“Let all guests who arrive be received like Christ, for He is going to say, ‘I came as a guest, and you recieved me’ (Matt. 25:35).”

(The

Rule of St. Benedict, 53:1)

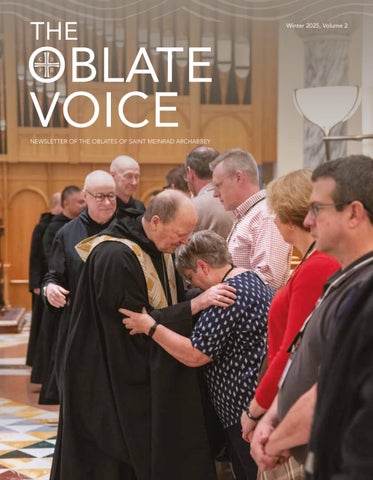

The Oblate Voice is published three times a year by Saint Meinrad Archabbey.

Editor: Krista Hall

Designer: Camryn Stemle

Oblate Director: Br. Michael Reyes, OSB

Oblate Chaplain: Fr. Joseph Cox, OSB

Content Editor: Diane Frances Walter

Send changes of address and comments to: The Editor, Development Office, Saint Meinrad Archabbey, 200 Hill Dr., St. Meinrad, IN 47577, 812-357-6817, fax 812-357-6325 or email oblates@saintmeinrad.org www.saintmeinrad.org ©2025, Saint Meinrad Archabbey

FR. HARRY HAGAN, OSB Monk of Saint Meinrad Archabbey

Some years ago, Dr. Carney Strange and I worked out a presentation that related Benedictine life to life on college campuses. My part in this little show began as a description of the Benedictine life and how it brings new people from exclusion to inclusion, from fascination to identification, and from dependence to belonging. For this, I focused on six distinguishing features of monasticism. In the language of Benedict, these six hallmarks of community are as follows: regula et traditio, stabilitas, conversation, obedientia, ora et labora, and hospitalitas.

Regula et traditio

The list begins with regula et traditio. The Rule of St. Benedict is a written document, and most communities have a written statement that defines their identity and purpose and order. Nations have constitutions. Religions have scriptures. Many institutions today have mission statements. The written document typically defines the core values and processes for the group. The tradition is the living memory of how the written document has been interpreted and adapted over time to different situations. Often the tradition is captured by stories. Both the written document and the living memory are needed for the ongoing life of a community. One can neither understand nor create a monastic community only by reading The Rule, the written document. Every book needs a community of interpreters to understand and live the written text. Without a text, a community is left to the whim of the present. Both the written text and the tradition embodied in a living community are necessary.

The next three marks are simply the vows which the novice takes: stabilitas, conversation, and obedientia.

Stabilitas we defined as commitment to a particular community. Monasticism is not just a commitment to a way of life, but to a way of life in a particular monastery: to the place, to the people, to its tradition and culture. Stability is sometimes presented as a state of mind, but we have emphasized the importance of stability in the concrete and literal sense. A person identifies with the particular community by participating in its common life: that is, its common prayer, its common table, its community work, one’s service to the community, and its common recreation. Other common elements can contribute to this identification, such as common dress, a special monastic vocabulary (e.g., refectory, choir, prioress), the delineation of spaces (e.g., cloister), as well as schedule and rank. The Rule also calls us to certain community virtues such as the precedence of the common good, respect and love for the individual, and care of the sick. There are community sins as well: anger, murmuration (complaining), and acedia (that is, the temptation to abandon the commitment). Finally Benedict creates an elaborate system for the correction of faults. While few monasteries follow his processes exactly; still every community must have some way of acknowledging faults and reconciling members. For individuals to be stable members of a community, they must be able to support with the greatest patience one another’s weaknesses of body or behavior.

Conversation has been a hot topic among scholars who have been anxious to distinguish it from conversio = conversion. The Rule of St. Benedict 1980 translates the term as “fidelity to the monastic way of life.” However, in our presentation we have contrasted conversation with stabilitas and emphasized the sense of change and becoming which lies at the root of the word convertere which means “to turn,” “to turn with.” If stabilitas means standing still, conversation is about movement and change, about becoming, about giving oneself more and more to the monastic vocation. We point to humility as the foundation of change because humility is the ability to acknowledge and face the truth about oneself and the truth about others. By doing so, one is able to climb the way of humility which leads to that love which casts out fear. The other side of changing oneself is letting others change. Too often we need others to remain as they are, and so we become obstacles to their changing.

Like humility, obedientia, the third vow, is a dangerous but necessary virtue. It is dangerous because it can be easily misused to manipulate others. It is necessary because obedientia is grounded in listening, and we must listen to know whether we should stand still or change. The relationship between listening and obedience transcends cultures. In Hebrew the word šamac can mean both “hear” and “obey.” In Latin obedientia has its root in hearing: ob+audire. Obedience is not just passive listening. If you truly listen, then you will know how to respond. To obey is to respond to

what one hears. The sense of autonomy in our culture makes this virtue difficult, yet there is no real learning without obedience and humility. In The Rule of St. Benedict, these virtues are bound up particularly with the master and disciple relationship. The Rule calls for the disciple to give the self over to the magister, to the Teacher: the abba or amma. The gift of the self becomes possible because of what Benedict demands of the Teacher. To my mind the genius of The Rule shows itself most clearly in Chapter 64 on the qualities of this Teacher. I would call him a wisdom figure. Benedict’s prescriptions point to a person of discretion who holds together both justice and mercy, and if necessary, grants precedence to mercy. The vertical relationship of master and disciple is not the only demand for obedientia. Chapter 71 calls for mutual obedience which is perhaps more difficult.

Ora et labora

For our fifth hallmark, we take the great Benedictine motto “Ora et labora.” Perhaps in another context one would hold up prayer, particularly liturgical prayer, as a value in and of itself. We have used the motto to stress the unity of life. The motto does not present two discreet things but holds prayer and work together. The chapel becomes the place for the Work of God (Opus Dei), but the work of God does not end at the chapel door. God continues to work where we work. The monastic cell is

the place of solitude, but this is not a refuge from the common life. There must be time and place for both. For the individual there must be a unity of the inner life and the outer life. As Psalm 19 says: “May the spoken words of my mouth [the outside] and the thoughts of my heart [the inside] win favor in your sight, O Lord.”

A favorite quote from John Cassian also speaks powerfully to this integration of ones life:

“When all love, all desire, all zeal, all impulse, our every thought, all that we live, that we speak, that we breathe, will be God, then that unity the Father now has with the Son and the Son with the Father will fill our feelings and our understanding.

“Just as God has loved us with a sincere and pure and unbreakable love, so may we also be joined to God with an unending and inseparable love.

“Then we shall be united to this same God in such a way that whatever we breathe, whatever we think, whatever we speak may be God” (Conferences, 10.7.2).

Our final hallmark is hospitalitas Benedict identifies three groups with Christ: the Abbot, the sick, and the guests. In my opinion he does this because all three are trouble. Everyone knows that a superior is trouble. So Benedict calls them Christ. Moreover,

these people must be taken care of. The sick are unable to do it for themselves, and so their demands are constant. Guests come at odd hours with their expectations for food and sleep. The Master in his rule is very leery of these travelers as he is of the sick, but Benedict demands vulnerability to these wayfarers who come as Christ because they are in need of service. Hospitalitas means taking care of others.

However, the guests also bring something. They bring the outside world; they bring a different experience and perspective. They bring critique. Such inward-looking communities as monasteries can insulate themselves from critique, yet this is the gift of the guests. They bring the possibility of newness just as the junior member of the chapter may bring insight (quia saepe juniori Dominus revelat quod melius est) Hospitalitas is the opposite of defensiveness. It is openness and vulnerability—openness to Christ who was nailed to a cross.

