“Let

us consider, then, how we ought to behave in the presence of God and his angels, and let us stand to sing the psalms in such a way that our minds are in harmony with our

(The Rule of St. Benedict, 19:6-7)

The Oblate Voice is published three times a year by Saint Meinrad Archabbey.

Editor: Krista Hall

Designer: Camryn Stemle

Oblate Director: Fr. Michael Reyes, OSB

Oblate Chaplain: Fr. Joseph Cox, OSB

Content Editor: Diane Frances Walter

Send changes of address and comments to: The Editor, Development Office, Saint Meinrad Archabbey, 200 Hill Dr., St. Meinrad, IN 47577, 812-357-6817, fax 812-357-6325 or email oblates@saintmeinrad.org www.saintmeinrad.org

©2025, Saint Meinrad Archabbey

Servant of God Dorothy Day (18971980), the charismatic co-founder and lay leader of the Catholic Worker movement and Benedictine oblate is considered one of the most important and interesting figures in the history of American Catholicism. An early career in journalism, promoting social and political causes, failed relationships, an abortion, and an outof-wedlock child, led Day to a dramatic conversion to the Catholic faith.

In 1933, after praying to God for guidance at the Basilica of the Immaculate Conception; she met Peter Maurin and co-founded the Catholic Worker newspaper that would evolve into a formidable movement of interconnected ministries: serving the poor and marginalized, promoting social justice and peace, advocacy journalism, and encouraging individuals and the Church to embrace a more radical form of Christian living based on the gospels.

Having lived and worshiped for much of her life between the First and Second Vatican Councils, her personal piety was very traditional and formed decades prior to Vatican II. However, she fully embraced the Second Vatican Council as key teachings affirmed the social activism, lay leadership, and apostolates the Church was seeking to encourage in Lumen Gentium, Gaudium et Spes, and Apostolicam Actuositatem. Her cause for sainthood is under review in Rome.

I was first introduced to Dorothy Day years before I was an oblate. Back in the early 2000s, I had begun a deep

dive into my faith which led me to intensive reading and beginning to make annual retreats at the Abbey of Gethsemani — home to famous Trappist monk, Thomas Merton. During this early part of my journey it was recommended I read The Life You Save May Be Your Own, a nonfiction exploration by Paul Elie about the lives and interrelationships of four influential twentieth century Catholics — Thomas Merton, Walker Percy, Flannery O’Connor, and Dorothy Day.

Prior to reading the book, I had heard of her but did not know much about her. Truth be told, at the time, my interest in the book was more about Thomas Merton than it was about Dorothy Day. But I read it all and came away with a vague understanding that both she and Merton were living by The Rule of St. Benedict, albeit one as a monk priest, the other as a lay woman leading a dynamic national apostolate.

Several years would go by with my annual Gethsemani retreats, spiritual reading, and learning more about monasticism while being increasingly drawn to it, when I awkwardly asked then former abbot of Gethsemani if there was a way for someone like me to affiliate with the abbey. He nicely but flatly stated “no” and then pointed me to Saint Meinrad Archabbey where I would later meet a smiling Fr. Meinrad Brune, OSB, who mentored me into oblation and all things Benedictine.

I entered into a two-year novitiate where I began lectio divina, Liturgy of the Hours, and read extensively. During this period, I began reading about famous oblates in an effort to visualize myself in the vocation. It was

then that I was reintroduced to Day, and I read her spiritual autobiographical classic The Long Loneliness that has echoes of St. Augustine’s Confessions. I found her personal story captivating and the early development of the Catholic Worker, the movement she founded with Peter Maurin, inspiring. With some Benedictine understanding under my belt by then, I could see where the foundations of the Catholic Worker emanated from The Rule — commitment to hospitality, prayer, work, liturgy and the corporal and spiritual works of mercy.

A decade ago, during a tumultuous time in my life, I relocated from Ohio to Nevada for a career opportunity. Early on, I was seeking ways to plug into a place where I knew no one. I discovered there was a Catholic Worker house nearby, and one Saturday I ventured there and introduced myself.

To this day, I am there most Saturdays serving the homeless. It was there that my oblate vocation bloomed, and I became fully aware of the legacy of Dorothy Day and the importance of her cause for sainthood for Benedictine oblates, the Church, and the world. It also had a profound impact on my desire to perform the corporal and spiritual works of mercy, which has recently led to my apostolate as a Catholic chaplain.

As Benedictine oblates, we are called to live The Rule of St. Benedict in the world, integrating its rhythm of prayer, work, and community into the fabric of our daily lives. We are laypeople whose hearts are monastic even if our homes are not cloistered. In reflecting on the life of Dorothy Day, I find in her a kindred spirit whose witness

resonates profoundly with Benedictine values. Her life as an oblate speaks to us as oblates, inviting us to see our own path more clearly through the lens of her witness. Here is why…

Dorothy Day discovered her vocation on the streets of New York City during the Great Depression. The Catholic Worker houses of hospitality were not cloisters, but they were holy places. The daily schedule included Mass, praying the Divine Office, manual labor, and meals shared with the poor. Day did not do these out of some abstract idealism; rather, they emerged from a vision shaped by the Gospel, the Church’s social teaching, and her own spiritual reading — much of which included The Rule of St. Benedict, the Desert Fathers, other monastic sources, and the spirituality of saints she was especially devoted to, like St. Francis of Assisi and St. Thérèse of Lisieux. Though she wore no habit, and made no formal vows in a monastery, her life was thoroughly vowed — vowed to Christ in the poor, to peace, and to the discipline of community life. Her commitment to Ora et Labora — the foundational balance of prayer and work, was unmistakable. Amidst the suffering of the Great Depression, the ministry of the Catholic Worker — feeding the hungry, advocating for justice, offering hospitality — was always undergirded by prayer. “We feed the hungry, yes,” she said, “but we also try to see Christ in them. That is the heart of it all.”

Just as St. Benedict outlined a rule to create a “school for the Lord’s service,” Dorothy Day envisioned the Catholic Worker as a community where the Gospel could be lived radically and concretely.

Stability is one of the most countercultural vows in the Benedictine tradition. In a world that values mobility, change, and novelty,

the Benedictine chooses rootedness — rooted in place, in community, and in God. Dorothy Day embodied this in her own way. While she traveled often for speaking engagements (many times to Saint Meinrad Archabbey) and to support various Catholic Worker communities, her spiritual home remained the original Catholic Worker house on Chrystie Street (and later, at Maryhouse and St. Joseph House). There she lived, prayed, and served for decades and ultimately died. She was also a professed Benedictine oblate at St. Procopius Abbey in Lisle, Illinois, and committed to that monastic community — a place I have visited and prayed with the monks. More deeply, Day was stable in her faithfulness to Christ and to the mission she discerned. She did not waver when misunderstood by the Church or society. She remained steadfast through criticism, poverty, and personal suffering. As oblates, we can look to her as a model of how to live stability not only geographically but spiritually: grounded in the Word, in sacramental life, and in the daily, unglamorous fidelity to our commitments. Her life also reflects the kind of communal stability that Benedict describes in his Rule. The Catholic Worker communities of her time often lived under great strain, with difficult personalities and limited resources. But, like a monastic community, they did not flee from one another; they stayed, struggled, and grew. Day once remarked, “We have all known the long loneliness, and we have learned that the only solution is love and that love comes with community.”

