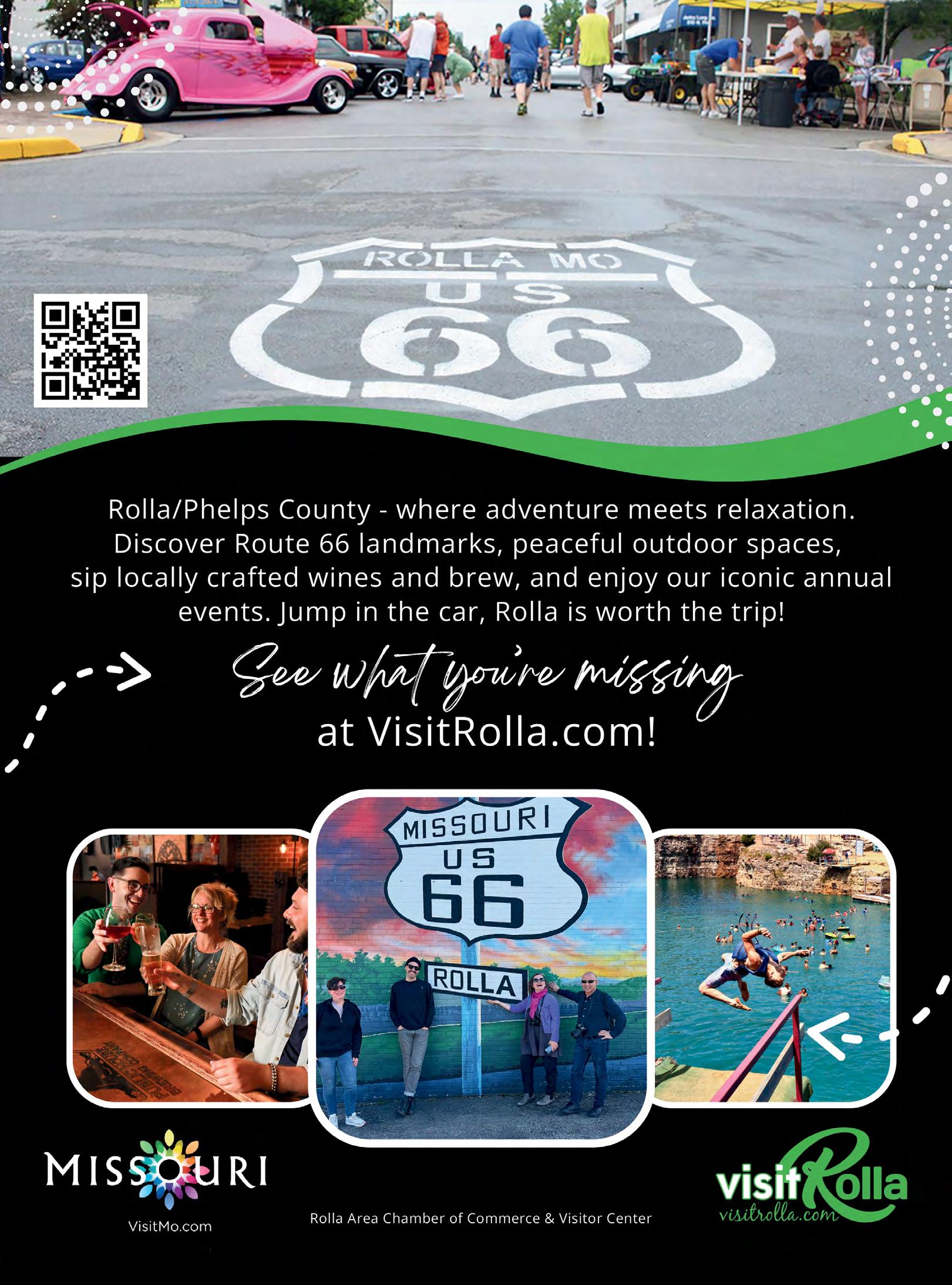

Get your kicks in the birthplace of Route 66, where nostalgia and adventure meet. Explore classic diners, historic landmarks, and hidden gems that keep the spirit of the road alive. Here in the City of the Ozarks, it’s all about making it your own.

Get your kicks in the birthplace of Route 66, where nostalgia and adventure meet. Explore classic diners, historic landmarks, and hidden gems that keep the spirit of the road alive. Here in the City of the Ozarks, it’s all about making it your own.

Explore more at

SAINT ROBERT, MO Route 66

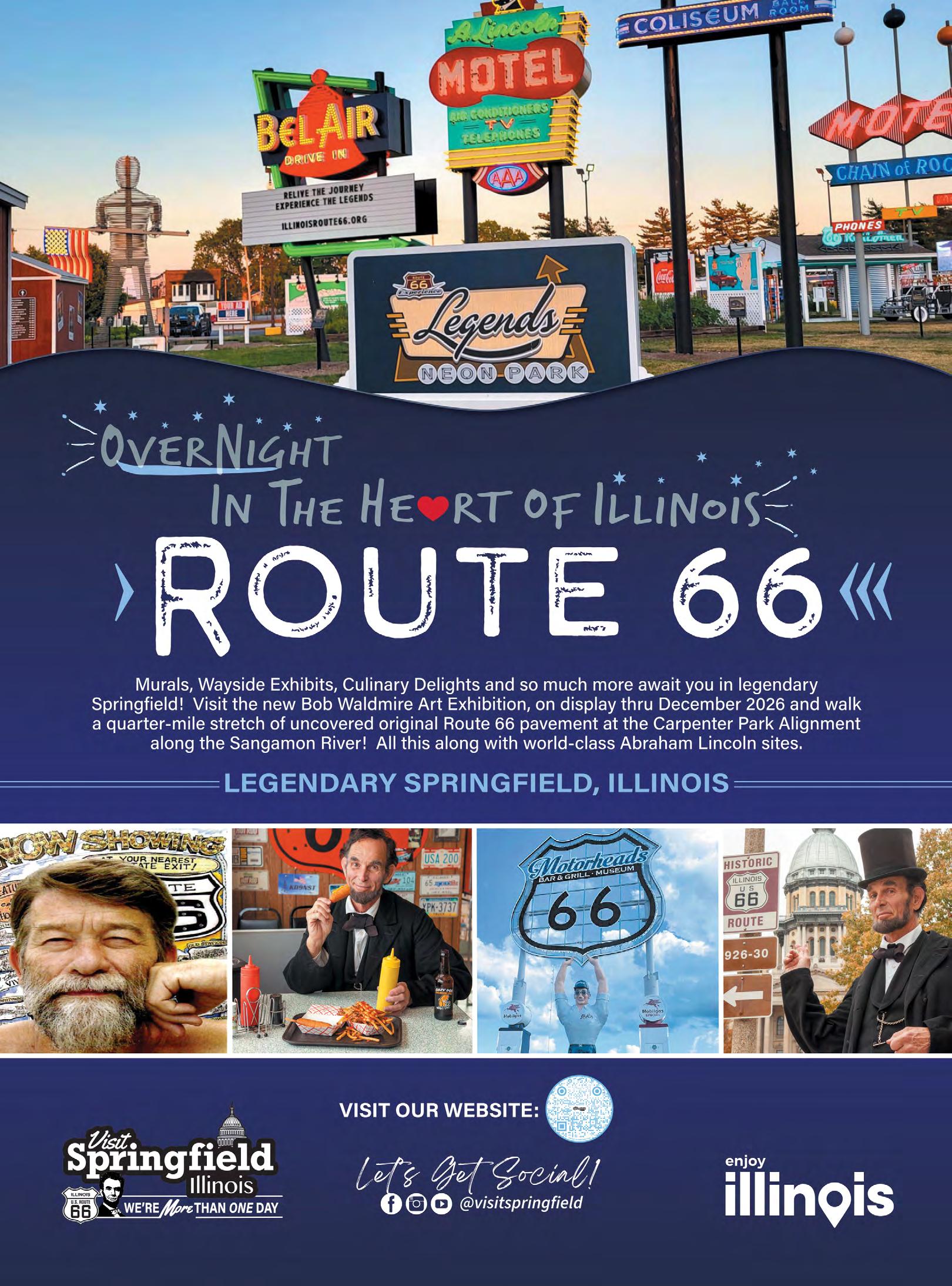

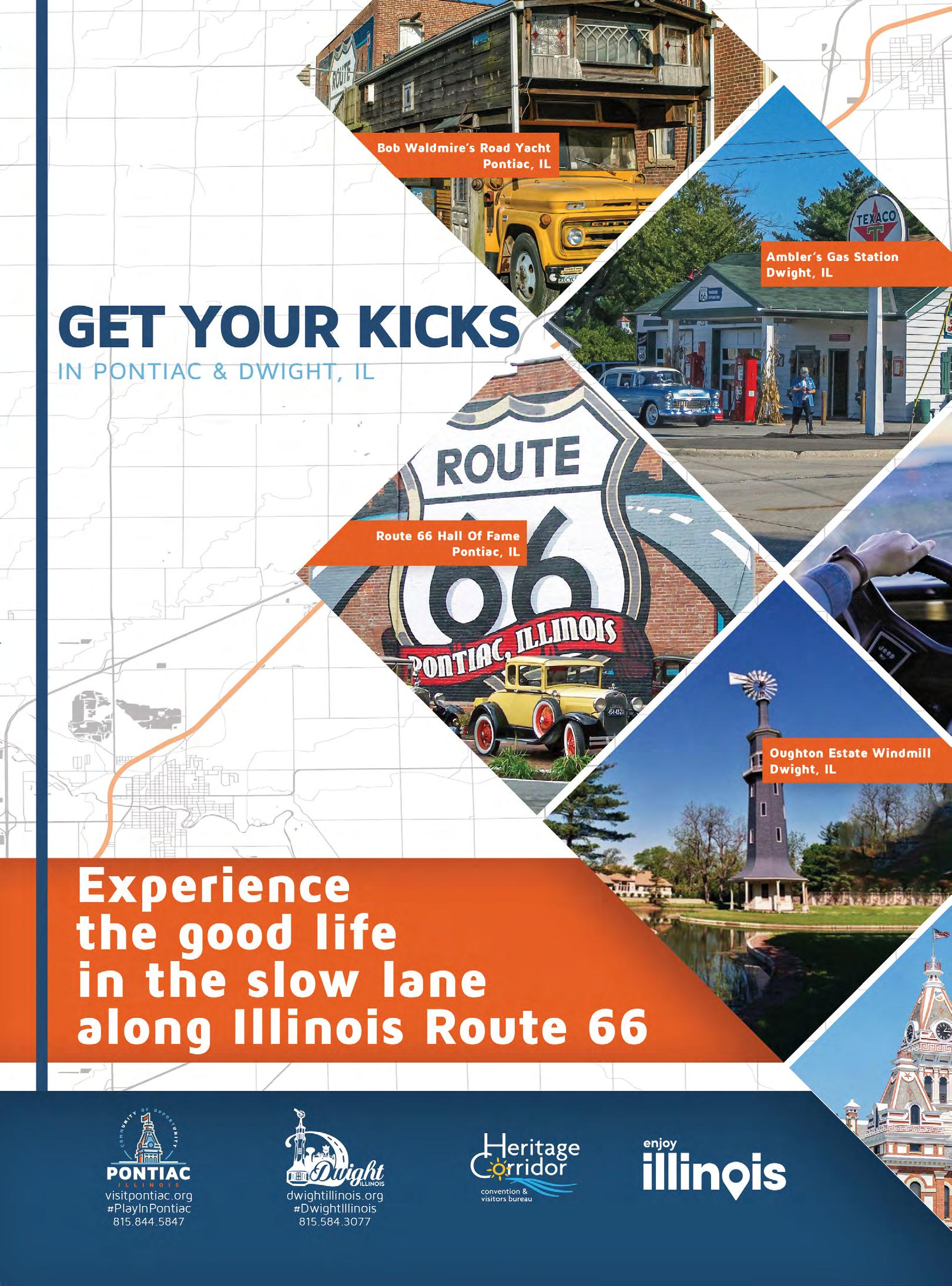

Skip the interstate and take a trip down Route 66 in Pulaski County, MO! Our 33-mile stretch of classic Americana and breathtaking scenery is filled with historic encounters, dozens of shops, selfie ops, and can’t-miss stops like the brand-new Route 66 Neon Park. This open-air museum features restored neon signs from the early days of Route 66. Discover unforgettable experiences only the Mother Road and Mother Nature can deliver.

Come Say “Hi” to Our Favorite Moms. Plan your trip at pulaskicountyusa.com

By Jake Baur

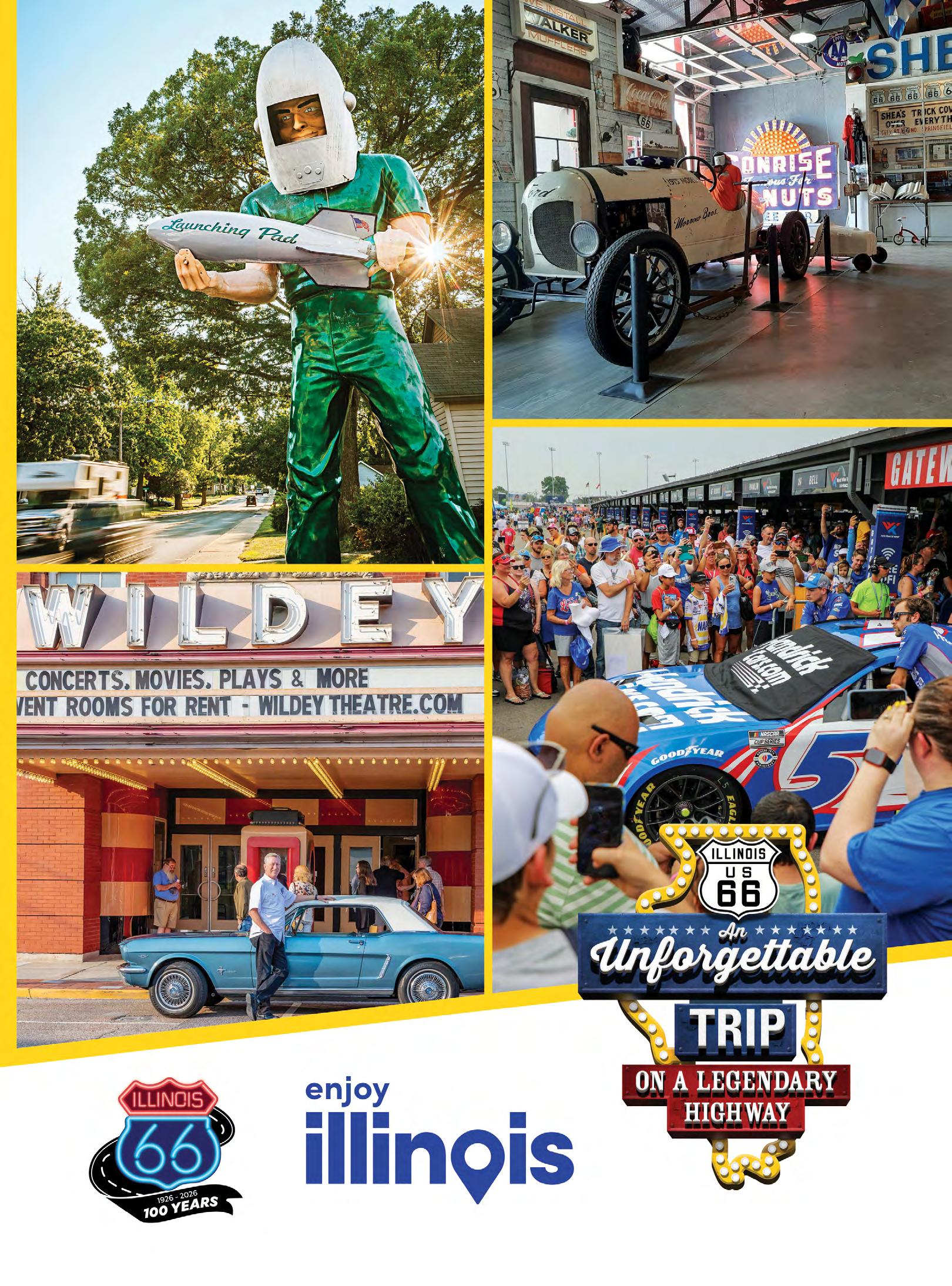

A roadside tribute to weird and wonderful Americana, the Pink Elephant Antique Mall in Livingston, Illinois, is a can’t-miss stop on Route 66. Housed in a former high school, this 30,000-squarefoot treasure trove offers vintage oddities, classic candy, and even a retro diner. But the real magic is outside, where a huge pink elephant, numerous fiberglass giants, and a flying saucer turn nostalgia into a roadside spectacle worth the detour.

