A Guide to the Park

Welcome to Yellowstone National Park! In this guide, you will learn about the history of America’s first national park and about the locations it is known for. This book is complete with maps from the University of Texas library and others, photos by Ansel Adams, information from Yellowstone’s official National Park Service website, and graphic elements by Sarah Olick. The graphic elements were created using elements from an original 1930s Yellowstone poster from the Federal Art Project. Please see sources pages in the back of this guide for more information.

Yellowstone National Park is named after the Yellowstone River, the major river running through the park. According to French-Canadian trappers in the 1800s, they asked the name of the river from the Minnetaree tribe, who live in what is now eastern Montana. They responded “Mi tse a-da-zi,” which literally translates as “Rock Yellow River.”

The trappers translated this into French as “Roche Jaune” or “Pierre Jaune.” In 1797, explorer-geographer David Thompson used the English translation—“Yellow Stone.”

Lewis and Clark called the Yellowstone River by the French and English forms. Subsequent use formalized the name as “Yellowstone.

Until 1994, Yellowstone (at 2.2 million acres) was the largest national park in the contiguous United States. That year Death Valley National Monument was expanded and became a national park—it has more than 3 million acres. More than half of Alaska’s national park units are larger, including Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve, which is the largest unit (13 million acres) in the National Park System.

Yellowstone is in the top five national parks for number of recreational visitors. Great Smoky Mountains National Park often has the most.

Did other national parks exist before Yellowstone? Some sources list Hot Springs in Arkansas as the first national park. Set aside in 1832, forty years before Yellowstone was established in 1872, it was actually the nation’s oldest national reservation, set aside to preserve and distribute a utilitarian resource (hot water), much like our present national forests. In 1921, an act of Congress established Hot Springs as a national park.

Yosemite became a park before Yellowstone, but as a state park. Disappointed with the results 26 years later in 1890, Congress made Yosemite one of three additional national parks, along with Sequoia and General Grant, now part of Kings Canyon. Mount Rainier followed in 1899.

As an older state park, Yosemite did have a strong influence on the founding of Yellowstone in 1872 because Congress actually used language in the state park act as a model. It’s entirely possible that Congress may have preferred to make Yellowstone a state park in the same fashion as Yosemite, had it not been for an accident of geography that put it within three territorial boundaries. Arguments between Wyoming and Montana territories that year resulted in a decision to federalize Yellowstone.

The landscape of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is the result of various geological processes over the last 150 million years. Here, Earth’s crust has been compressed, pulled apart, glaciated, eroded, and subjected to volcanism. All of this geologic activity formed the mountains, canyons, and plateaus that define the natural wonder that is Yellowstone National Park.

While these mountains and canyons may appear to change very little during our lifetime, they are still highly dynamic and variable. Some of Earth’s most active volcanic, hydrothermal (water + heat), and earthquake systems make this national park a priceless treasure. In fact, Yellowstone was established as the world’s first national park primarily because of its extraordinary geysers, hot springs, mudpots and steam vents, as well as other wonders such as the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River.

Yellowstone’s geologic story provides examples of how geologic processes work on a planetary scale. The foundation to understanding this story begins with the structure of the Earth and how this structure shapes the planet’s surface.

Earth is frequently depicted as a ball with a central core surrounded by concentric layers that culminate in the crust or outer shell. The distance from Earth’s surface to its center or core is approximately 4,000 miles. The core of the earth is divided into two parts. The mostly iron and nickel inner core (about 750 miles in diameter) is extremely hot but solid due to immense pressure. The iron and nickel

outer core (1,400 miles thick) is hot and molten. The mantle (1,800 miles thick) is a dense, hot, semi-solid layer of rock. Above the mantle is the relatively thin crust, three to 48 miles thick, forming the continents and ocean floors.

In the key principles of Plate Tectonics, Earth’s crust and upper mantle (lithosphere) is divided into many plates, which are in constant motion. Where plate edges meet, they may slide past one another, pull apart from each other, or collide into each other. When plates collide, one plate is commonly driven beneath another (subduction). Subduction is possible because continental plates are made of less dense rocks (granites) that are more buoyant than oceanic plates (basalts) and, thus, “ride” higher than oceanic plates. At divergent plate boundaries, such as midocean ridges, the upwelling of magma pulls plates apart from each other.

Many theories have been proposed to explain crustal plate movement. Scientific evidence shows that convection currents in the partially molten asthenosphere (the zone of mantle beneath the lithosphere)move the rigid crustal plates above. The volcanism that has so greatly shaped today’s Yellowstone is a product of plate movement combined with convective upwellings of hotter, semi-molten rock we call mantle plumes.

Human occupation of the greater Yellowstone area seems to follow environmental changes of the last 15,000 years. How far back is still to be determined— there are no known sites in the park that date to this time—but humans probably were not using this landscape when glaciers and a continental ice sheet covered most of what is now Yellowstone National Park. The glaciers carved out valleys with rivers that people could follow in pursuit of Ice Age mammals such as the mammoth and the giant bison. The last period of ice coverage ended 13,000–14,000 years ago, sometime after that, but before 11,000 years ago, humans were here on this landscape.

Archeologists have found physical evidence of human presence in the form of distinctive stone tools and projectile points. From these artifacts, scientists surmise that they hunted mammals and gathered berries, seeds, and plants.

