“Do not be daunted immediately by fear and run away from the road that leads to salvation.”

(The

Rule of St. Benedict, Prologue 48)

Two gardeners were sharing a garden plot. While they worked together planting and watering, they agreed to care for the garden each on alternate days.

The next day, the first neighbor found the garden had already dried out. Seeing some clouds, she decided to hope for rain, but no rain came. The day after that, the second neighbor found the garden parched and immediately watered it.

A few weeks later when weeds started to pop up among the seedlings, the first neighbor noticed the new little weeds had thorns and decided to wait on pulling them, hoping the vegetables would grow faster than the weeds and snuff out their sun’s light. The second neighbor arrived the next day, saw the tiny weeds, bent down, and began pulling them with gloved hands.

If, however, the needs of the place or poverty requires that they themselves be involved in gathering the harvest, let them not be sad, for then they are truly monks if they live by the work of their own hands, as also did our fathers and the apostles (RB 48:7-8).

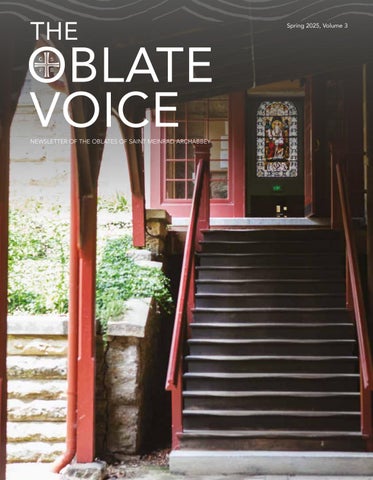

The Oblate Voice is published three times a year by Saint Meinrad Archabbey.

Editor: Krista Hall

Designer: Camryn Stemle

Oblate Director: Br. Michael Reyes, OSB

Oblate Chaplain: Fr. Joseph Cox, OSB

Content Editor: Diane Frances Walter

Send changes of address and comments to: The Editor, Development Office, Saint Meinrad Archabbey, 200 Hill Dr., St. Meinrad, IN 47577, 812-357-6817, fax 812-357-6325 or email oblates@saintmeinrad.org www.saintmeinrad.org

©2025, Saint Meinrad Archabbey

Weeks turned to months, with the first neighbor hoping good things would happen for the garden and the second neighbor actively tending and watering it. Eventually the two neighbors had harvestable produce and went about collecting their shares for meals to come.

The first neighbor, proud of the garden and happy about the harvest declared solemnly, “This garden was a lot of work.” The second neighbor already on her knees pulling beans and tossing them into a basket said softly, “God has blessed us with a beautiful harvest.”

In a chapter about daily manual labor, Saint Benedict outlines what is in store for those who follow The Rule. The chapter is focused on prayer and reading, studying and engaging in a trade. However, right in the middle of the chapter is one standout paragraph about working the harvest. In the fifth century, the world was still made up of agrarian societies. Planting seeds and harvesting was not only commonplace, it was essential. St. Benedict clearly recognizes that working on the harvest is difficult and notes that those who follow his Rule should not “be sad,” if they must do that dirty work.

Gardeners know there is great risk when seed is put into the ground. Everything about doing so matters from the depth of the seed in the soil, to the watering, and even to the protection given so that crops will not be eaten by wildlife. There is great risk in the care of those plants as well. If they are overcrowded, thinning seedlings is necessary. If weeds pop up, those weeds need to be removed before their roots wrap around the bases of tender greens. When the time is right, knowing how to harvest correctly for some types of vegetables and fruits means the crop can regrow

for a second, or even a third collection.

It is not clean work. Hands and clothes get dirty. It is not easy work. It requires uncomfortable kneeling and bending, as well as physical stamina for longer repetitive tasks. There is no air conditioning and there is no guaranteed schedule to keep. Wind, rain, or heat can force a gardener to cancel a day of needed work. A perfectly mild day can mean hours of catching up for lost time.

Do everything perfectly and a row of vegetables may be destroyed by flooding, by caterpillars, or an unseen fungus. Do the work clumsily, and you may have baskets overflowing with food.

No matter the effort, much of what a gardener relies on is outside their own efforts. Indeed no matter what a monk or oblate does, whether it be

lectio divina, writing, reading, or keeping up with daily tasks, all that we accomplish relies on God’s creation of us and His companionship with us.

We celebrate our becoming by doing what is necessary in life, and by doing what helps us grow. In this way, we also are a little like seedlings in a garden.

Idleness is the enemy of the soul. Therefore, the brothers ought to be occupied at fixed times in manual labor, and again at fixed times in lectio divina (RB 48:1).

The reason for our daily labor is not just to save us from boredom, but also to remind us with whom we are to place our gratitude. If we work by our hands, we meet the opportunity to share. We share what we have grown by nourishing each other. We share what we have realized in Scripture by

actively living with those insights. We share what we have read by encountering dialogue with refreshed wisdom. Even if we work alone, pray alone, read alone, or plant seeds alone, all those efforts eventually invite the opportunity to share.

As is true of the entirety of The Rule, St. Benedict points us toward service to each other and service to God. We are willing to get our hands dirty knowing that we are like the monks and those before us if we live by the work of our hands. We learn that our efforts though often small, inconvenient, uncomfortable, and common, rely ultimately on the gifts, graces, and will of our Creator.

Hopefully we answer our harvests with humility, already putting into our baskets what has been grown, and declaring with confidence that God has blessed us. Hopefully we share our harvest with our neighbors.

STEVEN SMITH Oblate of Cincinnati, Ohio

As an oblate, my life is not bound by the cloister walls, yet I am deeply connected to the rhythm of Benedictine spirituality. The Rule of St. Benedict serves as both a guide and a challenge, inviting me to embrace service as a way of life in the ordinary circumstances of everyday existence. Through its wisdom, I am reminded that service is not simply an action but a way of being that reflects Christ’s love in the world.

In Chapter 35 of The Rule, St. Benedict writes about the importance of serving others in the daily tasks of life, such as preparing and sharing meals. He stresses that the kitchen

servers “must be given help so that they may perform this task without grumbling.” This instruction might seem obvious at first glance, but it reveals a truth that often escapes us: service is an act of humility and love, not merely a duty. For me, this means approaching even the smallest tasks— washing dishes, running errands, or listening to someone’s struggles—with a spirit of willingness and gratitude.

One of the most transformative aspects of Benedictine spirituality is that it recognizes the sanctity of the ordinary. The Rule teaches me that there is no distinction between sacred and secular work when it is done in

the service of others and offered to God. St. Benedict’s concept of ora et labora (pray and work) reminds me that my daily responsibilities are opportunities to encounter Christ. Whether I am caring for my family, engaging with co-workers, or volunteering in my community, I am called to serve with the same attentiveness and reverence that I bring to prayer. In all that we do – all that we are – we need to be mindful that we reflect the spirit of Christ that is in each of us.

Hospitality, another hallmark of Benedictine life, also shapes my understanding of service. Chapter 53

of The Rule instructs monks to welcome all guests as Christ. For an oblate, this means cultivating a spirit of openness and generosity, not just to strangers at my door but to everyone I meet. It challenges me to see Christ in the difficult co-worker, the friend in need, and even the person who interrupts my plans. Hospitality is not always easy—it requires a willingness to set aside my own desires and make room for others, physically and emotionally. Yet it is in these moments of self-emptying that I feel

most connected to the heart of Benedictine service.

