Impact & Innovation

Advancing transformative mental health care for veterans, active-duty service members and their families

The Road Home Program: The National Center of Excellence for Veterans and Their Families at Rush

Advancing transformative mental health care for veterans, active-duty service members and their families

The Road Home Program: The National Center of Excellence for Veterans and Their Families at Rush

1,597 veterans, active-duty service members and family members treated at the Road Home Program in fiscal year 2025 (a 15.4% increase from the previous year)

14,154 hours of clinical care delivered to clients in fiscal year 2025 (a 10.6% increase from the previous year) regardless of discharge status and at no out-of-pocket cost to them

75% of clients who complete the accelerated brain health program experience clinically significant reductions in post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in just two weeks of treatment; 84% of clients report feeling better after treatment

79% of clients served are post-9/11 veterans

89% of accelerated brain health program participants travel from outside Illinois, and the costs of their travel, lodging and meals are covered

100+ postdoctoral fellows, counseling and social work interns, psychology externs, medical residents and students, and research assistants trained in veterans’ mental health care at the Road Home Program since 2016

50+ articles published in leading peer-reviewed scientific journals to date by Road Home Program experts and 100+ presentations given to date at national and international conferences

The lessons learned here, at the Road Home Program: The National Center of Excellence for Veterans and Their Families at Rush, are contributing to advancements in care everywhere

Your support of our mission to compassionately care for veterans, service members and their loved ones is renewing hope in people’s lives. Because of you, we can provide evidence-based, culturally competent care at no out-of-pocket cost to those we serve. Simultaneously, we can invest in the research that drives improvements in the care we provide. No two clients are the same, and to ensure we provide the best possible care for all, we are pursuing and fine-tuning the most effective, tailored treatments for each client’s circumstances.

All the while, we train the next generation of mental health providers on our leading-edge models of care, creating a ripple effect that will touch the lives of everyone these trainees will go on to serve.

Your philanthropy fuels the impact and innovation that pour from our program and into people’s lives — easing the transition home, strengthening family connections and helping veterans rediscover purpose after their service. Thank you for your belief in our mission and investment in the essential work we do.

In the following pages, you’ll learn more about how your support is advancing our research and care, hear from clients who have benefited from our program and discover how we’re sharing our knowledge with the mental health field, including burgeoning practitioners.

We hope these stories make you proud to be a member of our donor community. Together, we are advancing evidence-based mental health care for all who have experienced trauma.

Sincerely,

Thomas E. Lanctot Co-Chairperson, Road Home Program Advisory Council

William A. Mynatt Jr. Co-Chairperson, Road Home Program Advisory Council

Road Home researchers pioneer a multi-agent AI tool to supplement traditional therapy

What assumptions have you made about artificial intelligence? Are there alternative viewpoints?

The above are examples of Socratic questioning, a key component of cognitive behavioral therapies, like cognitive processing therapy, which uses open-ended questions to encourage reflection. At the Road Home Program, where these therapies are used, researchers have developed an AI tool called Socrates 2.0 that uses Socratic questioning to ethically enhance and supplement traditional mental health care delivery.

Over the past decade, AI has rapidly progressed from a science fiction trope to a tool deeply embedded in many aspects of everyday life. The advent and progression of large language model chatbots like ChatGPT

(where GPT stands for generative pre-trained transformer) had a domino effect for AI tools across a multitude of specialties, including mental health care.

