For over five decades, experimental printmaker Rosemary Feit Covey has maintained a long standing engagement with psychologically challenging subject matter. While she has employed a wide range of media and narrative subjects, her work displays consistency both in her technical prowess as a printmaker and in her desire to explore aspects of human nature that are intuited, repressed, and universal.

This document highlights some examples of Feit Covey’s work for the purpose of illustrating her complex and cohesive vision as it evolves through a lifetime of making art. Working primarily as a printmaker, she uses the replication inherent in all print media to create large images and one of a kind pieces. In each series, the media is bent to the intent of the project.

Part one reveals how Feit Covey’s work illuminates the fragility and disintegration of human, plant and animal life. Created in the last thirty years, this work is the result of Feit Covey’s lifelong interest in the dichotomy between beauty and vulnerability as it is expressed through vitality and decomposition.

Part two explores themes of health, science, death and disease. Feit Covey is particularly interested in how societal responses to disease have evolved over time, while core human fears remain constant.

As shown in part three, her highly collaborative installation projects reflect on a lifetime engagement with how we collectively and individually process responsibility and guilt. For many of these, she has collaborated with dancers, composers and the public to create spaces that envelop and implicate the viewer.

In part four, women’s narratives unfold as Feit Covey untangles the complicated and sometimes paradoxical aspects of what it means to be feminine: pleasure, pain, objectification and loss.

Rosemary Feit Covey is one of the preeminent wood engravers working today. While she is conspicuously adroit at handling the tools of her craft, she rarely calls attention to her technical virtuosity for it’s own sake. … Superior art is always the synthesis of sound craft, a significant idea, and an innovative approach... Only with the proper balance of conception and prowess is art elevated to a higher realm of significance .

Rosemary Feit Covey’s best work consistently aspires to this more elevated attainment in art.

Feit Covey’s current focus on environmental concerns is informed by 20 years of collaborations with scientists, throughout which biology, ecology and mortality have remained steady themes of her practice. On a macro scale, individuals form a complicated web of relationships and actions have far-reaching implications; at the same time, each death, even of a tiny insect, is noted and marked as an individual loss and painful reminder of mortality. Taken as a whole, this collection of work illuminates the fragility of life on our embattled planet and recognizes the catastrophic ecological losses that mark our current era while turning a hopeful eye towards new horizons.

6 — Fish 2012

12 — Crossing the Line 2012

14 — Broken Earth 2020

16 — Before the Aftermath 2023

18 — Thanatopsis 2024

Feit Covey uses her craft in unconventional ways, often creating one-of-a-kind pieces carved from multiple blocks and reusing blocks hundreds of times. Thus, her wood blocks form a library of her own images that she can appropriate for different works. Fish was made from over eleven blocks, overlapped and reframed multiple times. Trained as a traditional printmaker and working for decades as a wood engraver, Feit Covey’s work has evolved in the last fifteen years to push beyond the time-honored technique of woodcut as she addresses modern concerns with a fresh contemporary quality. This process allows Feit Covey to revisit and reinterpret themes from her oeuvre and her life, refreshing and revitalizing ideas as they become relevant.

Fish was inspired by the 2010 oil spill in the gulf of Mexico, the largest disaster of its kind, killing eleven people and destroying countless wildlife. The unrefined oil turned a red brown in the water, a beautiful color against the blue waters of the gulf. In Fish, Feit Covey leverages this juxtaposition of beauty and tragedy in her color palette.

The title of the work, Panspermia, is a Greek word that translates literally as “seeds everywhere.” The panspermia hypothesis states that the “seeds” of life exist all over the Universe and can be propagated through space from one location to another. The theory that plant matter could travel through space and propagate life had been discredited, but it gained traction when it was found that lichens could survive in extreme conditions.

For Feit Covey, lichens serve as a metaphor for the vastly unknowable interconnectedness of nature. She created Panspermia III after making five pieces on lichens aided by Karen Dillman, an ecologist for the USDA forest service. As Dillman explains, “Lichens are some of the most complex life forms on earth. Each lichen represents at least two but sometimes three kingdoms of life intimately growing together. As humans we want to control nature, yet we have not figured out a way to make lichens due to this intricate partnership.”

By working in a mode of abstraction, Feit Covey introduces lichens as an example of the ancient hypothesis that has piqued the interests of scientists like Francis Crick and Stephen Hawking. The shapes and sense of emitted light from the work can evoke a range of associations, from a map of cities casting light pollution in the night to clumps of galaxies seen from light years away.

The work is a masterful example of Feit Covey’s innovations in experimental printmaking Layering and reworking wood blocks, printing them and cutting them as jigsaw puzzles, each new piece is a technical exercise in re-imagining the original wood blocks and pushing the very nature of the medium further as both editioned pieces and as one of a kind works on canvas.

In Usnea Longissima , Feit Covey continued her exploration into lichens in collaboration with ecologist Karen Dillman. Due to the intricate balance of organisms that operate in a lichen community, lichens serve as signifiers of the health of an ecosystem. Feit Covey’s process of carving, printing, cutting, and layering is similarly complex, and it allows her as an artist to interact with the subject matter as a participant. Lichens emerge as a metaphor for the delicate resilience of life on earth and as a reminder of our own role in our ecosystem.

As Dillman shared, “Bringing lichens into the contemporary fine art world through Rosemary Feit-Feit Covey heightens the awareness that these under-appreciated organisms also display beauty, texture, and artistic composition in nature, simply by being.”

Rosemary Feit Covey has taken what must be the most resistant of media and used it to powerful effect . I usually associate wood engraving with very literal renditions, but in her expert hands she conveys imaginative, unsettling and discomforting visions.

Roberta Waddell, Curator of Prints and Drawings, New York Public Library, 1998

Crossing the Line exemplifies Feit Covey’s balance of narrative depth and abstraction. At first, the viewer is drawn to the compositional balance, bright colors, and botanical theme suggested by the decorative arrangement of gingko leaves. Only by looking closer one might sense the personal tragedy that seeps into the piece as suggested by the blood-red pool. Unknown to the viewer, hidden underneath the leaves, is the shape of a figure and a bullet. These elements can only be perceived subliminally as they are covered by leaves on the surface; Feit Covey’s additive process allows her to imbue subliminal messages as she physically buries symbols of intense personal meaning.

