THE UNIVERSAL LANGUAGE

Exploring Love as Young Adults

4-5 | Letter from the Editor + Creative Directors

8 | Eve Without Adam

Andrea Arcia

Andrea Arcia picks the fruits of pain, nostalgia and healing after her first relationship ends.

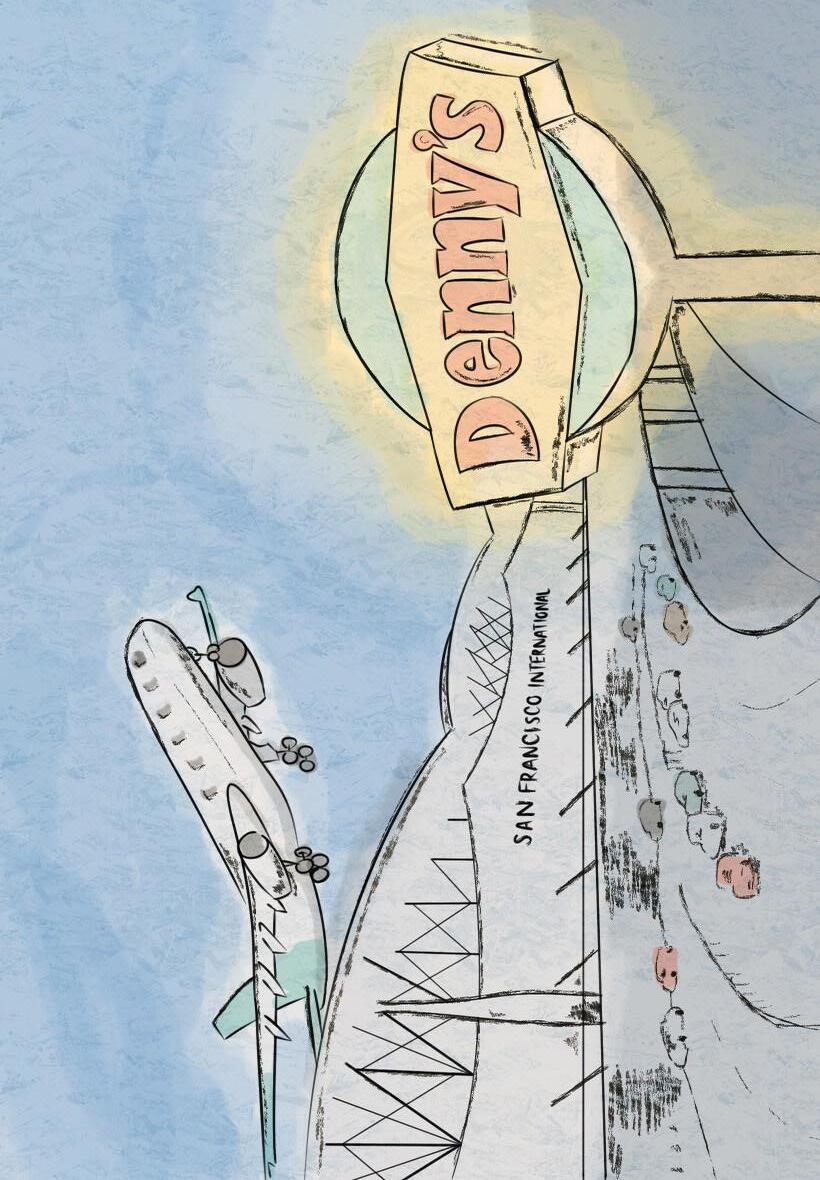

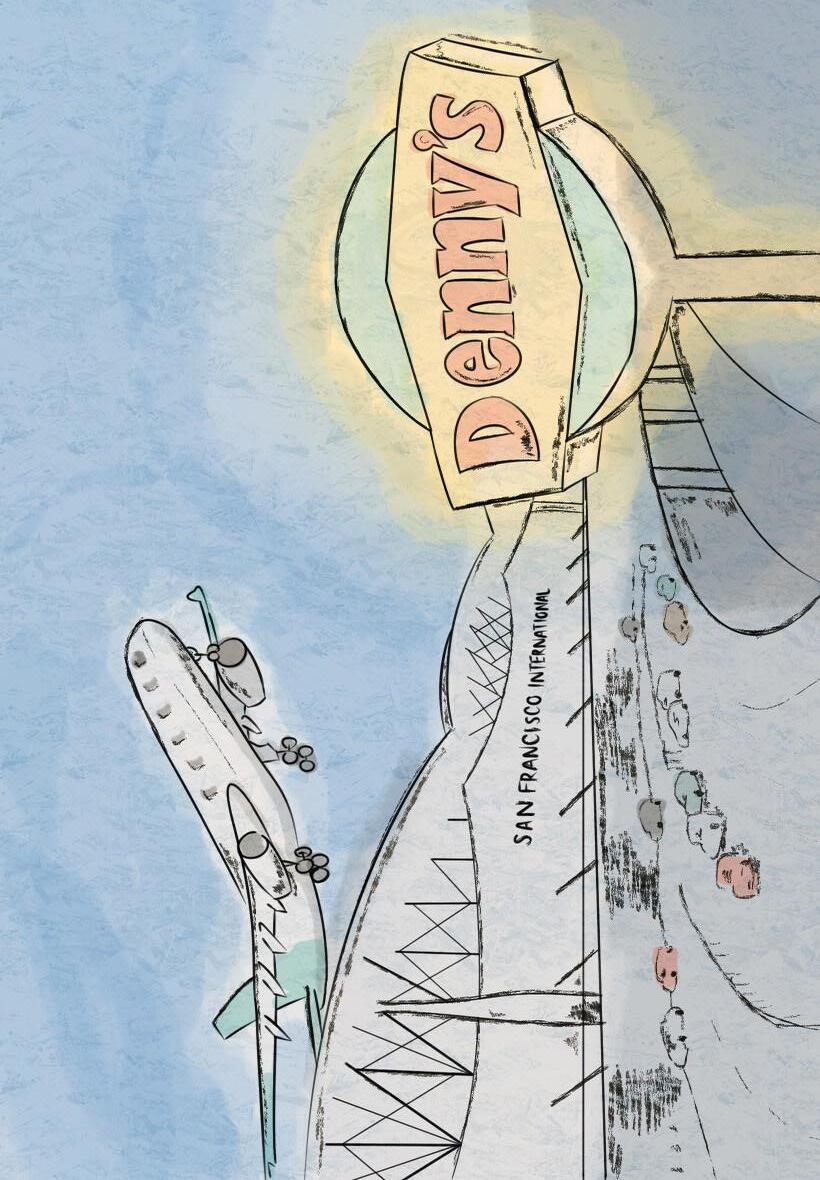

26 | I Left My Heart in San Francisco

Daishalyn Satcher

For Daishalyn Satcher, love is a place, not just a person.

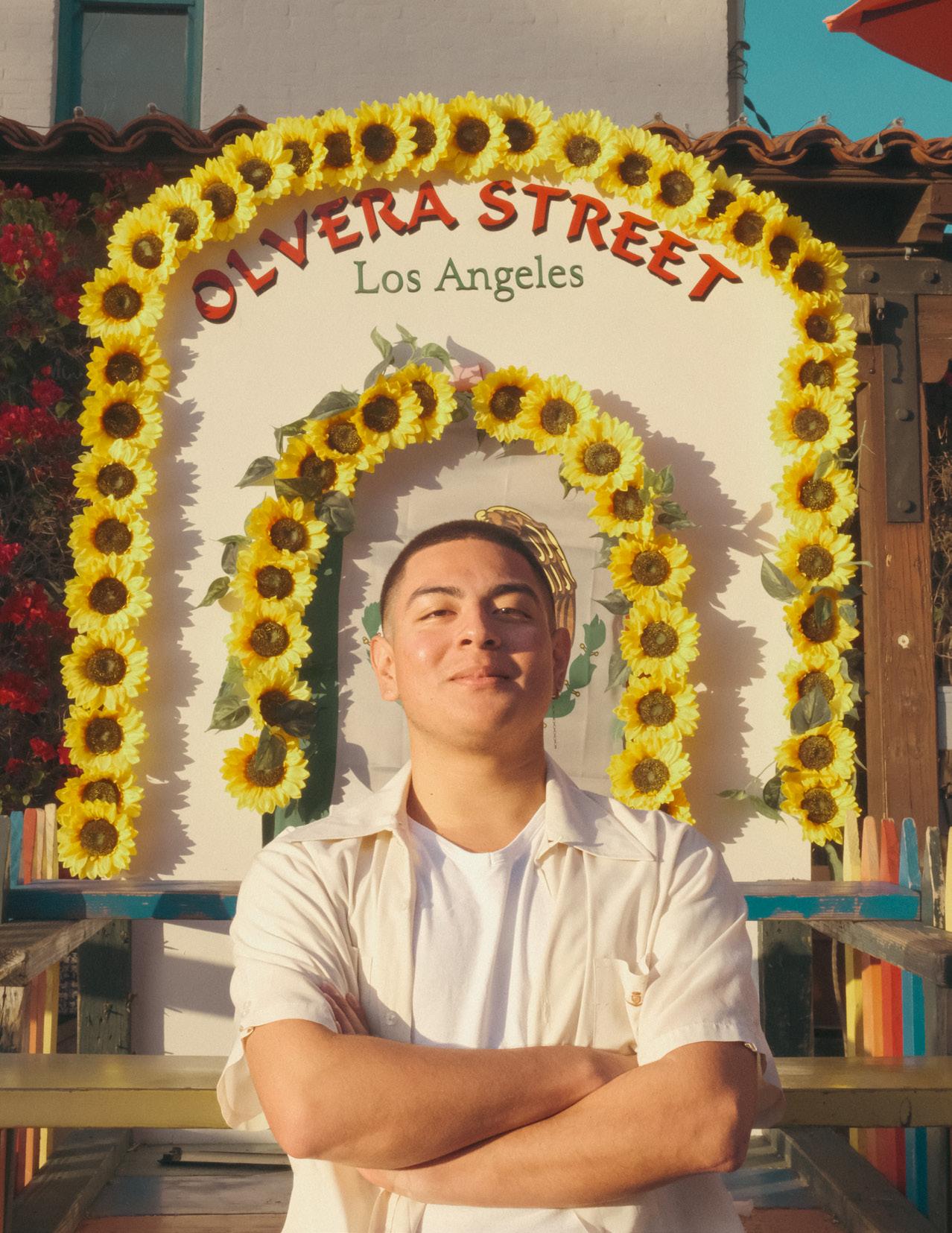

36 | Tesoro

Laurie Carrillo

Edward Chanquin talks about love languages lost in translation. For him and his family, love exists in words unsaid.

50 | The Art of Self-Loathing

Kendall Bradwell

Kendall Bradwell was her own worst critic. But what happens when she experiences an enemies to lovers trope... with herself?

62 | How to Love Yourself, According to your Love Language

Maya Packer

Missing words of affirmation this semester? Fret no longer, Maya Packer presents a college student-friendly guide to self-love.

70 | Is Queer Love Queer?

Anthony Slade

Mel Persell, Arjun Bhargava and Vale Díaz think love isn’t so straightforward, especially for queer communities.

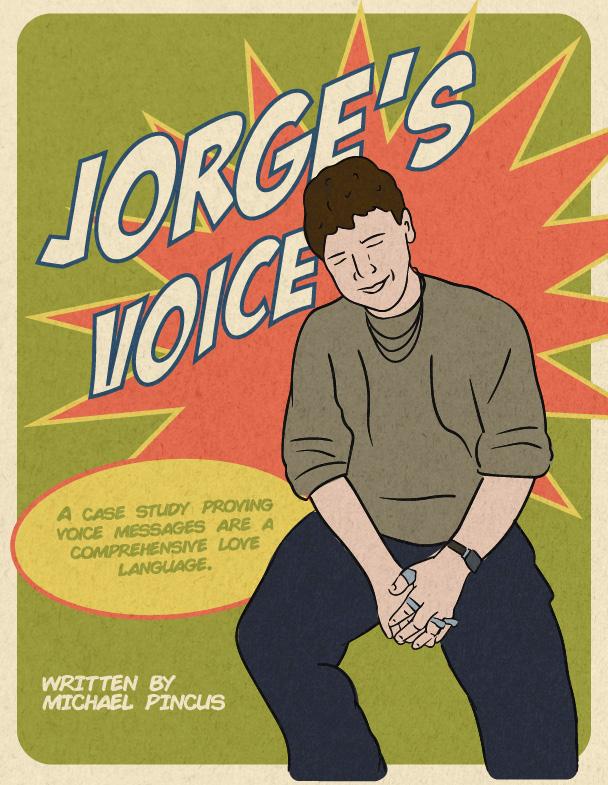

84 | Jorge’s Voice

Michael Pincus

As told through a whirlwind summer fling, Michael Pincus argues that voice messages are a comprehensive digital love language.

94 | Too Close, Too Much

Andrea Arcia

Are situationships fated to crash and burn? Andrea Arcia describes the danger and intimacy behind the fleeting feelings of young love.

