The Isom RepoRT

2023-2024

2023-2024

The first time I ever saw Minnie Bruce Pratt in person, she was checking out at a gay bookstore in Boston with Leslie Feinberg on the day of the Pride parade. I had heard Feinberg read at Temple University, where I was selling copies of Stone Butch Blues for a friend who worked at Giovanni’s Room, so I recognized hir (Feinberg preferred ze/hir). I hadn’t seen Pratt, though—short curly hair, dazzling smile, in a dress (was it really floral? Or is that just my memory?). I was hanging out with a lovely gay man whose partner hadn’t wanted to go to the bookstore, and we recognized them just as they were leaving. We ran after to ask them to sign something, and caught them at the crosswalk. When none of us had a pen, we laughed and walked away empty-handed.

I didn’t know a lot about Minnie Bruce Pratt then. It wasn’t until I moved to Mississippi and was introduced to the lesbian feminist collective, Feminary, based in North Carolina, that I learned about her own writing. The first book I read by Pratt was

a collection of her essays and speeches, Rebellion, and it absolutely rocked my world. I remember especially “Identity: Skin Blood Heart,” Pratt’s essay about the assumptions and frames we carry with us and the multiple ways we need to grow, to become uncomfortable, and to change as we deconstruct our racism, sexism, homophobia, classism. Her descriptions of her small Southern town, the specificity of detail about its layout and the hierarchies that layout entailed, spoke to me as I tried to learn a new landscape in Oxford, Mississippi, and understand the embedded histories and ideologies that landscape hid. Pratt rejected the birds’ eye view—the grid from above, viewed as if by God—for a different, more layered understanding. Pratt explained that “as I change, I learn a way of looking at the world that is more accurate, complex, multilayered, multidimensioned, more truthful. To see the world of overlapping circles, like movement on the mill pond after a fish has jumped, instead of the courthouse square with me at the middle, even if I am on the ground.” Overlapping circles, multilayered, multidimensional—Pratt made me rethink how I saw, how I understood; she made me understand that we are never just seeing one thing. Past, present, and imagined futures, all are contained in the seemingly transparent things we observe. Pratt was exploring the intersectionality of identity, long before this became central to feminist and queer practice. With a poet’s eye for detail, she makes us notice the little details that make all the difference in our understanding.

I used that selection from “Identity” in my lesbian reading of Absalom! Absalom! at the Faulkner conference that summer, and it, more than the feminist geography I read or the outrage I provoked when I quoted Florence King to start my presentation, was the guiding star of that essay: reading landscape differently. Reading narrative differently. Noticing the things the author sees only in the corner of his eye, and making it central. Unraveling the layers until the queer and feminist identities became visible.

“I was determined that my life would not be tragic,” said Minnie Bruce Pratt, poet, activist, and queer icon. “But to do that, I had to fight.” To understand Pratt’s fight is to understand her life, and her significance.

Not long after I started working at the University of Mississippi, I went to a panel at the American Studies Association to hear John Howard speak. On that panel was Minnie Bruce Pratt, who talked about her own aunt, whom she never realized was a butch until Leslie Feinberg saw her. I think I was too shy to really talk to her that day—introducing myself to John Howard was what I managed.

When I began working on the book that would become The Lesbian South, Pratt became one of my touchstones. Duke’s Rubenstein Library had her papers, and her letters appeared in a number of other collections as well, as did those of her friends, rivals, former lovers, subscribers, and fans. Her poetry collection, Crime Against Nature, marked the moment in 1989 when the Women in Print movement gained mainstream recognition, winning the Lamont Poetry Prize.

Crime Against Nature taught me, in a sense, the origin story of Minnie Bruce Pratt; it detailed the loss of custody of her sons when she came out as a lesbian. Pratt had grown up in a middle-class family, joined a sorority, and married a man whose literary aspirations had mirrored her own. She had been protected from the harshest penalties her culture could mete out because she was considered conventionally pretty, because she conformed to the required initiations and rituals of her culture, because she married and bore two children—two boys. If she were a poet, that could be explained away, patronizingly, as a feminine hobby.

But when she stopped conforming—when she fell in love with a woman and refused to hide or deny that fact—she discovered the cost of stepping out of bounds. Her husband threatened to have her prosecuted for a “crime against nature,” a felony with guaranteed jail time; using this threat, he claimed sole custody of their two sons. Crime Against Nature, published long after that initial loss, explored the consequences of that break, in poetry so gorgeous and heartbreaking that even the mainstream judg-

es’ panel of the Lamont Poetry Prize could not resist it.

Minnie Bruce Pratt might have crumbled under the weight of this grief. The trauma of that loss took years to process; she was, in some sense, still healing from that wound, long after her boys were grown and her grandchildren knew her as a doting grandparent. She healed through activism, refusing to accept the systems that devastated her and through her writing, which deconstructed those oppressive systems and imagined something new.

She co-founded the Feminary collective in 1979 and wrote, in prose and poetry, incisive investigations of the power systems that informed the South. She kept learning about the intersections of inequality and kept publicly agitating—against systemic racism, against bigotry, against Antisemitism. She refused essentialism and transphobia, helping to create Club T as an alternative to the transexclusionary Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. She wrote for the Daily Worker through 2023, critiquing the “money machine” of American capitalism explicitly. In ways large and small, in public protests and keynotes and classrooms, she kept teaching and organizing.

