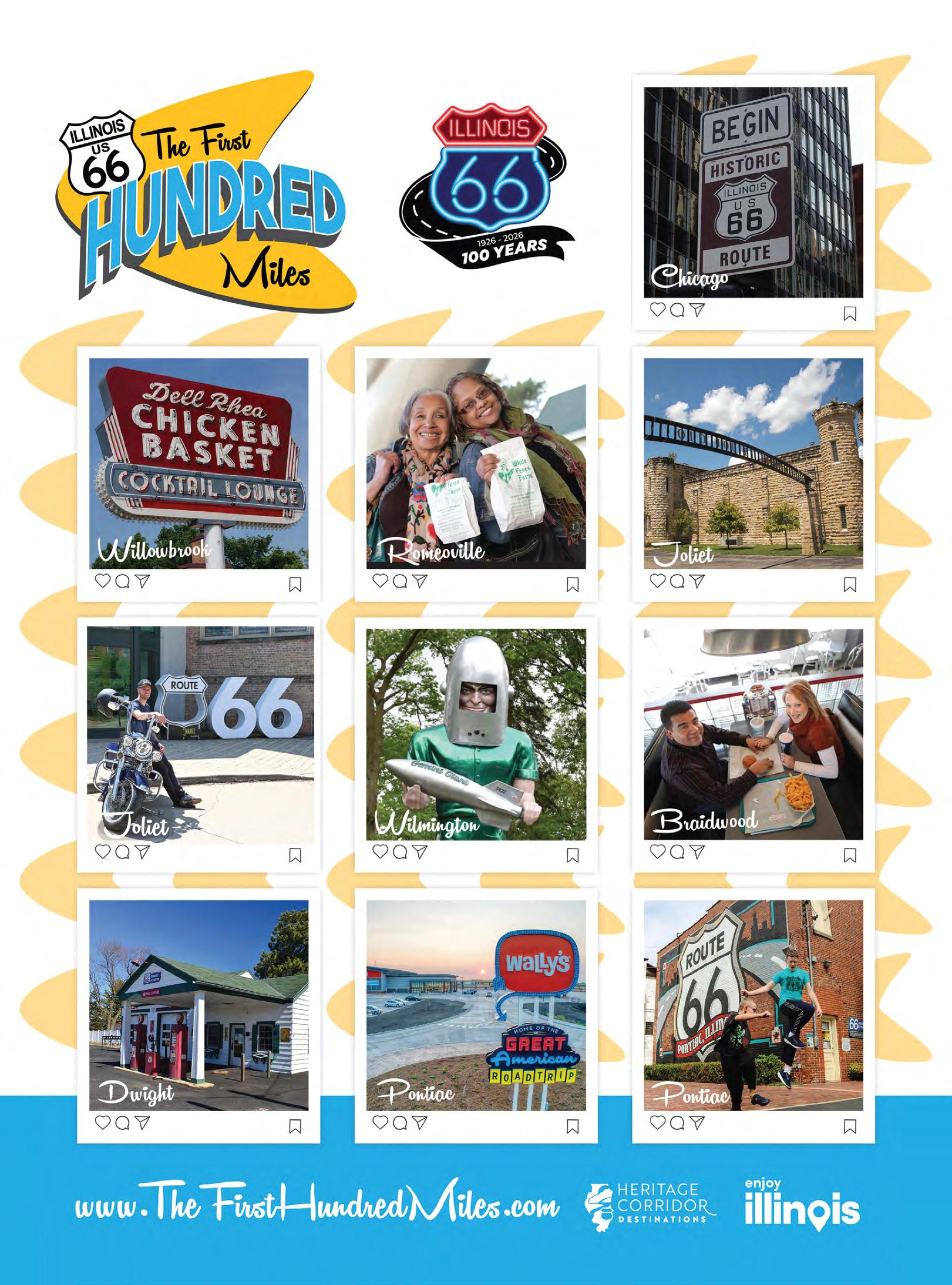

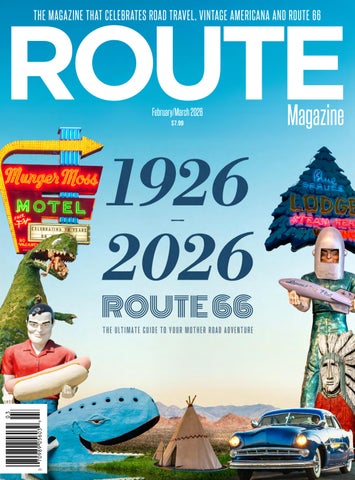

February/March 2026

February/March 2026

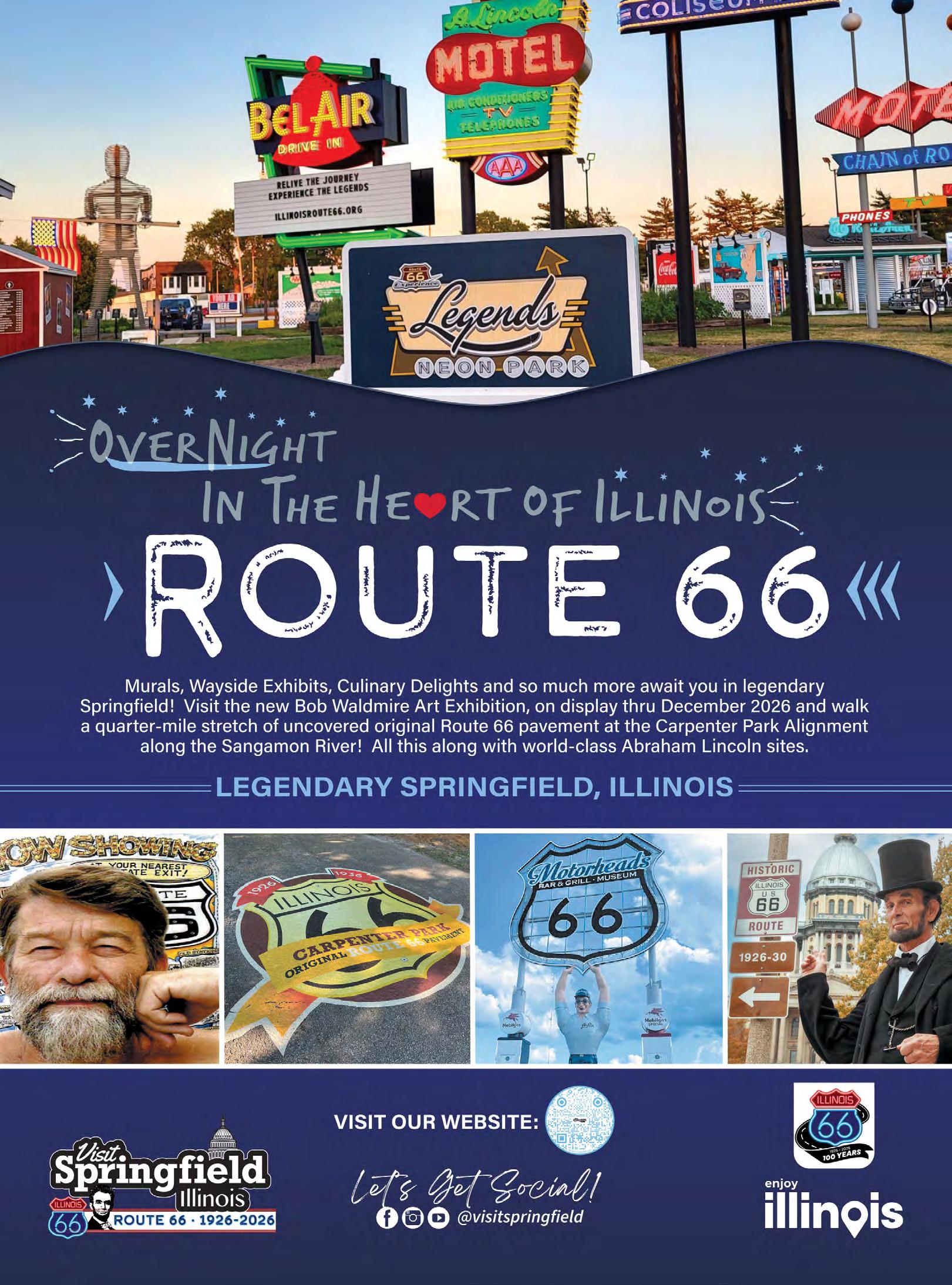

Plan your next visit to Springfield, Missouri and celebrate 100 years of America’s most iconic highway right in its birthplace. Explore classic diners, historic landmarks, and hidden gems that keep the spirit of the road alive. Here in the City of the Ozarks, it’s all about making it your own.

