August/September 2024

August/September 2024

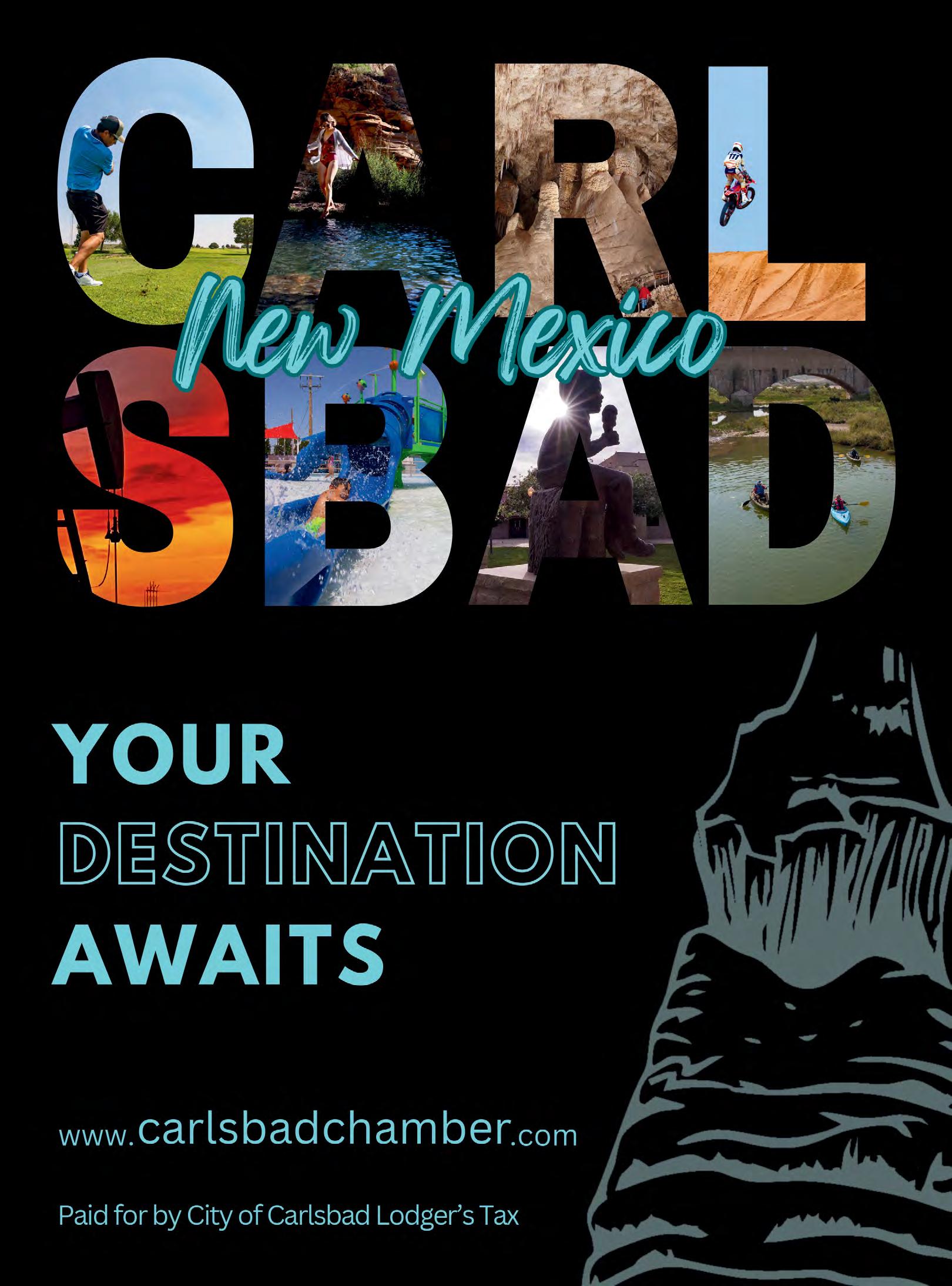

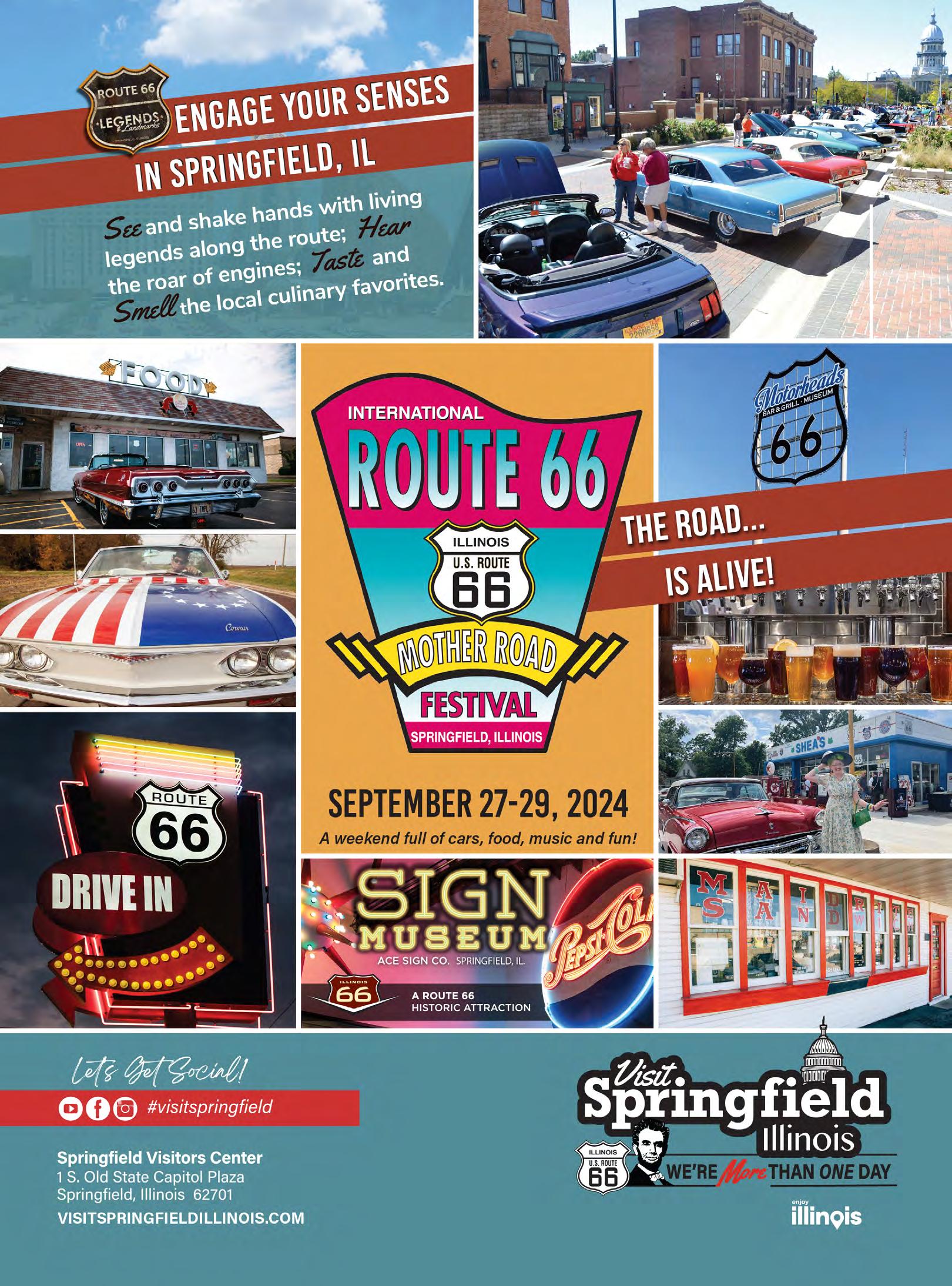

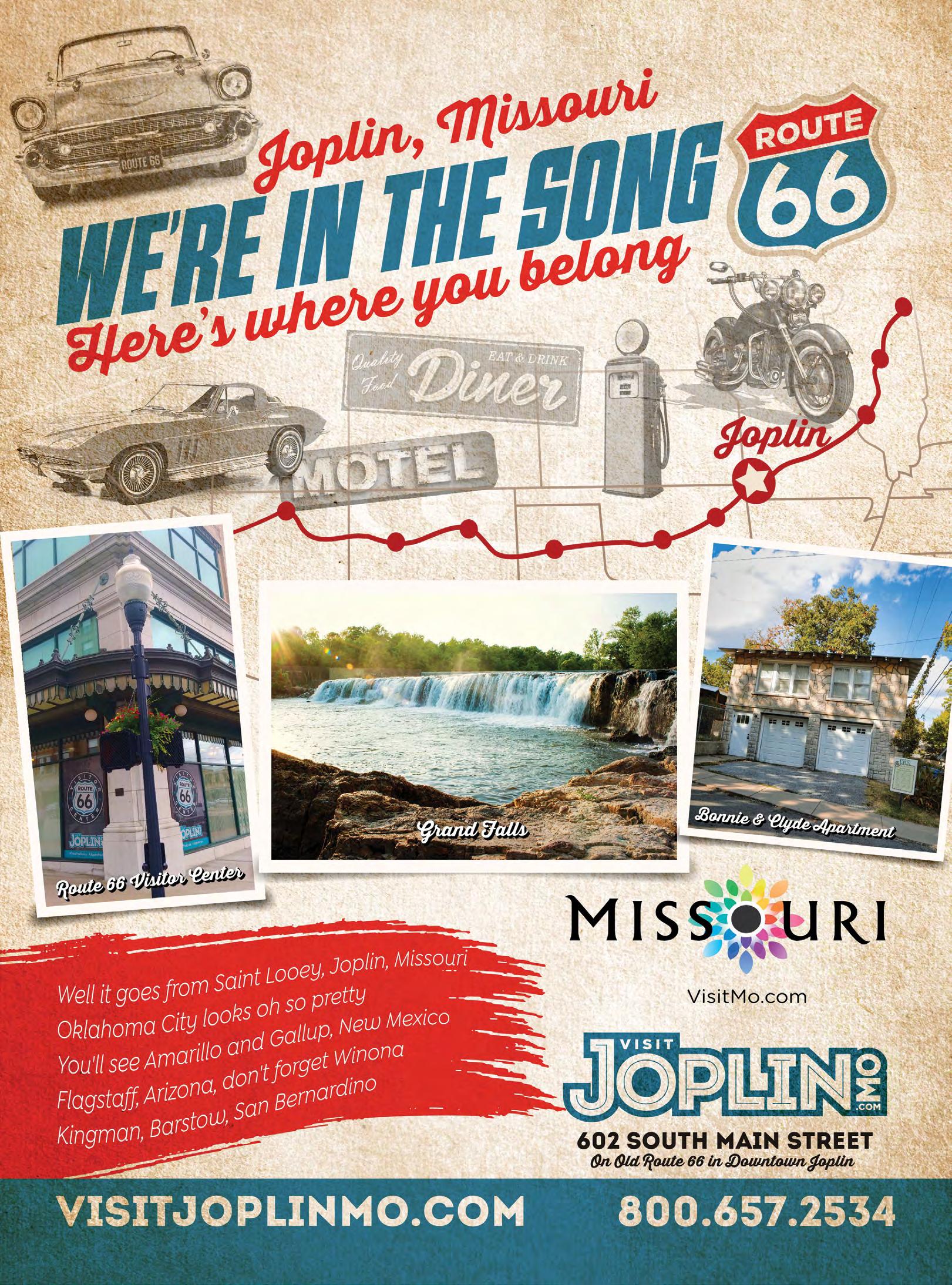

Whether it’s classic cars, old-fashioned burgers or a museum that brings history to life, you can relive the glory days of Route 66 in its birthplace. Get extra “kicks” at the Birthplace of Route 66 Festival, August 8-10, 2024. We love our city and know the best places to eat, drink and play.

Discover Oklahoma City’s vibrant districts with colorful murals and retro neon that make Route 66 fun by day or night. Our world-class museums and only-in-OKC experiences will ignite memories for a lifetime. Start your journey at VisitOKC.com.

39thStreetDistrict

Uptown23rdDistrict

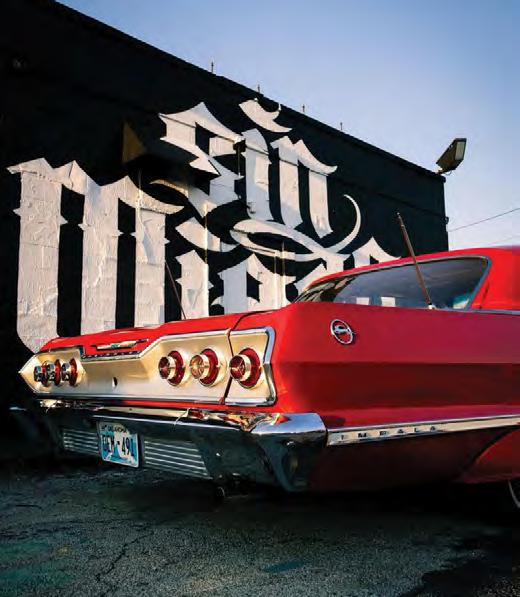

Explore the vast cultures and cuisines of East Tulsa. Peppered in between vintage motels and graffiti murals are 10+ vintage shops filled with eclectic treasures. Local Rec – Stop by Fire Station 66 where the “Keepers of the Mother Road” have on display a vintage fire truck they’ve restored!

Don’t Miss the Capital of Route 66 ®

West on 66, pull over for classic Oklahoma cuisine, art studios and galleries, Route 66 landmarks, and public art celebrating Oklahoma and indigenous histories. Local Rec – If you’re looking to get hitched on 66, pop in to Route 66 Weddings and say I do!

Discover a new Post Card Mural Trail, a giant pink elephant, the world’s tallest catsup bottle water tower, giant monuments and more along the Last 100 Miles of Route 66 in Illinois. Legends live on this legendary highway. Learn more at riversandroutes.com

By Aaron Garza

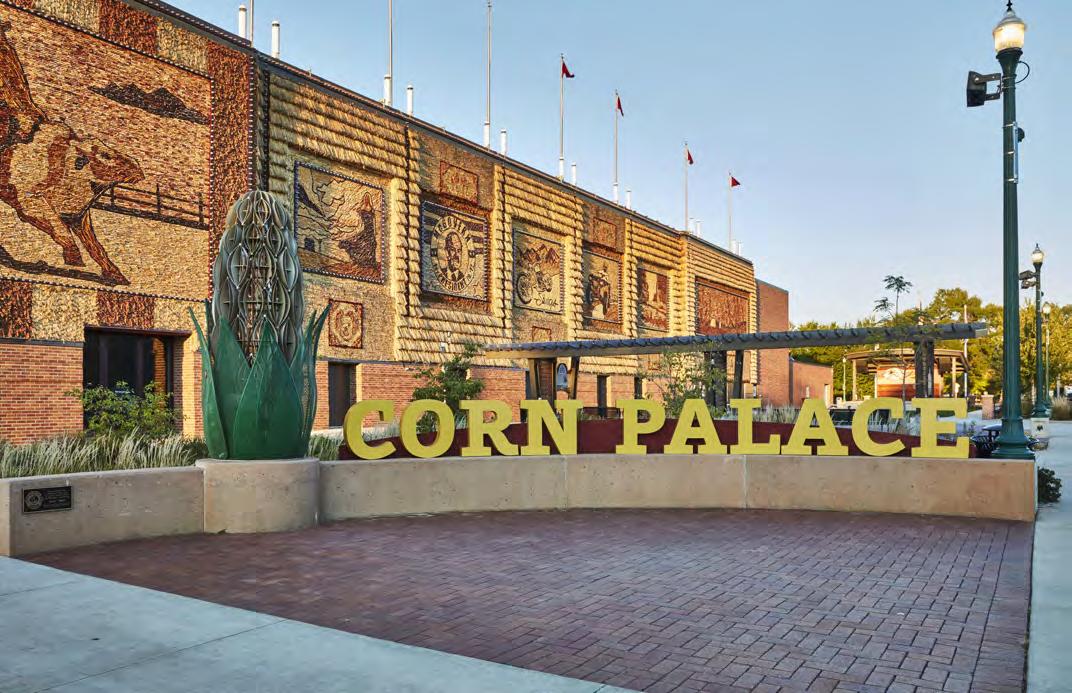

America is nothing if not quirky. Need a good example? Look no further than to Mitchell, South Dakota, and an odd destination known, unsurprisingly, as The World’s Only Corn Palace. This building was created to honor and promote the agricultural prosperity of South Dakota, and the massive, rough walls that have preserved the Corn Palace for decades have stood since 1892. The folk-art exhibits and murals are part of the palace’s redecoration with naturally colored corn and grains. This is one iconic piece of architecture that can truly only exist in America.

By Cheryl Eichar Jett

While Route 66 has attractions and advertisements that can be seen from far and wide, on the dusty plains of Groom, Texas, stands a white, free-standing, 19-story cross that can be seen from 20 miles away. This beacon of hope is located just off Route 66 and reminds us of the importance of the Christian faith and the preservation of its force in Carson County. Over time, the attraction has grown and diversified, but its simple, beautiful message of faith and hope has changed very little.

By Brennen Matthews