Pratt, more than most, understood the cost of gender—the cost of refusing to conform to one ‘acceptable’ version of femininity. She knew, when she came out in the 1970s, that she would never be hired in a tenure track job, and she was right. She spent her career adjuncting and speaking, and not until the end of her teaching career did she even have a full-time position with benefits. I recognize the irony that I was promoted writing about her work, but she was never given the most basic of job security for actually writing the work.

The thing about Minnie Bruce Pratt is that she understood this too, without bitterness. “Why,” she asked, “would the capitalist system reward me for critiquing that same system?” She wasn’t surprised, because she knew, in a way that most academics do not, that meritocracy does not rule, in academia or anywhere else. She knew that wages and benefits have nothing to do with worth and everything to do with the desires of the powers that be.

She understood the cost of gender, but she did not accept that such a system had the right to bestow value or worth. And she also understood that conformity came with its own deadly cost—and of the two, the cost of freedom was preferable to the cost of subjector.

That hers was the better way was clear in my every interaction with her. I didn’t really talk with Minnie

Bruce Pratt until after The Lesbian South came out, when we invited her to deliver a keynote at Southeastern Women's Studies Association (SEWSA), an organization she helped to found.

I soon learned that Minnie

Bruce Pratt didn’t approach any of these accolades the way other scholars did. She made an appointment to call me on the phone, talked to me about our goals and the larger focus of the conference (“Envisioning a Feminist and Queer South”), and then delivered the best keynote we have ever had, focused on the specifics of our cultural location. She went to every session and asked questions and met with everyone; she brought first editions of her books and sold them, signed, at rock bottom prices; she went out of her way to make time to do an interview with a Southern Studies master’s student who worshiped her, and who told me, after she came up to him to make an appointment for his interview, “this is the best day of my life.” She met with students from Students Against Social Injustice (SASI) and wrote about them for the Daily Worker

She went to dinner with a group of Sapphic women and told stories that had us laughing uproariously. The next time we invited her to come speak at UM, I arranged for several students to come with us, including one who had written her Ph.D. written comp on Crime Against Nature. Minnie Bruce Pratt also came and talked with me and my wife, a chef, for a long time; when she spoke with you, you were

the most important person in the world to her.

Knowing Minnie Bruce Pratt has been one of the great privileges of my life. I, too, have learned something about the cost of gender, the cost of not fitting in and refusing to fake it. I lost the religious community that raised me when I came out, and that trauma—discovering that a community you loved would no longer love you when they knew who you really were—is something I always carry with me. But for all the things I lost, the things I have gained have been far greater. I have met people of extraordinary kindness and fierce bravery and active compassion, who fight for a better life for everyone, in spite of a system that seems designed to spit us out and break our hearts. People like Minnie Bruce Pratt, and Leslie Feinberg. I still remember that first talk I heard from Feinberg, back when I was a new graduate student. My friend at Harvard Divinity School had told me about Stone Butch Blues, and when I listened to Feinberg, so open and proud and brave in hir fitted suit, facing ignorant and often hostile crowds who didn’t want to know what ‘transgender’ meant, I knew my own limited upbringing was being cracked wide open. “We all go in together,” Feinberg said, “or we don’t go in at all.” When Feinberg was talking, in the early 1990s, even those in the queer community refused to embrace the trans folks who had always been central to gay liberation. Minnie Bruce Pratt embraced that cause, and so many others, disavowing the privilege a pretty femme might have claimed to proclaim the solidarity of all of us.

Minnie Bruce Pratt was, for me, a kind of queer saint, a model of everything I want to be as a teacher and a scholar: warm, engaged, insightful, generous, brilliant, noble. In the moment we find ourselves, when so many gains that her generation of activists won are being watered down or overturned

or ignored, we need her inspiration more than ever. Pratt and her generation refused to allow conventional wisdom to make them doubt themselves and committed to the hard work of deconstructing their bigotry and privilege and building coalitions that make the world better for all of us. Pratt refused to be divided from her allies and insisted that we all can grow and change and resist, in the face of the most hostile opposition. I will miss her more than I ever can express, and I will try to live up to the example she set for all of us.

About the Isom Center:

The Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies was established in 1981 to address the changing roles and expectations of women students, faculty, and staff.

Our Mission is to educate about issues of gender and sexuality, promote interdisciplinary research, and advocate for diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The cost of gender is high, but the cost of conformity is higher still. Together, we can lift each other up and make a better, freer world for those who come after. Writers and activists like Minnie Bruce Pratt taught me that. May her memory forever be a blessing.

About the Isom Report:

Articles were written by Isom Center staff or from biographies supplied by guest speakers, artists, or their representatives. Images supplied by Univ. Imaging Services, performers, Logan Kirkland, Mary Knight, Srijita Chattopadhyay, Isom Center faculty and staff, or licensed from Adobe Stock. Layout and

Contact Us:

The Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies

Suite D, 3rd Floor, Lamar Hall Post Office Box 1848

University, MS 38677

662.915.5916

isomctr@olemiss.edu

sarahisomcenter.org

facebook.com/sarahisomcenter

twitter.com/sarahisomcenter

graphic design work by Kevin Cozart.Hey y’all! We are excited to introduce everyone to Dr. Jennifer Venable, Instructional Assistant Professor of Gender Studies here at the Sarah Isom Center. Dr. Venable joined the Isom Center at the beginning of the second fall term in 2022. I had a chance to ask Dr. Venable some questions to get to know her better, and I want to share her bright personality with everyone.

What is an influential tv series or movie for you?