To begin the monastic life, one need not achieve all of these hallmarks, for this way is a way of conversation, a way of continuing to seek God. To begin, one must only commit to the project as part of a particular community, but to commit is to give oneself.

As Br. James Meyer told us in our novitiate retreat: We don’t expect you to turn thorns into roses in just one year. We’re just looking for a little better grade of thistle.

Editor’s note: Signals in the Noise is a column for oblates trying to tune into God’s presence amid the stress of everyday life

There’s an old saying that if you drop a frog in a kettle of boiling water, it will immediately jump out. However, if you place that frog in a kettle of lukewarm water and slowly turn up the heat, you’ll cook it.

Like most old sayings, this isn’t actually true. Yet, as a metaphor, it offers a powerful truth.

You and I are the frogs. Our lives are the kettle of water. Stress, anxiety, and busyness are the heat.

As I write this, I’m home recovering from a bout of illness that hit me after weeks of a high intensity elixir of work, travel, and family commitments that offered me zero rest and recovery time. During all this running around, we had our laundry dryer, refrigerator, and oven all break down within a 48-hour period on the eve of hosting students from Kenya that we sponsor.

All this busyness and stress doesn’t seem unique to me and my family though. It seems everyone is feeling an escalated sense of pressure.

My retired parents run themselves ragged trying to be “good grandparents.” My colleagues at work are spending more time in meetings complaining about their workload and unmanageable schedules. Even at the oblate retreat in March, I heard stories from multiple people who were dealing with major life changes or carrying heavy burdens.

Each time I’m on Saint Meinrad’s campus, I notice that this drumbeat of busyness isn’t unique to the laity. I see the monks rushing about as they juggle competing duties and obligations on

“the Hill,” as well as out in the parishes.

As long as humans have walked the earth, we’ve stayed busy “going out and coming in.” This is a phrase that shows up throughout the Old and New Testaments. Check out 2 Kings 19, 2 Chronicles 16, Psalm 121, Isaiah 37, Joshua 3, 2 Samuel 3, and Mark 6.

I can’t help but think of another old saying: “If the devil can’t make you sin, he’ll make you busy.”

I believe all this busyness offers you and I, as Benedictine oblates, a unique opportunity to love and serve our neighbors. It seems that a lot of the busyness we’re seeing around us (and in us) is a symptom of loneliness. After all, busyness leads to isolation, and isolation leads to disconnection and feelings of otherness.

The U.S. Surgeon General reports that we have a “loneliness epidemic” in the U.S. According to a recent survey by the American Psychiatric Association, one in three Americans feel lonely every week. Young people and adults over the age of 60 are experiencing this at even higher rates.

Chapter 1 of The Rule of St. Benedict tells us of four kinds of monks. Cenobites are what most of us imagine when we hear “monk” or “nun.” They live, pray, and work together in community under a rule and abbot. Anchorites are the hermits. Sarabaites and Gyrovagues are the posers and drifters.

St. Benedict’s legacy lies in the breakthrough value he placed on community. Our promises of stability, fidelity, and obedience are the nutrients

that bear the fruit of a thriving community. I like to think of these as sticking together, growing together, and sacrificing together. These are what most people today are longing for.

Community is what our families, workplaces, local churches, and Saint Meinrad offer us. However, many people don’t have this. And many that do are still struggling with loneliness. Why?

There are four dimensions of loneliness. The first is physical loneliness. This comes from physical separation from others such as being homebound or incarcerated. The second dimension is emotional loneliness. Examples of this are not feeling safe, worthy, or autonomous. The third dimension is social loneliness, which happens to those who don’t feel welcome or included. The fourth dimension is spiritual loneliness. This is a feeling of separation from God and a higher purpose.

As oblates, you and I are Saint Meinrad in the world. We have a unique opportunity to be a bridge to those hiding their loneliness behind the façade of busyness. Like bringing water to a desert, we have daily opportunities to connect with those who long to be seen, heard, included, and loved.

Despite some sickness and the expense of dealing with failing home appliances, my wife and I have tried to keep a sense of humor and perspective. Our recent “problems” were problems of privilege. There are people facing real problems.

A friend of my wife discovered her husband was living a double life. She’s in the middle of a divorce and has had

to scramble to find a job that can cover her family’s expenses. You would never know this if you met her, but privately she’s lonely and burned out as she’s trying to care for her kids through this deep wound.

A young couple I married recently learned they can’t have biological children. You would never know what they’re going through if you met them, but they are privately grieving.

These are two examples of what’s going on in the lives of people we think we know. People appear to have it all together but are privately being cooked in the kettle of life.

If you and I are slowly cooking in our own kettles, how can we bring the peace of Christ to our family, friends, colleagues, and neighbors? How can we be Saint Meinrad in the world?

As oblates, we have something very special to offer. It’s a way of life many people are longing and searching for. As Jesus says in Matthew 9:37: “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few.”

Let’s hop out of the kettle of busyness and into the kettles of others. Let’s practice true community.

FR. JOSEPH COX, OSB Monk of Saint Meinrad Archabbey

The Gospels tell us that a scribe asked Jesus which commandment is the most important of all. Jesus said that the most important is to love the Lord our God with all our heart and all our soul and with all our mind and strength. And the second is to love our neighbor as ourselves. Jesus said that there is no other commandment greater than these. He answered the scribe concerning the greatest commandment but added that we must love others and love them as ourselves. The Lord tells us that we are interrelated – love of God, love of ourselves, and love of our brothers and sisters.

Sometimes we forget that we are to love ourselves. We are not to love ourselves in a disordered way, but with healthy self-esteem that avoids extremes. An overly high self-esteem may be “egotism” in which we have an excessive interest in ourselves, and

we become arrogant and disrespectful of others. At the other end of the spectrum would be an overly low selfesteem in which, due to our low opinion of ourselves, we can be too docile and compliant.

If we have healthy self-esteem, then we are better able to esteem others, but if we are down on ourselves, we tend to transmit our pain to those around us. In his book, New Seeds of Contemplation, Thomas Merton wrote, “The search for true identity requires an honest self-love. Love of self is not selfishness but a humble recognition of our lives as true, good, and beautiful. Without real love of self, all other loves are distorted. Lack of self-knowledge, St. Bonaventure once wrote, makes for faulty knowledge in all other matters.”

Everyone is made in the image and likeness of God. All people have

inherent human dignity from conception to death, and human life must be valued above material possessions. In a mysterious way, God dwells in every human being, so the way that we treat others is the way we treat the Lord. To accept this is to be humble.

Chapter 7 of The Rule of St. Benedict concerns humility. Humility is truth—truth about us. To be humble is to recognize that we have good points as well as negative points. The opposite of “humility” is “pride.”

Pride is falsehood, and this surfaces when we see only our positive qualities, but never address our negative qualities. To be humble is to know our place in the universe as well as our connectedness with and dependence on God and our brothers and sisters. We are definitely not individual islands. We need God and others in order to be complete, whole, loving human beings.

Homily for the Thirtieth Sunday in Ordinary Time (B)

First Reading: Jeremiah 31:7-9

Responsorial Psalm: Psalm 126:1-2, 2-3, 4-5, 6

Second Reading: Hebrews 5:1-6

Gospel: Mark 10:46-52

I will gather them from the ends of the world, / with the blind and the lame in their midst, / the mothers and those with child; … / I will console them and guide them; / I will lead them to brooks of water, / on a level road, so that none shall stumble.

Jeremiah was a prophet in Judea at a time of great upheaval and devastation. He lived in Jerusalem where he served as a priest in the temple. Jeremiah had also been called by God to be a prophet, and as prophets often are, he was a thorn-in-the-side of the king and his supporters. It was a frightening time to live in Jerusalem. The kingdom of Babylon had become powerful and was threatening to conquer the land of Judea and destroy its capital city, Jerusalem. The king of Judea resisted Babylon, but to no avail, and the Babylonian army was at the gates, besieging the city all around—cutting Jerusalem off from its sources of supply, especially food.