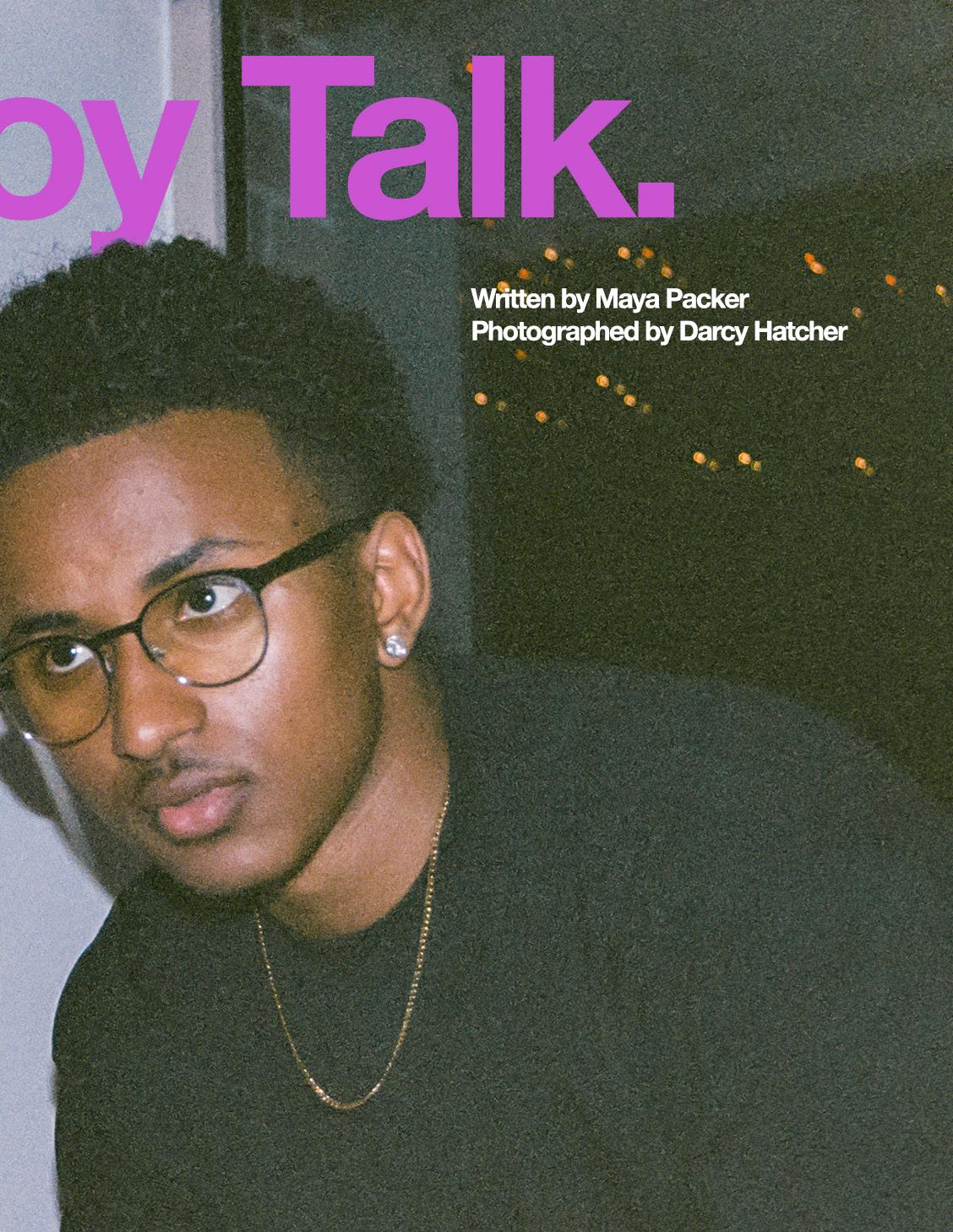

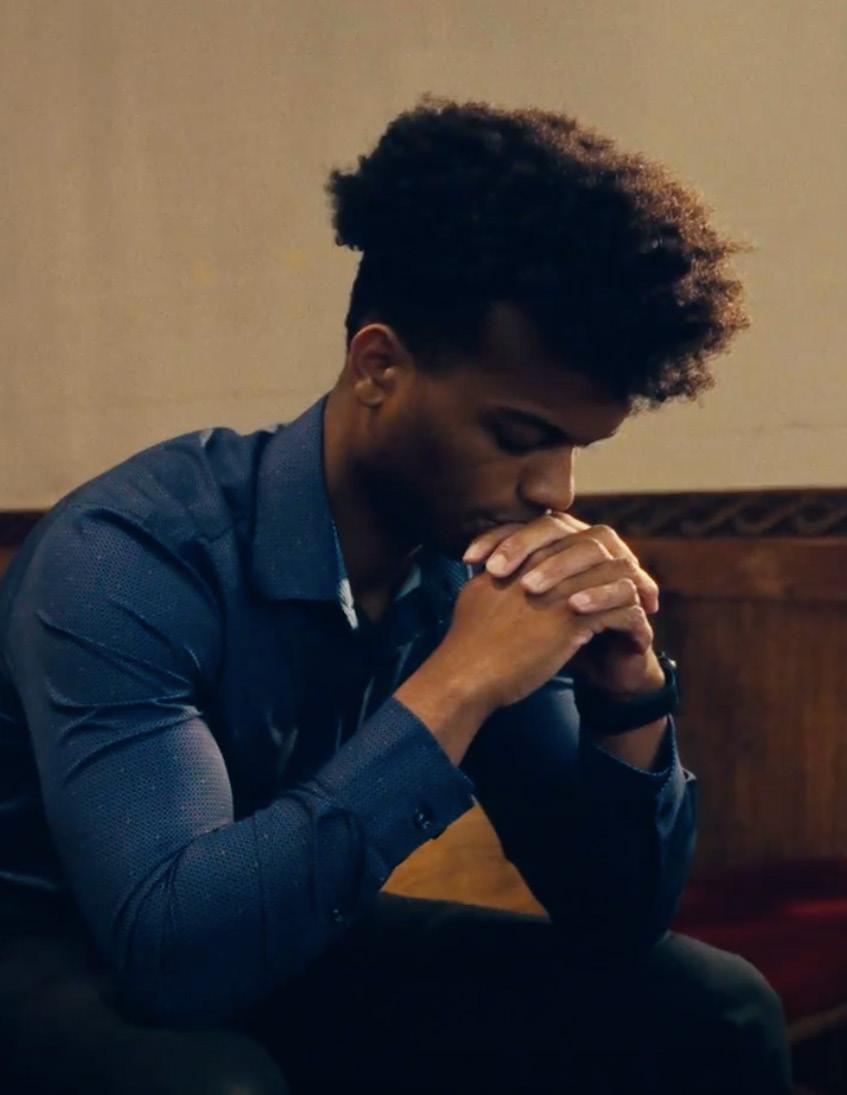

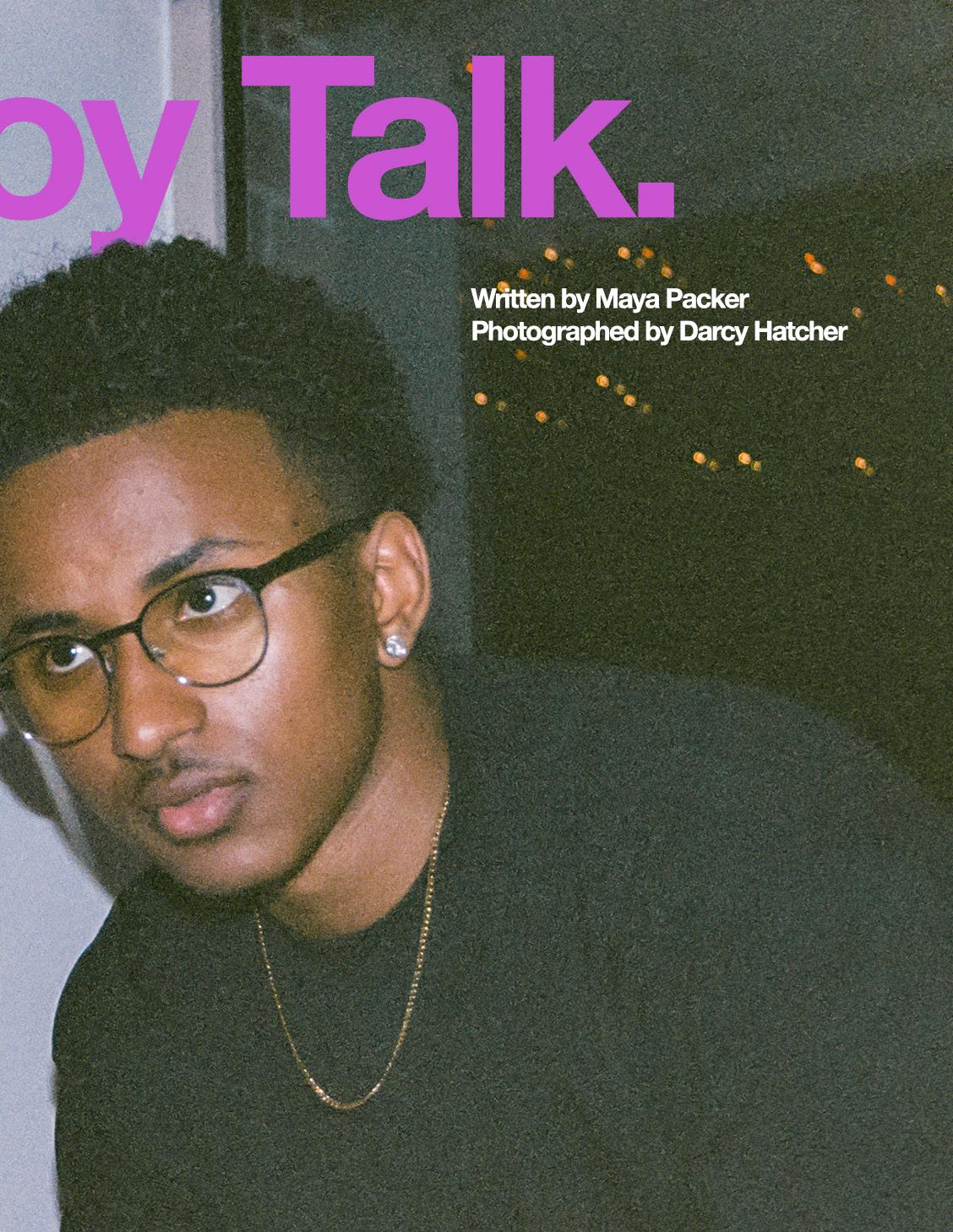

110 | Boy Talk

Maya Packer

Charlie Arnold, Vincent Demonte, Philip El-Chemali, Sam Stack and Donald Ward talk — in an era where male vulernability is so hushed.

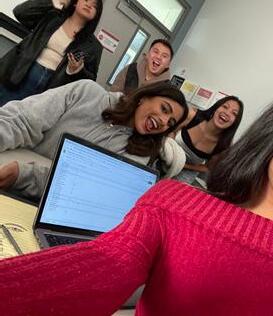

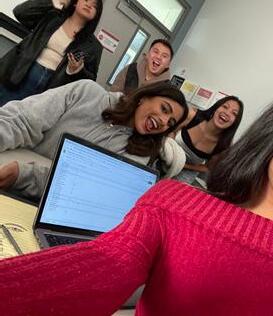

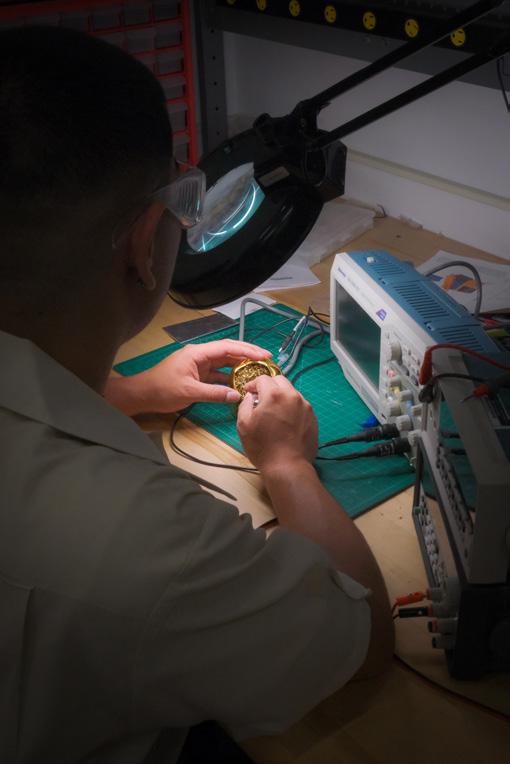

124 | Behind the SCenes

Get a glimpse into the making of Issue No. 3, “The Universal Language.”

2

No. 3 | Spring 2023

Issue

SPECIAL THANKS TO...

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF | Julia Zara

CO-CREATIVE DIRECTOR + SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER | Kassydi Rone

CO-CREATIVE DIRECTOR + VIDEO PRODUCTION MANAGER | Asha Oommen

DIRECTOR OF WRITING | Via McBride

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY | Luqman Abdi

DIRECTOR OF DESIGN | Kathryn Aurelio

CO-DIRECTORS OF MULTIMEDIA | Benjamin Turnquest + Zach Shenouda

DIRECTOR OF FUNDRAISING + EVENTS | Aadhya Sivakumar + Kayla Rocha

WRITING

Andrea Arcia

Anthony Slade

Kendall Bradwell

Laurie Carrillo

Maya Packer

Michael Pincus

PHOTOGRAPHY

Cole Sun

Joyce Kim

Rebecca Speier

Tomiko Younge

MULTIMEDIA

Chris Young

Daishalyn Satcher

Ian Jackson

Jazmyne Aquino

Kayla Li

Kiana Ong

Olivia Brancato

Smriti Marar

DESIGN

Anna Fang

Laura Pisciotte

TALENT + CREW

Alani Smith

Alex Thomas

Ava Siegel

Benjamin Papp

Caden Chung

Cameron Arthur Morris

Cole Lindsay

Charlie Arnold

Danielle Malingue-Essomo

Donald Ward Jr.

