Fall 2023 Number 162

So Others May Live

Also in this Issue:

Be All In - By RDML Amy Bauernschmidt, USN VRM’s Accelerated Growth - By CAPT Justin McCaffree, USN, VRM Commodore Happenstance: The Inspirational Journey of CAPT Sunita Williams, USN Managing The Hazards: Extreme Cold Weather Helicopter Detachment Operations Preparing the Navy for the Indo-Pacific: Advancing UAS for the Great Power Competition

FOCUS: So Others May Live So Swimmers May Be Paid...........................................................................................................28 By AWRCM Justin “Cali Condor” Phillips, USN Persian Gulf Rescue.......................................................................................................................29 By AW3 William "Beaver" Schuetzeberg, USN (Ret.) Flexibility is a Capability................................................................................................................30 By LT Joey Curtis, USN How Civilian SAR Missions Help Train Units for the Worst................................................32 By LT Jack Nilson, USN Ready or Not...................................................................................................................................34 By LT Anna “LiMP” Halverson, USN

Fall 2023 ISSUE 162

Clementine Two - U.S. Navy Night Rescue Over North Vietnam......................................35 By CDR LeRoy Cook, USN (Ret.) (HC-7 Det 104) Revised by LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.)

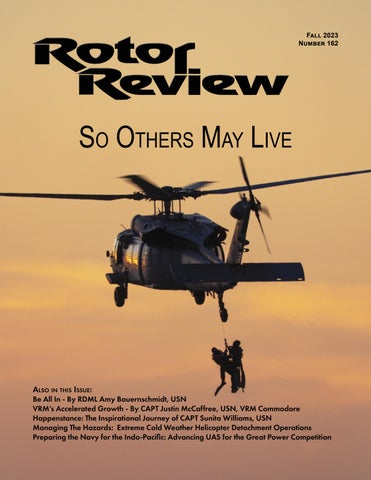

Exercise Tarpon Springs, A Warfighting Skills Exercise..........................................................42 About the Cover HSC-9 Tridents conducting SAR training Created by Aicrewmen for Aircrewmen. in the Willoughby Spit. AWS2 Brewington By AWSCS Matthew Estep, USN, CHSCWL and AWS2 Harter demonstrating direct deployment recover y procedures . Tarpon Springs................................................................................................................................45 Photographer: AWS2 Philip Johnson (@ By AWS2 Natalie Campbell, USN philip.james.studio) Rotor Review (ISSN: 1085-9683) is published quarterly by the Naval Helicopter Association, Inc. (NHA), a California nonprofit 501(c)(6) corporation. NHA is located in Building 654, Rogers Road, NASNI, San Diego, CA 92135. Views expressed in Rotor Review are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies of NHA or United States Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard. Rotor Review is printed in the USA. Periodical rate postage is paid at San Diego, CA. Subscription to Rotor Review is included in the NHA or corporate membership fee. A current corporation annual report, prepared in accordance with Section 8321 of the California Corporation Code, is available on the NHA Website at www. navalhelicopterassn.org.

NAS Key West SAR: Optimizing Long Range Maritime Search and Rescue .............................46 for the Future Fight By AWSC Joshua Teague, USN and AWS2 Brett Medford, USN More of Naval Aviation Needs to Prioritize Range.................................................................48 By CDR Matt Wright, USN So Others May Live..........................................................................................................................50 By HM1 Stephanie Higgins, USN

FEATURES Happenstance: The Inspirational Journey of CAPT Sunita Williams, USN..............................52 By LT Elsiha "Grudge" Clark, USN Start Them Young: ........................................................................................................................56 An Account from the Aircrew Library Volunteers of San Diego County By LT Jared “Dogbeers” Jackson, USN

Managing The Hazards: Extreme Cold Weather.....................................................................58 POSTMASTER: Send address changes Helicopter Detachment Operations to Naval Helicopter Association, P.O. Box By LT Patrick “The HOFF” Fonda, USN 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578. Preparing the Navy for the Indo-Pacific: .....................................................................................62 Rotor Review supports the goals of Advancing UAS for the Great Power Competition the association, provides a forum for By Carl Forsling and Chris Misner discussion and exchange of information on topics of interest to the Rotary Force and keeps membership informed of NHA A Case for Auditory Learning Resources in Naval Aviation Training....................................64 activities. As necessary, the President of By LT Andrew George, USN NHA will provide guidance to the Rotor Review Editorial Board to ensure Rotor Flight Of Four Lands On Arthur Ashe Stadium Court.................................................................66 Review content continues to support By CAPT Joellen Drag-Oslund, USNR (Ret.) this statement of policy as the Naval Helicopter Association adjusts to the A Bridge for Intra-Theater Distributed Fleet Operations: The CMV-22B.........................68 expanding and evolving Rotary Wing and By Robbin Laird Tilt Rotor Communities. ©2023 Naval Helicopter Association, Inc., all rights reserved Rotor Review #162 Fall '23 2

COLUMNS Chairman’s Brief.........................................................................................................................6 National President's Message.................................................................................................7 Executive Director's View.........................................................................................................8 Vice President of Membership Report.................................................................................10 From the Editor-in-Chief........................................................................................................12 On Leadership..........................................................................................................................14 Be All In By RDML Amy Bauernschmidt, USN Commodore's Corner............................................................................................................16 VRM's Accelerated Growth By CAPT Justin McCaffree, USN,VRM Commodore

Editorial Staff EDITOR-IN-CHIEF LT Annie "Frizzle" Cutchen, USN annie.cutchen@gmail.com ASSISTANT EDITOR-IN-CHIEF LT Quinn "Charity" Stanley, USN qrstanley@gmail.com MANAGING EDITOR Allyson "Clown" Darroch rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org COPY EDITORS CAPT John "Assassin" Driver, USN (Ret.) jjdriver51@gmail.com CDR John Ball, USN (Ret.) helopapa71@gmail.com

Scholarship Fund Update.......................................................................................................18

LT Elisha "Grudge" Clark, USN elishasuziclark@gmail.com

Historical Society.....................................................................................................................22

AIRCREW EDITOR AWR1 Ronald "Scrappy" Pierpoint, USN pierpoint.ronald@gmail.com

Editor Spotlight.........................................................................................................................24 View from the Labs.................................................................................................................26 By CAPT George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.)

DEPARTMENTS

Industry and Technology..........................................................................................................70 Elbit America to Supply Integrated Avionics Processors for V-22 Collins Opens Power Lab for Hybrid, Electric Tech Landing Collective Real Estate Solutions: Founded with a Purpose, Serving with Passion Bristow Secures Early Delivery Positions for Five Elroy Air Chaparral Aircraft Metro Aviation, a SkillBridge Partner Changes of Command..............................................................................................................76 Squadron Updates....................................................................................................................78 VX-1 Turns 80 - Celebrating 80 years of Pioneer Pride HT-18: 50 Years of Women Flying in Naval Aviation HSC-23: Talofa Lava, Samoa, from Det X HSM-49 Pilots Attend Marine Corps MAWTS Off Duty......................................................................................................................................84 Book Review: Unforgotten in the Gulf of Tonkin, by Eileen A. Bjorkan Reviewed by LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.) Engaging Rotors.......................................................................................................................86 Signal Charlie............................................................................................................................90 Previous Rotor Review Editors Wayne Jensen - John Ball - John Driver - Sean Laughlin - Andy Quiett Mike Curtis - Susan Fink - Bill Chase - Tracey Keefe - Maureen Palmerino Bryan Buljat - Gabe Soltero - Todd Vorenkamp - Steve Bury - Clay Shane Kristin Ohleger - Scott Lippincott - Allison Fletcher - Ash Preston - Emily Lapp Mallory Decker - Caleb Levee - Shane Brenner - Shelby Gillis - Michael Short

3

COMMUNITY EDITORS HSC LT Tyler "Benji" Benner, USN tbenner92@gmail.com LT Andrew "Gonzo" Gregory, USN andrew.l.gregory92@gmail.com HSM LT Joshua "Hotdog" Holsey, USN josholc@gmail.com LT Abby "Abuela" Bohlin, USN akguerra023@gmail.com LT Thomas "Buffer" Marryott Jr, USN tmarryott@gmail.com LT Nathan "MAM" Beatty, USN nathan.g.beatty@gmail.com LT Jared "Dogbeers" Jackson, USN jared.d.jack@gmail.com LT Samantha "Amber" Hein, USN lsamhein@gmail.com USMC EDITORS Maj. Nolan "Lean Bean" Vihlen, USMC nolan.vihlen@gmail.com Capt. Michael "Chowdah" Ayala, USMC michael.ayala@usmc.mil USCG EDITOR LT Marco Tinari, USCG marco.m.tinari@uscg.mil TECHNICAL ADVISOR LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.) chipplug@hotmail.com