By Abigail Singrey

Opened in May 2021 by passionate local entrepreneur Heather Linville, Wildflower Cafe has quickly become a Tulsa hotspot along America’s Mother Road. Set in the trendy Meadow Gold District, the vintage-chic space is more than a café, it’s a bright, community-driven haven with a story all its own. Like so many dreamers before her, Linville carries on the tradition of welcoming both locals and travelers into the warmth and charm of her inspired vision.

By Brennen Matthews

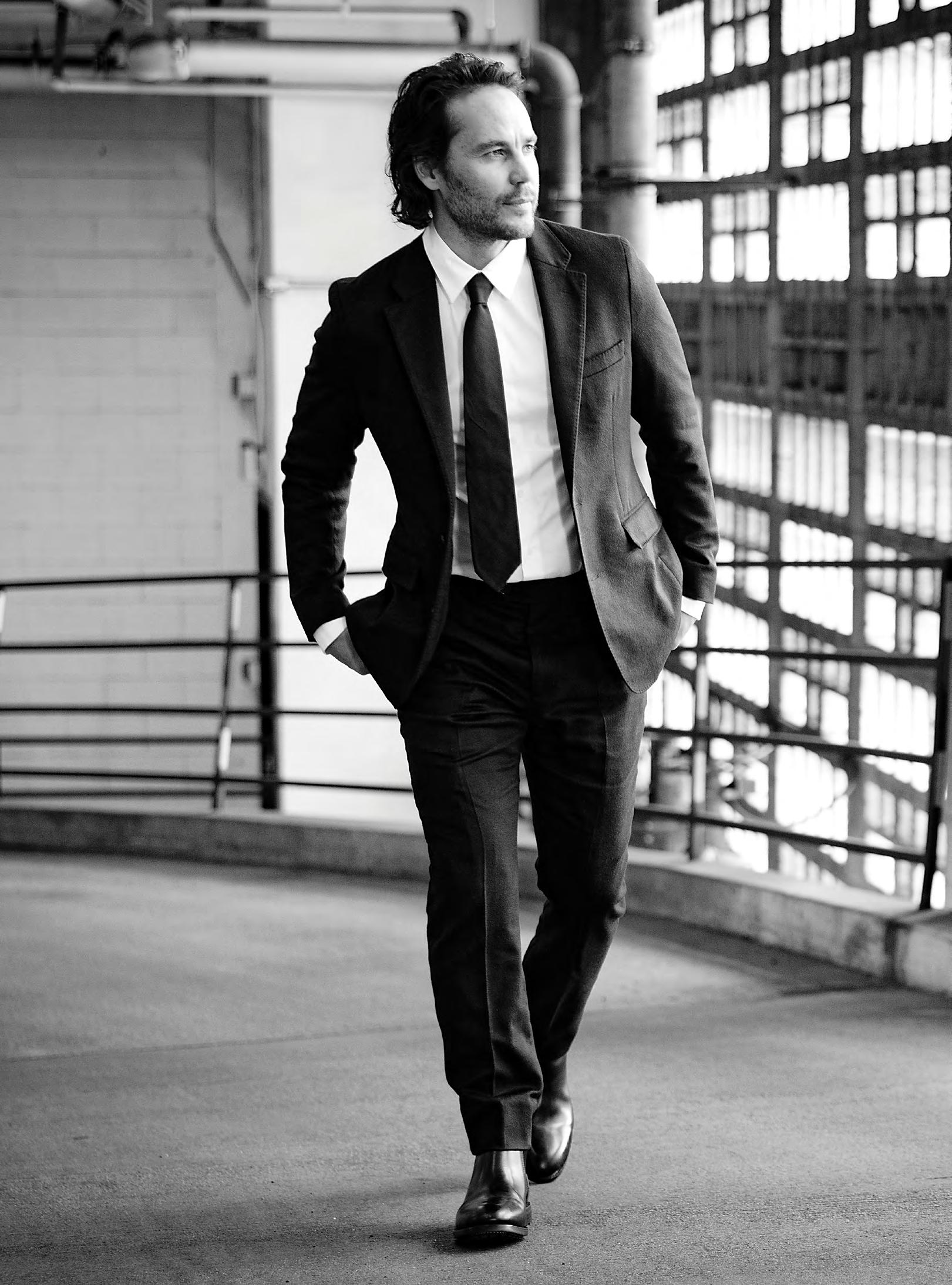

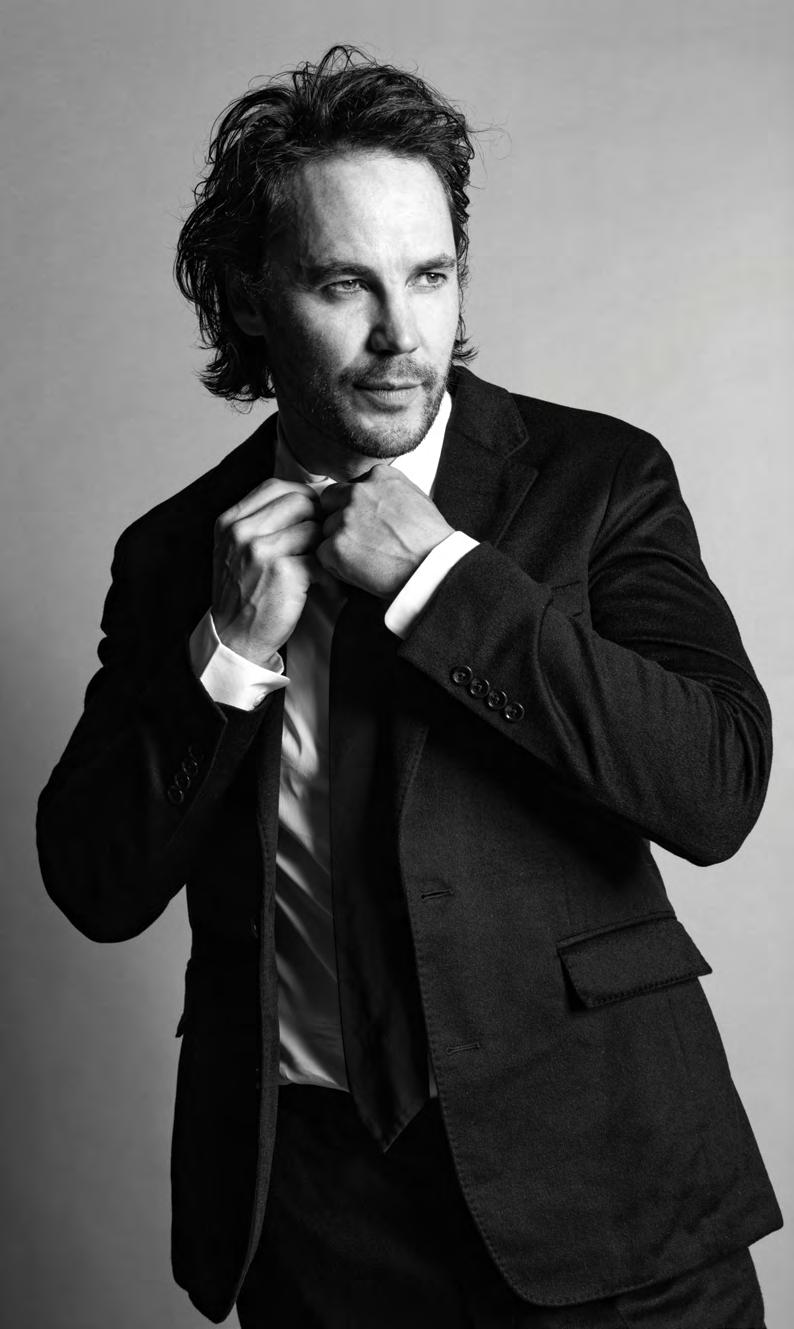

Before he was Tim Riggins, Taylor Kitsch was a broke dreamer sleeping on the New York subway. But grit, charm, and a Texas-sized screen presence launched him from modeling gigs to Friday Night Lights fame. This story follows Kitsch’s wild ride from small-town heartthrob to gritty roles in Bang Bang Club , Painkiller , Terminal List , and beyond. Still carving his path, Kitsch brings the same intensity offscreen as he does to every unforgettable performance. In this rare interview, get to see the softer side of one of Hollywood’s most intense, talented actors.

