Tableros de madera, cuerina, caballetes, objetos y artefactos lumínicos. Wooden boards, leatherette, trestles, objects and light artefacts.

“Sir Francis Bacon en su primer libro de aforismos (1625) señala lo siguiente: Aquellos que han cultivado las ciencias han sido hombres de experimentos u hombres de dogma. Los hombres de experimentos son como la hormiga, solo reúnen y utilizan; los razonadores se parecen a las arañas, que fabrican telarañas con su propia sustancia. A pesar de su tono de menosprecio, Bacon ve en ambos ciertas virtudes y recomienda un camino intermedio, simbolizado por la abeja, que junta materiales en las flores del jardín y de los campos, pero los transforma y los digiere gracias a su propio poder…” ( Martin Hollis, Invitación a la filosofía, Barcelona, Ariel, 1986, p. 94). Joglar reconoce en esta cita sus modos de trabajo y procesos artísticos. Como la hormiga, recolecta y almacena. Como la araña, teje redes de significados a partir de la disposición de objetos expuestos. Y como abeja, transforma, muta o varía sustancias o significados

“In his first book of aphorisms (1625), Sir Francis Bacon writes: ‘Those who have handled sciences have been either men of experiment or men of dogmas. The men of experiment are like the ant, they only collect and use; the reasoners resemble spiders, who make cobwebs out of their own substance. But the bee takes a middle course: it gathers its material from the flowers of the garden and of the field, but transforms and digests it by a power of its own. Not unlike this is the true business of philosophy; for it neither relies solely or chiefly on the powers of the mind, nor does it take the matter which it gathers from natural history and mechanical experiments and lay it up in the memory whole, as it finds it, but lays it up in the understanding altered and digested...’

(Martin Hollis, An Invitation to Philosophy, US, Wiley-Blackwell, 1997.) Joglar uses this quote to illustrate his different working methods and artistic processes. Like the ant, he gathers and stores. Like the spider, he weaves webs of meanings in his layouts of different objects. And like the bee he transforms, changes and varies substances and meanings.

Papel, madera y objetos escolares. Paper, wood and stationary.

La ilustración científica, específicamente referente a la geografía, y su grado de abstracción para representar distintos modelos geográficos, inspiró a Joglar a manifestar una serie de ejercicios como si fueran ilustraciones en papel, madera y objetos escolares, como escuadras, algunas veces encolados para fijar la forma en otros solo superpuestos. Resmas de papel de distintos colores conforman estas nuevas geografías, esculturas, en el sentido de esculpir una forma a partir de un material preexistente.

Scientific illustration, especially in the field of geography and its abstract symbolism, inspired Joglar to produce a series of exercises involving illustrations on paper, wood and stationary such as set squares. These are occasionally placed together to establish a shape superimposed over the others. Reams of coloured paper create new geographies and sculptures, producing new forms from pre-existing material.

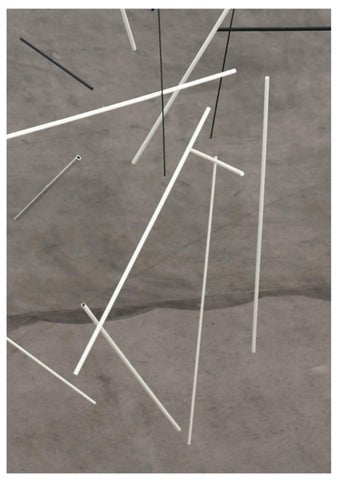

Barriletes, varillas de aluminio, tela rip-stop, cable y mosquetones de acero. Medidas variables.

Kites, aluminium tubes, rip-stop canvas, cable and steel snap rings. Varying measurements.

La carrera del aire fue realizada en el año 2010 como una obra site especific para el atrio del edifico corporativo del Banco Supervielle. Se compone de diez barriletes diseñados a partir del original modelo Marconi. Lleva este nombre en referencia a Guillermo Marconi (Bolonia, 1874—Roma, 1937), ingeniero eléctrico, empresario e inventor italiano conocido como uno de los más destacados impulsores de la radiotransmisión a larga distancia por el establecimiento de la Ley de Marconi así como por el desarrollo de un sistema de telegrafía sin hilos (T.S.H.) o radiotelegrafía que en 1909 ganó el Premio Nobel de Física.

Air Race was made in 2010 as a site specific work for the atrium of the Banco Supervielle headquarters. It consisted of ten kites designed according to the original Marconi model, named for Guillermo Marconi (b. Bologna, 1874-1937), the Italian inventor, electrical engineer and businessman known best as one of the leading pioneers of long distance radio broadcasting, who was responsible for Marconi’s Law and the wireless telegraph system, or radio-telegraph, which earned him the Noble Prize for Physics in 1909.

La paleta de colores usada refiere al pintor Piet Mondrian (Amersfoort, 1872—Nueva York, 1944) quien, al dedicarse a la abstracción geométrica, buscaba encontrar la estructura básica del universo a partir del uso de colores primarios, blanco y negro, y planos geométricos.

La carrera del aire es la obra de mayor escala del artista y su nombre se refiere a los conceptos de levedad e ingravidez con las que trabaja.

The colour palette is a reference to Piet Mondrian (Amersfoot, 1872-1944) who used geometric abstraction to represent the basic structure of the universe through primary colours, black, white and geometric planes.

Air Race was the artist’s largest scale work. The name refers to his interest in the concepts of lightness and lack of gravity.

Rosarios luminosos y tanza. Medidas variables.

Glowing rosaries and nylon cord. Variable measurements.

La palabra “red” remite a diversos significados. Uno de ellos la considera una estructura con un patrón característico: el hombre fabrica redes utilizando materiales como el cáñamo, el algodón, el nailon y otras fibras naturales o sintéticas. También se la utiliza como sinónimo de Internet: una red social. La obra de Joglar está conformada por una red de pesca de tipo mediomundo realizada a partir del patrón que ofrecen los rosarios católicos. La palabra “rosario” refiere a un vergel de rosas y es un modo de oración muy difundida en la fe católica. Su nombre se debe a una tradición según la cual un santo religioso se imaginaba que cada vez que rezaba un Ave María a la Virgen, saldría de sus labios una rosa que sería recogida por la misma Virgen, quien a su vez formaría con cada una de ellas una corona y la colocaría sobre la frente de su devoto.

The word ‘net’ has different meanings. Firstly, there is distinctive structure seen in artificial nets made from materials such as hemp, cotton, nylon and other natural and synthetic fibres. It is also a term for the Internet and social networks. Joglar’s work consists of a half-globe fishing net made using a pattern found in Catholic rosaries. The word ‘rosary’ refers to a rose garden and is a widespread Catholic prayer method. Its name arises from the legend in which a saint imagined that every time he said a Hail Mary a rose would emerge from his mouth to be picked up by the Virgin Mary, who would use it to make a crown that would then be placed on the worshipper’s forehead.

La obra Red de Joglar reproduce un fuerte significado de alabanza, amor y respeto, y sugiere un importante poder de protección a través de la multiplicación de los elementos religiosos y sus asociaciones.

Joglar’s artwork, Net, has powerful connotations related to praise, love and respect, suggesting a protective power through the proliferation of religious elements and their associated meanings.

Fue realizada para la 29ª Bienal de Arte de Pontevedra, España, OF-FORA, y actualmente pertenece a la colección David Gorodisch.

The artwork was made for the 29th Pontevera Biennial in Spain, OF-FORA, and is currently a part of the David Gorodisch Collection.

Fragmentos

de una larga entrevista con Daniel Joglar

Por Ruben Mira

¿Quién?