Growing up, I was obsessed with the Buffy the Vampire Slayer TV series. I didn’t really think about why the show and Buffy were so important to me when I was little, but as an adult, I know it was because it was so rare to see a female character portrayed as the hero or as strong in general. So maybe loving Buffy has something to do with my interest in feminism and the empowerment of women and other marginalized groups.

I know you have a dog – tell us about her!

I am a dog mama, and my pup is everything to me. Her name is Myla Meaux; she’s a small mixed breed pup but has such long legs! She has a really funny sense of humor and will do weird little gestures or movements when she’s feeling goofy. We take her on a couple walks every day, and she gets tons of belly rubs and cuddles. She is my best friend, and I like to think that she is very passionate about social justice issues and that she is a little feminist pup!

Who is your favorite feminist theorist?

Audre Lorde. When I first read her work, not only did she make such complex issues and ideas so accessible to me, but her work also gave me the language for a lot of issues I didn’t

really know how to talk about. I always assign her work in my classes, especially readings like “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” and “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism” because my students always connect to these pieces in different ways.

Tell us about living in Louisiana!

I am from a very big family, and I missed them so much when I moved away, so that is my favorite thing about being back in Louisiana. Louisiana has the best food ever; I don’t feel like people can say otherwise! Haha! And my partner and I love cooking vegan Cajun versions of traditional dishes we grew up eating, and then sharing that with others. I love being around Louisiana culture, which of course includes the food, but also the music, and festivals, language, and ways of being that are different down here. There is a particular openness that I love and gravitate towards in a lot of people who are from Louisiana. It is this kind of way that many folks live authentically---they are vulnerable, and love to have fun and share their time with others---that I really cherish living in my home state.

Thank you, Dr. Venable. I’m so glad we are colleagues and friends!

Above: Last year's Sarahfest included an art show at the Powerhouse, a fusion of music and art event called hours, and a special Sarahfest edition of Thacker Mountain Radio.

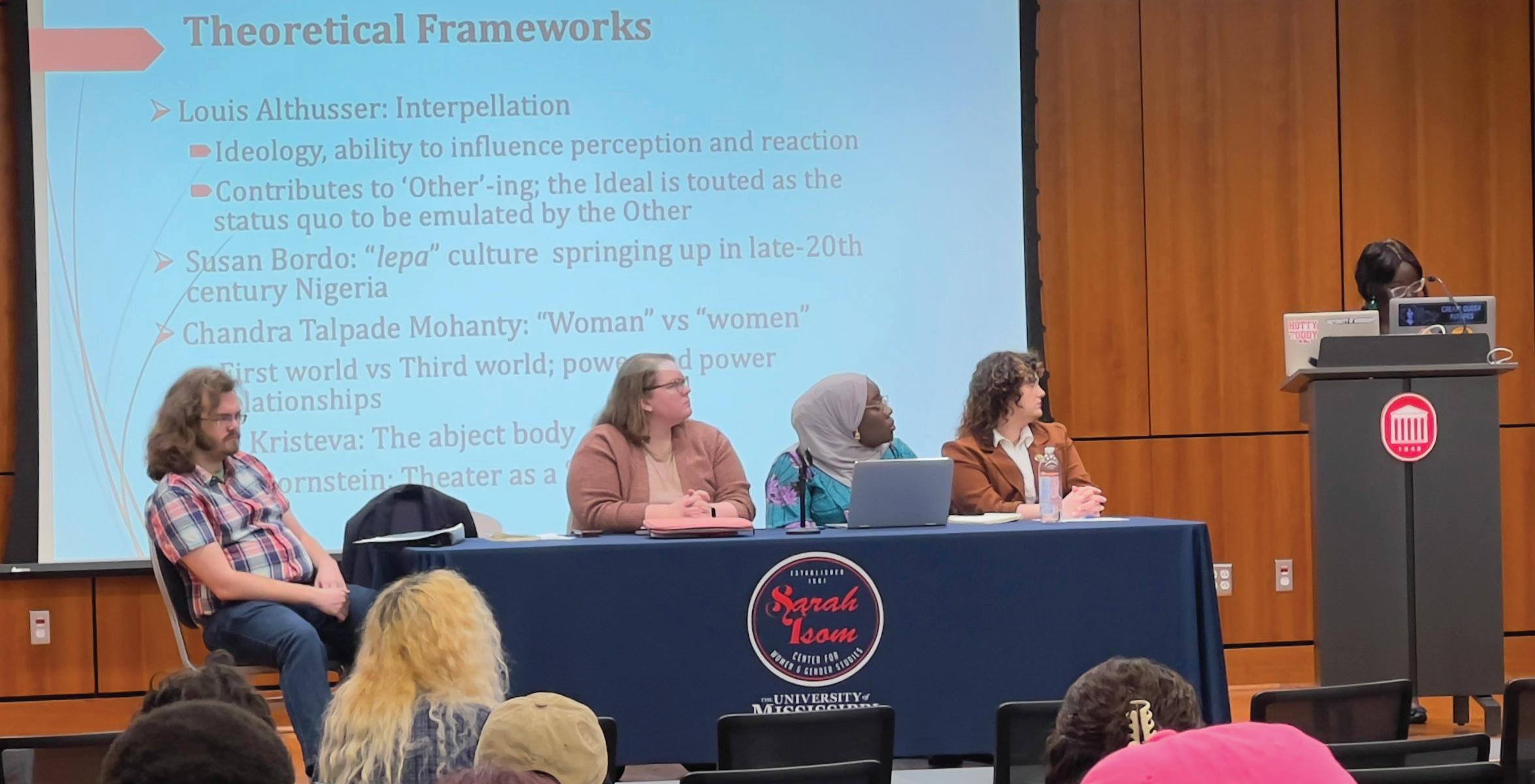

Below: The Isom Student Gender Conference featured undergraduate and graduate students presenting on the theme of Embodiment.