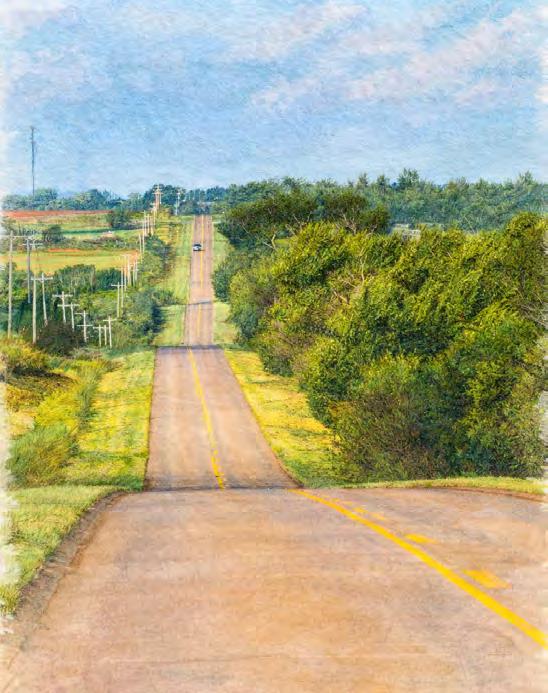

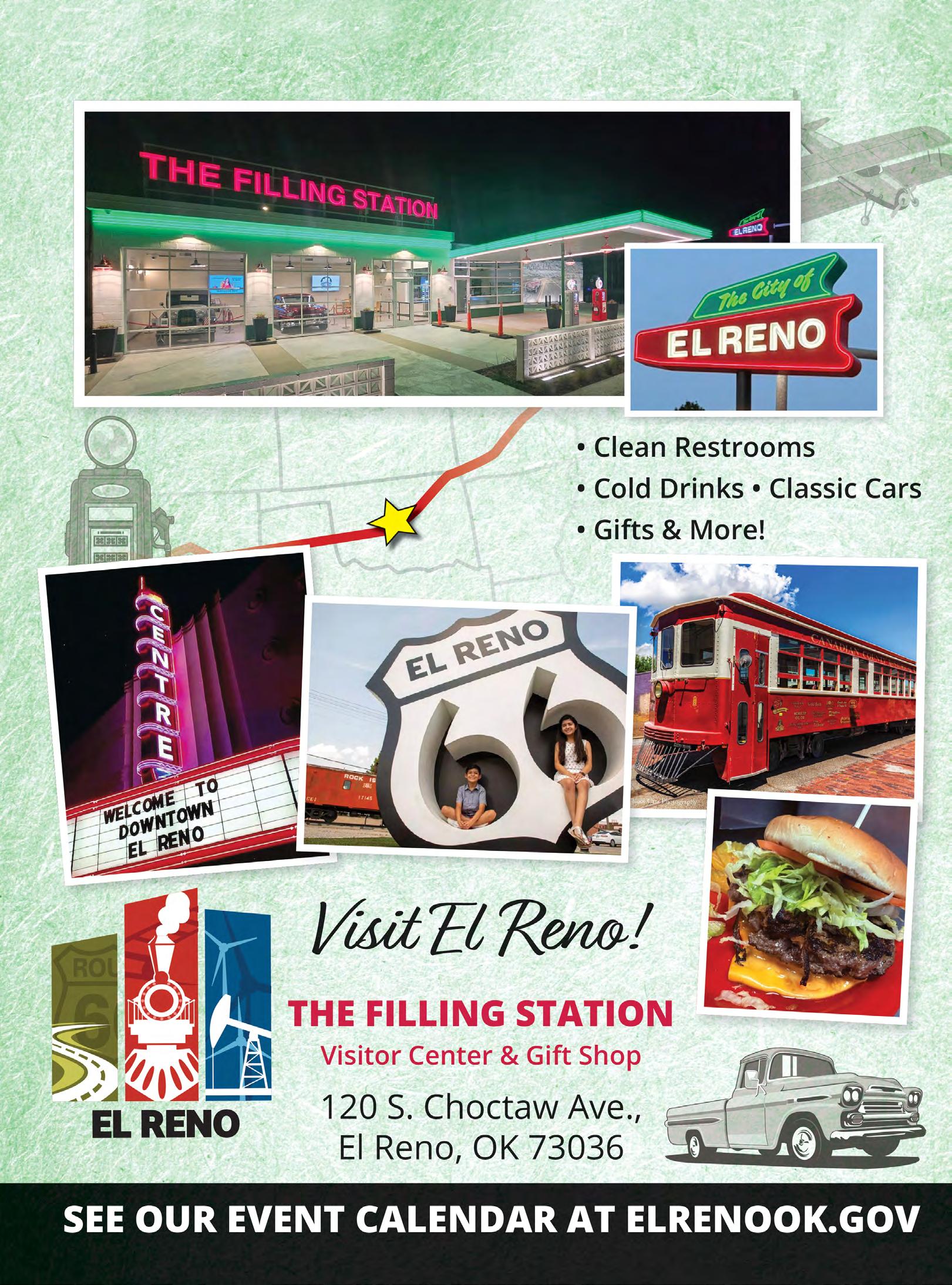

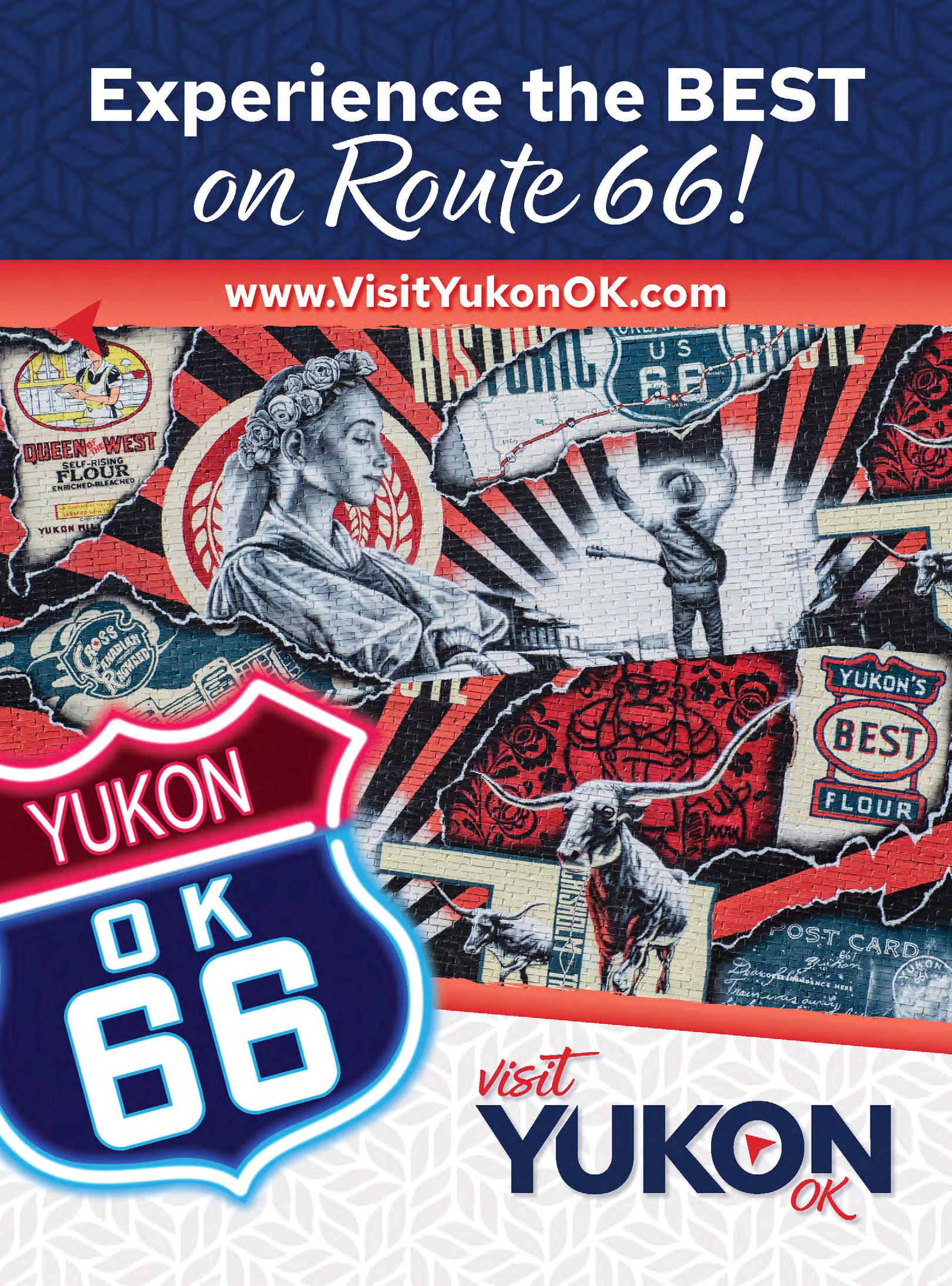

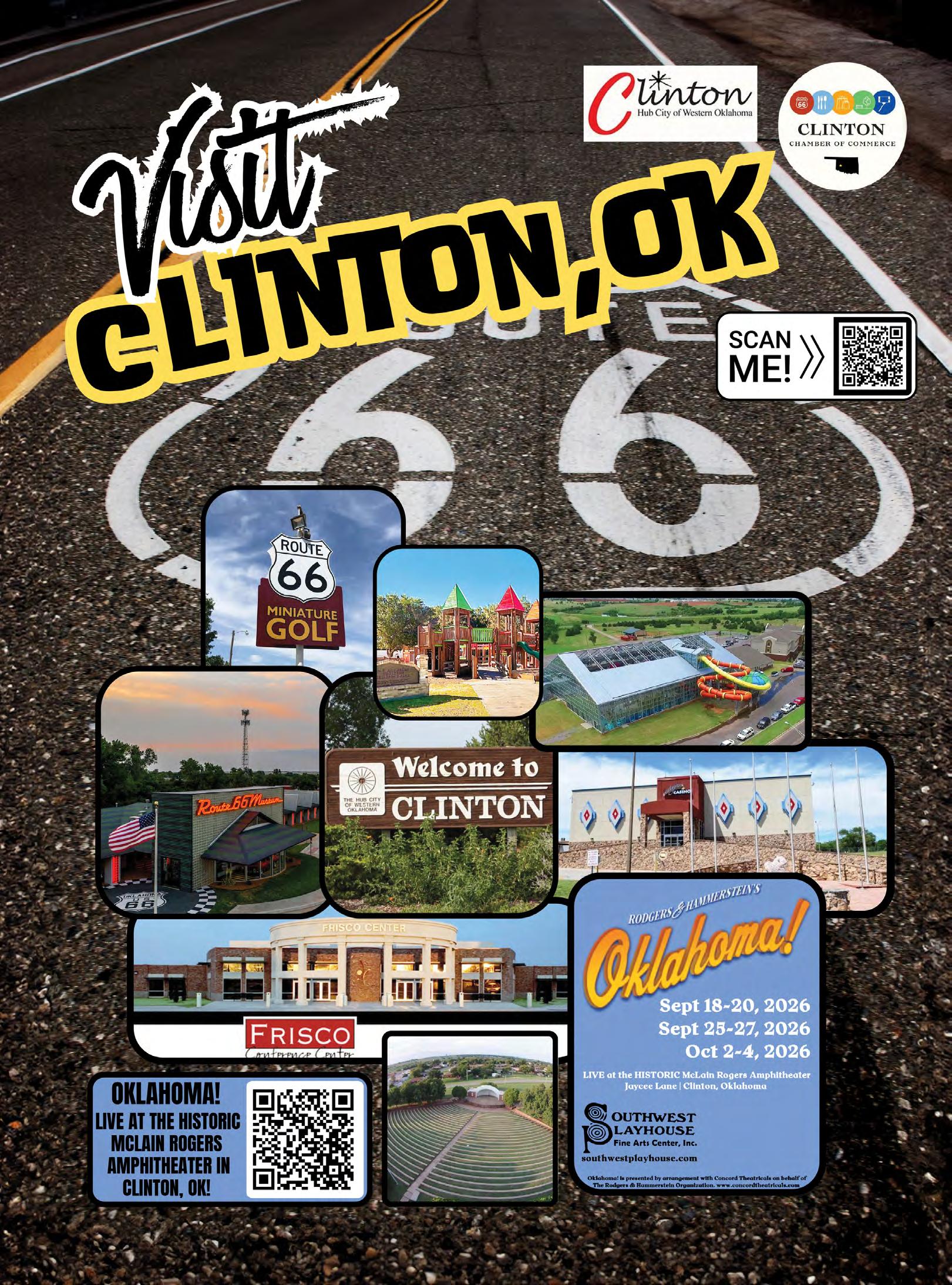

Follow the road to discover iconic stops, hidden gems and unforgettable moments along Oklahoma’s Route 66.

Remember when driving was a joy? Back when you drove to escape, to feel that rush of freedom, or to connect with the person across that bucket seat from you. You’d share a smile when that one song came on; the stereo would get turned up, and windows would get rolled down. You can recapture that moment—or find it for the first time—on Route 66. Feel that horsepowered heartbeat that you’ve been missing in America’s Heartland. Take the Scenic Route: VisitLebanonMo.org

No other highway in U.S. history is more celebrated than Route 66. Also known as the Mother Road, this storied byway once connected Chicago to Los Angeles and travelers to America. Experience for yourself 33 miles of a twisting, winding, and nostalgic trip through time in Pulaski County, MO.

For more information, directions, and driving tour information, visit pulaskicountyusa.com.

Celebrate 100 years of road tripping in the only place in America where the Mother Road of Route 66 meets the scenic beauty of the Great River Road. Follow the neon signs to the It’s Electric Neon Sign Park, dine at historic Route 66 roadside cafes, take a walk through the river bluffs and prairies and relax with a glass of locally crafted wine beside the Mighty Mississippi River.

Your one-of-a-kind adventure begins at www.RiversandRoutes.com.

By Nick Gerlich

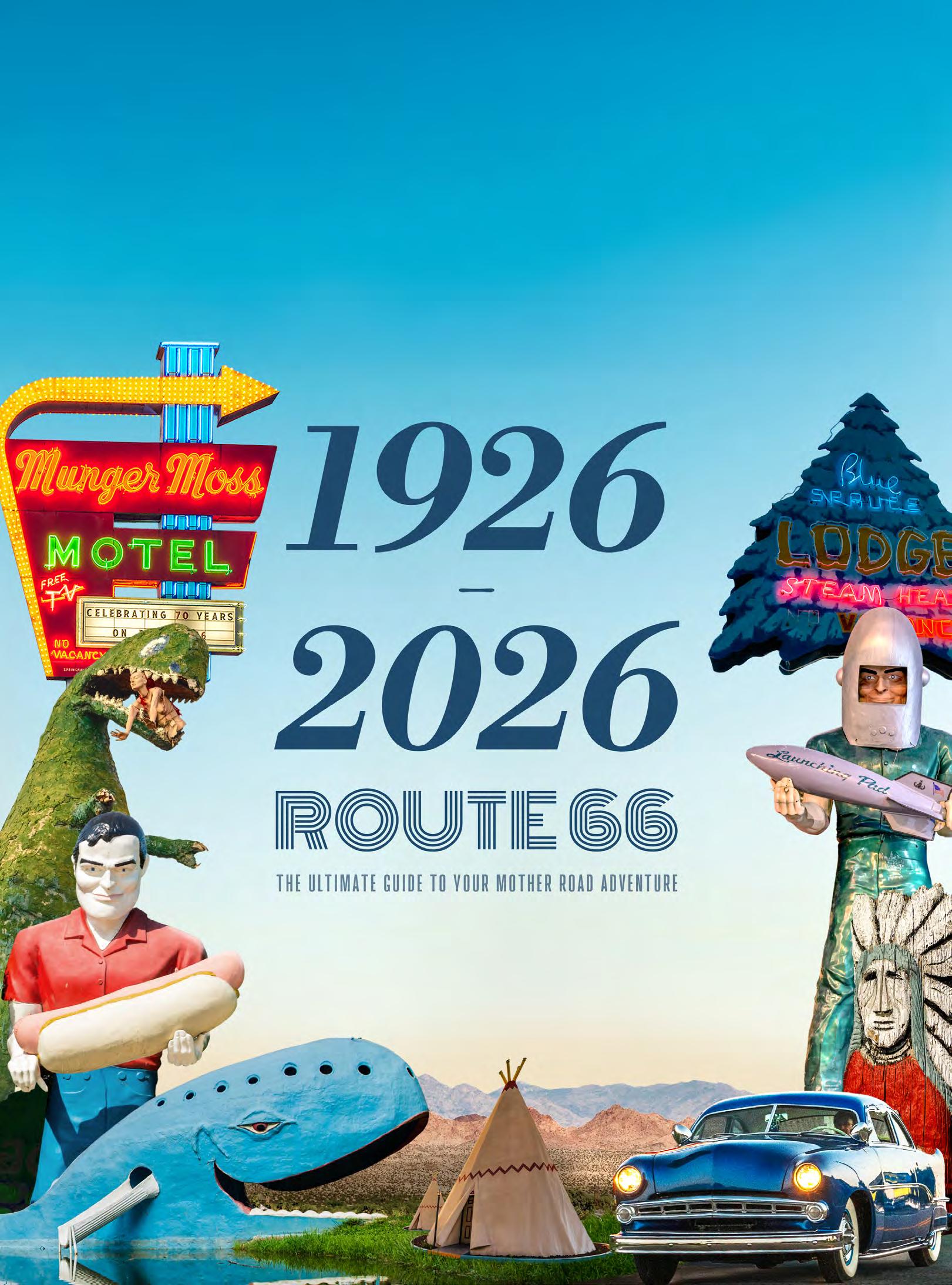

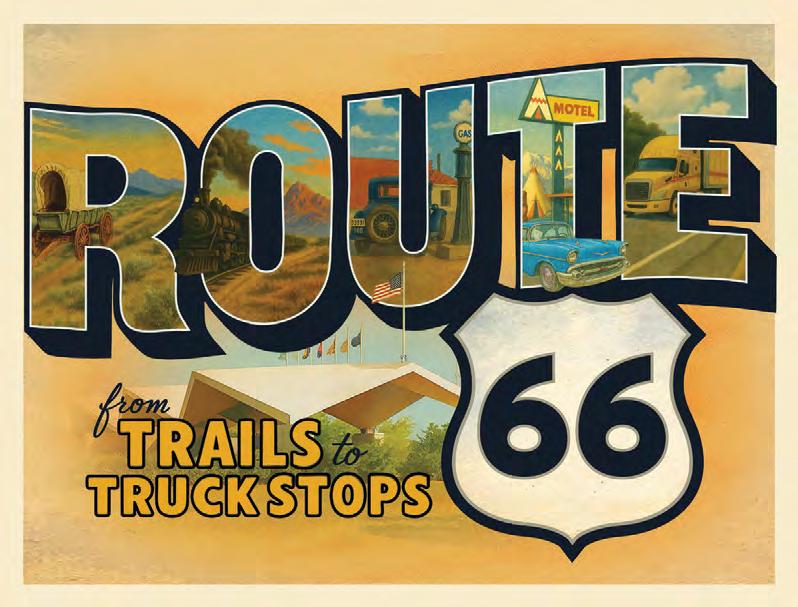

America’s Highway traces the story of Route 66—from its birth in 1926 to its lasting place in the American imagination. More than a road, the Mother Road carried families west, built towns, inspired roadside culture, and continues to invite travelers to slow down, detour, and rediscover the heart of the journey.

Roadside attractions have always been a major part of the road trip ritual—the places that make you hit the brakes, grab your camera, and smile. Along Route 66, they’re everywhere, telling stories in neon, concrete, and imagination. This hotlist rounds up our favorite picks, the must-see stops that capture the fun, weird, and unforgettable spirit of the Mother Road.

Where you stay is part of the Route 66 experience. From classic motels and historic hotels to cozy inns with stories in their walls, these places turn a night’s rest into a memory. There are plenty of options along the Mother Road, but these are our top picks—the stays we return to, recommend, and even plan trips around.

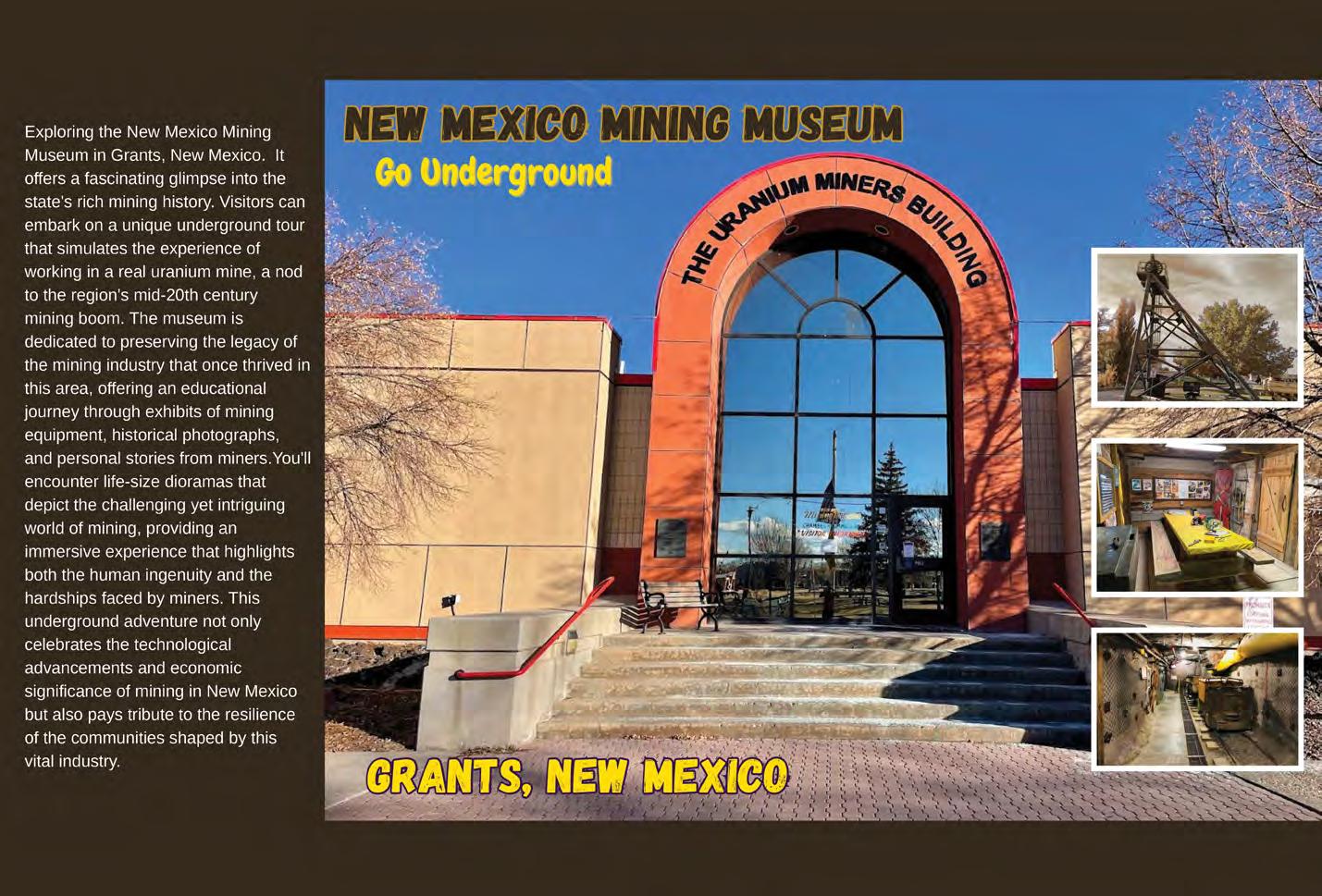

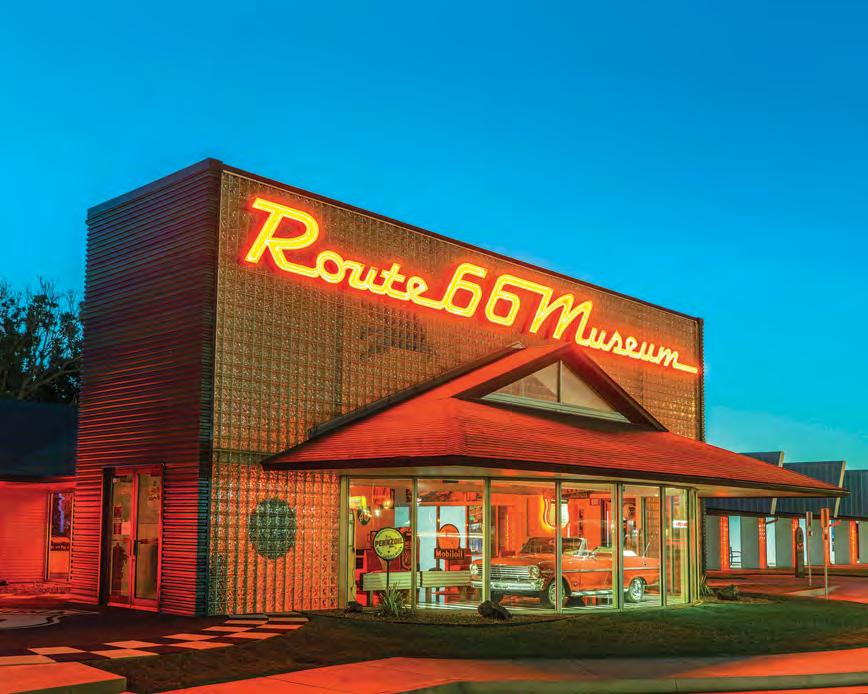

Route 66 museums are as diverse as the road itself. Some dive deep into history, preserving the people and moments that shaped the Mother Road. Others are delightfully quirky,

celebrating pop culture, oddities, and local legends. There are plenty to explore, but these are our favorites—the stops that add color, context, and unexpected fun to the journey.

