Jazmín

(Respuestas a cinco preguntas retóricas y cinco fragmentos en bastardilla)

Collage de textos y entrevista a Jazmín López.

¿Cuándo?

De mis primeros acercamientos a la universidad, los recuerdos más importantes vienen de las artes visuales. Tenía diecisiete años cuando fui a la Escuela Pueyrredón a informarme: me ofrecieron tanto pintura como dibujo, escultura e incluso grabado. Ni siquiera sabía lo que era un grabado. Me anoté entonces en la carrera de Filosofía con muchas ganas pero con cierta desazón de haber dejado huérfanas las imágenes. Como si las perdiera para siempre. Le comenté a alguien que me dijo que el hijo de las imágenes y la filosofía era el cine. Me conmovió inmensamente y fue suficiente para que decidiera estudiar cine, pese a que hoy no entiendo la razón de ser de aquella afirmación. ¿Acaso las artes visuales no son la materialización máxima de los pensamientos más abstractos? O en todo caso, esa hija ¿no es la poesía? Poco importa ya.

En los 90 había un clan. Hoy no hay ni siquiera personalidades. Son o somos entes móviles. En los 90 parecía aún existir una estética contra algo, una denuncia, había una relación con la tradición. La pesadilla del pasado parece haberse esfumado y haber dejado a los artistas solos. Ahora ese algo es el propio devenir. El arte actual no se propone un fin, sino que el fin es el proceso.

Y hay dos maneras posibles de devolverle el sentido al contenido: -el de lo personal (cualquier experiencia íntima fuerte), -y el de lo social (la religión, la política de las revoluciones, la ciencia).

La falta de contenidos sociales y/o personales en el arte hace que el sentido directo se vuelva inasible.

El arte de los 00 es un fluyente estado mental que decanta en obras. Se muestra, entonces, la materia cuando todavía no tiene forma. Y esta sustancia amorfa inacabada carece de cualidad. ¿Qué queda? ¿Cómo se relaciona con el espectador? ¿Por qué en los 90 era más amable esta interacción? Al haber desaparecido la tradición y sucedido definitivamente la expropiación del sentido en tanto contenido, el artista de los 00 queda desviado. Pareciera que el arte perdió la verdad. Tal vez el contenido del arte de los 00 sea la propia intimidad del sentido. Y solo nos queda ser testigos de la producción de la significación en vivo y en directo. Ao vivo.

¡Cuánta impotencia me da imaginar que la intelectualidad nos ha abandonado! Los desertores del arte contemporáneo o los enemigos del arte contemporáneo (que están más metidos en el arte que los propios artistas) viven conservando su cultura tradicionalista que les enseña a odiar el arte de sus días amando, entonces, el pasado como tesoro. Conservan ese pasado como verdad. Guardan su alquimia en formol para resucitarla cual mosquito de Jurassic Park. Todo un esfuerzo de restaurador en lugar de pensar a sus contemporáneos. ¿No es esto infantil? Nada más ingenuo que defender el pasado poniéndolo en el ring con el presente.

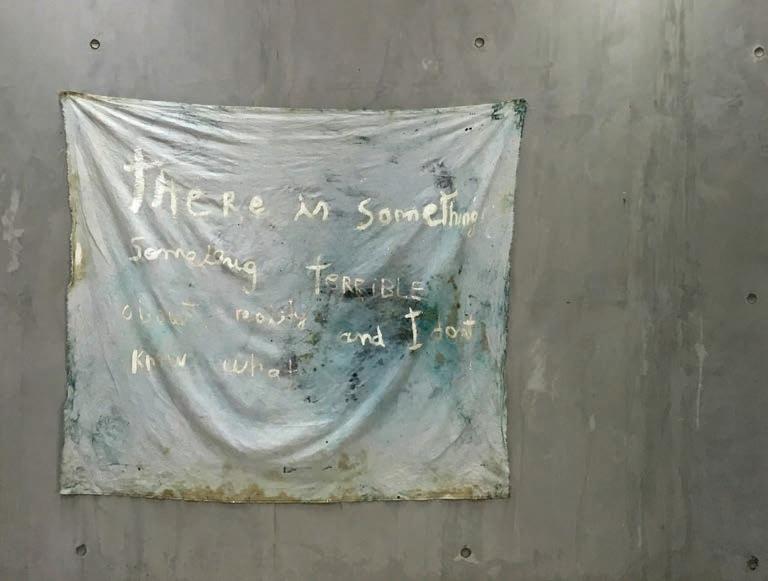

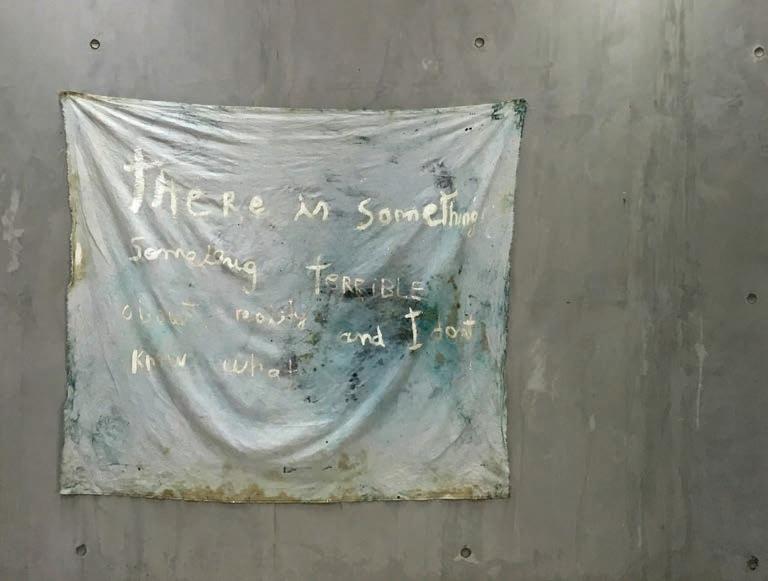

Sobre arte y política (audio uno). Me paro por primera vez en mi vida con muy pocas certezas frente a mi trabajo artístico en general y lo que encuentro es la necesidad de volver a la ideología. Tal vez no del mismo modo en el que se hizo en las contraculturas de los 60 y 70; no se puede pretender ser ingenua después de todo lo que pasó en el medio, pero sí tal vez generar un hiato y en ese hiato trazar un puente que me permita volver a entender la estética como política. No desde el diseño, como lo hacen los partidos políticos, sobre todo en Argentina, sino desde cierta idea de pregnacia e importancia. Tal vez hay que pensar cómo posicionarse en el lugar de la capacidad que tiene la poesía como conocimiento; la poesía no en el sentido escrito, sino la poética y las figuras retóricas en general como las que usan el cine, la pintura, la música. Posicionándose ahí, el partido político, la unión o la organización, deja de tener sentido porque cuando hablamos de una metáfora hablamos de una retórica que se genera en una tercera persona. En cambio, en una bandera escrita que dice PO o movimiento de izquierda o de derecha, el mensaje es directo, es unívoco: todas las personas van a entender aquello que esa bandera quiso decir. Yo quiero hacer banderas que ojalá sean poéticas y produzcan una

¿Quién?

tercera imagen que no sea lo que se está viendo… Digamos que incluya todas las imágenes que a cada persona que vio esa bandera se le produjo en la cabeza: eso quiere decir, banderas que son todas las banderas y no son ninguna…

Necesito yo, o mis trabajos piden, un espectador ávido que participe, que agregue lo faltante. En las pinturas es muy clara la falta, pero en las películas lo es también. Invitación, una intención de vaciamiento para que el que mira sea protagonista. Todo lo que el veedor pueda imaginar, agregar o adosar es mucho más vasto que alguna respuesta que caiga de mis labios.

El artista de los 00 dejó de ser extraordinario. Dejó de ser excéntrico, dejó de ser personal. Artista con jean y remera. Esto lleva a pensar en el tema tan visitado sobre la profesionalización del artista. Personalmente no creo que este sea un tema fértil, por lo menos no en la Argentina.

Antes el artista producía ficciones. El límite físico era claro, dónde empezaba y dónde terminaba la pieza. Tenía marco. La realidad actual produce más fábulas que los artistas: la política, el cine documental, hasta incluso la economía política es dueña de las ficciones. El artista de los 00 produce o intenta producir realidades o verdades: vómitos de subjetividad pura. Dado que no existe la objetividad, la subjetividad tomó esa batalla.

La responsabilidad de un artista es dar cuenta de una realidad dada, sea personal o social. En el mejor de lo casos, es la combinación de las dos. No crear mensajes sino crear mundo. Por eso la falta de marcos. El artista puede cambiar las conciencias pero solo a partir de la impresión. Impresionismo. Modificando la sensibilidad de quien observa. Se parece a la religión y se parece a los animales. Cuando uno sale de una misa o de una meditación se lleva un souvenir: un estado de conciencia alterado. Y cuando pasamos un buen rato con un animal (cuanto más grande sea el bicho mejor) pasa algo parecido. Ese movimiento nos hace percibir las calles por las que llegamos a la iglesia o al templo como diferentes, como si las camináramos por primera vez. Eso es lo que creo que debería pasar al salir de un museo, al salir de cualquier espacio que contenga estas impresiones. ¿Cómo hacer para transmitir al menos esa voluntad a quien mira?

Los artistas contemporáneos desconfían de sus espectadores y los espectadores desconfían de sus artistas. Sordera. Autismo. Tabú. Encuentro cierta similitud con las vanguardias históricas: el hecho de esconder los códigos (los lenguajes). Las vanguardias lo hacían en pos de crear un nuevo mundo, un nuevo hombre. Parecían las bases de la creación de un mundo ideal pero posible. Para crear el nuevo hombre que aprecie el arte, como también imaginaba la Bauhaus, es necesario

¿Cómo?

que el que ve se entregue, se deje llevar, que sea permeable a las transformaciones propias del mundo, que esté fascinado por su tiempo y no cautivado en la nostalgia. Ahora la coexistencia de mundos se ha aceptado de tal forma que solo quedan burbujas aisladas que se chocan en sus perímetros y aprovechan el envión del roce para disparar hacia el lado opuesto. Jamás se rompe una burbuja.