Jeremiah believed this horrific plight was God’s wrath resulting from the king’s, and by extension the people’s, lack of faith in God. So, the city fell and the temple, that magnificent House of God built by King Solomon, was destroyed!

Toward the end of his life—having fled into exile in Egypt of all places— Jeremiah proclaims a message of hope.

He reminds the people that though Babylon had conquered their land, captured their royal city, and destroyed the Temple of God, taking the priests and politicians, the royal family and the king himself into exile in Babylon, that despite all of this, God remains faithful.

Over in Babylon, another priest and great prophet, Ezekiel, was proclaiming a similar message, saying that no matter what happens, no matter how devastating things seem to be or are, God is with us, God remains faithful, but we must rely on our faith to believe it.

It’s interesting—Faith—how does it work do you suppose? To some extent it’s a mystery, and as such it eludes our comprehension. In today’s Gospel we read that Jesus performs a miracle and a blind man can now see, but he doesn’t claim, “I did this for you, Bartimaeus,” or even that “God did this for you,” but instead Jesus says, “Your faith has healed you!”

There is something about faith that Jesus wants us to understand.

Sometimes I get frustrated. I live in a community of 70 men representing every adult generation from Gen Z to the Silent Generation—our ages range from 26 to 96. Community teaches us what love demands, and when I get frustrated by what others do, by standards of cleanliness or neatness which are sometimes quite different than mine, or whenever I’m annoyed by idiosyncratic tendencies in others, or frankly, the laziness I see in some, and in myself, all of that rubbing elbows and living in community can lead to frustration when one is trying to be kind, trying to be generous, trying to be compassionate and forgiving, but

failing so often—if not outwardly then at least in my heart. Charity is not a soft virtue!

Guests and retreatants who come to Saint Meinrad will sometimes ask me, “What do monks do all day?” I usually begin my answer with, “We fall down, and we get up, several times a day, every day, for the rest of our lives.” We fall down, and we get back up.

We all know—I hope—that none of us are flawless. But also, I hope, we know that God loves us just as we are right now. God’s love is not determined by what kind of person I’d rather be; God doesn’t wait until I’m flawless and perfect before God loves me. And that’s a matter of faith because most of the time I don’t feel worthy of that love.

Jeremiah proclaims that God will bring back from the land of exile, indeed from the ends of the earth, an immense throng: “I will gather them from the ends of the world, / with the blind and the lame in their midst, / the mothers and those with child; … / They departed in tears, / but I will console them and guide them; … on a level road, so that none shall stumble.”

The good news from Jeremiah is that God himself is doing this for us, and not just for the strong and the virtuous, but for the vulnerable and weak too: mothers with their kids and pregnant women, the most vulnerable members of society, as well as those with physical debilitations, whether blindness or other bodily disabilities, and those who suffer the horrors of social upheaval, refugees in exile, having fled their homes for their children’s sake. It is I, says the Lord, who will console them and shepherd them, providing a level road so that none may stumble!

Jesus is, of course, the fulfillment of this prophecy. Jesus is God, our Good Shepherd, who leads us to brooks of living water, and who guides us in the way of the Gospel—a level road that leads us home, a place prepared for us from the beginning.

But it’s not enough to realize we need God’s grace and mercy. We have to do what Bartimaeus did and call out to Jesus as he comes near, who is always readily available if we’d only call out and mean it: O God, come to my assistance, Lord, make haste to help me!

Bartimaeus—that’s an interesting name. The Gospel notes his name as meaning “Son of Timaeus.” The prefix bar is from the Jewish language, Aramaic, meaning ‘son of.’ Timaeus is Greek, meaning honored. It’s possible that St. Mark, writing to a community of mixed Jewish and Gentile converts, used this name to point to what Jesus was doing beyond the physical miracle of healing—uniting what is divided, gathering what is scattered.

Jesus honors Bartimaeus by using his condition to glorify God. The faith Bartimaeus expresses through his persistent calling out to Jesus while refusing to allow others to silence him is the precondition for his access to God’s creative, healing power—a power that makes all things new!

Bartimaeus literally actualizes his faith by acting on what he had come to believe about Jesus: that Jesus was sent by God to fulfill God’s promises to gather in what has been scattered, to find the lost and bind up the lame, and that included people like Bartimaeus … and like me, and like you.

Faith is the gift given to us at baptism to believe in Jesus and to trust in God’s word... “

But the name Timaeus also sounds like the Hebrew word ta’mey, which means “defiled” or “impure.” The Jews of Jesus’s day generally believed that any kind of ailment or disability was a sign of being unclean, a sinner in God’s eyes. But in another Gospel, Jesus heals a man born blind, and his disciples ask him, “Master, who sinned? Was it this man or his parents?” Implying that God was punishing his parents by giving them a child who was blind from birth.

Jesus says in that Gospel what he could have said to his disciples, “It is for God’s glory, so please, stop trying to silence the one I choose to honor and call him over!”

All kinds of people suffer all kinds of flaws and debilitations, whether physical ones like Bartimaeus, or psychological ones, whether emotional or moral frailties, people with unwholesome beliefs and prejudicial attitudes, unhealthy habits and addictions, people boxed in by fear and anxiety or are blinded by plain ignorance. All of us need God’s mercy and God’s love, and faith is our access to it.

Faith is the gift given to us at baptism that empowers us to believe in Jesus and to trust God’s word made flesh as God’s presence dwelling within us and among us; that Christ is the one sent by God to gather what has been

scattered, to find the lost, to bind up the lame, to comfort the sorrowing. Bartimaeus’s faith not only restored his vision, but it made him a disciple, willing to follow Jesus on the way.

Though faith and its workings are mysterious, eluding our ability to fully comprehend it, it isn’t “magic” either. Faith is like spiritual musculature, it must be exercised to get strong and resilient, to be able to support us in times of loss or hardship, to see us through experiences of personal tribulation and social upheaval.

Last evening I had Mass at St. Anthony of Padua parish in Clarksville after which I gave a talk on prayer. I told the parishioners that prayer is like a weight room for faith—without regular and consistent prayer, we cannot expect to know God beyond what we claim to know about God— which, frankly, given the infinitude of God, isn’t much. Prayer is what we do under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit to consent to what God is doing in us—to shape us from within by conforming us to Christ. Prayer is also our consent to what God wants to do through us and as us—as one body, one spirit in Christ—for others.

So, let’s celebrate the Holy Eucharist as an act of Christian faith in all that God has in fact already accomplished through his Son Jesus, providing for us an even road, a reliable way that leads to a homeland where every person made by God and for God no matter their human limitations, frailties, or wounds, will enjoy the fullness of God’s love.

Look to Bartimaeus as an example of the faith you have in Christ and exercise that faith to rely on God’s care for you, and you will enjoy, even today, the grace of a new vision, Christ’s vision, and a renewed resolve to follow Jesus in the way that leads to life.

MICHAEL REYES, OSB Monk of Saint Meinrad Archabbey and Oblate Director

Editor’s note: This is the second article in a three-part series.

The vow of fidelity to the monastic lifestyle is not just a commitment, but a profound and transformative journey. It sets Benedictine monastics apart from the world, guiding them through the monastery’s rich traditions and reflecting the image of Christ. This sacred calling is an inspiring voyage that nurtures spiritual growth and deepens one’s connection to the divine, a journey that can inspire and motivate all who hear of it.

Oblates, those who cherish the monastic life while living outside its confines, honor the essence of this unique path. They strive to cultivate their lives in the likeness of Christ, weaving monastic values into their daily commitments. The Rule of St. Benedict exhorts them to “never stray from [God’s] guidelines, but faithfully observe his teachings ... until death, [so that they] may, through patience share in the sufferings of Christ and also merit a share in his kingdom” (RB Pro. 50).