By Jake Baur

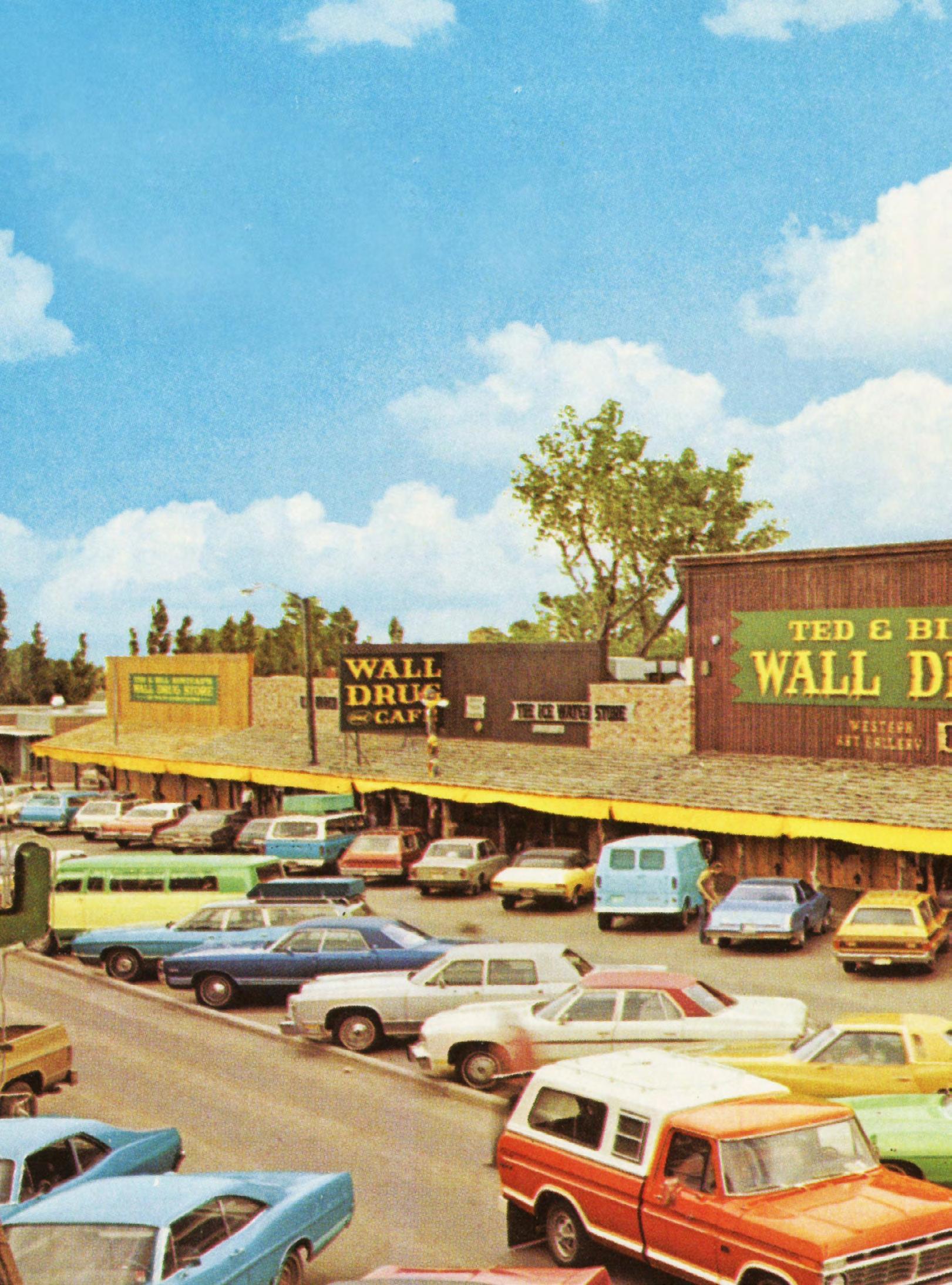

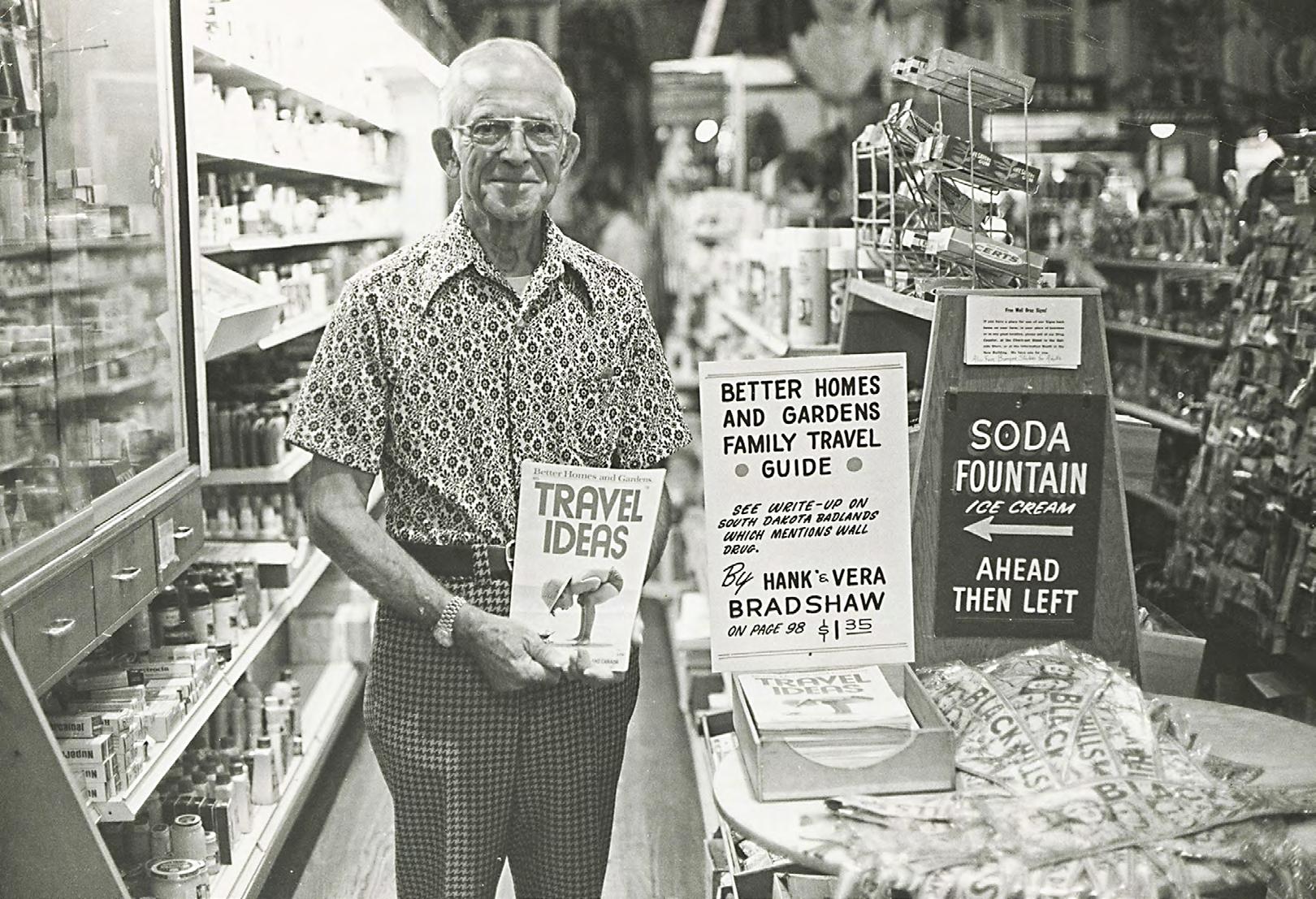

Born in 1931 as a tiny drugstore in Wall, South Dakota, Wall Drug became a legend thanks to a simple pitch: “Free Ice Water.” Ted and Dorothy Hustead’s simple but creative signs drew travelers off the highway, and over time, the place has exploded into a 76,000-square-foot wonderland of Western kitsch, and photo ops galore. This destination captures the spirit of classic highway culture—where charm, grit, and a great gimmick still go a long way.

By

Eva Massey

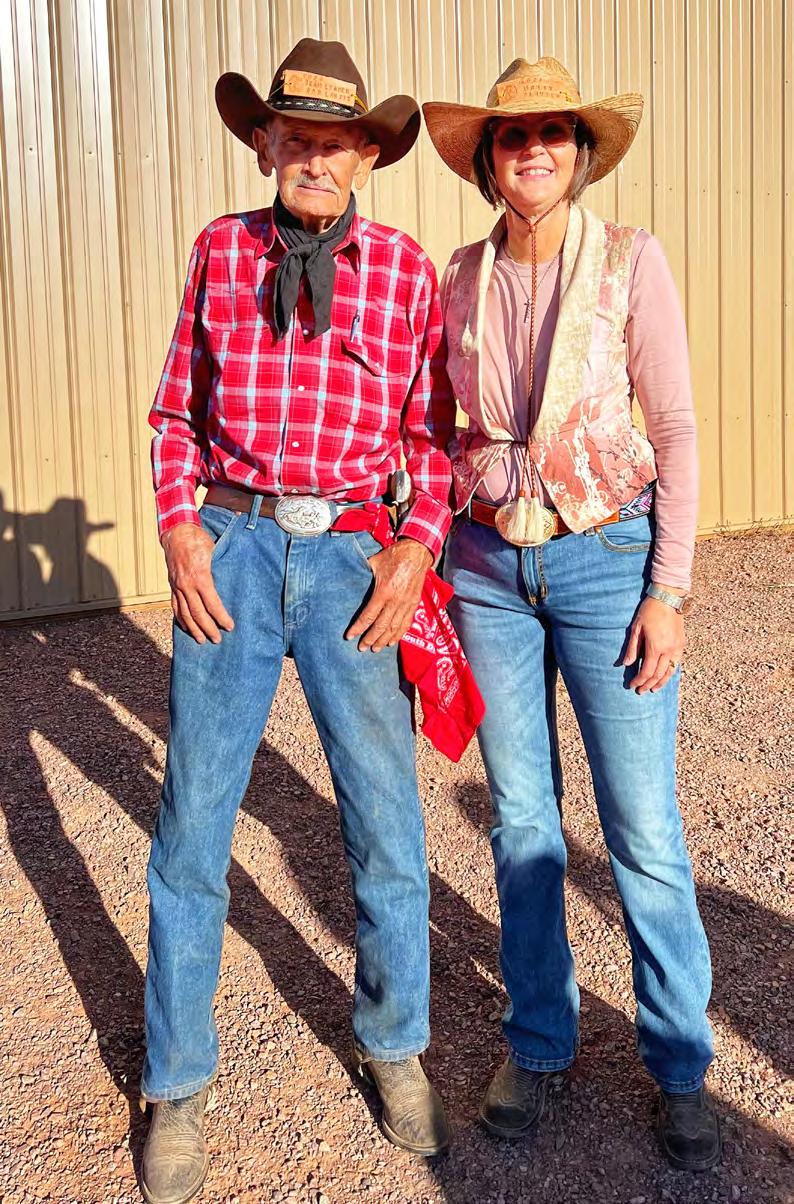

Bob Lantis was a fixture at South Dakota’s famous bison roundup, a man who knew the Wild West like the back of his hand. What animal represents the spirit of the West—and America—more than the mighty bison? From dusty trails to thundering herds, Bob’s story is full of heart and unforgettable moments. Though he’s no longer riding the range, his legend and the bison roundup live on.

“Mega Mayor” in Uranus Fudge Factor and General Store, St. Robert, Missouri. Photograph by David J. Schwartz – Pics On Route 66.

In 2021, as the world grappled with closed borders and disrupted traditions, our annual pilgrimage down Route 66, a journey we’d come to know like the back of our hand, was suddenly off the table. For years, the storied highway had been our summer escape: neon signs, vintage diners, and weathered landmarks guided us through America’s heartland. But that year, the map changed. With the U.S. border shut, we turned our gaze inward, setting out on a road trip that would reveal to us the hidden, quirky, and heartwarming treasures of Canada’s own historic and scenic routes.

From the quiet charm of Ontario’s old stagecoach trails and its dramatic lakeside shorelines and across the wide-open prairie highways like the Red Coat Trail and Highway 2, Canada proved itself a worthy, and wonderfully surprising, substitute. Small towns welcomed us with murals, oddball statues, and museums that told of pioneers, poets, and dreamers who’d left their mark on the land. The road offered up gold we’d never expected, and nowhere was that clearer than on a sunny afternoon in southern Saskatchewan.

We were cruising west under an impossibly blue prairie sky, the kind that makes the horizon seem endless, when we rolled into blink and you’ll miss it, Ponteix. And there he was: Mo, the Plesiosaur. Towering beside the road, Mo’s long neck and smiling face were impossible to miss. He was incredibly loveable and nothing if not DIY. This prehistoric marine reptile wasn’t just a fibreglass curiosity; Mo was inspired by real history. In 1992, local farmer and amateur fossil hunter Peter Hryciuk uncovered the fossilized remains of a Plesiosaur near Ponteix. This remarkable find, thought to date back 70 million years to a time when the prairie was a vast inland sea, captured the imagination of the small town.

The discovery sparked pride in Ponteix, and the community rallied to honor its prehistoric claim to fame. With local fundraising efforts and support from regional tourism and heritage groups, the idea for Mo the statue was born. Designed to celebrate the town’s unique link to the ancient sea, Mo was sculpted to be both educational and eye-catching—a way to draw travelers off the highway and into Ponteix’s story. Unveiled in the late 1990s, Mo quickly became a beloved landmark, standing not just as a nod to the past, but as a symbol of small-town spirit and curiosity.

That day, standing beneath Mo’s gaze with the sun warm on our faces, we realized something: Canada’s back roads weren’t just a consolation prize, they were a revelation. Our borders may have been closed, but the road, like our own all across America, still had magic to share.

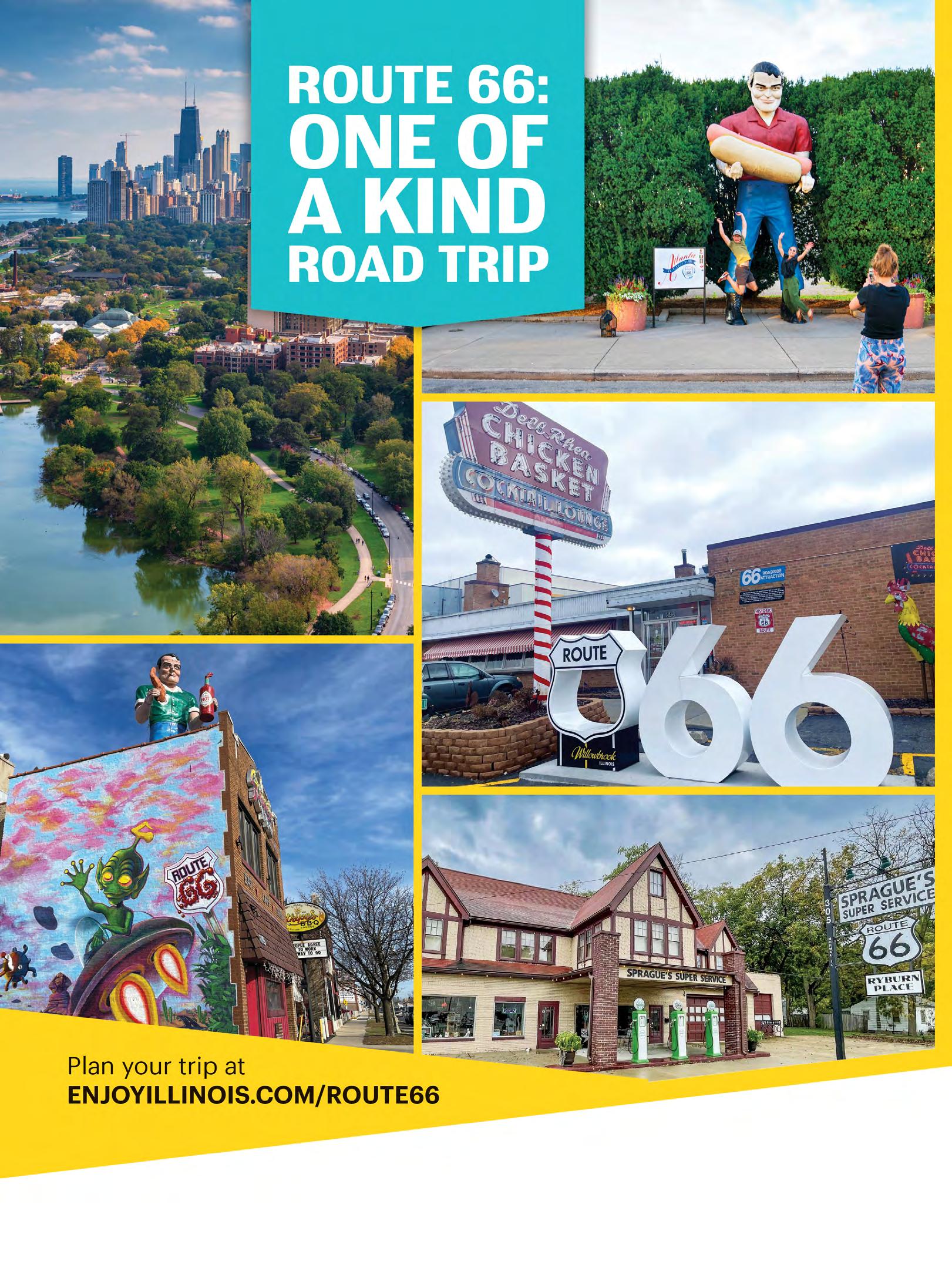

In this edition — our Americana issue — we feature stories both along and beyond Route 66 that celebrate the incredible journey our nation has taken, and in many places, continues to live out today. From the sprawling wonderland of Wall Drug in South Dakota, where free ice water and five-cent coffee are just the beginning, to the playful Pink Elephant Antique Mall along Southern Illinois’ stretch of Route 66. These destinations invite travelers to slow down, explore, and connect with local stories. These larger-than-life attractions are more than quirky photo ops — they’re part of the country’s spirit of imagination, humor, and hospitality, and they define the American road trip.

This has always been one of my favorite annual issues, and I hope that as you dive in, you’ll feel inspired to hit the road and discover the magic for yourself. So, as you map out your own travels, remember to leave room for the unexpected. The spirit of the road lives on in these icons and discovering them is part of what makes an American road trip unlike any other.

Blessings,

Brennen Matthews Editor

PUBLISHER

Thin Tread Media

EDITOR

Brennen Matthews

DEPUTY EDITOR

Kate Wambui

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Nick Gerlich

LEAD EDITORIAL

PHOTOGRAPHER

David J. Schwartz

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Tom Heffron

DIGITAL

Yasir Ahmed

ILLUSTRATOR

Jennifer Mallon

EDITORIAL INTERN

Sojourner Crofts

CONTRIBUTORS AND PHOTOGRAPHERS

Abigail Singrey

Byron Banasiak

Chandler O’Leary

City Museum

Diego Delso

Dreamstime

Emma Steinmetz

Eva Massey

Hustead Family

Jake Baur

John Smith

Kate Matthews

Michael Muller

Tomasz Wozniak

Editorial submissions should be sent to brennen@routemagazine.us.

To subscribe or purchase available back issues visit us at www.routemagazine.us.

Advertising inquiries should be sent to advertising@routemagazine.us.

ROUTE is published six times per year by Thin Tread Media. No part of this publication may be copied or reprinted without the written consent of the Publisher. The views expressed by the contributors are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, or service contractors. Every effort has been made to maintain the accuracy of the information presented in this publication. No responsibility is assumed for errors, changes or omissions. The Publisher does not take any responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts or photography.

Explore new immersive exhibits and experience the history, art and culture of the American West at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum on Route 66 in Oklahoma City, since 1955.

Route

66 has always been America’s most eccentric highway—a winding ribbon of asphalt where the unusual and the extraordinary feel right at home. It’s a road that celebrates the offbeat and encourages visionaries to make their claim. So, it’s only fitting that in St. Louis, Missouri, where the Mother Road once carried dreamers westward, stands one of the highway’s most delightfully bizarre attractions: the City Museum. The 600,000-squarefoot building is a giant playground with enormous slides, a labyrinth of tunnels to crawl through, and two real airplanes to explore, amongst many other exciting attractions. In other words: this massive playground is not just fun for the kids; it is a spot for everyone curious and young at heart.