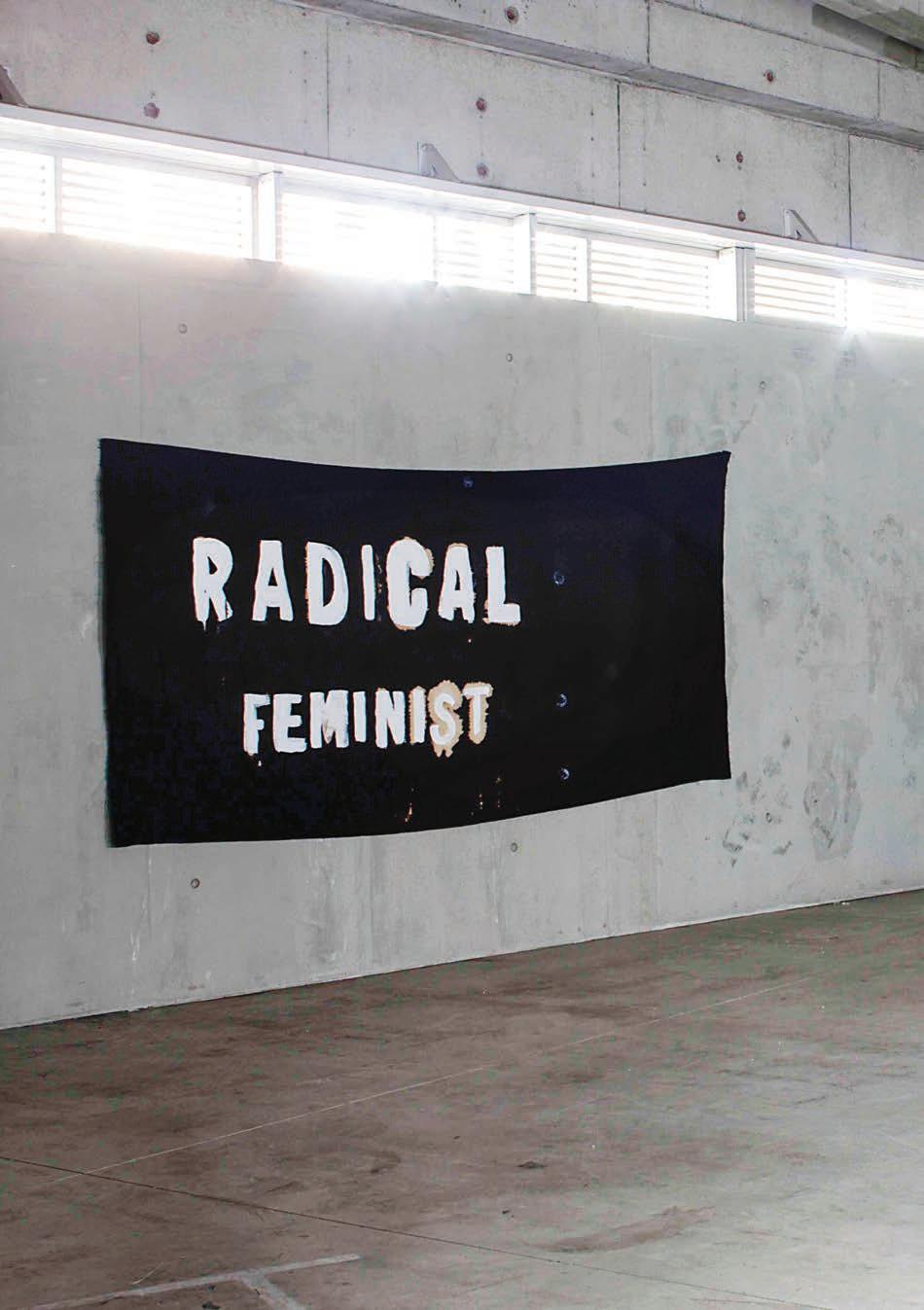

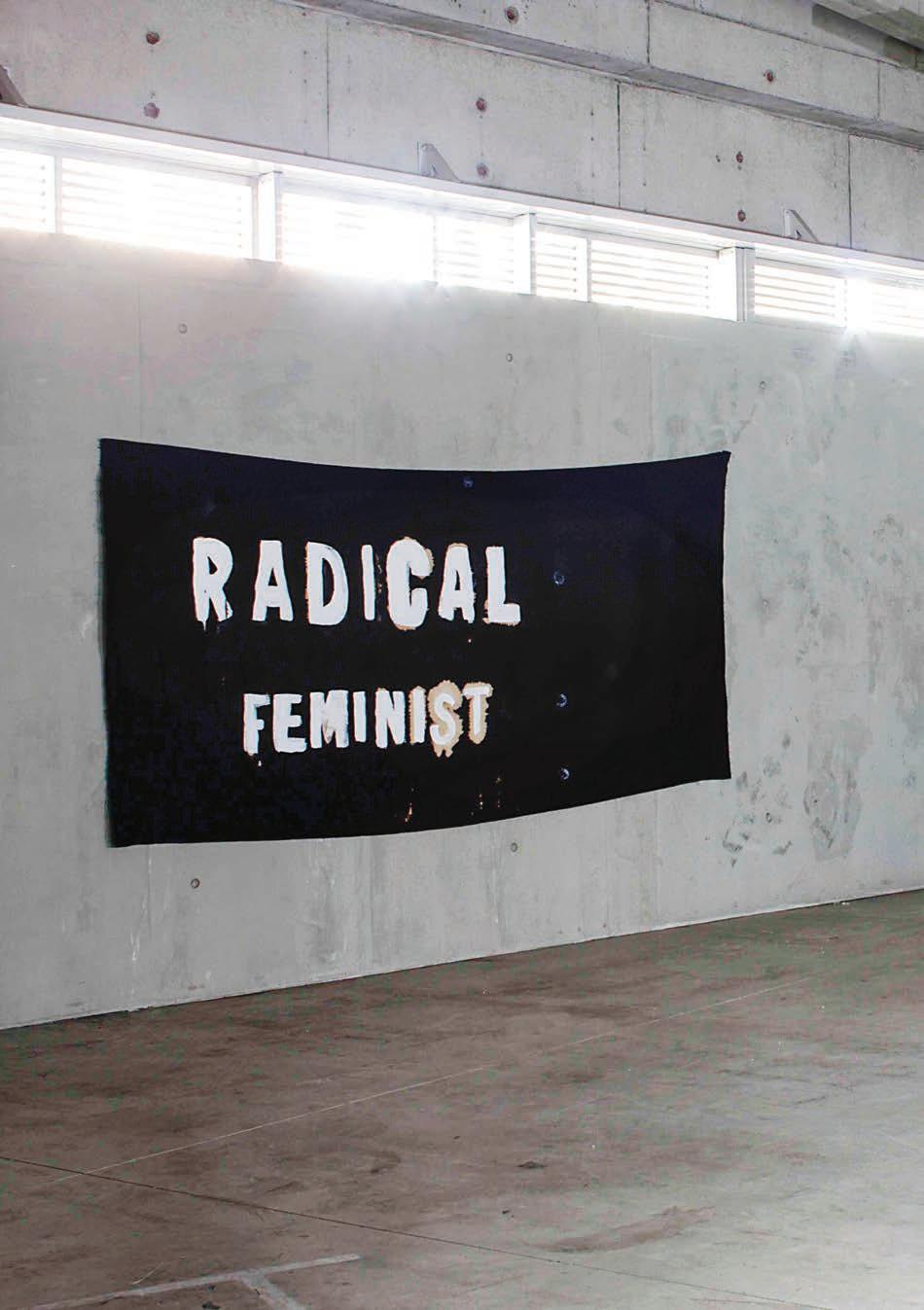

Sobre arte y política (audio dos). Escribí una carta abierta en la cual expliqué por qué propuse esa bandera con la inscripción Radical Feminist que hicimos con un grupo de estudiantes de la Universidad de Lima para llevarla a una manifestación de Ni Una Menos allá. Perú es uno de los países con más violaciones de padres a hijas. Hay una especie de slogan de las madres: “Papá tiene necesidades”. Es decir, la posibilidad de una violación está absorbida por la propia familia. Y cuando hacíamos esa bandera pensábamos mucho en cómo deconstruir esa frase, cómo pensarla por fuera incluyendo su historia, pero sacándole casi hasta la fonética, la posibilidad de ser leída. Por eso, todas las letras están desvaneciéndose como si el tiempo las desgastara. Y pensando en el mismo sentido desde la imagen, ¿qué tipo de imagen puede producir esto en cada mirada? ¿Qué tipo de artística puede producir estas operaciones en las que la comunicación deja de tener sentido, cesa? No importa si le falta una letra, si leíste exactamente… Creo que la pintura tiene esa capacidad y no deja de ser la pintura el material con que se hacen las banderas; más allá de que hoy las imprimas, vienen de ese gesto, de pararse frente a una tela en blanco. ¿Qué diferencia hay entre pararse frente a la tela en blanco de una bandera y pararse frente a una tela en blanco de una pintura? Yo creo que ninguna…

Primero recordé la imagen y después vinieron las palabras. ¿No es acaso lo mismo? Sí, es lo mismo. Visualicé las letras, podría decirse. Bueno, recordé la tapa de un libro de Rimbaud. Recordé el título porque recordé la gráfica de la tapa que él no hubiese podido concebir. Y en ese instante entendí que lo genial no era esa imagen sino que lo que brillaba era la sonoridad pero también el contenido de ese título que no se me va del pensamiento. “HAY QUE SER ABSOLUTAMENTE MODERNO”, hay que ser absolutamente moderno. Voy a volver sobre esto.

La génesis de cada uno de mis trabajos es visual y nunca narrativa. Veo en mi quehacer un conjunto de preguntas organizadas en un texto, un texto imagen que es un camaleón.

Creo que los movimientos no son y son evidentes. Depende del punto en el que uno se pare a mirar. Mis motivos son formales. La primera idea que recorro es una imagen, y con

¿Dónde?

imagen me refiero a una manifestación formal de un movimiento o idea, nunca al revés. Someto, entonces, esa forma a una serie de ¨estudios¨ como de laboratorio en donde trato de destilar la matriz, la idea debajo de esa forma.

El arte contemporáneo como género: se suplen los contenidos por las cualidades formales. Como un holograma centrípeto que se repliega y se repite hacia adentro en lugar de contener algo. La forma es el contenido. Es importante pensar en la palabra contenido en sí misma. El término asume la existencia de la forma contenedora, valga la supuesta contradicción. Pero en este caso no habría nada o habría solo réplicas de la forma dentro de la forma. Es como si finalmente la palabra contenida hubiese podido ejercer su voluntad etimológica.

Las convenciones del lenguaje visual se garantizan por su forma y no por lo que esa forma contiene, ya que esta forma contiene forma.

Me gusta la idea de que las miradas se vuelvan más justas y sí, justas de justicia.

Sobre arte y política (audio tres). Yo creo que existe hoy una capacidad o responsabilidad de entender que la poética es de cada uno y la responsabilidad está no solo en hacer sino en ver. Tanto en mis películas como en mis pinturas hay siempre un faltante. Hay algo que no está, que si no hay un espectador ávido o un par de ojos que tomen la responsabilidad de completar, no hay nada. Y eso es algo en lo que quiero insistir y seguir trabajando. El faltante es una especie de puerta que invita a unos ojos que sean responsables al mirar. ¿Por qué? Porque si no, no hay impresión. Cuando me preguntan qué quiso decir la obra, pienso “No quiso decir nada porque si no, lo hubiese escrito; porque si no, sería una comunicadora visual y no lo soy”. Pero el hecho de dejar una puerta abierta, algo inacabado, hace que el que ve se vuelva protagonista. Y ahí hay un acto político, del que ve, ni siquiera mío, no me lo estoy quedando yo. Porque se está movilizando, porque está pasando algo ahí. Entonces si todos tenemos esa responsabilidad, es una especie de no partido de todos, de partido sin partido…

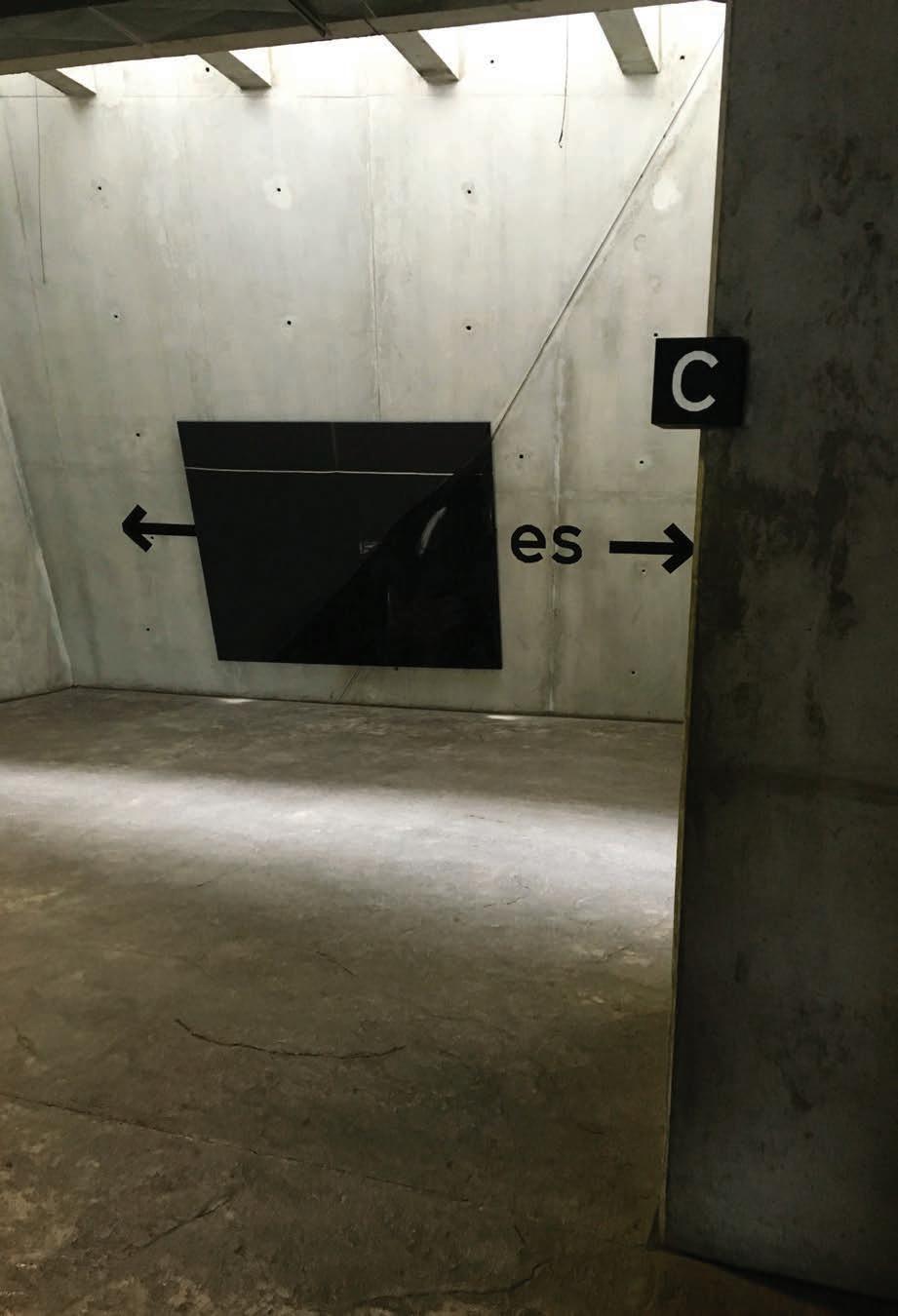

No quiero ir a los grandes museos y a las grandes galerías. No quiero ir a las instituciones, son de algún modo una forma enferma. Ese blancor y esa cuadradez son parecidos a los hospitales, a los lugares sin forma, a los lugares asépticos.

Los espacios interesantes son siempre otros. Aquellos que son chiquitos pero llenos de vida son los que dejan que la obra se vea, se escuche y se sienta.

Son rincones que no pretenden el blanco celestial pero que de algún modo mucho más esotérico dejan ver el cuadro como si fuera traslúcido, dejándonos ver eso y aquello, o todo a la vez.

No estoy descubriendo ningún mingitorio, solo hablo como espectadora.

La anatomía del arte se transforma: el arte ahora comparte espacio con todo. No hay un espacio definido que contenga las obras.

La obra de arte actual o la de los 00 es irreductible de su contexto, me refiero a su contexto temporal. No existe sola. No puede. La duración de la mirada es ingrediente más que nunca. Se volvió teatral. Y sus obras son su utilería. No hay intercambio de sentido, hay intercambio de tiempo.

Sobre arte y política (audio cuatro). Me pasa mucho, cada vez más y cada vez más claro, de reconocer que entro en una especie de personaje al pintar. No soy yo esta que está hablando (en realidad por supuesto que sí porque todos estamos hechos de un montón de identidades) pero hay una que es esa Jazmín pintora que es una extraña, que es como si la canalizara, un ser channeling, ponerse a ser un medium de algo, y no soy yo: los movimientos de mi cuerpo no son exactamente los mismos que cuando estoy haciendo otra cosa. Entonces hay un aire muy performático en mi arte. En general, mis pinturas tienen un tamaño en relación a mi cuerpo, como si el ancho fuera el ancho de mis brazos y hubiese una dimensión de una escala de 1:1. Nunca es mesa y trabajar en un mundo chiquito. Es a mi escala. Son pinturas grandes con gestos torpes. Como si estuviese en trance, disfrazándome de otro que no soy o que no sé lo que es eso que hago cuando pinto: me disfrazo de la que pinta. Y me parecía interesante pensar la posibilidad de un libro que se disfraza. ¿Cómo se disfraza un libro? ¿Cómo se mete un contenido adentro de otro? ¿Cómo se rompe la significación que tanto estoy queriendo romper cuando hablaba de las banderas? Y ahí pensé en un libro disfrazado: en un libro que aparente ser uno y es otro. Y junto con eso está la deconstrucción dentro de mi propio libro, ese rojo, esa tapa intensa se va desarmando, decolorando, y se va construyendo en distintas imágenes que no necesariamente ilustran ese libro pero que ilustran otras cosas que no son aquellas. Yo tengo una serie de logos de Volkswagen que están deconstruidos y no estoy haciendo apología o contraapología de Volkswagen, sino simplemente pensando en esa forma, qué significó y cómo la puedo destruir, y esa imagen sigue. Cómo vaciar una forma para llenarla de otra. ¿Y esa otra cosa qué es? Es pintura. No es contenido, no es “tengo una opinión especifica respecto a las radicales feministas, o a el logo de Volkswagen o a la tapa del libro de Mao”.