The Rule of St. Benedict beautifully guides this journey, illustrating monastic life as a pathway to Christ. Within this vision, we encounter three powerful images: a school dedicated to the Lord’s service, the inherent “hardships and difficulties” of monastic life, and the concept of good zeal. Monks and oblates can embark on a more prosperous, more fulfilling journey toward encountering Christ by exploring these principles.

As the Prologue concludes, St. Benedict expresses his noble aspiration “to create a school of the Lord’s service” (RB Pro. 45). This notion of a “school” invites profound contemplation. For St. Benedict, the concept of a “school” was not limited to conventional education. It was a trade guild, where individuals become apprentices, mastering essential spiritual skills practiced throughout their lives. In this enlightening framework, no one truly “graduates” from the “school of the Lord’s service.” Instead, it embodies a continuous lifelong learning journey characterized by applying lessons learned and growth through shared experiences, ensuring ongoing engagement in spiritual development.

Chapter 4 of The Rule lays out vital tools for this sacred trade: foremost, the love of God and our neighbor, heartfelt assistance to those in distress, comfort for the sorrowful, diligent avoidance of grudges, mindful eating habits, steering clear of laziness, commitment to regular prayer, daily reflection on our conscience, honoring chastity, and steadfast hope in God’s boundless mercy. These principles unite us in our aspiration to resemble Christ, fostering a deep spiritual connection that binds us in the community.

Another impactful image from The Rule emerges in Chapter 58, where St. Benedict states, “The novice should be

informed about all the hardships and difficulties that will lead him to God” (RB 58.8). This phrase refers to “the hard and bitter things” that guide us toward the divine. Such guidance embodies faithful living according to The Rule. St. Benedict reassures us that even our most significant challenges can deepen our experience of divine love, reminding us that our struggles are integral to spiritual development. Recognizing God’s presence amid trials affirms a novice’s genuine desire for God, allowing them to become a valued member of the “guild” within the school of the Lord’s service.

Our lives weave a tapestry of suffering and joy, and by recognizing our hardships, we cultivate compassion for those facing different struggles. The universal theme of perseverance through suffering often unites us in our collective journey toward God. The joy in this path lies not just in seeking our own healing, but also in offering support to others during their trials, fostering a deep sense of connection and empathy.

When confronted with challenges, where do we find comfort and solace? Fidelity to the monastic way of life offers profound wisdom. The Prologue reminds us to resist being “overwhelmed by fear and flee from the path that leads to salvation” (RB Pro. 48). Embrace this journey, for it shapes our spiritual lives in extraordinary ways.

Editor’s note: This is the second article in a five-part series. This article is adapted from “Four Kinds of Monks: four obstacles to seeking God,” originally published in American Benedictine Review (Sept. 1994), pp. 303-320. I thank the editor, Fr. Terrence Kardong, OSB, for his kind permission to make my reflections available to our oblates.

The Gyrovagues: Let nothing be preferred to ... doing nothing.

St. Benedict describes this second kind of “bad monk” succinctly: “[T]here are the monks called gyrovagues, who spend their entire lives drifting from region to region, staying as guests for three or four days in different monasteries. Always on the move, they never settle down and are slaves to their own wills and gross appetites. In every way they are worse than sarabaites” (RB 1:10-11).

Monastic humor has it that were The Rule to undergo editing at the hands of a 21st-century scribe, Benedict’s dictum “Let nothing be preferred to the work of God” would reappear as “Let nothing be preferred to a trip.” Such is contemporary reflection on the vice of the gyrovague! But underlying the humor is a bit of truth. For the tendency of the gyrovagues is that they are always on the go. And if they are not on the go outside their monasteries, they are very much on the go within them—or more precisely, they are constantly on the go within themselves.

The gyrovagues do indeed live for tomorrow, but in a way unlike that recommended by the Gospel. “Always on the move, they never settle down and are slaves to their own wills and gross appetites” (RB 1:11). Always interested in the future commitments they know they should make, theirs is the folly of the five foolish virgins (Mt 25:1-13). Or perhaps they are more

foolish. For, unlike the foolish virgins in the Gospel, gyrovagues seldom get to the point where they actually go out and get some oil: it’s too late in the day, the roads are too bumpy, the traffic is too bad, and there’s bound to be a cut-rate sale on lamp oil next month. Gyrovagues do not live for the future; they live thinking about the future, a future that, sadly, never seems to have much influence on the way they live now.

It is this thinking about the future, yet seldom getting around to actually settling down in the present, that is the tendency of the gyrovague that may linger within us, as we periodically find our spiritual momentum decelerating into nearinertia. The young monk believes he will find it easier to do lectio next week once he’s no longer assigned to that time-consuming afternoon task of cleaning the refectory. The seasoned professor will make every effort to renew her spiritual life as soon as this block of lectures is finished—or, certainly, when the semester is over and done with.

And then there are those assignments or responsibilities not redeemed by the illusory grace of a semester’s end: the maintenance and repair of the community’s house and material possessions, the preparation of meals, the care of the sick, the washing and mending of clothes, the administration of the monastery, the recruitment of candidates, the raising and disbursement of funds. All these responsibilities are necessary and

noble, for they allow the community to receive what it needs and to provide its service to God and to others. But it is always something to do, some item to produce, someone to take care of— and it is always a far cry from closing the doors of our cells and opening the Scriptures for ourselves, or simply listening more intently to the voice within us, without having to “take notes.”

The orientation of the gyrovagues, then, is always and only to tend toward doing those things they know they have to do. But becoming a monk requires following through on the implications of that basic vow of conversatio morum that guides our whole life. That vow, which presumes that our fundamental task is that of seeking God, requires action as well as contemplation; it necessarily demands that each day we reflect and then act upon what in our lives we must foster and encourage, on the one hand, and, on the other, what we must set aside or abandon. Excuses are understandable, but they do not justify; preoccupations can distract, but they should not determine. The Gospel does observe that we will always have poor who are to be served or dead who must be buried; that same Gospel, however, is quite insistent about not turning around once we have put our hands to the plow.

Dom Philip Jebb describes that continual wavering of the gyrovague within us in a way that is most familiar:

“There is a definite temptation to put off for the time being the fulfillment of the vow of Conversio Morum, to get simply carried along by the tide of activity and to leave until retirement the pursuit of monastic perfection. Then as I return quietly to my desired haven in the archivist’s office, I shall be able to attend to the things of God, spend more time and energy on prayer, prayerful reading, meditation, preaching, and writing ...

“I believe that in their essentials and in a lot of their details, the circumstances of my present life are those positively willed by God (some of them, of course, are the result of my own errors) and that in this great whirlwind of activity and distraction is to be found my Desert, my calling. I can find plenty of examples of monks from St. Gregory the Great to John Bede Polding to encourage me in the belief that sanctity can be found in the mess I am now in, rather than in the

chimera of tomorrow’s imagined peace.”1

While Benedict saw the gyrovagues of his day as those “who spend their entire lives drifting from [monastery to monastery]” (RB 1:10), the tendency of the gyrovague that may afflict us from time to time is our drifting from novitiate to profession, or from anniversary to anniversary, and never settling down as regards the practical decisions we must make and the steps we must take to direct and maintain our search for God. For our vow of stability is only symbolized when we move into the monastery and set up shop: we find stability ultimately not in our monasteries, but in our cells and within ourselves.

The gyrovague within us would have us wait for the right time, the perfect time, the time when all distractions and duties cease, the time when there finally is time to devote ourselves

wholeheartedly to the God whom we seek. The problem, of course, is that when that time comes, for most of us it will be on the far side of death—a poor time indeed to find ourselves with a dwindling supply of oil or a lamp that is flickering but dimly.

Simple procrastination as regards the oil of our spiritual life is the tendency of the gyrovague within us. While the tendency of the sarabaite encourages us to define and live our monastic vows and commitments on our own terms, that of the gyrovague hastens to remind us that there is no haste, that there is no hurry. The sarabaite prays, “Not your will, but mine be done,” while the gyrovague confidently chants, “Come not yet, Lord Jesus; please, please, do delay.”

