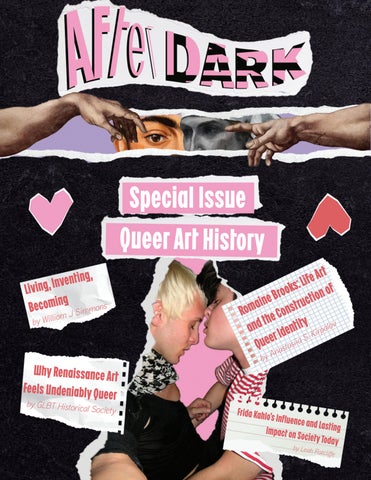

Why Renaissance Art Feels Undeniably Queer by GLBT Historical Society

Romaine Brooks: Life, Art, and the Construction of Queer Identity by Anastasiia S. Kirpalov

Frida Kahlo’s Influence and Lasting Impact on Society Today by Leah Ratcliffe

Living, Inventing, Becoming by William J Simmons Why Renaissance Art Feels Undeniably Queer by GLBT Historical Society

Romaine Brooks: Life, Art, and the Construction of Queer Identity by Anastasiia S. Kirpalov

Living, Inventing, Becoming by William J Simmons

Frida Kahlo’s Influence and Lasting Impact on Society Today by Leah Ratcliffe

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 10 22 28 32 36 18 40 03

04

Contents

Table of

The American-born painter Romaine Brooks was almost forgotten for decades after her death. Now the world is finally ready to understand the underrated queer artist. The name of Romaine Brooks, the early twentieth-century portraitist, is not one that comes to mind instantly when talking about women artists. However, she is remarkable both as an artist and as a person. Brooks showed a deep psychological understanding of her subjects. Her works also serve as important sources helping us understand the construction of female queer identity in the early twentieth century.

The American-born painter Romaine Brooks was almost forgotten for decades after her death. Now the world is finally ready to understand the underrated queer artist.

invested in spiritualism and occultism, hoping to cure her son by all means, while completely neglecting her daughter. When Romaine was seven, her mother Ella abandoned her in New York City, leaving her without any financial support.

invested in spiritualism and occultism, hoping to cure her son by all means, while completely neglecting her daughter. When Romaine was seven, her mother Ella abandoned her in New York City, leaving her without any financial support.

When she was older Brooks moved to Paris and tried to make a living as a cabaret singer. After Paris, she moved to Rome in order to study art, struggling to make ends meet. She was the only female student in the whole group. Brooks endured continuous harassment from her male peers and the situation was so severe that she had to flee to Capri. She lived in extreme poverty in her tiny studio in an abandoned church.

The name of Romaine Brooks, the early twentieth-century portraitist, is not one that comes to mind instantly when talking about women artists. However, she is remarkable both as an artist and as a person. Brooks showed a deep psychological understanding of her subjects. Her works also serve as important sources helping us understand the construction of female queer identity in the early twentieth century.

Romaine Brooks: No Pleasant Memories

Romaine Brooks: No Pleasant Memories

Born in Rome to a rich American family, Romaine Goddard’s life could have been a carefree paradise. The reality was much harsher though. Her father left the family soon after Romaine’s birth, leaving his child with an abusive mother and a mentally ill older brother. Her mother was heavily

Born in Rome to a rich American family, Romaine Goddard’s life could have been a carefree paradise. The reality was much harsher though. Her father left the family soon after Romaine’s birth, leaving his child with an abusive mother and a mentally ill older brother. Her mother was heavily

It all changed in 1901, when her ill brother and mother died within less than a year of each other, leaving an enormous inheritance to Romaine. From that moment on, she became truly free. She married a scholar named John Brooks, taking his last name. The reasons for this marriage are unclear, at least from Romaine’s side, since she was never attracted to the opposite sex, and neither was John who soon after their separation moved in with the novelist Edward Benson. Even after the separation, he still received a yearly allowance from his ex-wife. Some say that the main reason for their separation was not the lack of mutual attraction, but rather John’s ridiculous spending habits, which

annoyed Romaine since her inheritance was the couple’s primary source of income.

annoyed Romaine since her inheritance was the couple’s primary source of income.

The Moment of Triumph

When she was older Brooks moved to Paris and tried to make a living as a cabaret singer. After Paris, she moved to Rome in order to study art, struggling to make ends meet. She was the only female student in the whole group. Brooks endured continuous harassment from her male peers and the situation was so severe that she had to flee to Capri. She lived in extreme poverty in her tiny studio in an abandoned church.

The Moment of Triumph

This was the moment when Brooks, a triumphant heiress of a huge fortune, finally moved to Paris and found herself right in the middle of elite circles with Parisian locals and foreigners. In particular, she found herself in the queer elite circles that were a safe space for her. She started painting full-time, not having to worry about her finances anymore.

This was the moment when Brooks, a triumphant heiress of a huge fortune, finally moved to Paris and found herself right in the middle of elite circles with Parisian locals and foreigners. In particular, she found herself in the queer elite circles that were a safe space for her. She started painting full-time, not having to worry about her finances anymore.

