photography

Press Designer writers

Cover art typefaces

Sara Edwards

Bell Telephone

Darrell davidson

getty images

theartstation.uk

U.s. National archives

Greg Daugherty

kim guise

jeff nilsson

AT&T Archives & History center

Blurb

American Typewriter

arial

Articha

bebas neue

Impact Label

Impact label reversed

Minion pro

Dear Reader,

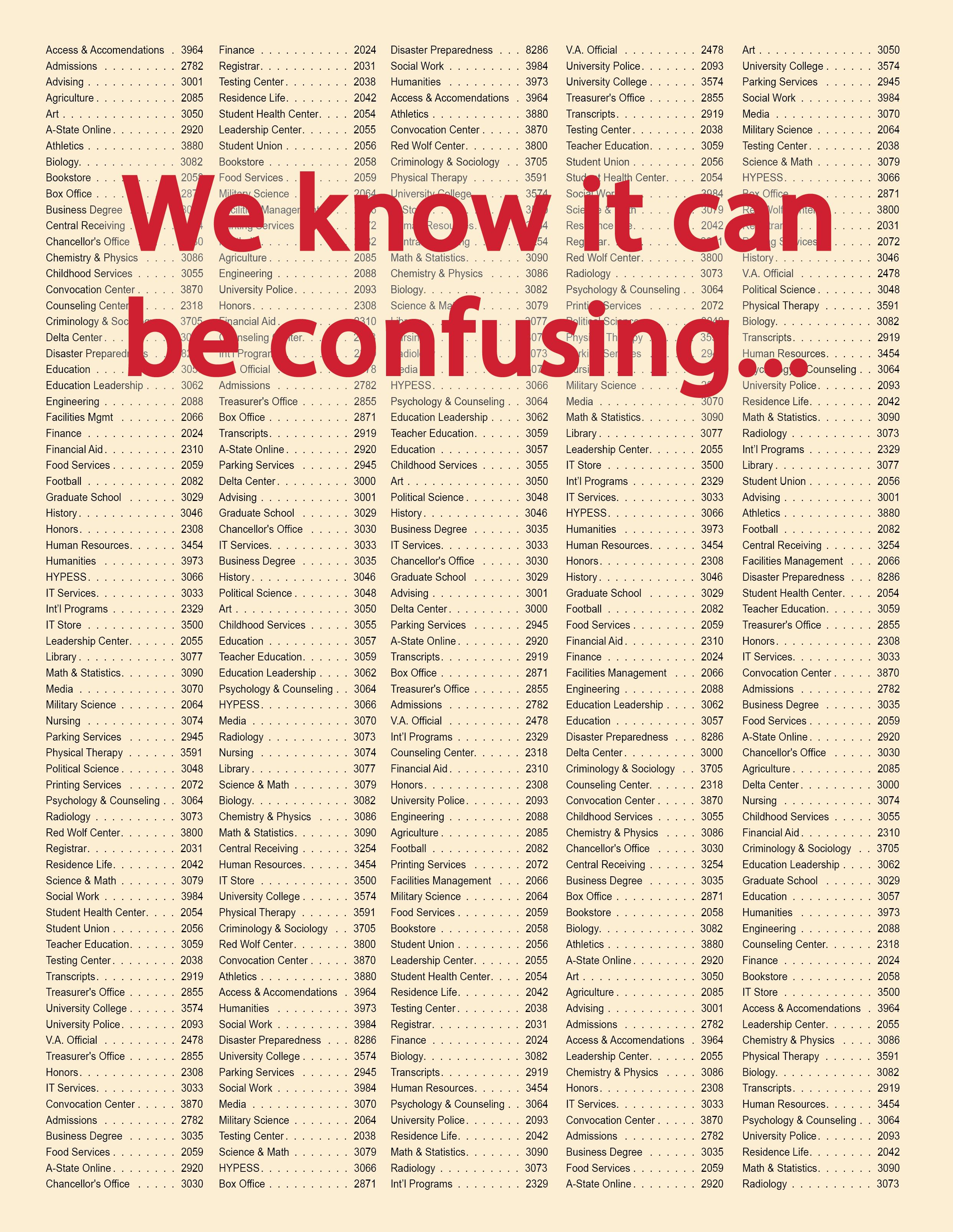

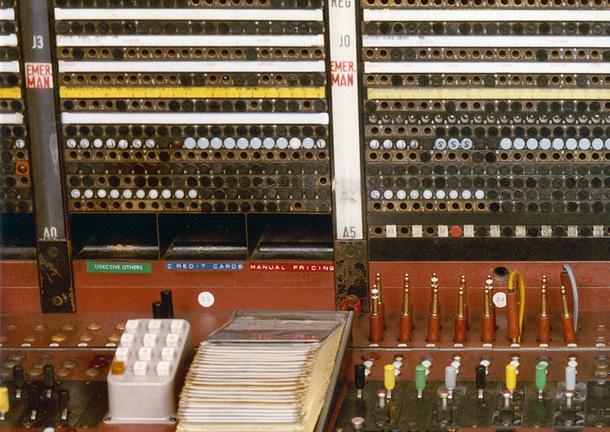

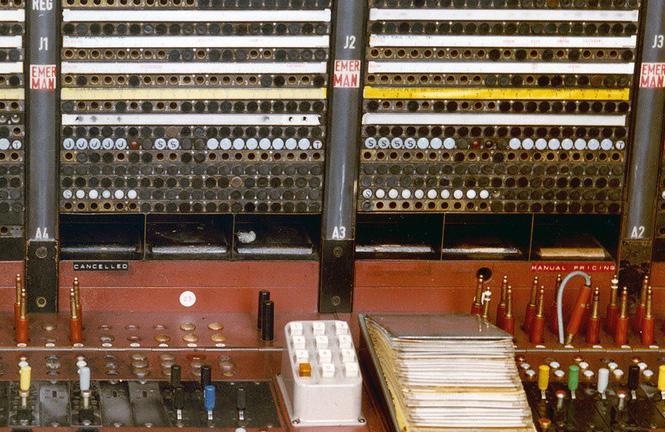

Switchboard

Fall 2022

The role of the switchboard is to connect people. Here at Switchboard magazine, we aim to connect you with content that interests you. While the history of the telephone is wellknown, that of the switchboard isn’t. What started as a tool for communication became a catalyst for Women’s Rights.