As the climate in the Yellowstone region warmed and dried, the animals, vegetation, and human lifestyles also changed. Large Ice Age animals that were adapted to cold and wet conditions became extinct. The glaciers left behind layers of sediment in valleys in which grasses and sagebrush thrived, and pockets of exposed rocks that provided protected areas for aspens and fir to grow. The uncovered volcanic plateau sprouted lodgepole forests. People adapted to these changing conditions and were eating a diverse diet including medium and small animals such as deer and bighorn sheep as early as 9,500 years ago.

This favorable climate would continue more than 9,000 years. Evidence of these people in Yellowstone remained uninvestigated long after archeologists began excavating sites elsewhere in North America. Archeologists used to think high-elevation regions such as Yellowstone were inhospitable to humans and, thus, did little exploratory work in these areas. However, park superintendent Philetus W. Norris (1877–82) found artifacts in Yellowstone and sent them to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Today, archeologists study environmental change as a tool for understanding human uses of areas such as Yellowstone.

More than 1,850 archeological sites have been documented in Yellowstone National Park, with the majority dating to the Archaic period. Sites contain evidence of successful hunts for bison, sheep, elk, deer, bear, cats, and wolves. Campsites and trails in Yellowstone also provide evidence of early use. Some of the trails used in the park today have likely been used by people since the Paleoindian period.

Some of the historic peoples from this area, such as the Crow and Sioux, arrived sometime during the 1500s and around 1700, respectively. Prehistoric vessels known as “Intermountain Ware” have been found in the park and surrounding area, and these link the Shoshone to the area as early as approximately 700 years ago.

Although Yellowstone had been thoroughly tracked by tribes and trappers, in the view of the nation at large it was really “discovered” by a series of formal expeditions. The first organized attempt came in 1860 when Captain William F. Raynolds led a military expedition, but this group was unable to explore the Yellowstone Plateau because of late spring snow. The Civil War preoccupied the government during the next few years. Immediately after the war, several explorations were planned, but none actually got underway. The crowning achievement of the returning expeditions was helping to save Yellowstone from private development. Nathaniel P. Langford and several of his companions promoted a bill in Washington in late 1871 and early 1872 that drew upon the precedent of the Yosemite Act of 1864, which reserved Yosemite Valley from settlement and entrusted it to the care of the state of California. To permanently close to settlement an expanse of the public domain the size of Yellowstone would depart from the established policy of transferring public lands to private ownership. But the wonders of Yellowstone—shown through Jackson’s photographs, Moran’s paintings, and Elliot’s sketches—had captured the imagination of Congress. Thanks to their reports, the United States Congress established Yellowstone National Park just six months after the Hayden Expedition. On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act into law. The world’s first national park was born.

The Yellowstone National Park Protection Act says “the headwaters of the Yellowstone River … is hereby reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale … and dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuringground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” In an era of expansion, the federal government had the foresight to set aside land deemed too valuable in natural wonders to develop.

National parks clearly needed coordinated administration by professionals attuned to the special requirements of these preserves. The management of Yellowstone from 1872 through the early 1900s helped set the stage for the creation of an agency whose sole purpose was to manage the national parks. Promoters of this idea gathered support from influential journalists, railroads likely to profit from increased park tourism, and members of Congress. The National Park Service Organic Act was passed by Congress and approved by President Woodrow Wilson on August 25, 1916.

Yellowstone’s first rangers, which included veterans of Army service in the park, became responsible for Yellowstone in 1918. The park’s first superintendent under the new National Park Service was Horace M. Albright, who served simultaneously as assistant to Stephen T. Mather, Director of the National Park Service. Albright established a management framework that guided administration of Yellowstone for decades.

Change and controversy have occurred in Yellowstone since its inception, in the last three decades many issues have arises involving natural resources.

One issue was the threat of water pollution from a gold mine outside the northeast corner of the park. Among other concerns, the New World Mine would have put waste storage along the headwaters of Soda Butte Creek, which flows into the Lamar River and then the Yellowstone River.

After years of public debate, a federal buyout of the mining company was authorized in 1996.

In an effort to resolve other park management issues, Congress passed the National Parks Omnibus Management Act in 1998. This law requires using high quality science from inventory, monitoring, and research to understand and manage park resources.

Park facilities are seeing some improvements due to a change in funding. In 1996, as part of a pilot program, Yellowstone National Park was authorized to increase its entrance fee and retain 80% of the fee for park projects. (Previously, park entrance fees did not specifically fund park projects.) In 2004, the US Congress extended this program until 2015 under the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act. Projects funded in part by this program include a major renovation of Canyon Visitor Education Center, campground and amphitheater upgrades, preservation of rare documents, and studies on bison.

The legacy of those who worked to establish Yellowstone National Park in 1872 was far greater than simply preserving a unique landscape. This one act has led to a lasting concept—the national park idea. This idea conceived wilderness to be the inheritance of all people, who gain more from an experience in nature than from private exploitation of the land.

