Students explore the latest research in the School of Applied Sciences

SCIENCE MATTERS

Can stem cells help us understand neurodegenerative diseases?

REOPENING DISUSED TUNNELS TO CONSERVE BATS

Meet the writing team

The student writers whose articles are featured in this issue

Adelaide Miles-Nilsen MSc in Science Communication

George Edwards MSc in Science Communication

Aleksandra

Peliushkevich MSc in Science Communication

Sophie Borek MSc in Science Communication

Lynn Gayford MSc in Science Communication

Jennifer Springer MSc in Science Communication

Colm B Buckley MSc in Science Communication

Aislinn Snook MSc in Science Communication

Rachel Jones PhD student

Magaret Sivapragasam MSc in Science Communication

Iseult Merlin PhD student

Sneha Uplekar MSc in Science Communication

Casey Spry MSc in Science Communication

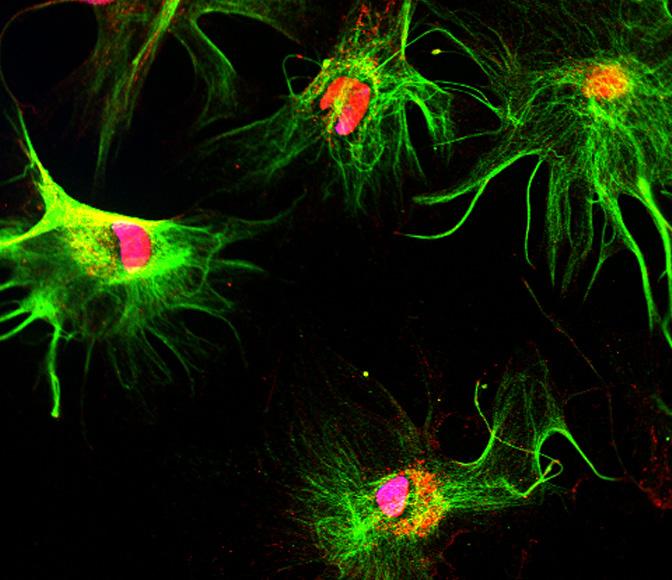

The inner workings of Parkinson’s Disease are being revealed

STEM CELL DERIVED BRAIN CELLS PROVIDE INSIGHT INTO NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES, HOW THEY WORK, AND POTENTIAL TREATMENTS

BY: ADELAIDE MILES-NILSENIn the world of neurodegenerative diseases, recent promising progress comes from the use of stem cells. Research into stem cells has shown that brain cells created from stem cells can have specific functions in the brain. By studying the fundamentals of neurodegenerative diseases, researchers have found that they can transplant stem cells

into the brain to alleviate symptoms of Parkinson’s. Stem cells are cells that are in their infancy and can be moulded into any type of cell within the body, so making brain cells out of stem cells can provide insight into the way that brain cells work, as well as being a potential way to create suitable replacements. One way to create stem cells uses an approach that can

make use of any cell in the human body, starting with skin cells, to create stem cells. This means that researchers can create stem cells from adults with a developed neurological condition to study and understand how their cells differ from the brain cells of adults without the conditions. Dr. Lucy Crompton is a lecturer at the University of the West of England and researcher in neuroscience, and one making strides in understanding diseases such as Parkinson’s. Her research is focused on the fundamental workings of neurodegenerative diseases. She is a researcher who uses this skin cell method to create stem cells to research neurodegenerative disease. Her recent research into the part of the brain that is central to Parkinson’s – the ventral mid-brain – shows that stem cell created brain cells, when

“... I think just to see something that is having clinical effect, it’s really inspiring.”

transplanted into the area, can make proteins unique to the area.

Knowing the difference between brain cells from a person with a neurodegenerative disease and brain cells from a person without is crucial for furthering neuroscientific research. Using skin cells from adults with

Dr

Dr Lucy Crompton

neurodegenerative diseases to create stem cells and comparing them to stem cells created the same way from an adult without the disease helps Dr. Crompton “understand why that person gets Parkinson’s disease”. Stem cell derived brain cells are being researched partially because they are capable of potentially replacing specific neurons that, when depleted, cause Parkinson’s disease. Other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, have a larger amount of brain cells affected, which make it much more difficult to find viable transplant options with stem cell derived brain cells. Research into the SM

fundamentals of any disease underpins the development of therapies, and Dr. Crompton’s research is no different. She explains that designing effective treatment relies on knowing how the disease functions, and when talking about current therapies in development, she stated: “For a long time, it’s been hard to predict when a breakthrough might come. And I think just to see something that is having clinical effect, it’s really inspiring.”