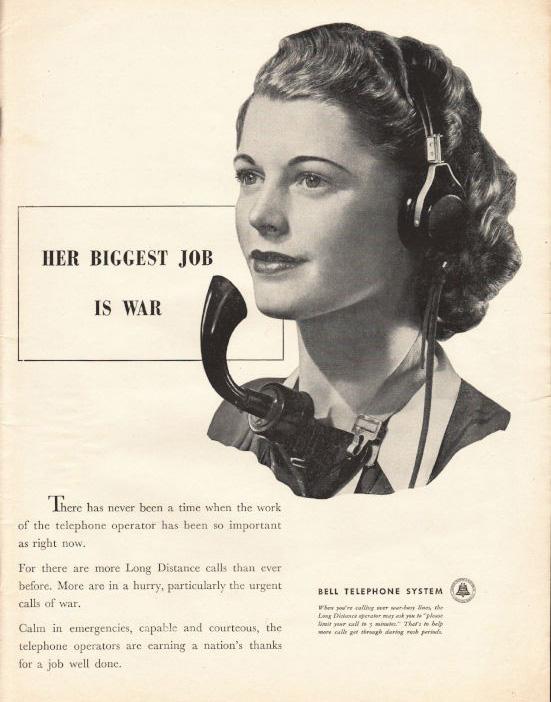

The first telephone operators were required to memorize hundreds of numbers and work with board with strict accuracy. When World War I came along, 223 women worked behind the scenes connecting military personnel across the globe, prioritizing those calls over civilians and ensuring communication was never interrupted.

With the invention of the automated phone system, the need for a switchboard became less necessary and more reserved for large businesses. Today, the switcboard is still around, helping to directly connect callers with someone who can answer their questions. It’s still an important job in a society that thrives on human connection.