Of course, there are times when service feels burdensome, and my heart resists the call to give. Here, The Rule’s emphasis on stability becomes essential. Stability teaches me to remain rooted where I am, trusting that God is present even in the monotony of life’s demands. By staying faithful to my commitments, I discover that service is not only grand gestures, but about showing up

consistently and offering what I can, however imperfectly, day after day after day.

As an oblate, I am reminded daily that service is not something I must do to earn God’s love—it is my response to the love I have already received. Through the wisdom of St. Benedict, I have come to see that service is not merely an obligation, but a part of who we are, that service to others is a privilege. It is in serving others that I draw closer to God, for in their faces, I see His.

FR. GUERRIC DEBONA, OSB Monk of Saint Meinrad Archabbey

Editor’s note: This is the third article in a three-part series.

St. Benedict’s insistence on the virtue of obedience is well known. The holy Rule devotes an entire chapter (Chapter 5) to this remarkable and admirable quality. And, indeed, even a cursory glance of The Rule of St. Benedict reveals a strong and consistent insistence on the role of obedience for monastics.

Why is obedience to be cultivated as one of the greatest virtues? St. Benedict suggests that obedience is a kind of lynchpin to even greater attributes. In the opening lines of the Prologue, for example, our holy father Benedict says that it is the labor of obedience that will bring us back to the Lord from whom we have drifted, “Yes, obedience is better than sacrifice, submissiveness better than the fat of rams” (1 Sam. 15:22). The implication is that obedience, well developed, is at the service of the Gospel of Love. That is why it is important for monastics to have “unhesitating” obedience.

It is no accident that St. Benedict also makes obedience the gateway to what is perhaps the most treasured monastic quality: humility. Chapter 5 of The Rule says humility will grow from unhesitating obedience, which comes naturally to those who cherish Christ. Chapter 71, then, states the significance of obedience when it says that “obedience is a blessing to be shown by all, not only to the abbot but also to one another as brothers, since we know that it is by this way of obedience that we go to God” (RB 71:1-2). Obedience builds bridges to heaven.

Since St. Benedict links cultivating the virtues and seeking God to obedience, it is perhaps no accident that he described its ideal manifestation as a reflex action: unhesitation. Rightly lived, obedience becomes unselfconscious and immediate. As a matter of fact, real obedience leads to nothing less than what St. Benedict describes in Chapter 72 as “that good zeal which

separates from evil and leads to God and everlasting life” (RB 72:2).

For St. Benedict, obedience is the great workhorse that plows the fields of the Lord. In this view, he is perfectly in accordance with Biblical tradition. The quality of obedience in Sacred Scripture is, after all, as old as Abraham’s unfaltering heart in Genesis. Abraham, as we know, went so far as to be willing to sacrifice his only son, Isaac, at the command of the Lord. Even though the Lord spared him this terrible act, Abraham’s faith was shown precisely because he obeyed the Lord— unhesitatingly.

So it is that in the later theological tradition of the early New Testament, St. Paul would account for Abraham’s righteous place as the father of the people of Israel because of his singular and courageous act of obedience. Mary’s Magnificat, propelled by an essential oneness, is an obedience of God’s Word. As Jesus would later tell

His disciples, “Blessed is the one who hears the word of God and keeps it” (Lk. 11:28).

And of course, Our Lord Himself becomes the model of obedience par excellence. We might even say that the entire doctrine of the atonement, where Christ Jesus redeemed us from Original Sin, is rooted in obedience. God becoming flesh embodies obedience in the service of Divine Humility.

It is easy to see, therefore, that obedience is a discipline that repairs, even recreates, our relationship with God. Obedience is not a series of acts grudgingly done because we feel we must do them, but the response of a willing heart in the service of God and our neighbor. In perfect obedience we create and redeem.

Obedience is a quality which must be “radical”—that is, from the Latin radix (meaning the root of a tree). So obedience goes to the very roots; it

involves our whole being and demands a response. In considering the ways of obedience, we cannot fail to be reminded of the echo of St. Benedict’s opening word: “Listen.” Listening is like that: we must surrender ourselves to the language of God.

Through obedient listening, God wants all of us—everything. That is the one thing that the wise practitioner of obedience will notice, that it is an “all or nothing” virtue. No wonder obedience builds so many bridges; no wonder it is a key to the ladder of humility. You cannot just obey partially. Doubtless, this complete surrender to obedience accounts for St. Benedict’s parallel insistence on silence, which, as the listening heart, becomes the willing companion of the obedient heart.

The call to obedience is operative, certainly, as a heroic stance. Many martyrs, such as St. Thomas Moore, were called to serve God over their secular duties. But obedience is also

available in the circumstances of dayto-day living. St. Benedict had obedience in mind for a monastic, but there is a monastic in everyone who hears the Word of God and keeps it. Imagine a world of charity, justice, and peace in which all of us become mutually obedient to one another! Obedience is a guaranteed way of seeking God because obedience, if properly ordered for the sake of the Kingdom of God, becomes a gateway to the face of God.

Obedience, or active listening, is not a project we take up. Rather, it is a way of being in the world. God’s Will is not a puzzle to be solved, but a mystery to be lived! For the Benedictine monk, nun, or oblate, listening and living is achieved through an attitude of contemplation. Contemplation is nothing more and nothing less than “listening with the ear of the heart” to the joy of discovery of God in every aspect of our lives, as we are invited by St. Benedict.

FR. MARK O’KEEFE, OSB Monk of Saint Meinrad Archabbey

Gospel: Matthew 20:1-16

Our God is a mysterious God. Of course, He wouldn’t be much of a God if He weren’t mysterious, would He? Our God wouldn’t be much of God if we could fully “get our minds around” Him. God is a mystery. His ways are often hidden to us. His plans are beyond us. No wonder our first reading says:

“My thoughts are not your thoughts … nor are your ways, my ways … As high as the heavens are above the earth, so high are my ways above your ways … and my thoughts above your thoughts.”

Our God is a mysterious God. And sometimes, we don’t much like that fact. Sometimes, we think that a truly good God should act in certain ways—free us from our problems, heal our loved ones, prevent natural disasters like hurricanes and earthquakes, or thwart the plans of evil dictators. To our way of thinking, things like that would just seem to make sense—for a good God. Sometimes, we think that God should answer our prayers the way we want— not for trivial stuff, maybe—but at least when we ask for important and urgent and worthy things. But our God is a mysterious God. His thoughts are not our thoughts. His ways are not our ways. And sometimes, that fact can be pretty frustrating.

But, at the very same time, we’re actually pretty lucky that God doesn’t think like we do. If I were God, I wouldn’t put up with me … or probably not with you, for that matter. That is, I wouldn’t forgive me as many

times as God has forgiven me. I certainly wouldn’t keep forgiving myself for doing the exact same things over and over again. If I were God, I’d probably favor some people over others (even if I tried hard not to). There’d be a limit to my generosity, an endpoint to my help; there’d be some “downtime” in my being present. And if I were God, I’d be a whole lot choosier about my friends, who I would invite into communion with me, and certainly who I would want to spend eternity with. Thank God, God doesn’t think like me (or you). Thank God that His ways are not my ways (or

My thoughts are not your thoughts ... nor are your ways, my ways ... “

knowing full well that the workers who hadn’t already been hired were probably not already hired for a reason: they were old, or weak, or sickly. But they still must have had families to support, so the landowner hired them too.