You can find out more about the research by Dr Lucy Crompton here https://uwerepository.worktribe.com/ output/10290823

Antimicrobial Aerosols

ANTIMICROBIAL AEROSOLS CAN COMBAT AIRBORNE COVID-19 VIRUSES IN INDOOR ENVIRONMENTS

BY: GEORGE EDWARDSDisinfectant aerosol sprays, used globally to reduce the number of ‘germs’ on surfaces, could now be modified and used to decrease the number of COVID viruses suspended in the air in closed rooms, new research suggests. This would drastically reduce the number of people getting infected by airborne viruses in enclosed spaces.

Darren Reynolds, a Professor in Health and Environment at UWE, and his team are developing a novel method to test the effectiveness of an antimicrobial spray containing hypochlorous acid on reducing the viral load (the number of individual viruses in a given space) of viruses such as COVID-19. And so far, the team are seeing successes. “We need new approaches to dealing with airborne

viruses,” Professor Reynolds said. He hopes such sprays will enhance solutions for suppressing airborne viruses “in case of another pandemic”. The aerosol would be sprayed into the air much like an air freshener, releasing chemical particles which bind onto the viruses and either destroy their outer membrane or genetic material. This suppresses the virus and makes it incapable of infecting a host (such as humans or animals) and then replicating within them.

Collaborating with UWE’s School of Engineering, the team designed a stainlesssteel drum to test their methods. The drum rotates to ensure viruses remain suspended in the air. For the antimicrobial, the team chose hypochlorous acid – a

chemical naturally produced in the human body and already used as a surface disinfectant in Japanese and American hospitals. This chemical successfully deactivates viruses and kills bacteria, but does not pose harm to humans. Due to difficulty using Sars-CoV-2 (the COVID virus) in experiments, as it easily infects researchers, the team used a different virus – phi6 – with similar properties. Despite phi6 being a bacteriophage (a virus that infects bacteria, not humans), it has some similarities with Sars-CoV-2 (the virus behind Covid-19). Both have a lipid membrane surrounding the nucleocapsid, where genetic material is stored, that antimicrobials can bind onto to deactivate the virus. With hypochlorous acid in aerosol form effectively reducing the viral load of phi6 within the drum, Professor Reynolds hopes this approach can be applied to Sars-CoV-2 and other airborne viruses in enclosed spaces.

“We need to be better prepared to be able to deal with the impacts that will inevitably come with another pandemic,” Professor Reynolds said.

SM

PHOTO CREDIT: ‘GERALT‘ PIXABAYElephants, Lions, Tigers, and Beetles?

PRESENTING THE ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL WORLD IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

BY: COLM B BUCKLEYResearch has been carried out at the University of the West of England (Bristol) into accurate, effective, and interesting ways of presenting the environment and natural world in children’s literature.

Dr Amanda Webber and Dr Verity Jones have used ‘Battle of the Beetles Book 1: Beetle Boy’ a children’s novel by M.G. Leonard. It has a winning combination of adventure and intriguing insect information alongside an underlying environmental theme.

They interviewed the author, conducted focus groups with year 5 and 6 children from two schools and interviewed their teachers.

Dr Webber said “She wrote it because she had a fear in childhood of insects, just hated insects. Then as an adult, when she had her child, she realised the phobia was passing on to her son and she was seeing him acting in the same way as she did. She was uncomfortable with that because he was picking it up

from her.”

The author addressed her phobia as an adult when she developed an interest in gardening and the insects living in her own garden. She became aware of her limited and inaccurate knowledge of insects which subsequently lead to her spending years informally studying insects prior to writing her first book alongside an expert in insects ensuring a detailed accuracy. The researchers found the focus groups predominantly enjoyed the book and had developed interests in insect diversity and behaviour. It led to some children continuing on with their independent study and reading about insects. It was also found that the children picked up on the books aim of trying to positively influence their interest and knowledge about insects. It was not possible to positively change the minds

of all of the children involved, unfortunately.

