Oh, MAN!

SCENE’S MEN OF THE SEMESTER

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF | Julia Zara

Issue No. 6 | Fall 2024

CO-CREATIVE DIRECTOR | Kassydi Rone

CO-CREATIVE DIRECTOR | Asha Oommen

DIRECTOR OF FUNDRAISING, EVENTS AND PUBLIC RELATIONS | Kayla Rocha

DIRECTOR OF SOCIAL MEDIA AND PUBLIC RELATIONS | Jazmyne Aquino

DIRECTOR OF WRITING | Andrea Arcia

DIRECTOR OF COPY | Sullivan Barthel

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY | Pili Marco

DIRECTOR OF DESIGN | Kathryn Aurelio

DIRECTOR OF MULTIMEDIA | Kayla Li

ASSISTANT EDITOR-IN-CHIEF | Solana Espino

ASSISTANT EDITOR-IN-CHIEF | Kayden-Harmony Greenstein

ASSISTANT CREATIVE DIRECTOR | Olivia Hau

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF WRITING | David Sosa

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF COPY | Sammie Yen

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF DESIGN | Carlee Nixon

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF MULTIMEDIA | Katherine Harry

WRITING

Kailee Bryant

Laurie Carrillo

Alexis Lara

Benjamin Turnquest

PHOTOGRAPHY

Anya Barrus

Megan Chan

Thomas Pham

DESIGN

Sesame Gaetsaloe

Lakshmi Sajith

MULTIMEDIA

Mia Gabrielle Juni

Evan Estevez Rodrigues

Miranda Seham

FUNDRAISING + PR

Yvonne Abedi

Sruthi Singamsetty

Ashleigh Azarraga

GUEST CONTRIBUTORS

Luqman Abdi

Christin Albertus

Izzy Ster

TALENT + CREW

Rafael Andrade

Chris Araujo

Thaddeus Bernard

Christian Bipat

Adam Bloodgood

Liv Bohler

Zoey Boyd

Chris Chun

Patrick Corbin

John (JD) Davillier

Andy Eun

Shaudeh Farjami

Ethan Fayne

Morgan Fierro

Shamoli Ghosh

Anthony Guan

Nicholas Hanson

Ethan Holder

Andrew Huang

Martina Ibrichimova

Thomazin Jury

Jace Kang

Paige Kaufman

Joseph Kim

Mary Kate Lunt

Ari Rose-Marquez

Daevenmar Mendoza

Kenny Nguyen

Ryan Oh

Keaton Orava

Zach Patel

Julian Patino

Rena Pau

Landon Robinson

Campbelle Searcy

Parth Suri

Benjamin Thai

Nicole Tisnes

Ayonnah Tinsley

Phillip Tran

Dr. Alison Trope

Dominique Valles

Liam Wady

Niki Wright

Sullivan

SCene

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Ivividly remember where it all started. I had just been rejected from another on-campus publication. The email was open on my dimly lit laptop: “We regret to inform you...”

I remember the taste of my disappointment. It was sharp and sour, like the remnants of black coffee. It stayed plastered to the roof of my mouth, and even a swivel of water couldn’t wash away the harshness.

Luckily, I was determined to cleanse my palette. The email was promptly deleted, and the straps of my leather journal were unbound: On September 10, 2021, I scribbled: “The Idea.” Who knew I’d be writing my fate into existence?

I can see it even now: Making the trek from Pardee Tower room 201 to room 215, knocking on the door of my new friends, Kassydi and Asha, seeing the door open wide as Anna and Via sat on the gray carpeted floor. I see them in my mind’s eye, their gears turning as I pitched them “The Idea,” listing off names for a multimedia magazine — one that we could start together, if they were up for it. And they were. We determined that the winner among the list was clear: SCene.

SCene Magazine was born out of the pure refusal to let rejection dictate the future. Looking back, I don’t feel the bitterness anymore. A writer wants to publish voice memos from his international exlover? Let’s do it. A photographer wants to storytell at a queer line-

dancing nightclub? We’re game. A filmmaker wants to produce a short film with a talking fish? Say less.

SCene has, and will continue to be, the junction where idea meets possibility. In true start-up fashion, this magazine is scrappy, and our team will always push the boundaries of storytelling as far as we can take it. From themes of womanhood, to entertainment, to love, to nightlife to existentialism, to now, manhood, SCene has produced six wonderful issues thus far, with each offering something new and exciting to the world. For the past three years, SCene’s leaders have always approached this magazine with an openness to fresh new perspectives and vulnerable musings, and our hope is that readers will do that, too.

So, within the context of a magazine built up by women, we deemed it fitting to delve into something completely unprecedented: Man. It’s not the antithesis of our work here. In fact, it’s what SCene was born out of in the first place: A challenge. And what would SCene be if not pulsating with a little competitive edge?

This is my last semester with SCene. I graduate this semester, and as my fingers grace the embroidered SCene logo on my graduation sash, I’m content. These threads will tie me steadfast to you.

To my final SCene team, thank you for constantly delivering. Even after all these years, you never

cease to innovate and excel. To my successors, Solana and Kayden, thank you for stepping up to the plate. Being a leader is not easy, but I know you will both do your duty with responsibility, care, creativity and most importantly, love. I entrust “The Idea” to you.

To those who have contributed to and supported SCene since the beginning, thank you for never wavering in your commitment to our mission. Your voices dictate the course of our organization: We hear you, and we won’t stop listening.

To my family and friends, thank you for giving me the space to try. These past three years have been a wild ride, one fraught with challenges and lessons learned. You constantly hold up a mirror to myself and this organization, and it’s only through your honesty and guidance that I’m able to see myself and SCene for what we are. It’s because of you that I love the woman and the organization staring back at me.

Yes, I vividly remember where it all started, but I honestly don’t think I’ll remember where it ended. Because, SCene will live on.

And I can’t wait to see what happens next. Good luck, and farewell.

LETTER FROM THE CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Oh, man. A simple phrase. Yet, it’s an interjection that commands a room: We hear it. We stop what we’re doing. And we turn our attention towards the source. This semester, the best way to grasp this theme is by asking you to take those very same steps.

As creatives, sources are a two-way street. On one end, we have the source subjects — in this particular case, men — who are central to the stories that unfold just beyond these letters. But on the other end, there are the source vessels, there’s us. The SCene team who conceptualizes, curates and creates with the goal of fostering community. This interplay of perspectives is what breathes into our otherwise inanimate publication. It’s what makes your stories come alive.

We know that for a team that has been spearheaded by women since its inception, dedicating an issue to men may feel like it’s venturing into uncharted territory. We know that for a country that’s been spearheaded by men since its inception, dedicating an issue to men may feel like it’s venturing into unwanted territory. So now, more than ever, we need you to trust us. To turn your attention towards both source ends.

Let’s be clear: Issue No. 6 is not about handing men a megaphone. Issue No. 6 is about sharing a microphone. We are inviting men into a conversation that cracks the surface, diving

into the complexity of what it means to present male-dominated media in a way that feels fresh, meaningful, and dare we say — hopeful.

What better way to pay homage to Issue No. 1, “She’s All That… Or Is She?” than with a full circle closure that turns the lens the opposite direction? To ask ourselves, what is it about men that keeps us watching, debating and wondering? Is it their ever-present spotlight in popular culture? Their ability to toe the line between aspirational figures and laughable tropes? Or is it simply the act that keeping tabs on them feels, well, fascinating?

Whether they’re the object of adoration, critique or confusion, understanding the way men influence the spaces they inhabit is crucial. We are not here to glorify or vilify, but to explore.

Oh, man. A simple phrase. Yet, these are our parting words to a publication and a group of incredibly creative humans that have shaped our college career: We hear you. We won’t stop what we’re doing. We promise you — we will continue to interject, to make space to amplify stories that are so deserving of being told. Thank you for listening. And thanks to you, there will always be another SCene to set.

Alright, go ahead. Don’t keep our Men of the Semester waiting. As you turn the page, we will move to the next chapter, forever grateful for six issues that will remain written in our hearts.

WHAT DO WE GAIN FROM GAINS? POWERLIFTERS

Round, perky muscles that would make Michelangelo blush. Stretch marks on the brink of tearing at the seams. Sweat drops so salty they could be collected and used for saltine crackers. If it weren’t for the machines clinking and clanking, the aroma would surely give away the sanctity of the gym.

Whether it’s close to the dead of night or the crack of dawn, there will be men, at varying stages of their own measured progress, using the machines at any given gym nearby. For the boys of the Trojan Barbell Club (TBC) at USC — many of whom started working out within the past three years — the personal benefits of their gains are shaped by reconstructing their ideas of the ideal male body.

Since the pandemic, gym culture skyrocketed to the top financial priorities for Gen Z according to The Washington Post, with their newfound spending priority consisting of gym memberships and personal trainers. While some rotted in their rooms during COVID-19 waiting for a way out of the monotonous days, fitness became an outlet for the goal-oriented. The lost sought a substitute for staring at a screen all day.