It all changed in 1901, when her ill brother and mother died within less than a year of each other, leaving an enormous inheritance to Romaine. From that moment on, she became truly free. She married a scholar named John Brooks, taking his last name. The reasons for this marriage are unclear, at least from Romaine’s side, since she was never attracted to the opposite sex, and neither was John who soon after their separation moved in with the novelist Edward Benson. Even after the separation, he still received a yearly allowance from his ex-wife. Some say that the main reason for their separation was not the lack of mutual attraction, but rather John’s ridiculous spending habits, which

Brooks’ portraits show women from the elite circles, many of them being her lovers and close friends. In a way, her oeuvre functions as a deep study of the lesbian identity of her time. The women in Brooks’ circle were financially independent, with their family fortunes allowing them to live their lives in the ways they desired. In fact, it was complete financial independence that allowed Romaine Brooks to create and exhibit her art without depending on the traditional system consisting of Salons and patrons. She never had to fight for her place in exhibitions or galleries since she could afford to organize a one-woman show in the prestigious DurandRouel gallery all by herself in 1910. Earning money was also never her priority. She rarely sold any of her works, donating most of her works to the Smithsonian museum not long

Brooks’ portraits show women from the elite circles, many of them being her lovers and close friends. In a way, her oeuvre functions as a deep study of the lesbian identity of her time. The women in Brooks’ circle were financially independent, with their family fortunes allowing them to live their lives in the ways they desired. In fact, it was complete financial independence that allowed Romaine Brooks to create and exhibit her art without depending on the traditional system consisting of Salons and patrons. She never had to fight for her place in exhibitions or galleries since she could afford to organize a one-woman show in the prestigious DurandRouel gallery all by herself in 1910. Earning money was also never her priority. She rarely sold any of her works, donating most of her works to the Smithsonian museum not long

Le Trajet by Romaine Brooks, 1911, via The Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington

4 After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

4 After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

Le Trajet by Romaine Brooks, 1911, via The Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington

before her death.

UNDENIABLY QUEER

Discover how homoerticism became high art

If you’ve wandered through a museum’s Renaissance collection, eyed off the number of writhing, muscular male bodies and thought that they felt rather homoerotic, you wouldn’t be alone. In fact, there’s an excellent explanation for why even the most sacred religious figures have been depicted in a way that to our modern eyes feels more gay bathhouse than Sunday service. Renaissance means rebirth, and it refers to an obsession with Classical Antiquity (That’s Ancient Greece and Rome) that kicked off in the 14th century in western

Europe. While in the Islamic world, the Greco-Roman influence from the Byzantine Empire continued, in West-

ern Europe a lot of Ancient Greek and Roman traditions fell out of style after the collapse of the (Western)

Roman Empire

and the ensuing middle ages. But when surviving texts from the Classical

period were rediscovered in the West, translated and circulated, Greco-Roman art, philosophy and culture underwent a major revival, and among them were the ideas of philosophers like Plato on same-sex relationships. These were were not only common and accepted in Ancient Greece, but Plato believed love between men was closer to God than its heterosexual counterpart.

The revival of Plato’s ideas can be used to explain why during the Renaissance period, depictions of sacred religious figures took a turn for the homoerotic. An excellent example of this is Saint Sebastian, the paSaint John the Baptist XIXth century

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History 4

Attic Red-Figure Kylix

tron Saint of Plague in the Catholic tradition.

During the medie-

val period, Saint Sebastian was represented as an older, bearded and not aggressively handsome man......but from the dawn of Renaissance, we see him nude, his chiseled chest full of arrows, boasting an expression that seems to walk the line between pain and ecstasy. Similarly, this depiction of John the Baptist by Renaissance icon Leonardo Da Vinci with a ‘come hither’ finger is suggestive on first look, but even more so when you

discover that the model Da Vinci used was his own male lover, Gian Giacomo Caprotti (fondly known by Da Vinci as Salaí).

The revival of Greco-Roman

thought

lead to a kind of tacit endorsement of same-sex relationships during the Renaissance, which was great news for those who were same-sex attracted. In Florence, the Italian city at the center of the Renaissance, for many a homoerotic rendition of Saint Sebastian) are all reported to have loved and had sex with men. The male gaze is so often spoken about in

reference to male artists’ “sex

between men became so prevalent “

that authorities for forced to set up just four decades in the 15th century, one of which was Leonardo Da Vinci.

Then there was

Michelangelo, another Florentine artist of the Renaissance, who is responsible for decorating the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel with nude men arranged in a similarly homoerotic fashion.

5 After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

Relationship, the photobook by Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, is both a beautiful documentation of two lovers and an important intervention into the heterosexist, homophobic landscape of art history. Spanning from 2008 through 2014, the images expand upon the artists’ presentation in the 2014 Whitney Biennial, organized by Stuart Comer, who also provides an introduction. We know Drucker and Ernst from their collaborative performances, as well as their spearheading of trans visibility with a distinctly LA flair (they lived in Ron Athey’s old house in Silver Lake—which, as Comer notes, recalls the gloriously queer Southern California world of Athey, Catherine Opie, and Vaginal Davis). Drucker and Ernst are now producers on the wildly popular Amazon series Transparent, which has perhaps led to the optimistic assumption made by the book’s back cover that “trans has never been more accepted.” While that may be true within a certain progressive subset of the American population, the fact remains that any depiction of a gendernonconforming body is an act of revolution that unsettles the biomedical

After Dark

Relationship, the photobook by Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, is both a beautiful documentation of two lovers and an important intervention into the heterosexist, homophobic landscape of art history.

Spanning from 2008 through 2014, the images expand upon the artists’ presentation in the 2014 Whitney Biennial, organized by Stuart Comer, who also provides an introduction.

We know Drucker and Ernst from their collaborative performances, as well as their spearheading of trans visibility with a distinctly LA flair (they lived in Ron Athey’s old house in Silver Lake—which, as Comer notes, recalls the gloriously queer Southern California world of Athey, Catherine Opie, and Vaginal Davis).

Drucker and Ernst are now producers on the wildly popular Amazon series Transparent, which has perhaps led to the optimistic assumption made by the book’s back cover that “trans has never been more accepted.” While that may be true within a certain progressive subset of the American population, the fact remains that any depiction of a gendernonconforming body is an act of revolution that unsettles the biomedical

“It’s not their responsibility to educate cisgender people, but it is certainly an act of generosity that they do.”

“It’s not their responsibility to educate cisgender people, but it is certainly an act of generosity that they do.”