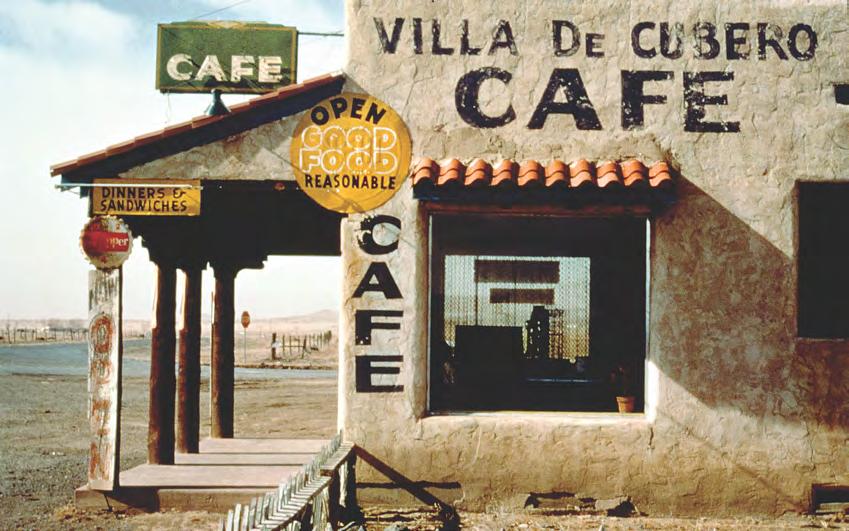

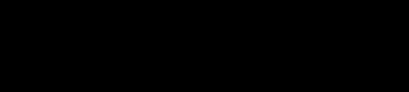

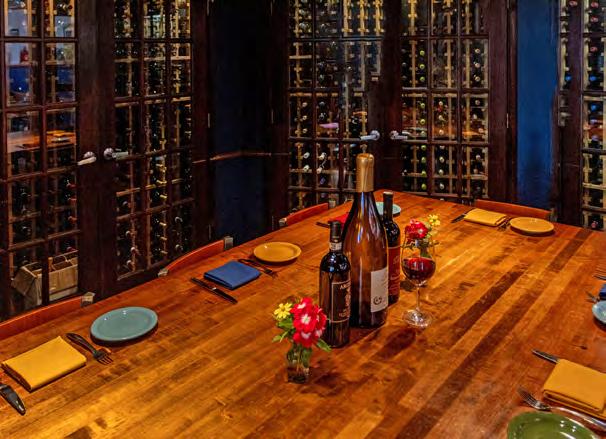

Eating along Route 66 is part of the adventure. From classic diners and roadside cafés to fine dining, every stop has its own atmosphere. The food reflects the culture and regional diversity of the Mother Road, telling stories through flavors and traditions. There are countless places to eat along the way, but these are our favorite spots to slow down, sit back, and taste the journey.

Some of the most fun discoveries are just a short drive from Route 66. These detours take you to nearby towns and attractions that aren’t on the Mother Road but are well worth the trip. Rich in history, charm, and local character, these are our favorite side trips—easy drives that add unexpected highlights to any Route 66 adventure.

Arizona is packed with fantastic destinations that attract visitors from across the globe. However, not all of them have a story that demands to be told. The Arizona Hideaway Collection does. Showcasing a trio of unique, character-filled stays that turn any side trip into an experience, each property has its own personality, blending comfort with charm and a tale you will want to know.

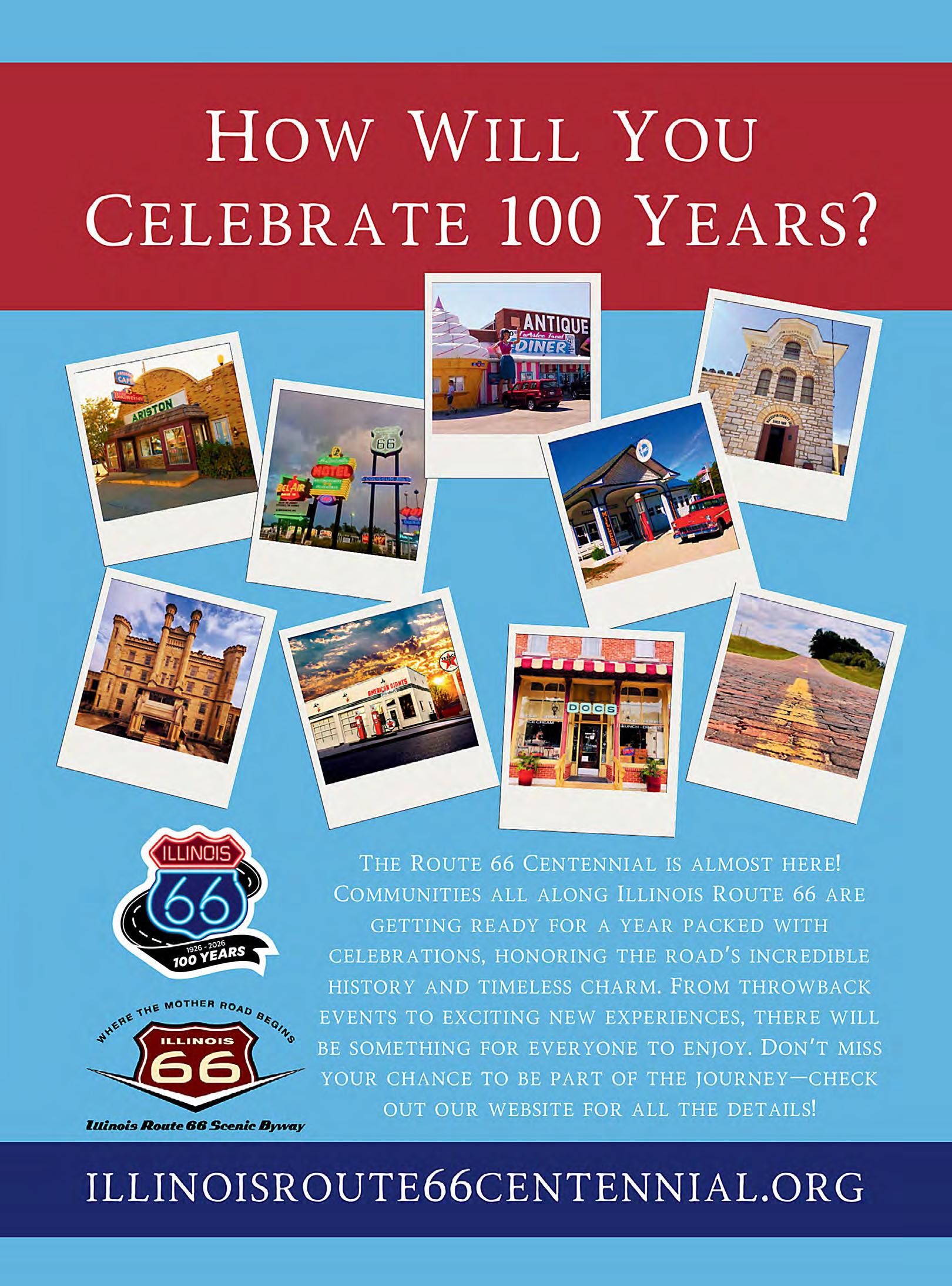

This year marks a remarkable milestone: the centennial of Route 66, the Mother Road that has captured the hearts and imaginations of travelers for a century. From the bustling streets of Chicago to the sun-soaked deserts of California, Route 66 has long been more than just a highway—it is a living testament to America’s spirit of adventure, freedom, and discovery. And in this special issue, we are thrilled to bring you our first comprehensive guide to the places, experiences, and quirks that make a journey along Route 66 unlike any other.

Planning a road trip along this iconic route is both exhilarating and daunting. The Mother Road stretches nearly 2,500 miles, cutting through small towns, big cities, deserts, and plains, each with its own story to tell. Along the way, travelers encounter everything from historic motels and diners to picture-perfect roadside attractions that range from the whimsical to the beautiful. Route 66 isn’t just a drive—it’s a treasure hunt, a series of moments and memories stitched together by asphalt and imagination.

In this inaugural guide, we’ve focused on what we believe are the very best stops along the route. That meant making some difficult choices. Every museum, restaurant, venue, and roadside oddity along Route 66 has a story, a charm, and a community of passionate caretakers. We have enormous respect for each and every one of them, and we hope that in celebrating our favorites, we also shine a light on the spirit of care and preservation that keeps the road alive. With so much to see and do, we’ve had to be selective—but we’ve done so with care. In truth, if space allowed, numerous others would have been included, too.

Whether you’re chasing the neon glow of vintage signage, savoring a perfectly cooked burger or steak in a classic diner, or discovering a quirky roadside attraction that leaves you in awe, this guide is meant to be both inspiration and roadmap. We hope it encourages readers to plan not just a journey down a highway, but an adventure that lingers in the mind long after the trip is over. Along the way, you’ll find stops that evoke nostalgia, experiences that surprise and delight, and hidden gems that might not be in any other guide.

One of the joys of Route 66 is that it offers more to see, do, and discover than any other highway in America. Its layers of history, culture, and Americana are unmatched, and the journey is always bigger than the sum of its parts. This guide captures only a fraction of what the Mother Road has to offer, but we hope that fraction will spark curiosity, excitement, and perhaps a little wanderlust. We’ve chosen stops that resonate, whether for their history, their design, their flavor, or simply the feeling of stepping into a story that has been unfolding for generations. In addition, we have included a few exceptional towns that are off the route but very much worth a detour. Give them a visit.

As we celebrate this centennial, we invite you to take your time on the road. Stop for coffee in a town you’ve never heard of, linger at a roadside attraction that makes you smile, and make a night of staying in a venue where the neon sign hums as you drift to sleep. Route 66 is not just a route from point A to point B— it is a journey of discovery, curiosity, and joy.

We hope this special issue becomes your companion on that journey, helping you uncover some of the best that America has to offer, on and off the historic route, while reminding you that the adventure is always in the discoveries and the magical moments along the way.

Happy centennial, Route 66. Here’s to another 100 years of stories, surprises, and unforgettable miles.

Blessings,

Brennen Matthews

Editor

PUBLISHER

Thin Tread Media LLC

EDITOR

Brennen Matthews

DEPUTY EDITOR

Kate Wambui

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Nick Gerlich

LEAD EDITORIAL

PHOTOGRAPHER

David J. Schwartz

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Tom Heffron

DIGITAL

Yasir Ahmed

ILLUSTRATOR

Jennifer Mallon

EDITORIAL INTERN

Skyler Graham

CONTRIBUTORS AND PHOTOGRAPHERS

Billy Brewer

Chandler O’Leary

Denis Tangney Jr.

Eric Jacobson

Efren Lopez

Joe Sonderman

Justin Towers

Katy Pair

Kevin Eatinger

Kyle Ledeboer

Robert Reck

Rebecca Rust

Scott Flanagin

Terrence Moore

Cover designed by Khamadi Ojiambo

Editorial submissions should be sent to brennen@routemagazine.us.

To subscribe or purchase available back issues visit us at www.routemagazine.us.

Advertising inquiries should be sent to advertising@routemagazine.us.

ROUTE is published six times per year by Thin Tread Media LLC. No part of this publication may be copied or reprinted without the written consent of the Publisher. The views expressed by the contributors are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, or service contractors. Every effort has been made to maintain the accuracy of the information presented in this publication. No responsibility is assumed for errors, changes or omissions. The Publisher does not take any responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts or photography.

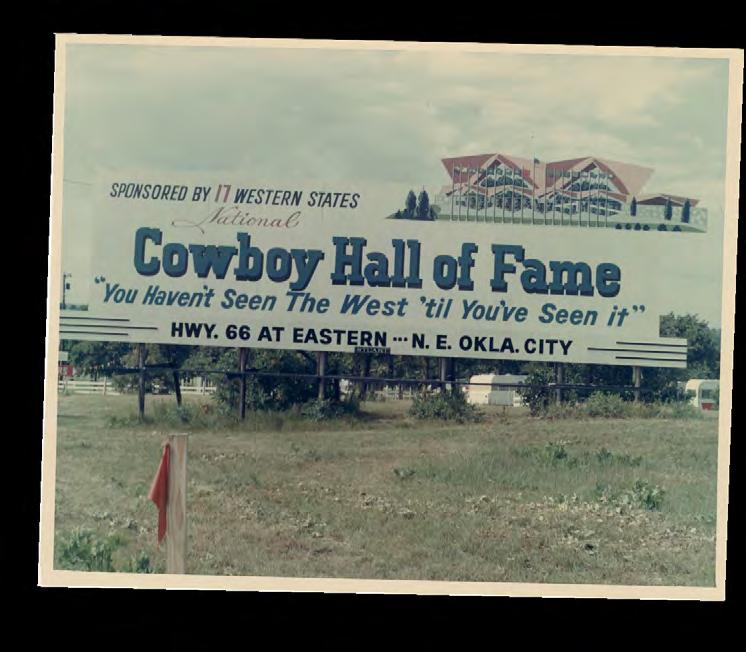

When cruising Route 66, Oklahoma City is a must-see destination. OKC’s vibrant districts welcome visitors into their diverse local restaurants and shops. Our classic neon signs and inspired murals evoke the nostalgia of the Mother Road, providing fun by day or night. Our world-class museums and only-in-OKC experiences will ignite memories for a lifetime.

Start your journey at VisitOKC.com.

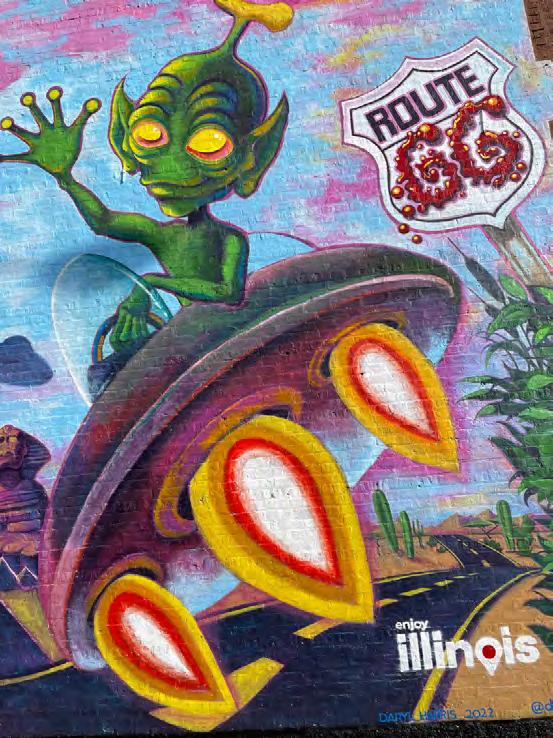

Route 66 showcases the power of community across America. The Mother Road is the central artery of the country, carrying people and goods as they venture westward (or eastward). Its allure may be within the vast landscapes surrounding the road and the unusual stops along the way that scream “photo-op”, but its renowned legacy is defined by its people. From muralists adding a splash of color to charming towns, to small retail shops partnering with preservationists, the route has long symbolized how collaboration brings forth innovation and prosperity. As Route 66 celebrates its 100th anniversary, one important national organization is leaning into such collaboration to keep the harmonious spirit of the road alive.

The Route 66 Centennial Commission is like the talent scout of historic Americana: this federally established group of 15 president-appointed commissioners identifies projects and events to honor the centennial and recommends a federal agency, like the National Park Service, to support the implementation of these projects. The projects may be artistic, historic, automotive—any endeavor that commemorates the route and the people along it.

Like many great ideas along America’s Highway, this one started with a small meeting in a medium-sized town: Springfield, Illinois. Almost ten years ago, Bill Thomas of Atlanta, Illinois, met with former Illinois State Representative Tim Butler and former Illinois Congressman Rodney Davis. Thomas has long fought for the route; in addition to serving as one of the commissioners on the Centennial Commission, he is the Chairman of the Route 66 Road Ahead Partnership, a national not-for-profit advocacy organization focused on preserving, promoting, and reviving businesses and attractions along the route. When the three met, they quickly planned how to bring their roadside dreams to Capitol Hill.

Centennial Commission, and Darren is going to introduce the legislation to designate Route 66 as a new National Historic Trail.’ And that was the start of it.”

The congressmen introduced H.R. 66 in 2017, and their vision became official on December 23, 2020, when President Trump signed the Route 66 Centennial Commission Act into law. Yet, it took an additional two years to actually form the commission—to find all the right folks to come on board. Federal officials, including the governors of each of the eight states along 66, recommended government and community leaders to the commission. By the spring of 2023, the 15-piece puzzle was complete, and the commission held its first meeting. When 15 driven, intelligent minds are in a room, there’s bound to be at least 15 different ideas. To settle debates around what they wanted to do, the Commission turned to the legislation to answer one fundamental question: What could they do? They had two main responsibilities: to identify projects and to recommend federal agencies to support the projects. Thomas proposed a strategy to give direction to these powers. This centennial, the strategy reads, should “honor the road by helping the millions who live, work, and travel along it.”