Kenny Nguyen, now a USC senior majoring in computer science, was graduating high school in Minnesota and wanted to change going into his first year at USC. “I just didn’t like being skinny anymore,” he tells me as weights all around us fall to the ground of the Lyon Recreation Center. We’re downstairs in the pit, where he works out with the TBC during one of their weekday meetings. They’re prepping for a competition they have in two weeks. Despite all the food Kenny has eaten in this short amount of time, he has an ease about him, which comes through in his prayer-like position during our talk.

“It sounds really bad, but I am force-feeding

myself to really try, and it sounds bad — it’s not that bad,” Kenny reassures me, before I could show any sign of concern. “I’m just eating more than I normally would because I want to gain weight. But, in the beginning, when you first go to the gym, you don’t like the gym stereotype.”

Indeed, before he reached his current level of strength, Kenny faced some difficulty devoting himself to powerlifting. Prior to joining the club and getting a coach, his entry point to the culture was through watching YouTube videos of influencers like David Laid, whose own fitness journey began in 2013, when he started to track his bodybuilding transformation at 14 years old.

Although he started working out earlier than Kenny, fellow TBC member Julian Patino, a sophomore majoring in industrial and systems engineering, was also inspired by the examples of others. Growing up in Miami, he imagined an Arnold Schwarzenegger-type build — huge muscles and super lean — as the ideal physique for a man. But, by the time he started going to his local gym, where several men who competed in powerlifting competitions on national and international levels happened to frequent, he recalibrated his expectations. One of those men became a mentor.

“His name is Javi, and he was one of the people who competed internationally for Puerto Rico. He was actually my gym receptionist, and he was the guy who actually put me on lifting in general. And then after I was looking into it for about a year and a half, he put me onto powerlifting,” Julian says, now a teacher in his own right, helping people get started on working out.

Looking past the machines and to a nearby wall, Kenny takes a moment to consider whether or not people viewed him differently now than before.

“I’m not as insecure because I’ve gained weight, and I’m where I want to be. So, I might just walk around with more confidence, and I talk with more confidence or whatever,” he says (with confidence), “[but] if you go to the gym, and you look relatively healthy and fit … I think people tend to respond to that. And I don’t want to say they treat you vastly differently. But, I think there is a slight difference, especially guy-to-guy. Just a certain level of respect. Not in a cringe way, I hope.”

Around the same time that Gen Z began flocking to the gym, influencers on TikTok and other platforms garnered a fast-growing audience that shaped the “manosphere.” Similar to terms like “incel,” the manosphere is a phrase that has floated online since the 2000s, referring to internet subcultures where men express anti-feminist, misogynist and violent viewpoints, according to the Anti-Defamation League.

There are different corners of the manosphere that vary in toxicity, ranging from everyday influencers at your local L.A. Fitness to Andrew Tate. Many of these figures are connected by the high regard they hold for fitness. To some, the term “gym bro” might come to mind when discussing the wider manosphere.

To Kenny, the male-identifying members of the TBC are a stark contrast to direct or indirect followers of the manosphere.

“When I hear ‘gym bro,’ I just think [it’s] way more talk than actual experience. Because, if you talk to any of these guys who’ve been going to the gym for a while, they’re the most humble, nice, kind, weird, f*cking weird people,” he says. “But if you talk to a ‘gym bro,’ in my head, I’m thinking like, ‘Dude.’”

Julian has a similar idea of a gym bro, failing to keep a smile back when I ask how he would define one.

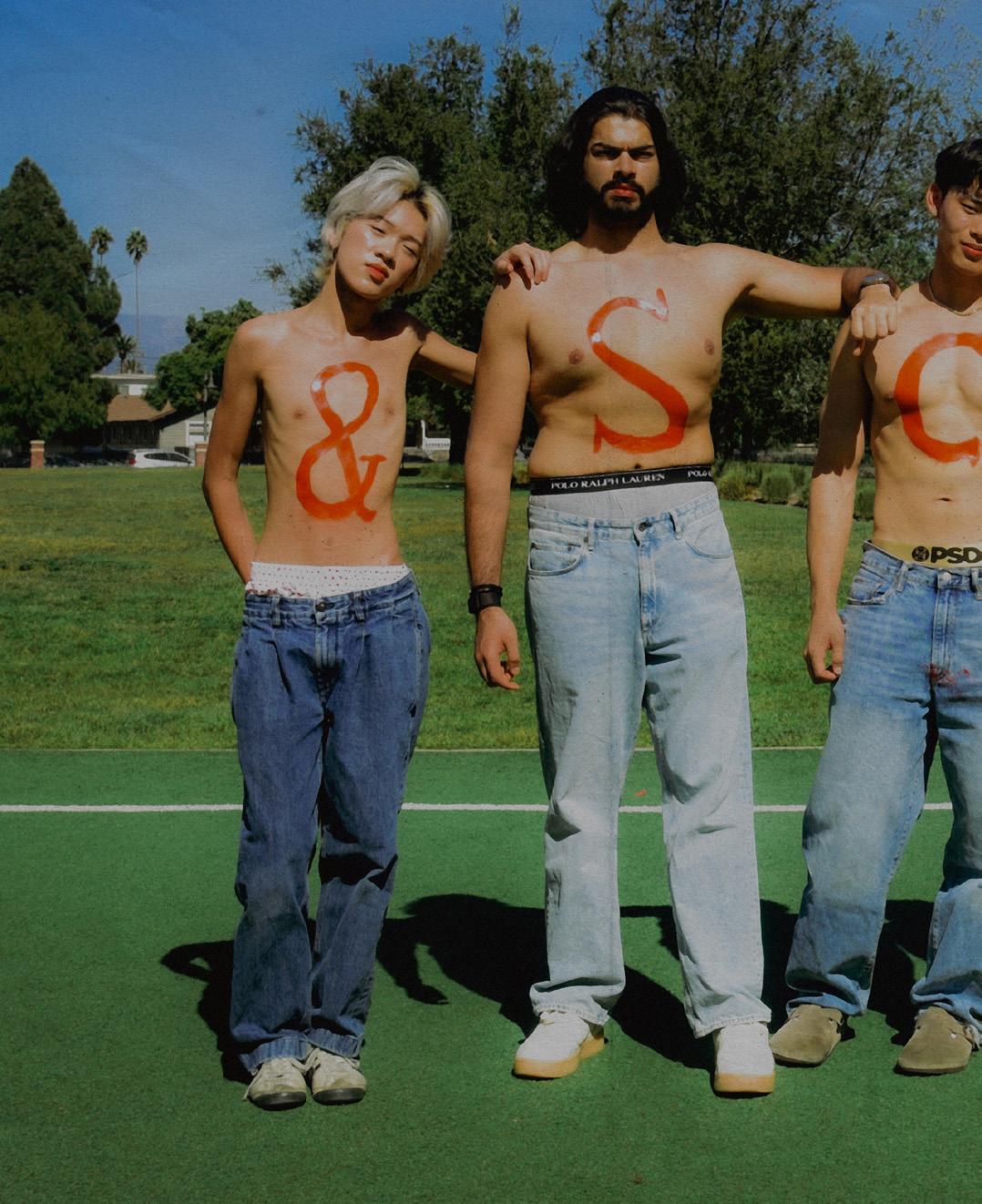

Model Chris Araujo ‘25 is a business administration major from Hinsdale, IL. He once ranked 7th in the U.S. in Clash of Clans and 81st in the world in Madden.

Model Jace Kang ‘25 (bottom left) is a cognitive science major from Seoul, South Korea. He likes pineapple on pizza.

“A gym bro is more of the really young high schoolers who just show up to the gym, and they do the most extreme,” Julian says. “So, for example, when it comes to pre-workout, they’ll take over the [recommended] dosage. And it would just be those curly heads, sweatpants, tank top guys…They just go to the gym, and then they’ll be in packs, and then they’ll just be screaming out all their sets.”

As others my age found solace in the gym during and after the pandemic’s peak, I was upsetting my doctor by losing too much weight. Although I always skewed on the slim side, the pandemic marked a new low for me, with my body mass index plummeting far too close to underweight. Needless to say, I was punching below my weight, literally and figuratively.

However, in my head, I never felt as though I was dangerously close to being underweight. If anything, the parts of my body that stood out for all the wrong reasons were sights of slight rolls that popped out in specific positions. Even worse, the uncertainty of how others perceived me, from my body to my personality, became a frequent concern towards the end of high school. In hindsight, that battle was entirely internal and founded upon the assumption that everyone had the same perception of me as myself.

“If you’re less than 200 pounds, you’re going to get clowned no matter what. It doesn’t really matter how big you get,” Kenny confesses, weighing the differences between male and female body standards. “I think in general, girls are very accepting of each other. And guys, as soon as they see someone who’s really big or something, they immediately just want to get that big themselves. They’re less okay with where they’re at for the most part.”

Before talking to Kenny and Julian, I walked inside Lyon for the first time. Even though I would not consider myself an insecure person, I unfairly weighed myself against others’ fitness without taking into account their own hills and valleys.

With respect to their individual journeys, the TBC men have been through similar stages of self-doubt and struggle with body image. Due to a condition Julian had when he was younger, where rashes and itchiness would break out around his body, he largely neglected fitness growing up. A trip to the doctor revealed to Julian that “the only way that I can really get through it is to really push through it. So, the only way that I was able to fight, I guess, was to fight through it.” Through consistency and discipline, he learned to compete with himself rather than compare himself to other men.