In the third article in this series, the “good kinds of monks” will be discussed.

BR. JOHN MARK FALKENHAIN, OSB Monk of Saint Meinrad Archabbey

Conversion is the goal of monastic life. Often, we hear that the goal of the monk is to “seek God,” but if we spend any time exploring the contemplative dimension of our monastic calling—and we cannot call ourselves “monastic” without paying heed to the contemplative call—then we quickly understand that these two ends, conversion and seeking God, are one and the same.

Martin Laird, in his book on contemplative practice, describes contemplation as an opening of ourselves to the sacred within. Thomas Merton describes contemplation in relationship terms when he describes meditation or contemplation as “a way of keeping oneself in the presence of God and of reality, roots in one’s own inner truth.”

In other words, to be contemplative means to seek God by turning inward and cultivating our relationship with Christ, who dwells at the very center of our being. It is a turning (a returning) to our original, best selves—to the person God has created us to be and whom we reinforce each time we consume the body of Christ in the Eucharist—a person in full communion with him. The monastic or the contemplative life, then, is about growing in our capacity for intimacy in our relationship with God. This is conversion.

Relationships—and it is particularly true of our relationship with God— are dynamic and they demand change. I see plenty of young couples in my psychological practice who three years into their marriage encounter a significant crisis. They discover a great difference in their points of view,

violate one another’s trust, or grow bored. A great argument ensues, and the question follows: perhaps we are no longer meant to be married.

Now, if the goal of the couple is to live the entirety of their married life in the same state of simple bliss that they had in the first three years, then it is probable that these two were never meant to marry in the first place. For, more than sources of peaceful bliss, committed relationships—marriages, monastic vows, deep friendships—are meant to be crucibles—loving crucibles, but crucibles no less—for our conversion.

I tell young couples that depending on their view of marriage, these crises are the meat of their relationship. Such times call for each member to change: to move outside one’s comfort zone, to give up the idea of living “like it has always been,” to die a little to self and to give in to the interest of the other—in other words, to love. In “laying down our life”—our preferences, our hopes, our time, our expectations—for the other, we grow in our likeness to Christ. We enter into conversion.

And so, it is in our relationship with God. We must be willing to abandon our will and our expectations of him, so that we might be free to see what he reveals of himself and of his plans for us. I once read somewhere that the biggest barrier to our future prayer life is our current one—the one we know has worked.

John Cassian, one of the early Church Fathers, similarly points out that in seeking God, the monk must ultimately be willing to renounce what he already knows of God, his current

image of God. The idea is radical but true: that to grow deeper in our knowledge of intimacy with God, we must be willing to let go of our expectations of him. If we limit God to what we already know of him, then we shut ourselves out from perceiving any more of the mystery he cares to reveal to us.

Art is another potential relationship in our lives that has the capacity both to comfort us and to push us out of our comfort zone. Art can equally confirm what we already know or challenge us to see things differently—God, our faith, our experiences, who we are.

Understandably, when it comes to the visual arts or music, even movies, we tend to gravitate toward things we know we like. But if we keep returning to the familiar, the comfortable, rejecting experiences we don’t understand or find challenging, then we risk missing out on a point of view that might have deepened our understanding or shed new light on the mysteries of our life and faith.

I love lush choral music and rich, melodious orchestral pieces. I prefer the peaceful, lyrical beauty of Fauré’s or Rutter’s “Requiem.” Each time I try listening to Verdi’s or Brahms’s “Requiem,” I give up, thinking, “It’s easy to switch discs, so I pop the Fauré disc back in and find myself replacing once more to the comforting, serene beauty of Fauré. But then I have passed up an opportunity to grow, haven’t I?

I am not suggesting that we go about exposing ourselves to just anything, trying to convince ourselves that

everything is good and a potential source of growth for us. There are genuinely harmful images and words and experiences out there. Still, when confronted with what is generally recognized as a great composition or painting, an enduring piece of literature or a revered work of religious art, the desire to turn away if it is not to our immediate liking might also be a call to grow deeper in our understanding of who we are, our life, God, or faith.

Let’s take for example Grünewald’s painting of “The Crucifixion,” the central panel of the Idenseim Altarpiece (you can look it up on the Internet). While it is probably not something you will want to hang above your living room sofa, it is widely recognized as a great work of religious art. It is not beautiful, in fact, it is difficult to look at—Christ’s skin is pocked, his lips are ashen, his hands are gnarled in pain, and his feet are bloody and gangrenous.

nonetheless to join in the passion of Christ? Is that what John the Baptist is saying as he stands to the right pointing at Christ with the Lamb of God at his feet: salvation through suffering? This must have made sense to the patients at the hospital where this painting originally hung. What sense can it make of our suffering— great or small?

Great works of art, like Scripture and great pieces of sacred literature, are to be read slowly, studied and digested over time. We might approach them in the same way we approach lectio divina, opening ourselves to what is

... they are to practice Their craft with all humility, but only with The abbot’s permission. “

Br. Martin Erspamer, OSB, an artist in our community, often says, “We are formed by our surroundings. If we surround ourselves with challenging, meaningful, and beautiful works of art, then we are formed in the truths these offer. If we surround ourselves with mediocrity or ugliness, we are formed in the values that these present to us.”

Most of us do not consider ourselves artists. All the same, many of us dabble in some sort of art or craft: playing an instrument, singing in a chorus, photography, sewing, quilting, gardening, woodworking. To raise children is an art, as is keeping a house, maintaining a car, or growing vegetables.

Our initial reaction is to turn away immediately. But if we stay with it (here is a lesson in stability!) and ask ourselves certain questions, maybe even read a little about it, the painting offers us a new perspective on Christ and our relationship with him. For example, what is it about the painting that I find so difficult to look at? What is it about me that I want to avoid a painting like this one? Am I uncomfortable with suffering? Do I prefer to believe that Christ did not suffer as much as it appears here?

And look at Mary, St. John, and Mary Magdalene (whose hands look like Christ’s). Their bodies are twisted in such a way that they look both repelled by and drawn to Christ in his suffering. Is Grünewald trying to suggest that, despite our aversion to pain and suffering, we are called

on the canvas or on the recording, deciding who we identify with in the painting, exploring how composition appeals to our affect and our intellect. How are we challenged? How are we comforted? How am I different than I was before I looked at this? What conversion has taken place as a result of exposing myself to this?

Monasteries have traditionally been great patrons and holders of art. Our corridors are lined with art, and most monks have copies of favorite paintings in their cells. Monasteries typically have great musical traditions, and one often finds voracious readers and serious writers in Benedictine communities. This should come as no surprise when we consider the capacity of art to challenge us to conversion.

One of the great benefits of practicing an art or a craft of some kind is the personal conversion that accompanies the discipline. Practicing art brings us face to face with our limitations. One of the great challenges and lessons in humility is balancing our desire to be better at our craft (be it parenting or painting) while accepting the good we have already achieved.

How difficult it is to simply say “thank you” when someone compliments us on a job we knew we could do better. Commitment to art or craft provides a perfect metaphor for the spiritual life: striving for perfection while accepting our limitations.

I like to say that any time we commit ourselves to learning a new discipline or craft, we learn once more the important lessons of life and faith: the importance of patience, the futility of perfectionism, the dangers of comparison, the importance of asking for help, and the joy of eventually helping others.

When learning to paint or write or play the cello, we are frequently frustrated with our inability to make something look or sound like we want it to. The difference between what we imagine we should be able to do and what we actually produce frustrates and embarrasses us. It is our poverty, and like the widow in the Gospel, we grow in holiness when we learn to accept our limitations and give out of our poverty, rather than grow miserable and miserly because our neighbor is able to give more or paint better or play the cello more beautifully.

