MITIGATE POLLUTION

BY: ALEX AGACE

r Darren Reynolds and his team at UWE Bristol copilot two groundbreaking initiatives, utilizing artificial intelligence and advanced sensor technology to detect and prevent river pollution in the UK and across European waters. With UK rivers facing significant ecological threats, Dr Darren Reynold’s team has secured funding for UK and European projects to develop innovative technologies and approaches for monitoring river health, improving water management and

Dmitigating hydroclimatic extreme events.

Funded by UKRI (NERC) and Defra, The UK project collaborated with Chelsea Technologies and the Rivers Trust to develop the advanced sensors. These sensors, forming a cutting-edge sensing network, utilize the optical property of fluorescence to detect sewage pollution and monitor river health. The UK project will deploy the sensors in the southwest, in and around the Tamar catchment, a river basin running along the border between Devon and Cornwall.

Meanwhile, the European project TWIN-Waters unites researchers from Sweden, Poland and UWE in AI, sensor science, microbiology, and environmental sciences to develop smarter digital tools for better water management. As part of the project, TWIN-Waters are creating a digital ‘twin’ of their research areas, reconstructing the space digitally to collate their data and helping with planning and decision-making. Dr. Reynolds emphasizes the importance of freshwater systems for planetary health: “One in ten species of invertebrates…rely on rivers and freshwater systems,” he explains, yet they have suffered a severe biodiversity collapse, “more than any other ecosystem.” He adds, “What we really need is to develop more technology that can help us assess and understand, over long periods... aspects of river health” explains Dr

“the challenge is... how do you go about ground-truthing the decisions that emanate from that AI approach?”

Dr Darren Reynolds

Reynolds.

Freshwater systems play a vital role in Earth’s carbon cycle, transporting as much carbon as is buried in the ocean floor. Dr Reynolds describes them as the “broadband of carbon,” connecting terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Despite this importance, he highlights a critical “knowledge gap” in understanding river health, asking, “What does it mean to be ecologically healthy, and how do we measure that?”

At one end of the research, parameters like pH and conductivity are tested, while at the other end,

indicators like fish, invertebrates and birds are measured. However, Dr Reynolds points out that the vast “microbial communities” - essential in shuffling matter, metabolites, and energy –remain largely understudied. Understanding these microbial communities is key to understanding the whole freshwater system. Advanced technologies like AI and machine learning offer immense potential for modelling and understanding our freshwater systems, revealing the factors influencing river health. However, with great

technological power comes great responsibility, “the challenge is…how do you go about ground-truthing the decisions that emanate from that AI approach?” Reynolds asks. “How do you make sure that... it’s not biased in some way or another?”

Dr Reynolds highlights the challenges of training AI systems, noting that biased or low-quality data can lead to skewed outcomes. Moderating and validating these systems will be one of the biggest hurdles in grounding this research.

‘As much as it’s very exciting, on one side, it’s also quite challenging,’ he explains.

New bowel cancer drug reaches clinical trials

MORE EFFECTIVE TREATMENT OFFERS HOPE FOR BOWEL CANCER PATIENTS

BY: ELL BARRON

Anew drug, developed for bowel cancer patients who have not responded to available treatments, has reached clinical trials.

Bowel cancer is the fourth most common type of cancer in the UK, with 120 people developing it every day.

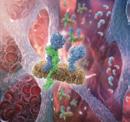

The drug targets a cell signalling pathway that behaves abnormally during cancer. Research taking place at UWE has linked specific proteins to the pathway. If a cancer tumour shows an abundance of these proteins, this indicates that the pathway is overactive, and the drug will work effectively.

There is a drug that targets this pathway already on the market. This new research aims to understand more about the pathway in order to create a more effective drug.

In our bodies, we have a compound called prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). When PGE2 binds to a receptor named EP4, a series of effects are triggered through a cell signalling pathway. One such effect is inflammation, an

important process that helps our bodies to cope with injuries and illnesses. This is healthy and normal.

However, during cancer too much PGE2 is produced. Additionally, bowel cancer tumours have large quantities of EP4 receptors. The result is an overactive pathway leading to excessive inflammation. This environment encourages cancer growth.

The drug works to prevent this by binding to EP4. In doing so, it blocks PGE2 and prevents the inflammatory environment that supports cancer growth.