Sara Edwards, Editor

As Allied troops gained ground in Europe, members of the Women’s Army Corps [WAC] were there to serve. Bringing vital communication skills, they jumped into seats at switchboards still warm from the enemy operators who had just vacated their posts. In July 1945, the WAC telephone operators were selected to manage the “Victory switchboard” at the Potsdam Conference.

During the Potsdam conference, a company of WAC telephone operators were flown from their Battalion Headquarters in Paris to staff the switchboards. They operated the large “Victory Switchboard” at the conference and also a smaller switchboard at President Truman’s residence, the “Little White House,” enabling fast and secure communication between President Truman and staff back in Washington, D.C.

Following the conference, Truman thanked the servicewomen and congratulated them, stating that “they contributed materially to the success of the Berlin conference.” Truman wrote in his letter of commendation, “The installation of radio-teletype facilities there allowed me to keep in almost instantaneous touch with my offices in Washington and provided a steady flow of news and information which greatly assisted me during the Conference. I also enjoyed excellent telephone service

at the Little White House and was pleased and surprised to learn that through the efforts of the Signal Corps, I could make the first telephone call from Berlin to the United States since December, 1941.

Instantaneous communication was, unlike today, most exceptional. Communication of all kinds was a critical component of good intelligence and having a sufficient number of trained, skilled operators at telephone switchboards was essential. The WACs were selected for the Potsdam assignment because of their skills, and because of the success of operators at the Quebec and Cairo Conferences two years prior. Generally, WACs were selected for many of these communications tasks with the Signal Service because they already had years of experience in the very tasks they were called on to perform—often clerical, administrative, and communications duties. Such was the case with working the switchboards; women were selected as operators because of their training.

Women had worked as telephone operators since the telephone’s invention. They were viewed as more courteous and also were cheaper to employ. Some women entered the WAC under the WIRES program (Women in Radio and Electrical Service); these recruits typically continued to perform the specialties they had in civilian life. Their familiarity with various systems and the experience connecting calls through circuits allowed for greater efficiency than working with new trainees. When plans for women to enter service were first discussed, General

George Marshall actively supported the use of women in the communications realm. Marshall and others considered women perhaps better suited for these tasks which were repetitious and required patience and manual dexterity.

The first WACs deployed in the European theater arrived in England in July 1943. They were put to work immediately in support roles for the Eighth Air Force. There they served in clerical, administrative roles, but also as cryptographers, photo interpreters and motor pool drivers. The WACs who worked the telephone systems were in demand, a demand that remained high until the very end.

Exactly one year after the first group of WACs landed in England, WACS arrived in France. On July 14, 1944, D+38, the WACs arrived and assumed control over switchboards that had only

recently been controlled by the enemy. They lived and worked in tents, cellars, and switchboard trailers. On August 16, 1944, WAC Staff Director, Lt. Col. Anna Wilson wrote a letter home to WAC T/5 Teresa Gordon’s parents in New Orleans, after she was one of the first WACs to arrive in France. “She is tan from the sun and glowing with health from outdoor living.”

A week after the liberation of Paris, the WAC operators arrived and set to work on the city’s switchboards. The city would serve as the Headquarters of the WAC Battalion, designated with the unusual nomenclature of the %3341st Signal Service Battalion. When the battalion was organized by the Signal Corps, it lacked the combat equipment needed according to standard organization tables, so the percent mark was used by the Signal Corps to set this unit apart, to indicate on paper that the unit was composed solely of female noncombatants. The Battalion consisted of officers, switchboard teams, message center teams, and teletype teams. The Battalion reached peak strength with 28 officers and 738 enlisted women. The Headquarters at Paris was said to have been the largest message center in the world outside of the capital.

A WAC bulletin described how they functioned as Allied troops advanced: “Telephone operators donned earphones as fast as mobile switchboards were set up, worked long shifts day after day. In a chateau wine cellar in Area I, operators worked the board while rainwaters swirled around their feet.” Then later in Germany, “Scores of operators, members of the %3341st Signal Service Battalion, now under the command of Maj. Jane A. Stretch, Newtown, PA., went on duty at telephone switchboards where German voices had been heard just a shorttime previously.”

