Resisting Decolonisation, Are Museums Resisting Institutional Change?

Samuel Hearne Birmingham City University, United Kingdom School of Architecturesamuel.hearne@mail.bcu.ac.uk

Abstract:

This perosnal illustrated essay attempts to examine if and how museums resist institutional change. My main body explores how the stolen Benin Bronzes artefacts of 1897 are catalysis in western museums and galleries for change and decolonisation following international protests for racial equality and social justice. With particular reference to the cultural institutions, the British Museum and the National Museums Liverpool World Museum, I’m concentrating on how museums perceive primitive art, exhibition composition, and political motives behind museums.

Key Words:

museum, decolonisation, colonial, inclusivity, restitution, Benin Bronzes

Methodology:

This study will analyse the extent of resistance against institutional change within museums and galleries.

Multiple anthropologists and historians have studied the culture of museums and their artefacts to offer their thoughts and opportunities for possibly decolonising the civic realm of museum spaces, such as Dan Hicks and Svetlana Alpers. My research will build upon their strategies and techniques to understand why museums resist change and know what methods can encourage inclusivity, accessibility, restitution and decolonialism.

Visiting museums and documenting my experiences through photo analysis is one method conducted during this research process. Gaining perspectives from people who feel represented through artefacts from their own countries is another.

List of Figures

Figure 1: Edward Colston’s statue moving towards the river Avon by protesters in Bristol.

Figure 2: Nelson the Lion on display in glass cabinet at the Clifton Park Museum, Rotherham.

Figure 3: The Past Is Now exhibition, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery.

Figure 4: Artificial intelligence, visual analogy of Kassim’s ephialtes.

Figure 5: Benin plaques, British Museum.

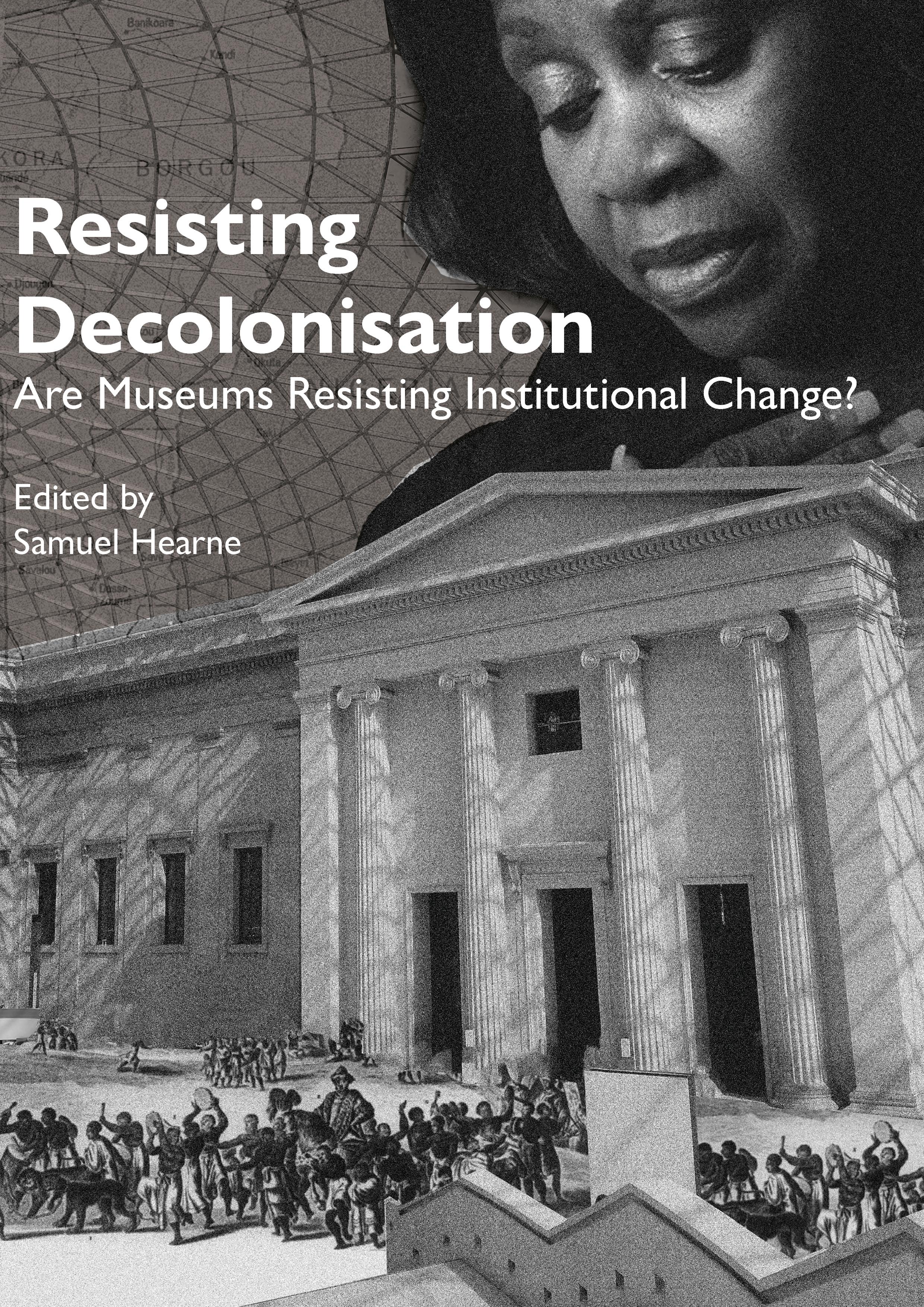

Figure 6: British soldiers with objects looted from the Benin City royal palace, 1897.

Figure 7: Professor Abba Tijani, handling Benin Bronzes at the Horniman Museum.

Figure 8: Martin E. West’s representation of the social structure from the perspective of coloured people.