“[The strategy] allows us to deal with everything from individuals who may have planned a national [event], all the way up to a major national entity that wants to do something for the centennial,” said Thomas. “So, it’s very broad in scope, but the important thing is to raise the public’s level of awareness about the centennial and get people to participate in it.”

There are currently dozens of ways to participate, and more to come. As of December 2025, there are 54 projects designated by the Commission as official Centennial activities.

“We were saying, ‘The centennial is coming up. We got to do some stuff,’” said Thomas. “Rodney said, ‘Okay, well, tell you what. I work real closely with Darren LaHood. He’s a fellow Illinois congressman. I’ll introduce the legislation to establish a Route 66

Whether they invite you to breathe in the diverse culture and scenery along the open highway or take a moment to stop and soak in its fascinating history, the official centennial activities will undoubtedly capture the heart, icons, and stories that have shaped Route 66 over the last 100 years. Stories of struggle and triumph, of defeat and redemption—stories that we can’t wait to celebrate this year, and for years down the road.

By Nick Gerlich

Born on November 11, 1926, by virtue of federal law creating numbered U.S. highways, Route 66 found itself immediately thrust into an unprecedented economic depression. It was conceived and designed to connect U.S. cities from Chicago to Los Angeles, facilitating travel and commerce. Instead, it wound up becoming, for a time at least, a channel of human migration, a highway of hope, and an avenue for adventure and soul searching. And that is just the start.

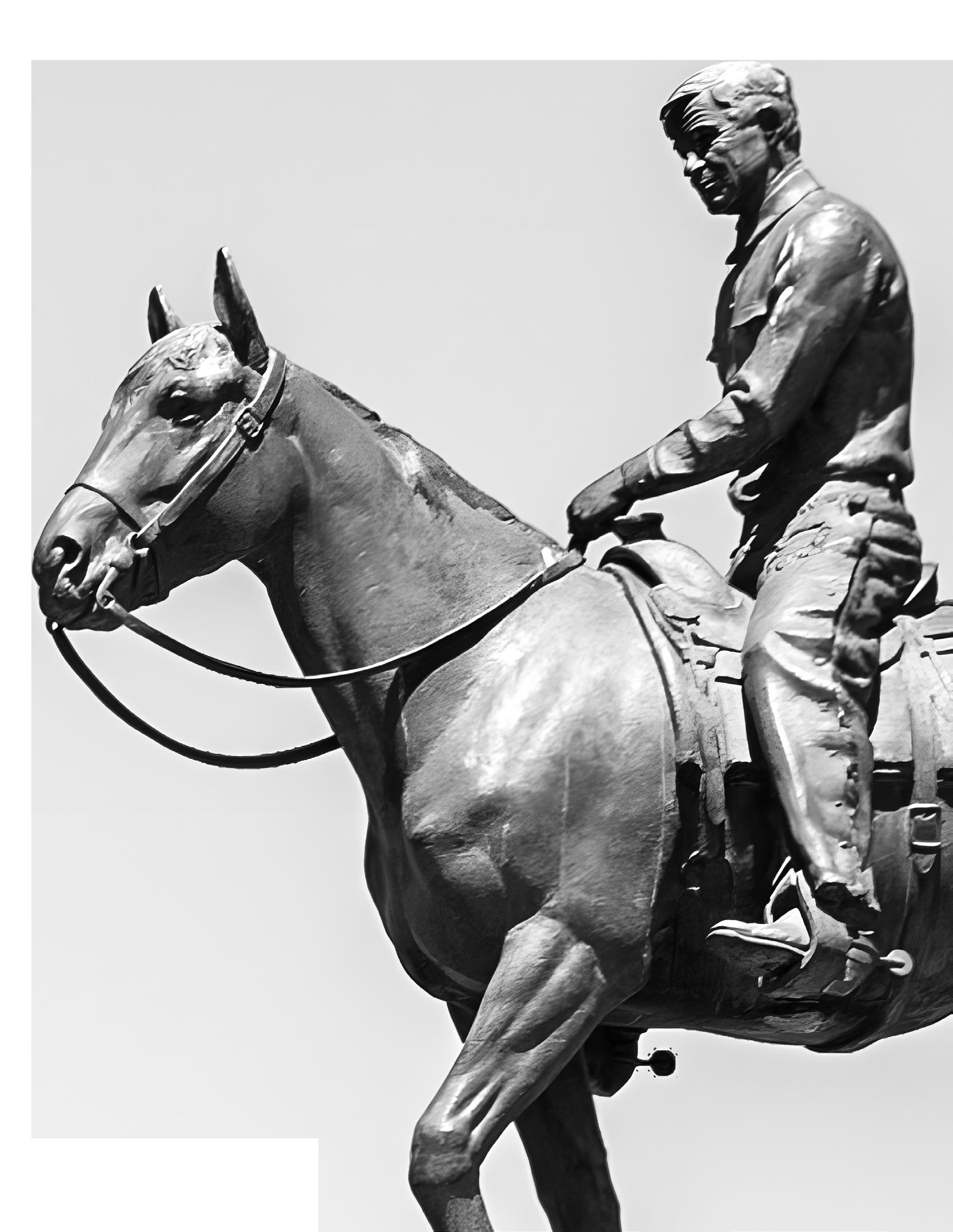

And it’s likely that the road’s champion and patron saint, Cyrus Stevens Avery, never dreamed that the passageway that he conceded to be called 66 would evolve as it did, from desperate straits to boulevard of dreams, and ultimately weave itself into the pop culture psyche of a nation that would one day yearn nostalgically for those good old days.

It was in 1896 that the first gasoline-powered car was sold in the U.S.A. But a car was only as good as the roads beneath it, and there were few improved roads outside city limits. By 1912, there was movement afoot by cities and private developers to create highways, a decision that resulted that year in the creation of the National Old Trails Road, followed by the Lincoln Highway’s dedication in 1913, and the Dixie Highway and Jefferson Highway in subsequent years. All told, more than 250 of these named highways comprised the National Auto Trail system.

The rapid growth of demand for the automobile caused the need for federal oversight, planning, and funding. Several federal highway acts came into law in the late 1910s and early 1920s, establishing federal-state cooperation on road building. These efforts culminated in the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) approving the numbered U.S. Highway System on November 11, 1926.

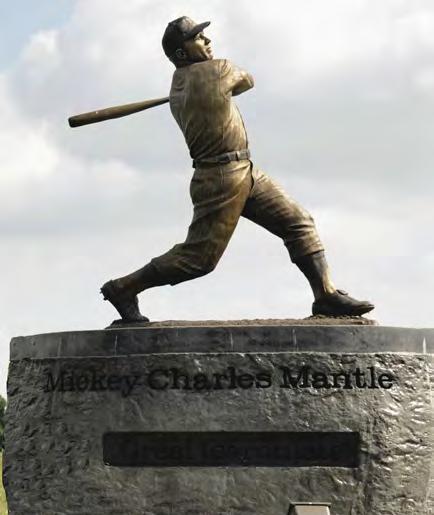

It was into this arena that Cyrus Avery found himself. Avery, a Tulsa businessman, and perhaps no more in tune than anyone else regarding the practical aspect of driving — quite literally — local commerce via this national highway network, set out to make sure that his hometown was not overlooked.

“The National Highway System was put in place at the edge of the Depression,” said Susan Croce Kelly, Avery’s biographer in Father of Route 66. “The geography between Chicago and Los Angeles is one of small towns, farms, mines, and open space. During those years — 1926 until 1938, when the whole highway was paved — times were tough. Farmers were leaving their land. Fully a quarter of the population was out of work,” Kelly added. “Cy Avery was a big community booster, and he was very interested in Tulsa’s success.”

Avery’s proposal, like most other highways under consideration at the time, relied on simply connecting — on paper, at least — previously existing roads, many of which were still dirt and at times hardly drivable. AASHO had laid out the basics of the numbering system, with even numbers running east-west, and odd numbers running north-south. Routes ending in “0” for east-west, and “1” or “5” for north-south, were considered primary corridors and were to be used for transcontinental highways. With that in mind, Avery went after Highway 60 for his road stretching from Chicago to Los Angeles.

“Cy was on the committee that determined which roads would be the cross-country or national highways. That is, he helped draw the map,” Kelly continued. “Later, he was on a five-man committee to number the roads. Avery knew that the trade route from the middle-west went north to Chicago, not across the Appalachians to the East Coast. [His route] followed the main trade route.”

Still, Avery was vulnerable, and Governor William J. Fields of Kentucky protested, arguing that a Highway 60 should indeed traverse the country, and specifically his state. Because Fields had more clout and a more reasoned argument, he prevailed, and Highway 62 was offered as an olive branch to Avery.

To Avery’s great credit, he was so displeased with Highway 62 that he went looking for other unused numbers and found that 66 was available. He named it and claimed it in perhaps one of the most opportunistic name grabs ever. It was a bloodless coup.

It is in retrospect that the importance of this highway can be seen in whole, as well as within context of significant events. The optimism of the Roaring ‘20s, in which the automobile became increasingly affordable and highways allowed for mobility, found early tourists doing the Charleston and singing Sweet Georgia Brown as they hit the road. But life ran into an abrupt speed bump in 1929 with the stock market crash, a harbinger of things to come.

With an economy on the skids, discretionary activities were put on hold. A year later, a seven-year drought and dust storms of epic proportions crippled farmers

in the nation’s midsection, giving rise to an enormous westward human migration. While the fluidity of humans was witnessed on all corners, it was Route 66 that became a primary conduit of desperate people seeking a new start in California. The exodus was significant, with 210,000 refugees heading west to escape their despair.

Times were tough, and the roads even tougher. Long dirt sections tempted some to create mud bogs, as the Jericho, Texas, story goes, and then demanded travelers pay up to get towed out. But others were more forgiving, sometimes letting travelers barter or work off their debt for lodging. The desert, too, was tough, with stations few and far between, and cars drinking both water and oil in such large quantities that motorists had to carry supplies of both. It was still a time, though, when mom and pop could hang their hopes on the roadside, building modest courts with only a handful of rooms, and tiny cafés for travelers to take advantage of as they motored west.

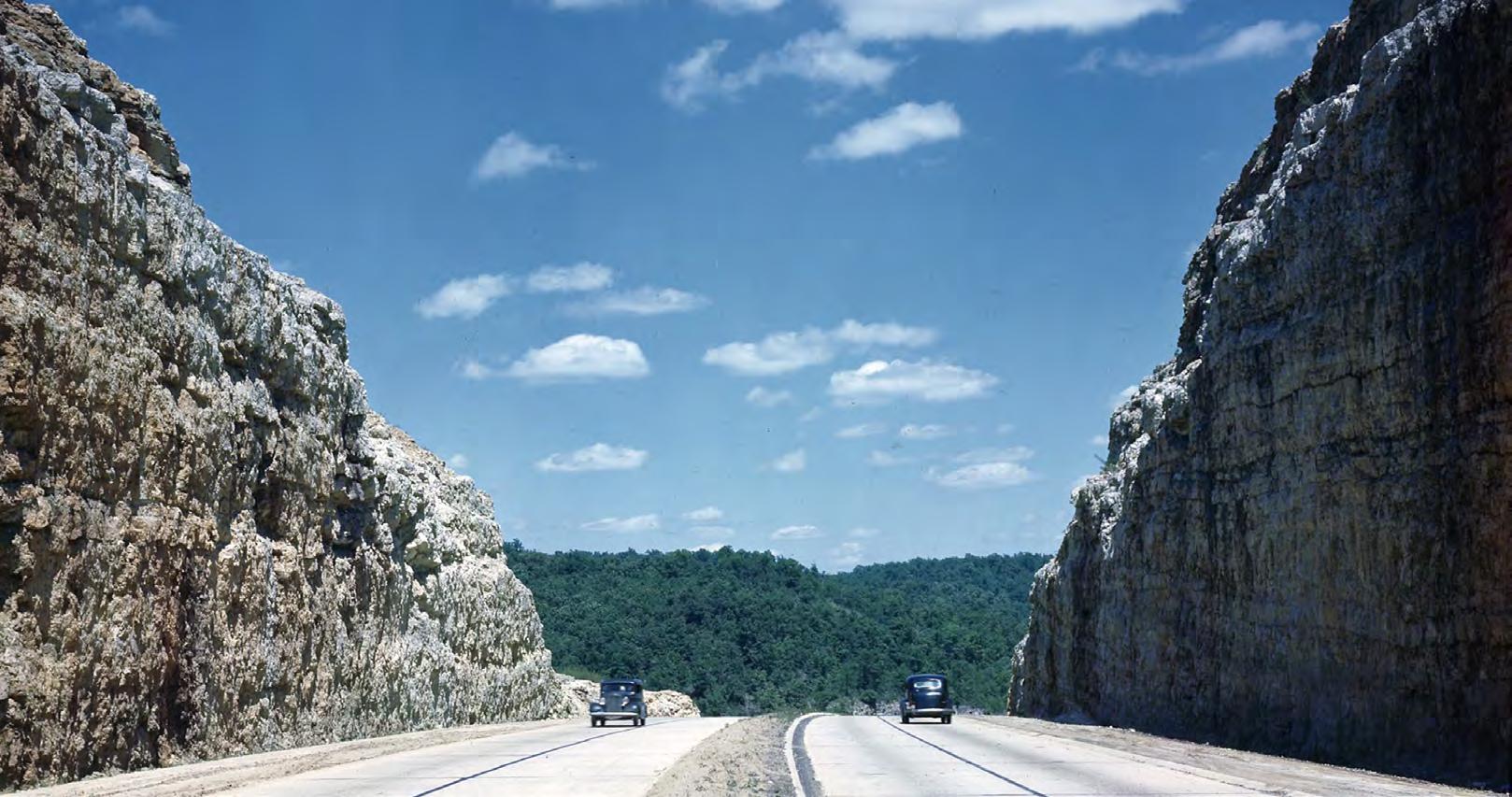

No sooner had the Depression ended than the U.S. found itself in a world war, and vast improvements were made to 66 and other roads to facilitate troop movements west. Civilian travel in the western states dropped to only 100 people per day at the Arizona inspection station, replaced by military convoys moving assets around the country on the newly improved roads. It was these improvements, such as the widening of the road, that would fuel civilian travel after the war, setting the stage for the glory days of Route 66.

“Those improvements came just in time for the beginning of the Golden Era of family road trips in the 1950s, when Route 66 really hit its peak in popularity,” said Richard Ratay, author of Don’t Make Me Pull Over! “It was during this time that the sides of the highway blossomed with all the diners, drive-throughs, souvenir shops, quirky motels, and roadside attractions that we tend to associate with Route 66.” Destinations like the Grand Canyon and Disneyland were now within reach, and just a road trip away. The ‘50s also silently marked a transition from independent motels to the new chains, like Holiday Inn, Howard Johnson, and Ramada Inn. As it always was, the road was changing.

This new optimism produced a cultural epoch that is still that of legends. With the troops back on familiar soil, it was time to get on with creating families. The American Dream meant owning a house in the suburbs,

a car in the garage, and a television in every living room. The family vacation became a heralded component of our existence, and Route 66 was the beneficiary of this desire to see the country.

Although America’s Main Street was but a youngster at the time, the significance of the road was not lost on screenwriters, poets, musicians, and authors like John Steinbeck. The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck’s tenth book, captured the difficulties of the Dirty Thirties, even if dressed as a novel. Released in book form in 1939, and adapted for the silver screen in 1940, it was here that the phrase “Mother Road” was coined, a metaphor perhaps of a mother’s love, a lullaby to cradle the economic victims.

In 1946, Route 66 was once again heralded in both book and song. Jack Rittenhouse’s A Guide Book To Highway 66 provided travelers with basic information about highway amenities at a time when information was scarce. But it was Bobby Troup’s snappy tune that caught people’s fancy.

While some U.S. highways have inspired songwriters and lyricists to wax poetic about a slab of pavement, none have come close to the popularity of (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66, a tune and lyrics Troup perfected in 1946 while traveling on a cross-country road trip with his wife to the West Coast. The infectious number, which had more hooks than a tackle box, went on to become the unintended theme song for generations of two-lane highway travelers.

Although Nat King Cole recorded the track initially, more than 200 versions have been recorded since, by artists as diverse as the Rolling Stones, Chuck Berry, Manhattan Transfer, and Depeche Mode. The song spent eight weeks on the pop charts, and by the time Troup died in 1999, he had earned more than $4 million in royalties from this song alone.

Troup’s tune became a cultural touchstone for generations.

While musicians were busy adding their own flourishes to the song, Hollywood was readying the television debut

of Route 66 the series, which chronicled the adventures of Tod and Buz (and later, Linc) as they traversed America in search of discovery. The CBS show would air 116 episodes from 1960-1964. Although the series had only a handful of minor scenes actually filmed on 66, it was the metanarrative of road trips and adventure that sold it to viewers.

And what if Route 66 had been awarded the coveted Route 60 or Avery had accepted Route 62? “It’s hard to say how differently we might perceive the Chicago-toLos Angeles highway had it been numbered 60 or 62. Maybe Bobby Troup would have never written that song, or the CBS television show would never have aired. But even without the songs or TV shows, I think the road would have developed a cultural significance,” said historian Brian Ingrassia.