Now, since these guys needed the work—especially the ones hired later in the day—the landowner probably could have gotten away with paying them a whole lot less than a day’s wage. And if they needed the work badly enough, they probably would have agreed to it. But this particular landowner—this divine landowner—was being generous—unexpectedly, surprisingly, undeservedly generous. This is a story about a God who doesn’t think like we do. And it’s a story about people who depend on that not-like-us divine generosity—people like you and me.

yours). I’d say we’re really pretty lucky about that!

Our Gospel today is a perfect illustration of this—an example of a God who doesn’t think like we do. If we had a farm, we’d hire the best laborers for the best price, we’d hire just the ones we need, and we’d be sure they’re the best. That’s the way you minimize costs, maximize profits, and ensure a good yield on your investment. But this is a story about a landowner who went out and hired a bunch of guys who didn’t have stable work—guys who needed a job—and it sounds like he just hired the first ones he came upon. Then, this landowner went out several more times in the same day and kept hiring workers,

And if it’s true that God probably knows better than we do, and since God is God, and He’s probably going to do it His way rather than ours anyway, and if we think His thoughts might just be wiser than ours and His ways better than ours—even if we can’t always understand them—well, then, maybe we should try harder to get with His program rather complaining that He hasn’t gotten on board with ours. You know, like trusting Him. Like holding on in faith through whatever problem we face. Like always hoping in the better ending that God has planned— even when we can’t yet see it. Maybe we should try making our ways more like His ways—His ways of love and generosity, of compassion and caring, and of forgiveness. Maybe we should try harder to make God’s ways our ways, rather than the other way around.

KURT STASIAK, OSB Saint Meinrad Archabbey

Editor’s note: This is the third article in a five-part series.

The virtues of those whom Benedict considers to be “good monks” are as obvious as are the vices of those whom he deems “bad.” And the most obvious characteristics of the “good kinds” of monks present a marked contrast to those of the “bad.” The cenobites submit to life in a monastery under a rule and an abbot, precisely that which the sarabaites choose not to do, while the hermit’s anchoring in his cell is far removed from the constant wanderings of the gyrovague.

Yet the more visible features of the life of the cenobite and the hermit, attachment and firm commitment to a community, and “full-time” solitude, are such that when pursued with a misguided zeal they, too, can lead to tendencies that distract us in our search for God. Benedict was well acquainted with the need for moderation to balance even good zeal. In his chapter on the Lenten observance, for example, Benedict insists that whatever penance or additional good works the individual monk commits himself to should receive the blessing and approval of the abbot, for “whatever is undertaken without the permission of the spiritual father will be reckoned as presumption and vainglory, not deserving a reward” (RB 49:8-9).

Solitude is as important to the hermit as community is to the cenobite, but

an excessive or misguided quest of either can pose as great a hindrance to our spiritual life as can the sarabaite’s willfulness or the gyrovague’s procrastination. “Too much of a good thing,” as some would say, or perhaps too much of a good thing for not-sogood reasons. For community and solitude, the two characteristic features of Benedict’s “good kinds of monks,” can be sought as ends in themselves rather than as means that further our journey to our ultimate end.

In his play Murder in the Cathedral, T. S. Eliot depicts this danger in unforgettable verse. Struggling in the midst of political, personal, and religious pressures to discern God’s will, the right thing to do, the Archbishop of Canterbury utters a reminder often as frustrating as it is necessary: “The last temptation is the greatest treason; / To do the right deed for the wrong reason.”1

Let us consider how a misguided, excessive or unbalanced zeal as regards our life in community or our search for solitude can persuade us into doing some of the right deeds of the monastic life for the wrong reasons.

The cenobites: May they remember to seek God in community.

Benedict actually has little to say in the first chapter about this first kind of “good monk”; it is in the following 72 chapters that he will provide

detailed instructions for his cenobites, “those who belong to a monastery, where they serve under a rule and an abbot” (RB 1:2).

Few Benedictine vocation directors report large numbers of applicants driven by the express desire of “[serving] under a rule and an abbot.” Rather, what usually attracts young men and women to our way of life is the notion of belonging to a monastery, of living in a community. A community gives one identity and a sense of purpose (no small goals for us today), as it also offers, or is thought to offer, the remedy for many of the pains and problems reported frequently by single ministers today: that they live and often work alone with little or no support, that they have insufficient opportunities in which they can share their ministerial experiences or spiritual lives and that, in such an isolated climate, they find it increasingly difficult to develop strong and intimate friendships.

Many of us do enjoy healthy and lasting friendships within our communities, and there is no reason to minimize or criticize the importance of such relationships. These friendships, if they are truly healthy and bear no resemblance to the self-designated sheepfolds of the sarabaites, encourage and support us on our journey. A relationship that takes as full advantage as possible of the many features

1 Words of Thomas Becket in T.S. Eliot, Murder in the Cathedral (London: Faber Paperbacks, rpr. 1982), p.47. Later in the same soliloquy, Becket remarks: “Servant of God has chance of greater sin / And sorrow, than the man who serves a king. / For those who serve the greater cause may make the cause / serve them, still doing right …”

inherent in living together (a common mission, shared work and prayer, the mutual experience of growth, hardship and assistance often spanning many years) is a treasure indeed.

But such solid and enduring friendships and the healthy intimacy that can be effected through them are unexpected treasures. They are gifts occasionally offered us as we proceed through our years of living with one another; they are not the automatic or necessary consequence of living in common, an observation to which most any husband and wife of at least several years will attest. And, as is the case with all gifts, while we are free to accept and develop these gifts of friendship or intimacy when they are offered us and are, in turn, free to offer them to others, we can neither demand them for ourselves nor impose them upon others.

Friendship and intimacy are among the more treasured gifts a common life has to offer, and these gifts can do much to speed us on the path of God’s commands. But, when friendship and intimacy are vigorously sought after or pursued for their own sake, they can also distract us in our search for God. We certainly do the right deeds when we promote and foster new relationships and develop those we already enjoy. When the desire for friendship or intimacy takes on a life of its own, however, those right deeds can be undertaken for the wrong reason. Today’s culture habitually gives its own slanted interpretation of the Creator’s observation that “it is not good for Adam to be alone,” and often suggests friendship and intimacy as the universal pot of gold. Many would have us believe it is (only) friendship and (especially) intimacy that makes us real people, and the clear implication is that if we do not have friends and are not truly intimate with them, we are missing everything.

In the light of such claims (do they not often seem more like taunts?), the rush to friendship or intimacy can overtake our hearts to the extent that achieving friendship or arriving at intimacy become goals that we cannot afford not to pursue. But again, friendship and intimacy are gifts that are offered; as desirable as they are, they simply cannot be considered as legitimate expectations or as an automatic outcome of living in community. The desire for friendship may often be one of several initial attractions for those considering life in community, but the quest for friendship and intimacy cannot become the reason one remains in that life. The purpose of the monastic life is, above all else, to seek God.