“One of the things that’s really underappreciated when it comes to working out is just getting yourself in the gym,” Julian says. “And I guess, well, for a lot of people, it takes a lot to put themselves in an environment they’re uncomfortable in. Especially in a gym environment where everyone’s going to be 30 times ahead of you in the gym because they’ve been doing it consistently.”

Model Dom Valles ‘25 is an astronautical engineering major from Atlanta, GA. He loves fighting.

Writer David Sosa ‘26 is from northeast Los Angeles and studies journalism. He primarily reviews music, ranging from up-and-coming artists to live shows around L.A.

Despite manosphere influencers and the herds that follow their toxic, often misogynistic rhetoric, fitness at its core encourages men to stay healthy. For male-identifying members of TBC, it also opens the door to a community where camaraderie and support among fellow students help dispel inaccurate or harmful stereotypes, like gym bros. For anyone looking to take apart preconceived notions of what it means to be a man and put them back together — with consideration for their self-worth — the gym does not have to be another antagonistic symbol against a long-term goal.

IN BETWEEN HIS LINES

WRITTEN BY SAMMIE YEN

PHOTOGRAPHED BY PILI MARCO

DESIGNED BY SOLANA ESPINO

On a late Monday night, Tommy’s Place is steeped in tension. Indigo and gold ribbons of light slice across the room, creating a dreamy halo around the stage. The darkness shrouds murmurs passed between friends, punctuated only by soft clicks! of a billiard game.

Then, a slightly garbled voice announces the next performer. Keaton Orava, a ginger-haired sophomore from Washington, D.C., steps out under the glaring — or affectionate — spotlight. He is six-foot-something. He is wearing a flannel button-down and gray cargo pants. And he is, at this moment in time, a physics major.

Last fall, a general education class brought Keaton and I together. We were both green, wide-eyed freshmen, only having stepped onto campus a week ago. He was one of two people who consistently showed up to the study groups I organized. Since there were only three of us in that group, I arguably learned more about Keaton than I learned about our readings. We were both severe overthinkers, we both came from mediumsized suburbs of large cities and we both were the type of people who were excited about back-toschool shopping.

That class was classics-centered, which should have been the first sign that Keaton did not fit very neatly into the rigid lines of a physics student. Physics students do research in labs named after Nobel Prize winners. Physics students build water rockets to demonstrate aerodynamics.

Physics students do not invite me to an open mic night.

I must have raised an eyebrow when Keaton said, “I’m performing tonight at Tommy’s Place, if you’d like to come. It’s very, very chill.”

I never expected him to sing, much less play the guitar. Immediately, and without much thought, I blurted, “Like Ed Sheeran?!”

He sighed, saying he got that a lot.

Nevertheless, I was intrigued by the seemingly paradoxical nature of the night. Unfortunately, I saw him as his major, a conscious decision on a college application. He deliberately and methodically checked that “Physics” box. I almost expected him to stand up on stage in a white lab coat.

A STEM-art crossover wasn’t impossible, but it was rare to witness.

“In a weird way, it was narrative that drove me into physics,” Keaton says. “It was watching movies like ‘Interstellar’ and … historically-focused documentaries about astronomy. That inspired me to want to be a part of that story.”

Last October, I watched a science-fiction lover, general chemistry-enrolled Keaton cover Noah Kahan’s “The View Between Villages.”

Air in my lungs

‘Til the road begins As the last of the bugs

Leave their homes again

And I’m splitting the road down the middle

For a minute the world seemed so simple

The notes started soft — simple and subtle plucks at the thin strings of a guitar. His voice, a capillary wave washing over worn rocks, slowly seeped into the venue.

Keaton kept singing, but when the words “splitting the road down the middle” spilled out

is a narrative studies major from Washington, D.C. His last name means “squirrel” in Finnish.

IN

BETWEEN HIS LINES | Sammie Yen

Keaton Orava ‘27

IN BETWEEN HIS LINES | Sammie Yen

into the room, he was no longer on stage. Instead, he was very clearly standing in the middle of a curvy, Kahan-ian road that plunged into the folksy woods replete with pine trees and snowcapped shrubbery.

If he walked in one direction, the path was linear. He could easily head straight towards becoming a person, a fixed life, a pragmatic future he had chosen before.

“I was drawn to the official sound that physics gives,” Keaton says. “My original plan was a Ph.D. in physics.”

But, up on that stage that night, Keaton looked in the opposite direction, towards the obscured road beckoning with indeterminate, artistic possibilities and started walking.

“It was a few months into being a physics major that I realized that I was enjoying my creative classes a lot more than my science classes,” he says. “It was this ability to express myself in certain ways that I couldn’t do in the sciences. I felt this calling to explore further.”

For some, exploring the humanities means taking on a single specialty. For Keaton, his creative interests and aspirations delved into theatre,

writing and singing. To formally study these three modes of storytelling, Keaton chose to switch his major in narrative studies and minor in theatre.

His journey is more than an adjustment in academic focus. Choosing the arts marks an introspection in self-perception and identity.

A 2020 report by the American Physics Society detailed that 25% of physics bachelor’s degrees were received by women, which marks the highest percentage recorded. However, that statistic is a little shaky. Twenty years ago, the number was 23% — showing a minute increase in gender diversity.

Meanwhile, according to a demographics report released by the University of Southern California’s School of Dramatic Arts, 65% of the fall 2023 undergraduate population identified as female, while 35% identified as male.

Now falling in the gender minority, Keaton reflects on masculinity and how it plays a role in his creative pursuits. He grapples with where he fits into female-centric spaces and how his voice can resonate.

“Of the few men [in my program], there’s not that many straight men,” Keaton says. “If you’re

already existing outside of the traditional definitions of that, it’s a space that calls more, or maybe a space you feel more attracted to, versus if you’re living in that box of traditional masculinity. It’s a little bit harder to make that step.”

While male actors might be underrepresented in USC dramatic arts, Keaton recognizes the unique advantages this affords him.

“Because there weren’t a lot of these straight male people, and there are a lot of roles in plays for straight male people, it helped me get better parts,” he admits. “It’s just a numbers game, like there’s fewer people for more parts.”

Keaton is aware of his privilege in the creative space, and he doesn’t quite selfidentify with the “film bros who know everything and every film that’s ever been made.” Privilege, however, does not eliminate the struggle to be vulnerable on a stage, on a page or in front of the microphone.

Historically, masculinity and vulnerability are antonymous. In a field that prioritizes self-expression and emotional reach, Keaton challenges himself to push past the standard notions of what it means to be a man.

Is it filtering emotion? Is it only revealing emotion through the vessel of someone else’s song or someone else’s script? Where can the vulnerability be channeled from?

Across disciplines, Keaton describes how he sees vulnerability differ by medium. “With acting and singing, it is the most vulnerable. It’s just yourself … Everybody’s watching you. In writing, you can cloak things in fiction. Same with film, you’re behind the camera . . . but it all comes from the same place of needing to share truthful emotion and that expression with people.”

Emotion is not uniquely tied to femininity or masculinity, and Keaton recognizes that the expression of emotion transcends the boundaries of gender.

Writer Sammie Yen

‘27

is from Pasadena, CA and majors in narrative studies and communication. She loves talking about film, food and sports.

“This is sort of the main takeaway I’ve taken from the cross section of all my narrative classes,” Keaton explains. “It’s all based on human emotions, and everyone feels the same emotions.”

As he details his revelation, I can almost see his mind weaving the words together with careful intention, and it makes me smile. Keaton’s realization speaks to the core of his journey, that the fundamental aspect of storytelling, in whatever form, is humanity.

This October, I watched Keaton sing his selfpenned song, “Hallowed Town.”

A dozer’s driving down Fuller Road They’re gonna need another quote Cause there’s some things they can’t destroy

I know how to pick the sweetest berries I know even strong souls grow weary I’ve seen the lake in the setting sun I know what it means to love someone I know what it means to be loved

Almost a year later from that fateful night at Tommy’s Place, the story Keaton sings reveals he’s stripping away the obscurity of the road. His road, once split down the middle, is illuminated with each and every narrative he tells.

With the same black guitar in hand, the same slips of violet and burgundy light falling across his face, Keaton suspends his talents in the air with “Hallowed Town.” Wide-eyed spectators give subtle nods.

He sang with a confidence gained after a year of exploration that focused not only on technical perfection, but also emotional truth and weight. His presence and authenticity? Unmistakable.

Even though it isn’t a famed song yet, the audience gets it. And he doesn’t have to solve a physics problem to get his point across.

“Good stories always shine through, or they eventually do,” Keaton says. “People have been very accepting of this honest mode of storytelling that’s not cloaked in anything.”

Keaton’s performance of “Hallowed Town” embodied everything he had learned along the way about stories — the unfiltered human spirit, out there for the audience to see, to know and to connect with.

He lived his words: A good story of authenticity will always shine through. Keaton’s road, once obscured, has become his own to define.