Like contemplation, practicing an art takes time, patience, discipline, and daily dedication. These pursuits are rarely gratifying at first; but after years of practice, we begin to experience the fruits of our discipline. These include a certain freedom and joy that flow out of relating to creation or the Creator.

We become freer in expressing ourselves, singing out loud, enjoying what we have created, or reveling in our achievements. We abandon ourselves and rejoice in the experience until, of course we hold on to these achievements too tightly, and our artistry is crippled by the attachment to our accomplishments and our comfort zone.

My novice master made sure that each of the novices and juniors in the monastery had a hobby, and he asked frequently about how it was going. Not a bad tool for formation. Parents would probably be wise to make their children commit to some art, craft, sport, or discipline, and then help them understand life lessons that accompany it.

In the summer of 2009, Br. Martin and I led 40 of our oblates in a study week titled “Art, Craft & Conversion.” On one of the afternoons, each oblate was given a small mirror, a pencil, and a nice piece of drawing paper, and they were asked to draw a self-portrait. They were given no further instructions except to work in silence and to spend the entire hour and a half allotted for the exercise.

There were protests. Those who complained that they couldn’t draw were told that they weren’t expected to be great artists; and those who tried to hand in their drawing after 15 minutes were told that they had to continue working until the time was up. At the end of the afternoon, we had a remarkable discussion about the experience.

One woman shared that although she used a mirror every morning to get

ready for work, she had never spent so much time looking at herself. She remarked how her usual use of the mirror to apply make-up was really an exercise in hiding herself rather than honestly looking at herself. She added that she noticed wrinkles she had never seen before and in time grew more comfortable with them.

Another participant began by saying that she never liked the way she looked: “I always thought I was too plain.” She then shared that, as she drew and stared at herself in the mirror, she began to see her children in her own face and came to love her appearance. All agreed that the exercise had changed them somehow.

A Chinese proverb says: “When you have only two pennies left in the world, buy a loaf of bread with one and a lily with the other.” In his Rule, Benedict makes allowances for artists and craftsmen. Monasteries have never been without artists and art. Benedict seems to recognize the value of their presence and their capacity to deepen our relationship with God, to push us beyond our comfort zone, to stimulate our conversion.

Self-esteem is anchored in humility. That humility understands that we are created in the image and likeness of God, and that we are to live out our lives doing our best to resemble that image and likeness via faith and charity. Hence, we understand that our worth as human beings rests upon a relationship with God and neighbor.

Ego, on the other hand, ignores or scoffs at the idea that human beings are created in the image and likeness of God. Reality is focused on the self, extolling it to the maximum degree. Ego is anchored in pride.

The confusion between self-esteem and ego is accentuated by our culture which highly prizes individualism. If the foundation of reality is the individual, then it only behooves the person to feed the ego. How can I be

the best I can be if I don’t focus on me?

Want to see this contest carried out in daily life? Walk the halls of your local high school. Posters scream “Be the Best You Can Be,” “You Can Do It!” “Keep Trying!” Listen to the conversations of the students: “I’ve never been good at math!” “Ms. X hates me!” “You’re insulting me!”

I’m lucky to teach (theology) at a Catholic high school. One of the courses I teach is Catholic Spirituality (senior elective), and I have my students read Chapter 7 of The Rule of St. Benedict. The students really find fault with step seven of humility (RB 7:51-54). They argue that no one should feel “inferior” to anyone. In reply, I have them look at the hymn at Philippians 2:5-8 where the Lord is

exalted because of his humility. I try to get them to see one of the paradoxes of Christianity: exalting oneself lies in humbling oneself. And that selfesteem, so prized by our school and society, is due to the proper understanding of it: being in the image and likeness of God. Inferiority as outlined in The Rule, and in Christianity in general, is not a matter of unworthiness, but a matter of target: to whom is my love and devotion directed? God and neighbor? Myself?

The Rule is famous for having a “balanced” view of human beings. I firmly believe that a strong antidote to the highly individualistic culture in which we live is Chapter 7 of The Rule of St. Benedict, and that the ego fed by that culture actually needs an authentic understanding of self-esteem.

BY FRANS VAN LIERE Cambridge University Press, 2014

JEFF DAVENPORT Oblate of Carmel, Indiana

This book is packed with dense information, but I found it a delight to read and culled from it bits and pieces for my high school Old Testament and New Testament classes. Divided into nine chapters, this book shows the slow development of how the Bible was put together in the form we know it today. Van Liere clearly explains such arcane terms as “apocrypha” and “pseudepigrapha,” and how those terms have different meanings for different Christian confessions.

The author lays out in an interesting way the transition of the Bible from scroll to codex.

The medieval era is the concentration of this book, and I enjoyed Chapter 5 “Medieval Hermeneutics” as it goes into the different senses of Scripture: allegory, historical, and other senses of Scripture.

I smiled, too, at van Liere’s puncturing the myth that there was no vernacular translation of the Bible until the Reformation.

I think this book is well worth your time. This is not a book you peruse with the TV on. Rather, give it a go with pen and marker at hand in the quiet time after your lectio.

We are a small community but very close because we pray together daily. “

Every oblate chapter is unique in its community and practice. This winter, The Oblate Voice visited with Jennie Latta, chapter coordinator of the Memphis Oblates of Saint Meinrad and got a glimpse into a community of faith that was led by the desire to turn toward deeper prayer.

The Memphis Oblate Chapter chants morning prayer after every Saturday morning Mass at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception. That is really beautiful. Tell me more about that.

The Memphis Oblate Chapter went through major changes when our original chapter coordinator, Gail Chambers, was no longer physically able to be with us. Gail suffered from multiple sclerosis and had to move from her home near the Cathedral to live with her daughter in East Memphis. I was asked to be the cocoordinator. Although the Memphis oblates had been meeting one evening a month, it was easiest for me to meet after the Saturday morning Mass. Once that started, we decided that we might as well pray every week since many of us attended that Mass regularly. We didn’t have another strong singer, however, until Terry Starr started praying with us and eventually decided to become an oblate novice. At that point, I asked the rector for permission to sing the Morning Office after the Saturday Mass. He was happy to say yes! That was in 2017, I think, and we’ve been singing ever since.

During the pandemic, we learned to use Zoom and began praying with

each other morning and evening! We continue to pray together, morning and evening, almost every day of the week. We sing Morning Prayer at the Cathedral Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday. We sing Morning Prayer by Zoom Tuesday and Thursday, and we sing Evening Prayer by Zoom every evening. Not everyone can be present every time, of course, but there are few times when there aren’t at least two of us together at prayer time.

Do you think this public prayer practice strengthens your oblate community?

The public chanting of Morning and Evening Prayer is at the heart of our community. We also read the daily passage from The Rule together after Morning Prayer and talk about it briefly. Most recently, we’ve added lectio divina after Evening Prayer. We started because someone asked who St. Benedict was, so we read The Life of St. Benedict written by St. Gregory. After we finished that, we read The Cloister Walk by Kathleen Norris. We’re reading The Apostolic Fathers in translation now.

Do you think your weekly chant has impact on the Cathedral parish as well?

We certainly hope so! Once a priest who had been the rector of the Cathedral was substituting and agreed to join us for Morning Prayer. He didn’t realize that we chanted the prayer until we started singing. He said, “It’s just like the great cathedrals!” After another minute he

said, “This is a great cathedral!” That’s what we hope—that even those who don’t feel that they can join us will enjoy hearing the sung prayer. And honestly, it is a recruiting tool. Several people have come to sing with us over the years because we have invited them to pray with us after that Saturday Mass. People come and go. Some have moved away, but some are considering formation as oblate novices now. We think of the public prayer as our central act of service to the community, remembering that former Archabbot Lambert taught that oblates pray and study, study and pray!

One of the joys of being a Benedictine oblate is community. How would you best describe the Memphis oblates?

We are a small community but very close because we pray together daily. We have all ages. Janet is in her 90s. Dell (who is a regular but has not entered formation yet) is in her 80s. Terry is in her 70s, and I am in my 60s. We know each other well and care for each other as needed.