2011, at a construction site in a bulldozer that had rolled over. He was only 61. Unsurprisingly, the legacy of Bob Cassilly lives on in City Museum, and Rick Erwin, the museum’s creative director, is filling his shoes well. Erwin has many ideas to continue adding to the zany collection of the museum: a labyrinth on the fourth floor that they’ve been working on for about six years with an 80-foot-slide inside, as well as a mini-Ferris wheel that he imagines would be fun hanging off the side of the building. Installations are made of limestone, plaster, rebar, concrete, and iron, and museum guests can climb, slide, swing, jump, and explore every nook-and-cranny of the massive space.

However, long before its debut as a museum of play, the building began its journey in 1922 as the International Shoe Company. The factory was eventually closed in 1987 and sat mostly vacant until 1993 when artists Bob and Gail Cassilly bought the old building at a price of 69 cents a square foot and breathed life back into it.

Bob Cassilly was more than just an artist—he was an architectural alchemist who saw potential where others saw debris. At the age of 14, he started to regularly skip school and began an apprenticeship with renowned sculptor Rudy Torrini. Soon, with his training and untamable imagination, Cassilly would make his own mark, creating largerthan-life public installations. But it was his masterwork, the City Museum in St. Louis, that truly embodied his creative philosophy. Working alongside his wife Gail and a dedicated crew of artisans, Cassilly transformed the abandoned shoe factory into an ever-evolving playground of possibilities, where industrial salvage became artistic salvation. He had an uncanny ability to see the whimsical in the worn-out—old shoe chutes became thrilling 10-story slides, architectural remnants morphed into climbing structures, and discarded machinery found new life as artistic marvels. For Cassilly, the world wasn’t bound by conventional uses; every object held potential for wonder, if only you dared to reimagine it. Sadly, Cassilly’s life was not to be a long one. He was found dead on September 26,

Unlike a typical museum, you won’t get kicked out for touching the exhibits here. In fact, you are encouraged to be part of the art. “When people get in here and they make sound and they are the movement, that’s when it’s all jiving, and it’s all working together,” said Erwin. This was the vision that Bob Cassilly always desired. “Bob… he was always jealous of music. The idea of music is—it goes in your ears and it’s inside you and you feel it. That’s what he wanted with the sculptures and stuff,” continued Erwin. “He wanted people to be able to get inside them and feel them, be a part of them.”

Today, Erwin tries his best to keep to the original vision that Cassilly had for the museum, even as the business and demands grow. One of the first things he did when he started in 2006 was to remove the map directories. They were costly and their largest trash item, but really, he wanted people to get lost. “It was kind of the idea that Bob wanted. He wanted you to explore and find your way. We don’t wanna tell you what to do,” said Erwin. “We should just let you play and figure it out. City Museum has always been the place that lets you grow in confidence.”

Like Route 66 itself, this architectural wonderland defies easy description and demands to be experienced, promising visitors the same sense of wonder and discovery that has drawn adventurers to the historic highway for generations. As you journey down the Mother Road, consider stopping by this unique, otherworldly adult playground, and experience one man’s enduring vision of what a museum could be.

Located only a halfhour drive from the Pacific Ocean — and right along the home stretch of Route 66 — is South Pasadena, California. Brimming with architecture, landmarks, and people who have stories to tell, there is one historic building that stands out among the rest in this charming town. With a pale pink exterior, greenand-white striped awnings, and an authentic neon sign, Fair Oaks Pharmacy and Soda Fountain is not simply another store along the roadway but a true multifaceted experience from the past.

Dating back to 1915, it was originally known as the South Pasadena Pharmacy; later, it became the Raymond Pharmacy and, since the ‘40s, has been known as the Fair Oaks Pharmacy. Opened by Gertrude Ozmun — a prominent entrepreneur of her time who even has a road named after her a few blocks down from Fair Oaks — it served as a pharmacy and soda fountain to the local community. It soon grew in popularity as Route 66 brought travelers through the area. Now an icon from a bygone era, Fair Oaks continues to serve up a whole host of amenities, treatments, and sweet concoctions; novelty toys and treats; custom remedies for people and pets alike, and not to mention a good deal of history on display in their small archive museum. Under the careful watch of the Shahniani family since 2005, the iconic spot is in good hands.

“My mom is a pharmacist, so growing up we’ve always owned different pharmacies. When my parents would own and operate a business, my mother would be the pharmacist and do all the pharmacist things and my father would run the front end,” explained Brandon Shahniani, the current co-owner, alongside his mother Zahra and brother Ash. “They were looking for a new business to purchase, and they came upon this really weird, really cool soda fountain that was a retail store and a restaurant but also had a working pharmacy in the back, so they thought it would be a great idea to purchase this place. It was a perfect situation for both of their careers.”

With authentic phosphate recipes dating back to the ‘40s and the soda fountain’s original operator’s guide passed down from owner to owner, the pharmacy holds steadfast in its tribute to the past. “Fair Oaks Pharmacy is a fully immersive experience,” continued Shahniani.

“The whole point of Fair Oaks Pharmacy is that we want you to be able to step inside and feel like you’re stepping back in time to something that is authentically from where it originated. We have lots of things that we do that keep it fully immersive. Obviously, the ambience is already there, but we also try to understand the lingo that they used back in the day. If an older gentleman comes in, we want him to be able to order a drink the way that he did back in the day.”

As such, it is not uncommon to hear terms like two-cent plain or black cow getting thrown around inside Fair Oaks, and every new employee learns the lingo in order to serve anything from a local favorite — a Shirley Temple — to the lesser-known Roy Rogers drink and everything in between.

Although the name and ownership of the business has changed over the decades, one thing has remained true: the undeniable, old-fashioned charm that it brings to all those who enter. “It’s one of those things where it’s so important to maintain and preserve, because the whole point is, you have something magical that you get to step into, and there are not a lot of places that [still] exist like that,” said Shahniani. “It’s crucial to keep everything as neat and preserved as possible because we care about the future. We want it to last longer. I want Fair Oaks Pharmacy to outlive me. It was here way before I was born, and I want it to be here way after I’m dead. But I’m responsible for that happening while I’m alive.”

Fair Oaks has been a corner store staple in South Pasadena’s historic business district for over 100 years and continues to make history as it brings new generations back to simpler times. Whether you are in need of some custom-made medicines, feel the hankering for an authentic, old-fashioned milkshake, or just want to explore some genuine history along California’s Mother Road, this is an ideal place to stop and stay awhile.

America has always loved a creative gimmick, and in the middle of the 20 th Century, the country had a good one. Muffler Men — fiberglass “Giants” manufactured during the 1960s and 70s, and designed to be eye-catching advertising for roadside businesses, towered across the American landscape. And motorists loved them, but by the 1980s, they had begun to disappear, but not totally!

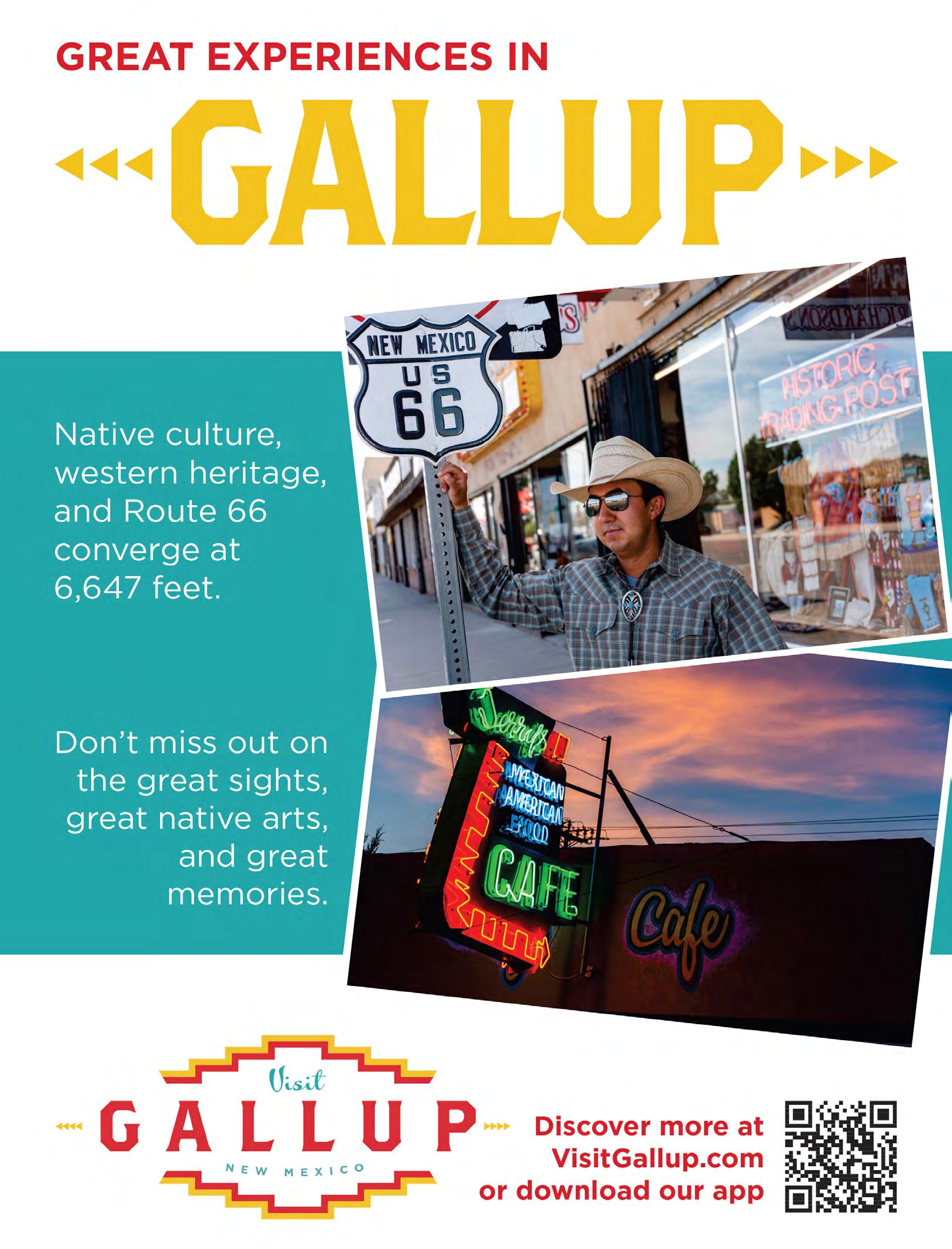

Some of these gentle behemoths have earned national fame: the Gemini Giant in Wilmington, Illinois; the Paul Bunyon Giant in the small town of Atlanta, Illinois; and the Lauterbach Tire Man in Springfield, Illinois. But one towering figure has yet to receive the recognition he deserves. Allow us to introduce you to Gallup, New Mexico’s largest resident— “Dude Man.”

Surveying downtown Gallup from his lofty perch, the cowboy stands tall atop the roof of John’s Used Cars. Wearing a Western hat and a holstered six-shooter, his square-jawed, broad-shouldered appearance channels the classic heroes of old Hollywood Westerns. Yet there’s a hint of melancholy in his expression as he stares solemnly at his empty palms.

“He once held a rifle in his hands—someone told me he had a rifle up there—but I’ve never seen it,” said John DeArmond, the previous owner of the used car dealership. Rifle or not, Dude Man fits perfectly into Gallup’s iconic Western identity. The town—often referred to as the heart of Indian Country—is a place where hats, boots, and turquoise jewelry are part of everyday life. Historic downtown Gallup lies just south of Route 66, the BNSF Railway, and I-40, all running parallel through town.

“It’s the Indian capital of the world,” DeArmond said. “[And] Richardson’s Trading Post down the street has the best Indian jewelry.” From his rooftop post on West Coal Street, Dude Man enjoys the best view in town—a sweeping look over Pueblo Revival architecture, busy streets, and the daily mix of tourists and locals.

DeArmond, a Gallup native now retired and living in Arizona, left school after seventh grade to enter the working world. By the 1970s, he had become a self-made businessman with a used car dealership and a business partner. “The Dodge dealership [where he was, in Gallup] went out of business, so we bought

the big man at the auction,” he explained. “That Dodge dealership was only ten blocks away, and I had to pay a company to take him apart… in three pieces. They hauled him on a flatbed trailer and then they put him back together. It’s been good for advertising, and it’s just been an eye-catcher,” he continued. “All my customers— most of them are now Hopi off the reservation—they love him to death.”

In over fifty years of ownership, DeArmond has only had the big man repainted twice, each time at a cost of about $2,500. “He had to be painted while he was on the ground, and I went back to the original colors of red, white, and blue,” he said. “But there is a bullet hole right in his head. Someone shot him with a .22 [caliber], but that bullet hole happened years ago. I just left it alone. It’s not very big.”

Locally, in a nod to DeArmond’s reputation, the giant became known as “Honest John” after losing his original “Dodge Man” moniker in the 1970s. But in 2013, a Roadside America blurb referred to him as Dude Man, and the name stuck with travelers ever since. But whatever you call him, he’s a popular figure. “People come from all over, asking questions and wanting to know more about him. They get out of their cars and take pictures. We have a population [in Gallup] of 20,000 during the week, but on the weekend we’re at 100,000 because all the Indians come off the reservation to trade.”

DeArmond sold the business to his children in the early 2000s, keeping it in the family. His son has since passed away, but his daughter Evonne has continued the legacy. “She’s done a real good job with it,” he said. “Evonne likes [the statue] there because it draws a lot of traffic. I had an offer one time, around ten thousand dollars, and I said, ‘It’s not for sale.’ I’m just kind of sentimental about him after all these years.”

Standing sentinel over Gallup’s distinctively Western downtown, the Dude Man does what all good Giant Men do best—lend a protective air to their surroundings and hold still for photos.

A vivid reminder of a bygone era, this gentle giant has stepped comfortably into the 21st Century—still smiling, even if only in spirit. After all, as everyone knows, cowboys seldom show their real feelings.