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Thank You to Our Corporate Members - Your Support Keeps Our Rotors Turning To get the latest information from our Corporate Members, just click on their logos:

Platinum Supporters

Gold Supporters

Executive Supporters

Small Business Partners

Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

4

Naval Helicopter Association, Inc. P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578 - (619) 435-7139 www.navalhelicopterassn.org Regional Officers

National Officers

Region 1 - San Diego Directors ......................................CAPT Chris Richard, USN CAPT Will Eastham, USN CAPT Justin McCaffree, USN CAPT Nathan Rodenbarger, USN President ..................................CDR Scott Lippincott, USN

President.......................................CAPT Tommy Butts, USN Vice President..........................................CDR Eli Owre, USN Executive Director................CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.) Business Development...............................Ms. Linda Vydra Managing Editor, Rotor Review.........Ms. Allyson Darroch Retired Affairs....................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.) Legal Advisor...........................CDR Chris Cooke, USN (Ret.) VP Corp. Membership...........CAPT Tres Dehay, USN (Ret.) VP Awards.................................CDR Philip Pretzinger, USN VP Membership........................LT Brendan McGinnis, USN VP Symposium 2024....................CAPT Tommy Butts, USN Secretary....................................................LT Lena Reid, USN Special Projects........................................................VACANT NHA Branding and Gear............................LT Sam Kim, USN Senior HSM Advisor..............AWRCM Nathan Hickey, USN Senior HSC Advisor..................AWSCM Shane Gibbs, USN Senior VRM Advisor.................AWSCM Tom Kershaw, USN

Region 2 - Washington, D.C. Director .....................................................................VACANT President ...........................................CDR Tony Perez, USN Co-President.................................CDR Pat Jeck, USN (Ret.) Region 3 - Jacksonville Director.....................................CAPT John Anderson, USN President............................................CDR Dave Bigay, USN Region 4 - Norfolk Director...................,........................CAPT Ed Johnson, USN President .........................................CDR Matt Wright, USN

Directors at Large

Chairman...............................RADM Dan Fillion, USN (Ret.)* CAPT Gene Ager, USN (Ret.)* CAPT Chuck Deitchman, USN (Ret.)* CAPT Dennis DuBard, USN (Ret.)* CAPT Tony Dzielski, USN (Ret.)* CAPT Greg Hoffman, USN (Ret.)* CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.)* CAPT Mario Mifsud, USN (Ret.)* CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.)* CAPT Matt Schnappauf, USN (Ret.)* LT Zoe MacFarlane, USN* AWRCM Nathan Hickey, USN* * Also serving as Scholarship Fund Board Members

Junior Officers Council

Nat’l Pres....................... LT Zoe "Latrina" Macfarlane, USN Region 1........................LT Ryan "Shaggy" Rodriguez, USN Region 2 ......................................LT Rob "JORTS" Platt, USN Region 3...............LT Harrison "Dusty Bottoms" Pyle, USN Region 4..................................LT Rochelle "PG" Balun, USN Region 5................................LT Chris "BOTOX" Stuller, USN Region 6....................................LT Robert "DB" Macko, USN

Region 5 - Pensacola Director ........................................CAPT Kenneth Kerr, USN President ......................................CDR Keith Johnson, USN '23 Fleet Fly-In Coordinator...............LT Chris Stuller, USN Region 6 - OCONUS Director ..........................................CAPT Mike O'Neill, USN President ..............................CDR Matthew E. Chang, USN

NHA Historical Society (NHAHS)

President............................CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.) VP/Webmaster..................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.) Secretary................................LCDR Brian Miller, USN (Ret.) Treasurer...........................CDR Chris Fitzgerald, USN (Ret.) S.D. Air & Space Museum.....CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.)

NHAHS Committee Members

NHA Scholarship Fund

President ..............................CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.) Executive VP/ VP Ops ...CAPT Todd Vandegrift, USN (Ret.) VP Plans.................................................CAPT Jon Kline, USN VP Scholarships ...............................Ms. Nancy Ruttenberg VP Finance ....................................CDR Greg Knutson, USN Treasurer.........................................................Ms. Jen Swasey Webmaster.........................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.) Social Media ..............................................................VACANT CFC/Special Projects ................................................VACANT . Navy Helicopter Association Founders CAPT A.E. Monahan, USN (Ret.) CAPT Mark R. Starr, USN (Ret.) CAPT A.F. Emig, USN (Ret.) Mr. H. Nachlin

CDR H.F. McLinden, USN (Ret.) CDR W. Straight, USN (Ret.) CDR P.W. Nicholas, USN (Ret.) 5

CAPT Dennis DuBard, USN (Ret.) CAPT Mike Reber, USN (Ret.) CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.) CAPT Jim O’Brien, USN (Ret.) CAPT Curtis Shaub, USN (Ret.) CAPT Mike O’Connor, USN (Ret.) CDR John Ball, USN (Ret.) CDR Chris Fitzgerald, USN (Ret.) LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.) AWRCM Dave Crossan, USN (Ret.)

CDR D.J. Hayes, USN (Ret.) CAPT C.B. Smiley, USN (Ret.) CAPT J.M. Purtell, USN (Ret.) CDR H.V. Pepper, USN (Ret.)

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Chairman’s Brief Rescue at Altitude

By RADM Dan "Dano" Fillion, USN (Ret.)

W

e were in the seventh month of our six-month deployment to the Persian Gulf exiting “Fenway” (back in the day) for a 0330 recovery and shutdown. We had completed a double bag and were looking forward to some chow. It was a typical dark night, as they all are without much moon. I was the Det MO and the H2P was the Training O. The H2P had performed superbly both on the ground and especially in the air. He shot an “on the numbers” approach with the AWs backing us up; life was good. As we got in close to the deck, I made a “closure” call which my H2P acknowledged. At that point he smoothly raised the nose of the aircraft to decelerate. However, as we crossed the deck edge, the stabilator kicked off. Immediately. I acknowledged the Master Caution Warning Light, to which the H2P concurred, and I took my eyes off the hangar face to re-engage the stabilator. As I returned to look outside the cockpit, I heard the AW call “stop forward, steady hover.” I now saw the HRS, (Horizon Reference System) Bar through the chin bubble and I yelled “I HAVE THE CONTROLS WAVING OFF TO PORT!” The H2P did not acknowledge my two commands but the aircraft was now moving sideways away from the ship accelerating with a 35 degree left wing down attitude. Several more calls for "I have the controls” did not get executed. I was pulling on the cyclic and collective with all I had, but I was giving up a foot of height and probably 75 pounds to the H2P who was no stranger to the weight room. Using ”non standard” terminology in the cockpit finally resulted in him letting go of the controls. Immediately the aircraft went from 35 degrees left wing down and accelerating to 40 degrees right wing down, accelerating, and climbing at a rocket's pace. Doing my best usual attitude recovery procedures (i.e., trying to find the “ball”), I heard the most calm strong voice on the VOX that I had heard in the last several seconds; “Attitude gyro, MO.” The call came from the senior aircrewmen that night and his command resulted in me getting my “shiitake mushroom” back together. I did the next approach and landing to a shutdown. We learned a lot that night. I may very well be the only pilot who was rescued by an aircrewmen at altitude! The women and men who serve their country as aircrew/rescue swimmers are a very special breed of Sailors! NHA recognizes that no rotary-wing TMS can fly safely and effectively without the warriors in the back and we sure can’t fight the aircraft without our aircewmen! Aircrewmen/ Rescue Swimmer’s Wings are GOLD for a reason! NHA is working hard to support the Rescue Swimmer Badge Initiative and continues to support all the families that support our aircrewmen. NHA exists to provide camaraderie, mentorship, and advocacy for all things Rotary-Wing. NHA needs you as a member of your organization! Consider it! Join. This is your tribe! Non-standard brief item on every NATOPS Brief I did, from that day on after having a bad night behind the boat emphasizes “Remember studs: one splash all splash.” VR & CNJI (Committed not just Involved), Dano

Read Rotor Review on your Mobile Device Did you know that you can take your copy of Rotor Review anywhere you want to go? Read it on your kindle, nook, tablet or on your phone. Rotor Review is right there when you want it. Go to your App Store. Search for Naval Helicopter Association Events. If you already have the NHA App you will need to refresh the App. On the home screen, hit the Rotor Review button. It will take you to Issuu, our digital platform host. There you can read the current magazine. Scroll down to "Articles." This option is formatted for your phone. You can also view, download or print the two page spread. You also have access to all previous issues by searching on Google for Rotor Review or browsing through Issuu's website. If you have Issuu's App for mobile reading, please be aware that they discontinued it.

Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

6

National President's Message Train So Others May Live

By CAPT Tommy "Smokey" Butts, USN

G

reetings from NHA here in San Diego!

I’ve assumed the controls from CDR Emily “ABE” Stellpflug. Before I get started, I’d like to take a moment to thank ABE for her loyal dedication and service to the rotary community. In my short time in the seat, I have quickly realized the time and effort that she dedicated to advancing our professional organization. ABE, thank you for everything that you’ve done to promote NHA and the favorable position you have left us in, well done. As I’ve engaged rotors and pushed my Nr up to 100% here at NHA, I’m impressed by the NHA Staff, here in San Diego, led by CAPT Jim “Super G” Gillcrist, USN (Ret.) and the volunteers around the world. The staff and volunteers who continue to move the chains for NHA are comprised of civilians, active duty enlisted Sailors, officers, and retired legends who paved the path for us. I believe that it is our duty to further grow our professional organization. As I write this, we are inside of a month from the Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-in (GCFFI) in Pensacola. The purpose of the GCFFI is to promote the sea services’ rotary community in an interactive environment. CNATRA Instructors and Fleet Aircrews exchange ideas, expertise and career information with Student Naval Aviators and Student Aircrewmen. In tying into this edition of Rotor Review, a key takeaway I have from the purpose of GCFFI is the interaction with Student Aircrewmen. For a vast majority of the students who will live by the mantra “So Others May Live” for the rest of their lives, GCFFI is the first time that they will see, touch, and smell a Fleet aircraft. Here at HSC-3, the HSCWP FRS, every month I have the opportunity to speak at the Fleet Replacement Aircrewman (FRAC) Graduation. It’s the capstone ceremony where our brothers and sisters in the back of the aircraft receive their “Wings of Gold.” During my speech, I typically throw in a sea story while trying to impart some knowledge. Most recently, the sea story I shared was based on my first rescue. It was a small fishing vessel with two personnel onboard that had no power and was taking on water. Without me giving a blow by blow, you all know that the weather was terrible, it was the middle of the night, my co-pilot and I were unbelievably flawless on the controls, and everything went as planned…..okay okay, but it was a really dark zero illumination night 35nm off the coast of Guam. The thing I remember most about that night was the debrief discussion with our swimmer. He talked about initially being panicked when he had to disconnect from the hoist. It was the first time that he had ever been in the open ocean at night by himself, there was a sinking fishing boat nearby, waves crashing over his head, and rotor wash beating him down. At that moment, full of adrenaline he made his way to the survivors. Fast forward 20 minutes and two survivors along with our swimmer were in the aircraft as we safely made our way back to shore. When I asked him how he overcame the panic and focused on the task, he said, “I thought about my training and I knew there was a helicopter overhead to pick us up.” I’ll never forget the proud smile on his face and my personal feeling that I was working with the absolute best our country has to offer. Brave, hard-working and professional, So Others May Live! When you have an opportunity, take a look at the CNO SARMM News at the following link: https://intelshare.intelink.gov/sites/sarmm/HSC3SARMM@navy.mil. The Fall 2023 Edition details a recent rescue of 11 personnel off of a vessel in distress by HSC-25. It is an honor to serve as your National President of our professional organization! V/r, Smokey NHA LTM #504

7

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Executive Director’s View NHA is NOT just about Pilots … By CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.)

T

he focus of this issue is on our Aircrew Brothers and Sisters who are integral to every mission we fly no matter what the platform – rotary wing, unmanned, or tilt rotor. And their motto of … “So Others May Live” … is both noble and a compelling call to action for mission execution within the entire Rotary Force. Acknowledgement that we are indeed a talented team of aircrewmen, maintainers, and pilots is what makes the Rotary Force, and NHA as a professional organization, unique. During my last flying tour at the World Famous HSL-43 BattleCats, the squadron slogan was: “Fix … Fly … Strike!” I liked the slogan. It was compelling without any need for embellishment. It represented what we did as a high functioning team of maintainers, aircrewmen, and pilots. The mission could only be accomplished if we knew how to fix the airframe, fly the airframe, and fight the airframe. We deployed and operated as one team. Similarly, NHA is a team and a brotherhood with a similar, defining motto: “Every member counts / stronger together.” We are a unique professional organization. We are comprised of maintainers, aircrewmen, and pilots who remain connected, who help one another, who continue to offer mentorship to one another, and who pay it forward. Every member counts and makes the organization stronger. To repeat something that I shared in an earlier column, the best kept secret in this vibrant, professional organization is its members. The NHA Staff has the immense privilege every day of working alongside high caliber folks from National Leadership to Junior Officer and Aircrew Reps across the entire Rotary Force – coast to coast. In closing, we remain a relationship organization. Meaning that the relationships we make at the squadron and aboard ship on deployment are lifelong, enriching, and purposeful. These same relationships continue downstream and remain powerful throughout our military careers, as well as when we transition to our next adventure outside of the service. We look after one another and pay it forward continuously. This is why we are members of our professional organization. This is why you should join and / or renew your membership. Please keep your membership profile up to date (mailing address and region affiliation). If you should need any assistance at all, give us a call at (619) 4357139 and we will be happy to help – you will get Linda, Mike, Allyson, or myself. Warm regards with high hopes, Jim Gillcrist.

NHA's Newest Lifetime Member (LTM) #485, Vice President for Membership, LT Brendan McGinnis, USN, HSC-23 Wildcards is presented his coin by CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.), NHA's Executive Director.

Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

8

Lifetime Member (LTM) in the Spotlight LT Andrew “Mr. T” George, USN Lifetime Member #685 HSC-23 Wildcards "Mr. T" is a Reno, Nevada native who graduated from the University of Nevada, Reno where he earned two Bachelor of Science Degrees in Finance and Economics in 2013. He commissioned through Officer Candidate School in 2014 and was designated a Student Naval Aviator. His training began in Pensacola, FL for Aviation Preflight Indoctrination, then on to the VT-6 “Shooters” in Milton, FL where he learned to fly the T-6B. He selected rotary wing and continued to the HT-28 “Hellions” for advanced flight training where he learned to fly the TH-57 and was designated a Naval Aviator in 2016. He selected to fly the MH-60S in San Diego and completed training at the Fleet Replacement Squadron, HSC-3 “Merlins.” During his first sea tour with the HSC-23 “Wildcards,” he flew the MH-60S and MQ-8B while deployed with Det 8 on USS Gabrielle Giffords (LCS 10 / “Blue Team”) conducting Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) in the South China Sea in 2020. Selected for his extensive Fire Scout operational experience, he completed a shore tour with HSCWP VTUAV Maintenance Detachment as Assistant OIC at NAS Point Mugu flying the MQ-8B and MQ-8C. Next, LT George reported to HSC-23 again and is now serving as Det 6 MQ-8 Ops / Pilot back aboard LCS 10.

“Mr. T” conducting a Fam 0 of his 2022 Mercedes Benz Airstream Interstate 24GT Class B RV (otherwise known as a Tactical JO Sprinter Van) with NHA Executive Director.