We have younger folks who join us now and then. One of our regular male singers, Matt, decided to pursue a master’s degree in Leuven. He now teaches in Dallas. We really miss him, but he joins us when he can by Zoom. There is another oblate, Mallory, who lives in Clarksville, Tennessee. She is a busy physician, so we are thrilled when she pops on to sing with us. Another regular is Terry’s cousin, Anne, who lives in Wilmington, Delaware. Mallory (with her husband) and Anne have both made trips to Memphis to

pray with us in person. There is another physician, Mary Nell, who used to live right behind the Cathedral and prayed with us regularly. She had to move to take care of her parents, but she always prays with us when she is in town. You can be sure that we follow these visits with pancakes or waffles at a local breakfast spot where the fellowship continues!

We remember each other’s feast days, and we remember the oblates from our chapter who have gone before us. There are four that we remember by name during the intercessions in the month of November: Richard, Lyda, Mary, and Gail, and this year we added Janis Dopp. This year, for the Feast of the Presentation and the renewal of our promises, I made the oblates a card with the names and dates of each of our Memphis oblates, living and deceased, that they can keep in their prayer books.

Obviously, your chapter helps tie you to Saint Meinrad Archabbey. Can you explain the ways your community experiences this closeness even though there are many miles between?

I’ve described many of our activities here in Memphis. We did have a dean assigned to us, Br. Joel Blaize, OSB, who we remain close to. He visited Memphis several times. Terry and I worked with him on a recording of the Liturgy of the Hours, and we are part of the committee that is helping him with revisions to our prayer book now.

Over the years, we have had visits from other monks – Fr. Meinrad, Fr. Denis, Fr. Joseph, and Br. John Mark. We also welcomed Fr. Justin and Fr. Damian Dietlein (both of blessed memory). I’m sure I’m forgetting some. We always look forward to our monk visit.

The Memphis oblates try to visit the Archabbey together at least once each year (but I don’t think we accomplished that this year). Those are some special times—as long car rides always are for building community.

Finally, whoever is acting as presider, which is me when I am present, closes the intercessions with a prayer for all the monks and oblates of Saint Meinrad Archabbey, living and deceased. Through prayer, we are reminded daily of our connection to Saint Meinrad.

How does your chapter practice Benedictine hospitality?

The Memphis oblates practice hospitality by welcoming anyone who would like to pray with us. That’s the start, as Chapter 53 of the holy Rule provides. Because we pray at the Cathedral, a lot of visitors join us for prayer. We always enjoy hearing about what brought them to the Cathedral when prayer is done.

We pray for vocations to our way of life every Saturday morning. We often include an intercession for all those who have prayed with us and for those who will pray with us.

We participate in the Cathedral parish’s ministry fair each year to introduce others to the life of the Benedictine oblate. When we are able, we also set up a display at the diocese’s mornings of spirituality.

We look forward to visits from those who have prayed with us but have moved away from the Memphis area. Sometimes when there are special visitors, we’ll have a potluck breakfast at Janet’s house.

Besides hospitality, what portion of The Rule of Saint Benedict do you think helped form your chapter?

“Nothing is to be preferred to the Work of God” (RB 43:3).

What advice do you share with your novices as they journey toward their oblation?

We think it is important to have a novice companion as well as a novice mentor. There are four persons who pray regularly with us now and are considering the novitiate. We have encouraged them to think about entering together so that they will have someone with whom to share their experiences. Terry found that very helpful to her formation.

As we close this interview, can you please share a scripture verse that you think is reflective of the Memphis Oblate Chapter?

“The community of believers was of one heart and mind, and no one claimed that any of his possessions was his own, but they had everything in common.” Acts 4:32 (NAB).

from Saint Meinrad, the Memphis oblates have a history of innovation. We don’t expect to see a monk more than once or twice a year including our trips to the Hill. Over the years, we’ve relied upon CDs and other recordings of talks given by the monks on the Hill. We’ve chosen to read books from the Benedictine tradition. And, in 2016, we asked for permission to sing Lauds in the Cathedral Church every Saturday after the daily Mass. This was a dream of mine for many years – to actually sing the office from the Liturgy of the Hours for Benedictine Oblates When a retired music teacher began praying with us, it became possible. We started slowly because although the tones were familiar to us, the hymns and antiphons were not. We experimented with various ways to find a starting pitch. Eventually, we became comfortable with whatever pitch the cantor chose! And we wanted to spend more time together, so we tried gathering a couple of evenings a week for Vespers. This, too, was a stretch. Although we were comfortable with Saturday morning Lauds, we had to learn the hymns and canticles for

persevered.

The COVID-19 pandemic required further innovation. We could no longer gather together even on Saturdays, but one of us had become very familiar with Zoom because one of her doctors lived in Oregon. She convinced the rest of us to try it.

Praying Lauds at 8 a.m. made sense because that was when we generally finished the weekday Mass, and we prayed Vespers at 6 p.m. because – no one remembers! But we kept at it and have kept at it! There is a core group of three oblates who pray together, but others have come and gone over the years. Twice a day we come together for prayer. Over time, we added the daily reading from The Rule of St. Benedict to the morning office. More recently, we’ve added a short reading from another book in the Benedictine tradition to Vespers – sort of like table reading. We started with St. Gregory’s The Life of St. Benedict and then read Kathleen Norris’s The Cloister Walk

When it became possible to return to daily Mass, we slowly returned to

praying Lauds in person. We started with Saturday, then added Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Tuesday and Thursday are still prayed by Zoom, and Sunday we pray on our own because each of us has Sunday commitments. Vespers continues to be prayed by Zoom. Persons from outside the Memphis area join us regularly –one from Wilmington, Delaware, and another from Clarksville, Tennessee. Occasionally, one of our former regulars who has moved to Dallas dials in. All of us acknowledge that these times of prayer have become central to our daily routines, and we have learned anew the bedrock of community in Benedictine life.

Prayer, reading, community – the Memphis oblates have included these three in our oblate lives not because we don’t look forward to a visit from a monk but because we live 384 miles away from the Hill! We support each other daily in our commitment to the monastic way of life. Perhaps other chapters or small groups of oblates will try the Memphis way!

FR. CHRISTIAN RAAB, OSB Monk of Saint Meinrad Archabbey

On January 25, 2008, I made solemn vows as a Benedictine monk of Saint Meinrad Archabbey. Eighteen months later, on June 7, 2009, I was ordained a priest by Archbishop Daniel Buechlein, OSB, of the Archdiocese of Indianapolis. These two events were, for me, not only the celebrated beginning of a new level of committed service to God and Church; they marked the end of a long and sometimes difficult path of discernment.

Joyfully and gratefully, I reflect upon the fact that the many hard years of going back and forth over whether I should give priesthood and religious life a try, or make a commitment to them, are over. Nonetheless, my heart goes out to those who are still in the throes of discerning God’s call. I know that it can be one of the hardest tasks someone undertakes in life. The following are 10 pieces of wisdom I picked up during my own discernment journey. Most of these were communicated to me, in some way, by mentors, teachers, friends, and family members. They do not constitute a formula for discernment. Nonetheless, they did help me get from point A to point B.

At the heart of the “American Dream” is the idea that one can be anything one wants to be. The glory of living in a free nation is that we have the opportunity to make of ourselves what we will. Alas, we are taught from a young age that it is important to be true to our dreams and, accordingly, plot a course for our lives. All that isn’t unimportant. The problem though, for a person of faith, is that it

can potentially leave God out of the decision-making process.

Vocation comes from the Latin word, vocare, “to call.” It is a calling, a calling from God, who made us, loves us, and has a plan for us. Discernment, then, is different from simply making a decision about a career path or lifestyle. Discernment starts in faith, where we acknowledge God as the source of vocation, involve God in the decision-making process through prayer, and actively listen for God’s will.