It is when friendship and intimacy are pursued with a disproportionate desire, when the as-yet-to-bediscovered friend or the as-yet-to-beexperienced intimacy becomes the treasure hidden in the field or the pearl of great price for which we are constantly in search, that the good zeal for the cenobitic life has exceeded its bounds and has run amok. The gifts that may be offered through a life in common, such as the possibilities of friendship or intimacy or the greater likelihood of receiving support and assistance, are now pursued for the wrong reason. No longer considered, recognized, and appreciated as gifts, they have become benefits (“right deeds”) sought after and attained for their own sake (“wrong reasons”). We profess that we are living in community to seek God, but our heart and our actions suggest that we are in community to seek friends.

The emotional and psychological hazards of such a misguided or unbalanced zeal are worth addressing, but those hazards are not my primary concern here. My point (I am

suggesting that an excessive zeal [“too much of a good thing”] can distract us from our spiritual quest) is that if my life in community focuses too much on seeking friendship or intimacy (goods in themselves), my search for God may become blurred at best or, at worst, be entrusted largely to my spare time or, perhaps, to the annual retreat or occasional days of recollection.

God’s grace can certainly be experienced and fostered in the stuff of the common life itself. It is the community, after all, that is the “workshop where we are to toil faithfully at [the tools for good works]” (RB 4:78), and precisely, because we are not hermits, we are to seek the face of God in the faces of our confreres. This we do in our hours of common prayer and in the common room, in the service we offer to and receive from one another, and in our mutual endeavors and private conversation. Developing friendships, responding to and encouraging a healthy intimacy, taking a genuine interest in the individual and collective lives of those around us, simply passing the time and our lives in comfortable conversation with those whom we live: these are good things, they are the right deeds.

But let us remember what is ultimately the right reason for these right deeds, and take what steps we must to live happily and at peace not only in the midst of others but, especially, in the peace of the One who calls each of us. If our search for God in our life together seldom allows us the time or leads us to return to the privacy of our cell and the solitude of our hearts, a keen sense of the presence of God can be lacking in the one place where God seeks most to dwell. Being lonely is unattractive; being alone is neutral; being alone with God, and assuring that one both has the time and develops the need for that kind of aloneness, is essential to the private and communal life of the monk.

I offer a final comment as regards the tendency of mismanaging the means of our common life. Each of us wants to do well, to be a good and faithful pupil in the “school for the Lord’s service” (Prologue, 45). Most of us also want to live with people with whom we can become friends and grow in intimacy, and many of us throughout the course of our years have acquired and developed skills that have allowed us greater emotional and psychological health. Few of us relate to people now as we did when we were in high school or college, and the change is usually for the better. At times, we can take justifiable satisfaction in the healthy, sturdy

relationships with which we have been blessed. Again, there is everything right about this, as true friendship can contribute mightily to our spiritual quest for God, as well as to our own psychological health. The hazard is that, at times, we may equate our skills or our success in building relationships or the joys stemming from those relationships with the true peace that only God can offer and that can be found in Him alone.

Our friendships with one another should bolster, not replace or stunt, our desire to continue seeking and developing that which we will never find completely in our community or

anywhere else: that perfect communion with God that casts out all fear (RB 7:67).

Let us, by all means, attend to building healthy relationships. But let us not equate too quickly or confidently our success or progress in experiencing the real and legitimate benefits of our friendships as an indication that our search for God is progressing as smoothly or is enjoying the same depth.

In the fourth article in this series, the anchorite will be discussed.

Our friendships with one another should bolster, not replace or stunt, our desire to continue seeking ... that perfect communion with God that casts out all fear. “

“In Sermon 84, in his Sermons on the Song of Songs, St. Bernard writes that there will be no end to the search for God even after we are with God in heaven. Give me 200-250 words on why St. Bernard believes that.”

So Mark Plaiss instructs his high school seniors about midway through the semester-long elective course entitled “Catholic Spirituality.” He reads their responses on Google Classroom, where he posted the assignment. Plaiss had the class read the sermon aloud after the class had read the Song of Songs—again aloud—in the previous two classes. Plaiss did not have the class read all of St. Bernard’s sermon. Rather, they read those passages demarcated with brackets that Plaiss had inserted into a photocopy of the text. The bracketed material amounted to less than half of the seven numbered paragraphs of the sermon.

To give you a flavor of the students’ responses, here is an example: “Our search for God is most comparable to the human concept of friendship. When looking for a friend, the goal is not to just make a friend and be done, rather, you want to continually spend time with that person. You enjoy that friend’s company and, in theory, never grow old with each other. Our relationship with God is the perfect friendship: one that never grows old.” Here is another student response: “There will be no end to the search for God even after we are with God in heaven because there is no limit to love. There is no maximum amount that we can love another person, or another person can love us, and this same concept applies to God.”

Plaiss and Jeff Ptacek teach at Carmel Catholic High School in Mundelein,

Illinois, a northwest suburb of Chicago, closer to the Wisconsin state line than to the Loop. The school is directly across the street from the University of St. Mary of the Lake, Mundelein Seminary.

The school was founded in 1962 by both the Order of Carmelites and the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Originally, the school held classes separately for boys and girls, though under the same roof and in different parts of the building. In 1988, the school became co-ed. At the time of this writing, the student population hovers around 1,100.

The “Catholic Spirituality” course was originally conceived as a follow-up to the Kairos retreats the school offers to seniors. The basic purpose of the course is three-fold: teach the students to pray the Liturgy of the Hours, introduce and immerse them in lectio divina, and have them read primary sources (in English translation) of the great Catholic spiritual masters.

Shorter Christian Prayer is used for the Hours. If the class meets before lunch, the class prays Morning Prayer. If the class meets after lunch, they pray Evening Prayer. All students are assigned to lead an Hour, and all students are assigned to proclaim the reading for the Hour. Over the years, the theology department has debated whether to use Christian Prayer for praying the Hours, but the department decided that the “flipping” involved with that volume would be counterproductive. Since Plaiss can carry a tune and stay on key, he leads the hymn for the Hour (“Go Tell it on the Mountain” has become the de facto theme song over the years. Christmas carols are requested during the year, not just at Christmas time).

Morning or Evening Prayer takes about 10 minutes.

Lectio Divina comes from only the Bible; students can choose from either the Old or New Testaments. Plaiss allots ten minutes for lectio, marking the conclusion to the prayer by striking a meditation bell. Plaiss introduces lectio to the class about a week after introducing the Hours. Plaiss finds Michael Casey’s Sacred Reading: The Ancient Art of Lectio Divina and a chapter from Casey’s Coenobium to be very helpful in explaining this form of prayer. The slow-paced reading initially baffled students in lectio (“If you finish your book of lectio before the semester ends, you’ve probably read it too quickly,” Plaiss notes).

Thus, the first 20 minutes of each 65minute class are devoted to prayer.

The “textbook” for the spiritual masters is a three-ring binder of photocopied material from disparate texts (from Plaiss’s personal library) ranging from Evagrius to Thomas Merton. Most of the readings from these texts amount to one to two pages. These texts are read aloud by the students after prayer, with Plaiss frequently stopping their reading to ask questions.