Dr Webber said ‘Beetle Boy’ interested her and Dr Jones because it is children’s fiction with factual content about insects verified by someone with expert knowledge. She is now seeing if it is possible to do a broader study into insect presence in children’s literature and which species appear as some are not represented.

Dr Webber works within the UWE Bristol’s Science Communication Unit. She is Programme Leader of the MSc Science Communication delivered at UWE Bristol. She is interested in researching how children’s literature represents wildlife.

SM

A mission to restore the coral reefs of Sri Lanka

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDENT PLACEMENT YEAR IN BONAVISTA

BY: SOFIE BOREKith a keen interest in marine life, UWE Environmental Science student Millie Bartaby, chose to focus her placement year on coral reef restoration in Bonavista, Sri Lanka. Finding that artificial reefs can be grown on concrete blocks on the seabed, Millie dived down to test a range of ways to attach coral fragments to the readily available blocks.

WCoral reefs are one of the

most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet, but face mounting threats in the form of climate change, destructive fishing, pollution and development. Creation of artificial reefs are one of the ways in which conservations are trying to tackle direct loss and damage to reefs. Millie’s study centred around testing a range of different attachment methods; epoxy putty (commonly used in plumbing), cable ties, and cement, to secure fragments of coral found on the seabed to blocks of cement to kickstart the colonization of a new artificial reef. Her research led her to find an efficient attachment method for planting coral fragments, but to get this result she faced a number of practical challenges.

Research budgets can often be tight and although Millie is a trained scuba diver, snorkelling and free diving save on the cost of equipment and boat hire. She also discovered that the whole process would need to be done

in-situ: i.e removing coral fragments from the sea was not permitted. This meant collecting coral, and fixing it to the blocks using the putty, all within one diving session. Whilst grappling with currents and working under one breath, she would also have to deal with hungry wildlife such as parrot fish which would feed off the algae on newly planted corals.

Newly planted corals could also become knocked off by adverse weather/currents, and tourists.

Sadly, although the epoxy putty proved a successful method for attaching corals, the reality of the method not being suitable long term in the area was disappointing for Millie. Without government funding, any restoration efforts are mainly carried out by small conservation NGOs, so methods are often limited to those with the lowest cost. Although it may appear counterintuitive to introduce more plastic to the ocean, it is used in a number of projects

“Although you may get plastic pollution from zip ties, they are cheap and accessible”

Millie Bartaby, Environmental Science student

globally.

“The putty might not be a great method in areas where they don’t have the finance and resource to ship it in. Although you may get plastic pollution from zip ties, they are cheap and accessible”. During the restoration work, the zip ties were removed from the sea once corals had self-attached to the cement. New biodegradable ties are beginning to become available, however, with studies beginning to test their use in coral restoration such as Reefscapes, a coral reef restoration consultancy. SM

Could tea help with our friendly bacteria?

IMPROVING SCIENTIFIC UNDERSTANDING OF THE EFFECTS OF HERBAL TEAS ON OUR MICROBIOTA

BY: LYNN GAYFORDOver 80% of the world’s population is estimated to use traditional herbal medicines. At UWE, Oluwadamilola Racheal Okeyoyin’s (Dami) PhD research is using herbal teas to improve scientific understanding of how herbs interact with the human body. Herbal medicine has a long history and many people, along with Dami’s family, still use traditional plant knowledge for their own health. “Things we consider weeds….they grow on the path, but because there is not a sign with how it contributes to human health, it is disregarded” says Dami, explaining how her mother would treat Dami for a fever or a cold with locally found herbs. The World Health Organisation’s (WHO) recent launch of the Global Centre for Traditional Medicine, and their first Traditional Medicine Summit in August 2023, emerged from requests from member states to gather evidence and data to inform policies, standards and regulation of traditional and complementary medicine. The Summit concluded with Dr Hans Kluge, WHO

Regional Director for Europe, stating “We have reiterated how crucial it is to get better evidence on the effectiveness, safety and quality of traditional and complementary medicine.”