Itook on the role of Coordinator for LGBTQIA+ Programs and Initiatives in the Center for Inclusion and Cross Cultural Engagement in August 2022. While it was no secret that the political climate for queer people nationwide was becoming increasingly tense, the aggressive onslaught of targeted attacks on gender and sexuality minorities during the 2023 spring legislative session came as a shock. As of July 2023, the American Civil Liberties Union has reported 491 bills advanced this year, targeting LGBTQ+ people nationwide, with 25 of those bills introduced in Mississippi (and two passing). The stakes for interrogating university systems that disproportionately impacted LGBTQ+ students, while also modeling how to engage in resistance responsibly and further creating opportunities for queer students to experience joy, inspiration, and validation in the midst of political despair, felt dire. Encouraging a sense of belonging in a part of the country that was communicating increasingly more explicit intents for queer eradication challenged my heart.

As a staff member in a student-facing position, the character of my work differs from the academic- centered work of the Isom Center, though the goals of our work are often similar. I am not a professor of Gender Studies, though I frequently teach people how to engage with gender in new and expansive ways. I am not an activist, but I advocate for the change to make the University of Mississippi more hospitable and affirming of queerness. I am a representative of the University, but my strongest alliances are with the students, staff, and faculty who disrupt systems on campus that do not serve people who challenge traditional gender and sexuality expectations. It makes for a unique experience within a greater campus community.

I also do this work in the greater context of LGBTQ+ history. Queer history is a legacy of disruption and resistance through diverse strategies, many of which don’t fit conventional expectations for professionalism. Queerness embraces diffi-

culty, willfulness, and strangeness. It demands persistence, humor, and creativity. As I navigate the delicate balance between role modeling as a queer adult and role modeling as a representative of a flagship university, I often recall Sara Ahmed’s definition of the feminist killjoy:

A killjoy: the one who gets in the way of other people's happiness. Or just the one who is in the way—you can be in the way of whatever, if you are already perceived as being in the way. Your very arrival into a room is a reminder of histories that "get in the way" of the occupation of that room.

Modeling professionalism to the students I work with and modeling a killjoy philosophy often feel at odds with one another. In a social climate that makes a political talking point of the rights and existence of the communities I serve, demonstrating the unwavering support I expect of someone in my position requires strategic precision and vigilance. It also requires partners.

The creative and willful work of the Isom Center exemplifies this philosophy of “getting in the way” in a style I admire and appreciate, especially from the vantage point of the inner workings of a university. Together this year, we tackled creating opportunities for queer affirming student housing through continued work on the Lavender LLC. We invited academics and professionals to campus who demonstrated routes to authentic professional success as a queer person, including Washington Post journalist and author Casey Parks. We collaborated to honor over 30 graduating students at the 8th Annual Lavender Graduation.

Most significantly to me, however, we have built a partnership built on trust, candor, respect, and understanding, which only serves us as we envision future strategies for queer worldmaking at the University of Mississippi. Forging my own style in LGBTQIA+ student services has been a rigorous and introspective journey, and one that is by no means finished. As such, Jaime, Theresa, Kevin, Nora, and all the Isom Center partners and co-conspirators have been and continue to be valuable accomplices.

by Jaime Harker & tHeresa starkey

by Jaime Harker & tHeresa starkey

The cost of gender is largely invisible in the mainstream and rarely discussed in the media, but one’s gender frequently comes with a real cost–not only in terms of money. Gender causes stress, limits access, creates barriers to advancement, and prevents opportunities from materializing. Some of these losses and barriers you can see, but sometimes you don’t know about other possibilities because they are never shown to you.

We inherit, in Western cultures like the United States, a binary gender system at birth. It is presented as a ‘natural’ system, one that defines femininity and masculinity in specific, essentialist ways, and insists that all people are exclusively defined as one or the other. The gender binary, of course, isn’t natural; it is a gendered ideology, one that is raced, classed, and grounded in nationalism and cultural specificity. Though this gender system manifests differently in particular nations, regions, hemispheres, and languages, the language we use to describe gender suggests that it is fixed, unchanging, and an objective description of a natural, God-given order.

To talk about the gender system as an ideology is not to ignore the body; it is, rather, to see how our understanding of the body is mediated by this ideology. Biologists, for example, quantify gender variance: there is a huge disparity of size and appearance of what we term “sex characteristics,” variance that we obscure when we talk about “two genders.” There are also a statistically significant number of babies who are intersex, who are born with XXY or XYY chromosomes, or whose sex is not easily determined; this condition is often “corrected” surgically based on appearance, not chromosomes. Extensive plastic surgery, hormones, and other body modifications are often performed on those with XX chromosomes to be more “feminine” or those with XY chromosomes to be more “masculine.” We frequently discipline the body to match our ideological expectations, rather than acknowledging the huge range of gender variance in our “natural” state.

We are encouraged to understand ourselves through the binary system and internalize those ideologies. We know the social script of gender that we are expected to perform, and we know the consequences of not adhering to that script. We are interpellated as male or female; Louis Althuss-

er defined interpellation as the moment the state, through its pervasive ideology, names you as a particular identity. When, for example, a policeman says “Hey you!” and you turn in response, you have been interpellated by the state.