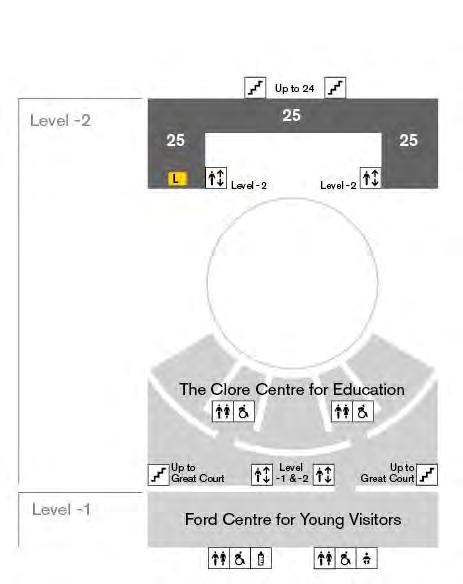

Figure 9: British Museum lower floor museum map.

Figure 10: View of Benin plaques from entering the exhibit.

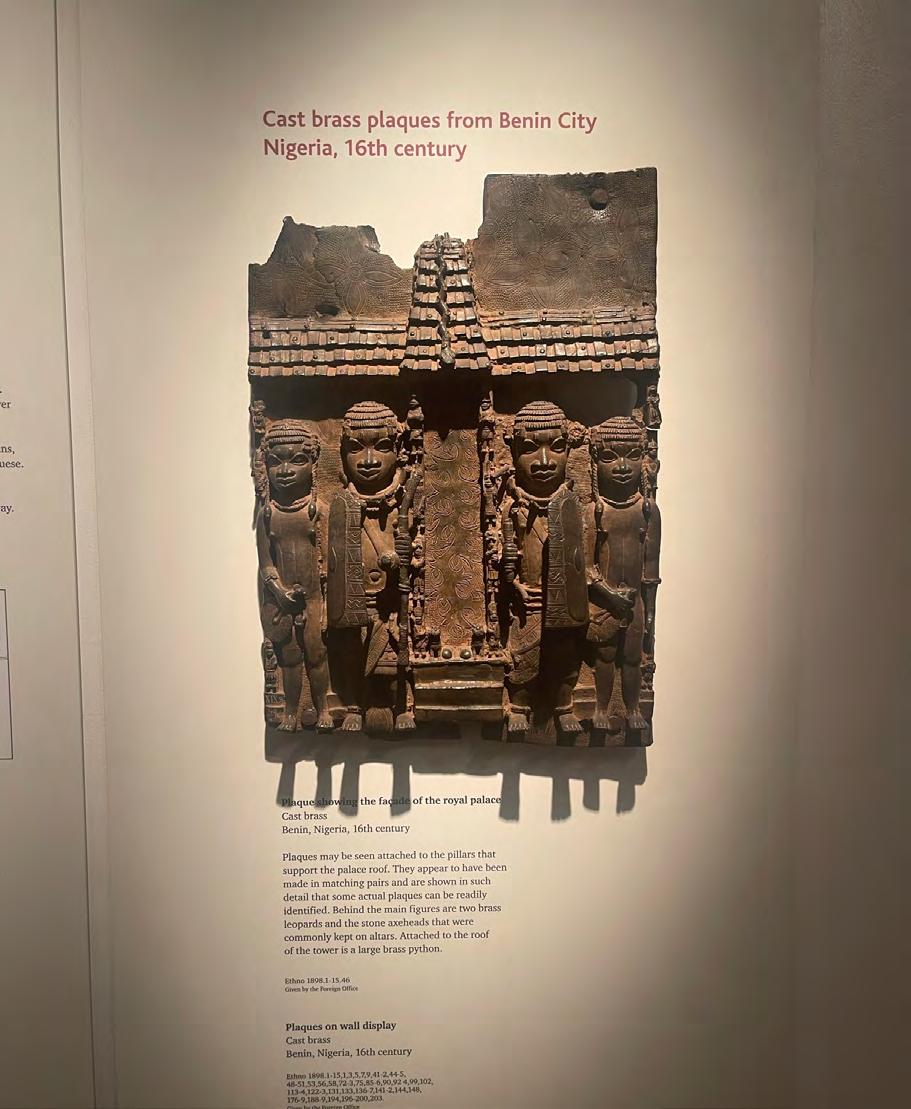

Figure 11: Cast Bronze Benin plaque.

Figure 12: Vice Media’s, The Unfiltered History Tour.

Figure 13: Benin Bronzes exhibit, British Museum.

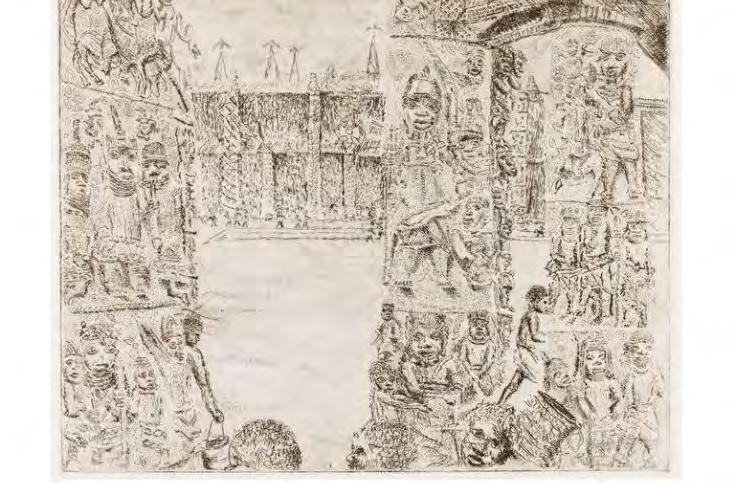

Figure 14: IV. The Oba’s Palace, Tony Phillips, 1984.

Figure 15: Hoa Hakananai’a, British Museum.

Figure 16: Benin Bronzes being looted, February 1897.

Figure 17: Iraq’s National Museum looting, 2003.

Figure 18: Rumaila oil field, Iraq.

Figure 19: BP Lecture Theatre.

Figure 20: Climate activists demonstrate against BP outside the British Museum, 2020.

Figure 21: Shepperton Womans fragmented skeleton remains.