The work was not always difficult, but the importance of the task and the secrecy of the information the women overheard was demanding. One WAC

inspector reported: “Severe nervous strain was imposed by the necessity for constant attention...no thought was required for much of it, yet the worker did not dare let the work become automatic, as one slip wrecked everything, and the fear of costing men’s lives was always with them.”

The WACs who worked the switchboards in World War II had an esteemed lineage. The Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit, informally known as the disparaging “Hello Girls,” were sworn into the US Army Signal Corps and served with distinction in the American Expeditionary Forces. When the call was put out for women for the outfit, more than 7,000 volunteered for the 450 available spots. Qualifications included a fluency in French and English. Eventually, 223 “bilingual wire experts” were sent overseas where they fielded over 26 million calls while in American uniform. Despite their significant contributions, they were not recognized for their service. Ultimately these women were viewed as civilian contractors after World War I and were not given veterans status or benefits until 1978, the 60th anniversary of the end of World War I.

The Women’s Army Corps operators of World War II faced similar odds. One WAC recalled being instructed to lie and say she had served as a nurse, because of the stigma that WACs did not play a serious role, but were only there for the pleasure of the men. Many families of the women who served also held mixed emotions about their daughters serving. WAC Lt. Col. Anna Wilson wrote T/5 Teresa Gordon’s parents, “She and hundreds like her have already earned their right to a distinguished place in the great history of the Army of the United States. In the European theater, one fourth of all WACs in service, or 1,700 women, were attached to the Signal Corps, including the 30 women who “contributed materially” to the success of the Potsdam Conference.

The Headquarters at Paris was said to have been the largest message center in the world outside of Washington, D.C.

