TESSERAE

2023 / Volume 18

Rowland Hall

Rowland Hall

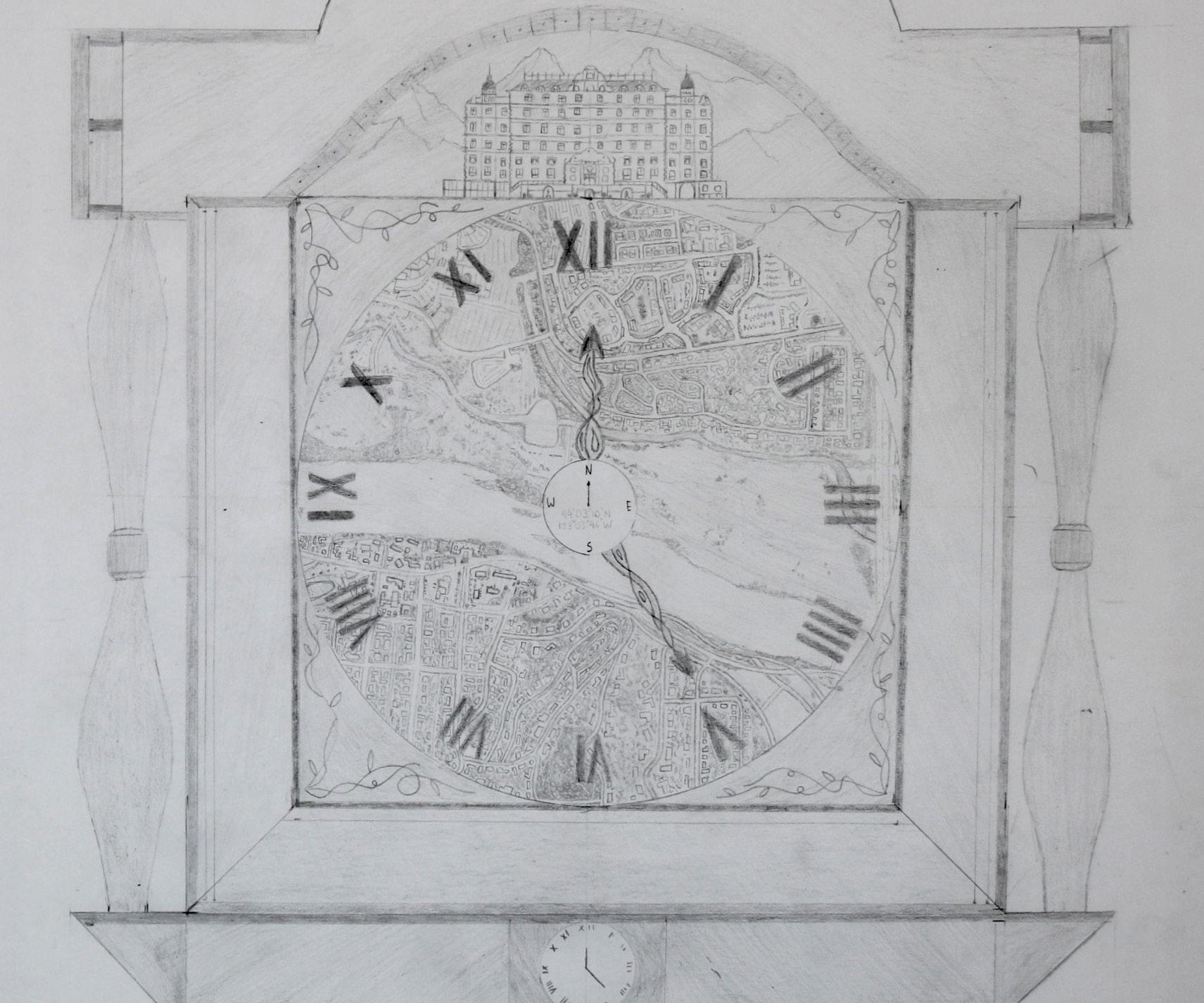

Front cover: Mei Mei Johnson, acrylic

This page: Aurelie Wallis, colored pencil

Back cover: Aurelie Wallis, acrylic

Back cover: Aurelie Wallis, acrylic

Tesserae are tiny stones or pieces of glass cut to the desired shapes to use in mosaics. With the shimmer of reflected light, tesserae work together to create a sense of the hieratic, a Byzantine method of representation that gives the effect of the supernatural, dissolving matter and leaving the light of the spirit. The mosaics in the church of St. Mark’s in Venice use tesserae to form an interior space that is otherworldly.