The national park idea was part of a new view of the nation’s responsibility for the public domain. By the end of the 1800s, many thoughtful people no longer believed that wilderness should be fair game for the first person who could claim and plunder it. They believed its fruits were the rightful possession of all the people, including those yet unborn. Besides the areas set aside as national parks, still greater expanses of land were placed into national forests and other reserves so the United States’ natural wealth— in the form of lumber, grazing, minerals, and recreation lands—would not be consumed at once by the greed of a few, but would perpetually benefit all.

The preservation idea spread around the world. Scores of nations have preserved areas of natural beauty and historical worth so that all humankind will have the opportunity to reflect on their natural and cultural heritage and to return to nature and be spiritually reborn. Of all the benefits resulting from the establishment of Yellowstone National Park, this may be the greatest.

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone is roughly 20 miles long, measured from the Upper Falls to the Tower Fall area. The canyon was formed by erosion as Yellowstone River flowed over progressively softer, less resistant rock.

The 109-foot (33.2-m) Upper Falls is upstream of the Lower Falls and can be seen from the Brink of the Upper Falls Trail and from Upper Falls Viewpoints. The 308-foot (93.9-m) Lower Falls can be seen from Lookout Point, Red Rock Point, Artist Point, Brink of the Lower Falls Trail, and from various points on the South Rim Trail. The volume of water flowing over the falls can vary from 63,500 gallons (240,374 l)/second at peak runoff in the spring to 5,000 gallons (18,927 l)/second in the autumn.

A third falls is located in the canyon between the Upper and Lower falls. Cascade Creek cascades into the canyon as Crystal Falls. It can be seen from the South Rim Trail just east of the Upper Falls Viewpoints area.

With a peak elevation of 10,219 feet (3,115 m) and panoramic views for about 20 to 50 miles (32 to 80 km), Mount Washburn is a popular day-hiking destinations. It is located just a few miles north of Canyon Village. Mount Washburn is the remnant of volcanic activity that took place long before the formation of the present canyon and named for General Henry Washburn, leader of the 1870 Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition.

At the top, check out interpretive exhibits inside the base of a fire lookout and enjoy the view (you can also watch views from Mount Washburn from two webcams).

In addition to being a popular hiking destination, Mount Washburn is one of three fire lookout stations in Yellowstone. It is staffed from mid-June until the fire season ends, during which time the staff watch for signs of fire.

Hayden Valley is a great place to view wildlife. Grizzly bears may be seen in the spring and early summer preying upon newborn bison and elk calves. Bison are often seen in the spring all the way through the fall rut. Coyotes and foxes are often seen in the valley. Ducks, geese, and American white pelicans cruise the river, while a variety of shore birds may be seen in the mud flats at Alum Creek. Keep an eye out for bald eagles, northern harriers, and sandhill cranes.

Large volcanic eruptions have occurred in Yellowstone approximately every 600,000 years. The most recent of these erupted from two large vents, one near Old Faithful and one just north of Fishing Bridge. Ash from this huge explosion—1,000 times the size of Mount St. Helens—has been found all across the continent. The magma chamber then collapsed, forming a large caldera filled partially by subsequent lava flows. Part of this caldera is the 136-square mile (352.2-square km) basin of Yellowstone Lake. The original lake was 200 feet (61 m). higher than the presentday lake, extending northward across Hayden Valley to the base of Mt. Washburn.

The original bridge was built in 1902. It was a rough-hewn corduroy log bridge with a slightly different alignment than the current bridge. The existing bridge was built in 1937. Fishing Bridge was historically a tremendously popular place to fish. Angling from the bridge was quite good, due to the fact that it was a major spawning area for cutthroat trout. However, because of the decline of the cutthroat population (in part, a result of this practice), the bridge was closed to fishing in 1973.

The hydrothermal features at Mud Volcano are primarily mudpots and fumaroles because the area is situated on a perched water system with little water available. Thanks to thermophiles, the vapors are rich in sulfuric acid that breaks the surrounding rock down into clay. Hydrogen sulfide gas is present deep in the earth at Mud Volcano. As this gas combines with water and the sulfur is metabolized by cyanobacteria, a solution of sulfuric acid is formed that dissolves the surface soils to create pools and cones of clay and mud. Along with hydrogen sulfide, steam, carbon dioxide, and other gases explode through the layers of mud. A series of shallow earthquakes associated with the volcanic activity in Yellowstone struck this area in 1978. Soil temperatures increased to nearly 200°F (93°C).

Hayden Valley is located six miles north of Fishing Bridge Junction and Pelican Valley is situated three miles to the east of the junction. These two vast valleys comprise some of the best habitat in the lower 48 states for viewing wildlife like grizzly bears, bison, and elk.

Hayden Valley was once filled by an arm of Yellowstone Lake. Therefore, it contains fine-grained lake sediments that are now covered with glacial till left from the most recent glacial retreat 13,000 years ago. Because the glacial till contains many different grain sizes, including clay and a thin layer of lake sediments, water cannot percolate readily into the ground. This is why Hayden Valley is marshy and has little encroachment of trees.

Two different trailheads lead to Fairy Falls, which at 200 feet (61 m) high is one of Yellowstone’s most spectacular waterfalls.

The northern trailhead starts at the end of the Fountain Flat Drive and follows an old road across meadows and near hydrothermal features. This is a 6.7-mile (10.7-km) hike.