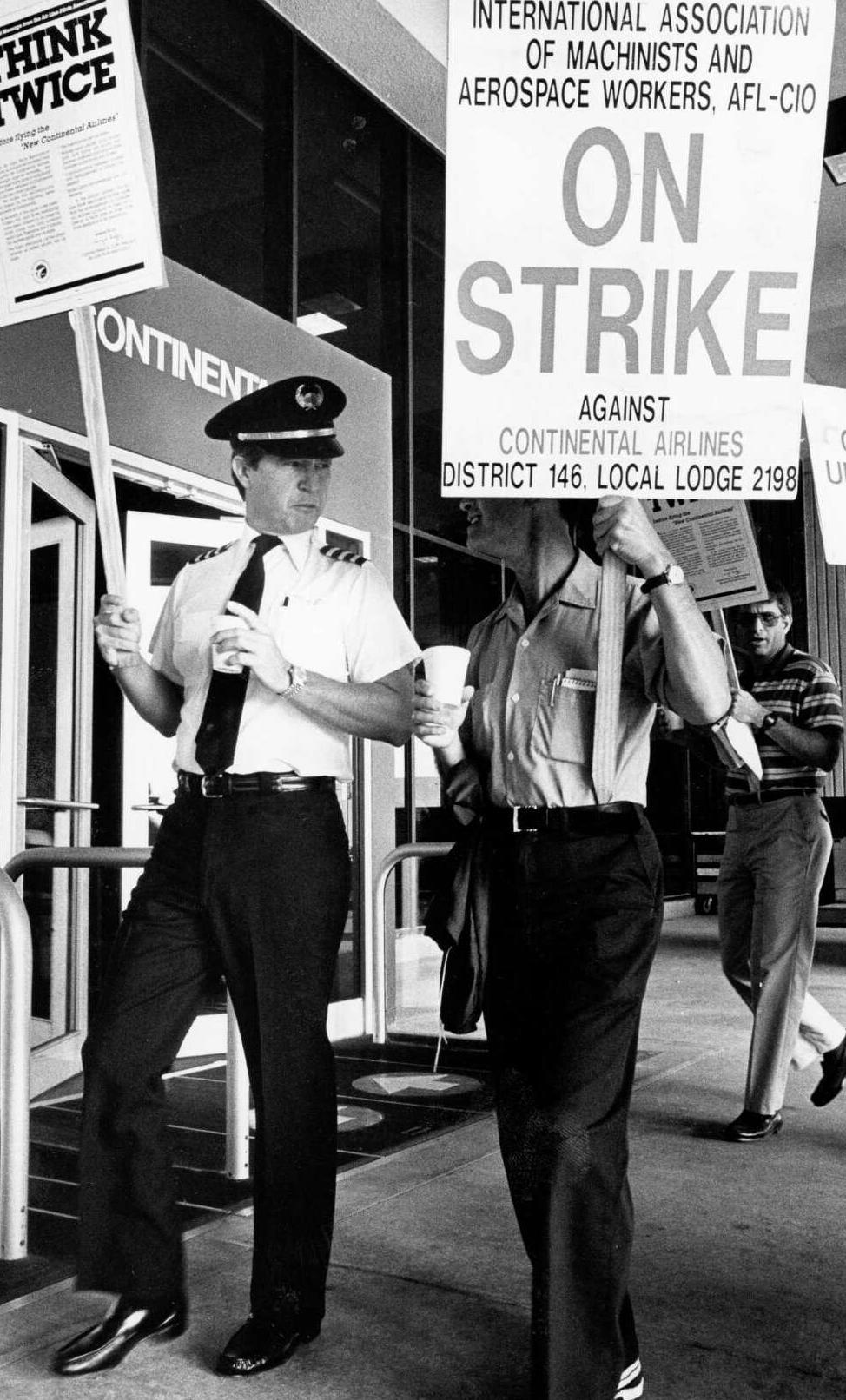

As their numbers grew, women operators became a powerful force—for workers’ rights and even serving overseas in WWI.

In the earliest days of the telephone, people couldn’t dial one another directly. They needed an intermediary—a telephone operator—to manually relay their call on a central switchboard connected to subscribers’ wires. It was a crucial new service that helped a revolutionary new technology spread widely to the masses.