Edward Chanquin

Enzy Jvar

Eric GyuMin-Choi

Ethan Galbraith

Flynn Wilburn

Frank Perazzini

Hannah Gardiner

Hannah Wiser

Jayna Dias

John “JD” Davillier

Katy Kragel

Kyra Aligaen

Kyra Horton

Lizzie Lee

Lorenzo Hinojosa

Maya Sta. Ana

FUNDRAISING + EVENTS

Miguel Bernas

Olivia White

Pablo Emiliano Torres-Lopez

Philip El-Chemali

Rainbow Ragan-Johnson

Sam Stack

Samuel Tang

Saneel Sharma/RA Oblivion

Siara Carpenter

Skye Maulsby

Slaterrose

Tammi Sison

Thomas Endashaw

Tiffany Rodriguez

Vincent Demonte

Yoav Gillath

Guest photographer:

Darcy Hatcher

On my plate sits a smoked salmon and spinach omelet. I dig into it, knife and fork in hand, pausing to sip from the hot cafe latte on the table. “Slow Dancing in the Dark” by Joji plays over the chatter of families and the clanking of kitchen utensils — a curious song choice for a popping brunch place in Old Pasadena, I think to myself.

“So,” I say in between mouthfuls of potatoes, “one of the ideas we had for the next issue is love. It applies to everyone, however you experience it. Friends, family, partners, everything.” I take another sip of my coffee.

My mom pipes in immediately: “Ooh, that’s a good one,” she says.

My dad takes a second longer, digesting the idea alongside our breakfast. “I like that,” he says, “because love is for all people, no matter who you are.” He pauses. “What’s the saying? I think it’s, ‘Love is the universal language.’”

Hence, Issue No. 3 came to be (thanks dad).

I know what you’re thinking. What could a group of ragtag college students possibly know about love? Well, I guess we don’t know anything, and that’s what makes it so beautiful. Because at the end of the day, I don’t think love is supposed to be known. Love is supposed to be felt. Experienced. Shared. Grown. Exchanged. Lost. Failed. Found. Over and over again.

To me, love is in the moments

like the one shared with my family at breakfast. It’s long car rides to watch my brother play the sport he’s passionate about. It’s late night conversations with my friends, gathered underneath the orange string lights of our living room as we talk about crushes gained and gotten over. It’s check-ins with my SCene team, asking them, “What’s one thing you’re looking forward to today?”

To those captured between these pages, love is in the moments of getting over someone from our pasts. It’s not knowing what we want for ourselves. It’s the antidote to self-loathing. It’s the couple dancing in the window across from ours. It’s breaking down in the arms of others when we’re hurt. It’s music. It’s voices. It’s queer. It’s a feeling that flees. It’s a feeling that stays.

So, if there’s one thing that I learned during the production of this issue, it’s that love certainly isn’t easy. But if navigating the 300% growth of SCene this semester — from the number of applications we received, to our first fundraising event (blind dates, anyone?), to innovative design ideas, to the overflow of multimedia projects, including post launch content — is necessary to capture what love means to college students in this stage of our lives, then that’s what we’ll do.

We recognize that this issue

doesn’t carry all types of love, because love can never truly be captured in its fullest form. But as humans, we can certainly try to get as close to it as possible, in the art we make, in the stories we share and in the moments we relish in every day.

As always, thank you to our SCene team for tackling this complex topic. It’s not easy to follow up a magazine that was recognized as one of the best student magazines in six states/U.S. territories by the Society of Professional Journalists for our fall 2022 issue, but you did it with grit, passion and excellence. I extend my heartfelt love to your ingenuity and your brilliant minds. And thank you to our spring talent for opening your hearts to us, sharing and recreating your ideas of love with the world.

In the words of Issue No. 3 poet Kyra Horton, “Love is the universal language, the universe’s language.”

If that’s the case, then I can’t wait for you to listen to love. To translate it. To speak it into being.

My ears are perked. Tell me, what is love to you?

4 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

.

Love is not cordial. We don’t get to shake hands with this emotion. Because it’s so much more than just a feeling. It’s an integral part of the human experience.

It introduces itself immediately to us — somehow managing to burst through the seams of the very first stitch in the fabric of our being. Love has known us since birth. But how long have we known it?

Of course, that answer varies from person to person. Some of us can recall our earliest recollection of the happiness that accompanies love, and others of us are still wondering where that type of joy begins.

But, arguably, the bottom line is this: We are the most conscious of the love we are giving, receiving, or even lacking, right here and now.

Issue No. 3 is a glimpse into this unparalleled experience of exploring love as young adults. A time where we start to recognize the ring that our childhood home’s address has in our ears. A time where all those midnight conversations about partners and families are suddenly within a few years’ reach. A time where the reflection staring back at us begs the question: Doesn’t this whole journey start here?

Because love is so innate to us, it’s one of life’s few experiences that requires just as much unlearning as it does learning. We finally

start to catch ourselves in the act of creating expectations based on the love that we have seen and heard growing up, whether it was from a cheesy rom-com or a collection of raw moments.

It’s intimidating to base your perspective of love on a singular reference point, or lack thereof.

And sure, those things had no choice but to shape us. But we are malleable beings. We can create new molds of what love means to us whenever and however we so please. Meaning, we don’t have all of the answers right now. SCene is merely capturing a formative snapshot of an evergoing discovery.

So, while we can use what we know to guide us in navigating how we want to love and be loved, it’s ultimately up to us to lean into this search for meaningful connection.

Love is the willingness, the active choice, to try to understand the world and the people within it, even at times when you feel the most misunderstood. Love is the Universal Language. And we hope that the stories you are about to immerse yourself in translate meaningfully to you.

5

CO-CREATIVE DIRECTORS

A SCENE MAGAZINE PICTURE WHAT IS LOVE?

WRITTEN BY KYRA HORTON

what is love?

a language we speak so fluently it doesn’t even need to be spoken.

it’s melodies created from the heart, the songs i only share with you. transcribing the ugliness of my mind into something beautiful. creating love from tragedy.

it’s the photos i capture to hold this moment forever. the memories that never have the chance to fade. the memories that refuse to let you forget them.

Tiffany Rodriguez ‘25 is a neuroscience major from North Hollywood, CA. She sits in a bed of flowers at the Palisades Park in Santa Monica, CA.

WRITTEN BY ANDREA ARCIA

PHOTOGRAPHED BY LUQMAN ABDI

Tiffany Rodriguez ‘25 is a neuroscience major from North Hollywood, CA. She sits in a bed of flowers at the Palisades Park in Santa Monica, CA.

WRITTEN BY ANDREA ARCIA

PHOTOGRAPHED BY LUQMAN ABDI

Iused to consider nostalgia torturous. An affair absent of logic and continuity. In its grips, even those who’d hurt me in the past could permanently taunt me — romanticized versions of them longing for my attention and (despite my attempts to evade them) shadowing my every move. It never mattered how many summers I spent abroad in Europe or the miles I moved across the country; the loss of those once intimate to me lingered like an open wound, aching to be sensed again and again. The nostalgia born from their losses begged me to confront a single truth: That my life had completely changed. That the bottle blonde who stared in the mirror was a stranger. That Adam was no longer in my life, and it’d been years since we’d spoken. In a world unknown, nostalgia would shout that I recognized no one and convince me I was completely alone. And though the thoughts were intermittent — they dwindled in the face of this distraction or that — they always failed to cease altogether.

Nostalgia, I found, was as relentless as the months in my life that dragged on without him.

The whole ordeal made me think of first love as one’s very own garden of Eden: Blind paradise in its confines, sinful in its exile.

In the years since I moved out of our hometown (a hidden suburbia in New York’s concrete jungle), my longing for Adam weakened. Recollections of him were hardly as consuming as they once were, and fortunately, never had it come close to how it felt at the beginning — the sensation that my own body was betraying me, all of my vital organs failing one by one, and despite my pleadings, failing to fight for salvation. I had never before felt so incomplete. It was then, falling apart in my mother’s arms during the June of my seventeenth year, that I vowed I would never become attached to anything or anyone again. Just a few weeks later, I entered adulthood accepting the one thing I knew to be certain: There was nothing in this world I could call my own. Nothing at all.

I hardly remember what had been going through my mind that somber summer, and for that, I consider myself lucky; since then I’ve found refuge to a certain degree. I’d forgotten. What did his voice sound like again? Why did we ever get along in the first place? My mind became devoid of explanations — the memories of our four years together erased as if they’d never existed. Was he fictional all along, I wondered, as real as

10

For a long time, I believed I loved too much, too genuinely. I’d accepted it as my fatal flaw.

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

Rodriguez’s favorite movie is René Laloux’s Fantastic Planet

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

Rodriguez’s favorite movie is René Laloux’s Fantastic Planet

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

characters in novels I read years ago? As the Brooklyn brownstones became California palm trees, the blanks became more and more frequent. It’s true, I figured; ignorance really is bliss.

In the form of amnesia, the heavens above offered me a glimpse of serenity. But even then, even after I thought I had moved on, grief stubbornly persisted — creeping up on me within the lines of a song or the smell of a campfire, reminders of him resisting to vanish as entirely as he did. With time, curiosity took over. I’d forgotten most of us, but forgetting made room for fantasy, and, as most of you know, our minds are trained to fill in the blanks. To make them bigger in your mind than they were in the flesh. You play make-believe, grasp for the pieces of them lying dormant in your mind, and again, you miss them — even if the image you cling to is hardly them at all.

I thought perhaps the issue was not him but who I was when we were together. I told myself there was nothing left to do but eradicate all traces of the person I was in his embrace — the doe-eyed brunette who naively entered the garden of Eden, getting into a relationship before she knew what that even meant, tragically falling for forbidden fruit. So I did. In her wake, a colder woman emerged. She was cautious, self-indulgent and hyper-independent. But mostly, she was scared. Scared of what would come if she made the mistake of letting anyone in again, terrified she would again have to venture into her mother’s arms, crawling on her hands and knees. Nothing could hurt her because she wouldn’t let it — no longer would she be tempted by hissing snakes. She’d expect disappointment, anticipate betrayal and break her own heart before someone else could get the chance. But just as it sounds, this too became unbearable.

I had gone from living to surviving — my most naive decision of all.

For a long time, I believed I loved too much, too genuinely. I’d accepted it as my fatal flaw. Aayah told me all the time that I saw the best in people, and though it’s a lovely trait, in a world like ours, it’s a liability. People take advantage, milk us for all we got, and walk away unscathed. Following my exile, those parts of myself did not survive. I reckoned they made me far too ignorant, and I vowed never to approach love so innocently again. But in surrendering the version of myself that could breed love even in its absence, the parts that made me who I was, I did not become stronger. I became alienated. Not because he walked away, but because once he did, I too folowed suit.

14

Love is beautiful. Call me a sucker, even a fool, but in committing to that belief, I’ve been able to reclaim the parts of myself I had shunned away out of fear.

(On right) Pablo Emiliano Torres-Lopez ‘24 is a business administration major from Phoenix, AZ. His favorite movie is Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane.

(On right) Pablo Emiliano Torres-Lopez ‘24 is a business administration major from Phoenix, AZ. His favorite movie is Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane.

At times, the world is not a pretty place, but I’ve learned that love makes it bearable. Love gives us the courage to forge ahead. And if you ask me, it’s why we’ve been put on this earth, not to search for love, but to embody it. I know my strength. I prove it to myself time and time again. In the face of pain and loneliness, I have persevered, pushing and fighting to unearth territory of my own, one that pales in comparison to the gardens I’ve left behind. I’ve crawled and tripped through endless earth to find nothing but myself at the end of the trail. The woman I uncovered was scarred and bruised, but in her own paradise, never had she been more sure of herself. Contemplating my past, I figured I couldn’t at all resent my time in Eden or the woman I was before stepping onto its grounds. It was merely proof that I had succumbed to my lowest point and endured. Standing as a testament that I have wholly loved and dismally lost, but that it was not the end of me. A reminder that there is nothing life can throw my way that I won’t be able to handle — granting me the resilience to love again and again, without the worry that I won’t be able to survive.

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

19

Love is beautiful. Call me a sucker, even a fool, but in committing to that belief, I’ve been able to reclaim the parts of myself I had shunned away out of fear. When a relationship ends, especially our first one, our primary instinct may be to turn away from love. But there is no better time to lean into it. No better time to redirect it to yourself. Two years after my relationship’s end, my greatest feat has not been moving on. Nostalgia still triumphs from time to time (I’ve found that love can persist in appreciation of shared history, even from afar). But here from Eden, I’ve rediscovered myself in the understanding that love isn’t a liability. It’s our biggest strength.

It makes me think now that Eden is not a shame to carry but a saving grace. And though loss can ache like a wound to the soul, we perpetually watch the wounds on our skin scar, and never do we doubt its ability to heal.

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

EVE WITHOUT ADAM | Andrea Arcia

EVE WITHOUT ADAM

EVE WITHOUT ADAM

what is love?

it’s those late nights laughing so hard that joy leaves its imprint in my body. not remembering how it started hoping it never ends. doubled over exchanging breath for joy.

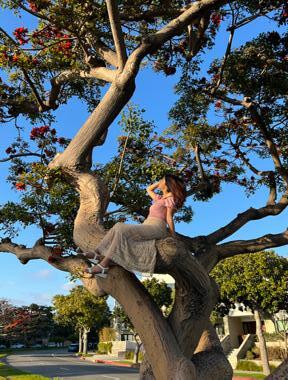

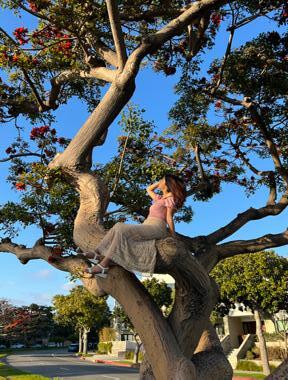

I see a Denny’s off the side of the road. I zone out, and all of a sudden, I’m transported back to the front seat of my grandfather’s car. Papa just picked me up from SFO in his airport shuttle. We’re on the way to Denny’s for a pit stop before going into the city. Whistling along to a James Brown song, he looks over at me with a big smile on his face. The windows aren’t fully closed, leaving just enough space for a gust of fresh air to push its way in alongside the sound of salty waves, splashing beneath the bridge. Sometimes we talk the whole drive, my grandfather pointing out all of the new buildings being developed in the area. Other times we sit in silence, just admiring the view. I look out the window, thinking about the fun that awaits us: Visits to the pier, drives to the beach and the best seafood on the West Coast is waiting for me.