The southern trailhead starts at the Fairy Falls parking area and follows an old road along the edge of the Midway Geyser Basin. This is a 5.4-mile (8.6-km) hike. Also along this trail is the side-hike up to the Grand Prismatic Overlook Trail to a wonderful view of Grand Prismatic Spring and the rest of the Midway Geyser Basin.

The Firehole River starts south of Old Faithful, runs through the Upper Geyser Basin northward to join the Gibbon River and form the Madison River. The Madison joins the Jefferson and the Gallatin rivers at Three Forks, Montana, to form the Missouri River.

The Madison is a blue-ribbon fly-fishing stream with brown and rainbow trout and mountain whitefish. Meanwhile, the Firehole River is world-famous among anglers for its pristine beauty and abundant brown, brook, and rainbow trout.

There are a lot of hydrothermal wonders to discover in this region, from small geysers and fumaroles to more wellknown mudpots and hot springs. This is also a popular area in the summertime, so be prepared for crowded parking areas, or plan to visit during off-hours.

Terrace Springs is a small thermal area just north of Madison Junction where a short boardwalk leads out to hot springs.

Fountain Paint Pot is a popular stop where you can take in all four of the park’s major hydrothermal features: fumaroles, geysers, hot springs, and mudpots. Fountain Paint Pot is one of the more famous mudpots in the park.

Next to Fountain Paint Pot is the Firehole Lake Drive, one of the park’s nice little side-drives. This drive leads you past many hydrothermal features, including Great Fountain Geyser and White Dome Geyser.

Further to the south is Midway Geyser Basin, home to perhaps the most photographed hot spring: Grand Prismatic Spring. Next to Grand Prismatic Spring is the massive steaming crater of Excelsior Geyser, which back in the late 1800s was still erupting over 300 feet (91 m) into the air. Today, Excelsior Geyser is considered dormant.

Yellowstone’s first superintendents struggled with poaching, vandalism, squatting and other problems. In 1886, US Army soldiers marched into Mammoth Hot Springs at the request of the Secretary of the Interior and took charge of Yellowstone. Soldiers oversaw Fort Yellowstone’s construction—sturdy red-roofed buildings still in use today as the Albright Visitor Center, offices, and employee housing.

Walk on boardwalks above the steaming hydrothermal features or take a drive around the vibrant travertine terraces. In the winter, ski or snowshoe among the whiffs of sulfur along the Upper Terraces.

Norris Geyser Basin is the hottest, oldest, and most dynamic of Yellowstone’s thermal areas. The highest temperature yet recorded in any geothermal area in Yellowstone was measured in a scientific drill hole at Norris: 459°F (237°C) just 1,087 feet (326 meters) below the surface! There are very few thermal features at Norris under the boiling point (199°F at this elevation).

Norris shows evidence of having had thermal features for at least 115,000 years. The features in the basin change daily, with frequent disturbances from seismic activity and water fluctuations. The vast majority of the waters at Norris are acidic, including acid geysers which are very rare. Steamboat Geyser, the tallest geyser in the world at 300–400 feet (91–122 m) and Echinus Geyser (pH 3.5 or so) are the most popular features.

The basin consists of two areas: Porcelain Basin and the Back Basin. Porcelain Basin is barren of trees and provides a sensory experience in sound, color, and smell; a 3/4-mile (1.2-km) bare ground and boardwalk trail accesses this area. Back Basin is more heavily wooded with features scattered throughout the area. A 1.5-mile (2.4-km) trail of boardwalks and bare ground encircles this part of the basin.

The area was named after Philetus W. Norris, the second superintendent of Yellowstone, who provided the first detailed information about the thermal features.

Norris Geyser Basin sits on the intersection of major faults. The Norris–Mammoth Corridor is a fault that runs from Norris north through Mammoth to the Gardiner, Montana, area. The Hebgen Lake fault runs from northwest of West Yellowstone, Montana, to Norris Geyser Basin. This fault experienced an earthquake in 1959 that measured 7.4 on the Richter scale (sources vary on exact magnitude between 7.1 and 7.8).

These two faults intersect with a ring fracture that resulted from the Yellowstone Caldera of 600,000 years ago. These faults are the primary reason that Norris Geyser Basin is so hot and dynamic. The Ragged Hills around parts of Back Basin and are thermally altered glacial moraines. As glaciers receded, the underlying thermal features began to express themselves once again, melting remnants of the ice and causing masses of debris to be dumped. These debris piles were then altered by steam and hot water flowing through them.

Gibbon Falls lies on the caldera boundary as does Virginia Cascades.

Located just north of Norris on the Norris–Mammoth section of the Grand Loop Road, Roaring Mountain is a large, acidic thermal area that contains many fumaroles. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the number, size, and power of the fumaroles was much greater than today.

The Gibbon River flows from Wolf Lake through the Norris area and meets the Firehole River at Madison Junction to form the Madison River. Both cold and hot springs are responsible for the majority of the Gibbon River’s flow.

Brook trout, brown trout, grayling, and rainbow trout live in the Gibbon River.

A three-mile (4.8-km) section of the old road takes visitors past 60-foot (18.3-m) high Virginia Cascades. This cascading waterfall is formed by the very small (at that point) Gibbon River. The drive may be open to cross-country skiing in the winter.

