ENGLISH

Issue 21 volume 88

Monday 15th September

ENGLISH

Issue 21 volume 88

Monday 15th September

He āhuru mōwai refers to a safe space, a sheltered haven. Being Māori at an inherently western institution like Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington does not come without its challenges, and after a politically tumultuous last few years, it is becoming clear that our āhuru mōwai are crucial in so many respects.

The theme pays homage to the reawakening of our wharenui, Te Tumu Herenga Waka and the opening of the Pā, Ngā Mokopuna, at Kelburn Campus. For Māori students at the university, the marae is a physical embodiment of he āhuru mōwai. In their bracket performed at Te Huinga Tauira – the National Māori Students’ Conference 2025, Ngāi Tauira sung about seeking shelter at the base of the poutokomanawa from the harmful things in this ever-changing world. The name of our wharenui, ‘Te Tumu Herenga Waka’, refers to the hitching post where one can hitch their waka and embark on their journey at the university, in whatever capacity that may be. Those who were at the university before the marae closed, during the time of its closure, and are now here for its reopening, can attest to the importance of these physical spaces for Māori.

But it is not only physical places that can be āhuru mōwai. They are also the people that keep us grounded when we feel ourselves getting swept away; they are the environments that remind us of our purpose in pursuing higher education; they are the spaces that bring out our best and most authentic selves. For this issue of Te Ao Mārama, we wanted to give our students a platform to tell these stories – to talk about their āhuru mōwai and hopefully provide hope and inspiration to each other and to those reading this. Our āhuru mōwai are an exercise of tino rangatiratanga and mana motuhake that run contrary to the negative rhetoric being propagated by the media at the moment, proving that despite everything, Māori can and will continue to build and nurture spaces of safety, resistance, and happiness.

In these pages, you will see our āhuru mōwai take different shapes and can be expressed in many forms – from odes to people to the rhythm of poetry, from the reflections of tumuaki to mōteatea, these writings show us that our āhuru mōwai are not only a reflection of what exists right now, but give us purpose for future generations to come.

We hope you enjoy reading this edition of Te Ao Mārama!

Aria, Kaea, Taipari

Nā Manuhuia Bennett (Te Whānau a Hinetāpora) she/her)

Words by Manuhuia Bennett (Te Whānau a Hinetāpora) (he/him)

E whanga ana anō i tōku waharoa o Te Apa Māreikura a Māui Tikitiki a Taranga. Whakarongo pīkari rā te taringa ki te hou o te Kihikihi e āki kau ana ki te ātea. Ka kakapa mai te kara o Poukairangi kia tohu noa mai, kia tohu noa atu ki te iti, ki te rahi, ki te motu whānui. Tēnei te mauri whakapiki, tēnei te mauri whakakake, hei!

Ka whārōrō mai rā tōna whakairo ki runga ki te pou haki. He Kihikihi ana manu ki uta te ū ai mō te ake tonu atu. Ka whiti te rere ki Te Wheke a Muturangi konā rā ia ka rehu ki te mahau. Ko te mahau o te here, ko te mahau o te waka, ko te mahau o Te Tumu Herenga Waka, hei!

Kia toka ia rā ko te pae, ko te tūranga ki ngā matua tīpuna. He reo reitū, he puna wairua, he reo paihere ki te ira kawakawa. Ka whakanoa rā ko te tapu i te ātea, tū ana rā a Tū, takoto rā a Papa. Haere mai rā, haere mai rā, haere mai ki runga i ahau, hei!

E koro mā, e! E Ruka, e Moko, e Paaka, e Pā Tākirirangi! Ko te reo taraiti, ko te reo tararahi, ka niko te kupu, ka niwha te kōrero. Kia rongo atu au ki te rere o te kani me ōna kōrero. Āpiti hono, tātai hono. Āpiti hono, tātai hono, hei!

Ka kai atu rā ngā mata ki te kani tuarongo. Ko te pou tēnā o Māui Tikitiki, o Whātonga, o Tautoki, o Tara! Kia whai atu au i tōna tāhu, he mangopare, he ngoru, e kō. Pūkana whakarunga! Pūkana whakararo, hei!

Kia mātai atu rā ngā mata ki te takapau wharanui. He here nihoniho, he here roimata, he tukutuku poutama, e Rata! Ko te kiri kāpia, ka tokona ki runga, ka niko te herenga i te pakitara. Ko te pātaka kai iringa hoki o te kupu, o te kōrero, hei!

Kia hoki mai au ki te waharoa, ki te tomokanga. Ka rere te Kihikihi, ka rere te kīkiki. Hei pōhiri, hei karanga ki te iti, ki te rahi, ki te motu whānui! Ka huri au ki te herenga waka, he tārai whakapapa, hai!

Te Huihui o Matariki

Chi Huy Tran (Te Kā'ui Maunga, Rereahu, he/him)

At Koroneihana this year at Tuurangawaewae Marae, Te Arikinui Nga wai hono i te po, the new Maaori Queen, gave her first public address since ascending to the throne. Reflecting on the past year of grief following the loss of her father, Kiing Tuheitia, she spoke with raw emotion about her journey of healing. "In those moments of escape, no matter how much I tried or wished for the tears to stop falling, they flowed like the Waikato River," she said, as she shared the depth of her loss and the comfort she found in the support of her whaanau.

Looking to the future, the Queen announced the launch of a new indigenous economic summit and an investment fund designed to help Maaori communities build economic independence.

Waikato-Tainui leader Tukoroirangi Morgan hailed the Queen's new approach, highlighting her commitment to intergenerational business practices. Many attendees at Koroneihana, including Te Paati Maaori co-leader Debbie NgarewaPacker, were inspired by the Queen’s words, feeling a renewed sense of hope for a brighter future for Maaori.

The Queen's speech, delivered with strength and grace, called for a new direction for Maaori. She emphasised that being Maaori isn't defi ned by constant struggle or fighting external forces, but by embracing language, culture, and a deep care for the environment. “Being Maaori is speaking our language, it is taking care of the environment, it is learning about our history,” she said, challenging the idea that

Ahead of the 2026 general election, Labour is reassessing its approach after losing the Tāmaki Makaurau by-election to Te Pāti Māori’s Oriini Kaipara, who received over 6,000 votes. Labour’s Peeni Henare, who was defeated, pointed to low voter turnout (27.1%) and issues with the Labour government’s stance on Māori rights as key factors. Labour MPs, like Willie Jackson, acknowledged the need to rebuild trust with Māori voters, with Jackson noting the shifting nature of Māori political support. Labour’s Chris Hipkins recognised Te Pāti Māori’s stronger

message, particularly since Henare already holds a seat in Parliament.

As 2026 approaches, both Labour and Te Pāti Māori will need to address these tensions and rebuild their connections with Māori voters.