Dedicarme al arte es algo que encontré en el andar, buscando algo que hacer en la vida, ciertos sentidos para ciertos momentos. No empecé de chiquito, no es que ya desde la infancia me había propuesto ser artista, sino que me surgió después de pasar por otras cosas. En el secundario estudié para técnico químico, más tarde hice un año y medio de bioquímica, empecé a estudiar filosofía, hice otro año y medio, dejé, y en ese recorrido llegué a la escuela de arte que es, digamos, adonde me quedé. Siempre comento que no soy un artista de vocación. Es más, a veces me pregunto si en realidad soy un artista.

¿Qué sería la vocación? ¿Qué es la vocación? ¿Es algo que ya viene dado en uno?, ¿o que se encuentra? En mi casa no fui cultivado o educado en las artes. Mis viejos eran dos personas comunes y corrientes, comerciantes, gente laburante. No me mandaron a una escuela de dibujo, no me llevaban a ver exposiciones. Así que el arte no era un lugar predestinado: lo fui encontrando como lugar de destino.

En la escuela, conocer el trabajo de Joseph Beuys me marcó mucho, también Duchamp. Después, los artistas con los que entré en contacto cuando vine a vivir a Buenos Aires: Román Vitali, Ruy Krygier, Mónica van Asperen, Marina de Caro, Dino Bruzzone, Alejandra Seeber, Jane Brodie y Sergio Avello. Avello fue muy importante para mí. Él era de Mar del Plata

¿Cuándo?

como yo pero lo conocí acá, en la capital. En Buenos Aires descubrí el trabajo de los minimalistas. Me gustaban mucho Sol Le Witt, Donald Judd, Robert Morris. Por entonces empecé a conocer la obra de algunos artistas brasileños. Me encantaron Waltercio Caldas, Brígida Baltar y Mira Schendel. Ellos tenían, a mi entender, cierta relación con los minimalistas, pero incorporaban la sensualidad y lo poético. Después me fijé un poco más en los contemporáneos, los postminimalistas o neoconceptuales: por ejemplo, la artista Rivane Neuenschwander. Hoy en día, me atrae el trabajo que hace Jason Dodge con la percepción, con la luz y los objetos.

Tal vez nunca me interesó estrictamente estudiarlos. Puedo decir quiénes son esos pintores o artistas, cuáles son sus técnicas, cómo trabajan, pero eso no me parece relevante. Tampoco tengo necesidad de referenciarme directamente en ellos. Para mí es más importante aproximarse al clima de la obra y al clima de trabajo que sugiere la obra. O tal vez la problemática puede desdoblarse: el estudio es un aprendizaje consciente que suele conducir a una actitud inteligente, discursiva. El clima, en cambio, es un espacio en el que se habita corporalmente, a donde se puede estar de una manera propia y que suele provocar una asimilación sensible, sensual.

Encontré en el arte un espacio que me permitió desarrollar muchas cuestiones, un espacio de libertad. Cuando lo pienso bien me doy cuenta de que alguna de esas cosas a lo mejor las traje de mi familia, aportó a mi obra algo de lo cotidiano, del hogar, de la casa. Esos órdenes que establezco, cómo presentar las cosas, cómo disponerlas, cómo ubicarlas, tienen que ver con mi vieja. Yo veía ese modo que ella tenía de estar en la casa ordenando y acomodando cosas y actividades. Al principio no lo sentía así pero tiempo después reconocí esa influencia en mi trabajo. Cierto sentido de reubicación.

En el año 1987 comencé los estudios en la Escuela Martín Malharro de artes visuales de Mar del Plata. Hice la carrera de realizador y también el profesorado. Egresé y me quedé en Mar del Plata. Ese es un momento importante. El otro momento que considero significativo es el año 97 cuando me eligieron para participar de la Beca Kuitca. La primera parte fue de formación, una formación de nivel terciario, pero después llegó la segunda etapa de ese proceso cuando vine a Buenos Aires y empecé a involucrarme en el circuito.

La escuela de artes visuales fue una especie de experimento para mí buenísimo. En los años en los que estudié, un grupo de docentes armó un plan que se llamaba “Plan Piloto” para el que tomaban la idea de integración de talleres. En los primeros tres años cursábamos los talleres por separado –con un profesor de pintura, uno de dibujo, uno de grabado– y los últimos años eran de integración total. Entre todos te ayudaban a llevar adelante las ideas que querías trabajar. Esa etapa formativa me produjo una gran motivación.

Mi trabajo, o mi obra (me cuesta decirle “obra” a mi trabajo), en Buenos Aires empezó a verse a fines de los 90. Digamos que ahí tomó impulso mi desarrollo más profesional como artista. No sé qué palabra ponerme, si considerarme artista o profesional porque no me reconozco en ese discurso. Desde esa época, y con la beca, pude anclarme no en una corriente específica sino en un espacio. Más concretamente desde el 97 en adelante. Pero lo que hacía no tenía nada que ver con el tipo de arte que se hizo en los años 90. Formaba parte de la Beca Kuitca con un montón de artistas que en ese momento estaban ligados a la camada del Centro Cultural Rojas. Sin embargo, no encuentro relación entre esa movida y mi producción.

En los 90 venía a Buenos Aires a ver muestras, recuerdo en particular las instalaciones. Ya estaba trabajando con el espacio en Mar del Plata, a raíz de un seminario que hice en la escuela de artes visuales; se llamaba “Usos y valor simbólico del espacio”, con la profesora de Historia del Arte Graciela Zuppa. Esto me nutrió mucho. Veíamos distintos tipos de espacios y sus significaciones a partir de algunas lecturas. Lo público, lo privado, la danza como el espacio en movimiento. Con esto vi algo que, desde lo teórico y lo conceptual, me orientó. Me sugirió líneas para explorar abordar/ acercarme a/ explorar la espacialidad.

Cuando me dieron la beca decidí tirarme a la pileta y venir a vivir a Buenos Aires. También, como sucedió en Mar del Plata, me tocó un momento de mezcla, digamos un momento experimental de la beca. La edición de ese año –la tercera– fue la que más se abrió a incluir otras disciplinas. La primera incluyó solo pintura, la segunda no recuerdo, pero en la tercera se presentó gente de la moda, del video, de la fotografía, etc. Ellos tenían una actitud expansiva, se hablaba mucho de la bienal de arte joven. Una movida en la que se cruzaron lenguajes, disciplinas. Aprendí de esta idea de expandir la mirada, en vez de enfocarla.

Llegué y de pronto estaba en un lugar de mucha visibilidad. Entonces empecé a circular, aparecieron los galeristas, los coleccionistas, y empecé a comprender algo del circuito del arte, lo que se podría llamar “la escena”. Ese momento podría pensarse como una especie de profesionalización, pero eso no fue para mí lo importante. No pensaba en esos términos. Compartía la experiencia con otros artistas, veía el proceso de todos, los veía en acción. Gente que estaba en la escena, ellos eran personalidades en Buenos Aires. Me interesaba, más que su desarrollo artístico, sus modos de vida. De ellos aprendí algo más relevante que el funcionamiento de la escena. Lo que aprendí fue una especie de vitalidad, una vitalidad integradora.

¿Dónde?

Mis paseos y recorridos por la ciudad son una cita a ciegas con los materiales. No pienso en los posibles encuentros como recolección de materiales interesantes, de objetos y reciclaje, de basura útil. Veo vidrieras, interiores, modos de exhibición de las cosas y las cosas exhibidas. Eso me genera imágenes. Pero no se trata de cosas que podrían ser trasladadas a una fotografía, a un registro. Nunca pensé en tomar el modelo de un escaparate de librería, ni en hacer una góndola de supermercado. Si bien trabajé mucho con eso, y hasta podría decir que en gran medida lo que hago es una síntesis de distintos escaparates de distintas generaciones de librerías, no es tan específico el encuentro. Tengo que andar, casi paseando, sin prestar atención, pero encontrando. Como si confiase en que ese andar va a generar en mí un momento, un estado, que provoque una imagen, una síntesis. ¿Puedo decirlo? Una visión. Sí. No es lo que se va a buscar. Es lo que ocurre cuando uno salió a buscar nada y vuelve con todo.