In Chapter 53 of The Rule, St. Benedict writes, “All guests who present themselves are to be welcomed as Christ.” This is not mere piety — it is a concrete directive that challenges us to recognize Christ in the stranger, in the one who disrupts our comfort and

asks for our presence. Dorothy Day lived this radical hospitality every day. Her houses of hospitality were often overcrowded, underfunded, and turbulent. But they were sacred spaces where the poor were treated with dignity. Day insisted on a personalist approach: Each person mattered. She learned their names, she listened to their stories, she opened her heart even when it cost her sleep or her personal safety. What makes Day’s hospitality Benedictine in spirit is not merely the act of feeding or sheltering, but the reverent attention to the person before her. Like the doorkeeper of the monastery, she knew that the face of Christ appeared not just in the celebrant at Mass, but in the man who came in drunk, the woman escaping violence, the elderly who had been forgotten. For oblates, this challenges our own sense of hospitality. We are called to open our hearts, our homes, and our lives in the spirit of Christ.

Silence

Dorothy Day lived a life in the world, often in the thick of political protest and social tumult. Yet she was deeply contemplative. She wrote often of the importance of silence, of inner recollection, of “making a room” within us for God. As oblates, we are encouraged to cultivate an inner monastery — a space within where Christ dwells. Day knew this space well. She wrote of “cultivating the interior life,” even amid the noise of the city and the cries of the poor. In this, she is a model for oblates who live busy lives but seek to maintain a contemplative spirit. In her diary, she reflects: “We must practice the presence of God. We must go about our work as though everything depended on us and pray as though everything depended on God.”

This echoes St. Benedict’s insistence that everything in the monastery be done as if it were the work of God — whether doing the most mundane daily

chores and tasks or praying the Psalms. Day’s life was a seamless integration of action and contemplation, of prayer and presence. Ora et Labora

The Rule opens with the exhortation to “listen carefully … with the ear of your heart.” Dorothy Day was, in her own way, a woman of deep obedience rooted in love and truth. She was obedient to the Gospel, to the Magisterium, to the needs of the poor, and to her conscience, formed by faith and prayer. This fidelity is not unlike the obedience St. Benedict describes — an obedience grounded in humility and love, not coercion. As fellow oblates, we, too, are called to listen deeply: to Scripture, to our communities, to our inner lives. Day’s example reminds us that true obedience is not passive, but active — a choice to remain centered in Christ and guided by the Spirit, even when the path is unclear or difficult.

Dorothy Day’s commitment to nonviolence, pacifism, and peacemaking places her within the prophetic tradition of the Church. She opposed every war, even World War II, when it was profoundly unpopular to do so. She was arrested numerous times for protesting nuclear weapons, military drafts, and unjust labor practices. Toward the end of her life with the Roe v. Wade decision affecting American culture, Day came out publicly as decidedly pro-life. That

she had embraced the entire pro-life teachings of the Church, over time, reversed my thoughts about capital punishment, which today I am firmly against, nor do I choose to own or use a gun, even if the law allows it.

oblates, we may not stand on picket lines like Day, but we are called to be peacemakers in our families, parishes, workplaces, and world. Day shows us that peace is not passivity but courageous love. Her refusal to endorse violence in any form embodies a Gospel-centered conscience.

This radical commitment to peace is not foreign to Benedictine life. The Rule instructs monks to “seek peace and pursue it.” Benedictine monasteries have historically been places of reconciliation and quiet witnesses in times of violence and upheaval. As

Dorothy Day died in 1980, but her witness feels more urgent than ever. In an age of cultural polarization and spiritual disconnection, her integrated life of prayer and action is a guidepost. She reminds us that as oblates, we are called to a life of prayer, but also engagement with the world. Her cause for canonization is ongoing, and she is presently designated a “Servant of God.” During the 2018-2021 period, the final part of the Diocesan Inquiry phase of the process compiling her life story and voluminous writings (40,000 pages, private and public) were prepared. Due to my relationship with the Catholic Worker and being a Benedictine oblate, I was honored to be invited, along with others, to help transcribe parts of her personal diaries that had never previously been published. I traveled to meet officials of the Archdiocese of New York who were leading the effort and I made a solemn oath to “fulfill faithfully the duties entrusted to me and maintain the secrecy of office.” I also had an opportunity to visit the St. Joseph House and Maryhouse complex in lower Manhattan — which is the heart of the Catholic Worker movement. Along the way I have been introduced

to Day’s granddaughter Martha Hennessy who I now consider a friend — and who, like her grandmother, is also a Benedictine oblate.

In 2022, the Dorothy Day Guild was informed by The Vatican that all necessary documentation had been received to proceed with a positio — a detailed summary of Day’s life prepared for review by theologians, bishops, and cardinals who assess her life and heroic virtue and ultimately present their findings to the Pope. In November of 2023, it was announced

The Long Loneliness - Dorothy Day

that Monsignor Maurizio Tagliaferri had been appointed by the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints as the relator for Day’s cause. While this phase is not yet complete, there are rumblings that Day may be named venerable sometime in the near future. Should this happen, what will make way for her canonization are two confirmed, verifiable miracles. The first would make her a “Blessed,” the second, a “Saint.”

Dorothy Day reminds us that our Benedictine oblate vocation can

From Union Square to Rome - Dorothy Day

Dorothy Day: An Introduction to Her Life and Thought - Terrence C. Wright

All the Way to Heaven: Selected Letters of Dorothy Day - Robert Ellsberg

The Duty of Delight: The Diaries of Dorothy Day - Robert Ellsberg

All is Grace: A Biography of Dorothy Day - Jim Forrest

The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage - Paul Elie

flourish anywhere. On a farm, in the city, in a soup kitchen, in a jail cell, in a pew — among the single, married, divorced, or widowed. Her life is both inspiration and invitation. She calls us to integrate prayer and work, to remain stable in love and truth, to extend hospitality to Christ in the stranger, to listen with the ear of the heart, and to seek peace always. May we, like her, strive to be faithful not necessarily in grand gestures, but in small acts of love. And may the same Rule we follow as she did, lead us, as it did her, to Christ.

Ask Dorothy for Intercessions: https://dorothydayasaint.info/prayer-requests.html

Join the Guild: www.dorothydayguild.org

Experience her Legacy: www.catholicworker.org

Be on the lookout for future communications from Oblate Director Fr. Michael Reyes, the Oblate Council, and your chapter leaders for programs encouraging intercessory prayer to Servant of God Dorothy Day in support of her cause for sainthood.

In 2023, I attended my first oblate retreat. One day for lunch as I walked out of the serving line into the dining room, I noticed a young fellow sitting by himself and asked to join him. As I sat down, we introduced ourselves, and I was curious why he was at Saint Meinrad as I had not seen him in any of the conferences.

He told me that he sometimes takes personal retreats to the Archabbey but has never taken an organized retreat. He finds solace here, and it helps clear his mind. As we talked, he told me that

he normally stays away from others, but today he really wanted someone to talk to and was glad to sit with me. We shared a lot of vignettes between us. He never fully disclosed what was on his heart other than he was about to begin a large project, and he was trying to hear God’s plan. I told him that my spiritual director had recently explained to me, when I revealed that I was feeling different about my plans, that God was peeling back the layers of the man I made to show me the man He made.

That struck a note with the young man, and by the end of our lunch we had opened our hearts to one another. We were both holding back tears of joy (a little unsuccessfully, I would add). In the time since then, we have not spoken, but we often text little reminders that we pray for one another. I want him to know how much that time together has blessed and touched me. As St. Paul said, you never know when you may spend time with an angel!