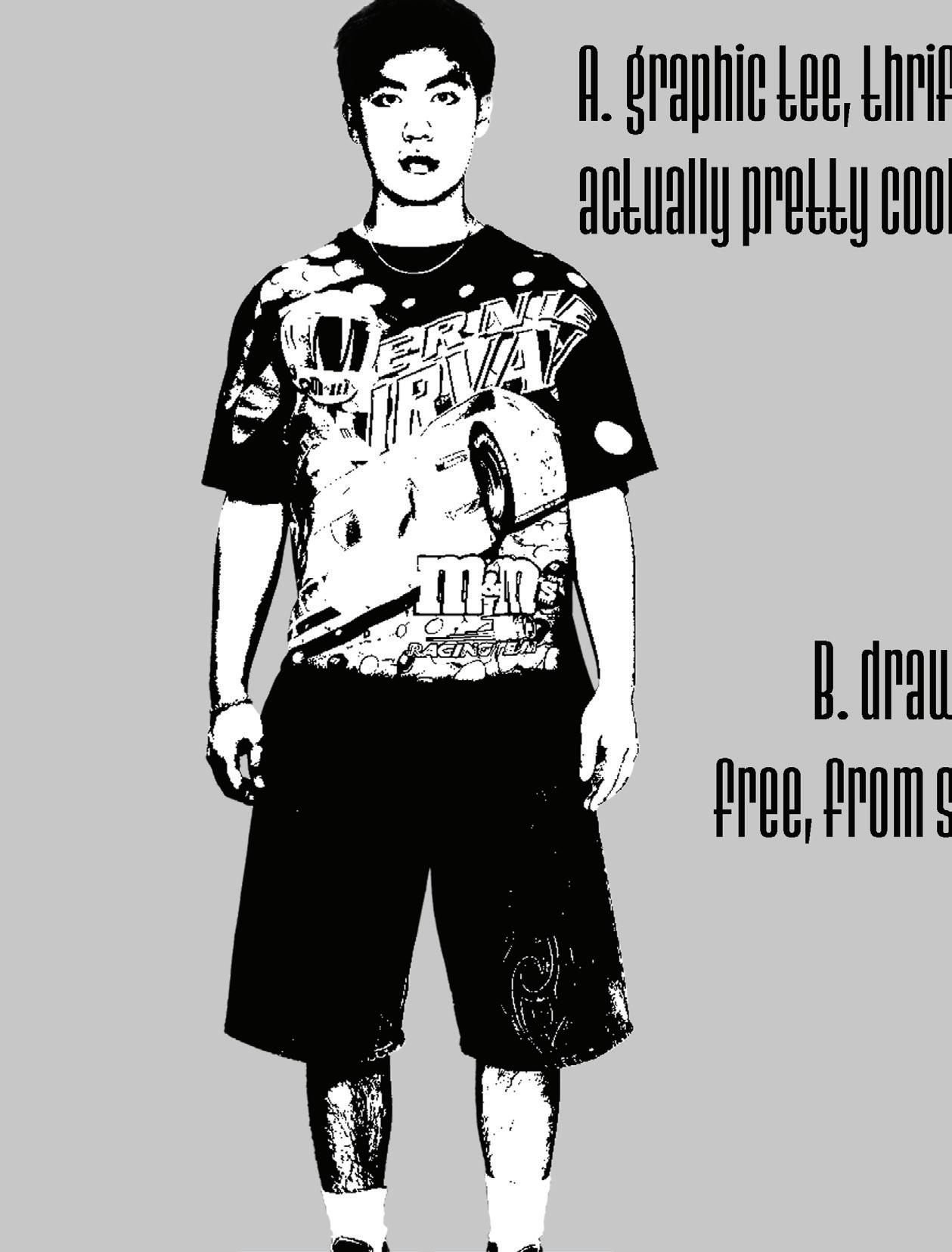

g actually raphic t-shirt cool

Ode to Gray Gray

Digging through my closet, out of the closet.

Written by Sullivan Barthel

Designed by Carlee Nixon Nixon Sullivan

Photographed by Anya-Kathryn Barrus by

Sweatpants hed

The time is 3 p.m. on a Saturday in midJanuary. The year is 2021. The place is Northborough, Massachusetts. At Kohl’s.

Yes, it’s a bleak setting. Central Massachusetts hasn’t seen the sun for over four weeks, but I’ve escaped the gray, slushy skies and cold drizzle for the windowless comfort of a big-box store with fluorescent lighting. Kohl’s is still playing Christmas music, and it smells faintly like cinnamon.

But, I’m here with a purpose. I move past the festive fuzzy socks and running shoes, past the muscletee’d models on ads for athletic clothes, taking care not to let my eyes linger too long. As I turn the corner, I see it. Just to the right of the checkout is a triple-decker display of Nike sweatpants — in gray, black and navy, with the small swoosh logo on the upper left thigh.

They’re perfect.

So perfect, in fact, that I bought three pairs: Two in gray and one in black.

Why this sudden compulsion to splurge on sweats? The year 2021 coincided with several dark and momentous life events: Political chaos, the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic and my high school graduation, which at the time felt similarly existential. It was also the time in my life during which I was the most deeply closeted.

So, on this particular Saturday in January, I decided that it was time to grab the steering wheel of a ship I thought was sinking and to right it; in other words, by dressing like how I thought straight guys were supposed to dress, I would once and for all prove to my high school — and to myself — that I was someone I knew I was not. In my case, all this dread and denial manifested itself on that day as three pairs of Nike sweatpants.

Model Andrew Huang ‘27 is a business of cinematic arts major from Shanghai, China. He’s learning how to juggle.

beat up old converse old

I’m happy to report that I’m long since out of the closet, and that I no longer dress like a washed-up New Englander who was out too late at the pub last night and is showing up in the same stained sweats he’s slept in for the past few days. But even as I’ve changed states and life stages and wardrobes, the same question has nagged me. It’s hung over my head, tormenting me with folds of plushy fabric and a distinct lack of taste. Why did I need to buy those sweatpants?

Follow me as I answer this question once and for all — for myself and for all the guys out there who yearn to escape the clutches of drab straight mens’ fashion. Let the search begin!

***

I wracked my brain trying to decide who could provide me guidance in my search. And then it hit me: I needed to take a step back. Who knew me best during my sweatpants-laden high school career? More importantly, who wouldn’t hold back in their critique of my fashion sense?

That’s where Mary Kate Lunt comes in. She’s been my ride-or-die since our freshman year of

high school. I met her on the first day of English class. According to photo documentation, I was wearing a school-issued navy blue Shrewsbury Colonials Superfan t-shirt. (That shirt has since been excised from culture.) Mary Kate told me a few years later that I had weirded her out.

Since then, she’s seen my highs and lows and everywhere in between. We also have an unbroken tradition of Black Friday clothes shopping every November. On this occasion, I call Mary Kate while she’s driving back to her apartment in Chicago.

She describes my closeted fashion sense as “bland.” It was characterized by dark colors — blacks, navies, grays — and staple outfits that I would wear just a bit too often to be socially acceptable. I wore sports shirts and did not play any sports. But, her hypothesis on why I dressed that way struck me.

“Your outfits were always maybe an outward expression of hiding everything in,” Mary Kate tells me. “[They were] definitely to not be perceived too much. I don’t think I ever saw you in anything bright or even light colored.”

...by dressing like how I thought straight guys were supposed to dress, I would once and for all prove to my high school — and to myself — that I was someone I knew I was not.

As I turn the corner, I see it. Just to the right of the checkout is a triple-decker display of Nike sweatpants — in gray, black and navy, with the small swoosh logo on the upper left thigh.

That part was probably to be expected. Thinking back on my high school self, anything eye-catching or even mildly Bohemian would have seemed to me to have an air of femininity. You might think that I chose my clothes without care, but that couldn’t be farther from the truth. Very few teenagers have chosen their shorts so carefully so as to not match with their running t-shirt. Those who have probably shared a secret.

Was I fooling anyone?

“No,” she says.

But, “I think you prevented people from asking or from saying anything.”

In other words, my lazy outfits gave me plausible deniability. If someone thought I was gay (because I was), my American Eagle joggers would beg to differ. And if, God forbid, someone ever asked me that question that every closeted boy hopes to never hear, and I would just choke up and avert my eyes, the evidence on my body would speak for me instead. Or so I hoped, at least.

But, where did my ideas about straight mens’ fashion come from in the first place? Why does straightness translate to a lack of style? To answer that, I’ll turn to the experts. ***

When you enter Dr. Alison Trope’s office, the first thing you’ll probably notice are the paper doll outfit cutouts. They’re life-sized, if not bigger, and lean against the wall adjacent to the door. A USC Annenberg graduation sash hangs around the neck of one number.

Dr. Trope is a clinical professor of communication at Annenberg. In the fall, she teaches a class about fashion’s role in identity and body politics. When I speak with her, she has just finished two weeks of lectures about menswear.

Where does the idea that men can’t — or shouldn’t — dress well originate?

“Historians trace that to the Enlightenment; they trace it to Protestant work ethic…”

What? I splurged on the most boring sweatpants known to man in part because of the Enlightenment?

“Yeah,” she answers.

Dr. Trope points me to the “masculine renunciation,” a phenomenon that historians trace to the late 18th century, when European and American mens’ clothing rejected opulence and moved towards practicality — it also deepened divided gender roles in fashion.