Dami studied a BSc in Biomedical Science at UWE and, after two years in Nigeria, returned for an MRes focusing on cancer research. The two years working in Nigeria with a company making plantbased hair care products and reflecting on growing up in a family using medicinal herbs, inspired Dami to think about the science behind some of the widely-used herbal remedies. Dami’s PhD is researching the effects of herbal teas and supplements on the human microbiota and metabolism. She has been looking at the

interactions of herbs with several microbiotas - the oral, nasal, throat cavities and the gut. The lab-based work introduces pathogens and phytochemicals, the active parts of plants, and records the effects. The next stage will be clinical trials, including considering people’s diets and lifestyles, as well as practical issues such as the strength and temperature of the tea.

Dami does like to forage for herbs in her spare time but her research is all carried out with supermarket tea bags. The work is part-funded by Pukka Teas who have shared the details of components of their teas. This is to ensure the doses, plant varieties, drying conditions and storage are all consistent for the experiments; picking herbs in the wild would require taking a range of environmental conditions into account.

Dami hopes that teas could be used by healthcare professionals alongside pharmaceuticals, increasing accessibility and affordability. “I don’t want it to be on the side medicine, I want it to be adopted up front as well” says Dami.

Sustainable farming using a hybrid microbial fuel cell hydroponic system

HYBRID MI-HY SYSTEM SHOWS GREAT POTENTIAL

BY: JENNIFER SPRINGERydroponic farming systems, while valuable to urban farming, are not currently sustainable. They consume substantial energy for lighting, aeration and nonrenewably sourced fertilisers such as nitrogen and phosphate. Dr Neil Willey, a UWE-based researcher on the MicrobialHydroponics (Mi-Hy) EU project, hopes to introduce the next generation of hydroponic systems combined with microbial fuel cells to combat current sustainability issues. Hydroponic systems enable crops to be grown in water solutions in unconventional spaces – abandoned warehouses and underground train stations have been converted into thriving farms using these systems. This farming method has been vital in the advancement of urban farming,

Hallowing crops to be grown in unused spaces, without the need for sunlight or rain access. Previously, microbial fuel cells have been used to convert wastewater into electricity by using microbes to digest the inorganic waste compounds, converting the chemical energy from digestion into electrical energy. The Mi-Hy project aims to power hydroponic systems using electricity generated by these fuel cells, using the waste from the systems to supply the fuel cells. Dr Willey says it aims to “use the outputs from the fuel cell as the input to the hydroponics system to make it more sustainable”.

The hybrid Mi-Hy system shows great potential in tackling major issues with current hydroponic systems particularly in terms of energy usage and fertilizer sourcing. These systems could produce the inorganic fertilisers required for crop growth by filtering the run-off waste solution produced by microbial fuel cells, which contains useful nutrients which would otherwise be discarded. This

solution is often rich in nitrogen and phosphate, so this process could reduce dependence on mined rock phosphate and nonrenewable chemical processes whilst minimizing waste. Beyond sustainability, there is potential to use the microbes present in the fuel cells in these new systems to enhance the taste and quality of hydroponically grown foods. Dr Willey notes that foods commonly grown in hydroponics, such as tomatoes, peppers and cucumbers are often waterier and more tasteless than their traditionally grown counterparts. This is in part because of the lack of rhizosphere; the region of soil around plants containing nutrients and microbes which are beneficial to plant growth. Dr Neil Willey suggests that mimicking these conditions in hydroponic systems, creating a “prosthetic rhizosphere”, may alter the physiology of the crops, improving the flavour and texture of the produce.

The Mi-Hy project represents a significant step in modern agriculture, addressing key issues with traditional hydroponic systems’ sustainability.

Tracking resistance to antibiotics can help us fight the ‘silent pandemic’

URGENT NEED TO IMPROVE GLOBAL SURVEILLANCE SYSTEMS

BY: CASEY SPRYIf you become ill with a bacterial infection, there is a good chance that you will need to take antibiotics. However, overuse of antibiotics in human medicine has caused some bacteria to become resistant to treatment –scientists call this antimicrobial resistance (AMR). While this is not necessarily new information, some scientists have discovered there are flaws in the system we use to contain this problem. Obiageli Okolie, a PhD student

in the School of Applied Sciences at the University of the West of England, discovered the information we gather to control the spread of AMR is often inaccurate and unreliable. So, why is this such a problem? AMR is one of the top 10 global health threats. A lot of people rely on antibiotics to fight illnesses, and if these antibiotics do not work, it puts people’s lives at risk.