We are interpellated by the gender binary system from our earliest moments. All of us can name some moments where we were interpellated by the gender system. Just in the office, we share these examples: Kevin’s mother bought him a Barbie to practice brushing hair, and when he enjoyed that present, his father tried to counteract it by buying him a shotgun that was taller than he was. When Theresa went to the playground with her short hair, pants, and Star Wars shirt, the other girls and boys said to her, “You aren’t a girl! You are a boy!” She had to claim she was a girl, when really she enjoyed that androgynous freedom before it was labeled. Jaime was forced to wear a skirt to her weekly church youth meeting on Wednesday, so she replaced her jeans with a wraparound skirt but kept her tube socks, tennis shoes, and t-shirt exactly the same, scandalizing the church ladies. There are countless moments like these, a repetition of gendered interpellation that forms a seemingly inescapable web. Whether we are punished for not conforming or starved by conforming all too well, all of us pay the price of being in such an inflexible ideological system, one which strives to define the terms and limit the conversation.

Can we imagine a world beyond this gender binary system? As Riki Williams argues in the ground-breaking anthology, Genderqueer, transgressing the conventions of the gender binary provides “a hint of another kind of person we might have been if only we didn’t inhabit a world where every one of eight billion human beings must fit themselves into one of only two genders” (13). The costs of masculine, feminine, trans, and genderqueer are multiple and various, but they all stem from the same system. How do we account for these costs? What are their long-term effects? How do we make them visible and how do we lessen them?

The articles below are by no means exhaustive, but they serve as case studies that reveal the hidden cost of gender. Before we can imagine a world outside the ideology of the gender binary, we need to see and account for the costs of the system we occupy. We hope to continue this exploration throughout the coming academic year.

A pay gap is simply a difference in earnings between two or more groups of people. Pay gaps based on gender, race, and ethnicity are well documented. Recent reports indicate women in the USA earn approximately 82% of that of men. While this gap narrowed over the last two decades of the 20th century (up from about 62%), progress stalled during the first two decades of the 21st.

There are a host of identifiable factors that contribute to gendered pay gaps, including occupation, education, experience, productivity, division of family labor, and risk tolerance. Researchers find “unexplainable” differences in pay potentially attributable to discrimination, even when controlling for such factors.

Our governments can, and have started to, implement legislation that protects employees seeking pay equity and policies that reduce gender stereotypes in career and education choices. Pay transparency interventions involve prohibiting employers from asking about salary history during the hiring process and from retaliating against employees who seek or share salary information. Currently, only 22 states have such protections. Forty-nine states have Equal Pay protections, with Mississippi being the only outlier.

Our employers can take proactive steps to address pay gaps. This includes conducting frequent pay audits, implementing practices that promote transparency in pay, and providing family-friendly workplaces (e.g., child and elder care, and after-school activities).

We can also contribute to pay equity. We can engage with supportive networks, advocate for effective public and employer policies, and help new employees negotiate equitable pay when starting a job.

Kevin

In addition to the Wage Gap that already harms women’s financial well-being, women are also subject to the “pink tax,” one of the most visible and

quantifiable costs of gender. “Pink tax” is the term that refers to the added cost that mostly women have to pay for items and services that 1) are marketed towards women that often do the same job as products targeted to men but cost men less or that women have to use more often or 2) that women are required to spend money on that men don’t have to. Examples of the former are shampoos, body wash, or razors targeting women. The latter are things like “feminine hygiene” products.

According to an article on Bankrate.com, “pink tax” became the term of choice for this phenomenon “when the Gender Tax Repeal Act of 1995 passed in California, prohibiting price discrimination on services.” Per the California Senate Committee on Judiciary and Senate Select Committee on Women, Work & Families in 2020, “Californian women pay an average of about $2,381 more, for the same goods and services, than men per year. That can add up to about $188,000 in pink tax throughout a woman’s life.” The impact of the “pink tax” is only exacerbated in times of significant inflation.

Another example of the Pink Tax is the traditionally gender-based cost of hair treatment services where women’s haircuts cost more than men’s. There has been a recent movement to eliminate this tax as more progressive stylists have moved to a time-based fee system rather than a gender-based one. While this is a step in the right direction, more needs to be done to eliminate the "pink tax" entirely.

anne Klingen (outreach)

Throughout history, women have faced numerous challenges when it comes to their rights. The United States has seen significant transformations in women's property rights over time, reflecting the changing dynamics of society and legal frameworks. I would like to explore the historical progression of those rights in the United States and highlight a few milestones.

From the founding of the U.S. colonies to the beginning of the 19th century, women continued to have limited rights under the British common law Doctrine of Coverture, in which a married women’s legal existence was subsumed by her husband, meaning her property, her earnings, and her ability to act freely were all subject to her husband’s au-

thority. However, the mid-19th century witnessed a variety of social movements such as abolition and suffrage. In 1848, the Seneca Falls Convention marked a crucial turning point by advocating for equal rights for women. This advocacy paved the way for legislative reforms that aimed at improving gender equality. New York's Married Women's Property Act of 1848 granted women the right to control their own assets, separate from their husbands. Many states followed New York’s example and passed legislation between 1848 and the early 20th century allowing for further advancements in women's property rights, such as married women owning separate real estate and managing their finances without interference from their husbands and protecting the inheritance rights of widows.

In the mid-20th century, the resurgence of the feminist movement led to new reforms in women's property rights. In 1974, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act prohibited discrimination based on sex in financial transactions, allowing women to open bank accounts, obtain credit cards, and commit to loans and mortgages without male co-signers.