JENIFER SCHREINER Oblate of Valparaiso, Indiana

“You are my hope, Lord, my trust, God, from my youth.” Psalm 71:5

As an oblate of Saint Meinrad, I have developed an awareness of how the routine of daily prayer, in praying the Psalms, strengthens the relationship I have with God. My faith in God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is always expanding in many ways as a result of this daily commitment to praying the Liturgy of the Hours. Prayer demonstrates and deepens my love for God, and it leads my heart and mind to know with certainty that I can place my hope in God.

The verses of the Psalms lead us with vivid descriptions of the hope of God’s people. This hope is not a wishful optimistic feeling, but a conviction of the goodness of all that God creates, here on earth and in the heavens. It is a quiet but strong way of living and looking at all things, both good and bad, with a realization of promises that are greater than this world. I do believe I bring hope to others when I pray with them, and I believe that both individual and communal prayer can bring hope to the entire world from wherever it is prayed.

Prayer builds our hope and trust in God. However, we must choose this hope and cultivate it. Hope is not automatically instilled into our decisions and having hope sometimes means praying for fortitude to sustain us. Hope seeks to love and to find opportunities for goodness in the world. I see how positive change is driven by hope, a hope that seeks to do better, to love more, to help and heal.

When we seek love and goodness, inherently we seek God and all that He is. Hope, like love, has an infinite measure and infinite power. I place my hope each day in you, Lord. Amen.

FR. ADRIAN BURKE, OSB Saint Meinrad Archabbey

The Solemnity of the Most Holy Trinity

First Reading: Proverbs 8:22-31

Second Reading: Romans 5:1-5

Gospel: John 16:12-15

If the two angles of one triangle and the side included between them are equal to the two corresponding angles and the side included between them of another triangle, the two triangles are congruent.

The radius of a circle is always perpendicular to a chord, bisecting the chord and the arc.

An angle inscribed in a semi-circle is a right angle.

These are a few of the axiomatic principles involved in Euclidean geometry — a branch of mathematics I enjoyed when I was in high school. There was something truly satisfying about geometric proofs — the logic, the consistency — it was fun, and I experienced a sense of pleasure when I succeeded in “proving” a geometry problem; the more difficult the problem, the more satisfaction I enjoyed. I actually felt beauty in it! Like music, when a dissonant, unstable sounding chord resolves to a consonant major chord. Looking back, I would say that geometry took my young mind to a whole new level of awe at the relational order of things. Still, there is a whole lot of dissonance in the “City of Man” — always has been, always will be until we reach the City of God.

We humans love to figure things out. Even those who don’t enjoy math enjoy solving problems — mechanical difficulties like broken car engines, or

how am I going to hit this golf ball so it lands on the fairway, or difficulties like conflict with one’s spouse or coworker, or a teenaged daughter or son, or how to talk to my preschooler about death. We feel more secure when we think we’re “right.” When we “get it,” we feel less vulnerable, and when we feel we’re understood, when others “get” us, we feel connected and safe.

The Book of Proverbs provides us with a long list of sayings that purport to reflect the Wisdom of God — divinely established axiomatic truths that we can use to figure things out and solve the problems life throws our way in a world where things don’t always seem safe. The resolution to many of life’s problems relies on axiomatic truths of our faith — for example that human beings share an innate dignity that justice demands I acknowledge and respect; that I am not God and I don’t and can’t know it all; that I can’t succeed alone apart from the support of a community; and that love is more powerful than force … along with many other axiomatic truths that faith proposes.

The spiritual life is about learning to rely on God’s gift of wisdom to better succeed at being who and what God intends us to be by loving others as God first loved us; by loving our neighbor “as I have loved you,” to use Jesus’ way of saying it.

Faith proposes that God is One — indivisible unity and simplicity — and that God lives in unapproachable light, that God simply cannot be grasped by our mortal understanding, much less comprehended, as if God was a mathematical proof. God cannot be proven — and dissonance is always

with us, things aren’t always OK, but that’s precisely why God gives us faith.

Faith, and I rely here on St. Augustine’s understanding of it, is about trusting God’s goodness. Faith is a disposition to believe in God’s goodness despite our inability to prove God, or understand God, much less comprehend God and have God or the situation all figured out. Faith is not about certitudes; it’s about trust, reliance, and belief despite a lack of certitude.

Christians believe the Hebrew concept of Divine Wisdom refers to the second person of the Holy Trinity. We read in the book of Proverbs that Wisdom is the beginning of God’s ways. Jesus said of himself, “I am the Way.” These human words from Scripture enable us, to some extent anyway, to describe Divine Being, but they don’t define God.

The sun, the stars, the moon, the heavens and the earth, all spring from God’s Wisdom. God conceives reality from within, and speaks outwardly what is to be — so, in Genesis we have God speaking: Let there be light, and there is. Let there be earth and sky, and it happens. Let there be humankind made in our image and likeness, and here we are. God’s Word is effective and true, it cannot fail to realize what it commands. God does what He wills, is how the Psalmist renders it.

But these biblical and theological concepts aren’t really at the heart of today’s solemnity. So, let me turn more in that direction, to what really matters.

Two modern theologians whose writing I respect very much — Catherine LaCugna and Dianne Bergant — both

say in their distinct ways that faith isn’t about understanding or comprehending God’s self. Faith is a God-given capacity to see, to experience, and to believe who God is as “God for us.”

That’s Catherine LaCugna’s favorite term for who God is — God for us.

We know who God is by seeing and experiencing how God is active and moving in relationship with the Creation; seeing and believing what God has done for us and where God has been active in our lives and in the history of God’s people; realizing when God visits us, even in the dark places of our suffering, being with us as a kind of inflection point, to use another mathematical term, turning the course of our own personal history and the world’s history toward its final end through, with, and in Jesus of Nazareth, a Galilean Jew who lived two millennia ago in ancient Palestine.

God is God for us, and for our redemption — God is Savior and Advocate.

The readings for this Mass reflect the three persons of the Holy Trinity. In the Book of Proverbs, we read about the God of Creation, whose wisdom, delights in humankind. This is further highlighted in the Psalmist’s exuberant praise of the Creator, the one Jesus called Father: When I behold your heavens, the work of your hands, the moon and the stars which you arrange — what is humankind that you should be mindful of us, mortal humanity that you should care for us?

Paul’s letter to the Romans reminds us that by participating in the faith of Jesus, our hearts are opened to the gift of salvation. In Christ, God’s Son and gift of God’s self, we are justified and have peace with God, because the love of God has been poured into our hearts.

This last thought provides a perfect segue to the Gospel where Jesus promises to send the Spirit of Truth who will lead us to all truth, and who, furthermore, will enable us to know what’s coming so we can discern how to respond to what life throws our way, individually or as family or society.

But at the heart of today’s solemnity is the most unexpected and perhaps the hardest thing to accept about the Holy Trinity. It’s this: that God is revealed by Christ and affirmed by the Spirit as God who serves! God is for us because God serves us. It’s counter intuitive because we fixate on serving God, but it’s what Jesus himself said, “I came to serve, not be served.”

God is God for us, and for our redemption — God is Savior and Advocate. “

Through Jesus’ proclamation and teaching, through his healing ministry, and his most substantive act of service, his passion and death, Jesus reveals the true character of God as selfless love and self-giving goodness.