“Gray sweatpants are just another iteration where this casual wear is bland,” Dr. Trope says. “It’s about not showing that you have any kind of fashion sense.” Maybe I was onto something with my high school outfits.

The idea that fashion is feminine isn’t just gendered; it’s filtered through the lens of sexuality, too. Dr. Trope says that in the 18th and 19th centuries, a “dandy” was “someone who cares excessively about their clothing, who consumes [and] who wants to be on display.”

“There, we get this conflation, where, if you care about how you look, not only are you feminine, you’re framed as gay,” she says.

ODE TO GRAY SWEATPANTS | Sullivan Barthel

Writer Sullivan Barthel ‘25 majors in journalism and has minors in art history and legal studies. He’s originally from Worcester, MA, but his valley girl voice is impressive.

It was characterized by dark colors — blacks, navies, grays — and staple outfits that I would wear just a bit too often to be socially acceptable. I wore sports shirts and did not play any sports.

“Gray sweatpants are just another iteration where this casual wear is bland,” Dr. Trope says. “It’s about not showing that you have any kind of fashion sense.”

white button up, worn to both class and frat formals

It’s a demeaning social construction, and it’s spot-on to my fears. While I didn’t have the sociologist’s vocabulary to back it up, the modern “dandy” was the idea that tormented me during my years in the closet. It’s the stereotype I was — and maybe still am — the most sensitive about. He’s the flamboyant twink; the glammedup Sephora employee; the slutty party animal; he’s even the gossip-loving gay best friend. And maybe, if I wore enough gray sweatpants, nobody would think that I could ever be him.

So, now I know: Maybe all of those groutfits were a defense mechanism to combat stereotypes rooted in the late 18th century that permeated my suburban Massachusetts high school. That’s probably true, and they were probably also the defense mechanism of an insecure teenager.

I’m getting to the end of my search, but I think I have one more stop to make; there’s only one place that can truly tell me why I’ve been losing sleep over sweatpants.

I’m going back to the closet.

My dresser at home is a fashion crime scene. If a drawer were to be opened and displayed to Anna Wintour, she would probably pass out — and not in a good way. The clothes still in it have the air of survivor’s guilt; in the three years since I left home, it’s accumulated all of the unlucky souls who didn’t make the cut to be in my college wardrobe but were too sentimental to donate.

Here are a few highlights: A workout shirt from Nike Fifth Avenue, which I bought during my sophomore year because I thought it perfectly walked the line between stylish and straight. (It’s plain white and has a silkscreened palm leaf. I didn’t work out.) A pair of tapered black joggers that were cool in 2018 and then never again, and whose metal drawstring tips are rusted from so many wash cycles. A Champion long sleeve, which I remember stressing about because the logo on the back was vaguely in rainbow colors.

It’s the stereotype I was — and maybe still am — the most sensitive about. He’s the flamboyant twink; the glammed-up Sephora employee; the slutty party animal; he’s even the gossip-loving gay best friend. And maybe, if I wore enough gray sweatpants, nobody would think that I could ever be him.

(I probably wore it twice after I realized.) A t-shirt from a Jewish deli that reads, “Challah Back.” (I bought that one after I came out.)

I would be lying if I said it didn’t shake me up a little bit to perform this autopsy, because while I think I’ve moved past my four years in the closet, the evidence of that time is still sitting in my bedroom at home. I don’t reflect on high school as a particularly difficult time; I loved my friends and was generally pretty happy. What I see, though, in my dresser, are the clothes of someone who was motivated by shame. That person is so different from who I am now that it throws me off.

Looking back, I probably could have dressed any way I wanted to. I’m so fortunate — and so privileged — that I knew my family and friends would accept me for who I was. Probably, hundreds of millions of other gay people didn’t have that experience. It’s just that I couldn’t admit it to myself. Shame about who I was drove me until it became unbearable during my senior year, right around the time of that trip to Kohl’s.

I was doing chores during my freshman year at USC, and I bumped into a friend in the laundry room. It was the middle of the night, and we talked for probably an hour while our clothes dried. At one point, she asked me if I was comfortable in my masculinity. Admittedly, that was a lot for a Tuesday at 2 a.m.

My answer surprised me: I told her that I was. I’d been out for probably five months at the time, but it didn’t feel anymore like I was trying to be someone I was not. We kept talking, and a few minutes later, I unloaded my pink t-shirts and short shorts from the dryer and headed up to bed.

I finally have the answer to my question. Why did I buy all those sweatpants? Yes, I was trying to prove that I was straight to the world, but I was more importantly trying to prove it to myself. I was trying to show myself that I was man enough, and to me, that meant dressing terribly. If I could grit my teeth and wear sweats every day, someday maybe I would be.

There’s a giant, unorganized pile of clothes at the bottom of my closet. It’s mostly merch from the clubs I was in during high school — speech and debate, orchestra, the French Honor Society. (I really wasn’t fooling anyone, was I?) As I dig through it, I realize there’s something missing: Three pairs of Nike sweatpants.

I’m stunned — where did they go? They’re not at college with me. I don’t recall marking them for a donation. Maybe my younger sister stole them because they’re in style now. Maybe I just cast them out of my closet and can’t remember it. Maybe they took on a life of their own.

Let the search begin!

sweatpants gray

Morgan Fierro ‘25 is a narrative studies major from Westport, CT. He’s a dual citizen in Australia.

ON MERIT AND MOVEMENT

Written by Alexis Lara

Photographed by Luqman Abdi

Designed by Julia Zara

Some people find comfort in the familiar faces of their small New England hometown. Others yearn for plane rides, passports and foreign languages on the nameless streets of places they’ve never gone. USC senior Morgan Fierro straddles the line of multiple worlds, never staying stagnant for too long.

“Everyone loves to travel, sure, but I love to just really, really get down and dirty and really get into different cultures,” Morgan says. “I love to just talk to people.”

During the summer of 2022, Morgan worked on a farm in Maui — a long way from home for the Connecticut native. A year later, Morgan read a story that evoked wandering dreams in his traveling mind. “The Places in Between” by Rory Stewart inspired Morgan to embark on his own travels abroad the summer after his sophomore year of college. He chose the Via Francigena, a pilgrimage route that crosses countries in

Writer Alexis Lara ‘25 is a journalism major with a sports business and management minor from La Cañada, CA.

Europe by foot. Morgan and his friend Max trekked around 30 miles every day through Italy, beginning in Genoa and ending in Rome.

“I learned so much about my family’s culture and Italian culture, and really felt deeply connected to that after that trip,” Morgan says. “I look back on that trip a lot, very fondly. As a writer, it obviously provides a lot of content to write about and reflect on,” he adds. To this day, that 400-mile pilgrimage is his proudest accomplishment.

While his summers are spent traversing the edges of the earth — even buying a motorbike in Vietnam and riding it as far as he could this past summer — that search didn’t end once the fall semester begun. Beginning his college career as a business major, then switching through environmental studies, journalism and narrative studies, Morgan explored his interests to their full extent.

“I was trying to avoid the fact that I really love to write. This semester I’ve accepted that, and I’m leaning into that more. I love to write. I love to read. That is the artform that has impacted me the most in my life. It’s led me to make decisions and led me to pursue experiences,” Morgan says.

Despite stumbling across this hidden talent years ago, Morgan remains passionate about writing now more than ever. He first found comfort with a pen in hand and a blank page in a high school creative writing class. Discovering the depths writing can take him to, and retrieve him from, was a happy accident.

“I just loved that creative freedom. I got praise from my teacher about my writing, and that felt really good. I was like, ‘Hey, I’m good at this. I really enjoy it.’ And there’s just certain art forms that I think speak to certain people,” he continues. “For me, writing is something that speaks to me. At certain points in my life I’ll read a book and I can find myself in that book, or I can resonate to that experience.”

From Walt Whitman to James Baldwin, Morgan searches for solace in literature and finds direction in his own life with every passing chapter. He sees reading and writing as a lost artform, one he has revived at college.

“I understand on paper [that] an engineer or a business major is going to make more money than an English major, but there’s absolutely merit in literary fluency and being able to read and actually engage in a text and writing,” he says.

Morgan is pursuing a progressive degree in literary editing and publishing, hoping to one day publish his own writing. Despite this love for writing, his entire identity cannot be bound within the pages of a book. In fact, Morgan has found a home at USC as a student-athlete.

Like many other Northeast natives, he found the field with a lacrosse stick in hand. Entering Staples High School at 5-foot-4 and 100 pounds, Morgan searched for ways to prepare himself for the upcoming lacrosse season and discovered running.

“I am the classic ‘I started running to get into shape for another sport,’” Morgan says after trying out cross-country to help with his lacrosse. “I won the first race that I was ever in. And was like ‘Wait, hold on, I’m kind of good at this.’”

Now 22 years old, Morgan is a student-athlete

at a Division I school. His cleats still press in the ground with every stride. His chest still rises and falls with every breath. He is still faster than the person standing next to him — but not in the sport he originally envisioned. Instead, he found his way to the West Coast because of the sport he accidentally excelled in: Track.