Women's property rights in the US have undergone a significant transformation over the centuries, from being tied to their husbands to having control over their own assets. But more work can be done. The Bureau of Labor Statistics 2021 reports indicate that women earn $0.83 for every dollar a man makes. The 2018 Survey of Income and Program Participation by the US Census Bureau reports that 50% of women aged 55 to 66 have no personal retirement savings.

Kenya wolF (counselor education)

For far too long, there has been a lack of female representation and an underfunding of women’s health issues in medical research. This led to large gaps in knowledge about women’s health issues such as endometriosis, menopause, and reproductive health. For instance, there is five times more research on erectile dysfunction, which affects 19% of men, than on premenstrual syndrome, which impacts 90% of women. Access to birth control is a game-changer; women who report its use have improved their health (63%), completed their education (51%), or maintained or obtained a job (50%). Yet, a third of women report struggling with access and/

or affordability of prescription birth control and therefore, have used birth control inconsistently as a result. Prescription birth control is used exclusively by women and thus its cost disproportionately impacts women, especially low-income and/ or minority women.

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated health insurance companies make birth control available without a co-pay, but this requirement has been under attack by anti-birth control politicians. Many states are also restricting and limiting sex education in schools and promoting abstinence-only programs. An HHS-funded analysis showed the more policies emphasize abstinence-only programs, the higher the incidence of teen pregnancies. In this new post-Roe versus Wade landscape, we need to be asking how we can build better systems to support women and the projected over 150,000 new babies who could be born annually. This new influx of births will no doubt disproportionately impact women from the high cost of prenatal & maternity care to childcare.

Many women work hard to grow both their careers and their families, and often during the same years: in fact, 70% of mothers also work for pay. A key challenge for these women is what sociologists call the motherhood penalty, which describes the fact that women’s pay decreases once they become mothers.

New findings from the Pew Research Center show that the gender pay gap, which has barely closed in the US over the past 20 years, is exacerbated by the motherhood penalty vs. what is known as the fatherhood wage premium. Upon becoming parents, fathers experience an increase in pay, while mothers are less likely to be hired, promoted, or paid equally.

Children and families, not just women, pay the price, and low- income women workers suffer the most from the motherhood penalty. High-income fathers receive the biggest bump in pay and confidence upon becoming parents, while low-wage women with children under 6 – whose salary is eaten up by child care – are hit hardest.

When we don’t support mothers in the workplace, our work suffers, too. Almost twice as many working Americans describe working moms as better listeners, calmer in crisis, more diplomatic, and better team players than any other peer group—all important qualities for a leader. Yet bias against mothers in the workplace is so pervasive that it even affects women without children, making the motherhood penalty a lose-lose proposition for women in general.

An analysis of parental-leave policies in the EU found that when childcare is “no longer considered the sole domain of women and more fathers take parental leave to stay at home and look after their children in their first year, the outcomes for gender equality include increased women’s labour-market participation, reduced gender pay gaps and increased men’s participation in household work.”

Ironically then, a key factor in mitigating the motherhood penalty may be in developing and promoting gender-equity policies not to women, but to men.

An added benefit of adopting the flexible work options, child care support, and family leave that would support working mothers—and offering those programs to all employees—is that the percentage of women and people of color in management increases, with a larger impact than the most popular race-equity programs.

Now that’s a win-win-win.

shelli Poole (viP: survivor suPPort)

The cost of being a woman in our society is high due to the degree and pervasiveness of sexual violence, and for people of color, members of our LGBTQIA+ community, people with lower socioeconomic status, and differently abled, the cost is even higher. Gender-based violence has been declared a public health crisis by the CDC, and it continues to be an issue on college campuses across the U.S. According to the CDC, over half of women have experienced sexual violence. The Rape, Abuse, & Incest National Network (2021) stated that about 1 in 5 college women, and 1 in 16 college men, are assaulted every year. Also, approximately 23% of transgender, non-conforming (TQNC) students are assaulted. Sexual violence on college campuses has received increasing attention; therefore, efforts to raise awareness of these issues, prevent them, and to support survivors following an incident have also been developing. Sexual violence has long-term impacts psychologically, financially, socially, and physically, according to the National

Sexual Assault Resource Center (2021). Some of the approaches to prevention have been bystander intervention, rape resistance programs for women, consent education for men, and addressing societal power differences in intimate relations on college campuses. Research is still ongoing to better understand how to address this public health crisis, but it is clear that until the roots of oppression are addressed, women and other people with lower levels of societal power will continue to be victimized. The root of sexual violence is power and control which is one person exerting power and control over another human being. Issues of power and identity also need to be further woven into the prevention education programming on college campuses to address this public health crisis.

A groundbreaking study on campus sexual assault by Hirsch and Kahn (2020) discusses the role of societal power in intimate relations. They found that different people have different levels of power depending on their gender, race, class or other identities; unequal power dynamics make consent more complicated. They stated that most social gatherings occur in fraternity houses, and in those settings, the men would have more power. This study also addressed how people of different identities are impacted by sexual violence in ways that have not historically been addressed in the campus sexual assault prevention literature. The Hirsch and Kahn (2020) research addresses the question of which groups are most vulnerable to sexual violence on a college campus, and for women and gender nonconforming students, the impact is significant. At the University of Mississippi, we need to promote social norms that prevent violence, address power inequities, and educate every student, faculty and staff member, and administrator on the impact of trauma, violence, and oppression.

