Fri 13 February 2026 • 20.15

Fri 13 February 2026 • 20.15

conductor Tarmo Peltokoski

violin Simone Lamsma

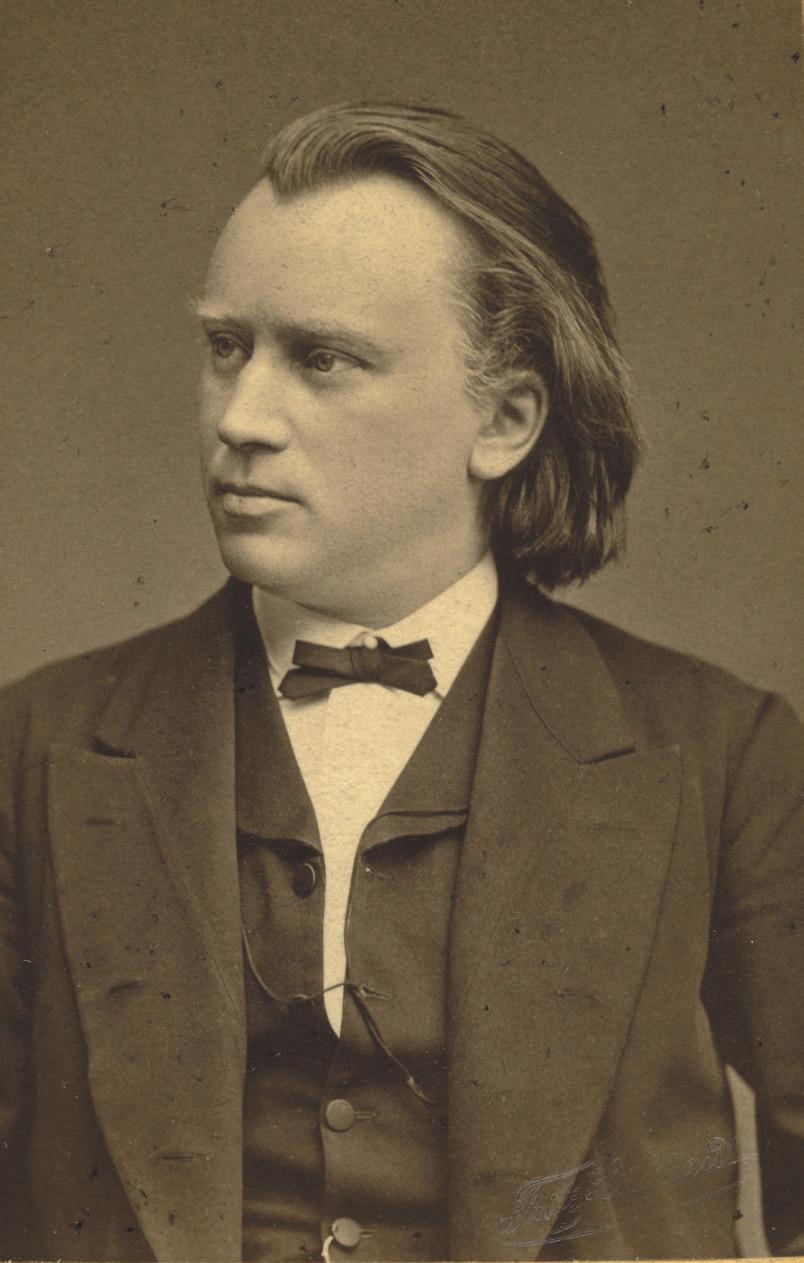

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77 (1878)

• Allegro non troppo

• Adagio

• Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace - Poco più presto intermission

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958)

Symphony No. 3 ‘A Pastoral Symphony’ (1921–22)

Clarinet solo: Julien Hervé

• Molto moderato

• Lento moderato

• Moderato pesante - Presto

• Lento - Moderato maestoso

concert ends at around 22.00

Most recent performances by our orchestra:

Brahms Violin Concerto: Jun 2023, violin Bomsori Kim, conductor Lahav Shani (on tour)

Vaughan Williams Symphony No. 3: first performance by our orchestra

One hour before the start of the concert, Emmeline Mooij will give an introduction (in Dutch) to the programme, admission € 7,50. Tickets are available at the hall, payment by debit card. The introduction is free for Vrienden.

Cover: Photo Luka Tennie (Unsplash)

Ralph Vaughan Williams wearing the Field Ambulance Unit uniform during his training in Saffron Walden, 1915. Coloured photo, coll. Vaughan Williams Charitable Trust

After the first performance of his Violin Concerto, Brahms realised that he had mainly confused the audience. Vaughan Williams had a similar experience at the premiere of his Third Symphony. But then again, he had deliberately misled his listeners.