The timing was perfect for the Mother Road. “Route 66 came along at a time when popular culture got a boost from media innovations like radio, phonograph records, and television. It was nearly inevitable that these modern technologies would make some American roads legendary,” Ingrassia added.

Route 66 was probably never intended to last forever. It was a work in progress, an idea in motion. The ink had hardly dried on the original alignment before new paths were already carved out that effectively bypassed the very towns that the road was intended to link, such as tiny Depew in northeastern Oklahoma, Odell and a slew of other Illinois towns, and Amarillo in Texas.

The Main Street of America had become a bottleneck. In fact, the Route 66 maps

were in a state of flux, as engineers were always trying to improve it. In Illinois, the original alignment southwest from Springfield along what is now IL Route 4 was moved in 1930 to where the modern freeway is. The nine-foot-wide “sidewalk highway” between Miami and Afton, Oklahoma, was moved and widened considerably in the process. And the politics of dancing loomed large in New Mexico when outgoing Governor Arthur Hannett decided to exact his revenge for losing re-election by simply rerouting 66 directly across the state and away from Santa Fe.

Perhaps the biggest sign of this change came in 1953 with the opening of the Turner Turnpike, linking Tulsa with Oklahoma City, and completely sidestepping the earlier version of 66. It was a taste of things to come, notably the Interstate Highway System being signed into law in 1956. Four-lane superslabs became the de facto mode of ground transportation across the U.S., and

by 1970, all original segments of Route 66 had been bypassed by either a new freeway or standard four-lane high-speed. Lifestyles had become fast-paced. Gas was still cheap, and our love affair with the automobile continued unabated. People became less interested in the journey, and more concerned with the destination.

Roadside attractions like the 1974 Cadillac Ranch in Amarillo, the product of the late Stanley Marsh 3, gave motorists even more reason to stick to the freeway, if only to view one man’s quirk. Marsh sought to entertain tourists with his public art installation, albeit with the undercurrent of a marketing critique of tail fins. The original location was never on Route 66, but instead along I-40 on the city’s west side.

Although it took more than a decade longer to come close to completing the Interstate project, Williams, Arizona, famously became the last Route 66 town to be bypassed in 1984. A year later, on October 13, 1985, Route 66 was formally decommissioned at the federal level, and its number forever removed from the federal inventory of highways. Suddenly, there was nothing but memories.

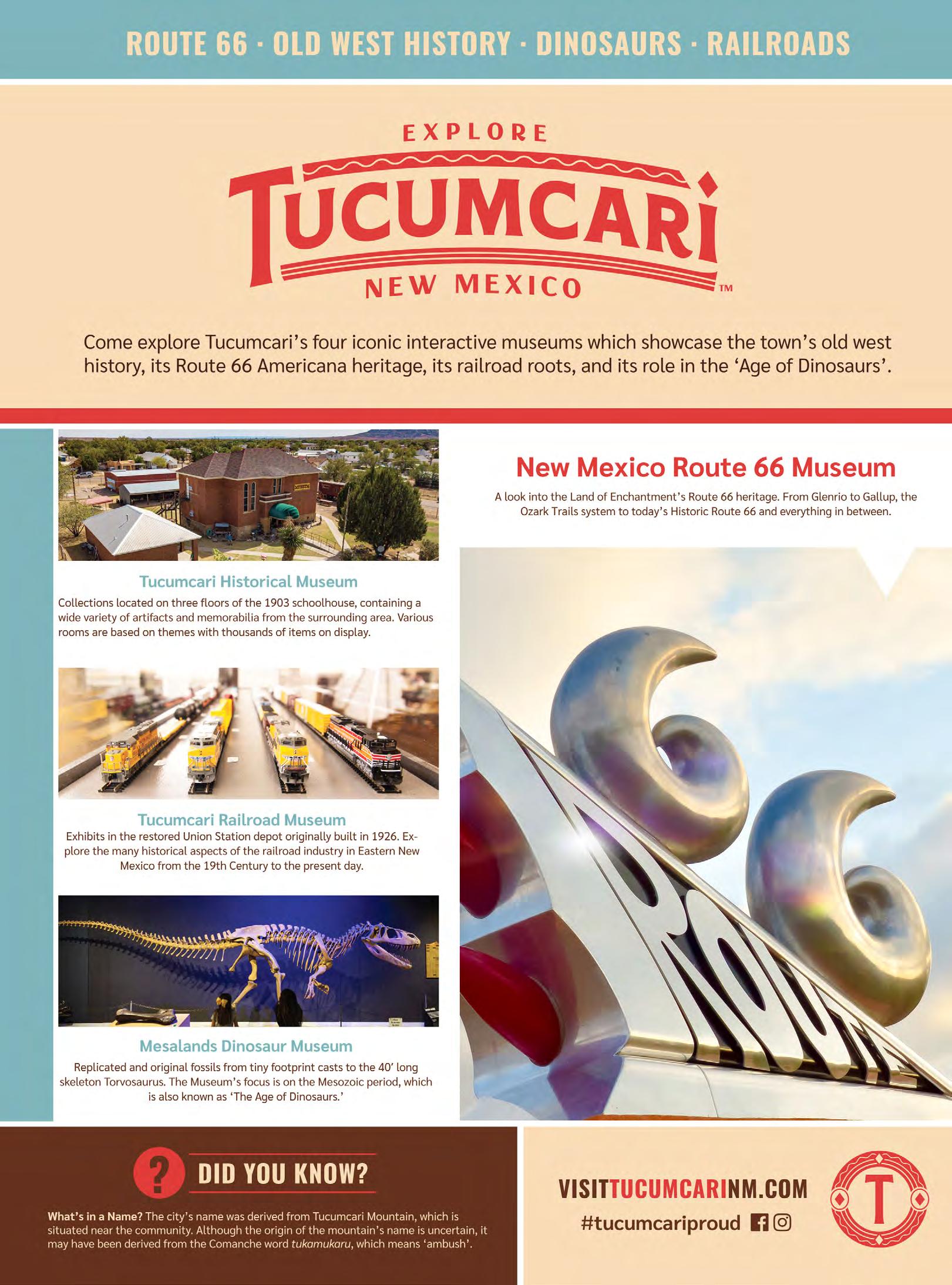

All the while, the ravages of progress were being witnessed along the Route. Tucumcari, which once proudly advertised having 2000 rooms, saw its total cut in half, and even that amount accounted for, in large part, new properties near the freeway. Cafes were replaced by fast food and formulaic chain restaurants, and gas stations were replaced by sprawling travel centers. Everyone from Afton to Ash Fork and elsewhere along 66 was affected. Glenrio, Texas, Cuervo, New Mexico, and others became ghost towns in plain view of the interstate. And once incredibly popular attractions like the Blue Whale of Catoosa, Oklahoma, and the Gemini Giant in Wilmington, Illinois, languished in solitude.

The small towns that dot the Will Rogers Highway could have accepted their fate and closed shop like many a community during the economic depression. No one would have blamed them for moving on to greener pastures. But they didn’t.

Soon there was a moment afoot and a vision was being formed. It only took a couple of years before a friendly barber from Seligman, Arizona — Angel Delgadillo — recognized the void that had been created. He became angry, frustrated that his once bustling town and Route 66 were seemingly being forgotten. He decided to act. Thanks to him and the town’s leaders, a revival was started, and in 1987, they formed the Historic Route 66 Association of Arizona. Soon Missouri followed suit and within a few years, each of the other seven states through which Route 66 had passed formed their own associations.

This set the wheels in motion, and it was only a matter of time before a cottage industry of authors sprang up to tell the story of this old road that represented the history and very essence of America, one that was increasingly finding new life as a vector of nostalgia.

Quinta Scott, co-author with Susan Croce Kelly of Route 66: The Highway And Its People (1988), and later sole author of Along Route 66 (2001), was an

early voice to chronicle this fabled road. Motivated by the urgency of collecting oral histories while pioneers of the Route were still alive, she set out to discover what it was like living and doing business along 66. After all, as she quickly learned, “Something important happened on it during every decade of the Twentieth Century.”

By limiting the project to people who came to the highway between 1926 and 1956, Scott was guaranteed a historical perspective. In so doing, she and Kelly produced a seminal work that is still highly regarded today, capturing the ethos of the road before anyone else thought to do so.

Within a couple of years, author, historian, and voiceover artist Michael Wallis had released the national best-seller Route 66: The Mother Road, which, along with Scott and Kelly, created critical mass for a movement looking back at what the nation had summarily dismissed.

Wallis, too, felt the need to set the story straight. “My motivation in writing the book was quite simple. It was the fact that I grew quite weary of people talking about the road in the past tense. I knew that the majority of the Mother Road was still there,” he said. More importantly, though, “The best resource the road had to offer was still there, and that is the people.”

Before he wrote his book, he took a lengthy exploratory trip along 66. “We found so many different situations. There were people who were quite down about the road, and I’m talking about business owners. A lot of them were really down.”

But Wallis saw hope and tried to reignite the flame. “Even the majority of those people who were feeling blue always had a little flickering light of hope. Like blowing on a fire, that little tinder to get that blaze going again, that’s what I tried to do.”

Wallis continued, “I did that several times, even with somebody who guffawed at me. ‘Why would somebody read a book about this old road?’ And I would turn it right back on them and say, ‘Alright, you tell me about the road.’ And then they would tell me about the road.

‘This is the road I grew up on. I own this business. My grandfather owned it.’ And they would keep talking and talking, and after they went through this whole litany of their connection to the road and its importance to their life, they would fall silent. Oftentimes I would see tears in their eyes. And then they would say, ‘Thanks. I’m really glad you’re doing this.’”

Over the next 30 years, more than 200 books on Route 66 would be written, not to mention the 2006 release of Pixar’s hugely successful film, Cars, which told the story of the fictional Route 66 town, Radiator Springs, and introduced an entirely new generation to America’s Main Street. Wallis, as the voice of the Sheriff as well as consultant to Pixar, made certain to remind people that Route 66 was not life in the past lane.

Cyrus Avery died in 1963, just shy of his 92nd birthday, but at the time of the road’s inception, when he was 55, he could never have imagined the cultural touchstone that his highway would one day become. His vision was based merely on transportation and commerce, not the desperate drive of Dust Bowl refugees, the movement westward by men in uniform, the cure for wanderlust that post-war families discovered, and certainly not the

modern yearnings of young and old alike to experience an America now largely in the rearview mirror.

No, it was all about dollars and cents.

Much more than the conduit for travel and business that he envisioned, it became something much larger, something that became part of the very fabric of America. It was a road of hope, a passage to adventure. It carried troops in time of war, and a Troup who would wax poetically melodic about it. And today it carries people away from the present to an ever-distant past, paving the way to a future based on the business of nostalgia and history seekers.

“Route 66 has had such an impact on the American imagination because it was a well-traveled road at the very time when American road culture was being invented between the 1920s and the 1950s,” said Ingrassia. “This was the era when Americans were traveling west, moving to places like Los Angeles or heading to Las Vegas or taking their families on roadtrip vacations to national parks or other historic sites.”

The federal designation may be gone, replaced by the brown or blue signs (depending on the state) denoting historic highway status. States like California have proudly painted the Route 66 shield on the pavement to show the way, while individual cities have championed mural projects and other elements to showcase their Route 66 status.

Traveling Route 66 today has never been easier. While Rittenhouse’s book was certainly helpful for ‘40s-era motorists, it lacked detail and required users to mentally keep track of miles between vaguely described roadside amenities. Today, we have artist Jerry McClanahan’s EZ Guide and multiple mobile apps to provide turn-byturn directions. All we have to do is show up.

Better yet, Route 66 has become big business. With as many as a half-million visitors each year, and countless others who are not counted, if only because they are daytripping or seeing 66 in bits and pieces, commerce along the Route is more important than ever.

The resilience of the road and its people is manifested in the examples of those who kept going in the face of adversity. “It’s kind of in the DNA of Route 66,” Wallis added. “They knew they had to have some element to attract the people and to lure them off the interstate. That’s why Lillian Redman [late innkeeper at the Blue Swallow] kept clicking on those blue swallows every night.”

Visionary entrepreneurs have stepped up to the plate to restore and relaunch once popular icons of the road, including many of the historic motels along the road. Kitschy gift shops are common again. Roadside attractions and museums are alive and well and welcoming visitors. Route 66 has new attractions coming up constantly, and the magical U.S. artery is finding new ways to celebrate the American Dream regularly.

The bulk of travel and commerce is now conducted via the freeway. But the old road is still alive, just serving a different clientele. “I needed to write a love letter to this highway, and let people know it is there,” Wallis added.

Scott painted a similar picture. As she aptly opened in Along Route 66 and its long look back in order to look ahead, “It was the way out.”

And it still is.

Quirky roadside America is more than a backdrop for snapshots—it’s a living chapter of the nation’s cultural story. These offbeat stops were born from long drives, family vacations, and a time when the journey mattered as much as the destination. From handmade sculptures to giant icons rising from empty highways, roadside attractions reflect local pride, creativity, and humor. They invite travelers to slow down, step out of the car, and connect with a place in a tangible way. In an era of fast routes and digital shortcuts, these roadside landmarks preserve the spirit of exploration that has long defined the American road trip. These are our top picks from America’s most famous highway.

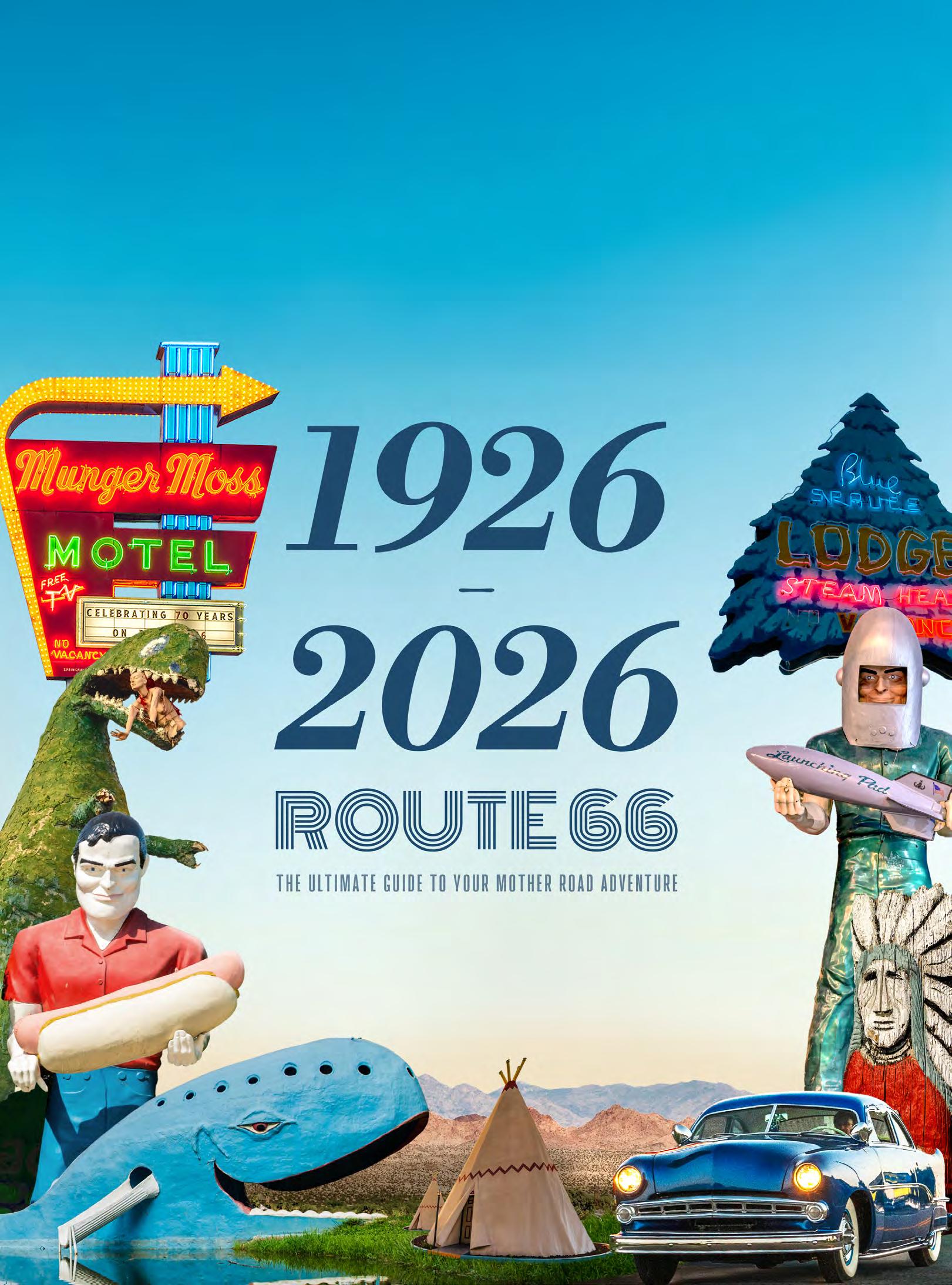

The first name on our list will be no surprise to anyone with a passion for Route 66. Over in tiny Wilmington lives a giant, the Gemini Giant, to be exact. One of only a few surviving “spacemen” Muffler Men from the 1960s, he represents a flashback to quirky roadside Americana and overthe-top advertising gimmicks. Built in 1964 and purchased in 1965 for the newly renamed Launching Pad Drive-In, he stands nearly 30-feet-tall, grinning in his shiny green jumpsuit and silver helmet, gripping a sleek rocket like a souvenir from space. For decades he greeted travelers, posing for countless photos and road-trip selfies. When the restaurant closed in 2022, his fate was once again uncertain. But in March 2024, he was sold at auction and saved for the community. By November 2024, he found a permanent home at South Island Park, a short walk from the Kankakee River—a must-see reminder of the enduring creativity and charm of roadside attractions. The Gemini Giant’s story is not just about size; it’s about the imagination of the 1960s, when local businesses embraced largerthan-life characters to draw in travelers. His creation reflected a fascination with space exploration, a symbol of the era’s optimism and American ingenuity. Over the years, he became more than an advertisement; he evolved into a cultural icon, inspiring generations to embrace the fun and unexpected moments along Route 66.