Arguably one of the most iconic musicians of the 1980s, Huey Lewis is still a powerhouse in the lives and hearts of millions. From his first band, Clover, to the multi-platinum selling album Sports, and his pivotal part in the mega hit single, “We Are

the World,” Huey Lewis has awed audiences with his original singer/songwriting talent and his ability to write some of the most catchy tunes of the Decade of Excess. In this conversation, he retells the whirlwind of discovering his talents, passion for music, what he is doing nowadays, and so much more.

Tucked amongst the towering, ancient redwood forests of northern California, is the quaint, enchanting resort of the Benbow Historic Inn. This luxurious, Swiss-like venue, located near the Avenue of Giants, contains décor from the 1920s, offers hiking trails, and boating in the Eel River. It also creates an unexpected vibe that easily transports visitors back to a more elegant time in a very surreal place. But the cherished inn was almost not to be. Numerous times. Its journey is one that is as Old-World American as the hotel itself.

Cadillac Ranch, Amarillo, TX. Photograph by Katy Pair.

America, the Land of the Free, is incredible for so many reasons, but one of the most notable is the country’s sheer number of quirky roadside attractions. There are decades of funky, downright bizarre stops along America’s highways that still scream out to passing motorists, urging them to slow down and take a break while they discover the country.

This tradition of roadside attractions began in the early 20th Century, fueled by the rise of the automobile and the burgeoning culture of road trips. Entrepreneurs and towns across the nation seized the opportunity to create unconventional and often whimsical stops that provided both entertainment and a much-needed respite from the journey. These attractions often reflected the local culture, history, and pure imagination of their creators.

From iconic Route 66, peppered with vintage motels and neon signs, to hidden gems like the World’s Largest Ball of Twine in Kansas, these landmarks are more than mere pit stops; they are destinations that capture the essence of American ingenuity and nostalgia.

In this annual issue, we celebrate vintage Americana and bring you a curated selection of unusual stories from across the country that tell a tale of a time when America was not only a simpler place, but more unpredictable and less cookie-cutter. Today, travelers have little appetite for risk when it comes to where they sleep and dine, and how they spend their time and limited resources. But not long ago, the nation was different, and the unexpected was as much a part of a road trip as the journey itself.

I want to tell you a little bit about my first time down Route 66 — 13 trips ago!

That year we were Mother Road virgins. America was wide open to us, and our curiosity was unquenchable. Waiting to hit the open road was agonizing, but then one day it was time to load the luggage and point the vehicle west. We were off.