“It got me into school here. It gave me opportunities to look elsewhere and it’s brought me the greatest friends ever. My friends from high school are my closest friends in the world, and most of them I met through track,” Morgan says.

Like writing, distance running became a serendipitous success, especially since he won the first race he ever competed in. With USC only having a track and field team and not cross-country, the team sport Morgan once knew evolved into an individual endeavor. He forges connections in training yet sustains himself through his unique tactics. Now, he has traded his high school superstitions for pre-race meditations.

“Before I warm up, I’ll try to meditate for about 10 minutes. Just ground myself in the moment, ground myself in the competition,” he says. “Last indoor was my best collegiate season. I had a lot of stuff going on, and I was always thinking about a lot of stuff, so I’d meditate.”

Setting personal bests throughout the season, Morgan’s athletic accomplishments are the physical manifestation of the time and work he put in. At the end of the spring season, Morgan’s fellow USC athletes voted for him to win the “Overcoming Adversity” Tommy award. Balancing the academic rigor alongside strict training schedules as a student-athlete is a relentless endeavor, but for Morgan, that is not all he faced.

“That meant a lot to me and a lot to my family

ON MERIT AND MOVEMENT | Alexis Lara

to get that award, because I just think it showed to me, USC and my teammates recognizing, ‘Morgan’s been through a lot, and he’s still been a very positive person and influence on the team,’” Morgan says.

The challenges Morgan faced came when the phone rang his sophomore year of college delivering the gut-wrenching news that his mother, Lisa Fierro, was diagnosed with stage three ovarian cancer. On the opposite side of the country and in the midst of classes, Morgan visited home as often as he could, but he leaned on phone calls with his older sister Alexandra, during the difficult time.

“I would call her, and we’d check in on each other and kind of walk each other through what was going on and how we were feeling. And she loves me a lot, and I really appreciate her for that,” he says. “As we get older, we get a lot closer, but we hated each other in high school.”

Alexandra now lives in Florida. About four months

after they found out about their mom’s diagnosis, Morgan received the news that Alexandra had thyroid cancer. Before he could find his footing again, Morgan found out that his dad had oral cancer.

“It’s just a very scary diagnosis. I think you, in the moment, jump to the worst scenario possible. Once that dies down to then get more bad news, and then that dies down to get more bad news, it was a never ending thing. My family’s definitely been through a lot,” he continues.

Trusting in the home that Morgan built for himself at USC helped the Fierro family deal with the strain of distance on already difficult times. The “Overcoming Adversity” award stood not only for the strength of the Fierro’s, but for the support from Morgan’s fellow athletes and USC.

“My parents are sick. They’re the ones really overcoming adversity. My mom is so amazing. She’s such a fighter. She’s still battling cancer right now, and it’s just representative of USC

acknowledging that, and seeing me and my family through those struggles, which definitely meant a lot,” he says.

Track is just one part of who Morgan is, not the totality. He is not defined by any singular passion or hardship. He is leaning into artforms he loves while discovering new ones. The reach of his passions extend far beyond his athletic accomplishments. He is a traveler never settling on one path but always expanding his horizons.

Morgan is an avid writer always working on his next chapter.

WRITTEN BY ANDREA ARCIA PHOTOGRAPHED BY KAYDEN-HARMONY GREENSTEIN

By the time I stumbled upon Ethan, at nearly 2 a.m. in the dimly lit backyard of some nameless house party, I had already fallen over myself three times. The plastic firefighter hat I’d stolen from the patio was slipping down over my eyes. Under no other circumstances would I have been so drawn to a guy freestyling on a stack of chairs, unintelligibly, with a frightening amount of confidence. But, there I was, tipsy and oddly mesmerized.

As the chaos of DPS arriving sent everyone scrambling, my roommate grabbed me by the arm and dragged me into an awaiting Lyft, her expression somewhere between disbelief and amusement. Later, she would shake her head, laughing to herself, “The nerve of that guy.” It became a story Ethan and I would come to reminisce over fondly. A seemingly insignificant moment turned into a beautiful friendship, though one tainted with uncertainties and plenty of missteps.

As it stands now, and I’ve told him this many times, Ethan holds a place in my life that I didn’t even know I wanted. We analyze films a little too deeply, walk down streets debating the same point from every angle and opt for couple’s yoga or seventh-grade “Jeopardy!” instead of going out on Friday nights. He talks to me about his romantic problems, where I tend to tell him he is the problem, and I confide in him about my own just to get the worst advice on planet Earth. Ethan nudges me to embrace life, push beyond my type A tendencies and explore the entire alphabet. He is the most sassy, nonchalant, yet passionate and kind soul I’ve ever met.

As it stands now, Ethan is one of my best friends — but it hasn’t always been that straightforward.

DATING ALLEGATIONS |

Andrea Arcia

Model Thomazin Jury

‘25 is a dramatic arts major from Iowa City, IA. She’s also a classical ballet dancer.

Ethan: Chaotic. Honest. Colorful.

Andrea: And over the course of this “colorful” friendship, would you say there were any hardships we went through?

Ethan: You generally disrespect me pretty often. (Laughs) No, I’d say yes. During our sophomore year, we had a rough patch because, well, people in all sorts of relationships have needs. Mothers and children have needs. Fathers and children have needs. Everybody has needs.

Andrea (Sarcastically): Are you a politician?

Ethan: Sometimes your needs aren’t met, or expectations go unfulfilled, or boundaries get crossed. That’s what causes someone to draw a line in the sand. That’s pretty much what happened. You were like, ‘I can’t deal with you anymore,’ and I was like, ‘Damn.’

Andrea: So you couldn’t meet my needs?

Ethan: Yeah, I guess.

Andrea: What were my needs?

Ethan: I don’t know. I couldn’t list them out, but I’d say respect. I never disrespected you, obviously, but it was complicated.

Andrea (Baiting): Why was it complicated if we were friends?

Ethan: In most people’s lives, there’s this overlap between friends and romantic partners. Not for everyone, but to me, it’s weird if your romantic partner is completely separate from your friends. Like, they don’t get along with your friends or don’t know them — that just feels off. I felt like that’s what was happening with me and this… other individual.

Andrea: We could call her Sarah.

Ethan: Yeah, me and Sarah and you. It felt like a one-way street sometimes, and that’s not how it’s supposed to be. Information was only flowing one way.

Andrea: You’re saying so much and nothing at all.

Ethan: Yeah, dude, it’s hard to explain. There are so many other factors. What would you say?

Andrea: The issue is that sometimes it’s hard for me to put a precise label on relationships. When I click with someone, it’s hard for my brain not to go. . . there.

Ethan: But, you’re also the type of person who will cut someone out if they’re not truly serving you in a beneficial way.

Andrea: That’s my logic, but it takes time to get there.

Ethan: Ultimately, you’re capable of drawing those boundaries, where I’m not, I would say.

Andrea: The issue is that those boundaries weren’t set from the beginning.

Ethan: Okay, I’ll buy that.

Andrea: Because we were just playing a guessing game of, like, ‘Where’s the line we can’t cross?’ I think we were friends, but there were times when romantic energy would be there and then disappear.

Ethan: You thought I was the sh*t.

Andrea: I still think you’re the sh*t.

Ethan (Whispers into mic): I am the sh*t.

*Author’s insert: I really need to pick and choose when to humble him.*

Andrea: From my perspective, you played into it because, who wouldn’t like that attention? But there were so many blurry lines and gray areas that went unaddressed for a long time.

Ethan: I’ll buy that. I was playing into certain things, but remember that time I gave you a flower? And you started tweaking? Granted, I get the miscommunication, but it’s the accumulation of little things like that that changed how we perceived what was going on. That flower wasn’t an act of courtship to me. I was just like, ‘Okay, I found this flower, take it.’

Andrea: You also have to understand, though, I wasn’t interested in you from the beginning and didn’t want to be. So, when you were doing all that and people made comments like, ‘Oh, you guys are so cute together,’ it skeeved me out. That night specifically, as soon as we walked into that function together, I hadn’t even made it to the back of the house before Maya jumped to congratulate me, saying, ‘Oh my god, I’m so happy for you guys!’ I couldn’t even process it, and then you came over with the dainty flower you picked up off the ground.

Ethan: I just found it! I just gave it to you. That’s what I’m saying, though. It was just an act of kindness. I’m a generous guy.

*When I called him kind before? This is not what I meant.”

Andrea: Alright, Mr. Generous, what would you say your type is?

Ethan: I want somebody who is open about things; I like a little bit of wildness, people who are okay with being crazy and not judgmental. See, this is where we differ, because you can write a list of, like, ‘I would like him to be able to speak Spanish. I would like him to have interests. We would like to go to the gym together,’ or just general fitness and health overall is important for you. Those are two good examples that I don’t think you would argue with, but for me, I like people who are wild. Wild and open.

Andrea: Would you say I fall into that?

Ethan: You’re pretty wild, but I’d say you’re more disciplined.

Andrea: So, I wouldn’t be considered your type?

Ethan: At this stage in our friendship, I would say no.

Andrea: If we didn’t have a friendship?

Ethan: Maybe. I would say no, though, like, for right now, because, just how we are as friends, if we were to date, it would be a disaster. It would be a real, real disaster.