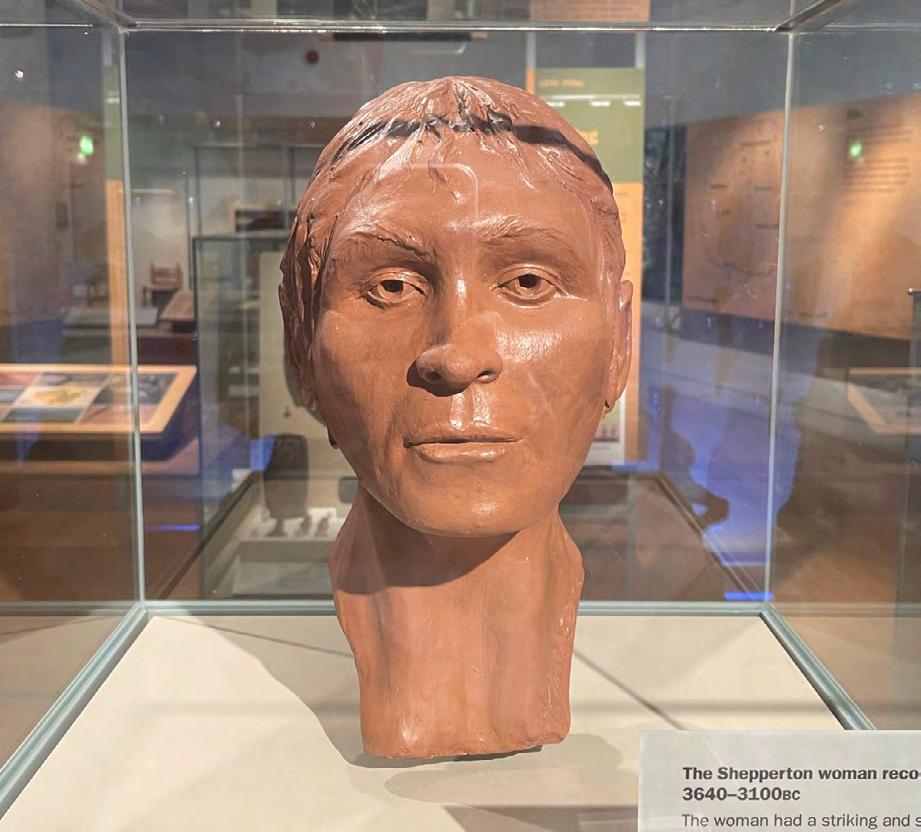

Figure 22: Reconstructed clay head of a Shepperton lady.

Figure 23: Gifts to the Water.

Figure 24: Benin and Liverpool workshop.

Figure 25: Previous Benin and Liverpool Exhibit.

Figure 26: Benin ancestral altars.

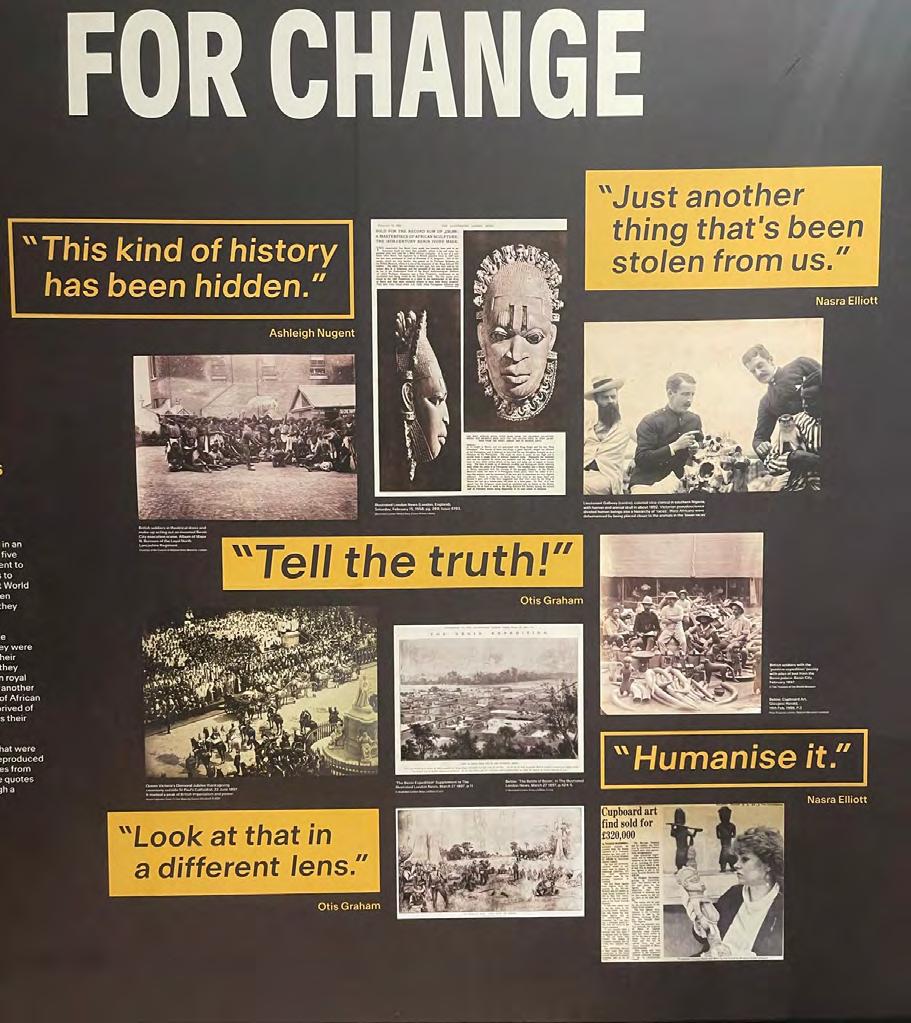

Figure 27: Working Together for Change, New Benin and Liverpool Exhibit.