Every Member Counts / Stronger Together

9

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

VP of membership Report BradChad's Membership State of the Union By LT Brendan McGinnis USN

I

n my new role as VP of Membership, I'm excited to introduce myself and outline my vision for the future of NHA and our community's engagement. I’m a former and current HSC-23 Wildcard, currently serving as a Single Type/Model/Series MQ-8C Fire Scout Super JO. Between these two Wildcard tours, I served as an HT-28 Hellion Instructor, contributing to the training of our future Navy, Marine, and Coast Guard Aviators. As a dedicated and recently recognized Lifetime Member of NHA, I've witnessed firsthand the challenges and sometimes overlooked contributions of Junior Officers within our organization. Attending the NHA Symposium provides a unique opportunity to connect and make unconventional contributions to the Navy. It's the only rotarydriven event where an Ensign can ask the Air Boss how we can initiate changes at a deck plate level to improve the lives of our Sailors and commands. Not only is this type of interaction welcomed at these events, but it's actively encouraged. Future goals as the NHA Membership VP are as follows: 1. JO Roll Call (No not just JOs): We are committed to enhancing accountability among our current members. This starts with a thorough review of squadron rosters by our NHA Representatives. The aim is to foster better communication among leadership and representatives. I’m working closely with the JO President, LT Zoe “Latrina” Macfarlane, to ensure that the average JO NHA Representative can reach out effectively, whether they're at the bottom or the top of the chain, with a single message on our mobile devices via Groupme or text messages, not just work emails. What would help us the most would be if everyone could take the time to update their membership profiles with current personal information, squadron affiliation, and region to help us get you validated in our system. The website information is listed below in my contact information. 2. Participation (and the ability to do so) directly correlates to Membership: Membership directly influences participation and the opportunities available to our members. We are emphasizing the importance of the Navy Air Logistics Office (NALO) reliability for our unfunded travelers and ensuring that all traveling parties can make the most of the Symposium, making it more than just a whirlwind 48-hour experience. "Max Beep" is already in motion, with efforts underway to give HSC-21 a run for their money! 3. Early Engagement of Aviators: A critical focus for us is to involve aviators early in their career journeys. For instance, at NAS Whiting, where we're producing approximately 15-20 aviators every two weeks across three squadrons, there's a significant gap in their knowledge about NHA. We plan to engage NAS Whiting NHA Representatives more actively in this process, helping them understand the value NHA offers and the benefits it can provide as they advance in their naval careers. We're also keen to introduce them to the unbeatable "Nugget" Membership offer and facilitate a smooth handoff to FRS NHA Reps at their next command. Thank you all for your continuous commitment to our organization and please reach out if you have any questions or concerns. Fly Navy, LT Brendan “BradChad” McGinnis VP of NHA Membership LTM #485 (724) 809-6548 Brendan.s.mcginnis@gmail.com www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

10

So Others May Live - Skill and Confidence By LT Zoe "Latrina" Macfarlane,USN

B

efore I tell an important story that I believe exemplifies the theme of this Rotor Review edition, I wanted to introduce myself. I am LT Zoe “Latrina” Macfarlane, and I have turned over with LT Alden “CaSPR” Marton as the NHA JO President. I am currently an instructor at HSC-3 and feel honored and privileged to be part of this organization. I look forward to continuing the work and connections that NHA fosters. The purpose of this edition is to highlight the work of our Aircrewmen. While I could tell countless stories that illustrate their proficiency, professionalism, and dedication to the mission, one story stands out from the rest. During deployment, on my first tour with HSC-4, we were attached to CVN-70 and operating in Seventh Fleet when an F-35C in our airwing crashed on the flight deck. Our OPS Team scrambled to find two crews to fill a section that would be departing on an emergency MEDEVAC. Due to time constraints, AWS1 Charles Weaver, the Crew Chief in the section lead aircraft, took charge of navigating the section safely to an island no one had been to before. He recounted that night to me, and it is clear that his skill was instrumental in the safety and success of the mission. On January 22, 2022, AWS1 Weaver was called to the Ready Room where he quickly learned the news of the crash on the flight deck. HSC-4 was preparing to launch an MH-60S section to MEDEVAC the casualties to an airfield 300 miles away. At the time, the number of patients and severity of their injuries were unknown. Although the squadron was skilled in 6-hour mission planning to execute any mission quickly and effectively, the crews were told they’d have only 20 minutes until they had to hotseat. Further complicating matters, they would be flying at night under zero percent illumination to an airfield on an island to which no one had been before. When the Commanding Officer and MEDEVAC section lead, CDR Thomas “Brother” Murray, asked AWS1 Weaver: “How do you feel about the FST tablet?,” AWS1 Weaver said he had a feeling that the section would be navigating with the only information they had: lat/long coordinates. When I asked AWS1 Weaver what stuck out the most about that night, he replied: “There was no time to do any mission planning. We didn't have any details on who we were taking and what kind of care they would need enroute. At that moment, with adrenaline pumping, I just tried to stay calm and let my training take over. I knew we could do the mission, no problem, and they did. The crews walked to the flight deck. AWS1 Weaver recalls, “It was complete chaos. Everyone was hustling to get gear we believed we would need for the patients.” After about 30 minutes, the three patients were loaded in both aircraft, and the section launched. In the cabin with AWS1 Weaver was HM1 Walters, the squadron corpsman, and AWS3 Zavala. When the patient was loaded into AWS1 Weaver's cabin, HM1 Walters recognized another difficulty facing the crew. The patient had a serious skull injury which would prevent the section from transiting at a high altitude. Bad news for fuel, time, and any communication with externals. After take off, AWS1 Weaver looked at the FST tablet, and the coordinates to which they were flying. He then began to figure out how the section would navigate there without climbing to altitude. He recounts, “I was zooming in and out looking at the terrain and altitude, trying to figure what the safest way to get to the island and the airfield would be. I built a route on the FST tablet, and passed all the coordinates to CDR Murray. He passed the flight plan to the dash two aircraft on our inter-flight frequency.” Due to the length of their flight and fuel on board, CDR Murray asked if the section could fly at a higher altitude to get to the airfield faster and more efficiently. AWS1 Weaver was ready with an answer. Based upon the terrain, low light, and the patient's injury, he recommended that they remain feet wet and clear of land for as long as possible. The section landed at Manilla Ninoy International Airport after transiting over 200 miles from the carrier, and safely transferred the three patients to an ambulance. All three patients survived and received the care they needed. The section ended up reversing their initial route to return to CVN 70. The skill and confidence AWS1 Weaver demonstrated on this mission led to the safe transfer of all three MEDEVAC patients. His expertise, assertiveness, and skill aided the section in safely executing the mission and saving the lives of three Sailors. 11

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

From the Editor-in-Chief So Others May Live

By LT Annie "Frizzle" Cutchen, USN , f you have chatted with me about Rotor Review, you have probably witnessed me on my soap box about Aircrew involvement with NHA. One of my main goals during my tenure as Editor-in-Chief, (EIC) of this publication has been to get our Aircrew involved and excited to be here. We were able to get the NHA Team all in on dedicating this issue to unsung heroes of rotary wing aviation—United States Naval Aircrewmen. On my first tour and into my instructor tour I preach that I have learned as much from the Aircrewmen I have had the pleasure of working alongside as I have from my fellow Pilots. I'm sure many of us share more than one experience where these men and women saved the day.

I

My hope with this issue is that you, Aircrewmen from all platforms, feel inspired and heard seeing art and reading articles by your peers. Furthermore, I hope this inspires you to continue to write for Rotor Review, submit your photographs, and engage with Naval Helicopter Association. I am so excited for readership to dig in and read articles from AWRCM Philips, AWSCS Estep, AWS2 Campbell, and the list goes on. I’d like to give a special shout out to Philip Johnson, a prior MH-60S Aircrewman and the artist behind the lens for the cover photo. I encourage you to explore more of his work at Philip James Studio—he is truly remarkable. Photo contestants, look out! I am sad to announce that this will be my last issue as EIC of Rotor Review. This opportunity has brought so much more engagement and positivity in my life than I ever could have imagined. It has been an absolute pleasure and honor to work with so many of you to create a magazine worth reading. A very special shoutout to CAPT G for all of the mentorship, encouragement, providing me the room to maneuver, and trust you have put in me to get the job done. Another huge shoutout to Allyson “Clown” Darroch for putting up with me balancing the magazine with my flying job and always being open to my constant requests for changes. It has truly been an honor working alongside you both and the rest of the NHA Team. Rotor Review is being passed down to excellent hands. LT Elisha “Grudge” Clark brings so much dang passion for Rotor Review and a very creative lens. She is the brain behind the crossword addition to the magazine and a woman who knows how to get it done. LT Quinn "Charity" Stanley, taking over as assistant Editor-In-Chief," is truly just an incredibly likable guy. Not only that, but everything he touches, he makes better. He brings a passion for helicopter aviation and shares Grudge’s ability to make things happen. Thank you, readership, most of all for making all of the work that goes into the magazine worthwhile.