UWE PhD researcher Laura Perry is working as part of the Greenhough Lab, led by Dr Alexander Greenhough, alongside the University of Bristol and pharmaceutical company Nxera. Before embarking on her PhD, Laura completed a Healthcare Science degree, and an MRes in Applied Sciences. She says: “The idea [is] that it stops the cells being quite so cancerous.”

For Laura, days in the laboratory are busy. First, she must grow cancer

cells. In petri dishes she grows cancer tumours and precursors to cancer tumours: adenocarcinomas and adenomas. She also grows 3D tumours called organoids. These more closely represent what we have in our bodies, so are helpful to show her how the drug will behave in a patient’s body. She then adds a measured dose of the drug and carefully monitors the changes in the cancer cells. One way to do this is by through advanced live imaging over time, using an IncuCyte machine, to see how their growth rate or morphology changes. Another way is to look at the gene expression of the tumours using qPCR, which gives information about the activity of the cell signalling pathways. She also analyses the proteins, identifying them using a technique called western blotting.

Nxera, partnered with Cancer Research UK, are conducting the clinical trials with patients with no response to prior therapies. Results will be published at the end of the trial.

New cancer fighting drug being developed at UWE

ONE IN TWO PEOPLE WILL DEVELOP A TYPE OF CANCER THROUGHOUT THEIR LIFETIME

BY: SARAH HANNEY

orking in collaboration with a pharmaceutical company, Wallscourt Associate Professor Greenhough is characterising a new drug that could be used for multiple tumour types, especially ones that have an inflammatory component.

Inflammation is part of the body’s tissue response to injury or illness and often occurs alongside cancer. When inflammation is present with cancer, certain cell signalling pathways are activated. These changes affect cancer cell growth and how the immune system interacts with the cancer.

Signalling pathways are chemical reactions that allow our cells to communicate and function and the cancer effectively disrupts the body’s ability to respond appropriately to them. In effect it allows the cancer to disguise itself from the body’s defences.

The drug would create a new way to target the prostaglandin signalling pathways which are highly expressed in cancers.

The hope is that it could be used on appropriate patients and could be combined with traditional cancer treatment methods such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Greenhough’s research is focused on understanding the cell biology using an in vitro model. Using cell samples within the lab, Greenhough tests the drugs and monitors the genes and proteins utilizing multiple techniques for analysing cells. These include next generation sequencing, a technique that gives researchers the ability to read DNA, so they are able

to study the gene expression of all of the genes in the cells; proteomics to look at all the proteins in the cells; and the metabolism to see what happens to the cells metabolism when the drug is introduced.

This is all done to help understand what the drug is doing to the cells. “If the drug is working on a patient that means we can understand a bit more about how it’s working and that allows us to then potentially select patients based on the characteristics of their tumour,” explains Professor Greenhough. Currently a clinical study is being conducted by the pharmaceutical company alongside detailed in vitro experiments using animal models. Ultimately, they are hoping to be able to gain funding for a large randomised clinical trial.

This is just one piece of research being conducted as part of the Wallscourt Long-term health conditions programme.

New funding might break new ground in ecoacoustics

EMERGING FIELD IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE MAY LEAD TO NEW WAYS OF UNDERSTANDING ECOSYSTEMS

BY: AJAY BATER

Once the realm of artistic exploration, the use of underground audio recording devices may be the key to providing new insights into the environment.

Ecoacoustics is an emerging field in environmental science, based around the study of sound found within different environments. Researchers believe the analysis of

these audio recordings, or soundscapes, may lead to new ways of understanding our ecosystems. Soil acoustics, while being a more complex area of ecoacoustics, is believed to offer a similar range of benefits. These include possible methods of monitoring the health of the soil and organisms hidden below. The sounds heard in soil come from three main sources:

human constructions such as vehicles, physical processes such as flowing water and organisms such as insects. One of the greatest challenges scientists are faced with is identifying where each sound comes from and what is making it. This is largely because soil is composed of differing mixtures of liquid, air and earth; all of which carry sound at different speeds. Dr. Sam Bonnet, a senior lecturer at the University of the West of England, intends to address such challenges through a grant from the UK Acoustics Network. His goal is to purchase audio recording devices and install them on Frenchay campus. “It might result in us developing an app or a means that a farmer or a landowner could measure the acoustics in their soil,” said the biogeochemist. “In conjunction with other approaches, like sensors for carbon and other technology.”