Green Party MP Benjamin Doyle has made the difficult decision to resign from Paremata, citing the toll of ongoing threats and online abuse (āe, I’m talking about you Winnie � �). Doyle, who entered Parliament just last year, shared that the harassment – including death threats aimed at them and their whānau – had become too much to bear. Despite the pain, Doyle has shown incredible strength, putting the wellbeing of their family first.

saying, "Whānau is the most precious thing in the world," and chose to step away to protect them.

In their statement, Doyle reflected on the months of healing that led to this decision, expressing gratitude for the opportunity to represent their communities. They acknowledged the challenges they faced,

Doyle’s resignation is a reminder of the harsh realities many public figures face, especially those who are targeted with hate and violence. We stand with Doyle and their whānau in this time of need.

Kia kaha e hoa !

ealities many public figures face, especially those who are targeted with hate and violence. We stand with Doyle and their whānau in this time of need.

Kia kaha e hoa !

He Ahuru Mōwai

Understanding what this journey means to me begins with where I come from. I am from te nōta, born and raised in Whangārei. My Papa is Croatian, and my Mama is my Māori (among other European variants) parent. We didn’t grow up particularly

haka gave me a place to engage with my Māoritanga in practice and surround myself with other Māori. I stuck with the practices and participated in my first performance at a Cultural Night. All my flatmates came to watch, and even though my actions were

Rotorua. Like many urban Māori, the distance to our marae meant I didn’t spend much time there growing up – maybe only a couple of visits. All that to say, I didn’t grow up feeling Māori.

When I started applying for Vic and looking at Scholarships, the Totoweka Equity Scholarship for tauira Māori caught my eye. I was no more secure in my Māoritanga by this point and ended up consulting a school friend and current member of Ngāi Tauira about it. Did I deserve this scholarship as a Māori who spent no time on their whenua? Whose name was unknown on the marae? He simply affirmed to me that to whakapapa Māori was enough.

So here I was. In a brand new city, on a Māori scholarship, pursuing an education in a discipline founded on Western thinking, practices, and research. In all realness, I had no idea what I was doing or where I wanted psychology to take me. It wasn’t until I had a lecture in Kaupapa Māori research that I realised there were other paths I could take. I changed my courses in Tri 2 and enrolled in MAOR123 – Māori Society and Culture. It was in that class that I made one truly extraordinary friend who loved and encouraged me tirelessly. If I could offer anyone in a similar position a piece of advice, it would be to find a friend who will push you into spaces you would not otherwise have the confidence to enter. With her support, I finally took up te reo Māori classes and went to my first kapa aka practice with Ngāi Tauira.

I’m not going to pretend I was immediately at home there – I’m not super coordinated, nor can I sing, but I started making a couple of friends. Regardless of my success as a performer, kapa

Late last year, Ngāi Tauira had plans to go on a trip up north. While I thought there was no way I’d make the team, I got a last minute invite and accepting it was one of my best decisions. On that trip, I spent more time on marae than I have in my whole life, expanding my knowledge of tikanga. We spent a week exploring the north, doing challenges, and having an excessive amount of fun. Most rewardingly, I got to see the same mate who told me to take that scholarship, basking in the joy of sharing his home and local mātauranga with our rōpū. I walked away with 30 new friends.

In December, I had the absolute privilege of participating in the powhiri for the reawakening of our marae, Te Tumu Herenga Waka, and the opening of our Living Pā, Ngā Mokopuna. These spaces are a hub for tauira and kaimahi Māori alike. While I haven’t had the same capacity for kapa haka practices this past Tri, simply being in these spaces has given me so many opportunities to expand my knowledge of Te Ao Māori and engage with different kaupapa.

So, for anyone who wants to explore their Māoritanga, my advice is this: hang around! Get involved. If you’re too intimidated to enter these spaces on your own, find a good friend who will undertake that journey with you. If you’re too busy to commit to sports or kapa haka, just inhabit our pā, because connecting with the people here will undoubtedly open doors for you. These people who have

unconditionally encouraged and supported me are my korowai of protection. Ngāi Tauira is my safe space and, today, I stand here more connected, more proud, and deeply grateful. Your journey might be different, but if you step forward, you will find your place, too.

For 9 months you carried me, kept me warm, kept me safe.

When I entered te ao mārama you continued to create a safe

You held me when I cried. You loved me when I tumbled.

You kissed me in the morning.

And said I love you at night.

You are and always have been the home I return to.

We have always had a special language between us.

More than just mother and daughter, 2 females in a male dominated house.

You say I’m more like dad but you and I, we always got each other.

Whenever a problem, you are the one I turn to.

It’s not that I wanted to go back to English, I loved the concept

of us speaking Māori.

I was lazy and probably scared of something new.

But today I struggled to translate a Māori word I was thinking

And yesterday I noticed when you used mātau instead of tātau.

Two weeks into it, I felt distant. I couldn’t converse freely,

You speak the language of our people and I return your tongue

I’m aware of my faults. I don’t meet you in the middle. in English.

But this journey is not about being perfect.

It has taught me how to listen. It has forced me to ask questions. Its made me alive to the breathing of these words, to the weight

I’ve learnt the beauty of our reo stretches far beyond the words itself.

Its in speaking it that I feel how our ancestors may have.

The journey we are on has unlocked a new realm.

Its regaining a perspective, relearning a whakapapa, interlacing my fingers with my past walking into the future. With my mother.

My mother has always been my safe place but now something is deeper.

Her tongue, the words she speaks, their meanings. All of it; more than their individual parts.

Its a touchless embrace. I feel closer to her.

Closer to me.

Words by Temepara Reihana (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu) (she/her)

You who burned the words “unlovable” into me, Beat them in until they bled out through my tears.

You didn’t stop for years.

My blood carried your burden,

Trickling down my arms,

Yet you didn’t care.

I couldn’t find my safe space in you.

You who treated me like a jailer, Made sure I knew I was a failure.

The academic endorsements weren’t enough, They never were.

Not enough to be your daughter.

I couldn’t find my safe space in you,

But I found it in them.

Them who healed a heart they didn’t break, Wiped tears they didn’t trigger,

When the ache of law exams got to me, They were there.

24/7, round the clock, forcing me to eat,

Routine checks just to make sure I was breathing. Desperate for my heart to beat.

I was trapped in this anxiety, Your words, your hatred, restraining me, But they set me free.

I questioned why they thought I was worth it, But they were having none of it.

When the ache of the world fell heavy on my shoulders,

As crushing as the Moeraki boulders, They sat with me.

And stitched up pieces I thought were broken beyond measure.

Them who taught me birthday wasn’t just another day, And could tell you all the quirky things I love to say.

Them who are the reason blood still runs through my veins.

They are safe. They are love.

Them who taught me it was okay to cry. I drilled that into others,

Pleaded with them to stay alive, But they were the first to drill it into me.

Through the dark and harrowing storms, The 3am tears, And the 4am nightmares, They were there. They held my hands, Played the songs of my favourite bands One took the scissors from my hands, And when I said I was sober, No longer an artist of my body,

They all cheered like they were my biggest fans.

I questioned why they thought I was worth it, But they were having none of it.

