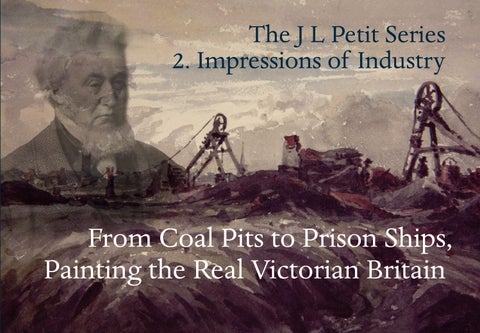

The J L Petit Series

2. Impressions of Industry

From Coal Pits to Prison Ships,

Painting the Real Victorian Britain

From Coal Pits to Prison Ships, Art of the Real Victorian World

The second in the series, this collection showcases the strikingly modern views of 19th century Britain by John Louis Petit (1801-68). As the son of a Black Country landowner, Petit witnessed the emergence of mines, furnaces and factories on a scale never seen before. His family’s wealth gave him the freedom to paint what he saw, not nostalgic landscapes such as the market demanded. His unique talent, anticipating Impressionism, created works of art that still resonate today. Twelve from the Black Country and elsewhere are introduced in this booklet and form a limited edition set of prints. Contact enquiries@revpetit.com RPS Publications www.revpetit.com

Introduction to Petit’s Industrial art

“Industrial paintings in the nineteenth century are exceptionally rare. Petit’s significance is that he created a tradition of industrial images of the Black Country and beyond. He depicted the grandeur of foundries, factories and mines and their relationship with their surroundings, celebrating the power of modern manufacturing while simultaneously lamenting its brutal environmental and human impact.”

Malcolm Dick OBE, Chairman, Black Country Society, 2025

About John Louis Petit

JL Petit MA (Cantab), MA (Oxon honorary), FSA, Fellow of RIBA, was the leading opponent of the Gothic Revival in architecture from 1841 until the 1860s. He was also a nationally known artist who exhibited widely at his public lectures but never tried to sell. After his death his work was lost until the 1990s.

“There has been nothing like this in the field of British art for a long time - the rediscovery of a more or less completely forgotten master. Petit is a prophet of Impressionism, a true ‘painter of modern life’, whose work reaches the highest peaks of innovation and virtuosity, worthy of comparison with that even of Turner. High praise, but not too high.”

Andrew Graham-Dixon, art historian and broadcaster, 2025

Reverse: 1. Near Wolverhampton, 27 x 37 cm, 1852 or 1853.

Believed to be one of the large works at Spring Vale, Bilston, painted from close to the junction of Parkfield Rd and the Dudley/Wolverhampton Rd, near the boundary of Petit’s estate. A unique view of the reality of Victorian England juxtaposing the power, and poisons, of modern life, which still resonates today.

Reverse: 2. Near Wolverhampton, 14 x 20.5 cm, c. 1830-35.

Mine scaffoldings to the west of Dudley, overshadowing two churches, possibly St Edmund’s and St Thomas’s, in the distance. The destruction of the landscape by spoil from the mines in the foreground. This and the next two pictures are in a dark palette which Petit deployed throughout the 1830s.

Reverse: 3. Near Wolverhampton, 23 x 32 cm, c. 1830-35. From the Bilston area.

Believed to be the earliest known picture of one of the new furnaces.

Architectural power is on full display, and detailed depictions of ancillary buildings in front and behind. The ruined landscape in the foreground possibly includes tram tracks and a canal basin.

Reverse: 4. Near Wolverhampton, 16 x 21.5 cm, c. 1830-35. Possibly a distant view of the Spring Vale ironworks, taken from the top of a stagnant-looking Penn Brook. Other chimneys are also in the distance, with agricultural land in the middle ground between the two.

Reverse: 5. Sydenham, 37 x 27 cm, 1853 or 1867. The Crystal Palace.

Technically an extraordinary accomplishment to convey the metal and glass structure. Other artists depicted it almost exclusively from outside and at a distance. Petit is believed to have completed around 20 pictures of the Crystal Palace which remained unknown until recently, some with similar views to the renowned photographs of his friend Philip Delamotte.

Reverse: 6. Llandudno, 27 x 37 cm, c. 1853.