Rowland Hall

843 Lincoln Street

Salt Lake City, Utah 84102

TESSERAE 2023 / Volume 18

CONTENTS

IGreat Salt Lake Performs a Disappearing Act ... 10

Layla Hijjawi

Bone Broth ... 12

Quinn Yeates

Salt Along the Desert ... 15

Kendra Larson

Forever Chemicals ... 19

Layla Hijjawi

Fantastical Fungus Forest ... 21

Asher Orenstein

A Giant Skittle ... 25

Evan Weinstein

Owls: Vermilion Vitality ... 30

Erika Prasthofer

In the Garden ... 35

Ruby Jeschke

Fallen Peaches ... 39

Nadia Scharfstein

2

Mackenzie White, ceramics

Self Portrait of an Origin ... 42

Layla Hijjawi

Great Grandmother ... 44

Sophie Hu-Lieskovan

Kerosene ... 50

Gabriella Miranda

Not Even the Moon Can Cure Us ... 53

Erika Prasthofer

In the Pocket of County Mayo ... 54

Gabriella Miranda

Lorelei ... 56

Nadia Scharfstein

In Place of Dual Citizenship ... 58

Layla Hijjawi

Less or More ... 60

Katerina Mantas

Prenatal ... 62

Gabriella Miranda

II

3

CONTENTS

III

Hospital for the Neurologically Impaired ... 66

Quinn Yeates

Excerpt from “Order in Disorder” ... 68

Caelum van Ispelen

Blocks ... 70

Ruby Jeschke

Virtual Inquisition ... 75

Sophie Baker

Ghost & In Grief ... 79

Winston Hoffman

Anonymity ... 80

Nadia Scharfstein

A Step-by-Step Guide to Becoming a Fossil ... 85

Sophie Baker

Spectral Illness ... 86

Caelum van Ispelen

4

IV

Catching Sun ... 90

Quinn Yeates

Common Divinity ... 92

Mattie Sullivan

Phantom Limbs ... 96

Quinn Yeates

Śūnyatā ... 98

Mattie Sullivan

Phaëthon ... 100

Lucy Dahl

The Moth ... 102

Mattie Sullivan

Sparagmos as Renaming ... 104

Layla Hijjawi

Divine Zoochory ... 107

Quinn Yeates

5

My Materialism ... 110

Sophie Baker

Interview ... 112

Rio Cortez

Interview ... 118

Nicole Walker

Ballast ... 124

Caelum van Ispelen

V

6

CONTENTS

ARTISTS

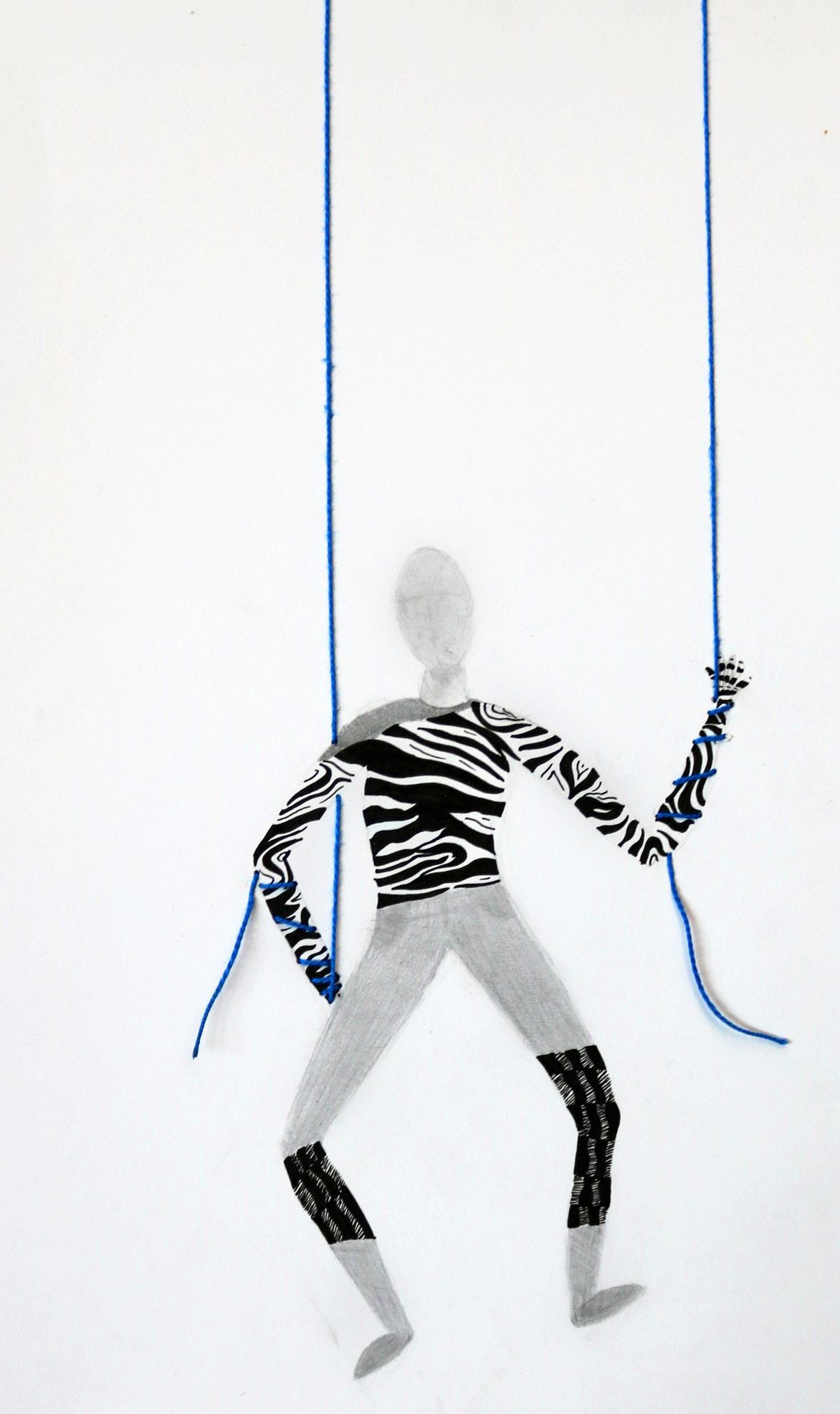

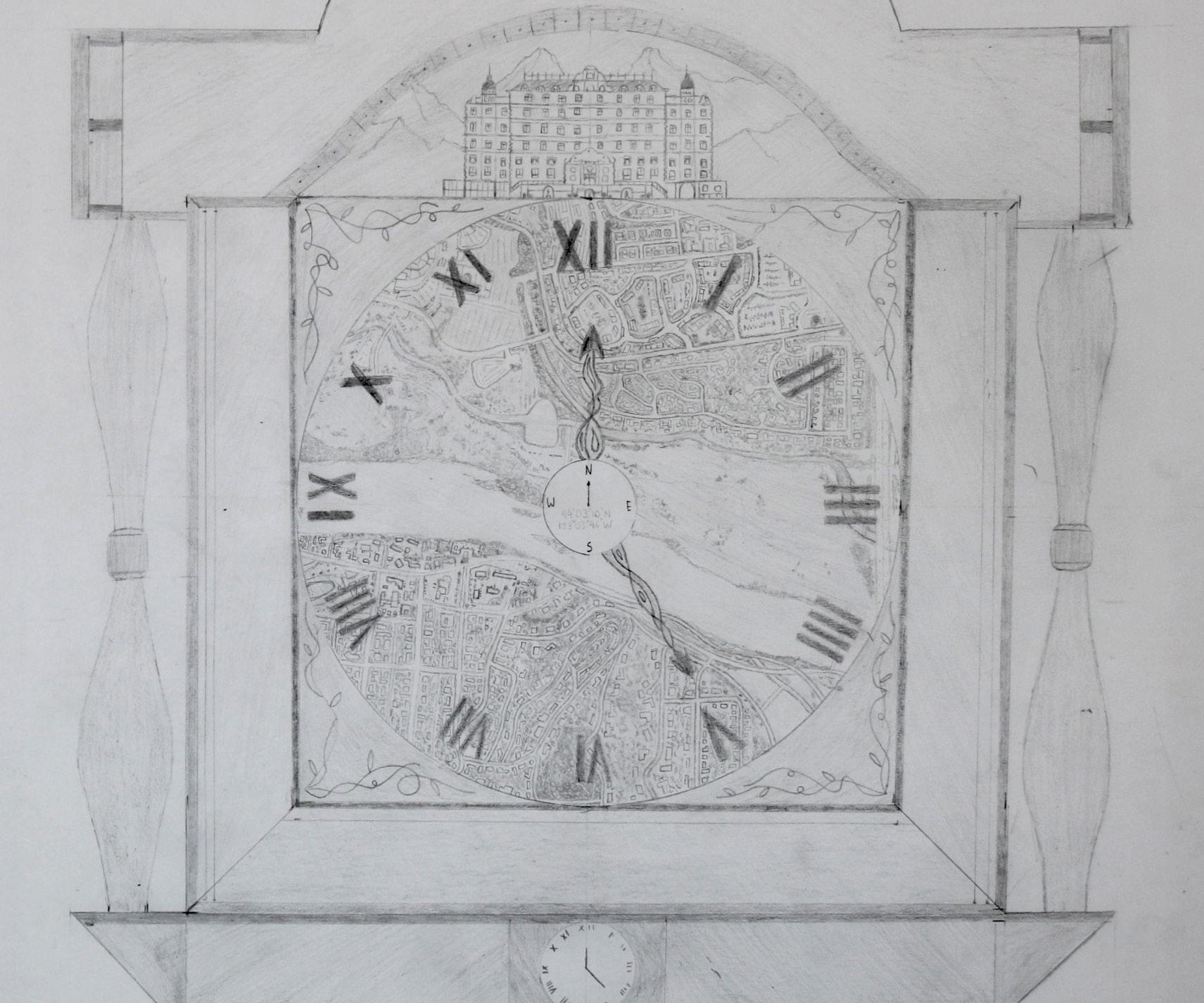

Omar Alsolaiman ... 8, 55, 81, 101

Sophie Baker ... 71

Madeleine Bateman ... 32, 94

Anaïs Bray ... 99

Eli Borgenicht ... 58

Sarah Carlebach ... 83

Lucy Dahl ... 23, 63, 96, 98, 103

Liam Decker ... 18

Kai Dowdle ... 16

Iman Ellahie ... 20, 36, 49, 84, 87, 111

Logan Fang ... 61

Regan Hodson ... 39, 82

Ruby Jeschke ... 13, 15, 97, 127

Mei Mei Johnson ... 51, 69, 74, 95

Kendall Kanarowski ... 10, 13

Ming Lee ... 64

Jay Lutton ... 24, 103

Reece Miller ... 26

Tripp Rollins ... 22

Annie Nash ... 28, 40

Brock Paradise ... 34, 44, 67

Nadia Scharfstein ... 57

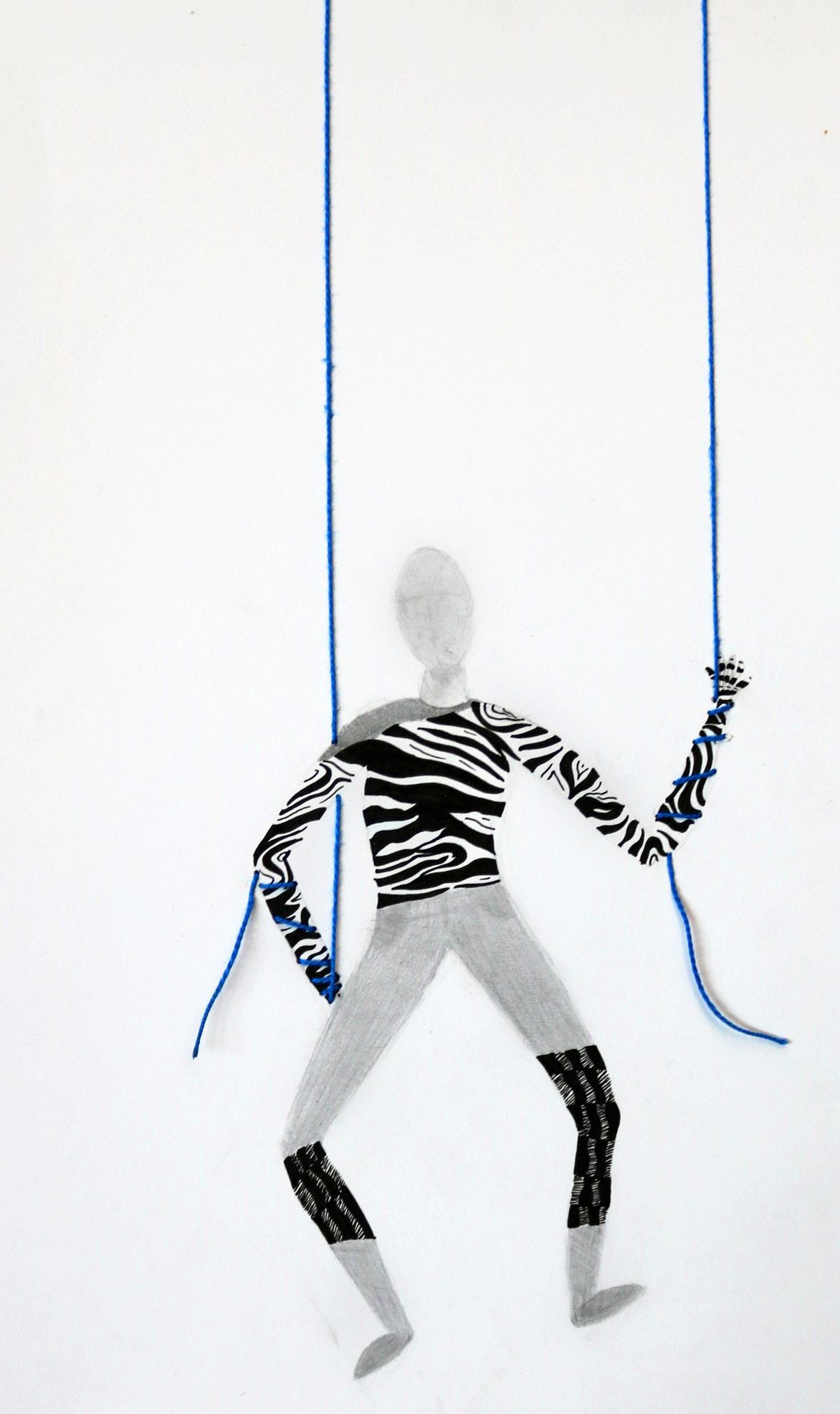

Tenzin Sivukpa ... 24, 52

Zakrie Smith ... 106

Maddi Stufflebeam ... 72

Bea Wall ... 73

Aurelie Wallis ... 104, 108

Claire Wang ... 78, 105

Mackenzie White ... 2

Sophie Zheng ... 38, 89, 91, 92

7

8

“I thought the Earth remembered me, she took me back so tenderly, arranging

I

photography

Omar Alsolaiman,

her dark skirts, her pockets full of lichens and seeds.”

9

—Mary Oliver

GREAT SALT LAKE PERFORMS A DISAPPEARING A CT

Layla Hijjawi

Birds, puffs of summer cotton, ascend in feathered clouds, departing from rippled blue, a blade sharpened by mountain whetstones cleaving through soil and minds and rock and bodies. Bodies of water and bodies of plume, bodies of skin and swimsuit float in hazy swirls of oil on the water’s surface.

A departure: in its wake, the blood of the valley retreats from lake beds, a transfusion from canyons to metal with a sharpness that conjures tears, making invisible what has vanished. Winged shadows cloak absence with fluttering black, an omen of departure carried in talons chased by dirt.

A migration: bird to bone, basins steeped in miracles wither to shell. The memories of saviors, of gulls swallowing mobs of beasts in the mouth of myth eternal, disappear with the plover, the curlew, the avocet, the ibis.

Migration is cyclical, but we snatch water in our palms and subject it to the pressure of human demand until white diamonds sprout from desert veins and our fists.

Cursed city: do not look back at the scorched destruction we leave in our wake. Instead, gaze down at our bodies, caked in crystal and sweat—sweat, a ghost. Our city, phantom of Sodom: there is no return but to salt.

10 Sidebars:

Jeschke, multimedia

Ruby

Give us water, and we will sprinkle the ground in our sulfur rain, refinery-brewed, gnarled iron pillars fracturing red rock. Apologies cannot mend this rupturing, douse fire in the sky, or fill the land’s open jaw, gaping. Its fractaled maw will swallow whole this wave of swarming pests, ravagers of all things good. Leave nothing to be consumed but yourself. Our bodies hum against the earth’s throat in apology for the lack of liquid to wash us down.

Yet in the blur of purple gray, choking through the atmosphere and my lungs, I breathe the mirage of thousands of white and brown birds. In time, all summer cotton falls back to earth.

11

BONE BROTH Quinn Yeates

Aaron Martens is the first. He was sixteen and quiet, and no one much liked him before he died. But after Aaron’s mother finds his goodbye note, Sarah Calloway dumps Hudson Ellis so she can dedicate herself fully to sighing over Aaron dying so young with all his hair and without a sweetheart.

Sarah Calloway, predictably, is the second. Her note says she’s dying to join Aaron. Most reckon that’s why Hudson is third.

Hudson’s mother weeps; Hudson’s father blames Alfred and Abigail Calloway for raising such a silly, stupid girl that would break his son’s heart so.

All is to say: the town takes three days to notice. The well is a good 75 feet deep but only three feet in diameter, and no spring can carry away three full-grown corpses. Everyone floats eventually.

Four men and the mayor haul the bloated bodies out. Dianna Kelpatrick covers her husband’s wheelbarrow with an old quilt so the men can heave the corpses in; blood rusts. No one can spare another quilt to cover them with, so the bodies wobble and stare at the sky as George Holmgren pushes them to the graveyard.