Para mí el taller es un lugar de intimidad. Tuve muchos talleres, a veces fueron casa-taller, a veces talleres compartidos con otros artistas y a veces talleres para mí solo, pero siempre está la idea de llegar y entrar en una especie de clima o de trance, para llamarlo de algún modo. Más que querer concentrarme, es abstraerme. Empezar a generar situaciones para que pueda entrar en esta acción media de reubicar las cosas. Moverme, caminar alrededor de la mesa, presentar, plantear ubicaciones. Eso es para el trabajo más general. Después hay veces que decís: “Tal obra tengo que hacerla así, empezar por acá, después por allá”. Pero el proceso va ocurriendo, ocurre. Como alguna vez dije: “Es más lo que no hago que lo que hago”.

En mi taller tengo todo tipo de cosas que voy juntando o que me regalan. Me dicen: “No sé por qué creo que esto te puede llegar a servir” y lo recibo. Algunas me gustan, otras no. Pero cuando elijo, elijo no porque me guste o no me guste. Tampoco por su función. La búsqueda primaria es más bien formal, tiene mucho que ver con el material y su forma. Las cosas que junto son aquellas en las que reconozco un interés ya sea por su forma, su material o color. Alguna vez me regalaron raíces de árboles que vendían unos artesanos en el norte como esculturas. Me pareció una cosa extrañísima. Un material que nunca hubiera elegido. Dije sí, bienvenido, esto va a generar un clima en mi modo de trabajo. No sabía si las iba a usar pero finalmente las usé en las mesas del año 2004 y fue muy productivo.

El espacio de exposición para mí no es un lugar vacío, está lleno de potencias, de energía, de aire. Cuando puedo trabajar ahí, en el lugar, ocurre algo que tiene que ver con cierta idea de Feng Shui, una idea de Feng Shui propio. Es algo energético que funciona desde la relación entre el lugar y las cosas, y de las cosas entre sí. Entro al lugar y trato de que las cosas se ubiquen y que empiecen a relacionarse. Ya sea por cuán cerca o lejos tienen que estar de una cosa o la otra para

¿Cómo?

Recuerdo la instalación del banco Supervielle, ese hueco, en medio del edificio. “¿Qué hago acá?, no tengo nada, tengo un hueco de aire”, me dije. Bueno, sin embargo, eso mismo me sirvió, empecé a pensar la idea del aire. Pensar en el aire me llevó al objeto parapente, a la forma, al diseño de esa forma, al uso de colores. Nunca pensé el edificio como un banco, como una estructura pesada, llena de pasillos y puertas. No trabajé con ninguna idea de contraste entre lo sólido de un banco y lo etéreo de la forma parapente, ni con el cimiento y el vuelo. Trabajé con el espacio, con el aire que había en el espacio. Y eso me dio la libertad para llegar a la obra. Dejar de lado el lugar en el que estaba para concentrarme en el aire.

191 que estén conectadas, pero que cada una pueda verse por sí sola. Y sobre todo me interesa esta idea de ir activando zonas. Esa esquina, este lugar que es más bajo, aquel otro que es más alto y ahí trabajo con ese bloque de aire que es el espacio y que tiene la forma propia de cada espacio.

A mi trabajo lo marcó siempre como un cierto orden, pero no sé si busco que esté todo ordenado. Me gusta más pensar el acto de reubicar en el sentido de dar una localización a los objetos, localizarlos. Es cierto que después se genera un sistema pero esa intención sistémica de orden no aparece de entrada. Me tomo el trabajo desde otro lado. No sigo un patrón o un sistema de reglas predeterminado. No lo tengo de antemano. El modo en que voy ubicando las cosas tiene mucho más que ver con algo intuitivo y aleatorio. Pero esa reubicación está guiada por una economía de recursos, de formas. Hay un sentido de la economía en esa reubicación.

Coleccionar cosas. Juntar cosas y guardarlas en cajas. Por ejemplo, cosas de oficina, de librería. En su momento me gustaron mucho los Post It y las gomas de borrar. Después se fue ampliando el rubro, una cosa podía ser cualquier otra cosa. Después acumular. Acumular y empezar a coleccionarlas, sin orden ninguno, guardadas en cajas. La clasificación siempre formó parte del mover y reubicar. Al principio, empecé a trabajar sobre la pared. Ponía los objetos sobre la pared como murales. Se llamaba mural de formas y colores sobre la pared. En vez de cuadro, trabajaba con la idea de un mural. Empecé a observar la mesa, siempre trabajé sobre una mesa. Ahí tiraba todas mis cosas para poder separarlas y verlas. Un día dejé todo en la mesa y me fui. Al día siguiente, cuando volví, abrí la puerta y me encontré con los objetos así y pensé “pero esto es una instancia más de exhibición de los materiales”. Entonces tomé la mesa como soporte y como objeto.

Fui buscando y generando ciertos modos para que las cosas se vayan mostrando y mostrándose entre sí, pasando los objetos de la mesa a la pared o de la mesa a colgarlos. Empecé a ver y a

¿Por qué?

pensar qué pasaría si en vez de colgar, las cosas empiezan a levantarse y a construirse de abajo hacia arriba. ¿Qué sucede si combino estos procedimientos? Ahí todo tomó un carácter más escultórico. Fue un proceso que hoy podría resumir en un punto de partida muy sencillo: una mesa que puede ser dos caballetes y una tabla, y muchas cajas con objetos.

Gran parte de mi trabajo es, de alguna manera, performático. Voy moviendo cosas sin niguna idea de ordenar y me voy moviendo. En ese mover y moverme va ocurriendo algo entre esas cosas. No es que yo no esté presente, no. Es como si algo de uno quisiera correrse a un costado. Muevo cosas no para hacer algo específico, sino como si tratase de distraerme.

Una vez me dijeron algo muy bueno sobre mi trabajo: “Pareciera que el trabajo está conformado a partir de un modo, como un sistema que usa el arte moderno pero que no tiene detrás el sistema de crítica hacia algún tipo de discurso”. Y es cierto. En mi trabajo no hay discurso. No hay especulación. Y no hay intención crítica tampoco. No tengo un discurso sobre mi obra. Tampoco siento la presencia de la historia del arte cuando trabajo.

Yo creo que soy un curador de objetos más que un artista creador de objetos nuevos. Hice muchas instalaciones en mesas y para mí el espacio es como una gran mesa también. Las cosas que exhibo son importantes, pero también es significativa la distancia que hay entre esos objetos. Es más, a veces pienso que es más relevante eso que las cosas en sí.

Más que en un sentido de lo que hago, trato de pensar en el sentido de los momentos que voy atravesando. En cómo me fui formando, aprendiendo, poniéndome en diálogo con otros artistas, descubriendo el espacio de taller, cómo funcionaba yo ahí, caminando, reordenando, casi performáticamente. Fui pasando por distintos estados, distintos rulos de una misma cuestión, así lo siento. Y ahora estoy buscando otra vuelta más, como si hubiese llegado a un momento en que tengo que encontrarle un sentido nuevo, un estado nuevo.

Me siento un poco fuera del arte contemporáneo. Y no es que quiera sentirme adentro. Pero me parece que lo que llamamos arte contemporáneo tiene mucho que ver con lo discursivo. Prevalece la denuncia de algo. Muchas veces lo veo como ilustrativo. Ilustraciones de un tema. Como si siempre la obra tuviese que hablar sobre algo específico y concreto. Más justo, como si la obra siempre tuviese que hablar, decir algo.