Our task is to allow God to be for us by consenting to God’s love and sharing that love with others. In this way, we become who God intends us to be — agents of God’s love and mercy for others. So, first, we must be God’s Church, Christ’s embodiment in a world that, once again of late, is showing itself to be anything but a realm of love and compassion.

To do that we must allow God’s spirit to kindle the light of Christ within and

among us, even in the darkness of our suffering, so as to love as Christ loved us by surrendering our own needs to the common good; dying to what is “I” to be alive to the “We” of Christ who dwells in and among us, his body — because God is for us, not just for me!

And yet, and yet, it is all very personal. We must hold two seeming contraries together, realizing that we cannot discover our wholly unique individuality except in the context of community. Only from within community can we find our way to being an image and likeness of the Divine Communion as agents and instruments of God’s love for all.

Christ, if we consent to it, redeems us from the selfish “I,” a disintegrated, fear-driven self. Dianne Bergant uses Jesus’ image of Living Water, God’s grace ready to flow should we turn on the spigot! Like water from a tap, the Spirit is available, but we must consent to its flowing in and among us — to consent as Mary did that day in Nazareth, to give birth to Christ.

By our consent to God’s grace, allowing God to serve us by being for us, we can become what Christ has sent us into the world to be: leaven for a world mired in sin; hope for a people immersed in discord, fear, and violence.

Through, in, and with Christ, God serves the creation as its Maker and its Redeemer. Through the Divine Spirit poured out, God serves us as unifying peace and selfless love, providing wisdom, knowledge, and understanding, so that, consenting to the Spirit’s heavy lifting in and among us, we can bear fruit that lasts — gifts to bring into God’s presence when, at last, we see God face-to-face! Trust in the promises of God’s Word — a Word that can neither fail, nor disappoint.

ARCHABBOT KURT STASIAK, OSB Saint Meinrad Archabbey

Editor’s note: This is the fourth and fifth article in a five-part series.

I offer a final comment as regards the tendency of mismanaging the means of our common life. Each of us wants to do well, to be a good and faithful pupil in the “school for the Lord’s service” (RB Prologue, 45). Most of us also want to live with people with whom we can become friends and grow in intimacy, and many of us throughout the course of our years have acquired and developed skills that have allowed us greater emotional and psychological health. Few of us relate to people now as we did when we were in high school or college, and the change is usually for the better. At times, we can take justifiable satisfaction in the healthy, sturdy relationships with which we have been blessed.

Again, there is everything right about this, as true friendship can contribute mightily to our spiritual quest for God, as well as to our own psychological health. The hazard is that, at times, we may equate our skills or our success in building relationships or the joys stemming from those relationships with the true peace that only God can offer and that can be found in Him alone.

Our friendships with one another should bolster, not replace or stunt, our desire to continue seeking and developing that which we will never find completely in our community or anywhere else: that perfect communion with God that casts out all fear (see RB 7:67).

Let us, by all means, attend to building healthy relationships. But let us not equate too quickly or confidently our

success or progress in experiencing the real and legitimate benefits of our friendships as an indication that our search for God is progressing as smoothly or is enjoying the same depth.

The anchorite: “Hermit, come out of yourself.”

Benedict offers only a passing description of the hermit in his first chapter, although it is clear why he holds this kind of “good monk” in such esteem:

“Thanks to the help and guidance of many, they are now trained to fight against the devil. They have built up their strength and go from the battle line in the ranks of their brothers to the single combat of the desert. Self-reliant now, without the support of another, they are ready with God’s help to grapple single-handed with the vices of body and mind” (RB 1:4-5).

The radical solitude of the hermit appeals to few of us and yet, as we discussed above, solitude is essential even for cenobites. We, too, must retreat regularly into the solitude of our cells so as to prepare and strengthen our hearts in private for the One whom we seek in common. While solitude is the distinctive feature of the hermitical life, it is for all of us one of the right deeds we must practice and pursue.

At times, however, our tendency is to pursue solitude, one of the right deeds of monastic life, for the wrong reason. These are times when we find it especially difficult to live in

community, except in the strict physical or geographical sense. While all who partake of bed, board, and breakfast under the same roof are susceptible to the trials and frustrations of living in common, at times, particularly as the years and frustrations mount, Benedict’s injunction to “[support] with the greatest patience one another’s weaknesses of body or behavior” (RB 72:5) may seem well beyond our means.

Many times we can identify quite easily the root of our pain: personnel assignments not to our liking that have been made, or a desired, personal assignment that was not; disillusionment as to the community’s direction and leadership, or disappointment in our perceived lack of such; an over-emphasis by some on the externals of the life (which we find stifling), or the apparent indiscriminate shedding by others of identity-symbols and traditional practices (practices and symbols we continue to find significant and inspiring). At other times, however, the pain of disillusionment and disappointment seems to have burrowed more deeply into our souls.

We feel the community has changed the rules since we entered, or that the community is following just about any rule except that of its founder. Or, perhaps, we feel we have invested our entire lives in the place and continue to do so, while others seem to us to be half-committed at best. It may seem as though our community has for too long been operating according to the “30-70 principle” (in which 30 percent of the confreres — a group in which we

ordinarily place ourselves! — do 70 percent of the work) and, as we look around at those surrounding us in church or in the common room, we wonder how many actually left the community years ago — but just haven’t gotten around to packing their bags.

In our better and stronger moments, we deal with this pain directly. We turn to our private and common prayer and try to attend to the private (and sometimes, public) needs of those with whom we live. We strive to offer others our patience and compassion because they need this of us, and we try to avoid rashly measuring the commitment and sincerity of others by remembering that whatever spiritual, psychological, and emotional strengths we might legitimately claim in the present are, in no small part, dependent upon our blessings in the past. And we readily agree that the one thing about monastic life we can always count on is that, patiently or not, we will indeed share one another’s weaknesses.

At other times, however, the frustrations build up to such an extent that simply living in the community seems an excessive burden in itself. When this feeling persists over a period of time, we can significantly change the way we think about and approach the common life and the confreres with whom we share that life. Interest in the common good lags, as does interest in the lives of our confreres. No longer merely disillusioned and disappointed, we find that our hearts just aren’t into the community anymore: we have become, in a real sense, disheartened, and our tendency is to retreat further into ourselves and away from our confreres. The longer this continues, the more we become a hermit unto ourselves: we keep the community’s mailing address as our own, but we spend ever more time in the psychological, emotional, and spiritual hermitages into which we have moved.

When done under the circumstances I have outlined, our regular retreating into this hermitage is not the quest for solitude of Benedict’s hermit: for this search for solitude is rooted in the feeling that, since I’m the only one who knows what’s going on here (the only one who is really serious, who really wants to live the life...), I must separate myself from the faults and failings and follies of community life. When this is the case, it is not solitude we seek but isolation: isolation from the imperfections of those with whom we live. And hidden just below the surface of that isolation is the misguided belief that we are self-reliant (a belief St. Benedict’s hermit would find inconceivable).

There is a kind of pride and arrogance here, as there is also a most unfortunate irony. Becoming ever more comfortable in our withdrawal and isolation, we might well achieve some success in protecting ourselves from the weakness of our confreres; but we also effectively isolate ourselves from whatever strengths they might have that would benefit us. What they can offer us we will not accept and, as time goes on and we continue to fortify our self-enclosure, what they could offer us they will not. Were they stronger, they would see through our protective (and often fearful) isolation and continue to offer their support and concern nonetheless; but were we truly wise (and could we here without guile say: “were we truly seeking God on His terms and not our own?”), we would recognize that even those whom we judge to be weaker than us can teach and lead us.