The course begins with a unit on what Plaiss calls the foundation. The class reads a smattering of Plato, Aristotle, Maritain, and Roger Scruton to discover what is real, what is good, and what is beautiful. The next unit is headed Faith & Prayer, where the class reads Michael Casey’s and Gabriel Bunge’s thoughts on prayer. Christian Smith’s essay “Moral Therapeutic Deism” (this is a hoot to read with students. “Spot on, Mr. Plaiss,” they

say with a nod) and excerpts from Abraham Joshua Heschel’s Man is Not Alone round out that unit. After that, the reading of the old masters begins. The masters are read in chronological order.

Twenty-five to thirty 200-word reflections are assigned throughout the semester course. Reflections are weighted heavier than the one quiz (at mid semester) and the one test (at the conclusion of the semester). The quiz is essentially “what-every-studentgraduating-from-a-Catholic-highschool-should-know” (What is the Paschal Mystery? What is a sacrament? What are the three Sacraments of Initiation? And other such questions). The test is oral. This test requires the students to select a passage from either the Old Testament or the New Testament of at least 180 words. Plaiss figures a passage of such length provides a true challenge, but not a challenge arduous enough to be overwhelming.

The students read the passage aloud to Plaiss as he follows along in his Bible. Plaiss stops them to ask questions about what they have just read. Usually, he asks the students to identify the antecedent of pronouns, or to identify a person mentioned in the passage. For example, a student once read a passage from the New Testament that mentioned Solomon, and so Plaiss asked the student who Solomon was. Plaiss is not looking for any deep theological insight, here. The purpose of the test is simple: can you read a passage of Scripture and tell somebody what it says?

Meanwhile, across the hall from Plaiss’ classroom, Jeff Ptacek is wrestling with seniors in the elective course “Catholic Philosophy.”

“‘There are two ways of waking up in the morning,’ Archbishop Fulton Sheen once said,” Ptacek says to his class. “‘One is to say, ‘Good morning,

God,’ and the other is to say, ‘Good God, morning!’”

Over the past 17 years, Ptacek has had the pleasure of introducing high school seniors to the study of philosophy. The course is properly titled “Catholic Philosophy,” but that title is a misnomer. Perhaps, a better course title would be Philosophy Applied to Catholic Thought. The primary text he uses is Peter Kreeft’s The Journey: A Spiritual Roadmap for Modern Pilgrims. In the book, Kreeft is the main character who finds himself in a dreamlike state within Plato’s Allegorical Cave. It is from the cave that Socrates leads Kreeft on a journey of philosophical discovery. Ptacek takes the students on the same journey with Kreeft. Along the way, they encounter some of the most wellknown philosophers in history.

Bishop Sheen’s quotation about God opens the course. Philosophy is about perspective, and Carmel Catholic High School desires to graduate students with the perspective that as St. Irenaeus said, “the glory of God is man fully alive.” Throughout the course, Ptacek examines philosophical points of view that reflect the negative, “Good God, morning” perspective. These philosophies demonstrate a turn inward, focusing on the base characteristics of humanity estranged from God. The beauty of Kreeft’s book is his ability to flip the script and challenge the reader to see that it is really the turning outward towards others, towards God, that results in an experience of being fully alive. The journey of the course challenges the students to examine their own beliefs and question their biases as they hopefully grow in their awareness of God as the source of Truth.

The course is also remarkably fun to teach. Many of the students who take the course are well read, however, they have rarely, if ever, read the kinds of work uncovered in class. Besides The

Journey, Ptacek has the students read parts of Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. The class reads commentaries on how Epicurus and Pythagoras address happiness. The class examines epistemological questions on truth and knowledge in response to Sophists. Towards the middle of the semester, Ptacek looks at more modern examples of philosophical thought and its impact on the modern understanding of reality. Ptacek has his students read selections from Nietzsche and Marx, Sartre and Foucault. All the while, the students wrestle with developing their own philosophy of life.

Many students who take “Catholic Philosophy” also enroll in Plaiss’s elective, “Catholic Spirituality.” The two courses reflect what St. John Paul II called in Fides et Ratio, the wings on which the spirit rises to the contemplation of truth. Faith and reason, spirituality and philosophy attract the head and the heart while drawing the whole student closer to truth. The courses share many of the same readings, though they are applied differently. Students in Plaiss’s spirituality class are expected to be practicing Catholics or Christians; God’s existence is presumed. Students in Ptacek’s philosophy class are presumed to be questioning the whole idea of God. Both Plaiss and Ptacek accompany the students on a journey where both the head and heart are engaged.

Plaiss and Ptacek both have seen the fruit of these two courses develop and ripen as the students take on leadership roles in the senior retreat program known as Kairos. During the retreat, students give talks in which they share their struggles and successes, while tying them to their overall relationship with God. Both Plaiss and Ptacek often hear in these reflections the content covered in their respective classes.

As a model for Catholic education, the Philosophy and Spirituality Courses have an invaluable place in the students’ formation. In our digital age, where we are challenged by AI and ChatBot, we need to introduce our students to the act of thinking and praying. Modern society demands an inward turn towards the self. The great legacy of the great philosophers and spiritual masters is their perspective on the discovery of Truth requiring an outward turn.

***

In his book The Way of St. Benedict, Rowan Williams writes that monasticism “embodies” two countercultural ideas. First, monasticism claims that time can be sanctified, and second, monasticism stresses dependence. The Liturgy of the Hours and lectio divina in Plaiss’s “Catholic Spirituality” class address the former issue. Students’ time at school divides into three broad categories: instruction, lunch, and phones. The Hours and lectio illustrates to the students that eating lunch with friends and doing God-only-knows-what on

the phone need not be profane time. As Williams notes, “How we spend the time we think is insignificant is important.”

Regarding dependence, consider this maxim frequently touted at the school: no one eats [lunch] alone. The school is a community with a common purpose, not a haphazard collection of persons with individual agendas. Both Plaiss and Ptacek have walked through the cafeteria during the lunch waves, and both have witnessed students eating alone. However, both teachers have also seen students invite loners to join them or have seen students plopping down at the table with the loner. This idea of not eating alone illustrates that human beings depend on one another and not human beings who, as Williams writes, “are seduced by visions or promise of autonomy as the greatest imaginable human good.” The two teachers push that idea still further in class. “Don’t you see,” they say to the students, “that the ‘no one eats alone’ mantra you embrace so zealously can apply to God and God’s Church?”

And that’s exactly why Plaiss has students read Cassian, Augustine, Bernard, and William of St. Thierry, Hugh of St. Victor, and Therese of Lisieux; that’s why Ptacek pounds Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Meister Eckhart, and Roger Scruton into the minds of his students: they all contribute to the idea that time is from God and that time is not, as Williams says, a “sharp disjunction we make between labor and leisure,” but a union of thought and action with the divine.

Plaiss and Ptacek are convinced that the treasure of Catholic thought, especially as expounded by monastics and philosophers, is just that: a treasure. And that treasure should not be buried under the excuses of condescension and fad, but dug up, gnawed upon, and consumed by everyone, especially high school students. High school students need more than “I Send You Out.” Before they are sent out, students need to be fed a good meal. What saith the Psalmist? “Taste and see that the Lord is good.”

“

We aim to build community, to pray together, and to grow in Benedictine spirituality.