The first major stop that we actually sought out was the human-like Gemini Giant in tranquil Wilmington, Illinois. If you read my book, Miles to Go, the story details our experience and the impact that standing in front of Gemini and the then-defunct The Launching Pad had on us. It would set the stage and the standard for the entire trip that year. He seemed to be mournful, reminiscent of a much busier, brighter past. But there was a glint in his eyes that also encouraged us and led us to believe that modern day Route 66 may just have some sparkle yet.

Then as we motored on, we came face-to-face with old, refurbished gas stations in towns like Odell and Dwight, and experienced what seasoned road travelers know as “greasy spoons.” It was all a bit overwhelming. But that was the joy of being on the move. The thing that we were not expecting was the people. Every place that we went, welcoming individuals emerged to greet and ask us our story. We were equally excited to hear theirs, and boy did they all have a tale to tell. Now, most of these folks were a little older, so they had lived some life and seen history when it was happening. We sat for hours with each of them, ingesting their stories of the road.

Then we hit Missouri and rose and fell on the Roller Coaster Highway. Turning a forested bend one quiet day — the skies were gray and gloomy and there was electricity in the air — we smacked into Uranus Fudge Factory with its giant rocket, dinosaurs, and everything else that makes it such a fun, perfect example of roadside America. We loved the spirit of the place, but on that first trip, it was rainy, and the thick, damp forest made the mood a bit bleak. Also, there were not many people around, so the huge parking lot was quite empty. The destination felt surreal. Since that first trip all we have ever encountered at Uranus is infectious energy and crowds of very enthusiastic visitors. I am glad that we had it all to ourselves that initial visit. What stands out to me most is how surprised we were to bump into places like Uranus and the Jesse James Museum, and the Dairy King in Commerce, Oklahoma. America is covered in a vibrant history, but it is also blanketed in a living quilt of weird and wonderful roadside stops that fill in where needed. There has been a concerted effort in recent years to preserve this living history but, sadly, a lot is still being lost.

This summer as you are out on the road, slow down, take it all in, and remember how important roadside stops are on the American landscape.

Stay safe and travel well.

Best,

Brennen Matthews Editor

PUBLISHER

Thin Tread Media

EDITOR

Brennen Matthews

DEPUTY EDITOR

Kate Wambui

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Nick Gerlich

LEAD EDITORIAL

PHOTOGRAPHER

David J. Schwartz

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Tom Heffron

DIGITAL

Matheus Alves

ILLUSTRATOR

Jennifer Mallon

EDITORIAL INTERN

Chloe Cassidy

CONTRIBUTORS AND PHOTOGRAPHERS

Aaron Garza

Billy Brewer

Carol M. Highsmith

Cheryl Eichar Jett

Deanne Fitzmaurice

Efren Lopez/Route66Images

JD Mahoney

John Margolies

Joseph L. Roberts

Katy Pair

Michelle Chaplow

Mitchell Corn Palace

Paul Aphisit

Sarah L. Boyd

Editorial submissions should be sent to brennen@routemagazine.us.

To subscribe or purchase available back issues visit us at www.routemagazine.us.

Advertising inquiries should be sent to advertising@routemagazine.us.

ROUTE is published six times per year by Thin Tread Media. No part of this publication may be copied or reprinted without the written consent of the Publisher. The views expressed by the contributors are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, or service contractors. Every effort has been made to maintain the accuracy of the information presented in this publication. No responsibility is assumed for errors, changes or omissions. The Publisher does not take any responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts or photography.

Spotted above the treetops of the railroad stop village of Dwight, Illinois, proudly towers a lone monument. Naturally, once upon a time, this structure — a picturesque windmill — harnessed wind energy to pump water upward from the earth’s dark depths. But there is even more to this story than meets the eye. Overlooking a tranquil, lily pad-speckled pond at an impressive seven stories, with a roadmap of paved pathways and lush forestry spread beneath, the steel-framed Oughton Estate Windmill resonates as a treasured landmark within the hearts of the Illinois Route 66 community.

Residing on 313 acres formerly belonging to John R. Oughton, local Irish chemist and business partner with Leslie Keeley of the renowned Keeley Institute — the first medical facility to treat alcoholism as a curable disease — the windmill was originally part of the Victorian estate’s renovation project started in 1895 by skilled Joliet, Illinois, architect Julian Barnes.

Unlike the usual, more simple designs, this windmill bore style: bright yellow threshold surrounded by a rugged patio, tapering dark slate tile roof supported by white pillars, rectangular windows that added to its lighthouse-like appearance, and a 360-degree observation deck enclosed at about the fifth floor — accessible by a spiraling staircase. Constructed by the U.S. Wind Engine & Pump Company, upon its completion in 1896, the cost totaled $3,424 — about $127,808.14 in today’s currency.

A crucial piece, the windmill — also known as the “pumping tower” — supplied fresh water for the beautiful estate grounds, greenhouse, gardens, and livestock. “[But] as far as drinking it or bathing in it, I doubt that happened,” explained Bill Flott, board member of the Dwight Historical Society. It would take two years after the windmill’s creation for the Keeley Institute to establish a running water system with the village’s first water tower.

much to the villagers’ dismay, the windmill was in bad shape. “Not the whole windmill; just the outside,” continued Flott. “They had the blades up high, and three of them were knocked off. I think that’s probably when some of the slate outside of it was destroyed. The windmill itself was very sound… It’s a steel structure, eight-sided… [the exterior is] wood… [with] slate on the outside of the wood.”

The then-owner, Robert “Bob” Ohlendorf, who had transformed the estate into a restaurant and bakery in 1978, was as keen on preserving the historic windmill as the community.

“We take a lot of pride in our community, and no one wanted to see that structure destroyed. It was adjacent to his property, so it’s a great spot to photograph for wedding pictures. There’s probably nobody in town that hasn’t had their picture taken at the windmill,” remarked Mary Flott, president of the Dwight Historical Society. Though it took three years, a new windmill head was purchased to replace the destroyed blades — shipped straight from Argentina, South America. “He was very community minded. I’m sure that he just wanted to see it up-kept.”

A well-beloved landmark for a steadily growing township, the 110-foot windmill — with its 88-gallon cypress tank and 840-feet deep well, connected to a pipe traveling underground — attracted travelers’ attention for miles around.

Over the years, the property exchanged hands many times, but then, one fateful day in 1975, a storm crashed through the peaceful little village. When the dark clouds cleared,

With the missing slate replaced by shingles, the contraption’s head was attached. Measuring 16 feet across, the windmill head was the largest of its kind built during that period.

By 1996, the windmill was introduced to its new owners, Mike and Bev Hogan. But, as the windmill once again fell into ruin, the Hogans made a monumental decision. On December 31, 2001, they donated the iconic structure to the village’s care — including the pond and, later, park-like walkways winding the red brick carriage house, transformed into a library, and restaurant.

The following year, the community-driven Windmill Preservation Project was created, and restoration began. “There’s a porch that goes around the outside at ground level, and that floor was in disrepair, so it was completely replaced. It looks like the exact same design as the original floor,” concluded Bill Flott.

Displayed on the National Register of Historic Places — alongside the restaurant — in 1980, the Oughton Estate Windmill is testament to a village’s dedication to preserving history. A town symbol, the windmill stands steadfast for first-time travelers and those who have visited many times, to admire for years to come.

By Sarah L. Boyd

Used as a mid-century marketing campaign, massive human-like statues started to sprout up across American soil in the 1960s, serving as the first friendly face to greet travelers at businesses along the country’s two-lane highways. But then, they disappeared. For years, they remained tucked away in forgotten niches, fallen from their former glory. But through the dedication of historian and restorationist Joel Baker — and unending support from the charming Route 66 town of Atlanta, Illinois — Muffler Men have finally found a place to present their proud history to the world: the American Giants Museum.

Before the ‘60s, fiberglass structures were not all that common. It was not until entrepreneurial cowboy Bob Prewitt emerged that advertising giants picked up steam. Originally focused on designing horse trailers, with the assistance of sculptor Gladys Brown Edwards, Prewitt created a fiberglass horse mold around the early 1960s to advertise his products. He needed something to get consumer attention. But when people started flocking toward the statue rather than the trailer, he wisely switched to the lucrative business of producing fiberglass animals.

However, one day Prewitt would get a request that changed everything.

Harnessing the durable material of fiberglass, the first of these giants — an axe-wielding, 21-foot-tall, bearded Paul Bunyan lumberjack mold sculpted by Bill Swan — hit the road in 1962 to advertise the Paul Bunyan Cafe located in Flagstaff, Arizona. It was a hit! A year later in 1963, Prewitt sold his business to the International Fiberglass Company, which purchased the molds from Prewitt, carrying on the trend of fiberglass giants with glowing results.

From 1965 to early 1967, giants were shipped across the states in droves, wheeled out for businesses eager to attract visitors to their service stations and quaint roadside restaurants.

Texaco Inc. especially pushed their hardest, requesting 300 fiberglass 25-foot-tall “Big Friend” statues. Black-andwhite video commercials featuring an actor interacting with a car model — advocating for generous, quality car service — emerged, emphasizing the Big Friend service aspect of the brand. Donning a black service jacket, brimmed cap, and jovial grin to tend to travelers’ beloved automobiles, they were the first of what would be later dubbed Muffler Men.

However, by 1974, things took a turn as International Fiberglass stopped production — demolishing the remaining statues.

“They were a big nuisance; it was tough to get them moved around. Wind, weather, and vandalism were taking their toll,” explained Baker, founder and owner of American Giants. “You had these giants blowing over and causing damage… And at the time, there were actually some complaints that these things were eyesores.” As the 1980s dawned upon America, the age of the giants reached a standstill, and their popularity faded away like the crusty flecks of paint adorning their fiberglass shells. But with Baker working alongside Bill Thomas, treasurer for the Atlanta Betterment Fund Organization, the giants would make the ultimate comeback.

In the sweltering summer heat of 2012, Baker and a group of friends drove down to the historic downtown district of Atlanta, Illinois, to film a vintage 19-foot-tall Hot Dog Bunyon

Muffler Man — moved from a retired hot dog stand in Cicero, Illinois, to the Route 66 town in 2003 — for their American Giants channel. Wielding a GoPro camera mounted atop a large pole, for Baker, the statue was one among many insightful videos to come.

