CentralPathArt

ThorCatteau a1,BenjaminGlancy a2,AllenHolder a3∗ ,AngelaMilkowski a4 , AlexaRenner a5,ConnorTasik a6,andRebeccaTesta a7

a DepartmentofMathematics,Rose-HulmanInstituteofTechnology, TerreHaute,IN,USA

1 catteae@rose-hulman.edu, 2 glancybc@rose-hulman.edu

3 holder@rose-hulman.edu, 4 milkowaj@rose-hulman.edu

5 renneram@rose-hulman.edu, 6 tasikca@rose-hulman.edu

7 testarl@rose-hulman.edu

∗Correspondingauthor

September17,2025

Abstract

Thecentralpathrevolutionizedthestudyofoptimizationinthe1980s and1990sduetoitsfavorableconvergenceproperties,andassuch,ithas beeninvestigatedanalytically,algorithmically,andcomputationally.Past pursuitshaveprimarilyfocusedonlinkingiterativeapproximationalgorithmstothecentralpathinthedesignofefficientalgorithmstosolve large,andsometimesnovel,optimizationproblems.Thisalgorithmicintenthasmeantthatthecentralpathhasrarelybeencelebratedasan aestheticentityinlowdimensions,withtheonlymeagerexceptionsbeing illustrativeexamplesintextbooks.Weundertakethislowdimensional investigationandillustratetheartisticuseofthecentralpathtocreate aesthetictilingsandflower-likeconstructsintwoandthreedimensions, anendeavorthatcombinesmathematicalrigorandartisticsensibilities. Theresultisafancifulandenticingcollectionofpatternsthat,beyond computergeneratedimages,supportsmath-aestheticdesignsfornovelties andmuseum-qualitypiecesofart.

Keywords: Optimization,CentralPath,MathematicalArt

1HistoricalBasisandMotivation

Theconceptsofananalyticcenterandaninteriorpointalgorithmbeganwith FrischandHuardattheinceptionofthemodernageofoptimizationandoperationsresearch[6,12,13],seealsotheoriginalworkofDikin[3]andFiacco andMcCormick[4].Thesepioneeringarticlesmotivatedtheideaofiterating

throughpointsinteriortothefeasibleregiontowardanoptimalsolution,which differedfromtheprevailingvertexapproachofthesimplexmethod.However, thesimplexalgorithmleftopenthequestionofwhetherornottheclassoflinear programmingproblemswassolvableinpolynomialtime[18].LeonidKhachiyan famouslyansweredthisquestionin1979bypresentingapolynomialtimealgorithmforlinearprograms[17],butKhachiyan’salgorithmprovedimpractical andthesimplexmethodcontinuedtoprevailuntilNarendraKarmarkarintroducedamoresuccessfulpolynomialtimealgorithmin1984[15,16].Although notobviousatthetimeoftheirpublications,thealgorithmsofbothKhachiyan andKarmarkarwereinterior-pointmethodsrelatedtotheoriginalworksof Huard,Dikin,andFiaccoandMcCormick,aconnectionthatwasnoticedsoon thereafterin[7].ThepracticalandmathematicalsuccessofKarmarkar’salgorithmmarkedtheadventofinterior-pointmethods,anditledtothousands uponthousandsofpublicationsthathaverevolutionizedthefieldofoptimization[5,27,28].Anoverridingconclusionfromthisliteratureisthatefficient andefficacioussolutionprocedurestoawideclassofsalientproblemsrelyon thefavorableconvergencepropertiesofthecentralpath,andhence,thecentralpathisoneofthemostimportantmathematicalentitiesofthetwentieth century.

Thecentralpathisaparametrizationofthepositiverealhalf-lineina convexset,andeachelementofthepathisananalyticcenter.Thepertinenceofthecentralpathtoeffectivealgorithmdesignhaspromptednumerous mathematicalstudiestounderstanditsanalytic,geometric,andtopological properties.Sonnevendundertookmanyoftheoriginalstudies[23,24],see also[14],butthemathematicalpursuitscontinuedfordecadesasbrieflyillustratedby[1,2,9,11,19,20,26].Wereferreaderstosee[25]forasuccinct historicalreviewofinteriorpointmethods.

Ourmotivationtocreateartwiththecentralpathstemsfromitsmathematicalandcomputationalproperties,whichagain,haverevolutionizedthe fieldofoptimization.Manyhavegeneratedpathsinlowdimensionstolimn thebehaviorofinterior-pointmethods,andindoingso,theyhavecertainly founditeasy,ifnotalluring,tobecaptivatedbyanesotericandquizzicalelegance.Weleveragethiselegancetocreateaestheticimagesintwoandthree dimensions,andweusetheseimagestocreateartisticwallhangings,worksof stainedglass,backpacktags,beveragecoasters,holidayornaments,andthreedimensionalsculptures.Acontinuedpursuitistoassemblethree-dimensional sculpturesintoanoptimizationgardenfullof(random)interiorbouquetsthat danceandsparkle.

WestraightforwardlyintroducethecentralpathanditsconvergenceanalysisinSections2and3sothatitisreasonablyaccessibletoundergraduates, althoughmanywillrequiremodesteducationaladditions.Forinstance,fewundergraduateshavededicatedcourseworkinoptimizationand/orconvexanalysis, andstandardcoursesinrealanalysisoftenforgotheImplicitFunctionTheorem. Weemploysuchresultsandexpectreaderstoundertakebriefstudiesasneeded. Wealsoencouragetheuseofthe MathematicalProgrammingGlossary toclarify definitions[22].

Wepresenttwo-andthree-dimensionalworksofartinSections4.1and4.2. Ourprojectsseparateintotwocategories,onebasedontilingsof k-gonsand anotherbasedonfloralfacsimiles,e.g.daisies,thistles,tulips,roses,andtrumpetflowers.Themajorityofourworktodatestemsfromcentralpathsin two-dimensions,butwealsodemonstratetheuseofPlatonicsolids.Someof ourdesignshavemotivatednewmathematicalrelationships—sothequestto createarthasleadtoabitofnewmathematics.WeconcludeinSection5with asuccinctreviewandadiscussionofourfuturegoals.

2TheAnalyticCentralPath

Thespecificmodelfromwhichweproceedisimportantbecausethecentral pathdependsonthealgebraicdescriptionofanoptimizationproblemandnot directlyonitsgeometry,afactfirstrecognizedbySonnevend[23]andthen analyzedin[1].Weassumethat

istwicesmooth,that ∇G(x) hasfullcolumnrank,andthateachcomponent functionisconvex.Theassumedconvexityofeach gi(x) ensuresthat

x ∶ G(x) ≤ 0}

isconvex.Wefurtherassumethatthissetiscompactandthatitsstrictinterior isnonempty,i.e. {x ∣ G(x) < 0} ≠ ∅.Theassumptionofcompactnessisatypical butaptforourpurposes.Ourmathematicalmodelis

with c ∈ Rn definingalineartermintheobjectivefunctionand µ beinga positiveparameter.Theobjectivefunctionmapsintotheextendedreals, R = R ∪ {−∞, ∞},withtheobjectivevaluebeing −∞ ifsome si = 0. Ourfirstresultshowsthat(1)iswell-posed.

Theorem1. Theoptimizationproblemin (1) iswell-posedfor µ > 0 underthe statedassumptionsof G

Proof. Wehavefeasibilitybyassumption,andtheobjectivefunctioniscontinuousoverthestrictinteriorofthefeasibleregion.Moreover,if (xk,sk) → (ˆ x, ˆ s) isaconvergentsequenceoffeasibleelements,then

limsup k→∞ (c T x k + µ m ∑ i=1 ln(s k i )) ≤ (c T ˆ x + µ m ∑ i=1 ln(ˆ si)) 3

Thisinequalityfollowsifˆ s > 0becausetheobjectivefunctionisthencontinuousat (ˆ x, ˆ s),andconsequently,thelimitsupremumisfiniteandwesatisfythe inequalityasanequality.Ifˆ si = 0forsome i,thenanysubsequenceof (xk,sk), say (xkj ,skj ),satisfies s kj i → 0as j → ∞,andhence,theleft-handsideis −∞, whichmatchestheright-handinthiscase.Weconcludethattheobjectiveisuppersemicontinuous,whichestablishestheresultbecauseuppersemicontinuous functionsattaintheirmaximumsovercompactsets.

Weassumefornotationalconveniencethatcapitalizedvectorsrepresentdiagonalmatriceswhosemaindiagonalsaretheelementsofthevector,soif x is an n-vector,then X isan n × n diagonalmatrixsuchthat Xii = xi.Wefurther use A ≻ 0(A ≺ 0)and A ⪰ 0(A ⪯ 0)toindicaterespectivelythat A iseither positive(negative)definiteorpositive(negative)semidefinite.Letting f (x,s) betheobjectivefunctionin(1),wehavewiththesenotationalconventionsthat theHessianof f (x,s) atastrictlyfeasiblepoint (x,s) satisfies

Sotheobjectivefunctionisconcaveoverthestrictinteriorofthefeasibleset.If anycomponentof s1 or s2 iszeroforthefeasibleelements (x1 ,s1 ) and (x2 ,s2 ), thenwealsohave

) + θf (x 2 ,s 2 ) = −∞.

Sotheobjectivefunctionisconcave,andsubsequently,theoptimizationproblem in(1)isconvex.

TheLagrangianof(1)is L(x,s,y,σ

andtheconvexityoftheproblemmeansthatthefirst-orderLagrangeconditions arebothnecessaryandsufficientforoptimality.So (x,s) isoptimalifandonly ifthereare m-vectors y and σ sothat,

and

≥

, with e beingthevectorofonesandlengthbeingdecidedbythecontextofits use.Notethat s haspositivecomponentsinanoptimalsolution,andhence, weknowthat s > 0, σ ≥ 0,and σT s = 0,fromwhichwegainthat σ = 0.Also notethat µS 1 e y = 0ensuresthat y > 0because µ > 0.Soifwere-express µS 1 e y = 0as Sy µe = 0,thenthenecessaryandsufficientconditionsreduce

to,

Wedefine F tobe

∇G(x)T y c = 0,y > 0, G(x) + s = 0,s > 0, and Sy µe = 0

∇G(x)T y c G(x) + s Sy µe ⎞ ⎟ ⎟ ⎠ ,

sothatthenecessaryandsufficientconditionsfor µ > 0aresuccinctly,

F (x,s,y,µ) = 0and (s,y) > 0. (3)

Wenowhave ∇x,s,y F (x,s,y,µ) =

, andwearguethatthismatrixisinvertible,fromwhichwegainthat x and s areanalyticfunctionsof µ fromtheImplicitFunctionTheorem.

Lemma1. Assumethat Q and D are n × n matricesandthat B isan m × n matrix.Furtherassumethat Q ⪰ 0, D ≻ 0,andthat B hasfullcolumnrank. Then

isnonsingular.

Proof. Observethat

reducesto

(Q + BT DB) w = 0.

Thepropertiesof Q, B,and D ensurethat Q + BT DB ≻ 0,fromwhichwe concludethat w,andsubsequently u,arebothzero.

Theorem2. Thereisauniquesolutionto (1) foreach µ > 0,say x(µ), s(µ) and y(µ),allofwhicharetwice-smoothfunctionsof µ.

Proof. Wefirstobservethat ⎡ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎣ m

u v w

=

⎜

0 0 0 ⎞ ⎟

gives v = −∇G(x)u and Yv+Sw = 0.Sowecanreplacethebottomtwoequalities with

Sothesystemreducesto

Weknowthat

becauseeach gi(x) istwicesmoothandconvex,andhence,eachHessiansatisfies ∇2 gi(x) ⪰ 0.Lemma1nowensuresthatthematrixin(4)isnonsingularwith

So u and w arezero,andsubsequently,sois v.Weconcludethat ∇x,s F (x,s,µ) isnonsingular,andtheresultfollowsfromtheImplicitFunctionTheorem.

Wecommentthatthefunctions x(µ), s(µ),and y(µ) inherittheanalytic propertiesof G(x) fromtheImplicitFunctionTheorem.Sothesefunctionsare, forinstance,analyticinthecommonsituationthatthecomponentfunctionsof G(x) areanalytic.Wenotefurtherthat x, s,and y alsodependonthedata thatdefines G(x) and c.Soif G(x) istheaffinetransformation G(x) = Ax b, then x, s,and y dependon µ aswellasthetriple (A,b,c),afactthatleadsto additionalanalyses,see[10,23].