A few Kentuckians approached me at a Saint Meinrad oblate retreat about three years ago and invited me to their chapter meeting in Versailles. I was a newly professed oblate and was still trying to find a more solid prayerfooting, so I felt it a good idea. A few months later I arrived in the parking lot of St. Leo’s Church. The chapter was not an official chapter yet, and I had no idea what to expect. But on that Sunday afternoon, I entered the school building and was met with Benedictine hospitality. We prayed Vespers together, listened to a presentation, ate some snacks, and socialized a little. I met oblates and novices in my own diocese that night and am extremely grateful.

If you are looking for a chapter, go to the oblate section of Saint Meinrad’s website and look for the heading “Chapters.” Many are listed on that webpage and there is an online chapter available for those areas without a nearby community. For more information on oblate chapters near you, write the Saint Meinrad Oblate Office at oblates@saintmeinrad.edu.

In this issue of the Oblate Voice, we learn from Chapter Coordinator Kerri Banuach about the Lexington Oblate Chapter where I found Saint Meinrad’s hospitality, oblates, and Benedictine prayer life closer to my home.

The Lexington Oblate Chapter just became official in 2024. What was the commissioning ceremony like and what insights did it bring?

As a group I think we were all so excited to finally be commissioned as

a chapter. I remember the commissioning itself being shorter than I anticipated and we had some confusion at first as we started Vespers and then realized that the commissioning happens during Vespers. Our group had been together on and off for a few years, and it was just wonderful to know that the Archabbey was now officially recognizing us as a chapter. It’s been a few months, so I don’t remember the details of the ceremony or Br. Michael’s talk afterwards, but I do remember feeling the weight of the responsibility of the chapter on me a bit heavier than it had been in the past.

How did you become an oblate and did you ever imagine yourself leading an oblate chapter?

I became an oblate in April of 2016 after about a year and a half of study. I was initially invited by a friend who was interested, and she invited me and several others. We were invested as novices together in 2014. I think there were around eight or nine of us then, but only three of us saw it all the way through and became oblates. Fr. Meinrad Brune, OSB, the oblate director at the time, was very encouraging of our group, and we had hoped to form a chapter once we were all oblates. I never expected to be the one to lead a chapter; I was focused on being an oblate to help deepen my spiritual life.

An oblate group existed before the chapter was recognized. When and how did your chapter originate?

Around 2017, a couple of us decided to put out feelers for others who

might be oblates in our area. We planned a gathering on St. Benedict’s feast day and had a good turnout. We attended Mass together and then gathered for a potluck. I think we had about 12 people at that first gathering. There was a group of permanent deacons in our area who also became oblates around that time and that helped expand our group a little. We didn’t do a whole lot after that, but around 2019, we finally decided to start meeting regularly. We started in the fall and met a few times into early 2020, and then the world shut down and we lost our momentum. Coming out of the pandemic, one of our oblates contacted me and said that the priest at her parish invited us to start meeting there. After working out the logistics, we started meeting up again in 2022. We were a small group, but we were starting to see some growth. One of our deacons reached out to former Oblate Director Janis Dopp to get details on how to become a chapter, and we just kept plugging along.

I understand you do not meet in Lexington, but in Versailles. Can you explain how the Bluegrass region and the Lexington Diocese (which is a mission diocese) helped to create such a widespread chapter? How far does your chapter reach? And do you think this diaspora is beneficial somehow in understanding the work of Benedictine prayer?

The Diocese of Lexington has some unique features that make forming a chapter challenging. The diocese covers 16,400 square miles (50 counties) and Catholics make up about

3% of the total population. The Catholic population in the city of Lexington itself is higher (maybe around 12%), but it drops significantly once you get outside Fayette County and the counties immediately around Fayette (fondly called the “doughnut”). Most counties outside of Lexington have one parish, in a few cases there is one parish for two or more counties, and a number of priests split their time between two or more of those parishes. Many of these are small rural parishes. As a result, our oblates come from a number of cities in the Central Kentucky area and a few places further afield within the diocese. We meet in Versailles thanks to the hospitality of Fr. Chris Clay who invited us to meet

at his parish. Most of our members come from Versailles, Lexington, Frankfort, Georgetown, Winchester, and Morehead, while others join us from Liberty, Yosemite, Ashland, and Barbourville. Some of our oblates commit to a two-hour, one-way drive to attend our meetings.

Initially we had wanted to be known as the Bluegrass Chapter as that name more fully encompassed our widespread membership. Upon learning we couldn’t do that, we agreed that the Lexington Chapter made the most sense since it was also the name of our diocese.

I think the benefit of having such a wide geographic group is that we get

to know other parts of our diocese through the people we meet. Getting to pray together and share prayer intentions helps diversify our worldview as well. As we continue to grow as a chapter, I hope that more of our members from other parts of the diocese will share more about their parishes and what makes their neck of the woods unique and special.

How often do you meet and what are your aims for your gatherings?

Our chapter meets about once a month from August through May, except December. We aim to build community, to pray together, and to grow in Benedictine spirituality.

BY DR. JAMES L. PAPANDREA, M.DIV, PH.D Sophia Institute Press, 2023

My bookshelf always seems to have room for a new translation or paraphrase of the Psalms. Dr. James Papandrea’s latest work, Praying the Psalms is far more than another translation. Praying the Psalms isn’t really a complete translation; he covers much of the Psalter but leaves out several Psalms and passages. The real delight of his work though is the what and the why for what he does cover. The subtitle of the book gives us a direction: The Divine Gateway to Lectio Divina and Contemplative Prayer.

Three things make this book stand out from many other translations for me. First, it is not for liturgical use or necessarily even group recitation. It is for personal devotional use, not to replace any other translation. Second, Dr. Papandrea sees a difference between praise and worship on the one hand, and prayer on the other. He generally views Psalms written in the third person more as praise and worship, talking about God’s glory, and what God has done. Psalms written in the second person are more actual prayer that we address directly to God. These are the Psalms he uses in his translation, making personal prayer the focus. And finally, putting this together he follows the parallelism of the Psalms to demonstrate a way to use them as contemplative prayer. Throughout the book for many of the Psalms, he chooses two lines to offer as a breathing prayer. His translation is simple yet beautiful and he encourages the reader to find their own breathing couplets to use for contemplation.

Of course, the Liturgy of the Hours, Psalms, and lectio divina are part of our five duties as Benedictine Oblates. Dr. Papandrea offers a specific technique and model to help us in the contemplatio of lectio divina as we use the Psalms. For the Church at large this meets a real need for personal devotion and drawing closer to God in contemplation. Contemplation can be a bit scary or woo to many unfamiliar with it, but this book offers a way to make it simple and powerful in our seeking out the presence of God in our lives. And I always have room for that on my bookshelf.

One of our three promises as an oblate is stability of heart. We committed ourselves to the monastic family of the monastery of Saint Meinrad Archabbey. We are connected to this particular place, with these particular people, using a particular practice.

As I was going through my novitiate period, I began to reflect upon why I want to commit myself to the community of Saint Meinrad Archabbey. There are many Benedictine communities throughout the world – why Saint Meinrad? To answer that question, I began to reminisce about my journey to be an oblate and how God led me to Saint Meinrad.