The work is made from just five wood engravings, printed many times, with each leaf print cut out and worked together into a large composition. It is a highly labor intensive piece that reveals the importance of the process to Feit Covey, which allows her to emotionally process events from her own life while creating a work that can operate on multiple levels of meaning to resonate emotionally with a viewer. In later versions of Crossing the Line, the figure is removed and the printing is done by layering rather than cutting.

Crossing the Line

Moved by recent climate disaster scenarios in South Africa—the country of her birth—Feit Covey’s most recent work responds to the fleeting nature of news cycles and the failure of journalistic channels to manifest sustained public awareness of such crucial issues. Having witnessed this subject matter quickly fall from the front pages, Feit Covey understands her work to serve as an enduring reminder of environmental crises within a global consciousness. Of this profound responsibility as an artist in the present moment, Feit Covey affirms, “In this manner, I am committed to using my skills to portray this delicate balance as we reach a precipice.”

Through delicate lines that comprise masterful compositions, Feit Covey’s work operates at the intersections of beauty and terror, depicting melancholy aesthetics of mourning. From a mass of opalescent strokes, Feit Covey’s Broken Earth (2020) pictures a heap of carcasses, inspired by Feit Covey’s horror of an imagined parched earth. Elsewhere, blooms of pigment suggest oil spills, and falling petals hint at impending decay. Through a push and pull, characterized by sensorial enticement segueing into gripping existential inquiry, the artist’s foreboding imagery unmasks that which is hidden in plain sight.

Before the Aftermath demonstrates Feit Covey’s commitment to meaning as a process that unfolds between the work and the viewer rather than a story literally transmitted by the artist. The dark lines and patches of blue suggest tree branches and birds as they are cast against a cold gray-white background.

Denser lines in the foreground give way to more open space in the center, creating an illusion of looking up towards the sky from a forest. Evoking frantic birds and rustling branches, Feit Covey creates a sense of energy and confusion. While the scene could be the aftermath of a catastrophic event, it could also be the moment before a storm, when winds sweep paper in the air and birds fly up and away.

Before the Aftermath

Thanatopsis is the portmanteau of two Greek words: Thanatos, the god of death, and opsis, meaning sight. Together, they mean seeing death or a consideration of death.

Death is a potent theme for the mediation on fragility and disintegration. The wood engravings and excavation of the canvas attest to burial and decomposition contrasted with beauty and complexity of the image. The piece takes further Feit Covey’s work with scientists and scholars of mycology and references the poem by William Cullen Bryan, who’s poem by the same title mirrors her lifetime of creation of work on these themes.

To create this piece, Feit Covey cut out and built up sections of the canvas to create a feeling of recession and projection from the surface of the picture. This innovation continues her progression as seen in other pieces beyond printmaking and into the realm of sculpture. Just as death can alternately be an abstract concept and a visceral tangible reality, Feit Covey’s canvas oscillates between image and sculpture, evasive and decisively present.

Thanatopsis

Chronic pain— or any illness for that matter— has the ability to reduce us to our most basic selves. We feel diminished and removed from the trappings of our daily lives …. We are base,a body, a specific pain; our mortality suddenly in relief. It is somewhat the same producing artwork. Art is supposed to sort and sift, reducing an idea to its core elements…it is a visceral experience beyond words. .. It means solitary work for the artist and a willingness to reconnect to past pain, both mental and physical.

Rosemary

Feit Covey Giordano, James, Ed., Maldynia Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Illness of Chronic Pain, Maldynic Pain in Image and Experience, p.123-132, 2011. Written while an artist in residence at Georgetown Medical School, with six plates illustrating the artist’s work

Feit Covey’s work explores the intersection of historical narratives, social dynamics, and contemporary scientific understanding of diseases. Her Brain Tumor series delves into the psychological impacts of disease, death and dying. Her personal connection to her subject matter translates into an emotionally charged experience on the page. In her Vanitas, Vanitas series, Feit Covey skillfully blends historical narratives with modern scientific discoveries, creating a rich tapestry of iconography that bridges past and present. Through these series, Feit Covey invites viewers to contemplate their own place in the grand narrative of human health and mortality. The prints serve as a reminder that despite tremendous advances in medical science, we remain vulnerable to the caprices of nature and our own biology. At the same time, the works celebrate human resilience and the ongoing pursuit of knowledge in the face of these challenges.