Ourartisticgoalspromptustodefinethecentralpathas

P(G(x),c) = {x(µ) ∶ µ > 0} , which,somewhatoddly,lacksanexplicitdependenceon s(µ) and/or y(µ).The elementsof s areslackvariablesinthelanguageofoptimization,andwehave includedthemtosimplifyourcalculations.Theelementsof y areLagrange,

ordual,variablesinoptimization,andtheygiveusawaytodefineoptimality conditionsalgebraically.Explicitlyincluding s or y aspartofthecentralpath placesusindimensionsbeyondvisualappeal,andforthisreason,ourdefinition projects {(x(µ),s(µ),y(µ)) ∶ µ > 0} ontoits x-components.Wecreateartby controlling G(x) and c,witheachchoicerenderinga‘brushstroke’intwoorthree dimensions.Wethenassemblethesebrushstrokesintoaestheticensembles.

3ConvergenceAnalysis

Wemostcommonlyusetheaffinemap G(x) = Ax b eventhoughsomeofour floralpiecesmorenaturallyalignwith G(x) beingaquadraticform.However, inthesecasesweshowthatanaffinemapstillsuffices,andhence,themajority, andindeedallbutone,ofourmodelsusesanaffinemapcomputationally.The onlycomputationalquadraticcaseisoneinwhichwecanexplicitlystatethe centralpath.Otherwisetheaffinemapcombineswithourassumptionofa boundedfeasibleregiontogivecentralpathsinpolytopes,anoutcomethat supportsameaningfulandinsightfulconvergenceanalysis.Wespecificallyshow that x(µ) convergesas µ ↑ ∞ andas µ ↓ 0,andmoreover,thattheselimits solveoptimizationproblemsthatdistinguishthemasanalyticcenters.Our presentationisnotnewandisfound,forinstance,in[21].

Wenowassumethat G(x) = Ax b,fromwhichwehavethatthenecessary andsufficientconditionsin(2)become

Ax + s = b,AT y = c,Sy = µe,y > 0,s > 0 (5)

Wefirstestablishthatsolutionstothissystemareboundedif sT y isbounded.

Theorem3. Theset

B = {(x,y,s) ∶ Ax + s = b,AT y =

M } isboundedforany M > 0

Proof. Select M > 0and (ˆ x, ˆ y, ˆ s) ∈ B.Wethenhaveforanyother (x,y,s) ∈ B thatˆ s s ∈ col(A) andˆ y y ∈ null(AT ),andhence,

Soforanyindex i,wehave

andsubsequently,

Ananalogousargumentshowsthatforanyindex i,

whichcompletestheproofbecausewealsoknowthat x isboundedbyassumption.

Wehavethefollowingcorollaryfromthefactthat Sy = µe implies sT y = mµ.

Corollary1. If µk ↓ 0,thenthesolutionsto (5) arebounded.

Wenowshowthat x(µ) convergesas µ ↓ 0andas µ ↑ ∞,withtheformer limitsolvingthelinearprogram, max{c T x ∶ Ax + s = b,s ≥ 0}

Thefactthatwecansolvealinearoptimizationproblembyfollowingthecentral pathas µ ↓ 0isthehistoricalreasonforthepath’simportance,andinparticular, followingthecentralpathtoasolutionleadstopolynomialtimealgorithms.Our artisticpursuitsdonotrelyonthishistoricalimportance,buttheconvergence propertieshelpusunderstandthe‘starting’and‘ending’pointsofthepaths usedtocreateimages.Bothlimitsareanalyticcenters.

Ourargumentsrelyontheconceptofasupportset,whichforvector v is

(v) = {i

0}.

Sothesupportsetof v isanindexsetcontainingthelocationsatwhich v is non-zero.Weextendthisnotationintwoways.First,thecomplementof σ(v) is ¬σ(v) = {1, 2,...,n} ∖ σ(v) undertheassumptionthat v isoflength n.Second, vσ(v) isthesubvectorof v containingonlythenon-zeroelementsof v (withorder preserved),andsimilarly, v¬σ(v) isavectorofzeros.

Theorem4. Thefollowinglimitsexist,

and

andthefirstofthesesolves max{cT x ∶ Ax + s = b,s ≥ 0}.Wefurtherhavethat (x∗,s∗) istheuniquesolutionto max ⎧ ⎪ ⎪ ⎨ ⎪ ⎪ ⎩ ∑ i∈σ(s

T

⎫ ⎪ ⎪ ⎬ ⎪ ⎪ ⎭ , (6) andthat (xc,sc) istheuniquesolutionto max { m ∑ i=1 ln(si) ∶ Ax + s = b,s > 0} (7)

c T

Proof. Assume µk ↓ 0andset (xk,yk,sk) = (x(µk),y(µk),s(µk)).ThissequenceisboundedbyCorollary1,andhence,ithasaclusterpoint,say (x∗,y∗,s∗) Withoutlossofgenerality,weassume (xk,yk,sk) → (x∗,y∗,s∗) as k → ∞.We havefromthefactthat (xk,yk,sk) satisfies(5)that

Ax∗ + s ∗ = b,AT y ∗ = c,s ∗ ≥ 0,y ∗ ≥ 0, and (s ∗)T x ∗ = 0

Thesearethenecessaryandsufficientconditionsshowingthat (x∗,s∗) and y∗ respectivelysolve

max{c T x ∶ Ax + s = b,s ≥ 0} andmin{bT y ∶ AT y = c,y ≥ 0} (8)

Noticethat sk s∗ ∈ col(A) and yk y∗ ∈ null(AT ),andhence,fromthefact that sk i yk i = µk foranyindex i,wehave

= (s k s ∗)T (y k y ∗)

(s k)T y k (s ∗)T y k (s k)T y ∗ + (s ∗)T y ∗

mµ k (s ∗)T y k (s k)T y ∗

Wesubsequentlyhave

i yk i ,

fromwhichwegainthat σ(s∗) and σ(y∗) partition {1, 2,...,m}.So (x∗,y∗,s∗) isastrictlycomplementarysolutiontotheprimal-dualpairin(8),fromwhich weknowthatif (x, y, s) isanoptimalsolutionto(8),thenweareguaranteed tohave σ(s) ⊆ σ(s∗) and σ(y) ⊆ σ(y∗).

Toseethat (x∗,s∗) uniquelysolves(6),let (x, y, s) beanarbitraryoptimal solutionto(8).Thenananalogousargumenttothataboveshowsthat

(y∗ ) yi yk i ,

andthearithmetic-geometricmeaninequalitygives

(

i∈σ(s∗ ) si sk i + ∑ i∈

Onechoicefor¯ y is y∗,andinthiscasewehave

Soas µk ↓ 0,wefindthat (x∗,s∗) solves

whichmeansthatitalsosolves

Theassumedfullcolumnrankof A ensuresthat x and s areinaone-to-one relationship,andspecifically, x = (AT A) 1 AT (b s) isthesameas Ax + s = b.

Moreover,theconstraint s¬σ(s∗ ) = 0meansthatthesevariablesarefixed,and hence, x isinaone-to-onerelationshipwith sσ(s∗ ).Thismeansthat s∗ σ(s∗ ) solves

TheHessianoftheobjectivefunctionis S 2 σ(s∗ ) ≺ 0.Sotheobjectivefunctionis strictlyconcaveandthesolutionisunique.Weconsequentlyhavethat (x∗,s∗) solves(6).

Nowassume µk ↑ ∞ andagainset (xk,yk,sk) = (x(µk),y(µk),s(µk)).The sequence (xk,sk) isinacompactfeasibleregionbyassumption,andittherefore hasaclusterpoint,say (xc,sc).Weassumewithoutlossofgeneralitythat (xk,sk) → (xc,sc) isaconvergentsubsequenceas k → ∞.Let (x, y, s) befeasible tothelinearprogramsin(8).Then sk s ∈ col(A) and yk y ∈ null(AT ),and similartotheorthogonalargumentsabove,wehave

Notethat sk i yk i = µk,so sk beingboundedforces yk i → ∞ as k → ∞.Wenow havethatas k → ∞,

andthearithmetic-geometricmeaninequalitygives,

So (xc,sc) solves,

anditthusalsosolves,

Weexpressthisproblemuniquelyintermsof s usingthefullcolumnrank assumptionof A,resultingin

TheHessianoftheobjectivefunctionis S 2 ≺ 0,fromwhichweknowthat (xc,sc) istheuniquesolutionto(7).Soallconvergentsubsequencesof (x(µk),s(µk)) convergeto (xc,sc),andhence, (x(µk),s(µk)) convergesto (xc,sc)

Theorem4guaranteesthattheclosureofthecentralpathis

P(G(x),c) = P(G(x),c) ∪ {x c ,x ∗},

andweassumecomputationallythatpathsstartat xc,whichwillbethezero vectorbydesign,andendsat x∗,i.ethat µ startsatinfinityanddecreasesto zero.

3.1ComputingCentralPaths

Ourdescriptionofthecentralpathgivesmathematicalassurances,butwe requireacalculationmethodtogenerateimages.Thedefiningsystemwith G(x) = Ax b is F (x,s,y,µ) =

) >

WeuseNewton’smethodtoestimate x(µ), s(µ),and y(µ) fromany x, s,and y byiterativelysolving

x,s,y,µ

⎜ ⎝ ∆x ∆s ∆y ⎞ ⎟ ⎠ =

⎜ ⎝ c AT y b Ax s µe Sy ⎞ ⎟ ⎟ ⎠ = F (x,s,µ) ⎫ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎬ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ ⎭ (9) andupdating x, s,and y sothat

x ← x + α ∆x,s ← s + α ∆s, and y ← y + β ∆y.

Thestepsizes α and β guaranteenonnegativitybysettingthemto α = ω min {1, min {xi/∆xi ∶ ∆xi < 0}} and β = ω min {1, min {yi/∆yi ∶ ∆yi < 0}} , with ω beingapositivescalarthatislessthanone.Thevalueofeitherinner minimumis ∞ if∆x ≥ 0or∆y ≥ 0,respectively.

Calculating∆x,∆s,and∆y reducestosolvingan n × n positivedefinite systemtocompute∆x,fromwhichwethencalculate∆s and∆y.Wefirst noticethebottomtwoequationsofthelinearsystemin(9)give

and

Using AT ∆y = c AT y fromthefirstequationin(9)andcombiningtheselast twoimplications,wefindthat,

Ourgeometryeasilypermitsafeasiblestartingpoint (x,s),andinthiscasewe knowthat Ax + s = b with s > 0.Inthissituationwehave A∆x + ∆s = 0from thesecondequationin(9),andhence, (x + α∆x,s + α∆s) remainsfeasibleafter theupdatebecause,

Moreover,theequationdefining∆x becomes

Wehave AT S 1 YA ≻ 0becauseif v isanonzerovector,then v T AT S 1 YAv = (√S 1 YAv)T (√S 1 YAv) = ∥√S 1 YAv∥2 > 0,

with √S 1 Y beingthediagonalmatrixwithdiagonalelements √yi/si.The positivityof ∥√S 1 YAv∥ followsfromthefactthat A hasfullcolumnrank, andhence,neither Av nor √S 1 YAv arezerounless v iszero.

Solving(10)isefficientandnumericallystable,see[29,30],andoncewehave ∆x,weset,

∆s = A ∆x andand∆y = µS 1 e y S 1 Y ∆s.

Theresultisanefficientandnumericallystableiterativeprocessthatefficiently convergesto x(µ), s(µ),and y(µ).Weceaseiterationsonce max {∥F (x,s,µ)∥,α ∥∆x∥} < ε, (11) with ε beingaconvergencetolerance.

Digitallyrenderingacentralpathnecessitatesthatwecomputeasequence, say µk,alongwithestimatesfor x(µk).Wedenotetheestimatesof x(µk), s(µk),and y(µk) as xk , sk,and yk.Theinequalityin(11)ensuresthat ∥x k x(µ k)∥ = α∥∆x∥ ≤ ε.