¿Por qué?

“Fuga psíquica”* en inglés, un estado de disociación o jet lag ideológico. Pienso que el arte contemporáneo tiene algo disociatorio, que te separa del contenido, que lo pone en vilo, que un poco te hace mal, te aleja de algo suave, infantil o cálido... Una especie de frialdad más allá de la temperatura del contenido... Como la ironía sin cariño, sin risa, o una risa estridente, frenética.

Sobre arte y política (audio cinco). También podríamos pensarlo como un reenactment, como un volver a poner en escena. ¿Qué pasa si traigo esto a la mesa? ¿Cómo se relaciona? El libro rojo fue un libro de uso, un manual. Como el mate en los uruguayos, lo llevaban debajo del brazo. Es una herramienta para enfrentarse a la vida, como una especie de filtro, de anteojos. No es un libro que uno se sienta a leer en el sillón, prende la luz y apaga todo el resto. Es un libro de batalla. Pero a la vez, para nosotros, no deja de ser una ficción, una obra. Ya poco importa lo que tenga que decirnos sobre la revolución china, en todo caso es una materialidad ficcional que es potente en conjeturas. Un libro para conjeturar y para conjurar, en el sentido de volver a convocarlo, ¿no? Conjurar ese libro de Mao y ver qué pasa. No se trata de una hipótesis en la que voy a demostrar algo, sino todo lo contrario. Es un vamos a ver. Vamos a ver qué pasa…

*Concepto desarrollado por Claudio Iglesias en la conferencia RE:00, en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, durante 2015.

(Answers to five rhetorical questions and five fragments in italics)

Collage of texts and an interview with Jazmín López.

My most significant memories of my initial encounters with higher education are all related to the visual arts. When I was seventeen, I went to the Escuela Pueyrredón to check it out: they offered courses in painting, drawing, sculpture and engraving. I didn’t even know what an engraving was. So I signed up for the philosophy degree with plenty of enthusiasm but a little regret at having abandoned images. I felt as though I’d lost them forever. I mentioned this to someone and they told me that the child of images and philosophy was cinema. I was deeply struck by this, so much so that I decided to study cinema but today I’m not sure how true that statement is. Aren’t the visual arts the maximum expression of one’s most abstract thoughts? Or wouldn’t that child be poetry? It doesn’t really matter now.

In the 90s there was a clan. Today you don’t even have personalities. They, or we, are mobile entities. In the 90s there still seemed to be an aesthetic protesting something, a statement, a relationship with tradition. The nightmare of the past seems to have faded away, leaving artists alone. Now, that something is the act itself. Contemporary art doesn’t have a point, the process is the point.There are two possible ways of restoring meaning to content:

- From the personal realm (any intense intimate experience)

- From the social realm (religion, revolutionary politics, science) The lack of social and/or personal content in art makes direct meaning impossible.

The art of the 2000s was a fluid mental state being funnelled into artworks. The subject was revealed before it even had a form. And that amorphous, unfinished subject lacked quality. What was left? How was the viewer supposed to relate to the artwork? Why was that interaction more rewarding in the 90s? Following the disappearance of tradition and the definitive expropriation of meaning from content, the artist of the 2000s was stranded. It was as though art had misplaced truth. Maybe the content of the art of the 2000s was the intimacy of meaning. And all we had left was to witness the production of meaning live. Ao vivo.

Oh, it made me feel so impotent to think that our intellect had abandoned us! Deserters from contemporary art, or the enemies of contemporary art (who were more involved in art than the artists themselves) went on preserving their traditional culture, learning to hate the art of their time and thus to love and cherish the past. They preserved the past as though it were truth. They kept its alchemy in formaldehyde so as to bring it back to life, like with the mosquitoes in Jurassic Park. Putting all that effort into restoration rather than having to think about their contemporaries. Isn’t that childish? There’s nothing more naive than trying to defend the past by shoving it into the ring with the present.

On art and politics (recording one). For the first time in my life, I find myself very uncertain about my artistic work in general, what I find myself needing is a return to ideology. Maybe not in the same way as in the countercultures of the 60s and 70s; one can’t pretend to be naive after everything that has happened in the meantime but perhaps one might create a hiatus and within that hiatus build a bridge that allows them to see aesthetics as politics once more. Not as a design, like political parties, especially in Argentina, but as potentiality and significance. Perhaps one needs to consider how to place themselves in the space where poetry is knowledge, not poetry in the strictest sense but poetics and rhetorical symbols in general; like those used in cinema, painting and music. Placing a political party, union or organization there makes no sense because when we use a metaphor we are generating something rhetorical in the third person. In contrast, a banner that reads PO or a left-wing or right-wing movement is a direct message with a single voice: everyone is going to understand what the banner is trying to say. I want to make banners that will, hopefully, be poetic and produce a third image that is more than what one sees... Let’s say that it includes all the images that come into the heads of everyone who sees the banner: banners that are every banner and no banner...

I need, or my artworks require, a committed viewer to add what’s missing. The lack is very clear in the paintings but it’s there in the films too. An invitation, an intentional emptiness in order to make the viewer the protagonist. Anything they can imagine, add, or embellish will be far more valuable than anything that might come out of my mouth.

The artist of the 2000s ceased to be extraordinary. They ceased to be eccentric, they ceased to be personal. An artist in jeans and a t-shirt. This is leading to the well-trodden debate about the artist as a professional. Personally, I don’t think it’s a very fertile area, at least not in Argentina.

Before, artists produced fictions. The physical boundaries, where the piece began and ended, were clear. They had frames. Today, actual reality produces more fables than those made by artists: politics, documentary cinema, even the political economy are masters of fiction. The artist of the 2000s produced, or sought to produce, realities or truths: vomiting out pure subjectivity. Because objectivity did not exist, subjectivity took over.

It is an artist’s responsibility to expose a given reality, be it personal or social. Or, ideally, a mixture of the two. Not to create messages but rather worlds. Hence the lack of frames. The artist can affect people’s awareness but only by making an impression. Impressionism. Changing the viewer’s sensibility. It’s like a religion and it’s like animals. When one comes out from mass or after a meditation, they bring a souvenir with them: an altered state of consciousness. And when you spend a lengthy amount of time with an animal (the bigger the better), something similar happens. That shift makes us perceive the streets along which we came to the church or temple differently, as though we were walking them for the first time. That is what I believe should happen when you come out of a museum, when you leave whatever space contains these impressions. How can one convey that, or at least that intention, to the viewer?

Contemporary artists don’t trust their viewers and viewers don’t trust their artists. Deaf. Autistic. Taboo. I see a similarity with some of the historic avant-garde movements: the act of hiding codes (languages). The avant-garde did it in an effort to create a new world, a new man. They appeared to be the foundations for the creation of an ideal but achievable world. To create a new man who can appreciate art, which was also a dream of the Bauhaus, it is necessary for the person seeing give themselves over, to let themselves go, to be permeable to the transformations taking place in the world, to be fascinated by their time and not beholden to nostalgia. Now the coexistence of worlds has been accepted in such a way that only isolated bubbles are left, their edges bumping against each other and using the momentum from the collision to head for the other side. The bubbles never burst.

On art and politics (recording two). I wrote an open letter in which I explained why I made a banner on which I wrote Radical Feminist along with a group of students from the University of Lima to take to a Ni Una Menos1 demonstration there. Peru has one of the highest rates of rape of daughters by fathers in the world. There’s a saying the mothers have: ‘Daddy has needs’. The potential for rape is absorbed by the family. As we made the banner, we thought hard about how to deconstruct the phrase, how to look at it from the outside, including its history but stripping it of everything else, even the phonetics, the possibility of it being read. That is why all the letters are fading, as though time were swallowing them up. Thinking about the image in a similar way, one asks what kind of image might produce that in every gaze? What kind of art can spur a process in which communication becomes meaningless? It doesn’t matter if a letter is missing, if you read it precisely... I think that painting has that capacity and painting is still the stuff from which banners are made, even though these days they’re printed; it’s where they come from, you’re standing in front of a blank canvas. What’s the difference between standing in front of the blank canvas of a banner or that of a painting? I don’t think there is one...

First, I remembered the image, but aren’t they the same thing? Yes, they are. You might say that I visualized the letters. Well, I remembered the cover from a book by Rimbaud. I was reminded of the title only after remembering a graphic from the cover that he wouldn’t have been able to conceive of. And at that moment I realized that the great part wasn’t the image; the part that stood out was the sound but also the content of a title that I can’t stop thinking about ‘ONE MUST BE COMPLETELY MODERN’, you must be completely modern. I shall return to that.

The genesis of each of my artworks is visual, never narrative. In my practice, I see a set of questions organized into a text, a text-image, a chameleon.

I think that the moves are evident and that they aren’t. It depends on your perspective. My motifs are formal. The first idea that comes to me is an image and by image I mean the formal manifestation of a move or an idea. Never the other way around. Then I subject that form to a series of ‘tests’, like in a laboratory where I try to distil the matrix, the idea underlying the form.

1The collective takes its name from a 1995 phrase by Mexican poet and activist Susana Chávez, “Ni una muerta más” (Not one more dead woman).

Contemporary art as a genre: content is replaced by formal qualities. Like a centripetal hologram going back on and repeating itself inwardly instead of containing something. It is important to consider the word ‘content’. The very term assumes the existence of a containing form, even if that might sound like a contradiction. But in this case there’s nothing inside or nothing but replicas of the form inside the form. It’s as though the word ‘contained’ had finally been able to exercise its etymological will.

The conventions of visual language are ensured by their form, not by what that form contains, because the form contains form.

I like the idea of gazes becoming more just, and yes, I mean just as in justice.

On art and politics (recording three). I believe that today there is an ability or responsibility to understand that poetics belong to each of us and that it is our responsibility not just to make but also to see. There is always something missing in my films and paintings. There’s something that isn’t there that, without a committed viewer or a pair of eyes that take responsibility for being thorough, will never exist. And that’s something that I want to focus and continue working on. The missing part is a kind of door that invites eyes to take responsibility when they look. Why? Because if not, no impression is made... When people ask me what the artwork is trying to say I answer: ‘It wasn’t trying to say anything, if it had I would have written it; if it had I would be a visual communicator and I’m not.’ But the act of leaving a door open, something unfinished, makes the person looking into the protagonist. And there’s a political act there, on the part of the person seeing; not me, I’m not there. Because it’s shifting, because something is happening there. So, if we all have that responsibility, it’s a kind of non-party that belongs to everyone, a party without a party...

I don’t want to go to the big museums and major galleries. I don’t want to go to institutions, they’re kind of a sick way of doing it. The white cube is like a hospital, like a formless place, a sterile place.

Interesting spaces are different. The ones that are small but full of life are the ones that allow the artwork to be seen, heard and felt.

They’re corners that don’t aspire to heavenly whiteness, they’re much more esoteric, allowing the painting to be seen as though it were translucent, allowing us to see this and that, everything at once.

Why?

I’m not unveiling a urinal, I’m just talking as a viewer.

The anatomy of art is changing: now art shares space with everything else. There isn’t a defined space that contains artworks.

The contemporary work of art, or those from the 2000s, cannot be removed from their context, I mean their temporal context. They don’t exist on their own. They can’t. The duration of the gaze is now more of an ingredient than ever. It has become theatrical. And artworks are their tools. There’s no exchange of meaning, there’s an exchange of time.

On art and politics (recording four). Increasingly, with ever greater clarity and frequency I realize that I become a kind of character when I paint. It’s not me talking (actually of course it is because we’re all made up of a lot of different identities) rather there is someone called Jazmín the painter, a stranger. It’s as though I were channelling her, becoming a medium for someone who isn’t me: my body moves differently from when I’m doing something else. So there’s a very performative aspect to my painting. In general, their size is related to my body, as though the width were the span of my arms on a 1:1 scale. It’s never about working at a desk or in a small world. It’s at my scale. They’re large paintings with raw gestures. As though I were in a trance, pretending to be something else, something I’m not. When I’m painting, I don’t know what I am: I dress up as someone who paints. I’m interested in the idea of a book in disguise. How might a book disguise itself? How might one smuggle one kind of content inside another? How can one break down the meaning I so longed to break down when I was talking about banners? That was when I thought of a book in disguise: a book that looks like one thing but is actually something else. And along with that comes deconstruction within my own book. The red, that intense cover breaks down, losing its colour and is built back up again in different images that don’t necessarily illustrate the book but rather other things that aren’t those things either. I have a series of deconstructed Volkswagen logos but I’m not apologizing or counter-apologizing for Volkswagen, just thinking about the form, what it meant and how I can destroy it. The image goes on. How can one empty the form to fill it with something else? And what might that other thing be? It’s painting. It’s not content, it’s not ‘I have a specific opinion about radical feminists, or the Volkswagen logo, or the cover of Mao’s book’...

‘Psychic fugue’*, a state of disassociation or ideological jet lag. I think that contemporary art has something disassociative about it, something that separates you from content, that

keeps it in suspense, that hurts you a little, keeping you away from something gentle, childlike and warm... A kind of coldness regardless of the temperature of the content... Like irony without the tenderness, without laughter, or a shrill, frenetic cackle.

On art and politics (recording five). We might also see it as a reenactment, as a way of restaging something. What if I were to bring this to the table? How does it relate? The little red book was practical, a manual. People carry it under their arm, like Uruguayans do with mate. It’s a tool for dealing with life, like a kind of filter, a pair of glasses. It’s not a book you read in an armchair, with just a reading lamp for light. It’s a book of war. But also, for us, it’s still a fiction, a work of art. It no longer matters what it might tell us about the Chinese revolution, at most it’s fictional materiality, full of powerful conjecture. A book of conjecture and conjuration, in the sense of bringing something back from the past, you see? We conjure Mao’s book and wait to see what happens. It’s not a hypothesis by which I hope to demonstrate something but precisely the opposite. It’s about waiting and seeing. Let’s see what happens...