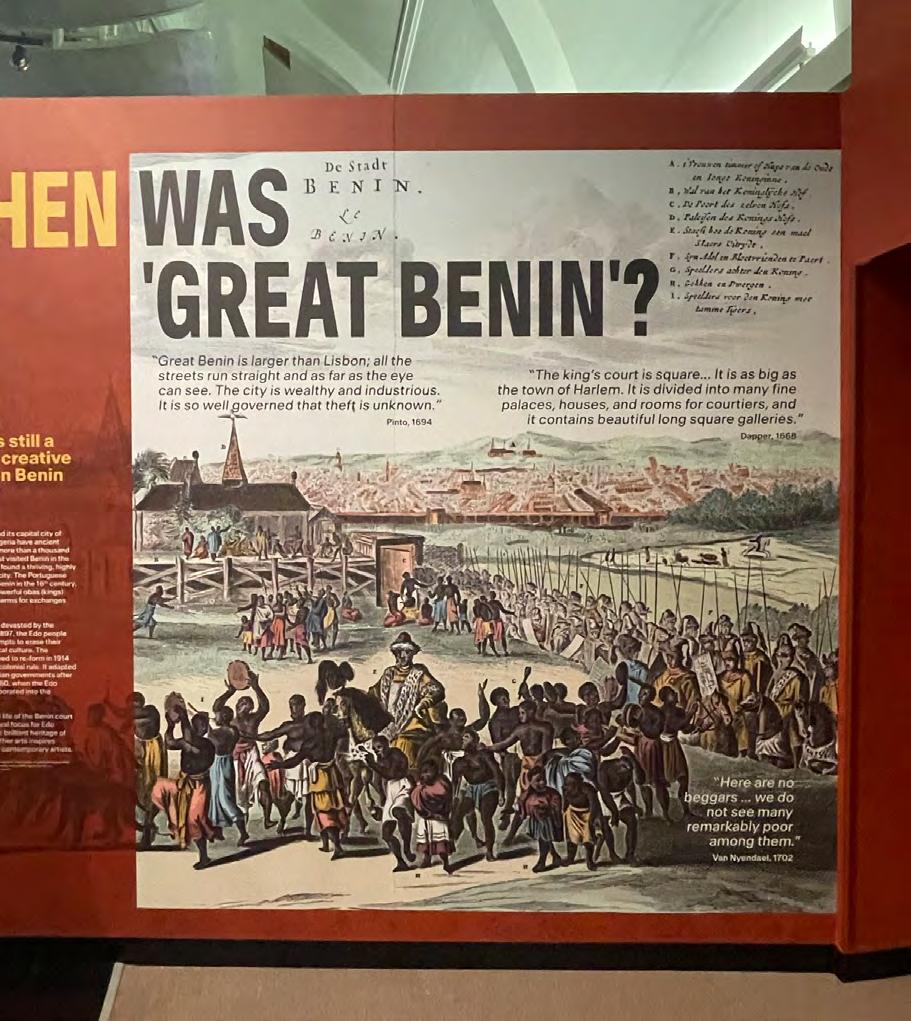

Figure 28: When was ‘Great Benin’? New Benin and Liverpool Exhibit.

Figure 29: Why Display Royal Artworks Stolen from Benin in Liverpool? New Benin Exhibit.

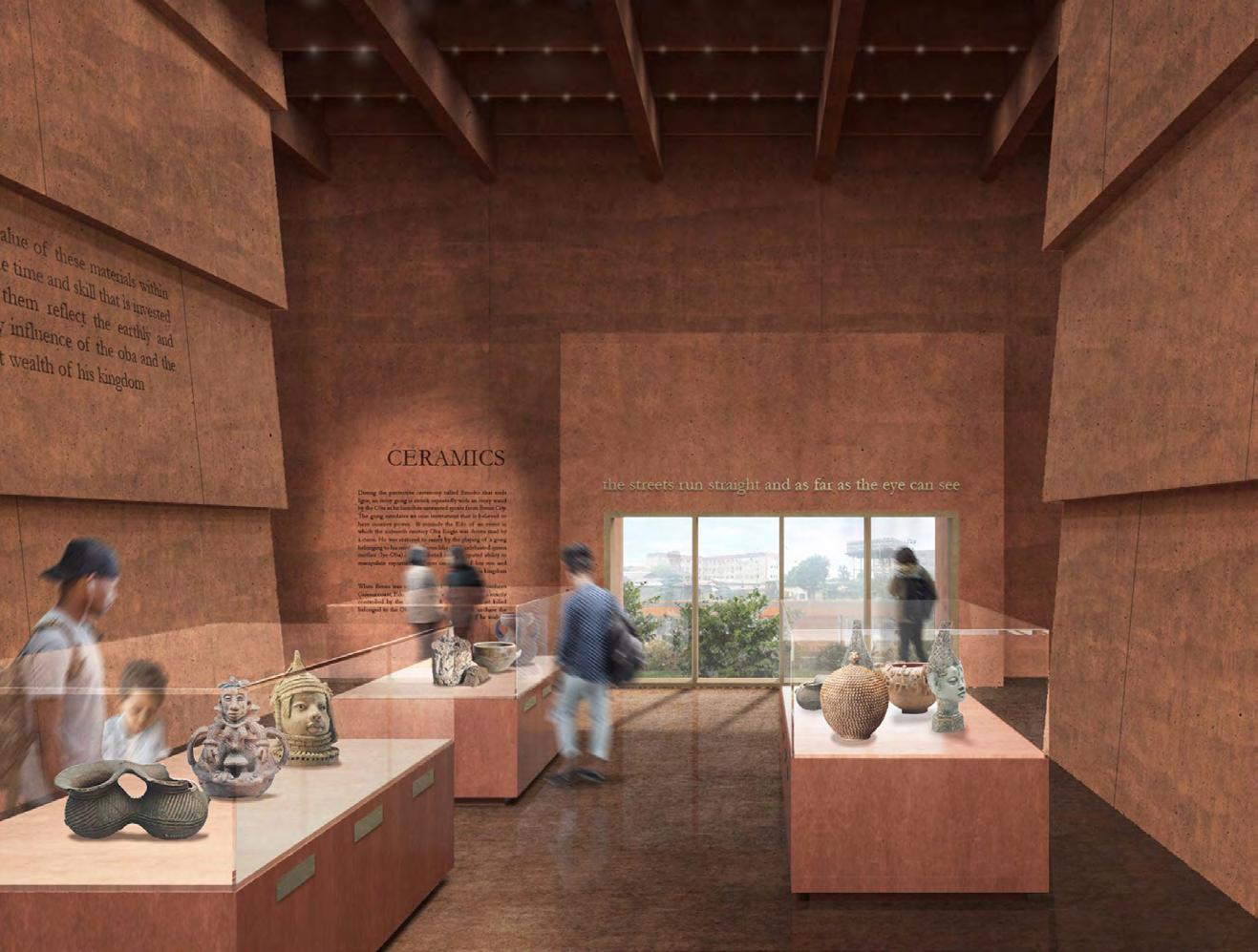

Figure 30: Adjaye Associates Edo Museum of West African Art, Benin City.

