by Jaime Harker

In 1993, I moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to start a Ph.D. program. Temple University was my official institution, but Giovanni’s Room was my chosen home, an out, proud gay bookstore at the corner of 12th and Pine. I bought political tees there, including one of my all-time favorites— Barbara Kruger’s iconic print, “Your Body Is A Battleground.” A woman’s face is split down the middle— black and white, one half in negative—with the words in red across her forehead, nose, and chin. Interspersed were smaller words in red: “Support Legal Abortion, Birth Control, and Women’s Rights.” I wore that tee so much that eventually, it disintegrated in the washer.

That shirt was already seen as a bit retro when I wore it in 1993. Barbara Kruger thought it was retro when she made it for a March on Washington in 1989. Hadn’t we already dealt with this in 1973? Why were we revisiting this now?

The irony of the current moment really cannot be overstated; fifty years after Roe v. Wade, two years after its repeal, Barbara Kruger’s print is more relevant than ever. Women’s bodies, trans bodies, queer bodies, and black and brown bodies ARE battlegrounds: a proxy battle for the body politic.

the COVID-19 pandemic, infection, plague, sickness, and disease metaphors are especially poignant ways to make negative claims about political and cultural adversaries.

In an election year, the body politic as a programmatic theme felt like a perfect lens to remember past battles, understand the present, and imagine a better future. We are pleased to see how our programming has come together for the coming year, with exciting scholars, inspiring artists, and opportunities for our students to engage, advocate, and dream.

Our programmatic theme this year is “the body politic.” We are thinking, of course, about the ways that the body is governed and shaped by policy and politics. We also mean to examine the ways that a people or a population are conceived of as a political body. The population of a particular nation is imagined as an entity or self with parts and with borders, and sometimes with a head that rules the rest. The body politic introduces metaphors of the body into our understanding of governing politics (e.g. branches of government imagined as arms), and we can trace these ideas in contemporary discourse, particularly in metaphors of sickness. Accusations of “woke” culture or diversity infecting families, schools, or the culture in general have become commonplace. Coming off the first years of

Our cover story focuses on the ways popular culture tracks emerging frustrations and potential revolutions through metaphors and images and celebrates cultural texts that allow us to imagine more feminist and queer futures.

Take a look at our upcoming events for Sarahfest, in which the body politic is imagined as art and activism that crosses boundaries of home, genre, and community: a photographic exhibit on homelessness by Chuck Steffen; a performance by country singer-songwriter Julie Williams whose songs tell the stories she wished she had heard as a mixed race child; and Caroline Young, whose Sarahest residency will explore the intersections among art, interaction, and the idea of pure expression All ask probing questions about the body politic and who is imagined as a member of that body. We hope you will plan to attend our annual lecture series and see how scholars Briona Simone Jones, Ela Przybylo, Jack Jen Gieseking, and Hil Malatino are expanding our understanding of under-researched genders and sexualities, broadening the body politic. We also invite you to attend the Isom Student Gender Conference, where the next generation will inspire us with their passion, brilliance, and insight.

No matter how off-putting the election season may be, the body politic is truly all of us, and we hope, in our own investigations and celebrations, to inspire you to make your own distinctive contribution to it.

by Jaime Harker

As the number of faculty and classes offered by the Sarah Isom Center grow, more students are minoring in Gender Studies. We are thrilled by this development. This year, to provide more support, information, communication, and community building to Gender Studies minors–and to attract more students to the minor–Dr. Julie R. Enszer, an Instructional Assistant Professor, has agreed to be the undergraduate coordinator. Dr. Enszer will communicate directly with undergraduate minors about events and opportunities through the Isom Center and will offer a series of supplemental educational events for Gender Studies minors to support them in college life and beyond. More information about the events is below. Please encourage interested students to consider the Gender Studies minor and share information with students about our special programs this year for undergraduate Gender Studies minors. We are very much looking forward to further growth and development of undergraduate programs at the Isom Center.

This academic year (2024-25), the Sarah Isom Center is offering three workshops just for Gender Studies minors. Mark your calendars today - and plan to join us for fun, conversation, community, and conviviality. These events will be on Zoom and all Gender Studies minors are invited (and are welcome to bring friends!)

September 26 • 6 pm • Zoom thinking about grad School or law School?

Join us to talk with recent graduates about their experiences applying for, being accepted to, and starting law school and grad school.

February 3 • 6 pm • Zoom writing perSonal StatementS: a workShop

Laboring over grad school or professional school applications? Join us for a discussion of personal statements–and bring yours to share for feedback, editing, and cheers from friends and colleagues who are rooting for you and your future!

april 7 • 6 pm • Zoom FeminiSt Finance: money in the world

Thinking about your financial future? Join us for a lively discussion of financial issues, including negotiating salaries, managing finances in your first job, and more. We’re here to take the mystery out of money for Gender Studies students.

Congratulations to all of our graduates from the past year with a minor in Gender Studies!

Summer 23

• Hanna Kasica (BA - Psychology)

• Timothy Spivey (BSJC - Criminal Justice)

december 23

• Katelyn Hensiek (BA - Psychology)

• Ashley Lutke (BA - English)

• Mallory Sanderson (BA - Psychology)

may 24

• Molly Acheson (BA - Accountancy)

• Hannah Barnett (BA - Psychology)

• Ulysses Bentley (BMDS)

• Jametrice Blanchard (BA - Political Science)

• Galin Burton (BA - Allied Health Studies)

• Maisie Carey (BA - Psychology)

• Kaylah Dowell (BA - Chinese)

• Kayla Ibarra (BA - Psychology)

• Audrey Lowes (BA - Psychology)

• Brittany McMullen (BA - Psychology)

• Henry Teal (BA - Psychology)

• Taylor Unkart (BA - Psychology)

• Grace Whitworth (BA - Psychology)

• Olivia Womack (BSLS - Law Studies)

graduate minorS

• Michelle Bright (MFA - Southern Studies)

• Madeline Burdine (MA - Sociology)

• Laura Conte (MA - Southern Studies)

• Kimberly Kotel (Ph.D. - English)

• Kara Russell (Ph.D. - English)

The Isom Center's end of year reception was held on Thursday, May, 2, 2024. As part of the reception, graduating undergraduate minors were recognized, including Olivia Womack (above) and (l-r) Audrey Lowes, Jametrice Blanchard, Kaylah Dowell, and Mallorie Uselton (August 24).

by LesLie DeLassus

Hey y’all! We are excited to introduce Dr. Pria Williams, Instructional Assistant Professor of Theatre and Film and Gender Studies. A former Isom Center fellow and Instructional Assistant Professor of Theatre Arts, Dr. Williams joined the Isom Center faculty in Spring of 2024. I had the opportunity to get to know more about Pria's fascinating academic and creative work, which I am happy to share with everyone.