2015

Pensar que es todo parte de un gran plan

[The Belief That it’s all Part of a Grand Plan]

Marcador, óleo y lápiz sobre tela

[Marker, oil paint and pencil on canvas]

218 x 260 cmp.24-25

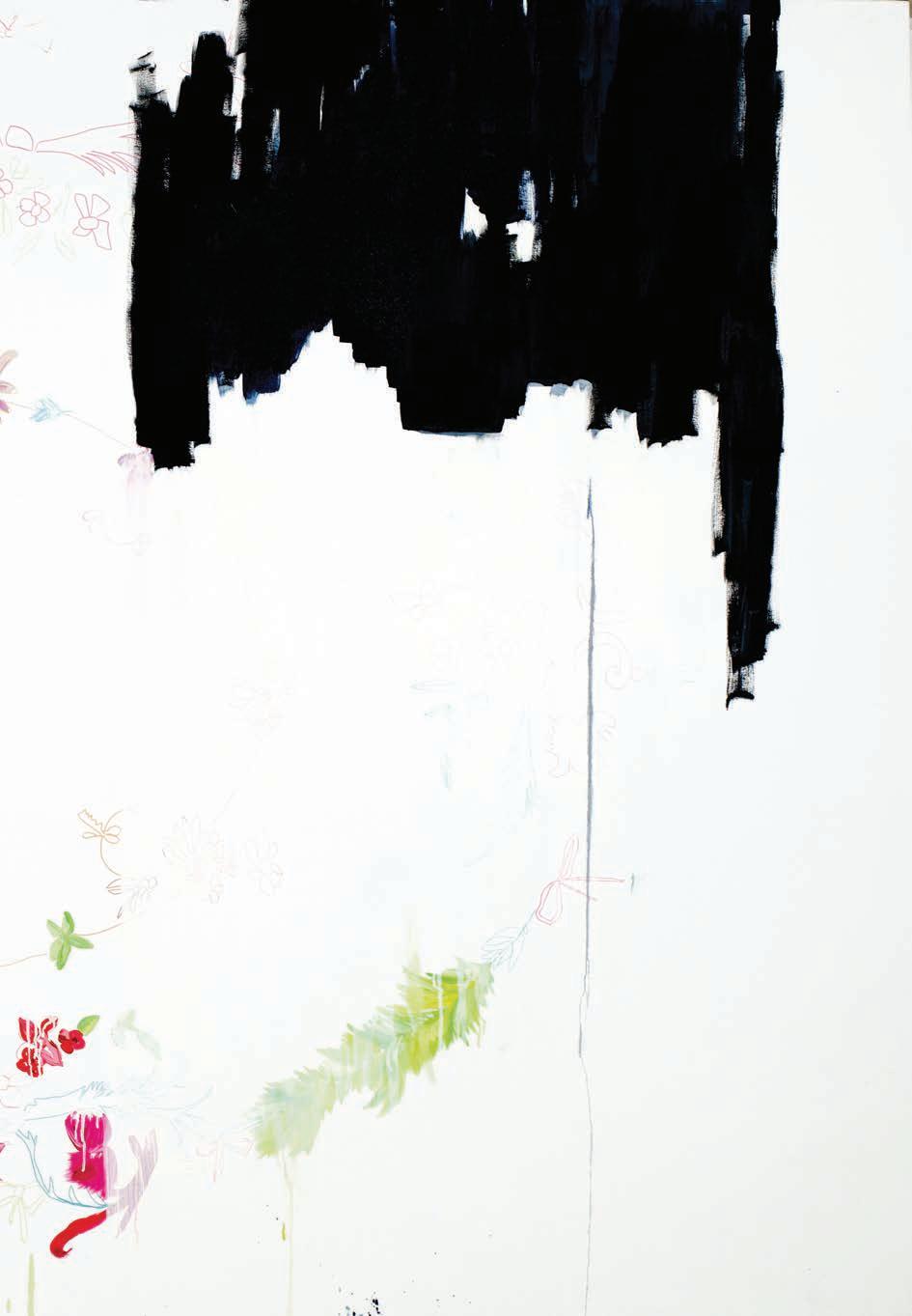

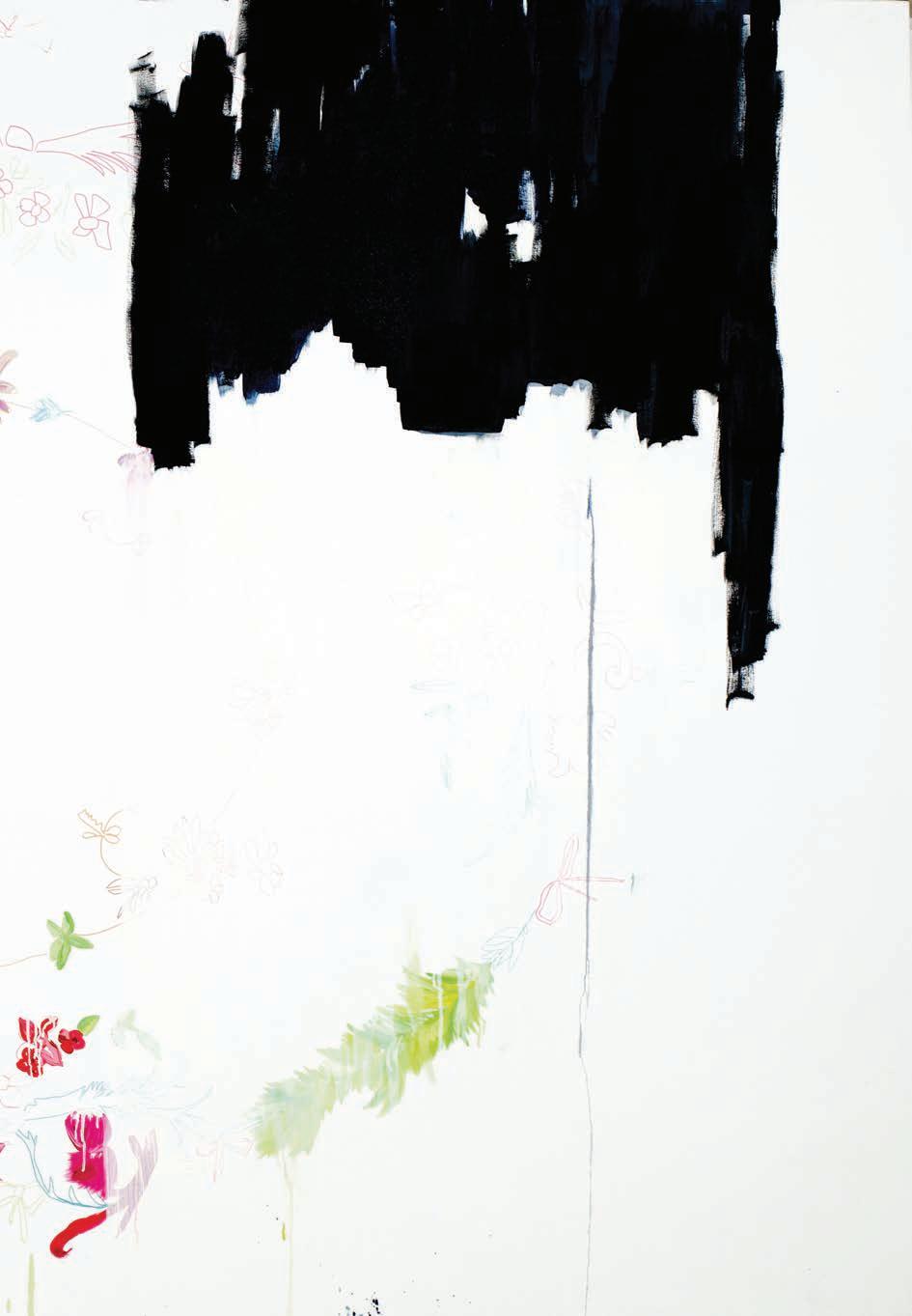

2010

Pensar que es todo parte de un gran plan

[The Belief That it’s all Part of a Grand Plan]

Acrílico sobre tela

[Acrylic on canvas]

250 x 260 cmp.27

2011

Pensar que es todo parte de un gran plan

[The Belief That it’s all Part of a Grand Plan]

Óleo y marcador sobre tela

[Oil paint and marker on canvas]

210 x 270 cmp.28

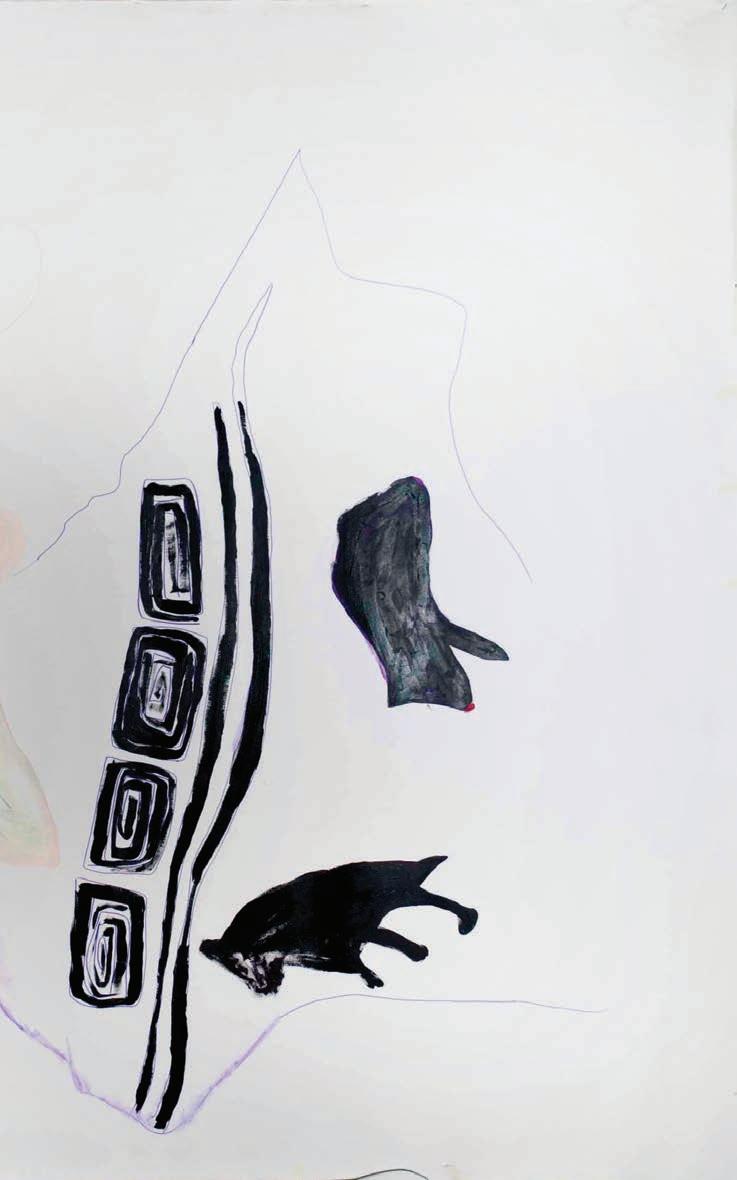

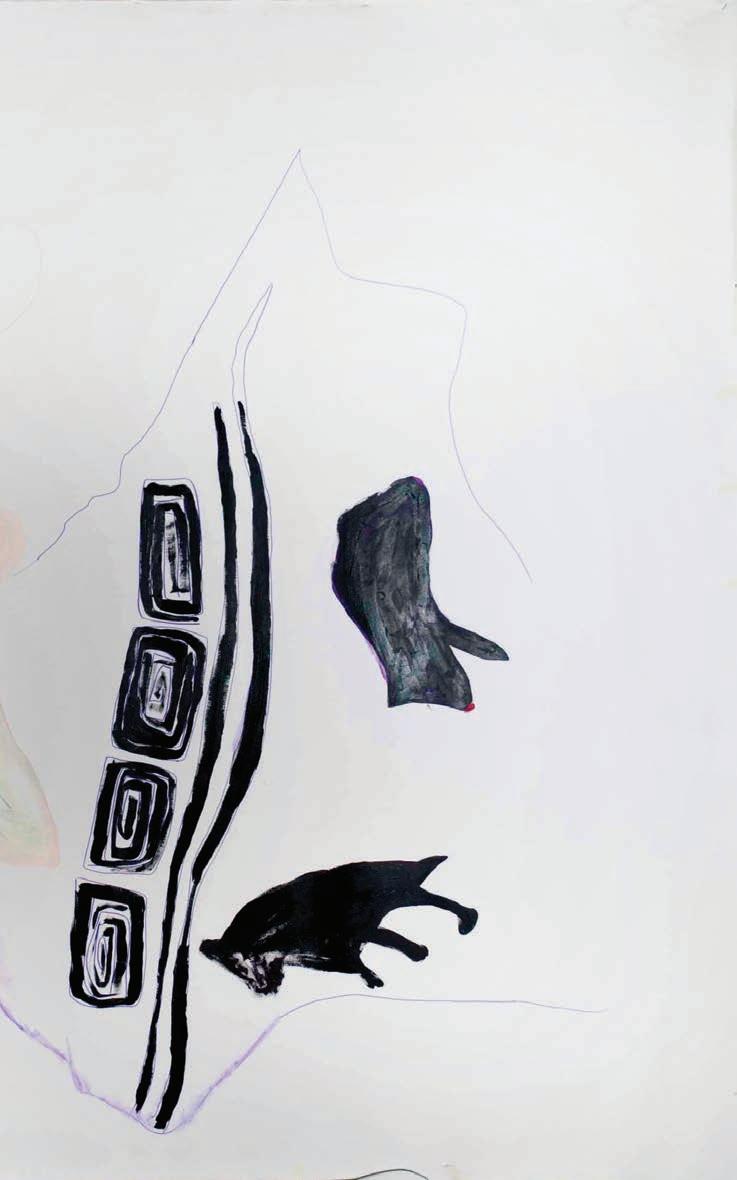

2011 Sin título [Untitled]

Óleo y marcador sobre tela [Oil paint and marker on canvas] 250 x 200 cmp.29

2016 Sin título [Untitled]

Lavandina sobre tela [Bleach on canvas] 250 x 200 cmp.31

2016 Sin título (Time) [Untitled (Time)] Crayón sobre tela [Crayon on canvas] 130 x 130 cmp.32

2016 Sin título (Arms) [Untitled (Arms)]

Adhesivo sobre tela [Glue on fabric] 130 x 130 cmp.33

2016

Cubismo [Cubism]