Introduction

Objects enter museum collections in various ways, but the accumulation of artefacts by colonial activity and conflict often stirs great controversy within communities, arguing that such items should return to their indigenous state. To justify their wrongdoing, museums provide themselves as neutral containers for the world's history but instead, they actively play a role in falsely narrating contested artefacts. They're tools that re-tell these colonial stories and recreate the violence.

Attempts to return items come with little success, a recent example being the Benin Bronzes and their return to modern-day Nigeria. Removing colonial exposition within our museums has been a polemical talking point for centuries as people feel the need to progress from times when our museums were for institutional racism, race science and the display of white supremacy. The issue has been going in and out of the spotlight. However, some believe we have reached a new cultural epoch.

African American George Floyd's death in May 2020 triggered international protests for racial equality and social justice. It saw statues being targeted that honoured controversial figures from colonial history, drawing attention to museums and their holdings. Although museums have voiced their support for the Black Lives Matter movement, many institutions with ties to colonial past still wrongly celebrate contested cultural objects and resist their restitution. This social justice movement has placed the decolonisation of museums back into the limelight, narrated through museums' possession of contested artefacts and, through this lens, sparks the question of whether museums resist institutional change.

Museum and Decolonial Theory

Nelson the lion, is one of my earliest, most distinct memories of visiting museums. The bronze statues of the lions standing at the base of Nelson’s column in Trafalgar Square are thought to have been inspired by Nelson, a South African Cape lion, a now-extinct species. In a glass cabinet, Nelson is on display in Rotherham’s Clifton Park Museum. I can observe the lion in this way since it is dead, and he has been positioned so that one may move around the front and side of the case. Because the museum transforms the lion it led me to perceive the lion, in this way as an object of visual curiosity, I perceive him as an artefact, a work of art.

As Svetlana Alpers describes in her chapter, ‘The Museum as a Way of Seeing’ in the book Exhibiting Cultures, European museums for a long time have promoted the appreciation of artefacts as works of visual art. Although much has been said about the ideology of power involved in both the gathering of artefacts and the systematic technique of arranging them, when exhibiting primitive art, the ‘museum effect’ as defined by Alpers ‘isolate[s] something from its world, to offer it up for attentive looking and thus transform it into art like are own.’ People, communities, and nations feel the desire to feel represented effectively in museums and feel agitated as their representation is squandered through the isolation of their artwork.

The western world shows little concern for the portrayal of the eastern world in museums throughout history. Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism expands on this idea by attempting to explain why we have preconceived notions about the eastern world via a lens that distorts reality. Although this theory focuses on the neglect of the eastern world, Said’s investigation into orientalism has permeated populations in Africa that also believe their legacies are underrepresented.

The scholarly rejection of Africa’s past persists now, but it is not often articulated as shamefully as in the opening lines of the well-known book The Rise of Christian Europe, written by the Oxford historian and Tory racist Hugh Trevor-Roper.

‘Perhaps in the future, there will be some African history to teach. But at present there is none, or very little: there is only the history of the Europeans in Africa.’

The ideology of power involved in gathering artefacts from these third-world African and eastern countries translates to colonial wars narrated over the history of western propaganda. These small wars saw the looting of tens of thousands of objects and the humiliating, barbaric dismantlement of countries histories and cultures. These looted objects are not frozen. They are not at a period that we look at in the past. Every day they are representative and recreate unfinished events. Museums provide themselves as neutral containers for the world’s history but are tools that re-tell these stories and recreate the violence every day.

The current language of “decolonising” museums is an effort to erase the debts left over from colonialism. In relation to The Past Is Now exhibition at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Sumaya Kassim has noted that:

“Decolonising is deeper than just being represented. When projects and institutions proclaim a commitment to ‘diversity’, ‘inclusion’ or ‘decoloniality’ we need to attend to these claims with a critical eye. Decoloniality is a complex set of ideas – it requires complex processes, space, money, and time, otherwise it runs the risk of becoming another buzzword, like ‘diversity’. As interest in decolonial thought grows, we must beware of museums and other institutions propensity to collect and exhibit because there is a danger (some may argue an inevitability) that the museum will exhibit decoloniality in much the same way they display/ed black and brown bodies as part of Empire’s ‘collection’. I do not want to see decolonisation become part of Britain’s national narrative as a pretty curio with no substance – or, worse, for decoloniality to be claimed as yet another great British accomplishment: the railways, two world wars, one world cup, and decolonisation.”

Using artificial intelligence, I created a visual analogy of Kassim’s ephialtes, claiming decolonisation as another British accomplishment. It is a sickening image. The thought of freeing an institution from the cultural or social effects of colonial events that saw thousands of deaths and the looting of artefacts represented through a trophy or plaque as a monumental achievement is blatantly disgusting.

Benin Bronzes

An intense debate of decolonialism, restitution, and cultural representation circles the highly contested objects of the Benin Bronzes. The 5,246 digitally recorded Benin Bronzes are a series of stolen metal artefacts that ornate the monumental and religious buildings of the Kingdom of Benin. The unforgivable actions of the Benin Expedition of 1897 saw the Benin Bronzes placed worldwide. The British Museum holds 944 of them, with an estimate of at most only 15% of the objects being on public display.

Alongside uncounted deaths of the Benin occupation, monuments and the Benin Royal Palace were burned and destroyed with British forces looting anything of value and withdrawing them as official 'spoils of war'.