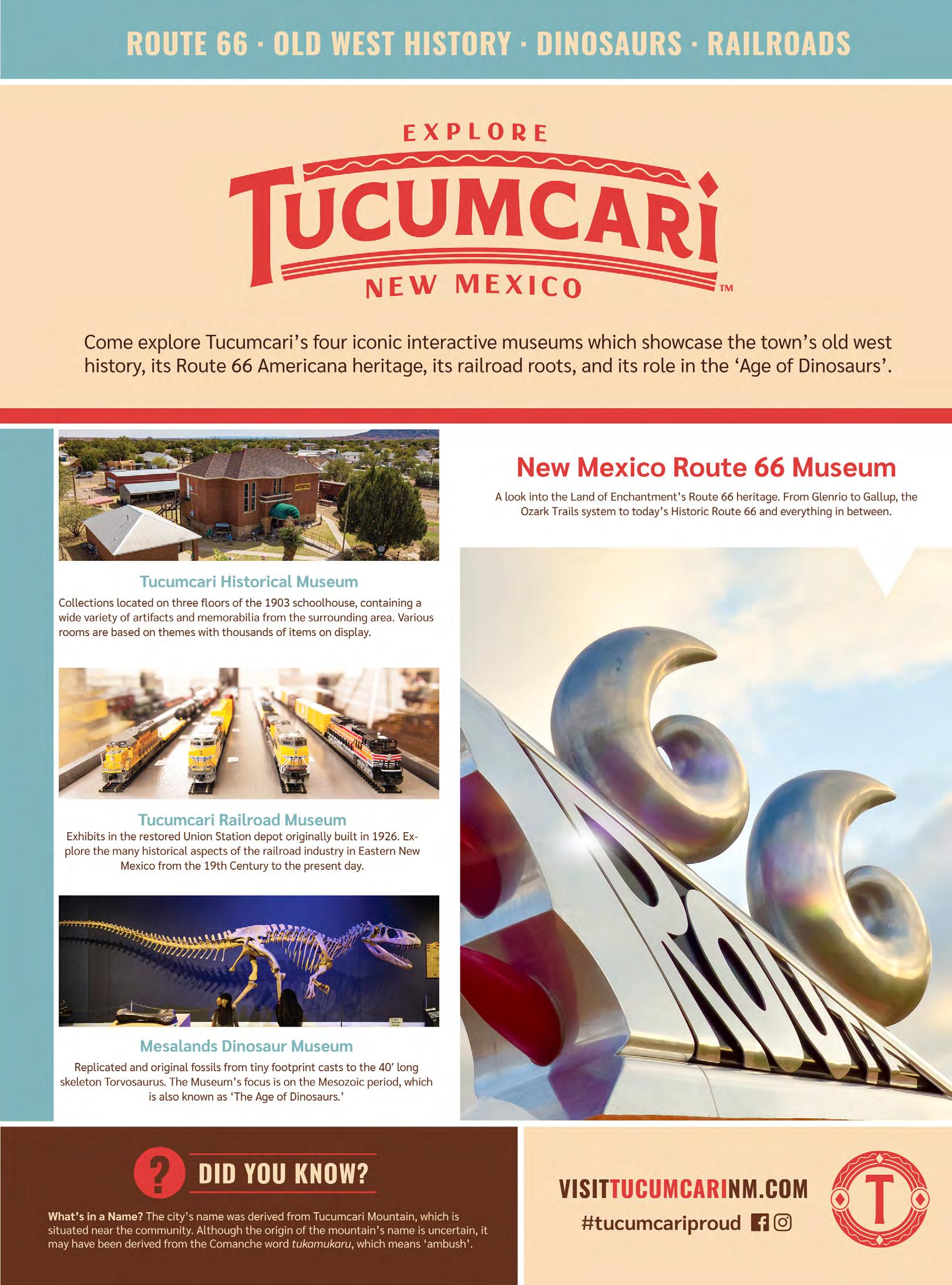

Along Route 66 and Interstate 40 through the High Plains of the American Southwest, if lucky, travelers might still catch sight along the sometimes lonely highway of one or two remaining signs adorned with the reassuring words, “Tucumcari Tonite!”

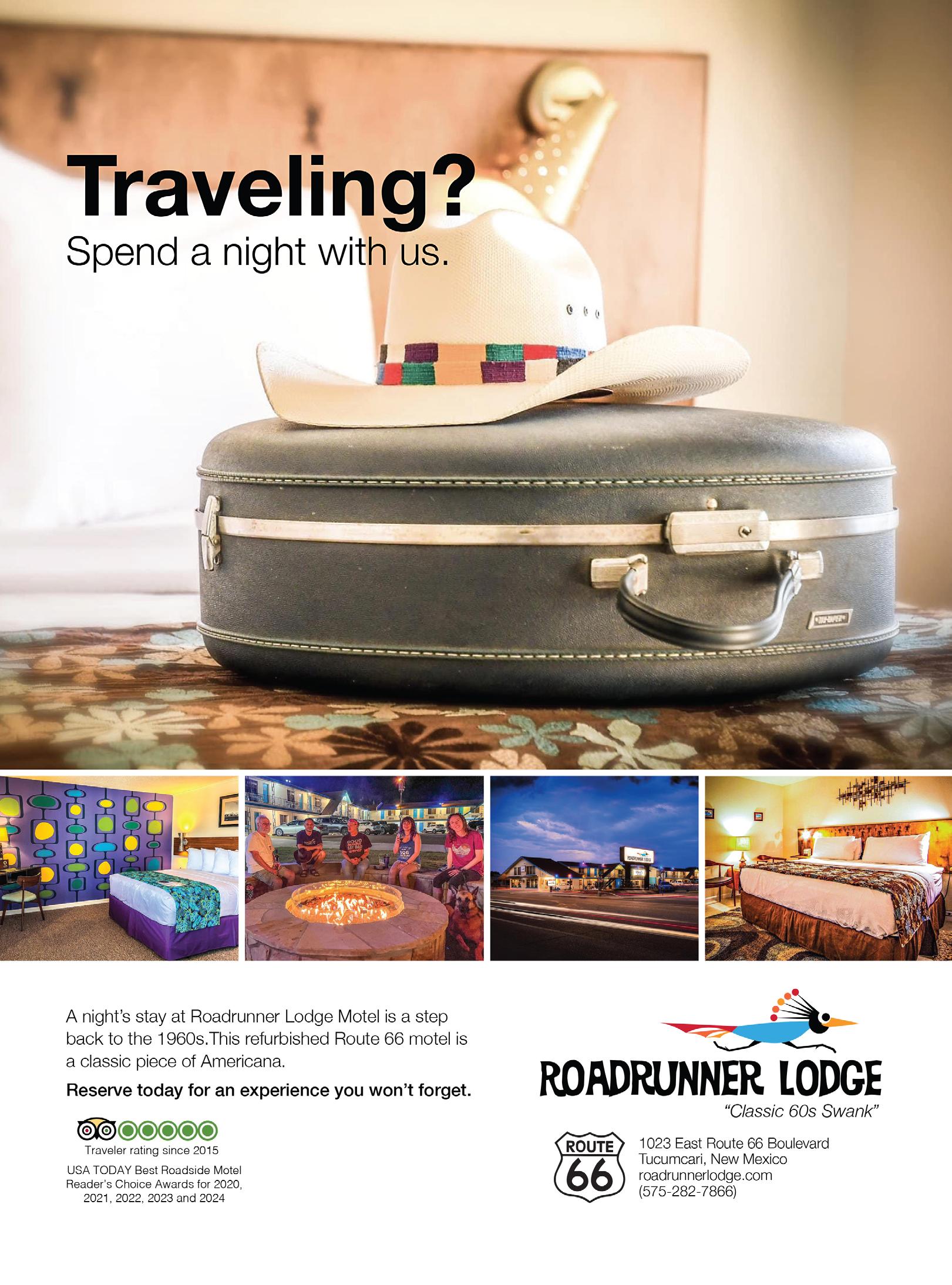

This wildly successful slogan campaign once put Tucumcari, New Mexico, on the map as “the Gateway to the West,” with many miles worth of advertisements championing the little city’s 2,000 available motel rooms. Although Tucumcari later experienced economic hardship due to the interstate bypass and the loss of commercial tourism, its rich history is encapsulated in the quirky “Tucumcari Tonite!” slogan that still welcomes weary travelers. It’s a slogan that refuses to die, as dedicated community members of Tucumcari work diligently to reinvigorate its use.

motels themselves, such as the famed Blue Swallow Motel, and ever popular Roadrunner Lodge Motel, the “Tucumcari Tonite!” signs themselves became a memorable attraction for highway travelers. However, the success story of the “Tucumcari Tonite!” campaign has not always been linear. In the 1950s, following President Eisenhower’s development of a new interstate highway system, I-40 passed through the fringes of the city limits. An original alignment of the Mother Road remained in use, still funneling some travelers through the downtown area, yet, even so, the city suffered a drastic drop in tourism, with the local population declining slowly but steadily ever since the 1950 census.

Tucumcari during the second half of the 20th Century began to resemble a ghost town, a hub of decaying Route 66 cultural artifacts enduring a long economic downturn.

Tucumcari began its status as a national crossroads and hub for American travelers when the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad founded a construction camp there in 1901. In the early 20th Century, the camp grew into a town, using the names Ragtown, Six Shooter Siding, and Douglas before settling on Tucumcari, which became a regional railroad center. Tucumcari then became a popular motorist stop after the original alignment of Route 66 came through in 1926. Nicknamed Route 66 Boulevard, the Mother Road ran east-west right through the center of town, where dozens of motor services such as motels, restaurants, and gas stations sprang up to welcome travelers.

It was the plethora of neon-draped accommodations that inspired the “Tucumcari Tonite!” signs though, and it didn’t take long to gather notoriety. In the mid-20th Century, the signs began to pop up along the long miles approaching Tucumcari, with an invitation for tourists to stop, relax, and rent a room for the night. As the largest stopping point on the highway between Amarillo, Texas, and Albuquerque, New Mexico, motorists took comfort from the catchphrase with a collective sigh of relief that there would be motel rooms ready and waiting for them after a long day on the road.

“It was miles from anywhere, so back in the day when people couldn’t travel as far, Tucumcari was the most logical place to spend the night,” said Connie Loveland, director of the nonprofit organization Tucumcari Main Street. In tandem with the vintage charm of some of the town’s neon-kissed

And yet, even amid downswings, the spirit of Tucumcari endured, partly due to the continued fascination with the fading but iconic signs leading to the town’s borders.

In 2008, members of the Tucumcari Main Street organization voted to replace the former “Gateway to the West” slogan with a revitalized promotion of the “Tucumcari Tonite!” catchphrase, in the form of four new billboards. In addition to the endorsement of colorful murals, the renovation of vintage motels, and the restoration of neon lights downtown, community supporters continue to promote Tucumcari’s endurance and long-term association with Route 66.

“Tucumcari is one of the few places that has embraced Route 66 and worked to keep the neon and to keep that traditional feel, which continues to draw people in. Local businesses have done such a good job of preserving their buildings and preserving the spirit of Route 66,” said Loveland. “I’ve always said that the communities along Route 66 are really like an extended family, and the places that have embraced that have been really successful.”

As the 2026 centennial of Route 66 approaches and the momentum breaks through the quiet of the past couple years, travelers and inhabitants alike along the Mother Road are celebrating those communities that have endured through all the ups and downs. Tucumcari is undeniably one of these gems, and “Tucumcari Tonite!” reminds us that there are still comfortable, vintage (and renovated) motel rooms a-plenty to draw us back to the picturesque little High Plains city along the Route.

By Jake Baur

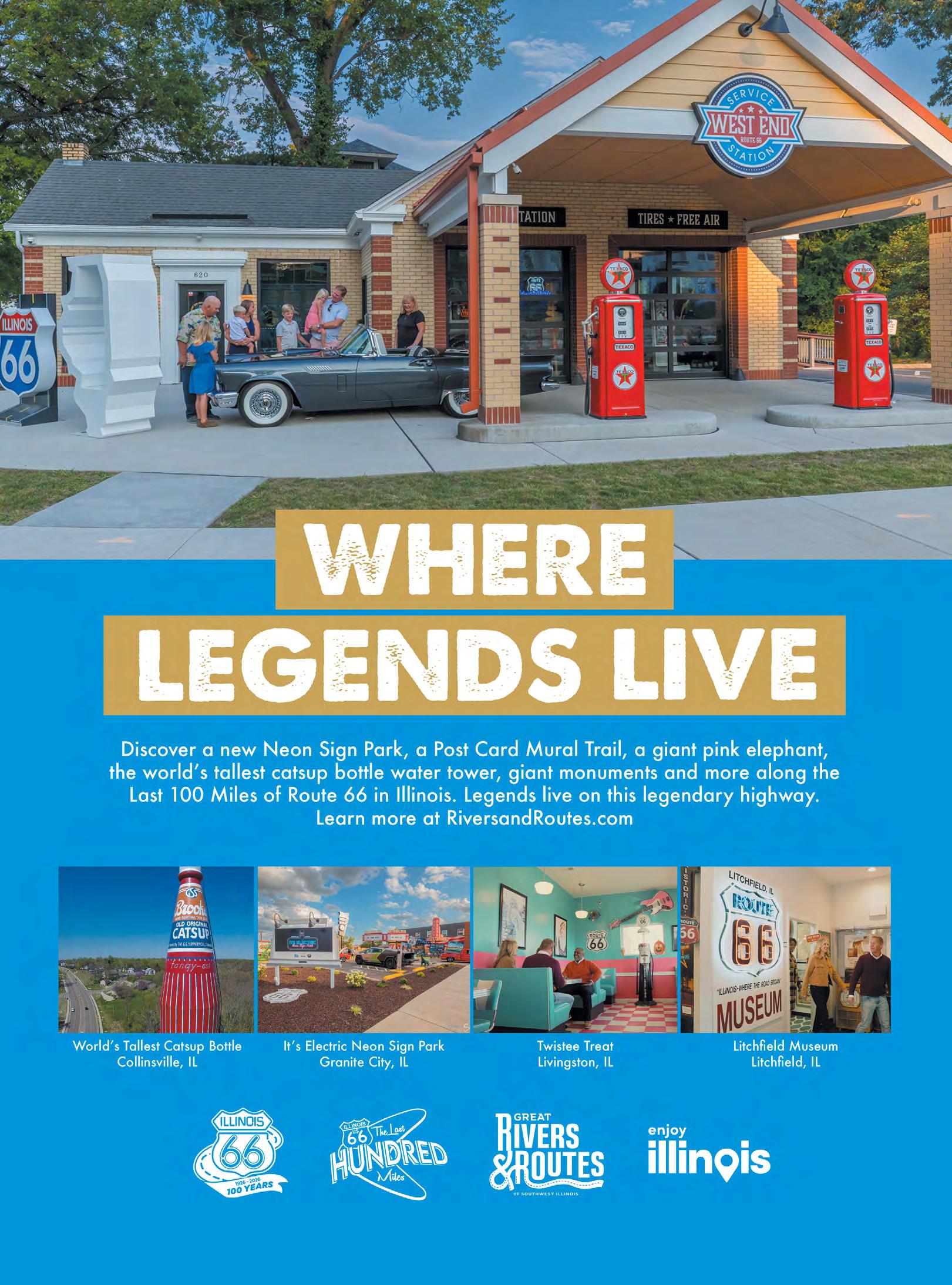

As Historic Route 66 begins in Chicago and winds its way through approximately 300 miles through Illinois to the Southwest, it passes through dozens of little communities, each with their own charm and draw. That is one of the things that makes the iconic road the quintessential Great American road trip. And one of these towns is Livingston, where an unmissable roadside gem awaits travelers. The Pink Elephant Antique Mall stands as a vibrant testament to the Mother Road’s golden age of quirky attractions and roadside magic.

Like many towns along the Midwestern stretch of Route 66, Livingston’s history is rooted in farming and mining. It was a Southern Illinois destination that worked hard to offer motorists everything that they may require when on the road. Today, the Pink Elephant continues this tradition of welcoming road-trippers, though instead of gas and provisions, it offers something even more precious: a perfectly preserved slice of mid-century roadside culture.

These eye-catching outdoor features aren’t just Instagramworthy photo opportunities — they’re thoughtful homages to the wonderfully weird and kitschy attractions that once dotted America’s historic highways.

And the man responsible for capturing and preserving the very spirit of Route 66’s golden age of roadside entertainment in Livingston? Davey Hammond. An entrepreneur, a gogetter, and a visionary, Hammond worked hard to make something of himself. “I worked for the city in the water and sewer field; I didn’t make a lot of money, but I always had side projects,” said Hammond. “Dad and I used to flip houses. We did like 20-something over the years.” Along the way, Hammond also invested in some bigger properties.