“It is a silent pandemic that is no longer silent; it is out there and is obviously a challenge,” Obiageli said. By correctly identifying the levels of resistant bacteria in human populations, and what species of bacteria are involved, we can control the problem and protect the people most at risk.

We must collect information on patients with resistant infections, and this is where surveillance systems come in. Some of this data includes their age, gender, and present hospital; if any information is missed, the system cannot correctly track the levels of resistant bacteria. This is exactly what Obiageli found when she

reviewed the current surveillance systems in Africa, where there is a particular struggle with AMR. Discovering there were gaps in these systems, such as missing the key data mentioned above, prompted her to focus on this issue in Nigeria for her PhD. Another problem with the system is that the resistant bacteria will only be picked up from patients who receive tertiary levels of care in hospital. Tertiary care is specialised care, often for people with serious illnesses. Obiageli explainsthis “doesn’t give us a real picture of the burden [level] of resistance in the community because the community is completely cut out,” meaning the system will not pick up resistant bacteria amongst patients who receive any other care in hospital. Obiageli’s findings show there is an urgent need to identify and fix these flaws, so, globally, we can effectively fight this serious threat to human health. Having global systems that accurately track resistance in real-time will allow scientists to control an issue that affects all of us.

European Competence Centre for Science Communication

NEW COALESCE PROJECT COULD BE KEY TO THE SUCCESS OF SCIENCE COMMUNICATION IN EUROPE

BY: AISLINN SNOOKSsocial media and other online platforms have enabled almost anyone to communicate science and push heavily politicised views to vast audiences. There is no clear formula for the most effective way to communicate science, something the new COALESCE project aims to address. This four-year project, running to March ’27, aims to set up a European Competence Centre for Science Communication. The Science Communication Unit (SCU) at the University of the West of England (UWE), is involved in the project, leading the communication of the Competence Centre’s activities and resources as well as being involved in other aspects of the project’s work. The competence centre will be an online resource and national ‘hubs’ will also be

located in different European countries.

Dr Achintya Rao, who works within the SCU and is COALESCE’s Science Communication and Engagement Manager, says the Competence Centre aims to consolidate knowledge from EU-funded science communication research projects that have taken place before. It will then provide resources for those communicating science research to help them be more effective, reaching new audiences that don’t typically engage with science for example. The Competence Centre aims to provide science communicators with innovative ways to address challenges such as misinformation and effective science communication during times of crisis.

COALESCE is aimed at helping a wide range of people including scientists, journalists, science centre staff or science bloggers, to enhance their science communication activities and reach new audiences.

UWE’s involvement in COALESCE is led by Dr Andy Ridgway, a Senior Lecturer in Science

Communication, and the project also involves Professor Clare Wilkinson and Professor Emma Weitkamp, Co-Directors of the SCU. The UWE team’s first major deliverable was the production of the communication and dissemination strategy, which provides a detailed plan for project’s communication activities over the next few years. Achintya describes science communication as “infinitely contextual’’. The Competence Centre will provide resources and guidance relevant to the unique challenges facing science communicators in different countries across Europe. For example, the Competence Centre’s national hubs will translate resources into national languages and adapt the resources so they are relevant to the challenges faced by people in their own countries.

Life beyond deadlines: Working at the NHS Blood and Transplant Service

A PLACEMENT YEAR CAN OFFER A HELPFUL GLIMPSE OF YOUR CAREER AFTER GRADUATION

BY: ISEULT MERLINs a student, life beyond exams and deadlines can be hard to imagine, and it’s easy to forget what you’re working towards. Biomedical science student Aaliyah Hytmiah

Awas able to experience the reality of working in her field by securing a placement year at the NHS Blood and Transplant Clinic in Filton, Bristol. The NHS Blood and Transplant

Service is responsible for managing donations of blood, stem cells, bone marrow, organs, and tissues, as well as ensuring donors are correctly matched to the patients that require lifesaving care.