The expedition was baneful, with Professor John Boardman from the University of Oxford saying, 'with the Benin bronzes, the rape proved to be a rescue.'

On the trial day of the Oba, which took place in the Benin Kingdom marketplace, Sir Henry Lionel Galway, the deputy commissioner and vice-consul in the Niger Coast Protectorate provided a clear account for the justification for actively erasing the Benin Kingdom.

The Benin people on that execution morning had much to think about. Their King removed, their fetish Chiefs executed, their Ju-ju broken, and their fetish places destroyed. Of their crucifixion trees not a trace left; and all around evident signs of the white man’s rule –equity, justice, peace and security.

Upon reading the quotes of Professor John Boardman and Sir Henry Lionel Galway in Dan Hicks' book, The Brutish Museums, I had to stop reading in disbelief. How I thought in any sober man's thought, could you ever impair a kingdom, regard it as a fetish society, alienate a culture and attempt to erase it from civilisation? The sickening mention of a white man's rule based on equity, justice, peace and security is an oxymoronic gesture to the events in Benin.

It comes as no surprise as to why the Benin Bronzes circulate around the debate of decolonialism, restitution, and cultural representation. Which sober British institutions would even consider proudly displaying such precious and monumental items? Housing the Benin Bronzes in British Museums enforces pain and suffering on those who feel represented by them.

Within today's society following the protests for racial equality and social justice, restitution of the objects should be obligatory. In November 2022, the Horniman Museum, London, did just that by returning 72 items, including Benin Bronzes, back to Nigerian ownership, making it the first Museum in the UK to take such action.

On handover, professor Abba Tijani, director general of Nigeria's National Commission for Museums and Monuments said: "Hanging on to looted objects is no longer tenable." He says, "I think we're seeing a tipping point around not just restitution and repatriation, but museums acknowledging their colonial history".

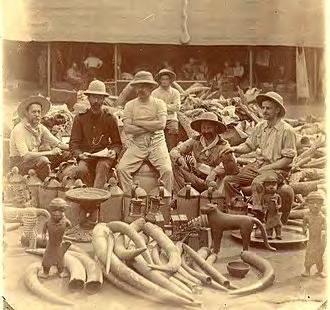

Benin Bronzes in the British Museum

With a preexisting knowledge of what the Benin Bronzes were and their barbaric back story, I went to see the bronzes first-hand at the British Museum, which holds the largest collection of them in the world. When I first arrived at the British Museum, I immediately went to The Sainsbury African Galleries. With the gallery space two floors below ground level, does the British Museum, before seeing the items on display, disregard African culture and demonstrate a western viewpoint of social hierarchy? When against Martin E. West’s representation of the social structure from people of colours perspective, one could say yes.

I accidentally entered the gallery through the unorthodox approach of a lift and had an instant confrontation with the arrangement of plaques. They sent chills down my spine. Initially, I fell for Alpers 'museum effect'. I saw the objects as visual art, forgetting momentarily about their colonial ties. They were mesmerising.

When I overcame the overwhelmedness and staggering beauty of the plaques, I began to analyse the exhibition's narrative. The British Museum provided little to no visual condolence of the tragic event of the Benin Expedition, merely saying, "Benin City suffered a violent and devasting occupation with many casualties," in small print in the far corner of the exhibit.

Disappointed by the portrayal of the exhibition, I used Vice Media's, The Unfiltered History Tour to obtain a better-represented narrative of the exhibit. The Unfiltered History Tour is an augmented reality Instagram filter that allows the viewer to hear the stories of the artefacts as told by people from their homelands. I instantly gained a deeper understanding and sense of the artefact.

Looking at the overall display of the Benin Bronzes at the British Museum, I believe the museum incorrectly represents the Benin Bronzes. All the heads, masks, weapons, and other objects that are not the plaques conceal within glass containers. These objects have no consideration for contextual arrangement and are simply trophies to boost the events of white supremacy. The plaques overshine these miscellaneous artefacts. Alongside the plaque's altitude, the bench placed in the centre of the room looking at the plaques guides people away from the other objects with the suggestion of a higher value communicating this arrangement should be considered and deserves more of your time than other artefacts.

In 1984, Liverpool-born artist Tony Phillips created a series of etch prints that consider the Benin Bronzes' history and their forcible removal from Benin. He wrote, 'The series is not only a comment on colonial appropriation but also on the immutability of the art object in the face of changed cultural contexts – the work retaining its power and beauty despite being relieved of its original function.'

In this image, the fourth of twelve plates, we see the richly ornate interior of the Oba’s palace prior to the British raid, with cast brass plaques and court members in the foreground. Having a visual asset like this in the museum would immediately help people imagine the rich heritage of Benin. But instead, the lack of visual aid is another method implied by the British Museum to downplay the scale of the invasion and narrate the Kingdom of Benin as a third-world territory far behind the curve of our western society.

British Museum Political Controversy

Founded from the collections of Sir Hans Sloane, an Irish-born doctor and slaveowner, many British Museum objects operate through colonial injustice. Alongside countless contested artefacts like the Benin Bronzes and hoa hakananai’a, there are no black curators within the British Museum.

As Sara Wajid, head of engagement at the Museum of London and a member of Museum Detox, say in a BBC interview.

“In most museums the place where you see black staff is in cleaning and security. You won’t see them in curatorial departments, you won’t see them in management.”

Her point is exemplified by the British Museum. Hartwig Fischer, director of the British Museum, acknowledges in the same interview that the institution lacks any black curators among its 150-person curatorial staff, calling it “a big issue we need to address.” So what is it that makes the British Museum British? Perhaps Dan Hicks’s simple act of changing an “i” to a “u” in his book ‘The Brutish Museums’ would be good alternative name for the museum. It reflects the British Museum’s efforts of decolonialism, restitution, and cultural representation... brute.

The British museum acts as an informal weapon to project the continued impacts of institutional racism and the horrific worldview of civilisation's military triumph over the primitive into the present. The wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Palestine, one of the longestrunning conflicts in the world, have brought back corporate militarist colonialism, replicating the Benin Expedition of 1897. In a July 2004 article for the Guardian, Neil MacGregor drew a clear comparison between the recent invasion of Iraq and the looting of Benin City.