*After watching “Marriage Story,” we had a screaming match of our own. Ethan tends to play devil’s advocate.*

Andrea: On that note, do you think platonic friendships between men and women need to address any potential romantic tension upfront to work?

Model Christian Bipat

‘25 is a business administration major from Waldorf, MD. He hiked Scout Peak at Zion National Park.

and

DATING

Writer Andrea Arcia ‘25 majors in narrative studies. She has a minor in legal studies

another in Italian. She was born in Venezuela and was raised in NYC.

Ethan: Yeah, if you don’t, you’ll just be playing this guessing game. How can you fully enjoy someone’s presence if you’re always guessing? You need to get it out of the way, at least for yourself.

Andrea: This applies to all your female friends?

Ethan: Yeah, definitely.

Andrea: And do you define the line between just friends and something more with a girl? Who usually sets that boundary?

Ethan: It’s just a vibe, bro. I really couldn’t tell you exactly. It’s kind of instinctual. My friends are my friends, and my romantic interests are separate.

Andrea: But, we talked about ruling out romantic possibilities. What usually indicates that?

Ethan: Yeah, I’m pretty honest with you — not that I’m not honest with my other friends, but with you, it’s pretty raw. I don’t hold back as much. I think I’m just less afraid to tell you things.

Andrea: You’ve previously described knowing ‘too much’ about your female friends to see them romantically. What did you mean by that?

Ethan: Maybe this is off-kilter, but part of sexual tension is mystery. Once the fog is lifted, you start questioning whether you really want to go there.

Andrea: How is that different from being in a committed relationship?

Ethan: It’s also how you see the other person. Like, I work with [certain people]. I could never pursue anything with them because we’ve seen parts of each other that would complicate things. If you enjoy someone as a human being, it’s usually better to just be friends. You only have something to tarnish. Of course, that’s not always what I’ve done in the past. Sh*t happens. But, you need clarity about what’s worth tarnishing and what’s not.

*My favorite fun fact about E is that he grew up doing ballet, starting on Broadway, and now he’s at USC for musical theatre. The man has been surrounded by girls and emotional intelligence his entire life. I suspect that’s the only reason why this works.*

Andrea: Do you think our dynamic differs from how you interact with your other female friends?

Ethan: It’s not the things that people tell you; it’s how they tell them to you and when. When I’m talking to someone, and there’s a romantic energy surrounding it, I am not trying to talk in depth about the people from your past, who you’ve been with, in what ways… Even then, when I do hear those stories, in romantic relationships, there’s this assumption you won’t see those people anymore. With friends, that assumption doesn’t exist. I hear those stories from friends and it’s like, ‘Okay, good for you, buddy. Go wash your hands.’

Andrea (Snickers): Yeah, it’s just completely honest and transparent.

Ethan: Which doesn’t make you any more desirable. Your buddies are your buddies for a reason.

Andrea: So, when it comes to those purely platonic friendships, do you think the lack of romantic involvement is due to a lack of attraction, or is it just a conscious choice to set boundaries?

ALLEGATIONS

Ethan: You really have to look at the type of relationship you have with someone before you do anything. Attraction is often just a derivative of lust, and that fades — it’s a pretty fickle thing.

Ethan went on to talk about how that’s what our situation came down to. There was some romantic energy between us that we embraced for a time because it “felt right in the moment.” But, ultimately, it was about confronting whether or not the path we were heading down was the most fitting — for who we were then and what we wanted. It’s easy to think that every rare connection must be romantic, as if a bond so special demands to be reshaped into something more. But, sometimes it’s better to let those connections breathe, to let them stand as they are and to resist the labels that try to box them in.

As for whether true platonic friendships between men and women can exist in a world that insists on sexualizing opposite-gender dynamics?

I think, yes, they can. It’s possible, but rare. It demands more communication than most people are willing to give — a careful balance to ensure boundaries don’t blur and that you’re both still standing on the same ground.

But, friends like Ethan? They’re rarer still. So now, when we get those dating allegations, I just laugh to myself. They have no idea how wrong they are, or how special what we truly have is — they wouldn’t even know how to want it.

THE INTERNET BOYFRIEND

Photograped by THOMAS PHAM

Designed by OLIVIA HAU

Mysterious. Troubled. Raspy voice. Plays guitar in a Grateful Dead cover band. Wears Dior Sauvage cologne to mask the smell of his cigarettes. Self-proclaimed “bad boy.”

Model Phillip Tran ‘26 can play harmonica and juggle at the same time. He is also a real estate development major from Dallas, TX.

HE WEARS (POSSIBLY FAKE) GLASSES AND LISTENS TO CLAIRO WHILE THRIFTING.

WHAT A CUTIE! SURELY HE WILL TREAT ME DIFFERENTLY... RIGHT? RIGHT?!

Photographer Thomas Pham ‘25 is a business administration major with a cinematic arts minor. He’s looking for his muse and a good time.

He bought a turntable last week and now insists he’s inspired by oldschool Ibiza, despite never having left L.A. Half of his set is just Spotify playlists, but he leans into every track like he’s headlining Coachella.

These images are staged and are for artistic purposes

“Father, if I don’t have the funds by Friday, I’ll be the only one arriving without a driver. Do you really want your son stumbling into the manor in a rental? It’s practically social exile!”

These images are staged and are for artistic purposes

BEHIND THE

THE MASC

Photographed by Kayden-Harmony Greenstein

Designed by Sesame Gaetsaloe and Julia Zara

BEHIND THE MASC| Kayden-Harmony Greenstein

Model Rena Pau ‘26 is a cognitive science major from L.A. She was born in Chicago, IL.

NOT TIED UP. NOT TIED UP. NOT TIED UP. NOT TIED UP. NOT TIED UP. NOT TIED UP. NOT TIED UP.

NOT TIED UP.

BEHIND THE MASC| Kayden-Harmony Greenstein

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

CLOTHES AREN’T GENDER

SHE HIT HER WITH A CAR

SCeeing Red with Evan Estevez Rodrigues

Designed by Solana Espino and Carlee Nixon

“Well, one of my friends hit another one of my friends with the car by accident. They don’t talk anymore.”

Want to listen in on the full conversation? Find out what happens next on SCeeing Red, a SCene Magazine podcast.

PART 1: THE INTERVIEW

Evan Estevez Rodrigues: How does being a man define it all — your music making, your Seattle living, etc.?

Ari Rose-Marquez: I would say in my day to day life, I’m actually not very conscious about my gender, and I feel, arguably, that is because I’m the beneficiary of being a man and don’t have to think about my gender, especially just around USC. Like leaving parties at night and not worrying at all about walking home by myself. I think it’s the little things that I take for granted, but it’s subconscious.

Evan: On that flip side, what does masculinity mean to you?

Ari: It’s tough because I think, well, masculinity is really how we perceive male characteristics, right? And that, in and of itself, is just gender, which is a social construct. But, I think the piece about masculinity being perceptive is key for me, because I think it says a lot less about how you project yourself and more about how you’re interpreted [by] other people.

Evan: Do you think that your perception of that has changed over time? From when you were little or when you were younger, to where you are now, as a full grown adult?

Ari: A little bit. And I think in part because I’ve grown into myself and my identity, but I think more so because of the general discourse around masculinity and toxicity related to masculinity, and I think for a lot of men, and to generalize a lot of us in our age group, I think [have] grown up hearing a lot about toxic masculinity and being

very aware of what is perceived as toxic masculinity. In kind of a funny way, I think even people who don’t think of themselves that way, or who would avoid being described that way, are maybe still participating in toxic masculinity, but it’s not just based on how someone dresses or how someone talks or how someone acts. It’s deeper than that.

Evan: I mean, disclaimer, we go to USC, and it has a massive frat culture, sorority culture, Greek life, in general. Just walking around, how do you think being here, in this environment, differs from [your view]? Do you have any opinions on that?

Ari: I should preface my frat is, I think generally perceived as a more inclusive or diverse fraternity here, and so that may skew my perception of Greek life. I think it does, in fact, skew my perception of Greek life. I think that this speaks to a kind of toxic masculinity [that] would, I think, fall on socioeconomic fault lines. The vast majority of people in Greek life have the funds to afford to pay dues, to be participating in that, to have the time and resources to participate in that. And overwhelmingly, it’s white men. So, I think just being in that environment can kind of beget some of what people would perceive as toxic masculinity.

Evan: I definitely understand what you mean. It’s just different to everyone. If you were to [plan] out a class on ‘How to be a Man,’ what would that curriculum look like? How would you want to approach that?

Ari: I think I would start by considering how men should treat other people. I think this would probably be my first lecture, because I think the perception of men is wholly reliant on people’s experiences with men, with how they perceive men, or masculinity in the media. And I think also unpacking the idea of masculinity: Is it how you look? Is it how you sound? Is it what you are interested in, your hobbies? Or, is it really about how you’re perceived again? And I think that’s what I’ve learned the most about masculinity is. It’s really about how other people would define you or identify you and not necessarily how you perceive yourself.