Soweguaranteeaccuracytothecentralpathat µk bydecreasing ε,butthis assuranceleavesopentheconcernthatwecouldloseaccuracyasagraphics packageinterpolatesestimatestocreateacurve.Acommonmeasureofhow closeapoint (x,s,y) isto (

see[26],andthismeasurepromotesthatwecompute µk valuessothat

with δ beinganalloweddeviationfromthecentralpath.Astraightforward calculationshowsthatthemaximumisachievedat θ = 1/2,andweinitially devisedarecursivebisectiontechniquetoensurethat

Theprocessstartswith µ1 and µ2 beingrespectivelylargeandsmallenoughso that x1 ≈ xc and x2 ≈ x∗.Theseapproximationssatisfy(11),andiftheyalso satisfy(13),thenwearedone.Weotherwisecomputeestimates

thatsatisfy(11)andrenumbersothat

Theprocessrepeatsonall [µk,µk+1 ] intervalsuntileachsatisfies(13).

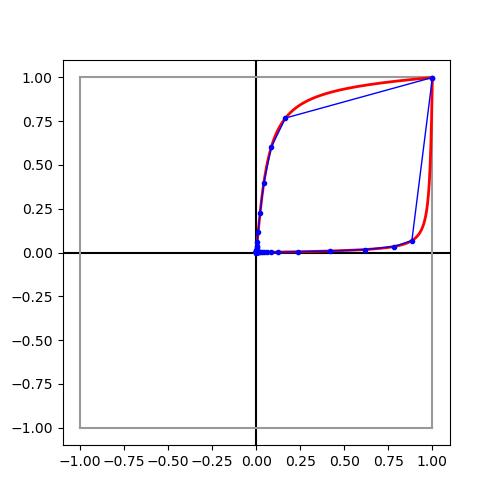

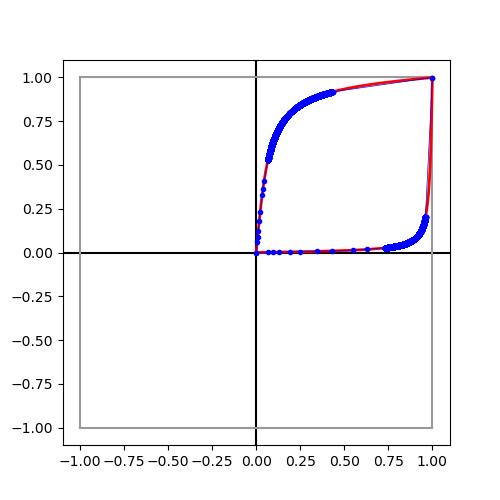

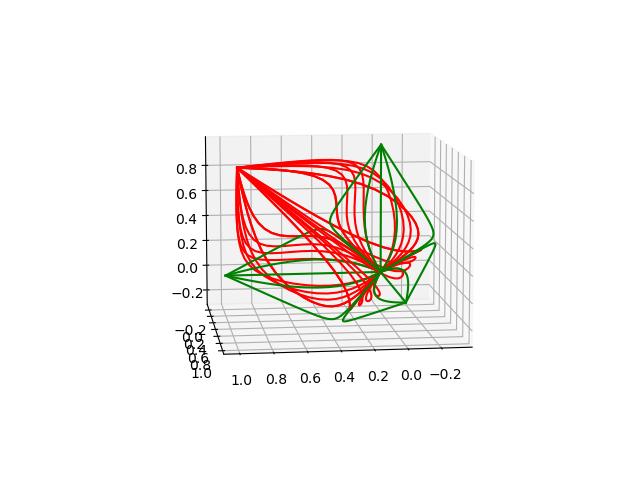

The µk listfromthebisectiontechniquewiththestandardmeasurein(12) provesproblematic.Theissueisthatourcentralpathsareapproximatedbythe primalestimates, xk,whereasthedualestimates, yk,dominatethedecisionsof whetherornottobisecttheintervals.Thecurvatureofthedualcentralpath doesnotalignwiththecurvatureoftheprimal,atleastinourgeometries,and theresultisalistof µk valuesthatoverrepresentlowcurvatureportionsofthe (primal)centralpath,seeFigure1.

Wecorrecttheoverrepresentationoflowcurvatureportionsofthecentral pathbyestimatinglinearitywithfinitedifferences.If xk , xk+1 ,and xk+2 are consecutiveestimates,then

approximatetheunittangentvectorsofthecentralpathat µk and µk+1 .So estimatesofthelinearityofthecentralpathovertheintervals [µk,µk+1 ] and

Figure1:Thefigureontheleftspaces µ with(13),andthefigureontheright spaces µ bybounding(estimates)ofcurvature.

[µk+1 ,µk+2 ] arerespectively

If κk > δ,thenweassumethecentralpathisnotsufficientlylinearover [µk,µk+1 ] andwebisectthisintervalbyinsertingthemidpointtoourlistof µk values. Thesameoccursif κk+1 > δ,butinthiscasewebisect [µk+1 ,µk+2 ]

Thebisectionmethodbasedonourcurvatureestimatesreducestheoverrepresentationofthecentralpathonlowcurvaturesegmentsandincreasesaccuracy onhighcurvatureportions.Figure1comparesthetwotechniques.Thefigure ontheleftsets δ = 0 08in(13),andtheredcentralpathsareapproximated with23and21points.Noticehowthemajorityofpointsaccumulatenearthe centerofthesquareandthatthelinearinterpolationislessaccurateasthepath convergestowardtheupperright.Thefigureontherightinsteadboundsour curvatureestimatesby0 5andresultsin8475and4208pointsrespectivelyfor thetopandbottompaths.Althoughthecurvaturetactichasmorepointsthan thebisectiontechnique,wehavethefavorableoutcomethatthepointestimates accumulateinregionsofhighercurvature.

3.2GeometricConsiderations

Affinetransformationsaidourgeometriceffort,andweestablishthatthecentral pathofatransformedproblemisthesameasthetransformationofthecentral path.Thisresultisnotunforeseenorunexpected,butitshouldnotbeassumed withoutproofbecause,aspreviouslynoted,thecentralpathdependsonthe algebraicdescriptionoftheproblemandnotonthegeometryoftheproblem.

Weillustratethisfactbyobservingthatif

then Ax ≤ e and ˆ Ax ≤ e areindividuallytrueifandonlyif 1 ≤ x1 ≤ 1and 1 ≤ x2 ≤ 1.So

However,setting G(x) = Ax b and ˆ G(x) = ˆ Ax b,wefindthat P(G(x),c) ≠ P( ˆ G(x),c),asillustratedinFigure2with cT = (1, 2).Thebasicideaisthatgeometricintuitionshoulddrawcautionbecausegeometricperspectiveiscoupled with,butdisjointfrom,algebraicexposition.

Figure2:Thesolidcentralpathignoresthedashedredundantconstraint, whereasthedashedcentralpathincludestheredundantconstraint.

Let T (x) = Bx + d beanaffinetransformationwith B beinganinvertible n × n matrix.Applying T (x) toanelementofthepolytope {x ∶ Ax ≤ b},we findthat T (x) = Bx + d = z ifandonlyif x = B 1 (z d).Thisrelationshipgives thealgebraicdescriptionoftheimagepolytopeas {z ∶ AB 1 z ≤ b + AB 1 d}.We nowprovethatcentralpathsin {x ∶ Ax ≤ b} correspondwithcentralpathsin theimagepolytope.

Theorem5. Let B beaninvertible n × n matrix,andlet T (x) = Bx + d.Set G(x) = Ax b and ˆ G(z) = AB 1 z b AB 1 d.Then

T (P(G(x),c)) = P ( ˆ G(z), (B 1 )T c)

Proof. Wefirstnotethat x(µ) ∈ P(G(x),c) ifandonlyifthereareunique s(µ) and y(µ) thatsatisfy

Ax + s = b,s ≥ 0

AT y = c,y ≥ 0 Ys = µe.

Set T (x(µ)) = z(µ) sothat x(µ) = B 1 (z(µ) d).Then z(µ) satisfies

AB 1 z + s = b + AB 1 d,s ≥ 0 (B 1 )T AT y = (B 1 )T c,y ≥ 0

Ys = µe,

whicharethenecessaryandsufficientconditionsfor z(µ) tobethe µ element of P ( ˆ G(z), (B 1 )T c)

Wecommentthattheproofisstrongerthenthetheoremstatementbecausewe haveactuallyshownthatthe µ elementof P(G(x),c) mapstothe µ element of P ( ˆ G(z), (B 1 )T c)

Theorem5illustratesamathematicalandcomputationalthemeofourwork, whichisthatwegenerateimageswithstandardgeometriesandthentranslate themtocreateaestheticimages.Ourmostcommontwo-dimensionalpolytope istheregular k-gondefinedby Gk(x) = Akx e,withthe i-throwofthe k × 2 matrix A being Ak i = (cos((i 1)2π/k), sin((i 1)2π/k)

Weusethesuperscript k onboth G and A toindicatethispolygon.Consider therotationmatrix,

R(θ) = [ cos(θ) sin(θ) sin(θ) cos(θ) ] ,

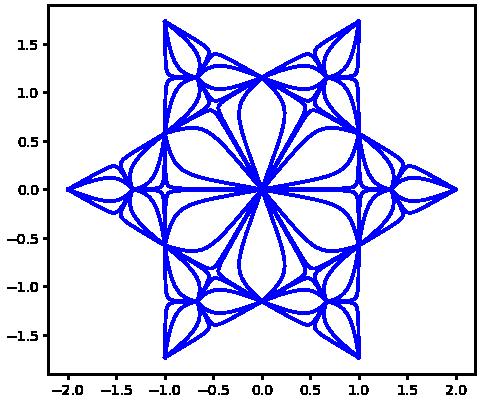

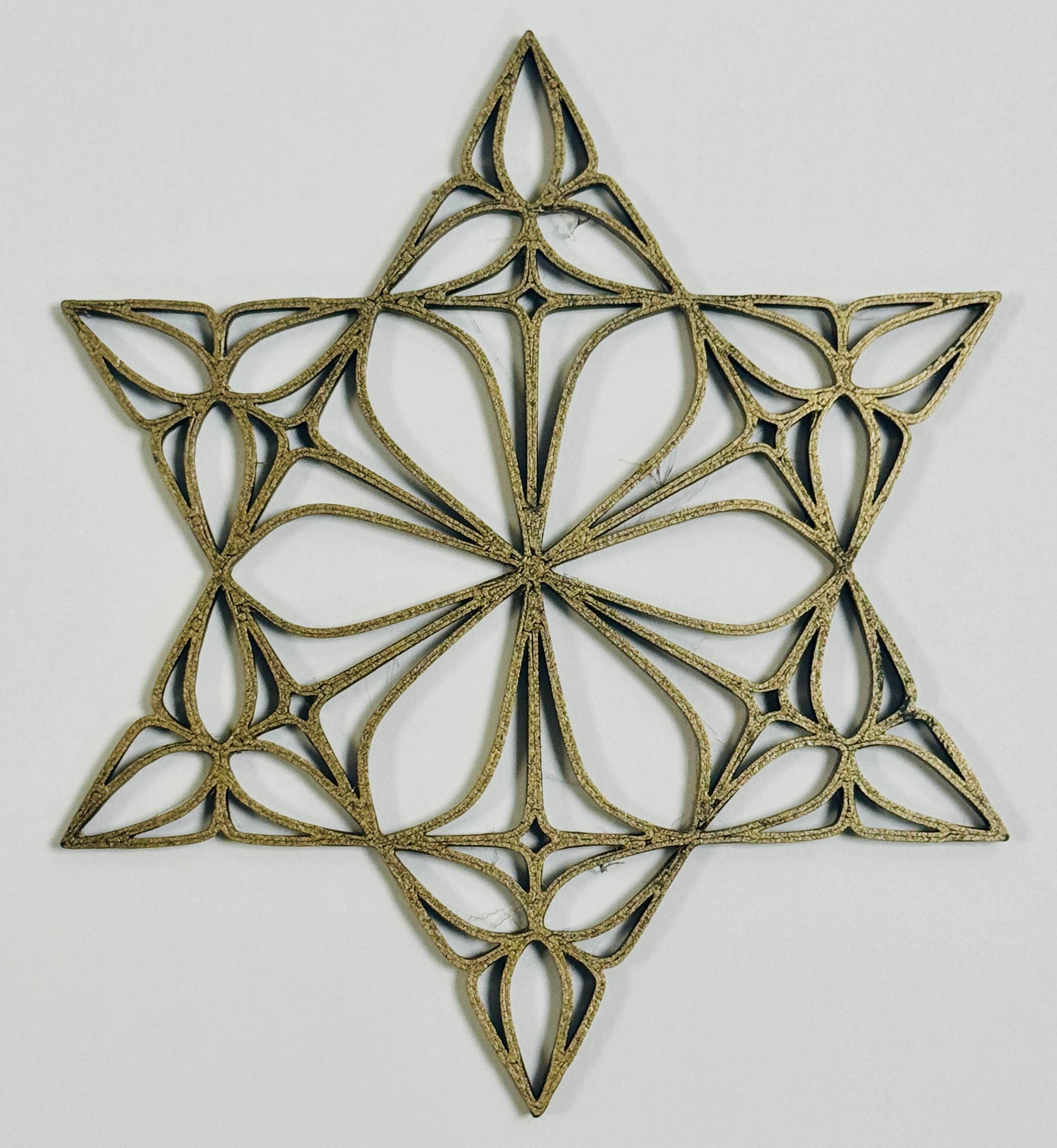

andset ci(θ) = AiR(θ),with Ai beingthe i-throwof A.Figure3adisplays P(G3 (x),ci(θ)) for i ∈ {1, 2, 3} and θ ∈ {0 009, 0 009, 0 18, 0 18},andFigure3bdisplays P(G6 (x),ci(θ)) for i ∈ {1, 2,..., 6} andthesamevaluesof θ Figure3cdisplaysastarcreatedbytranslatingthe3-gonpathsaroundthe 6-gonwiththeaffinetranslations,