WORK DISCUSSED IN PART II

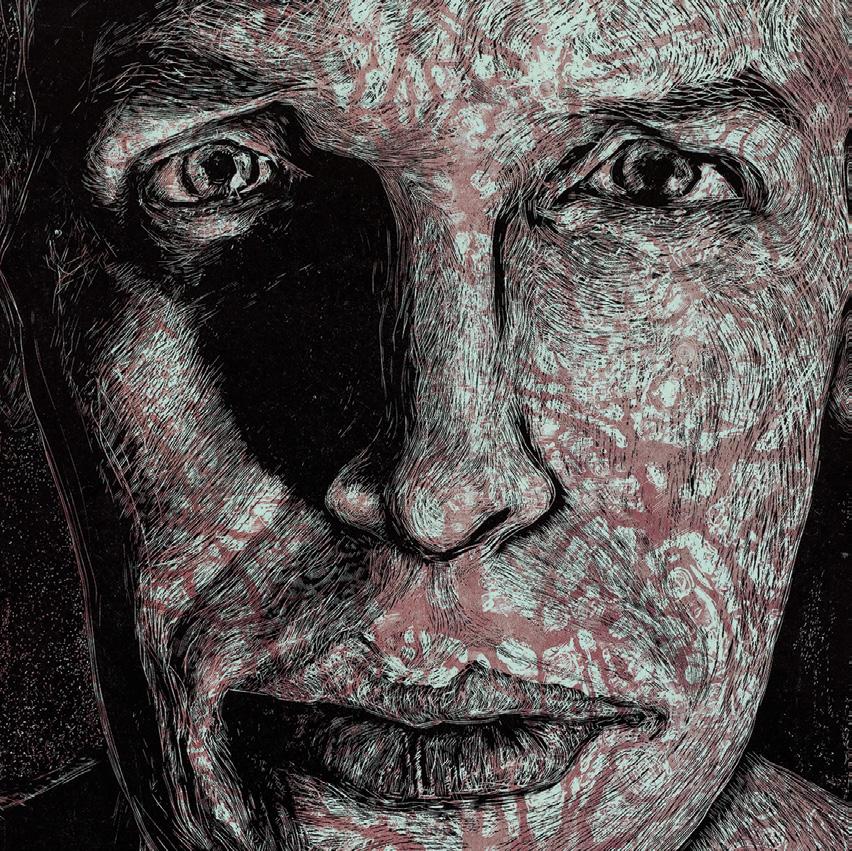

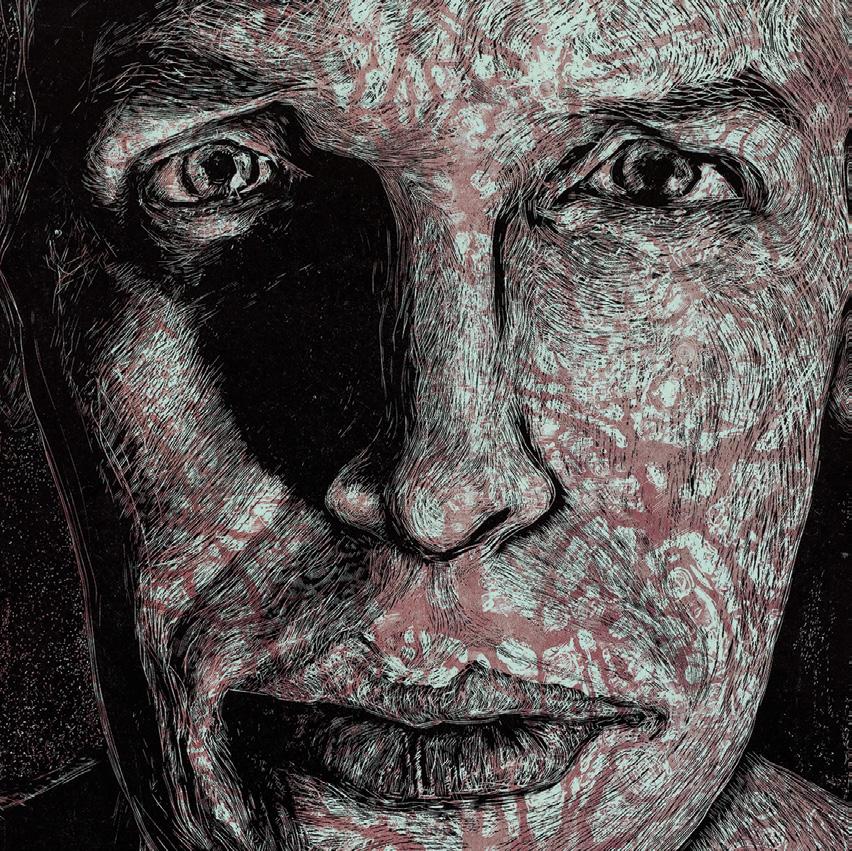

PAGE 22 — David with Astrocytes 2006

PAGE 24 — Lisa at Twenty Two with Baby 2003

PAGE 26 — Vanitas, Vanitas series 1996-1998

Ring Around the Rosie Antigenic Shift

David with Astrocytes - The print is the eighth in the Brain Tumor series. David with Astrocytes uses two different resingrave blocks. The background is “Astrocytes” and the foreground is an image of “David.” The editioned prints have variations in the printing. The subject of the work, David Craig Welch, commissioned Feit Covey to chronicle the development of his brain tumor over the course of three years. Welch gave Feit Covey unfettered access to his medical procedures and doctors, insisting that she create an honest portrayal of his experience. During this time, Feit Covey created a series of forty photographs, twenty woodcuts, and five sculptural pieces.

David with Astrocytes is made from three prints combined as one by hand printing and layering and then printing the final layer using chine-colle on a Vandercock printing press. In the portrait, Welch’s face is inexpressive while his eyes reveal repressed pain. The titular astrocytes are manifested plainly on his face, although the star-shaped glial cells are usually hidden in the brain and spinal cord. Honoring his wishes to not have his reality expressed through horror, Feit Covey created a psychologically provocative portrait that conceals as much as it reveals, expressing the complex and subjective way we all grapple with death.

Welch’s last coherent words before his death, “Reality, Confront. End,” were used as the title of the exhibition of works borne out of their collaboration. The project took on a larger life as it became an animated film, was written about in Cancer Digest, The LA Times, the Washington Post and was highlighted in an interview on PBS National Radio. Millions of brain tumor patients around the world followed David’s blog, 38Lemon, where he explained his journey, scientifically, emotionally and artistically.

Feit Covey’s portraits of real people exhibit a startling honesty, borne out of her commitment to getting to know the subject on a personal level. The subject becomes a collaborator, as Feit Covey is committed to understanding the psychological state of the person in an intimate process. Lisa, recently released from a hospital program, asked Feit Covey to do a portrait of her pet rabbit, named Baby. As a part of her program, Lisa was tasked with caring for another living creature, and it is the relationship between Lisa and her pet rabbit that became the subject of this engraving.

Lisa at Twenty-Two with Baby captures the complicated relationship between health and vitality; the subject is a woman who was clinically underweight yet also praised by others for her slim model-like appearance. Her delicate embrace of her pet and penetrating gaze at the viewer suggests a complicated strength that arises from the vulnerability of caring for others.

Vanitas, Vanitas is a series of prints on the subject of reemerging and recalcitrant diseases. Vanitas refers to the genre of Dutch seventeenth-century still life designed to remind the viewer of the fleeting quality of life. Traditionally, symbols are included in work to reveal the earthly values and spiritual concerns of the subject; while a magnificent collection of books and scientific instruments may reflect the owner’s pride in his education, a skull on display is a vivid reminder that, no matter how learned he was, death still awaited him. The prints in Feit Covey’s Vanitas series similarly employ rich iconography, blending historical and social histories with modern scientific discoveries of diseases, to remind the viewer of their own mortality.

This is a vision of what’s raw, what’s inchoate, what’s undifferentiated. Rosemary turns in specificity for sameness. Well, that can be as scary and menacing and disturbing as anything else she’s presented before. At this scale of revelation, the mode of expression must be skillfully, hauntingly generalized.

Growing up in a South Africa steeped in the legacy of apartheid, Feit Covey was aware at a young age of how historical legacy can breed a sense of collective guilt that complicates how an individual relates to the collective.

Feit Covey has explored the notion of collective guilt in her native medium of wood engraving and printmaking, and in the past two decades she has expanded into installation art, allowing her work to enfold and implicate the viewer as a participant. Her willingness to adapt her medium reveals her commitment to communication and expression over loyalty to pure technical prowess.