We cross the Bay Bridge, my favorite bridge, into Oakland. My heart is content knowing there is a house full of family waiting for me, all surrounding the T.V. for the Warriors game starting in half an hour. When the car pulls onto the slick driveway, finally, I’m surrounded by fellow die-hard Dubs fans. I walk through the door of my grandma’s home, welcomed by hugs and a steaming bowl of gumbo sitting on the table. I’m back.

But the funny thing is, even before I see my people, I get that indescribable feeling of home. Every time, as soon as I land.

San Francisco is the corridor to many of my fondest childhood memories. It’s not the place I’m from, it’s not the only place, but it’s mine. For a place like this, I don’t have to go searching — it’s always there, a portal back to my nostalgia.

If you haven’t found your place yet, you will know it once you do. You may not find the right words to explain it, but it’s yours.

I think everyone has a place, or at least I hope they do. A place to go where the noise becomes silent. Whether it’s a secret study spot around campus, the park down the street, or something as grand as the Eiffel Tower, we can envision a place when we think of love. I mean, there’s a setting to every kind of love story; the best places inspire them. Sleepless in Seattle, “Vienna” by Billy Joel, the English countryside romance that is Pride and Prejudice. Maybe for you, it’s the place where your most epic romance started, or maybe it’s the place where you watched another unfold. Whether it be the people we met there or the stillness of it all, love for a place holds such significance. It’s a type of love and mere appreciation that is different from any other. It’s one-sided in the most fulfillling of ways.

Places are reliable, holding the capability to make us feel as if time is standing still. Places stay longer than people do, and they rarely leave us; we leave them, only when we’re ready. Places can have a magnetic effect, like the electrifying energy of Times Square in New York City, or they can be appreciated for the smaller details, like that particular spot right behind the letters of the Hollywood sign where you can see the skyline of Los Angeles from afar. Either way, they leave an impression. They have their own qualities that make them special, and it’s up to us to determine what those qualities are. There is no wrong answer.

For me, it’s the little things that are captivating — the details I didn’t even realize made me feel at home. It’s a house. It’s a streetcar. It’s a patch of grass in my great-grandparents’ front yard, specifically right before sunset. There doesn’t need to be any chaos to entertain. Just silence to marvel in.

In San Francisco, the weather is overcast, but the city looks beautiful against a cloudy white haze, so it doesn’t matter. The people aren’t anything special, but they aren’t like the ones at home, in a good way at least. Music plays soft and low, bumping between buildings and corner cafes. If you listen closely, it’s a saxophone sweetly singing the instrumental version of my favorite song. This place, though ordinary to most, is extraordinary to me for the smallest reasons.

Love for the familiar is a predictably comfortable one. A sense of comfortability is rarely unwanted. It’s a deeply personal feeling that can’t fully be understood by anyone else, which makes it all the more beautiful. To others, a scene may look like just an ordinary house on a hill, but to you, it’s a palace where you envision spending the better part of your life. The love for the familiar is a nostalgic one, one you always want to come back to, like your childhood home, where you smiled the most. You love it for what it is, but you also love it for what it was. It doesn’t take much to bring you back. A melody, a photograph, or even a laugh can bring you back for a moment, to your place. For me, that place is San Francisco. I like the bridges there.

WANT MORE? SCAN THE QR CODE TO LISTEN TO LOVE LETTERS WRITTEN BY USC STUDENTS IN THE LATEST INSTALLMENT OF “THE DAISH DIARIES”: UNWRITTEN LOVE LETTERS.