R ( iπ 3 )([ 1/30 01/3 ] + ( 2 0 )) ,

with i ∈ {0, 1, 2,..., 5}.Theorem5ensuresthatthepathsundertranslationare indeedpathswithinthetranslatedpolytopes.Wecommentthattheobjects inFigure3resemble k-gonsbydesign,buttheyarenot k-gonsperseandare insteadpathswithin k-gons.

AnotheruseofTheorem5istheabilitytocreateafontfromcentralpaths. Wecreatecharactersfromcollectionsof‘strokes,’eachofwhichequateswitha translationof P(G4 (x),c),with c beingdecidedtogiveanappropriateshape. Theauthorshavetakentothemoniker“InteriArt,”andFigure4isanexample ofthistermincharactersrenderedfrom4-goncentralpaths.

WehavealreadyseeninFigure2thatdifferentdescriptionsofthesame geometrycanleadtodifferentcentralpaths,andhence,itwouldbesomewhat naturalandanalogoustoassumethatdifferentgeometries,whichwouldnecessarilyhavedifferentalgebraicdescriptions,wouldalsohavedifferentcentral

(a)Pathsina3-gon. (b)Pathsina6-gon. (c)Astarfigure. Figure3:Translationsof3-gonpathsformastararounda6-gon.

Figure4:Afontcreatedfromcentralpaths.

paths.However,thisisnotauniversaltruth,andourfinalresultshowsthatit ispossibleforcentralpathswithindifferentgeometriesanddifferentalgebraic descriptionstoequatewitheachother.Thisresultpermitsustogeneratetwodimensionalsurfacesinthreedimensionsbygeneratingasinglepathinacube andthencontinuallyrotatingitinthreedimensionstoformasurface.

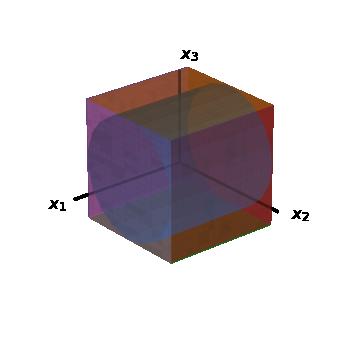

, andconsiderthegeometryinFigure5,whichassumes b1 = b2 = 1formotivationalpurposes.Thethree-dimensionalcube, {x ∶−1 ≤ xi ≤ 1,i = 1, 2, 3},is {x ∶ G1 (x) ≤ 0},andthiscubecircumscribesthethree-dimensionalcylinder, {x ∶ G2 (x) ≤ 0}.Theorem6showsthatcentralpathsoftherotatedcubeequate withcentralpathsinthecylinder.

Theorem6. Assume c = (c1 ,c2 ,c3 )T issuchthat c1 ≠ 0 andthatatleastone of c2 or c3 isnonzero,andlet R betherotationmatrixinthe x2 and x3 plane,

Figure5:Arightcircularcylindercircumscribedbyacube.

Let T (x) = Rx sothat T 1 (x) = R 1 x.Then

T 1 (P (G1 (x),T (c))) = P (G2 (x),c)

Proof. Thenecessaryandsufficientconditionsin(3)for P(G1 ,T (c)),inblock matrixform,are

[ I I ] ( y1 y2 ) = T (c), [ I I ] x + ( s1 s2 ) = ( b b ) , and Sy = µe.

Themiddleequationassertsthat s1 = b x and s2 = b + x,andsubstitutingthese intothethirdequalitygives

y1 = µ (B X) 1 e and y2 = µ (B + X) 1 e,

withboth B + X and B X beinginvertiblebecause0 < µ < ∞ ensuresthat x(µ) isstrictlyfeasible,i.e. b < x < b.Thefirstequalitynowgivesthat

µ ((B X) 1 (B + X) 1 ) e = T (c) defines P(G1 (x),T (c)).Recognizingthat

(B X) 1 (B + X) 1

= ((B X)(B + X)) 1 (B X)(B + X) ((B X) 1 (B + X) 1 )

= (B 2 X 2 ) 1 ((B + X) (B X))

= 2 (B 2 X 2 ) 1 X, wefindthattheelementsof P(G1 (x),T (c)) satisfy

2µ (B 2 X 2 ) 1 x = T (c), whichwere-expressas

X 2 T (c) + 2µx B 2 T (c) = 0 (14)

Wenowhavethattheuniquesolutionis

(

0,T (c)i = 0,

with T (c)i beingthe i-thcomponentof T (c).Fromthefactthat

wehavethattheelementsof T 1 (P(G1 (x),T (c))) are

Thenecessaryandsufficientconditionsfor P (G2 (x),c) are

Solvingthesecondequalityfor s andsubstitutingthisexpressionintothethird equalitygives

withtheinverseagainbeingguaranteedbecause0 < µ < ∞ ensuresstrictfeasibility.Substitutingthisexpressionfor y intothefirstconditiongives

Werewritetheseequationsas

Thefirstequationidentifies x1 exactlylike(14),andhence, x1 (µ) isasstated in(15).Thelasttwoequationsarecoupledquadratics,anddirectsubstitution ofthesecondandthirdcomponentsof(15)satisfytheseequations.

4ArtisticOutcomes

Wenowshowcaseseveralofourartisticprojects,butwefirstnotethatproducing qualityitemshasbeenequalto,ifnotinexcessof,ourmathematicaland computationalefforts.Everyartprojecthasbroughtchallengesandfailures, andwehavelearnedfromeachexperience.Sometimesthehasslehasbeen confrontingtechnologicallimitations,sometimesithasbeencorrectingstandard imageprocessingschemes,andsometimesithasbeentheslow,deliberate,and pedanticindustryrequiredtodomostanythingwell.Theprojectsthatfollow areillustrativeexamplesofthenumerousattemptsthatwehavemadebefore gettingthingsright.Wecatalogtheeffortassociatedwithourlargestpieceto dateintheattachedsupplement.Creatingqualityartiswork,butitisalso fulfillinganditbrandisheshowthemathematicsofoptimizationisnotonly useful,butbeautiful.