A New EIC Takes the Helm By LT Elisha "Grudge" Clark, USN

H

ello from sunny San Diego! My name is LT Elisha “Grudge” Clark, and I’m happy to introduce myself as your new Editor-in-Chief. A big thank you to LT Annie “Frizzle” Cutchen, who has faithfully served you in that capacity through four (going on five) captivating and impactful issues. There is nothing more human than a story. In a community spread far and wide across the world, it is crucial to tell the stories capturing the life and times of our rotary-wing and tilt-rotor brothers and sisters. That is why I am so grateful to have this platform to lean on, and so many voices with a story to share. This issue in particular represents the crew concept we helicopter pilots live and breathe. These pages include recent stories of heroics, along with stories from our past that are fully worth remembering. Inside you’ll find tales of one-wheel landings, rescues in the mountains, and fallen and recovered canyoneers by today’s best of the best in Search and Rescue. CDR LeRoy Cook’s story of the “Clementine Two” rescue may seem far off, but as he describes watching a forgettable movie in the wardroom and trotting groggily off to bed right before the call to action, I bet you can picture yourself there, too. Building our sense of community is something I am passionate about, and we do that by giving everyone a seat at the table. It would be difficult to fly without pilots and aircrew, this is true. However, it would be next to impossible to meet our mission without steady hands turning wrenches. Our next issue, “Fly, Fix, Fight,” will be focused on our tireless maintenance personnel. We want to hear your stories, your successes, your gripes, and your lessons. Consider this a call to action - do not let your story go untold. Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

12

Letters to the Editors It is always great to hear from our membership! We need your input to ensure that Rotor Review keeps you informed, connected, and entertained. We maintain many open channels to contact the magazine staff for feedback, suggestions, praise, complaints, or publishing corrections. Please advise us if you do not wish to have your input published in the magazine. Your anonymity will be respected. Post comments on the NHA Facebook Page or send an email to the Editor-in-Chief. Her email is elishasuziclark@gmail.com, or to the Managing Editor at rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org. You can use snail mail too. Rotor Review’s mailing address is: Letters to the Editor, c/o Naval Helicopter Association, Inc., P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578.

Articles and news items are welcomed from NHA’s general membership and corporate associates. Articles should be of general interest to the readership and geared toward current Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard affairs, technical advances in the rotary wing / tilt rotor industry, or of historical interest. Humorous articles are encouraged.

Rotor Review and Website Submission Guidelines • • • • • • • • •

Articles: MS Word documents for text. Do not embed your images within the document. Send as a separate attachment. Photos and Vector Images: Should be as high a resolution as possible and sent as a separate file from the article. Please include a suggested caption that has the following information: date, names, ranks or titles, location and credit the photographer or source of your image. Videos: Must be in a mp4, mov, wmv or avi format. With your submission, please include the title and caption of all media, photographer’s name, command and the length of the video. Verify the media does not display any classified information. Ensure all maneuvers comply with NATOPS procedures. All submissions shall be tasteful and in keeping with good order and discipline. All submissions should portray the Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard and individual units in a positive light.

All submissions can be sent via email to your community editor, their emails are on page 3, the Editor-in-Chief (elishasuziclark@gmail.com), or the Managing Editor at the NHA office (rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org). You can also use the USPS mail. Our mailing address is: Naval Helicopter Association P.O. Box 180578 Coronado, CA 92178-0578

13

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

On Leadership Be All In

By RDML Amy "B12" Bauernschmidt, USN

USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72) maneuvers through a turn while underway in the U.S. 5th Fleet Area of Responsibility. U.S. Navy photo by CAPT Lee Apsley, USN

S

moke was engulfing the passageways on the second deck near the aft mess decks. Five minutes later, smoke was reported filling the O3 level. This was not a drill. Fire spreads rapidly onboard ships quickly consuming spaces and options. Sailors rushed to their gear, DCA mobilized the response and XO and CHENG guided efforts at the scene while I coordinated external communication. The response was automatic. It had to be – we were being tested on all our training. That morning I was on the bridge discussing the underway and missions in front of us with the team. Over the 1MC, the first call of smoke near the aft mess scullery was made, then came the second call of smoke. XO and I both ordered GQ to be called away almost simultaneously. My heart sank, besides thinking about USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72) Sailors, the question entered my mind - would we face a similar situation as USS George Washington (CVN 77) did in 2008? Never pass up an opportunity to get better. What we do matters. Our hard work makes the difference, mobilizing to complete the mission against the enemy, whatever or whomever the enemy may be. On this day, our adversary was a fire, but tomorrow it could be another country. Whether we serve on ships, in squadrons, turn wrenches, man consoles in combat, stand lookout, do the laundry, or support vital functions in other ways, we are all warriors. As warriors, we

Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

must own our part of the mission, seizing ways to have the maximum impact each day in those moments where training, initiative, and courage make the difference. One of my favorite quotes is from JJ Watt. It goes something like this: “Success isn’t owned - it’s leased and rent is due everyday." Every single day. Someone is coming for your greatness, and if you’re not constantly improving your game, just know someone else is improving theirs.” On game day, if and when we need to head into the fight, you are only as good as the daily training opportunities you methodically and meticulously capitalized on and used to your advantage. Every single day. We have to do the work, owning what we do each day forges how we will operate when it matters. In Lincoln’s case it was damage control, but equally important are daily communication checks, brushing up on NATOPS, practicing search and rescue, or methodically rehearsing and refining tactics to be ready for the day we face a different enemy. In seizing training opportunities, we aid ourselves and our teammates in accomplishing the mission more effectively. However, reflect on a time when we didn’t own our training, when we didn’t take advantage of an opportunity presented to make ourselves, our crew, our squadron and our Navy better. What is the impact of missed opportunities? We can’t afford to waste them. We all have countless examples of someone who owned the mission, we also know within ourselves, the 14

day we didn’t put forth the effort we could have to complete an extra event or challenge ourselves in the air or in the simulator. On the bridge, it seemed like a lifetime had passed. The XO updated me as he donned an SCBA and headed through the smoke to the fire. I was exceedingly confident my XO, CHENG, DCA, ADCA and 1,300 Sailors part of the Damage Control Training Team and Lockers were where they needed to be, doing what they needed to do. I knew the XO, Training Officer, and Fire Marshall had meticulously prepared the ship for this day. We did not repeat drill packages or drills. We did not drill in the same location with the same casualties. I knew from the previous 16 months monitoring everything this team worked so hard to achieve, my job was to stay out of their way, keep the big picture, guide the bridge and combat team, and coordinate with my Strike Group Commander, and higher echelon chain of command for the required support. Because of our amazing Sailors, we contained the fire within 20 minutes, then spent hours de-smoking from frames 60-200 and the 03 level down through the second deck. The NCIS and NAVSEA fire experts arrived within 24 hours to assess and inspect the scene. People rise to the environment they are in - what environment and opportunities are you creating to own the mission and forge the team into the warfighting organization required to execute the mission? The good leader will take the opportunities and the mission and translate and transform it into tangible daily actions ensuring, when needed, everyone is ready and able to perform at their best. Our job developing warfighting competencies must be a part of what we do each

day because each day, each flight hour, each event matters. Owning the mission, whatever it may be, methodically executing every detail allows the larger warfighting effort to fall into place. Today, we operate in a consequential environment during a consequential time. As tensions rise around the globe, it is important to remember we are the backbone of our national defense. The challenges we face are complex and we must prepare daily to confront a determined adversary. What we do each day matters and our hard work makes the difference, don’t miss opportunities. We are not always given ramp up time to get to the needed level of performance, we need to be performing at a high level daily. To this day, my Chief Engineer credits the fact the fire only damaged one space (approx 5x8ft) to the fact we called away GQ immediately, alerting everyone to a developing situation, and a group of Sailors swiftly taking action to combat a fire which, we estimate, reached temperatures in the area over 2000 degrees Fahrenheit. As combat crews have proven again and again throughout our Navy’s history, all the training and dividends from drill repetition created the muscle memory and kicked in driving the team's response demonstrating great skill and tremendous courage. The Chiefs and Officers made sure the crew’s valiant efforts had the maximum effect, starting with the prompt alarm and their immediate mobilization. Never pass up an opportunity to get better - what we do matters and our hard work makes a difference!