But something more was in store for this Muffler Man hobbyist.

Unbeknownst to him and his crew, sheltered within his office space, Thomas peered out his window curiously. Hoping to offer valuable history about the giant, assuming Baker to be a tourist, he stepped outside — a decision that would lead to a more fruitful venture than either would have guessed.

“I went across the street and introduced myself — and that was the beginning of the wonderful relationship that we now have with Joel Baker and American Giants,” said Thomas, friendship forged, fittingly, at the feet of a Muffler Man. “He shared with me his passion for those giant statues… And, in the course of just talking, over the years, he would bring up every once in a while, ‘Oh, you know, I have all this stuff from International Fiberglass: documents, photos, artifacts. I actually own giants and various body parts of giants. What I don’t have is a museum.’ And I said, ‘Joel, one day. One day we’ll give you a museum.’”

Through a partnership with the city, in 2022, Thomas and the Atlanta Betterment Fund made good on their word.

Sitting down with Stan Cain, a retired architect from State Farm Insurance Company, Thomas — along with Baker — collaborated to create what would define the museum’s theme: reigniting the Texaco.

“We knew from the beginning that my Texaco Big Friend had to come to the museum and be one of the focal points. There are only six left [in existence], so having one there was a huge deal. And we kind of went with that,” continued Baker. “We have the stars, and we have the original Texaco banjo sign, and the Texaco giant, and the gas pumps and everything… it helps take you back to when all of these giants were being built.”

Designed by Ragland Buildings’ construction crew in October 2022 to resemble a 1965 Texaco gas station, boasting a white and green-striped, rectangular metal building with bright red gas pumps out front, a concrete parking lot, and a grassy area called the Route 66 Land of the Giants Rest Stop, the museum was ready to go.

Now, all it needed were exhibits. Over the following winter months, they got busy.

“Joel has been integral to [the project] … loaning his artifacts and documents and photographs from International Fiberglass along with giant statues and various body parts and other items that we have on display,” said Thomas. The moment visitors step inside the unique building, they are thrust into the immersive world of giants. “If you look up, you will see a 7-foot-tall Esso Tiger… crouching on a shelf above your head… We have three or four heads hanging from the ceiling.”

In the late summer of 2023, the museum — free to the public and staffed entirely by volunteers — was opened, promising visitors a fanciful experience with permanent and rotating artifacts, including one-on-one statue interaction. Accomplishing the museum’s goal of bringing people together to celebrate vintage Americana, the American Giants Museum is a one-of-a-kind opportunity for motorists exploring the colorful past of advertising on the Mother Road.

When you imagine the grand palaces and structures of the world, no one would fault you for thinking of the stony nobility of Buckingham Palace and the Taj Mahal, or the steely engineering icons of the Empire State Building and the Burj Khalifa. There does, however, stand a truly fascinating piece of curious engineering in a place not many would suspect. The plains of South Dakota have a grand, palatial structure of their own. Once one of many, but now the sole survivor, the aptly named World’s Only Corn Palace is an icon that stands both as a signal for the continuing agricultural prominence of South Dakota, and as a reminder of a strange period in the Mount Rushmore State, and the Midwest at large, where agricultural architecture was all the rage. The story of the World’s Only Corn Palace begins though not in South Dakota, but in Sioux City, Iowa. Little Chicago.

The year was 1887. The Big Die-Up, one of America’s harshest winters, had come and gone, but its effects were still very much felt across the United States as withered fields and frozen cattle had left many lacking. Sioux City, however, had been graced with sublime fortune as the worst of the droughts that afflicted many others in the Midwest had spared them, amazingly leaving them with an abundance. Amidst the dreary aftershocks of the winter that would mark the end of the free-range cattle days, Sioux City wanted — no needed — to show the U.S. that the Midwest could not and would not be kept down. Inspired by the beginning of Minnesota’s own ice palace tradition in St. Paul just a few years prior, the thought occurred to the people of Sioux City, why not build a palace out of corn? Seems like an obvious idea, right? And so, the construction began.

Sioux City’s first Corn Palace covered a commanding 18,000 square feet when it was completed for their Sioux City Corn Palace Jubilee. As was the case with many of the corn palaces to come after it, this ‘World’s First Corn Palace’ was a wooden structure upon which they covered every last inch of wood with ears of corn. Colored, sliced, and nailed as needed in order to create a beautifully eccentric piece of architecture with numerous, intricate, and exotic details that worked together to elevate the strange beauty of the Sioux City corn palace. The arched doorways were framed with farming scenes. A wax statue of the Roman goddess of grain, Ceres, was given a corn stalk scepter and cornhusk robes. A map of the U.S. was fashioned from grains and seeds. A spiderweb, complete with carrot spider, was made from corn silk. Not to mention countless murals of fields and rivers, buffalo and canoes, and symbols to honor the Native Americans. Safe to say, there was no part of their corn harvest that they didn’t make use of in some way.

And the corn craze didn’t stop beyond the walls of their corn palace either. An a-maize-ing fad swept through Sioux

City as their corn palace jubilee’s opening quickly approached. Society parties had corn themes, people wore beaded necklaces made of corn, hats made from cornhusks, and smoked from pipes carved out of corn cobs. October 3rd, 1887, saw the inaugural Corn Palace Jubilee open and the week that followed was a veritable cornucopia of joyous expression and great successes. 130,000 visitors, incredible attention from news sources the country over, and even a visit from the standing president, Grover Cleveland — although he didn’t arrive until the day right after the festival’s close — all led to Sioux City declaring their inaugural Corn Palace Jubilee an absolute and smashing success, and grounds to keep it up. And with each year, the Corn Palaces grew grander and more exotic. Right up until 1891.

That year, a cold and rainy autumn made the jubilee — argued by some to be the greatest of their corn palaces: this one stretched all the way across Sioux City’s Pierce Street, had a balcony atop a 200-foot-tall main tower, and even had an archway large enough for traffic to pass down the street through the palace — a rougher festival compared to their past four years. It just didn’t quite make up for the money that went into it, even leaving the city with a strange dilemma. They had the money to put it up and run the festival as usual, but they didn’t have the money to bring it back down. One of the greatest tools in the Sioux City corn palaces’ arsenal, their abundance of grains and corn, was also a problem. Birds and rodents were just as attracted to the palaces as people were, not to mention the ravages of time, eventually claiming the corn as they were exposed to the elements, so just leaving them up was not an option. Eventually the 1891 Sioux City Corn Palace was sold at auction, leaving one H.H. Buckwalter the proud owner of a palace of his very own for the low price of $1,211 (roughly $42,144 by today’s standards). While not very useful as an actual palace in which to house his family, Buckwalter at least got some good sheep feed and the ability to say he bought his own palace.

While 1891 was a rough year, the city was still motivated to keep their tradition going. And why shouldn’t they? People were coming from all over to see them, the city always fell into a joyous frenzy to help build the palaces, and there was always plenty of corn to use. Surely 1892 would be better and they’d get right back on track.

Sadly, the flooding of the Floyd River in May of 1892 led to the loss of over a dozen lives and heavy damage to property in Sioux City. As much as the city enjoyed their Corn Palace jubilees, they could not leave their citizens out in the cold amid such a tragedy. The hope was that this would be merely a postponement and not the end of a treasured city fixture,

but another financial crisis the following year in 1893 spelled the end of Sioux City’s corn palace fixation. Sioux City’s corn palace tradition may have only lasted five years, but it kicked off a passion across the Midwest and there was hardly even an interruption in the grander scheme of Corn Palace passion in the region. Just like the first kernel in a bag of popcorn, once one popped, many more began to follow.

With Sioux City’s inaugural Corn Palace in 1887 being such an overwhelming success, many towns and cities across the tri-state area of Iowa, South Dakota, and Nebraska started to get the idea themselves of building out their own prairie palaces. Bluegrass, alfalfa, corn, and much more went into making several dozen palace-like structures across the Midwest, and among the townships getting in on the agricultural architecture craze was none other than the town of Mitchell, South Dakota, a young township looking to grow in the then Dakota Territory.

“They used to call them grain palaces back in the 1800s,” said Corn Palace Director Doug Greenway. “They were trying to get people to move here, and the land office would say,

‘Hey, you could claim a quarter section as home stake. Stake your claim,’ and that’s what they did. They staked their claim to a piece of land in a township in a county in South Dakota [that] they got if they lived there for five years. It was slow going though, because it’s tough living out here, and they were trying to get people to move here. So, communities were building these grain palaces. Sioux City had a really nice one. Plankinton, South Dakota, just west of us, had several, so the leaders of Mitchell said, ‘We can’t let little Plankinton have a grain palace and not us,’ so they built what they called the Corn Palace at the time.”

People flock to great sights and sites, and fortune shone upon Mitchell, South Dakota, as misfortune hit Sioux City, not unlike how years before Sioux City flourished as others were struck by low crop yields. Mitchell’s Corn Palace opened its doors for the first time in 1892, right on the town’s Main Street, for all to witness the beginning of a new age in crop art.

Costing $3,700 ($124,720 by today’s standards) of community-raised funding, Mitchell’s first Corn Palace was a Medieval-style wonder that featured over half a dozen towers, ranging up to over 30 feet in the air. An exterior decorated with colorful and striped corn patterns, the original Mitchell

Corn Palace, referred to by many at the time as the Corn Belt Exposition, stood for over half a decade on the corner of 4th and Main Street. The unusual attraction maintained the same structure, but with new patterns and murals put up each year, as the city hoped to learn from Sioux City’s corn palaces and make the most of the structure they had as opposed to tearing it down and building a new one every year.