Me interesa la palabra, la lectura, pero no en un sentido literal. Como ya dije, no me agarro de la historia o de un discurso de la historia del arte. Tampoco me agarro de teorías filosóficas. Me gustan los climas y las imágenes que presentan algunos textos, a veces textos que parecen distantes a mi obra. Pienso

en los filósofos Martin Hollis, en Sir Francis Bacon, o en Rodolfo Kusch cuando habla del modo de ser y estar de los indígenas, o un libro que estoy leyendo ahora que me está gustando bastante, el de Boris Groys, Arte en flujo Me inspiran. Es como si de ahí pudiera aprender algo que no tiene que ver con el lenguaje, algo como un modo de respirar.

No tengo ninguna pretensión de provocar. Creo que casi siempre estoy tratando de llegar a algo, como un descanso, o un retiro. Algo como lo que te provoca a veces la poesía, que te lleva a unos lugares adonde ni siquiera existís.

Me parece que mi modo de hacer tiene que ver con una sensación. Hay algunas palabras que por ahí están un poco trilladas, pero bueno… una sensación de extrañamiento o una nueva sensación perceptiva, que te corre de lugar, te saca de lo rutinario, te ubica en otro momento perceptivo, sensorial. Muchas veces dije las palabras transformación, alteración de la percepción y todo eso. Y me parece que eso ya no me representa. Ahora me gusta pensar en que una obra es una invitación a un estado. Quisiera que uno, cualquiera, el que se relaciona de alguna manera con la obra o yo mismo al relacionarme, no se sienta anclado a nada. No sé si a nada, no es a nada. Tal vez, sí solo a lo que ahí está ocurriendo. Y que ahí se generase la posibilidad de un cambio de estado, un cambio de clima. Como si la obra fuese ese contacto, un corrimiento hacia otro aire, un lugar para descansar.

by Ruben Mira

Art was something I came across when I was looking for something to do with my life; I felt a certain thing at a certain time. I didn’t start young, it’s not like I wanted to be an artist when I was a kid, it happened after I’d tried other things. I studied chemistry at secondary school and then I spent a year and a half studying bio-chemistry. After that I moved on to philosophy, which I studied for another year and a half, then I quit, and only then did I go to art school. And you might say that’s where I ended up. I always tell people that I’m not an artist by vocation. In fact, I sometimes wonder if I really am an artist.

What might a vocation look like? What is a vocation? Is it something that comes naturally or something you find? I didn’t learn about the arts at home. My parents were ordinary people, businesspeople, workers. They didn’t send me to drawing classes, they didn’t take me to see exhibitions. So art was hardly an inevitable choice for me; I gradually came to realize that it was where I belonged.

At art school, Joseph Beuys had a major impact on me, as did Duchamp. Later on there were the artists I came into contact with when I moved to Buenos Aires: Román Vitali, Ruy Krygier, Mónica van Asperen, Marina de Caro, Dino Bruzzone, Alejandra Seeber, Jane Brodie and Sergio Avello. Avello was very important to me. He was from Mar del Plata like me but I met him here, in Buenos

When?

Aires. It was also where I discovered the minimalists. I liked Sol Le Witt, Donald Judd, and Robert Morris a lot. Then I started to see work by a few Brazilian artists. I loved Waltercio Caldas, Brígida Baltar and Mira Schendel. As I saw it, they were related to the minimalists but with added poetry and sensuality. Later on, I started to pay more attention to contemporary art, the post-minimalists and the neo-conceptualists: the artist Rivane Neuenschwander, for example. Today, I’m interested in Jason Dodge’s work with perception, light and objects.

Maybe, strictly speaking, I was never interested in studying art. I can say who certain painters and artists are and talk about their techniques and working methods but none of that seems very relevant. Neither do I feel a need to reference them directly. I find it more important to address the climate of the artwork and the working climate suggested by said artwork. Or maybe you can turn the issue on its head: study is a conscious education that leads to an intelligent approach and discourse. Climate, in contrast, is a space that one physically inhabits, a place where one can be in their own way, absorbing it on a sensual, emotional level.

In art I found a space that allowed me to consider a lot of issues, a space where I could be free. When I think about it now I realize that some of it might have come from my family; they brought an everyday aspect to my work, something homely. The ordered manner I have, the way I present things, lay them out, place them... all that comes from my mother. I learned from the way she kept the house tidy and organized things and activities. I didn’t see that before but now I realize the influence she had on my work. It’s a sense of relocation.

In 1987 I started going to the Escuela Martín Malharro de Artes Visuales in Mar del Plata. I took the degree in production and then the doctorate too. Then I graduated and stayed in Mar del Plata. That was an important moment. The other moment I consider important is 1997 when I was chosen to take part in the Kuitca Grant programme. The first stage was training, training at higher education level, but then came the second stage and I went to Buenos Aires and started to get involved in the circuit.

The visual arts school was a kind of experiment that worked out very well for me. During the time I spent there, a group of teachers set up a plan they called the ‘Pilot Plan’ in which they integrated the different workshops. During the first three years we took each class separately – with a painting teacher, a drawing teacher, an engraving teacher – but in the last few years they were completely integrated. Among other things, they helped you to make progress with the ideas you wanted to work on. I found that formative stage very encouraging.

My work, or artworks (I find it difficult to refer to them as ‘artworks’), in Buenos Aires started to appear in the late 90s. One might say that that was when I developed the most as an artist in professional terms. I don’t know how to describe it, I can’t see

Where?

myself as a professional artist because I don’t see myself as a part of that discourse. At the time, with the grant, I was able to anchor myself not so much to a specific movement, but to a space. Specifically from ’97 onwards. But what I did had nothing to do with the kind of art being produced in the 90s. I was on the Kuitca Grant programme with a load of artists who had close ties to the Centro Cultural Rojas group. But I can’t see any relation between that movement and my output.

In the 90s I came to Buenos Aires to see exhibitions; I remember the installations especially. I was working with space in Mar del Plata, inspired by a seminar I attended at the visual arts school. It was called ‘The Uses and Symbolic Value of Space’ and was given by Graciela Zuppa, the History of Art teacher. That was a great inspiration. We looked at different kinds of spaces and their meanings according to different readings. Public, private, dance as space in movement... I saw something there that attracted me from both theoretical and conceptual standpoints. It pointed me in the right direction, suggesting things I could explore/address/ work with in relation to spatiality.

When I got the grant I decided to take the plunge and come to live in Buenos Aires. Also, just like in Mar del Plata, I arrived there during a moment of flux, during an experimental period for the programme. That year’s edition – the third – was when it was most open to other disciplines. The first only included painting, I can’t remember whether that was true of the second, but the third had people from the worlds of fashion, video, photography, etc. They had an expansive attitude, there was a lot of talk about the Young Artists’ Biennial. It was a movement that mixed languages and disciplines. What I learned from that was to expand my gaze instead of focussing it.

When I got there I was suddenly thrust into a very visible place. So I started to circulate, the gallery owners and collectors began to appear and I started to learn something about the art circuit, what you might call ‘the scene’. That period might be seen as a kind of professionalization but that wasn’t very important to me. I didn’t think in those terms. I shared the experience with other artists, I saw their processes and watched them in action. They were people from the scene, they were already well-known figures in Buenos Aires. What interested me, rather than their artistic development, was their lifestyles. From them I learned something more relevant than how the scene worked. What I learned was related to living space, an integrated lifestyle.

My wanderings through the city are a kind of blind date with materials. I’m not thinking of potential finds, interesting materials I might be able to pick up or objects I might be able to recycle; useful junk. I see window displays, interiors, ways to exhibit things and the things that are exhibited. That generates images. But these aren’t things that one could just photograph, things to be documented. I never consider using a bookshop display style model, or a supermarket aisle. Although I have worked a lot with

that and you might say that to a great extent what I do is to bring together different displays from different generations of bookshops, I don’t work so specifically. I have to walk around, almost go on a stroll, trying not to pay attention, but finding things anyway. As though I were confident that the wandering is going to spark a moment within me, a state, and that in turn will create an image, a coming together. Can I say it? A vision. Yes. It’s not about looking for something, it’s what happens when you go out looking for nothing in particular and come back with everything.