Full bios & additional resources online

by norris "eJ" edney

by norris "eJ" edney

Iremember my transition to this institution fondly. One of the first people I met when I decided to enroll in the University of Mississippi in 2007 was myself. The faculty, staff, and students here seemed to really care about me and my needs. And yet I quickly learned that for me — and other students from marginalized backgrounds — being successful here would require us to learn, understand, value, and articulate the richness each of us contributed to the diversity of this institution by way of our intersecting identities and the lived experiences they inform.

Intersectionality refers to “the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender as they apply to a given individual or group” and is “regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage.” It is why I felt so out of place at my first football game here. Here I was, a first-year student who listened in confused amazement as what seemed like 10,000 of my newest friends and colleagues half sang and half yelled “The South will rise again” to the tune of the closing measures of “From Dixie with Love.” I was deeply conflicted. I wanted nothing more than to be in on the traditions of this place, and to love them like some of my friends seemed to. This seemed a necessary prerequisite to full membership in the “Ole Miss Family.'' However, through deep self-reflection, I realized that as a black man from Mississippi whose grandfather was a sharecropper in the Delta,

embracing that particular tradition and others that seemed to encourage us to romanticize a past in which marginalized folks were dehumanized was too high of a membership fee for me. I wanted to understand how I and these other members of my collegiate community could have such vastly different interpretations of such symbolism. The curiosity and learning resultant from that experience crystalized for me the reality that we hold multiple identities all of which contribute to the ways in which we perceive ourselves, each other, and the systems and structures we navigate together as communities.

Now as Assistant Vice Chancellor for Diversity and Inclusion, I create programs and provide services that help individuals and groups do the work of considering how their individual identities, perspectives, biases, and culture influence their relationships with other individuals and groups and how those interactions ultimately shape participation in the system that is the University of Mississippi. It is my hope that dedicated work in this space will continue creating pathways to belonging for students, faculty, staff, and community members who chose this place to produce and acquire the knowledge and tools they’ll use to build our collective futures.

by kevin Cozart

by kevin Cozart

The Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies, with our partners the Department of Music and Living Music Resource, welcome multigenre artist Elizabeth Ito as our third annual Sarahfest Artist-in-Residence. Elizabeth will be in Oxford from Nov. 5 - 11 working with a cohort of students to explore the intersections of place and history. During Elizabeth’s residency focusing on “The Art of the Unexpected,” there will be several opportunities for the public to interact with her, including an LMR Live, a screening of her Netflix show City of Ghosts, and more

“The Sarahfest Residency program has proven to be an opportunity for transformational development at the University of Mississippi,” states Nancy Maria Balach, chair of Music. “As we prepare for year three, I am so excited to welcome Elizabeth Ito to our beautiful place where an interdisciplinary group of students will explore and create with Elizabeth, and then share their Art with our community in unexpected ways.”

Elizabeth Ito has been working as a creator, writer, director, and storyboard artist in the animation industry since 2004. She’s worked on TV, feature, and commercial projects. Elizabeth is also the creator of the award-winning short, Welcome to My Life, the second-most viewed short in Cartoon Network history. She also received an Emmy for her directing work on Adventure Time. Her first series, City of Ghosts for Netflix premiered in 2021 and won a Peabody Award, and two Emmys for directing and best-animated children’s show in 2022. She also directed a music video for The Linda Linda's and is on an overall deal with Apple TV. Currently, she is living in Los Angeles, working from home, and trying to stay hydrated.

September:

The annual art show at the Powerhouse Community Arts Center once again kicks off Sarahfest. This

year’s show focuses on the work of UM students: Paul Mora, Maggie Muehleman, and Itunu Williams. Joining the students’ work will be an exhibit from the University’s Archives and Special Collections, curated by Greg Johnson. The Art Show Reception, scheduled for September 19th at 6:30 PM, will include a table read of Williams’ play.

November:

Poet Joshua Whitehead will present the annual Queer Studies Lecture on November 2 at 4 PM. Please see page 16 for more information on Joshua and the lecture.

Visit sarahfest.rocks for more information and a full schedule of events.

oCtober 19, 2023 • 4pm

The ACE Studies Lecture was established in the spring of 2022, to coincide with the Glitterary Festival, a queer literary conference. We subsequently moved this lecture to the fall, to coincide with asexuality week at the end of October. This year’s ACE Studies Lecture will be delivered by KJ Cerankowski. The title of his talk is "Wanting Nothing or Nothing Wanting? Asexuality, Desire, and the Matter of Absence."

KJ Cerankowski is an interdisciplinary scholar and writer with research interests in asexuality, trauma studies, queer theory, and transgender studies. He is the author of several articles, including the 2021 Symonds Prize-winning essay “The ‘End’ of Orgasm: The Erotics of Durational Pleasures,” published in Studies in Gender and Sexuality. His poetry and prose have been published in DIAGRAM, Pleiades, Entropy, and The Account, among others. He is the coeditor of Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives (Routledge 2014) and the author of Suture: Trauma and Trans Becoming (Punctum 2021).

november 2, 2023 • 4pm

The Queer Studies Lecture was established in 2014, connected with the development of the queer studies emphasis in the Gender Studies minor. This fall’s Queer Studies lecture will be given by Joshua Whitehead. Whitehead’s lecture will also serve as the Center for Inclusion and Cross Cultural Engagement’s Native American Heritage Month Lecture.