You are jointly appointed in the Theatre and Film Department. Can you tell us a bit about your work in theatre and film and how it overlaps with gender studies?

I see theatre and film, along with most art and popular culture, as ways that we as humans explore what it means to be human. Storytelling is central to our species and it both explains us to ourselves as well as helps shape the ways we understand the world around us. It is also a powerful force in structuring our perceptions, in both psychological and sociological ways, of what is normal and what is expected of us in terms of gender. Often those expectations are so normalized that we don’t notice them. Examining theatre and film allows for a critique of just how our stories create those expectations. My work on a musical like Into the Woods argues that many of the reactionary, anti-feminist tropes of the 1980s are deeply embedded into that play, with its fears of sexual freedom (The Baker’s Wife) and of women with power (The Witch), and the reestablishment of a patriarchal family unit centered around the Baker, his child, and Cinderella, who moves in and states that she really does like to clean!

You have worked on gender representation in both film and live performances. How does your approach to the two forms differ?

Film is, in many ways, easier to write about because it is a relatively fixed thing. Even when there are directed cuts, or various other edits, you can watch and rewatch the film. Additionally, the nature of the camera creates a tighter focus on exactly what the director wants you to see, and that can also help focus your argument. Live performance is trickier because it is ephemeral. Live performances happen and then are gone. They are impacted to a large degree by the conditions of the time and the moment and the audience. It’s easy enough to give a literary analysis of a play, but to analyze a live performance often depends on being able to bring a kind of soft-focus to the process and then get your ideas and responses down as soon as possible. You can certainly see a play or dance or other live performance several times, but then you are really analyzing an amalgam of those various times because of the always changing, even if subtle, nature of those performances. All that said, however, both film and live performance are exciting to analyze precisely because of the ways in which they blend image and body and text to tell their story, and for both I attempt to understand how those stories reflect what it means to be human.

You have presented work on live zombie performance. Please tell us about this!

I became interested in understanding how the form of the zombie became, for quite a while in the 2000s and 2010s, a remarkably popular live event through zombie flash mobs, festivals, zombie 5k races, etc. There really was not another “monster” in popular culture that ever manifested in such a widespread manner in live performances. Sure there are some cosplay instances of vampires and other monsters, but there was something far more compelling about the zombie performances through their sheer numbers and popularity. I

think a lot of that has to do with the fact that most monsters are powerful in and of themselves: they are stronger and faster than humans, often with supernatural powers that are difficult for a “regular” human to play at. But zombies are broken bodies, and to assume the role you simply need some makeup and to allow gravity to pull at your body and to move with a kind of shuffling resistance. Zombies, slow zombies at least, are only powerful when they come together in numbers, and these flash mobs and zombie walks were ways in which people explored, perhaps unconsciously, how powerless individuals can find power through a kind of community.

You also create and release music. Tell us about your recent release of Science Fictions as These Liminal Days.

I began recording music as These Liminal Days back in 2019, with my first album, Shapes of Heaven

The Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies was established in 1981 to address the changing roles and expectations of women students, faculty, and staff.

Our Mission is to educate about issues of gender and sexuality, promote interdisciplinary research, and advocate for diversity, equity, and inclusion.

being released that summer. While all of my music work takes the form of ambient and electronic music, that first album contained a lot of nature sounds and pieces that were assembled over a period of several years. I followed that with a four-track EP of darker, more nebulous electronic soundscapes called “Empty Spaces 1.” When it came to my second full length album, Science Fictions, I wanted to create a series of soundscapes and experiences that would take the listener on a science fiction tour of imagined worlds, and so each track was designed with a specific world or interstellar space in mind. It’s the kind of music that I hope can provide an ambient background but also has details and subtleties that will be rewarding if you listen with headphones and the willingness to transport yourself to other worlds.

You can access Pria's music at https://theseliminaldays. bandcamp.com.

About the Isom Report:

Articles were written by Isom Center faculty and staff or from biographies supplied by guest speakers, artists, or their representatives. Images supplied by University Imaging Services, performers, Logan Kirkland, Mary Knight, Srijita Chattopadhyay, HG Biggs, Christina Steube, Isom Center faculty and staff, or licensed from Adobe Stock. Layout and graphic design work by Kevin Cozart.

Contact Us:

The Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies Suite D, 3rd Floor, Lamar Hall Post Office Box 1848

University, MS 38677 662.915.5916 isomctr@olemiss.edu sarahisomcenter.org facebook.com/sarahisomcenter twitter.com/sarahisomcenter

by ann monroe

In an era when some are questioning the value of safe spaces on college campuses, we must articulate their importance. Safe spaces—like the LGBTQ+ Lounge at the University of Mississippi—provide students, faculty, staff, and alumni with a sense of security and belonging. The Lounge serves as a hub for education and events, and the Lounge signals our shared respect for diversity and inclusion. The mere existence of safe spaces nudges us all toward better understanding and increased compassion.

I know this to be true. It happened to me. In October 2021 I sat in the LGBTQ+ Lounge at UM waiting for the start of the Missy launch party. Missy is the student-led literary magazine for LGBTQIA+ UM community members and their allies. There was a great crowd, and the atmosphere was happy but anticipatory. The event was late getting started. Tyler from Writing and Rhetoric rose to announce that we were waiting on “Greg.” The party could not start without him, as Missy was his brainchild. In the moment, this did not mean much to me, but I waited patiently.

course, but Greg’s offhanded joke had revealed a fundamental oversight.

On the way home, I began thinking about remedies and called my colleague in the School of Education, Dr. Joel Amidon, to discuss Greg’s insightful joke and my own realization. We had to do something. Later that year, we started the LGBTQIA+ Teacher Mentor Group in the School of Education. Interested pre-service teachers now meet monthly with queer teachers from across Mississippi to discuss the realities of being a gay teacher in environments that are not always welcoming. Greg is one of our mentors! This mentor group was in turn the inspiration for starting an annual GSA Summit to bring high school students involved in their GSA clubs to the UM campus. Gender & Sexuality Alliances (GSAs) are student-led organizations that bring together LGBTQ+ and allied youth to build community and address issues affecting them in their schools and communities.