When asked for the motivation

“Soil is important, one of the most important factors of any civilization.”

Dr. Sam Bonnett

behind the research, Dr. Bonnet emphasised the importance of soil for humans and the climate. Soil in fact contains four times the amount of carbon found in plants and animals. It is one of the world’s

largest carbon stores, second only to the oceans. Dr. Bonnet said: “Soil is important, one of the most important factors of any civilization.” Due to overfarming and climate change, we are rapidly eroding

soil, reducing its fertility and releasing its stored carbon. He added: “We’ve lost 25% of organic matter in soils to the atmosphere since the advent of agriculture.”

Listening to soil is not new and artists have used soil and plant recordings in art and music since the 1960s.

Initially skeptical, Dr. Bonnet was inspired by researchers like Marcus Maeder doing practical research in the area. Dr Bonnet now emphasises the link between science and art in ecoacoustics, saying, “The science is one aspect, which I think is 50% of it. But I do think that the other 50% is the artistic side.”

Forensic DNA techniques offer new hope in early cancer detection

CANCER

BY: GIORGIO GRAFFINO SCIENTISTS

REPURPOSE DNA MARKERS TO DETECT EARLY SIGNS OF

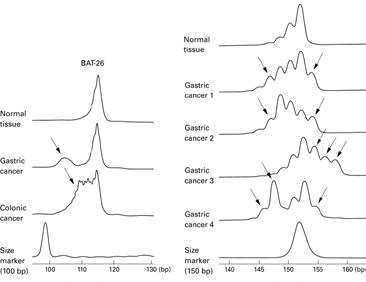

Scientists are repurposing DNA markers typically used in forensic investigations to detect early signs of cancer, potentially catching the disease before it takes hold. This innovative research is led by Prof. Ruth Morse, associate professor of human genetics at the University of West England in Bristol. She is an expert in genetic toxicology: “I study how the DNA gets damaged, how it gets mutated, how that can lead to inherited disease, and how it can lead to cancer.” When a cell becomes precancerous, its DNA replication process starts going awry, missing and repeating whole chunks of DNA in the patient’s genome. These structures are called STR (short tandem repeat), and they are common in everyone’s DNA. The combination of different repeats is unique to any individual; this is why they are

used in forensic science. “The chances that two people will have the same repeat is highly unlikely,” Morse said. STRs are useful as DNA markers for cancer detection too. They can be picked up using laboratory techniques based on PCR, the same used to detect COVID-19 during the pandemic, although these techniques are more complex and expensive. “We have some really good tests for measuring DNA damage and mutation.

What we don’t have is good methods of working out when the cell is [...] close to tipping into cancer,” Morse explained. The properties of STRs provided Morse with a perfect opportunity to use them for monitoring the outcome of stem cell transplantation in patients. For example, if a patient has leukemia and is not responding to treatments, one possibility is to transplant stem cells taken from a donor into the patient’s bone marrow. The bone marrow is a soft tissue contained in our bones, and responsible for producing our blood cells. After clearing the patient’s bone marrow from cancerous cells with chemotherapy, the donor’s stem cells are used to repopulate the patient’s bone marrow and make new blood cells. The STRs can then be used to tell apart the patient’s cells from the donor’s cells. This is important because

High

“Using these markers, you can actually see that [it] is not the patient’s leukemia coming back; it’s actually a new leukemia...”

sometimes a patient can develop leukemia again after the transplant. “Using these markers, you can actually see that [it] is not the patient’s leukemia coming back; it’s actually a new leukemia that’s forming in the donated cells,” Morse explained. The UWE Bristol team used human bone marrow cells to investigate the issue. The UWE Bristol

team used human bone marrow cells to study how IL-6 proteins, triggered by chemotherapy, can cause DNA mutations and lead to leukemia relapse. Their Translational Oncology paper highlights how STR tests can monitor patient health. Professor Morse and student Proma “Jess” Barua are now working with the NHS to make these tests more affordable and efficient. SM

Changing animal encounters in UK zoos

CALLS FOR CLEARER TERMINOLOGY FOR ANIMAL ‘MEET AND GREET’ EXPERIENCES

BY: JOSEPH YEADON

new study calls for UK zoos to establish clearer terminology surrounding animal-visitor interactions, emphasising the ethical importance of transparency and honoring animal autonomy.