Sailors raise a rigid-hull inflatable boat during a man-overboard drill aboard Nimitzclass aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72). U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Joel A. Mundo

15

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Commodore's Corner VRM's Accelerated Growth

By CAPT Justin McCaffree, USN, VRM Commodore

VRM-50 CQ Photo by AM2 Anthony Gomez, USN (VRM-50)

T

he request to write this issue’s Commodore’s Corner came at an ideal time because the VRM Community has seen significant change in the last year, but also because the theme of Rotor Review #162 touches on a mission area that is part of a much larger discussion on how to employ the CMV-22B Osprey in the future. Accelerated growth has been the experience for VRM this year and that will continue into 2024. VRM-30 is preparing to send out the next wave of detachments, after completing the first ever CMV-22B deployments in 2022. Additionally, officers and enlisted came together to identify a targeted investment that could be made in order to reduce detachment required airlift support by 50%. This effort will have positive impacts over the entire life of the VRM Community and also save the NAE millions. VRM-40 has gone from a squadron in name to receiving aircraft to earning the safe to operate certification in a span of months. VRM-40’s final challenge for 2023 will be the homeport shift from NAS North Island to NS Norfolk. Once established, the squadron will serve as the operational east coast VRM squadron.

VMMT-204 multi-service FRS which trains USN, USMC, and USAF V-22 pilots and aircrew. Until VRM-50 started to train students, NATSG and VMMT-204 were the first contact between USN personnel and the V-22 Osprey. In many ways, NATSG is the cradle for Navy V-22 operations which is borne out by the fact that the vast majority of current CMV-22B fliers received their initial training in New River. Any officer, chief petty officer, or Sailor who served at NATSG was instrumental to all current and future success of the VRM Community. While the previous paragraphs provide an update on where VRM is, the topic of where VRM is going is as interesting as it is complex. Much like a Navy MH-60 helicopter, many senior leaders see a V-22 and assume that each version is interchangeable regardless of the mission. The CMV-22B is optimized for combat logistics but the Osprey in general is a very flexible and capable aircraft. A year ago, ADM Paparo told VRM to “blow up the COD CONOPS,” which is an effort that the VRM leadership is spending significant time exploring.

The FRS, VRM-50, completed the first CAT I students and the squadron is poised to become the single source for trained pilots and aircrewmen in the coming months. Together with VRM-30, VRM-50 is eagerly anticipating moving into a brand new, purpose built hangar toward the end of the year.

The point behind ADM Paparo’s statement is that the CMV will be asked to do missions in 7th Fleet that were not possible using the C-2A. Although a stalwart much loved COD platform, the C-2A is bounded by a legacy logistics model that uses a long airfield runway to fly to the CVN and back. The CMV has few airfield restrictions and can service many other classes of ships than the CVN.

2024 will be a little bittersweet for the community as the Naval Aviation Training Support Group (NATSG), MCAS New River, has started the sundown process which will culminate in September next year. NATSG is part of the

Another area of exploration in blowing up the CONOPS is in the search and rescue arena, which is the theme of this issue of Rotor Review. The CMV-22B has several advantages for the SAR mission when examining a potential conflict in

Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

16

VRM-50 in El Centro. Photo by ADC Keil Diaz, USN (VRM-50)

7th Fleet. The aircraft has a 1150 nm range, the ability to conduct in-flight refueling, a 240 KCAS cruise speed, and 48 rescue hoists on contract. However, VRM aircrewmen are not rescue swimmers so the recovery of survivors from the water would be a significant challenge. While there are many COAs to achieve more SAR capability inside VRM, they each have differing financial costs and time to train hurdles. The first solution to increasing SAR capability inside VRM is the most expensive and time consuming, and that is qualify AWFs as rescue swimmers. This would be a permanent fix but without a validated requirement to do so, would be unlikely to get funded. A simpler solution could be to qualify a small number of HSC rescue swimmers to fly on the CMV to serve in an as needed capacity. Another option could be to utilize the CMV-22B as a patient transport vehicle to get the injured to a higher level of care. The CMV-22B's speed, range, large cabin space, the capability to carry up to 12 litter patients, and the ability to land/take-off like a helicopter make it uniquely suited to move patients within the Pacific AOR.

Regardless of where the CMV fits into the SAR mission, it is up to the entire vertical lift community to think through survivor recovery, stabilization, and transport to arrive at the appropriate level of care in a Great Power Competition environment. Long gone are the days of the standard SAR scenario being a single or dual seat jet ejection in close proximity to the carrier. New scenarios should include how to recover a survivor at beyond 200 nm or how to conduct rescues for a mass casualty event like a sinking DDG. Should a fight happen in 7th Fleet, every platform that has the ability to conduct SAR will be needed to do their part. While it is exciting to reflect on all the accomplishments that the VRM Community has achieved this year, it is just as exhilarating to contemplate where VRM will go in the future. Although VRM’s primary mission remains COD and combat logistics, it is clear that the community and the aircraft will be called upon to do more in the Pacific, including identifying its contribution to the mission that is best summed up by, “So Others May Live.” Special thanks to AWSCM Robert Kershaw for his insight and collaboration on this article.

VRM-30 participating in EABO in Hawaii, April,2023. Photo by LT Don Gahres, USN (VRM-30) 17

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Naval Helicopter Association Scholarship Fund Grease Doesn't Lie Life in the Mail Room of Naval Aviation By CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.), President NHASF NHA LTM #4 / RW#13762

L

ast year, I embarked on a mission to swim 100 miles and win a commemorative tee shirt or watch cap. Four to five times a week, I braved the elements to swim my daily mile, and then take satisfaction in capturing my mileage on a plexiglass status board, containing name, daily distance covered, and gross total. Name Ragman, J. S.

Daily Yards 1600 2000

etc etc etc 750

Total 109.75

But working the grease board at the pool brought back forgotten memories of life in the Mail Room of Naval Aviation. Adding up the swim board took me back to my first job out of flight school at HM12...I was assigned as the Logs and Records Officer for a 95-pilot squadron. I was responsible for manually logging yellow sheet flight info to logbooks and maintaining the flight info on a large grease board. The scheduler used my info to prepare the daily flight schedule and truthfully, there are only five or so top JO jobs in a squadron, so speed of posting the past-day yellow sheets and accuracy were key components in the daily routine. HM-12 in 1976 was a place where: • CNO’s mission capable rate was 35% and we struggled to meet that standard. • We had no call signs yet; we had 95 pilots, and 35-40 of them were named Dave. As a new guy, if you wanted to hail a fellow officer, you’d call out “Hey Dave” and have a good chance of connecting. • Ops (schedules and logs and records) became the quasi-ready room after the wardroom closed at 0800. Pilots got on the flight schedule by being seen at the scheduler’s desk, as verified by your strip on the grease board, and take care if the entry was late or worse, inaccurate. Now the grease board contained all the information you’d need to schedule flights, mission and fam/instrument type training, night flights, instrument hops, check rides, cross counties (RONs and ROLs) much of it based on the numbers of an accurate grease board. One entry though was the block for quals –the board’s legend showed various coded quals: A (AMCM Mission Commander), B (HAC), C (Copilot), and D (Pilot under Instruction). We did not have an H-53 RAG until 1978. There were other codes for functional quals including: FCP, NATOPS/Asst NATOPS and Instrument Check Instructor. One morning, preceding the end of the fiscal year when instructor pilots were scrambling to use up our quarterly fuel allowance, one of the surlier "Senior LTs" of the squadron entered the Ops Office. He told the schedules writer to put him on for a trainer as his monthly flight time was low. As he scanned the board, he looked at his strip and added the numbers and then looked at the quals sheet – he had quals as a Mission Commander, FCF Pilot, Asst NATOPS and Standardization and then he noted that his quals had been erased and replaced by one letter. The letter “J.” He scrolled eyes down to the legend and read the notation: J = A**H***. Bingo, in an instant, J-Codes were born and earning a “J-Qual” or becoming “J” Qualified, from some egregious faux pas was not a good thing. At best, J-qualified became an unofficial censure quickly taken up by a group of LTJGs known as the Gang of Four. That's a story for another time. "Lesson Learned. I once asked a JO to lay out the most important JO jobs in the squadron. ”Skeds… no, ACFT Division… no, QA… no, First LT… no, Legal… no.” The most important job in the squadron is your job…make it so!" Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

18

Na

on

pter Ass elico oci at lH i va

NHASF

Sc

h ol

a r s h i p Fu n

d

Apply and Donate!