“There he is!” declared someone from the back of the room. I looked over at the entrance to the Lounge to see Greg walking hurriedly toward the podium. I realized then that I knew Greg. Two years ago, he had been my student in the School of Education. Here he was now as an alumnus, running late for the Missy launch party because he was coming straight from the middle school where he taught English. He began, “Give me a minute everybody. I haven’t been able to be gay all day—I’ve been teaching middle school.”’

The line got a big laugh from the knowing crowd in the Lounge. I laughed too, but I was also jolted and concerned. In that moment, I knew I had—to some extent—failed Greg as a teacher. Yes, I had taught lessons about classroom management and educational theories, but had I ever spoken to Greg or to any of our future teachers about what it might be like to teach in Mississippi as a marginalized person? Here in the safe space of the LGBTQ+ Lounge, I was suddenly asking myself if my classroom was a safe space, too. I wanted it to be, of

This past May the Oxford High School and Lafayette County High School GSAs came to campus to learn about the resources available at the university. With the support of the Sarah Isom Center and the Department of Writing and Rhetoric, we explored the community-building initiatives and course offerings at UM that focus on LGBTQIA+ issues. We heard from speakers in the Lounge and enjoyed a session in the IDEAlab at the JD Williams Library, where we created pride buttons and keychains. During their visit, these high schoolers presented to our students and faculty in the School of Education, sharing their insights on what they need from teacher allies. Through this experience, the high school students took on the role of teachers, helping us grasp the essence of effective teaching and active allyship.

While these are modest programs, they would not have happened without Greg’s funny and profound candor. They would not have happened without the LGBTQ+ Lounge, a safe space of education and inspiration. Yes, we need more than just safe spaces. They are not enough to address the broader systemic issues of discrimination and inequality. They are, however, great places to start.

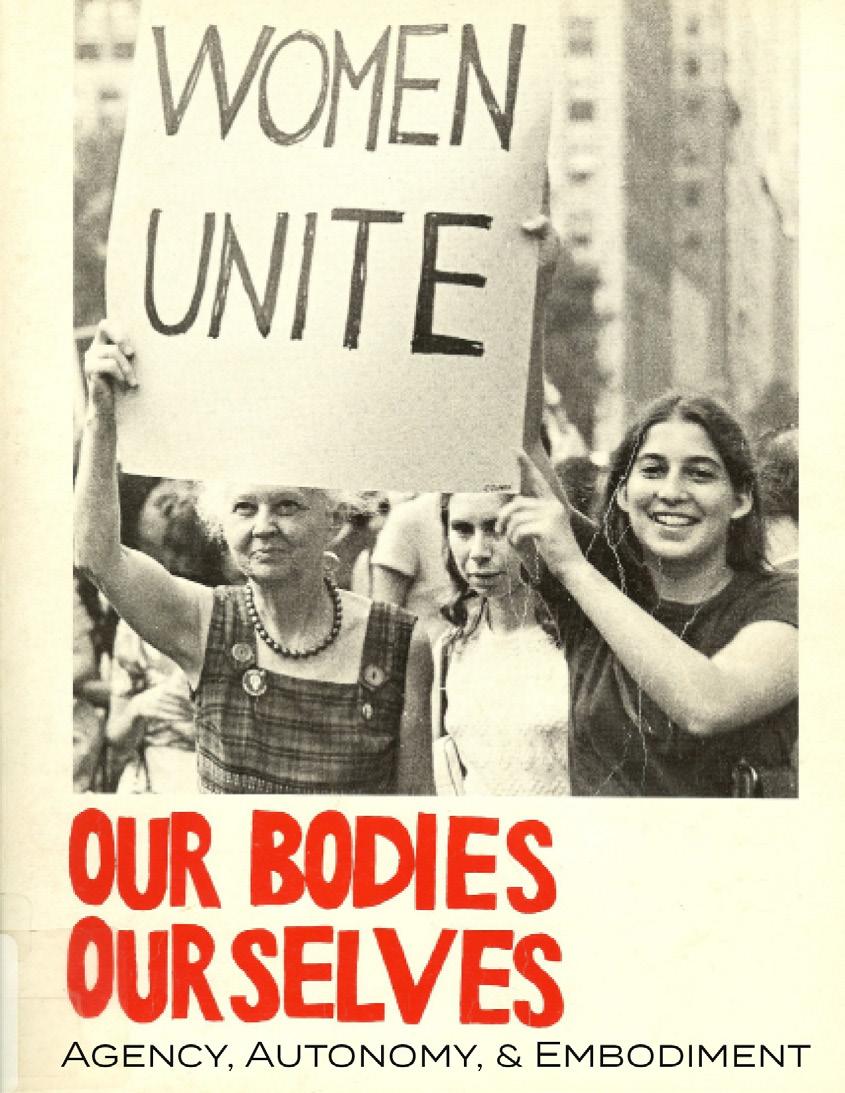

by Jaime Harker, tHeresa starkey, anD

This year’s Isom Center theme is the body politic, a rich concept that can help us think through multiple metaphors of the body. First, the body politic is often used to talk about the ways bodily autonomy is defined and politicized: in other words, how politics shape our embodied experiences, and vice versa. But the other dimension of the body politic addresses how we imagine people of a nation through body metaphors in the first place. Are we a unified body, with all systems working in harmony? Do we have fractures? Can we heal? The metaphors invoked by the body politic help us engage these multiple levels at once, showing how embodiment, personhood, and “the people” are intertwined concepts.

Writing in the summer of 2024, we are in a cultural moment when certain folks are NOT imagined as part of the body politic, a deliberate amputation. Depending on whom you talk to, this group includes: immigrants; liberals; Democrats; prisoners; felons; the homeless; residents of certain cities, counties or states; people of color; members of the LGBTQ+ community; feminists; and all women. We never imagined that we would hear political representatives calling for the repeal of the 14th, 19th, and 26th amendments, all of which deliberately and explicitly remove folks from the body politic (birthright citizenship, women’s suffrage, and universal suffrage at 18 years old, respectively). Nor did we imagine that representatives and senators might embrace the critique that the United States is not or should not aspire to the principles of a democracy.

One chilling aspect of this moment is the re-emergence of historic laws, showing how the long-past can force its way back into contemporary consciousness. In the spring of 2024, for example, the Arizona Supreme Court agreed to revert to a Civil War-era law relating to the prohibition on abortion. Just a few years ago, the idea that Roe v. Wade could be overturned and there would be a return to prohibition on abortion was more like an irrepressible specter, a haunting fear. Now, the specter has materialized. In the cover story on embodiment for The Isom Report two years ago, Jaime and Theresa reflected on this feeling of the past asserting itself in the present, examining ways that feminist activism of the 1960s and 1970s becomes urgent again as bodily rights are eroded. They wrote, “we are in another moment of restrictions of possibilities and choices and knowledge, and now abortion itself, made illegal” (10). It is easy to feel that we are trapped watching history’s reruns, as politicians attempt to repeal environmental regulations while enacting regulations on medical procedures, pregnancy, and fertility technologies. But our present isn’t simply a retread of our past.