This 84-foot (26-m) waterfall tumbles over remnants of the Yellowstone Caldera rim. The rock wall on the opposite side of the road from the waterfall is the inner rim of the caldera.

The Norris Geyser Basin Museum is one of the park’s original trailside museums built in 1929–30. The museum is a National Historic Landmark. Its distinctive stone-andlog architecture became a prototype for park buildings throughout the country known as “parkitecture” (Fishing Bridge Museum and Madison Museum date from the same time period and are of the same style).

Exhibits on geothermal geology, hydrothermal features, and life in thermal areas were installed in in the 1960s and in 1995. The building consists of two wings separated by an open-air breezeway. An information desk is staffed by National Park Service interpreters. An facility of matching architectural style houses a bookstore.

Artists Paintpots, Beryl Spring, and Monument Geyser Basin are all areas where you can experience hydrothermal activity. Beryl Spring is found right at a pullout along the Gibbon River, making it very accessible.

Artists Paintpots is a small but lovely thermal area just south of Norris Junction. A one-mile (1.6-km) lollipop loop trail takes you to colorful hot springs, two large mudpots, and through a section of forest burned in 1988.

Monument Geyser Basin is at the top of a ridge, making it a bit more strenuous to reach. However, the relative solitude and unique hydrothermal features make the trek worthwhile.

Watching Old Faithful Geyser erupt is a Yellowstone National Park tradition. People from all over the world have journeyed here to watch this famous geyser. The park’s wildlife and scenery might be as well-known today, but it was the unique thermal features like Old Faithful Geyser that inspired the establishment of Yellowstone as the world’s first national park in 1872.

Old Faithful is one of nearly 500 geysers in Yellowstone and one of six that park rangers currently predict. It is uncommon to be able to predict geyser eruptions with regularity and Old Faithful has lived up to its name, only lengthening the time between eruptions by about 30 minutes in the last 30 years.

Thermal features change constantly and it is possible Old Faithful may stop erupting someday. Geysers and other thermal features are evidence of ongoing volcanic activity beneath the surface and change is part of this natural system. Yellowstone preserves the natural geologic processes so that visitors may continue to enjoy this natural system.

Watch eruptions from the Old Faithful viewing area or along the boardwalks that weave around the geyser and through the Upper Geyser Basin.

Evidence of the geological forces that have shaped Yellowstone are found in abundance in this district. The hills surrounding Old Faithful and the Upper Geyser Basin are reminders of Quaternary rhyolitic lava flows. These flows, occurring long after the catastrophic eruption of 600,000 years ago, flowed across the landscape like stiff mounds of bread dough due to their high silica content.

Evidence of glacial activity is common, and it is one of the keys that allows geysers to exist. Glacier till deposits underlie the geyser basins providing storage areas for the water used in eruptions. Many landforms, such as Porcupine Hills north of Fountain Flats, are comprised of glacial gravel and are reminders that as recently as 13,000 years ago, this area was buried under ice.

Signs of the forces of erosion can be seen everywhere, from runoff channels carved across the sinter in the geyser basins to the drainage created by the Firehole River. Mountain building is evident as you drive south of Old Faithful, toward Craig Pass. Here the Rocky Mountains reach a height of 8,262 feet (2518 m), dividing the country into two distinct watersheds.

The Old Faithful Inn was designed by Robert C. Reamer, who wanted the asymmetry of the building to reflect the chaos of nature. It was built during the winter of 1903–1904. The Old Faithful Inn is one of the few remaining log hotels in the United States. It is a masterpiece of rustic architecture in its stylized design and fine craftsmanship. Its influence on American architecture, particularly park architecture, was immeasurable.

The building is a rustic log and wood-frame structure with gigantic proportions: nearly 700 feet (213 m) in length and seven stories high. The lobby of the hotel features a 65foot (20-m) ceiling, a massive rhyolite fireplace, and railings made of contorted lodgepole pine. Stand in the lobby and look up at the exposed structure, or walk up a gnarled log staircase to one of the balconies. Wings were added to the hotel in 1915 and 1927, and today there are 327 rooms available to guests in this National Historic Landmark.

Yellowstone, as a whole, possesses close to 60 percent of the world’s geysers. The Upper Geyser Basin is home to the largest numbers of this fragile feature found in the park. Within one square mile there are at least 150 of these hydrothermal wonders. Of this remarkable number, only five major geysers are predicted regularly by the naturalist staff. They are Castle, Grand, Daisy, Riverside, and Old Faithful. There are many frequent, smaller geysers to be seen and marveled at in this basin as well as numerous hot springs and one recently developed mudpot (if it lasts).

Just north of Old Faithful are two smaller basins that are worth a visit. Both basins have parking lots, or are accessible by foot via the trail network through the Upper Geyser Basin.

Black Sand Basin is northwest of Old Faithful and has several enjoyable hydrothermal features, from the rather active Cliff Geyser to the chromatic Rainbow Pool and Sunset Lake.

Further north of Old Faithful is Biscuit Basin, named after the biscuit-shaped geyserite formations that can still be seen around parts of the majestic Sapphire Pool. There are also some enjoyable surprises along the boardwalk like Jewel Geyser, as well as the start of the Mystic Falls Trail at the far end of the boardwalk loop.