So for every kaupapa of theirs, I will be there.

Begged me to cry because at least then I was alive-can’t thrive if I die, right?

Cheering like the loudest aunty you know,

They wiped all my tears,

Stitched up my blood with laughter, Rewrote all my fears, They are safe. They are love.

They are Marino, my heart's true love.

They’ll be begging me to go home.

I will be there for all their storms, Even when we’ve left these Joan Stevens dorms, But I'll be there for their biggest wins too.

Even if it’s all the way in Timbuktu.

Because they are safe. They are love. They are Marino, my heart's true love.

Beneath the shadow of another day and shortly before the breaking of dawn

Tucked away, a blue pick-up from the hushed roadway

The groundkeeper and guardian of a second home with students drawn

The warmth from your coffee cup, like a solace, morning prayer

Like the company of a friend as you ready for the students' welcome

Unearth the sacred feet of newcomers, all from near or distant, where March to the beat of your drum

Here, I lay, stretched limbs out on the ātea, embedded in the soil

In the heat of the late summer sun, I stare out to the blue day overhead

Here you tend to these young scholars, like a garden you toil Like lost freshwater pearls, you lift us from the loose riverbed

To the early mornings, in the kitchen with a bellowed tune

Long until the languished nights, engulfed and true at last light

Tender are the meals that are fed to us with a silver spoon

Tender are the laughs that are shared with us warm as daylight

The cup of gratitude I raise, overflowed and spilling

Sink your teeth into the fruits of your labour

Catch it, in the mesh of your butterfly net, fulfilling The light and spirit of this sacred space and you, as it's curator

T

ūkōrehu had heard the stories – Auckland, the city where dreams were made. The place of endless opportunity, towering skyscrapers, buzzing streets, and a melting pot of cultures. At twenty years old, with $2,600 saved from summer mahi in the shearing sheds and fruit orchards, he boarded the bus from his papa kāinga toTāmaki Makaurau, determined to carve his own path before starting his studies.

The first week was magic. The city’s lights dazzled him; the hum of buses, trains, and late-night chatter filled the air. There was always something to do – open mic nights in tucked-away bars, street food markets with flavours from every corner of the globe, museums and galleries that opened his mind to worlds he had never known. For the first time, he could walk down a street and be just another face in the crowd – no expectations, no whakapapa hanging over him, just freedom.

But the shine didn’t last. By the second week, reality hit hard. Rent for a small, damp room in a flat with four strangers swallowed nearly half his savings in one go. Food was expensive – even the

“cheap” noodles and bread seemed to drain his wallet faster than a day in the shearing sheds. Public transport was reliable, but at over $5 a trip, every outing became a calculation. Even public parking was brutal – $6 an hour in the city centre meant his dream of driving in Auckland stayed just that – a dream.

By week three, the struggles became more paru. A flatmate left dirty dishes piled high in the sink, the bathroom fan broke and filled the hallway with damp air, and the constant noise from the street meant he barely slept. Job hunting was tougher than he thought – “experience required” was the phrase that haunted every application. The city felt colder, not just in weather, but in how people moved past each other without a glance.

And yet, Tūkōrehu couldn’t deny the benefits. He learned how to budget every cent, how to navigate trains and buses like a local, and how to cook more than just boil-up and fry bread. He made friends from Samoa, India, and South Africa – each with their own stories of why they came here. The city tested him, broke him down, and rebuilt him with harder edges and sharper instincts.

By the fourth week, his savings were gone. He was tired, hungry, and staring down the reality that without stable mahi, he couldn’t keep his head above water. Pride swallowed, he booked his ticket back to the country. The bus ride home was quieter, the lights of the city shrinking behind him. He didn’t leave defeated – he left knowing the truth: Auckland could give you everything, but it demanded everything in return.

Back in his papa kāinga, the air smelled fresher, the stars shone brighter, and his whānau’s voices felt warmer as he speaks about all of his stories of “the big city” cracking jokes and all. But deep inside, Tūkōrehu carried the lessons of the city. He had seen the cost of independence, the reality of surviving without a safety net, and the raw beauty of standing on his own two feet, even if only for a month. The city had tested him – and he knew he would return, still his whanau continues give him shit about the whole situation in the most loving way possible. Right now it doesn't look like he's gonna hear the end of “how the cuzzie boy farked of to town, spent all his money and came back broke”.

For a long time, I thought survival was enough.

I thought if I could just keep moving, ticking boxes, showing up, staying busy, that would be enough to keep me from falling apart. But survival is a cold kind of safety. It’s hard and brittle, a scaffolding that threatens to collapse the moment you let yourself feel too much.

I didn’t realise I was grieving, not just my dad, but something bigger. The quiet, sturdy feeling of my sheltered haven. That place inside you that feels warm and known. The sense that no matter how hard life gets, there is somewhere you can return to. Someone who will hold you.

As children, our first āhuru mōwai is often our māmā. Her body becomes our first home. Her voice is the first sound we know. From there, safety radiates outward, to our parents, our whānau, our whenua. This sense of attachment, of secure, loving connection, lays the foundation for how we relate to others and ourselves. When that attachment is disrupted, whether through death, trauma, or disconnection from culture, it leaves behind a deep ache. But safety like that is fragile. When you lose someone who once held that space for you: a parent, a kaumātua, someone who tethered you to your senseof belonging, the ache can be immense. It can dislodge you from yourself.

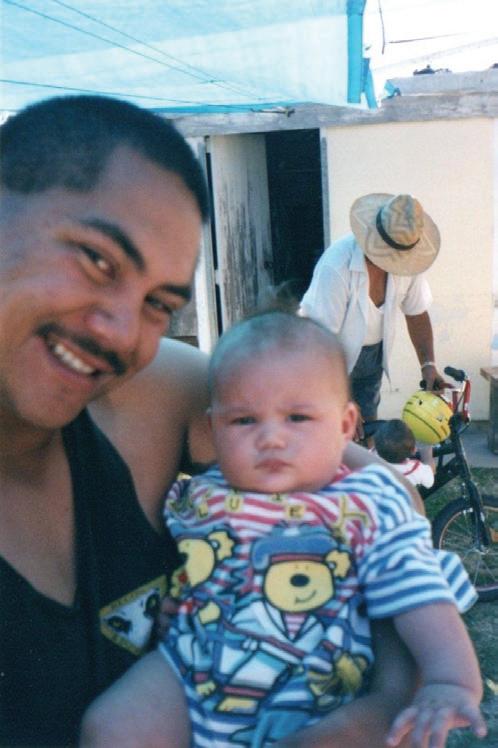

For me, that person was my dad.

He was loud in his love. He was always the first to speak, the one to take centre stage. He was consistent. He showed up. He was

soft in ways that made the world feel less sharp. And whenhe died, everything got louder, and lonelier. The world stopped making sense, but I didn’t knowhow to say that out loud.