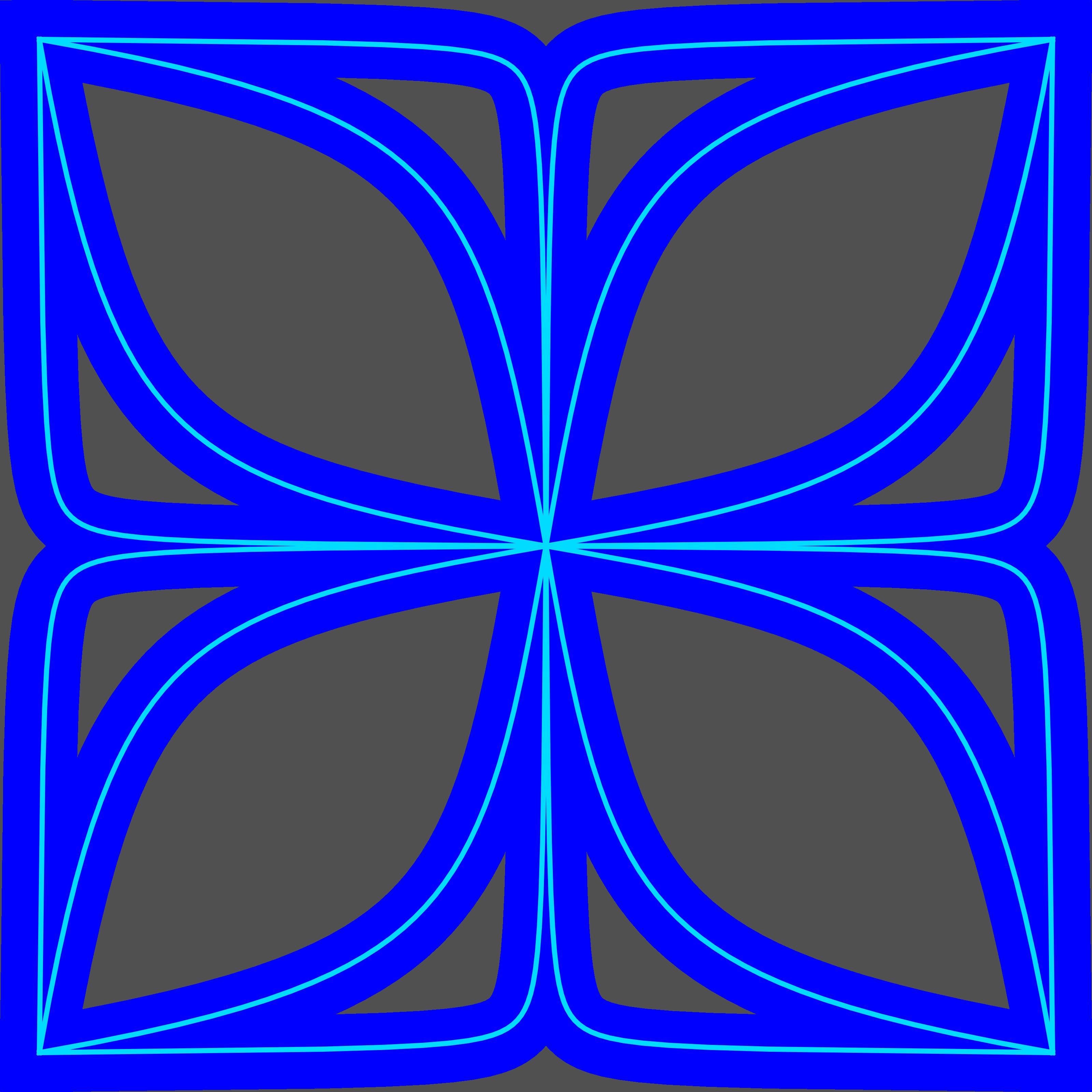

4.1Two-DimensionalArtandTilings

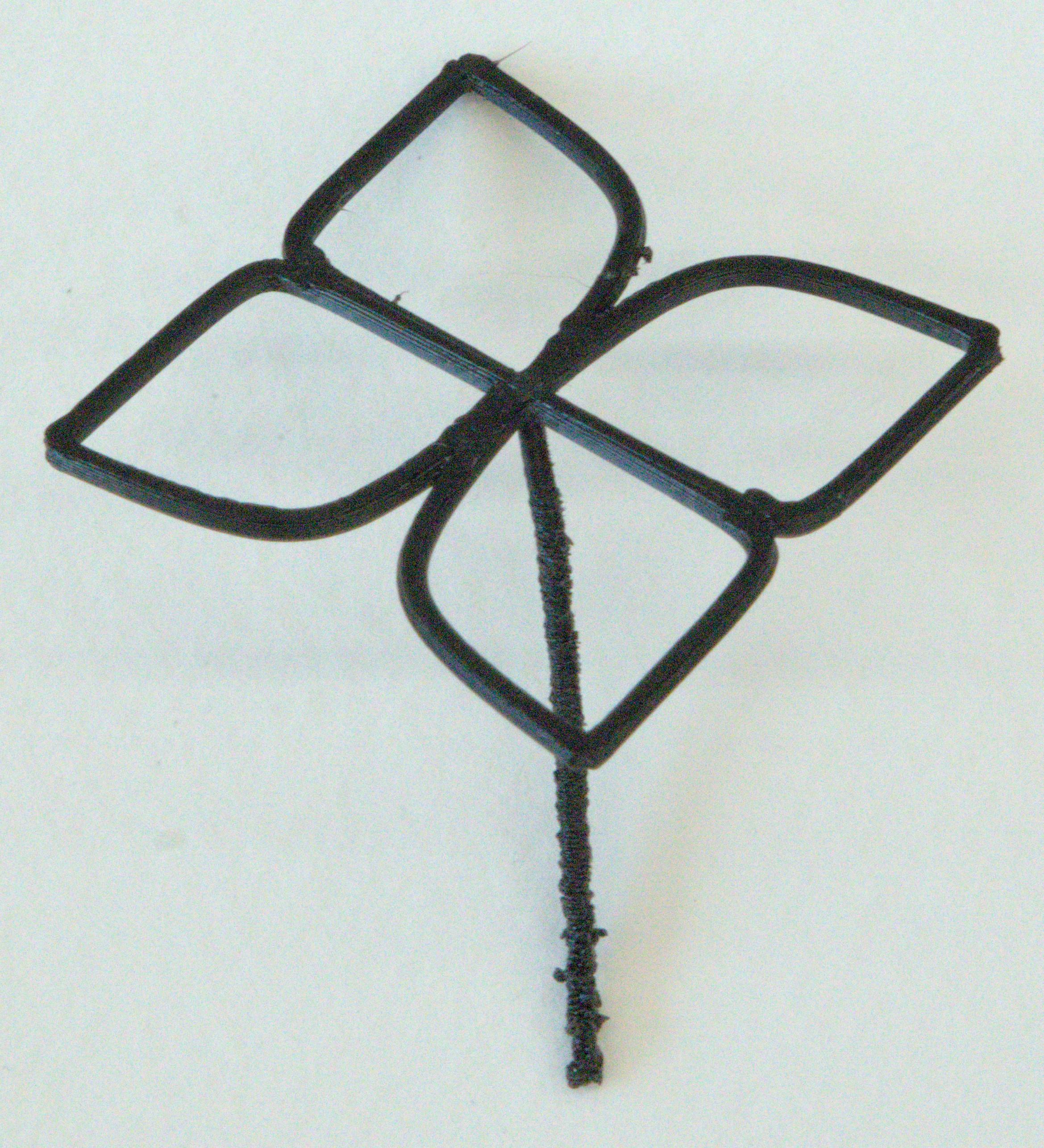

Centralpathsintwo-dimensional k-gonscombinetoformappealingpatterns usefulinavarietyofartprojects,andweusethesepatternstocreateanumber ofitems.Mostespecially,two-dimensionalpathslendthemselvestolasercutting andetchingandto3D-printing.Ourfirst3D-printhadrandompathsina4-gon, witheachpathbeing P(G4 (x),c) forarandom c,seeFigure6a.Distributional qualitiesadjustappearance,andinthiscaseweusedtwodifferentdistributions. Ifwevisuallydividetheimageintofour“leaves”fordescriptivepurposes,then eachleafcorrespondswithoneofthefourvertices.Twopathsdefineandbound eachleaf,andweuseanormaldistributiontodecidethesepaths.Let α ∼ N (η,σ2 ),andnoticethateachleafisbracketedbypathsdefinedbytworows of Ak.Thisisbecause P(G4 (x),A4 i ) isalinefromtheorigintothemidpoint ofthefacetdefinedbythesupportinghyperplane {x ∶ A4 i x = 1}.Forinstance, pathsmovingtotheupperlefthave c vectorsthatareconvexcombinationsof A4 2 = (0, 1) and A4 3 = ( 1, 0).Thepathsinthisobjecthave η = 0.0425and σ = η/3,andapairofrandomsamples,say α1 and α2 ,definethetwoouter pathsofeachleaf.Sothepathsthatdefinetheleaftotheupperlefthavethe form c T 1 = (1 α)A4 2 + αA4 3 and c T 2 = (1 α)A4 3 + αA4 2

(a) A3D-printofpathsina4-gon. (b) Abackpacktag.

Figure6:Ouroriginal3D-printoftwo-dimensionalpathsandabackpacktag fromthesameimage.

Thereisabouta0 15%chancethatoneofthesepathsispartofaneighboring leaf,whichseemstotheauthorsakintogeneratingafourleafclover.Thechance ofsuchaneventisobviouslydependentonthedistributionandit’sparameters, andtoyingwithalternativesleadstodifferentqualities.

Pathsinternaltoaleafaregeneratedwithauniformdistribution,andin thisexampleweuse β ∼ U (2η, 1 2η),with η = 0.0425asbefore.Eachleafhas threeorfourpathsinternaltotheleaf,andeachoftheseisdefinedbya c vector oftheform c T = (1 β)A4 i + βA4 j

Thisstochasticprocessofpathgenerationallowsustogeneratenumerouspatternsina k-gon,andweusethistechniqueinsomeofourprojects.

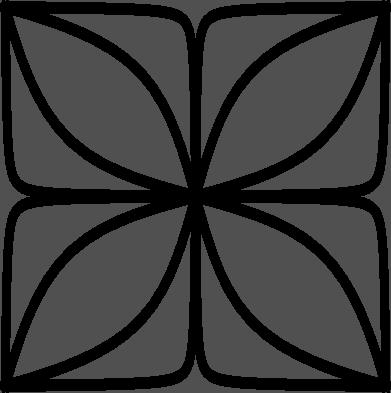

Manyofourpatternstilepathsinadjoiningpolygons,buttheresulting tilingsarenotpolygonalperse.Theyareinsteadtilingsofpathsinpolygons. Thisleavespatternsthatonlytouch,orintersect,atterminalpointsofapath. Figure7cisaversionofthePythagoreantilingandillustratesthisphenomena. ThePythagoreantilingcascadestwo4-gons,butthepieceinFigure7ciscreated bypathsinthe4-gons,makingthebordersofthe4-gonsintuitiveeventhough theyarenotthere.

EtchingsandLaserCutouts

Thetechniqueofrandompathsina4-gonextendsdirectlyto k-gons,andwe haveusedthisconcepttopromotemath,art,andengineeringtomiddleschool studentsduringRose-Hulman’s2024SoniaMathDay.Weaddedanelectrical engineeringaspectbydesigningacircuitthatallowedparticipantstoadjust parameterslike k andthenumberofpathsinaleaf,andtheygeneratedpatterns untilonestrucktheirfancy.Weetchedthesepatternsontocoloredacrylic medallionswithalasercuttertocreatebackpacktags,resultinginmementos ofachicapplicationofmathandtechnology.Abackpacktagofthepathsin Figure6aisinFigure6b.Wehavealsousedpatternsofcentralpathstoetch leathertocreatecoastersandkey-chainfobs,andwehavelaser-cutwoodtrivets,

seeFigure7.Wecontinuetoexploreotherpossibilities,andinparticular,we hopetotileglassetchingstocreateaworkofstainedglass.Anacrylicprototype isinFigure8.

(a) Anetchedleathercoaster. (b) Anetchedkey-chainfob. (c) Alaser-cutwoodtrivet.

Figure7:Artitemscreatedwithalasercutter/etcher.

Figure8:Anacrylicprototypeofastainedglasspiece.

3D-Printing

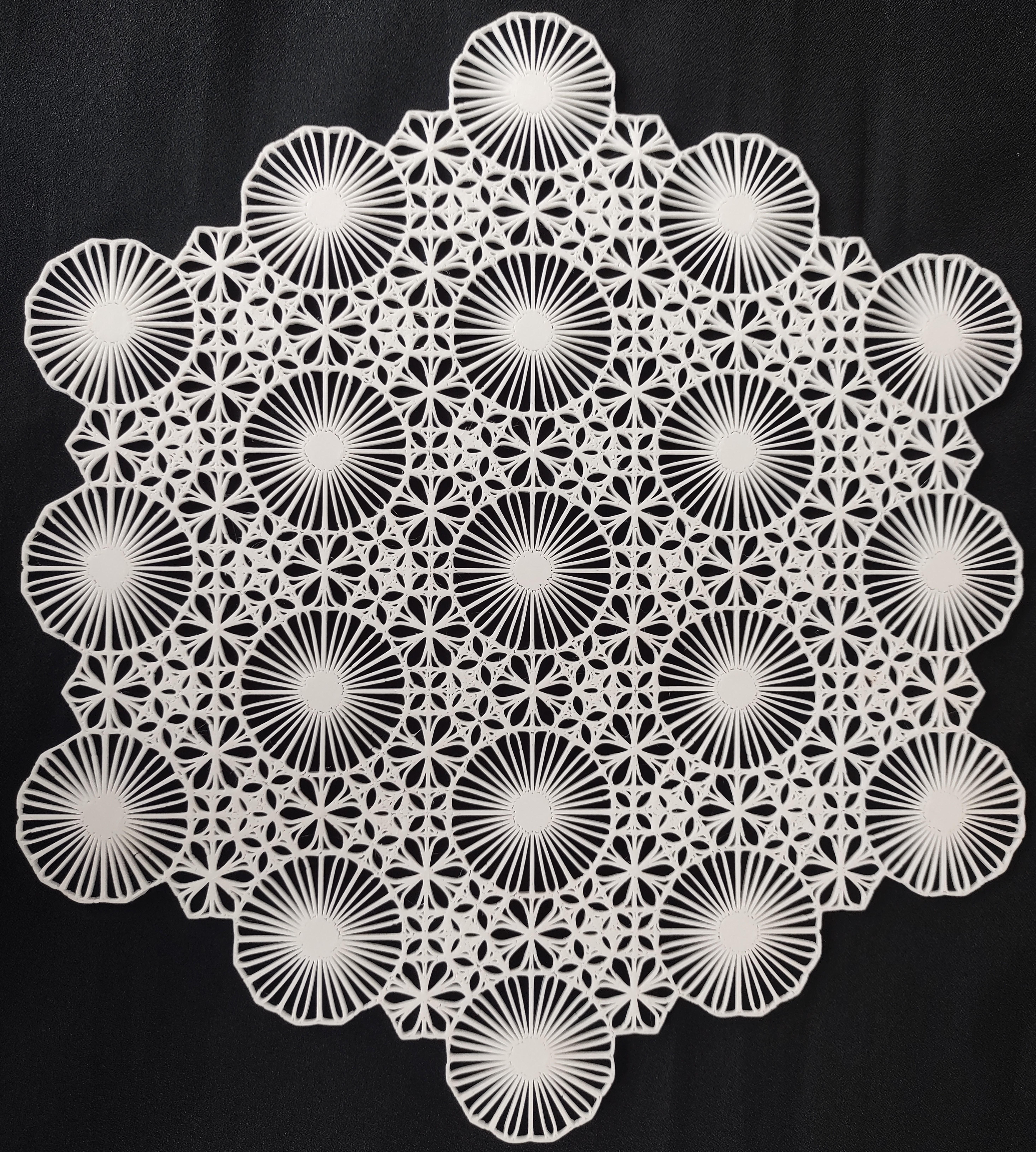

3D-printersuseseveralmodalitiestoconstructobjects,andforthemoment,we onlyconsiderthemostcommonprintingmethodofFusedDepositionModeling (FDM).FDMprintersarenotcapableofcreatingthree-dimensionalstructures withpathsin,forinstance,aPlatonicsolidbecausetheywouldrequirean impracticalnumberofstructuralsupports.However,modernFDMprintersdo provideacost-effectivewaytocreatethree-dimensionalobjectsassociatedwith two-dimensionalpatterns,whichforusaretilingsofcentralpathsfrom k-gons. Theprinteditemsareinteresting,andwehaveusedthemasholidaydecorations anddecorativetrinkets.Wehavealsoprintedandassembledrandompatterns tocreateabouquetofdaisy-andthistle-likeobjects,aprojectthatwediscuss morefullybelow.IllustrativeobjectsareinFigure9.