In January 2024, Elizabeth taught Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower in Introduction to Gender Studies. The speculative fiction novel, the first in Butler’s two-book Earthseed series, is set in a dystopian American future. “God is change. Shape God,” advises Lauren Olamina, protagonist of Parable of the Sower. She refers to a non-theistic god, literally the force of change, so the imperative condenses into “shape change.” Lauren describes the world through her journal entries, first dated January 2024. (One can see why this text was destined to be used in

last spring’s class!) As an exercise, Elizabeth asked students to imagine a few decades into America’s future, as Butler had done when writing the book in the 1990s. Butler had even imagined a character (who appears in the second book of the series) who wants to “make America great again,” which poses a bitter irony for many contemporary readers. Prior to reading the novel, students overwhelmingly predicted worse civil discord and environmental degradation were to come in America’s future. In a sense, their pessimistic visions mirrored Butler’s foretelling. Yet Butler’s work is speculative fiction, and the students were asked to make straightforward predictions. In contrast with previous experience, it appeared, Elizabeth had students who did not imagine the world would inevitably improve as time passed. In her first years teaching feminist and queer history, Elizabeth felt herself resisting students’ tendency to believe that history is a progress narrative toward justice. She always thought that masked the work of changemakers to enshrine freedom and expand rights and protections. In January, Elizabeth recognized a shift from historical optimism to a new presentist or future-gazing pessimism. How do we teach not only to complicate a sense of history, but also to inspire a more hopeful vision of the future?

We want to suggest a different way to consider the moment in which we find ourselves, not only through political activism (something we discussed at length two years ago) but also through the ways cultural texts have represented the understanding that, as Jaime and Theresa wrote in The Isom Report, “in a fundamental way, your body is not understood to be yours. It is for others to regulate” (10). Puberty, reproduction, birthing, and even motherhood seem to

make one especially vulnerable to regulation, possibly because that is the moment where the individual plays a part in reproducing the body politic. Fears about one’s body being controlled by others, and the horrific consequences of such possession, have long animated dystopian and horror narratives.

Cultural production reveals the latent fears and anxieties of an age, and sometimes it also reveals the means to resistance and transformation. By considering what popular forms reveal about the structure of feeling in previous eras, and then our own current moment, we might imagine other possibilities than a horrific site of endless return.

Octavia Butler’s fin-de-siècle Parable series envisions a dangerous and devastated United States as it teeters on both environmental and civil collapse, much like the fatalistic environmental films of the 1970s. While activism was roiling the political sphere in the 1960s and 1970s, cinema was representing a lack of bodily autonomy in a number of popular culture forms. This is especially true of cinema, which was experiencing its own turmoil with the decline of the studio system and rise of independent film. For filmmakers working inside and outside the studio system, the inequities and questioning of the moment were central to their vision. Horror, as emotional depiction and as metaphor, expressed these concerns.

One has only to look at Roman Polanski’s 1968 film Rosemary’s Baby to see how a nightmare vision of motherhood was materializing on screen and in the American psyche. Rosemary, an expectant mother and housewife, has her fertility and conception supervised by others. She is not in control of her body. No one listens to

her when she tries to tell others that there is something wrong with her pregnancy. The realization that she is not in control comes too late for Rosemary–as does her recognition that her neighbors and husband are part of a Satanic cabal that wants her to birth the son of Satan. Rosemary’s personal dispossession results in a larger societal disruption.The film’s metaphors are heavy-handed and powerful: women’s disempowerment becomes Satan’s empowerment. No women’s liberation protest went nearly so far in its argument for the importance of bodily autonomy.

The dismissal of a mother's/woman’s/ girl’s anxiety is a thread that runs through a number of other 1970s horror films. In The Exorcist, no one believes Chris MacNeill when she tells doctors that there is something wrong with her twelve-year-old daughter, Regan. Regan is not in control of her own body due to a nefarious supernatural force. In the movie Carrie, a young teenage girl can’t control her telekinesis

powers. This is unsettling and frightening, but there is a more basic horror in the filmsuppressed knowledge. This plagues Carrie. She doesn’t understand how the body functions. Her first menses happens in the shower of the girl’s locker room at school. Carrie’s fear and lack of understanding are dismissed by the other girls around her who jeer and laugh at her traumatic experience. Bullying and shaming transform what could be a superpower into a malevolent force.

In the film The Stepford Wives, women’s bodies are literally not their own. Housewives in the picturesque community of Stepford are slowly replaced with automaton versions of themselves who love to shop for groceries, clean their homes with Olympic mania, and never age or gain weight. The newly arrived Joanna and her friend Bobby recognize that something is wrong in Stepford. For the Men’s Association of Stepford, their automaton creations are an idealized version of womanhood. The Association’s taste for a tainted gender ideology is the toxic problem for the town; the Men’s Association members long for a bygone twilight time when women were programmed to know their place. The film continues to be a cultural touchstone of sorts, articulating the horror of gender policing and the enforced prison of femininity–achievable only by the replacement of actual women with pliable bots.

Even if one didn’t know about the history of feminist activism during this period, cultural productions like horror movies revealed something deeply wrong with the larger culture in its rejection of bodily autonomy and agency and its schizophrenic enforcement of gender norms. The unrest of the period is reflected in the artistic metaphors of its popular culture, which created haunting images that served as allegories for a culture struggling to articulate and reimagine the moment in which they found themselves.

So what do our cultural productions tell us about our current popular moment? In retrospect, our insatiable appetite for

dystopian stories, most famously the Hunger Games trilogy, should have been a warning sign. 2017’s Get Out, a revival of the horror tradition, told another story of bodily dispossession, providing a haunting metaphor of the legacy of slavery in a WASP family’s theft of black bodies to satisfy their own delusions of grandeur and immortality. Don’t Worry, Darling, which premiered in fall 2022, appears to be set in a fantasy of mid-century America, where the men are engaged in important company work and women’s days are filled with leisure, a fantasy of traditional gender roles. Yet the facade cracks under the increasing curiosity of Alice (aptly named), who pursues information about her strange setting down a rabbit hole, so to speak, until its truth is revealed: the company town is a simulation. Her unsuccessful partner has taken possession of her body and entered them both into a virtual reality possibly as sinister as the world of The Stepford Wives. The 21st century twist is that the simulation also dispossesses the husband, who spends his days with other men toiling in the service of the company architect/patriarch (vaguely a men’s rights activist). Prescriptive gender roles hurt everyone, the movie suggests, including the men who think an anti-feminist message will return them to glory.