In psychology, we talk a lot about attachment. The bonds we form with our caregivers, the patterns we carry into adulthood, and the ways we learn to feel (or not feel) safe. In Mātauranga Māori, these attachments aren’t just personal. They’re intergenerational. They’re spiritual. They’re rooted in whakapapa the long line of people, places, and stories we descend from.

When I lost my dad, I didn’t just lose a parent. I lost an anchor to my sense of stability, to the parts of me that only he truly knew. It felt like someone had cut a thread between who I was and who I used to be.

And I did what many of us do in the face of deep pain: I buried it. I distracted myself. I became the strong one. The capable one. The one who didn’t need to talk about the ache in her chest, or the tears that never seemed to fall at the “right” time.

But no one can outrun grief forever.

Healing, true, honest healing is slow. And uneven. It doesn’t look like a straight line or a sudden breakthrough. It looks like small decisions to keep showing up. It looks like allowing yourself to be soft in a world that taught you to be hard. It looks like returning

to the people, places, and parts of yourself that once felt safe. It took time for me to realise that I was allowed to feel again. That I was allowed to miss my dad, even years later. That I didn’t need to “move on” I just needed to find ways to carry him forward. I started noticing him in small things. In the smell of rain on warm concrete. In the way someone laughed from deep in their puku. In the music he used to hum under his breath when he thought no one was listening. I started speaking to him in my thoughts not always with words, but in memory, in presence.

And slowly, I began to heal.

He āhuru mōwai isn’t always a place. Sometimes it’s a person. Sometimes it’s a feeling. Sometimes it’s a moment of stillness when your nervous system finally lets go. Sometimes it’s love that doesn’t demand anything from you that just lets you be.

My partner has become part of that return. His patience, his warmth, his ability to sit with me in silence it reminded me what it feels like to be held. He didn’t try to fix me. He didn’t ask me to perform resilience. He just made room for me. And in doing so, helped me make room for myself.

But I also found pieces of that safety in reconnecting with my whakapapa. In reclaiming te reo. In returning to the stories and traditions that my dad valued, some spoken, others passed on quietly through how he lived. I found healing in the whenua. In the ocean. In karakia. In community.

This is the long return. The slow walk home to myself.

I’ve come to believe that we don’t just return to safety we build it. We shape it in our relationships, our communities, our kaupapa. We become it for others.

For Māori, healing isn’t individual. It’s collective. It’s whakapapa. It’s whanaungatanga. It’s knowing that when one of us comes home to ourselves, we open the door a little wider for the next.

So now, when I think of he āhuru mōwai, I think of legacy. I think of my dad. I think of how much he gave, how much he carried, how quietly he made room for the rest of us. And I think of how I want to carry that forward not in a perfect, polished way, but in the small things.

A quiet kōrero. A warm meal. A place to land when everything feels too loud. A return to self, and to each other.

If you are still walking your own path back to safety, I want to say this: there is no timeline. There is no right way. The return might be long, and winding, and messy. But it is always possible. You do not have to stay in survival mode forever. You are allowed softness. You are allowed to miss people. You are allowed to be held. You are allowed to come home — to yourself, to your whakapapa, to the parts of you that never stopped longing for he āhuru mōwai.

And when you do, know that you’re not alone.

Many of us are walking the long return.

Togther.

Words by Kaea Hudson (Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Awa, Tūhoe) (she/her)

On the 6th of December 2024, a dawn ceremony heralded the opening of the Living Pā Ngā Mokopuna and the reawakening of the university marae Te Tumu Herenga Waka.

Before sunrise, we gathered on Kelburn Parade, waiting in the dark for the call to begin. Today was the day, a long time coming. This was definitely the earliest I have been at uni - with formalities starting at 4:30am. The pūtātara sounded, and we began the slow march from the road and past the new Pā to wait at the waharoa.

Our whare has been asleep since 2021, and this event marked its reawakening. Following behind the puhi and the tohunga, we watched reverently as they chanted karakia. Once finished, we walked in, circling the whole whare and touching each pou. “Good morning", “we missed you”, “it is good to see you again”. For most of the students present, it was their first time in the marae. For me, it felt a bit like coming home; it was this marae that welcomed me during the Māori O-week pōwhiri when I was a first-year.

The wait is over, our safe space is open again.

Then we turned to the opening of the new living pā, Ngā Mokopuna. We walked through, touching the walls as the mana whenua blessed the building floor by floor. We greeted our new friends: the constellation projection artwork, the pounamu in the wharekai and the huia birds behind the second-floor staircase. This was the beginning of making memories with Ngā Mokopuna. In the dark, we tried to imagine what our lives would look like with the Pā and marae open, predicting late night study sessions in the NT room and naps on the marae mattresses. The name Ngā Mokopuna came from the original Kelburn Parade wharekai. The building is new, but the ethic of manaaki is not. Here is our new home.

To conclude the formalities and greet the rising sun, we moved to the Hub for breakfast and a sing-song. We spent weeks practicing, reviving some old Ngāi Tauira favourites from cohorts past. The Hub was buzzing and so were we. We (finally) had breakfast and heard speeches from Deputy-Vice Chancellor Māori, Rāwinia Higgins, the Pā architects and others. . It was a memorable day and the speakers expressing such care made me excited for the year ahead. The early wake-up - and three years of waiting - were worth it.

Words by Aria Ngarimu (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongomaiwahine, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui) (she/her)

I recently had the privilege of listening to Te Kahukura Boynton, aka Māori Millionaire, speakvabout money. Her talk left me thinking about how many of us have complicated relationshipsvwith money. We know that Māori and Pasifika experience poverty at a disproportionate rate compared to the rest of the population; financial stability isn’t necessarily a familiar feeling. So many of us have seen it, grown up in it, or are living it right now, and it can be easy to internalise these experiences into subconscious beliefs about money:

If you’re someone who cares about people, your community, the environment, your language, culture, etc., money can never take those things away. It simply provides you with additional ways to express those values.

“rich people are greedy”

“money changes you”

“you don’t need money to be happy”

The reality is that wealth today is primarily held by people and systems that don’t prioritise collective wellbeing. But if we look to build wealth in a diverse range of spaces, we can then channel it into those communities and towards kaupapa that we know are significantly under-resourced. It looks like papakāinga that shelter our whānau; like feeding our loved ones healthy, nutritious kai from our māra and takutai; like time, energy and money towards the things that are important to us.

... and honestly, there is truth in all of those. Rich people can be greedy. Money can affect ego and change the way people treat each other. And it isn’t the key to genuine happiness. But do these truths tell the whole story? Maybe things are a bit more complex. Because whether we like it or not, money shapes our choices and gives us options.

Many of us were never taught how to manage money. The extent of my financial education when I left school was “work hard, get a good job, avoid loans, and save money if you can”. That’s probably more than some, but it’s not enough. Why are so many of us stuck living paycheck to paycheck? Why don’t we know anything about KiwiSaver? Or how to build passive income?