PrintMakingwithCyanotypeandSolarFast

Printmakingwithpatternsand/ortilingsoftwo-dimensionalcentralpathshas becomeoneofourfavoritetechniques.WeusecyanotypeandSolarFast,both ofwhicharedyesthatreactwithultravioletlighttocreatecolor,toimprint

(a) Aholidaydecoration. (b) Anintricatetiling. (c) Abouquet.

patternsonpaperandcloth.Cyanotypeonlygivesshadesofblueandisthe originalchemicalusedtomakeblueprints.SolarFastissimilarbutcomesina varietyofcolors.

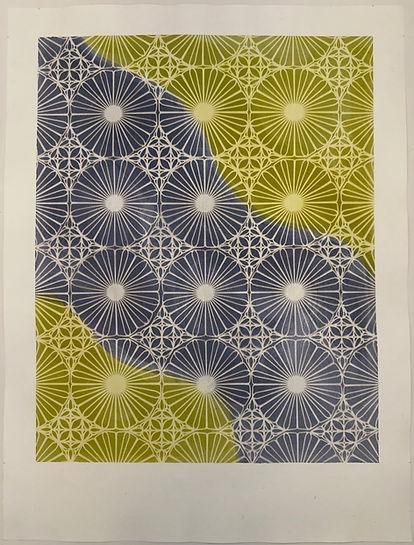

ThetechniquebeginswithadesignliketheoneinFigure9b—weusea modernandaccurateFDMprinter.Wenotethattheimageprocessingsoftware requiresspecialsettingstoensurefidelitytoourmathematicalcalculations,for otherwise,theresultisflawedwithartifactsfromaliasing.Wethenpre-stretch watercolorpapertoreducewarpingaftertheprintingprocess.Colorlessdye isthenappliedtothepaper,andthe3D-printedpatternisplacedoverthe dyedarea.Wesubsequentlyexposethepapertosunlightforseveralminutesto createcolorintheunblockedregions.Theprintisthenwashedwithaspecial soapandislefttodry.Thedryingprocessendswithimprovedflatnessifthe paperisheldinplaceasitdries.Theresultsare,atleasttotheauthors,visually stunning,seethepreviouslypublishedpiecesinFigure10asexamples1 .Apiece similartoFigure10a,butwithasolid,dark-bluebackground,isalsonowpart ofRose-Hulman’spermanentartcollection.

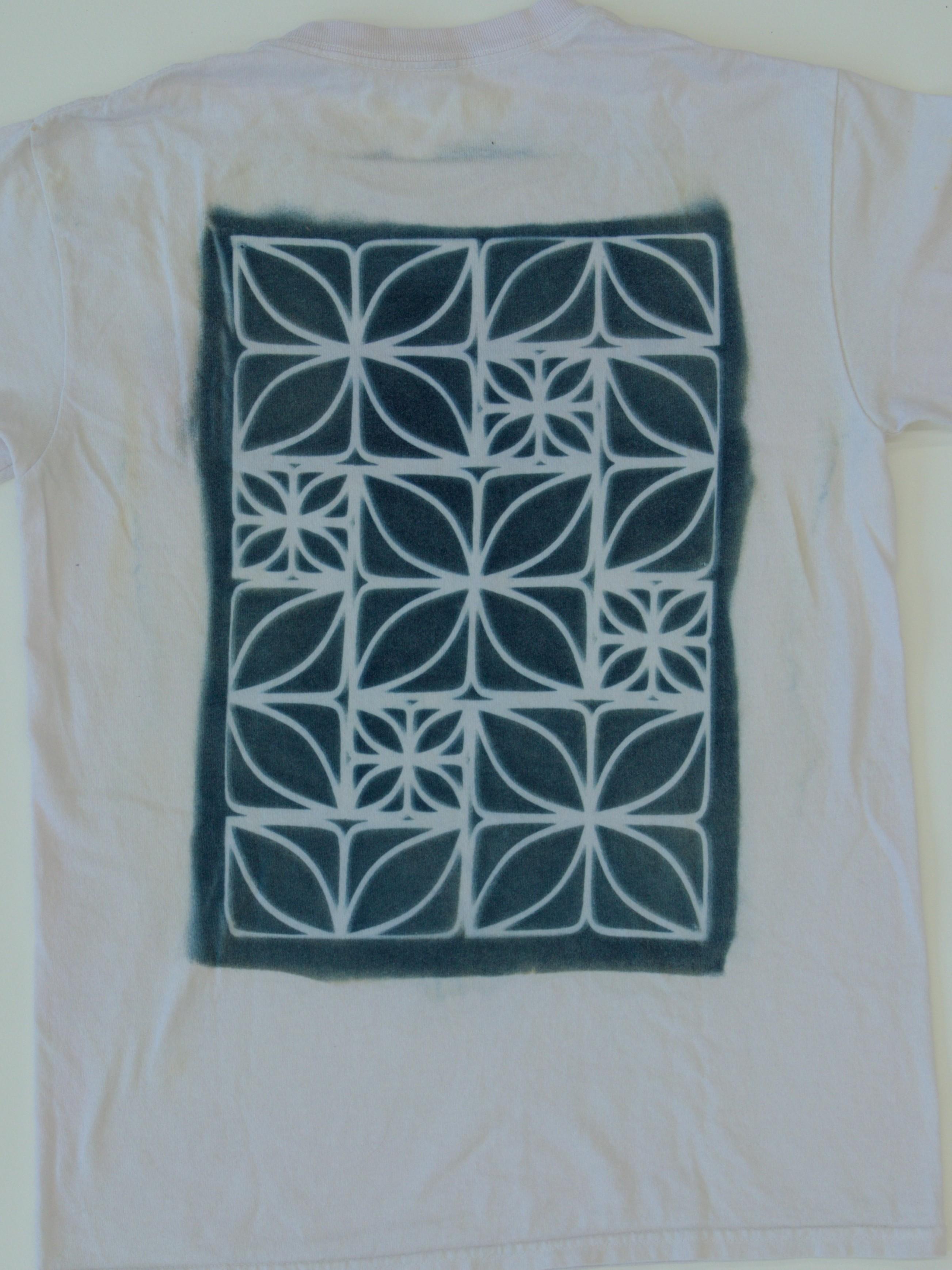

WeusedtheSolarFastprintmakingprocesstopromotemathematicsto middleschoolstudentsduringRose-Hulman’s2025SoniaMathDay.Students selectedfrompatternsafterlearningaboutcentralpaths,andtheythenapplied SolarFastDyetoa4inchby6inchpieceofwatercolorpaper.Wethenexposed andwashedtheirprints,andeveryoneleftwithauniquepieceofarttoremember theday.ThecollectionofpiecesisinFigure11a.WehavealsousedSolarFast dyetoimprintt-shirtsandotherclothitems.Thefrontandbackofat-shirtis inFigure11b.