Sins of the Fathers 1992

36 — O Project 2005-2020 PAGES 38 — Red Handed 2013

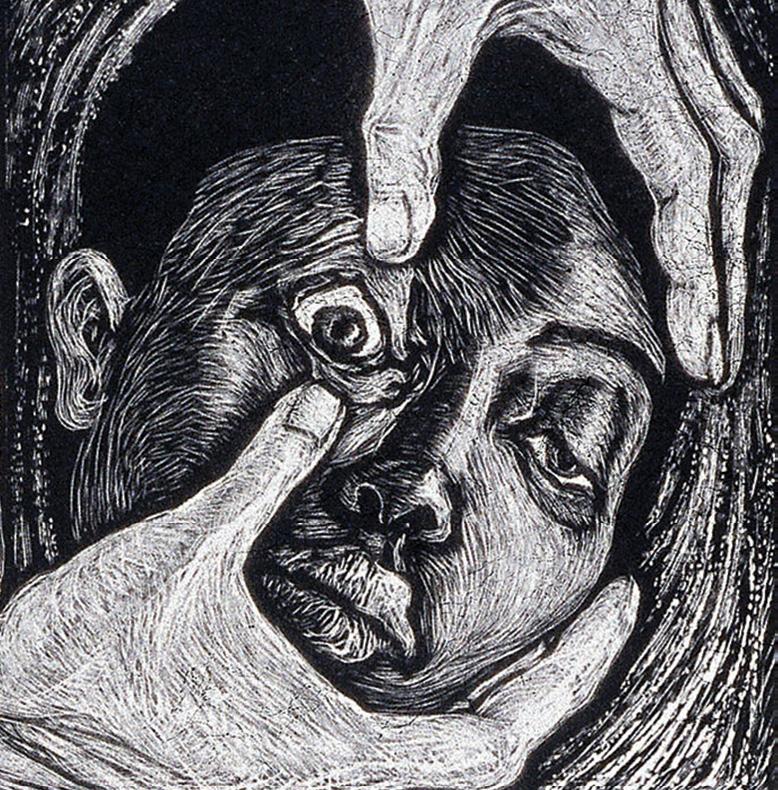

In Johannesburg 1968, two white hands pry open the eye of a black figure. Almost viscerally painful to look at, the work cannot be ignored - Feit Covey’s engraving performs a double act of forcing us to look at a face that is also being forced to look back at us. Feit Covey creates a false frame by enclosing the main figure in a black rectangle, only to break it by having the hands come out of seemingly nowhere. By interrupting the illusion of the work of art as an image, she calls our attention to the idea that things might not be as they seem. Who’s story is this, and who is telling it? Are we complicit in whatever horror is happening? Or are the hands actually helping by performing some sort of medical exam?

The discomfort that we feel calls into play the notion of guilt and empathy. We are uncomfortable, yes, but surely not as much as the figure in the picture. How do we deal with this feeling? As usual, Feit Covey leaves us with more questions than answers.

Johannesburg 1968

Johannesburg 1968, 2001, 6"x8" Resingrave engraving on paper, edition of 60. LEFT: Johannesburg 1968 (detail)

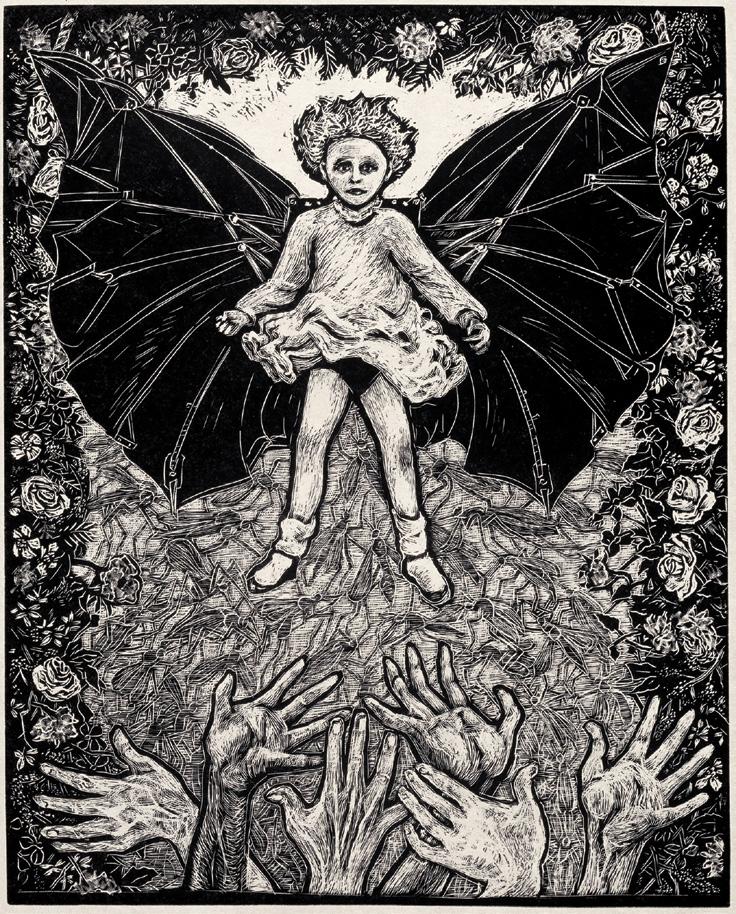

In South African Childhood, 1984, Feit Covey communicates how happy childhood memories are re-cast in the unflattering light of hindsight, when only in adulthood the full landscape of inequality and oppression is fully understood.

The right side of the composition feels nostalgic and familiar - the people lounging in the background, the child wrapping her arms around herself because she is cold or uncomfortable. This could be anyone’s childhood - except the figure on the left hand side reminds us that there is something off here. The picture presents a hierarchy that is difficult to ignore - the child stands in the foreground while a black person, physically situated behind a fence, holds a tray with delicate teacups. While the child looks off to the side, the man carrying the tray levels the viewer with an inescapable gaze. The circuit of gazes communicates their levels of awareness - the people in the background, oblivious; the white child, uncertain; the black man, highly aware, or perhaps hiding behind an expressionless affect, hiding his reaction.

We are left uncomfortable and without any clear sense of blame or responsibility, which is characteristic of Feit Covey’s work inspired by her own South African childhood.