Joshua Whitehead is a Two-Spirit, Oji-nêhiyaw member of Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1). He is currently a Ph.D. candidate, lecturer, and Killam scholar at the University of Calgary where he studies Indigenous literatures and cultures with a focus on gender and sexuality. He is the author of full-metal indigiqueer (Talonbooks 2017) which was shortlisted for the inaugural Indigenous Voices Award and the Stephan G. Stephansson Award for Poetry. He is also the author of Jonny Appleseed (Arsenal Pulp Press 2018) which was long listed for the Giller Prize, shortlisted for the Indigenous Voices Award, the Governor General’s Literary Award, the Amazon Canada

First Novel Award, the Carol Shields Winnipeg Book Award, and won the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction and the Georges Bugnet Award for Fiction. Whitehead is currently working on a third manuscript titled, Making Love with the Land, to be published with Knopf Canada, which explores the intersections of Indigeneity, queerness, and, most prominently, mental health through a nêhiyaw lens.

marCH 21, 2024 • 4pm

The oldest of the our annual lectures, the Lucy Somerville Howorth Lecture was established in 1991 to honor the life and career of Lucy Somerville Howorth, who was one of the first women to receive a juris doctor from UM. The endowed series brings distinguished speakers to the campus in the area of women’s and gender studies. During her life, she served the State of Mississippi in the executive and legislative branches, including being the first woman to represent Hinds County in the state legislature, and in the Federal Government. She was also heavily involved in the American Association of University Women, which endowed the lecture series in her honor. This year's Howorth Lecture will also serve as the keynote for the Isom Student Gender Conference.

Dr. Alex Ketchum is the Faculty Lecturer of the Institute for Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies of McGill University. She is the author of two books: Engage in Public Scholarship!: A Guidebook on Feminist and Accessible Communication, and Ingredients for Revolution: A History of American Feminist Restaurants, Cafes, and Coffeehouses She is currently working on a book about the relationship between feminist ethics and AI. Her lecture will discuss how gender and sexuality research circulates in public forums, with her own work on feminist restaurants as a case study.

Kadji Amin

apriL 11, 2024 • 4pm

The Trans Studies lecture was established in 2021, growing out of a Trans Summit hosted by the Division of Diversity and the Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies in 2019. This year’s lecturer is Kadji Amin.

Kadji Amin is Associate Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Emory University. He is the author of Disturbing Attachments: Genet, Modern Pederasty, and Queer History (Duke University Press, 2017), which won an Honorable Mention for the Alan Bray Memorial Award for best book in LGBT studies. Disturbing Attachments uses Genet to interrogate the desires that orient the field of Queer Studies. It demonstrates how contemporary queer attachments to non-normativity, sexual transgression, and political radicalism bear the stamp of recent gay American history. Ultimately, the book challenges scholars to disturb the desires of Queer Studies so that the field can reorient itself to an expanded range of geographic, historical, and racial subjects. This requires, first and foremost, challenging the idealizations of queer theory. Kadji is currently at work on two book projects: Trans Materialism without Gender Identity, an academic monograph that critiques gender identity as a midcentury psychiatric construct that has historically done transgender people more harm than good; and Brown Trans Misfit, an experimental memoir that upends the conventions of trans narratives.

The Isom Center's Lecture Series are sponsored by the College of Liberal Arts, the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement, the Lucy Somerville Howorth Lecture Fund, the Isom Arts, Culture, and Community Development Fund and others.

The Sarah

Isom Center for Women andGender

Studiesat The University of Mississippi is pleased to announce its 24th Annual Isom Student Gender Conference (ISGC). The ISGC is scheduled for Wednesday, March 20, through Friday, March 22, on the campus of The University of Mississippi in Oxford, Mississippi.

As a term, intersectionality was coined in 1989 by a law professor who sought a nuanced way to represent the complex interactions of bias, racism, sexism, and exclusion: rather than deciding whether someone was being discriminated against as a woman OR as a person of color, Kimberle Crenshaw argued that we need more nimble interpretive tools to comprehend the ways that oppression is not either/or but multiple. But the notion that our identities are complex, that we can be, simultaneously, privileged and excluded, goes back much further, to the earliest days of Black liberation, women’s liberation, and gay liberation. Our lived experience matters; our identities are mediated by larger ideological forces, and the bias that frames a certain identity as the norm and excludes others for not adhering to that norm affects all of us profoundly. To see the many ways these inequalities function, we have to name them, notice them, and confront them.

Grounded in recent Supreme Court cases and legislative agendas, a counternarrative has been circulating in recent years, that the naming is the problem. If we stop noticing, stop counting, stop seeing, then the problem (racism, sexism, homophobia, classism) will simply go away. If the courts and the law refuse to see color, for example, then no one else will, either. And increasingly, politicians want to censor what universities can teach, what theories are available, what histories can be taught and acknowledged, to make that imaginary ‘truth’ stand in for the complex realities of the in-

The Isom Center has long fostered fearless inquiry into the complexities of culture, history, and ideology; we believe that free speech and relentless curiosity are the foundation of academic inquiry. Pretending that inequalities don’t exist unless we name them is not a replacement for rigorous scholarly investigation. Trying to define the terms to exclude whatever makes you uncomfortable may be a debater’s trick, but it is not the way a mature culture, invested in creating liberty and justice for all, approaches the creation of knowledge.

At this year’s Isom Student Gender Conference, we invite participants to submit papers, performances, and presentations that explore inequalities and their intersections. Students are welcome to submit papers from all disciplines, along with creative writing projects such as fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Additionally, proposals for roundtable discussions that center on community building, advocacy, and social change both on and off the campus through the arts, social media, and student engagement with broader communities are encouraged.

Submission deadline is February 3, 2024. A small number of domestic travel grants will be made available to non-UM students. To learn more, visit isomstudentgenderconference.org.