34

35

Animation by John “JD” Davillier

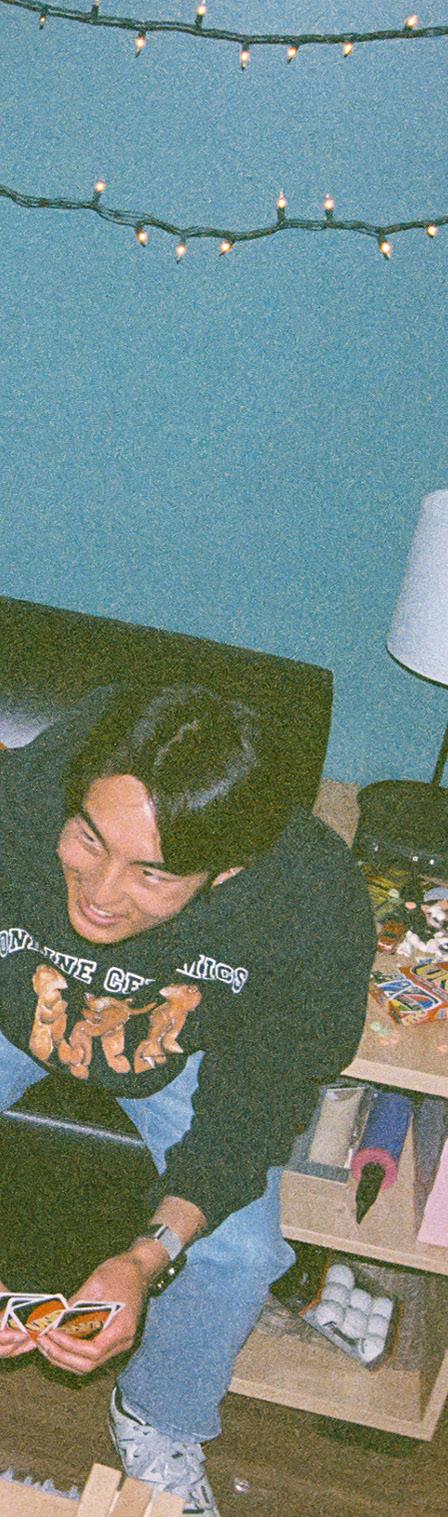

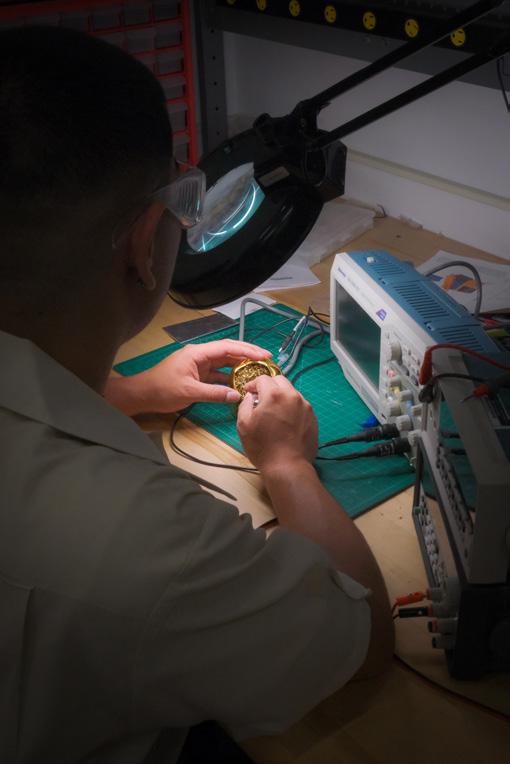

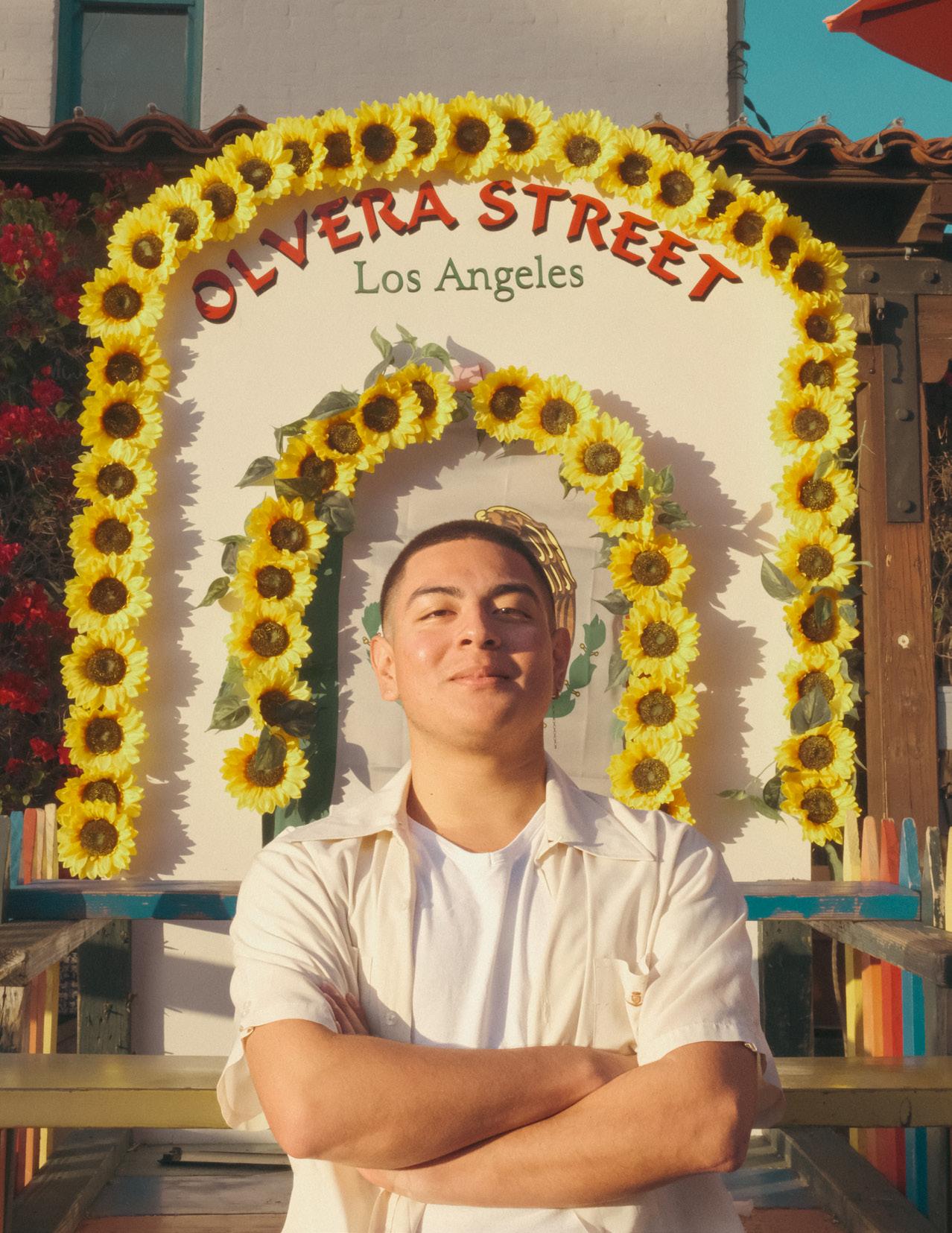

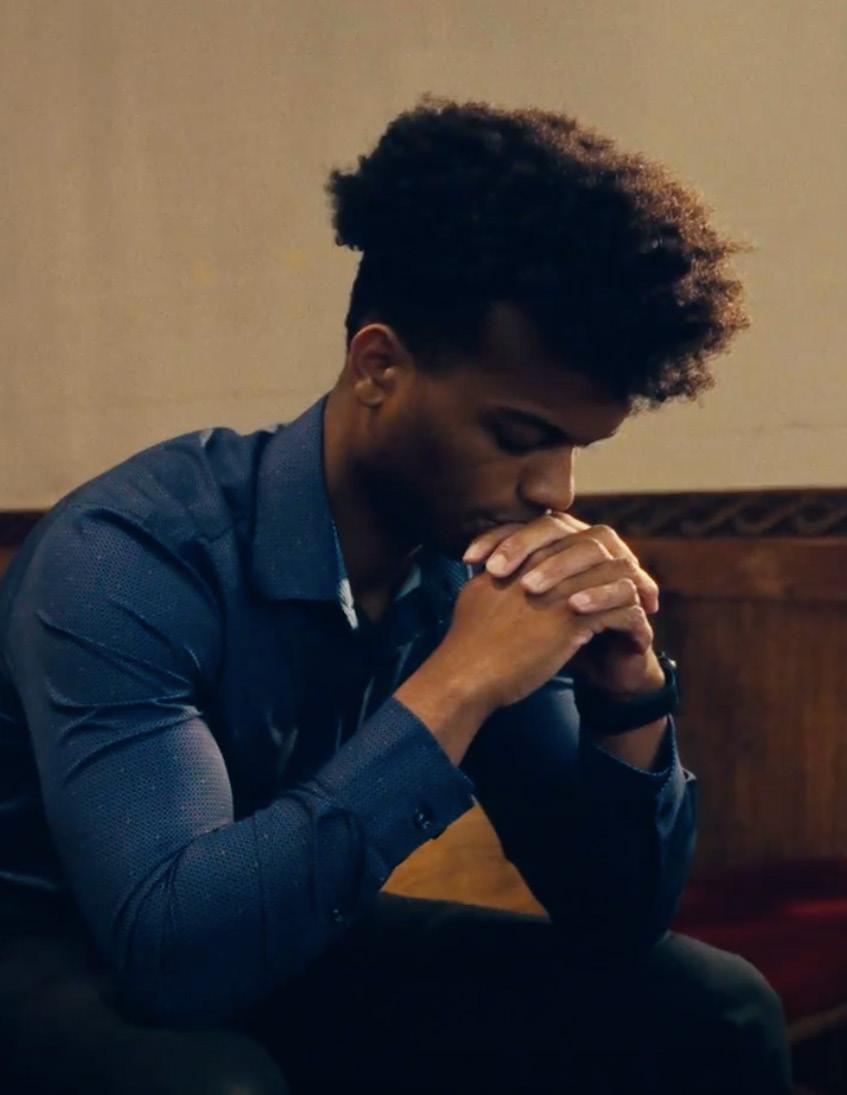

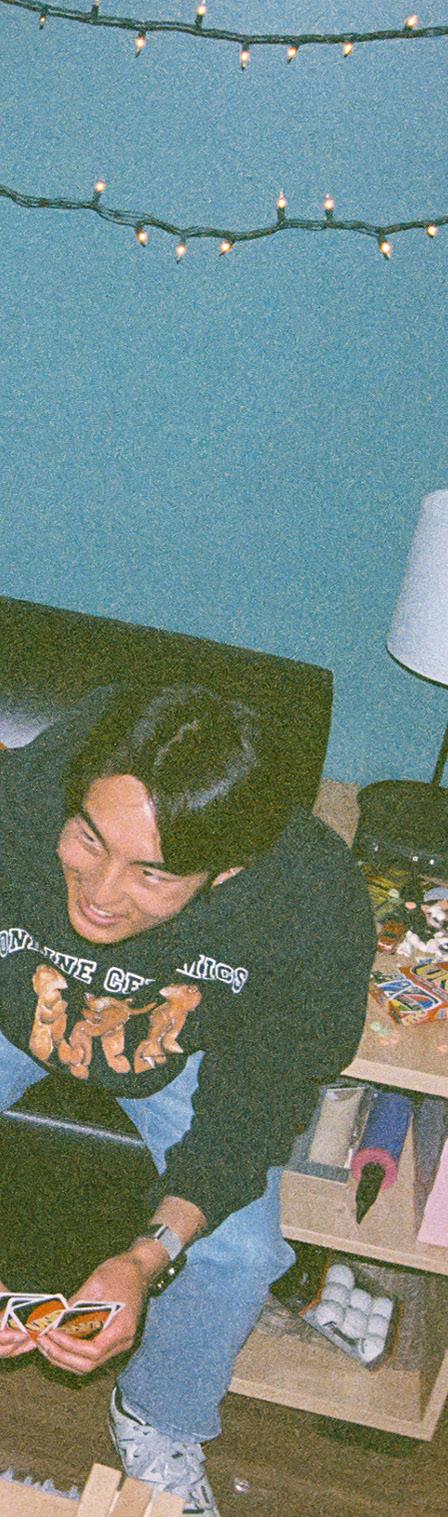

Edward Chanquin ‘25 is an arts, technology and the business of innovation major from Los Angeles, CA.

Edward Chanquin ‘25 is an arts, technology and the business of innovation major from Los Angeles, CA.

TESORO

Written by Laurie Carrillo

Photographed by Luqman Abdi

Photographed by Luqman Abdi

38

Edward Chanquin was nine years old when he read his parents’ immigration documents for the first time. There was a pile of mail on the kitchen table, but for a household of seven, that was nothing unusual. A logo sat on the corner of the envelope, indicating one of those alphabet agencies the average elementary schooler is definitely not familiar with.

He tore open the letter and stared at the mass of English text. His mother, a non-English speaker, told him, “Es nada, Eddy” — ‘It’s nothing,’ — before folding the papers and placing them back on the table. But Chanquin had already read it, shock quickly replacing his confusion. At that moment, he became overtly conscious of the struggles his parents were facing. To this day, he carries that memory with him, unable to shed it.

Chanquin is a USC Iovine and Young sophomore majoring in arts, technology and the business of innovation, a first-generation college student still trying to figure out who he is. Raised in South Central Los Angeles, he’s the child of Central American immigrants. His background and family have painted broad strokes all over his life canvas, giving him a base as he traverses through life. Now, he tries to hold the brush more firmly as he decides what comes next.

I’m a child of immigrants myself, my parents hailing from Colombia. I know what it’s like to grow up with the pressure of taking my parents’ past and making something beautiful out of it. I chase success because if I don’t, I feel like they left their home for nothing.

Even so, my story isn’t Chanquin’s, and his isn’t mine. Not just because we come from different countries, but because there’s no one way to immigrate to the United States. There are a million different reasons for someone to decide to leave their country and so many ways to cope with that decision. The way us children of immigrants incorporate that story onto our canvases varies, too.

“USC is so diverse, and there are so many Latinos. But there’s still a disconnect because we all grew up differently,” Chanquin said. “The term ‘first generation’ itself can mean so many things because all our circumstances are so different.”

But one common thread unites us, no matter where we come from: Love.

39

The love that compelled our parents to make that life-altering decision in the first place. The love that keeps them fighting for a better life. Love for themselves, their families, for an imagined future they must construct from the ground up. Love holds the pen that writes that story of resilience and it never lets go, even years down the line.

Retrospectively, Chanquin knows that. When he was growing up, sometimes love languages got lost in translation.

His parents’ pasts remain elusive to him still. He doesn’t know all the details, but he knows they left crippling destruction in their home countries. Petrona Barrientos, his mother, fled Santa Ana, El Salvador in the 1980s when the civil war made her feel like a target in her own home. When explosions reverberated across the city, she packed her bags and fled to L.A.

Meanwhile, Guatemala’s civil war was killing thousands of indigenous Maya when Chanquin’s father, Antonio Chanquin, an indigenous man from a rural town who only spoke his native tongue, was left with no choice but to leave the strife behind.

In the U.S., Chanquin’s father would spend hours in Home Depot parking lots looking for an employer to hire him for construction jobs — while Barrientos cleaned every inch of offices and homes for only a couple dollars an hour. There were nights when Chanquin wouldn’t see his parents until late, nights when he had to figure out what to eat for dinner on his own because they were out doing the heavy lifting.

During every decision of his life, his parents were occupied with supporting the household. They don’t speak English; they don’t know how to maneuver the American education system or technological devices. Their focus is to work, for hours upon hours every day, sleep and repeat to pay the bills.

With them unavailable, Chanquin had so much independence, he didn’t know what to do with it. That didn’t just mean having to do his homework or filling out the FAFSA for the first time by himself, it meant he grew up not knowing what he could aspire to become.

“I had to be an adult at such a young age,” Chanquin said. “Their problems became my problems and that was the pressure I faced, not them telling me what to do.”

Physical manifestations of love don’t come easy for Chanquin. That may not be unique to immigrant

families, nor is it universal to all of them. But for Chanquin, his family’s background and their different ways of expressing love are wholly intertwined.

I’ve seen my own family go into autopilot, working to keep food on the table. Immigrants sometimes internalize their own struggles, their emotions, putting up an iron-strong shield to keep going.

Growing up, his father, especially, seemed like a closed door, an impenetrable barrier, a figure of discipline. Chanquin couldn’t help but inherit that reserved nature himself.

“I just learned to suppress my emotions, and it’s really difficult for me to express them,” Chanquin said. “One of my brother’s partners told me that my whole family was like stones that had to be cracked open because we didn’t show anything.”

Chanquin said he owes his mother for bridging the gap between him and his father. While she calls him her tesoro, her ‘treasure,’ she explained to him how his father used food to show his care. Bringing him a bowl of diced cucumber, mango and orange sprinkled with tajin and lemon was his father’s way of expressing love.

“She opened my eyes, told me that they didn’t receive affection when they were growing up, but they were trying,” Chanquin said. “It was his way of trying to break that distance between us. He was trying.”

College changed everything in a way that sounds almost cliché. His relationship with his parents, the way he sees himself, what his canvas looks like. College is the turning point for children of immigrants, like the second chapter of our lives where we take the pages our parents gave us and make stories wholly our own.

When COVID hit, he chose to stick close to home. His parents couldn’t work through the pandemic, and a sense of obligation and love for his family kept him tied to L.A.

“I can’t leave. I can’t escape this poverty, but at the same time, I can use this as a way to help my parents out,” Chanquin said. “It made my relationship with my parents better.”

At USC, he found friends that he connected with, not because they related to him but because they were open minded, accepted him and shared his interests. But when school got too challenging, he

40

While she calls him her tesoro, her ‘treasure,’ she explained to him how his father used food to show his care.

Chanquin poses at Palisades Park in Santa Monica, CA.

TESORO | Laurie Carrillo

Chanquin poses at Palisades Park in Santa Monica, CA.

TESORO | Laurie Carrillo

TESORO | Laurie Carrillo

The age gap between Chanquin and his oldest sibling is 35 years.

TESORO | Laurie Carrillo

The age gap between Chanquin and his oldest sibling is 35 years.

Chanquin navigates how he lives and loves in college, remembering the little ways in which his parents showed him love.

TESORO | Laurie Carrillo

TESORO | Laurie Carrillo

turned to his family, to the people who understood him at his very root.

He realized then that he didn’t have to put so much distance between himself and his family to figure out who he is.

“My identity is still so confusing to me because that generational trauma makes it so hard to find myself,” he said. “It’s hard for us to even experience the things you’re supposed to in college because we come from a community where we don’t think about who we are. We’re all the same, we’re all just trying to survive out here.”

Chanquin still hates writing personal narratives. He’s thrown off guard when his friends hug him. He doesn’t know how to approach a guy he’s interested in. He’s still getting comfortable with the idea of expressing love itself, but that doesn’t mean he’ll never get there.

“Love for me is all over the place because I haven’t been given love in the traditional way,” Chanquin continued. “But I’m starting to get to know the small things, like what my interests are, what I like, what I don’t like, what I love.”

With the colors provided to him by his parents, Chanquin now knows that he has control over the brush. He just needs to determine what he wants to create.

44

45

TESORO

TESORO

what is love?

it’s grandma’s prayers. no matter the troubles i face, I know somebody is looking out for me. talking to god for me, making sure everything turns out okay.

The pursuit of perfection is an impossible one. Selfhood should overcome the voices that say we’re not worthy, writes

Kendall Bradwell

WRITTEN BY KENDALL BRADWELL

PHOTOGRAPHED BY TOMIKO YOUNGE

THE ART OF SELF-LOATHING

The pursuit

(From left): Enzy-J’var ‘26 is a dance major from Brooklyn, NY. Danielle Malingue-Essomo ‘26 is an arts, technology and the business of innovation major from Germantown, MD. And Siara Carpenter ‘25 is a journalism from Chicago, IL.

(From left): Enzy-J’var ‘26 is a dance major from Brooklyn, NY. Danielle Malingue-Essomo ‘26 is an arts, technology and the business of innovation major from Germantown, MD. And Siara Carpenter ‘25 is a journalism from Chicago, IL.

pursuit of perfection tore me apart.

Growing up, I felt like I had something to prove. My grades were to be spotless — not a B in sight. My nails were always freshly cut and painted. As the firstborn kid in my family, I aimed to be first in everything: First in my class, first picked in dodgeball, first place in Jeopardy! review games. To call me a perfectionist would be a gross understatement.

As my body changed, I applied this perfectionist mindset to my appearance. Each morning, I woke up at the crack of dawn to paint my lips, sculpt my brows, and draw my eyeliner with precision. I yearned to be a work of art: Awe-inspiring. Beautiful. Flawless.

So, when the gap in my teeth got too big, I squeezed it together with my fingers. If my widow’s peak grew too unruly, I tried to cut it off. When dark marks started populating my cheeks and legs, I slathered every “natural remedy” known to man on them. Eventually, I got braces and mouth gear, so I stopped smiling for selfies. When I couldn’t fit into my favorite pair of jeans anymore, I did everything in my power to pull them over my hips.

Over time, the love I had for myself shrunk, and my insecurities ate away at me. Gone were the days of Kendall, the headstrong, plucky little kid. In her place stood Kendall, the meek and passive young woman. My humor became self-deprecating; I would pick myself apart, in public and in private, leaving me with nothing but a bruised ego and a bleeding heart. I became a walking warning label: “Sorry that I look like a mess right now. Let me know if you can’t read my messy-ass cursive. I know my essay isn’t the best, but tell me what you think.”

No wonder why I’ve had a gray streak of hair since I turned sixteen — I didn’t allow myself to live. I tried to conceal each part of me that I felt I needed to change, yet I still wasn’t satisfied with the results. I waited for the day my “glow up” would come, when I would morph into my grown-woman body, and even after that day came, I obsessively Googled ways I could look fitter or have more curves. I dreamed of getting into “elite” colleges since I was ten, and now that I’m halfway through my time at my dream school, the thought still lingers in my mind: “Everyone here is so talented and hard-working. How did I get here?”

What I had and who I was were never enough. It’s

not like anyone was pressuring me to think about myself in this way. My parents constantly told me that they don’t expect perfection, just my best efforts. My friends always made time to compliment my style or my appearance, in person and online. So, who was I trying to prove myself to?

Perhaps my best efforts just weren’t enough for myself. I was holding myself to impossible academic and beauty standards, and it drove me crazy. I saw the best in those around me, but only the worst in myself. I felt like I would be executed for making a mistake, but the only person building the pyre was me.

I went to such lengths because I wanted to be loved. I needed to become someone my parents could be proud of. Someone my friends wanted to be seen with. Someone worth writing sonnets about. If everyone in my life already loved me, though, that only meant one thing: I didn’t love myself enough.

If self-loathing was an art form, I could’ve opened a museum that rivaled the Louvre. This cycle of building tools of self-destruction to demolish the little confidence I had was a delicious form of torment. I found an odd comfort in talking so poorly about myself, I often didn’t realize I was doing it until my mom or my roommate called me out on it. It was easy to blame my musings on having a dark sense of humor, but at a certain point, finding things to criticize myself about became too easy. The slightest inconvenience caused all of my insecurities to rise to the top of my mind, suffocating me under the weight of my own thoughts. This torment, no matter how simple and sweet, was still torment.

A life of self-loathing was not a life I wanted to live.

If I could tell my past self one thing, it’s that perfection is an unattainable myth. She’d probably spontaneously combust at the thought, but it’s true — there is no person, place or thing on this earth that is universally accepted. All of the little things I disliked about myself weren’t the irredeemable, fatal flaws I made them out to be — they were normal. Inherently, there was nothing wrong with me.