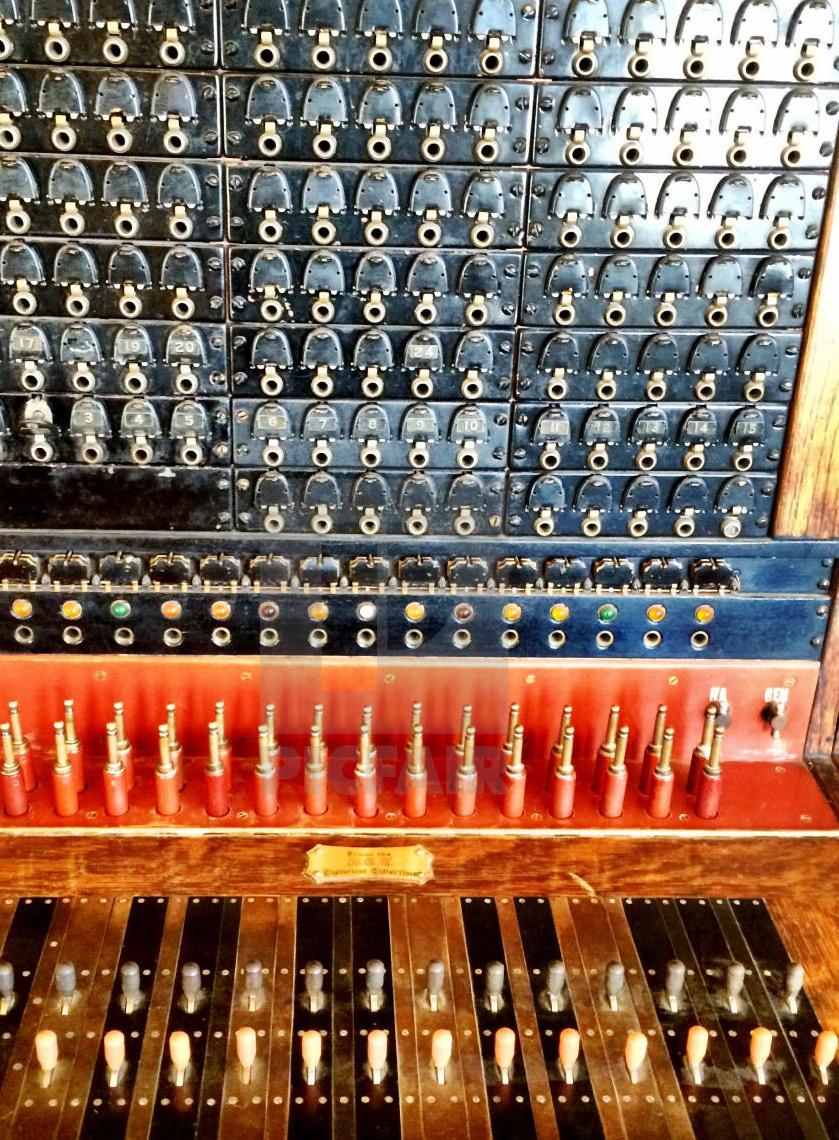

The idea originated in April 1877, when 40-year-old George W. Coy attended a lecture by Alexander Graham Bell. In it, the famous inventor demonstrated how he could converse with two colleagues—one 27 miles away, the other 38 miles—using a device he’d patented just the year before: the telephone. Coy, a Civil War veteran who worked in the telegraph business, soon made a deal with Bell to set up the first telephone exchange in the United States, a central switchboard that allowed anyone with a telephone to call or be called by anyone else who had one.

Coy’s telephone exchange, in New Haven, Connecticut, opened in 1878, with all of 21 clients, including the local police, post office and a drug store. Today, Coy is often cited as the world’s first telephone operator. But while Coy devised the switchboard for the exchange (improvising some parts using wire from women’s bustles!), he hired two boys to operate it. Louis Frost, the 17-year-old son of one of Coy’s business partners, was most likely the first operator.

That Coy would employ boys to do a job later associated mostly with girls and young women was only natural. Boys often worked at telegraph offices, while female telegraph operators were a rarity. That would continue into the early days of the telephone. But by the beginning of the 20th century, women began dominating the field. And as their numbers grew they became a powerful force—fighting for the right to join unions, striking for higher wages, even serving overseas in WWI.

Boy Operators Didn’t Last

-Paul Thompson/Getty Images,It turned out there was a problem with male switchboard operators: The boys, often barely in their teens, couldn’t seem to behave themselves. They had a tendency to roughhouse. And “when some other diversion held their attention,

they would leave a call unanswered for any length of time, and then return the impatient subscriber’s profanity with a few original oaths,” wrote Marion May Dilts in her 1941 book, The Telephone in a Changing World.

Hoping to find operators who’d be more attentive to their duties and not cuss out the customers, local phone companies began to recruit girls and young women. Often that meant going house to house, trying to persuade parents that telephone operator was a respectable job for their daughters.

As the number of telephones in the U.S. multiplied, so did the demand for operators. In 1910, there were 88,000 female telephone operators in the United States. By 1920, there were 178,000, and by 1930, 235,000.

What Did Telephone Operators Do, Exactly?

In the telephone’s earliest days, one phone could be connected to another by wire, allowing their two owners to speak. It was clear that the telephone would be much more useful if any given phone could communicate with numerous phones. Switchboards made that possible.

Each of the phones in a particular locale would be connected by wire to a central exchange. The owner of a telephone would call the exchange, and a switchboard operator would answer. The caller would give the operator the name of the person he or she wanted to speak with, and the operator would plug a patch cord into that person’s socket on the switchboard, connecting the two. Longdistance calls would require the local exchange to patch the call through to more distant exchanges, again through a series of cables. Later, as the exchanges added more and more customers, phones were assigned numbers, and callers could request to be connected that way.

Some early telephone operators worked at small, rural exchanges, their switchboards located in the local railroad station or the back of a general store. In cities, massive switchboards could have long rows of operators packed.

Operators were subject to strict Rule

At the busier boards, work could be frantic. Some operators took to wearing roller skates to get around. Otherwise,

In 1910, there were 88,000 female telephone operators in the United States. By 1920, there were 178,000, and by 1930, 235,000.

the dress code tended to be strict—long black dresses and no jewelry, for example.

Operators were subject to numerous other rules, and spies sometimes monitored their calls on a device called a listening board. In 1899, when a 25-year-old San Francisco operator named Anna Byrne killed herself, the coroner held the phone company responsible: “I firmly believe that the espionage to which telephone girls are constantly subjected drives them to suicidal desperation. They are overworked; and no mercy is shown them when a slight offense is committed by a trivial infraction.”