And yet, unlike the ambiguous, fatalistic or doomed endings of the 1970s horror movies, films from the past decade seem to offer counter narratives, feminist resolution, or ways out of the horror. Katniss topples the evil regime of The Hunger Games and returns home. Chris escapes his ghoulish captors at the end of Get Out. And, in a significant departure from the bleak ending of The Stepford Wives, Alice regains control of herself at the end of Don’t Worry, Darling, activating other women and triggering the defeat of the patriarch. Is this dystopian tale of dispossession an empowerment narrative for the 21st century? There is something that can be mobilized in a narrative of re-self-possession.

Defiant stories of resistance, it turns out, are as ubiquitous as dystopian hellscapes. Queer television is undergoing a renaissance right now. The Tales of the City reboot imagined a coalition of San Francisco citizens saving the home of pioneering trans character Mrs. Madigral from evil corporate developers. The Queer as Folk reboot, set in New Orleans, takes on the traumatic legacy of the Pulse shooting to imagine a truly inclusive queer and trans community, one that embraces polyamory, disability, and liberation from fixed gender and sexual roles. Cultural texts that kept queerness in the shadows, like A League of Our Own and Interview With a Vampire, now foreground queerness in ways previously unimaginable.

Feminist, queer, and trans young adult (YA) fiction may perform some of the most radical critiques and reimaginings of any cultural texts, which explains why censorship of such books in libraries and classrooms has become a cultural obsession in recent years. Kalynn Bayron’s Cinderella is Dead, for example,

reimagines the Cinderella legacy as a brutally misogynist patriarchy in which young women’s only future is chosen in a bizarre reenactment of the original “handsome prince” trope; its heroine destroys the evil at the heart of this hateful kingdom and liberates the women of the city.

Young people trapped in the horrific creations of adults is a common trope in these dystopian tales. Gearbreakers, by Zoe Hana Mikuta, imagines a world in which young people are incorporated in killing machines, hunting the few spaces of resistance left. Heather Walter’s Malice duology reimagines Sleeping Beauty, while making Aurora, the princess, fall in love with a sorceress, Alyce, in a world of such violence, retribution, and evil that none can escape its tainted legacy without a radical reform from monarchy to true representative democracy. Perhaps most devastating is the trans YA dystopian novel Hell Followed With Us, which imagines an America in which an extremist religious group has intentionally released a devastating virus, meant to cause Armageddon. It uses religious language to describe the monstrous creatures that emerge as a result of this act of terrorism, and features a trans character, Benji, who has been drafted by the group to be its avenging angel. Benji’s escape from the group and partnership with a small band of queer and trans youth results, ultimately, in the demise of the group that caused such chaos. And the book’s embrace of the monstrous makes it one of the most incisive critiques of contemporary society in queer and trans dystopian YA. It builds on Octavia Butler’s legacy, and like that legacy, it reaches beyond mainstream culture to genre fiction on the margins. The vision of the world that these books display is morbidly stark, yet they end with bands of young people resist-

ing, defeating, and vanquishing the forces of destruction. Jaime has been reading these books for many years (as part of a larger scholarly project) and she can say, definitively, that if you want to understand Gen Z and their vision for the future, read these YA novels.

What these feminist, queer, and trans YA novelists understand is that the stories we tell ourselves provide the limit of what’s possible. In the words of feminist critic Rachel Blau DuPlessis, we need books that write beyond the ending and beyond the limitations of our current sense of the possible to stories that envision different endings and fantastic possibilities.

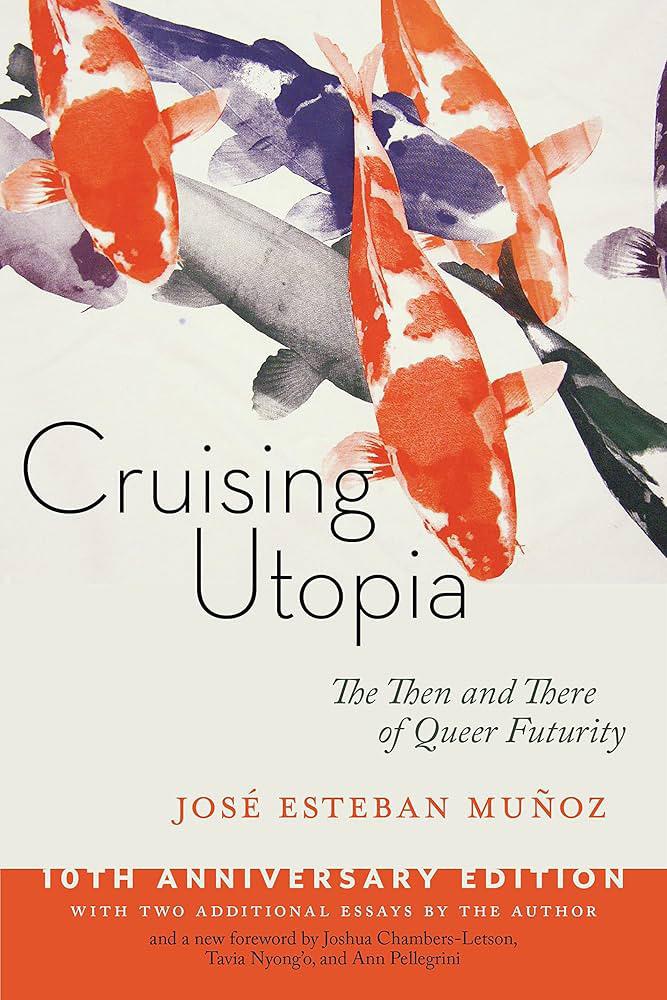

What these recent cultural texts suggest is the power of utopian dreaming. When we have freedom to investigate our past, we gain models for resistance. But we are not limited to the actions of the past. When we imagine our present in new forms, we move toward dreaming of what might be, what could be, what should be: what people really need to thrive. What kind of world do we want? How do we get there? Imagining the world we want, instead of just surviving the one we have, is essential to the work ahead of us.

in every conceivable genre, you would not have thought this would become anything but a cautionary tale for participants, a source of embarrassment. But when you look at the explosion of queer young adult fiction, the incredible worlds young people can inhabit imaginatively for thousands of pages, and the influence these stories have, you can see that an often maligned moment of utopian dreaming has had a huge effect. And it hasn’t just stayed in fan forums; the multiple genders and sexualities envisioned in forums on Tumblr have become mainstream in ways no one would have believed possible. Utopian dreaming is essential to both surviving and thriving.