Shipmates, greetings from the Scholarship Fund. We are in our 31st year…founded in 1993, over five hundred scholarships and over $500,000 have been awarded to eligible active-duty officer and enlisted personnel, and their family members - spouses, children, and grandchildren. Annually, a minimum of fifteen scholarships are awarded. The number is set in the Bylaws by the Board of Directors, usually from a pool of 60-75 eligible applicants. My goal coming to the NHA Scholarship Fund back in 2020 was to set conditions for NHASF sustained growth. Together, the NHASF Committee wrote a vision statement and added a mission statement to guide a five-year plan: Vision: Provide a sound, growing fund base to incrementally increase the dollar value of the fifteen annual awards total to reach $75k ($5,000 each) in 5 years (2025) and for our members, be a premier scholarship choice in Naval Aviation in 5 years (2025) Mission Statement: To award college scholarships to eligible members of the Naval Helicopter Community and their families (USN, USMC, and USCG) to pursue their educational goals. Quite simply, to increase the amount of each scholarship to $5,000 and then sustain that growth. Our report card through 2022 see Table (1) below.

2024 Application Season We opened online applications on 1 September and set our deadline - all required documentation must be received by the January 31st deadline. As we write this, we are in the middle of our 2024 application process with about 20 eligible applications receive. Historically, the low number of applicants early on is not “good" or "bad” because applications arrive in earnest after the first semester ends (November- December, once transcripts are available). We reckon 2024 will be a big year as we follow our 5-year strategic plan and ratcheted up our scholarship value to $4,500 for each of the 15 scholarship awardees. For guidance, check out the Scholarship Fund website at https://www.nhascholarshipfund.org. 2024 Fundraising Goal: $100,000 target for operating, scholarships, investment growth, IT costs, and admin.

To APPLY or DONATE, go to our website: https://www.nhascholarshipfund.org

19

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

In May 2023, we awarded 17 $4,000 Scholarships. This year, we intend to award a minimum of fifteen $4,500 scholarships. Additional numbers and levels of scholarships may be awarded annually depending on fundraising success. On the other hand, donations are coming in slowly. With "Giving Tuesday" rapidly approaching (28 November), I encourage you to make a generous contribution to the Scholarship Fund, whether an individual, memorial or investment gift. See our donation options at https://www.nhascholarshipfund.org. As you reflect on donating, please consider giving to our General Memorial Fund or establishing a new memorial or legacy fund (ex., NHASF General Memorial Fund, the HS-5 Night Dipper Memorial Fund, or the H-53/Big Iron Fund) to preserve the legacy of our communities and remember the heroes who make up our proud rotary wing heritage. And finally, before the year draws to a close, I want to remind you of a smart way to give to NHA. Those who are 72 ½ years of age or older can take advantage of a special approach to make a gift that has tax benefits. This popular gift option is called many things, from “IRA Rollover,” “Tax-Free Distribution,” or “QCD,” but know that it is a simple, tax-wise way to make a difference. Contact your IRA Fund Administrator (Vanguard, Fidelity, Ameriprise, etc.) for more information. A gift to the NHA Scholarship Fund is tax deductible. The NHA Scholarship Fund is a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit charitable California corporation: TAX ID # 33-0513766. I look forward to your support in the 2023-24 scholarship rounds and at the next NHA National Symposium in May 2024 at Harrah’s Resort, Southern California. FROM NHASF OPS MANUAL: SECTION 2.1.02 ELIGIBILITY: https://www.nhascholarshipfund.org/prescreening/ (A)

THE APPLICANT AND/OR SPONSOR MUST BE: A new NHA lifetime member, living or deceased, (on or after 15 Feb 2020) or a member in good standing for a minimum of three years by January 31st of the year applying for a scholarship. or A TRACOM or first tour active-duty O-1/O-2, who is a 2 Year "Nugget" Member of NHA, and his / her family are exempt from the three-year eligibility requirement, or Active duty Enlisted (E-6 and below), with a current or past helicopter affiliation (stationed in a helicopter). or MV-22 squadron, or other helicopter aviation unit) and their family members, are exempt from the NHA membership requirement. A letter from his/her command is required confirming the Sponsor/Applicant is currently serving, or has previously served, in a USN, USMC, or USCG helicopter or MV-22 squadron or other helicopter aviation unit.

(B)

THE APPLICANT MUST BE: Active-Duty or Reserve Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard Rotary Wing Aviator, Aircrewman, or Maintenance/Support Personnel or Prior Active Duty / Reserve Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard Rotary Wing Aviator, Aircrewman, or Maintenance/Support Personnel or The natural/step/adopted child, grandchild, or spouse of an Active Duty / Reserve / prior / retired; Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard rotary Wing Aviator, Aircrewman, or Maintenance/ Support Personnel

(C)

The applicant must be a high school graduate or prospective high school graduate; high school equivalent graduate; or current college undergraduate / graduate student

(D)

The applicant must be pursuing a trade certificate, associate degree, bachelor’s degree, or graduate degree from an accredited institution.

(E)

Service Academy: Applicants who have received an appointment to a Service Academy are not eligible to receive an NHA Scholarship.

Applications may be completed online beginning 1 September 2023 and must be completed with all required documents submitted by 31 January 2024. NHA Membership information is available by logging into the NHA website, www. navalhelicopterassn.org and viewing their profile.

Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

20

21

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Naval Helicopter Association Historical Society SH-60F Update By CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.), President, NHAHS LTM#46 / RW#16213

T

here is a lot to catch you up on as follows:

• Happy 80th Birthday to United States Naval Helicopter Aviation! • Our Official Helicopter Birthday is 16 October 1943. • Thank you to our Chief Selects for washing the Flag Circle Aircraft on Saturday September, 9. • The aircraft look presentable again and thank you to all who supported this effort.

• We had a Charity Golf Tournament on Thursday, November 9th, to support the Scholarship Fund and Historical Society. For those who attended, thank you for your support. By all accounts it was a great way to start the Veterans’ Day long weekend. Lassen SH-60F Medal of Honor Memorial Update Check on the Pictorial Project Progress made on the aircraft restoration at the link below. (https://sh60fhoas.navalhelicopterassociation.org/sh-60-foxtrot-progress/). I encourage you to watch the Lassen Video about Clyde’s Rescue and Life HERE. (https://sh60fhoas.navalhelicopterassociation.org/lassen-moh-history-video/). • The paint job on the fuselage has been completed. • The paint job on the tail was completed on October 25, 2023. • There has been an engineering redesign requirement for the mounting plate and associated connecting hardware. • The redesign has delayed the Dedication Ceremony and put it on hold for what was an event planned for Friday, January 19, 2024. PMA 299 is involved now and assisting with providing a workable solution. • We are estimating a minimum of a 45-day delay. The new Dedication Ceremony date is TBD. • Brick donations continue IVO of the engineering delay. • Pay tribute to a friend, family member, or yourself. Additionally, remember a fallen shipmate or crew/individual lost at sea. • We continue to collect donations to reach our goal and could use your $upport. • If you have already donated, thank you very much! • If you have yet to donate, please consider making a contribution. • We have had 360 donations and are halfway to our goal of $250K. You can donate online at https://sh60fhoas.navalhelicopterassociation.org/make-a-donation-today, or you can mail a check or drop off a payment at the NHA Office. For those of you who attended and participated in the Fleet Fly-In, sounds like you had a great time in Pensacola. Keep your turns up. Regards, Bill Personius Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

22

Computer Rendition of NASNI Stockdale Entrance with SH-60F on a Pedestal

Mail Checks to: Naval Helicopter Association Historical Society, Inc. (NHAHS) (Preferred) NASNI SH-60F Project PO Box 180578 Coronado, CA 92178-0578 Or Donate Online: https://sh60fhoas.navalhelicopterassociation.org/ 23

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

Spotlight Editor AWR1 Ronald Pierpoint, USN Enjoy a Q&A with one of our Editors, AWR1 Ronald Pierpoint! • Editor Since: October 2022 • Location: San Diego, California • Past Squadrons/Commands: HSM-41 & HSM- 77 • Favorite Tour: HSM-77, in 2019 Combat Element "Tactical Tanukis" • Favorite EP: Unusual Attitude Recovery • Favorite Color: Green • Favorite Food: Pizza • Favorite Hobby: Spending time with my wife, Sarah, and our three dogs Hakuba, Yuzu, and Lala

Why did you decide to become a Rotor Review Editor? Great question! A mentor approached me to see if I would be interested in being an editor for Rotor Review and at the moment I didn't give it any thought and just answered with, "Yeah, of course!" I'm glad I joined the team because not only did it allow me to meet some amazing people in the military and civilian sectors, but I also am able to be part of a community that is passionate about discussing and expressing topics of interest for our rotary brothers and sisters.