Each of us is on a journey or pilgrimage led by God. When we trust God and let Him lead us, we encounter Him and people in new, unexpected, and wonderful ways. We form new relationships and strengthen old ones. As I reflect on my ongoing journey or pilgrimage to God, I realized how much Saint Meinrad Archabbey had played a major role in my conversion story and is still playing a significant role.

My journey began as a youth growing up on a farm in east central Indiana. I can remember going with my parents and sister to visit Saint Meinrad. Two of my dad’s friends in his youth had become monks there, and we would occasionally visit them. I can still remember visiting Fr. Joachim Walsh, OSB, and Fr. Marion Walsh, OSB. There was a sense of peace and holiness when coming to the Hill. Although I must admit, my favorite part of the trip was going to Santa Claus Land. That was long before it became Holiday World.

My pilgrimage with Saint Meinrad Archabbey continued as I spent one week on the Hill for those who were considering the priesthood as a vocation during the summer before my eighth-grade year of school. I remember living in the dormitory with 20 other young men and the common bathroom. I was struck by the sense of community and family that I felt in that experience. It was more than a place. There was a sense of sharing a common purpose and mission. We were on a common journey or pilgrimage together as a community of seekers of God.

After high school, I enrolled in Saint Meinrad College to further discern my vocation. When I think back on this time, I can see how being part of this community at this time in my life played such an important role in my personal, intellectual, spiritual, and social development. I made friendships that I still have today, and the foundation of my spiritual life is grounded in what I experienced in those college years.

The Benedictine model of ora et labora has stayed with me my whole life. I have tried to achieve the balance between prayer and work. I have not always been successful. But striving for a sense of balance and moderation in life has been a model that I have tried to follow. As I was discerning the path that God wanted me to follow, I can remember talking on numerous occasions with my spiritual director, Fr. Gregory Chamberlin, OSB. I still can picture myself sitting in St. Thomas Aquinas Chapel asking God for direction.

Even though I decided that God was not calling me to the priesthood, and I left Saint Meinrad College, the

Benedictine spirituality of the Hill was ingrained into me. Saint Meinrad was part of me. When I became engaged to my wife, Donna, one of the first things we did was take a trip to Saint Meinrad Archabbey. I wanted to share the spirit of the monks with her.

As the years progressed, the spirit of the monks was always with me. When God called me to the permanent diaconate, it was the Permanent Deacon Formation Program at Saint Meinrad that prepared me for that ministry. Here I was again on the Hill. Even though the classes were taught in my diocese, the sense of the community and family of Saint Meinrad was present. I was continuing my journey united with the monks.

Becoming an oblate continued my connection with the community and family at Saint Meinrad Archabbey. During the novice year, we are reminded that we associate with the values of Benedictine life – constant striving to respond to God’s call, poverty of spirit, and obedience to the movements of the Holy Spirit. These values make the stability of heart possible.

We are connected to this particular place, with these particular people, using a particular practice. Our stability of heart is the combination of place, people, and practice. It is staying with the community of Saint Meinrad and continuing the journey together. It is persevering with our chapter community and following the practices of reading The Rule of St. Benedict and lectio divina.

Once the spirit of Saint Meinrad is within you, it never leaves. It is always there guiding and loving us regardless of where we are or what stage of life we are in.

FR. CHRISTIAN RAAB, OSB Monk of Saint Meinrad Archabbey

Recently, I was asked by some friends not accustomed to using the Psalter why it might be to their advantage to take it up in their worship and private devotion. This should not be too difficult a matter to explain, I thought at first. Anyone who has listened to Handel’s Messiah is aware of the long Christian tradition of reading the Old Testament as a book of prophecy about Christ. Surely this would be a good place to start.

Christ in the Psalms

Having studied the history of Christian worship and prayer, I knew well the traditions that sang the psalms in praise of the Royal Son of David, The Lord Jesus Christ (e.g., Psalms 2, 109[110], 131[132]), upon whom had been poured the oil of gladness (Ps. 44[45]:8). How the heart thrills when the Messianic Psalms are sung, especially during Advent and Christmastide!

In the Psalms of trouble and suffering, who could not help but recognize Jesus, the Suffering Servant? On the cross, the psalms of his people provided the words he needed to cry out to his God (Ps. 21[22]), and led him to commend his life and labors into the hands of the Father (Ps. 30[31]:6). No wonder these psalms occur so often during Lent and Holy Week.

And then, how to hymn Christ’s resurrection glory? No finer song than Psalm 117(118) for praising the stone rejected become the cornerstone and celebrating every Sunday as the special day made by the Lord, on which rejoicing and gladness are the order of the day (Ps. 117[118]:24; see also Mt. 21:42, Mk. 12:10, and Lk. 20:17; cf. Acts 4:11 and 1 Pt. 2:7).

Although he did return to the Father’s glory and is now seated at God’s right hand, Jesus did not forget the loved ones who remained behind. The gift of the Holy Spirit in wind and fire at Pentecost attested: I am with you evermore.

Psalter in hand, our Christian ancestors took up the chant on Ascension Day, God goes up with shouts of joy (Ps. 46[47]:6), and longed for his Spirit-gift in their own lives, praying, Send forth your spirit … renew the face of the earth! (Ps. 102[104]:30).

As I was mulling over these, and various other possible ways of responding to the request my friends had made, I noticed, stacked in the corner of my bookcase, some postcards, memories of student years in Rome. Among them, I came across one of the ancient baptisteries of the city, its walls adorned with dazzling mosaics.

There, on the wall opposite the baptismal pool, situated in such a way that, as the newly baptized emerged dripping from the waters, their eyes would immediately fall upon it, was the figure of a youthful shepherd boy. A little lamb was hoisted upon his broad shoulders.

I must show this to my friends and tell them how those early Christians, newly up from the waters upon seeing this wonderful work of art, would remember that it was Jesus who had assured them, I am the good shepherd (Jn. 10:11), and would sing of him to whom their lives were now irrevocably committed:

The Lord is my shepherd … near restful waters he leads me … My head you have anointed with oil … In the Lord’s own house shall I dwell, forever and ever (Ps. 22[23]:1,2,5,6).

I picked up another postcard. This time the scene, from the catacombs, was that of a tiny cavern deep under the street level. Perhaps at one time it had been used as a small chapel. Etched on one of its walls, in red the color of clay, was a small alter. Near it were fish and two baskets filled with loaves marked with crosses. Vines heavy with clusters of ripe grapes were also near. All was ready for a sacred meal. Taste and see that the Lord is good! (Ps. 33[34]:9, cf. 1 Pt. 2:3).

Perhaps my friends would be interested to know that primitive Christians found in this psalm words most suitable to celebrate Christ present among them as they shared the Bread of Angels (Ps. 77[78]:25) and the Chalice of Salvation (Ps. 115[116]:13). Perhaps this traditional communion psalm would find a place in their own commemoration of the Lord’s Supper.

As I considered the matter, I felt sure that these points would be helpful to my friends. And yet, something more was needed. What was it? I began paging through the hymnal they were accustomed to using, and as I did so, it became more and more evident what had to be said about the advantages of the Psalter.

This is what I noticed: like the Psalter, the hymnal contained numerous hymns that praised and thanked God, and many others that recalled the beauty of his creation and extolled his unceasing providence.