Our self-constructed spiritual and emotional hermitages may serve each of us well, but they serve our confreres not at all. And this seems the fundamental flaw when, disillusioned by the weakness of others and disheartened by what may have once been great expectations, we seek solitude, a necessary and right deed of

monastic life, for the wrong reason. We may continue to seek God and feel that, removed from the distractions of the community and left to our own devices, we are making progress. But is it not difficult to reconcile a consistent attitude of impatience and arrogance, of pride and disdain, toward those with whom we have promised to live as confreres with progress and growth in our relationship with God?

As should be clear from my previous remarks, I do not suggest we should seek to be close to everyone in our community, nor do I hold that an intimate friendship with a confrere is a prerequisite for union with God. I do say, however, that we do well to heed the numerous scriptural injunctions that testify that our relationship with our brothers and sisters and our relationship with God are not two separate, independent choices, but are two aspects of our life that complement and perfect each other.

Moreover, while Benedict says nothing in his Rule of friendship, he consistently emphasizes that all confreres are to be treated — and are to treat one another — with respect and genuine Christian love. Unlike friendship and intimacy, respect and fraternal charity are not occasional gifts experienced in community but are legitimate expectations and rightful demands each confrere may make upon the other.

The last temptation is the greatest treason: to do the right deed for the wrong reason. Cenobites are “those who belong to a monastery, where they serve under a rule and an abbot.”

“Thanks to the help and guidance of many ... [hermits] go from the battle line in the ranks of their brothers to the single combat of the desert.” May the cenobites be firmly committed to the common life, and may the hermits find the solitude for which they long. May we strive to keep the characteristic features of both in balance, that we may attend to those around us and seek the

solitude we must have — both of these, “right deeds” of religious life — for all the “right reasons.”

“There are clearly four kinds of monks.” We are most interested in the first kind of monk Benedict identifies, the cenobites, for it is their way of life under Benedict’s Rule that we have as our daily guide. And guidance we do seek and need. For one of the first discoveries we make is that the “road that leads to salvation” is, indeed, “narrow at the outset.” And the trials and temptations, the obstacles and the traps along that road, are often as subtle as they are numerous.

Using Benedict’s categorization of “four kinds of monks,” I have considered in this series four obstacles to seeking God in the monastic life: four tendencies that can recur regularly in our lives and so weaken us in our “battle for the true King, Christ the Lord” (RB Prologue, 3). The intense disdain with which the sarabaites approach obedience to a rule and an abbot may be foreign to us, but that we often have difficulty in surrendering our wills to the wisdom and experience of others so as “to try them as gold is tried in a furnace” may strike closer to

home. Similarly, while we seldom “spend [our] entire lives drifting from region to region” as do the gyrovagues, our spiritual lives are not without their own procrastinations, allegedly urgent distractions and aimless wanderings.

That men or women can pray, work, and live together is not only an obvious characteristic of the cenobitic way of life, but is also that which first attracted — and which continues to hold — many of us to that life. To our community and to our confreres we are committed. But as we try to do the “right deeds” that contribute to the spiritual, psychological, and emotional strengths of our common life, at times we can allow those right deeds to take on a life of their own. Committed to and interested in the people with whom we live, our search for God in community can take second place to our search for friendship and intimacy in community, and what is clearly a fine means for carrying out the prayer and work of God becomes an end in itself. From another perspective, our commitment to the place or the people can waver as the years and frustrations accumulate, and so we may begin to construct our own spiritual, psychological, and emotional

hermitages: hermitages in which we seek solitude not as a means of attaining greater union with God, but as a protective isolation from those whom we have pledged to serve and support “with the greatest patience ... weaknesses of body or behavior.”

Reflecting upon Benedict’s “four kinds of monks,” then, provides us with a regular opportunity to examine our motives, our methods, and our conscience as to our progress “in this way of life and in faith” (RB Prologue, 49). Avoiding the obvious vices of the sarabaites and gyrovagues, we must also be on guard against the subtle tendencies underlying their misconduct. Surrendering our wills that we may be tested, let us resolve to avoid what we must and go ahead and do in the present what is necessary for the future. Similarly, as we foster within our hearts zeal for the common life and love for solitude, let us take care to do these “right deeds” for the “right reasons.”

Let us bear with and carry one another. Let us be friends with some if we are so blessed, but confreres to all as we have pledged. And “[l]et [us] prefer nothing whatever to Christ, and may he bring us all together to everlasting life” (RB 72:11-12).

What if the secret to a soul-nourishing creative life lies not in moments of inspiration, but in sacred routine?

The French novelist Gustave Flaubert understood this paradox when he wrote to Irish socialite Gertrude Tennant: “Soyez réglédans votre vie et ordinaire comme un bourgeois, afin d’être violent et original dans vos œuvres.” Translated: “Be regular and ordinary in your life like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your works.”

The idea that extraordinary creativity can flow from ordinary discipline pulses at the heart of Benedictine discipleship. As a poet and musician, I’ve discovered that The Rule of St. Benedict doesn’t constrain my creative life; it is the soil in which my creativity can flourish.

You may be thinking, “I’m not an artist,” but I’m betting you engage in some semi-regular creative activity like writing, painting, sculpting, building, performing, knitting, crafting, cooking, or something else.

You have an opportunity to forge this creative part of your daily life into something magnificent: a Rule of Creative Life that can transform those contemplative and expressive moments into a powerful spiritual practice.

The Foundation: Your Personal Rule of Life

In Catholic and Anglican traditions, a Rule of Life provides the spiritual framework that anchors our daily practices and disciplines. It regulates our days through spiritual formation,

accountability, balance, and integration of our faith and life.

This ancient wisdom originated in the third-century deserts around Israel, where Christian monasticism first emerged. While early Rules from St. Pachomius, St. Basil, and St. Augustine laid crucial groundwork, it was The Rule of St. Benedict in the sixth century that provided a sustainable and scalable spiritual grounding that has thrived across its 1,500-year existence.

At Saint Meinrad Archabbey, oblates are offered a Personal Rule of Life rooted in The Rule but adapted for our unique vocational calling in the world. Here’s the framework from our Benedictine Oblate Companion binder:

· Pray Morning and Evening Prayer daily.

· Practice lectio divina as part of your daily routine.

· Create space for silence in your life.

· Treat your family and daily work as your main Christian ministries.

· Be a contributing member of your parish or church community.

· Treat physical objects and the environment with care and reverence.

· Serve others with consistent patience and care.

· Read from The Rule of St. Benedict daily.

· Pray for vocations to Saint Meinrad Archabbey.

· Engage in an annual personal evaluation of your own keeping of the promises and duties.

Now imagine channeling this same intentional structure into a regular creative rhythm.

Fred Rogers of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, New York Times street fashion photographer Bill Cunningham, painter and illustrator Hank Virgona, poet Emily Dickinson, and music producer Rick Rubin are not Benedictines, yet all share creative lives governed by stability, fidelity, and obedience.

The genius of The Rule is that it adapts brilliantly to any disciple’s circumstances and calling. The three pillars of Benedictine life — Stabilitas (stability), Conversatio (fidelity to ongoing transformation), and Obedientia (obedience through deep listening) — are fertile soil for a creative practice.

Let’s explore how each core value can be translated into principles for a personal “Rule of Creative Life.”

Treat your creative practice as a sanctuary.