Jose Muñoz may have said it best in his book Cruising Utopia: “Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality. Put another way, we are not yet queer, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality. We have never been queer, yet queerness exists for us as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future. The future is queerness’s domain” (1).

It can start small. Jaime has spent the past few years working on a book on 21st century Sapphic writing; fanfiction communities have become central to this story. That beginning was so small as to seem almost trivial: what if my two favorite female characters were really a couple? What if I didn’t have to wait for the mainstream media to catch on and wrote the story myself? Looking at the awkwardly designed fan sites of the 1990s, with slash fiction

The future is our domain, too. In this moment of backlash and despair, imagine the world you would like to live in, and then dream about how to remake the world the way you think it should be. How do we resist despair? Partly through reading cultural texts and the current movements not just for an expression of our anxieties but as a model for utopian dreaming. Octavia Butler’s powerful parables are important models here. She imagined not just the divisive rhetoric that dominates our political moment, but also the means for transformation in a broken world, through the power of communities working hard together to shape change. The present isn’t simply a retread, and no future is inevitable. Through utopian dreaming, we can create more feminist and queer futures.

by Jaime Harker

We are in another moment where we, like our feminist and queer forebears, need to be fearless, and full of fortitude. In a moment when so many of the gains of women’s liberation are being undone, how do we not lose heart?

Here are a few things I have learned from activists who came before us.

So much of the acculturation of femininity has to do with staying in bounds—within “appropriate” markers of femininity, or the bounds of “good taste,” or the performance of “ladyhood.” We sense from an early age how tenuous the supposed benefits of femininity are and how quickly they can be rescinded if we don’t color inside the lines.

And yet, we spend so much time, still, proving how reasonable we are, how collaborative, how not “hysterical” and “angry” and “man-hating” and “lesbian” and whatever other epithet is used to keep women in line. The backlash against women’s liberation wrote the playbook for this, and women, even feminist women, who wanted to be taken seriously by the establishment knew exactly what to avoid.

One of the things I love about early women’s liberation and gay liberation is how little they cared about what the media said about them. They actually enjoyed freaking out the "straights." They did not care if people thought they were angry, or hysterical, or unattractive, or too much. They knew that the liberation of their own minds mattered more than any disapproving chorus of the status quo. They kept daring each other to go further, to break another taboo, to make fun of something sacred, to step out of bounds and see what happened.

fundraiser (was this to highlight homophobia or just because she enjoyed freaking people out?); the radicalesbians’ hilarious “Lavender Menace” tee reveal after Betty Friedan earnestly blamed the “Lavender Menace” for undermining the women’s movement. They trolled conservatives; they laughed at media pearl-clutching; they ridiculed prescriptive feminine mores. They refused to submit to the male gaze.

You could say that they made it easy for mainstream media to caricature them (many subsequent feminists did say that). An impromptu burning of the items of women’s oppression led to a nickname of “bra burning” that is as ubiquitous as it is inaccurate. But they would have said that nothing will prevent the mainstream media from caricature; you have to stop caring what they think. You have to stop caring about being called names. Until every woman is free to be a lesbian, no woman is free. Until every woman is free to be unladylike, no woman is free.

We would call this, today, a rejection of the politics of respectability because to conform to the standards of "proper behavior" is to oppress oneself; the state, in a sense, outsources its own enforcement by encouraging individual subjects to regulate themselves and those around them. Freedom begins in one’s own mind, and the liberation of consciousness is the first step, as those early women’s liberationists knew. The moment you stop being traumatized or outraged by the status quo, and laugh at it, is the moment you refuse to do the dirty work of the patriarchy. Willful and joyful transgression is the moment the foundations begin to shake.

Early “actions” were avant garde performances in public: Karla Jay heckling Wall Street traders on the way to work, to highlight the harassment women regularly were subjected to; Jill Johnston taking off her shirt and swimming in Marlo Thomas’s pool at an ERA

What we need, Brittany Cooper has argued, is disrespectability politics. If they find us too angry, too unfeminine, too crass, too unladylike, that means we are doing the right things.

So many of the visible "wins" of the women’s movement grew out of the legal framework of the rights of the individual. But the real work of women’s liberation, including legal work, was done within the community. A lone individual facing the “machine” was not going to make it long; our unequal systems were made to crush lone individuals, our cultural myths notwithstanding.

All social movements have one thing in common: community. You need a critical mass of people to cause a shift in perception and attitude, but even more importantly, you need community to stay focused, joyful, and engaged. Taking on huge cultural sacred cows brings negative consequences, exacerbated by social media—doxxing, harassment, and campaigns to employers, publishers, and supporters are not uncommon, sadly.

Early women’s liberationists would attend a protest and then hit the dance at the fire hall afterward; protesting, cruising, writing, performing, all were part of the continuum of community. Community can be fractious, divisive, judgmental, sure, but it is still essential.

Marge Piercy’s poem “The Low Road” says it best. When you are one, “they” can do anything they want to you. But as you join forces, more is possible; she maps out what is possible when your community grows: “Two people can keep each other/sane, can give support, conviction,/ love, massage, hope, sex./ Three people are a delegation,/ a committee, a wedge. With four/ you can play bridge and start/ an organization. With six/ you can rent a whole house,/ eat pie for dinner with no/ seconds, and hold a fund raising party./ A dozen make a demonstration./ A hundred fill a hall./ A thousand have solidarity and your own newsletter;/ ten thousand, power and your own paper;/ a hundred thousand, your own media;/ ten million, your own country.”

It all leads up to a rousing conclusion: why community matters.

It goes on one at a time, it starts when you care to act, it starts when you do it again after they said no, it starts when you say We and know who you mean, and each day you mean one more.

Go find your people. If the community you need doesn’t exist, create it.

“Reality,”

It’s not an accident that so much of the pushback of the past several years has to do with visibility and memory. What past are we allowed to remember? Whose existence are we allowed to recognize? When you excise the history that doesn’t fit the story you want to tell about yourself, you erase other folks’ experience. When you refuse to allow libraries to carry books that represent lives you deem obscene or illegal or irrelevant, you erase other folks’ existence.