The Great Orme Mine - the only known picture of one of the largest copper mines in Europe, which dated back to prehistoric times. Eventually it would close in 1881. As with the furnaces, Petit makes an attractive landscape while remaining true to the chosen scene.

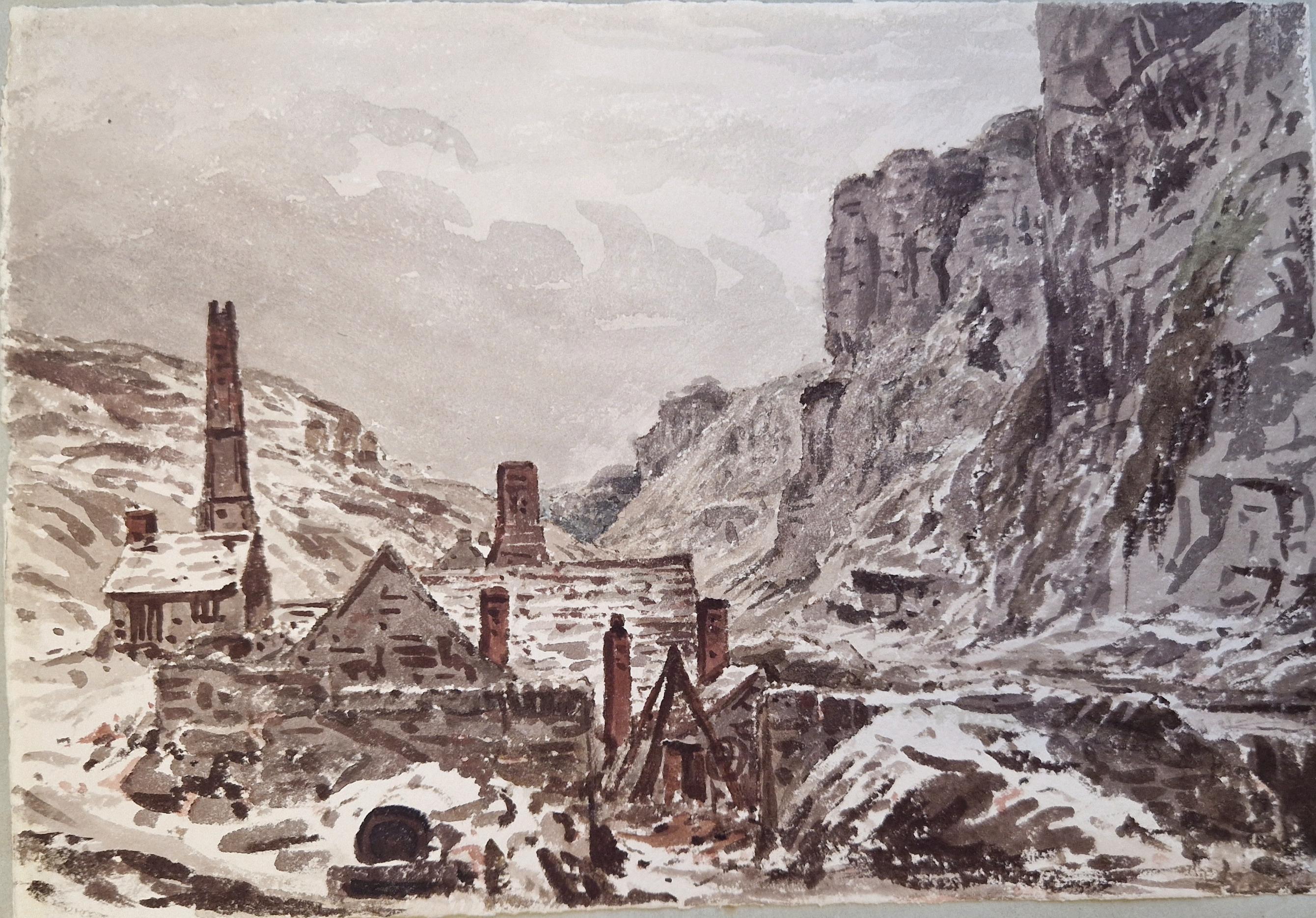

Reverse: 7. Stoney Middleton, 22 x 33 cm, c. 1836.

©Derbyshire County Council: Buxton Museum and Art Gallery.