Ben Saunders makes the town’s gravestones. He sees the wheelbarrow trundling past, sees Hudson Ellis’s swollen, color-leeched face bouncing off the metal side, and sighs. He keeps a leather-bound ledger of everyone in Carier: their name, when they move in, when they’re born. Sarah Calloway and Hudson Ellis are on the same page—late November, 1893.

The notebook doesn’t hold deaths; those are for stone.

For Aaron Martens, Ben uses gabbro, coarse-grained and basaltic, said to be of the ocean’s crust. It shines dark in rain.

For Sarah Calloway’s gravestone, he picks pumice, glassy and frothy with the air it trapped in quick-cooling magma. Pumice floats. He chooses rosy rock, like her hair ribbons.

For Hudson Ellis, he picks limestone, pale as his drowned face and pitted with fossils.

The town stops using the well. Three children died and started to decompose in that water. No one can stomach a killer.

Ben sands the stone smooth and thinks of the water that polished the limestone for him. Those waves and rains are far from here, far from this place where those three kids jumped in and it killed them, far from this place where the kids’ families refuse the well water and kill themselves. They are dead from it and dead without it, and the graveyard’s running out of room. The cemetery borders the church and the McKenzie farmhouse, and neither can store corpses. “Don’t lay the dead near cattle,” Rhett McKenzie tells Ben Saunders. “Cows can’t nurse on graves.”

So Ben digs graves doubly deep, stacks coffins in couples. Hudson Ellis’s goes right on Aaron Martens’ because he couldn’t decide which to put with Sarah.

When it rains, the town uses empty coffins as water wells, and that keeps them empty a bit longer.

12

12

Digging the grave for Gloria Ellis’s casket and old Douglas Bryant’s from the ranch five miles over, Ben reaches six feet under, then twelve, and keeps going. The dirt he throws out comes right back down half the time, and he keeps digging. Ben hadn’t ever minded that much, being the only gravemaker in town, but no one had ever died from thirst in town before. Maybe if he digs for long enough, God will let them right back into Eden, consider Adam’s debt paid, punishment waged. Heaven knows all the women have hurt enough, borne enough children, had their waters break and the water break those children.

The Carnes stop carving chairs and sanding fences; they’re wainwrights now. Abigail Calloway, her face looking less and less like her daughter’s, leaves on the first wagon to look after the children. Their parents wave weakly after them, hoping

that soon their kids can cry for them with tears.

Townspeople leave on every horse and donkey and mule; they set free the sheep and hens and pigs to chase water; the ranchers pick up woodworking. But coffins are wood, and wood can become a wagon. So for Lawrence Merrell, 17 July 1872, Ben uses the Merrell’s bedsheet as a shroud. For Lawrence’s wife Cecilia, 22 May 1873, Ben uses his own.

Eleven days after Hudson Ellis jumped after Sarah jumped after Aaron, Ben Saunders drops his ledger in a lake two hundred miles from their graves. So this, he thinks, watching the tanhide soak and the ink bleed, this is where ghost towns come from.

Sitting on the well wall, barefoot with rocks in his pockets, Aaron Martens thought about Ben Saunders etching his name into stone and pushed himself in, picturing someone tracing his name. It’s like tattoos— we get addicted to writing in stone. Papyrus was always going to end in cigarette burns, in cave art graffiti and carving your name on the moon.

After Carier, Ben Saunders always boils his water. Burn the bones out.

13

13

Ruby Jeschke, multimedia

14

SALT ALONG THE DESERT

Kendra Larson

Beware where the rivers and ocean collide in northern California. That’s where the riptides form, where the little green human with a round head on the warning signs above the black sand beaches is rushed out to sea by undercurrents.

Maybe that’s why streams don’t flow into the Great Salt Lake— not anymore. Maybe they are afraid a riptide will pull children under brine.

It’s odd to stand on the California beaches to stand in a drought-ridden land while the largest ocean on the globe hogs more than half of the world’s water but doesn’t invite you to drink.

The breeze of the lake brings the smell of dying: not the smell of flesh decaying but of salt fermenting under the summer sun. It’s the last word of a slowly shriveling soul.

The ocean got too warm; the ocean made us pay. It filled the crabs with a toxin to infect our brains and stop our fishing, but the temperature keeps rising.

Underneath the salt that’s left behind, it’s a treasure trove of poisonous elements and drying dust that the lake decided to leave behind so we would know to stop, to let streams swirl with its salt.

15

Left: Ruby Jeschke, multimedia

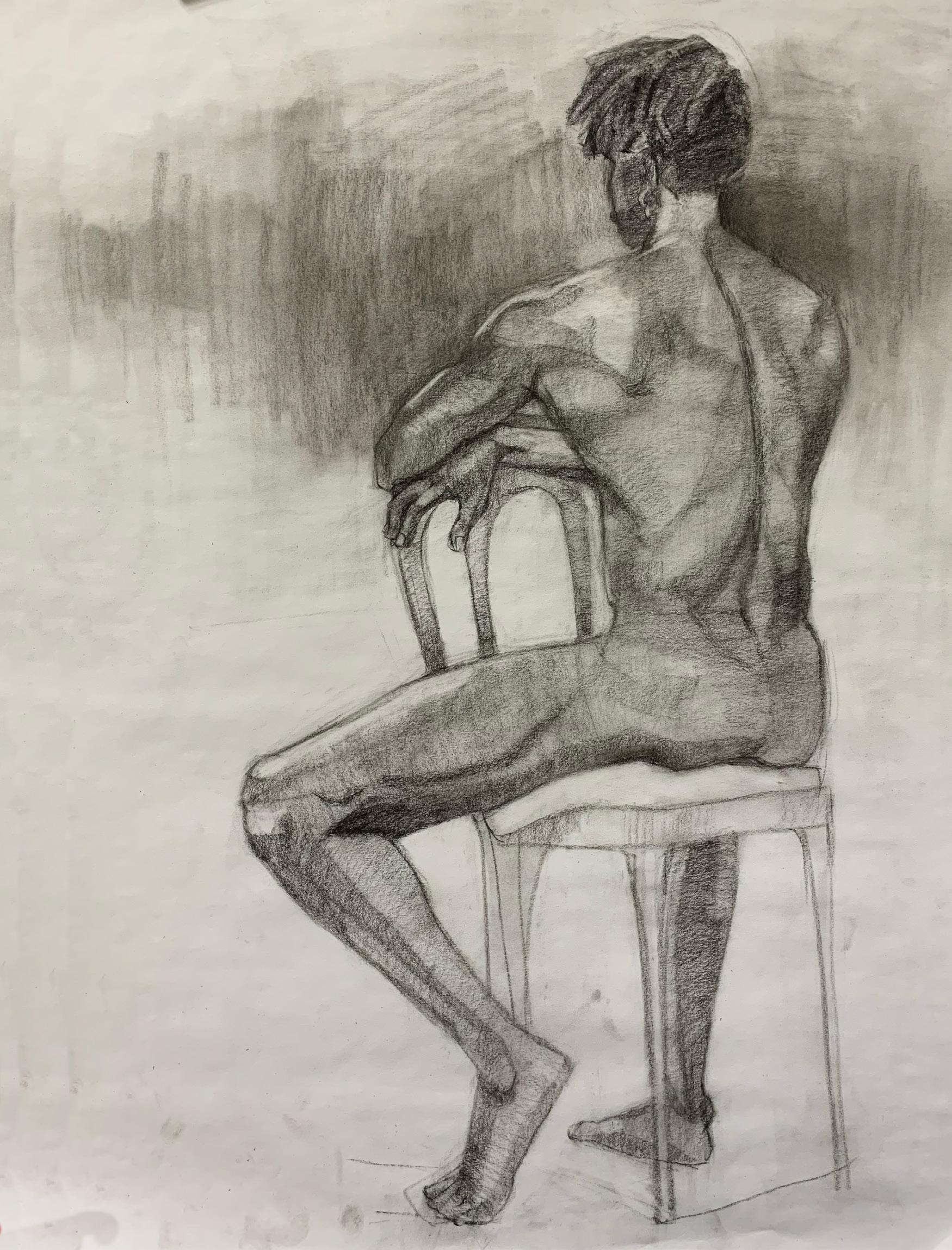

All: Kai Dowdle, graphite 16

17

18

Liam Decker, acrylic

FOREVER CHEMICALS

Layla Hijjawi

Here, the water bleeds. It bleeds from arid south to arid north until the earth scabs into crop circles.

Here, prairie skies collapse into black, and the orange heat of DoD drills rises until its reignition sparked in withered corn and sink taps.

Here, the Ogallala aquifer spans eight states and weaves through fields with alien metal teats, mustard probes that pierce the land’s skin and inject dirt with mistakes made thousands of miles away.

Here, wretched crop stalks stretch and splinter skies into infinity, but the field venom stretches longer. The air trembles with marbled cumulonimbus clouds formed before the horizon was green.

Here, it never rains, so the land blossoms in polyfluoroalkyl haze, and the world drinks itself to death on a draught that slips from esophagus to bone.

19

20 Iman Ellahie, watercolor and ink

FANTASTICAL FUNGUS FOREST

Asher Orenstein

You throw on your boots and raincoat, stomach full and eyes wide open. You open the door of your house and swallow the thick, muddy mist residing in the air. It is the day for the fungus and the mushrooms to dance. The cool swirling droplets cling to drooping leaves as whispers call to you from the forest. Dense colors and alien textures paint your eyes as you venture through the otherworld in your backyard. Your eyes rest on golden oysters like flattened lemons, the aroma of apple jacks and warm cashews gushing from its pores. The bleeding tooth fungus coaxes you, its oozing zits of saturated strawberry jam pulsating from the soil. The monkey’s head, which more resembles one’s bottom, is heavy with glowing ambrosia. A milk cap with its clear and cloudy latex fluid waits to escape. Grizzly bears devour hickory chickens below the hilltop. Royal trumpets sing for the hens of the woods. Peaches and apricots? No! Chanterelle.

The forest darkens; the mist creeps towards you; the toadstools stalk the dead and living alike. An oblivious ant stumbles down a log and she breathes in a spore. The zombifying cordyceps have already infected her brain.

She’s drugged, roots

growing thicker, weaving through her veins. Mindless and robotic, she travels to the dark, dewy roots of a tree to find a graveyard of family, now bewitching abominations of nature. She can no longer resist the urge, her mandibular teeth clasping the bark in one final jerky movement. Her body shrivels and bubbles, and eventually, a glowing tentacle tears through her rotting exoskeleton. The fungus climbs itself until its irresistibly odious form is realized. Her body is no longer visibly ant. Its newfound spores are released into the air, only to attach onto another victim of the mindless fungus.

21

22 Tripp Rollins, graphite

23 Lucy Dahl, colored pencil

24 Jay Lutton, watercolor and ink

A GIANT SKITTLE

Evan Weinstein

The sun packages our solar system, and like little Skittles, each planet has a different identity. On the Blackberry and Apple one, your car drives, stemming from the million-year-old decay of now-fossilized animals once fed by plants, grown from the byproduct of nuclear fusion, a fraction of radiation hitting earth, a sphere where life depends on hydrogen and helium colliding, creating wattage every second with the breaths 565 quadrillion people take in a lifetime. Our sun generates energy best quantified by food: a single Skittle scaled to the size of the sun, a sun that fits 1.3 million Earths, contains only the amount of calories equal to the energy produced by the sun in one second. Comparing one milliliter of water only increasing one degree to energy exerted in a Newton of force over a meter may seem absurd. But consider a grain of rice increased to 1.3 million Earths large, storing four seconds’ worth of energy. When the light turns lime and you press the pedal to accelerate, intending to drive to the gas station and get a packet of Skittles, your brain sees the light turn lime, an influx of energy to the bulb running to that section of your brain, reacting to wavelengths of color, sending a response of power to your foot, increasing pressure. While the idea of a simulated world sounds almost as crazy as a giant Skittle, why couldn’t we be bodiless brains stimulated in just the right places? Your five senses only sense because energy is there.