2

2

After Dark

heterosexist patriarchy.

Zackary

Drucker and Rhys Ernst, Relationship, #33, 2008–13

“The photographer is changing, even as the photograph is being taken, and so are the subjects.”

heterosexist patriarchy.

What is even more explosive is the fact that Relationship represents two individuals who undergo their transitions simultaneously and remain together throughout the process. As Kate Bornstein mentioned at a recent conversation at the Strand bookstore in New York celebrating the release of Relationship, this is the first visual account of transtrans love. It’s hard for even self-professed “experts” of gender theory to wrap their minds around that. Even Judith Butler, the influential philosopher and gender theorist, for instance, was recently asked to grapple with the latent transphobia of her movement-creating, but often misunderstood, theories about gender performance. But Drucker and Ernst allow us to see their journey as it happens. They don’t have to explain themselves or allow us any access; it’s not their responsibility to educate cisgender people, but it is certainly an act of generosity that they do.

However, explaining is often what we expect of gender-nonconforming artists. Comer’s assertion in the foreword is a distillation of what would likely be said by anyone who has taken

“The photographer is changing, even as the photograph is being taken, and so are the subjects.”

What is even more explosive is the fact that Relationship represents two individuals who undergo their transitions simultaneously and remain together throughout the process. As Kate Bornstein mentioned at a recent conversation at the Strand bookstore in New York celebrating the release of Relationship, this is the first visual account of transtrans love. It’s hard for even self-professed “experts” of gender theory to wrap their minds around that. Even Judith Butler, the influential philosopher and gender theorist, for instance, was recently asked to grapple with the latent transphobia of her movement-creating, but often misunderstood, theories about gender performance. But Drucker and Ernst allow us to see their journey as it happens. They don’t have to explain themselves or allow us any access; it’s not their responsibility to educate cisgender people, but it is certainly an act of generosity that they do.

After Dark

However, explaining is often what we expect of gender-nonconforming artists. Comer’s assertion in the foreword is a distillation of what would likely be said by anyone who has taken

3

3

After Dark

Gender Studies 101. He describes Relationship as “a codex for how we might reconsider our families and relationships, not as fixed structures but as elastic communities capable of celebrating, rather than fearing, transformation.”

But Relationship should not be viewed merely as a lens through which cisgender readers can deconstruct their own lives. As perhaps its first priority, Relationship exists for itself and for the community that can most immediately understand it, as well as the community still to come—the queer and trans youth who are growing up in a world where trans identities are no longer consigned to invisibility. The photographs are not a rubric for a queer theory checklist. These are not images of Others that cisgender people might marvel at from a

After Dark

Gender Studies 101. He describes Relationship as “a codex for how we might reconsider our families and relationships, not as fixed structures but as elastic communities capable of celebrating, rather than fearing, transformation.”

But Relationship should not be viewed merely as a lens through which cisgender readers can deconstruct their own lives. As perhaps its first priority, Relationship exists for itself and for the community that can most immediately understand it, as well as the community still to come—the queer and trans youth who are growing up in a world where trans identities are no longer consigned to invisibility. The photographs are not a rubric for a queer theory checklist. These are not images of Others that cisgender people might marvel at from a

distance; Relationship is not a “codex.” Bornstein’s assertion that “the book takes trans a step beyond acceptance into desirability” should instead be the key takeaway. In these pages, we see the wondrous complexity of human sexuality—a physically and conceptually vast phenomenon. The beauty of trans-trans love—the gentle

distance; Relationship is not a “codex.” Bornstein’s assertion that “the book takes trans a step beyond acceptance into desirability” should instead be the key takeaway. In these pages, we see the wondrous complexity of human sexuality—a physically and conceptually vast phenomenon. The beauty of trans-trans love—the gentle

and

Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, Relationship, #44, 2008–13

caresses and lightly muscled stomachs, legs dappled with endearing hairs, supple asses, veined breasts, and narrow waists—becomes its own kind of criticality even though it doesn’t have to be. Love can simply be glamorous or horny or sleepy or, really, whatever it wants.

caresses and lightly muscled stomachs, legs dappled with endearing hairs, supple asses, veined breasts, and narrow waists—becomes its own kind of criticality even though it doesn’t have to be. Love can simply be glamorous or horny or sleepy or, really, whatever it wants.

Still, it is important that we do not lean on lofty concepts and attend to Relationship only as a photographic project. When I began looking at these images, my first instinct was to attempt to understand the historical underpinnings of the project. How do Drucker and Ernst compare to Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, and Cindy Sherman (the examples cited by the book’s cover)? Well, they don’t. All of those artists operate within the context of a normative art history that

Still, it is important that we do not lean on lofty concepts and attend to Relationship only as a photographic project. When I began looking at these images, my first instinct was to attempt to understand the historical underpinnings of the project. How do Drucker and Ernst compare to Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, and Cindy Sherman (the examples cited by the book’s cover)? Well, they don’t. All of those artists operate within the context of a normative art history that

Zackary Drucker and Relationship, 2008–13

4

Zackary Drucker

Rhys Ernst, Relationship, #35, 2008–13

Dark

Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, Relationship, #44, 2008–13

After

privileges established modes of sexuality. Sherman, Andy Warhol, and Marcel Duchamp don drag, but at their core is a reaffirmation of two fixed genders, if only ironically or as stereotype. Furthermore, although Clark and Goldin have produced important documentary images, Drucker and Ernst are not necessarily documenting; they are living. In Relationship, the term “documentary” might not even hold, given that the book is a record of two unique bodies in a state of mutual becoming. This defies the inherent fixity of the camera and

privileges established modes of sexuality. Sherman, Andy Warhol, and Marcel Duchamp don drag, but at their core is a reaffirmation of two fixed genders, if only ironically or as stereotype. Furthermore, although Clark and Goldin have produced important documentary images, Drucker and Ernst are not necessarily documenting; they are living. In Relationship, the term “documentary” might not even hold, given that the book is a record of two unique bodies in a state of mutual becoming. This defies the inherent fixity of the camera and

points to what historian Ariella Azoulay has called photography’s “civil contract”—its ability to exteriorize previously unseen social relationships and differentials of power.

points to what historian Ariella Azoulay has called photography’s “civil contract”—its ability to exteriorize previously unseen social relationships and differentials of power.