The Lord’s Cupola lead smelting furnace. One drawing of the building from 1817 exists, but this is the earliest known artwork of the important facility and its surroundings, in winter, with the characteristic peaks behind. Remnants of it exist today on the A463 (Georgia Wild).

Reverse: 8. Low Moor, Bierley, 27 x 37 cm, April 30th 1857.

The largest ironworks in Yorkshire, of which one other, classical, picture from this date is known. Low Moor made wrought iron products from 1801 until 1957 for export around the world. Petit here presenting a less dramatic view than the earlier furnace pictures.

Reverse: 9. From Waterloo Bridge, 23 x 33 cm, c. 1835. Watts Shot Tower, Lambeth. Echoing Italian or Venetian scenes, Petit contrasts the factory for making lead shot, and its campanile-like tower, with the silhouette of St Paul’s shimmering through the smog - from the bridge named after the battle of Waterloo, fought only 20 years previously. A rare picture of the earlier of two shot factories located on the South Bank.

Reverse: 10. Furnace, 24 x 34 cm, c. 1850.

The small but important Dyfi ironworks near Machynlleth, in North Wales. The only known rendering mid-century, it also demonstrates how utilitarian architecture can be picturesque. Built around 1755, it stopped functioning as a blast furnace in 1810 and converted into a sawmill at an unknown date.

Reverse: 11.

a) Swithland, 10 x 10 cm c. 1830.

A small, possibly unique sketch of the Swithland Great Pit, an important source of slate for the East Midlands. Perhaps the earliest of Petit’s pictures of industrial scenes.

b) Sheerness, 8 x 17 cm, c. 1830. Prison hulks off the Isle of Sheppey. The right hand hulk is believed to be the Bellerophon, set aside for children as young as 8. A little recognised aspect of Victorian life, introduced to ease overcrowding at low cost. The National Archives reports a 25% death rate on prison hulks.

Reverse: 12. From K’s [King’s] College, 1863, 27 x 37 cm.

Petit often portrayed smoggy cityscapes, showing how industry intertwined with the more traditional buildings. Edinburgh, Paris, Bath and others are known. Here, London thirty years after picture 9. Possibly one of the most revealing representations of Victorian Britain, neither romanticised nor idealised, raising issues of modernisation, development and pollution that foreshadow our own times.

Petit on the Architectural Value of Modern Structures

“Usefulness and economy may not only be consistent with artistic excellence, but actually tend to the development of much that is grand and beautiful. If picturesqueness is a merit, I can answer for it that the most picturesque objects I have seen are buildings of the most strictly utilitarian character, without a speck of ornament, and you may be sure erected at no more cost than was deemed necessary, without the slightest attention whatever to appearance. I speak of the furnaces in the neighbourhood of Wolverhampton. Some of these taken as buildings independently of their accompaniments of fire and smoke, are absolutely grand...”

JL Petit, 1856

The Context of Petit’s Industrial Art

“Artists prior to Petit are known for their rural landscapes. JMW Turner was an exception, but his images of Dudley reveal his interest in the interplay of light, smoke and flames rather than in creating an authentic picture of industrial sites. Subsequently, Richard Samuel Chattock (1825-1906) produced etchings illustrative of the coal and iron district in South Staffordshire (1887), and Edwin Butler Bayliss (1874-1950) painted Wolverhampton blast furnaces and their brutal environmental and human impact at the end of the century. In the 1830s-50s Petit was a pioneer when other artists eschewed such depictions.”

Malcolm Dick OBE, 2025

“What is also extraordinary about Petit’s work is the breadth of his subject matter and his remarkable lack of sentimentality. Few Victorian artists chose to bear witness to the effects of the Industrial Revolution on the fabric of life in this country, but Petit did anything but shy away from it… To look at his work is to see a familiar world changing out of all recognition, and to understand the pace at which it was happening. In this sense he is a prophet of Impressionism, a true ‘painter of modern life’, to borrow a phrase from Baudelaire.”

Andrew Graham-Dixon, 2022

RPS Publications www.revpetit.com

All images are of watercolours by JL Petit, in private collections except where stated

All rights reserved

Design: sarahgarwoodcreative.com

Printed by: Gemini Digital

ISBN no: 978-1-9164931-4-8

© 2025 Philip Modiano

The greatest rediscovery in

British Art for a generation Andrew Graham-Dixon, 2022