25

26

Both: Reece Miller, multimedia 27

28

29

Both: Annie Nash, acrylic

OWLS: VERMILION VITALITY

Erika Prasthofer

Excursions are at night amidst the brinks of nature’s verdant, stocky towers,

vivid to predator pupils—but not through gazes of prey with lapis eyes

whose murky glimmering makes them ignorant to the figure loitering high

in the twilight’s denseness. Wings of velvet fringed by comb-like spikes permit her strike

at whatever moment she decides to flap her silent glide and open wide, liberating all heed for the sound of rodent’s shriek, a weep she claims moral—

more so than engulfing one of her own kind where apathy may not feel light.

30

Sidebars: Lucy Dahl, watercolor

Some are horned with feathers— she who hoots—but others hiss, hornless, vulnerable,

prey to their own species. While perched, zygodactyl, adjusting talons against

juniper, cottonwood, limbs of pine, one may sense a tooth’s grind from half a mile

while rotating the neck, a blood-pooling system in the veins activated with circulation’s cut.

Brain and optics sharpen at the vole as it’s hoisted

from its ashen, chocolate habitat of grime, and squeals echo, a screech quivers, dissipates. Creatures grasp their juicy, inner-ruby prizes without mercy

to thrive in spirit, strength, feel their victims dissolve and seep through creatures

more majestic, vital than they were, transmitting, enriching vermilion.

31

32

Both: Madeleine Bateman, oil on canvas

33

34 Brock Paradise, photography

IN THE GARDEN

Ruby Jeschke

When I think of bees, I think of a cloudy day in northern California, a visit to my grandparents that happens at least twice a year, and my grandmother’s wrinkled hands picking lavender.

“We pick flowers for Buddha,” she tells me while gathering a handful of flowers. She places them in the vase next to the two-foot tall statue sitting in her living room.

I’ve known Buddha my whole life. My father was a monk in a zen monastery. My parents met at a Buddhist retreat. He is the happy, laughing man who sits on our coffee table. He tells me to love everyone and that we all are equal. My grandma says the same.

She takes my hand and walks me to the driveway. We step onto the gravel, and I’m greeted by the smell of rain and flowers, the chirping of birds, and the buzzing of bees. I feel the gravel prickling me through my shoes. I shiver in the breeze, and my grandma wraps her coat around me. At this point, I don’t quite understand the significance in what we are doing. I don’t know the intent and meaning that we are trying to put into daily activities. I know I am cold, my mom is inside, and my grandma is picking poppies.

As we walk down the driveway, she starts talking to me, gathering lilacs and goldfields along the way. My grandma used to be a preschool teacher, and as my parents have told me, “she really has a way with children.” It’s because she listens without trying to solve problems, only to really hear someone. I don’t understand exactly what she’s saying, but I am mesmerized, hanging on to her every word.

We get to the lavender plants, and she pulls out a pair of gardening scissors and begins cutting off pieces. I step back, hesitant. There’s a loud buzzing and bees all over the plant. I look down on the bees and can feel them crawling all over my skin. I see myself enveloped and pulled into the lavender, disappearing into the swarm. I take a step back. The heavy fog surrounding us feels somehow fitting.

I see my grandma’s hand again, and she motions me over. “There’s no need to be scared. All of these creatures have the same right to be here as us; they live here too.” I am still scared. I know she’s right, but I don’t want to get hurt. She holds her hand out to one of the bees and very gently pets his back. I’m shocked. I never knew a bee would let anyone get so close. I want to have that gentleness and peace myself. She holds my hand, and together we pet the bee. I feel his fuzzy back. I watch his little legs crawling all over the lavender. The buzzing doesn’t seem as loud anymore. Then she hands me the shears. I realize that this lavender is for Buddha and the bees are for Buddha and all of it is for us as well. The bees and I are the same, even when I am scared of them. I cut pieces of lavender and gather them together. We walk back to the house, and this time, my grandma lets me put the flowers in the vase.

35

Both: Iman Ellahie, watercolor 36

37

38

acrylic

Sophie Zheng,

FALLEN PEACHES

Nadia Scharfstein

Summer’s fallen peaches are gathered in mulch and broken brown leaves, spoiled by muted bruises like birthmarks when really they’re just scars.

They’ll sit until the child sees them lying dead, the skin only a shell for juice, so when he comes outside to watch the moon, he’ll prick the sickly hull with a needle and giggle the pale pulp down his throat.

Had this boy ever known quiet, he would not savor the little things: the tree’s low-hanging fruit meant for no one but him.

He waits for them. He draws them in charcoal, the burnt excess of its origin, just raw bark scattered in the grass after wind storms shake their home.

He hides some beneath his pillow to listen for the oozing fizz at every toss, dripping sugary saliva as they fall in his dreams. He leaves the damp stain to ferment, release an almost petrichor, dry his bedsheet orange until the threads snap and the mattress is molding. But if he piles them high, the peaches will wait for him too.

39

Regan Hodson, colored pencil

40

“Ah the ball that we dared, that we hurled into infinite space, doesn’t it fill our hands differently with its return: heavier by the weight of where it has been.”

II 41

—Rainer Maria Rilke

Left: Annie Nash, multimedia

SELF PORTRAIT OF AN ORIGIN

Layla Hijjawi

Black tangles curl into streaks of dyed gold that blend into brown and the smoky purple curled around almond eyes. Monolids swoop into deep creases. A blemish that leapt from your foot stains my knee muddy. But it is not just this.

The iron of your rage bites acridly in the back of my throat. The rushing wave of your forgiveness is imbued in the flick of my wrist, the slowing of my heart. Fear, elation, pride, devastation wrack my gut, an acknowledgement in freefall that loathing and loving myself extends beyond my body— – a body which does not belong to me in full, a body pumped with your blood, your back, hands, hair, your teeth, mine through inheritance.

I find no solace in gazing upon myself, no resolution to who I was, who I have become, who I will be.

42

I sift through yellowed Polaroids from 1987 inlaid with the pixels of 2019. Gaze upon myself [yourself].

I possess only a shattered, shifting visage, your body leaking desperately through the cracks, surrounding me. How does one depart from skin which they share?

I am your shrapnel, flying from my roots to which I cannot fully return but become all the same. A beginning as both in-between and end, splitting from your flesh which pierces through me until the shards of your body dissolve, and now I have your chin.

To deny you is to deny me is to deny the curve of our cheekbones, hummingbird in our tongue, the echo of your empathy, your naiveté staining my teeth, soft with cavities like yours that will spread until you are all I taste. Gaze upon yourself [myself].

It is unclear where daughter ends and mother begins.

43

44 Brock Paradise, photography

GREAT GRANDMOTHER

Sophie Hu-Lieskovan

Ihave always felt a deep connection to the past, not in a historical sense, but in a creak open the family album, search through old records, and ask Grandpa about his childhood sense. Part of this stems from my insistence not to lose the past and my fear that, one day, the stories of my grandparents will be lost to my descendants and my family will unknowingly lose a vital part of their identity. So I ask, and I write, and I keep, and someday, I shall bind together the stories of my ancestors and give them to my children, and they will read them, and the stories will go on. This particular story is one of my great-grandmother and her son, my lao yeh grandfather, who was born in 1940 and lived through decades of rich, devastating, and beautiful history, and whose life continues to fascinate me long after his death. My grandfather was born on October 21 in the village of Shandong to a mother and three doting older sisters. His father and older brother had left for Dongbei to find fortune, unaware that my little lao yeh was in his mother’s womb. Though my great-grandfather came from a wealthy merchant family, he was a poor farmer, and the disconnect between him and his wife only weakened the financial status of my poor great-grandmother.

As a result, my lao yeh grew up in a poor household, and this, combined with the Japanese occupation and the rationing during World War II, made sickness and hunger common themes in their home.

When lao yeh and his youngest jie jie were three or four, they were infected

with cholera. I never asked my grandfather for details, but I imagine lao yeh and his youngest jie jie lay in bed, wreaked with pain, lightheaded, vomiting onto the floor, their mother wiping vomit off their clothes and mouths and listening to their sobs through the night. In those days, it was undeniable to mothers and society alike that daughters were worthless compared to sons. Sons could support their families, but daughters could not. So my great-grandmother, laden with a heavy conscience and heart, spooned the extra rice and water into lao yeh’s mouth and fed him any traditional herbal medicines she could scrounge to pay for. In return for his recovery, his jie jie slowly declined, lightheaded and in pain, until one day, my lao yeh woke up, and she did not.

It was summer, I usually imagine, and my great-grandmother dug the grave by hand, not wanting to burden her young daughters with the task. They were poor, so she did not have much to offer her youngest daughter except for a few tears, silent and hidden, and the callouses on her hand as she dug into the soil.

When I was younger, I was hesitant to feel empathy for my great-grandmother. I couldn’t understand why she favored her son over her daughter, even as it led to her daughter’s death. However, as I grow older, I have begun to understand her decision. At that time, the birth of a daughter was a disappointment, as daughters could not contribute substantially to the family economy and were a financial burden: they were only temporary mem-

45

MIAN’AO

Hope Thomas

There I sit in my room. The curtains hang in front of the windows, shutting out the outside world from the haven of my room. It wouldn’t have mattered if the curtains had been drawn because night had already fallen. I sat in darkness with my 太婆婆’s (great grandma’s) 棉袄 (mian’ao) draped over my lap. A million thoughts cloud my head about a range of things from my past to my present to my future. And yet with all the commotion of my thoughts, my mind is devoid of ideas about how to quiet it, at least enough so I could get some sleep. On restless, hopeless nights like this one, nine times out of ten, I wear her 棉袄 (mian’ao). On top of being a fashion delicacy, it has sentimental value for me. It’s a traditional, cotton-padded coat made many years ago when she still lived in China. Each detail is so refined, so precise, each thread of silk so fine and delicate. On one side, ink was blotted and bled into the embroidered white silk, and four types of flowers danced separately around the body and sleeves. On the other side, a deep, royal blue spread across the coat’s form with swirling dragons placed around the silk. But the best part of this precious coat is how it brings me closer to my 太婆婆 (great-grandma). She and it wrap me up in a warm, downy hug whenever it makes contact with my skin, and now, I feel close to her. I feel her eyes staring into my blue ones. She always loved my stark blue eyes. And she squeezes my hand like she used to at the home. My 太婆婆 (great-grandma) left before I could appreciate our connection, before I could hear her stories about how she fled communist China, before I could taste her delectable food, and before I could learn Chinese and speak with her. But through her coat, I know she’s with me, and I Iisten to her words of love. “我在这儿,我离你不远。我跟你一直一起

” (I am

here, I’m never far. I am with you always).

bers of their natal families. Even though great-grandmother cherished her youngest daughter, she was trapped in the knowledge that she and her daughters were worthless and that her son was critical to keeping the family name alive, so she could not defend any thoughts except to save her son. At this time in China, the Japanese

occupation was an undeniable struggle to add to the growing list of worries for the residents of Shandong province. This was no exception for my great-grandmother and her children. When my lao yeh was only recently graduated from a swaddle, the Japanese army invaded. My great-grandmother and her children had to run for the mountains to

46

hide. I was told that my lao yeh’s older sisters ran for him and then handed him off to their mother, panic weaving through their minds, running for their lives and dignity, meager provisions stuffed into their pockets, vanishing into the trees. They stayed in the mountains for days, and they came home when the battle was over. I did not dare ask my grandfather what he saw when he came home. Some history is best left unknown. Years later, when my lao yeh was at the age to begin attending school, my great-grandmother knew she did not have enough money to send all her children to school, so she asked her daughters to leave school and work, knowing that her son was the most important of her children to become educated. My lao yeh’s sisters agreed, still nursing a love for their young brother that outweighed their hunger for education, and so they worked, sewing, spinning, and selling their measly crops in the street, sacrificing their life for their younger brother, the gem of the family who took care of his sisters even at his young age, understanding their sacrifice.