To me, the studio is a private place. I’ve had a lot of studios, sometimes they were studio-houses, sometimes studios shared with other artists and sometimes just for me but there was always the idea of going there and finding a climate, a trance, if one wants to give it some kind of name. Rather than trying to concentrate, it’s more like wanting to lose myself. To begin to generate situations that will allow me to start the preliminary activity of relocating things. Moving around, walking around the table, presenting things, placing them in certain places. That’s the more general work. Then sometimes you say: ‘I have to do such and such a work like this, start here, and then move on.’ But the process is happening, it happens. It’s like I once said: ‘I get more done doing nothing than when I’m actually doing something.’

At my studio, I have all kinds of things that I’ve collected or that are given to me. People say things like: ‘I don’t know why but I think you might find this useful,’ and I take it. I like some of them, others not so much. But when I choose them, it’s not because I like them or not. Or what they’re used for. The initial question is formal, it’s to do with the material and the shape. The things I collect are the ones I know I’m interested in because of their shape, material or colour. I was once given tree roots some artisans in the north were selling as sculptures. I found them very strange. It was a material I would never have chosen. I said sure, great, it’ll create a climate in my working method. I didn’t know if I was going to use them but in the end I did for the tables in 2004 and they were very productive.

To me, an exhibition space isn’t empty; it’s full of potential, energy, air. When I am able to work in the space itself, I do something related to a certain idea of Feng Shui, my own kind of Feng Shui. It’s about energy, its relationship to the place and things and the things’ relationship with each other. When I enter the space I try to let the things find their place and start to relate with each other. I try to decide how far apart objects need to be so they can be connected but also be seen in their own right. Most of all I’m interested in the idea of creating zones. This corner, that place lower down, this one higher up... I work with the block of air that makes up the space, and its outline.

I remember the Banco Supervielle installation, that gap in the middle of the building. I asked myself: ‘What am I doing here? I don’t have anything, just thin air.’ But then that in itself helped me, I started to think about the idea of using air. Thinking about

My work has always featured a certain sense of order, but I’m not sure if I want everything to be neat and tidy. I’d prefer to think of it as an act of relocation in the sense of finding objects and then placing them somewhere. Of course, subsequently a system is generated but the systematic aspects of order aren’t there from the beginning. I approach the work from a different perspective. I don’t follow a pattern or a set of pre-determined rules. I don’t have it planned out beforehand. The way I place things is much more random and intuitive. But that relocation is guided by an economy of resources, of forms. There is a kind of economics in the relocation.

199 air led me to a gliding object, to a shape, to the design of that shape, the use of colour. I never thought of the building as a bank, a heavy structure full of doors and hallways. I never worked with the idea of the contrast between the solidity of a bank and the ethereality of the gliding shape, or with foundations and flight. I worked with the space... with the air in the space. And that gave me the freedom to arrive at the artwork. To put to one side the place where I was and concentrate on the air.

Collecting things. Gathering things and putting them in boxes. Like things from the office, stationary. At one time I loved Post It notes and erasers. Then the range of things I used expanded; one thing might be anything else. Then they would accumulate. They would accumulate and I would start to collect them, in no particular order, and put them in boxes. Classification was always a part of the movement and relocation. At first, I started to work on the wall. I put objects on the wall as murals. I called them a Mural of Shapes and Colours on the Wall. Instead of a painting, I worked with the idea of a mural. Then I started to notice the table, I always worked on a table. It was where I put my things to separate and look at them. One day, I put everything on the table and left. The next day, when I came back, I opened the door, found the objects like that and thought ‘but this is just another way to exhibit the materials’. So I started to use the table as both a medium and an object.

I was looking to create certain ways for things to show themselves to us and each other, moving them from the table to the wall, or hanging them up. I started to look and think about what might happen if, instead of hanging them, the things started to raise themselves up, to build upwards. What would happen if I combined those procedures? Then everything took on a more sculptural nature. As a process it can be summarized very simply: a table that might just be a pair of struts and a board, and a lot of boxes full of things.

In a way, a large part of my work is performance. I move things around with no idea how I’m going to organize them and move myself around as I do so. As I move things and myself, something happens among the things. It’s not that I’m not there anymore. It’s as though something of oneself has stepped aside. I move things not to do anything specific but as though I were trying to distract myself.

Someone once said something very good about my work: “It’s as though the work is made according to a certain method, like a system used by modern art but without the critical aspects or discourse.’ And it’s true. There isn’t any discourse in my work. There’s no speculation. There’s no attempt at criticism. I haven’t produced any discourse about my work. Neither do I feel the presence of the history of art when I work.

I think that I’m more of a curator of objects than an artist who creates new objects. I’ve done a lot of installations on tables and to me the space is like a big table too. The things I exhibit are important but the distance between those objects is important too. In fact, sometimes I think it’s more important than the objects themselves.

Rather than finding meaning in what I do, I try to think of the meaning contained within the moments I experience. In how I learned, was taught, established dialogues with other artists, discovered the studio space... how I worked, walking around, reorganizing, almost as a performance. I went through different states, through different takes on the same question... that’s how I see it. And now I’m looking for another twist, as though the moment has come when I need to find new meaning, a new state.

I feel a little outside of contemporary art. But it’s not as though I want to feel like an insider. I think that what we call contemporary art has a lot to do with the discourse. You need to be making a statement. I often see it as illustrative. Illustrations of a theme. As though an artwork has to say something about something in particular. Or to put it less harshly: as though an artwork always has to be speaking, to be saying something.

I’m interested in words, reading, but not in a literal sense. As I said, I don’t cling to history, or the discourses of the history of art. Neither do I have use for philosophical theory. I like climates and the images that come up in certain texts, sometimes texts that seem very different from my work. I’m thinking of the philosopher Martin Hollis, Sir Francis Bacon, and Rodolfo Kusch when he mentions the ways of being of indigenous peoples, or a book I’m currently reading that I’m enjoying quite a lot. Art in Flux by Boris Groys. They inspire me. It’s as though they can teach me something that has nothing to do with language, like a new way to breathe.

I have no intention of being provocative. I think that I’m almost always trying to achieve something, something like a rest, or a withdrawal. The kind of thing that poetry sometimes does to you, taking you to places where you don’t even exist.

I think that my working method has to do with a sensation. Some words might sound a little clichéd but... the sensation of estrangement, or a new perceptive sensation that pushes you to one side, shakes you out of your routine, places you

in another perceptual, sensory moment. I keep using the words transformation, altered perception and all that. And I think that describes me well. Now I like to think of an artwork as an invitation to enter a state of being. I’d like people, whoever, anyone who relates in some way with the artwork, or myself when I relate to me, to feel completely unbound. That’s not to say that nothing’s there, it’s not nothing. Maybe only what’s happening in that moment. And that is where a change of state, a change of climate, becomes possible. As though the artwork provided that contact, a shift into another kind of air; a place to rest.