It gives us agency over the work we do, the time and energy we dedicate to it, and where we choose to spend the rest. It can create space, giving us the freedom to spend time with the people we love, rest when we need it, and support our communities without sacrificing our well-being. One of the things Te Kahukura said was that money doesn’t actually change who you are; it just amplifies the person you already were.

I’m not saying that we should strive to own mansions or have expensive cars; we know what wealth looks like in terms of our values. We don’t need to become obsessed with it, or hoard it, or show it off . But if we can de-stigmatise our perceptions of money, we can stop letting it control and limit our current and future realities. The sooner we do that, the sooner we can start building futures of abundance that are secure and sustainable for generations to come.

Words by Nathaniel Cashell (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Toa, Ngāi Tahu) (he/him)

Tāmati Durie-McGrath (Ngāti Kauwhata, Ngāti Raukawa ki te Tonga, Rangitane, Ngāti Rangatahi) (he/him)

Ko te whāinga matua o Ngā Rangahautira ko te poipoi me te raupī i ngā tauira Māori o Te Kauhanganui Tātai Ture o Te Herenga Waka. Ka tutuki ēnei whāinga mā te whakaoho me te whakaara mai anō i ngā tikanga a kui mā, a koro mā e noho muna ana ki roto i ā tātou tauira mohoa nei. Ko te manako ia, mā ēnei tikanga te rangatiratanga o te tauira e whitawhita mai anō, ā, kawea ai ērā pūmanawa me ērā āhuatanga puta noa ki Ngāi Māori whānui, te haere ake nei.

We as Ngā Rangahautra aspire and focus on supporting tauira Māori through their law degrees and aim to see them cross the stage at Hui Whakapumau. We began as a small study group in the early 1980s by Tā Justice Joe Williams, Ani Mikaere, and Toni Waho. From the start, we were active in advocacy, making submissions to the Fisheries Select Committee in 1982 and on integrating tikanga Māori into legal studies to our law faculty in 1984. That original group, and up until today, take inspiration from the rangatira Te Kooti Arikirangi korero: “Mā te ture ano te ture, e aki. only the law can be pitted against the law.” We use this korero to guide us through our journey at law school.

In 1988, the late Pāpā Moana Jackson sought assistance from Hōhua Tutengaehe, a rangatira from Matakana, who gifted us the name Ngā Rangāhautira. Ngā (plural), ranga (weave), rangahau (research), and tira (group) form a play on the word rangatira (Chief, Leader). It captures the idea of the search for knowledge beginning people together. The deeper meaning of our ingoa is about empowering ourselves within a system which fundamentally disempowers Māori. This is a reflection of our commitment to uplift te ao Māori within the kāwanatanga legal system.

Created in 2006 by Barry Te Whatu and Mary Jane Waru, it features a manaia (mythical creature) holding a gavel and scroll on a poutama (step pattern), representing identity, law, achievement, and the journey of learning.

This year, we have been privileged to host a number of incredible kaupapa. These have included workshops and kaupapa Māori competitions, notably our negotiation competition, which we were proud to host at Te Tumu Herenga Waka, and our moot competition, held at the Old High Court. We were also honoured to send a group to Auckland for the inaugural Hui ā-Tauira. In addition, for the first time, we have the opportunity to send a group to Melbourne, Australia, to participate in an Indigenous Exchange.

We are looking forward to ending the year on a high and we are very grateful to everyone that has been involved and contributed this year! Kaua e wareware, there are still many more exciting things to come!

For more information:

Instagram: @nga_rangahautira

Facebook: Ngā Rangahautira 2025

Ngā mihi maioha!

Words by Phaedra Chin (Te Rarawa, Te Aupōuri) (she/her)

Aria Ngarimu (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongomaiwahine, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui) (she/her)

This year, 12 of Ngā Rangahautira’s senior law students went international and spent a week in Naarm, the city of five million otherwise known as Melbourne.

The trip across the ditch came about from a meeting of chance: in December 2024, a delegation from the University of Melbourne Law School Indigenous Law and Justice Hub were visiting our very own Te Kauhanganui Tātai Ture, Faculty of Law here at Te Herenga Waka. Led by Professor Eddie Cubillo, their visit included marae stays, whakawhanaungatanga, and kōrero about tikanga Māori and First Nations law in Australia. On a tour of the law building, they came across the little MPI room, where current student, Jimmy Fiso, was studying. No one knows exactly how their conversation went, but less than a year later we were packing our bags for Australia.

Following a 3am wake up to make our flight, our first day was spent learning about the land, people, and being welcomed to Country by the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation. We walked across the University of Melbourne campus; as the second-largest landowner in Melbourne it took quite some time. We learnt about the rivers that once ran strong through the land, a source of food and life for the Wurundjeri people, now buried beneath buildings and grassy fields, much like the Kumutōtō in Te Whanganui-a-Tara.

Day Two focused on the Australian legal system with lectures and tours of the Law School. Australia has a federal structure that distributes powers between the Commonwealth (federal) and state governments. We refl ected on the 2023 Voice to Parliament Referendum which proposed to alter the Australian Constitution to recognise First Peoples and establish an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to advise governing bodies on matters relevant to Indigenous Peoples in Australia. Although the referendum failed, the State of Victoria is going ahead to negotiate their own Treaty(ies). Three of our very own tauira, Nate, Kaea and Tamati presented their Te Rauhī i te Tikanga research project at the inaugural Indigenous Higher Degree Research Summit 2025. The day finished with an exhibition at the Potter Museum of Art: 65000 Years – A Short History of Australian Art.

Now that we had some context regarding the political and social systems at play in Melbourne, the State of Victoria, and Australia more broadly, the next day was spent visiting some key organisations working with Indigenous Peoples in legal settings. We visited the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service, a community law centre that provides free legal advice and representation for Indigenous Peoples in Melbourne, focusing on Civil, Family and Criminal law. It was disheartening to hear about the challenges Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders face in the Australian legal systems, but we also realised the stark similarities in our struggles. In the afternoon, we visited the Treaty Authority, an independent body that oversees Treaty-making in Victoria. Because the Treaty negotiations are in such an early stage compared to where we are in Aotearoa, it was a lot to wrap our heads around. The team members at the Treaty Authority joined us for a wananga about the range of work that they undertakefrom Treaty education and community engagement to Traditional Owner Treaties which relate to matters that are important to Traditional Owners in their local areas.

The fourth day started with a lecture and interview with Maggie Munn who told us about her work at the Human Rights Law Centre as the Director of the First Nations Justice team. Many of our tauira are interested in human rights advocacy, so Maggie happily answered their burning questions. After that, we headed to the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria - the democratically elected body to represent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the ongoing Treaty negotiations. We had a rich discussion about their aspirations for Treaty, and their ideal negotiation framework. That evening we attended a panel on Indigenous legal education. Amongst keynote speakers Eddie Cubillo and Chair of the Treaty Authority, Jidah Clark, was a familiar face - Dr Carwyn Jones.