The hard part is internalizing that. I’m still learning to love the whole me — not just the Kendall with

53

THE ART OF SELF-LOATHING

| Kendall Bradwell

Slaterrose ‘23 is a dance major from Houston, TX.

| Kendall Bradwell

Slaterrose ‘23 is a dance major from Houston, TX.

straight A’s, a newly-straightened smile and clear skin, but the Kendall who cries at the drop of a hat. The Kendall who can be too forgiving. The Kendall who laughs too loud and speaks too quietly. The Kendall whose feet point outward, whose stomach pokes out in dresses, and who — gasp — gets B’s and C’s. I’d be lying if I said that each day, I wake up wholly satisfied with the woman in the mirror blinking back at me. Learning to be gentle with myself is a nonlinear process. There are times when I feel untouchable, conquering the day with ease. There are still some times when I stare at my body in a fulllength mirror, making a mental list of all the things I need to change. On days like this, I often dream of someone to complete me. I hope and pray to meet someone who I’m finally enough for, and who will love me unconditionally — flaws and all.

Then I have to remind myself that I’m enough on my own. No number of best friends, boyfriends, or heart-eye emojis under my Instagram photos can determine my worth. It’s not the easiest pill to swallow, and to this day, it’s a truth I can believe one day and abandon the next.

To be loved is to be known, and before anyone else gets to know you, it’s important to know yourself. Dig deep: What do you love most about yourself? What about you makes you feel insecure? Once you discover these things, don’t shy away from what makes you uncomfortable — embrace it. (I threw away my Spanx. I don’t remember the last time I used a filter on my photos. My gray streak is finally thinning.) Slowly, but surely, I’m becoming more comfortable in my own skin.

55

I know — it’s easier said than done. There will always be those days where you want to spend all day in bed because you don’t feel pretty or you feel like a failure. But even on those days when you feel fragmented, or like you’re missing your other half, please know that every version of you is a work of art. In fact, some of the most revered art in the world is flawed: Venus de Milo, the Greek sculpture often viewed as the epitome of beauty, doesn’t have any arms. And in “Sonnet 130,” Shakespeare praises his lover not because she’s perfect, but because she isn’t. Having flaws doesn’t mean you are broken — it means you are beautiful. How can someone else complete you, when you are intrinsically complete? You are a human being. You are composite. You are whole. Each bump, stretch mark, crooked brow and howling laugh make up the mosaic of you. Your body and soul are a temple that demands to be worshipped.

Close your eyes. Listen to your heart. Do you hear the archangels singing?

57

THE ART OF SELF-LOATHING

THE ART OF SELF-LOATHING

what is love?

it’s apologizing and admitting i was wrong. not being defensive. not being offensive. choosing love over anger. choosing love over ego.

Written

Written

by Maya Packer

Designed by Kathryn Aurelio

by Maya Packer

Designed by Kathryn Aurelio

“SELF LOVE.”

I know, it’s been hammered into all of our minds by endless positive messages on social media: “Love yourself!” they say. But even if I do love myself, and am happy with myself on the inside, how do I express that? How do I love myself as passionately as I might love a partner? Oftentimes, when people discuss how they love their partner, they bring up the idea of their love language, stemming from Gary Chapman’s 1992 “The Five Love Languages: How to Express Heartfelt Commitment to Your Mate.” In it, Chapman outlines five different ways people give and receive love: physical touch, acts of service, words of affirmation, receiving gifts and quality time. Here are a few ways you can express love to yourself based on your love language.

Physical Touch

1. Have a pair of comfortable “fancy” pajamas to wear to bed. Think silky or fuzzy textures, whatever is most comfortable for you.

2. Use lotions or oils after you shower. It’s like a mini-massage!

3. Invest in good bed sheets. It makes going to bed so much more exciting, and, honestly, it will change your life.

4. Try stretching or yoga. This is a good way to be mindful while moving your body and taking care of yourself. Also, people who do yoga are just cool.

Acts of Service

1. Be intentional about your chores. Take care of yourself by deep cleaning your room monthly, making your bed, making yourself breakfast and whatever else you know you need to do but always put off.

2. Make appointments for yourself. It could be an exercise class in the Village, a nail appointment or a much-needed dentist appointment. Your future self will thank you.

3. Set up your day. Prepare things you need for the next day ahead of time. Pick out your clothes, pack your bag, set up your workspace. Do little things to make tomorrow easier. It’s like having an assistant, but the assistant is you… and you don’t get paid!

4. Pick a day to do all your dreaded tasks. If you’ve been putting off returning texts or emails, writing a paper, cleaning your room, calling the doctor, going to the bank or other dreaded errands… just do them. Take a deep breath and try to get as much done as you can when you’re feeling productive, so you won’t have to worry about it when you’re not.

Words of Affirmation

1. Write yourself love notes. Whether it’s sticky notes around your room or written on your notes app, write down nice things for yourself to read later. If you want to share the love, put notes up in the communal bathroom!

2. Say affirmations in the mirror. Make it a habit to look in the mirror and remind yourself how amazing you are, or give yourself compliments.

3. Write a letter to yourself. Get creative with this one. It can be a letter to read in a few days, in five years, when you’re feeling sad, when you’re feeling overwhelmed or when you’re feeling lonely. Write it and put it away until you need it.

4. Create an affirming voice memo. This has the same purpose as a letter, but for those who may prefer to talk than write — and listen rather than read.

Receiving Gifts

1. Buy yourself a treat. Next time you go grocery shopping, add something you wouldn’t normally get to your cart. Pick up a coffee or a pastry when you’re having a rough day. You deserve it. If you need inspiration, just walk down the Trader Joe’s aisles and follow your stomach.

2. Make your purchase a gift when you’re online shopping. Most websites have the option to say whether your purchase is a gift or not. Always say yes! You can write yourself a little note and even use gift packaging.

3. Save money for a splurge purchase. It’s not realistic to be constantly buying gifts for yourself, but set the money aside in your budget so you can afford to splurge on something nice. Like a $20 piece of paper from the university bookstore…

4. Buy yourself flowers. Self-explanatory. Plus, Miley Cyrus said it.

Quality Time

1. Set time aside to spend with yourself doing something you love. Maybe it’s 30 minutes of uninterrupted reading time, watching a movie or playing a video game. Make a list of things you’ve always wanted to do but never have. Take time for what you want to do.

2. Try journaling. Handwrite, type or dictate your thoughts. No matter how you do it, spend time reflecting in a meaningful way.

3. Take time away from technology. Turn off your phone, T.V. and laptop. Lay in the grass in front of Doheny, read a book, sit with your thoughts, go on a walk, meditate, journal, cook… do anything that doesn’t involve a screen.

4. Build a daily routine you love. It doesn’t have to be the same everyday, but start incorporating things into each day to improve your quality of life. For ideas on how to spend your time, see items 1-3.

what is love?

it’s a kiss that makes time stop and your past disappear. the kind that feels like your first kiss even though it’s not.

what is love?

it’s, “i cooked this for you.”

i know it’s your favorite and i’d move heaven and earth to see your smile.

IS QUEER LOVE QUEER? | Anthony

Saneel Sharma/RA Oblivion ‘25 is a design major from Hayward, CA. She eats one banana every day

Slade

Saneel Sharma/RA Oblivion ‘25 is a design major from Hayward, CA. She eats one banana every day

Slade

Is Queer Love Queer?

Written by Anthony Slade

Photographed by Julia Zara

Written by Anthony Slade

Photographed by Julia Zara

Love is love,” right? — I mean, it’s practically engraved into my gay little head at this point!

It was only eight years ago when the Supreme Court legalized gay marriage, making the United States the 17th country to do so. And this three-word mantra was the catchphrase of tens of thousands of queer protesters, millions of gay people around the globe and every rainbow mug-owning high school English teacher across America.

By equating queer and straight relationships, “love is love” implies that the two are similar, even identical — so how could we have one without the other? It’s simple. It’s powerful. But is it entirely true?

Now, I need to make it clear that I am a huge supporter of gay marriage — as a matter of fact, the only thing that I support more is gay divorce! But this watered down explanation of queer love follows the same logic as your well-meaning family friend who asks you, “Who’s the boy and who’s the girl?”

Unfortunately for your Uncle Jerry, queer relationships aren’t always so straightforward.

For junior molecular, cellular and developmental biology major Mel Persell, who also is a leader at QuASA, USC’s queer and ally student assembly, queer relationships tend to subvert straight norms.

“Straight people are pigeonholed into these very small boxes,” they said. “For queer people, there’s already a given, like, ‘Okay, this relationship is going to look different than a straight person’s.’ So that means that queer people can branch out even more.” Many of these boxes derive from the historical institutions that straight relationships have standardized. Labels and traditional relationship milestones are often different in queer spaces. Sophomore communication major Arjun Bhargava rejects the idea that a relationship is only valid when it can be easily labeled.

“There are a lot of ideas of how a traditional relationship should play out that don’t always apply to queer people,” they said. “A relationship is kind of driven by straight timelines, like marriage and having children.”

Not only have queer people historically been excluded from these benchmarks for relationships, but we also have lacked role models for queer love. For a lot of us, all we really got was that gay couple on Modern Family, Brittany and Santana from Glee, and

maybe a mysterious gay cousin at the family reunion (you know who you are). Without relationships to aspire to, it might be easier for queer people to enter unworthy relationships.

And Persell says that a person’s first relationship is often telling of the way they will navigate dating spaces in the future. Since so many queer people are often only able to find this kind of attention via “the apps,” queer relationships may be impacted by the romantic tone — or tone-deafness, rather — of an award-winning app that is truly close to my heart: Grindr.

For those of you unfamiliar with the gay hookup app from Hell, God bless you — and I’m sorry, because I’m about to take you on a chilling journey:

Imagine you’re 16, you just started shaving your peach fuzz mustache bi-weekly, you’ve watched an absurd amount of Grey’s Anatomy after McSteamy swiftly became your sexual awakening, and you finally decide you want to see what’s out there for a young, queer kid looking for love. You download the famous gay app and make a profile. What you’re greeted with is a sea of shirtless torsos denoted by vulgar sexual names arranged by their distance (in feet) from your childhood home — not the Call Me By Your Name fantasy that I’d hoped for. Admittedly, I was two years short of the age requirement upon signing up. But 18 or not, for many queer people, this app is a plunge into the ocean that is queer dating spaces.

And a lot of us still don’t even know how to swim.

The shallow, borderline problematic relationships facilitated by the app have seemed to lay the groundwork for hookup culture in some queer spaces. Grindr certainly has not paved the way for romantic emotional connections. Instead, it has boiled queer compatibility down to the ability of its nearly 13 million users to “host” or “travel” (are we hooking up at your place or mine?). So, time and again, these connections can exist in a confusing middleground, somewhere between sidepiece, friendship and significant other.

“I think that [the apps] kind of commodify it in a way,” Persell said. “You’re not going to develop these skills, necessarily, at the same pace, or at the same time, or to the same depth.”

Maybe young people’s attraction to the apps may be coming from a place of unrequited desire.

Because queer people are often forced to repress their romantic and sexual urges, they can have a

72

Without relationships to aspire to, it might be easier for queer people to enter unworthy relationships.

“

IS QUEER LOVE QUEER?

| Anthony Slade

Rainbow Ragan-Johnson ‘25 is a business administration major from Matthews, NC. She identifies as a storyteller, and if you see her in a crowd, ask her about her latest poem.

| Anthony Slade

Rainbow Ragan-Johnson ‘25 is a business administration major from Matthews, NC. She identifies as a storyteller, and if you see her in a crowd, ask her about her latest poem.

IS QUEER LOVE QUEER?

| Anthony Slade

(In middle) Hannah Wiser ‘25 is a communication major from Boca Raton, FL. (In blue) Lizzie Lee ‘24 is a health and human sciences major from Ridgeland, MS.

delayed start into the dating world. Persell, who identifies as a lesbian, said they didn’t have anyone to date in their high school, so they pursued a relationship with someone from a school 30 minutes away from theirs — which, as far as a high schooler is concerned, is long distance.

The trauma endured by queer people surrounding relationship scarcity seems to change the way they experience uncomplicated love when they are finally able.

Vale Díaz, a senior majoring in journalism from Mexico City, happens to find truth in the concept of “U-haul lesbians,” which the Urban Dictionary defines as, “Lesbians, that after meeting someone, tend to move in with that person right away.”

Hannah Gardiner ‘24 (a.k.a. Daisy Darling) is an English literature major from Long Beach, CA. She learned a made-up language over quarantine.

Hannah Gardiner ‘24 (a.k.a. Daisy Darling) is an English literature major from Long Beach, CA. She learned a made-up language over quarantine.

76

QUEER LOVE QUEER?

IS

| Anthony Slade

IS QUEER LOVE QUEER?

| Anthony Slade

(Top left) Jayna Dias ‘24 is an art major from Oswego, IL. (Bottom middle) Maya Sta. Ana ‘25 is an acting for stage, screen and new media major from Freehold, NJ.

“You tend to go into it headfirst, excited and happy about it, just happy that you can care about someone and love someone so deeply and openly,” she said.

Although Díaz clarified that not all queer women are quite U-haul ready, she raises a valid point: After struggling to even imagine what a queer relationship could even look like, it must be pretty overwhelming to finally enter one.

However, Bhargava paints a much different picture pertaining to gay men in relationships: “Men very much operate in a sexual marketplace, not an emotional marketplace,” they said. “So like, it’s really hard to navigate when you want to be sexual with someone and when you want to be emotional with them. And when you want to be both — it’s even scarier.”

Bhargava added that age-gap relationships, which are widely believed to be overrepresented in queer spaces, may be a result of repression.

“Age is more arbitrary in queer spaces because you might be 20 years older, but I might be five years more mature in my sexuality, because I’ve been out of the closet for, like, a much longer time than you,” they said.

Dynamics like age and gender can present an interesting undertone for queer relationships. Persell describes the power in lesbian relationships, which are usually exclusive to non-men.

“Straight people, theoretically, are on this even playing field, but there’s still this inherent gender power dynamic that exists,” they said. “Versus, for lesbians, we don’t really have that … there’s no patriarchy there.”