“I originally bought a building in Hamel, Illinois. It was also on Route 66 and we called it the Princess Antique Mall. That was in 1997. About a year after we opened the Princess, we bought the Colosseum Ballroom in Benld, Illinois, in 1998. We had it as an antique mall, also,” continued Hammond. The Colosseum had notoriety; it had served as a dance hall in its heyday and hosted big stars like Duke Ellington, Chuck Berry, and Ike and Tina Turner. Plus, it was a lot larger of a building at 10,000 square feet. Hammond sold the Princess a year after purchasing it and focused on maintaining the Colosseum.

Things were going well for Hammond and the antique business. Then, in 2004, an opportunity presented itself. “A guy I used to do some work for, Gary Levi, left a message on my cell phone saying, ‘Davey, the Livingston High School is going up for sale. You can probably get it cheap. See ya.’ That was the message,” remembered Hammond. “So, I went and picked up my dad, Dave — who was my partner

by Dreamstime.

in everything I did — and we go and drive around the building a few times. He finally asks, ‘What are we doing?’ and I tell him, ‘I’m gonna buy this building!’ He started laughing and goes, ‘Well, do what you want.’”

The school was built in 1926 but closed in 2004 because there weren’t enough students in attendance. Located just off of Interstate 55, the school had great traffic and visibility, so when it went to auction in 2005, Hammond jumped and placed his bid. And they accepted his offer at just over $64,000 — a steal!

“Shortly before I bought it, they’d just spent $750,000 putting in a new gym floor, a new roof on the building, new furnaces, so I really lucked out,” said Hammond. “The bleachers were hand-built and bolted into place. Sturdy. You could’ve parked a diesel truck on them. We had to tear all that out. So, then we had them both going for a while: the Colosseum in Benld and the school in Livingston. But man, it was just running us so thin. The power bills at both places were just astronomical. So, we ended up putting the Colosseum up for sale and moved everybody to Livingston. That was the summer of 2005,” said Hammond. It was a beneficial move from the get-go, with sales almost doubling thanks to the newfound traffic along the route.

Now, with over 30,000 square feet at his disposal, Hammond had a vision to make this property something special. “Me and my late wife, Cheryl, would always go to Branson, Missouri, and different places. And we wanted to make our own tourist attraction. Get a lot of people to come out and put a smile on their face, basically,” recalled Hammond. While the antique dealers settled into their new booths in the old gymnasium, Hammond got to work collecting all the weird, kitschy stuff that he would need for outside.

“The pink elephant was at a Mexican Restaurant in Granite City, on Route 66, believe it or not. Well, my late-wife bought it for me for Christmas when we still owned the Colosseum. She put a big red bow on it and everything,” reminisced Hammond. The rest is history: when they made the move to the old high school in Livingston, the pink elephant found its

new home on the front lawn, and the place finally had a name. “You can see the big pink elephant a mile down the interstate, and that really started drawing people in.”

The surfer dude, now proudly standing next to the building, was the first statue Hammond actually acquired for the property. “I was calling around trying to find something for sale: a [muffler man] giant. I found the surfer dude in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. He’s a statue that was used in the movie Flatliners with Kiefer Sutherland and Julia Roberts. We eventually get him on the trailer, which of course he’s bigger than by at least six feet, but we got him strapped down and headed home,” said Hammond. The trip home highlighted what Hammond already suspected: people were captivated by giant statues. “We’d be going down the interstate and people would start passing us, except then they’d slow down and let us pass them again so that they could get a good look at the statue. They’d start laughing, wave, and give us the thumbs up, stuff like that all the way home,” Hammond laughed.

It was Hammond’s desire to make the Pink Elephant Mall a kitschy Route 66 roadside attraction that drew him to collect the many other statues that occupy the old schoolgrounds. Collecting and transporting these statues was both a chore and an adventure. The Twistee Treat ice cream cone building? Hammond’s late-wife found it for sale on Craigslist for $25,000 in Livingston, Ohio, in the winter of 2007. Upon arrival, however, the 25-foot-tall cone was in far worse shape than promised. “This thing literally has saplings, about six inches in diameter, growing in and out of the window openings, which are all busted. The back’s all rotted off, and there’s rabbits living in the top of it. And the whole thing is frozen to the hillside,” recounted Hammond. With his excellent negotiating skills, Hammond got the cone’s price down to $13,500. But driving that decrepit, extra wide, 14-foot load through icy, winter storms was an experience. “There’s at least a foot of snow on the ground, and while I’m going down the road, the [cone’s] insulation is flying out and sticking in my brother-in-law’s radiator and wrapping around his antennas on his truck, cuz he’s following me with the other parts,” continued Hammond. They managed to get all the pieces safely back to Livingston, although when it was time to rebuild, the whole back of the cone had to be handmade again due to its rotted wood.

Hammond then had the vision for a diner. He searched for one of the old stainless-steel diners, but never found one in decent enough condition. So, he built one. Designed it and laid out the plans, too. The diner, a 1950s-style spot serving supreme burgers and delicious ice cream, is now attached to the Twistee Treat ice cream cone building.

As for the Muffler Man statue, now painted as a Harley Man, Hammond bid on the statue on eBay, but it didn’t pull enough money, so the owner kept it. A year later, the same owner called Hammond and asked if he was still interested, and even offered to deliver it; this was a proposition Hammond could not refuse.

What about the Futuro House, one of the less-than100-made flying saucer homes designed by Finnish architect Matti Suuronen in the late 60s? Through tireless investigation and his entrepreneurship spirit, Hammond found the owner of one in Springfield, Illinois, asked if they wanted to sell it, and got the spaceship in 2009. Each section of the UFO weighs about 1,200 pounds. “Those pieces were huge. We kind of stacked the pieces inside each other for the drive home,” recalled Hammond. There’s now a plexiglass door installed so mall goers can peek inside.

The easiest statue to pick up? The 13-foot tricycle that a local craftsman, in his 90s, built. Alvin and the Chipmunks are another giant addition. There are other giant animal statues, as well: a giraffe, hippo, and rhino can be found on premise. And there’s a giant Donald Trump statue. The Pink Elephant Mall isn’t making a political statement with this figure; they’re using it as an opportunity. Next to the statue is a sign that reads, ‘Love him or hate him, it’s still a good photo-op.’ Where else can you express your political opinion while standing next to a 20-foot statue of the 45th and 47th President? These attention-grabbing features do more than just entice passing motorists to stop for a photo opportunity; they serve as loving tributes to the wonderfully wacky roadside attractions that once characterized America’s historic highways.

Equally impressive as the giant statues outside, but hidden from the public, was a side project Hammond was working on. “And then I made a four-bedroom house on the third floor. There’s about 5,000 square feet up there. Me and my dad did all of it: wired it, plumbed it, put all the walls in. Turned out beautiful. Really, super beautiful. I had big columns, and I put a lot of crown molding in the place. The rooms were huge—huge! The master bath even had a garden tub.” The Hammonds finished building the house in 2011 and lived on the third floor off-and-on until they sold the property to Tonia and Wayne Pickerill in 2022. “During chemo, Cheryl couldn’t make it up the three flights of stairs, but when she was better, we’d move back in.”

“I started working for Davey, running the ice cream shop, [around] the end of 2008,” recounted Tonia Pickerill, current owner of the Pink Elephant Mall. “Then he added the diner on, and I took over managing that for him. I hired, fired, ran it, advertised, all of it. It was like my baby. And then I did bookwork for him for the antique mall, as well.” Tonia’s responsibilities ramped up working both sides of the business, and her love of the building and business grew. In 2020, she took over leasing the diner from Hammond, right as the world was shutting down due to the COVID pandemic. The two worked out an agreement, but times were

tough for everyone. Then in December 2022, the Pickerills bought the entire business.

After selling, Hammond moved, and currently owns and operates a restaurant and bar, Pirates of the Mississippi, with his wife, Bernice, in Batchtown, Illinois. When Hammond sold the Pink Elephant, he made sure to take the giant Uniroyal Gal statue with him, one of about a dozen left and modeled after Jacqueline Kennedy. She’s now painted as a pirate and is proudly displayed at their restaurant, along with several other life-sized pirate statues.

But the mall is in excellent hands, and the Pickerills plan to continue Hammond’s legacy of making the Pink Elephant a worthwhile stop. They’ve already extended the patio in front

of the diner to provide more outside seating. And they’re also part of Harvest Hosts for any motorhome enthusiasts who need a place to park in Southwest Illinois overnight.

The Futuro House will soon be more than just a picture-op.

“We’re going to start converting it into an Airbnb.

The interior will be retro and furnished with 1960s aesthetic and memorabilia,” said Wayne. Their ideas expand even further than the Airbnb, though, with hopes to eventually build a Route 66 putt-putt golf course on the property, with each hole representing a different state and the things that they’re known for down the Mother Road. They know what they have is special, and they plan on capitalizing on it.

“We’re the landmark for the town. The Pink Elephant put Livingston on the map,” said Tonia.

And then there’s the interior of the Pink Elephant Mall: a treasure trove showcasing wares from more than 50 antique dealers, with items thoughtfully arranged from floor to ceiling. This expansive marketplace offers an impressive selection of antique furniture, vintage jewelry, rare collectibles, classic glassware, and nostalgic memorabilia. Beyond antiques, visitors can discover modern home décor, artisanal candles, and unique home goods. The mall takes special pride in supporting local vendors, ensuring a diverse

shopping experience that appeals to both serious collectors and casual browsers alike. “Of course, we have antiques, and there are collectors for these items. But it’s the stuff from the 1970s and 1980s that really sells here because its people coming in and seeing their childhood: ‘Hey, I remember this!’ or ‘My grandma had that!’ Yea, that nostalgia moves better,” added Wayne.

As relators have said for decades, “Location, Location, Location,” and both the original and current owners of the property recognize the significance of the mall’s enviable spot. “I’m extremely proud to have established something that’s now part of America’s history on America’s Mother Road. Yeah, it means a lot to me,” said Hammond. “Everything about this place makes you smile.” He accomplished what he set out to do: he made the Pink Elephant a must-stop destination for anyone seeking to experience the true spirit of Route 66. “And they work really well together, being a Mother Road destination and an antique business. Most of the people that are doing old 66, they’re wanting to explore the United States and see hometown America. A lot of them celebrate the 50s and 60s and coming here is a flashback to that for them,” continued Wayne. In this way, the Pink Elephant doesn’t just preserve antiques within its walls — it preserves the very spirit of the Mother Road’s golden age of roadside entertainment.

by Tomasz Wozniak

In the unexplored reaches of Nevada’s silver territory, Tonopah’s story began with a wandering burro and a frustrated prospector. In the spring of 1900, Jim Butler picked up a rock to hurtle at his stubborn, straying pack animal, only to find himself holding a piece of destiny. This humble rock would transform this quiet stretch of desert into one of Nevada’s most significant silver discoveries, as Butler learned his find contained ore worth more than $200 per ton (equivalent to about $7,500 per ton, today). Within just one year, the area yielded $750,000 in silver and gold, earning Tonopah its nickname as the “Queen of the Silver Camps.”

The period between 1901 and 1921 marked Tonopah’s golden age of mining, though silver was its true treasure. During these two decades, the region produced nearly $121 million worth of ore, establishing itself as Nevada’s secondmost productive silver location after the famed Virginia City mines.

As Tonopah’s silver wealth transformed the desert landscape, the need for sophisticated accommodations grew. In 1907, a group of local businessmen — George Wingfield, Cal Brougher, Bob Govan, and US Senator George Nixon — funded the construction of the Mizpah Hotel, a venue that local newspapers would soon herald as ‘the finest stone hotel in the desert.’ Construction began that year under the guidance of renowned architect Morrill J. Curtis, although George Holesworth, a Reno architect and contractor, designed the building. The resulting five-story masterpiece showcased both architectural ambition and engineering innovation. The building’s structural integrity was ensured by 18-inch-thick granite walls and reinforced concrete, while its aesthetic appeal was achieved through a sophisticated combination of stone veneer on the main facade and brick on the side and rear walls. Stone piers marked the street-level entrance, with symmetrically grouped windows adorning each floor above.

When the Mizpah Hotel opened its doors on November 17, 1908, its $200,000 investment was evident in every detail.

The five-story, Victorian-styled hotel stood as Nevada’s tallest building until 1927 and was a true testament to Tonopah’s prosperity. The hotel boasted modern Victorianera luxury amenities: solid oak furniture, brass chandeliers, hot and cold running water, all-electric lights, steam heat, ceiling-mounted fans, and notably, the West’s first electric elevator. Unlike the town’s numerous rooming houses that catered to miners and laborers, the Mizpah offered an elegant setting where business titans could negotiate deals and political leaders could forge alliances. Its opulent rooms and finely stocked bar created an oasis of sophistication in the desert, serving as both a symbol of Tonopah’s success and a catalyst for its continued growth.

The Mizpah Hotel’s prosperity ebbed and flowed with the mining town’s volatile boom-and-bust economy. And as the 20th Century drew to a close, the grand hotel finally succumbed to the town’s declining fortunes; by 2000, it was shuttered. The property went on to spend the next 10 years with its windows boarded and doors chained. Then the Clines, of Cline Cellar Winery in Sonoma, purchased the property and dove into renovations.

For Fred and Nancy Cline, the 2011 restoration of the Mizpah Hotel was far more than a business venture — it was a homecoming written in silver and stone. Nancy’s deep family ties to Tonopah stretch back to the early 1900s, when her grandmother Emma Bunting served as the first postal matron of nearby Goldfield and her great-uncle Harry Ramsey answered the siren call of the silver rush. Their commitment to Tonopah extends beyond the Mizpah’s careful restoration — they’ve also established the Tonopah Brewing Company and undertaken the renovation of the historic Belvada Hotel (across the road), too.

“The Mizpah is beautiful. [The Clines] wanted to use all authentic fixtures to keep it as close to the way it was when it was first built, while still making it current,” said Al Karsok, general manager of the Mizpah Hotel. “In a lot of the rooms we have claw foot tubs, which are original. All the plumbing fixtures are a Rolex brand that was manufactured back in the early 1900s; we went ahead and reworked them so that they meet today’s standards. A lot of the fixtures in the hotel are original antiques that have been reworked and brought up to code. It’s a Victorian feel with today’s amenities.”

“Tonopah is 230 miles from Reno and 215 miles to Vegas, and there’s nothing in-between. But here is this gem of a hotel that offers reprieve and comfort,” continued Karsok. “And you can sit in the Long Shot Bar and know that 100 years ago there were people in that bar doing the same thing: unwinding with a drink and meeting and talking with fellow travelers… It’s pretty cool, the history. And it’s a magical thing, too, how [the hotel] draws people in.”

Another claim to fame? The Mizpah Hotel was voted the #1 Haunted Hotel in the country by USA Today in 2018. “Our most famous ghost is ‘The Lady in Red.’ Her name was Eleanor. Her working name was Rose, and she was a prostitute,” explained Chavonn Smith, the Mizpah’s Sales and Front Desk Manager, who also facilitates the ghost tours. “Rose was stabbed and then strangled on the 5th floor by a client who believed that she belonged to him.” The Lady in Red has her own suite, which coincidentally is the hotel’s most popular room.