The seeds for Johannes Brahms’ Violin Concerto were sown in the spring of 1853. The composer was travelling with violinist Eduard Reményi on a joint concert tour through north-eastern Germany. In Hanover, Reményi arranged a meeting with an old college friend, the already world-famous violinist Joseph Joachim. Joachim was impressed by the talent of the then 20-year-old Brahms, and the foundation for a lifelong friendship was laid. Of course, he also asked Brahms for new work, but his patience was severely tested. Not until 1878 did Brahms dare to write a concerto for the violin. The fact that it took so long had everything to do with Brahms’ doubts about his own abilities. His First Piano Concerto from 1857 had received a lukewarm reception and the composer was reluctant

to write another large orchestral work. It was only when he finally completed his First Symphony in 1876 that he found the courage to write a violin concerto for Joachim.

In August 1878, the first sketches were ready. Brahms sent them to Joachim with a request for suggestions and comments. The violinist responded with compliments on Brahms’ original writing for the violin and indeed made a few suggestions, most of which were followed up by the composer. Joachim’s enthusiasm encouraged Brahms, and the premiere was scheduled for New Year’s Day 1879 with the Gewandhaus Orchestra in Leipzig.

The initial reactions to the Violin Concerto were rather tepid – probably mainly because

the listeners had expected more display of virtuosity. They only got that in the finale, which, with its Hungarian gypsy influences, provides musical fireworks. But in the first two movements, the Violin Concerto seemed like a disguised symphony, with the solo violin as the foregrounded partner of the other instruments. When the violinist Pablo de Sarasate was later asked if he would also include Brahms’ new concerto in his repertoire, he shook his head. ‘I will not deny that it is quite good music,’ he is reported to have said, ‘but does anyone think that I am so devoid of taste that I will take my stand on the rostrum, violin in hand, in order to listen to the oboe playing the only melody in the adagio?’ Sarasate was referring to the beginning of the second movement, where the

oboe begins with a truly magnificent melody that is Brahmsian in every respect. Fortunately, Joachim thought differently. Thanks mainly to his tireless efforts, Brahms’ Violin Concerto became so popular that at the beginning of the twentieth century it even surpassed that of Beethoven – Brahms’ great example.

Where Brahms wrote a ‘symphony’ disguised as a violin concerto, shortly after the First World War the Englishman Ralph Vaughan Williams composed a deeply felt lament which he called A Pastoral Symphony. With that title, he raised expectations of an idyllic impression of the countryside, and he had indeed found the initial inspiration for this work among lovely rolling hills. But the circumstances were anything but fairy-tale-like. ‘It is really war time music,’ Vaughan Williams himself said about it in the end. ‘A great deal of it incubated when I used to go up night after night in the ambulance wagon at Écoivres and we went up a steep hill and there was a wonderful Corotlike landscape in the sunset – it’s not really Lambkins frisking at all as most people take for granted.’

An army trumpeter used to practice, and this sound became part of that evening landscape

There is indeed nothing frisky about the notes. The symphony with the misleading title (it was only years after its premiere that Vaughan Williams would call it his Third Symphony) reflects the composer’s experiences as a volunteer with a Field Ambulance Unit during the war years. He was stationed in northern France, some five miles behind the front line,

where he transported wounded soldiers from the trenches to the military hospital. Composing was out of the question under those circumstances, but Vaughan Williams absorbed all his impressions.

When he completed his symphony in 1922, he must have thought of the idyllic landscapes that formed the backdrop to the most terrible images and human tragedies. His symphony is just like that. The first movement seems to begin as a melancholic morning picture of nature. Only the underlying unease tells the discerning listener that there is more going on. This disturbing ambiguity remains present throughout the symphony, which consists of four predominantly slow movements. A good example is the trumpet cadenza in the middle of the second movement, in which a fragment of the Last Post creeps in like a kind of phantom. It is taken from a direct memory of Vaughan

Williams: ‘An army trumpeter used to practice, and this sound became part of that evening landscape and is the genesis of that long trumpet cadenza.’

Also in the third movement, a kind of scherzo, and especially in the finale, Vaughan Williams subtly undermines the conventional idea that a pastoral should be idyllic. That last movement perhaps contains the essence of the symphony. Slow, progressive music with two great clarinet solos that seem to come from another world. This ambiguous lament with which the finale begins seems unable to find solid ground anywhere. When the clarinet solo returns at the end after a violent climax, it sounds lonelier and more distant than ever. As if Vaughan Williams wanted to give a voice to all the senselessly lost lives. But so soon after the war, his audience was not yet ready for that.

Paul Janssen

Farewell

Francis Saunders

This is the last concert week of our violist Francis Saunders. After 28 with the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, he is now retiring.