Sins of the Fathers is divided into registers, with two girls at the top, mourning over a mound of dirt. Below them is a body, and below that are layers of innumerable skeletons, their bones gradually more decayed as they are buried under more layers. This engraving reveals Feit Covey’s uncanny way of making the uncomfortable beautiful. Each bone is rendered with care, and they weave together in a gnarled mass that feels organic and almost decorative.

Anthropologist and author Alexa Hagerty referenced Sins of Our Fathers in a book that takes the reader with her on her journey working with forensic teams and victims’ families investigating crimes against humanity in Argentina and Guatemala. The book combines anthropology, history, and personal narrative, covering many themes that Feit Covey has engaged with throughout her career. That her engravings speak to scientists across fields is a testament to the rich narrative and psychological potential in every piece.

It is common for Feit Covey to be influenced by the people who are influenced by her work; Haggery’s book resonated with Feit Covey’s personal experience in Argentina and her firsthand encounters with stories about family members who have been lost.

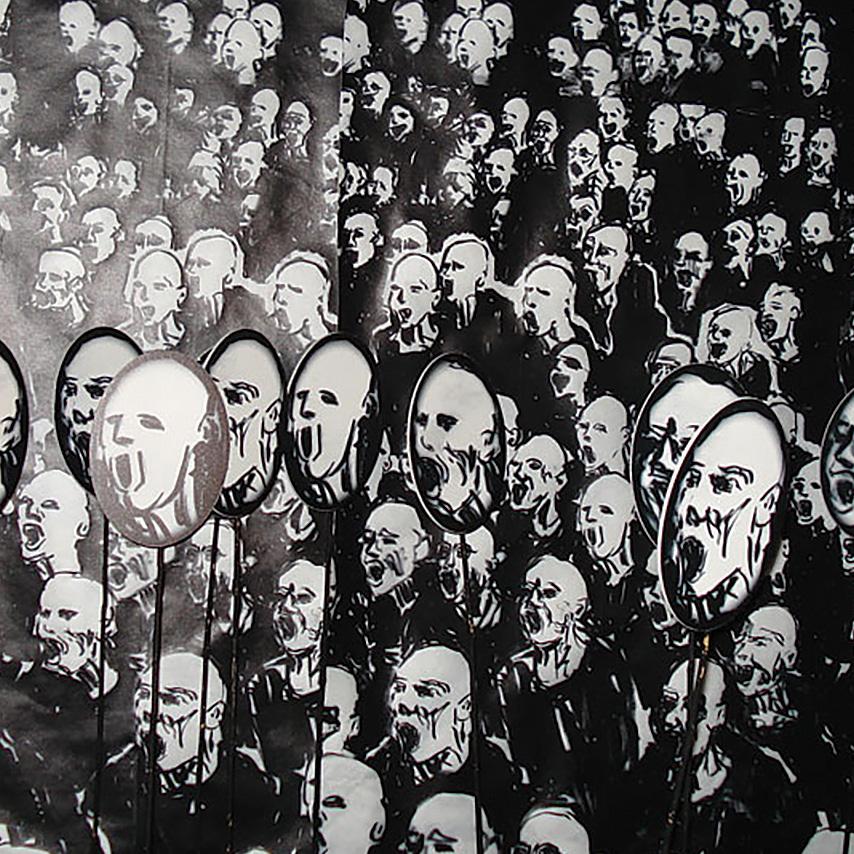

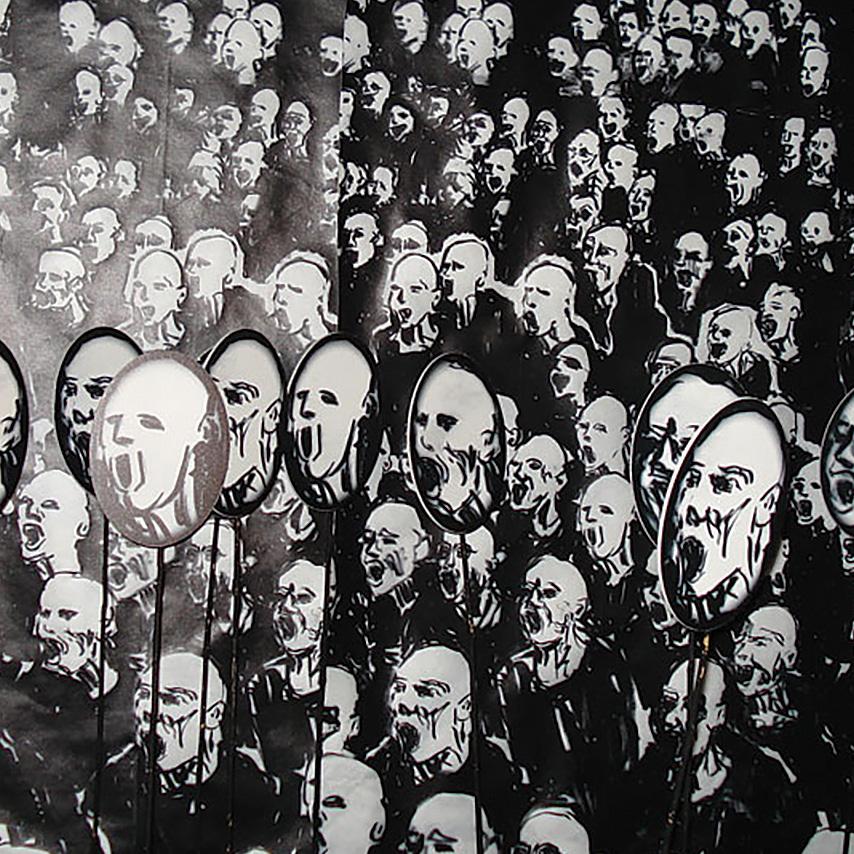

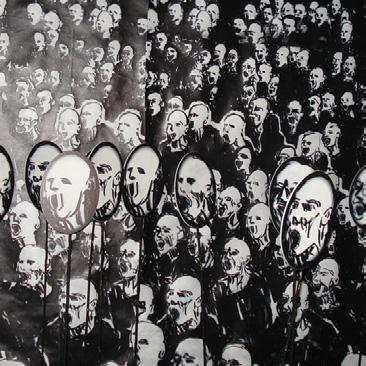

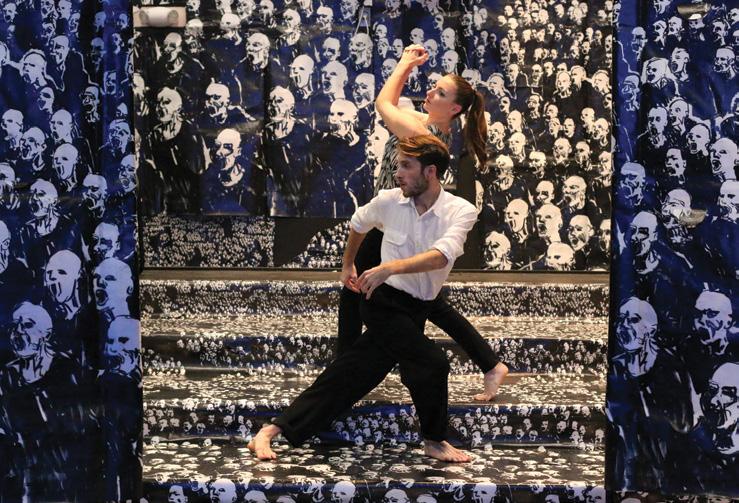

The O Project had its premiere as a large-scale outdoor sculptural piece at the Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington, located just minutes from downtown Washington DC. Printed on over 300 feet of Dupont Tyvek banner media, it wrapped the exterior perimeter of the building. As a printmaker, Feit Covey is always conscious of the medium and the relationship between reproducibility and value; print runs and editions are carefully specified, and the woodblock itself occupies an interesting space as an original work of art and a tool of production. With the O Project, one of Feit Covey’s drawings is photocopied over and over - greatly expanding the accessibility of the image.

Physically shifting the work from a museum context and into the realm of the public allowed it to reach a broader audience. Rather than consciously engaging with art, as is usually the case with people visiting an art museum, passersby were confronted with the work as they were going about their daily lives.

The O Project quickly took on a life of its own as its open-ended message allowed for application in a variety of contexts to communicate different messages. The opening of the project included a hundred masks in a performance piece created by Bosma Dance Company in collaboration with the artist, and the initial exhibition was held concurrently in Toronto at Brayham Contemporary Art. The O Project was also part of the “Abductor” at the Burning Man Festival in the Nevada desert. This large installation was designed in Los Angeles and featured an industrial club scene vibe.