Most of the time, Drucker and Ernst are not in the picture together, but we understand a psychic relationship when a purely physical one is absent. The photographer is changing, even as the photograph is being taken, and so are the subjects, like two vines that slowly grow into each other and become unified. We come to understand the

Most of the time, Drucker and Ernst are not in the picture together, but we understand a psychic relationship when a purely physical one is absent. The photographer is changing, even as the photograph is being taken, and so are the subjects, like two vines that slowly grow into each other and become unified. We come to understand the

potential of the photograph to reveal bodies in flux but also modes of seeing in flux. This is more important, I think, than trying to find art historical precedents for Relationship, because what the book actually asks is that we rely not on outmoded visual cues and social narratives, but rather, like Drucker and Ernst, invent new ones.

potential of the photograph to reveal bodies in flux but also modes of seeing in flux. This is more important, I think, than trying to find art historical precedents for Relationship, because what the book actually asks is that we rely not on outmoded visual cues and social narratives, but rather, like Drucker and Ernst, invent new ones.

Relationship was published by Prestel in June 2016.

Relationship was published by Prestel in June 2016.

This article was originally published in Aperture Magazine.

This article was originally published in Aperture Magazine.

5 After Dark

5 After Dark

Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, Relationship, #37, 2008–13

22

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

Viva la Vida, Watermelons, 1954, Frida Kahlo

Viva la Vida, Watermelons, 1954, Frida Kahlo

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History 23

(Source: www.fridakahlo.org)

This month is Disability Pride Month, so we’re taking a look at one of the most prolific disabled women to date and her revolutionary, lasting impact on society today. From queer feminist icon to Mexican fashionista - Frida Kahlo has become a household name, and here’s why.

Frida Kahlo was born July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico, a village on the outskirts of Mexico City. 18 years later, she began painting when a nearly fatal bus accident left her unable to walk for three months. After that her health was always fragile, the accident left her with lifelong pain and medical problems which ultimately led to her death in 1954 at age 47. For three decades her work remained relatively unknown outside of Mexico until the 1983 publication of the biography written by Hayden Herrera. Following this in 2002, a Hollywood biopic was released based on that book, becoming the catalyst for her renewed international recognition. Kahlo’s work and her life soon became beacons for the feminist movement, emboldening women in any number of creative fields to have the courage to speak about the difficulties they face in their lives; equally, being a woman of mixed race who embraced her complex heritage – an openly bisexual woman too – she has also become a role model for minorities of all kinds. Inevitably, such iconic fame has spread beyond the spheres of art and politics to which she devoted her energy, to fields such as fashion, where the influence of her personal style has become something of an exotic cliché.

“My painting carries with it the message of pain.”

Frida Kahlo isn’t only celebrated for her artistic talents. She is an icon to many for many reasons. Her openness around female sexuality has inspired and impacted the LGBTQIA+ community for over a century. Her free spirit, character and modern attitudes toward sexuality have made her an icon for all in the community. As an openly queer woman in the early 20th century, having open relationships with women was seen as pretty revolutionary. Her search for love wasn’t limited to the confines of societal norms of that time. As an openly bisexual woman, she had love interests of both men and women. The two loves of her life were Diego Rivera and Josephine Baker. During her rollercoaster marriage to Diego, she had several affairs (as did he) with men and women, whilst later falling in love with Josephine in Paris once divorced. Her open queerness during her lifetime transcends into her artwork and continues to impact the world today. One of many elements in her “What I

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

What the Water Gave Me, 1938, Frida Kahlo (Source: www.fridakahlo.org)

Frida Kahlo

24

Saw in the Water,” the two female nudes in “Two Nudes in the Forest” are made the subject of the painting, in which Frida is clearly celebrating lesbian sexual love.

Her open queerness during her lifetime trancends into her artwork and continues to impact the world today.

Kahlo has undoubtedly become a huge source of inspiration and empowerment for women over the generations. From a young age, she was resilient, strong and took control of her own life. She became a feminist icon through her character, activism, and art. Her paintings were intimate, personal, included nudity and were seen as revolutionary for her time. During the feminist movement in the 70s, Kahlo was admired as an ‘icon of female creativity’. Kahlo’s life and art often reveal the continuous battle for self-determination in the life of being a woman. She forged her own identity in her paintings outside the societal norms of her time. Her transparency and frankness in her art covered themes such as pregnancy, miscarriage, politics, conception, gender roles, and sexuality. All of which were revolutionary for a woman to be broadcasting to the masses during (and even after) her lifetime. To be openly questioning her identity and the role of women in society was and still is an incredibly ground-breaking statement.

Kahlo was a renowned crossdresser, purposely wearing male attire to project a message of power and independence. This family photograph from 1926 (below) shows her dressed in all men’s clothing next to her feminine mother and sisters. Kahlo frequently used her clothing to make a nationalist political point, as well as making a statement about her own independence and rebellion from feminine norms. The famous monobrow and moustache were both real features she deliberately exaggerated in the numerous selfportraits through which she is best known. Her features were confidently unconventional. Her image remains a beacon of empowerment for all women who want to defy the narrow social constructs around the ‘perfect feminine image’.