2013

“El mundo siempre”, [The World Forever] Instalación [Installation] Vista general de la muestra [General view of the exhibition]p 14-15

2013 Donaldmejudme, Instalación [Installation]

Madera, cobre, bronce, cartulina, franelas y paños tipo ballerina [Wood, copper, bronze, card, cloths and dishcloths] 89 x 256 x 10 cmp 16-17

2013

Plano celeste - Grand Manan, [Light Blue Plane – Great Manan] Instalación [Installation] Fotografía, hojas de papel, cinta, cartulina y broches metálicos [Photography, sheets of paper, ribbon, card and metal clasps] 127 x 119 cmp 18

2013

Diez colores, [Ten Colours] Instalación [Installation] Cortina de bandas verticales [Curtain with vertical stripes] 390 x 278 cmp 19

2013

“El mundo siempre”, [The World Forever] Vista general de la muestra [General view of the exhibition]p 20-21

2013

Eclipse frente al escritorio, [Eclipse in Front of a Desk] Instalación [Installation]

Esferas de plástico, tanza y lámpara de pie

[Plastic spheres, plastic wire and foot lamp] 260 x 150 x 100 cmp 22

2013

Pequeño Damian Hirst, [Little Damian Hirst] Botones cosidos sobre tela [Buttons sewn into fabric] 102 x 75 cmp 23

2013

Clásica, [Classic] Instalación [Installation] Jarra de bronce, anilla de escalada y mosquetón de acero [Bronze jug, climbing rings and steel karabiner] Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 25

2014

“Móvil”, [Mobile] Instalación [Installation] Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 26-27

2014

“Móvil”, [Mobile] Instalación [Installation] Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 29

2014

“Móvil”, [Mobile] Instalación [Installation] Detalles [Details]p 30-31

2004

Luna - De la instalación “Hormigas, arañas y abejas”, [Moon – from the installation Ants, Spiders and Bees] Detalle [Detail]p 34-35

2004

“Hormigas, arañas y abejas”, [Ants, Spiders and Bees]

Vista general de la instalación [General view of the installation] Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 37

2004

Obrera - De la serie “Hormigas, arañas y abejas”, [Worker – from the series Ants, Spiders and Bees]

Detalle [Detail]p 38

2004

Obrera - De la serie “Hormigas, arañas y abejas”, [Worker – from the series Ants, Spiders and Bees]

Tablero revestido en cuerina sobre caballetes; pieza torneada en madera con tapa de Coca-Cola; 14 reglas escolares de madera; 10 cajas de cartón forradas en papel dorado; 8 fajos de palitos de helado; columna de papeles de escritorio, artefacto lumínico [Leatherette covered trestle table: piece screwed into wood with Coca-Cola cap: 14 wooden rulers: 10 cardboard boxes lined with golden paper; 8 bundles of ice cream sticks; column of paper; light artefact] 120 x 180 x 80 cm

Colección Malba - Fundación Costantini, Buenos Aires

Adquisición gracias al aporte de Malba - Fundación

Costantini, 2004

[Malba – Costantini Foundation Collection, Buenos Aires

Acquisition thanks to the contribution of Malba – Costantini Foundation]

p 39

2004

Reina - De la serie

“Hormigas, arañas y abejas”

[Queen – from the series Ants, Spiders and Bees]

Detalle [Detail]

p 41

2004

“Hormigas, arañas y abejas”, [Ants, Spiders and Bees]

Detalle [Detail]

p 42

2004

Reina - De la serie “Hormigas, arañas y abejas”, [Queen – from the series Ants, Spiders and Bees]

Tablero revestido en cuerina sobre caballetes; resma de papel negro con objetos de vainas plásticas; 3 piezas torneadas en madera; fajo de tarjetas envuelto en papel; atado de hilo de caña; vaso de vidrio con pieza de madera e hilo; capullo de plástico

[Leatherette covered trestle table; ream of black paper with objects in plastic pods; 3 pieces screwed into the wood; pack of cards wrapped in paper; ball of cane string; glass with piece of wood and thread; plastic hood] 120 x 180 x 210 cm

Colección Malba - Fundación Costantini, Buenos Aires Donación: Adquisición gracias al aporte de Gabriel Werthein y de Fundación Eduardo F. Costantini, 2006

[Malba – Costantini Foundation Collection, Buenos Aires [Acquisition thanks to the contribution of Gabriel Werthein and the Eduardo F. Costantini Foundation, 2006]p 43

2004

“Hormigas, arañas y abejas”, [Ants, Spiders and Bees] Detalle de la instalación [Detail of the installation]p 45

2005

“Sonidos distantes”, [Distant Sounds]

Detalle

[Detail]

Tablero de madera sobre caballetes, cartulinas escolares, libro, flauta, semilla de nogal, rodaja de alcornoque [Trestle table, school cards, book, flute, walnut, slice of cork] 90 x 180 x 80 cm

Colección Mauro Herlitzka, Buenos Airesp 46-47

2005

“Sonidos distantes”, [Distant Sounds]

Mesa de madera restaurada, cartulina, resmas de papel, tinteros con tinta china

[Restored wooden table, card, reams of paper, India ink well]

60 x 80 x 80 cm

Colección Gabriel Werthein, Buenos Airesp 48

2001

Evidencia geológica, [Geological Evidence]

Mesa, cubos de madera, planchas de hardboard, escuadras escolares y rodaja de árbol

[Table, wooden cubes, hardboard sheets, school set squares and slice of tree]

160 x 90 x 80 cm

Colección Museo de Arte Moderno, Buenos Airesp 49

2001

El sial flota sobre el simaDe la serie “Geografía”,

[The Sial Floats on the Sima – from the Geography series]

Tablero de madera sobre caballetes, resmas de papel, cartulinas y barra de madera

[Trestle table, reams of paper, card and wooden bar]

120 x 180 x 80 cmp 51

2001

Domo - De la serie “Geografía”, [Dome – from the Geography series]

Resma de papel y lápices

[Reams of paper and pencils]

21 x 29,7 x 10 cm

Colección MACRO, Rosariop 54-55

2001

Domos - De la serie “Geografía”, [Domes – from the Geography series]

Resmas de papel, tacos de madera, colección de revistas y bases de madera

[Reams of paper, wooden plugs, collection of magazines and wooden bases]

Medidas variables

[Varying measurements]

Colección MACRO, Rosario

Sobre la pared

Sin título - De la serie “Geografía”, [Untitled – from the Geography series]

Mural de varillas de madera e hilo de coser

[Mural of wooden bars and thread]

Medidas variables [Varying measurements]

Colección MACRO, Rosariop 57

2001

Relieve - De la serie “Geografía”, [Relief – from the Geography series]

Tarjetas de cartón apiladas [Pile of cards] 10,5 x 7,5 x 90 cmp 59

2001

Sin título - De la serie “Geografía”, [Untitled – from the Geography series]

Escuadras escolares de madera [Wooden set squares] 60 x 40 cm

Colección Lucio Dorr, Buenos Airesp 60-61

2009

La distancia entre las cosasDe la serie “Período azul”, [The Distance Between Things – From the Blue Period series]

Lana, varillas de madera e imanes [Wool, wooden rods and magnets] Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 63

2009

La distancia entre las cosas - De la serie “Período azul”, [The Distance Between Things –from the Blue Period series] Lana, varillas de madera e imanes

[Wool, wooden bars and magnets] Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 64-67

2007

Domingo, [Sunday]

Detalle del kiosco [Detail of kiosk]

Instalación [Installation] Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 68-72

2007

Domingo, [Sunday] Instalación [Installation]

Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 73-74

2007

Domingo, [Sunday]

Detalle del kiosco [Detail of kiosk] Instalación [Installation]p 75

2009 “Período azul”, [Blue Period] Vista general de la instalación [General view of the installation]p 76-77

2009

Pelota paleta, [Ball Paddle]

Detalle [Detail]

Cartulina y paspartú [Card and passe-partout] 63,5 x 44,5 cmp 78

2009

Set de viaje, [Travel Kit]

Madera, cartulina, bloc anotador con forma de mano, brújula, biblia y pajarito de cristal [Wood, card, hand-shaped block of notes, compass, bible and crystal bird] 60 x 30 cmp 79

2009

Pronóstico reservado 1, [Uncertain Forecast 1]

Dibujo [Drawing]

31,5 x 40 cmp 80

2009

Pronóstico reservado 2, [Uncertain Forecast 2]

Dibujo [Drawing]

22,5 x 32 cmp 81

2009

Pelota paleta, [Paddle Ball]

Detalle [Detail]

Cartulina y paspartú [Card and passe-partout] 21,5 x 75 cmp 82

2009

Escandinava, [Scandinavia]

Aros de madera, cartulina, precintos plásticos y lámpara [Wooden rings, card, plastic strips and lamp]