Furthermore, the concept of queer love should undoubtedly include the experience of trans community members. And while a lot of these concepts can apply to this historically marginalized group, trans people face additional pressures in their dating ventures. Díaz, who identifies as a trans woman, said

that her earliest experiences looking for love were contextualized in the pressures from cis-het people. She felt like dating men validated her womanhood in a time when she was feeling lost.

“Now I know that I can be selective with who I choose to be with and I should be able to expect to receive a certain treatment and a certain quality of affection,” she said. “I don’t want to make those compromises. I’ve had to almost hide my identity, make it smaller, to appease other people’s insecurities of dating me.”

Díaz identifies as queer both in terms of her sexuality and her gender, which has complicated her desire to display love like her cis-het counterparts. Even in somewhere as liberal as Los Angeles, she still feels some pressure to hide her queerness, especially in relationships: “It kind of puts a barrier between actually doing things the right way and communicating — it separates people.”

Díaz isn’t alone in this feeling. Persell and Bhargaava both touched on the lack of structure in their past relationships.

“I think all relationships are confusing,” Persell said. “[Queer relationships] can be slightly more confusing because there’s no script to double check. There’s no timeline to double check with. Again, there’s no boxes to fulfill.”

Despite these challenges, much like famed singer and billionaire Rihanna, queer people have been able to find love in a hopeless place. Díaz, who just celebrated her three year “Tranniversary” in April, has found meaningful and healthy romantic connections. Bhargava, with their complicated relationships and nuanced view on love, makes powerful connections with other queer people without the expectations put on straight relationships. And Persell will continue to explore queer relationships that exist outside the rules made by straight people.

Queer people have, and always will, find relationships, feel connections and love outside of the boxes prescribed by Uncle Jerry.

So, maybe Queer love is love — it’s just a little queer.

“I don’t want to make those compromises. I’ve had to almost hide my identity, make it smaller, to appease other people’s insecurities of dating me.”

IS QUEER LOEV QUEER?

IS QUEER LOEV QUEER?

what is love?

it’s watching others create art, and being inspired. i mean seeing something so beautiful your spirit has to move. has to create, has to pay homage to the bravery it took for them to put that into the world.

DESIGNED BY KATHRYN AURELIO + ANNA FANG

DESIGNED BY KATHRYN AURELIO + ANNA FANG

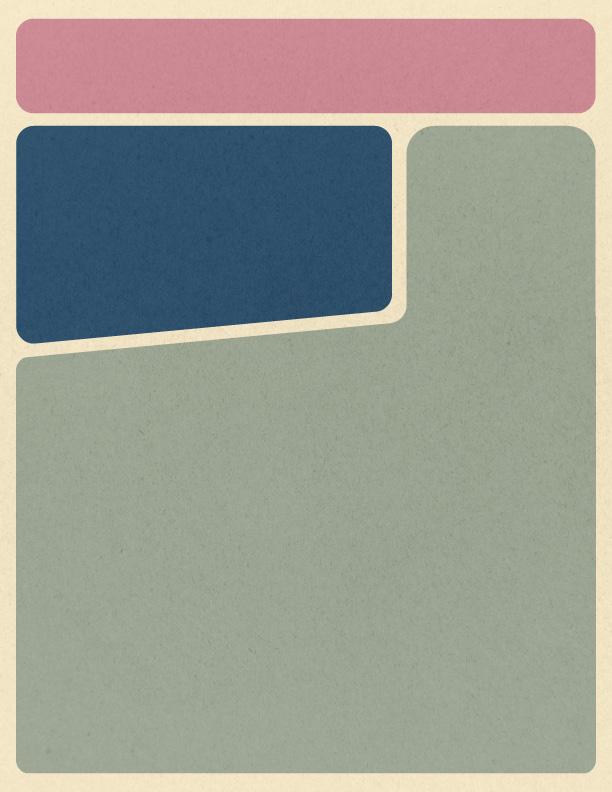

This story features interactive audio components. To follow along, scan the QR code and listen to the corresponding audio. Each star symbol ( ) indicates when to listen to the next component, but the audio guide will queue you in as well.

– Begin playing audio:

Jorge: You know what, I forgot to tell you: It’s been a whole year since we first met… on July 10, 2019. I was looking at pictures and I just, like, remembered.

I received this voice message via Instagram Direct Messenger on Friday, July 10, 2020. I suppose that’s a given — one year after July 10, 2019. It was from Jorge, my international inamorato.

I met Jorge at a hostel in northern Israel during my travels with a Jewish youth group that summer. He was visiting the middle eastern country from Colombia with his high school. What started as a casual dalliance turned into a romantic encounter that I’ll remember for the rest of my life: Late nights spent awkwardly flirting, telling each other about our hometowns, me sneaking him past my trip staff into my room, him making fun of me for wearing sunglasses at night. I felt like I was living in an André Aciman novel, or Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise.

When I got home from Israel, all I could think about was Jorge, how I wished I had more time with him. I knew it was unlikely I’d ever see him again. I doubted we would even stay in touch. That summer, I was confident I had heard his voice for the last time.

Voice messages proved me wrong.

Instagram debuted its voice messaging feature in December 2018, just seven months before Jorge entered my life. He was the first person to send me a voice message on the platform.

Similar voice features had been available on Apple’s iMessage since June 2014 and on WhatsApp since August 2013. But I had never made much use of them. I was raised in the age of texting; my thumbs moved faster than my lips.

When Jorge first started sending me voice messages, it felt novel. Hearing his voice out loud in a private chat took me by surprise. It was almost as if we had a pair of long-distance walkie-talkies, unaffected by the 1,137 miles between Barranquilla, Colombia, and my hometown in Florida. But these special walkie-talkies had a “repeat” button. I could listen to Jorge telling me he remembered the exact date we met. Then I could repeat the message, repeat it three more times, fall back on my bed and nearly swoon — all before responding with my own voice message. Do you copy?

Jorge: Okay, so, I looked down to see your text. And then, uh, there was this guy, um, like, literally in front of my car. And [car honking, laughing] I almost crashed him because of seeing your text. And sh*t I’m driving, um, f*ck.

If I had sent Jorge a voice message instead of a text, perhaps he would not have been distracted by trying to read something while driving. This would be the obvious takeaway from his voice message. And, yeah, he probably could have done without sending me this message until he got to wherever he was going in his car.

But there’s something else — something special — worth noting about this voice message. The moment didn’t warrant a phone call, but Jorge’s story was certainly brought to life more hilariously in his voice than it could have been in a brief text message. I am tired of reading a robotic “lol” or pointlessly onomatopoetic “hahaha.” Hearing Jorge’s laugh is so much better.

This moment was one of alarm, of unpredictability. Jorge was able to pick up his phone and tell me about his startling experience right away. I heard his unedited, unfiltered, expletive-filled response to a real-time situation. It was chaotic. It was troublesome. It was real. Voice messages allow us to witness innately human moments like this.

Content Warning: Things are about to get dirty, Carrie Bradshaw style (who, by the way, would totally love voice messages).

Michael Pincus: You’re so sexy when you talk like that. But now you gotta, you know, ‘walk the walk’ with that. Come see me, you know.

There’s intimacy in a voice message. Jorge could send me voice messages in his deep voice saying things that elicited only the most fitting response from me: a voice message telling him that he was sexy, out loud.

There’s nothing spontaneous or sexy about a text message. Inversely, phone calls can feel too spontaneous, and they can get messy, really fast. Voice messages create a perfect middle ground. I could make sure that what

I had said out loud was what I wanted Jorge to hear on his end. But unlike text messages, which I could edit and rewrite to my heart’s desire, I would have to record an entirely new voice message if I didn’t like what I said or how I sounded. This forced me to leave a level of improvisation in the final cut.

Speaking from a comfortable level of impulse through voice messages doesn’t just benefit the more seductive talk. I grew up averse to phone calls; they feel too confrontational. Voice messages are an asynchronous alternative. They are a way to speak from the heart without having to deal with the anxiety of an immediate reaction on the other end. Inspired by my communication with Jorge, I now use voice messages regularly in my personal life to tell people how I really feel without over-sanitizing my thoughts.

Jorge: Just wanted to say, like, thank you for what you said, and have a good night. Although you’re probably already asleep.

Like most people, I live on the go. Voice messages allow me to have continuous out-loud conversations throughout extended periods of time without having to stay on the phone. I could resume the conversation at my convenience without sacrificing the enrichment that comes with actually hearing someone’s voice.

Jorge was right in that message. I was already asleep. But that did not stop him from being able to say what he wanted to say to me at that exact moment. He did not have to wait until the morning for me to be available to call. When I awoke, I was able to start recording and resume the conversation.

Michael Pincus: Oh my gosh, no, you’re not bothering me at all. I’m always happy to listen and honestly it’s really great that you messaged me ‘cause we haven’t talked in a while, and we used to talk all the time. So it’s always great to catch up, especially, you know, these days when everything feels so disconnected.

Leading up to this message, Jorge had reached out to me after we had fallen out of touch for a little while. He told me about some challenges he was facing at his university. Then, he became worried that he was annoying me with his ranting. I picked up my phone and assured him I was happy to hear from him. It was the height of COVID-19 lockdowns. I was lonely.

Trying to convince someone you feel a certain way over text is daunting. It’s so easy for your tone to be lost. Speaking out loud ensures your words can be heard in their fullest sincerity. Jorge did

not have to question the authenticity of my response.

Think about it: How many times have you missed someone’s sarcasm in a text message? How many times have you stared at an “lol” at the end of a paragraph, wondering whether it was a passive-aggressive insertion or simply a force of habit?

Voice messages clear this fog. There are no lines to read between. Just sound waves to listen to.

Jorge: Um, also, I think you’ve made me realize how much I use voice messages as well. Um, but I think that’s a — it’s a thing in Colombia, in general. ‘Cause, you know, we communicate through WhatsApp mostly. And I feel like — in WhatsApp, since you can record without it being interrupted by a time limit, like, I send like, I don’t know, sevenminute voice messages to my friends sometimes, you know? So, yeah. If that’s interesting for your research. [laughing]

When I reached out to Jorge for permission to use our voice messages in this story, he taught me about how commonplace they are in Colombia. WhatsApp is especially popular in Latin America as it is a cheaper alternative to SMS messaging in countries where the latter is expensive. As I mentioned earlier, WhatsApp integrated voice messaging into its platform way back in 2013. So people in Colombia have been on board with voice messages for a while.

It’s no wonder then that I learned the sanctity of voice messages from a Colombian. I’m indebted to Jorge for that.

Voice messages are my new love language. They’ve allowed me to connect with Jorge across thousands of miles, hearing his whispers, the cadence of his voice, the natural sound in his background, his laughter. And now, thanks to voice messages, Jorge and I have plans to see each other this summer in Western Europe (it’s funny how we’re meeting far away from both of our homes again, isn’t it?).

There’s an unparalleled combination of expressiveness, authenticity and convenience found in this modern communication vessel. You can pick up your phone and listen to a loved one’s voice like it’s music or your favorite podcast. You can return to it a thousand times over. And you can gift the other person with the same. It’s time we return to speaking with our voices.

I want to hear you, loud and clear.

the end...

end...

“I want to hear you, loud and clear”

TOO CLOSE,

TOO MUCH

Written by Andrea Arcia

Photographed by Cole Sun

My most intense relationships have been no relationships at all. They’ve been entanglements that were anything but defined — not spoken into existence but flared into being. At their heights, they’ve meant screaming matches outside of parties filled with beer-soaked strangers and terrible house music. Crying on the front porch of an unknown home as a kind stranger walks up and asks, “What’d he do?” Asking questions I didn’t have the right to ask. Receiving answers I never actually wanted. And at their ends, they’ve meant getting home from a “friend’s” (that’s what we were, after all) a little tipsy but plenty broken, and falling into my roommates’ arms for consolation. These non-relationships — situationships, if you will — have broken me down more than any real relationship ever has, lighting me on fire moments before forcing me to drown. But after all was said and done, they’ve also talked the most sense into me, giving me the chance to reevaluate who I was and sew myself back together on my own terms. I’d ask, what was wrong with me that I allowed myself to be burned alive, succumb to the flames and keep going back for more? I used to think the answer was love: The waves of intensity, the back and forth, the fiery passion, the chase. But that isn’t love. It couldn’t be further from it. What I had been experiencing was not love at all, but an overwhelming absence of it — principally brought on by the lack of love I had for myself.

As the story goes, when young Icarus was given wings, carefully crafted by his father to make their grand escape from an intricate labyrinth, he was offered a warning. He was not to fly too close to the sun, as its heat would melt the wax on his wings and cause him to plummet. Neither was he to fly too close to the sea, as his wings would soak up moisture, and the waves would swallow him whole. His father was very clear on what not to do. And yet, leaping over the Aegean Sea, he took one look at the sun and tossed everything to the side. Despite knowing what it would do to him, Icarus flew closer and closer to the sun — the object of his desire. He became so overwhelmed by the feeling of flight that he was convinced he finally understood how it felt to be a god. But his newfound divinity was short-lived, as his wings began to burn, causing him to fall at the height of his ecstasy. From afar, his father could do nothing but watch as Icarus plunged into the sea, dying upon impact as the sun blazed from above.

Like a game of telephone, several versions of this myth have

96

“I loved you as Icarus loved the sun. Too close, too much.” - David Jones

Tammi Sison ‘25 is a communication major from Brentwood, CA. She’s really good at ping pong.

Tammi Sison ‘25 is a communication major from Brentwood, CA. She’s really good at ping pong.

transpired over the centuries — each serving as its own cautionary tale. For some, the downfall of Icarus is interpreted as a warning sign to listen to our elders. For others — us lovers and hopeless romantics — the story of Icarus is a tale of failed love, a tale of renouncing it all in the pursuit of that special person with whom you are infatuated, someone we hope is worth the pain. And while one might argue that such love is aspirational — that we are on this earth to love as unconditionally and relentlessly as Icarus — that would be a complete misunderstanding of what it means to love and be loved. But at the height of our youth, how are we expected to know any better?