Other remaining spirits include a pair of children that haunt the 3rd floor and basement, as well as the ghosts of two miners who dug a tunnel, snuck into the hotel vault and stole everything, but were then shot by their third compatriot who got away with all the gold and was never found. “We also have a ghost book in the lobby where guests write about their supernatural experiences,” said Smith. “Overall, our ghosts are very friendly.”

All sorts of demographics are drawn to the Mizpah: historical connoisseurs who seek a glimpse of the past, paranormal aficionados searching for the adventure of a good haunting, weary road travelers who are simply looking for a delicious meal and comfortable place to lie their heads. Whatever the reason for your visit, the Mizpah welcomes you warmly. “It’s just the feel of it; you’ll have a story to tell others about. It’s not just a stay — it’s an event,” said Karsok.

More than a century has passed since its addition to the Nevada landscape, but in many ways, this is a historic venue that appears trapped in time, in all the best ways.

Photograph by David J. Schwartz - Pics On Route 66

Tucked away in the quiet town of Rolla, Missouri, there’s a roadside surprise that doesn’t blink, flash, or wave, yet commands attention all the same.

Here, on the grounds of the Missouri University of Science and Technology, a startling vision rises: Stonehenge. Not the one across the Atlantic shrouded in centuries of myth, but a meticulously crafted, half-sized replica of the ancient monument. As granite slabs arc into the sky, aligned in mysterious symmetry, the past feels unusually present. Surrounded by sleek academic buildings and the hum of modern life, this unexpected tribute to Neolithic engineering feels like a deliberate time portal, reminding us that wonder doesn’t always come with a signpost. Sometimes, it just rises from the ground.

The idea for Rolla’s Stonehenge first took root in the 1980s, championed by Dr. Joseph Marchello, then Chancellor of Missouri S&T. Bringing the vision to life was Dr. David A. Summers, now retired, a professor of Mining Engineering. He not only oversaw the construction but also played a key role in developing the innovative waterjet technology that was used to carve the monument’s granite stones.

“Joe was very interested in the science of early man and had already founded the Center for Archeoastronomy when he was at the University of Maryland,” said Summers. “When he came to Rolla, him and I met socially, and he mentioned that he always wanted to build a Stonehenge. We had been working with some people down in Georgia developing high water pressure means of cutting granite, so I had contacts in the industry. Before I knew it, I was on a committee, and we were designing the Stonehenge.”

The inspiration behind Missouri S&T’s Stonehenge traces back some 5,000 years to the windswept plains of Southern Britain where ancient peoples built one of the world’s most enduring mysteries. As societies shifted from hunting to farming, it became crucial to determine the best times to plant crops. Archaeologists believe that the ancient Stonehenge tracked the moon’s position in relation to four stones and a surrounding ditch to mark the changing seasons. Over time, additional stone rings were added around a central “altar” stone, aiming to improve the calendar’s accuracy. Yet, it wasn’t until the builders began observing the sun’s position, instead of the moon’s, that they achieved a calendar precise enough to identify exact days. The name “Stonehenge” itself means “hanging stone,” a nod to the distinctive lintels that cap the towering rocks.

Recreating even a half-scale version of Stonehenge was no small feat. Fortunately, timing and circumstances were on the university’s side. Missouri S&T was in the midst of building a new mining technologies facility, making it a practical choice to situate the monument on the same site. Sharing construction equipment helped reduce costs, while generous donations from alumni funded the remainder of the project, including wages for the students who played a hands-on role in bringing it to life. A professional crane operator was brought in to lift and position the massive granite slabs, but the rest of the physical work, especially operating the high-pressure waterjet cutting equipment, was carried out by students.

The granite used in Missouri S&T’s Stonehenge is a hard igneous rock quarried in Elberton, Georgia. The university

would have sourced the granite in-state, but at the time the monument was being drafted, the only granite quarry in Missouri was closed. Despite collaborating with the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, no suitable in-state alternative was found, so they looked outside. Once acquired, the granite was transported to campus by truck and rail. Missouri S&T’s Stonehenge became the first major structure carved using high-pressure water jets, developed by the university’s High Pressure Waterjet Laboratory within the Rock Mechanics and Explosives Research Center. This method marked a pivotal shift from traditional mechanical excavation to hydraulic cutting, a major milestone in mining. With only minor improvements over time, this groundbreaking technology remains largely the same today and has become standard across many excavation industries.

Dr. Summers, being a 9th-generation coal miner from the North of England and holding a doctorate degree in Mining Engineering from the University of Leeds, was no stranger to the original Stonehenge’s mining history. The replica needed to be accurate and able to stand the test of time.

“The outer ring, the big ring, was put in about six inches of concrete, and then filled in with another six inches of concrete to make sure they would never fall over,” said Summers. “Because it is a functional calendar that works, we were concerned about an earthquake, not being far from the Madrid fault, we knew there would eventually be quite a large one, and we wanted to be able to adjust it. When we cut the horizontal slab, we put recesses in the side so that you can put a jack in and move it around. That way you can adjust all of it if it goes out of alignment.”

The organizing committee was formed in 1982, the rock acquired in 1983, and rock cutting started in the fall of that year. Thanks to the university’s cutting-edge waterjet technology and the use of a crane, Missouri S&T’s Stonehenge major construction was finished in just six months and the monument dedicated on the night of June 20th,1984, in a ceremony that included John Bevan, a white-robed Druid from the Geffodd of Druids of the Isle of Britain, bringing an air of ancient ritual to the occasion.

“It was interesting because there was a lot of disbelief in the beginning with, ‘Why are you building this?’ or ‘Why are you doing this?’ and ‘It’s not gonna be that interesting,’ remembered Summers. “But then once we put it out, there was great interest, not just at the university level from the students, but also people in town. There was continuing interest, and I would be asked several times a year to talk to visiting groups.”

It’s not the neon-lit diner or vintage gas pump most travelers expect to find along Route 66, but that’s what makes Missouri S&T’s Stonehenge in Rolla so memorable. Rising from a university campus rather than a roadside field, this unexpected monument speaks to something deeper than nostalgia: the timeless drive to build, to innovate, and to leave a mark.

In the shadow of Stonehenge’s granite arcs, the past and present meet. It’s a reminder that along this legendary highway, wonder doesn’t always come wrapped in quirkiness or chrome. Sometimes, it arrives in stone, chiseled by students, lifted by cranes, and imagined by dreamers determined to make the impossible real.

Rollerz Only Car Show

Odd Lab Fire Performance

Live Music Exhibitors

Food Court Fireworks

Vendors

Family Friendly Fun

Tucumcari Railroad Depot 100 W. Railroad Ave.

Paid for in part by the City of Tucumcari Lodgers Tax

By Abigail Singrey

Tulsa, Oklahoma, holds a place of quiet reverence along legendary Route 66. Among its famed landmarks is 11th Street, a stretch of road that has undergone dramatic transformations over the years, mirroring the rise, fall, and resurgence of the Mother Road itself. Among the new businesses riding this wave of revitalization is the Wildflower Cafe, a cozy and vibrant eatery at 1306 East 11th Street. This humble address, steeped in history and a legacy of housing various businesses, has silently stood as a witness to the ebb and flow of 11th Street’s storied journey. By opening the Wildflower Cafe, owner Heather Linville joined a vibrant wave of visionaries breathing new life into the district, transforming what was once a symbol of decline into a thriving destination once again.

In the golden age of Route 66, which spanned from the 1930s to the 1950s, 11th Street was a bustling thoroughfare serving as a vital artery for travelers heading west toward California or east to Chicago. Lined with motels, diners, service stations, and mom-and-pop stores, neon signs would light up the night, advertising clean rooms, hot meals, and the promise of adventure. America was a much larger country in those days.

In 1934, amid the bustling heyday of 11th Street, Robert W. Brinlee, a long-time Tulsa wholesale grocer, opened the Brinlee Grocery and Market at 1324 East 11th Street. Next door, at 1302-1308 East 11th Street, James Calvin Meek and his family operated Meek’s Hardware & Furniture Company, with the space at the corner of 11th and South Peoria Avenue serving as an office building, accommodating various tenants over the years. Together, these businesses thrived, becoming cornerstones of the community, where locals and travelers alike found connection and commerce in the heart of Tulsa.

Then, came the advent of the interstate system. Businesses began to shut their doors as travelers opted for the faster, more efficient highways. The neon signs that once illuminated the night were dimmed, their messages of welcome fading into obscurity. After more than 40 years, the Brinlee store closed its doors in 1975, and Meeks Furniture followed shortly after, closing during the 1980s. By 1983, the building that had housed the Brinlee Grocery and Market was demolished and the property was converted into a parking area. In the early 1970s, the office building at the corner to the west at 11th Street and S. Peoria Avenue was purchased by Elmo Ray Ferrell, Sr. and converted into a restaurant named Mexican Fiesta, which later became Mark and Mary’s Good Food Cafe until 1991. In 1994, it was reopened as The Corner Cafe.

11th Street had become a shadow of its former self with many of its landmarks neglected or demolished and soon the area gained a reputation as the Red Light District. The

Mother Road in Tulsa had lost its luster and it seemed that 11th Street’s storied chapter had closed.

But then, several decades later, a resurgence began to take shape.

In 2009, the iconic 1930 Meadow Gold sign was officially restored and relocated to a plaza on 11th Street and Quaker Avenue. This site was the spot that the Brinlee Grocery store had once occupied. In 2007, Markham D. Ferrell — grandson of Elmo Ray Ferrell, Sr. — and now the third generation owner of this property, learned that the Meadow Gold sign was in need of a new home and donated the property to the City of Tulsa.

The reinstallation of the Meadow Gold sign wasn’t just about saving a historic artifact, it symbolized the beginning of 11th Street’s revitalization and the establishment of the Meadow Gold District, an area that stretches between Peoria and Utica Avenue. This act sparked renewed interest in honoring the street’s history and laid the groundwork for ongoing efforts to revitalize the area.

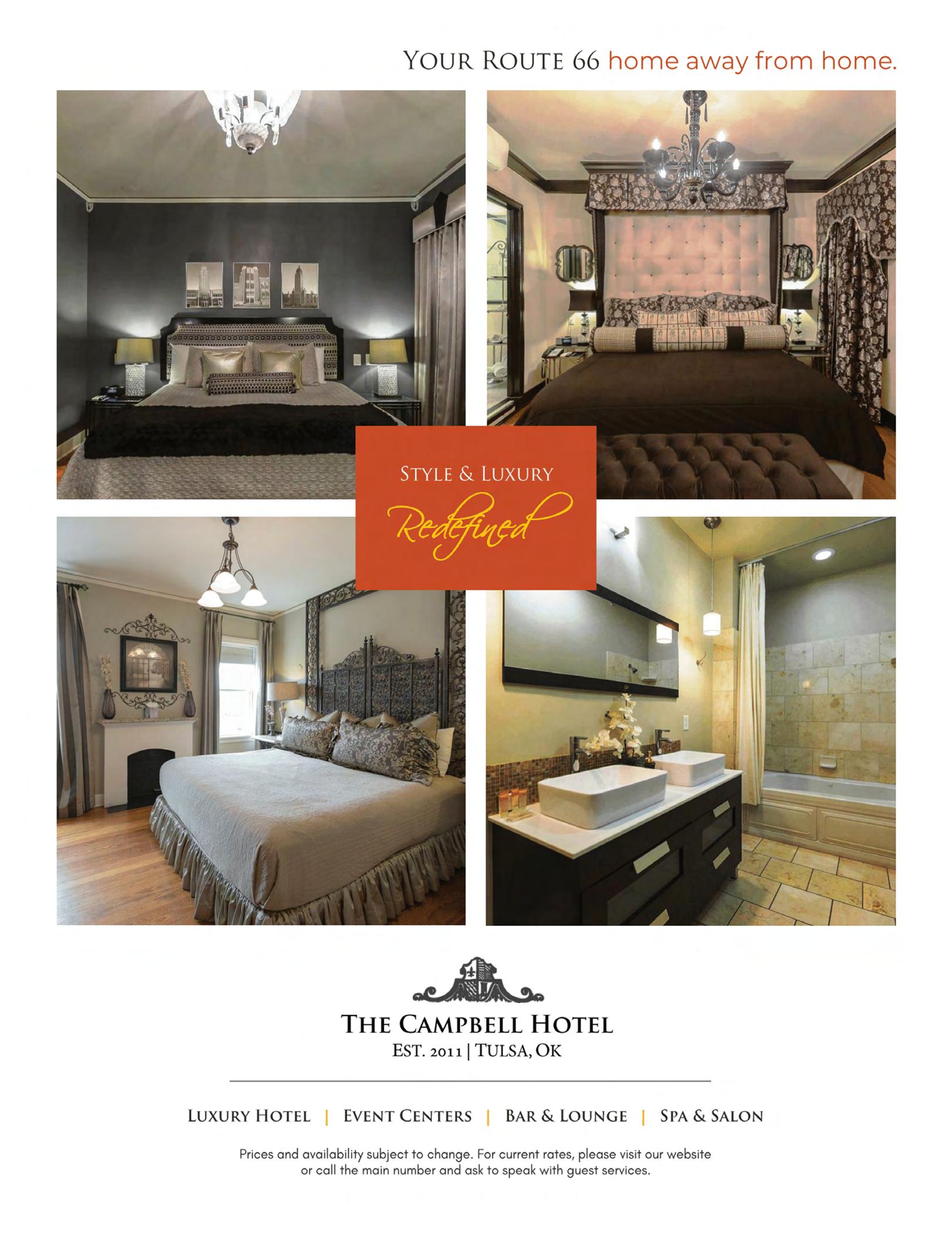

In 2017, Aaron Meek, second-generation member of the Meek family, as well as owner of the luxurious Campbell Hotel and Group M Investment — a real estate firm in Tulsa — reclaimed his family’s legacy by repurchasing their former Meek’s Hardware & Furniture Company building, which is now home to Meadow Gold Mack’s gift shop. He also purchased the office building on the corner. After the closure of The Corner Cafe in 2019, he transformed the property into multiple retail spaces, becoming a key player in the revitalization of 11th Street. Today, these retail spaces house a diverse array of businesses, including the Wildflower Cafe, The Meat and Cheese Show — a specialty grocery store — and Southwestern Trading, which offers Native goods such as pottery and blankets. Above the storefronts are stylish rental lofts, adding to the district’s dynamic appeal.

“Investment in the Meadow Gold District over the last few years has helped elevate all of the businesses in that corridor,” said Rhys Martin, Oklahoma Route 66 Association president. “Once the building on the corner was rehabbed, it drew a lot of interest. The Wildflower Cafe is always busy; the locals love having dining there, and Route 66 travelers want an authentic, locally-owned spot to enjoy a meal before continuing down the road. That big neon sign on the corner, made possible by the City of Tulsa Route 66 Neon Sign Grant, also helps draw a lot of attention!”

For Heather Linville, opening the Wildflower Cafe represented a fulfillment of a lifelong dream. She has always worked in restaurants, starting with her first job at a Simple Simon’s [Pizza] in Eufaula, Oklahoma. “I made hamburgers and pizza, and I don’t know what else,” Linville explained. “Then I got a job at Goldie’s. I think every young waitress of my age probably worked at Goldie’s. Then I moved on to college and continued waitressing. It was flexible for my college schedule. And then I became a wife and mother, and it was easy to just have a couple shifts a week.”