2. Vocation is a two-way gift

God really does want us to be happy. When it comes to a vocation, we sometimes struggle to believe that. Perhaps we fear that God will ask us to do something we will hate. Maybe we think God’s will is a sentence to a dreadful life. On the contrary, in John’s Gospel Christ says: “I came that they may have life and have it abundantly” (John 10:10).

But what will make us really happy?

The Second Vatican Council teaches that it is through self-giving that we are fulfilled as human beings. So, vocation is not only something given to us, something we receive, it is also something we freely give to God and others.

3. God preserves our freedom

Because vocation is something we give to God, it is important that we have the freedom to make this offering. God gives us real choices. We have the freedom to marry or enter religious life or remain single. We have the freedom to pursue this or that line of

work. If we are not in a place in life where we are free to commit to a vocation (perhaps due to an immaturity, an undue fear, or an addiction), then we must increase in our freedom before we can make a vocational choice. God, rest assured, helps us in this process.

Furthermore, as long as we are not choosing something evil, God respects the choices we make. We must not believe, as so many in discernment do, that God will reject us if we make the “wrong” choice. On the one hand God really does call us to vocations. On the other God respects our freedom and does not abandon us.

A key insight shared by many saints is that spiritual growth begins in selfknowledge.

God, who will sanctify us through our vocation, has already endowed us with a certain nature. Ordinarily the grace of our vocation will build upon this nature. An awareness of our personal gifts and weaknesses can help us considerably in gaining a sense of which vocations are possible for us and which are probably not wise paths for us to take.

Along these lines it is also important to listen to our hearts, to be attentive to those relationships and activities that give us the most peace and joy. In addition, our dreams and desires are significant. These may even be the promptings of the Holy Spirit showing us ways to creatively respond to God’s call.

5. Christ is the way, the truth, and the life

An authentic Christian vocation is always rooted first of all in being a disciple of Jesus Christ. To better know God’s will for our lives and follow it, it is imperative that we first come to know Jesus Christ and begin to model our lives after his. By encountering the Word of God in Scripture, we receive the light that “enlightens everyone” (John 1:9). His life inspires, motivates, and directs ours.

By receiving Christ in the sacraments, we receive the grace that will empower us to pursue our vocation. By living according to his precepts, we develop the strength to follow him in bigger things later. By surrounding ourselves with God’s people, the body of Christ, we discover the necessary support to initially try out a vocation and later to commit to it and live it out. Before we can be an apostle, “one who is sent,” we must first be a disciple, “one who follows.”

6. Find your place in the symphony orchestra

The Church is like a symphony orchestra. It is one group playing one score but it’s also full of uniqueness. There are lots of different instruments and parts. Personally, I think of that score as love, and I think of the different instruments and parts as being the different vocations in the Church. Finding our vocation, then, is like finding our instrument in the symphony orchestra, our unique way of “playing” God’s love in the world.

It helps in discernment, then, to get as involved with the faith community as you can. It is by taking part in the life of the Church and trying out different instruments—at the parish, on mission trips, in Bible studies, in lay apostolate groups—that you will most naturally find your place in the symphony orchestra.

7. Ask for help

No one can discern a vocation alone. One’s friends, ministers, family members, and fellow parishioners can be helpful sources of support and insight. These folks can often see things in us that we don’t readily perceive. As one progresses a little bit along the path of discernment, a spiritual director is often necessary, especially if one is discerning priesthood or religious life.

Another source of help is the saints. They are also our brothers and sisters in the Church, and they are wonderful intercessors on our behalf. A number of saints are designated patrons of particular vocations, so if one is considering that vocation, it is a good idea to ask that saint for help. For example, the famous 20th-century monk, Thomas Merton, explains that he had reached an impasse in his discernment and felt unable to move forward. He turned to the help of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, who had promised to help young priests, and very quickly after that he obtained the grace to know which religious community he should enter.

8. Expect some “blindness”

I have yet to meet anyone whom God has struck with a lightning bolt and

told exactly what to do with his or her life, nor can I say that ever happened to me. But I have learned to appreciate that “blindness” must in some sense be there. That is true because our vocation must be a gift made in faith. If we knew exactly what God wanted or what would make us most happy, there would be no risk, no cost, and, in effect, no love.

9. God writes straight with crooked lines

One man I know told me that as he approached his wedding, he was overcome by a sense of unworthiness to marry his wife, much less to be entrusted with the children they hoped to have one day. As I approached my own ordination, I felt a similar sense of dread as I became acutely aware of my own sinfulness.

Scripture reminds us, though, that God writes straight with crooked lines. Whatever we have done or whoever we have been in the past, God can still use us. We have only to recall Saints Peter, Paul, and Mary Magdalene to be reminded what God can do with weak human beings!

10. Discernment is not your vocation

Perhaps the most helpful bit of wisdom I received in discernment was the nudging of my spiritual director when he said, “Discernment is not your vocation.” There comes a time in the process of exploring who we are and what we want to do with our lives that we must take a risk and try something. God rewards our efforts, and God can do much more with a mistake than with inertia.

ANGIE

It was 1968, the year of national political upheaval and unrest. While others his age were being sent to fight in Vietnam, young Jonathan Fassero enlisted in a different fighting force: the Catholic priesthood. A member of the first graduating class of Marian High School in Mishawaka, Indiana, he had been attracted to the priesthood from a young age. Growing up in St. Bavo Parish, he assisted at Mass as a server alongside priests he recalls as being very happy and who shared with him that being a priest was “a noble kind of life.”

He promptly answered that call, applying to and being accepted by the Diocese of Fort Wayne/South Bend. A college degree was the next step, which for Jonathan would be fulfilled at Saint Meinrad College. Although at first he was focused on the diocesan priesthood, Fr. Jonathan felt that direction shift toward the monastic life by the time he finished his undergraduate work. He attributes this to the outstanding examples of the Benedictine priests he studied under and lived alongside. “They’re the ones who inspired me to apply to the monastery,” he says. “They were the great lights in my life.”

During those formative years, he had noted the history of the Archabbey— how priests from Switzerland came to an unknown foreign land to establish this community in 1854 and how their consistent life of prayer and worship had continued from that time to the present. “I wanted to be a part of that,” he says.

On August 24, 2024, Fr. Jonathan celebrated 50 years since his profession of vows. He has served in a number of capacities through the years mostly on behalf of Saint Meinrad Seminary and School of Theology.

As an associate director of spiritual formation in the School, he provides guidance to the 116 seminarians in priesthood formation from 21 dioceses and seven religious communities. These include nearby Evansville and Indianapolis along with dioceses in Alabama, Arkansas, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, and even South Korea, as well as several abbeys and other communities. He does the same every other week from Wednesday to Friday up in Indianapolis at the Bishop Simon Bruté College Seminary as that institution’s spiritual director. To top

it off, he also visits other dioceses to promote interest in the priesthood as the Archabbey’s director of diocesan relations. “Hearing stories of how others are inspired to become priests is a very fulfilling time,” he relates.

And how is the outlook for priests these days? “It’s challenging, but I’m optimistic,” Fr. Jonathan maintains. “The Archdiocese of Indianapolis has an excellent vocation director and recruiter, and other dioceses have [priesthood] outreach programs.” Vocation promotion by the laity cannot be underestimated, either, including help from organizations such as the Knights of Columbus and the Serra Club.

The other side of this coin includes prayer for vocations, especially those offered by the oblate community both at home and in chapter meetings. “We cannot underestimate the power of prayer [by the oblates]. We are enormously indebted to the oblate community for their prayer support,” Fr. Jonathan says. “You are the anchor in the world for us … you are taking the time out to pray, and we need very much the prayer that you make time for every day. It is an enormous gift.”

Hosted by Fr. Denis Robinson, OSB, Br. Michael Reyes, OSB, and Corinna Waggoner July 21-August 2, 2025 (13 days)