Claim your sacred space and time. Commit to a consistent creative schedule and workspace, treating this practice as a holy routine rather than occasional hobby.

· Build your creative monastery. Cultivate genuine community with fellow creatives through regular

gatherings, discussion groups, or collaborative projects. Your creative life thrives in relationship, not isolation.

· Create powerful rituals. Begin each creative session with intention — light a candle, play specific music, offer prayer or contemplation. These small acts signal to your soul that something sacred is about to unfold.

Serve the common good. Prioritize your artistic community’s flourishing over individual ambition. Support other artists’ work generously.

· Welcome constructive challenge. Establish systems for giving and receiving feedback, viewing criticism as community care rather than personal attack.

Embrace the necessary tension of constant evolution.

· Refuse creative stagnation. Challenge yourself to evolve your craft continuously rather than settling into comfortable but lifeless patterns.

· Practice courageous humility. Honestly assess your current abilities

and remain hungry to learn. True mastery begins with acknowledging how much you don’t yet know.

· Let your voice mature. Allow your artistic expression to change and deepen rather than clinging to past successes or familiar styles. Your best work may be radically different from anything you’ve created before.

· Grant others permission to grow. Don’t trap fellow artists in boxes based on their past work. Celebrate their evolution as much as your own.

· See each project as transformation. Approach every creative endeavor not just as something to complete, but as an opportunity to become someone new.

Master the art of deep listening.

· Tune into the sacred signal. Cultivate profound listening to your inner creative voice, your materials, and your audience. The most powerful art emerges when you hear what wants to be born.

· Embrace true apprenticeship. Find mentors whose wisdom you trust and submit to genuine learning.

· Respond rather than react. Listen carefully and respond to feedback thoughtfully rather than defensively.

· Practice mutual surrender. In creative collaborations, be both teacher and student. The most beautiful work often emerges when everyone surrenders their need to control the outcome.

· Let the work lead. Surrender your grip on predetermined outcomes. Allow each creative work to teach you what it wants to become rather than forcing your initial vision. Some of your greatest breakthroughs will surprise you completely.

Your creative spirit and your oblate vocation are complementary gifts that can nourish something beautiful when brought together with intention. The Rule of St. Benedict offers you the ancient wisdom to cultivate both into a way of life that not only enriches your own journey but becomes a blessing for those around you.

The question isn’t whether you have time for both spiritual depth and creative expression. The question is: what meaningful expression is waiting to emerge when you honor both?

“

We are a diverse group of people spread throughout the country but brought together by our common spiritual home.

HOLLY VAUGHN Oblate of Bellmont, Illinois

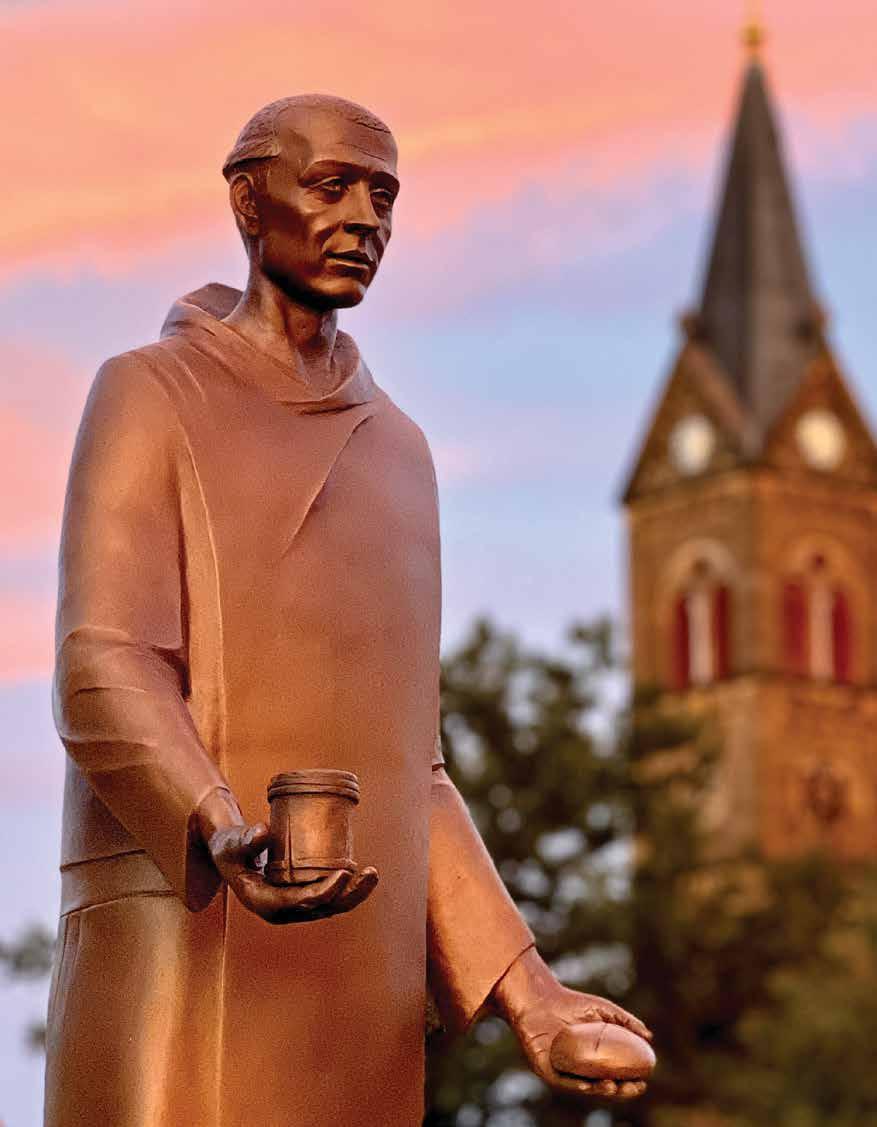

Our Holy Father Benedict, in Chapter 4 of his Rule, sets down his Tools for Good Works: a powerful, concise guide to practically living out the Christian life that is much beloved by oblates. I would like to draw special attention to the last line of this section: “The workshop where we diligently work at all these things is surely the cloister of the monastery and stability in the community” (RB 4:78). This line has special meaning for those who have an oblate chapter close to them, where they experience the community vision of Benedictine life even when they are not present on the Hill. Likewise, for those who are unable to be connected with a community because of distance or other issues, this line can bring attention to something they may feel they lack. In 2019, the Saint Meinrad Oblate Council set a plan in place to make this community aspect available to as many as possible and introduced the Saint Scholastica Online Community of Oblates of Saint Meinrad Archabbey.

We are a diverse group of people spread throughout the country but brought together by our common spiritual home. While we are not close geographically, we are united through our common prayer, and through the wonders of technology. The goal for this community from the beginning was not to simply be a written forum, or even a forum where videos were shared for one to watch on their own, but a live, interactive, and vibrant environment where real relationships are formed and maintained. Video calls were always meant to be the foundation of our communication. They were not the norm in 2019, but little did we know that they would become the foundation for communication during a global pandemic in the near future.

Through a mix of mediums — Zoom video calls and a beautiful and functional platform for written communication — our community has grown by leaps and bounds throughout

the years. We offer monthly chapter meetings and record the presentation portion so we can share it as a service to other chapters who may need presentations for their meetings. An unexpected blessing of this practice has been a lovely archive of wisdom from monks who are no longer with us, such as Fr. Vincent Tobin, OSB, and Fr. Justin DuVall, OSB. On top of the meetings, we meet for prayer and discussion regularly throughout the week, striving to offer experiences that appeal to everyone. We have weekly Lectio Divina, the Rosary, the Divine Mercy Chaplet, and a Book Club in which we have worked through many wonderful books together, sharing insights and growing in faith and community.