With each restaurant that she worked at, Linville made mental notes: what she liked and disliked; and she dreamed of how she would one day run a place of her own.

Eventually, she landed in Tulsa, where she climbed the ranks to management at a local establishment. Frustrated by the limitations of her role, she began spending her free time exploring vacant buildings, envisioning the perfect space for her vision. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, bringing the restaurant industry to a stand still. Laid off and at a crossroads, Linville saw an opportunity to finally turn her long-held dream into reality.

But first, she needed to settle on a location. She lived in midtown Tulsa at the time and found herself drawn to the atmosphere of an up-and-coming area that was revitalizing as part of the Route 66 renaissance.

“I was very, very interested in the building across the street. It’s called The Wrench. It was a mechanic shop forever and ever; since 1989 is what it says on the sign,” Linville continued. “But it sat empty forever on that corner, and I had this vision of it being a cute little cafe with an outdoor patio. I could never get anyone to communicate with me about it, and it still sits empty five years later. And so, as I was sitting over there [in 2020], I saw some signs in the windows over here and I just thought, ‘Okay, I’m going to call.’”

When she toured the building on 1306 E 11th Street, she saw endless possibilities. As the former home of The Corner Cafe, the space had been in serious need of repairs before its closure. The current owners, Group M Investment, had gutted the interior, leaving it stripped to the studs with no plumbing or electrical systems in place. For Linville, this

presented an opportunity to start fresh and create a space tailored to her personal vision. After signing the lease, she teamed up with contractors to bring her ideal layout to life.

“It was intense. It took a lot of my time and energy, and it just consumed me really. But it was really fun because like I said, that whole year and a half when we were all stuck at home with nothing to do, I was fortunate enough to be shopping in the marketplace or online for different things and just kind of putting the whole vision together in my head; without a lot of pressure because the world was on hold at that time.”

When it came time to name the restaurant, she found herself at a loss. She spent countless hours a day dreaming, letting her imagination wander through endless possibilities. Then, inspiration struck and everything fell into place.

“I’ve always loved wildflowers, and it just seemed like a really cute thing to design the restaurant around, and who doesn’t like flowers? They make everybody happy. And that was kind of my style,” Linville reflected. “One day, my friend Carrie sent me this really nice message about how every time she hears the song from Tom Petty called Wildflowers, she thinks of me, and that was kind of sweet. It was at the same time that we were in the naming process, and it just sounded right.”

Linville collaborated with Encinos 3D Signs in Tulsa to create the striking neon sign now displayed at the street corner. She envisioned a design inspired by Oklahoma’s state wildflower, the Indian Blanket, and Encinos brought this concept to life, working closely with her to finalize the colorful look. With support from a Route 66 Commission grant, half of the sign’s cost was covered, making this vibrant addition possible. In May of 2021, the Wildflower Cafe officially opened for business.

Inside the restaurant, greenery abounds. A potted succulent hangs in every window, and a gallery wall of wildflower prints — a combination of vintage prints Linville has been gifted and items she found antiquing — hangs above the counter. In the back corner, an accent wall with whimsical, colorful wildflowers adds extra flair. Linville carefully considered every detail, down to wildflower-themed light fixtures and string lights that provide extra light, though the sun-drenched space hardly needs it.

Linville focused the menu on simple, fresh and easy items, but it has also evolved over time. At first, Linville only planned to provide lunch, but her staff talked her into adding breakfast as well. The cafe specializes in made-from-scratch items such as biscuits, pancakes, waffles, and cheese grits. Her chef, Chuy Gonzalez, makes a mean huevos rancheros, so that got added as a blue plate special.

“[Gonzalez] has this extra level that he adds with. He just makes everything with love and he doesn’t want anything to go out that doesn’t make him happy or doesn’t satisfy him,” said Linville. “I don’t know how [the kitchen staff] make the eggs so fluffy and delicious. They just sprinkle magic over everything they do.”

For Linville, opening Wildflower Cafe was a chance to do everything her way. She wanted it to be more than a restaurant: she envisioned a community hub and a vehicle for

giving back, both to customers and to the community around them.

“We run it for people, not for ourselves. Obviously we benefit, because we have other people in mind and in our hearts. But when I say that we run it differently, I’m blessed to have the money to keep it going, but it’s not about that. It’s about giving back to as many people as we can, to make their day better just by coming here, or feeling seen or heard or loved. It’s not just a meal. I want people to know that they’re cared about here.”

As Linville and her staff have become invested in the community, Linville has established a Community Impact Fund, which both the restaurant and regular patrons donate to. At one point, the fund helped a local man who was struggling with his day-to-day life to get a motorized wheelchair that makes daily tasks a little more achievable.

“That was a really fun day because he was very, very surprised. I think my happy moments come from when I see other people being affected by what we are doing, and then it makes them want to do it themselves. And so, when I see that happening here, it makes me incredibly happy.”

Today, this storied building, where the cafe now operates, has been reborn as The Meadow Gold Shops & Lofts complex — a blend of retail, dining, and residential spaces — a fresh and vibrant addition to the uber famous Route 66 corridor. After more than a century, new investors and entrepreneurs are breathing life into the historic Meadow Gold District, reviving its charm while honoring its legacy. With each new project, they’re restoring the district’s unique character and sparking fresh energy, creating a destination where the past and present intersect.

The Wildflower Cafe, nestled in the heart of this revitalized area, is now an integral part of the District’s resurgence, a cornerstone in a neighborhood that continues to grow and evolve. It embodies that spirit of renewal and growth, welcoming both locals and travelers to experience a special little slice of history. Tulsa and towns like it are setting the standard about how once depressed communities can be renewed and lead the charge in bringing historical structures and areas back to life. And right at the center of it all is a cozy café that is the answer to one woman’s dream.

By Brennen Matthews

It’s not every day that an actor brings the kind of intensity, vulnerability, and rugged authenticity that Taylor Kitsch delivers on screen. Hugely respected for his breakout role as Tim Riggins in Friday Night Lights , Kitsch has steadily carved out a reputation as one of Hollywood’s most compelling and quietly versatile talents. But before the red carpets and high-profile roles in projects like Lone Survivor, True Detective , and Waco, Kitsch was chasing an entirely different dream — on the ice. Raised in British Columbia, Kitsch had one goal growing up: to play professional hockey. He was a skilled left wing with the drive and discipline to match, playing junior hockey at a competitive level. But that dream was abruptly cut short by a devastating knee injury in his early twenties. For many, such a loss might have marked a dead end. For Kitsch, it was a turning point. After his injury, Kitsch moved to New York, studied acting, and took jobs ranging from personal trainer to homeless couch-surfer while pursuing the craft. His authenticity, born from struggle, not spotlight, shines in every role. It’s the quiet resilience and inner grit that seem to pulse through every performance. Whether he’s playing a tortured Navy SEAL or a charismatic cult leader, Kitsch doesn’t just act, he transforms. Now, Kitsch is back on screen in the highly anticipated second season of The Terminal List: Dark Wolf, reprising his role as Ben Edwards in a story that expands the emotional and physical stakes of the original. In many ways, this is a role that feels like it was written specifically for him. In this candid conversation, Taylor Kitsch opens up about heartbreak, hard lessons, parenting, iconic projects, and how losing one dream led him to discover a bigger one.

Can you take me back to your early years; raised by a single mom, with your two brothers, in a trailer park in British Columbia. That must have been a unique way to grow up.

Yeah, I mean, literally. We moved from Kelowna, BC. I was pretty young, and then we moved into this trailer park… but I think we can all go into the stereotype of a trailer park… the gravel road, trash everywhere, people drinking on a patio, but it was super quaint and when you’re young you really don’t know the difference, right? I didn’t know unless I went to a buddy’s house, who’s got a trampoline or a pool or something. Then you’re like, this is insane. But yeah, every day you’re getting on the bicycle, or you’re playing street hockey… we were right on the verge of this big mountain and lake. I would just go out into the bush, and that’s where creativity lives. We would go and do adventures. We would get into stick wars and build forts and do what kids are supposed to do.

Hockey was a major part of your life for nearly 20 years. Was going pro the dream?

I almost took it too seriously. I definitely wanted to play pro. But you can want it so bad that you’re too hard on yourself, and that was kind of me. It shaped a lot of who I am in regard to work ethic and response to failure. I’m very stubborn. I think that has gotten me a long way, even with my career. I was super green in the beginning, like we all are,

but I don’t come from an acting background, or anything like that. I had no idea you could even do this until I was in my teens. I’m super competitive still, and still play hockey. I live in Montana now, which is basically southern Canada. (Laughs) Other than that our winters are even more harsh than what I remember growing up in Canada.

You famously injured yourself when you were 20, sadly ending your hockey aspirations. Did you gradually move into the realization that you needed a new dream, or did that come quickly? Was it natural to move towards entertainment?

It was gradual. I think you mourn it for a while, and there is no path. You kind of feel like even at 20 or 21, your life is over. That’s just the stakes within yourself, intrinsically. This path that I’ve been on for so long is done. I have no options. I put all my eggs in this basket… and then it was a gradual thing. I always loved storytelling, acting class in high school, and stuff like that. But again, I didn’t think it was a viable option. My personality is kind of all in or nothing. So, once I had decided, I went to New York and I was like, I’ve got to try and see what this is about. I was very cocky. I honestly thought that it was going to be easy, but that certainly wasn’t the case. You kind of get the bug, and you love the challenge. It’s funny, in acting class, being in your early 20s, you see some amazing actors that aren’t working, which is kind of scary. I remember this one actress—she was probably late thirties, and she was incredible, but she just struggled and struggled. And you’re like, damn, if she’s not working, what am I going to be doing? But I think that there’s a commonality between artists. You get that fix of collaboration, risk, and it’s also, you know, self-exploratory stuff. And at that time, obviously, I was pretty stunted emotionally, like most 20-year-old guys are. I had a lot of stuff with my father. But it was such a great tool to have to be forced to explore.

I was tricked into going and seeing a modeling agent in Vancouver. He sent my stuff over to IMG and they were like, “Come to New York.” So I went, not knowing anyone. I traveled with what I thought was a lot of money. I thought, “Oh, this will be good for at least a few months,” and I obviously ran out of money really quickly. I started taking acting classes right when I got to New York.

I get to New York and I’m staying in the models apartment. There were 11 models, maybe more, in a two bedroom. So, what happens is they’re like, “Okay, here’s an apartment, but you’re gonna back pay us. Prorate it.” So, you’re paying $2,000 a month, and I’m sleeping in the walk-in closet, in between the bedrooms. There are bunk beds, but it’s a ranking system when you first get there. If I’m new, I ain’t getting a bed, and models are coming from all over the world. Then there’s some that have been there for months that have no problem paying rent, because they’re working regularly. But then I did my first casting call with Diesel, and I got it. So, I was like, “Wow, this is easy!” but I didn’t

see a nickel. I was like, “Okay, I’ll just get another job,” but another job literally never came. So, the agency sent me to do a test. They offered to pay for it and prorate it too. But by then, I’m starting to owe them more and more, and I’m not working, but hopefully I will get a job. You know, it just builds up. I left that apartment, and I couch surfed and then got a place up in Spanish Harlem, in an apartment with no electricity or no hot water. I didn’t have a social security number to get it. I remember breaking into the basement of this apartment building and trying to get to my meter, or whatever you call it, and fix it so that I could get electricity. I remember, I would go to Gristedes and head over to those big bins of nuts and things, those big orange bins (at the time) in the bulk area. I’d get a transparent plastic bag, fill it, walk around the grocery store, and eat as much as I could and then leave. (Laughs)

So, you were the stereotypical, starving model.

Yeah, involuntarily though! There were hard, f*cking moments, and I hate asking for sh*t from buddies! I had my Canadian VISA credit card and there’s a $500 limit, and obviously I regularly exceeded that. But I would just walk around New York, trying different ATMs. I’d put my code in and hope that I get a hundred bucks. And once in a while… Man, when you would hear that cash spinning out. (Laughs)

After that I worked in Barbados with my dad, digging ditches on a construction site that he was the foreman of. It was like 40-50 days in Barbados, and we worked 6-day weeks, and then I went back to Vancouver. I auditioned for a few things. I think I got maybe one or two roles, but decided to go down to LA. I bought this car, went down to LA, ran out of money, and then subletted a bedroom in an apartment.

Your breakout role as Tim Riggins in Friday Night Lights came in 2006. How did that opportunity come your way?

I was in Vancouver and my Canadian agent and U.S. management team called me, and they’re like, “Hey, there’s a pilot that we want you to audition for, but it’s very late in the game.” They knew Pete Berg personally and they told Pete not to cast the Jason Street role just yet. I read the script, and I was like, “I don’t want to play Jason Street. Can I read for Tim Riggins?” The lack of a father and that kind of stuff hit more home to me, so I put myself on tape—in Vancouver. Then, days later, they’re like, “You need to come down to LA and screen test for Riggins.” It was kind of a whirlwind. I got into this boardroom at Universal. It was NBC Universal and I’m sitting across from this guy. Jesse Plemons is on my right, and I asked him, “Hey, who are you reading for?” And he’s like, “Oh, for Landry,” I’m like, “Okay, good.” And then the guy across me in this boardroom was like, “Who are you reading for?” I’m like, “Oh, Tim Riggins.” And he’s like, “Okay,” and I’m like, “You’re reading for Tim Riggins?” He goes, “Yeah.” So, it was me against this one other guy, and that was it. It was down to me and him, and all these guys, Jesse included, had already done improv with Pete, one-on-one. So, Pete came into the boardroom, and he’s scanning it, and he points to me. We sit in another meeting room, and he’s like, “Man don’t worry about the script. I love to improvise. I love to throw direction out. Are you

okay with that?” And I’m like, “I love it.” So, we just improvised ESPN interviewing Riggins and them asking about my family. Asking about my brother, my dad, alcoholism. And just going into everything Tim Riggins. And then we walked down the hallway, and he looks at me and he’s like, “You’re gonna be just fine, but your Canadian accent has to f*cking go.”

We went into a room and there were like 15 execs sitting there, and a reader to read the scene with me, and Pete was like, “You’re out,” to the reader. “I’m going to take Kitsch. I want to be the reader with him.” So, we get reading and as we are, he just kept interrupting me and screwing up the momentum, on purpose. So finally, as Riggins, I was like, “Are you going to shut the f*ck up and let me finish, or are you going to just keep interrupting me?” And he loved that. So, I finish it. And then it’s awkward, man. You’re just sitting in this room, being judged, and no one says anything. They’re like, “Oh, that was great, thank you for coming all the way from Vancouver.” And I was like, “Is that it?” And they’re like, “Yep.” Then afterwards, I walked into my hotel room that was at Universal Studios or really close to the lot and my hotel room phone was ringing and I picked it up and they’re like, “You’re Tim Riggins.”

That is awesome.

Yeah! I was told at the time that Riggins was kind of on the fringe of the lead characters. He wasn’t gonna have a massive part. But then you know, the rest I guess, is history. It’s like he just took off for some reason. People just gravitated towards Riggins and through the improv and Pete’s process, you were allowed to fail a lot. So that felt organic with Riggins. But it was a great ride.