My great-grandfather did not return even as his daughters grew into women and his youngest son grew to be eight years old, and so in 1948, my great-grandmother packed up her children, her possessions, and provisions for the trip and began on the long road to Dongbei to find her husband and her oldest son. They traveled by foot to the shore of the Bohai Sea, my grandfather recalled, and then his mother, steadfast in her courage, spent their remaining money for fare on a small, lonely, wooden boat with what I imagine to be a water-worn hull and agecaked wood. Lao yeh told me later that when they were far from shore, a sea turtle began to swim towards their little boat, and he

knelt to the ground and prayed, knowing it was capable of tipping their boat. I imagine his sisters wept in terror, but great-grandmother would have sat there quietly, clutching her daughter’s hands and watching the sea turtle with the silent, raging eyes of a dragon. Do not come near my children, her eyes said. We have suffered enough.

When the boat touched land in Dongbei, my great-grandmother left and began searching for her husband. I can see her now, standing on the shore, peering into the city, her daughters hiding behind her, lao yeh clutching her stained skirt, dangerously beautiful in her determination. When she found her husband, I imagine he wept at her feet as she stood, her chin lifted with dignity, the picture of elegance. I have come for my children, she thought. I did not come for you.

My great-grandmother, perhaps

47

watercolor

Lucy Dahl,

rightly, never forgave her husband. She had suffered greatly, alone with her daughters and baby son. Her youngest daughter had suffered in death, and she had been unable to do anything, understanding that her son was much more important. She had watched her children grow thin, her daughters go to work, and her pantry grow empty. She had carried her children barefoot, running away from the invading Japanese army, fearing what would happen to her if she faltered or failed. So I do not blame her. I do not blame her decision to be buried away from her husband’s family grave site. I do not blame her for carrying resentment in her aging heart. And I do not believe she regrets the decision now, watching me write from Heaven, perhaps proud, perhaps wistful, perhaps reliving the moments that so defined her heart, and now, eighty years later, captures mine.

48 Right: Iman Ellahie, acrylic

49

KEROSENE

Gabriella Miranda

And there it is, tonguing the pavement, full-moon arteries tart from pomegranate twine flossed from between my teeth, still-warm dusk graying the milk strained from a bedside table tap,

and I am slick as a gecko, greasy from my hair that is asleep outside of my body, clothes sticky like laundered linen, skin starched like malted taffy.

My tastebuds dilate like swiss, and my mouth sifts your palm for salt with a thirst I haven’t been taught, and you see me as an apparition or something less obtrusive, depending on the color I paint you.

Later I put my feet in your shoes, clay in a satin kiln, and I thank you without reason but with lots of teeth.

We sit in the cacophony, backs straight as popsicle sticks, vertebrae interchanged in checkers, apple green and menthol blue, while something falls in to be retrieved.

You staple the wound closed, and I choke on nothing.

50

51

Above: Mei Mei Johnson, acrylic

Right: Lucy Dahl, watercolor

52

Tenzin Sivukpa, oil on canvas

NOT EVEN THE MOON CAN CURE US

Erika Prasthofer

We wait for moonlight’s spill across the sky until my father’s wistful eye descends to his mind, skipping rocks over a lie, for savage waters never make amends.

My sister flops into the dampened grass. We hold a faint glance, me awestruck: in shock of her eased stance and strands of lengthy glass that refract approaching stars, flock by flock.

I sit slightly secluded from the rest, as my demeanor’s one that strains in shame of my nature, a withdrawn sort of zest that no one had the time to cure for, tame.

My journal in my hand, I start to drift as each of us disregard the moon’s lift.

53

IN THE POCKET OF COUNTY MAYO

Gabriella Miranda

In your car we are alight, sun-drunken and splintered in auburn. We burn through the five senses with an audible pulse, the crackle our chosen currency.

We can sever the island into palm-sized pieces as we go, chewing without swallowing while we siphon the taste of saltwater from its laden earth in languid and inhuman swallows.

I show you how I’ve grown to tell time with my knuckles, hoarding the clock face tree trunks, embalmed cliffs, and molten syrup streams we pass in my joints, the reservoir of tendon leaden and residual.

You say most only know this feeling when it’s taken intravenously, when it can still be vulpine and sinuous, a vine left to saturate until overgrown.

If I listen to you for too long, my few selves misplace their connective tissue, and the network annuls into two open faces.

But I listen for the same reason I catch myself drinking more water— to give edges, pigment, body, bite to the shape I hold vaulted and skeletal,

even when you seethe to soften its outline, the leather of your palm bone chafing in its warmth, hungry to fuse two halves together and call it whole.

54

Right: Omar Alsolaiman, photography

I like that your hands —and by some association, you— know how to do this, misusing their curvature to make food from flame.

But the pulmonary valve will remember to clean itself again, the muscle no longer holding the right sort of memory, and your dialect will forget how it sounds next to my own, a lapse in heartbeat, a slip of the tongue.

The road goes stagnant, and the headlights think before deflating while you imbue through the cavity of the car door. I watch through the rearview mirror as your smoke seduces the air like silk.

Would night have made this more palatable, taken away the taste?

55

LORELEI

Nadia Scharfstein

A stomp on the doormat tells me you’re home; you don’t need to ring the doorbell. It’s the key in the potted parched succulent, the subtle sweetness of last night’s shampoo like citrus and aloe scintillating in your palm.

But you are always stubborn, and I am always guilty, like how I feel when you ask for a cup of water and I say get it yourself. Leave your glasses on the flower nightstand beneath the pink lamp’s shade, under the debris of your fatigue.

You are Poppy’s second Lorelei to float over the Rhine and sink your golden comb into refined ringlets I can never touch. They fall over, dead like massacred bullets in your freckled shoulders, bloodless and amber with open mouths and minds.

Somehow I can still hear you laughing on the phone when your bedroom is next door and you are 5000 miles away. But you grew impatient of childhood, succumbed to adolescence where I know you don’t belong.

All I asked for was a small fork for big hands, iron hair, but they turned it curly like yours. Now my hip’s pink and carved, no middle fingers canvassed, left away from Portugal like I’ve forgotten but I haven’t.

56

Right: Nadia Scharfstein, graphite

57

IN PLACE OF DUAL CITIZENSHIP

Layla Hijjawi

I am in a cold place standing in the concrete rush of downtown Chicago and this cold place was once the place of my people a place where their roots thrust through sidewalk cracking stabilizing but it was not the first place of my people

where buildings shed crystal blue and don stained glass amber with the advent of Midwestern dusk I feel the warmth of a grapefruit-tinted sun cresting over rolling hills and golden domes painting a rocky landscape scattered with olive trees laden with waxy leaves and bulbous fruit my mouth floods craving tasting silky bitterness of rich oil pressed by the palms of infinite streams of women with my nose the acidity of lemonade purchased from State Street with my mother plays understudy to the tang of Levantine soil tread for generations under the boots of my people

I know in the swing of saxophone swelling across Michigan Avenue the echo of a belting call to prayer cuts through the heavy silence of the late-night air in Nablus in Jaffa

I wipe the invisible grime of the L train from my palm a gift to capture even the illusion of earth crumbling in my grasp while straining my ear to catch the lilting prayer carried away by Mediterranean winds and the screech of CTA railroad tracks that knit a metropolitan tapestry

58

but I consider that the only homeland I will know is the one spun from the tongue of my father my aunts in a futile attempt to recreate what has been lost before it was had in living rooms across suburban Illinois a smattering of sand from Lake Michigan and worn shells collected from the shores of Jaffa decades ago are all I have held that you have too and what I grasp remains the same thousands of miles divorced from where they came from as I am

your buildings that scrape precipitation from the atmosphere will be crushed by this unshakeable burden you hold Chicago caught in the limbo of the new and the mirror of the has-been three generations is all it takes to split the earth the sea the definition of homeland

59

Center: Eli Borgenicht, photography

LESS OR MORE

Katerina Mantas

Why do we wonder why he likes us?

Did he choose you on Love Island ?

Is he chasing you like a dog?

Or are you the dog chasing him, running in circles?

Do I have my tail in my mouth, lost and found, buried or borrowed? Make a straight face. Don’t laugh as he speaks, reading Girl in Pieces , my Mikey or Riley. Tell me what you’re thinking. Blurt your middle name. Dance in the middle of the restaurant. Why do we like ourselves?

Why does he like me?

Tell me your thoughts.

Is my hair in my face?

Does your back hurt some days, a fairy flying drifting away from hands reaching in wings caught in clouds, struggling, not wanting to fade away?

Growing isn’t as easy as it seems: see Tinkerbell caught in the vines, Puss in Boots with no boots, lost but I’m not sure if found, Jill running to help Jack. Where is that damn goose?

Are we sure we are both searching for golden eggs?

Or am I a dog circling around as you wave?

60

61

photography

Logan Fang,

PRENATAL

Gabriella Miranda

I dream of you the way some pray, compulsively and without meaning. Your avian features make you feel breakable in a porcelain sense, my square-cut teeth haranguing your gums, a deep static laugh barreling out of your cavernous lungs, skin like gelatin kissing your complexion. Some nights I hold you on my palm, others on my shoulder, and your body ripples to fold in on itself with every sob of hunger or exhaustion. Astringent, seafoam eyes that aren’t mine cement themselves into your cherub cheeks. Somewhere, a solar system mourns its moon; it dissolved in dustings of freckled auburn beneath your hairline and across your cordate chin. You hold yourself taut with a wonder that seeks to saturate the pallid and unmoved. I see how the colors I paint for you on canvases of skin and sky stimulate your brain to fear and love all living things in equal measure. Your stare is glacial in its vacancy, penetrative and arresting; sculpt me in what will soon be your hands, leaving only a plaster cast of what I’ve looked like before you. Tufts of hazelnut-colored hair seethe from your scalp, thinned to a fray. I count your eyelashes the way the widowed count years, as if I know I’ve missed one but don’t want to remember where. Soon my voice warms the air, and you swat at it in balled, fleshy fists. You are an alien I will only know

in fractals of myself, but before you leave for the night, I ask you to keep the babies who will one day be my company. Warn them of my earthly, impending love; I hope they look and laugh as you do.