Many operators agreed. “The wonder is that more telephone girls don’t kill themselves,” a veteran operator told the San Francisco Examiner. “We are not allowed to speak even in a whisper to each other the nine hours we are on duty, much less smile, and to laugh out loud is the height of recklessness.” She said she’d once been forced to work 10 extra hours, without pay, for one brief giggle. Companies often tried to control their operators’ personal lives, “The unwritten rule was that she could not marry and would lose her job if she did,” noted Ellen Stern and Emily Gwathmey in their 1994 history, Once Upon a Telephone.

The Operators Rebel

The pace of the work and the repressive rules that operators often had to put up with eventually led to dissension in the ranks. Phone companies discovered that their supposedly docile female workforces could only be pushed so far.

In April 1919, for example, some 8,000 operators walked off the job at the New England Telephone Company, all but shutting down phone service in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont. Five days later, the company met their demands for higher wages and the right to bargain.

The New England strikers may have been inspired by the more than 200 female telephone operators (out of 7,000 who applied) who’d served heroically in First World War. The Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit, informally known as the “Hello Girls,” had started overseas in March 1918. Their mission was to facilitate communications between

American, British and French troops on the Western front, serving not only as operators but often as translators.

The Hello Girls, along with women serving as nurses, ambulance drivers and in other jobs crucial to the war effort, are credited with helping President Woodrow Wilson drop his objection to women’s suffrage and endorse it in a 1918 speech to Congress. “We have made partners of the women in this war…” Wilson said. “Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?”

The End of The line?

With the coming of the 1930s, technology that allowed telephone users simply to dial another phone without the aid of an operator had become widespread. Phone companies took advantage of the moment to slash their workforces, and thousands of operators lost their jobs. By 1940, there were fewer than 200,000 in all.

In 2021, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a total of just 5,000 workers it classifies as “telephone operators” plus another 69,900 categorized as “switchboard operators including answering service.” And it expects more than 20 percent of those jobs to disappear by the end of the decade.

The Hello Girls, along with other women serving in jobs crucial to the war effort, were credited with helping President Wilson endorse Women’s Suffrage in a 1918 speech to Congress.

It soon became a female-dominated field. Julia O’Connor led successful strikes against New England Telephone Co. in 1919 and 1923 to get better pay and working conditions. Darrell Davidson/HC staffWhen the Bell System first offered telephone service to subscribers, it hired teenage boys for operators. Now, teenage boys have many virtues, but patience, focus, and the ability to take criticism are not chief among them. When the number of irate customers rose sharply, the company replaced them with women

Women, the company reasoned, were tactful, helpful, dedicated, attentive to details—and they could work harder than most men thought possible. They could deftly handle the callers who became furious when told the number they were calling was busy.

In those days, the job of a telephone operator—also called a “Hello Girl” or “Central”— was far from easy. First, she had to take all responsibility for electric shocks she received from her “operating board.” She also had to memorize the position of 300 phone numbers on the board directly in front of her.

She was expected to use only the language approved by the company. Numbers could be read only one way.

(The number 2000 could only be spoken as “two oh, double-oh.” 4001 was “four, double-oh, one.”) The company also directed them to give the time in “railroad style”: not “twelve minutes to nine” but “eight forty-eight.” The rest of her speech was limited to a handful of approved expressions:

“Number?”

“They don’t answer.”

“Line busy.”

“Line out of order.”

“I have no such number; please refer to your directory.”

“Telephone has been taken out.”

“I will give you Information.”

“I will give you Chief Operator.”

Lastly, an operator had to be fast. Central takes care of six or seven customers a minute. During the rush hour she supplies 360 connections in 60 minutes;

under stress of intense public excitement she has a record of answering 15 calls every minute.

There was one small compensation to all the drawbacks of being a “Hello Girl,” according to Dickson: In her spare time, she dearly loves to listen to telephone chatter—by way of novelty and recreation.

Officially, the Bell Systems didn’t allow operators to listentin to conversations, Dickson reported. (In France, he added, privacy was enforced by the Government.) Operators were prohibited to marry anyone on a long list of forbidden bridegrooms: police employees, detectives, government officials, foreigners, etc. so they wouldn’t be tempted to divulge any secrets they may have overheard.