Aaliyah’s motivation came partly from her own experience dealing with sickle cell anaemia, a disease that affects the shape and oxygen-carrying capabilities of red blood cells. Because of this, she hoped to work in the red cell immunohematology department, dealing with cases like her own. “I wanted to see how the blood and transfusion side of things worked in a clinical setting,” Aaliyah explained. However, Aaliyah was placed in the histocompatibility and immunogenetics department instead, performing tasks such as HLA typing – a critical process to match stem cell donors to patients. HLA stands for human leukocyte antigens, proteins on the surface of human cells that allow the immune system to

“I feel so much more confident in the lab...”

Aaliyah Hytmiah, Biomedical Science student

recognise the body’s own cells, while attacking foreign ones. Six main HLA markers are used to identify a good “match”, referring to the number of markers the patient and the donor have in common – the more, the better. Without a good match, the patient’s immune system may attack the donor’s cells, leading to dangerous complications.

This was a big change from the hypothetical case studies Aaliyah had done in class. “When you know it’s a real person and that the decisions you make

will actually affect someone, it’s completely different,” she said, “there’s a lot more at stake.”

Although the role was not patient-facing, this human connection was important to Aaliyah. She described how cancer patients returned for regular tests, leading to a strange, one-sided relationship where Aaliyah was rooting for their recovery. “You’d follow their journey and progression from behind the scenes. I don’t even know what they look like, and they don’t even know that I’m there.”

Aaliyah said she was grateful to relax after work without the pressure of deadlines and exams.

Although it wasn’t her first choice of department, Aaliyah expressed that the histocompatibility and immunogenetics had been the right place for her after all. Having finished her placement, she claims it made a huge impact on her learning. “I feel so much more confident in the lab,” she said, “and I understand things in lectures a lot better.” SM

Bespoke upskill programme for health care professionals

A COMPETENCY FRAMEWORK FOR GENOMICS CONCEPTS

BY: RACHEL JONESGenomics is becoming increasingly prevalent in our understanding of health and disease.

Genetic sequencing – where orders of genetic building blocks, known as nucleotides, are determined – is becoming more accessible, due to falling costs. Despite this improved availability, genetics is often considered specialist care, which does not have the financial or manpower resource to oversee the vast quantities of genetic testing which could soon become normal to order.

Genomic mainstreaming, where genetic testing would be as

easy to request as a standard blood test, will become normal, but this requires the improved understanding of some key healthcare professionals –including nurses and midwives – who receive minimal, if any genomics training. Existing options for developing genetic understanding for NHS staff include ‘just in time’ content, but some struggle to apply this knowledge. Instead, Professor Aniko Varadi – Director for Research for Bioscienceshas developed a bespoke course to improve understanding, confidence, and communication of genetics to patients. This began with a competency framework, assessing the base understanding of different genomics concepts, enabling participants to self-evaluate their competence. A taught course, recently welcoming its fourth cohort, is now offered. “I always say that genomics is very much like using an X-Ray or MRI scan, that it will change the healthcare but it’s not going to be a solution for everything. So, it has its own limitations” – Professor Varadi stated. Whilst testing has become more affordable, and databases for genetic links are updated

annually, research needs to accelerate at the same rate “it comes back with we are not sure; we don’t know the answer so there is an uncertainty”. However, things are always improving – “it has changed so much that I would expect that there will be more and more developments”. This course is bringing about positive change - “when we first developed the course no one heard of Lynch syndrome” - an inherited genetic variation increasing the chance of developing cancers like colorectal cancer. Now, the “pathways nationally are led by the nurses who we trained up”.

Healthcare professionals who attend the course leave with heightened confidence. Many start ranking themselves at a 2/5 (1 being no confidence) – “when they finished the course it was like a 4/5 so really had a huge impact”.

It will be a challenge to roll out nationally – “The size of the workforce is so big, and we only have fifty on the course” – “it will take over 100 years to upskill them” explains Professor Varadi. This project is proof that research completed at UWE has genuinely positive service impact on our healthcare services.

We can all do science

EQUALITY AND DIVERSITY IN STEM

BY: ALEKSANDRA PELIUSHKEVICHDr. Emmanuel Adukwu has recently been promoted to Professor for his administrative and teaching achievements, innovations in employability strategies, and his scientific work on addressing socially significant infectious diseases. Professor Adukwu not only excels in his research but also inspires students to pursue a career in science. “People who are struggling as they go through the science and are not sure what they want to do just need to keep going, and they will find success at the end,” he says.