Jean cortado y purpurina [Cut denim and glitter] 140 x 140 cmp.35

2016

Creando tonos de piel para pintura al óleo [Creating Flesh Tones for Oil Paintings]

Óleo sobre denim

[Oil paint on denim] 40 x 65 cmp.36-37

2017

Creando tonos de piel para pintura al óleo

[Creating Flesh Tones for Oil Paintings]

Óleo sobre tela

[Oil paint on canvas] 120 x 100 cmp.39

2016

Creando tonos de piel para pintura al óleo

[Creating Flesh Tones for Oil Paintings]

Óleo sobre jean, marco de madera

[Oil paint on jeans, wooden frame]

80 x 130 cmp.40-41

2018

Canción cantada mientras se ejecuta un trabajo físico difícil [Song Sung While Doing Arduous Physical Work]

Óleo, tubos y pescado sobre algodón

[Oil paint, tubes and fish on fabric]

110 x 170 cmp.42-43

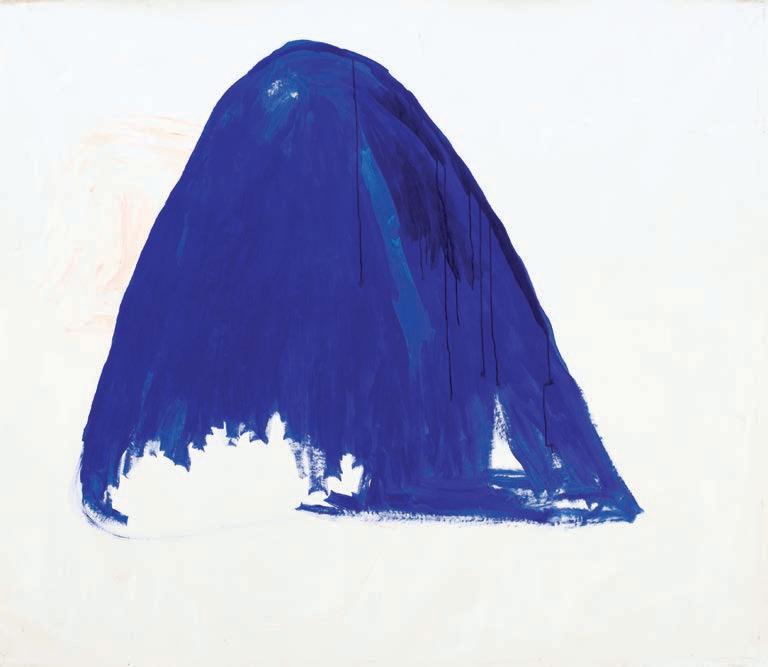

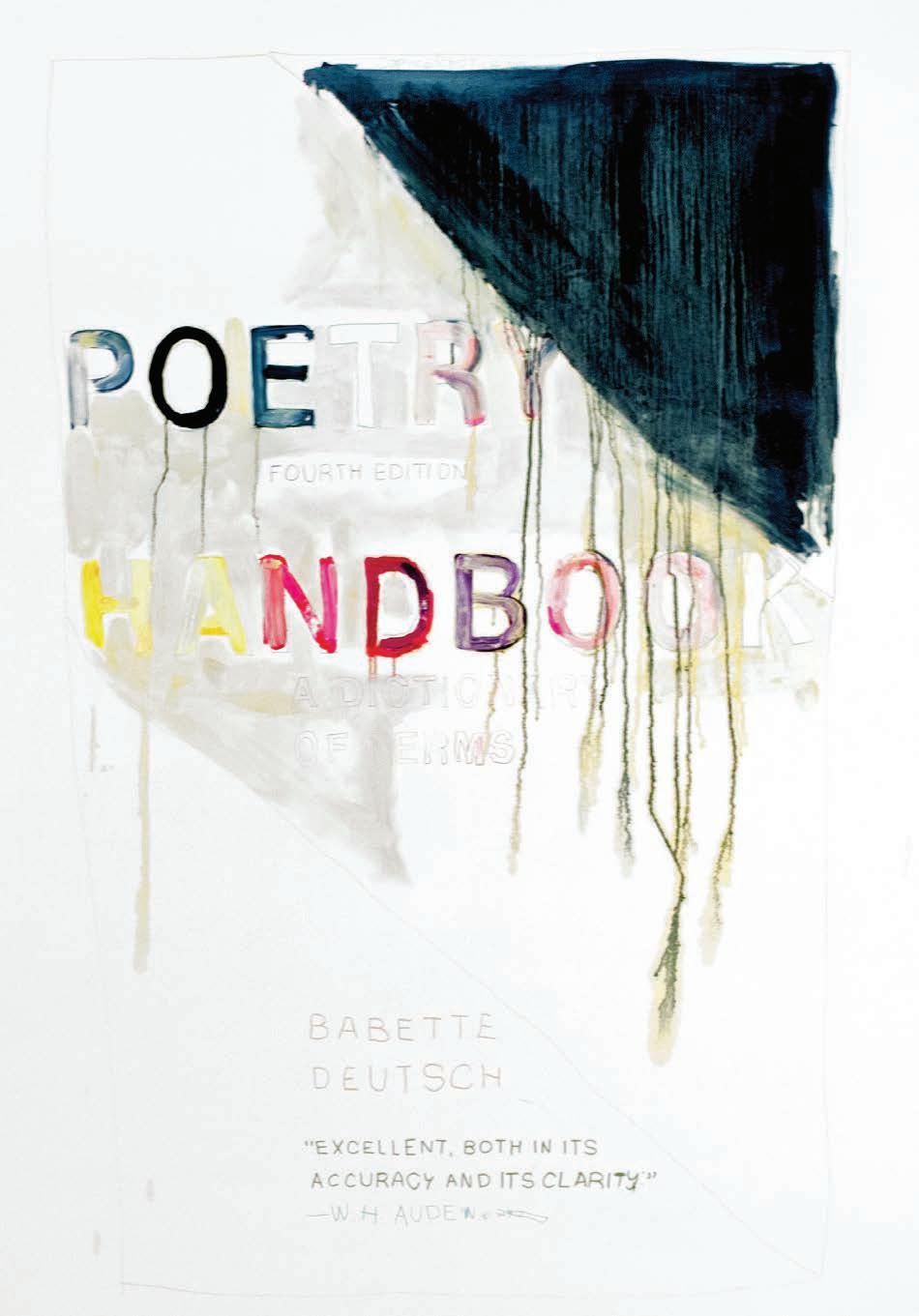

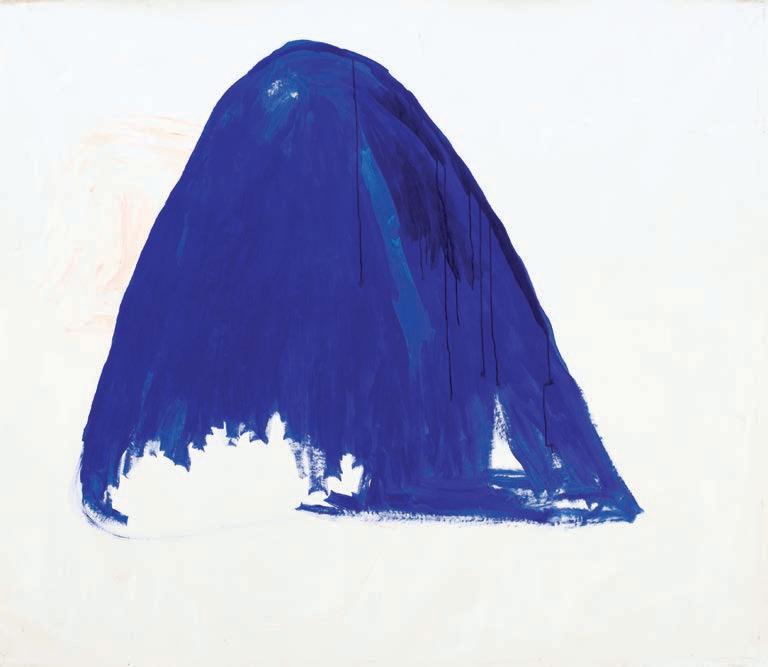

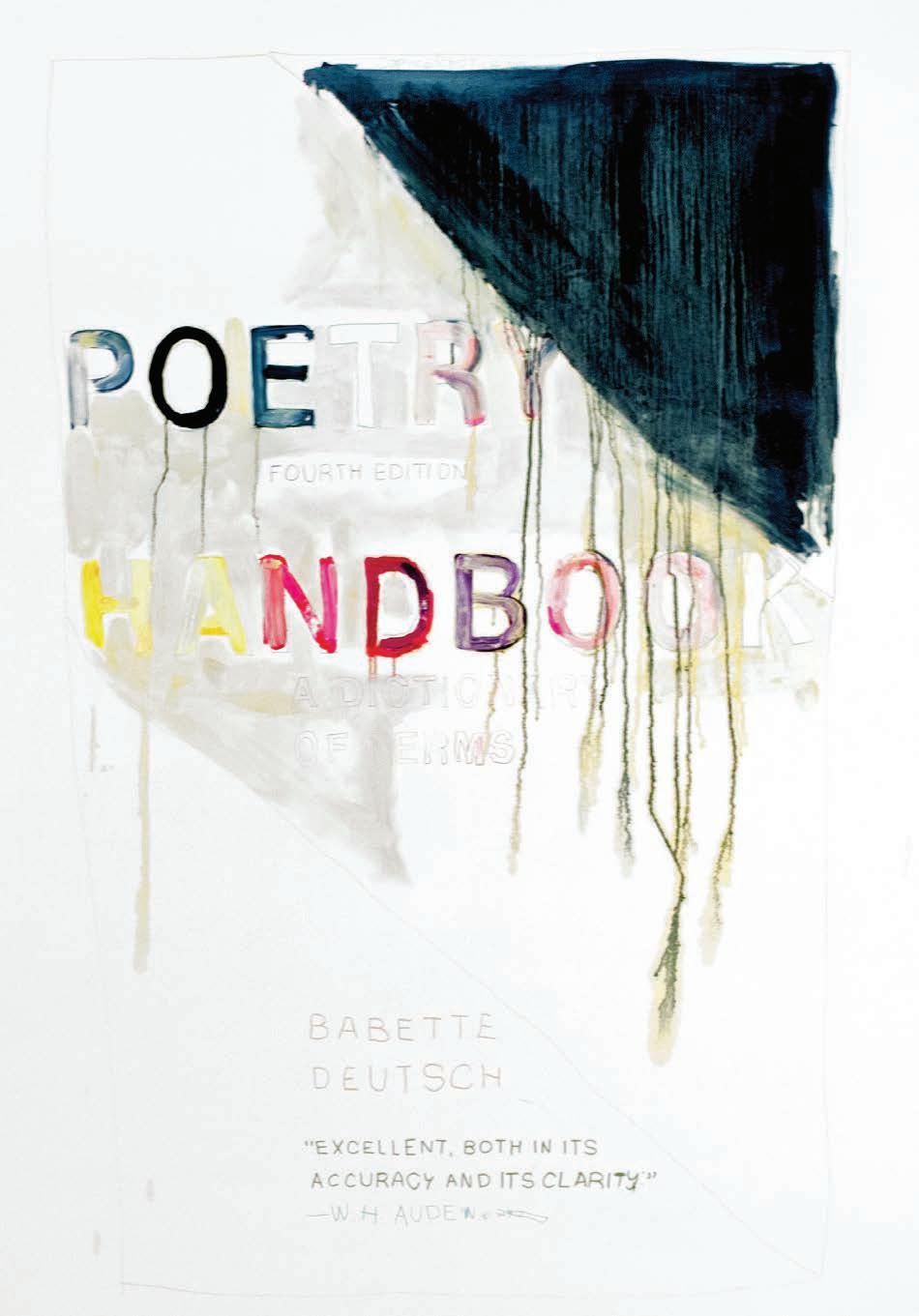

2009

Poesía [Poetry]

Acrílico sobre tela [Acrylic on canvas]

210 x 250 cmp.44-45

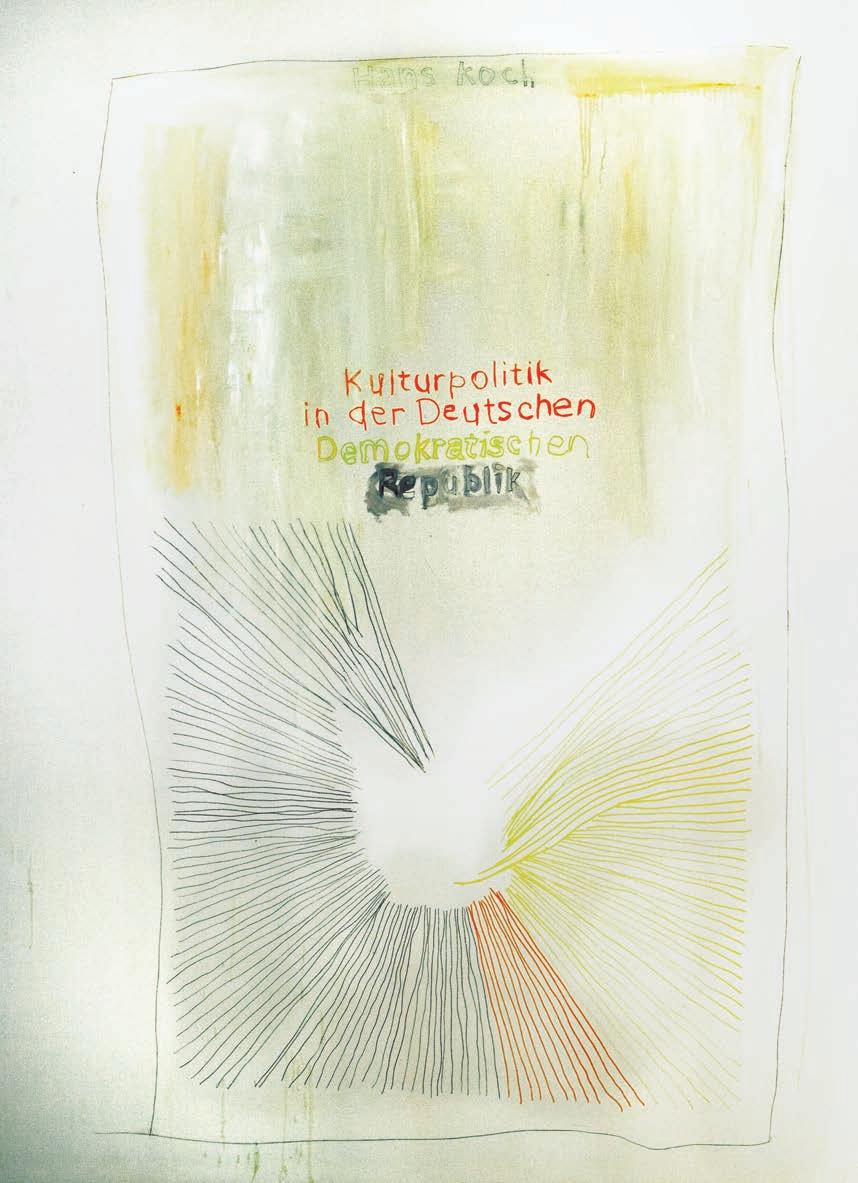

2009

Prosa [Prose]