The corn palace that opened in the heart of Mitchell in 1892 though is not the Corn Palace that currently stands in the Palace City today. Their first corn palace remained until 1905 when the city made a bid to become the new capital of South Dakota, building a brand-new corn palace in the hopes of swaying the odds in their favor. While the bid was ultimately unsuccessful, their new palace was even more extravagant and massive, jumping from a 66’ x 100’ structure to an imposing 125’ x 142’; practically twice the size of the last and four times as expensive at a price — in 1905 — of $15,000. Just a single block away from their original corn palace on the corner of 5th and Main Street now, the new palace afforded even more space to display their corn murals and house even larger audiences, although, like the first, this new corn palace only really saw use during the summer months as those cold South Dakotan winters weren’t so great to weather in the unheated building. However, the popularity of the Mitchell corn palace only surged with this new structure, especially in light of its origin as the possible new home to the state’s capitol. And yet, it wasn’t enough. In 1920, the Corn Palace needed to be rebuilt a third and final time before it would be ready to become a truly iconic part of South Dakota that would remain standing and in operation for the next century.

“This building alone is 103 years old; this is the third corn palace we’re in now,” continued Greenway. “The only one left of the original grain palaces is the Corn Palace, so now it’s the World’s Only Corn Palace, and we’ve been the only one since 1907.”

Standing now as the World’s Only Corn Palace, the biggest change from the original designs that many corn palaces used was the switch to a fire-resistant brick and cement structure, removing some of the worry of a stray spark sending Mitchell’s palace up in flames. “These original grain palaces, they were basically decorations; they were a building framed loosely with lumber and covered with all kinds of grains and natural-

made materials,” said Greenway. The switch was a fortuitous bit of foresight as many years later in the 1970s, a series of fires plagued the Corn Palace, inflicting a not insignificant amount of damage, but thanks to the building’s new designs and fire systems, nothing irreparable afflicted the World’s Only Corn Palace.

Being such a large building covered in corn, it should be no surprise that it’s more than just people attracted to the Corn Palace. “There are all kinds of corny jokes that people make about being the world’s largest bird feeder and ‘How do you keep birds from eating all the corn?’ And the truth is, we don’t,” continued Greenway. “The birds sit around, and they have a picnic all summer long on our murals, which is why we replace them, but by replacing the murals, it keeps people coming back. They get to have new experiences with the Corn Palace.”

Across the years of its mass popularity near the end of the 1800s and into the early 1900s, nearly three dozen grain palaces made and decorated with corn, alfalfa, wheat, and so many more crops graced the wide expanse of America’s Midwest. As the craze died down and these halls of agricultural nobility came down one by one, one stood tall amidst the plains of South Dakota. Right in the heart of Mitchell, South Dakota, the World’s Only Corn Palace still carries on the torch that was first lit in Sioux City, keeping up a tradition that began over a century ago. Today, the Corn Palace is not only an eye-catching architectural art piece, but also host to all manner of events as Mitchell’s premiere convention center. Plays, three ring circuses, concerts, and, most importantly to this South Dakota community, basketball.

“We’re a civic center, the largest event center for our town, so any major events are held here, and in the winter, we play a lot of basketball here. Keep in mind, you’re not doing anything outdoors [during winter] unless you’re a farmer or rancher and have to go take care of your animals. People are looking for something to do. It’s dark at 7AM and it’s dark at 5PM, so we’re looking for something to do indoors in the evenings and that’s basketball. Our community likes basketball.”

Much has changed about the World’s Only Corn Palace across the decades. Once more medieval in design and fabricated with hearty timber, it now stands as sturdy stone in the Moorish Revival style, complete with onion-shaped domes and minarets. Geometric and general pattern murals have been replaced with complex and thematic designs, such as their soon to be completed 2024 theme of Famous South Dakotans. And yet, the heart of the idea still beats strongly as the Corn Palace draws attention from all corners, reminding travelers from across the Midwest and beyond that the plains of South Dakota are much more than just corn and wind and harsh winters. No, South Dakota is home to its very own vibrant, curious piece of culture and history.

Isn’t roadside Americana great!

By Cheryl Eichar Jett

Agleaming 190-foot-tall cross stands sentinel over Groom, Texas, a dusty small town — population 552 — about 40 miles east of Amarillo. Just to the north across the interstate, the blades of a wind farm lazily turn, and on the south side of town stand a row of grain silos, but one’s eyes are naturally drawn to the shining steel cross. From 20 miles away, travelers can see it as they approach Groom, some regarding it as their port of call and some astonished by what is looming in the distance.

The Groom Cross was constructed in 1995 by Steve Thomas, a man offering an alternative view to the adultbusiness billboards spread along the east-west stretch of I-40 through the western plains’ Golden Spread. Today, whether viewed as a Christian symbol or as a roadside attraction, like the Britten Leaning Water Tower just three miles down the road, the Giant Cross has grown into a 10-acre religious campus, a spiritual destination on its own.

Along America’s highways, everything large and unique turns into a tourist attraction — think muffler men, the Gateway Arch, the World’s Largest Catsup Bottle, the Space Needle. These giants are each a place to photograph and post on social media before being relegated to the back burner of one’s mind after the return to everyday life from a vacation. But some travelers, possessed with a historical bent or observant of their Christian values, take a more mindful approach to a roadside stop such as this. The Giant Cross, at a minimum, is a place to be respectful of Steve Thomas’ inspired vision. But the journey of his life to the point of envisioning and constructing such an enormous project began with twists and turns that would have deterred many an individual. But somehow his life story seemed to lead him exactly here.

Structural engineer Steve Thomas knew since he was a child what his career would be. “I was playing with my Tonka trucks in a dirt lot. We [kids] were making roads with our hands, and all of a sudden four or five guys looked over and asked why I’d dug a hole for a post. ‘That’s a signpost,’ I said. They asked, ‘What’s the sign say?’ And I said, ‘I don’t know.’ I never did know, but God had a plan for me back then.” But that was not the only experience that shaped Thomas. Growing up, his family struggled with extreme poverty, and his parents were both alcoholics. His father had violent tendencies. When Thomas was 17 years old, his father went on a rampage, attacking Thomas’ mother and sisters. They would recover, but afterward, his father, unable to come to grips with what he had done, committed suicide. A decade later, Thomas’ mother would do the same, forcing him to step up to complete the task of rearing his younger siblings before moving on to build his own life.

We are all influenced by our past and after a childhood of fear and uncertainties, Thomas was committed to building for himself a very different kind of life. He worked hard and earned an engineering degree from Texas Tech, after which he racked up a series of professional successes, including hitting oil with the first well he ever drilled, designing the world’s largest drilling rig, and establishing his own successful company. Armed with determination for a life well-lived and empathy learned from personal experiences that most of us have never had to endure, Thomas was able to move on from his troubled childhood and start a family with his wife Bobby (they have now been married over 50 years). Sons Bart and Zach were athletic from a young age, and Zach went on to become an All-Pro linebacker for the Miami Dolphins, while daughter Katina served as Miss Amarillo before winning the swimsuit competition in the 1997 Miss Texas pageant.

In 1995, Thomas was comfortable. He had retired, selling the oil and gas business that he had operated for some 35 years. He and Bobby were settled on their ranch, where they would regularly sit out on the front porch and watch the Panhandle winds blow the dust. He had time to think, and he thought about how blessed he was and how he had wanted to become a missionary. But he did not want to leave his home and his ranch, and travel around the world. So, what was the right path for him? Inspired by God’s leading, he decided that he would bring the world to Texas instead. And so, he did.

Thomas decided that it was time to create a spiritual billboard as a counteraction against those adult billboards along I-40. But then “in a V-8 moment” he realized something: “It’s like one of those commercials where you slap your head.” It hit him that it was well within his capabilities to build a giant cross instead of just a billboard after his wife Bobby’s discovery of a 100-foot-tall sheet-metal cross — 300 miles south of them — ignited the idea within both of them.

“It was in our local newspaper, but the cross was in Ballinger, Texas. I was like, oh my gosh, we should check that out,” Bobby said. “I showed him the story and we just kind of realized that was the Lord’s plan for him. Since he was a civil engineer and he had designed one of the world’s largest drilling rigs, it was perfect practice.”

But the search for a place to erect the cross was not so easy. After crossing Pampa and Amarillo off their list of possible locations due to a variety of local restrictions there, a chance drive past Groom one day called the Thomases’ attention to property there that might be available.

“I’d been trying to build it in various cities and my wife said, ‘Why don’t we just build it right along the interstate in Groom?’ and I had another V-8 moment. I mean, why not?” explained Thomas. “I knew one person — Chris Britten — in the area, and we pulled into his office on a Saturday

afternoon. I told him, ‘You won’t believe what I want to do. I want to build the world’s largest cross along Interstate 40 and I’m looking for land.’ And he said, ‘I’ll just give you 10 acres.’ So that’s how we ended up in Groom, Texas.” (Chris Britten is the son of the late Ralph Britten of the Britten Leaning Water Tower family.) And so, Thomas was ready to design and build the biggest project of his life. He was well equipped with everything that he needed to accomplish such an enormous feat: he was a structural engineer, he was a millionaire, he was a man of deep-seated faith, and he believed that he was chosen by God — perhaps readied because of his childhood traumas — to build this cross.

Engineer Thomas oversaw eight months of construction in two separate shops in Pampa, Texas, keeping over 100 welders busy on the project. He had borrowed the design of drilling rig masts, with which he was well familiar. White corrugated steel, the kind used for industrial warehouses, was transformed into a 2 ½ million-pound steel cross. Initially constructed in three separate — but huge — pieces for transport to its new home at Groom, the cross was finally completely assembled, where it stood as tall as a 19-story building. On the day that the huge foundation was poured, sales of ready-mix concrete to other customers screeched to a halt in the Texas Panhandle.

In all, the cross costed Thomas half a million dollars, but he would have spent even more and built it even taller if objects higher than 200 feet had not been subject to FAA regulation. The original goal was to have the cross constructed and

standing tall by Easter of 1995, but they simply could not get it done by then. But in July 1995, Steve and Bobby Thomas watched as the two-and-a-half million-pound cross was finally erected on the 10-acre plot, just off Exit 112 in Groom.

Soon travelers began to stop.