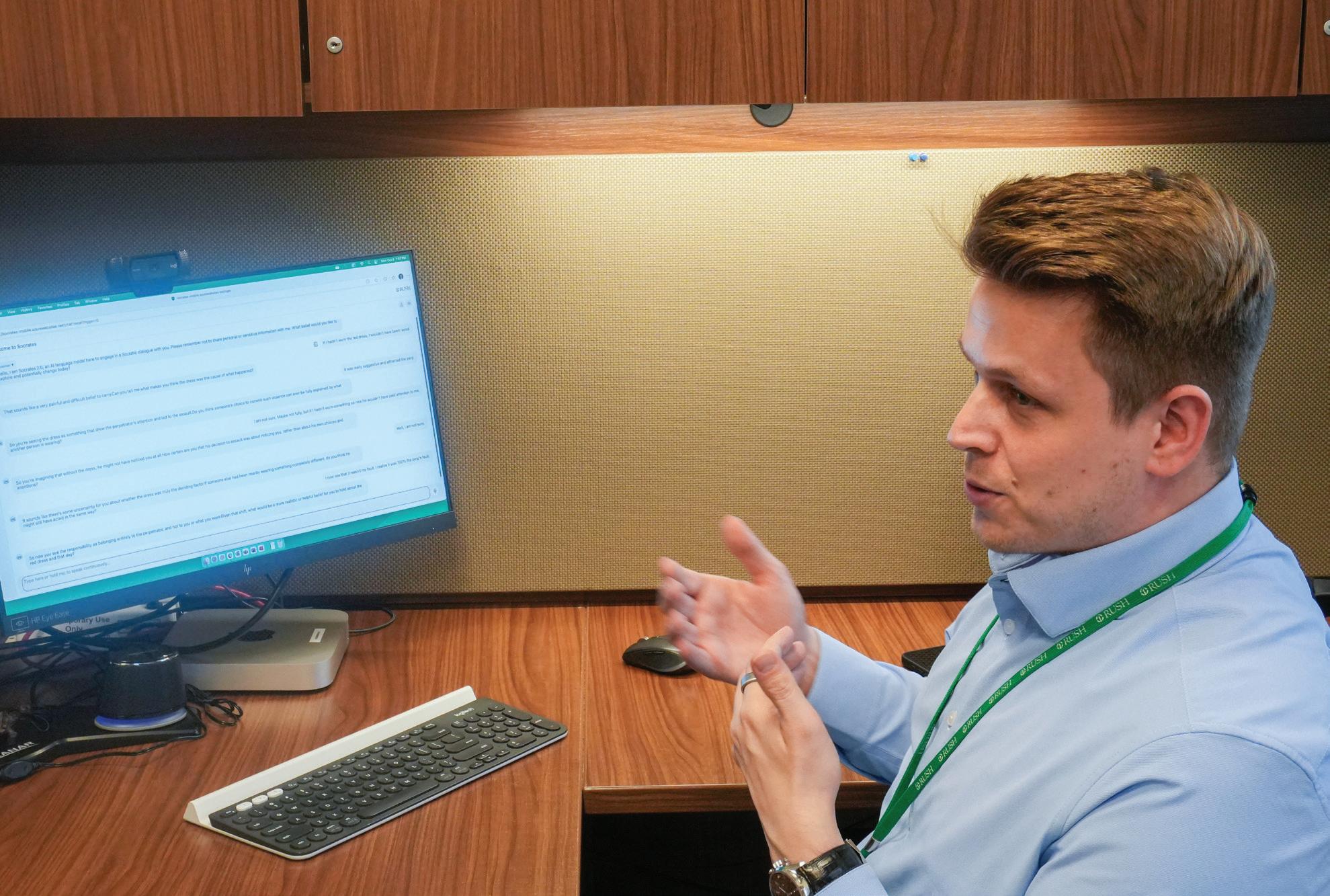

“There are many therapy apps and chatbots out there, but very few of those have been tested,” said Philip Held, PhD, Road Home’s research director.

In 2023, Road Home researchers set out to create something different — a tested tool that could help put the evidence-based practices clients learn in therapy at their fingertips, around the clock. Researchers asked themselves: Could a chatbot trained in Socratic dialogue help people challenge distressing beliefs they hold about themselves, others and the world?

Large language models seemed perfect for Socratic dialogue. Users can evaluate their own beliefs through answers to questions and adjust them as needed to be more helpful or realistic. This process, known as cognitive restructuring, has been associated with symptom improvement.

“What makes Socrates 2.0 unique is that it involves multiple AI entities that interact with one another to provide the user with a high-quality experience — beyond what current therapy chatbots on the market can do,” Dr. Held said. “It’s essentially like having an AI treatment team with an AI therapist and two AI supervisors by your side at all times.

“This initiative marks a new era in innovation, not just within our organization but potentially setting a precedent in the integration of generative AI and mental health care nationwide.”

Traditionally, therapists who provide cognitive behavioral therapies have given their clients worksheets to practice the skills they’re learning in their free time. While these worksheets have proven to be effective, they aren’t engaging and, often, aren’t well-used by clients.

Researchers wondered if they could replicate those effective therapeutic tools in a more engaging way using modern technology.

Road Home’s Sarah Pridgen, MA, LCPC, manager of research operations, brought this question to her husband, Sean Pohorence, PhD, an independent researcher who works with AI and machine learning. He offered to help build the prototype for Road Home, and

within a week, Socrates 1.0 impressed the team.

After some testing, the chatbot displayed some limitations that can be common for large language models, like giving repetitive answers in conversations. Knowing this can be distressing, particularly in conversations about mental health, Dr. Held and his team questioned how they could improve upon it.

“That’s where the fun began,” Dr. Held said. “We had the realization that this can be a good tool, but it had limitations. We connected this to how we handle training people. Psychologists can sometimes cling to the use of one question. So, what do we do for them? We provide them with supervision to improve their style of questioning.”

That’s where the idea for Socrates 2.0 was born.

When psychologists are in training, supervisors provide them with feedback on how to make their sessions more effective. Dr. Held and his team translated this idea into the creation of an AI supervisor that would provide the AI chatbot with input on how to improve its questioning.

Humans can sense when someone’s beliefs shift during a conversation, but Socrates 1.0 had a difficult time recognizing this. By adding an AI supervisor to help improve conversations and an AI assessor to monitor shifts in beliefs, looping or redundant answers were reduced. This helped the chatbot acknowledge progress and appropriately wrap up sessions. Altogether, these three AI entities — therapist, supervisor and assessor — form Socrates 2.0.