Faith and hope in his promises were duly expressed, and the fellowship of Christian believers extolled. Hymns celebrating the mystery of Christ in the Church Year were not lacking either. Indeed, a number of them were beautiful paraphrases of the great Christological Psalms.

Unlike the Psalter, however, there was not one angry hymn in the entire collection. So often we feel the need to pour out our rage to God in prayer. How will the hymnal help us then? Perhaps this is precisely the point at which the Psalter is most valuable for our needs today, and the point at which our current worship books and hymnals fall short. The Psalter is true to life; it accords so accurately with rawness of human experience. It leaves nothing unsaid; no emotion unexpressed.

I knew then that I would have to tell my friends the whole truth about the Psalter, and what might happen to them if they took it up.

First of all, the psalms would expose the pain of living and demand that they face squarely every condition of human suffering. Betrayal by friends (Ps. 54[55]), attacks of enemies (Ps. 55[56]), the unfairness of a world in which the wicked seem to get rewards, and the just, for all their devoted piety, seem afflicted with endless trouble (Ps. 72[73]) – it is all there, in graphic detail.

The ultimate issues of sickness and death receive particular attention:

Spent and utterly crushed, I cry aloud in anguish of heart. (Ps. 37[38]:9)

You have given me a short span of days; my life is as nothing in your sight. (Ps. 38[39]:6)

Take away your scourge from me.

I am crushed by the blows of your hand. (Ps. 37[38]:11)

This sort of prayer disorients life. It threatens security. It hurts! We are frightened.

But it would not be enough merely to expose pain. More is needed. There must also be a response on the part of the believing heart. It must do something with this pain. It must present it to God!

“Here my voice, O God, as I complain!” (Ps. 63[64]:1). These words were frequently to be found on the lips of some of the greatest saints! Curses, complaints, and laments abound in the Psalter. And this is good.

Taking up the Psalter makes a bold statement to the world about the relationship between God and the human family. God cares about everything that is happening in our lives. He cares about all our experiences, especially those we find difficult and confusing. Since the Psalter is his inspired word, it is clear that he expects to hear from us when we are fed up with the

disappointment and suffering of life. Even when we are fed up with God!

Taking up the Psalter makes a bold statement about us, when we sincerely join the prayer of our hearts to the words of our lips, we declare that we have finally decided to stop burying pain deep within, where neither God nor loved ones can reach to help us. We say that we are ready to suffer through our pain and, when the time comes, to get over it and let it go.

Taking up the Psalter holds a promise. Disorientation is not forever:

When I think: “I have lost my foothold,” Your mercy, Lord, holds me up. When cares increase in my heart, Your consolation calms my soul (Ps. 93[94]:18-19).

We are not alone in our trouble; suffering, sickness, and death do not have the final say. Could this be the reason why so many Christians have clung tenaciously to the Psalter for so many centuries? We need desperately to listen to the psalms, to read them and to sing them, alone and together. To scream, to delight, to weep, to pray them again and again until …

My body and heart faint for joy; God is my possession forever (Ps. 72[73]:26).

I know now how I will answer my friends. I will tell them, “If you take up the Psalter, prepare for an ordeal. Get ready to see the mirror image of your own life in the book your hands hold. Prepare to let the tears flow … and the sighs, and the groans. And that will be good.”

Final Oblations

Jeanne Baldwin of Frankfort, KY

Dcn. Daniel Connell of Morehead, KY

Brandon Dassinger of Groun, GA

Stephen Graham of Ashland, KY

Walter Mace of Hebron, KY

Gregory Marx of Huber Heights, OH

Ricardo Montelongo of Houston, TX

Holly Smith of Louisville, KY

Haley Todd of Denver, CO

Mary Jo Zimmer of Carmel, IN

Investitures

Scott Barron of Evansville, IN

Winfield Bevins of Wilmore, KY

Christopher Camp of Owensboro, KY

Nathan Cedar of Prospect, KY

Jennifer Cravins of Danville, IL

Vincente Fidalgo of Covington, KY

David Husk of Beverly, OH

Melinda Husk of Beverly, OH

Emily Kosher of Newark, OH

Keith Mechler of Troy, IL

Aaron Rosales of Louisville, KY

Kaci Rosales of Lousiville, KY

Adrienne Saffell of Versailles, KY

Final Oblations

Robin O’Connor of Jasper, IN

Donna Sigler of Mt. Carmel, IL

James Sigler of Mt. Carmel, IL

Casey Vandenberg of Lansing, MI

Investitures

Elaine Ahmed of Terrace, WA

Christopher Fry of Bath, WI

Tianna Fry of Bath, WI

Brandon Greer of Owensboro, KY

John Knight of Henderson, KY

Matthew Louis of Columbus, OH

Thomas Lucero of Pueblo, CO

Ben McCormack of Atlanta, GA

Emily McCormack of Atlanta, GA

Mary Lynn Meredith of Bloomington, IL

Joseph Pearson of Cannon, KY

Susan Powell of Indianapolis, IN

Mary Jane Sheldon of Downs, IL

Raymond Sheldon of Downs, IL

Lauren Trautner of Menomonee Falls, WI

Nick Trautner of Menomonee Falls, WI

Final Oblations

Miranda Dale of Garrett, IN

Brian Draper of Jackson, MI

Joy Fish of St. Meinrad, IN

Rex Gehlbach of Troy, IL

Susan Hall of Newburgh, IN

William Hall of Newburgh, IN

Susan Isaacs of Lanesville, IN

Martin Jeffrey of Lafayette, IN

Seaira Kowalski of Brookhaven, MS

Fr. Michael Maples of Knoxville, TN

Christopher McClure of Lancaster, PA

Eric Roseberry of West Lafayette, IN

Dominic Salomone of Henderson, NV

James Schaber of West Lafayette, IN

Anthony Tepe of Lizton, IN

Ernesto Yanes of Louisville, KY

Investitures

Katherine Alberts of Louisville, KY

Jon Baker of Tolono, IL

Theresa Becker of Louisville, KY

Karla Cedormann of St. Louis, MO

Amanda Dexter of Culver, IN

Travis Dexter of Culver, IN

Winona Hammerstrand of Young Harris, GA

Kody Johnson of Henderson, KY

Scott Kirkpatrick of Huntington, IN

Melissa Newcomb of Columbus, IN

Celeste Sheets-Eaton of Indianapolis, IN

Chad Templin of St. Louis, MO

Bart Wall of St. Louis, MO

March 1, 2025 Oblate Rites

Final Oblations

Wade Eckler of Chattanooga, TN

Aaron Rosales of Louisville, KY

Kaci Rosales of Louisville, KY

Investitures

Robert Buxton Jr. of Nashville, TN

Donna House of Waddy, KY

Christy Kirchner of Memphis, TN

Melissa Krylowicz of Memphis, TN

Michael Pruitt of Louisa, KY

Bryan Reed of Indianapolis, IN

Joshua Ridgeway of Spring Hill, TN

Michael Riorden of Oakwood, OH

M. Dell Stiner of Memphis, TN

Robert Suarez of Highland, TN

William Toler of Bay Village, OH

Frankie Tucker of Nineveh, IN

Hosted by Fr. Denis Robinson, OSB, Br. Michael Reyes, OSB, and Corinna Waggoner July 21-August 2, 2025 (13 days)