It’s easy to paint Icarus as a fool. Though, aren’t we all? Icarus was careless, illogical and overconfident — now known as the boy who flew too close to the sun and got what he deserved. But as much grief as we might give him, more of us are like Icarus than we care to admit. We too are warned about heartbreak our entire lives. Whether it be by friends who have loved and lost, by movies that capture a less idyllic version of love by embracing its complexities (La La Land, anyone?), or by breakup songs that we don’t seem to fully understand until it is much too late (“Somebody That I Used to Know” particularly tears me apart). But still, we don’t seem to listen when the person we’re “talking” to says they aren’t ready for a relationship. Or we miss the memo when our “more than friends but less than lovers” keeps us around for comfort, but rejects any sort of labels that come with the benefits. Like Icarus, we should know better than to want someone we can’t (and

shouldn’t) have, but none of that matters once we are taken by a feeling that resembles love. Whether or not we truly know what love is, is beside the point. At this age, thinking we are in love is enough, and in some cases, the thought alone is enough to go up in flames.

Nothing is clear cut in college — where we’re going, which jobs might stick or where we’re truly meant to be. It’s a stage in our lives where we need love more than ever, and yet, matters of the heart are even harder to navigate. There is no guide on how we should love or accept love, a sensation that negates logic and reasoning almost completely. But even if no human on earth may be able to put love appropriately into words (such a thing can never be absolutely defined, much less by a university junior) I can surely tell you what love is not.

Love isn’t compromising yourself at the expense of someone else. It isn’t listening to what someone wants from you, over what you need for yourself. It isn’t letting someone overstep your boundaries time and time again because you would rather tolerate their disrespect than lose them altogether. Love isn’t supposed to be obsessive, it isn’t supposed to be a chase, and it certainly isn’t supposed to be hot and cold. When you’re playing games, the rush that arises is addicting. The “not knowing” is a drug that draws you into never-ending cycles, craving the highs after so many lows — but lust is not to be confused for love. Entering the next chapter of our adulthood, it’s time to abandon the games we play and acknowledge when we are the ones standing in our own way.

99

In the moments I’ve encountered true, authentic love, it’s not been unpredictable, agonizing chaos. It’s been peace. A place to come home. I’ve felt it in the arms of my roommate, reassuring me all will be okay. In the gentle stranger that found it in her heart to comfort me before even knowing my name. In nights filled with friends, intimate conversation and glasses of rosé — but most importantly, in the strength and compassion I’ve shown myself when I “know better” but continue making mistakes. My encounters with genuine love have been enough to set the standard — enough that I know I’d rather wait for the real thing than continue chasing fantasies, and that I’ve quit searching for potential in others and started acting on my own. Only once we realize there is nothing someone else can give us that we can’t give ourselves do the relationships we tolerate become pure. Replenishing. It is a love that scarcely arrives when we recognize that in any relationship of two, no one is supposed to be Icarus, so both can feel like the sun.

TOO CLOSE, TOO MUCH

TOO CLOSE, TOO MUCH

what is love?

love is what connects me to you connects you to yourself. to god, to your creator, to your creations to creation…itself.

what is love?

love is the universal language the...universe’s language.

scan to watch the full video

Special thank you to...

(On left) Lorenzo Hinojosa ‘24 is a media arts and practice major from Santa Clarita, CA. He hosts a radio show.

USC Men’s Mental Health Initiative @uscmmhi Brothers Breaking B.R.E.A.D. @uscbbb

(On left) Lorenzo Hinojosa ‘24 is a media arts and practice major from Santa Clarita, CA. He hosts a radio show.

USC Men’s Mental Health Initiative @uscmmhi Brothers Breaking B.R.E.A.D. @uscbbb

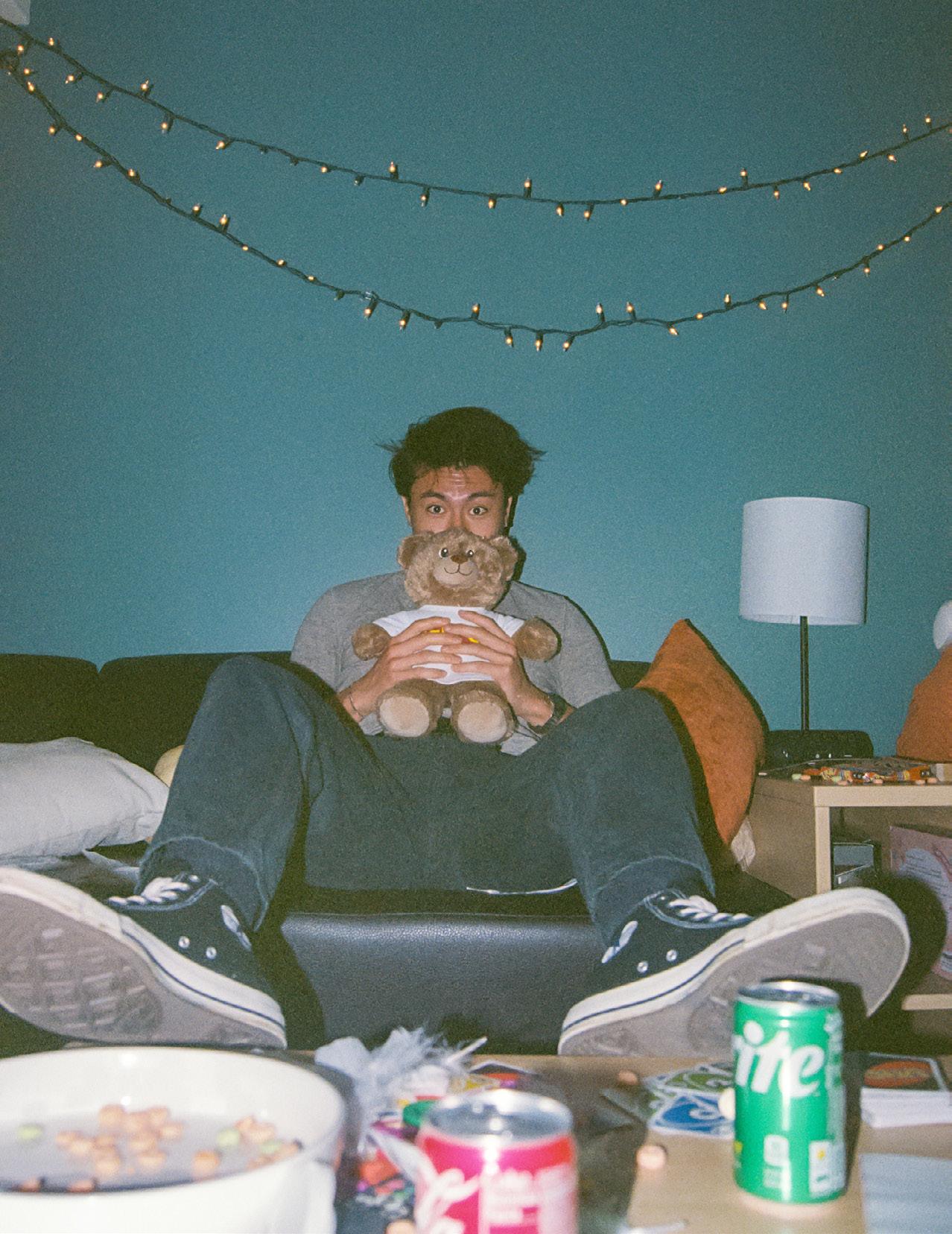

The best part of a night out is the morning after, when we gather around and discuss every last detail of the night before. If your crush finally asks for your number, the group chat is the first to know. But is it the same for guys? Do they frantically FaceTime their friends when a Snapchat notification from that person pops up? Are they sitting around with ice cream and listening to SZA when someone is going through a break up?

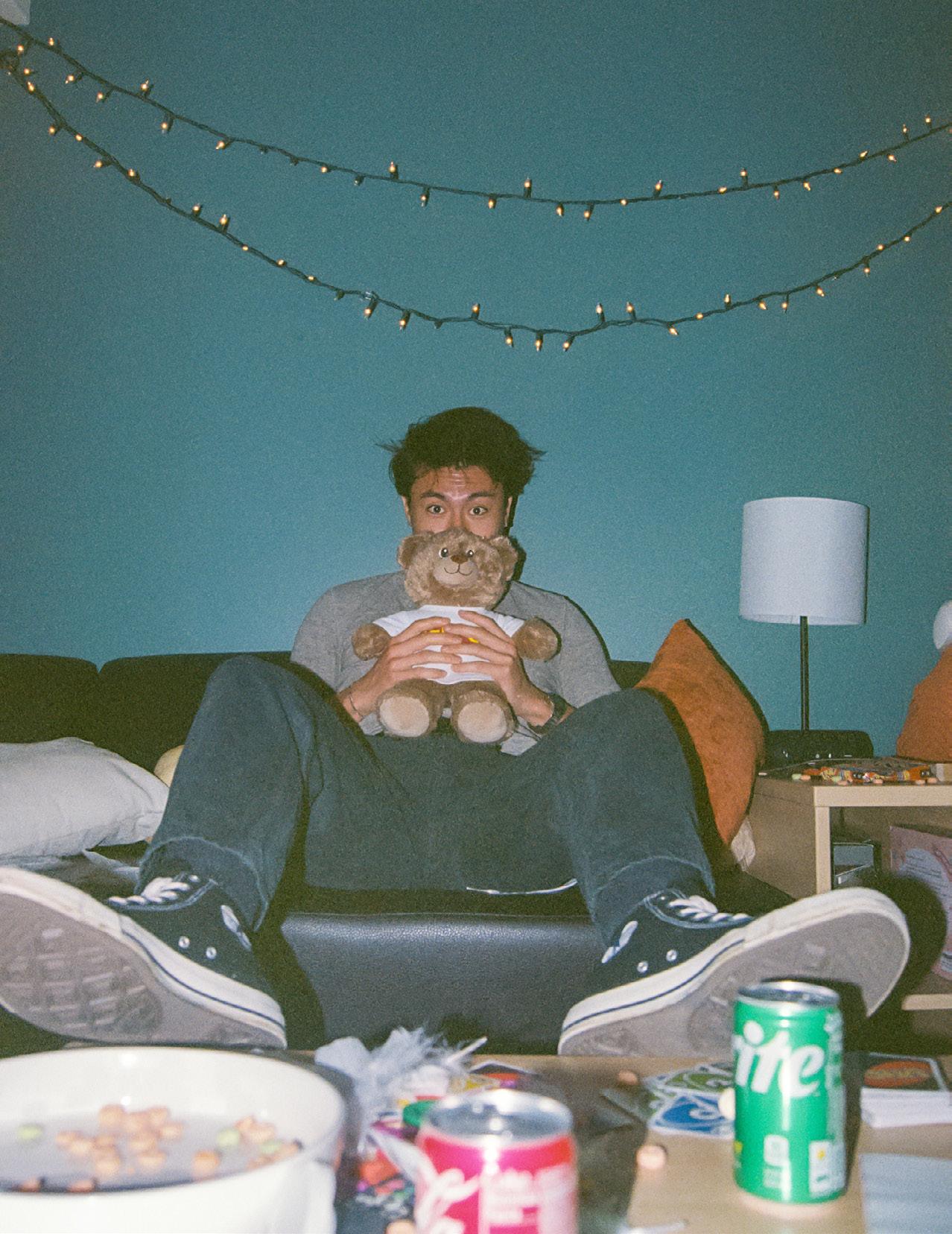

Sam Stack, a sophomore communication major from Dayton, Ohio is the founder and president of the USC Men’s Mental Health Initiative. He said that for him, playing late night video games with his fraternity brothers are the best times to open up to his friends, finding that one question can lead to an entire discussion they didn’t expect to have.

“It just takes one person to lead or ask a question. From there, it organically happens,” said Stack. “You’d be surprised about how many people open up about their feelings without even knowing it. They’ll just go on rants or tangents as long as someone’s there to listen.”

So, I decided to listen. I talked to four straight male students and asked them to explore their experiences with relationships, love and masculinity. Each guy has a different story and perspective, highlighting the fact that there is not one, right way to be a man — despite what society may say.

Here’s what they said:

112

For most girls, we’re intimately familiar with the idea of “girl talk.”

familiar

113

Vincent Demonte, a sophomore journalism major and comedy minor from Fullerton, California, ran into a girl at a birthday party. They hit it off, and he got her Snapchat. Later, he ran into her at the gym. This was Demonte’s chance, all he had to do was ask her out. But that familiar voice in his head made him stay anxiously silent.

“I am so scared sh*tless of asking someone out, like I physically can-

not bring myself to do it. I almost have an anxiety attack every time I’m about to do it,” said Demonte.

For Demonte, despite his “mental block” to approach women, talking about his feelings comes naturally. He credits his father for teaching him what it means to be a man and how to be comfortable with his emotions.

“He’s definitely no stranger to sharing his emotions. He’s the type

114

of person who cries during a Pixar movie every time. I mean, me too,” Demonte added, but he recognizes that sometimes he fluctuates.

Recounting an experience reporting during the Los Angeles mayoral election, where he was so stressed out that he broke down in his friend’s arms, Demonte said it was a pivotal moment when he realized he cannot bottle up his emotions and that it’s important to have

an outlet.

“I had my friends come over… and it somehow transitioned into me spilling my guts about everything I’ve been feeling and then just kind of hugging them for 30 minutes,” said Demonte. “I just sobbed… and I think that was a sign that maybe I should talk to someone.”

Charlie Arnold, a freshman swimmer majoring in business administration from Bellevue, Washington,

115

emphasized the importance of having someone to talk to with his description of the ideal relationship.

“It’s like having a best friend that you can talk to about everything. Someone to lean on. Someone to have fun with. You’re super open with the person, not embarrassed by anything [and] not afraid,” said Arnold.