62

watercolor

Right: Lucy Dahl,

63

III

64

Ming Lee, oil on canvas

“Suffering is a ticket stub. You are your own flashlight. Pain is just glitter in the mind.”

65

—Dean Young

HOSPITAL FOR THE NEUROLOGICALLY IMPAIRED

Quinn Yeates

my favorite miss cuts my hair with safety scissors so the strands bend before they split. my bangs lie jagged, and my neck itches.

nicholas helps the miss push my swing. it has poles instead of chains, so i rock back and forth, always three feet from the bar.

more poles make a metal footrest so no one’s legs flap about until they snap. my legs walk; it’s my head that doesn’t work right. i still rest my feet.

when the rust-wind lifts my bad bowl cut away from my face, when nicholas smiles a little at the creaking, the bandage over his eye crinkling, when the poles steady me still up high, i try to touch god like mama wished i had, but i didn’t, so she had to send me away. god doesn’t reach back. my shirt is a girl’s, and the swing is a rocking chair, and i wonder what it feels like, to swing on chains instead of bars, to thin k right, to understand why i’m here and why it makes me sad even though it has swings and someone to push me.

66 Right:

Paradise, photography

Brock

67

EXCERPT FROM “ORDER IN DISORDER”

Caelum van Ispelen

Let us consider a system of three objects. First: my mother’s blue Honda CRV with a velocity of 40 miles per hour (~17.8 meters per second) in the direction east. Second: an intersection with a green light along the east-west axis. Third: four teenagers waltzing oblivious in their sedan at the eastbound left turn.

The three-object-Earth system contains a substantial quantity of kinetic energy in the motion of the CRV relative to the pavement. The car’s continued movement seems inexorable. It has a substantial mass and to stop it, to terminate that path bound home, would require a prodigious force. That is why when you step foot inside one of these inefficient, extraordinary vehicles, you think you know with all certainty where it will bring you. You do not like to realize that you have surrendered your body in all its vulnerabilities to the foolishness of others.

The 17-year-old in the driver’s seat of the sedan has one or more problems—maybe he’s drunk; maybe he’s let his friends distract him; perhaps he’s in a real hurry to arrive at some dubious event. Whatever the case, there is little chance that he considers the CRV as more than another dunce blocking his path to teenage glory. He might see its headlights approaching from the left, might ignore them as he forgets the definition of the term “unprotected left turn,” might laugh with his friends as he turns the steering wheel, might feel a final urge to brake before the music cuts off, the headlights go out, the windshields shatter into aquamarine, the airbag slams back his face, and he realizes he screwed up.

The situation in the CRV tells another

story. It contains my mother, driving; me in the back, four, licking a vanilla ice cream cone; and my infant sibling to my right, sucking a pacifier. My mother is a good driver, but even a perfect driver cannot defy physics or others’ idiocy. Unprotected left turn means two families lie unprotected—not just the fool’s. I am too infatuated with the consumption of sugar to hear my mother curse or see her wrists apply desperate torque to the steering wheel. It is only when the world skips a step around me—when the windshield flashes from clear to white; when the car stops rumbling; when some vast elliptical blue bag has appeared in front of the dashboard—that I go in for another lick and realize my ice cream is missing. It has experienced inertia and is splattered over the front of the car.

My sibling giggles beside me, begging to “do it again.” I ask what has happened. A car accident, my mother says. Seriously, I ask? She gives no reply.

At some later point, I am standing outside in the intersection. Caring drivers have pulled over to come help. A mother and her two preschoolers matter to them. The four teenagers do not. A police officer asks if anything hurts. I say my chin does. A man with an eye patch tells me a car accident is no big deal, that he lost his eye that way. I cannot recall any of their faces.

Right: Mei Mei Johnson, multimedia 68

69

BLOCKS

Ruby Jeschke

I haven’t been seeing time as linear. My days stack together like Jenga blocks one after the other, smooth and unbothered, a pale polished wood.

I’ve woken up at five three days in a row now. Stepping out of my hammock, I can’t remember falling asleep.

My therapist gave me a book on anger. It said, “we may hold relationships in place as if our life depends on it.” While my days pile up, swirling, I stagnate and wonder which relationship holds me in place.

My friends say, “you haven’t been around lately.” I am here, right here, I shout. I turn my head and they’ve moved on to the next thing. I’m both caught up and behind again.

We’re in the coffee shop, somewhat working on homework. The art on the wall reaches toward me. I pull away my hand.

I roll a cigarette with my coffee, watching the paper wrap around the tobacco. I see myself go around and around. Tangled with the leaves, I turn to ash.

I’m in my car, driving home at 10 p.m. The blurry street lights fall behind me. It’s snowing and I think, finally everyone else can only see ten feet in front of them too.

But it stops. Still, I cannot see. The blocks pile up again.

70 Sophie Baker, multimedia

71

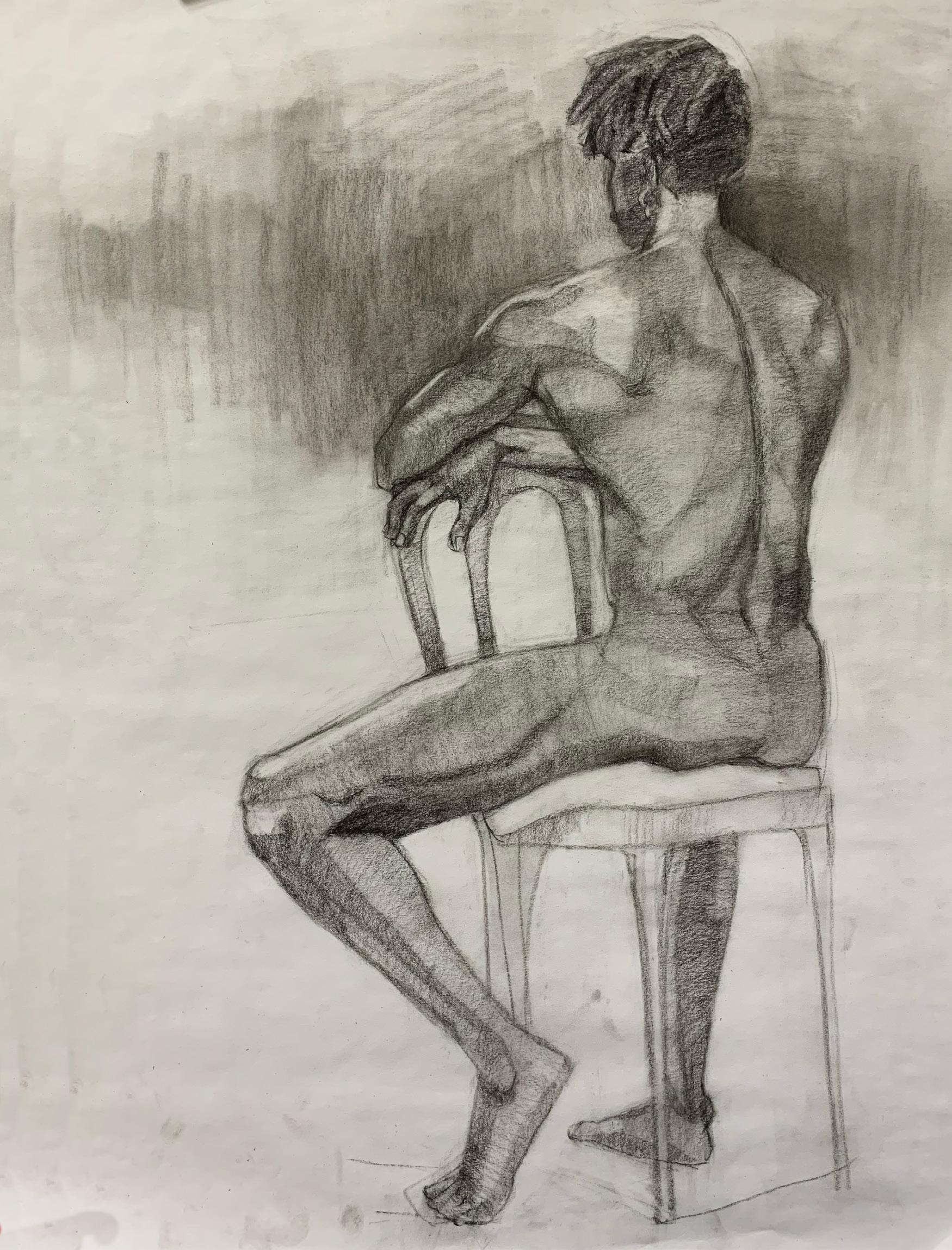

charcoal 72

Maddi

Stufflebeam,

Bea Wall, charcoal 73

74

VIRTUAL INQUISITION

Sophie Baker

Before we start: a quick disclaimer. I am a good person. I am a good person who was in the wrong place at the wrong time doing the wrong thing. But I am a good person. I promise, pinky swear, cross my heart and hope to die—the whole shebang.

Now, to begin: One second I was behind bars (falsely accused of course; you know how foul the criminal justice system is in this country), the next I was free, miraculously returned to the real world with not a second of transition. I didn’t question it, hesitant to exhaust my newfound luck, anxious to start this new life. I looked around. It appeared that I was on Main Street in the city of my youth, my place of residence when I was fresh out of college, pre-indictment, pre-world-falling-apart, prelife-ending.

Languishing in my freedom, I sauntered to my house. This is where I encountered the first issue. My door was locked, the spare key that I normally tucked under the doormat nowhere to be found. Peering through the window, I noticed a pair of heavyset boots in the entryway that weren’t mine, a foreign black trench coat on the hanger, and a sage green knapsack slung on an unfamiliar bench. This was my home. I was sure of it. So why was this other wretched person intruding on my space, my property? I couldn’t allow it. I sat on the stoop, intending to confront the interloper upon their return. Hours later, they still hadn’t materialized. My eyes drooped shut, the initial rush of adrenaline having worn off. I imagine it would be quite strange to the common passerby to find someone strewn over the stoop of such an elegant house, but my exhaustion couldn’t be abated any longer. And

anyway, how could I trespass somewhere that belonged to me?

When I awoke, I found myself, quite remarkably, inside the house—the entryway to be precise. It appeared my luck was never ending. I half expected a rainbow to bless the sky, a pot of gold stationed at the end where it met the ground. Everything seemed rather ordinary.

My own worn converse were tucked neatly under my copper entryway bench. My bomber jacket had replaced the trench coat on the hook. Only the sage green knapsack remained (I had to admit that I liked the color). I had no recollection of entering the house. I chose to believe that it was simply the universe working in my favor, a star shooting through the cosmos for me and me alone.

I slept well that night, wilting under the dark pull of Hypnos.

It appeared I had developed the habit of somnambulation—sleepwalking—while in jail. That morning, I found myself in the living room, a disposable coffee cup from the local café firmly clasped in my hand. I had no recollection of leaving my house, let alone venturing into the world. I vaguely hoped my entranced self had remembered to pay, but thought nothing of it. I’m a good person remember?

My stomach growled. It appeared I hadn’t thought to get a bite to eat. Luckily, the fridge and pantry were replete with enough food to last days or even weeks—enough time to get settled, find a job. Or so I, quite naively, thought. It briefly occurred to me that I may be stealing from whoever had taken up residence here. If anything, I consoled myself, they were stealing from me. You see, I owned this house,

75

Left: Mei Mei Johnson, acrylic

and everything in it. How could I steal something that belonged to me?