The O Project continues to expand and spread via both high and low tech means, its purposely ambiguous message being interpreted and re-shaped by individuals world wide. The O Project has also been an integral part of multiple social justice events, wrapping a building in Reno Nevada and displayed as large scale banners on the mall in Washington, DC. It has been printed on t-shirts and projected at the opening of Art Whino in Washington DC., at rock concerts throughout Europe, and nightclubs in India.

03 Jane Franklin Collaboration: Migration Dance, Theater on the Run, Arlington VA

04 Jane Franklin Collaboration: Migration Dance, Theater on the Run, Arlington VA

05 The 0 Project (gallery wrap), Brayham Fine Arts. Toronto, Drawing, Printmaking on Tyvek with 100 masks, 15 x 200 feet

06 Detail of The 0 Project (gallery wrap), Brayham Fine Arts. Toronto

07 0 Project (banners and masks), Rally for Social Justice, Washington Monument, Washington DC, 10 x 9 feet

In Red Handed, Feit Covey forces the viewer to confront collective and personal guilt in a visceral way; full engagement with the work requires the viewer to walk on top of it, which many people do hesitantly or not at all. Walking on top of art breaks down the barrier between viewer and art that is traditional. As one walks on top of the jumbled mass of figures, one feels as if they are contributing to whatever horror has just taken place. It feels as if Feit Covey has placed us in an impossible situation: either refuse to engage, which feels like complacency, or tread upon the work, which feels like violence; we are caught red-handed.

This exploration of collective versus personal guilt was inspired by the works of Doré, Modigliani, and Picasso. Red Handed also documents the artist’s personal situation. The artwork is a raw reaction, and therefore cathartic, both for the artist and the viewer. Viewers have remarked that the work reminded them of fighting in a war or grieving a car accident; others have seen references to Dante’s Inferno, the Holocaust, or Iraq.

...Covey’s suite recalls Hieronymus Bosch’s images of teeming , tormented reality humanity, as well as Francisco Goya’s despairing Black Paintings. Hundreds of red-handed blackon-white androgynous figures line the walls and even writhe underfoot... Her ‘Red Handed’ pictures are looser, messier and more impulsive; precisely etched lines yield to expressionist strokes and splatters, sometimes atop collaged layers.

Mark Jenkins, The Washington Post, 2013

Handed Installation, Wesley Theological Seminary , Washington, DC. Art Installation and Dean’s Artists Talk, classes and student interaction.

Something exciting … happens when she deals with the nude, seemingly her own self-portrait, where a strong, sensuous element occurs when the engraving needle models the figure as though it were caressing the flesh in a manner not unlike Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), who used thick pigment to almost sculpt the form he was painting. The same electric vitality exists in …

Feit Covey’s

works.