This geyser basin, though small in size compared to its companions along the Firehole River, holds large hydrothermal wonders.

First is Excelsior Geyser Crater, where a 200 feet x 300 feet (61 m x 91 m) hot spring steams within and constantly discharges more than 4,000 gallons (15,142 l) of water per minute into the Firehole River.

Next is the chromatic wonder of Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone’s largest hot springs. This feature is 370 feet (113 m) in diameter and more than 121 feet (37 m) in depth.

Lone Star Geyser erupts about every three hours. There is a logbook, located in a cache near the geyser, for observations of geyser times and types of eruptions. This is a 4.8 mile (7.7 km), easy there-and-back hike or bike that follows the Firehole River to the geyser. The trailhead is east of Kepler Cascades pullout, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) southeast of the Old Faithful overpass on Grand Loop Road. Lone Star erupts 30–45 feet (9–14 m) about every three hours.

There are two waterfalls that are relatively easy to get to in this region. Kepler Cascades is visible from a viewing platform at a pullout south of Old Faithful along the Grand Loop Road.

Mystic Falls is reached via a delightful day hike that starts at the far end of the Biscuit Basin boardwalk loop. It is either an easy there-and-back hike to the base of the waterfall, or you can make a loop of the hike, ascending the nearby hillside for sweeping views back across the Upper Geyser Basin.

The 132-foot (40-m) drop of Tower Creek, framed by eroded volcanic pinnacles has been documented by park visitors from the earliest trips of Europeans into the Yellowstone region. Its idyllic setting has inspired numerous artists, including Thomas Moran. His painting of Tower Fall played a role in the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872.

The nearby Bannock Ford on the Yellowstone River was an important travel route for early Native Americans, as well as for early European visitors and miners up to the late 19th century.

Lamar Valley is an excellent place to view wildlife, with it being one of the major summer grounds for bison and elk, which attracts predators like wolves and grizzly bears.

Remember: Do not approach or encircle bears or wolves on foot within 100 yards (91 m) or other wildlife within 25 yards (23 m). Always maintain a safe distance from all wildlife. Each year, park visitors are injured by wildlife when approaching too closely.

Evidence of the geological forces that have shaped Yellowstone are found in abundance in this district. The hills surrounding Old Faithful and the Upper Geyser Basin are reminders of Quaternary rhyolitic lava flows. These flows, occurring long after the catastrophic eruption of 600,000 years ago, flowed across the landscape like stiff mounds of bread dough due to their high silica content.

Evidence of glacial activity is common, and it is one of the keys that allows geysers to exist. Glacier till deposits underlie the geyser basins providing storage areas for the water used in eruptions. Many landforms, such as Porcupine Hills north of Fountain Flats, are comprised of glacial gravel and are reminders that as recently as 13,000 years ago, this area was buried under ice.

Signs of the forces of erosion can be seen everywhere, from runoff channels carved across the sinter in the geyser basins to the drainage created by the Firehole River. Mountain building is evident as you drive south of Old Faithful, toward Craig Pass. Here the Rocky Mountains reach a height of 8,262 feet (2518 m), dividing the country into two distinct watersheds.

Petrified Tree, located near the Lost Lake trailhead, is an excellent example of an ancient redwood, similar to many found on Specimen Ridge, that is easily accessible to park visitors. Specimen Ridge, located along the Northeast Entrance Road east of Tower Junction, contains the largest concentration of petrified trees in the world. There are also excellent samples of petrified leaf impressions, conifer needles, and microscopic pollen from numerous species no longer growing in the park. Specimen Ridge provides a superb window into the distant past when plant communities and climatic conditions were much different than today.

The Bannock Trail, once used by Native Americans to access the buffalo plains east of the park from the Snake River plains in Idaho, was extensively used from approximately 1840 to 1876. A lengthy portion of the trail extends through from the Blacktail Plateau (closely paralleling or actually covered by the existing road) to where it crosses the Yellowstone River at the Bannock Ford upstream from Tower Creek. From the river, the trail’s main fork ascends the Lamar River splitting at Soda Butte Creek. From there, one fork ascends the creek before leaving the park. Traces of the trail can still be plainly seen in various locations, particularly on the Blacktail Plateau and at the Lamar-Soda Butte confluence.

Absaroka volcanics, glaciation, and erosion have left features as varied as Specimen Ridge’s petrified trees to the gorges along the Yellowstone River’s Black Canyon and the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River.

Mt. Washburn and the Absaroka Range are both remnants of ancient volcanic events that formed the highest peaks in the area. Ancient eruptions, perhaps 45–50 million years ago, buried the forests of Specimen Ridge in ash and debris flows. The columnar basalt formations near Tower Fall, the volcanic breccias of the towers themselves, and numerous igneous outcrops all reflect the volcanic history.

Later, glacial events scoured the landscape, exposing the stone forests and leaving evidence of their passage across the area. The glacial ponds and huge boulders (erratics) between the Lamar and Yellowstone rivers are remnants left by the retreating glaciers. Lateral and terminal moraines are common in these areas. Such evidence can also be found in the Hellroaring and Slough creek drainages, on Blacktail Plateau, and in the Lamar Valley.