Dr. Held, Pridgen and their team completed a feasibility study of Socrates 2.0 in which users were given unlimited access to the chatbot for a month. Most users interacted with the chatbot for five minutes at a time as it fit into their day. This resulted in moderate reductions in common symptoms of depression, anxiety and chronic stress.

People felt they could open up to the chatbot without fear of human judgment. They used it as a practice ground before talking to their

therapist or to handle difficult situations, like a panic attack at 2 a.m.

Now, Road Home researchers are conducting additional feasibility and safety studies on Socrates 2.0. They are collaborating with several partners to test the tool in various contexts.

“The idea is that you would use this tool in tandem with working with a trained professional — a person who can help guide you on how to use it to shift the beliefs you’re struggling with,” Dr. Held said. “We want clients to develop a sense of self-efficacy and have the tools and means to feel better.”

How can therapists benefit from this tool?

In a separate feasibility study with therapists, some expressed concerns about Socrates 2.0 replacing their jobs. Upon use, most found it to be a helpful tool in their therapeutic toolbox, similar to the aforementioned CBT worksheets outside of the clinical space. Some therapists also used the tool to workshop their approach to their own clients.

This led researchers to develop Socrates Coach, a separate chatbot that aims to help therapists hone their Socratic dialogue skills. In this version, the chatbot roleplays as a client whom the therapist works to treat. Therapists receive feedback from AI “supervisors” on how to improve their dialogue.

This initiative was funded by a grant from Face the Fight®, an organization founded by USAA, Reach Resilience and the Humana Foundation that aims to raise awareness and support for veteran suicide prevention.

“We’re fortunate to be part of that because they’ve entrusted us with building Socrates Coach and a couple of other tools to improve clinicians’ abilities to develop effective interventions,” Dr. Held said.

He and his team are in the midst of a larger feasibility study of Socrates Coach with clinicians undergoing training for evidence-based PTSD therapy.

Can this tool influence mental health care everywhere?

While many throughout the mental health field are developing AI tools, Road Home was one of the first to develop a multi-agent approach and complete feasibility studies.

“Many people are looking to Socrates 2.0 as an example,” Dr. Held said. “We’re developing science in a clinically applicable way. We’re getting this tool out there, in front of people, getting information from real users and using feedback to make changes.”

This approach is not going unnoticed. Rush is one of a handful of nationwide collaborators in the Center for Responsible and Effective AI Technology Enhancement of Treatments for PTSD, or the CREATE Center, at Stanford University. The center received an $11.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to develop tools like Socrates 2.0 that can assist clinicians while meeting specific criteria for patient safety, privacy and effectiveness.

Ultimately, Dr. Held and his team hope their work can advance mental health care by giving clients a tool they can use in between therapy sessions or as they’re waiting for treatment to supplement their care.

“Once we know the tool is safe and works as intended, the hope and dream is for people to have the option of replacing boring worksheets with Socrates for practice, which can lead to consistent and better outcomes,” he said.

And dreaming even bigger, the team hopes this type of tool, partnered with a coaching model, can become its own form of treatment for certain clients.

“One size does not fit all,” Dr. Held said. “That’s Road Home’s entire driver. The next frontier for care may be to use tools younger generations already know, but have these tools be developed and tested by mental health experts.” —

Road Home Program gives Fitha Dahana-Ellis and her husband tools to cope with the trauma that can affect veterans, service members and caregivers

The path Fitha Dahana-Ellis took toward getting help for herself started with a big statement. She had been struggling to encourage her husband, an Army veteran, to get treatment for what she now recognizes as signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, commonly known as PTSD.

“I opened my big mouth and said: If they had a program where the family member could just go, focus on themselves for two weeks and really process these big emotions that we have and learn how to live with them and have the tools, I would be the first person to go,” she said.

It turns out that Rush’s Road Home Program has such an opportunity — and proved to be just the thing for both Fitha and her husband. Road Home’s approach is that when one person serves the country, the whole family serves. While the program supports veterans and active service members, it also helps family members address their needs.

“As family members, we have our own PTSD — secondary PTSD,” Fitha said. “And a lot of times, veterans — and the caregivers — come out of the military, where they had a really strong support system, and all of a sudden they’re alone.”

Fitha met her husband, an infantryman stationed at the Schofield Barracks in Hawaii, where she lived at the time. He had just come back from an 18-month deployment to Iraq.

“He was glad to be back in Hawaii,” she recalled. “He wanted to run around town, see movies together, explore the island. He was really outgoing and funny. We share the same dark humor.”

They were married within a year. Then, he redeployed to Iraq.

After he returned, he received orders to Fort Campbell, along the border of Tennessee and Kentucky. It was around that time that he started showing signs of PTSD.

“There was a big shift in his personality,” Fitha said.