Acrílico sobre tela [Acrylic on canvas]

203 x 218 cmp.46-47

2009

Prosa [Prose]

Acrílico sobre tela

[Acrylic on canvas]

200 x 270 cmp.49

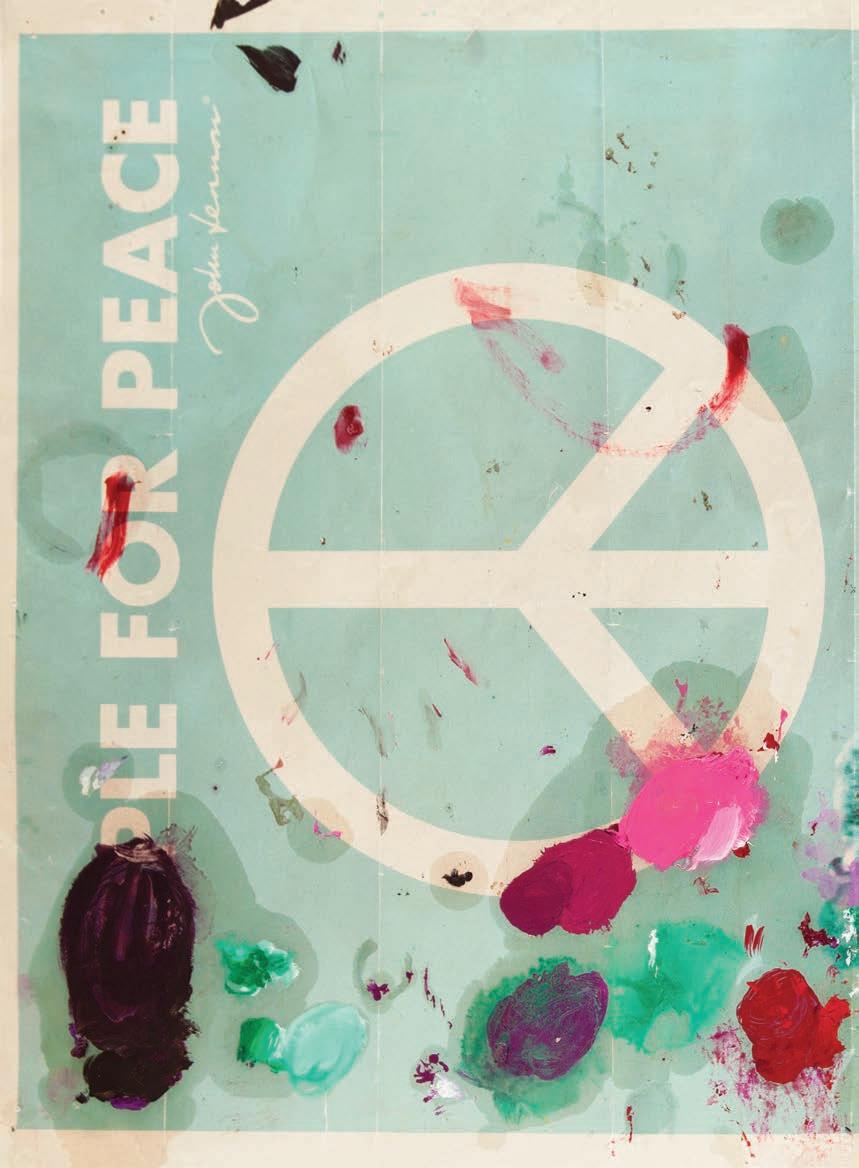

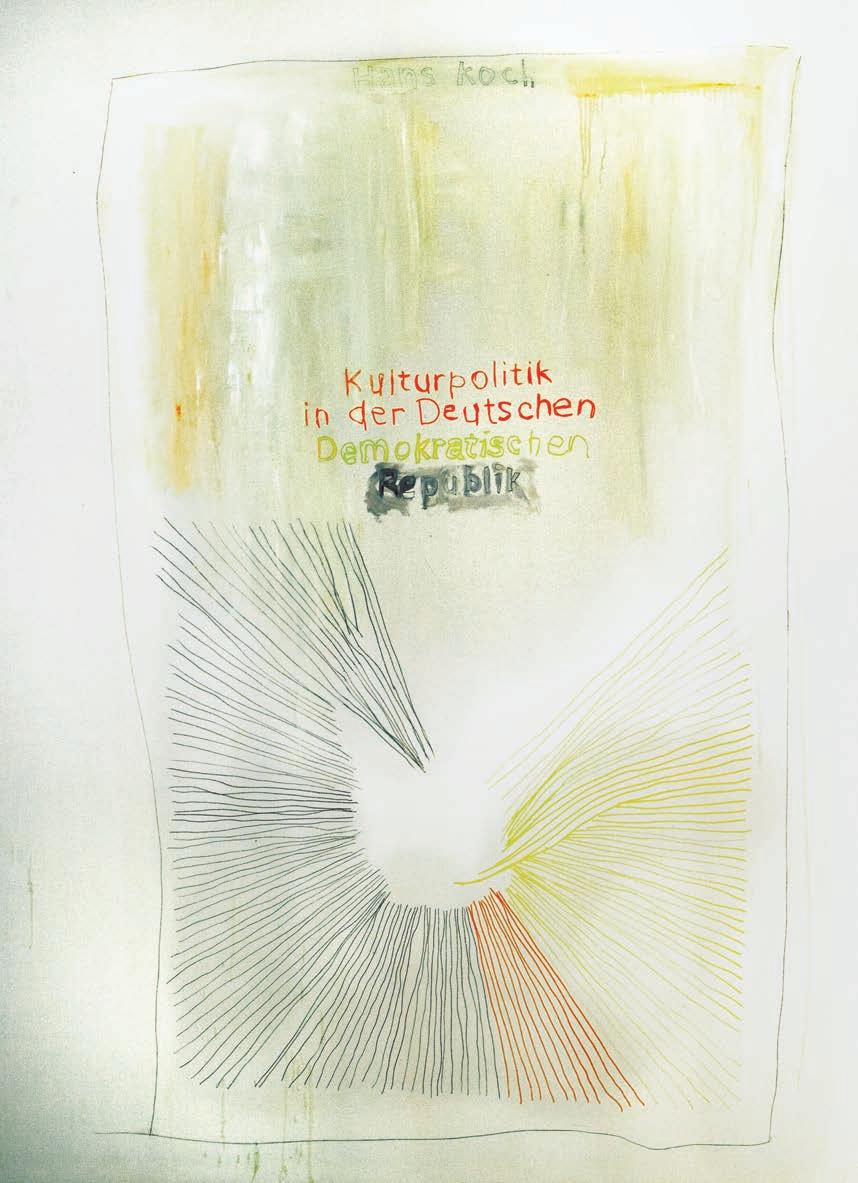

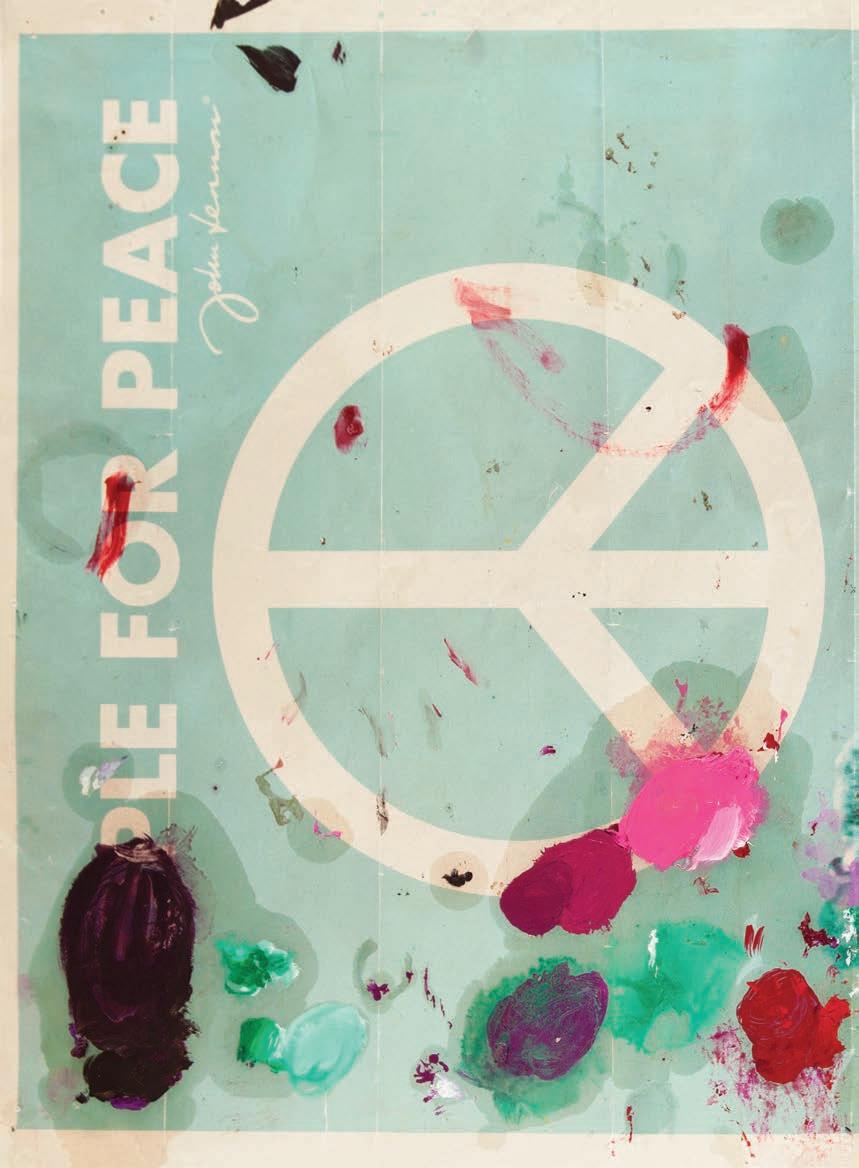

2013

Póster/Catálogo de la exposición La consagración de la primavera [Poster / Catalog for the exhibition The Consecration of Spring]

Óleo y acrílico sobre papel

[Oil paint and acrylic on paper]p.50-51

2013

El Vaticano

[The Vatican]

Óleo y lápiz

[Oil paint and pencil]

195 x 262 cmp.52

2013

Los tres desastres

[The Three Disasters] Óleo y marcador sobre tela

[Oil paint and marker on canvas]

190 x 236 cmp.53

2013

Los tres desastres

[The Three Disasters]

Óleo y marcador sobre tela

[Oil paint and marker on canvas]

200 x 264 cmp.55

2013

La consagración de la primavera

[The Consecration of Spring] Vista general de la muestra

[General view of the exhibition]p.56-57

2016

Yo en el futuro

[Me in the Future]

Óleo sobre sábana

[Oil paint on sheet]

200 x 140 cmp.59

2009

Yo en el futuro

[Me in the Future]

Acrílico sobre tela

[Acrylic on canvas]

210 x 160 cmp.60

2015

Yo en el futuro

[Me in the Future]

Marcador, óleo y lápiz sobre tela

[Marker, oil paint and pencil on canvas]

200 x 150 cm

p.61

2016

Yo en el futuro

[Me in the Future]

Cloro sobre tela

[Chlorine on canvas]

179 x 150 cmp.63

2013

Yo en el futuro

[Me in the Future]

Óleo y marcador sobre tela

[Oil paint and marker on canvas]

200 x 154 cmp.65

2016

Yo en el futuro

[Me in the Future]

Óleo sobre tela

[Oil paint on canvas]

243 x 160 cmp.67

2016

Yo en el futuro

[Me in the Future]

Cloro sobre tela

[Chlorine on canvas]

84,5 x 59 cmp.68

2016

Yo en el futuro

[Me in the Future]

Tela cosida

[Stitched fabric] 70 x 50 cmp.69

2016

“A negro, E blanca, I roja, U verde, O azul”

[A Black, E White, I Red, U Green, O Blue] Detalle [Detail]p.71, 73, 74-75

2019

Revólver [Revolver] Tela cosida

[Stitched fabric]

80 x 40 cmp.77

2016

Porque no saben lo que hacen [Because They Don’t Know What They’re Doing]

Óleo sobre tela

[Oil paint on fabric]

158 x 176 cm

p.78-79

2016

“A negro, E blanca, I roja, U verde, O azul”

[A Black, E White, I Red, U Green, O Blue]