But the Thomases were not done. Initially standing alone, the cross became the centerpiece of the Cross Ministries complex, but after the installation of the giant cross, a small building was constructed for greeting visitors. One day, while working at his drafting table, Thomas was trying to work out a design for a path from the cross to the parking lot and the right spot to arrange the stations of the cross — one of the most important additions to his huge undertaking — but his plan did not satisfy him, and he threw it in the trash. He needed some guidance. Picking up the phone he called a friend — Demetrio “D” Martinez, one of the welders of the cross, and a man he considered to be his spiritual partner.

“We got together and prayed for God’s vision about laying the stations out and D’s eyes got real big. He said, ‘You got this, don’t worry. It’s good to look at Scripture — come on, Steve, that’s all you need,’” Thomas explained. “I blindly put my finger down as I read Ezekiel Chapter 1. It basically says, ‘I see a wheel within a wheel with many spokes,’ and that’s how we built it. And then we went back and read the Scripture again and it says, ‘I see many eyes along the outer

wheel.’ Sounds real strange, but if you see this plaza from a narrow view, the stations are sitting on oval smooth concrete forms, and they look like eyes, because the sculptures are bronze, and each one shines just like a pupil over there in that oval form.”

Thomas did not stop with the stations of the cross. Over the next eight years or so, an exact replica of the Shroud of Turin, a life-sized Empty Tomb, the Memorial for Innocent Unborn, a bronze sculpture of St. Michael the Archangel, and The Ten Commandments Monument were added.

The complex now also includes a 20,000-square-foot building which houses a state-of-the-art 225-seat theater, gift shop, restrooms, offices and counseling center, the Divine Mercy Fountain, and the Divine Mercy Reception Gallery, featuring paintings of the Apostles by Texas artist Kenneth Wyatt. Sometimes on a weekend, a barbecue station is set up outside, indicating that a private event such as a wedding or funeral is taking place. And, unlike many attractions, travelers are welcome to stop for the night to sleep in the parking lot, adequately sized to handle big rigs and RVs.

“This is a 24/7 preaching effort,” Thomas said. “It’s open at night. You can sleep here. There’s enough lighting so you can read the plaques all over the site and see the facilities. So, it’s still a lot of visualization whether we’re here or not.”

Illuminated at night in the dark Texas sky as a sort of modern-day Star of the East, the cross is seen each year by an estimated 10 million people, who, as the Thomases’ Cross Ministries likes to say, “makes people think about Jesus Christ, if only for a minute.” The grounds and parking lot are open 24/7 to visitors and travelers, and many of the 10 million people who drive by on I-40 each year stop.

“Although it has its own following because of its religious meaning — it’s a roadside attraction as well —but it’s so different from most other attractions,” said Dora Meroney,

secretary-treasurer of the Old Route 66 Association of Texas and owner of Texas Ivy Antiques on the 6th Avenue alignment in Amarillo. “They’ve made it very nice, and they’ve turned it into a destination.”

Although the Cross of Our Lord Jesus Christ Ministries states that it is not affiliated with any church, and therefore has no set congregation, its goal is to continue to minister to the millions of souls from all around the world that drive by it every year. That goal impels them to continue to grow and expand. Currently, they are completing the Last Supper sculptures and need to commission three more Apostles to finish the exhibit. Ground has been broken for a separate chapel after a thorough design process. When the chapel is completed, those seated within it will look past the altar to see a view of the cross through a wall of glass.

“We’ve put it under plans right now and my take is in two or three years we could really start on it,” Thomas enthused. “It will be a beautiful facility because when you’re in that chapel in your pew, you will see that big cross, you will be able to see Calvary and the circular stations. We think it will be an amazing spiritual experience. You know, we’re used to going into a church and seeing what’s kind of before us, behind the altar, and this will be an extraordinary sight.”

Also on their to-do list of future plans is a Bible History Museum and gardens with biblical scenes cast in bronze. Thomas has stated that, although he is in his 70s, he will keep adding new features for as long as he can.

“On its own it has a following, you know, on its own aside from 66,” said Meroney. “So, it’s helped bring a different group of people to 66, and when it was the largest cross in the northern hemisphere that was pretty cool. But then Illinois beat us out!”

Hailed at its construction in 1995 as the tallest cross in the U.S., it was bypassed a few years later when the City of Effingham, Illinois, assisted by Steve Thomas, built a cross just eight feet taller. (The Effingham cross is, in turn, dwarfed by the 208-foot-tall cross at Mission Nombre de Dios in St. Augustine, Florida.)

But for travelers across the Texas Panhandle, the Groom Cross is plenty tall enough to satisfy their needs, whether they are on a spiritual pilgrimage or a hunt for the “giant” constructions of the American road — such as the leaning water tower not far away.

“We get a great variety. There’s really no typical visitor,” said Bobby. “Some people just don’t want to leave, because it’s so peaceful here.”

A giant, but peaceful, roadside attraction, situated in a dusty little Panhandle railroad town that ended up on U.S. Highway 66. That could be a tourism trope, or it could be just the stop that you did not know you were waiting for along the world’s most famous highway.

On Museum Square in Downtown Bloomington, the Cruisin’ with Lincoln on 66 Visitors Center is located on the ground floor of the nationally accredited McLean County Museum of History.

On Museum Square in Downtown Bloomington, the Cruisin’ with Lincoln on 66 Visitors Center is located on the ground floor of the nationally accredited McLean County Museum of History.

The Visitors Center is a Route 66 gateway. Discover Route 66 history through an interpretive exhibit, and shop for unique local gift items, maps, and publications. A travel kiosk allows visitors to explore all the things to see and do in the area as well as plan their next stop on Route 66.

The Visitors Center is a Route 66 gateway. Discover Route 66 history through an interpretive exhibit, and shop for unique local gift items, maps, and publications. A travel kiosk allows visitors to explore all the things to see and do in the area as well as plan their next stop on Route 66.

CRUISIN’ WITH LINCOLN ON 66 VISITORS CENTER

Open Monday–Saturday 9 a.m.–5 p.m.

CRUISIN’ WITH LINCOLN ON 66 VISITORS CENTER

Open Monday–Saturday 9 a.m.–5 p.m.

Free Admission on Tuesdays until 8 p.m.

/ CruisinwithLincolnon66.org

*10% o gift purchases

200 N. Main Street, Bloomington, IL 61701 309.827.0428 / CruisinwithLincolnon66.org

*10% o gift purchases

Down in the desert grassland of southern Arizona’s Santa Cruz County, surrounded by landscape that feels unblemished and remote despite its proximity to Interstate 19, is the small town of Amado. Founded in 1878, by homesteaders forging a new life on the land and christened after Manuel Amado, a rancher who settled in the area around 1850, the town and surrounding region became a rancher’s haven, most famous of which was the Kinsley Ranch, established by Otho Kinsley in the 1920s. Kinsely, whose specialty was raising bucking horses, had acquired about 600 acres from Sahuarita down to Tubac, near the border, and established a gas station, a tavern-cum-grocery store, Kinsley Lake, and a large hexagonal dance hall building. Before his premature passing in 1962, Kinsley sold off most of his land and holdings. The dance hall burned down, and the old general store eventually became the landmark Cow Palace and Restaurant with its giant cow on top of the roof.

Then for the longest time, Amado remained just another small, obscure rural community nestled in the middle of open plains, just off Exit 48 on Interstate 19. However, that changed when Tucson sculpture artist, Michael Kautza, was recruited to create a giant sculpture that became a defining feature for the tiny community and put the town on the proverbial road trip map.

In the early 1970s, Kautza — famed for building the iconic giant Tiki head and other statues that once stood at the defunct Magic Carpet Golf in Tucson, as well as the giant cowboy boot on Sabino Canyon Road — started work on building an enormous steer sculpture that would be affixed to the entrance of what was then a bait shop, whose backyard was Kinsley Lake. Kautza recruited the help of two local teenagers, Hans Van Sant, and Danny West, to help with mixing the cement and mortar, while Kautza welded the framework for the skull, eventually adding stucco and rebar for reinforcement. Around 1975, the steer skull, affixed on faux rocks, was finished. It featured a giant nasal cavity that customers walked through, hollow eye sockets, and pale-yellow curved horns that measured 30-feet-tall. The monument made for a striking feature, easily visible, turning an unassuming building into an instant landmark.

As the years rolled by, the building housed several different businesses, including a clothing store, and a roofing company. But in 1993, Ed Madril and business partner, Al Reynolds, purchased the building and from 1998 to 2012, operated it as the Longhorn Grill, serving everything from burgers and steaks to Mexican and Italian cuisine. The giant skull was the perfect advertisement for the steakhouse. However, the restaurant, facing stiff competition from the Cow Palace across the street, fell on hard times, and they were forced to sell to businessman and metal artist John Gourley, who operated the premises as an event venue until his passing in 2015. Then, it lay vacant once again. But not for long.

“[My wife and I] dated there,” explained Greg Hansen, who now co-owns the Longhorn Grill & Saloon with his

wife Amy. “We did some wedding anniversaries and some other social events inside the Longhorn as a caterer. So, we got a little bit familiar with the inside.”

For the next couple of years, the Hansens, local restaurateurs who owned eateries in nearby Green Valley, drove past the lone building on their usual work-to-home route between Green Valley and Tubac. And then one day, when Gourley’s son, Al, placed a for-sale sign out front, the Hansens ceased the opportunity and purchased it right away. By May 2018 the iconic venue had a new lease on life.

However, a few months later, on September 24, Amado faced a devastating flood that led to the destruction of their competition across the street — the popular Cow Palace. Fortunately, the Longhorn Grill remained untouched and the skull intact. “When the microburst flood first hit, water flowed into the [empty] lake [behind the property] and did not do any damage to the Longhorn at all.”

In 2019, after extensive renovations, which included gutting the kitchen, expanding the dining room, and cleaning and repainting the iconic skull, the Hansens officially reopened as the Longhorn Grill & Saloon. Boasting a Western, casual atmosphere, the interior is heavily inspired by the skull: entering through the steer’s nose, you are greeted by the saloon’s long, bronze cow skull — crafted by John Gourley — centered amid shelves of variegated alcoholic beverages and, in the following chamber, the dining area adorned with faux rocks, gunnysack pillows featuring local rancher brands, and cattle-themed artwork.