Dr. Emmanuel Adukwu has dedicated 10 years to the UWE, progressing from Lecturer to Professor in Microbiology and Deputy Head of the School of Applied Sciences. Throughout his tenure, he has undertaken various roles, including Senior Lecturer, Employability Lead, and Widening Participation Lead. Professor Adukwu has developed innovative employability strategies incorporating digital tools such as Science Futures, an annual fair that provides an available online platform for presenting research and exploring career opportunities across diverse scientific fields. Under the professor’s guidance,

Science Futures has evolved from a modest event gathering 50-60 participants into a large employability fair, attracting hundreds of students. “The success of my students is the most important achievement for me,” says Professor Adukwu. He has supervised over 100 students, many of whom have become academics themselves. Talented students inspired him year after year.

Another priority for Professor Adukwu is equality and diversity in science. “Science is not exclusive. We all can do science,” he says. Professor Adukwu engages in civic activities on the boards and committees of leading organisations in Bristol, across the UK, and

internationally, advocating for the importance of diversity in STEM to the broader community. The professor highlights challenges in this domain, including the awarding gap, the gender pay gap, and the lack of diversity in senior leadership roles across UK education. Professor Adukwu aims to raise awareness about these challenges and encourage the community to participate as partners in finding solutions. Among his responsibilities, Professor Adukwu has led scientific research in antimicrobial stewardship, a multifaceted project aimed at diminishing infections causing socially significant diseases. This initiative includes the development of novel drugs targeting microorganisms resistant to existing antibiotics. To achieve the last goal, Professor Adukwu and his colleagues use alternative plant-based compounds - essential oils. The professor strongly believes that antimicrobial resistance remains a global problem, projected to be associated with 10 million deaths annually by 2050. “We need to look for all possible opportunities that we could use to manage, reduce, or tackle the infections caused by antimicrobial resistance,” says Professor Adukwu.

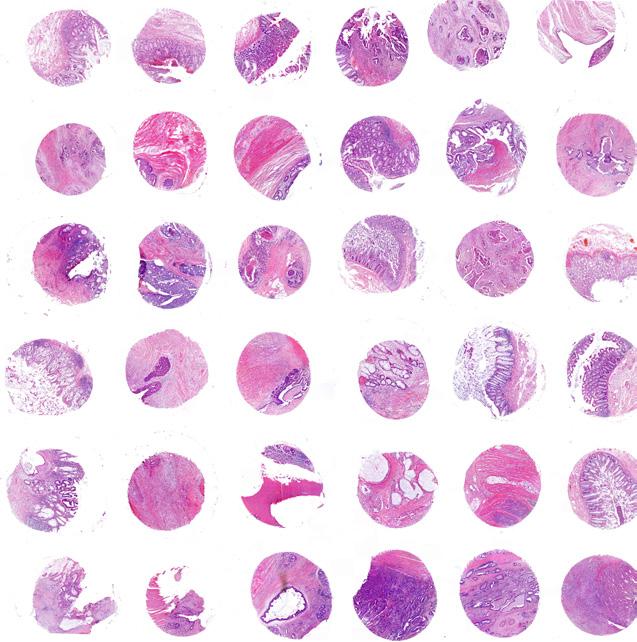

Could we be teaching an old drug new tricks?

ASPIRIN’S UNEXPECTED ROLE IN THE FIGHT AGAINST RECTAL CANCER

BY: MAGARET SIVAPRAGASAMThe untapped potential of this humble painkiller has sent ripples to the world of rectal cancer treatments with exciting possbilities. Combining Aspirin or Nonsteroidal AntiInflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) with chemoradiotherapy may reduce the aggressiveness of rectal cancer, according to studies led by Dr. Alexander Greenhough, a Researcher and Wallscourt Associate Professor of Health Diagnostics at the University of the West of England.