Evan: Do you think that how you approach things is ever different because of your gender? I know, for me, there’s always ‘tough guy’ skills. Do you wish that you had, through that lens of the traditional outlook of ‘what a man is’ or ‘who a man is,’ are there any things that you kind of look at and think, ‘That’s a skill that a man should have that I necessarily don’t have?’

Ari: That’s really interesting. Well, okay, so I grew up doing a lot of home projects. We moved into a new house when I was eight, and

we did a bunch of crazy renovations and demolitions over a five-year period. And so I learned to do a lot of those [things] I think what you were alluding to when you talk about stereotypically masculine tasks or roles. I think [in] my mind, and probably a lot of people’s, goes to construction or building, the home carpentry, and that’s kind of the dad I grew up with. And so I learned to drywall at a very young age, use a circular saw, and so there’s a lot of those things that I think you and other people would associate with masculinity or the roles and responsibilities of a man, especially in a home setting or context.

PART 2: THE RAGE READ

We are joined by not the one and only, but the two and only Kassydi Rone and Kayla Rocha.

Evan: Does anybody have a hot take? So, a Reddit user said… common courtesy is dead.

Kassydi Rone: Common courtesy, do you think that’s the same as chivalry?

Ari: I was going to ask the same question.

Kayla Rocha: Can we define it real quick? What do we all think?

Kassydi: See, I feel chivalry is very gendered, like it’s just pertaining to men, whereas common courtesy feels all inclusive.

Evan: I do see that. For common courtesy, if you don’t hold the door open for me, I’m literally going to be like, ‘Oh, that’s crazy.’

Kassydi: The amount of times someone has let a door slam right in my face — it’s just insane to me. It’s not a huge deal, I guess, but it’s just those little things. I’m like, ‘You see me carrying stuff? I’m two footsteps behind you. Can you please just keep the door open?’ Or, then that happens, and I drop something, and three people walk by me, and I’m like, ‘Wow, okay, this day is just getting better and better.’

Kayla: Especially when you’re entering your building, and you need a key to get in or something like that, that actually drives me insane. Like, if I’m carrying something and I could just pull it open with my hand, but I got to bring out my key, tap it, and you were there. You were there. This is making me mad right now.

Ari: That makes me angry, actually.

Kassydi: Another thing too is elevator etiquette, because

you just made me think of, when you get into your building, and I’m like, ‘Okay, guys, why are we standing right outside of the door? Let me come out first.’ You let the person come out, and then you go in. You don’t just start going in at the same time.

Ari: So, what would you guys say that distinction is between? Because, I agree that chivalry is more gendered than common courtesy, but in my head, and maybe this is because I’m a man, but, — I think a classic example of chivalry would be a man holding a door open for a woman, not that that that wouldn’t be considered common courtesy, even though it is, that would be considered a form of chivalry. What do you guys think?

Kassydi: I don’t know. I agree when I think of holding the door open. I usually, in a very traditional way, picture a man holding a door open for a woman. But, I also feel if that’s how we’re defining it, then I don’t think common courtesy is dead, because I feel women do that a lot more often for me than men, but I feel like chivalry is kind of dead. Not going to lie.

Kayla: I feel it’s the other acts of chivalry that I think of as gendered. Like, opening your car door for you, a man opening a car

door for a woman. I feel that’s like, ‘Wow, that’s really chivalrous.’ Whereas, I think a distinction between holding the door open when you’re walking through, versus, pulling the door open and letting somebody go first, I think that’s different. I feel that’s more chivalrous, whereas, common courtesy is holding the door open for that person. Evan, what do you really think?

Evan: I think that’s kind of an awesome way to separate it, because now I do kind of see that when somebody does that where, they step back and hold the door, I’m like, ‘That was so chivalrous.’ If somebody holds it behind them, that’s just something different.

Kassydi: That’s common courtesy.

makes you mad. How do you come back from being mad?

Ari: That’s such an interesting question. I think it’s personal for everyone. But, I think for me, I find that a little bit of solitude, so I can actually sit and think about my thoughts is something that I personally need. And then also, I think, as much as I hate confrontation, I’m just not a confrontational guy. I do think in order to resolve any serious or real issues or feelings or animosity, you have to sit down and talk it out. Just to articulate how you’re feeling in the moment, even if it’s unfair, I think is really important and also allows you to potentially resolve an issue with someone.

Ari: So… is it about taking the initiative? Is that the distinction? Common courtesy is an expectation, whereas chivalry is this taking of initiative.

Evan: Ari, we talked about what

Evan: You heard it here first. I think that’s a beautiful idea that we should end on — the idea of talking through your feelings and letting everyone know that you don’t have to be alone, and at least for when you want, except for when you want solitude.

Ari: Yeah, and I think also a part of that is allowing and combating this notion of toxic masculinity. It’s allowing men to feel their feelings and communicate their feelings. I think [this] is something we don’t talk about enough.

This transcript has been cut for brevity.

Written by Kailee Bryant

Kayden-Harmony Greenstein

by

Photographed

Kathryn Aurelio

by

Designed

TO ALL OF THOSE I’VE LOVED

AUTHOR’S NOTE: THIS PIECE CONTAINS A COLLECTION OF ANONYMOUS LOVE LETTERS FROM USC STUDENTS, WOVEN TOGETHER WITH MY PERSONAL REFLECTIONS OF LOVE, EXPLORING THE INTRICATE GROWTH, VULNERABILITY AND EMOTIONAL JOURNEY SURROUNDING THE PERCEPTION OF FIRST LOVE WITH A MAN.

BEFORE

“I’ve always been a hopeless romantic, emphasis on the hopeless.”

Yet, fantasizing about effortlessly falling in love with someone reluctantly transformed into a dream I hoped for less.

Two strangers. Unveiled letters. One unconditional love. That was the premise of the movie, after all, that one Netflix adaptation every girl practically swooned over when it first came out. We all wanted a love like the swoon worthy relationship found in “To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before.”

I was one of those girls. I yearned for the day my Peter Kavinsky would unexpectedly fall in love with every piece of me, fulfilling what I always imagined a “first love” should be.

I desired the innocence of teenage love and patiently waited for the day a boy could give their whole heart to me.

Just me.

Rotting in the comfort of my own sheets and sobbing over this fictional rom-com became a familiar feeling. I thought a make-believe love that could temporarily fill the void of missing romantic touch.

But, after countless situationships, ghosting, and late night “you up?” texts, I came to a stark realization: I wasn’t Lara Jean, effortlessly attracting her former crushes with written love letters. And there was no real-life Peter Kavinsky, being drawn in by my magnetic aura.

At 16 years old, I declared this version of love as nothing more than a cinematic illusion — fictional,

is from St. Louis, MO. She currently studies journalism with a minor in health innovation.

is passionate about writing about the human experience and evoking emotion from the reader.

Writer Kailee Bryant ‘26

Kailee

insatiable and simply one-sided.

I wholeheartedly believed that no man would ever truly have the capacity to fall in love. Point blank.

That was, until I met him.

Green eyes. Infectious smile. Pure soul.

We had only talked for four months, but he made each second feel like a lifetime. He checked off all of my boxes (which were minimal at the time), becoming my new standard of the perfect man.

What was once an intangible feeling of passion soon became deeply embedded in my oncehallowed heart. He gave me something I wanted, something I needed, something I craved.

What I perceived to be my first love

He laughed with me. Cried with me. Confided in me. He couldn’t stand to spend a moment without feeling the warmth of my skin. I pretended to feel the same, playing along and mimicking his affection. It was as if I was an actor reciting the lines I thought he wanted to hear.

But, soon enough, I couldn’t escape what I feared most: Unrequited love.

I became my own worst nightmare, someone on the other side, unable to return the love I was given. My long, detailed texts shrank to single words. Our touch turned into empty spaces. Adoration turned into resentment. He was just a boy who loved me. And I grew bitter because I was just a girl who loved the idea of love.

Or, maybe I was just afraid to be loved.

“Highschool crushes are funny like that. They seem so important at the moment, but we were kids at the time...”

I spent the following months in isolation, trying

to understand why something I had wanted for so long became something I was now pushing away. I had a boy practically telling me he loved me.

I had placed so much pressure on what I thought teenage love should be that when I got too close to it, I panicked and pulled away. So I cried, sinking back into the familiar abyss of my bed, wishing we could be apart, while he spent sleepless nights doing anything to keep us together.

This cycle continued, until one day, he just left. No explanation. No communication.

I was heartbroken. But, wasn’t I the one who shattered his heart first?

“My view on love has changed since we met.”

To be honest, I never really thought about how he might’ve felt after everything ended. In my mind, I assumed he had already moved on…that’s how men are, right? They mold themselves into what a girl wants, play the part for a while and then move on to someone new.

Looking back, I realize I had leaned into the stereotypical belief that men don’t know how to love. But now, I can see that my first love was there, right in front of me all along.

Girls can love. Boys can detach. Girls can detach. Boys can love.

Teenage love is complicated and messy. It comes with boundaries and silly arguments, but it also brings trust, honesty and the opportunity for growth.

The idea that men lack the capacity to love still faintly lingers in my mind. But, I know now that my preconceptions were more of a barrier, a defense mechanism to keep me from facing the truth that I was the one getting in my own way.

“You will always have a small place in my heart, but I have so much love to give…”