She noticed he was “wound tighter” than he used to be, short and angry in his communications. He often made a big deal or got upset about things like garbage on the road or people standing too close at the grocery store.

“I felt like I was walking on eggshells,” Fitha said. “I felt like I had to filter myself because I didn’t know if there was something I was going to bring up that would upset him.”

Fitha was already having a tough time acclimating to her new home. She didn’t have the food options she had loved in Hawaii. She couldn’t find the type of public relations and marketing work she’d done before. And her husband’s obligations to the Army meant he wasn’t home much.

“I was in a dark place,” she said. “It was hard. I was taking care of two kids in diapers. I didn’t have friends.”

She felt alone.

It was the middle of the night when Fitha and her husband heard a noise, which they later learned was nothing more than something that had fallen in the garage. But in that moment, he ordered her to grab a rifle and “clear rooms” with him. After things calmed down, he realized what had happened and finally acknowledged he might need help.

“I was so relieved,” Fitha said. “Finally, he was strong enough to admit there was a problem. Now what?”

While her husband was stationed at Fort Campbell, Fitha worked for a couple of years in the Army Career and Alumni Program, now called Soldier for Life, helping veterans and their families transition from military lives back to civilian ones. The week of the incident, Wounded Warrior Project® visited for a presentation about mental health.

“I remember just sitting in that room crying because for the first time in a long time I didn’t feel alone,” Fitha said. “I knew what was coming and that there were resources to help him.”

Fitha made herself two promises after that presentation. She would get her husband involved in Wounded Warrior Project®. Then, she would get a job there.

In 2014, just a year after making those promises, Fitha started working at

Wounded Warrior Project® as a career counselor in the Warriors to Work® program. She continues to serve with the Warrior Care Network® to this day.

Through her work, she became more familiar with the Road Home Program. For roughly a decade, as the family moved around, Fitha said her husband had visited a number of veteran-focused centers and private providers, with little progress to show for it. She wanted him to go to Warrior Care Network®, and he finally agreed to take part virtually in Rush’s Road Home Program.

“I found that everyone at Rush’s Road Home Program is just so nice — the easiest to work with,” she said. “There’s not a lot of egos. I love partnering with them. I was so happy that he agreed to attend.”

After his second day of talking to Jonathan Murphy, PhD, ABPP, clinical psychologist and manager of the virtual accelerated brain health program at Road Home, her husband barged into a room to declare to her that Road Home is “the best program ever.” And Fitha has seen a notable improvement.

“They gave him the tools to not immediately jump to heightened emotions,” she said, noting it is now sometimes in contrast to her own tendencies to tense up in certain situations. “He says, ‘No, let’s think about this.’ That’s the big gift we got from the program. I get to see glimpses of the man I first met.”

When Fitha learned that Road Home had a family cohort, she was one of the first people to register to make good on the pledge she had made before her husband’s decision to attend. But PTSD led to avoidance, and she found herself not returning Road Home’s calls or calling back after hours, when she knew it would be closed for the day. She justified it as being “too busy.”

At that time, she was traveling a lot with the Road Home team and sharing Warrior Care Network® resources with community partners and military service members. Intake clinician Mike O’Connell, LCSW, helped her understand why seeking such help can be difficult for anyone — including her husband.

“He said, ‘When you go out there and ask veterans to leave their homes for two weeks and do something that’s scary, unpack all of that trauma, what you’re going through is very similar to what they’re going through; I want you to think about it that way,’” she recalled. “Unpacking emotions is not fun, especially if you’ve put them into tiny, color-coded boxes that are stored away.”

Fitha noted that working with Benjamin Shulman, MA, LCPC, clinical manager of the accelerated brain health program at Road Home, was also an eye-opening experience. No matter what she “threw at him” in their discussions, he remained calm and asked her to reflect.

“That made me feel really good,” she said. “I’ve been to therapists before where I’ve said things and the therapist said, ‘That’s wrong.’ Not him. He’s

so comforting.”

In addition to addressing things related to her husband’s PTSD, Fitha said the program helped her process the recent passing of her mother, with whom she had a complicated relationship.

“For the family members, the reasoning for coming to Road Home does not have to connect directly to the experiences of the veteran or service member,” said Joseph Zolper, manager of veteran outreach and networking for Road Home. “Leave your veterans or service members aside for a moment. What do you need?”

“When I started helping soldiers transition out of the military, I really did find this is what I was meant to do, this is what I want to do,” Fitha said. “From 2012 on, I’ve been working with veterans. I cannot imagine doing anything else. I’m just so proud to be able to do the work that I do.”

Nowadays, that work includes recounting her family’s story during speaking engagements. Through those events, she often meets other veterans and their families, who connect to different aspects of her story and often share their own. And she encourages anyone she can to use the resources that are available and know they’re not alone.