Although Kahlo’s artwork took a few decades to become widely discovered, in her lifetime and to this day she has had an immense impact on Mexican culture. Whilst travelling the world with her husband at the time, she introduced traditional Mexican attire to the mainstream. Kahlo showed her Mexican pride by wearing Tehuana dresses which featured full skirts, flamboyant hairstyles and embroidered blouses. Kahlo fused this indigenous look with

Two Nudes in a Forest, 1939, Frida Kahlo (Source: www.fridakahlo.org)

Two Nudes in a Forest, 1939, Frida Kahlo (Source: www.fridakahlo.org)

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History 25

(Source: www.fridakahlo.org)

the more contemporary elements h was the catalyst for the Italian designer Elsa Shiaparelli’s creation “La Robe de Madame Rivera” (“Mrs. Rivera’s Dress”) based on Kahlo’s Tehuana styles. Her message of female liberation shortly became associated with the Tehuana style, and it didn’t take long for it to infiltrate the high fashion scene. The most notable designers since to have referenced Kahlo’s wardrobe have been the spring/summer collection of Jean Paul Gaultier in 1998 and most recently Valentino’s spring/summer 2015 collection.

You don’t necessarily have to research Frida Kahlo to find out about her lasting impact on society. Walk into any stationery, book, or clothes shop and see the impact for yourself. You’ll find her famous self-portrait on mugs, t-shirts or calendars. You can buy a going-out

dress heavily inspired by Mexican culture. You can get a printable Kahlo quote to stick on your wall for inspiration and empowerment. Even over fifty years after her death, she is still all around us; her legacy lives on.

The story of Frida Kahlo is a revolutionary one of a brown, disabled, queer, feminist icon. It’s a story of tragedy, adversity, triumph, and liberation. She continues to make a profound impact on the world not only from her talents but by standing firm in who she was. She reminds us that there are infinite possibilities beyond our physical limitations and liberation in our vulnerability.

Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940, Frida Kahlo

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History 26

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History 27

2

Born in Rome to a rich American family, Romaine

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

financial support.

When she was older Brooks moved to Paris and tried to make a living as a cabaret singer. After Paris, she moved to Rome in order to study art, struggling to make ends meet. She was the only female student in the whole group. Brooks endured continuous harassment from her male peers and the situation was so severe that she had to flee to Capri. She lived in extreme poverty in her tiny studio in an abandoned church.

It all changed in 1901, when her ill brother and mother died within less than a year of each other, leaving an enormous inheritance to Romaine. From

that moment on, she became truly free. She married a scholar named John Brooks, taking his last name. The reasons for this marriage are unclear, at least from Romaine’s side, since she was never attracted to the opposite sex, and neither was John who soon after their separation moved in with the novelist Edward Benson. Even after the separation, he still received a yearly allowance from his ex-wife. Some say that the main reason for their separation was not the lack of mutual attraction, but rather John’s ridiculous spending habits, which annoyed Romaine since her inheritance was the couple’s primary source of income.

The Moment of Triumph

This was the moment when Brooks, a triumphant heiress of a huge fortune, finally moved to Paris and found herself right in the middle of elite circles with Parisian locals and foreigners. In particular, she found herself in the queer elite circles that were a safe space for her. She started painting full-time, not having to worry about her finances anymore.

Brooks’ portraits show women from the elite circles, many of them being her lovers and close friends. In a way, her oeuvre functions as a deep study of the lesbian identity of her time. The women in Brooks’ circle 3

After

Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

were financially independent, with their family fortunes allowing them to live their lives in the ways they desired. In fact, it was complete financial independence that allowed Romaine Brooks to create and exhibit her art without depending on the traditional system consisting of Salons and patrons. She never had to fight for her place in exhibitions or galleries since she could afford to organize a one-woman show in the prestigious Durand-Rouel gallery all by herself in 1910. Earning money was also never her priority. She rarely sold any of her works, donating most of her works to the Smithsonian museum not long before her death.

Romaine Brooks and the Queer Identity

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the ideas surrounding queer identity absorbed new aspects and dimensions. Queer identity was no longer limited to sexual preferences only. Thanks to people like Oscar Wilde, homosexuality was accompanied by a certain lifestyle, aesthetics, and cultural preferences.

However, such a distinct shift in the mass culture concerned some people. In nineteenth-century

literature and popular culture, a typical representation of lesbians was limited to the concept of femmes damnées, the unnatural and perverse beings, tragic in their own corruption. Charles Baudelaire’s collection of poems Les Fleurs du mal was centered around such a kind of stereotypical decadent representation.

None of this can be found in the works of Romaine Brooks. The women in her portraits are not stereotypical caricatures or projections of someone else’s desires. Although some paintings seem dreamier than others, most of them are realistic and deeply psychological portraits of real people. The portraits feature a wide array of different-looking women. There’s the feminine figure of Natalie CliffordBarney, who was Brooks’ lover for fifty years, and there’s the overly masculine portrait of Una Troubridge, a British sculptor. Troubridge was also the partner of Radclyffe Hall, the author of the scandalous novel The Well of Loneliness which was published in 1928.

The portrait of Troubridge seems almost like a caricature. This was probably Brooks’ intention. Although the artist herself wore men’s suits and short hair, she

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

despised the attempts of other lesbians like Troubridge who tried to look as masculine as possible. In Brooks’ opinion, there was a fine line between breaking free from the gender conventions of the era and appropriating the attributes of the male gender. In other words, Brooks believed that queer women of her circle were not supposed to look manly, but rather go beyond the limitations of gender and male approval. The portrait of Troubridge in an awkward posture, wearing a suit and a monocle, strained the relationship between the artist and the model.

4

Queer Icon Ida Rubinstein

In 1911, Romaine Brooks found her ideal model in Ida Rubinstein. Rubinstein, a Ukrainian-born Jewish dancer, was the heiress to one of the richest families of the Russian Empire that was forcefully put in a mental asylum after a private production of Oscar Wilde’s Salome during which Rubinstein stripped completely naked. This was considered indecent and scandalous for anyone, let alone for a high-class heiress.