The route is filled with friendly competition. There has long been a battle to see who can hold the title of having the world’s biggest chair, a challenge that enticed business owner Danny Sanazaro in 2008. To attract customers to his archery and feed store, he built a 42-foot-tall cherry-red rocking chair, surpassing the then-record 34-foottall chair in Indiana. Even though it weighs 27,500 pounds, the chair still rocked when it was first built. Sanazaro, however, quickly realized the potential dangers of a 13-ton steel structure in motion and had the chair welded to its base. A 56-foot-tall chair in Casey, Illinois, took the blue ribbon in 2015, but Missouri’s bold rocker still embraces the playful nature of the route.

A stop at Pulaski County’s Uranus Fudge Factory is guaranteed to make you grin. A relative newcomer to the Mother Road, it was opened in 2015 by Louis Keen and has been delighting travelers with sweet treats, quirky attractions, and endless puns for over a decade. The soft, creamy fudge comes in a rainbow of flavors, but it’s the unexpected roadside charm that makes a visit memorable: the General Store brims with mid-century novelties, the escape rooms challenge your wits, and the playful “freak show” adds a dash of oddball fun. Nestled amid forested roadside scenery, Uranus seems to appear from nowhere—a little slice of whimsical Americana that celebrates laughter, indulgence, and the joy of the open road.

Roughly 30 minutes west of Springfield, Missouri, Gary’s Gay Parita is one of historic Route 66’s most beloved roadside stops, where nostalgia meets genuine Ozarks hospitality. The original Gay Parita Sinclair station was opened in 1930 by Fred and Gay Mason, serving motorists along the Mother Road until it burned down in 1955. Decades later, Route 66 enthusiast Gary Turner and his wife Lena purchased the property in the early 2000s and lovingly rebuilt a period- correct 1930s- style station, complete with classic pumps, vintage signs, and memorabilia. Gary’s warm storytelling and welcoming spirit made the stop a favorite among travelers. After his passing in 2015, his daughter Barbara Barnes and partner George Bowick carried on his legacy, greeting visitors and keeping the spirit of the Mother Road alive at this iconic Missouri landmark.

One of the coolest “towns” along Route 66 isn’t really a town at all: Red Oak II, the creation of artist Lowell Davis. Davis grew up in the original Red Oak, Missouri, which by the 1940s had mostly faded away. In 1987, he rescued buildings from Red Oak and nearby towns, transporting and reassembling them on his farm near Carthage. Visitors can wander past a Phillips 66 station, a blacksmith shop once run by his great-grandfather, a general store his family operated, and a one-room schoolhouse. Some structures were newly built in period style, but many are authentic relics. Lowell passed away in 2020, but his spirit and vision live on. What began as nostalgia became a living monument—a time capsule echoing smalltown America, restored with reverence and eccentricity.

When Route 66 first opened in 1926, travelers navigated a patchwork of roads and bridges on their journey west. One gem was the Pryor Creek Bridge in Chelsea, Oklahoma—a 123-foot Pratt truss bridge that carried motorists until the route’s realignment in 1932. Today, this graceful structure invites visitors to slow down and soak in a slice of Mother Road history. Step onto the bridge, let the creek babble beneath your feet, and feel the breeze through the towering trees that frame this idyllic spot. Off the beaten path and far from the crowds, it’s a quiet escape, and a place to linger, dream, and imagine the pioneers of Route 66 as they rolled westward.

No attraction captures the magic of Route 66 quite like Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole Park. Retired teacher and folk artist Ed Galloway began his labor of love in 1937, inspired by Native American culture and a passion for woodworking. His first masterpiece, a 90-foot-tall hollow totem completed in 1948, rises from a giant turtle, depicting man and nature in harmony. Over the next decades (1937–1961), Galloway added smaller sculptures, including an Arrowhead, Birdbath, and Tree totem, and the 11-sided Fiddle House, all part of the park’s 11 major totems and structures. Today, the Rogers County Historical Society welcomes visitors to picnic, wander, and fall in love with this whimsical, historic folk-art wonder.

Blue Whale, Catoosa, OK

Imagine rolling down historic Route 66 and spotting something impossibly joyful: the Blue Whale of Catoosa, a towering 20-foot-tall, 80-foot-long concrete whale perched beside a spring-fed pond. Built by retired zoologist Hugh S. Davis and a friend in the early 1970s, it was unveiled on September 7, 1972, as a surprise anniversary gift to his wife, who loved whales, and quickly turned into a beloved swimming hole and roadside wonder. Families dove from the tail, slid down the fins, and swam beneath the whale’s smiling gaze. By 1988, as the Davises aged and traffic faded, the park closed, and time took its toll. But in 1997, local volunteers and the town rallied to restore Blue, repainting and reopening it as a nostalgic Route 66 icon. Today it stands bright and welcoming, a quirky, dreamy pause for any road-trip heart chasing heritage, childhood, or wonder.

Few symbols scream Americana like a bottle of Coca-Cola, so it’s only fitting that a giant soda bottle dominates the front yard of Pop’s Soda Ranch in Arcadia. Opened in 2007, Pop’s serves a dazzling selection of more than 700 sodas, but the real star is the 66-foottall steel bottle, a playful nod to Route 66 itself. Lit by color-shifting LEDs, it glows like neon on a warm Midwestern night, perfect for photos and a little roadside downtime. Its sleek, modern design hints at the 2000s era, while the rainbow glow honors the neon tradition of the Mother Road. Pull up, sip on a soda, bite into a juicy burger, and feel the quirky magic of classic Americana come alive in one unforgettable stop.

Fans of Pixar’s Cars will instantly recognize the Conoco Tower Station & U-Drop Inn Cafe, the Art Deco icon that inspired Radiator Springs’ glowing “body art” shop. Built in 1936 by J. M. Tindall and R. C. Lewis, this combined gas station and café quickly became a beloved stop for Mother Road travelers. Its soaring vertical lines, textured canopies, and playful bubbleletter signage capture the elegance and whimsy of the 1930s, while a hanging arrow sign guides visitors inside. Neon tubing traces the building’s contours, lighting up Shamrock’s night sky in dazzling color. Picture perfect!

If there’s one thing Amarillo has in spades, it’s character: from the 72-ounce steak challenge at The Big Texan to a century-old saddle shop, the city is full of bold roadside surprises. None is more iconic than Cadillac Ranch, installed in 1974 by the art collective Ant Farm — Chip Lord, Hudson Marquez, and Doug Michels — with Amarillo patron Stanley Marsh 3. Ten classic Cadillacs (1949–1963) were buried nose-first into the ground, their tailfins jutting skyward in a playful, subversive ode to American road travel. From the start, visitors were encouraged to add spray-paint designs, turning the installation into a living, colorful canvas. Vibrant, anarchic, and endlessly photogenic, Cadillac Ranch remains a must-stop for anyone seeking an American legend.

In Moriarty, you’ll find the last remaining Whiting Brothers service station still showing its original branding, a rare survivor from a once -widespread regional chain. Whiting Brothers was founded in 1926 by four siblings from Arizona and grew to operate over 100 roadside service points, motels, and truck stops across the Southwest, offering affordable fuel and traveler services as America’s road travel boomed. Station #72 in Moriarty opened in 1954 and stayed busy through decades of highway travel. When the family business dissolved in the 1980s as traffic shifted to interstates, long - time employee Sal Lucero bought the location in 1985, preserving the station’s classic look and name. Today, it no longer pumps gasoline but continues to serve motorists with repairs and maintenance, and its vintage signage was restored and relit in 2014 with help from preservation grants, making it a living link to mid - century roadside culture.

A Route 66 road trip is full of odd and unexpected stops, but few travelers are prepared for what awaits them at Stewart’s Petrified Wood in Holbrook. Opened in 1994 by Charles and Gazell Stewart, the shop lures travelers off the highway with a wild collection of DIY creations: towering metal dinosaurs, a T-Rex chomping on a mannequin, and even an old school bus turned into a roadside spectacle. The sculptures are wildly imperfect, yet that’s part of the charm: a little sketchy, a little wacky, and wholly unforgettable. Inside, polished 225-million-year-old petrified wood, sparkling geodes, and fossils bring the Triassic era to life. A small ostrich farm next door adds a modern twist. Stewart’s delivers a wonderfully offbeat Route 66 experience where imagination, history, and tenacity collide.

Now we come to one of the most famous destinations on the highway: The Jackrabbit Trading Post. After a short, bumpy drive off the main highway, down a cracked country road beside some railroad tracks, a huge yellow billboard declaring “HERE IT IS” pops up proudly, announcing your arrival in true kitschy Route 66 fashion. Opened in 1949 by Jim Taylor, who drove to Arizona with a rabbit statue in the back of his convertible that became the shop’s mascot, the trading post has welcomed travelers for generations. In 1961, Glenn Blansett took over, passing it to his family decades later. Today, Cindy Jaquez, Glenn’s granddaughter, and her husband, Tony, run the shop, preserving its playful charm. Shelves overflow with nostalgic memorabilia, gifts, and stories, while the iconic billboard and surrounding displays make it a must-stop on the Mother Road.

Elmer Long’s Bottle Tree Ranch, Oro Grande, CA

Just east of Barstow, where the Mojave stretches wide and quiet, Elmer Long’s Bottle Tree Ranch rises from the desert like a technicolor mirage. Created by longtime Route 66 resident Elmer Long using bottles collected by his father during cross-country trips in the 1930s and ’40s, the ranch is part folk art, part roadside rebellion. Hundreds of glass bottles — soda, medicine, and spirits — perch on steel “trees,” chiming softly when the desert wind blows. Over time, the site grew to include found-object sculptures, vintage signs, and sun-faded curiosities, all arranged with playful defiance against the emptiness around it. Equal parts memorial, art installation, and photo stop, Bottle Tree Ranch perfectly captures Route 66’s offbeat soul.

Cadiz Summit perches in the heart of the Mojave Desert, east of Chambless, where the old National Trails Highway crests the rugged terrain. Opened in the 1940s, it quickly became a bustling refuge for weary travelers, offering a service station, garage, café, and cabins for motorists braving the desert’s relentless sun and steep grades. By the early 1970s, with traffic diverted to Interstate 40, the stop fell silent, and the buildings slowly surrendered to wind and drifting sand. Today, only a handful of crumbling structures remain, leaning and weathered, their brickwork and wooden beams whispering stories of journeys long past. Walking among the ruins, visitors can almost feel the presence of travelers who once rested here, making Cadiz Summit a hauntingly beautiful, timeless monument to mid-century desert travel.

In the windswept Mojave Desert stands Roy’s, one of our favorite destinations and a timeless California beacon. It was first opened in 1938 by Roy Crowl, built to be a simple gas and service stop to welcome weary travelers. Over the years, however, it expanded into a full roadside oasis with a café, garage, and Googie - style motel. By 1959, a now iconic 50 -foot neon sign rose above the flat horizon, guiding adventurers from far away. Business was good for a time, but when Interstate 40 opened in 1972, traffic slowed and the neon fell dark. And so it sat, until, in 1995, entrepreneur Albert Okura purchased the property, and the whole town of Amboy, to preserve its heritage. Decades later, in November 2019, the legendary sign was lovingly relit. Its warm glow now bathes the quiet ruins, inviting visitors to wander, reflect, and fall in love with the spirit of classic highway travel once again.

ROUTE Magazine’s Picks for the Top Places to Stay Along the Mother Road

If you are beginning your Route 66 adventure in Chicago, as generations of travelers have before you, there’s no better place to stay than The Whitehall Hotel. It places you at the heart of the Windy City and just steps from the very beginning of America’s most legendary highway.

Located along The Magnificent Mile, this 1928 landmark blends Old World European style with the energy of one of the city’s most legendary corridors, once lined with mansions and now celebrated for its architecture, culture, and upscale shopping. The Whitehall opened during Chicago’s golden age, drawing actors, musicians, and tastemakers who favored its intimate scale and refined atmosphere. Even as the skyline modernized around it, The Whitehall held fast to its signature charm, becoming one of the Magnificent Mile’s longest-standing boutique hotels. Its recently refreshed rooms, handcrafted bedding, and beautifully maintained vintage elevator — a rare surviving touch of Chicago’s Jazz Age — all contribute to the quiet elegance of a property that has hosted nearly a century of Chicago stories.

Its location couldn’t be more fitting. You’re just a quick hop to the iconic “BEGIN ROUTE 66” sign on East Adams Street, Lou Mitchell’s — a Route 66 institution since 1923, and one of Route 66’s most beloved kickoff traditions — and the city’s lakefront energy. Whether you’re setting out on the first miles of Route 66 or savoring a final night before heading home, The Whitehall is a timeless bridge between the Mother Road’s beginnings and the adventures ahead.

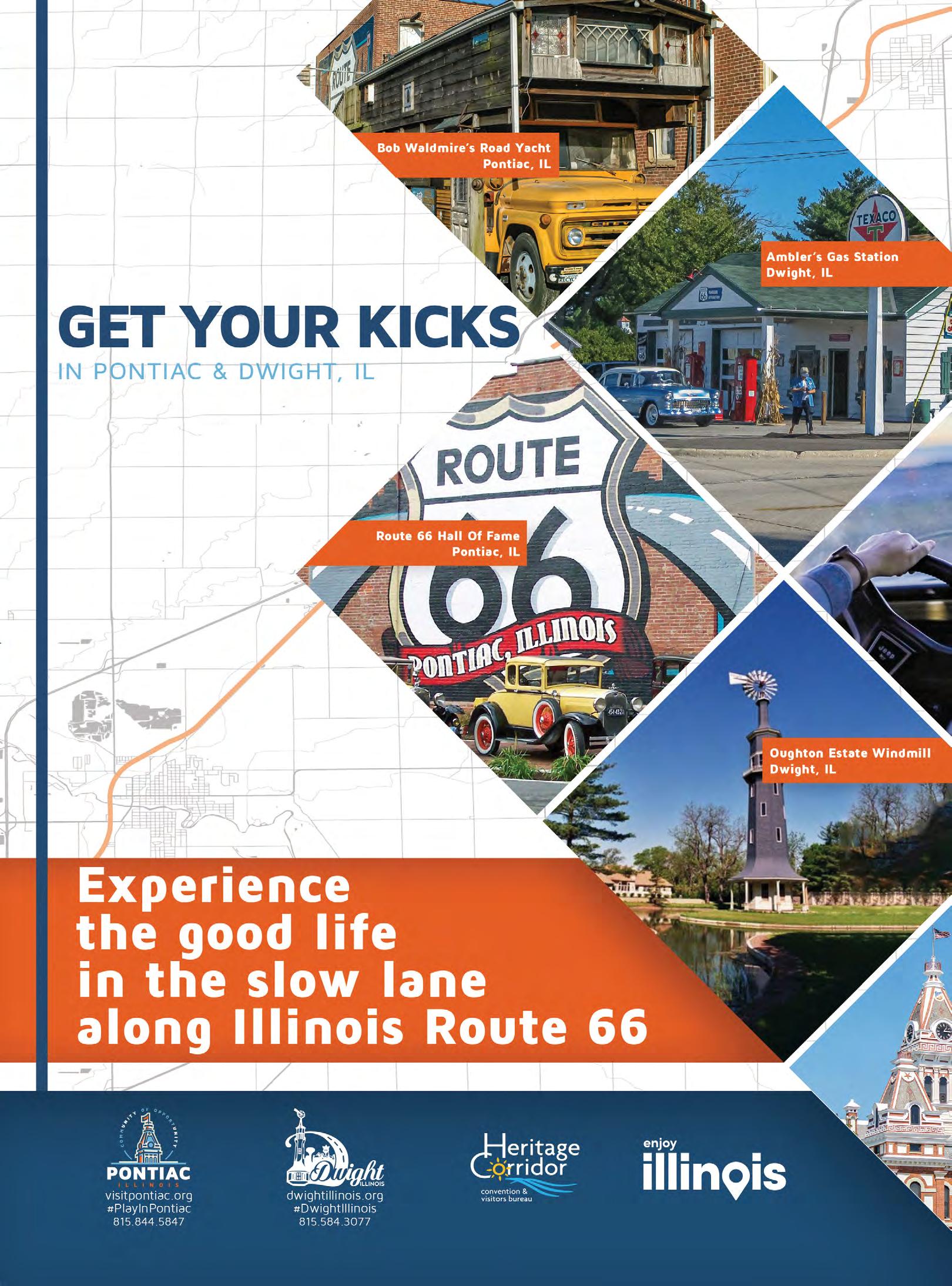

Just 100 miles southwest of Chicago’s iconic Route 66 “BEGIN” sign, Pontiac signals the moment when the Mother Road sheds its urban edges and truly opens into the heartland. This small Illinois city has become one of the highway’s most beloved early stops, an energetic mix of Americana and Midwest hospitality.