AResearchers from UWE in partnership with Hartpury University have coined the term ‘Meet & Greet’ in a recent study, attempting to clarify language encompassing animal-visitor experiences in UK zoos. PhD candidate, and study lead, Polly Doodson revealed the 66% of zoos in the UK offer experiences that could be defined as a ‘Meet & Greet’. The research explores how the preexisting terminology can leave visitors uncertain about what to expect, “Zoos tend to use vague terms

like ‘encounters’ or ‘animal experiences’, which don’t explain what the visitor should expect”, Doodson explains. The researchers outline that ‘Meet & Greets’ differ from ’keeper for the day experiences’ and rather involves the opportunity to ‘meet’, ‘encounter’, or ‘experience’ the animal. The study raises the ethical implications of these interactions. The researchers argue that ‘Meet & Greets’ should prioritise the animals’ welfare by acknowledging their autonomy in choosing to engage with visitors. Although for many of us, zoos are a form of entertainment, Doodson explains “I think zoos need to lean into being conservation organisations, maybe play into less into a tourist attraction and build public support by showing they are legitimate conservation research organisations”. Doodson emphasises that ‘Meet & Greets’ are handsoff experiences, allowing the animal to initiate the interaction. However, this approach sometimes contrasts with the visitor’s expectations. Whilst working at Bristol

Zoo, Doodson led ‘Meet & Greet’ sessions and noted that some visitors arrived with preconceived notions about the level of interaction they would experience. “You’d get people who would say I did a lemur experience at another place, and we had them jumping on us and our shoulders”, she recalls. This highlights how inconsistent and vague terminology can lead to unrealistic expectations. While zoos aim to prioritize animal welfare and respect autonomy, unclear language can hinder efforts to promote ethical engagement. There are misconceptions surrounding the ethicality of zoos. Doodson notes that many zoo critics may well share values with ethical zoos. Since zoos are public attractions, clearer communication can help align public perception with conservation goals.

Wildlife filmmaking shifts focus to tackle environmental crisis

BY: EVIE GARDNER

he landscape of natural history television is rapidly shifting, from its purpose in light entertainment, to a more serious and urgent agenda.

TPhD student Jelena Krivosic is exploring how wildlife documentaries can better inspire audiences to act on the climate crisis.“What I’m hoping to do is to create a workshop, a cocreative workshop, where I bring filmmakers in together with audience members and we can together experiment with telling alternative stories about the natural world.”

Initial research findings suggest that raising awareness of environmental issues is no longer considered enough. “We need something else to push us a

tiny bit, push us over the edge, but we’ve got the awareness. What else do we need to progress beyond that to actively participate, actively engage?” said Krivosic.

Natural history documentaries have historically aimed to increase awareness and love for the natural world. Krivosic said: “I am looking at that message and seeing how effective it is, but also seeing how that may have held people back from actually openly talking about climate.”

“You get told one thing by the TV programme, you turn the TV channel, you go to the loo, you make yourself a cup of tea and you’ve already forgotten, so how do you make this constant?”

Krivosic said, highlighting the challenge that filmmakers face. Krivosic suggests that the most effective model will involve projects that are part-funded by non-governmental organisations (NGOs), which have local campaigns running alongside the film for people to get involved in: “It’s not just the shows themselves, it’s the marketing around it.”

A successful example of this model is Netflix’s ‘Our Planet’, which was part-funded by WWF, and provided viewers with simple ways to take action in their local environment. Krivosic noted the vast reach of documentaries and the potential impact if even a small fraction of viewers got involved.

Natural history documentaries have made progress in addressing environmental issues, once avoided for fear of losing viewers. “Conservation or climate was thought of as the C word” Krivosic said.

Moving from awareness to engagement will shift the landscape even further. Krivosic’s research at the ongoing, but will undoubtedly make waves in the industry.

Could Frankenstein encourage more diverse discussions in schools?

A NEW INTERACTIVE THEATRE EXPERIENCE AT UWE BRISTOL WILL ALLOW STUDENTS TO BUILD COLLABORATIVE COMMUNICATION SKILLS… AND THEIR OWN HUMAN BEING!

BY: SARAH ADAMS

2

018 marked the 200th anniversary of Mary Shelley’s literary classic, Frankenstein, but also the beginning of a unique idea for Dr Kathy Fawcett: to explore whether challenging cultural and political conversations might be easier in fictionalised settings.