150 x 90 x 80 cm

Colección Ignacio Liprandi, Buenos Airesp 83

2015

Sin título - De la serie “Buscando un tiempo y una forma”, [Untitled – From the series Looking for a Time and a Shape]

Ciclo Bellos Jueves

Detalle de la instalación [Detail from the installation] Biombos de madera [Wooden screens] Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 84-85

2015

Sin título - De la serie “Buscando un tiempo y una forma”, [Untitled – From the series Looking for a Time and a Shape]

Ciclo Bellos Jueves Instalación

[Installation]

Vista general de la instalación [General view of the installation]

Biombos de madera [Wooden screens]p 86-87

2015

Sin título - De la serie “Buscando un tiempo y una forma”, [Untitled – From the series Looking for a Time and a Shape]

Ciclo Bellos Jueves

Detalle de la instalación

[Detail from the installation]

Biombos de madera [Wooden screens]p 89

2015

Sin título - De la serie “Buscando un tiempo y una forma”, [Untitled – From the series Looking for a Time and a Shape]

Ciclo Bellos Jueves

Detalle de la instalación

[Detail from the installation]p 90

2015

Sin título - De la serie “Buscando un tiempo y una forma”, [Untitled – From the series Looking for a Time and a Shape]

Ciclo Bellos Jueves

Detalle de la instalación

[Detail from the installation]p 91

2015

Sin título - De la serie

“Buscando un tiempo y una forma”, [Untitled – From the series Looking for a Time and a Shape]

Ciclo Bellos Jueves

Detalle de la instalación

[Detail from the Installation] Recorrido con cartulinas en los pasillos del Museo Nacional Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires

[Card tour in the halls of the Museo Nacional Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires]p 92-93

2015

Sin título - De la serie “Buscando un tiempo y una forma”, [Untitled – From the series Looking for a Time and a Shape]

Ciclo Bellos Jueves Instalación [Installation]p 94-95

2015

Sin título - De la serie

“Buscando un tiempo y una forma”, [Untitled – From the series Looking for a Time and a Shape]

Ciclo Bellos Jueves Instalación [Installation]p 97

2010

La carrera del aire, [The Air Race] Instalación [Installation]

Barriletes en tela rip stop, varillas de aluminio, cable y mosquetones de acero

[Kites made from rip stop fabric, aluminium rods, cable and steel snap rings]

Medidas variables [Varying measurements] Colección Banco Superviellep 98-99

2010

La carrera del aire, [The Air Race] Detalle [Detail]p 100-102

2010

La carrera del aire, [The Air Race]

Vista general de la instalación [General View of the Installation]p 103-105

2010

La carrera del aire, [The Air Race]

Vista general de la instalación [General View of the Installation]p 107

2006

The Invisible Jump, Aros, varillas y esferas de madera, metal y plástico [Rings, rods and spheres made from wood, metal and plastic] Instalación [Installation]

Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 109-115

2015

La línea, un lugar y un momento determinados [A Certain Line, Place and Moment]

Ciclo Situaciones Breves, Instalación, acciones, poesía y ritual [Installation, actions, poetry and ritual]p 116-117

2014

“Desplazamientos”, [Displacements]

Vista general de la instalación [General view of the installation]p 118-119

2014

“Desplazamientos”, [Displacements] Instalación [Installation] Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 120-121

2014

“Desplazamientos”, [Displacements] Instalación [Installation]

Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 122-123

2014

“Desplazamientos”, [Displacements]

Detalle de la instalación [Detail from the installation]

p 124-127

2014

Escala de grises, [Grey Scale]

Cajas de papel de fotocopiadora [Boxes of photocopy paper] 10 x 6 x 6 cm cada caja [each box]p 128-135

2014

Eclipse, Trípodes, lámpara reflectora, difusor, madera y cartulina [Tripods, spot light, screen, wood and card]

Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 136-137

2014

Eclipse - De la serie

“Desplazamientos”, [Eclipse – from the Displacements series]

Detalle de la instalación [Detail from the installation]p 138

2014

Proyecto inútil #2 - De la serie “Desplazamientos”, [Useless project #2 – From the Displacements series]

Aros de papel, tanza y base de madera

[Paper and ribbon rings and wooden base] 90 x 45 x 40 cmp 139

2017

“Si dijiste algo, no se oyó”, [If you said something, it wasn’t heard]

Vista general de la instalación

[General view of the installation]

p 140-141

2017

“Si dijiste algo, no se oyó”, [If you said something, it wasn’t heard]

Detalle

Detailp 143-145

2017

Columna, [Column]

Papel encolado [Glued paper]

112 x 7,5 x 10,5 cmp 147

2017

Placas - De la serie

“Si dijiste algo, no se oyó”, [Boards – From the series If you said something, it wasn’t heard]

Calcos en yeso

[Plaster casts]p 148-149

2017

Placas - De la serie

“Si dijiste algo, no se oyó”

[Boards – From the series

If you said something, it wasn’t heard]

Calcos en yeso

[Plaster casts]p 150-151

2017

Placa - De la serie

“Si dijiste algo, no se oyó”, [Boards – From the series

If you said something, it wasn’t heard]

Calcos en yeso

[Plaster casts]

42,5 x 28,5 cm

p 152

2017

Placa - De la serie

“Si dijiste algo, no se oyó”

[Boards – From the series

If you said something, it wasn’t heard]

Calcos en yeso

[Plaster casts]

18 x 28 cmp 153

208

2017

Placa - De la serie “Si dijiste algo, no se oyó”, [Boards – From the series If you said something, it wasn’t heard]

Calcos en yeso [Plaster casts] 18 x 25 cmp 154

2017

Placa B - De la serie

“Si dijiste algo, no se oyó”, [Boards B – From the series If you said something, it wasn’t heard]

Calcos en yeso [Plaster casts] 27,5 x 43,5 cmp 155

2017

“Móvil”, [Mobile]

Detalle [Detail]p 156

2017

“Móvil”, [Mobile]

Detalle [Detail]

Aros y varillas de madera y metal pintados

[Painted metal and wood rings and rods] Medidas variables [Varying measurements]p 157

2017

Bubble, Aros de madera pintados, varilla de metal y precintos plásticos

[Painted wooden rings, metal rod and plastic strips] 100 x 186 cmp 159

2017

A0, Madera laminada [Laminated wood] 84,1 x 118,9 cmp 160

2017

Display, Escultura [Sculpture] Paneles de madera [Wooden panels]

220 x 160 x 160 cmp 161

2017

Verde, rojo, azul, [Green, red, blue] 75 x 58 cmp 162

2017

Rojo, negro, azul, [Red, black, blue] 58 x 75 cmp 163

2017

“Si dijiste algo, no se oyó”, [If you said something, it wasn’t heard] Detalle de la instalación [Detail from the installation]p 164-165

2017

“Si dijiste algo, no se oyó”, [If you said something, it wasn’t heard] Detalle de la instalación

[Detail from the installation]p 167

1998

Muchas felicidades, [Many congratulations] Objeto [Object] 12,5 x 11 x 8 cmp 169

1998

S-T, [U-T]

Banda y cinta de papel [Paper strip and streamer] 15 x 11,5 cm

p 171

2010

Instrucciones - De la serie “Un regalo para Sol LeWitt” [Instructions – From the series A Gift for Sol LeWitt] Collage fotográfico [Photographic collage] 21 x 29,7 cmp 173

2013

Boomerang - De la serie “El mundo siempre”, [Boomerange – From the series The World Forever] Objeto [Object] 30 x 38 cmp 174-175

2016

Formatos de referencia, [Reference Formats] Papel plegado [Folded paper] 138 x 102 x 6 cm

p 177

2011

Muestrario, [Sampler] Collage 32 x 25 cmp 179

2006 Red, [Net]

Rosarios luminosos y tanza [Lighted rosaries and ribbon] Instalación [Installation] Medidas variables [Varying measurements] Colección David Gorodisch, Buenos Airesp 181-185

