Focus - Full Spectrum Rotary Wing Seapower The Giant Leap for Mine Countermeasures: Integrating the Navy’s MCM Forces By LT Joshua A. Price, HSCWSL

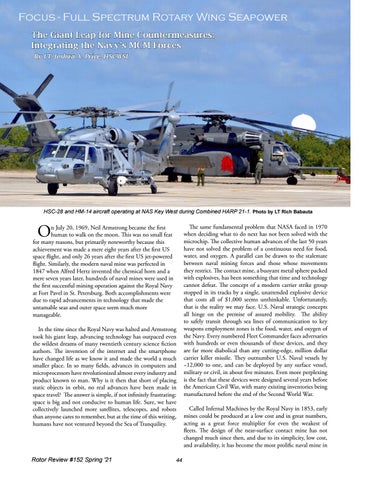

HSC-28 and HM-14 aircraft operating at NAS Key West during Combined HARP 21-1. Photo by LT Rich Babauta

O

n July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong became the first human to walk on the moon. This was no small feat for many reasons, but primarily noteworthy because this achievement was made a mere eight years after the first US space flight, and only 26 years after the first US jet-powered flight. Similarly, the modern naval mine was perfected in 1847 when Alfred Hertz invented the chemical horn and a mere seven years later, hundreds of naval mines were used in the first successful mining operation against the Royal Navy at Fort Pavel in St. Petersburg. Both accomplishments were due to rapid advancements in technology that made the untamable seas and outer space seem much more manageable. In the time since the Royal Navy was halted and Armstrong took his giant leap, advancing technology has outpaced even the wildest dreams of many twentieth century science fiction authors. The invention of the internet and the smartphone have changed life as we know it and made the world a much smaller place. In so many fields, advances in computers and microprocessors have revolutionized almost every industry and product known to man. Why is it then that short of placing static objects in orbit, no real advances have been made in space travel? The answer is simple, if not infinitely frustrating: space is big and not conducive to human life. Sure, we have collectively launched more satellites, telescopes, and robots than anyone cares to remember, but at the time of this writing, humans have not ventured beyond the Sea of Tranquility.

Rotor Review #152 Spring '21

44

The same fundamental problem that NASA faced in 1970 when deciding what to do next has not been solved with the microchip. The collective human advances of the last 50 years have not solved the problem of a continuous need for food, water, and oxygen. A parallel can be drawn to the stalemate between naval mining forces and those whose movements they restrict. The contact mine, a buoyant metal sphere packed with explosives, has been something that time and technology cannot defeat. The concept of a modern carrier strike group stopped in its tracks by a single, unattended explosive device that costs all of $1,000 seems unthinkable. Unfortunately, that is the reality we may face. U.S. Naval strategic concepts all hinge on the premise of assured mobility. The ability to safely transit through sea lines of communication to key weapons employment zones is the food, water, and oxygen of the Navy. Every numbered Fleet Commander faces adversaries with hundreds or even thousands of these devices, and they are far more diabolical than any cutting-edge, million dollar carrier killer missile. They outnumber U.S. Naval vessels by ~12,000 to one, and can be deployed by any surface vessel, military or civil, in about five minutes. Even more perplexing is the fact that these devices were designed several years before the American Civil War, with many existing inventories being manufactured before the end of the Second World War. Called Infernal Machines by the Royal Navy in 1853, early mines could be produced at a low cost and in great numbers, acting as a great force multiplier for even the weakest of fleets. The design of the near-surface contact mine has not changed much since then, and due to its simplicity, low cost, and availability, it has become the most prolific naval mine in