I ate well that day, savoring the explosive flavor of substantive food that I hadn’t experienced in years.

This way of life persisted for several months. When I exhausted my original food stores, they replenished, like Prometheus’s immortal liver. The electrical bill came, and within days, the money to pay it had been pushed in an unmarked envelope through the mail slot by an anonymous and charitable donor. My luck appeared to be never-ending, a waterfall that never ceased heaping life sustaining water onto the shores below.

One night, upon attempting to fall asleep, I found myself in the dream world as I hadn’t in months. This particular dream was of the realistic sort, authentic enough to trick even the most experienced dreamer into believing its guise of truth. I wasn’t experienced in the dream world and found myself quite susceptible to its deception.

The doorbell rang, a resounding gong that invaded all corners of my house. I crept downstairs, expecting yet another intruder. An unassuming young girl stood on the doorstep, hand raised as if to knock against the hardwood.

The door creaked as it opened. “How can I help you?” I asked.

“Hi,” she replied, a tremor in her voice. “I’m looking for Ms. Jules.”

“I’m afraid you have the wrong house.” I moved to shut the door.

“No, I’m certain this is it. She’s been tutoring me here for a while.”

A lie crept to my tongue. “Oh, Ms Jules, you must mean Jules Rabenstein, I remember now. She just moved out.”

“That can’t be right. She would have told me.” The curiosity of children is truly the

bane of my existence.

I cocked my head to the side. “She did. I own this house.”

“That can’t be right,” she repeated, voice rising as the tremor returned in force.

“Why don’t you come inside and we can figure out what to do over a nice cup of hot chocolate?”

She hesitated. “My mom told me not to talk to strangers.”

“Well, you’ve already broken that rule, haven’t you?”

Her head bobbed up and down. I extended my hand to her, palm up. “I promise I won’t bite.”

Her hand inched out until it fit, snug in mine. I drew her into the house.

Once Alba was settled onto the couch, sipping on the promised cup of hot cocoa, I returned upstairs and began to pace back and forth until I could feel my heels wearing into the bohemian rug. I couldn’t let her leave and tell her parents about the strange woman who had answered the door at sweet Ms. Jules house. I also didn’t know what to do about her. It was quite the conundrum.

So back and forth and back and forth I went. In the back of my mind, I could feel some animalistic power creeping over me, completely out of my control. I became an innocent bystander in my own body, the well meaning angel that we all know is powerless perched on the shoulder adjacent to the devil. I watched as the legs pivoted and began to move downstairs. I watched an arm stretch out, and a kitchen knife was pulled from the magnetic strip on the wall. I watched as the legs again began to move, entering the living room. I watched as the arm again extended to drag Alba off the couch, out the backdoor and into the alleyway. I watched as a knife was

76

held to her throat, as the color drained from her face, as the mug she had been holding on to for dear life shattered on the concrete.

I watched as a man rounded the corner, watched his features come into view, watched the police badge on his chest winking in the sunlight.

And then I watched no longer. I was behind bars once more, staring lifelessly at the headset that I held in my hands as they told me, in no uncertain terms, that that was a test, an attempt at incorporation into a “real” (code for virtual) world. And I, in no uncertain terms, had failed. Except that wasn’t really me, was it?

77

78

charcoal

Claire Wang,

GHOST

I sit in his closet, and my pants pick up the dust on the carpet. The scent of old aftershave mixes with the cold from the window, and I can hear the rushing of a busy street through the thin walls. On the floor are five pairs of shoes tossed about, worn and empty. Lonely cufflinks sit on the dresser next to a lived-in plastic container of small trinkets: a thimble, a rusted bullet, a glass heart, a dog figurine, each one hollow now. A blue box labeled wedding dress sits up high. There’s a binder tucked between two shelves with unintelligible cursive in the margins—an early copy of a posthumous book. There’s a green-tinted photograph of two parents I never met, wool socks under the bed and a forgotten Häagen-Dazs ice cream lid left in the corner. A red horseman on a Ralph Lauren polo hat hangs from the chair, waiting only to be picked up by me.

IN GRIEF

I’m reminded of the phrase

If it’s not about love

Then it’s not about God

And now I’m not sure

I feel God here

I hide behind white flowers and black

Dresses and Jesus’s fractured

Face in stained glass windows

I avoid the red cylindrical thing

That holds my grandfather

Thinking funerals are for the living

Jesus makes my heart rejoice

I sing feeling the rhythm

Of the words, not sure if what I say

Really has any meaning

But the music coaxes tears

I wonder how I can find strength when God

Must be grieving too

Winston Hoffman

79

ANONYMITY

Nadia Scharfstein

I see in infrared, in black and heat, in burns from trauma too numb to hold in my hand. My life sinks like a reflection of the sun, one that sets east and escapes by noon.

The moon is a blackened cork to block my view, to thrust the shoreline inward during high tide. I hide behind wires knowing they can see me, knowing I’ve trapped their pupils in my orbit.

Still, I hope my legacy lies in anonymity, that I am forgotten for triviality. But how can I wear a mask in a crowd when the world can recognize me, but I can’t?

Sew back up my skin, debride the burns, hide my vulnerability with cautery and callus, and pretend all is well. I hope you can’t see my smile shake, my wide eyes fall in regret.

You should know by now I want to be alone, watching my beetle-eating trees and dripping icicles, my sisters leaving and father making dinner, my mom loading skis into the Thule.

You should also know I lied because you’re reading this now, leaving a trace of myself that I can’t bury.

80

81

Alsolaiman, photography

Omar

Regan Hodson, charcoal 82

Sarah Carlebach, charcoal 83

84 Iman Ellahie, ceramics

A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE TO BECOMING A FOSSIL

Sophie Baker

Step 1: die.

Oh the ways to accomplish such a seemingly insurmountable task: a knife pierces your skin, a bullet takes lodge in your abdomen, an illness decimates half the population. Perhaps some specificity is needed?

Consider city lights, blinding lights, night lights, blinded by hounding cars and contentious cyclists and pedestrians ambling down Michigan Avenue. The city pulses, usurping the nectar of the earth, buildings stretching high, higher and higher, reaching toward the heavens.

Step 2: get buried—fast.

the neverending dark peppered with the occasional star. The city rests and rests and rests, waiting for the sun to rise, shedding its glorious light over the lake of heavenly blue, waiting to be exposed.

Step 4: wait to be exposed. I am a city lying dormant in the dead of night with only the light of the cosmos keeping watch. The insomniacs lie awake, or maybe we stalk the streets, restless, as our internal clocks tick and tick and tick, contemplating the questions of the universe.

And here, you seem to imply some agency: am I not but a body, decaying, molding, disintegrating? Or am I a phantom, somehow still of this world? Maybe in the infinite possibilities one can conjure, there is an afterlife and I am a soul floating through the heavens, or would it be hell?

I see lights bouncing off still water, a carnival of fear and hope manifesting in a lighted ferris wheel, mounted by ant-like people directing smaller rectangles of light out into the great abyss that they call a city to capture yet more light.

Step 3: soak in groundwater for a long, long time. Insert other possible method of death: A changing climate.

Ground water may have been in ample supply long, long ago in a galaxy far, far away. But to be honest, how much longer do we truly have?

Farther in the city, lights begin to wink out as curtains drop, traffic quiets, and the city rests. Now the lights of the cosmos rule,

85

SPECTRAL ILLNESS

Caelum van Ispelen

In a fond time of simplicity we swung under the maple tree and plucked buds the way a pigeon might, tentative, stripping two or three flaked spears from bark they might have grown on had she not dropped the tree that winter.

She thought she did it in secret, a method she learned from the liquid specter feasting inside her brain. I was peering through half-closed blinds. It didn’t shock us that the maple fell the same way we lost the grapevines and the strangled aspen and also our cohesion. The memory holds a blandness, a film of seawater regret shielding the nerves.

But the specter’s drouge tainted some words for us, like lead and asbestos and mind and mother. These sounds signaled departure, and we heard them through black glass as our tongues danced to avoid their touch to find other words, ones we wouldn’t remember.

Sometimes we choked and nobody noticed. Sometimes we sought to blame, to jab a leg as if it would restore the golden glow. It never worked, since the specter sprouted from neither us nor her nor any deity we might place fault on. We splotched blame too.

It never entered our minds that maybe if the world were just so different—one mouse fewer here, one sauntering tick not found, a bridge never slept under, a blackened chimney collapsing—then she might not have fallen down.

86 Right: Iman Ellahie, acrylic

87

“As for me, I am a watercolor. I wash off.”

IV 88

—Anne Sexton

Right: Sophie Zheng, charcoal

89

CATCHING SUN

Quinn Yeates

Scientists call us sea devils, as if God has any rusted hand in this. Only empty’s greed to hold yawed the ark so deep. Skulls swam with light pitched oily. But maybe we are devils for our lure, our lethal light—spines spear through scales and bend, heavy with luminescence, preying on rapture. I wonder if they see light at the end.

To each other, we’re lighthouses. Come near; show me light outside myself. Males die after mating, and their corpses cling dear, —small and dark, like sunspots, like we’ve ever touched sky.

The pressure’s so great here I think if I ever break surface, I’ll grow till oceans fracture.

90

Right: Sophie Zheng, colored pencil

91

COMMON DIVINITY

Mattie Sullivan

Mattie Sullivan

Gentle wings sit in immense tar pits, pulled and forced to enter another side, emerging crippled and desaturated, grabbed by cranes and placed onto belts, mechanically

tearing them into pieces of stiff gray fabric, losing life and most meaning, dipped in vats of color, never replacing what was, creating stiff templates and pieces

for generations to come with sewn-on wings, black pebble eyes, a spiny tail of false feathers stuffed with plastic beans, waste from others now wasting away life, fulfilling a simple, dull purpose, a gift of mere immorality from winged beings above.

They are now shot up cannons and tubes, passing through the dense tar but this time as something new, something sickeningly infinite, entering a finite realm, placed on shelves staring out at the wingless world.

92 Sophie Zheng, digital

A stifled pulse radiates from a crack in the bookshelves. She peers between and sets her eyes on a deep amber glow, and there she is, staring dead in the eyes of a phoenix, so beastly yet so quaint that it pulls her in. She flies

across the room, much like the beast did. She reaches for the phoenix, and it’s cool to the touch, yet her body begins to ignite. Welts rise from the skin. Everything begins to smelt, soon bursting into flames, encapsulating the universe.

So she plucks it from the shelf like a pinfeather from a bird, leaving a deep pit for something new to rest between the iridescent mermaid doll and unicorn decor. She prances to the cashier: all this work worth $11.99.

Now it’s home, finally fulfilling its menial purpose, placed between a porcelain kraken and new mermaid doll, taking in pin after pin, slicing through fabric, poked, plied, and prodded, and now it’s complete:

A Deluxe, Amber, Phoenix-Shaped Pincushion For All Your Pincushion Needs.

93

94

Madeleine Bateman, oil on canvas

Mei Mei Johnson, multimedia 95

PHANTOM LIMBS

Quinn Yeates

I see myself in tangles in glass; I feel my shade, calcified phantom-limbs.

If I look at myself at once, as one, even once, blooming haunt-bright, will the shade stay?