Pontiac wears its history proudly. The town is home to nine Route 66-related museums and exhibits, including the Illinois Route 66 Hall of Fame and Museum, the Pontiac-Oakland Automobile Museum, and the Livingston County War Museum, as well as more than 25 outdoor murals that turn its walkable downtown into an open-air gallery. You can take a self-guided walking tour, pose before the World’s Largest Route 66 Painted Shield, and/or embark on a family-friendly scavenger hunt to spot all 15 miniature vintage cars tucked around the city. It’s a stop that more than earns an overnight stay, and the Hampton Inn makes staying in town effortless.

Opened in 2017, the hotel greets guests with a lobby that celebrates the spirit of Route 66, complete with memorabilia, vintage signage, and road-trip inspired artwork. Beyond the lobby, spacious, plush rooms incorporate modern convenience: HDTVs, mini-fridges, and microwaves, while an indoor pool and fitness center offer ways to unwind after a day on the road. Before heading west again, a complimentary hot breakfast, including make-your-own waffles, keeps bellies (and hearts!) full for the next hundred miles.

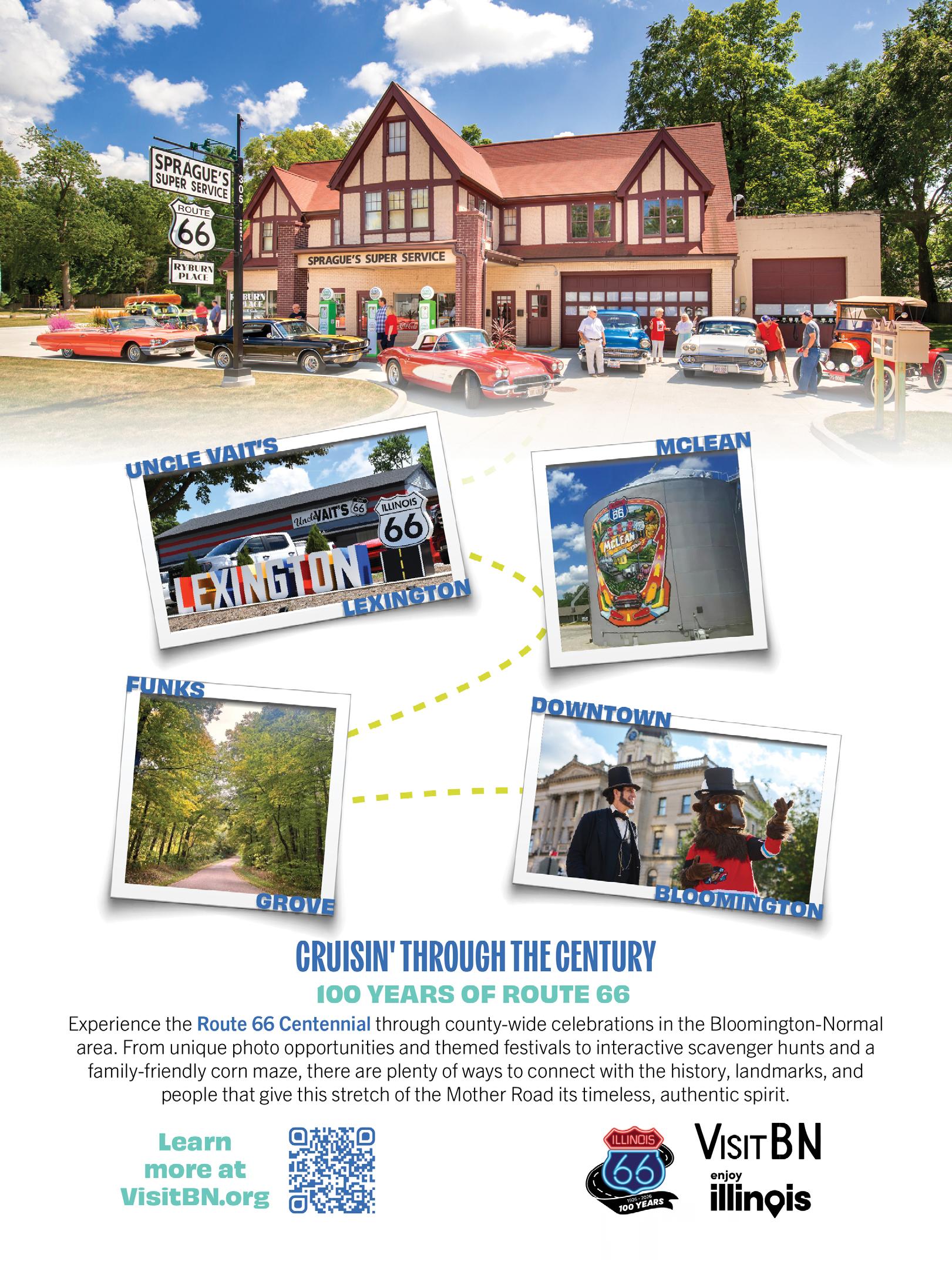

From the Cruisin’ with Lincoln on 66 Visitors Center at the McLean County Museum of History, which celebrates both Route 66 and Abraham Lincoln, to the Sprague Super Service Station, a 1930s Tudor Revival station preserving old-time Americana, to a stroll through downtown’s historic architecture, murals, and small shops, Bloomington offers a rich tapestry of history, local culture, and Lincoln lore—a stop you won’t want to rush. From Bloomington, it’s also easy to explore other Route 66 towns and attractions such as the Dixie Travel Plaza in McLean, Funks Maple Syrup in Shirley, and tiny Atlanta, Illinois, adding even more small-town charm to your journey.

So, it helps to have a comfortable base, and the recently renovated DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel Bloomington fits the bill perfectly. Guests are greeted with the irresistible aroma of freshly baked chocolate-chip cookies — a signature complimentary treat — and pleasant rooms equipped with mini-fridges, coffee makers, and 50” flat-screen TVs.

After a day of exploring, a dip in the indoor pool or a soak in the hot tub restores energy, and the Brickyard Bar offers cocktails, local specials, and live music on Tuesday nights, the perfect way to close out the day. Pet-friendly rooms make it easy to bring the whole crew along. In the morning, a hearty buffet breakfast provides the fuel you need before heading back out, whether that means strolling a stretch of old Route 66, visiting other nearby significant sites like the David Davis Mansion, or continuing westward along the Mother Road.

A night at the Bressmer-Baker House isn’t just a stay, it’s an invitation to live like Gilded Age royalty. Sink into the red velvet cushions of a cabriole sofa, catch your reflection in a gold-trimmed mirror set against floral wallpaper, or watch the pendulum swing as the grandfather clock chimes. Every detail of this 5,500-square-foot home, from its domed turret to intricate woodwork, evokes an era of ambition and elegance.

Built in 1853 by real estate dealer Hiram Walker, the house was purchased in 1855 by dry goods merchant John Bressmer, who hired architect Thomas Dennis to expand it into a three-story home for his wife, Mary Weiss, and their four children. Bressmer, a German immigrant who arrived in Springfield at 15, knew little English and even less about American customs. His remarkable journey from immigrant laborer to successful businessman makes the Bressmer-Baker House more than just a historic building; it’s an embodiment of the American dream.

In 1889, William B. Baker remodeled the home into its Queen Anne splendor, and in 2021, business partners James Lucas and Ben Bledsoe restored it as a private retreat. Set just off Route 66 and steps from Lincoln’s Home, the Presidential Library, and the Illinois State Capitol, the house now features nine bedrooms and six bathrooms across three floors, complete with full kitchens and convenient laundry facilities. Guests can rent a full level or the entire home, making every stay as personal — and unforgettable — as the history that surrounds it.

Chase Park Plaza Hotel, St. Louis, MO

Few places in St. Louis — the “Gateway to the West” — capture the city’s allure and rich history quite like the Chase Park Plaza Hotel. Located along Lindell Boulevard, once a Route 66 alignment, this hotel has welcomed guests since the early days of the Mother Road.

It began as two rival properties: the nine-story Chase Hotel, opened in 1922 by attorney Chase Ulman, and the 27-story Park Plaza, built by Sam Koplar in 1929. Their competition sparked innovation: elegant ballrooms, rooftop dancing on the famous Starlight Roof, and one of the area’s first outdoor pools. By the 1950s and ’60s, the Chase Club became the epicenter of St. Louis entertainment, hosting Frank Sinatra, the Rolling Stones, and Elvis Presley. If its century-old walls could talk, they’d whisper Rat Pack secrets, Hollywood starlets’ glitzy tales, and rock & roll legends’ late-night antics.

Although both properties were acquired by the Koplars in 1947, they remained separate until 1961, when they were joined to form a single iconic landmark filled with shops, dining rooms, and an espresso room, a touch of New York glamour in the Midwest.

Today, under Royal Sonesta International Hotels, it retains its “city within a city” character. The grand lobby, stonecarved porticoes, and Mediterranean-style pool framed by marble columns evoke past romance, while lavish amenities, including an 18,000-square-foot Santé Fitness facility, spa, three restaurants, and the Chase Park Plaza Cinemas, seamlessly blend history with contemporary luxury. A stay here is a chance to experience St. Louis like a star.

The Wagon Wheel Motel, Cuba, MO Cuba, Missouri, famously known as the “Route 66 Mural City,” is a celebrated stop along the Mother Road. Its streets are lined with more than 20 large-scale murals depicting Route 66 history, local culture, and mid-century Americana, making the town a living showcase of the highway’s legacy.

At the heart of Cuba stands the Wagon Wheel Motel, a Route 66 icon welcoming travelers since 1936. Originally opened by Robert and Margaret Martin as the Wagon Wheel Cafe, with an adjacent gas station, the property expanded in 1938 with 14 Tudor Revival-style cottages built from Ozark stone by stonemason Leo Friesenhan. By 1939, their steeply pitched roofs, elegant trim, and eclectic stonework earned them AAA praise as “a home away from home.” In 1947, John Mathis, the motel’s second owner, added the neon sign featuring the iconic wagon wheel that still attracts travelers from across the country.

Over the decades, the motel changed hands and weathered a period of decline until 2009, when Connie Echols undertook restoration, preserving its endearing character while enhancing the guest experience. Today, checking into the Wagon Wheel is like stepping into a time capsule. The rooms, with vintage fittings and thoughtful touches — flat-screen TVs, Wi-Fi, and in-room coffee makers — blend nostalgia with tranquility.

As night falls and the original neon sign flickers to life in red and yellow, casting a warm glow over the Mother Road, you know you are amid the living echoes of a storied past.

Springfield, Missouri, celebrated as the “Birthplace of Route 66,” is where the iconic Chicago-to-Los Angeles highway was first numbered in April 1926 and federally designated that November. At the heart of this historic city stands Hotel Vandivort.

Housed in a four-story, 40,000-squarefoot brick building constructed in 1906, the property served as a Masonic temple for more than 75 years. During the 1980s corporate boom, it was converted into offices until brothers and local entrepreneurs John and Billy McQueary purchased and restored it in 2012.

Careful preservation of cast-iron pillars, exposed brick walls, and subtle Masonic details maintained the building’s turnof-the-century character. In 2019, they expanded just steps away with V2, a sleek 44,000-square-foot sister property with nods to the building’s illustrious past.

Rooms at the Vandivort and V2 combine industrial edge and Art Deco style with Springfield artistry. Floor-toceiling windows, vintage vinyl, and geometric tiles set the tone, while plush bedding, robes, and smart lighting deliver boutique comfort.

Just steps from Springfield’s Historic Square, the History Museum on the Square, the Gillioz Theatre, and enchanting downtown shops and eateries, the hotel places you at the center of the city where Route 66 was first numbered. Evenings are best spent at the Vantage Rooftop Lounge and Conservatory, where handcrafted cocktails, fresh oysters, and panoramic views of downtown and the distant Ozarks set the scene. Listen as the 171-year-old bell tolls at sunset, a reminder of Springfield’s romantic journey.

When you picture the archetypal Route 66 motel, it likely resembles Boots Court in small town Carthage, perched at the crossroads of historic Route 66 and U.S. 71, the Jefferson Highway.

During the 1930s, entrepreneur Arthur Boots operated a small filling station, Red Horse Service Station, at the so-called “Crossroads of America.” Inspired by his older brother, Loyd, who owned a motel elsewhere, Arthur and his wife Ilda opened their own roadside venue in 1939, using the Red Horse as the front office. And thus, Boots Court was born. The eight-room motel debuted in the sleek Streamline Moderne style, with carport parking beside each unit. At a hefty $2.50 per night, the motel offered one of the era’s rare conveniences: a radio in every room.

By 1946, new owners Ples and Grace Neeley expanded with five additional rooms. Over the decades, as Route 66 evolved and was eventually decommissioned, Boots Court weathered ownership shifts, renovations, and even the threat of demolition. By 2011, it was named one of the ten most endangered roadside attractions in America, inspiring sisters Deborah Harvey and Priscilla Bledsaw to purchase it and begin restoring it to its original 1940s charm. A decade later, the Boots Court Foundation completed the meticulous restoration.

Today, Boots Court Motel is a preserved gem of mid-century Americana. Its 13 unique rooms feature vintage chenille blankets, radios that play classic oldies, and beautiful glowing green neon tracing its perimeter, inviting you to step back in time. While here, explore the beloved 1949 66 Drive-In Theatre, one of the last remaining drive-ins still operating along Route 66, the Carthage Civil War Museum, and the captivating “town” of Red Oak II.

The Campbell Hotel, Tulsa, OK

No Route 66 road trip is complete without a stop in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the self-proclaimed “capital” of the Mother Road. If staying right on historic Route 66 is the goal, the Campbell Hotel is a top pick. Located on East 11th Street, it combines historic flair, blissful relaxation, and a front-row seat to Tulsa’s Mother Road revival.

Built in 1927 by Max Campbell, the building originally housed the Casa Loma Hotel upstairs, offering 30 modest rooms with shared bathrooms, while the street level featured retail shops. However, the oil bust of the 1980s, combined with traffic diverted onto new freeways, left East 11th Street in decline. By the late 2000s, the Campbell stood vacant and decaying, deemed beyond repair, with whispers of demolition circulating.

Then, Tulsa native Aaron Meek purchased the property in 2008 and led a careful three-year restoration, preserving its timeless character while transforming it into a boutique destination. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2010, it reopened in 2011 as the Campbell Hotel with 26 uniquely themed rooms, a cozy lounge, and a fitness center.

Staying at the Campbell means you don’t just sleep in history, you live it. The S.E. Hinton Room dazzles with a Spanish-style cupola and crystal chandelier; the Oil Barons Room evokes Tulsa’s oil-boom legacy; and the Route 66 Suite glimmers with a stone faux fireplace and vintage gas-station accents. Step outside, and the neon Meadow Gold sign, Buck Atom’s Cosmic Curios, and larger-than-life Muffler Men await.

This year, another Tulsa hotel makes our list. The Mayo Hotel offers a different kind of historic elegance: a grand downtown icon with soaring ceilings, sophisticated decor, and a captivating past. Inspired by a visit to New York City, entrepreneur John Mayo vowed to build a hotel that could rival the grandeur of the Plaza. In 1925, he and his brother Cass, in collaboration with architect George Winkler, unveiled an Art Deco masterpiece boasting 600 luxurious rooms and the most current amenities of the era. The Mayo quickly became Tulsa’s social epicenter, hosting oil tycoons, politicians, and celebrities, including Elvis Presley, Lucille Ball, and Charlie Chaplin. It is even rumored to have served Tulsa’s first legal post-Prohibition drink, adding to its beguiling lore.

After decades of prestige, including being listed on the National Register of Historical Places in 1980, the hotel closed in 1981 and slowly fell into disrepair. A new chapter began in 2001 when the Snyder family purchased and meticulously restored the property. Reopened in 2009, the Mayo now dazzles with its Kubrickesque lobby, refined Art Deco details, and modern luxury, while preserving its signature grandeur. The rooftop Penthouse Bar, formerly the Presidential Suite, offers sweeping views of downtown Tulsa and the Arkansas River.

Staying here places you at the heart of the city’s history and culture. Walk among downtown’s Art Deco architecture, catch a show at Cain’s Ballroom, explore the Philbrook Museum of Art, or visit the Woody Guthrie Center, all minutes from your door, fusing the past and present in a quintessential Tulsa experience.