What is your favorite memory in Naval Aviation? That's a hard question to answer! There are a ton of amazing memories that come to mind. If I had to choose one, I'd have to choose my last flight at HSM-77. I was lucky enough to fly with one of my best friends in the cabin and also with two amazing pilots and leaders in the cockpit. There's a saying in the community, "If you don't climb Mount Fuji during your tour, you'll definitely get orders to come back to Japan,” or

Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

something along those lines. I was not fortunate enough to climb Mount Fuji while I was stationed in Japan. So, what's the next best thing? Flying as close to Mount Fuji as legally allowed, and as high as the weather and the limits of NATOPS allowed. Thankfully it was a clear day and all of us were able to enjoy not only Mount Fuji, but also the neighboring cities, beaches, shrines, castles, and each other's company one last time together. I honestly can't think of a better place to enjoy a helicopter flight.

What are your goals for the future? There are several goals that I've set for myself in the future, but the one current and near-future goal I am currently tackling is to complete my Bachelor of Science Degree in Kinesiology, with an emphasis in Fitness Specialist at San Diego State University in the next two years.

24

Crossword Think you know everything about SAR? Try your hand at this crossword puzzle. Good luck! By LT Elisha "Grudge" Clark, USN

Down:

Across:

1.Recovery for hypothermic survivor 2.Designated by SMC 3.Cervical _____ (spinal immobilization) 4.Type of deployment. Staying on the hoist 6.Personnel ______. Procedures in JP 3-50 7.Sucking chest wound dressing 9. Lights sans smoke 14.SAR Readiness- ready for launch 15. Light (as in weight, not brightness) in the water 17. _______, Breathing, Circulation 19. MOI (the m) 20. Opposite of calm 23. Type of litter

5. Situation Report 8. ______ spacing; in a search pattern 10. Equipment for double lift 11. Diving related injury 12. Hand-held light; re-establish visual contact 13. RCC Norfolk; city in VA 16. Fixing a severed hoist 18. SAR gear storage; in aircraft 21. Acronym; patient evaluation 22. Type of search pattern; specific coordinates 23. SAR _____ (not SAR capable) 25

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

View from the Labs Why We Wrote Leave No Man Behind By CAPT George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.) The subject of this issue of Rotor Review is “So Others May Live.” It is also the twentieth anniversary of when my partner (the late TomPhillips) and I came up with the original germ of an idea to write our book Leave No Man Behind: The Saga of Combat Search and Rescue. I thought this was the time to tell, as Paul Harvey famously said, “The rest of the story.” First, this isn’t about selling copies of the book. For those of you in the San Diego area, it is available at the NHA Office, the Coronado Public Library, and elsewhere. For others further afield, we are mindful that other libraries have a copy. Here is the journey that Tom and I began, and it happened, to no one’s surprise, at our NHA Symposium. Full disclosure, it was on Friday night, the last day of the Symposium, and as the old saying goes, “When you drink enough beer, anything is possible.” During the 2003 NHA Symposium in San Diego, we decided to write a book about the history of combat aircrew rescue. It became a five-year labor as we discovered the astounding ups and downs in the saga of combat aircrew rescue, and a rich heritage and history which completely surprised us. We wouldn’t trade the experience for anything. Here is why we wrote the book. There has never been a time in history when it was good to be a POW: From the life sentence in the slave galleys of antiquity, to dungeons of medieval times, to appalling prison hulks of the Napoleonic Era, to the shame of Andersonville and similar northern prisons of our own Civil War, to starvation, disease, and even cannibalism of the Japanese POW Camps, or the Katyn Forest and Malmedy Massacres of POWs in Europe in World War II, to the brainwashing of Korea, to the unspeakable isolation, torture, and cruelty of the Hanoi Hilton, in living memory.

Rotor Review #162 Fall '23

But today, there may not be any POWs. Prisoners have already been tortured, dismembered, and dragged through the streets, and beheaded while screaming for mercy on the internet for billions to see. For that reason, today’s CSAR crews must live up to the imperative to “leave no man behind” as never before. But will they be as ready as CSAR crews in past conflicts? We wrote the book to tell the riveting stories of astonishing rescue missions over the years, and to show how the discipline grew despite repeated setbacks, as technology, doctrine, tactics, and techniques evolved gradually into the skill sets of today’s military. The March 2011 crash of the Air Force F-15 Strike Eagle over Libya and the recovery of one of the two crewmen via a Marine Corps TRAP Mission was a stark reminder of the criticality of having CSAR forces always formed and ready for every military mission where our aircraft go in harm’s way over enemy territory. The most important lesson learned from Vietnam era combat rescue was the dramatic improvement in performance when Navy combat rescue units, after four years of frustration, finally shed all other collateral missions and dedicated their entire focus to the sole mission of combat aircrew rescue. Just as our book hit the shelves, USD AT&L, the Department of Defense’s chief weapons buyer, declared that we don't need dedicated CSAR forces, and that any helicopter in the area will do just fine. Then-Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates, was fond of saying the department didn’t have the money to buy what he called “exquisite weapons.” He made this point repeatedly in speeches across the country. But we believe that with a DoD budget now in excess of $850 billion a year, if the nation buys only one exquisite weapons system, it should be a CSAR platform that can snatch our warriors from the clutches of the enemy. Likewise, if our helicopter pilots and aircrews, who have CSAR among many other missions, achieve an exquisite degree of proficiency in only one mission, it must be CSAR. Our people deserve nothing less. Our young volunteer airmen join up with an implicit understanding that, if they get stranded behind enemy lines, the nation has the best combat rescue capability possible and will stop at nothing to go get them before they fall into enemy hands. Dare we as a nation have it any other way? Perhaps enough has been said. “So Others May Live,” is our core competency as Rotary Wing Naval Aviators. There are lessons learned the hard way that we should mind lest they happen again. That’s why we wrote Leave No Man Behind: The Saga of Combat Search and Rescue and would write it again today. 26

27

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

So Others May Live So Swimmers May Be Paid

By AWRCM Justin “Cali Condor” Phillips, USN

I

n recent national news, the Navy made headlines with its inability to meet 2023 recruitment quotas, falling short by 7,000 Sailors. As a response to this challenge, the Navy is actively exploring incentives to retain its top talent. Notably, recent initiatives aimed at increasing Selective Reenlistment Bonuses have been tracking in the right direction to help entice Helicopter Rescue Swimmers to “Stay Navy,” but more can be done. Over the last three years, Senior Enlisted Aircrew Leadership has been successful in increasing career orientated compensation, demonstrated by the transformation of Career Enlisted Flyer Incentive Pay (CEFIP) into Critical Skill Incentive Pay (CSIP). While the community has yielded success in these ventures, multiple attempts to correct shortfalls in Helicopter Rescue Swimmer Special Duty Assignment Pay (SDAP) have not gained traction. Straight out of the OPNAVINST 1160.6C, “SDAP is a monthly pay used to help obtain high quality enlisted personnel for designated special duty assignments that are considered extremely difficult or involve an unusual degree of responsibility.” Plainly put, SDAP is how the Navy rewards Helicopter Rescue Swimmers for their demanding duties requiring extraordinary effort” There is a catch though. The SDAP authorization charts limit how many billets can receive this incentive at each qualifying command, referred to as “Billets Authorized.” For example, if a squadron is authorized to have 24 Helicopter Rescue Swimmers, they will only have 24 SDAP Billets eligible for the incentive. Unfortunately, for some commands the number of Rescue Swimmers onboard varies from undermanned to overmanned at times. This situation is cyclical and depends on Sailor rotation dates, deployment build ups, and inventory of Sailors who can fill these billets. It is extremely difficult for entities in Millington to keep the numbers onboard each command at exactly the right number of “Billets Authorized” at all times. A Sailor who is rotating out of their command due to their Projected Rotation Date, will likely have their replacement onboard either several months before or after they transfer. This can prove to be problematic when the command is trying to determine who receives SDAP and who does not. At times, a squadron may find itself temporarily carrying up to four or five more Rescue Swimmers than authorized. But who gets paid SDAP and who does not? Historically, this has been the proverbial bullet taken by Senior Aircrewman Leadership. An Aircrew Shop Chief will usually sacrifice his/her SDAP before making a junior Sailor give up their incentive pay. Unfortunately, there are only so many Chief billets available before junior personnel start losing out on their SDAP. Based on the qualifying criteria for SDAP in the OPNAVINST 1160.6C, all Navy programs listed under the “Warrior Challenge Program” receive this incentive to varying levels. The Warrior Challenge Programs consist of SEAL, SWCC, EOD, DIVER, and lastly, Helicopter Rescue Swimmers Rotor Review #162 Fall '23