Born: Vaasa, Finland

Current position: Music Director Orchestre

National du Capitole de Toulouse, Music

Director Designate Hong Kong Philharmonic

Orchestra, Principal Guest Conductor Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, Conductor

Laureate Latvia National Symphony Orchestra

Education: piano at Kuula College (Vaasa) and the Sibelius Academy (Helsinki), conducting with Jorma Panula, Sakari Oramo, Hannu Lintu and Jukka-Pekka Saraste

Breakthrough: 2022: positions in Bremen, Riga, Rotterdam, and Toulouse

Subsequently: debuts with Hong Kong Philharmonic, Toronto Symphony Orchestra, RSO Berlin, Konzerthaus Orchester Berlin, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, SWR Symphonieorchester, Göteborgs Symfoniker, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Los Angeles Philharmonic

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2022

Born: Leeuwarden, the Netherlands

Education: Yehudi Menuhin School with Hu Kun; Royal Academy of Music in London with Maurice Hasson

Awards: International Violin Competition of Indianapolis (2006), Benjamin Britten International Violin Competition (2004); Oskar Back Violin Competition (2003)

Solo debut: as fourteen-year-old with the Northern Netherlands Orchestra in Paganini’s Violin Concerto

Soloist with: London Symphony Orchestra, Academy of St Martin in the Fields, Vienna Symphony, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic Premieres: Violin Concertos by De Roo, Van der Aa and Wantenaar, Lost Landscapes by Rautavaara Instrument: ‘Aurora ex-Foulis’-Stradivarius from 1703

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2009

Sun 1 March 2026 • 14.15

conductor and piano Lahav Shani

Dukas The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

Shostakovich Suite for Variety Orchestra

Shostakovich Piano Concerto No. 2

Strauss Till Eulenspiegel

Thu 12 March 2026 • 20.15

Fri 13 March 2026 • 20.15

Sun 15 March 2026 • 14.15

conductor Santtu-Matias Rouvali cello Senja Rummukainen

Rimski-Korsakov Capriccio espagnol

Elgar Cello Concerto

Shostakovich Symphony No. 6

Desplat Conducts his Film Music

Fri 20 March 2026 • 20.15

Sat 21 March 2026 • 20.15

conductor Alexandre Desplat

Desplat Music from Godzilla, The King’s Speech, The Shape of Water and other films

Thu 2 April 2026 • 19.30

Fri 3 April 2026 • 19.30

Sat 4 April 2026 • 19.30

conductor Leonardo García Alarcón

soprano Sophie Junker

alto Wiebke Lehmkuhl tenor (Evangelist) Moritz Kallenberg tenor (Arias) Mark Milhofer

bas (Vox Christi and Arias) Andreas Wolf

chorus Laurens Collegium, Nationaal Jongenskoor

Bach St. Matthew Passion

Proms: The Four Seasons Recomposed

Fri 10 April 2026 • 20.30

violin/leader William Hagen

Richter The Four Seasons

Chief Conductor

Lahav Shani

Honorary Conductor

Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Principal Guest Conductor

Tarmo Peltokoski

First Violin

Marieke Blankestijn, Concert Master

Vlad Stanculeasa, Concert Master

Quirine Scheffers

Hed Yaron Meyerson

Saskia Otto

Arno Bons

Rachel Browne

Maria Dingjan

Marie-José Schrijner

Noëmi Bodden

Petra Visser

Sophia Torrenga

Hadewijch Hofland

Annerien Stuker

Alexandra van Beveren

Marie Duquesnoy

Second Violin

Charlotte Potgieter

Frank de Groot

Laurens van Vliet

Elina Staphorsius

Jun Yi Dou

Bob Bruyn

Eefje Habraken

Maija Reinikainen

Babette van den Berg

Melanie Broers

Tobias Staub

Sarah Decamps

Robin Veldman

Viola

Anne Huser

Roman Spitzer

Galahad Samson

José Moura Nunes

Kerstin Bonk

Janine Baller

Francis Saunders

Veronika Lénártová

Rosalinde Kluck

León van den Berg

Olfje van der Klein

Jan Navarro

Cello

Emanuele Silvestri

Gustaw Bafeltowski

Joanna Pachucka

Daniel Petrovitsch

Mario Rio

Eelco Beinema

Carla Schrijner

Pepijn Meeuws

Yi-Ting Fang

Killian White

Paul Stavridis

Double Bass

Matthew Midgley

Ying Lai Green

Jonathan Focquaert

Arjen Leendertz

Ricardo Neto

Javier Clemen Martínez

Marta Fossas Mallorqui

Mario Fernández

Flute

Juliette Hurel

Joséphine Olech

Manon Gayet

Flute/Piccolo

Beatriz Baião

Oboe

Karel Schoofs

Anja van der Maten

Oboe/Cor Anglais

Ron Tijhuis

Clarinet

Julien Hervé

Bruno Bonansea

Alberto Sánchez García

Clarinet/

Bass Clarinet

Romke-Jan Wijmenga

Bassoon

Pieter Nuytten

Lola Descours

Marianne Prommel

Horn

David Fernández Alonso

Felipe Freitas

Wendy Leliveld

Richard Speetjens

Laurens Otto

Pierre Buizer

Trumpet

Alex Elia

Adrián Martínez

Simon Wierenga

Giovanni Giardinella

Trombone

Pierre Volders

Alexander Verbeek

Remko de Jager

Bass trombone

Rommert Groenhof

Tuba

Martijn van Rijswijk

Timpani/ Percussion

Danny van de Wal

Ronald Ent

Martijn Boom

Jesús Iberti Rubira

Harp

Albane Baron