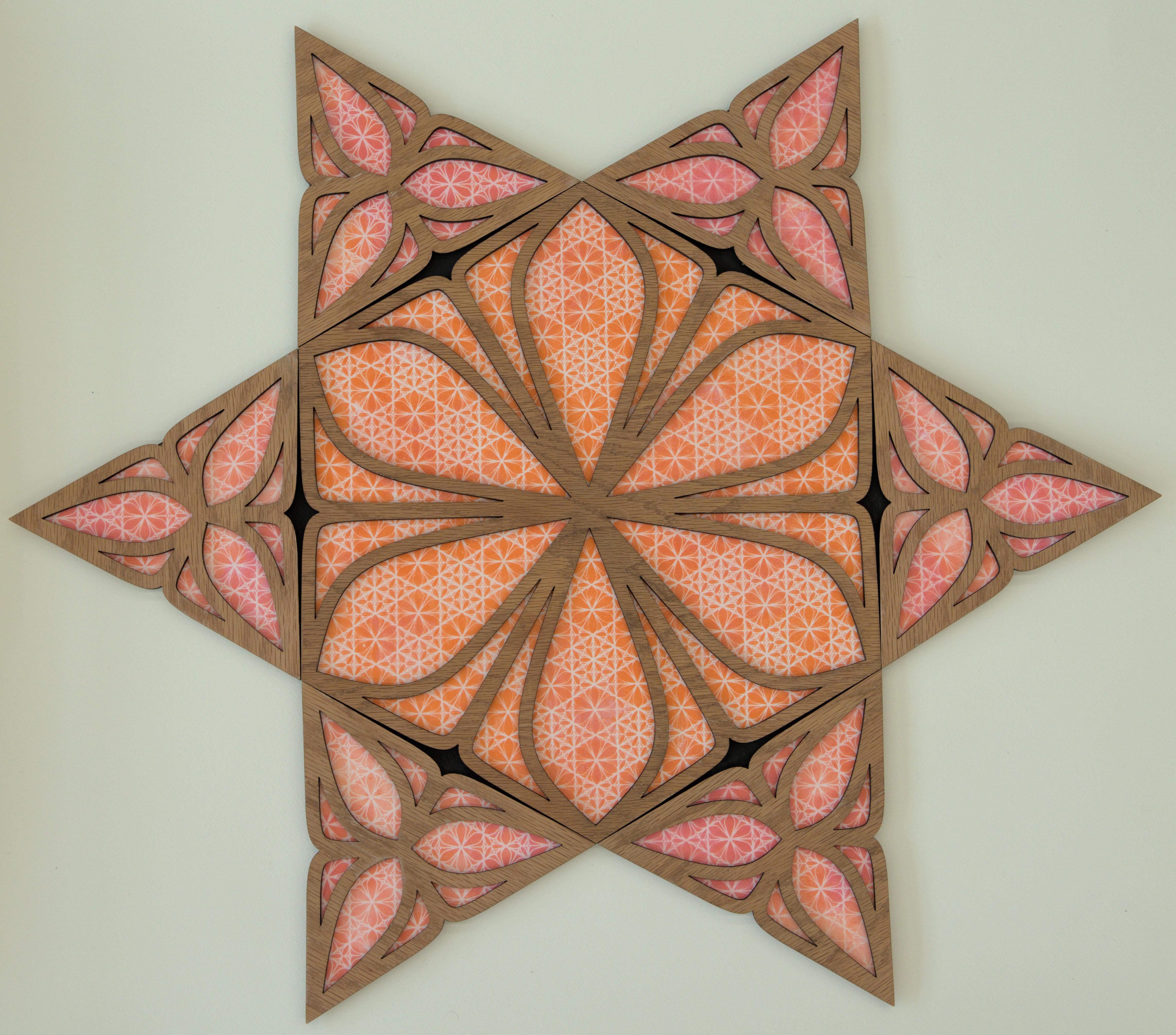

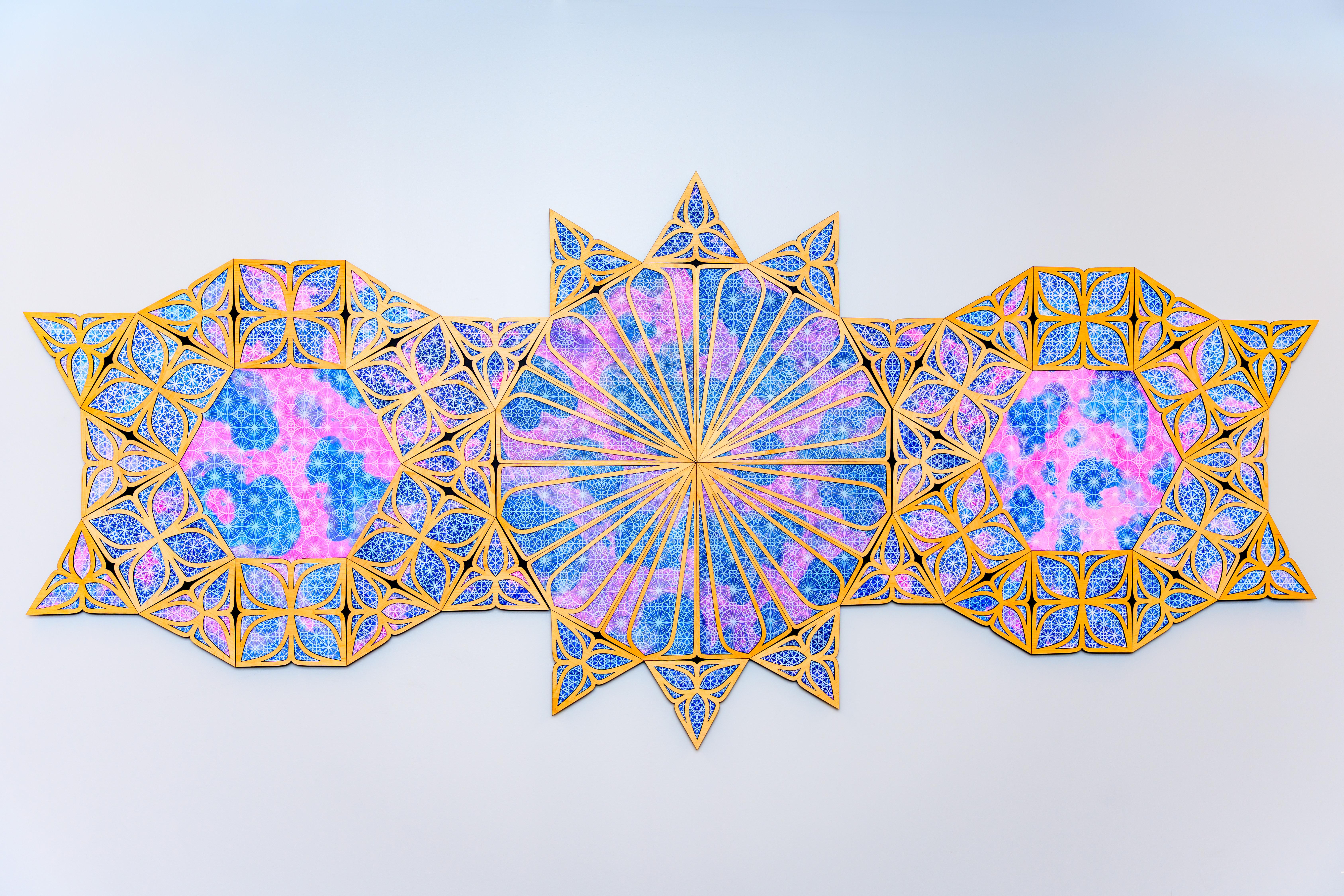

Combiningprintsandwoodcuttingselevatesthevisualeffect.Thesepieces haveaSolarFastprintbehindalaser-cutwoodpattern,renderingacollectionof “windows”throughwhichthecoloredpatternsarevisible.Twoexamplearein Figure12.ThewoodportionoftheclockinFigure12ahaspathsina12-gon, witheachleafhavingfourpaths.Thered-orangeSolarFastbackgroundofthe clockisatilingofpathsinhexagonsandtriangles.Thelargewallpiecein Figure12cisover10feetlongand4feettall.ThewoodisMapleveneered,1/4

1 Bothimagespublishedin[8]andreusedherewiththeauthors’permission.

(a) UniformPathsina3-4-3-12Tiling withBlueGreenSquiggleBackground[8].

(b) UniformPathsinaTruncatedTrihexagonalTilingwithNebularBackground[8].

Figure10:PrintsmadewithSolarFast.

(a) ArtprojectsfromRose-Hulman’s2025 SoniaMathDay. (b) T-shirtprinting.

Figure11:SolarFastprojectsandaclothexample.

inchplywoodfinishedwithlinseedoil,andthepiecehas26triangularpatterns, 12squarepatterns,andone12-gonpattern.ThecolorfulSolarFastbackdropis createdfromtilingswithpathsin3-,4-,6 ,8 ,and12-gons.Thispieceofart ispartofRose-Hulman’spermanentcollection,andadiscussionoftheartistic techniquesandeffortsisintheattachedsupplement.

4.2Three-DimensionalArt

Threedimensionalobjectsarevisuallypossibleasdigitalimages,butmanyare difficulttophysicallyproducewithoutspecialconsiderationandequipment.The mostimmediateissueisthatFDMprinterslimitstructurebecausetheydonot naturallyaccommodateoverhangingfeatureswithoutadditional,awkward,and unwantedverticalsupports.Thisrestrictionlimitscreatingthree-dimensional renderingsofpathsinapolytope,suchasaPlatonicsolid,withstandardFDM

(a) Awallclock. (b) Amediumwallpiece.

Figure12:PiecesthatcombineSolarFastprintmakingwithwoodcuttings.

printers.Wehavehadsuccesswithselectivelasersintering(SLS)printing,but wepostponethatdiscussionandfocusmomentarilyonthree-dimensionalitems possiblewithFDMprinters.

A3Dprinterrequiresastandardtrianglelanguage(stl)filethatapproximatesthesurface oftheobjectbeingprinted,butcurvesinthree-dimensional spacehavenosurface.Moreover,therearenostandardpythonpackagesthat generateprintablestlfilesfromparametrizedcurves,andassuch,wecreateda custompackagetogenerateprintablefiles.Themathematicalroutineissimple inconcept,asitessentiallyturnseachpathintoaspaghetti-likeobjectwhose surfaceisthenapproximatedbyatriangulation,whichisthen3Dprintable.We accomplishthistaskbyidentifyingacollectionofpointsonthepath,computing aunitnormaltothepathatthatpoint,andthenplacingpointsonacirclethat iscenteredatthepointonthepathandthatpassesthroughtheterminalend ofascaledversionofthenormalvector.Thisprocess“extrudes”acirclealong thecentralpath,withtheresultbeingacollectionofpointsonthesurfaceofa

thickenedversionofthepath,fromwhichwecreateatriangulationforprinting.

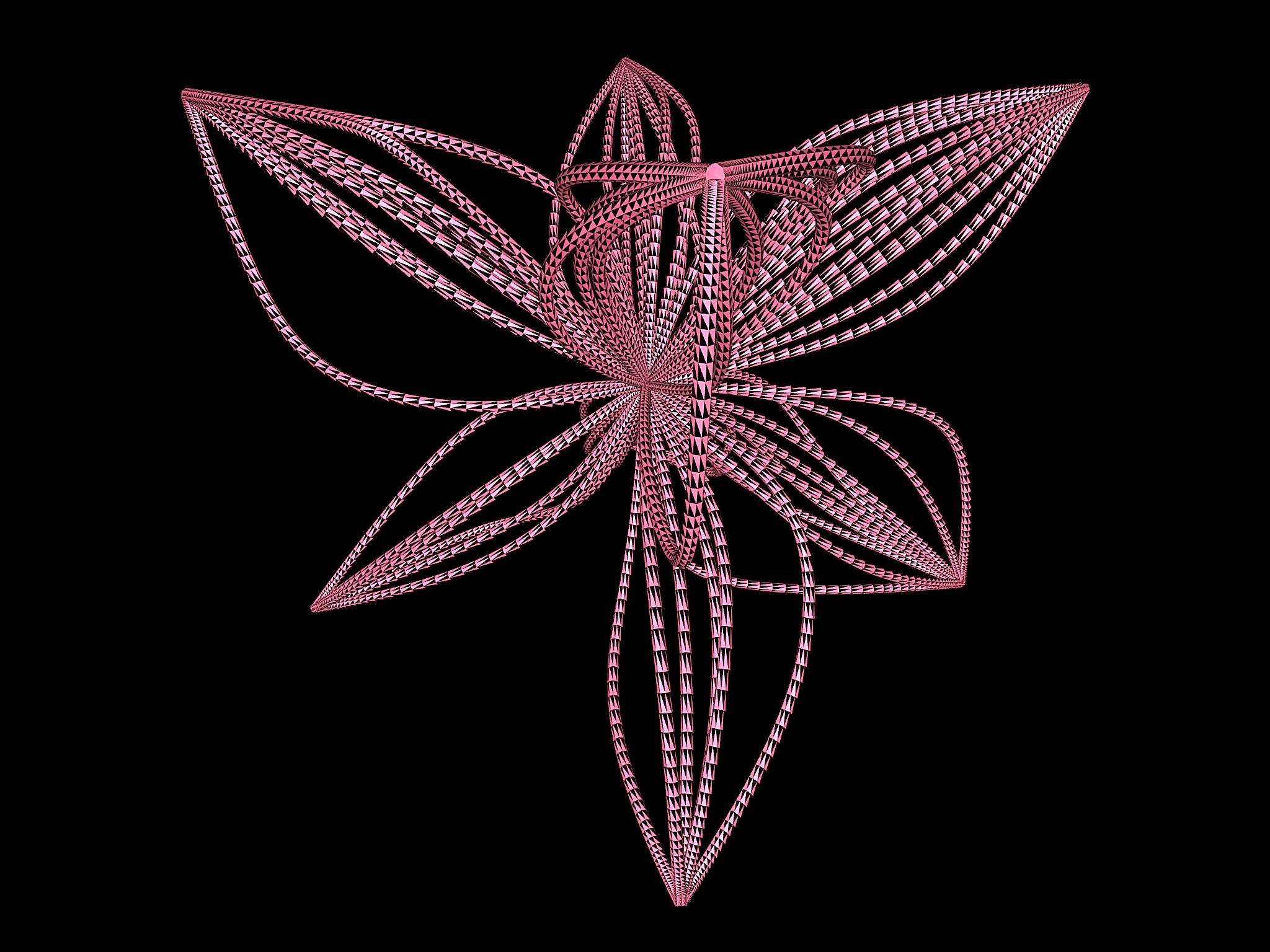

DaisiesandThistles

Daisieshaverelativelyflatpetalarrangements,andourtwo-dimensionalpatternsin k-gonsresemblethem.Weadjoinathree-dimensionalcentralpathas stemtocompletethefacsimile.Thesimplicityofthisdesignallowsustoprint daisieswithanFDMprintersolongasthecentralpathformingthestemhas limitedoverhang/bend.Anotheroptionisathistle.Wemimicthespikynature bysetting G(x) = x2 1 + x2 2 1togetaunitdisc.Solving(3)showsthat

andhence,centralpathsinadiscare(unsurprisingly)straightlines.Wecommentthatthisfactistrueforanytwo-normunitsphereinhigherdimensions. Figure13displaysFDMprinteditems.

Figure13:DigitalimagesandFDMprintsofadaisyandathistle.