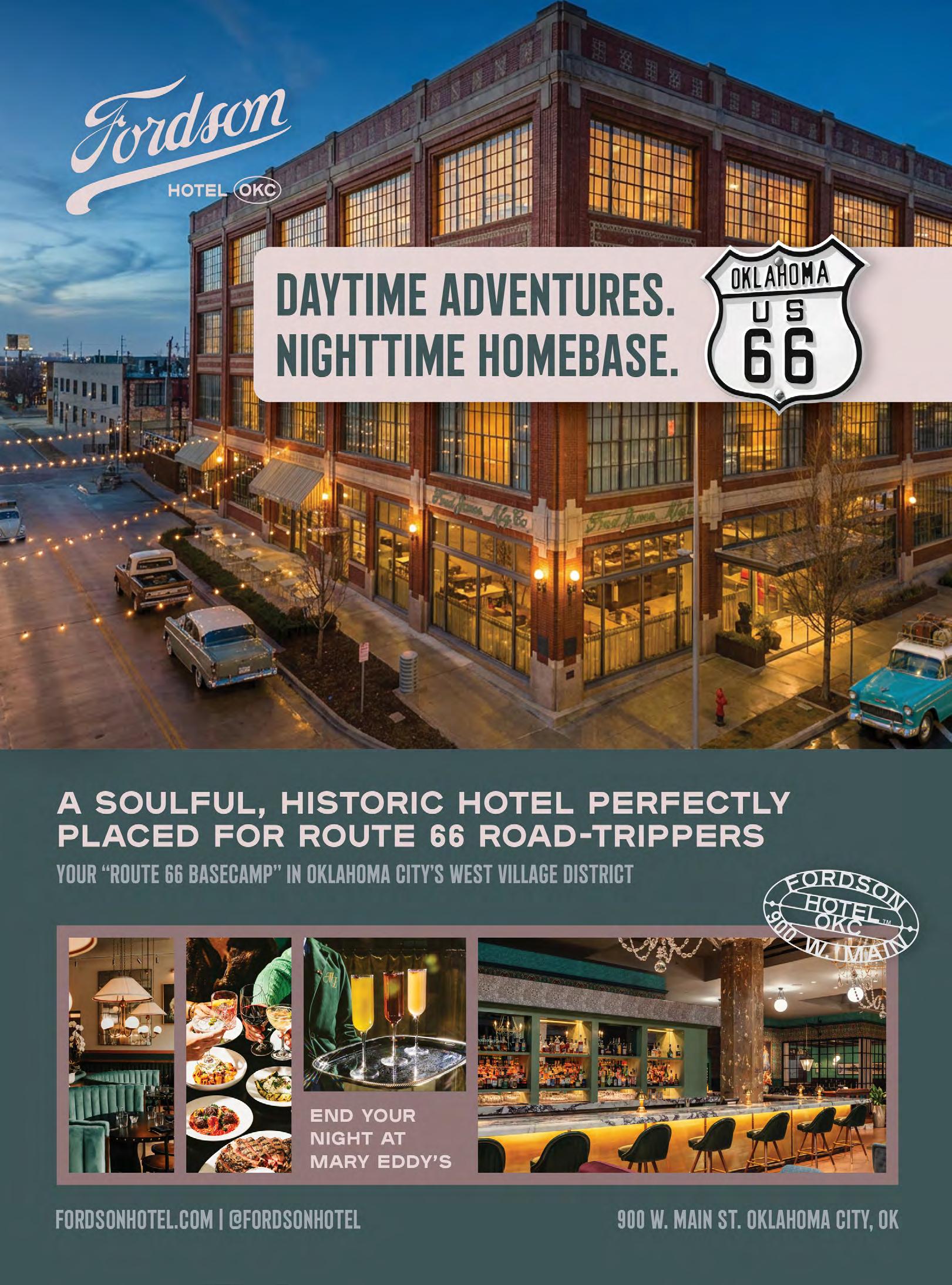

Fordson Hotel, Oklahoma City, OK

Oklahoma City offers its own kind of Mother Road mystique, where classic Route 66 landmarks such as the Tower Theatre, Will Rogers Theatre, the Milk Bottle building, the Gold Dome, and the State Capitol (one of only two state capitols on historic Route 66) dot the cityscape. Beyond its iconic architecture, OKC carries a rich automotive legacy, a history nowhere more tangible or inviting than at the Fordson Hotel.

The Fordson’s story reflects the spirit of Oklahoma City itself. Built in 1916 by industrial architect Albert Kahn as a Ford Model T assembly plant, it helped shape the car that would revolutionize America. During the Depression, the plant became a Ford parts depot until 1968, when former employee Fred Jones purchased the building, turning it into one of the world’s largest Ford dealerships. Decades later, in 2016, it was reborn as a 21c Museum Hotel, and in 2023, it was rebranded as the Fordson Hotel under Hyatt, proudly leaning into its history.

A vintage Model T, a nod to the building’s automotive wells flood the space with natural sunlight, preserving its architectural character. The 135 loft-style rooms and suites feature high ceilings, expansive steel windows, custom furnishings, and sophisticated touches that harmonize effortlessly with the building’s industrial character. With three on-site dining venues, a spa, fitness center, valet service, and a complimentary shuttle to downtown attractions, the Fordson offers everything needed to linger and savor Oklahoma City’s unique brand of Route 66 magic.

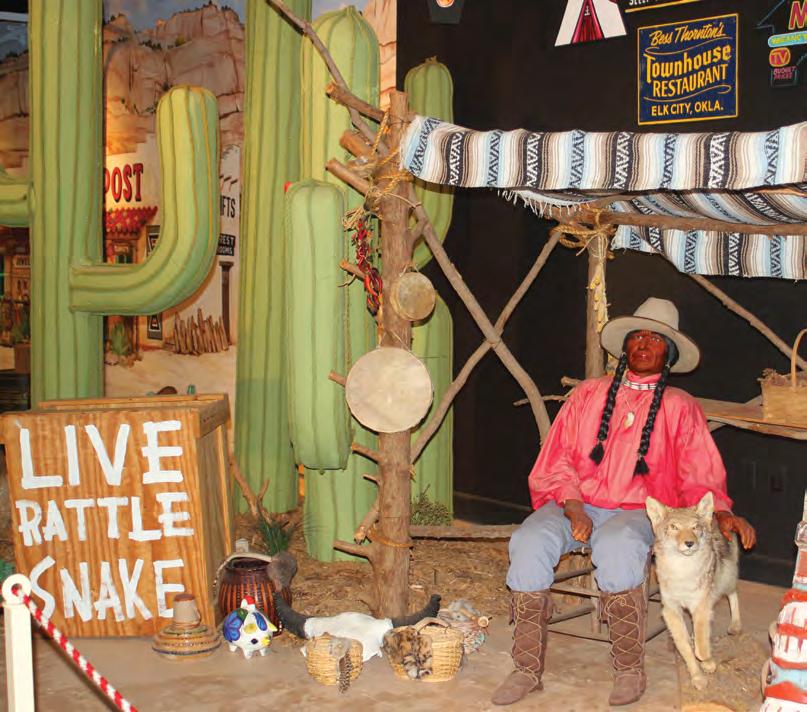

Small but worth a stopover, Elk City brings the spirit of Route 66 to life, making it a rewarding stop along the Mother Road. Known as the “Queen of the West,” this 15-square-mile town has been serving up Oklahoma hospitality since 1901, first as Crowe, then briefly as Busch, in an attempt to lure brewing magnate Adolphus Busch, before finally taking the name Elk City in 1907 from the winding Elk Creek that runs through it.

At the heart of Elk City’s Route 66 appeal is the National Route 66 & Transportation Museum and the associated Old Town Museum, both part of the local museum complex. Together, they offer an immersive journey through America’s highway heritage, tracing the road’s evolution from pioneer wagons to chrome-trimmed hot rods. Exhibits recreate scenes from roadside motels, drive

For an overnight stay, the fourstory Holiday Inn Express & Suites is a natural choice. Originally built in 2012, the property has undergone thoughtful renovations in 2021 and 2023, ensuring that every guest enjoys a fresh, delightful stay with updated rooms and amenities. Each room features a 37” multimedia flatscreen, microwave, mini-fridge, and plush pillow-top beds with triple sheets, along with roomy work desks for travelers on the go. Suites add a separate living area, kitchenette, and sofa bed—perfect for families. Kids will love the quaint indoor water park, and adults might find themselves splashing along too. Mornings start with a complimentary breakfast to fuel the day ahead, making it easy to hit the road refreshed.

The Barfield, Autograph Collection, Amarillo, TX

You can’t drive Route 66 without stopping in Amarillo. From the quirky spectacle of Cadillac Ranch, to the legendary Big Texan Steak Ranch, to the Historic Route 66 District and the scenic Palo Duro Canyon State Park, the city serves up the perfect mix of Western charisma, quirky Americana, and wide-open Texas skies.

And when it comes to staying the night, The Barfield is Amarillo’s crown jewel. Standing proudly at the intersection of Historic Route 66 and Polk Street, this ten-story landmark was built in 1927 as the Oliver-Eakle Building by local luminary Melissa Dora Oliver-Eakle. Known as “The Duchess” for her generosity — she even opened the city’s first library — Oliver-Eakle imbued the building with character, including a secret Prohibition-era speakeasy tucked in the basement: the Paramount Recreation Club. Over the decades, the building weathered economic shifts, was renamed the Barfield Building, and sat vacant for thirty years, until 2021, when new owners transformed it into a 112-room hotel in Marriott’s Autograph Collection. Today, The Barfield effortlessly marries historic elegance with 21st Century polish. Guest rooms are sleek and smoky, featuring charcoal walls, West Texas–inspired decor, and wooden sliding doors; Texan through and through, with an air as smooth as a sip of a smoked Old Fashioned. The revived Paramount Recreation Club brings Amarillo’s roaring twenties to life. Leather booths, sunset-hued Aztec blankets, and an authentic vintage cigarette machine make it feel as though you’ve stepped onto the set of Yellowstone. This place will appeal to your inner cowboy and then some.

The Roadrunner Lodge Motel is your passport straight back to the swinging ‘60s, where neon signs flicker, vintage vibes reign, and every detail celebrates an era when the American road trip was pure romance.

This groovy motel is a mash-up of two neighboring properties. La Plaza Court first opened in 1947 as a motor court, complete with garages beside each unit, and in 1964, Agnes Leatherwood built Leatherwood Manor next door. The motels ran independently for about twenty years until a new owner merged them in 1985. Over the years, the motel went by several names until David and Amanda Brenner purchased it in 2014, restoring it as the Roadrunner Lodge Motel, which serves its visitors with 1960s retro flair.

Step into your room and nostalgia kicks in immediately. The Brenners created a short-range FM station that loops ‘60s hits and vintage-style ads. Moon Pies sit on tables, retro magazines await reading as if Lyndon B. Johnson were still president, and some rooms feature Magic Fingers vibrating beds. Just bring a quarter. Decor ranges from Polynesian tiki flair to Googieinspired murals, turning every room into a mini time capsule.

Step outside, and Tucumcari has plenty to keep you busy.

Stroll Historic Main Street, get a prehistoric thrill at the Mesalands Dinosaur Museum, visit the Tee Pee Curios trading post, and take in the glow of Tucumcari’s Neon Trail. Back at the motel, evenings are for swapping road stories with other guests around the fire pit. A petfriendly motel keeping the ‘60s alive? We can dig it.

La Fonda, Santa Fe, NM

La Fonda on the Plaza isn’t just a hotel, it’s a portal to New Mexico’s rich history, vibrant culture, and the romance of the open road. Before Route 66 was redirected in 1937, the highway followed a northern detour along the Old Pecos Trail, passing directly in front of La Fonda, placing the hotel on one of the most storied stretches of early American travel. Staying here, you retrace that original pathway, where the true story of Route 66 and the city’s Southwest magic intersect.

La Fonda’s story stretches back to 1607, long before New Mexico became a state, when the town’s first inn, or “fonda,” opened on this site. The current hotel, built between 1919 and 1922 by architect Isaac Rapp, known as the “Creator of the Santa Fe Style,” features stained glass skylights, hand-carved wooden beams, and terracotta floors that echo both Santa Fe’s Spanish Catholic roots and the desert’s burnt orange landscape. By 1925, La Fonda became a Harvey House, where Mary Colter infused Native American motifs and works by local artists, creating the hotel’s signature cultural flair.

Today, under siblings Jennifer Kimball and Phillip Wise, who purchased La Fonda in 2014, the hotel adorns rugged charm with splendor. Renovations updated nearly every corner, including the Terrace Inn—a “hotel within a hotel” with 15 suites overlooking the Cathedral Basilica and Loretto Chapel. Step outside, and Santa Fe unfolds at your feet: The historic Plaza, the Palace of the Governors, and galleries of Canyon Road are all within easy walking distance.

When Route 66 was realigned in 1937 to follow an east-west path through Albuquerque, Central Avenue came alive, a dazzling 18-mile stretch of neon signs, motels, diners, and roadside attractions that cemented Albuquerque’s place on America’s Main Street. In 1939, Conrad Hilton built his first hotel outside Texas, choosing a spot just steps from Central Avenue. True to his belief that each hotel should be unique, this landmark instantly stood out.

At ten stories, it was the tallest hotel in New Mexico, the first with an elevator, and the first fully air-conditioned. From its architecture to its interiors, it drew inspiration from the Andalusian region of southern Spain, infusing Spanish-Moroccan and Moorish influences into a distinctive Southwestern style. The Hilton name remained until 1969, then the property cycled through several owners and identities. In 2008, it was reborn as Hotel Andaluz, reopening in 2009 with a restored design that honored its heritage and earned a rare Gold LEED certification. A decade later, it came full circle, rejoining the Hilton family under the Curio Collection.

Inside, the lobby melds 1930s grandeur with boutique elegance, featuring wide archways and a dramatic two-story space framed with carved wood trim and a restored mosaic fountain, reminiscent of an Old-World courtyard. Intimate alcove-style “Casbahs” offer intimate seating for cocktails or conversation, while guest rooms continue the Spanish-Moorish aesthetic with earthy tones, wood, and stone. Outside, Route 66 comes alive, from the Pueblo-Deco KiMo Theatre to classics like the Dog House Drive-In, and so much more.

Located directly on Route 66 and steps away from Albuquerque’s vibrant Old Town, the El Vado Motel offers a rare combination of nostalgia, culture, and convenience that makes it a standout choice. Wander cobblestone streets lined with adobe buildings, browse artisan shops, and savor Southwestern cuisine, then retreat to the retro world of El Vado.

Built in 1937 by Irish immigrant Daniel Murphy, with stucco walls, exposed vigas, and carports for every room, the 22-room motel stood out as a distinctive stop along America’s Main Street. A glowing neon sign, depicting a Native American man in a colorful headdress beneath a radiant starburst, beckoned road-weary travelers.

But as the wheels of progress turned, El Vado witnessed the shifting landscapes of Albuquerque and Route 66. Over the years, it fell on hard times, changed hands multiple times, and gradually slipped into disrepair. By the early 2000s, the motel faced the looming threat of demolition. A decade of inactivity and legal uncertainty left its future in limbo, that is, until 2018, when Chad Rennaker and Palindrome Properties of Portland, Oregon, stepped in with an $18 million restoration and a second chance at life.

Today, the iconic neon sign glows anew. Expanded rooms, named after classic cars like Hudson, DeSoto, and Packard, offer modern amenities, while the courtyard, once a hub for road-weary travelers, has been revitalized into a lively gathering space with a plunge swimming pool, numerous food pods, and inviting seating areas where the spirit of Route 66 and the energy of Old Town Albuquerque come vividly to life.

As the largest town between Albuquerque and Flagstaff, Gallup has long served as a gateway to Native American culture and the rich heritage of the Southwest. Beyond its fascinating roots, though, Gallup invites exploration: wander through Historic Downtown, visit the iconic Richardson Trading Post, and if your visit falls in July, experience the Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial. And no visit is complete without staying at the legendary El Rancho Hotel.

Built in 1936 by movie theater tycoon R.E. Griffith, the hotel was designed by architect Jack Corgan to fit in seamlessly with the rugged landscape. Step inside, and the lobby captivates: an oversized fireplace, sweeping curved staircases draped red carpet, and hand-hewn beams evoke the spirit of the Old West. Yet at El Rancho, the red carpet rolled out in more ways than one.

During Hollywood’s Golden Age, stars like Katherine Hepburn, Gregory Peck, Robert Mitchum, and the ultimate cowboy, John Wayne, called El Rancho home while filming in the region. However, as the popularity of Westerns, and then of Route 66 itself waned, the hotel gradually lost its appeal, falling into neglect and facing the threat of demolition.

But in 1986, Armand Ortega, owner of a Navajo trading post, thankfully, restored the property, earning it a spot on the National Register of Historic Places. Today, his grandson Shane Ortega has completed a major renovation, adding to the hotel’s glamorous Hollywood past with contemporary comfort. At El Rancho, history, Hollywood, and the open road converge, making a stay an unforgettable chapter of your Route 66 adventure.

La Posada, Winslow, AZ

Winslow, Arizona, is one of those Route 66 towns that demands an overnight stop. Perhaps most famous for its Standin’ on the Corner park — immortalized in the Eagles’ 1970s hit Take It Easy — the town offers so much more. At the heart of this iconic little town is the legendary La Posada Hotel.