This is why public libraries and school curricula have been in the bullseye: they are central contact zones for what used to be celebrated as the free market of ideas. When you prevent teachers from acknowledging the history of segregation or race riots or queer activism, you make certain experiences unspeakable. When you prevent libraries from having books about queer experience or critical race theory from ever being checked out, you prevent citizens from learning about the full range of ideas and activism and resistance that is our birthright.

Fighting those battles is important, because these are public spaces meant to support the informed citizenship essential to a democracy. But so, too, is creating alternative paths toward knowledge and insight and exploration. The Women in Print movement made creating its own publishing ecosystem central to feminist activism; with independent presses and feminist bookstores, readers could access ideas without the filter of capitalist heteropatriarchy. The resurgence of Black bookstores, Indigenous bookstores, feminist bookstores, and queer bookstores in the last ten years suggests that this idea is enjoying a revival.

But the potential for alternative representation and history is even greater: with self-publishing, you bypass the need for any sort of gatekeeper; ebooks can be delivered instantly to your phone. And social media provides multiple opportunities for alternative histories and alternative communities, from Black history to queer history to trans history. One recent Ph.D. in Art History turned her Instagram account, the Great Women Artists, into a podcast, book, and curation career that is supporting her and educating tens of thousands about the long history of women artists.

What we know about our past, our genealogy, and what we can see about our own present informs our sense of “reality” and our understanding of what is possible. Embracing the many tools we have to provide counterpoints and hidden histories is more essential than ever in this moment of censorship and wilful un-remembering.

Briona Simone Jones

october 10, 2024 • 4pm

The Queer Studies Lecture was established in 2014, connected with the development of the queer studies emphasis in the Gender Studies minor. This fall’s Queer Studies lecture will be given by Briona Simone Jones.

Briona Simone Jones is Assistant Professor of English and Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Connecticut. She is the editor of the multi-award-winning book Mouths of Rain: An Anthology of Black Lesbian Thought, the most comprehensive anthology centering Black Lesbian Thought to date. Jones was recently a Scholar-in-Residence at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture working on her second book Black Lesbian Aesthetics and curating the exhibition The Pleasure of Rebellion, which attended to the personal and political contours of Cheryl Clarke and Alexis De Veaux's work.

ACE Studies Lecture:

Ela Przybyło

october 30, 2024 • 4pm

The ACE Studies Lecture was established in the spring of 2022, to coincide with the Glitterary Festival, a queer literary conference. We subsequently moved this lecture to the fall, to coincide with asexuality week at the end of October. This year’s ACE Studies Lecture will be delivered by Ela Przybyło.

Ela Przybyło (she/they) is Associate Professor and Graduate Director in English and Core Faculty in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Illinois State University. She is the author of Asexual Erotics: Intimate Readings of Compulsory Sexuality (Ohio State University Press, 2019) and Ungendering Menstruation (University of Minnesota Press, forthcoming), as well as co-editor of On the Politics of Ugliness (2018), and, with Yo-Ling Chen, the in-progress collection, Global Asexualities and Aromanticisms. They enjoy cold water dips, vegan dining, and resting in bed.

Howorth Lecture: Jack Jen Gieseking

marcH 6, 2025 • 4pm

The oldest of our annual lectures, the Lucy Somerville Howorth Lecture was established in 1991 to honor the life and career of Lucy Somerville Howorth, who was one of the first women to receive a juris doctor from UM. The endowed series brings distinguished speakers to campus in the area of women’s and gender studies. During her life, Howorth served the State of Mississippi in the executive and legislative branches, including being the first woman to represent Hinds County in the state legislature, and in the Federal Government. She was also heavily involved in the American Association of University Women, which endowed the lecture series in her honor. This year's lecturer is Jack Jen Gieseking. Jack Jen Gieseking is an urban and digital cultural geographer, feminist and queer theorist,

American studies scholar, and environmental psychologist, engaged in research on co-productions of space and gender and sexual identity in digital and material environments. His first book, A Queer New York: Geographies of Lesbians, Dykes, and Queers, 19832008, came out in 2020 from New York University Press. His second book is based on the data gathered from the multigenerational interviews and mental mapping exercises along with new archival research to more closely examine the lesbian-queer relationship to land. He explores the practices that work to define lesbian/queer/trans life in and beyond dyke bars and queer parties, namely through activist zaps and organizing, gender expression and styles, kinship and friendship, and sex and desire. Geiseking identifies as a woman, and a lesbian trans butch queer at that, and uses they and he pronouns.

Trans Studies Lecture: Hil Malatino

marcH 27, 2025 • 4pm

The Trans Studies lecture was established in 2021, growing out of a Trans Summit hosted by the Division of Diversity and the Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies in 2019. This year’s lecturer is Hil Malatino. The Trans Studies Lecture will also serve as the keynote for the Isom Student Gender Conference.

Hil Malatino is Joyce L. and Douglas S. Sherwin Early Career Professor in the Rock Ethics Institute and Associate Professor of Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Philosophy at Penn State University. He is the author of Climbing (forthcoming, Duke), Side Affects: On Being Trans and Feeling Bad (Minnesota 2022), Trans Care (Minnesota 2020), and Queer Embodiment: Monstrosity, Medical Violence, and Intersex Experience (Nebraska 2019) and co-editor of the t4t issue of TSQ alongside Cam Awkward-Rich and the "Care Ethics Otherwise" issue of Essays in Philosophy alongside Sarah Clark-Miller and Amy McKiernan. His essays have appeared in Hypatia, TSQ, Signs, and many other journals and edited volumes. He is a Lambda Literary Award finalist and recipient of the Leslie Feinberg Award in Trans Literature.

The Isom Center's Lecture Series are sponsored by the College of Liberal Arts, the Lucy Somerville Howorth Lecture Fund, the Isom Arts, Culture, and Community Development Fund and others.

by tHeresa starkey & kevin cozart

The Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies welcomes historian and photographer Churck Steffen as this year’s featured artist for our annual art show at the Powerhouse Community Arts Center. The exhibit entitled “Surplussed Atlanta: The Built Environment of Homelessness” will explore homelessness in Atlanta and the politicization of poverty and will be on display September 6-26. Chuck will be presenting a SouthTalk for the Center for the Study of Southern Culture on Wednesday, September 24, and will be on Thacker Mountain Radio on Thursday, September 25. A reception will precede TMR at the Powerhouse at 5:30.

In October, Julie Williams will join us along with our partners Living Music Resource and TMR for an LMR Live and a songwriting masterclass on the 9th, followed by an appearance on the Thacker Mountain Radio Show on the 10th.