Daniel Joglar

Nace en Mar del Plata, provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina, en 1966. Egresa como profesor y realizador de la Escuela de Artes Visuales Martín Malharro (1989-1993) en su ciudad natal y forma parte del Programa de Becas de Guillermo Kuitca (1997-1999) en Buenos Aires. Dentro de sus exposiciones individuales más destacadas se encuentran las desarrolladas en: Ruth Benzacar (2013-2017), Dabbah Torrejon (20012005-2009), Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas en Austin (2006) y en Artists’ Space en Nueva York (2006). A lo largo de su carrera, obtiene, en Argentina, becas de la Fundación Antorchas (2002 ) y del Fondo Nacional de las Artes (2002 y 2009), y los premios Elena Poggi (2004) y el de la Bienal Regional de Bahía Blanca (1998). Asimismo, participa de las residencias CentralTrak de la Universidad de Texas en Dallas (2009), Art Omi International Artists Residency en Nueva York (2007), y la Residencia Internacional de Artistas en Ostende, Argentina (2007). Sus obras se encuentran en las colecciones de importantes museos de su país, como el Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA), Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires (MAMBA), Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Rosario (MACRO), Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Bahía Blanca (MACBA) y Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes Franklin Rawson en San Juan. También integran grandes colecciones de arte como la Zabludowicz Collection en Londres y la Colección Banco Supervielle en Buenos Aires. Su trabajo ha sido incluido en los compendios Vitamin 3D (Londres, Phaidon Press, 2009) y 50 International Emerging Artists (Contemporary magazine, Londres, 2006). En la actualidad reside y trabaja en Buenos Aires.

211

Daniel Joglar

Was born in Mar del Plata, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, in 1966. After graduating as a teacher and artist from the Escuela de Artes Visuales Martín Malharro (1989-1993) in his home city, he joined the Guillermo Kuitca Grant Programme (19971999) in the City of Buenos Aires. Notable solo exhibitions by the artist include those held at the Ruth Benzacar Gallery (2013-2017), the Dabbah Torrejon Gallery (2001-2005-2009), the Blanton Museum of Art, the University of Texas in Austin (2006) and the Artists’ Space in New York (2006). He has received grants from the Fundación Antorchas (2002) and the Fondo Nacional de las Artes (2002 and 2009), the Elena Poggi Prize (2004) and the Bahía Blanca Regional Biennial Prize (1998). He has also taken part in the CentralTrak Residency at the University of Texas in Dallas (2009), the Art Omi International Artists Residency in New York (2007), and the International Artist’s Residency in Ostende, Argentina (2007). His artworks are featured in the collections of the leading museums in the country including the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA), the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires (MAMBA), the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Rosario (MACRO), the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Bahía Blanca (MACBA) and the Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes Franklin Rawson in San Juan. His work is also a part of major private art collections such as the Zabludowicz Collection in London and the Banco Supervielle Collection in Buenos Aires. He has been featured in the compendiums Vitamin 3D (Phaidon Press, London, 2009) and 50 International Emerging Artists (Contemporary magazine, London, 2006). He currently lives and works in Buenos Aires.

213

ISBN 9789874292971

IDEA Y COORDINACIÓN

/ORIGINAL IDEA

AND COORDINATION

Ailin Staicos & Ruben Mira

FANTASY Comunicación

ENTREVISTA

/INTERVIEW

Ruben Mira

DISEÑO EDITORIAL

/GRAPHIC DESIGN

María Sibolich

TRADUCCIÓN

/TRANSLATION

Kit Maude

CORRECCIÓN DE TEXTOS

/TEXT EDITOR

Studio Glosa

FOTOGRAFÍA

/PHOTOGRAPHY

Gabriela Valle

Gustavo Barugel

Gustavo Lowry

Ignacio Iasparra

Jimena Lascano

Nicolás Gullotta

Rodrigo Mendoza

CESIÓN DE IMÁGENES

/IMAGE PERMISSIONS

Fundación Osde

Malba

Blanton Museum of Art

RETOQUE FOTOGRÁFICO

/DIGITAL PHOTO EDITOR

Paula Rubinstein

- Muchas gracias a Orly Benzacar, Mora Bacal y a Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte por el apoyo incondicional a mi proceso artístico.

- A Ruben Mira por la entrevista y consejos sobre el rumbo del libro.

- A Ailin Staicos por llevarlo adelante y a su equipo por trabajar tan arduamente.

- Muchas gracias a los curadores y artistas que confiaron en mi trabajo y me convocaron a realizar tantos proyectos: Sonia Becce, Andrés Duprat, Victoria Noorthoorn, Inés Katzsenstein, Guillermo Kuitca, Gabriel Pérez Barreiro, Omar López Chahoud, Fernando Farina, Florencia Battiti, Mariana Rodríguez Iglesias, Karina Granieri, Rodrigo Alonso, Ana María Quijano, Santiago Bengolea, Ana María Batistozi, Julio Sánchez, María Teresa Costantin, Guillermo Faivovich, Javier Villa, Gachi Hasper, Graciela Taquini, Gabriela Urtiaga, Nanci Rojas, Mariano Mayer, Ana Gallardo, Olga Correa, Fernanda Laguna, Federico Baeza, Lara Marmor, Sebastián Vidal Mackinson, Javier Aparicio, Santiago Villanueva, Alejandro Tantanian, Ariadna González Naya, Leandro Comba, Danielle Perret, Verónica Flom, Valeria González, Regine Basha, Philippe Cyroulnik, Gerardo Mosquera, Alina Tortosa, Patricia Rizzo, Leopoldo Estol y Daniel Besoytaorube.

- A mis profesores Nélida Valdéz, Oscar Elissamburu, Lucila Soldavini, Graciela y Silvia Zuppa.

- Muchas gracias también Ana Torrejón, Horacio Dabbah, Adriana Rosenberg, Emmanuelle y Patricio Supervielle y a todos los coleccionistas que me apoyaron en el transcurso de estos años.

- Gracias a Balanz que hizo posible la impresión de este libro.

Acknowledgements

- Many thanks to Orly Benzacar, Mora Bacal and Ruth Benzacar Galería de Arte for their unconditional support of my artistic process.

- To Ruben Mira for the interview and his guidance during the book-making process.

- To Ailin Staicos for making it happen, and her team for all their hard work.

- Many thanks to the curators and artists who trusted in my work and invited me to make so many projects: Sonia Becce, Andrés Duprat, Victoria Noorthoorn, Inés Katzsenstein, Guillermo Kuitca, Gabriel Pérez Barreiro, Omar López Chahoud, Fernando Farina, Florencia Battiti, Mariana Rodríguez Iglesias, Karina Granieri, Rodrigo Alonso, Ana María Quijano, Santiago Bengolea, Ana María Batistozi, Julio Sánchez, María Teresa Costantin, Guillermo Faivovich, Javier Villa, Gachi Hasper, Graciela Taquini, Gabriela Urtiaga, Nanci Rojas, Mariano Mayer, Ana Gallardo, Olga Correa, Fernanda Laguna, Federico Baeza, Lara Marmor, Sebastián Vidal Mackinson, Javier Aparicio, Santiago Villanueva, Alejandro Tantanian, Ariadna González Naya, Leandro Comba, Danielle Perret, Verónica Flom, Valeria González, Regine Basha, Philippe Cyroulnik, Gerardo Mosquera, Alina Tortosa, Patricia Rizzo, Leopoldo Estol and Daniel Besoytaorube.

- To my professors Nélida Valdéz, Oscar Elissamburu, Lucila Soldavini, Graciela and Silvia Zuppa.

- Thank you also to Ana Torrejón, Horacio Dabbah, Adriana Rosenberg, Emmanuelle and Patricio Supervielle and all the collectors who have supported me over the years.

- Very thanks to Balanz that made the printing of this book possible.