The eroding power of running water has been at work here for many millions of years. The pinnacles of Tower Fall, the exposed rainbow colors of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River at Calcite Springs, and the gorge of the Black Canyon all are due, at least in part, to the forces of running water and gravity.

In the Lamar River Canyon lie exposed outcrops of gneiss and schist which are among the oldest rocks known in Yellowstone, perhaps more than two billion years old. Little is known about their origin due to their extreme age. Through time, heat and pressure have altered these rocks from their original state, further obscuring their early history. Only in the Gallatin Range are older outcrops found within the boundaries of the park.

West Thumb Geyser Basin, including Potts Basin to the north, is the largest geyser basin on the shores of Yellowstone Lake. The heat source of the hydrothermal features in this location is thought to be relatively close to the surface—only 10,000 feet (3000 m) down!

The West Thumb of Yellowstone Lake was formed by a large volcanic explosion that occurred approximately 150,000 years ago (125,000–200,000). The resulting collapsed volcano later filled with water forming an extension of Yellowstone Lake. The West Thumb is about the same size as another famous volcanic caldera, Crater Lake in Oregon, but much smaller than the great Yellowstone Caldera which formed 600,000 years ago. It is interesting to note that West Thumb is a caldera within a caldera.

Ring fractures formed as the magma chamber bulged up under the surface of the earth and subsequently cracked, releasing the enclosed magma. This created the source of heat for the West Thumb Geyser Basin today.

The hydrothermal features at West Thumb are found not only on the lake shore, but extend under the surface of the lake as well. Several underwater geysers were discovered in the early 1990s and can be seen as slick spots or slight bulges in the summer. During the winter, the underwater thermal features are visible as melt holes in the icy surface of the lake. The ice averages about three feet thick during the winter.

Large volcanic eruptions have occurred in Yellowstone on an approximate interval of 600,000 years. Part of this caldera is the 136-square mile (352-square km) basin of Yellowstone Lake. The original lake was 200 feet (61 m) higher than the present-day lake, extending northward across Hayden Valley to the base of Mount Washburn. Members of the 1870 Washburn party noted that Yellowstone Lake was shaped like “a human hand with the fingers extended and spread apart as much as possible,” with the large west bay representing the thumb. In 1878, however, the Hayden Survey used the name West Arm for the bay. West Bay was also used. Norris’ maps of 1880 and 1881 used West Bay or Thumb. During the 1930s, park personnel attempted to change the name back to West Arm, but West Thumb remains the accepted name.

In the southwest part of the park, accessible via dirt roads outside of the park, is the Bechler region. This is a unique corner of the park, with the lowest visitation and a wetter environment than the rest of the park. This is an ideal location for those with an adventurous spirit and a desire to hike and backcountry camp.

The graphic elements in this book were created using elements from a 1938 poster promoting Yellowstone National Park. The original poster was created for the Federal Art Project, which was part of the Works Progress Association put into place by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. The original poster is credited to artist C. Don Powell, but individual artists of posters in the series remain unknown.

Pages 4-5: Maps of United States National Parks and Monuments “National Park System Map” (University of Texas Libraries)