Sarahfest 2024 will close out with our Sarahfest Arist-in-Residence featuring Dr. Caroline Young from Nov. 2 - 6. Her residency, entitled “Opening Up: The Art of the Social Engagement," will explore the intersections among art, interaction, and the idea of pure expression. For the first time, faculty and staff are able to join students as part of the cohort. There will be several options for the public to interact with her, including an LMR Live, a pedagogy craft talk, and more.

Chuck Steffen was born in Los Angeles and grew up in southern California. After graduating from the University of California at San Diego, he relocated to Chicago to pursue his graduate education at Northwestern University. He spent forty years teaching US history at Murray State University and Georgia State University before his retirement in 2018. He has published on a variety of topics, including the politics of homelessness in Atlanta. This research project changed his life in two ways. First, it introduced him to photography as a tool for documenting the lives of unhoused populations in the city. Second, it led to his decision to join the board of directors of the Metro Atlanta Task Force for the Homeless, a nonprofit organization that operated the largest homeless shelter in Atlanta. These days, Steffen continues to take pictures for his website, “Framing Capitalism in Place,” which documents the impact of capitalism on the built environment. This work can be seen at www.chucksteffenphotography.com.

Singer-songwriter Julie Williams is turning heads in Nashville’s country music scene with songs that tell the stories she wished to hear as a mixed race child. A regular host of The Song Suffragettes, Julie was named in Rissi Palmer’s Color Me Country Class of 2021, featured on She Wolf Radio’s Ones 2 Watch list and her single "Southern Curls" was covered by Billboard, CMT, PBS NewsHour, and numerous music publications. Having opened for acts such

as RaeLynn and Mt. Joy, Julie tours with the Black Opry Revue, a showcase of Black artists in country, blues, folk, and Americana music, and performed with the group at CMA Fest 2022 in Nashville. After a summer solo tour on the East Coast and across the pond in London, Julie is traveling the country again this fall with performances across the Midwest, West Coast, and Northeast.

Dr. Caroline Young earned her bachelor’s degree in art history from Boston University and spent the

next sixteen years working in television, specifically TV broadcast promotion. Not truly feeling like she had found her niche, she went back to school to earn her MFA in poetry from Queens University. Dr. Young was accepted into the graduate program in the Department of English at UGA, earning her PhD in 20th- and 21st-century American literature with an emphasis in experimental female poetry. Dr. Young then spent three years as a Brittain Postdoctoral Fellow in Georgia Tech’s Literature and Communication department, and after that, two years working as a lecturer at Clemson University where she truly fell in love with the philosophies and practices of teaching.

When she’s not lecturing at UGA, Dr. Young teaches at Whitworth Women’s Facility in Hartwell, Georgia, where she works with female inmates to find their voices and identities through poetry and literary expression. Young is a 2024 Service-Learning Teaching Excellence Award recipient from University of Georgia. In 2023 she received the prestigious Silver Medal Award from the Southeastern Museums Conference for her curated exhibit “Art is a Form of Freedom.” The exhibit was a collaborative effort between Dr. Young, the women of Wentworth Prison, the Department of Corrections, Alumni of the nonprofit Common Good Atlanta, and the Georgia Museum of Art.

Visit sarahfest.rocks for more information and a full schedule of events.

The Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies at the University of Mississippi is pleased to announce its 25th Annual Isom Student Gender Conference (ISGC). The ISGC is scheduled for Wednesday, March 26, through Friday, March 28, on the campus of the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Mississippi.

The “body politic” has long been a way to visualize society and its governing structures as a single imaginary body made up of real individual bodies. While this single imaginary body has changed shape throughout its historical development, the body politic remains an enduring metaphor for the social and political organization of groups of people and for our understanding of ourselves as a “we.” While this collective self-consciousness has its roots in the “royal we,” in which a singular governing figure speaks for the entire body, more contemporary liberation movements have imagined themselves as the voice of the “we” united by the same political and social motivations. Such movements relocate the voice of the “we” to the real individual bodies that have been subject to the disciplinary power of the body politic, thus transforming this singular concept into body politics.

In her powerful text, The Body Is Not An Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love, activist and educator, Sonya Renee Taylor states that “a radical self-love world is a world free from the systems of oppression that make it difficult and sometimes deadly to live in our bodies. "[It is] a world that works for every body" (5). At the center of body politics are the interpersonal, societal, and structural struggles to maintain control over one’s own body, and thus one’s own experiences and futures. It spans from our individual choices about our bodies, to the structural factors that enrich, liberate, restrict, and threaten our bodies and lives. Our bodies are read by others to represent who we are—our identities, our heritage, our race, ethnicity, gender, and status are often assumed by others based on our bodily assemblage. And while these assumptions can be and are often incorrect, our superficial physical characteristics

have historically become the basis for separating humans from one another—judging others on social constructions of difference. The ways in which we become categorized are often imposed upon us by systems of power. Feminist endeavors then move to challenge and undermine notions of the "standard," or "normal" body as always already white, male, able-bodied, heterosexual, and gender-conforming.

“The Body” is indeed a site of political debate and liberation. In a 2017 Unity Rally in New York City, political activist and author Angela Davis stated, “I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.” Body politics invites us to ask how we might imagine a world where we are not made to fight for bodily autonomy, or fight ourselves for bodily acceptance, and the various forms of activist work that continue to challenge our current political structures that continue to make us so vulnerable. What are we willing to fight for to change and how can we get there? How does pop culture contribute to these debates/ fights/etc? In response to current Supreme Court decisions and subsequent political objectives, this conference is interested in generating discourse about the ways in which our bodies (and thus lives) are perceived, policed, debated, and used as sites of resistance. We encourage participants to discuss issues about gender-affirming health care, reproductive freedoms and restrictions, disability justice, police brutality, abortion and contraceptive access, fatphobia, colorism, body positivity, anti-Black racism, rape culture, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, environmental issues, sexual politics, etc. We are also interested in the analysis of how pop culture has addressed (or not) the aforementioned topics.

Dr. Hil Malatino (Penn State) will deliver the conference's keynote, which will also serve as the Trans Studies Lecture.

Submission deadline is Dec 19, 2024. A small number of domestic travel grants will be made available to non-UM students. To learn more visit https://isomstudentgenderconference.org/.

The 2024 Isom Student Gender Conference was held March 20-21, 2024, in Johnson Commons East. The theme was "Intersections of Inequality." Dr. Alex Ketchum, assistant professor at McGill University, delivered the keynote entitled "Finding the Ingredients for Revolution and How We Share the Histories of Lesbian, Queer, and Feminist Spaces." The keynote also served as the Lucy Somerville Howorth Lecture for 2024.

April 27 - May 3, 2025