For the two years, business boomed. Then the pandemic happened. But, after closing for a day, the Hansens returned with a plan. Using the restaurant’s three-and-a-half acres, they expanded to include outdoor seating. “We poured a lot of money, and a lot of effort, and a lot of sweat, into that building… and I wasn’t going to lose it because of [the pandemic],” concluded Hansen.

Despite the town’s size, and its seeming obscurity, the town and surrounding area served as a backdrop in several films, including in the opening scene of the 1955 film Oklahoma!, and the skull sculpture has made its own cameo most notably in Martin Scorsese’s 1974 film Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, and in the 1995 Drew Barrymore movie Boys on the Side. “People get their pictures taken here and we’ve had Western dress models come to do photo shoots in front of the steer head. We’ve had TV shows filmed here... we had a big line dance — around 40 or 50 people — doing a line dance for TV, right in front of the skull. It’s just striking. It’s unique, and people like to take advantage of it.”

Today, the giant longhorn skull sculpture remains one of the most unique restaurant entrances in the country and a proud roadside icon and symbol of the diversity of the Southwest. So, if you are ever driving anywhere on I-19 heading towards Nogales, Arizona’s southern border town, look out for a giant white steer skull and the small town of Amado. Discoveries like this unexpected roadside gem is exactly what makes the American road trip so darn special.

While Route 66 contains its share of unique landmarks that cause many a wide-eyed wanderer to pull off the highway, a stainedglass chapel nestled among the rolling green hills of Carthage, Missouri, may not be a destination that motorists are expecting. Surrounded by expansive hedged gardens, elegant statues of winged cupids, and teardrop-eyed children, the sanctuary is a welcome respite from the quiet road. Though beautiful, the true treasure lies at the heart of the property. Walking through glistening, lovingly crafted halls that embody childhood innocence in its purest form, one can feel themselves stepping into another world: the Precious Moments Chapel.

Despite assembling a multi-million-dollar empire around the adorable, hand-painted, child-like figurines dubbed Precious Moments, the man behind such compelling artistry, Samuel J. Butcher, grew up with next to nothing. Born in Jackson, Michigan, in 1939, Butcher was the third of five children and his family struggled financially. “They did not have much as far as finances were concerned, but they did the best that they could at the time,” explained Joette Blades, the director of the Precious Moments Chapel. “His father did some mechanic work to supplement their income. Butcher didn’t have much as far as materials were concerned.” However, though he had a humble upbringing, his passion for art flourished. As a young child, he often would scavenge through rejected piles at factory dumps for drawing materials.

that we share with our loved ones; the memories that we always cherish.”

Recognizing how his art resonated with people on a deeper level, Butcher felt inspired toward creating a destination that offered free access to all willing to seek, a place that would be his most fulfilling project ever: a chapel.

But not just any chapel — a chapel wholly devoted to his art, while reflecting his original purpose toward openly sharing his faith and uplifting others. “Mr. Butcher built the chapel as a way of saying, ‘Thank you’ for all the blessings that God had given him in his life. He never dreamed that he would have the kind of success that he did through Precious Moments. And when he was so richly blessed, he wanted the opportunity to give back.”

In 1975, to support his own growing family, Butcher started a small business with his best friend Bill Biel called Jonathan and David, capturing his Precious Moments artwork through greeting cards. After a promising deal with Gene Freedman from the collectible-making company Enesco, in 1978, his art designs were transferred onto 21 porcelain sculptures. Fast forward to 1985, and his artwork — now a full-scale business — had become a pop culture sensation, enrapturing the hearts of his audience with the cutesy aesthetic wrapped within his Precious Moments’ teardrop-eyed children collectibles. But the figurines represented something more. They were a symbol. “Precious Moments are based on those times in our lives that we want to capture and hold onto those memories forever,” said Blades. “There are some moments

After witnessing the vibrant wall-to-ceiling paintings adorning the Sistine Chapel in Rome, Butcher’s creativity overflowed, crafting a roadmap that would lead him straight to Carthage. With its sloping hillside, babbling creeks, and cavernous caves, Butcher believed that God had brought him to the perfect place to lay the groundwork for his masterpiece. In the sweltering, sweat-soaked summer of 1985, the buzzing of construction echoing off the walls, Butcher scaled the 30-foot-tall scaffolding, lay on his back, and painted what would become the most challenging section: the ceiling. But it was all worth it. A year later, the ceiling — showcasing baby cupids flying across a night sky filled with puffy white clouds — was completed. Not long after, in 1989, the chapel’s ornate, teak wood doors opened to the public.

Until his passing on May 20, 2024, Butcher resided in a house on the chapel’s beautiful grounds. “He [was] working at home and painting at his leisure in the studio. Sometimes he [would] come and meet us at the chapel.”

Butcher could never have imagined the impact that his art would make generations later. “I think for a lot of people along their Route 66 journey, [the chapel] is a great thing because it brings them back to an earlier time in their life, too,” reflected Blades. From long-time enthusiasts to weary travelers passing through Carthage, the chapel stands as a proud testament to one man’s unwavering faith in crafting a monument to endure in the memories of others.

By Brennen Matthews

In the ever-evolving landscape of popular music, certain artists carve out a niche for themselves, leaving an indelible mark that transcends generations. One such luminary is Huey Lewis, whose soulful voice and timeless hits have solidified his place in the annals of music history.

Born Hugh Anthony Cregg III on July 5, 1950, in New York City, but raised from the age of five in Marin County, California, after his parents’ divorce, Huey Lewis’ early life was a tapestry of diverse experiences that would lead him to the vibrant music scene of the San Francisco Bay Area. Lewis excelled academically, even scoring a perfect 800 on the math portion of the SAT and attended Cornell University to study engineering. However, his love for music — particularly the harmonica — would eventually steer him away from academia and toward a life of rhythm and melodies.

Lewis’s musical journey took flight in the late 1970s when he co-founded the band Huey Lewis and American Express, later renamed Huey Lewis and the News. With Lewis as the frontman, the band truly burst on to the radar of music fans with their sophomore album, Picture This (1982), which featured the hit single “Do You Believe in Love.” This catchy tune served as a precursor to the band’s meteoric rise to fame and set the stage for a string of chart-topping songs that would dominate the airwaves throughout the decade.

In the summer of 1983, the music world was abuzz with anticipation as Huey Lewis and the News prepared to release their third studio album, aptly titled Sports For Lewis, the stakes were high — his band’s previous albums had achieved moderate success — but Sports was poised to be their real breakthrough into the mainstream. Sports quickly became a cultural phenomenon, with a series of anthems that would come to define the sound of the 1980s. From the exuberant optimism of “The Heart of Rock & Roll” to the irresistible charm of “Heart and Soul,” each track was a testament to the band’s powerhouse of musical talent.

The decade would prove to be a golden era for Huey Lewis and the News, as they churned out hit after hit, including classics like “The Power of Love,” “Hip to Be Square,” and “Stuck with You.” Their signature sound of feel-good music resonated with a broad worldwide audience, earning them legions of devoted fans and critical acclaim. However, amidst the peak of their success, Lewis faced a formidable challenge that threatened to derail his musical career.

In the mid-1980s, he was diagnosed with Ménière’s disease, a chronic inner ear disorder that causes vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss. Though his battle necessitated adjustments, Lewis continued to create music and perform live, inspiring audiences with his unwavering passion, proving that even in the face of adversity, the power of music prevails.

Today, Huey Lewis’s impact on the music industry continues, his timeless hits serving as a testament to his impressive legacy. As a pioneer of the pop-rock genre, he has left a lasting imprint on the hearts and minds of music lovers around the world, reminding us that true greatness lies not only in talent but in the ability to persevere despite hardship. Huey Lewis’s musical journey is a testimony to the transformative power of music and the enduring spirit of a true artist.

You grew up in Marin County, California, right at the epicenter of the 1960s counterculture movement. Were you very affected by everything taking place at the time?

They were heavy times, obviously, with the hippie movement just starting and [with] music.

The Summer of Love had an influx of people coming to California from the East coast. It was huge. There were signs out like, “New Yorker Go Home!” San Francisco and Marin were invaded by people from all over the country, and we rebelled against that. In those days, everybody was in a band, and there were so many live venues, and so many places to play. The exciting part was that the genres were being broken up, like the Grateful Dead. Those bands in 1967, they were the first bands that didn’t play 3-minute songs. They took a jazz player’s approach to pop music if you will, or a kind of country music, in the Dead sense. They were marvelous times for music.

Did you feel at that time that it was all happening in San Francisco, or was LA still the place where bands went to break?

No, it was definitely happening in San Francisco. I went to prep school in New Jersey, took a year off to bum around Europe, and then I was in my first year at Cornell University. San Francisco was blowing up. I was playing in charity bands, and I said, “I’ve got to get home,” so I quit school and went home to San Francisco and joined the action. Everybody knew that’s where it was happening, that’s why we were so surprised when we heard that the best rock’n’roll town in America was Cleveland. (Laughs) I thought, “You gotta be kidding me! How can Cleveland be the best? We have everything here in San Francisco: we got Santana, The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane...” We had so much. San Francisco was on fire.

After high school, you hitchhiked across the country from California to New York. What was behind that decision?

I went to prep school in New Jersey. My mom was one of the first hippies, and my dad was worried… he wanted to get me out of San Francisco. It was blowing up; it was like 1962 or 1963. My dad convinced me that I needed to go away to prep school because it was a wonderful opportunity for me: I could compete with the best. In his mind though, he wanted to get me out of my mother’s house and out of San Francisco, so I went. I skipped second grade, so I was a year younger, and when I graduated from Lawrenceville Prep School, I was 16, and then turned 17 the next month. I was accepted into the Cornell University College of Engineering, and my old man said to me, “Congratulations, you’ve done everything. As far as I’m concerned, you can make decisions on your own, you’re a man now, and you can do whatever you want.” But there was one more thing that he was going to make me do. He wanted me to take a year off and bum around Europe. I didn’t have any money, but in those days you could hitchhike. I hitchhiked everywhere. I was on my way to Europe but needed to fly from the East Coast. It was cheaper and easier.