We started our final day back at the law school, where we heard from Rita Seumanutafa-Palala and Dylan Asafo about their PhD research on Pacific law. We were invited to the Pacific Islands Student Association room, where we enjoyed kava, kōrero, and waiata!

As our week in Naarm came to an end, we were grateful for all that we packed into one week - lectures, wānanga, kōrero that challenged us, but also strengthened our knowledge and understanding of the Indigenous experience in a legal context in Victoria, Australia. Reflecting on the opportunity to stand alongside our Indigenous whanau in Australia, we are filled with a responsibility to continue the conversations that we shared. For Ngā Rangahautira, it was more than a study tour, it was a reminder that our struggles and aspirations are shared.

Within my family there are a few kīwaha that often fill the air of our whare; “He aha te mea nui o te ao?”, “Kia tau te rangimarie!”, “He aha te kai o te rangatira, he kōrero.”. But none with as much potency and love as “he iti pounamu,” – though it is small, it is precious. It's this whakaaro that comes to mind when thinking of the small community of tauira Māori at Te Kura Hoahoa, and its value despite its demure size.

Society, especially our current one, values the greatness of singular men and the lone accomplishments of greatest magnitude, and thus, can forget the value of small goodness, of discrete company, and mutual understanding. The ability to come into a space where, even though there are not many, there are people who understand what you may be going through. This small community, this micro-whanaungatanga, makes up much of the comforts we take as tauira Māori in a tertiary institution.

Further for Māori, we find huge importance in Built Environment and Design. Our whare, our toi, our taonga; they give physicality to the tikanga we hold dear, yet the modern day industries and educational pipelines tauira Māori find themselves lacking the ability to be together, a core facet of our world. Design is inherently collaborative, yet architecture and design classes increasingly find students tucked away into their corners, doing work, trying to meet a litany of deadlines. Iterations, redraws and revisions fill in the time that used to belong to being with others, with whānau, with friends.

So when I first spoke to other students about the possibility of starting something like Te Paepaeroa , the first thing occupying our thoughts was the necessity of a community, and the possibility of just creating one, versus a natural formation happening. At Te Aro, you have your people, but very rarely are you able to spend time with them. So this year, with Te Paepaeroa becoming a reality, there are many things that could be pointed to when reflecting on TPR’s accomplishments; the industry connections made or the educational support supplied to students come to mind. However, the thing I’ve been most excited about is its presence.

Walking into the whānau room and seeing five or six people working to finish a project, complaining about a course or comparing their work: these seem like infinitesimally small things, but what they represent is much greater. Humans are social, we value connection, as it allows us to thrive, especially for Māori. That is not to say every Māori Architecture and Design student is in the whānau room, that there is a huge conglomeration of Māori every day. But the value of there being someone there, of there being a people and a place to go to, cannot be understated. It was my hope that something like that would welcome tauira Māori into university; to nudge them the right way, to make them feel like they weren't completely off the rails, to inspire them in their work. And though it hasn’t always been present, I’m glad that now there is a whānau to receive people, and hope that in the future it can grow as a community.

He iti? Āe. He pounamu? Āe, mārika!

Kia ora e te whānau,

Ngā Taura Umanga is the Māori Commerce Students Association here at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington. We exist to support all Māori students studying commerce, offering a space where we can uplift, connect, and grow together.

Our kaupapa is centred on helping tauira Māori thrive — not just in the classroom, but socially and professionally as well. Whether you're in your first year or final, we’re here to awhi you during your time at uni and help prepare you for the journey beyond.

What We’re About:

• Academic support: Study wānanga, peer connections, and encouragement to help you succeed.

• Social connection: Building a strong whānau of Māori commerce students through whakawhanaungatanga.

• Professional growth: Creating pathways and opportunities to connect with Māori professionals and businesses in the commerce space.

What’s Coming Up This Trimester:

Quiz Night – September

Te Wiki o te Reo Māori Sausage Sizzle – Friday 19 September

Māori Accountants Conference – September

AGM (Annual General Meeting) – October

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram @ngatauraumanga to stay up to date and get involved!

Ngā mihi nui, Kaleb Rongokea

Tumuaki

Ngā Taura Umanga

a. Wharekai tables

c. NT Common Room

Words by Amiria-Rose Monga (Ngāti Whātua, Te Uri o Hau, Cook Islands, Tahiti)

1. Where is your go-to study spot in Ngā Mokopuna?

b. The desk outside of Āwhina

d. Vaper’s area (Find me anywhere but a desk)

2. What shoes are you wearing in the wharekai?

a. Sneakers (preferably pink) for speed and mobility

b. Crocs

c. Gumboots

d. Slides - Sorry, they’re not closed-toe shoes, safety hazard

3. What Ngāi Tauira kaupapa will we see you at next term?

a. Monday Parakuihi

b. Social Sports

c. Kapa Haka bleh

d. See you at Ball!

4. Where’s the first stop after pre’s?

a. What do you know about Siglo and Boston?

b. The Residence (especially on a Thursday)

d. Shady Ladyyy

6. When you’re feeling a bit tired, where is your goto nap spot?

a. Marae mattresses right at the feet of my tupuna

b. Sleeping on campus? Nah I’m going home.

c. Maybe a little nap at the desk but locking in after 15 minutes.

c. Sassy’s (paired with J&M’s)

5. You’re on AUX, what song are you putting on?

a. Something in ‘Aotearoa Songbook’

b. Love Season - J Boog

c. Normal Girl - SZA

d. Real underground, idk if you’ll know them

d. NT room - Blanket? Check. Pillow? Check. Couch or bean-bag free? Check.

7. What is your favourite colour?

a. Āwhina Red

b. Wellington Harbour Blue

c. Pohutukawa Green

d. Slick Black

8. What whakatauki speaks to you?

a. Haere taka mua, taka muri; kaua e whai - Be a leader not a follower.

b. Kāore te kumara e kōrero mō tōna ake reka - The kumara does not say how sweet he is.

c. He rau ringa e oti ai - Many hands make light work.

d. Ahakoa he iti he pounamu - Although it is small, it is precious.

a. There’s orange juice in the kitchenette xx

b. Just water will be good.

c. Cuppa tea

d. Live Plus energy drink from Subway

10. Who are you running to for help?

a. Tina

b. Tu

c. Shon

9. What are you drinking alongside your $8 marae lunch?

d. Someone on the NT exec

You’re the first person to stand up and collect everyone’s dishes. The kitchen is their kāinga rua, they know where everything goes. The bench is basically shaped to their body now, there’s a tea towel with their name sewn on it, and they know Tu’s playlist like the back of their hand. “Just on the far right, next to the milk”, Tina says as she directs you to a container of leftovers saved just for you. And if you’re walking past Ngā Mokopuna, someone is waving you over for first dibs on the baking.

Maybe cooking isn’t your strong suit, a little too messy for your liking. Maybe you have an irrational fear of all the floaties in the dishwashing sink, and you’re not up for all the yapping and social butterflies in the kitchen. But there’s a man of few words roaming around lifting up tables and stacking chairs. Soon enough you’re being recruited as Tu’s shadow and you’re happy to go off and quietly do your part. The tables have to be reorganised exactly how Tu prefers it, not a single chair out of place, and don’t forget the 45 degree angle.