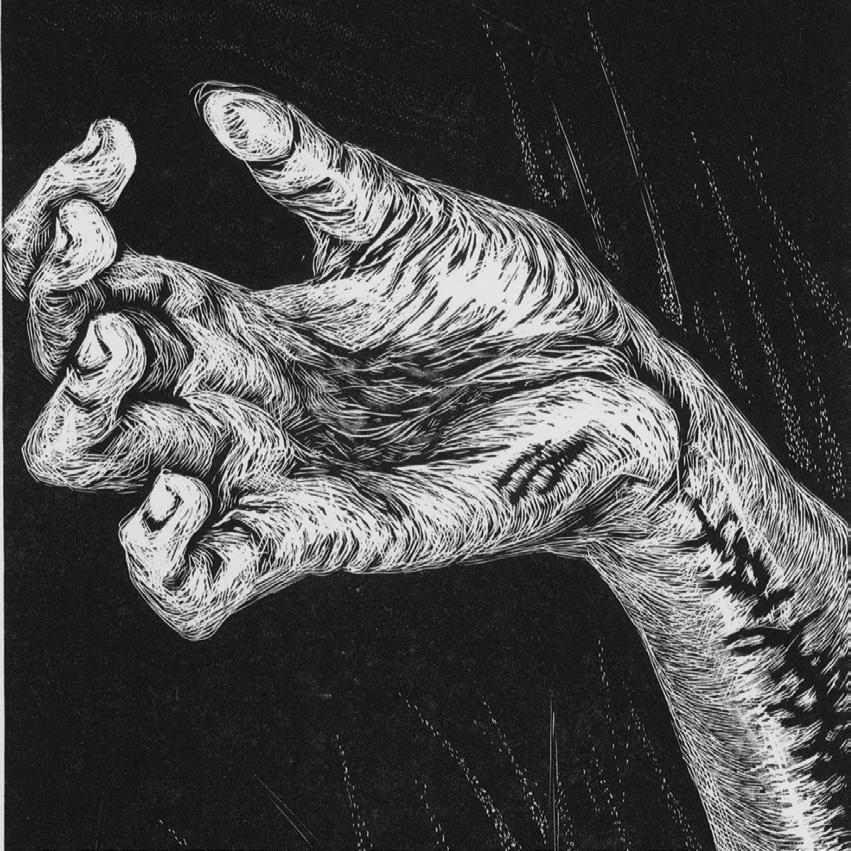

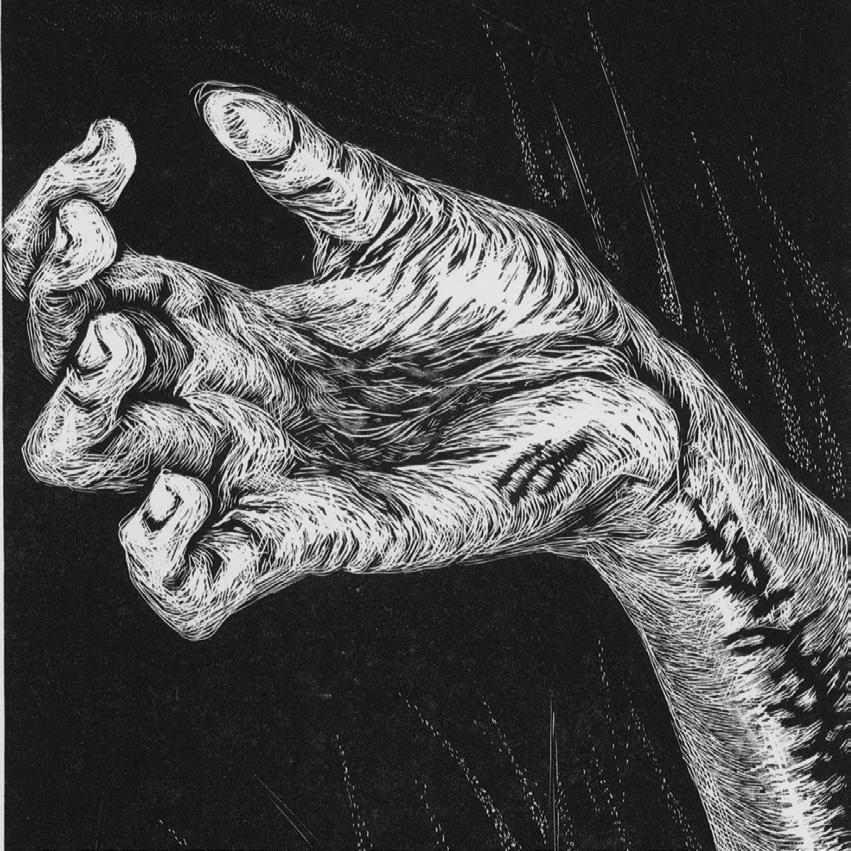

Feit Covey’s explorations of the female experience coalesce around a few central themes: the voyeuristic gaze, objectification, and the line between pleasure and pain.

In examining the voyeuristic gaze, Feit Covey’s art often subverts traditional perspectives, turning the viewer’s own act of looking into a subject of scrutiny.

Objectification is another critical focus in Covey’s work. These pieces serve as a stark commentary on how women’s bodies are often reduced to commodities in media, advertising, and personal relationships.

The exploration of the line between pleasure and pain in Feit Covey’s art is particularly nuanced. Through a combination of sensual imagery and elements suggesting discomfort or constraint, the artist invites viewers to consider the complex interplay between desire, power, and vulnerability in women’s lives.

By focusing on moments and stories that are highly charged, Feit Covey untangles how femininity is constantly redefined and reshaped, from childhood to adulthood.