It has been interesting and insightful to watch smaller communities develop inside the bigger community. Some are very dedicated to the Rosary, for instance, while others never miss Group Lectio. I have seen close and lifelong

friendships form between oblates who would likely have never met if not for this chapter. I have watched the entire community come together in prayer for both small and large intentions, and I have watched our oblates comfort families they have never met when a member of our community has been called home to the Lord. I have been blessed to see witnesses inspire conversions. This is, in every way, a real community. One might wonder if relationships can really form when the people only interact through a screen. I would give a resounding yes! When people are intentional and share their lives, sufferings, and joys with one another, they are certainly going to

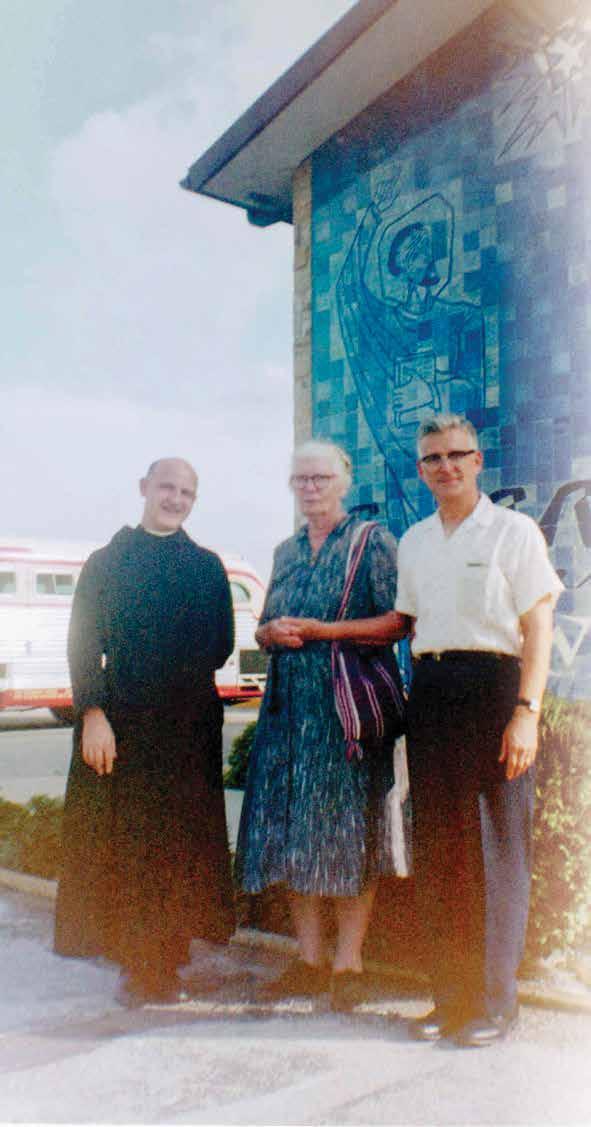

form a bond. This is most obvious to me in the times I am blessed to encounter my fellow chapter members on trips to the Hill and see them greet each other as family as the photos with this article point to.

Our chapter is open to all oblates, whether or not they are united with a physical chapter. If you need a community or want to join us in any of our activities, we will welcome you! Personally, I never could have guessed the absolute blessing these wonderful people would be in my life. They have prayed me through trials, celebrated with me in times of joy, walked with me through ordinary days, covered for

me when I was late or unable to make a scheduled Zoom meeting, and allowed me to do the same for them. When I think of my spiritual family, they are at the forefront, and I am so grateful to God for the gift of their presence and the gift of technology to be used in such a positive way. I cannot wait to see how we grow into the future. St. Benedict, St. Scholastica, and St. Meinrad, pray for us!

For all oblate information, including chapter locations and how to contact the oblate office, visit https://www.saintmeinrad.org/oblates.

JOANNA HARRIS Oblate of Lexington, Kentucky

The first verse of Chapter 5 of The Rule states, “The first step of humility is obedience without delay.” When I read this for the first time, it definitely gave me pause—it still does. I am constantly challenged to be an oblate who lives my life in humble obedience to God. In Chapter 7, St. Benedict ensures the community clearly understands what humility is by quoting Luke 14:11 and 18:14 in the first verse, “Everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted.”

Fortunately, he also provides hope that living humbly and being obedient is doable by using a ladder to illustrate the path of humility.

In my admittedly meandering path as an oblate, I’ve struggled as I’m sure all of us do, with being obedient and practicing humility. In fact, during my long (thanks to the pandemic) novitiate, I was deeply questioning if I could do this. When I had first picked up a copy of The Rule at the Archabbey Gift Shop years ago and saw that there

were full chapters talking about the expectations of being obedient and humble, my first thoughts were “I’ll never be an oblate.” Because of my doubts, I sought spiritual direction and prayed. That part of my journey lasted three years from my first look at The Rule until the day of my investiture. While my novitiate was long, I was grateful for that time to study and pray and work on my perception of the challenges I would have as an oblate.

During this time, I remember an aha moment, a Holy Spirit inspiration that came to me during prayer: “Joanna, surrender!” Yes, it would take my surrender to get on a true path of obedience and humility. I “knew like I knew” that surrendering was completely necessary. So, a new struggle/path began—to understand the act of surrender, not only struggling to understand what to surrender, but also truly wanting to do it.

You know the familiar saying, “Let go and let God?” Admittedly, I lived most of my life in the DIM (my acronym for “Do It Myself”) mindset—it’s always been a personal battle.

What is surrender? A Google search revealed the first definition to be the verb as to “cease resistance to an enemy or opponent and submit to their authority” followed by the noun as “the action of surrendering.” The suggested synonym is “submission.” I was intrigued by the definition of the verb because in the context of surrendering to the Lord, I hadn’t ever thought of Him as an enemy or opponent. When I saw this, I had another “aha moment” in realizing the surprising truth that when I refuse to surrender (and choose DIM), I am an opponent of the Lord and He could be considered an enemy. Wow! God as my enemy? While this realization disturbed me, it served to give me a new perspective on making the choice to truly surrender versus choosing to DIM.

In my faith journey, I believe God is my Father, and I am so grateful for Him. In my distant past, I was a mess and far away from God and my faith. I am beyond thankful that He loved me in spite of my choices. He picked me up from my mess and loved me. I feel that He is far from being my enemy, but now, seeing that definition of surrender, I ask myself: Am I treating

God as an opponent when I refuse to surrender my actions and choices to Him?

While there isn’t a chapter of The Rule with the title “Surrender,” St. Benedict talks about surrender right at the start of his Rule in verse 3 of the Prologue: “To you therefore, I now direct my words—whoever you may be—to you who renounce your own desires…” And, as we would expect, he talks about surrender throughout. In Chapter 4 alone, several of the “Tools of Good Works” are calling for surrender, for example: verse 10, “To deny yourself in order to follow Christ (Matt 16:24; Luke 9:23)”; verse 21, “To prefer nothing to the love of Christ”; and verse 60, “To hate selfwill.”

So, has all this knowledge helped me to give up being in DIM mode? To tackle the issue, I did my usual search for a book about it thinking that there’s a “self-help list of steps” that if followed would make surrender automatically happen. And there are many books, blogs, and YouTube videos offering formulas on how to surrender. But nothing I read in the “self-help” genre gave me a satisfying answer.