It’s just another day in the Pā. You’ve already done your rounds to the NT Common Room and said ‘Kia ora’ to the Āwhina staff. You’ve been locked in for the last hour and it’s time for marae lunch. But when your plate is looking a little empty, you feel a little tap on your shoulder…”Hey can you do me a favour?” Shon’s asked if you can wipe down all the tables and you can’t say no to the lovely Shon so up you get! Next minute, a spray bottle and cloth is in your hand, salt and pepper shakers need to be packed away and unused dishes to go back in the crates. Tell your friend they don’t need to wait up, there’s miscellaneous jobs to be done.

So you’ve been sitting down at lunch, taking your sweet time with the long conversations. Just long enough that hopefully ‘Titaoratanga in the flesh’ offers to take your empty plate. Fineeeee! If you insist! All of a sudden you’re busting to go to the bathroom just when people are picking up the tea towels and the Āwhina staff are looking for people to help out. Your DND phone just can’t stop ringing It looks like your mum is calling and you swear it’s important. Coincidentally it’s smoko time! But hey! You’re here now, even though there’s only a few dishes left. You’ve picked up a tea towel and have been drying the same cup for the last hour…weird.

Ngāi Tauira

Ko Ngā Rangahautira, ko Te Taura Umanga, ko Te Paepaeroa, Te Hōhaieti ngā hapū

Ko te #4 bus te waka

Ko Kelburn Campus te maunga

Ngā-roimata-o-ngā-tauira-ture

Ko Ngā-roimata-o-ngā-tauira-ture te awa

Ko Whānau House te marae

Ko Tū Temara te rangatira

Muriwhenua: You’re sick of explaining that you’re NOT Ngāpuhi and catching strays from all the Ngāpuhi hate just because you’re neighbours. You’re also wondering when Muriz is making top 9 at Matatini #NŌTINŌTA

Te Arawa: Are you from Whakaue or have you started saying you are since they won Matatini?

Kahungunu: Two words: hāngi pants. But you also gathered most of the kai for the hāngi too so it’s all good.

Ngāpuhi: The biggest iwi of them all – don’t expect them all to be on time. And don’t say FFN if you’re from Whangārei�

Tūhoe: You have some mean yarnangas but soon it’s time to step out of the mist and back it with some action. #allhui #nodui

Ngāti Toa: Why is it that everyone talks about what Hongi Hika but not Te Rauparaha�You love to rep Ka Mate, but can you do the other verses?

Kāti Māmoe: Tried minding their own business and somehow woke up as Kāi Tahu’s side quest

Taranaki: The Libras of Māoridom – they’re all about peace and balance. Won’t tell you when they have an issue with you but the TikTok reposts tell a different story…

Ngāti Pāhauwera: Hangi rocks and a round marae, we get it, you’re a lowkey legend

Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki: Somehow you know everything about anything and everyone!

Ngāti Porou: When it’s time for a hākari everyone brings a plate of kai while you bring in a plate of opinions. Your staunchness can be intimidating, but at the end of the day you're always reliable to say what needs to be said.

Ngāi Tahu: The Capricorns of Māoridom, aka mahi dogs. It’s all good to take a break from your responsibilities every now and then – and there are plenty of tourist destinations where you are (and I know you can afford it �)

Te Āti Awa: Wellington landlords fear them, but they’re still waiting for their rent from the council

Yous wanna be different sooo bad with your double vowels and your ngēnei and whēnei and your Kīngitanga but it’s okay because He Aha Kei Taku Uma is one of the best iwi anthems.

Ngāti Awa: River people through and through, just don’t ask them to paddle in time.

1. David Seymour.

2. Kāore taku …

3. Matariki mā …

4. Te moutere tino iti o Te Whanganui a Tara.

5. Te atua o te nguha me te kāuta.

6. Kuini o THW me ngā pihikete.

7. Te parata o Ngake.

16. Te iwi tino whai rawa o Aotearoa.

17. Hūtukauhoe, �

18. Kupu whakarīrā mō ātaahua, �

19. He wīwī,

20. Tō hia … !

21. He kupu anō mō te kapa,

22. Te … o Te Reo Māori, rōpū.

8. I ahu mai a THW i whea? ��

9. Taku whare onamata, taku whare …

10. Kia mau ki ngā kupu …

11. Kahungunu … pāua.

12. Mai te awa ki te moana.

13. Tērā atu tekau.

14. He piko he taniwha, he piko he taniwha.

15. Te iwi tino nui rawa o Aotearoa.

23. He kupu anō mō Ngāti, NT. 24. … te taniwha.

25. He kupu anō mō te mauri.

26. Wheo …, �

27. Ko te … te whare o te whakaaro nui, �

28. … pants, �

29. a, e, i, o, u.

30. MAOR1113. Tērā atu tekau. (ngahuru)

Tukuna mai he kapunga oneone ki ahau he tangi maku

Send me a handful of soil so that I may weep over it.

E kore au e ngaro, he kākano i ruia mai i Rangiātea.

I will never be lost, for I am a seed sown in Rangiātea.