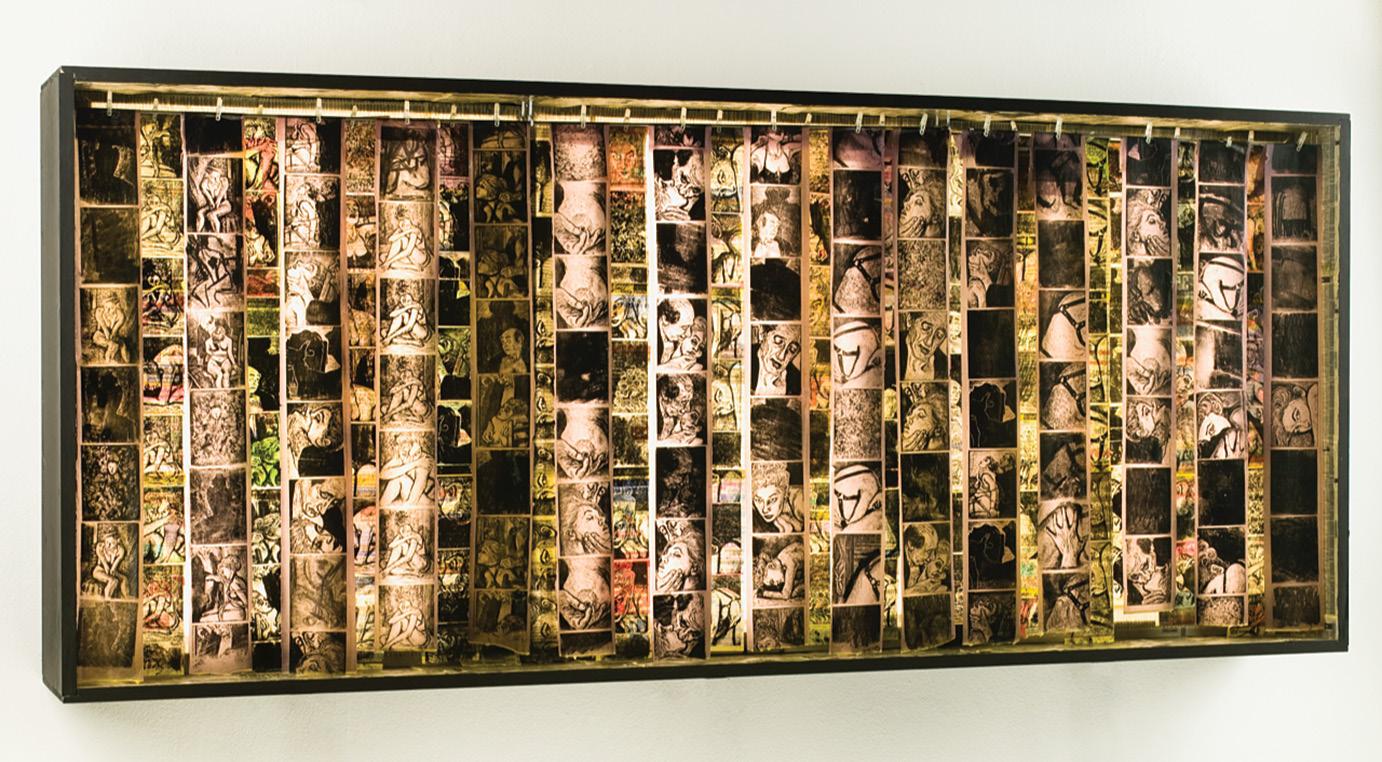

Based on the relationship between an actual couple, Strip explores obsession on several levels, analyzing the connection between pleasure and pain. Derived from drawings executed by the artist in collaboration with the couple, these engraved prints tell the story of their complex relationship.

Using light boxes designed for the project, hand printed on Japanese paper and phone book pages, encased in encaustic medium, each strip suggests a voyeuristic photographer’s film hanging to dry. When displayed in groups horizontally, the effect is akin to dark comic books and graphic novels. With projects like Strip, Feit Covey demonstrates her ability to wade into situations and grapple with subject matter that may be uncomfortable for most people, yet her commitment to communicating the human experience takes precedence.

In Peep Show, Feit Covey combines the secret and prurient world summoned by the modern connotation of the term “Peep Show” with the innocent world of Victorian-era peep show boxes.

Engravings of women in suggestive clothing and poses are placed inside hand-crafted boxes. The pictures can only be seen through a small key hole, which forces the viewer to awkwardly bend over in order to see the images. The boxes themselves are custom designed and hand-crafted by a master cabinet maker. They are modeled on elegant peep show boxes circa 1820 and available in both Cherry and Walnut. Each box has unique Victorian style hardware and storage space for ten prints.

Even though the engravings are only suggestively sexual, the physical acts required to view the images - bending over, peeking through a keyhole - turn the viewer into a voyeur. When we peep through a keyhole, we are aware that we should not; everything we see is private and therefore more titillating. The words Peep Show themselves conjure images of seedy back rooms where sexual contact is limited to a one-way viewing.

In this series, Feit Covey again demonstrates her willingness to expand beyond the scope of the woodcut, folding in elements of conceptual and installation art in order to highlight the power of the gaze and the relationship between the viewer and the subject.

Women’s pain is often ignored, pathologized, or sexualized. The Porcupine Girl seems to be experiencing several of these feelings at once. We feel empathy for her as her body is literally torn apart, but she also seems unapproachable; the quills that emerge painfully from her back protect her from anyone who might get close, but they also seem to prevent someone from helping.

Feit Covey’s talent for woodcut is on full display as she handles a viscerally painful subject in a way that is nevertheless aesthetically pleasing. This has the effect of drawing the viewer in, perhaps despite our wishes to look away. Her talent is not displayed for its own sake, but in service of engaging the viewer in psychologically challenging content that has the potential to bring us to a greater understanding of ourselves or those around us.

In Feit Covey’s … Porcupine Girl series the artist has created the sexually charged image of an enigmatic figure with quills along her spine. The tormented Porcupine Girl (standing)... has obvious violent and sexual overtones without an explicit narrative. At times the figure crouches , vulnerable and defensive, as in Porcupine Girl (quills off) . In another variation the artist cut several different blocks intended to be seen in concert,...a figure with outstretched arms in a crucifix-like pose, reminiscent of the tormented figure of the Christ in Grunewald’s famous Isenheim altarpiece in Colmar.

Eric Denker, Curator of Prints and Drawings , Corcoran Gallery of Art 2003, National Gallery of Art

From the replication of the printmaking process to the carving of the printed block, Feit Covey’s works attend to personal analogies of physical and emotional fortitude; through the manipulation of absence and presence, lightness and darkness, the artist evokes a darker psychological sensibility within complex figural relationships.

While Feit Covey’s work is rooted in the specific artistic and cultural references of her own upbringing, the penetrating specificity of human feeling as expressed by her narratives has allowed her to connect to new generations. Environmental concerns, collective guilt, and women’s narratives are as relevant today as ever, and Feit Covey’s commitment to evolving her material practice means that she is ready to engage with the increasing complexity of the world. While circumstances change, human experience is constant; this notion is at the heart of Feit Covey’s technically masterful, emotionally provocative, and ever-evolving experimental artistic process.

Rosemary Feit Covey was born in Johannesburg, South Africa. She is an experimental printmaker, who works primarily with wood engraving. Covey is a prolific, award-winning artist who maintains a working studio at the Torpedo Factory in Alexandria, Virginia. Solo museum exhibitions have included the Butler Museum of American Art, The Delaware Center for Contemporary Arts and the International Museum of Surgical Science in Chicago. In 2014, a retrospective of her, prints, paintings, and installation work was featured at John Hopkins University’s Evergreen Museum. From 2007 to 2008, Covey served as Artist-in-Residence at Georgetown University Medical Center. She has exhibited world wide, including Buenos Aires, Geneva, and with the British Wood Engraving Society in England. Articles on her work have been featured in publications including Art in America, Juxtapoz, and American Artist Magazine.

ARTIST'S CONTACT

STUDIO 224

105 North Union Street

Alexandria, VA 22314

703-346-6918

rosemaryfcovey@gmail.com

rosemaryfeitcovey.com

rosemary@rosemaryfeitcovey

Morton Fine Art 52 O Street NW, Unit 302 Washington, DC 20001

202-628-2787

mortonfineart.com