“If someone comes and talks to me, then I know I’ve made an impact,” she said. “Sometimes it may come back years later. Just putting my story out there makes it more comfortable. It breaks that stigma, too. It makes me feel like I’ve done my part.” —

Growing up, some people are sent to a military school. But for Tom Horvath, military school was a choice. From a young age, he knew he wanted to serve his country, and he enrolled at Marmion Academy in Aurora, Illinois, to explore this interest.

While there, he soon found out it was more than an interest; it was a calling.

“It felt like something I needed to do,” Tom said.

After graduating from Marmion in 2006, Tom joined the U.S. Army Infantry and was part of an airborne division that conducted parachute missions. He remembers basic training as being a culture shock.

“I joined just a couple of days after I turned 18,” he said. “I graduated in May and left for basic training in July. It was a weird transition. They tell you everything you need to do to the point where you don’t have to think anymore.”

At basic training in Georgia, the experiences Tom shared with his peers, like testing protective equipment in a gas chamber and gaining confidence climbing tall structures, bonded them as a team. After earning his crossed rifles, there was a lull before training ramped up again.

Because of his experience at Marmion, Tom was able to enter the Army as an E-3, as opposed to an E-1 or E-2.

“I progressed in rank more quickly than the average person,” he said. “This gave me almost immediate exposure to leadership positions.”

Tom went on to Fort Irwin National Training Center, where he thought he was preparing for deployment to Iraq. But soon, Tom was given a map of mountains and understood his orders had shifted from Iraq to Afghanistan.

“Afghanistan was a crazy experience,” Tom said. “At the time, we had a journalist embedded in our unit, and he wrote an article for Vanity Fair

called ‘Into the Valley of Death.’ There was no running water or electricity. Some groups spoke different languages from others, making it difficult to communicate between neighboring places.”

Tom’s unit was stationed close to the Pakistan border, which, at the time, was traveled by members of the Taliban. His unit was tasked with keeping members out of Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital city.

“There was a lot of fighting,” he said. “After I hit my deployment goal and completed four years, it was time to be done. We came back with a lot fewer people than we went with. Everybody who joins the service is willing to do that.”

A few weeks after he returned home, Tom started college classes.

It wasn’t long before he realized how different military and civilian life can be. He needed to take a few days off to attend a friend’s wedding. Used to providing thorough details in the military, he shared his full plan with his professor but noticed the professor stopped listening midway through.

“You don’t need that level of detail outside of the military,” Tom said. “That’s when I realized that if I decided to stay in bed and do nothing, the world would go on, and no one would look for me. It’s completely different from the military. There, if you’re not in formation 15 minutes ahead of time, your phone would be blowing up.”

He also experienced shifts in his friendships with old high school friends.

“The connection was not the same anymore,” he said. “I felt like a fish out of water. It took time for this stuff to materialize and for me to

realize it. I was doing things to fill these voids that leaving the military created.”

Tom began to suspect he had a problem with alcohol, especially moderating the amount he drank when he went out. He also noticed times his heart would race in class.

“When you think about it, it makes sense,” he said. “In the Army, we’d all be sitting around, hear shots and need to go from zero to 100 in a few seconds. The brain produced a ton of stress hormones. I wasn’t prepared for coming away from that. Without that accountability and camaraderie, it ended up being destructive.”

About a year after his military service, Tom sought help.

He tried a couple of counselors, but none were a good fit. Some seemed unprepared to discuss details of his combat. He had some success with counseling through the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, but sessions were too few and far between. Then, a family member recommended he try the Road Home Program.

“The first time I got in touch with Brian [Klassen, PhD, clinical psychologist and Road Home’s director of strategic partnerships], he said he could meet later that same week or the next week,” Tom said. “Ultimately, that’s where things turned around. The frequency of care was a noticeable difference from day one. If something happened in my life, I knew I’d have a place to talk about it in a week and could get through it.”

Though Dr. Klassen is not a veteran, his military cultural competency helped Tom feel like he was talking to a fellow veteran, free from judgment. He asked questions others didn’t. And he offered therapy over the phone, making it more convenient for Tom to get the care he needed.

“He told me the brain remembers trauma like a disconnected jigsaw puzzle,” Tom said. “If you

don’t link the pieces, your brain uses the time when you’re sleeping or moments throughout the day to connect things.”

The tools Tom learned in therapy helped him process his trauma and confront excuses to drink in excess.

Since starting therapy with the Road Home Program, Tom feels his days aren’t interrupted by his military experiences anymore.

“Everything is different,” he said. “Before, there would be little triggers. I’d be fine talking about it, but I’d feel it for the whole day afterwards. It would take me a while to recalibrate. Now, things are OK after discussing my experiences. I have a lot less anxiety.”

With a greater awareness of triggers and the tools to process them, life opened up for Tom. He could relate to his family and friends again and build relationships where he previously felt closed off.

“I tell my family that they served, too, and in some ways, it was even more stressful for them,” he said. “If you’re not calling home for whatever reason, could be you’re just watching a movie, they have no idea what’s going on. There’s that not knowing part of it.”