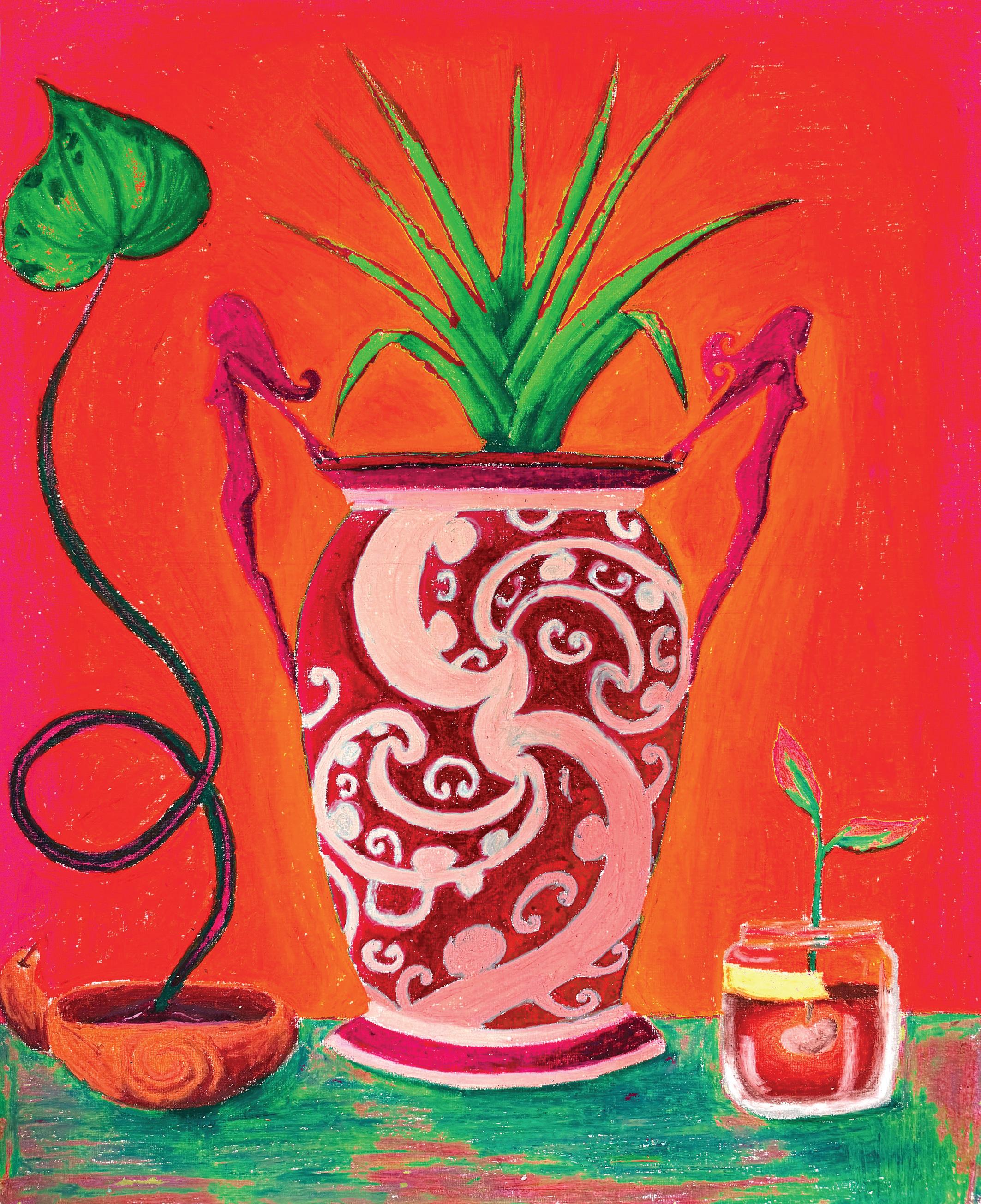

These two whakataukī best encapsulate the essence of the artwork I’ve created for the cover of Te Ao Mārama 2025. In alignment with this years kaupapa, Āhuru Mōwai (Safe place or haven), I consider the tauira Māori who are spending time away from their whenua and whanau to study.

The pot as a symbol is a multilayered reference often seen in Māori art today and throughout history. Through this work, I refer to carrying one’s land, urbanisation, displacement as well as symbolising home and Māori adaptation to new technologies. These are all realities of tauira Māori studying in a foreign environment away from home.

Whatever your safe place away from home is, whether it’s Te Taiao, A student association, the friends you’ve made, or a reminder of home, this piece is a reminder to nurture that pot of whenua.

Emily Lyall (Te Whakatōhea, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui)

I completed my Bachelor of Māori Visual Arts at Toioho ki Āpiti last year, where I learned traditional and contemporary Māori art theory and practice under Karangawai Marsh, Erena Arapere-Baker, Kura Te Waru Rewiri and Bob Jahnke. Not limited by any one style or medium, I create art I can speak to through lived experience and whakapapa. This year I have come to Te Herenga Waka to study a Masters in Museum and Heritage practice, hoping to get into Museum and Gallery art curation with a strong kaupapa Māori lens.

For more of my art & kōrero follow me on instagram @teaoemily <3

Kaea Hudson (Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Awa, Tūhoe)

Aria Ngarimu (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongomaiwahine, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui)

Taipari Taua (Muriwhenua, Ngāpuhi) - Kaiētita reo Māori

Manuhuia Bennett (Te Whānau a Hinetāpora o Porourangi, Ngā Pūmanawa e Waru o Te Arawa, Te Rohe Pōtae o Mōkai Pātea)

Emily Lyall (Te Whakatōhea, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui)

Sophia Soljak (Ngāti Uenukukōpako & Ngāti Raukawa)

Ataraira Cameron (Ngāti Ranginui, Waitaha-ā-Hei, Ngāti Rangiwewehi, Ngāti Hinerangi)

Nathaniel Cashell (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Toa, Ngāi Tahu)

Hannah Higgison (Ngāti Whātua)

Lewis Johnson (Rongomaiwahine, Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongowhakaata, Rangitāne, Ngāti Īnia)

Kaea Tibble (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Raukawa ki te Tonga)

Huia Whakapūmau Winiata (Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Toa Rangatira, Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāti Tūwharetoa)

Te Waikamihi Lambert (Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Ruapani, Tūhoe, Ngāpuhi)

Taipari Taua (Muriwhenua, Ngāpuhi)

Xanthe Banks ((Ngāti Rārua, Rangitāne, Ngāti Kuia, Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō)

Te Huihui o Matariki Chi Huy Tran (Te Kā'hui MaungaTaranaki Tūturu, Te iwi o Maruw'aranui, Te Āti Awa; Ngāti Maniapoto - Rereahu; Witināma, Tipete)

Manaia Barnes (Ngati Tūwharetoa ki Kawerau, Ngati Rangitihi, Te Arawa Whānui)

Manuhuia Bennett (Te Whānau a Hinetāpora o Porourangi, Ngā Pūmanawa e Waru o Te Arawa, Te Rohe Pōtae o Mōkai Pātea)

Nathaniel Cashell (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Toa, Ngāi Tahu)

Tamati Durie-McGrath (Ngāti Kauwhata, Ngāti Raukawa ki te Tonga, Rangitane, Ngāti Rangatahi)

Hannah Higgison (Ngāti Whātua)

Mana Puketapu Hokianga (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Ruapani, Ngāti Kahungunu, Te Ātiawa, Kāi Tahu)

Kaea Hudson (Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Awa, Tūhoe)

Lewis Johnson (Rongomaiwahine, Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongowhakaata, Rangitāne, Ngāti Īnia)

Shay McEwan (Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki, Ngāti Pāhauwera, Ngāti Porou)

Rēne Meihana (Kāti Kuia, Waikato-Tainui)

Amiria-Rose Monga (Ngāti Whātua, Te Uri o Hau, Cook Islands, Tahiti)

Aria Ngarimu (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongomaiwahine, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui)

Temepara Reihana (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu)

Kaleb Rongokea (Tūhoe, Ngāti Porou)

Sophia Soljak (Ngāti Uenukukōpako & Ngāti Raukawa)

Ruby Stuart (Whakatōhea, Tūhoe, Ngāti Porou)

Taipari Taua (Muriwhenua, Ngāpuhi)

Phaedra Chin (Te Rarawa, Te Aupōuri)

Amaia Watson (Ngāti Kahungunu ki Heretaunga)

Matagi Vitolio (Ngāi te Rangi, Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāti Pukenga, Ngā Pōtiki. Aleisa and Falefa of Upolu; Lelepa and Safune of Savai’i)