“The Benin bronzes [are] some of the greatest achievements of sculpture from any period. The brass plaques were made to be fixed to the palace of the Oba, the king of Benin, one above the other, a display of technological virtuosity and sheer wealth guaranteed to daunt any visitor. At the end of the 19th century, the plaques were removed and put in storage while the palace was rebuilt. A British legation, travelling to Benin at a sacred season of the year when such visits were forbidden, was killed, though not on the orders of the Oba himself. In retaliation, the British mounted a punitive expedition against Benin. Civil order collapsed (Baghdad comes to mind), the plaques and other objects were seized and sold, ultimately winding up in the museums of London, Berlin, Paris, and New York. There they caused a sensation. It was a revelation to western artists and scholars, and above all to the public, that metal work of this refinement had been made in 16th-century Africa. Out of the terrible circumstances of the 1897 dispersal, a new, more securely grounded view of Africa and of African culture could be formed.”

Through exploitative colonialism and regime change (now for the oil reserves of Iraq rather than the Kingdom of Benin's rubber and palm oil), the Iraq War was carried out to further the goals of multinational companies. Tens of thousands of artefacts were stolen from the Iraqi National Museum during this slaughter, evoking yet another analogy to Benin.

BP, one of the world's leading international oil and gas companies and is one of the biggest sponsors of the British Museum. It comes as no surprise that BP were involved in major controversy leading up to the Iraq war for oil. In an April 2011 article for the Independent, Paul Bignell reported that government documents showed that plans were discussed to exploit Iraq's oil reserves by government ministers and the world's largest oil companies the year before Britain took a leading role in invading Iraq.

In March 2003, just before Britain went to war, Shell denounced reports that it had held talks with Downing Street about Iraqi oil as "highly inaccurate" and denied that it had any "strategic interest".

BP, 12 March 2003: "We have no strategic interest in Iraq. If whoever comes to power wants Western involvement to post the war, if there is a war, all we have ever said is that it should be on a level playing field. We are certainly not pushing for involvement."

Lord Browne, the then-BP chief executive, 12 March 2003: "It is not in my or BP's opinion, a war about oil. Iraq is an important producer, but it must decide what to do with its patrimony and oil."

Documents from October and November of the previous year, however, present a different perspective.

Foreign Office memorandum, 13 November 2002, following meeting with BP: "Iraq is the big oil prospect. BP are desperate to get in there and anxious that political deals should not deny them the opportunity to compete. The long-term potential is enormous..."

Later that year, when the early stages of the war had officially concluded in May and Baghdad, the capital city of Iraq, had been captured, BP began a technical evaluation of the Rumaila Oil Field, the second largest in the world. By 2009, BP had secured a service agreement to increase field production.

BP, who had earlier funded the Tate institution and several minor endeavours, dramatically increased the sponsorship of "global culture" in the new environment created by the recent acts of war. It was revealed that over a 17-year period BP gave an embarrassingly small total figure of £3.8m to the Tate a highly diversified institution that champions empathy through their exhibits. To compare, BP gave £1.5 million to build the BP Lecture Theatre in the Great Court of the British Museum in the year 2000 and in 2016, BP revealed a five-year partnership of £7.5 million to support four cultural institutions that included the British museum. This would amount to £375,000 per year for the British Museum if distributed equally among the four.

Although today’s controversy of the British Museums and BP partnership lies between how the oil company ‘falls short’ in response to climate crisis. We cannot undermine the suggestion that BP sponsor the British Museum a cultural institution to downplay their wrongdoing and offload controversy. It sparks further questioning of whether museums should accept donations and artefacts from societies controversial minority elites such as large contentious businesses and colonisers.

Demonstrations of Decoloniality

As previously noted through Sumaya Kassims observations of The Past Is Now exhibition at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, decoloniality is a complex set of ideas. As colonialism has left different marks on different communities and their institutions, it involves more than simply unpicking museum's contemporary colonial ties. In addition to the return of the objects, this may also involve new educational initiatives, revised hiring practises, altered exhibition narratives, and open discussion and highlighting of colonial legacies and issues. Decoloniality requires a unique approach in every case.

Decolonising museums is a difficult task because they have historically served as privileged, exclusive spaces for societies minority elites such as colonisers. Increasing inclusivity has been a key objective of the museum's expanding social role although backward thinks fear that museums might lose authority in the process. It is a goal to employ staff members who represent communities so that the museum speaks for people rather than on their behalf. These aims, however, run the risk of creating the impression of token inclusion if staff employees are selected merely for their appearances and their ideas are not truly taken into consideration. Even though "common folk" can now enter "modern" museums, access is still rather restricted. Museum entrance is limited to specific days and hours, frequently with an admission cost, and visitor behaviour is frequently governed and observed by floor employees and social standards. Why are members of society still not welcomed and represented in museums, especially since many museums receive government financing obtained through visitors' taxes?

Using Csilla E. Ariese and Magdalena Wróblewska’s Practicing Decoloniality in Museums, a guide for how museums can experiment and implement methods of decentering, improving transparency, and increasing inclusivity, I visited the Museum of London to witness various practices of inclusivity. The exhibition at the London Before London gallery employed several strategies to encourage viewers’ use of their imaginations to create pictures of items that were only partially preserved. For instance, a big photograph of an experimental roundhouse or a recreated clay head of a lady adjacent to her fragmented skeleton remains. These resources aid visitors in gaining a clearer picture of the past by enabling them to look beyond limited material evidence.

By including different viewpoints in this display, the Museum furthered inclusivity. These include the poet-in-residence at the Museum of London, Bernardine Evaristo, who discusses how she views the era in her poems, and the involvement of local school children in the creation of the art piece, Gifts to the Water, which illustrates how Neolithic artefacts made their way into the Thames.