And following a lifelong interest in sports and movement, Tom finished college with a degree in exercise science and went to a physical therapy assistant school.

“In the military, there’s heavy physical demand, and even with as active as we were, people were getting injured and hurt,” Tom said. “I didn’t know the answer at the time, but it seemed there would be a better solution than pushing ourselves until something hurt.”

Today, in his work as a physical therapy assistant, Tom sometimes meets other veterans, and he feels an immediate connection with them, even if their branch or era is different from his. He encourages other veterans in need of help to ask for it and keep trying to find the right therapist.

Looking back on his growth, Tom said he’s proudest of being open to therapy at Road Home and giving them a call.

“Not talking about your deployment is viewed as a sense of strength, but now, I’m more comfortable speaking about it and recognizing how to acknowledge it.

“You have to ask people for help. The whole ‘suck it up and drive on’ thing doesn’t work. In trying not to become a burden, I actually did become a burden. It’s OK to admit that things aren’t good and that you need to find someone. There’s a lot below the surface that I didn’t realize. Therapy takes it away so you can have more energy and feel better.” —

When veterans walk through the doors of A Safe Haven Foundation, many are carrying the heavy weight of housing insecurity, uncertain futures and the lingering impacts of military service. After A Safe Haven Foundation lost grant funding for its veteran suicide prevention programming, the Road Home Program and Rush University student volunteers stepped in to fill the gap — offering not only resources but also connection, care and a renewed sense of community.

A Safe Haven Foundation, or ASHF, is a Chicago-area nonprofit that provides housing, support services and career pathways for individuals in crisis. Its Veterans RISE program, which stands for resources, information, services and empowerment, is where the Road Home Program steps in with added support. Together, they’re making sure veterans don’t just survive but begin to thrive again.

For Dee Garcia, a volunteer at ASHF and veteran who previously received care at the Road Home Program herself, this work is deeply personal.

“Every day is a struggle for these vets — housing, employment and the uncertainty of what comes next,” Garcia said. “I wanted our programming to feel less like another lecture and more like a chance to breathe. A space where they could laugh and feel seen.”

That spirit of care shows up in every detail Garcia coordinates, from choosing meals the residents of ASHF’s veteran housing truly enjoy to organizing movie nights, game nights or educational sessions led by Rush University students through the Rush Community Service Initiatives Program, or RCSIP. Students, faculty

and staff who take part in this program use their talents to engage in community-based volunteer experiences that both address local needs and strengthen their ability to work with diverse populations.

At ASHF, medical students lead group events and workshops, develop relationships with veterans and support programs aligned with Rush’s community health priorities.

For second-year medical students Praewpailin Rich and Toni Zheleva, who co-lead the partnership between the Road Home Program and RCSIP, the opportunity to connect with veterans has been transformative.

“When we learned that A Safe Haven had lost its funding, we felt we could step in to continue providing support in small but meaningful ways,” Rich said. “Seeing how engaged and appreciative the veterans are reminds me of the power of human connection and how just a few hours a week can help someone feel heard and uplifted.”

Zheleva agrees.

“Our goal was to fill a gap by creating consistent, engaging programming that helps veterans feel supported, valued and connected,” she said. “Many have told us they look forward to our visits — that energy and sense of belonging make all the difference.”

Through workshops on emotional awareness, suicide prevention and resilience, students help create space for meaningful conversations — conversations that can save lives. At the same time, Garcia makes sure there’s always room for lighter moments, because joy and community are powerful medicine, too.

“Those moments help break down walls,”

Garcia said. “Little by little, you see veterans start to relax and open up. That’s where healing begins.”

According to Brian Klassen, PhD, director of strategic partnerships at the Road Home Program, the collaboration grew out of a shared mission to serve veterans holistically. National studies show that veterans without housing are at significantly higher risk for mental health challenges and suicide, underscoring the need for integrated care.

“Road Home was already addressing mental health needs, but we understand that we can’t begin to address trauma if someone is worried about their next meal or a warm place to sleep,” Dr. Klassen said. “That’s where A Safe Haven comes in. I think that’s what makes this so unique. Rather than one organization trying to do everything, each partner focuses on what it does best. And that’s how we make the biggest impact.”

The collaboration allows each organization to play to its strengths: ASHF provides housing and case management, while the Road Home Program contributes clinical expertise, mental health education and volunteers from across Rush.

By combining clinical expertise with community-based support, the Road Home Program extends its mission beyond therapy rooms, meeting veterans where they are and strengthening the foundation for long-term healing.

“We can’t just wait for people to come into our clinics,” Dr. Klassen said. “Sometimes, we have to go to them. We have to show up consistently,

Together, Rush’s Road Home Program, Rush student volunteers and A Safe Haven Foundation help Chicago-area veterans build community, improve mental health and take steps toward stability

listen and remind them why they matter.”

The impact is already clear. Garcia recalls one veteran who relied on gas cards provided by the Road Home Program to attend job interviews. That support helped him land steady work as an extra on local television productions like “Chicago Fire” and “Chicago Med.” Others, once withdrawn and isolated, now show up to community meals, share stories and even return to volunteer after leaving the program.