The anonymous author of “The Diary of a Telephone Girl: The Work of a Human Spider in a Web of Talking Wires” readily admitted to eavesdropping.

There are sometimes long enough intervals … for me to be able to read or write letters. They put on bell attachment that rings for every call, so I can’t fail to answer.

Of course I had plenty of time for listening, and it was so exciting sometimes that I hated to stop long enough to answer another call.

The other night I switched a friend of mine on to the line, opened his listening key and others in turn, so that for an hour he could overhear all sorts of private conversations, one after the other.

It’s so queer to press down the row of “listening keys” one after another and get bits of the different conversations! Different voices, different dialects, different emotions, tempers, subjects! All sliced off like Neapolitan ice cream—little bits of pulsing human lives. The girls do awfully mean

things when they’re exasperated by angry subscribers. You can, for instance, switch three or four couples together—a pair of lovers, maybe, two business men and one woman gossiping to another—and then sit and hear them rage at each other.

It was interesting, too, to notice how the character of the talk changed as the hour grew late. The conversations seemed to grow more familiar and confidential and affectionate toward eleven o’clock.

There are several distinct types that I can recognize immediately and I almost know what they’re going to say.

First, at 7 o’clock, there are scattered calls, usually important, for doctors, perhaps; and you have to ring and ring, because the subscribers hate so to get up and answer the ‘phone.

At 8 o’clock, the nice, early-morning women come on to market with patient,

affable butchers. They always want a tender joint and fresh vegetables. “Yes, ma’am!” say the butchers.

At 9, the business man in a hurry, in a loud, violent tone, impatient and cross, bullying the operator, and then, when he gets his number, lowering his voice to an amiable growl.

At 10, interminable conversation between women over the “flat-rate” ‘phones with infinite details as to clothes. There’s no five-minute limit to talks with this company and you can’t cut them off. I’ve known them to keep it up for three-quarters of an hour. [Imagine: talking on the phone for 45 minutes!—ed.]

At 11 to half-past there’s a lull, punctuated, perhaps, by nippy ladies calling up employment agencies [looking to replace a servant], or stupid servant girls replying. At 11:30 till 12:30 there’s a wild rush, everybody trying to catch everybody else for lunch.

From then till 3 or so there are characteristic calls of all sorts: peevish, hurried females who use the nickel ‘phones in the downtown drug stores, and who have just got to have their numbers; silly schoolgirls mischievously calling up men they don’t know; sporting men [placing bets] in an unintelligible racing jargon, and so on.

From 3 to 4 it slows down again. Then there’s likely to be a flurry of women trying to call up stores before they close, or in time to catch the last deliveries.

At 5, wives begin to call up to know if husbands are coming home, and if not, why not? Apologetic replies from offices as business men attempt to explain. Or, if he’s coming, “Be sure to bring home a steak or a lobster.” He (in disgust): “Why couldn’t you have ordered them this morning?”

From 6 till 7 everybody seems to be too busy to call up, except the younger people, girls and youths, who joke and

[plan to meet later]. This is a good hour, too, for the obsequious underling, the club hallboy or the clerk of a garage, who has taken orders and been respectful all day, to talk down to the telephone operator. Now, along toward 8, comes the nervous maiden, calling up her men, too uncertain of their reception to bully Central as she usually does.

From 9 on not many calls. After 10:30 come the calls [for taxis and chauffeurs] and the hotel private exchanges begin to get busy. Then, at 11 and on through till 2, the reporters with strange tales.

I hate the reporters. They always have the most thrillingly interesting conversations, but if I listen on the line they always know it and get mad. “ Get off the line, Central,” they say, “or I’ll stop talking!” No matter how softly I press back my listening key, they seem to know I’m listening, and then they talk so horridly that I simply have to shut the key.

With automation replacing most phone operators, there are far fewer people to eavesdrop on your conversation. Besides, the whole idea of private phone conversations seem quaint in an age of cell phones. You don’t need to become an eavesdropping operator when callers walk through airports and stores handing out free samples of their private lives.