Fawcett, a senior lecturer at the University, is working in collaboration with puppeteers to stage four live shows aimed at first year undergraduate students. Participants will be asked to create a figure using a variety of life-sized body parts,

which will then be ‘animated’ by the actors on stage.

Kathy aims to observe how participants communicate and collaborate as they build their humans, to better understand how people reach decisions in this fictional environment.

“I’m not looking for any particular point of view” she explains, “the goal will be for students to reach a consensus on what they want this new person to look like, and why”.

The students will also be asked to complete questionnaires and a creative writing task, providing further insight into each individual’s feelings and experience, and whether they perceive a connection to more contemporary contexts.

The project, entitled Body Lab, is scheduled to take place in September 2025 at UWE Bristol with the hope of being extended further afield. “My dream is to take it out to schools or do a residency at a science centre” says Kathy.

The field of science is bursting with exciting ideas and opportunities, but many prompt divided opinion, particularly

when it comes to passing these ideas onto the next generation. “Many conversations in schools are polarized within a debate-like format” Dr Fawcett explained, “people just harden their position rather than reaching any mutual understanding”.

Theatre in education began in 1953 with London’s Theatre Centre, promoting child-focused performances in schools. Since then, companies worldwide have tackled themes like climate change and science. Fawcett hopes her project will follow this tradition, using a familiar and engaging provocation to spark creative conversations on tough topics.

Interested in participating? Contact Kathy on Kathy.fawcett@uwe.a.c.uk

Bats’ attraction to solar panels poses a new conservation challenge

RESEARCH SUGGESTS SOLAR PANELS COULD DISRUPT BATS NOCTURNAL BEHAVIOURS

BY: ANYA BRENTNALL

magine walking into a glass door because you mistook it for an open space. For bats, flying around solar panels at night might feel much the same.

At first glance, solar panels seem like a clear win for the environment, capturing the sun’s rays to power our world and supporting the UK’s transition to renewable energy. Yet, there is concern that the surface texture of solar panels could disrupt bats’ nocturnal behaviours, potentially putting them at risk.

Bats provide important ecological benefits like eating crop-damaging insects, and even provide natural fertilizer

with their droppings, known as guano. However, solar panels might be indirectly impacting bats’ ability to feed and increasing their risk of collision. Research conducted at the University of the West of England (UWE) suggest that the angle of solar panels and their surface texture might be key factors contributing to these collisions.

This issue led Maya Griffin, a PhD researcher at UWE, to investigate the relationship between solar panels and bats further. Griffin’s research, conducted between July and September 2024, involved 24 solar panels arranged in elevated rows across 10 sites in the Southwest of England and mimics the layout and spacing used on commercial solar farms. Griffin’s results suggest that solar panels may confuse bats, potentially causing collisions that could impact their health and population numbers. Bats rely on echolocation to navigate and hunt in the dark. Griffin says, “if they [the bats]

are approaching at an angle, and it is [the solar panel] smooth, the soundwaves will not feed back to them, increasing their collision risk”.

Griffin’s research aims to balance solar energy demands with conservation goals as the UK strives to reach Net Zero targets. “We want to meet the needs of both the energy industry and wildlife without sacrificing [either one]” Griffin says. “Ideally, solar panels could be sited in urban or brownfield areas – rooftops, car parks –rather than open fields where bats are more active.”

Supported by ecological consultancy RSK Biocensus, Griffin hopes her research will shape bat conservation strategies within three years, especially in Southwest England where solar farms are expanding. With little current data on solar impacts, she urges that bats receive equal consideration in planning. Her study calls for “batfriendly” solar farms through careful placement and design.

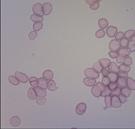

Customising red blood cells: New possibilities for Haematology

INNOVATIVE RESEARCH COULD TRANSFORM HAEMATOLOGY TREATMENTS

BY: TANITH ROBBINS

enior Biomedical

SScience Lecturer Dr Tim Satchwell is leading innovative research on customised lab-grown red blood cells, discovering new blood groups and creating techniques that could transform haematology treatments.