To see whether exhibits like British Museums' poor narrative of the Benin Bronzes could improve its decoloniality, I visited the National Museums Liverpool, World Museum Benin and Liverpool Exhibit. Unlike the British Museum, whose exhibition uses the Benin artefacts as trophies to celebrate white supremacy, the redeveloped Benin Liverpool exhibition brings absent voices together, creating new narratives for the collection of Benin artefacts. The museum actively invited Liverpool residents of African descent to discuss their concerns about the museum's previous Benin expedition, immediately practising increased inclusivity.

Before this discussion, similar to the British Museum, the old Benin Liverpool exhibit lacked inclusivity whilst displaying the artefacts. From a photograph taken from the previous exhibition, there appeared to be little visual empathy for the events of 1897 and the following aftermath. I again perceived the artefacts as pictorial works of art following suit Apler's ideology of the 'museum effect', the removal of objects from their context and misrepresenting people's cultures.

The commemorative elephant tusks demonstrate this as they're placed and arranged like trophies in the centre of the room in a glass cabinet. The carving on the trunks was commissioned by Oba Ovonramwen in 1888 as an altar to honour his father and predecessor, Oba Adolo. Placed within its context, you instantly gain a better understanding and representation of the country's culture. A glass cabinet doesn't resemble the tusk's cultural significance.

However, following the concerns raised, the World Museum now explicitly draws attention to the greater awareness of Benin and the need to work together for change. Exemplified on large walls, newspaper articles, photos, and quotes demonstrate the need for change and how Benin was once an architectural phenomenon.

Although the World Museum still obtains 71 Benin artefacts, the museum also reasonably and publicly justifies the need for them on display, as according to Nigerian-born artist and workshop facilitator Leo Asemota "Benin's narrative is so connected to many other narratives."

I feel that now more than ever, museums have the opportunity to perform decolonialism and restitution through the return of the Benin Bronzes, especially in light of Adjaye Associates Edo Museum of West African Art in Benin City.

However, to respond to my initial enquiry, are museums resisting institutional change? Frustratingly the answer would have to be yes. Although decolonisation is taking place all around us at museums of all kinds, whether we consider them colonial or not, some institutions, like the British Museum, make little to no transformations and choose to resist change.

However, there is hope. As this illustrated essay has shown, institutions like the National Museums Liverpool World Museum can champion and demonstrate decoloniality by working with those who need to be represented by artefacts within the museums. I hope institutions like the British Museum are watching and deeply admire other museums’ practices of restitution and decoloniality. I hope the museums will realise that acts this amplitude will not tarnish the museum’s voice and authority but will increase their audiences and provide a more inclusive environment for people to marvel over cultural histories.

Every museum worldwide knows not to hold objects of such contested nature, but it’s a matter of practising decoloniality to serve this social injustice.

References

Adjaye Associates. (2022) Edo Museum of West African Art (EMOWAA). Available at: https://www.adjaye.com/work/edomuseum-of-west-african-art/ [Accessed 26 November 2022].

Ariese, C. & Wróblewska, M. (2021) Practicing Decoloniality in Museums : A Guide with Global Examples. [Online]. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Bignell, P. (2011) Secret memos expose link between oil firms and invasion of Iraq. Available at: https://www.independent. co.uk/news/uk/politics/secret-memos-expose-link-between-oil-firms-and-invasion-of-iraq-2269610.html [Accessed 29 November 2022]

Brown, M. (2015) Tate’s BP sponsorship was £150,000 to £330,000 a year, figures show. The Guardian, 26 January. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jan/26/tate-reveal-bp-sponsorship-150000-330000-platforminformation-tribunal [Accessed 2 December 2022].

Digital Benin. (2022) Institutions. Available at: https://digitalbenin.org/institutions [Accessed 27 October 2022].

Gompertz, W. (2020) How UK museums are responding to Black Lives Matter. BBC News, 29 June. Available at: https:// www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-53219869 [Accessed 20 October 2022].

Hicks, D. (2020) The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. [Online]. London: Pluto Press.

Karp, I & Lavine, S. (1991) Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Smithsonian Books.

Said, E. W. (2003) Orientalism. 25th anniversary ed. New York: Vintage.

Roper, H. T (1965) The Rise of Christian Europe. Thames and Hudson

Kasmani, S. The Past is Now. Available at: https://www.shaheenkasmani.com/the-past-is-now [Accessed 27 October 2022].

Khomani, N. (2022) Climate and heritage experts call on British Museum to end BP sponsorship. The Guardian, 19 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2022/apr/19/climate-and-heritage-experts-call-on-british-museum-toend-bp-sponsorship [Accessed 10 December 2022].

Macalister, T. (2016) US and Britain wrangled over Iraq’s oil in aftermath of war, Chilcot shows. The Guardian, 7 July. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jul/07/us-and-britain-wrangled-over-iraqs-oil-in-aftermath-of-warchilcot-shows [Accessed 13 November 2022].

MacGregor, N. (2004) The whole world in our hands. The Guardian, 24 July. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/ artanddesign/2004/jul/24/heritage.art [Accessed 20 December 2022].

National Museums Liverpool (n.d.) Benin and Liverpool. Available at: https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/benin-andliverpool [Accessed 16 November 2022].

Razzell, K. (2022)Benin Bronzes: Nigeria hails ‘great day’ as London museum signs over looted objects. BBC News, 28 November. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-63783561 [Accessed 28 December 2022].

The British Museum. (n.d.) Benin Bronzes. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/ contested-objects-collection/benin-bronzes

The British Museum (n.d.) Sponsorship case study bp. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/support-us/supportercase-studies/bp [Accessed 12 November 2022].

The Guardian. (2021) US to return 17,000 looted ancient artefacts to Iraq. 3 August. Available at: https://www.theguardian. com/world/2021/aug/03/us-to-return-17000-looted-ancient-artefacts-to-iraq [Accessed 14 November 2022].

V&A. (2000) IV. The Oba’s Palace. Available at: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O43987/iv-the-obas-palace-print-phillipstony/ [Accessed 5 November 2022]

Vice. (n.d.) The Unfiltered History Tour. Available at: https://theunfilteredhistorytour.com [Accessed 5 November 2022]

West, M. E. (1971) Divided Community. A A Balkema.