After escaping the mental asylum, Ida arrived in Paris for the first time in 1909. There she started

working as a dancer in the Cleopatre ballet that was produced by Sergei Diaghilev. Her slender figure rising from a sarcophagus on stage had a tremendous effect on the Parisian public, with Brooks being fascinated by Rubinstein right from the beginning. Their relationship lasted for three years and resulted in numerous portraits of Rubinstein, some of them painted years after their breakup. In fact, Ida Rubinstein was the only one who was repeatedly portrayed in Brooks’ painting. Not a single one of her other friends and lovers were given the honor of being portrayed more than once.

The images of Rubinstein generated surprising mythological connotations, elements of symbolist allegories, and surrealist dreams. Her well-known painting Le Trajet shows Rubinstein’s nude figure stretched on a wing-like white shape, contrasting the pitch darkness of the background. For Brooks, the slim androgynous figure was the absolute beauty ideal and the embodiment of queer feminine beauty. In the case of Brooks and Rubinstein, we can talk about the queer female gaze to the fullest extent. These nude portraits are erotically charged, yet they express the idealized beauty different from the normative heterosexual paradigm 5 After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

Romaine Brooks’s Fifty Years Long Union

with simple line drawings, made by Brooks during the 1930s.

Romaine Brooks died in 1970, leaving all of her works to the Smithsonian museum. Her works did not attract much attention in the following decades. However, the development of queer art history and liberalization of the art historical coming from a male viewer.

The relationship between Romaine Brooks and Ida Rubinstein lasted for three years and most likely ended on a bitter note. According to art historians, Rubinstein was so invested in this relationship she wanted to buy a farm somewhere far away in order to live there together with Brooks. However, Brooks was not interested in such a reclusive lifestyle. It is also possible that the breakup happened because Brooks fell in love with another American living in Paris, Nathalie CliffordBarney. Nathalie was as rich as Brooks. She became famous for hosting the infamous lesbian Salon. Their fifty-year-long relationship was however polyamorous.

lifestyle. The artist grew more reclusive and paranoid with age, and when Barney, already in her eighties, found herself a new lover in the wife of a Romanian ambassador, Brooks had enough. Her last years were spent in complete seclusion, with barely any contact with the outside world. She stopped painting and focused on writing her autobiography, a memoir called No Pleasant Memories which was never published. The book was illustrated 6

discourse made it possible to talk about her oeuvre without censorship and oversimplification. Another feature that made Brooks’ art so hard to discuss was the fact that she deliberately avoided joining any art movement or group.

After

3404 Queer Art

Dark: Issue

History

If you’ve wandered through a museum’s Renaissance collection, eyed off the number of writhing, muscular male bodies and thought that they felt rather homoerotic, you wouldn’t be alone.

In fact, there’s an excellent explanation for why even the most sacred religious figures have been depicted in a way that to our modern eyes feels more gay bathhouse than Sunday service. Renaissance means rebirth, and it refers to an obsession with Classical Antiquity (That’s Ancient Greece and Rome) that kicked off in the 14th century in western Europe. While in the Islamic world, the Greco-Roman influence from the Byzantine Empire continued, in Western Europe a lot of Ancient Greek and Roman traditions fell out of style after the collapse of the (Western)

Roman Empire and the ensuing middle ages. But when surviving texts from the Classical period were rediscovered in the West, translated and circulated, Greco-Roman art, philosophy and culture underwent a major revival, and among them were the ideas of philosophers like Plato on same-sex relationships. These were were not only common and accepted in Ancient Greece,

6 After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

but Plato believed love between men was closer to God than its heterosexual counterpart.

The revival of Plato’s ideas can be used to explain why during the Renaissance period, depictions of sacred religious figures took a turn for the homoerotic. An excellent example of this is Saint Sebastian, the patron Saint of Plague in the Catholic tradition.

During the medieval period,

Saint Sebastian was represented as an older, bearded and not aggressively handsome man......but from the dawn of Renaissance, we see him nude, his chiseled chest full of

arrows, boasting an expression that seems to walk the line between pain and ecstasy. Similarly, this depiction of John the Baptist by Renaissance icon Leonardo Da Vinci with a ‘come hither’ finger is suggestive on first look, but even more so when you discover that the model Da Vinci used was his own male lover, Gian Giacomo Caprotti (fondly known by Da Vinci as Salaí).

The revival of Greco-Roman thought

lead to a kind of tacit endorsement of same-sex relationships during the Renaissance, which was great news for those who were same-sex attracted. In Florence, the Italian city at the center of the Renaissance, for many a homoerotic rendition of Saint Sebastian) are all reported to have loved and had sex with men. The male gaze is so often spoken about in reference to male artists’

“sex between men became so prevalent “

that authorities for forced to set up just four decades in the 15th century, one of which was Leonardo Da Vinci. Then there was Michelangelo, another

7 After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

But when surviving texts from the Classical period were rediscovered in the West, translated and circulated, Greco-Roman art, philosophy and culture underwent a major revival, and among them were the ideas of philosophers like Plato on samesex relationships. These were were not only common and accepted in Ancient Greece, but Plato believed love between men was closer to God than its heterosexual counterpart.

The revival of Plato’s ideas can

be used to explain why during the Renaissance period, depictions of sacred religious figures took a turn for the homoerotic. An excellent example of this is Saint Sebastian, the patron Saint of Plague in the Catholic tradition. During the medieval period, Saint Sebastian was represented as an older, bearded and not aggressively handsome man... ...but from the dawn of Renaissance, we see him nude, his chiseled chest full of arrows, boasting an expression that seems to walk the line between pain and ecstasy.