Individuals with rectal cancer are usually treated with a combination of traditional chemotherapy and radiotherapy before surgery and this reduces the chance of the cancer recurring. However, this treatment does not work well in up to 40% of patients, especially those under the age of 50. According to Dr. Greenhough, this, in turn, worsens their conditions because the treatment delays prospect of surgery which may result in a worsened condition. There is an urgent clinical need to look for diagnostic indicators (biomarkers) to predict which patients will best respond to

CRT, and to identify novel adjunct therapies that could be harnessed to improve responses to CRT. “It was a serendipitous find; it was just noted that people taking Aspirin or Aspirin-like drugs had a reduced risk of cancer,” says Dr. Greenhough. “But there’s a lot we don’t know,”

Curiosity then drove Dr. Greenhough and his team to find ways to discover treatments that could be used alongside CRT. The researcher has been trying to develop more specific drugs that would target the key bits of what Aspirin/ NSAIDs do especially for patients with poor response to CRT and delayed surgeries. The research team’s data suggested that the increasing activity of a chain of molecules (called G protein-coupled receptor- GPRC5A), conferred resistance to CRT in rectal cancer patients. The expression of GPRC5A acted as a biomarker of patient response and clinical outcome. Aspirin then acted as a preventive agent by targeting a process that produces a signal known as cyclooxygenase (COX)/

prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) pathway which is responsible for pain and inflammation. By discovering these biomarkers in patients, novel adjunct therapies can be harnessed to then optimize patient responses.

“There is potential to understand why certain patients respond better, and we may be able to predict, using biopsies and diagnostics, which treatments to give and when to improve patient outcomes” explained Dr. Greenhough adding, “A commonly used drug might be used to prevent or treat cancer, it’s fascinating that you could do this. Understanding more about how it works could lead to new therapy”

Reopening disused tunnels while protecting bats

STUDY AIMS TO DRAFT GUIDELINES FOR OPTIMAL LIGHTING STRATEGIES TO CONSERVE BATS

BY: SNEHA UPLEKARThe UK has around 650 disused tunnels, out of which 250 are in the South West of England. They could be opened for cyclists and walkers, but these abandoned spaces are also habitats for various species of bats. Could there be a way for the tunnels to be used by people, without disturbing the bats?

Chiara Scaramella is a PhD student investigating the impact of artificial lighting in tunnels on bat activity. One of the main objectives of the study is to draft guidelines for optimal lighting strategies to minimise the impact on bats while reopening disused tunnels. Bats play a vital role in the natural environment, providing various ecosystem services like pest control and pollination which are

important for food production. They are also good bioindicators - this means that the presence of bats points to the good health of that ecosystem.

Light pollution is one of the biggest threats facing bats, and there are many studies that focus on the impact of artificial lighting on bat activity. This study examines the ecological relationship between bats and tunnels, and the impact of artificial lighting in these niche spaces.

“There are many organisations that want to reopen tunnels in the UK. We want to find optimum levels of brightness and colour temperature so people can use the tunnels while also preserving bat colonies” said Chiara.

Chiara’s study began in January 2023 and is a collaboration between UWE and the University of Bath, with field sites spread across the South West.

The research is divided into two phases, phase one is focused on the ecology of bats that use the tunnels. This includes understanding the level and the nature of bat activity as it varies throughout the year. For example, bats are very active during summer months but hibernate in

their roosts during the winter. The second phase is to test the effects of artificial lighting in the tunnels on bats. This will involve testing the impact of various configurations, colour temperatures and levels of brightness on bat activity. Chiara’s interest and passion for bats is longstanding, her master’s thesis looked at bat activity in organic versus conventional agriculture in mediterranean farmland.

“Bats provide many ecosystem services and are very important for the environment. I do ecology, so for me, there is an intrinsic value in conservation. But it is really important to highlight the value of bats because that’s what policymakers are interested in. That’s one reason why research like this needs to happen” said Chiara.

Get involved…

UPCOMING EVENTS

CRIB SEMINAR SERIES

Organised by Lucy Crompton and Kevin Honeychurch, the The Centre for Research in Biosciences’s seminar series continues in 2024.

Fridays at 12.15pm, unless otherwise stated, on Microsoft Teams.

SCIENCE MATTERS

EDITORIAL TEAM

Andrew Glester, Andy Ridgway and Jane Wooster

All the articles are written by students at the University of the West of England

Science Chatters is the podcast from the Science Communication Unit at UWE Bristol looking at research and news from around the university. tinyurl.com/5ak85rzn

Emma Brisdion shares her experiences since studying the MSc in Science Communication at UWE Bristol in this film

https://tinyurl.com/3x5m7cwa