Red blood cells themselves cannot be genetically altered as they don’t contain DNA, Dr Satchwell explained. This means that to genetically modify a young red blood cell (a reticulocyte), you must modify the stem cell that will produce it. Dr Satchwell uses CRISPR gene editing to do just

that: manipulating the stem cells genes to alter the antigens (proteins) on the surfaces of the reticulocytes they produce. Knowing which proteins are exposed on the red blood cell surface and can be recognised by the immune system is key to transfusion medicine. Haemolytic Disease of the Foetus and Newborn (HDFN) affects around 500 pregnancies per year in England and Wales alone. This condition occurs during pregnancy when antigens on the surface of a babies’ red blood cell don’t match the mothers. This causes the mother’s immune system to react to the baby, producing antibodies which cross the placenta and attack the babies’ cells, potentially resulting in miscarriage. Identifying which antigens are involved allows for screening than can then make treatment possible. To investigate a HDFN case with an unknown cause, Dr Satchwell, collaborating with genetic sequencing experts at NHS Blood & Transplant, used CRISPR to remove cell surface proteins from lab grown reticulocytes to identify the cause of the immune response by eliminating the reaction with antibodies taken

from the mother’s blood. This work established a new blood group system (ER) and allows screening tools to be developed to predict and manage similar cases in the future.

This builds on previous work developed by Dr Satchwell for the removal of multiple blood groups from lab grown reticulocytes, he hopes this may eventually allow customised transfusions or at least improved compatibility for patients with rare blood groups or that require repeat transfusions. Lab-grown red blood cells won’t replace donations, but could help in specific cases. The ongoing RESTORE trial is testing their durability, with results due in a year. Scaling up production costeffectively remains a challenge, but the technology holds exciting, wide-reaching potential.

Pioneer research team creates paperbased device to detect blood clots

CUTTING EDGE DEVICE COULD REVOLUTIONISE ASSESSMENT OF BLOOD CLOTTING

BY: CAMILA OROZCO ARBELAEZ

Aresearch team at the University of the West of England is developing a cutting-edge device that could revolutionize how doctors assess blood clotting –and it uses the same simple science as lateral-flow COVID-19 tests.

Three different tests for three diagnostic devices are the research focus for Tony Killard and his team. “The basic principle of the devices is to determine whether there is a clotting problem, where is it located and how it can be treated” explains Killard. The paper strip in these devices is made from cellulose paper with wax melted into it. This device detects and measures specific substances in the body –in this case, blood–, by converting chemical information into an electric signal. These electrochemical sensors create channels within the paper strip for fluid to flow through them. It measures the distance travelled by a blood sample or the speed it travels at, depending on how well your blood clots.

Fibrinogen is a protein that

forms clots in the blood. If fibrinogen levels are low, blood takes longer to clot. In a realcase scenario with the device, the fibrinogen levels will determine how far the blood travels along the paper strip, based on how effectively your blood is clotting.

For the researchers, it is not only about creating a diagnostic device but allowing it to reach low- and middle-income countries and resource-limited environments. Although this technology has not yet been tested in a real-world setting given its early research stage, its potential to transform medical diagnostics is significant.

The 2023 Universal Health Coverage Global Monitoring Report from the WHO and World Bank reveals that half of the world’s population lacks access to essential health services.The lack of access to health services, including diagnostic aids is an ongoing concern that low-cost pointof-care devices may help solve in the future. With this new simple device, no piece of equipment, mobile phone,

or any technology would be required; all the information needed would be provided within the device.

The cost-effectiveness of these three devices, although still in process to prove their accuracy and performance in real-life scenarios, allows an affordable diagnostic aid that could identify a blood-related problem and signpost to further treatment or attention. If you think about the 2 billion people worldwide who live in rural areas with no access to essential health services1, these devices will provide a more supportive care under some of these conditions and perhaps assure a more accessible health system to those who desperately need it.

UPCOMING EVENTS

BODY LAB

Frenchay Campus

September 2025 (see page 14)

CENTRE FOR BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH LUNCHTIME TALKS

Fridays at 2.15pm, unless otherwise stated, on Microsoft

Science Chatters is the podcast from the Science Communication Unit at UWE Bristol looking at research and news from around the university. tinyurl.com/5ak85rzn

EDITORIAL TEAM

Andrew Glester, Andy Ridgway and Jane Wooster

Students share their experiences since studying the MSc in Science Communication at UWE Bristol in this film tinyurl.com/mvr3v6dx