“These opportunities to connect with kind people and engage in recreational programs are powerful ways to decrease loneliness and improve mental health,” Garcia said. “Even something as simple as an Italian beef sandwich shared with friends can make someone feel cared for.”

Though still in its early stages, Dr. Klassen said the collaboration is already helping both veterans and students grow.

“Our medical students learn to build rapport with people who may have had very different life experiences,” he said. “They’re learning cultural competence with military populations — a skill that’s often overlooked but essential in health care.”

Clinicians nationwide often aren’t formally trained in understanding military culture or its impact on health and identity.

“A veteran might sit across from a provider who doesn’t know what their branch of service means, what deployment was like or how their experiences shape the care they need,” Dr. Klassen said. “This partnership gives students a chance to close that gap — to meet veterans

as people first, to listen and to learn. Veterans deserve care that supports the whole person.”

Rich said that experience has already shaped how she’ll approach her future work as a clinician.

“Working with veterans has shown me that healing often begins with being seen and heard, not just treated,” she said.

Zheleva agrees, adding that it has reinforced her commitment to trauma-informed care.

“Through creating space for veterans to connect during challenging times, I’ve seen how community can be profoundly restorative — how coming together in compassion and shared humanity can offer strength, even amid hardship,” she said. “It’s a truth I’ll carry with me as I move forward in my medical career.”

As the work evolves, support helps to provide better winter coats, boots, transportation cards and upgraded living spaces for veterans at ASHF. Dr. Klassen hopes that as the program continues to mature, it can serve as a model for similar initiatives across the country.

“There are shelters in every city that serve veterans,” he said. “With the right collaboration, this kind of community-based, culturally informed support could be replicated anywhere.”

The initiative continues to thrive through the dedication of volunteers — from Rush students and staff to community members who give their time and compassion. Together, they provide meals, lead activities and create meaningful connections with veterans at ASHF. Volunteers coordinate with staff at both organizations and

complete ASHF’s onboarding process to ensure the experience is supportive and respectful for everyone involved.

For Garcia, the most rewarding part is simple: the smiles, fist bumps and hugs from veterans who know they’re not alone.

“I used to not even be a hugger,” she said. “But when someone says, ‘Thanks for the blanket,’ or just smiles after a good meal, that’s enough reward for me.”

Through the partnership of Rush’s Road Home Program, ASHF and volunteers who give their time and compassion, Chicago-area veterans are reminded of something powerful: Home isn’t just a place. It’s the people who care for you along the way. —

The evidence-based care provided at the Road Home Program is transforming people’s lives. Knowing there are far more people around the country who could benefit from Road Home’s leading-edge therapy, the program prioritizes training the next generation of mental health professionals in its evidence-based, culturally competent methods.

Recently, Nia Lennan, MSW, LSW, joined the program through Rush’s Legacy Mental Health Fellowship, which supports emerging social work clinicians who seek to provide culturally competent, trauma-informed care in communities that lack access to that care, like those on Chicago’s South and West Sides. The Legacy Mental Health Fellowship is a philanthropically funded collaboration between the Garfield Park Rite to Wellness Collaborative, Rush’s Department of Social Work and Community Health, and Chicago State University’s Master of Social Work Program.

Nia was born and raised on Chicago’s South Side, went to high school in Englewood and witnessed, firsthand, the inequitable access to resources in her community.

“I wanted to give back to the community,” she said. “In high school, I took a psychology class and really liked it. I majored in psychology at the University of Miami and gained an interest in research there.”

Following her undergraduate studies, Nia worked as a clinical research assistant in Rush’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. Her work focused on research partnered with community members. She conducted PTSD assessments with pregnant

women who had experienced trauma, and those who screened positive were offered narrative exposure therapy. This work interested Nia in a career providing trauma-informed care. She went on to pursue her master’s in social work from the University of Chicago.

“Social work really stood out to me because it was flexible enough to allow me to provide therapy or work in policy,” she said. “I want diversity out of my career and to really lean into the equitable treatment of different communities.”

One of Nia’s Rush colleagues told her about the Legacy Mental Health Fellowship, and she was drawn to apply. She is a member of the third cohort of fellows. Prior to her time with Road Home, through the fellowship, Nia led weekly group therapy for men at MAAFA Redemption Project and for women through MAAFA’s sister program, the Beautiful Seed Foundation. She also worked with people individually via Rush’s Social Work and Community Health Services team.

“Some people were trying to get through their day-to-day, and it was great to provide them with space to let out their stressors and talk about their challenges with interpersonal relationships,” she said. “I’ve been able to work with people with a lot of different diagnoses. This has helped me grow clinically and become more flexible, too.”