Detalle [Detail]

p.80-81

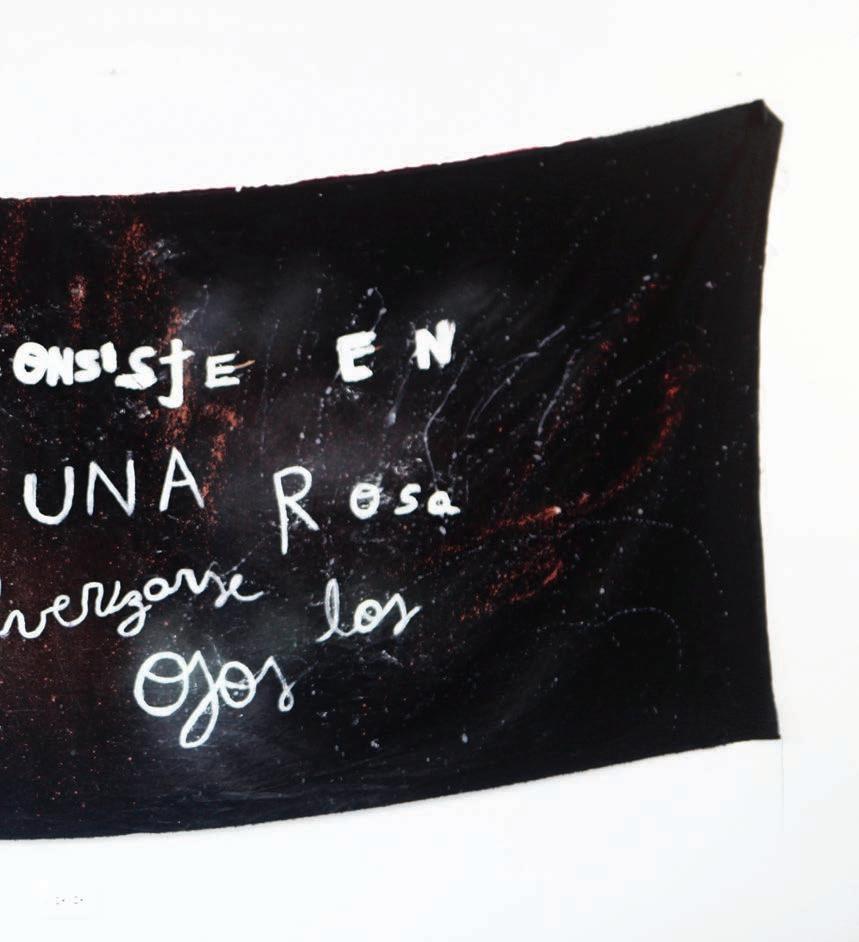

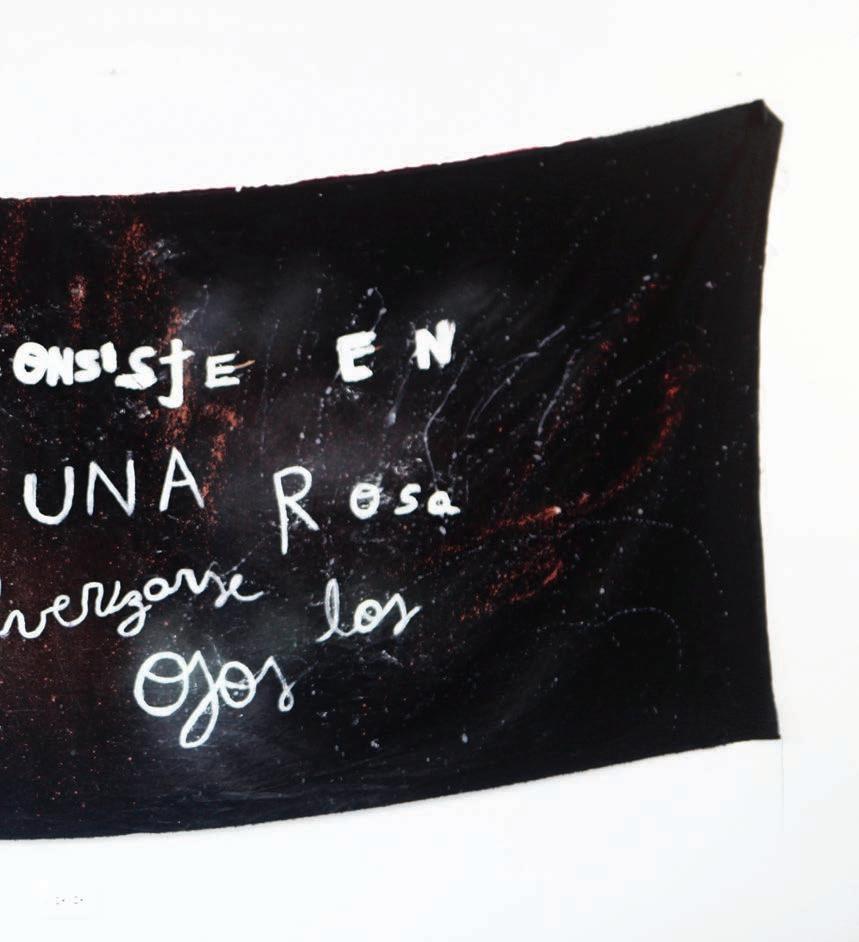

2016

La rebelión consiste... [The Rebellion Consists…] Óleo y lejía sobre tela [Oil paint and bleach on canvas]

150 x 300 cm

p.82

Nota aclaratoria de la artista: la bandera con la inscripción “Radical Feminist” fue hecha en el año 2016 en la ciudad de Lima. En ese momento había manifestaciones impulsadas por “Ni una menos”. Entendía el concepto como una radicalización de las ideas del feminismo de una manera que conectara a otras minorías, y como cuestionamiento de toda esencialización de la identidad. De ninguna manera comparto -y de hecho repudio- las ideas transfóbicas de lo que se conoce como “radfem”.

Explanatory note from the artist: The banner reading ‘Radical Feminist’ was made in 2016 in Lima where a number of ‘Ni una menos’ demonstrations were being held. I saw the concept as a radicalization of feminist thought in a way that would include other minorities, challenging narrow formulations of identity. In no way do I condone – in fact I vehemently reject –the transphobic stance known as ‘radfem’.

2016

“A negro, E blanca, I roja, U verde, O azul”

[A Black, E White, I Red, U Green, O Blue]

Detalle [Detail]

p.83-84, 86-87, 88-89, 90

2016

El origen del mundo [The Origin of the World] Óleo sobre tela cosida [Oil paint on sewn fabric] 158 x 160 cmp.91

2016

“A negro, E blanca, I roja, U verde, O azul”

[A Black, E White, I Red, U Green, O Blue]

Detalle [Detail]p.92-93, 95, 96-97

2016

Porque no saben lo que hacen [Because They Don’t Know What They’re Doing]

Tela [Fabric]p.98

2016

Florecen fuera del campo de batalla [They Flourish Beyond the Battlefield]

Óleo sobre tela

[Oil paint on fabric] 180 x 190 cmp.99

2016

“A negro, E blanca, I roja, U verde, O azul”

[A Black, E White, I Red, U Green, O Blue]

Vista general de la muestra

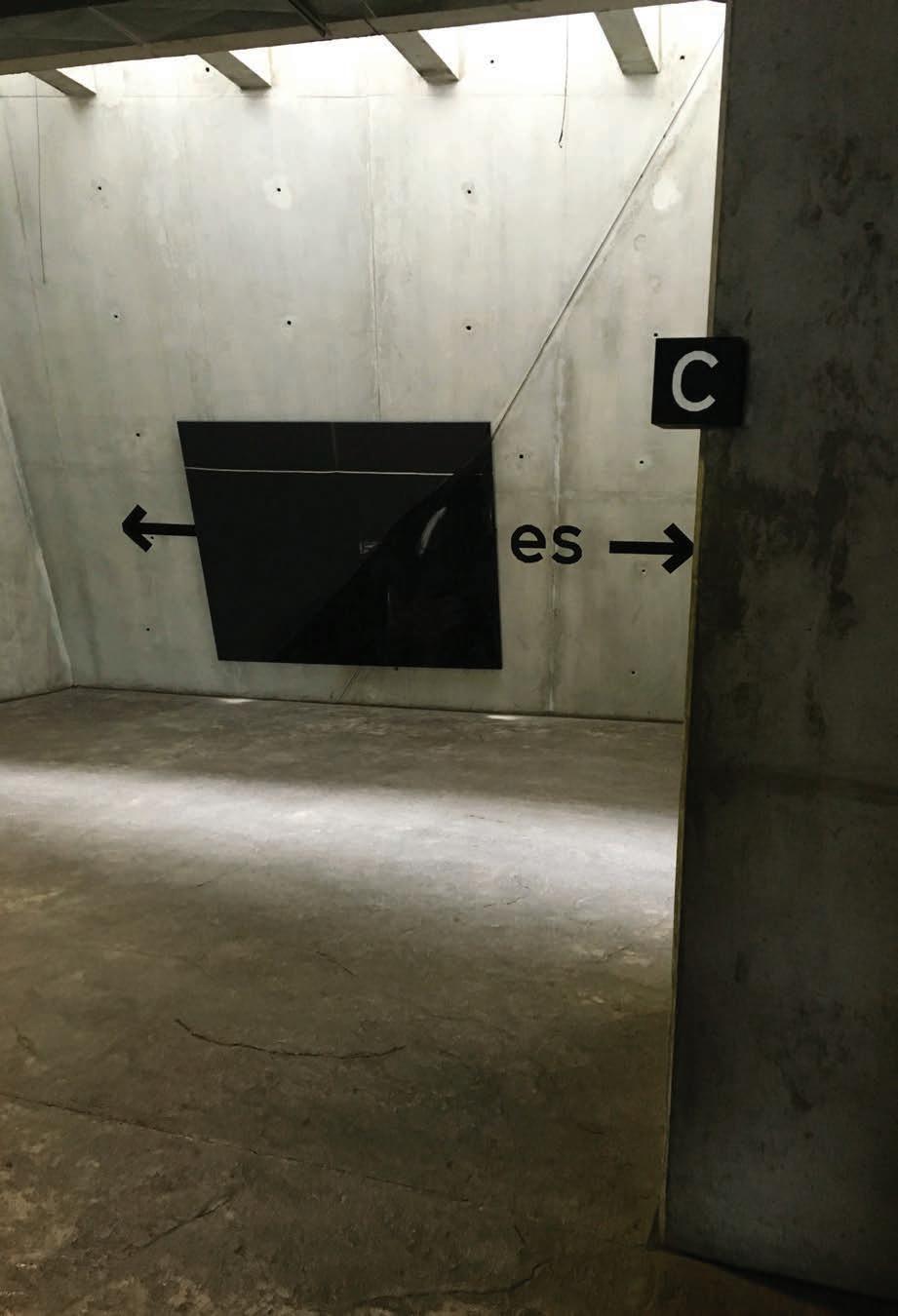

[General view of the exhibition]p.101

2016

“A negro, E blanca, I roja, U verde, O azul”

[A Black, E White, I Red, U Green, O Blue]

Vista general de la muestra

[General view of the exhibition]p.102

2016

“A negro, E blanca, I roja, U verde, O azul”

[A Black, E White, I Red, U Green, O Blue]

Óleo sobre tela

[Oil paint on canvas]

156 x 210 cmp.103

2016

Pensar que todo es parte de un gran plan

[The Belief That it’s All Part of a Grand Plan]

Tela cosida

[Sewn fabric]

50 x 80 cmp.104

2016

“A negro, E blanca, I roja, U verde, O azul”

[A Black, E White, I Red, U Green, O Blue]

Detalle

[Detail]

p.105, 107, 108, 109, 110

2016

De su pecho el atrás

[From the Chest, Behind]

Tela y red

[Net and fabric]

128 x 78,5 cmp.111

2016

Póster/Catálogo de la muestra

“A negro, E blanca, I roja, U verde, O azul”

[Poster / Catalog for the exhibition “A Black, E White, I Red, U Green, O Blue”]p.112-113

2016

Porque no saben lo que hacen [Because They Don’t Know What They’re Doing]

Óleo sobre tela cosida

[Oil paint and sewn fabric] 158 x 221 cmp.114-115

2009

Póster/Catálogo de la muestra

Yo soy más fuerte que yo [Poster / Catalogue for the exhibition I’m Stronger than Me] Ph: Nicolás Vasen, Jazmín Lópezp.116-117

2015

Dios es hermosa

[God is a Woman and She is Beautiful]

Marcador, óleo y lápiz sobre tela

[Marker, oil paint and pencil on canvas]

203 x 280 cmp.118-119

2013

Coreografía

[Choreography] Óleo sobre tela

[Oil paint on canvas] 280 x 200 cmp.120

2014

No te mueras en mi casa

[Don’t Die in My House] Óleo sobre tela

[Oil paint on canvas] 250 x 210 cmp.121

2009

Lo negro y yo

[Black and Me]

Óleo sobre tela

[Oil paint on canvas]

198 x 325 cmp.123

2010

No te mueras en mi casa

[Don’t Die in My House] Óleo y marcador sobre lienzo

[Oil paint and marker on canvas]

200 x 170 cmp.125

2013

No te mueras en mi casa

[Don’t Die in My House] Óleo sobre lienzo

[Oil paint on canvas]

200 x 270 cmp.126-127

2015

No te mueras en mi casa

[Don’t Die in My House] Óleo sobre tela

[Oil on canvas]

180 x 210 cmp.128-129

2011

Pero el mensaje está muerto

[But the Message is Dead] Fotografía digital

[Digital Photograph]p.131

2011

Vos como un ángel

[You as an Angel] Óleo sobre tela

[Oil paint on canvas]

210 x 510 cm

p.132-133

2009

Good Year

Acrílico, marcador y crayón sobre tela

[Acrylic, marker and crayon on fabric]

203 x 242 cmp.135

2015

Sin título

[Untitled]

Marcador, óleo y lápiz sobre tela

[Marker, oil paint and pencil on canvas]

205 x 237 cm

p.137

2016

Celeste [Light Blue] Óleo sobre tela

[Oil paint on canvas]

180 x 240 cm

p.138-139

2015

Sin título [Untitled]

Marcador, óleo y lápiz sobre tela [Marker, oil paint and pencil on canvas]

195 x 250 cmp.141

2013

Espejismo (Goya) [Mirage (Goya)] Óleo sobre tela [Oil paint on canvas] 185,5 x 201 cmp.142-143

2013 Excelente [Excellent]

Marcador y lápiz sobre tela [Marker and pencil on canvas] 270 x 200 cmp.144 -145

2013 Oktubre

Marcador y lápiz sobre tela [Marker and pencil on canvas] 190 x 264 cmp.146 -147

2008

Yo soy mas fuerte que yo [I’m Stronger than Me]

Acrílico sobre tela [Acrylic on canvas] 250 x 160 cmp.148

2007

Animal yo [Animal Me]

Acuarela sobre papel [Watercolor on paper] 40 x 30 cmp.149

2010

Prefiero dormir pensando en nosotros dos que dormir con vos [I’d Rather Sleep Thinking About Us Both Than Sleep With You]