Hitchhiking is sort of romanticized from back then; from the Dust Bowl era all the way through to the 1950s. Now,

of course, we see it as a little more dangerous. When you were hitchhiking, especially across America, were you ever afraid of any of the people who offered you lifts? Did anything dodgy happen?

Oh yeah, we had some close calls. I got picked up by an ex-convict, a guy who had just gotten out of jail and he didn’t have any money. We had to siphon gas all the way from southern California, where I started, to Denver, Colorado. I had money — I had a couple hundred bucks — but I didn’t want to tell him that, so I pretended not to have any money either. So, we would go somewhere, find a car, and siphon gas at night. I thought that was a little risky and he was a crazy guy, but it worked out.

I remember freezing my butt off in Ohio waiting for a ride, though. I hitchhiked to Boston, I had classmates at Harvard University, and I hung out in their dorm for four or five days. I saw Muddy Waters at Club 47 in Boston!

Did you sleep in motels as you traveled, or did you manage to drive the entire way?

No, I had a sleeping bag. I would sleep by the side of the road a lot of times, in the car, or wherever — just stowed away. When I was in Europe, it was the same thing; we slept anywhere. People would take us in sometimes. I remember in France, a family took us in, and the dad was a physical fitness nut, and he got the whole family up at like 5:30 in the morning to do calisthenics. (Laughs)

You learned to play the harmonica while waiting for rides when you hitchhiked across the States?

I carried a few harmonicas that Billie Roberts gave me, he was my mom’s boarder, and he was a folk singer; he wrote “Hey Joe” and he used to play harmonicas with one of those harnesses. He gave me a bunch of old harmonicas. I was playing them already in prep school, but when I took a year off, as I was hitchhiking by the side of the road I would play, so I got better.

Over in Spain… this is 1968, which was Franco [era] Spain. They had the three-corner cops, and they were super strict, so it was very hard to get a ride. Because I had long hair it was very difficult to get a ride, so I would play for hours on the side of the road. (Laughs) But I played harmonica in the squares of Europe for a year.

When you went back to America, that was when you started Cornell?

Yes, I spent a year abroad and then I went back to Cornell. I walked into the engineering quad, and I looked around at all the engineering students, and it didn’t look nearly as fun as hitchhiking through Europe and playing the harmonica. At that point, a little bell went off in my head and I thought, “I don’t know about this engineering thing.”

When did you decide that you wanted to be a singersongwriter?

It happened when I was bumming around Europe. I went to North Africa, to Morocco, and I had a travel companion, a guy called Michael Jeffries. He and I met in London,

and he was from South Africa. He had hitchhiked all the way from South Africa to London. He was the expert and he’d never been to Morocco, so we said, “Let’s do that.” We hitchhiked to Morocco — we were only going there for Casablanca — and we were gonna be there for, I don’t know, a week or something. But they had the marijuana pipes, and we got so stoned. We kept thinking we were going to leave the next day, but we could never leave. (Laughs) So, I spent like, two or three months in Morocco. Then, on the way out, we were hitchhiking, and we crossed the border of southern Spain, heading to Portugal. We got a ride with a really crazy guy, his name was Jimmy Van Der Haag, he was a Dutch guy. He was in his 80s and he had a little handlebar mustache. We were hitchhiking in Spain, where you can’t get a ride because it’s Franco Spain, and here comes this 1930 Chevrolet pulling an Airstream trailer. Apparently, the car had been used in the movie Casablanca in Morocco. It was his car. He was gonna drive it all the way back to Holland and he picked us up.

He liked to drink a bit, so he’d stop at bars along the way and have a shot of slivovitz and then we’d get going again. At some point in the evening, we were on this dirt road with water on both sides, and I guess he got a little hammered and drove the car into the water. I remember this specifically; he gets out and he gets a fire extinguisher—he had a fire extinguisher—and he scorched the motor with it. Then gets back in and the car started right up. (Laugh) We drove out of there, but my knapsack was back in the Airstream trailer, and it floated, because everything got wet, and somehow my

passport was lost. Now, we get to the border of Portugal, and I have no passport, so they refused for me to enter without a passport. My South African partner went on and the driver went on and I hitchhiked back to Seville, Spain, to go to the embassy to get a new passport. I had no money, so I get to the passport office of the embassy at 4PM. It was Friday and they were about to close. I knocked on a door and said that I needed a passport. They asked if I had 20 bucks, I said, no, and they said, “Come back when you got 20 bucks,” and shut the door. Now, I wandered into town in Seville, and I played my harmonica.

I’m playing, and these students come and see me. They’re interested: I have real long hair, I come from San Francisco, and the hippie thing had just blown up and it was catching on in Europe. They had found a real hippie, and they were full of questions about San Francisco and the hippie stuff. I explained to them that I needed a passport, and they said, “No problem, we’ll throw you a concert.” So, we auditioned for a guitar player; we found an Australian kid who played a little blues. We [practiced] for about three or four days… these students put up posters all over town advertising “Los Blues: Huey and Michael.” It was really well marketed. Now, it comes time for the gig at the art center and we were the headliners, me and Michael, and the opening act was a Spanish band called Los Nuevos Tiempos, and they were fantastic. They were, at least, a nine-piece, maybe 11-piece group. They had the same wardrobe, dressed to the max, and choreographed. They were amazing. I thought, “We are going to die here!” (Laughs) They had the whole stage and then they put a little pod out in front for us, a little round

stage in front of the major stage, so we’re kind of in the audience a little bit. There were two chairs, a microphone for his guitar, and a microphone for my harmonica. So, two mics and two chairs. We follow this amazing band and now we walk out, receive an introduction applause, and then pin-drop silence. So, we start; I can’t remember what we played, but we start playing, and the place is super quiet, and I’m thinking, “Man, we are dying here.” (Laughs) “This is not going to be pretty.” But for some reason… we played the whole song, we finished the song, and the place goes crazy. They just went crazy, and that’s when a bell went off right there, and I said, “Bingo, this is what I want to do.” But it was years later before I joined my first professional band.

In 1971 you joined Clover. Were they already together when you joined?

Yeah, they were a four-piece band. They’d had two records out that hadn’t really done anything, but they were the most successful band in Marin County at the time.

I met them all because we had a moonlighting gig. We had an eight, almost 10-piece bluegrass band. We would go to Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco and busk. We had a stand-up bass, a couple of fiddles, a banjo dobro, harmonica, [and] a couple of guitar players. We did all this bluegrass stuff and we made $120 and split it. We each got like $15 apiece. We’d go and have a couple of drinks, and that was our evening. Three of the members of that band were members of Clover too, so they asked me and Sean Hopper, our keyboard player, to join Clover.

In 1976, the group finally found a bit more commercial success.

Yeah, Clover’s earlier albums had been released on Liberty Records in London because they had a licensing deal with Fantasy Records. There was an A&R guy called Andrew Lauder who loved this country rock thing that was happening. Clover was one of the very first country rock bands. The Byrds, The Flying Burrito Brothers, Clover, and Commander Cody were the very first hippie-country bands. We joined that band and we got signed to Phonogram Records (UK) because Andrew Lauder loved all of that. He believed that this would be the next thing, that country rock would take over.

It was called pub rock because nobody ever played in pubs before. There was a band from Marin County called Eggs over Easy that set up and played in a pub, and it started to take off in London. These two managers, Jake Riviera, who managed Elvis Costello, and Dave Robinson who managed Graham Parker and Nick Lowe, formed a company called Stiff Records. They also managed Clover, so their plan was to sign Clover, bring us over to Britain, and take Britain by storm. But the day we landed in Britain, Johnny Rotten [vocalist for the punk rock band the Sex Pistols] spit in the face of the first New Musical Express (NME) reporter, and the game was on: punk hit and we were out. We were a longhaired, country music band.

In 1978, Clover disbanded, and you went out on your own.

We disbanded. We had made two records, neither of which did anything, but both produced by Robert John “Mutt” Lange. They were the only records produced [by Mutt] that

didn’t sell 18,000,000 records. (Laughs) But I had witnessed the punk movement firsthand because our management was in the Stiff Records office. The one thing I liked best about the punks was not the music necessarily, because I was into my own music, but I loved their stance. Clover had spent so much time grooming ourselves for the major labels and listening to their advice, which is always to be like the band that’s popular right now. The punks were just thumbing their noses at the music business and saying, “Hell no, we’re going to do our own thing, we don’t care.” I thought, “Wow, how liberating,” and I vowed that if this band ever broke up, that’s what I was going to do. I was going to go back to Marin County, find my favorite musicians, form a band, and sing all the songs myself.

Why did you choose the name Huey Lewis and American Express as your original name?

I think it was a great name; it was what we sounded like. We were very American; we had a kind of R&B foundation… it wasn’t heavy metal by any means; it was more of a Rhythm and Blues kind of rock’n’roll. I thought that’s what we sounded like, very American. We called ourselves Huey Lewis and American Express, and on the eve of the release of our first album, the label was afraid that we’d be sued by American Express, so we had 24 hours to come up with a new name, and we thought of “the news.” It was the only name we could come up with. It kind of rhymed a little, “Huey Lewis and the News,” it came off the tongue a little bit. It was all we could come up with, we were thinking of “the royals,” or “the fools,” but none of those were very good.

The first album didn’t perform great, and you realized that you needed to have a hit on the second album, or the label may end up dropping you.

You think about 1978: there was no Internet, no jam bands, and there’s no FM radios [or] contemporary hit radio (CHR) programs then, so the only avenue to success was a hit single. If you wanted to play your own music and make a living, you had to have a hit single. After our first album, we were no spring chickens. I was 29 years old and had been playing in bands for 15 years, cut two records with “Mutt” Lange already, and I knew something about the studio. We petitioned our manager and he agreed; we insisted on producing the next record ourselves. We knew we needed a hit; we knew that we had to make commercial choices, and we wanted to make those commercial choices ourselves so that we could live with them.