Similarly, this depiction of John the Baptist by Renaissance icon Leonardo Da Vinci with a ‘come hither’ finger is suggestive on first look, but even more so when you discover that the model Da Vinci used was his own male lover, Gian Giacomo Caprotti (fondly known by Da Vinci as Salaí).

The revival of Greco-Roman thought lead to a kind of tacit endorsement of same-sex relationships during the Renaissance, which was great news for those who were same-sex attracted. In Florence, the Italian city at the center of the Renaissance, sex between men became so prevalent that authorities for forced to set up a task force to, at the very least be seen to, do something about it. The Office of the Night accused 17000

Florentine men of Sodomy over just four decades in the 15th century, one of which was Leonardo Da Vinci.

Then there was Michelangelo, another Florentine artist of the Renaissance, who is responsible for decorating the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel with nude men arranged in a similarly homoerotic fashion. If there needed to be more evidence to the inherent queerness in some of these paintings, we don’t need to look much further than the artists who painted them. Artists like Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Guido Reni (who was responsible for many a homoerotic rendition of Saint Sebastian) are all reported to have loved and had sex with men.

8 After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

9 After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

Living, Inventing, Becoming

By William J. Simmons

Relationship, the photobook by Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, is both a beautiful documentation of two lovers and an important intervention into the heterosexist, homophobic landscape of art history. Spanning from 2008 through 2014, the images expand upon the artists’ presentation in the 2014 Whitney Biennial, organized by Stuart Comer, who also provides an introduction. We know Drucker and Ernst from their collaborative performances, as well as their spearheading of trans visibility with a distinctly LA flair (they lived in Ron Athey’s old house in Silver Lake—which, as Comer notes, recalls the gloriously queer Southern California world of Athey, Catherine Opie, and Vaginal Davis). Drucker and Ernst are now producers on the wildly popular Amazon series Transparent, which has perhaps led to the optimistic assumption made by the book’s back cover that “trans has never been more accepted.” While that may be true within a certain progressive subset of the American population, the fact remains that any depiction of a gender-nonconforming body is an act of revolution that unsettles the biomedical heterosexist patriarchy.

What is even more explosive is the fact that Relationship represents two individuals who undergo their transitions simultaneously and remain together throughout the process. As Kate Bornstein mentioned at a recent conversation at the Strand bookstore in New York celebrating the release of Relationship, this is the first visual account of trans-trans love. It’s hard for even self-professed “experts” of gender theory to wrap their minds around that. Even Judith Butler, the influential philosopher and gender theorist, for instance, was recently asked to grapple with the latent

Zackary Drucker

Rhys Ernst, Relationship, #23 (The Longest Day of the Year), 2011

and

2 After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

transphobia of her movementcreating, but often misunderstood, theories about gender performance. But Drucker and Ernst allow us to see their journey as it happens. They don’t have to explain themselves or allow us any access; it’s not their responsibility to educate cisgender people, but it is certainly an act of generosity that they do.

However, explaining is often what we expect of gendernonconforming artists. Comer’s assertion in the foreword is a distillation of what would likely be said by anyone who has taken Gender Studies 101. He describes Relationship as “a codex for how we might reconsider our families and relationships, not as fixed structures but as elastic communities capable of celebrating, rather than fearing,

transformation.” But Relationship should not be viewed merely as a lens through which cisgender readers can deconstruct their own lives. As perhaps its first priority, Relationship exists for itself and for the community that can most immediately understand it, as well as the community still to come—the queer and trans youth who are growing up in a world where trans identities are no longer consigned to invisibility. The photographs are not a rubric for a queer theory checklist. These are not images of Others that cisgender people might marvel at from a distance; Relationship is not a “codex.” Bornstein’s assertion that “the book takes trans a step beyond acceptance into desirability” should instead be the key takeaway. In these pages, we see the wondrous complexity of human sexuality—a physically and conceptually vast phenomenon. The beauty of trans-trans love—the gentle caresses and lightly muscled stomachs, legs dappled with endearing hairs, supple asses, veined breasts, and narrow waists—becomes its own kind of criticality even though it doesn’t have to be. Love can simply be glamorous or horny or sleepy or, really, whatever it wants.

Still, it is important that we do not lean on lofty concepts and attend to Relationship only as a photographic project. When I began looking at these images, my first instinct was to attempt to understand the historical underpinnings of the project. How do Drucker and Ernst compare to Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, and Cindy Sherman (the examples cited by the book’s cover)? Well,

Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, Relationship, #37, 2008–13

3 After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

they don’t. All of those artists operate within the context of a normative art history that privileges established modes of sexuality. Sherman, Andy Warhol, and Marcel Duchamp don drag, but at their core is a reaffirmation of two fixed genders, if only ironically or as stereotype. Furthermore, although Clark and Goldin have produced important documentary images, Drucker and Ernst are not necessarily documenting; they are living. In Relationship, the term “documentary” might not even hold, given that the book is a record of two unique bodies in a state of mutual becoming. This defies the inherent fixity of the camera and points to what historian Ariella Azoulay has called photography’s

“civil contract”—its ability to exteriorize previously unseen social relationships and differentials of power.

Most of the time, Drucker and Ernst are not in the picture together, but we understand a psychic relationship when a purely physical one is absent. The photographer is changing, even as the photograph is being taken, and so are the subjects, like two vines that slowly grow into each other and become unified. We come to understand the potential of the photograph to reveal bodies in flux but also modes of seeing in flux. This is more important, I think, than trying

to find art historical precedents for Relationship, because what the book actually asks is that we rely not on outmoded visual cues and social narratives, but rather, like Drucker and Ernst, invent new ones.

Relationship was published by Prestel in June 2016.

This article was originally published in Aperture Magazine.

Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, Relationship, #35, 2008–13

Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, Relationship, #35, 2008–13

4 After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, Relationship, #44 (Flawless Through the Mirror) and Relationship, #33, 2008–13 5

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

(Source: www.fridakahlo.org)

Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940, Frida Kahlo

Leah Ratcliffe

Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940, Frida Kahlo

Leah Ratcliffe

40

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History

talents. She is an icon to many for many reasons. Her openness around female sexuality has inspired and impacted the LGBTQIA+ community for over a century. Her free spirit, character and modern attitudes toward sexuality have made her an icon for all in the community. As an openly queer woman in the early 20th century, having open relationships with women was seen as pretty revolutionary. As an openly bisexual woman, she had love interests of both men and women. The two loves of her life were Diego Rivera and Josephine Baker. During her rollercoaster marriage to Diego, she had several affairs (as did he) with men and women, whilst later falling in love with Josephine in Paris once divorced. Her open queerness during her lifetime transcends into her artwork and continues to impact the world today. One of many elements in her “What I Saw in the Water, the two female nudes in “Two Nudes in the Forest” are made the subject of the painting, in which Frida is clearly celebrating lesbian sexual love.

www.FridaKahlo.org)

Her open queerness during her lifetime trancends into her artwork and continues to impact the world today.

Kahlo has undoubtedly become a huge source of inspiration and empowerment for women over the generations. From a young age, she was resilient, strong and took control of her own life. She became a feminist icon through her character, activism, and art. Her paintings were intimate, personal, included nudity and were seen as revolutionary for her time. During the feminist movement in the 70s, Kahlo was admired as an ‘icon of female creativity’. Kahlo’s life and art often reveal the continuous battle for self-determination in the life of being a woman. She forged her own identity in her paintings outside the societal norms of her time. Her transparency and frankness in her art covered themes such as pregnancy, miscarriage, politics, conception, gender roles, and sexuality. All of which were revolutionary for a woman to be broadcasting to the masses during (and even after) her lifetime. To be openly questioning her identity and the role of women in society was and still is an incredibly ground-breaking statement.

Kahlo was a renowned crossdresser, purposely wearing male attire to project a message of power and independence. This family photograph from 1926 (below) shows her dressed in all men’s clothing next to her feminine mother and sisters. Kahlo frequently used her clothing to make a nationalist political point, as well as making a statement about her own independence and rebellion from feminine norms. The famous monobrow and

What the Water Gave Me, 1938, Frida Kahlo (Source:

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History 41

moustache were both real features she deliberately exaggerated in the numerous self-portraits through which she is best known. Her features were confidently unconventional. Her image remains a beacon of empowerment for all women who want to defy the narrow social constructs around the ‘perfect feminine image’.

Although Kahlo’s artwork took a few decades to become widely discovered, in her lifetime and to this day she has had an immense impact on Mexican culture. Whilst travelling the world with her husband at the time, she introduced traditional Mexican attire to the mainstream. Kahlo showed her Mexican pride by wearing Tehuana dresses which featured full skirts, flamboyant hairstyles and embroidered blouses. Kahlo fused this indigenous look with the more contemporary elements of her wardrobe, showcasing her cross-

Two Nudes in the Forest, 1939, Frida Kahlo (Source www.fridakahlo.org)

cultural identity and honouring Mexican women of all generations. The message of her 1937 painting “My Nurse and I” is a clear

celebration of the continuity of the nurturing Mexican culture from that ancient past (mother with the face of a pre-Columbian deity) to her own creative present.

She was resilient, strong and took control of her own life

Whilst travelling continents in this attire, she gained a lot of attention from locals who’d stop and admire her amazing outfits. Kahlo is said to have been one of the biggest reasons Mexican costume became internationally recognised. From Europe to the USA, people were in awe of her presence and persona. Everywhere she went, she celebrated her culture with her choice of clothing, and it didn’t take long for this style to catch on internationally. Throughout the 1930s and 40s, her image made the most predominant waves in the mainstream fashion world. Kahlo’s style became synonymous with Mexican culture. In October 1937 she was featured in that month’s edition of Vogue, which was the catalyst for the Italian designer Elsa Shiaparelli’s creation “La Robe de Madame Rivera” (“Mrs. Rivera’s Dress”) based on Kahlo’s Tehuana styles. Her message of female liberation shortly became associated with the Tehuana style, and it didn’t take long for it to infiltrate the high fashion scene. The most notable designers since to have referenced Kahlo’s wardrobe have been the spring/ summer collection of Jean Paul Gaultier in 1998 and most recently Valentino’s spring/summer 2015 collection.

You don’t necessarily have to research Frida Kahlo to find out about her lasting impact on society. Walk into any stationery, book, or

clothes shop and see the impact for yourself. You’ll find her famous self-portrait on mugs, t-shirts or calendars. You can buy a going-out dress heavily inspired by Mexican culture. You can get a printable Kahlo quote to stick on your wall for inspiration and empowerment.

Even over fifty years after her death, she is still all around us; her legacy lives on.

Her image remains a beacon of empowerment for all women

The story of Frida Kahlo is a revolutionary one of a brown, disabled, queer, feminist icon. It’s a story of tragedy, adversity, triumph, and liberation. She continues to make a profound impact on the world not only from her talents but by standing firm in who she was. She reminds us that there are infinite possibilities beyond our physical limitations and liberation in our vulnerability.

My Nurse and I, 1937, Frida Kahlo (Source www.fridakahlo.org)

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History 42

After Dark: Issue 3404 Queer Art History 43

CAPTION

Viva la Vida, Watermelons, 1954, Frida Kahlo

Viva la Vida, Watermelons, 1954, Frida Kahlo

Two Nudes in a Forest, 1939, Frida Kahlo (Source: www.fridakahlo.org)

Two Nudes in a Forest, 1939, Frida Kahlo (Source: www.fridakahlo.org)

Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940, Frida Kahlo

Leah Ratcliffe

Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940, Frida Kahlo

Leah Ratcliffe