Now, I am doing my best to give it to the Lord in prayer. I am willing, but there are days when all I can muster is “being willing to be willing.” When I started earnestly praying about it, I eventually realized that praying is actually the important first step in surrender. This revelation may not surprise you, but I’ll have to admit it was truly a surprise for me and a very welcome one. In verse 4 of the Prologue, St. Benedict says “…beg [God] with most urgent prayer…” And in verses 40 and 41 he says, “Therefore, we must get our hearts and bodies ready to fight the battle of holy obedience to his commands. And let us beg God to command that the help of his grace assist us with what is barely

possible for us by nature.” Surrendering is how we can start the work of preparing our “hearts and bodies” to obey, and surrendering is how we will get on our knees and pray, trusting in God’s help and wanting His grace, and then allowing His grace to work in us so we continue handing our lives and will over to Him. When we do so, we are no longer DIM.

When I started writing this article, I had been inspired to write about truly surrendering and striving to practice humility in our daily walk. As I reread many parts of The Rule to prepare to write, I was reminded of what St. Benedict says in Chapter 5 about humility and obedience, as I stated earlier.

For me, though, before I could even embark on a path of obedience and humility, I had to surrender and to say it was hard doesn’t even begin to describe the battle it was and continues to be for me to surrender. What I do know is when I truly “let go and let God” I experience an indescribable freedom and joy. Laying my burdens, heck…even my life at the foot of His cross is the most freeing thing I’ve ever done! At first it was extremely hard to give up being in DIM mode, but in my advanced wisdom (OK, years) I’m so happy to tell you it’s become easier. The fruit of surrender and striving to be humble and obedient is FREEDOM from jealousy, temper tantrums, selfishness, anxiety, worry, planning (well, scheming), being driven—the list goes on and on. Surrendering is a lifetime journey and the journey of a lifetime.

Our compasses for our journey are the Word of God and The Rule, along with good spiritual direction and holy reading. Remember, we don’t belong to this world (John 15:19), we are children of our Father, and He is everything. Surrender, rejoice, and be glad!

BY MICHAEL CASEY Liturgical Press, 2023

Michael Casey is a gem; everything he writes sparkles. The Longest Psalm: Day-by-Day Responses to Divine Self-Reflection does just that.

The book is a series of reflections on Psalm 119. Each reflection tackles a single verse of the 176verse psalm. The reflections are short. For example, Casey’s reflection on verse 86, which is one of the longer reflections in the book, is a tad over 400 words. Each reflection is headed in bold type; the reflection on verse 86 is Assistance.

The idea here is to read one reflection per day, and that is an excellent idea to abide by.

Casey’s style is casual but not flip; full of thought-provoking theology but not couched in church-speak or academic jargon.

The world is so lucky to have the wisdom of this Cistercian monk. Add this book to your collection of Casey jewelry.

DIANE FRANCES WALTER Oblate of Georgetown, Kentucky

For the past 11 years we have had a menagerie of ducks. We had intended to get chickens all those years ago, but after some reading, decided ducks were better for us. They required less parasite control and a simpler coop. They provided pest control to our little farm that prioritized the elimination of ticks. They offered high protein eggs prized for baking, ice creams, and frittatas.

Nowadays we rarely turn on either, and we hear instead the muffled excitement of a flock’s conversation around the hedge near the front door about whatever slug or bug they have happily found.

We did not expect they would be friendly, but they are. We did not imagine we would mourn them when one is killed by a hawk, fox, or coyote, but we do. We did not anticipate the joy of incubating eggs and taking hatchlings to a hothouse and watching them grow, but they bring us joy every year.

They are a lot of work. We need to keep their pen clean and deal with injuries. They free-range during the day, and sometimes our work is finding one who accidentally landed in the neighbor’s cow pasture or pulling a duck free after getting stuck in bramble. We’ve had to bury some that have died of old age. Our mornings include standing at the sink and gently, slowly, carefully washing eggs before packing them up for the fridge.

What is interesting is, we have never regretted our decision to get ducks. Instead, we can’t remember what it was like without their soft quacks and murmurs. They, their gift of eggs and the work they have required, are just part of our lives now.

What is also interesting is, they have permanently quieted our home. Since they free range, we cannot hear if they are in trouble while we are inside if a radio is blaring or a television is on.

It would be disingenuous for me to claim that as an oblate I read Saint Benedict’s chapter titled “Quiet” and was immediately transformed by it. Our society lives in constant noise from our childhoods to adulthoods. We have machines in our homes, and in our cars we listen to music or stories. We even have earbuds and handheld screens where we often seek to be entertained more than we seek to learn. All that noise in our modern life drowns out the spaces around us, from the flutter of leafy trees to the odd chatter of web-footed birds.

However, I can attest that I grew to better understand what St. Benedict means by “quiet.” He had no inkling of how distracted our world would be, much less that Benedictines would still be reading his Rule centuries from when he penned it, and yet his message still holds.

Notably, he wrote in The Rule of St. Benedict 6:2-5: “Here the Prophet shows that if at times we ought to be quiet for the sake of quiet itself, even from speaking good, how much more should we hold back from evil words on account of the punishment of sin. Therefore, even though the words are good and holy and instructive, let permission to speak be given rarely even to the perfect disciples because of the importance of quiet, for it is written: In the midst of much talk, you will not escape from sin (Prov 10:19); and elsewhere: Death and life are in the hands of the tongue (Prov 18:21).”

I’ll admit that I was confused by this passage for many years. I understood why holding back from evil words was a good thing but was confounded that even good and holy words ought to be quelled. I also imagined this was just about the things we say but now realize it can also apply to our radios and televisions, our electronic tablets and computers. That is because we often watch or listen to the things we think we want to say.

Likewise, we can speak bad or good things, and both of those pronouncements may leave someone equally as hurt, feeling unheard, or unseen. We can blare music, podcasts, or videos, good or mean-spirited, and leave people near us feeling invisible, unwelcome, and unattended.

One day, after my dog and I chased a fox away from our feathery menagerie, this passage in Chapter 6 finally became clearer. I cannot pay attention to our feathery friends without being able to hear them. I cannot pay attention to people without being able to hear them. I cannot attend to the needs of others if I am making noise, evil or good.

Above all else, we are caring for so many, whether it be family or friends, those we work with or pray with, or even little creatures. Our most important task is to make space to hear. To create quietude and make room to pay attention to those around us, and ultimately to pay attention to the Lord.

“Death and life are in the hands of the tongue” seems a stark statement, but a group of ducks taught me that St. Benedict may be right. Death and life are sometimes the difference between building walls of noise or holding safe a quiet space.

The Oblate Voice will introduce a regular column called “Living the Rule,” beginning with the Winter 2026 issue. In this column, Br. Francis de Sales Wagner, OSB, will address questions posed by oblates regarding how they can live out the principles and values of St. Benedict’s Rule in their own daily circumstances and regarding monastic spirituality and practices in general.

Questions can be emailed to Br. Francis at brfranciswagner@gmail.com. Submitted questions should be clear and concise. They will not be answered directly via email but will be considered for inclusion in each issue’s column.

Br. Francis, a native of northwest Ohio, joined the monastery at Saint Meinrad in 2006 after nearly 20 years as a newspaper reporter and editor. He holds a master’s degree in pastoral theology and a graduate certificate in spiritual direction, both from Saint Meinrad.