Last year, Nia shadowed Road Home’s accelerated brain health program and engaged in cognitive processing therapy, or CPT, training. She wanted to build her skills further and took on additional hours at the program this year. She works closely with Road Home’s Mikhael Yitref, LCSW

“Being at Road Home is exciting because I’m getting thorough training in trauma-focused

modalities,” Nia said. “I have family members who are veterans, including several uncles who aren’t the most open. I keep them in mind as I serve others. This may be the treatment they weren’t able to get.”

Nia will soon provide one-to-one therapy with Road Home clients and may conduct group therapy later in the academic year.

“Training here has been hands-on,” she said. “In grad school, you get internships, and I’m grateful for the ones I had. But I’ve seen more diverse mental health presentations here, and this experience has given me a lot of confidence in my abilities to navigate providing care.

“I look forward to soaking in all of the knowledge available here from so many clinicians who have worked with veterans.”

In the future, Nia aspires to become a clinical director and wants to stay in the Chicago area. Through the Legacy Mental Health Fellowship, Nia is offered tutoring for the licensed clinical social worker exam. This credential would allow her to open her own practice if she chose.

“There’s a disparity in how many Black people pass the LCSW exam, so being offered tutoring is helpful in feeling more prepared and easing the stress that comes up with the exam,” she said.

Nia also hopes to apply the trauma-focused modalities she is honing at Road Home, like narrative exposure therapy, in her work with community members who have experienced violence. —

Over the summer, senior leadership and the board of directors from Wounded Warrior Project®, a groundbreaking and long-standing philanthropic supporter of Road Home, visited the program at Rush. Visitors toured therapy spaces and learned more about the impact Rush is making by providing mental health services and resources to our nation’s veterans and service members.

While the evidence-based cognitive processing therapy, or CPT, the Road Home Program offers its clients helps them recover 75% of the time, 25% of clients still experience PTSD symptoms. To help these individuals reach recovery, Road Home is examining CPT in combination with a stellate ganglion block — an injection of an anesthetic into a bundle of nerves in the neck involved in the sympathetic nervous system.

The sympathetic nervous system is overactive in people with PTSD. This nerve block aims to bring the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems into greater balance to reduce PTSD symptoms.

In a clinical trial, participants received this treatment paired with one week of CPT and were compared to a control group that received a placebo with one week of CPT. Both groups experienced symptom reduction, but the group

that received a stellate ganglion block experienced a much larger initial symptom reduction, helping provide an immediate sense of relief.

The Road Home Program received two U.S. Department of Defense grants to further hone its treatment offerings for clients who remain symptomatic after an initial course of CPT.

One is an extension of the above clinical trial with 180 patients divided between the following groups: one that receives stellate ganglion blocks before and after CPT, one that receives one stellate ganglion block with CPT, one that receives a placebo with CPT, and one that receives a stellate ganglion block with a symptom-monitoring placebo instead of therapy. Over the next four years, Road Home, in partnership with Rush’s Department of

Anesthesiology, will test these treatments and evaluate results. Researchers hope findings can improve treatments for people who do not respond to CPT alone.

“When you look at psychotherapy research, it’s stagnated for the past couple of decades,” said Philip Held, PhD, Road Home’s research director. “To make a bigger dent, we need to explore other methods. That’s where Road Home is going.

“We want to figure out how to further improve people’s lives once they go through the Road Home Program.”

The other funded trial will provide virtual care to 300 individuals over four years. Following an initial course of CPT, Road Home will administer subsequent courses of treatment. Some participants will receive more CPT, some will receive prolonged exposure therapy and some will receive non-trauma-focused skills training. —

Each year, the Road Home Program helps more veterans, active-duty service members and military families access life-changing, lifesaving mental health care. We remain committed to advancing evidence-based treatments, training the next generation of culturally competent providers and ensuring we provide all our clients with the best possible care.

Your support makes this work possible.

When you spread the word about the Road Home Program or make a gift, you help connect people with the care they deserve — at no out-of-pocket cost to them. By sharing this QR code, amplifying our social media posts or sparking a conversation about our services with others, you can change or even save a life.

However you choose to get involved with the Road Home Program — making a gift to honor a veteran or loved one, scheduling a tour to see our work firsthand or telling others what you’ve learned in this report — your support can bring hope and healing to more people who need care.

These extraordinary individuals have served our country. They deserve our respect and support. Thank you for being part of our mission.

Sincerely,

Robert S.D. Higgins, MD, MSHA

Executive Sponsor, Road Home Program Ret. Major, U.S. Army Reserve Medical Corps

President and Chief Academic Officer, Rush University Chief Clinical and Academic Officer and Senior Vice President, Rush University System for Health

To learn more about how you can support the Road Home Program’s vital mission, contact:

Michelle Boardman

Senior Director of Development

(312) 942-6884

michelle_a_boardman@rush.edu

To learn more about how your organization can partner with the Road Home Program to advance its lifesaving services, contact:

Sophia Worobec

Executive Director of Corporate and Foundation Relations (312) 942-6857

sophia_worobec@rush.edu