My son’s sewn into the stride of another, stitch-snapping, Bacchus—“loud one” to my hushed many.

His name is Dionysus, god

of where he went without me, but in his vines and he-shes, I echo Entire.

96

Right: Ruby Jeschke, graphite

Below: Lucy Dahl, watercolor

97

ŚŪNYATĀ

Mattie Sullivan

Elements collide, and we begin to form, creating microscopic compounds left abandoned— floating in abyssal plasma,

wound to cells and flesh sewn into fabric, weaved by both time and space, then stitched into place.

Soon we are greeted by our goddess—floating into the womb and wrapping us around her fingers like twine. We move from the spool in her grasp, trimmed in thousands of manors, all dictating our fates.

Extensive braids emerge from her scalp while threads fall to the floor underneath her, falling out of turn.

98 Lucy Dahl, watercolor

She turns to weave our threads into her hair, gently braiding us with flora and fauna near the top of her scalp.

As we move with our goddess, we too will begin to fray and one day fall to the floor with our ancestors. But for now we are intertwined with the threads of life, unknowing, unseeing, and in the beginning of creation.

We begin in the womb, walls woven by our goddess, imprints marking her flesh, outlining our history, valleys carved into skin, flesh ripped towards the bone, basins to carry her tears, to dump into the rivers below.

She carries us within her pores and wraps us with her hair. She sculpts our limbs with nails and chews the clay between her teeth.

She tells us of Śūnyatā.

“Śūnyatā” has the meaning of “womb.” Every being in the world is created from the womb,

the place in which we used to rest, the place in which we were conjured.

Śūnyatā is our safety, our fullness— our emptiness.

Once we leave her flesh, we flock like a herd of herdsmen, searching for their ox, wandering through dense vines, seeking underneath the thin flesh of petals and leaves.

We find ourselves resting between slashes in dirt between the ripped seams tailored to our goddess. We tear her stitches and seep between the threads, trickle down flesh and drip towards the abyss.

Here we begin—while falling towards the earth; here we begin—face to face with the void; here we begin—to recoil the thread.

99

Anaïs Bray, graphite

PHAËTHON

Lucy Dahl

While the world freezes and burns, love falls from the heavens. His father can only watch as his most prized possession plummets down through the clouds, the icy hot sky unsavable. No god can stop the fates snipping the scissors, the end of it all. As the thread thuds to the ground, time freezes, the sky boils, lakes dry up, deserts feeze, solid smoke billows, and ash fills the air, scraping his delicate lungs. His soft hair now blackened and burned, everything is on fire, and smoke rises off him like a meteor; he isn’t a meteor. The people are running. The people are crying. The butcher holds his daughter, whimpering as he illuminates the sky, shining. He won’t come home. His bed lies empty. His mother sits worried, silence echoing. He won’t come back to the chariot. It failed. No, he failed, arms outstretched with fear, and the gap grows bigger, and the earth grows closer.

100 Right: Omar Alsolaiman, photography

101

THE MOTH

Mattie Sullivan

She is the bringer of death, the ancestors’ messenger, marked with a skull, the fate who spins the holy thread. Her sheers slice the spindle, the messenger of the gods but not of their blessings.

She brings no winged sandals with Her message, only fore and hindwings laced to Her thorax, adorned with peach fuzz and implants of go ld, our divine watcher with pale eyespots orbited by ancestors.

She changes Her color when the messenger requires: an ancestor calls. She must be a milky white, but caution in trust calls for an earthy shade. Called to the divine, running towards light, an open flame calls her.

She flutters forward. Her fern-like antenna on the edge of death must bring Her message, so the light is diminished: someone wil l die, certain of fate the second She enters. She must snip the spindle.

She is the bringer of death. She engulfs every aspect. She is rebirth, brings fate to your doorstep, dressed in faded ink and yellowing paper, brings death and life and every moment between: She is our Charon.

She rows the gold-crested boat through stalactites and ancient crystals, brings us home and soon will pull us from our rest—She is the carrier, strains and stretches every tendon in Her wings, all to connect the circuit.

She works with and within the cycle: from an egg to larva to encapsulation, inches closer with each incarnation. Saturn’s rings will warp t o greet Her, the bringer of death, the divine messenger, marked by our souls.

—First published in Roanoke Review (2023)

102 Right: Jay Lutton, watercolor

103

SPARAGMOS AS RENAMING

Layla Hijjawi

Layla Hijjawi

In certain tellings of the myth of the Sparagmos, Zagreus was born to Persephone and Zeus, who was in the form of a snake . He was intended to be the successor to Zeus’s throne. However, in a jealous rage, Hera had the Titans lure and tear Zagreus to pieces, consuming his body and his heart. Zeus brutally punished th e Titans and was able to retrieve and consume Zagreus’s heart which allowed for the reconception of Zagreus in Semele, one of Zeus’s other wives, and, ultimately, Zagreus’s rebirth as Dionysus.

Child, you were born of snake teeth and lightning, galaxies spanning across your palm lines. Your father had the throne of the gods carved from the shape of your mother’s womb. You bled cosmos and red, sweet wine under your skin. Born into greatness, you were too easy to trick, to lead to primordial tongues and teeth, ivory whetted for your bone. The sky wept in roiling floods for your flesh! Highest of the gods , rendered twice heartless. Paternal rage strikes, ruptures its cradle.

104

Left: Aurelie Wallis, acrylic

Right: Claire Wang, acrylic

105

106

Zakrie Smith, acrylic

DIVINE ZOOCHORY

Quinn Yeates

Sian’s all fine-boned sin, her devilry so delicate crusaders cry when they crush it, when it rusts their sanctified iron heels.

Her sin’s a seed. It clings to saints’ soles. It tags along on pilgrimages, chapel to temple, is tread into church wood so old the trees didn’t know to groan when they fell, wood so old it weeps to remember what seeds feel like. Eternity trumps memory. Eternity trumps most things. God counts on it. Sian counts seeds.

She follows prophets’ paths closer than any disciple. Kneeling over their footprints, she whispers of stars named after sinners, of people served by an agnostic’s open heart.

Saints’ footprints become flower beds. The blooms taint their steps with transgression, debase them as trespassers on holy ground.

She pries seeds out of ears, dredges them from teeth’s caves, drains them from veins. She was twelve when she first plucked a daylily from her own nape; at fifteen, her brother cuts his thumb and the wound spills sunflower seeds.

Bent over altars and then flowers and then disciples’ steps, Sian plucks blooms from within herself and plants them in believers’ wakes. Every fallen saint nourishes Eden within themselves. Eden wasn’t made to be alone—it was made for Eve, for Adam, for Lilith. Sinners cannot live in Eden, and so Eden lives in them. Burrs, proboscidea louisianica, children promised with family: seeds don’t care if they make it to Heaven; they’re just holding onto someone. Please, flower, plant me near you.

107

V

108 Aurelie Wallis, ink

109

MY MATERIALISM

Sophie Baker

Pull up a search engine and type “define hoarder.” Read “a person who hoards things.” Feel briefly annoyed that they define the word with itself. Click “hoards.” Read “amass (money or valued objects) and hide or store away.” Think “that might be me,” yet excuse yourself—there are most definitely people who have a much larger hoarding problem than you.

My room is a breeding ground for things I no longer and will never need. Books spring from bending shelves, and loose papers litter my desk. Organized chaos, I like to claim. Perhaps I put more emphasis on the “organized” than it deserves.

Regardless, my curated room of refuse stands in stark contrast to the pristine sterility of the surrounding house. It drives my parents mad. I’m not sure what they despise more, the mess or my inability to do anything about it. I doubt they consider why I so desperately cling to these seemingly irrelevant objects, why I can’t get rid of a short story I wrote in the seventh grade, a ticket from a movie my friends and I had seen last year, a rock I found nestled on the shore of the lake.

I worry, sometimes, that if I toss out the story, I will never again feel the thrill of putting pen to paper on a warm spring day surrounded by the chatter of birds. That I will never again laugh-cry as I did while my best friend danced around the now empty theater as the credits rolled on and on. That I will never again bask in the sunshine during the summer, careless and free, crisp waves lapping at my feet, the remnants of a popsicle

coating my fingers.

I have a tendency, as you might have gleaned, to associate the memories I have with things, material objects only to be looked at with a sense of hopeless longing on those many nights spent tossing from side to side, side to side, mind churning over something I did or did not say, did or did not do, will or will not have to do. When my mind becomes so unbearable—inhabitable, if you will—the only reprieve is to be found in memory, and the only memory to be found in debris.

110

111

Iman Ellahie, acrylic

RIO CORTEZ

Rio Cortez is the New York Times bestselling author of picture books The ABCs of Black History (Workman, 2020) and The River Is My Sea (S&S, 2024). Her debut poetry collection, Golden Ax, was longlisted for the 2022 National Book Award for Poetry and the Pen America Open Book Award and was a finalist for Poetry Society of America’s Norma Farber First Book Award. It is available now from Penguin Books. Born and raised in Salt Lake City, she now lives, writes, and works in Harlem.

Cortez came to Salt Lake City as part of our community celebration of the life and legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. on January 12, 2023. She held a poetry reading and taught a class at Rowland Hall, and she generously continued the conversation with us virtually on April 19. We discussed her works, her past writing experiences and tips, and her thoughts on writing poetry and prose in relation to race.

INTERVIEW

112

In poetry, you can evoke something that resonates with other people in a way that feels more closely attuned with the way that we feel in real life. That’s why poetry is attractive to me as a place to explore identity.

What is your take on AI in terms of writing poetry and creating art?

For poetry, AI feels like a non-threatening development right now because generative AI hasn’t gotten to a place where it could naturally or instinctually create poetry in the way that we’re getting it from living poets. However, the concept of AI taking the place of images that artists are creating is really destructive and scary, especially when you’re thinking about the Black image, for example. Even certain companies are using AI-generated Black models to model clothing, and I think about what that means in terms of the erasure and invisibility that exists in art in certain industries.

Thinking back to Golden Ax, why have you chosen poetry as the medium to navigate important issues like race? What opportunities does the form of poetry offer when talking about those issues?

For me, poetry felt like a place where you could write without full articulation. There are certain things that I think that I experienced, especially when I was younger and living in Utah, that I could not fully articulate but I knew were there. I still don’t know that there’s language for everything, and so poetry is a perfect place for things like that. When you’re writing in prose, there is a pressure, even though it’s not formally decreed, to have a complete thought or synthesis to what you’re saying. In poetry, you can evoke something that resonates with other people in a way that feels more closely attuned with the way that we feel in real life. That’s why poetry is attractive to me as a place to explore identity. I’m really interested in the idea of knowing and the different kinds of knowing that we have,

and there’s a layer there that can be expressed better in poetry than other forms of art.

How do you ground abstract imagery and ideas so the sentiments still resonate with someone?

I try to use specific imagery. We need that to help the flow of the piece and in grounding ideas so they can be familiar with other people. But sometimes it’s not the concrete image or transferability that resonates with the reader, but truth, and truth is the currency. If there’s legible truth in a line, that’s the line that resonates with people the most, generally speaking. Sometimes people connect over the beauty and lyricism and music of a line, and that’s different, but when truth is there, delivered through a concrete image or abstract thought, the ideas will resonate with the reader.

113

Sometimes it’s not the concrete image or transferability that resonates with the reader, but truth, and truth is the currency.