Acrílico sobre tela [Acrylic on canvas] 210 x 240 cmp.150-151

2010

Sin título (pareja) [Untitled (couple)]

Acuarela sobre papel [Watercolor on paper] 68,5 x 55 cmp.153

2010

El tiempo todo junto [Time All Together]

Acrílico sobre pañuelo de seda [Acrylic on silk scarf] 95 x 95 cmp.155

2015

Póster / Catálogo de la exposición La Gravedad y la Gracia [Poster / Catalog for the exhibition Gravity and Grace]p.157

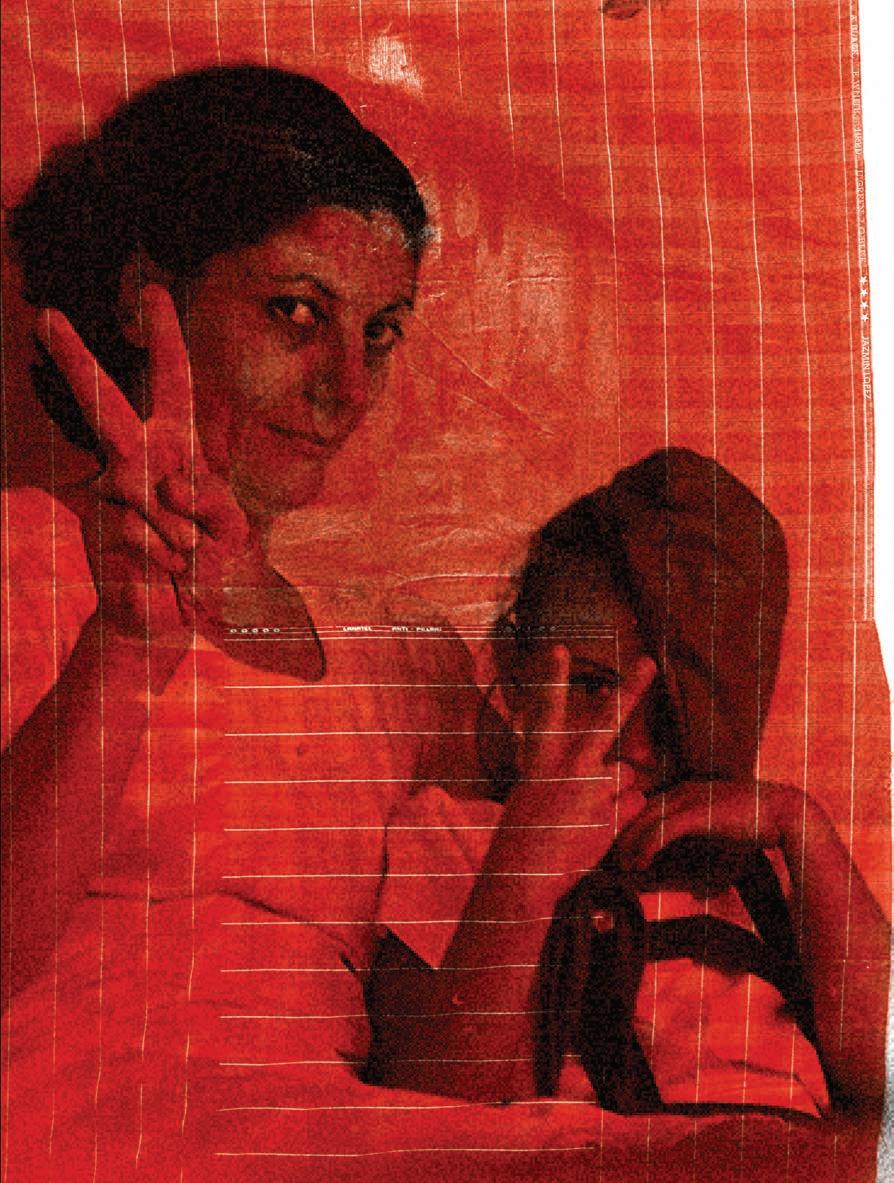

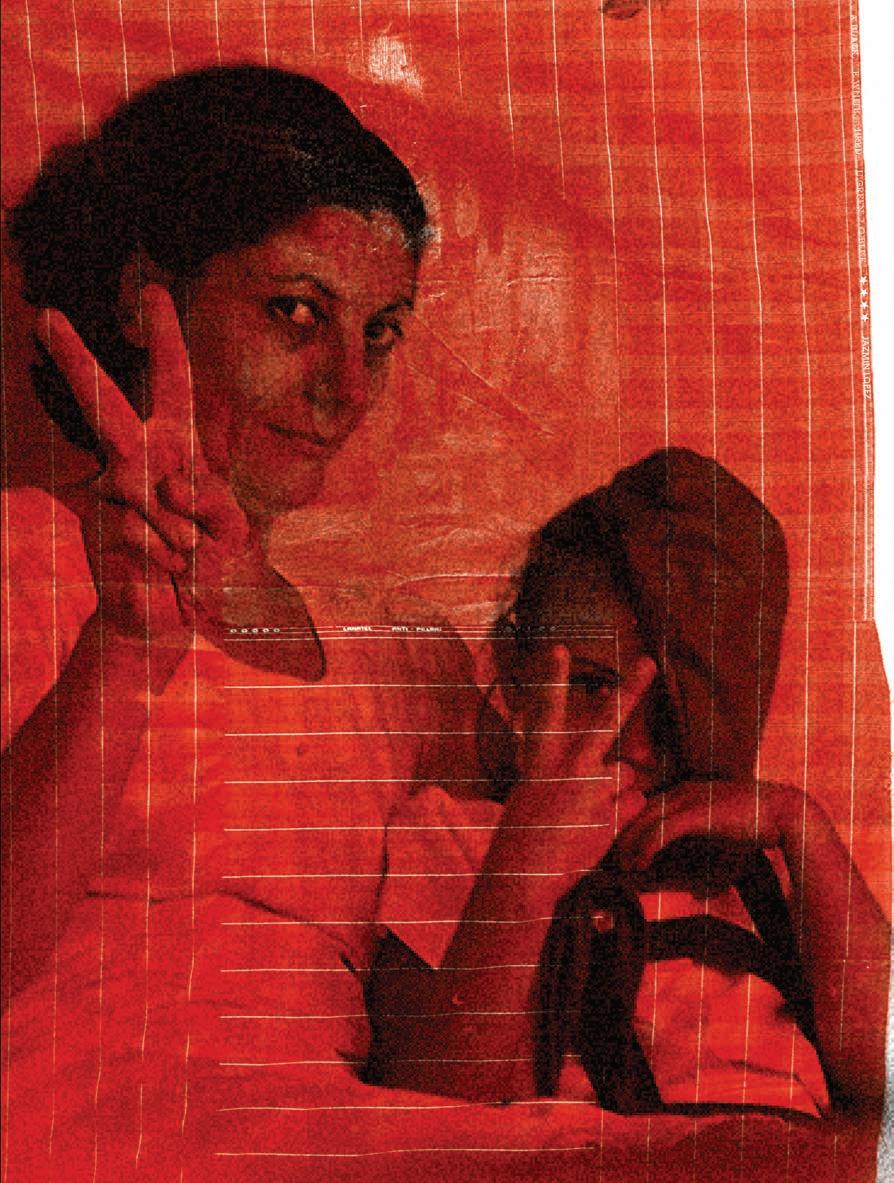

0000

Foto de archivo Montonero [Montonero photograph archive]p.159

2016

Teatro antidisturbios [Anti-Disturbance Theater] Óleo y esmalte sobre lino [Oil paint and enamel on linen] 150 x 300 cmp.160-161

2016

Y nadie me lo dice [And Nobody Tells Me] Óleo sobre tela [Oil paint on canvas] 153 x 171 cmp.163

2017

Porque no saben lo que hacen [Because They Don’t Know What They’re Doing]

Óleo y lavandina sobre tela [Oil paint and bleach on canvas] 110 x 210 cmp.164-165,166-167

2016

Canción cantada mientras se ejecuta un trabajo físico difícil [Song Sung While Doing Arduous Physical Work]

Tiza y agujeros sobre terciopelo [Holes and chalk on velvet] 150 x 150 cmp.169

2017

Verónica, si esto es un hombre [Verónica, If This is a Man] Espejo cortado [Broken mirror] 100 x 290 cmp.172-173, 174-175

2019

Soñar es la actividad estética más antigua [Dreaming is the oldest aesthetic activity]

Tela y madera [Canvas and wood] Vista de instalación [Installation view] Medidas variables [Variable measures]p.176-177

2019

Soñar es la actividad estética más antigua [Dreaming is the oldest aesthetic activity]

Tela y madera [Canvas and wood] Detalle [Detail]p.178, 179

2013

Leones, vista de sala de la exposición [Lions, general view of the exhibition]p.181

2013

De la serie “Leones” [From the “Lions” series] Impresión digital sobre papel [Digital print on paper]

87 x 60 cmp.182

2013

De la serie “Leones” [From the “Lions” series] Impresión digital sobre papel [Digital print on paper] 88 x 60 cmp.183, 184

2013

De la serie “Leones” [From the “Lions” series] Impresión digital sobre papel [Digital print on paper] 60 x 88 cmp.185

Jazmín López

Nace en Buenos Aires en octubre de 1984. Estudia cine en la Universidad del Cine de Buenos Aires. Realiza clínica de obra con Jorge Macchi y Guillermo Kuitca, este último en la Universidad Torcuato Di Tella de Buenos Aires. Desde 2009, su trabajo es representado por Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte. A lo largo de 2018, 2019 y 2020 realiza una Maestría en Studio Art en NYU, Nueva York, bajo el asesoramiento de Fred Moten, Boris Groys y Maureen Gallace.

Entre sus exposiciones se destacan: On Struggling to Remain Present When You Want to Disappear, curada por Nana AduseiPoku, OCAT, Shanghai, 2018; Ese algo que está a medio camino entre el color de mi atmósfera típica y la punta de mi realidad, curada por Juan Canela y Stefanie Hessler, Tabacalera, Madrid Arco, 2017, y Creando tonos de piel para pinturas al óleo, curada por Jens Hoffmann, Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte, Solo Project ArtBo, Bogotá, 2016.

En 2016, lleva a cabo la residencia FLORA ars + natura en Bogotá y exhibe Fire and Forget, curada por Ellen Blumenstein y Daniel Tyradellis, KW, KunstWerke, Berlín, 2015, y One Sentence Exhibition, curada por Jacob Fabricius en Kadist Art Foundation.

En 2015 también participa de la residencia KunsWerke en Berlín y exhibe La gravedad y la gracia en Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte, Buenos Aires.

En 2014, realiza un Solo Project en ParC curado por José Roca en Lima. También el Solo Project curado por Catherine Petitgas en Pinta, Londres.

En 2013 presenta Leones en el Centro George Pompidou, París, en el Instituto KW Berlín y en New Directors New Films en MoMA y Lincoln Center, entre otros. Además, expone La consagración de la primavera, curada por Sonia Becce en Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte y María María en la 70 Bienal de Venecia.

Su trabajo es publicado en Variety y New York Times, entre muchos otros medios de comunicación.

Jazmín López

Was born in Buenos Aires in October 1984. She studied Film at the Universidad del Cine in Buenos Aires and attended art clinics run by Jorge Macchi and Guillermo Kuitca, the latter at Universidad Torcuato Di Tella in Buenos Aires. Since 2009, her work has been represented by Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte. In 2018 she began a three year Masters course at NYU, New York, under the guidance of Fred Moten, Boris Groys and Maureen Gallace. Her exhibitions include: On Struggling to Remain Present When You Want to Disappear, curated by Nana Adusei-Poku, OCAT, Shanghai, 2018; Ese algo que está a medio camino entre el color de mi atmósfera típica y la punta de mi realidad (The Thing Halfway Between the Colour of My Normal Atmosphere and the Tip of My Reality), curated by Juan Canela and Stefanie Hessler, Tabacalera, Madrid Arco, 2017, and Creando tonos de piel para pinturas al óleo (Creating Skin Tones for Oil Paint), curated by Jens Hoffmann, Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte, Solo Project ArtBo, Bogotá, 2016.

In 2016, she was invited to a residency at FLORA ars + natura in Bogotá and exhibited Fire and Forget, curated by Ellen Blumenstein and Daniel Tyradellis, at KW, KunstWerke, Berlin and One Sentence Exhibition, curated by Jacob Fabricius at the Kadist Art Foundation.

In 2015 she took part in the KunstWerke residency in Berlin and exhibited La gravedad y la gracia (Gravity and Grace) at Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte, Buenos Aires.

In 2014, she held Solo Project, curated by José Roca, at ParC in Lima and Solo Project, curated by Catherine Petitgas, at Pinta, London.

In 2013 she presented Leones (Lions) at the Centro George Pompidou, Paris, at the Instituto KW, Berlin and New Directors New Films at MoMA and the Lincoln Center, among other venues. She also exhibited La consagración de la primavera (The Consecration of Spring), curated by Sonia Becce, at Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte and María María at the 70th Venice Biennale. Her work has been published in Variety and the New York Times, among many other media outlets.

211

IDEA ORIGINAL

/ORIGINAL IDEA

Ailin Staicos & Ruben Mira

FANTASY Comunicación

COORDINACIÓN

EDITORIAL

/EDITORIAL

COORDINATION

Ailin Staicos

ENTREVISTA

/INTERVIEW

Ruben Mira

DISEÑO EDITORIAL

/GRAPHIC DESIGN

María Sibolich

TRADUCCIÓN

/TRANSLATION

Kit Maude

CORRECCIÓN DE TEXTOS

/TEXT EDITOR

Studio Glosa

FOTOGRAFÍA

/PHOTOGRAPHER

Juan Canela

Ignacio Iasparra

Nicolás Vasen

Vanina Scolavino

RETOQUE FOTOGRÁFICO

/DIGITAL PHOTO EDITOR

Paula Rubinstein

IMPRENTA

/PRINTING HOUSE

Contartese Gráfica

Agradecimientos / Acknowledgements

Patricio Orellana, Mathilde Andre Fouet, Sergio López, Juan Canela, Gianina Covezzi, Tiziana Pierri, Jacqueline Golbert, Vanina Scolavino, Ailin Staicos, Ruben Mira, Orly Benzacar, Mora Bacal y a todo el staff de Ruth Benzacar.

Este libro se hizo posible gracias al apoyo de Balanz.