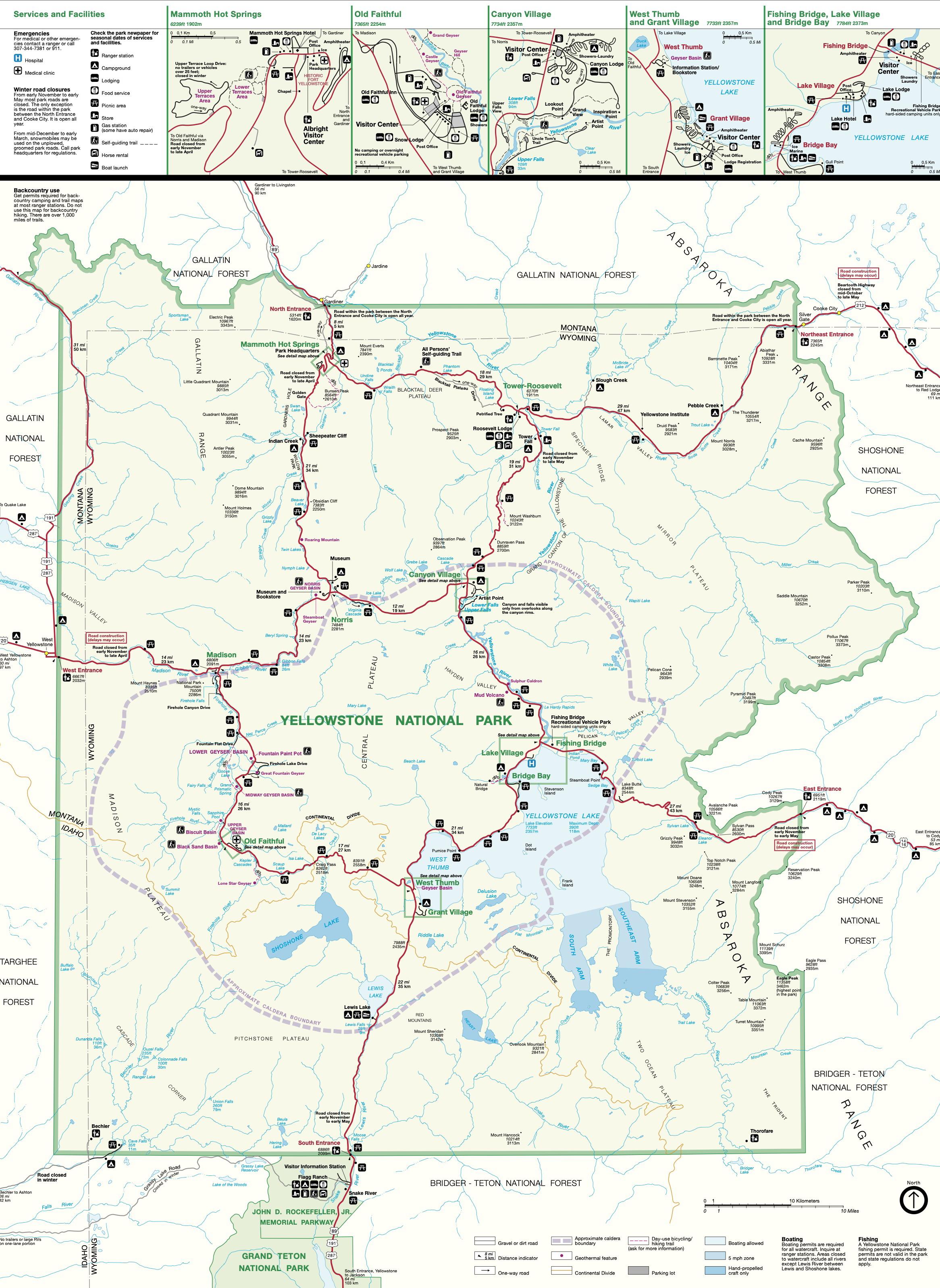

Page 34: Maps of United States National Parks and Monuments “Yellowstone National Park” (University of Texas Libraries)

Page 36: Maps of United States National Parks and Monuments “Yellowstone National Park - Canyon Village” (University of Texas Libraries)

Page 42: Maps of United States National Parks and Monuments “Yellowstone National Park - Fishing Bridge, Lake Village and Bridge Bay” (University of Texas Libraries)

Page 49: Maps of United States National Parks and Monuments “Yellowstone National Park - Madison Plateau” (University of Texas Libraries)

Page 54: Maps of United States National Parks and Monuments “Yellowstone National Park - Mammoth Hot Spring” (University of Texas Libraries)

Page 58: Figure 1 “The 2018 reawakening and eruption dynamics of Steamboat Geyser, the world’s tallest active geyser” (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America)

Page 68: Maps of United States National Parks and Monuments “Yellowstone National Park - Old Faithful” (University of Texas Libraries)

Page 80: Yellowstone National Park Maps “TowerRoosevelt to Northeast Entrance Route” (Best of Yellowstone)

Page 90: Maps of United States National Parks and Monuments “Yellowstone National Park - West Thumb and Grant Village” (University of Texas Libraries)

Page 37: Ansel Adams “Yellowstone Falls” (ourdocuments.gov)

Page 43: Ansel Adams “Yellowstone Lake - Hot Springs Overflow, Yellowstone National Park” (Wikimedia Commons)

Page 48: Ansel Adams “Firehole River, Yellowstone National Park (Wikimedia Commons)

Page 55: Ansel Adams “Jupiter Terrace - Fountain Geyser Pool, Yellowstone National Park” (Wikimedia Commons)

Page 59: Ansel Adams “Barren tree trunks rising from water in foreground, stream rising from mountains in background” (Wikimedia Commons)

Page 69: Ansel Adams “Old Faithful Geyser, Yellowstone National Park” (Wikimedia Commons)

Page 81: Ansel Adams “Mountains - Northeast Portion, Yellowstone National Park” (Wikimedia Commons)

Page 91: Ansel Adams “Central Geyser Basin, Yellowstone National Park” (Wikimedia Commons)

Page 99: C. Don Powell “Yellowstone National Park, Ranger Naturalist Service” (Saturday Evening Post)

Page 8: Yellowstone “Frequently Asked Questions” (nps.gov)

Page 10: Yellowstone “Frequently Asked Questions: History” (nps.gov)

Pages 17-19: Yellowstone “Geology” (nps.gov)

Pages 21-23: Yellowstone “The Earliest Humans in Yellowstone” (nps.gov)

Page 25: Yellowstone “Birth of a National Park” (nps.gov)

Pages 25-27: Yellowstone “Park History” (nps.gov)

Pages 29-31: Yellowstone “Modern Management” (nps.gov)

Pages 38-41: Yellowstone “Canyon Village and the Grand Canyon” (nps.gov)

Pages 44-47: Yellowstone “Fishing Bridge, Lake, and Bridge Bay” (nps.gov)

Pages 50-52: Yellowstone “Madison and the West” (nps.gov)

Page 56: Yellowstone “Mammoth Hot Springs and the North (nps.gov)

Pages 60-67: Yellowstone “Norris Geyser Basin” (nps.gov)

Pages 70-79: Yellowstone “Old Faithful” (nps.gov)

Pages 82-89: Yellowstone “Tower-Roosevelt and the Northeast” (nps.gov)

Pages 92-94: Yellowstone “West Thumb, Grant, and the South” (nps.gov)