SLSPrinting

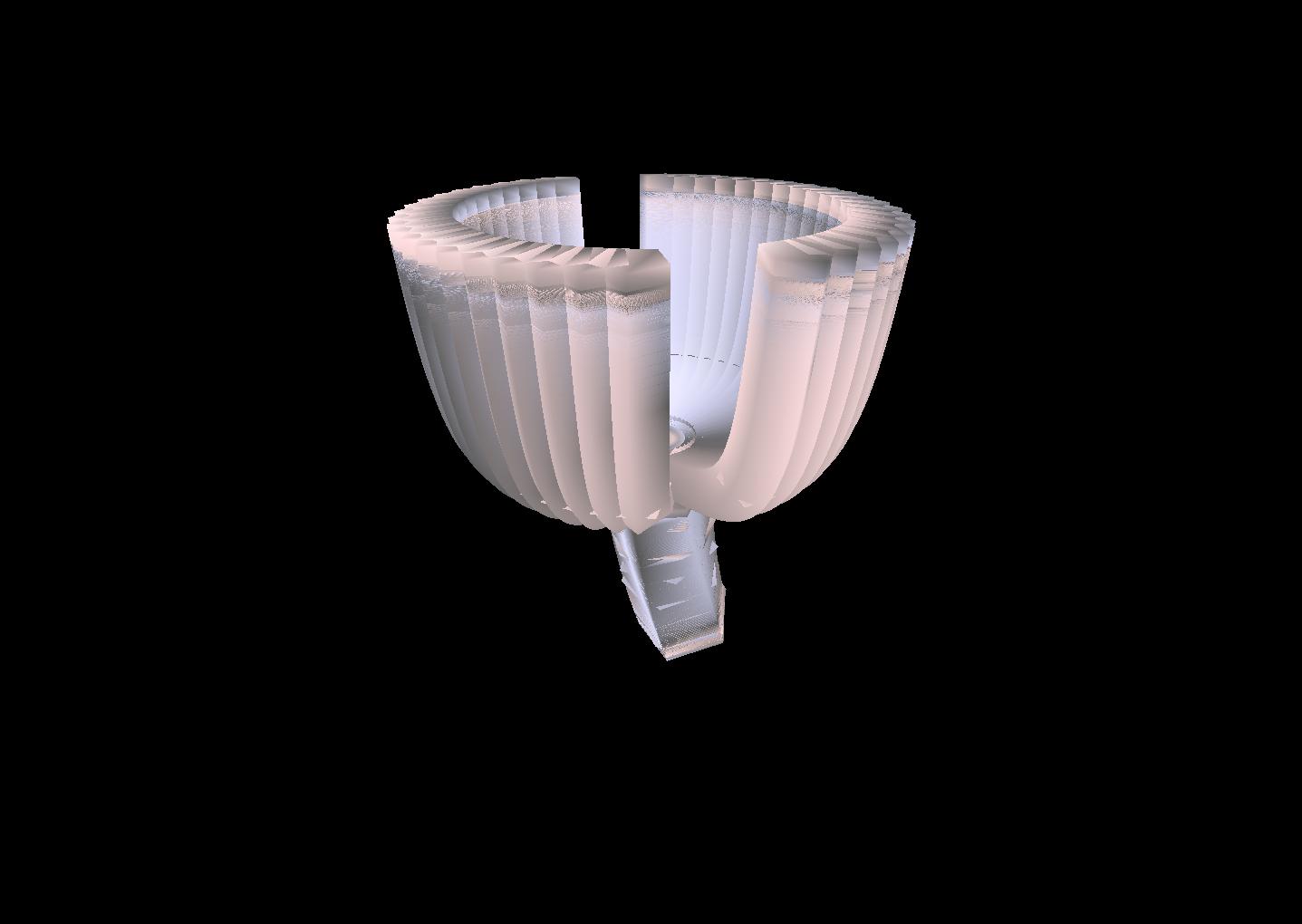

Selectivelasersintering(SLS)printinggivesasignificantadvantageoverother three-dimensionalprintingmodalitiesbecauseitformsamoldoftheitemas itisbeingprinted,andhence,thereisnoneedforadditionalsupports.SLS printersbuildaniteminlayerssimilartootherprintingparadigms,butSLS printingdepositsauniformlythinlayerofpolyamidematerialthatisthenfused withalasertocreateahorizontalsliceoftheitem(s)beingprinted.Theunused polyamidematerialremainsinplaceuntiltheprintiscomplete,andtheunused materialcreatesamoldthatsupportstheobject.SoSLSprinterscanprint space-curvesfromapproximatingstlfiles.AnSLSprinterwasunfortunately outsideourfundingability,butwewereabletopayathirdpartytocreatea singleprint.Weselectedrandompathsinacubeasourfirsttestcasebecause itwastheseimagesthatstartedthewholeproject.Figure14showstheoriginal three-dimensionalimageandtheSLSprint.WecommentthattheSLSprint isnotcubicalthoughthestlfileindicatedthatitshouldhavebeen.Wesuspectthateithertheprinterorthevendorreducedtheverticaldirectiondueto machinelimitationsorduetoproductionrestrictions.

(a) Anstlimageofacubicflower. (b) AnSLSprintedcubicflower.

5ConclusionandFutureGoals

Wepromotethatthecentralpathisathingofbeautyandisworthyofexploring artistically.Itsrevolutionizingimpactonthefieldofoptimizationis,initself,an esotericandrigorousworkofart,butwehavenowshownthatthecentralpath isalsoaunique‘brushstroke’withwhichwecancreateitemsofphysicalbeauty. Themathematicsofthecentralpathcontrolsthesetwo-andthree-dimensional constructs,andwemanifestbrushstrokesbychangingmathematicalmodels. Sointhisproject,artisticmodelingismathematicalmodeling,andthebridge betweenthetwoparadigmsisasignificantamountofcomputing.

OurprimarygoalforthefutureistoadvanceourabilitywithSLSprinting, andinparticular,wehopetopursuethecreationofalargeoptimizationgarden fullofflower-likeobjects.Muchofthemathematicalandcomputationaleffortis inplace,andwehave,forinstance,developedcodetogeneratepathsinthefive Platonicsolids.Theauthorshavefoundthisefforttobeauniquemathematical enterprisebecause,whileoptimizersandgeometershavelongknownhowto expresspolytopesintermsofeitherfacetinequalitiesorasconvexcombinations ofvertices,goingfromonetotheotherhasbeenachoreeventhoughthe mathematicalrelationshipsarewellunderstood.DescriptionsofthePlatonic solidsareintermsofstandardizedcoordinates,i.e.intermsofvertices,butour mathematicalmodelsrequirefacetinequalities.Weinitiallyformulatedalinear combinatorialproblemwhosesolutionwasanormaltoafacet,andwhilethis problemworkedwellonthetetrahedronandthecube,itprovedinsufficientor impossibletosolveontheoctahedron,thedodecahedron,andtheicosahedron. Sowemovedtoasearchoversubsetsoftheverticestoidentifywhichsubsets definedfacets,fromwhichwecouldthencalculateafacetnormal.Thisproved efficientonallfivesolids.

TheSLSprintinFigure14billustratespossibility,butthisflowerissurely, andwonderfullytotheauthors,abitBurtonesque.ThetulipandrosebudimagesinFigure15aremorerealistic,butwearenotyetabletoprinttheseitems. Theorem6establishesthatwecancreateasurfaceofpathsforthepetalofa tulip,andweuseourpreviousthickeningtechniqueonadiscretecollectionof pathstoemulateapetal.TheresultisanstlfileliketheoneinFigure15a.This

(a) Anstlimageofatulip. (b) Arosebud.

Figure15:DigitalrenderingsforpotentialSLSprinting.

techniquesadlyrendersafilewithanexcessivelylargetriangulationduetothe numerousintersectionsamongthepaths,andourprintingsoftwareisunableto slicetheobjectforprinting.Ahopefulsolutionistoextendourtriangulation softwaretoavoidoverlapsandintersections,aprojectthatisanear-termgoal. Therosebudin15biscreatedbypathsinatetrahedron,andwhileourthickeningtechniqueshouldworksimilartotheitemin ??,wehavenotyetgenerated stlfilesbecausewedonothaveaccesstoanSLSprinter.Thereismuchmore toexplore,andinparticular,weplantolearnwhichshapeslendthemselvesto SLSprinting,whatmaterialsandfinishesworkwellandgivelastingresults,and whichcomputationaladjustmentsensure/advancethemathematicalfidelityof theprinteditems.

Acknowledgments: TheauthorsthankMs.SoullyAbas,AssociateProfessor ofArt,andMs.ChristyBrinkman-Robertson,ArtCurator,bothattheRoseHulmanInstituteofTechnology.Theirsupport,encouragement,andguidance havebeeninvaluable.

References

[1] R.Caron,H.Greenberg,andA.Holder.Analyticcentersandrepelling inequalities. EuropeanJournalofOperationalResearch,143(2):268–290, 2002.

[2] A.Deza,E.Nematollahi,R.Peyghami,andT.Terlaky.Thecentralpath visitsalltheverticesoftheKlee-Mintycube. OptimisationMethodsand Software,21(5):851–865,2006.

[3] I.Dikin.Iterativesolutionofproblemsoflinearandquadraticprogramming. SovietMathematics.Doklady,8:674–675,1967.

[4] A.FiaccoandG.McCormick. NonlinearProgramming:SequentialUnconstrainedMinimizationTechniques.Wiley,1968.reprinted,ClassicsApplied Mathematics,SIAM,Philadelphia,1990.

[5] A.Forsgren,P.Gill,andM.Wright.Interiormethodsfornonlinearoptimization. SIAMReview,44(4):525–597,2002.

[6] R.Frisch.Thelogarthmicpotentialmethodforsolvinglinearprogramming problems.1955.

[7] P.Gill,W.Murray,M.Saunders,J.Tomlin,andM.Wright.Onprojected Newtonbarriermethodsforlinearprogrammingandanequivalenceto Karmarkar’sprojectivemethod. MathematicalProgramming,36(2):183–209,1986.

[8] C.Tasik&InteriArtResearchGroup. Ink:Rose-Hulman’sLiteraryand VisualArtsMagazine.vol.23,2025.www.rose-ink.wixsite.com/home.

[9] M.Halick´a.Analyticalpropertiesofthecentralpathatboundarypointin linearprogramming. MathematicalProgramming,84(2),1999.

[10] A.Holder.Simultaneousdataperturbationsandanalyticcenterconvergence. SIAMJournalonOptimization,14(3):841–868,2004.

[11] A.HolderandR.Caron.Uniformboundsonthelimitingandmarginal derivativesoftheanalyticcentersolutionoverasetofnormalizedweights. OperationsResearchLetters,26(2):49–54,2000.

[12] P.Huard.Resolutiondesprogrammesmathematiquesparlamethodedes centres.Technicalreport,NoteE.D.F.HR5690,1964.

[13] P.Huard.Resolutionofmathematicalprogrammingwithnonlinearconstraintsbythemethodofcenters.In NonlinearProgramming,pages207–219.NorthHolland,1967.

[14] F.Jarre,G.Sonnevend,andJ.Stoer.Animplementationofthemethod ofanalyticcenters.InA.BensoussanandJ.Lions,editors, Analysisand OptimizationofSystems,pages295–308,Berlin,Heidelberg,1988.Springer BerlinHeidelberg.

[15] N.Karmarkar.Anewpolynomial-timealgorithmforlinearprogramming. Combinatorica,4:373–395,1984.

[16] NarendraKarmarkar.Anewpolynomial-timealgorithmforlinearprogramming.In ProceedingsofthesixteenthannualACMsymposiumonTheory ofcomputing,pages302–311,1984.

[17] L.Khachiyan.Apolynomialalgorithminlinearprogramming. Soviet Mathematics.Doklady,20:191–194,1979.

[18] V.KleeandG.Minty.Howgoodisthesimplexalgorithm?InO.Shisha, editor, InequalitiesIII,page159–175.AcademicPress,1972.

[19] J.DeLoera,B.Sturmfels,andC.Vinzant.Thecentralcurveinlinear programming. FoundationsofComputationalMathematics,12(4):509–540, 2012.

[20] E.NematollahiandT.Terlaky.AsimplerandtighterredundantKleeMintyconstruction. OptimizationLetters,2:403–414,2008.

[21] C.Roos,T.Terlaky,andJ-PhVial.Interiorpointmethodsforlinear optimization.2005.

[22] J.Sauppe,editor. MathematicalProgrammingGlossary.INFORMSComputingSociety, http://glossary.informs.org,2006–24.OriginallyauthoredbyHarveyJ.Greenberg,1999-2006.

[23] G.Sonnevend.An“analyticalcentre”forpolyhedronsandnewclasses ofglobalalgorithmsforlinear(smooth,convex)programming.In Lecture NotesinControlandInformationSciences,volume84,pages866–875, Berlin,Heidelberg,1986.Springer,SpringerBerlinHeidelberg.

[24] G.Sonnevend.Newalgorithmsinconvexprogrammingbasedonanotionof “centre”(forsystemsofanalyticinequalities)andonrationalextrapolation. In TrendsinMathematicalOptimization:4thFrench-GermanConference onOptimization,pages311–326.Springer,1988.

[25] Tam´asTerlaky.Twenty-fiveyearsofinteriorpointmethods.In Decision TechnologiesandApplications,pages1–33.INFORMS,2009.

[26] S.VavasisandY.Ye.Aprimal-dualinteriorpointmethodwhoserunning timedependsonlyontheconstraintmatrix. MathematicalProgramming, 74(1):79–120,1996.

[27] M.Wright.Theinterior-pointrevolutioninconstrainedoptimization.In HighPerformanceAlgorithmsandSoftwareinNonlinearOptimization, pages359–381.Springer,1998.

[28] M.Wright.Theinterior-pointrevolutioninoptimization:history,recent developments,andlastingconsequences. BulletinoftheAmericanMathematicalSociety,42(1):39–56,2005.

[29] MargaretHWright.SomepropertiesoftheHessianofthelogarithmic barrierfunction. mathematicalProgramming,67(1):265–295,1994.

[30] StephenJWright.ModifiedCholeskyfactorizationsininterior-pointalgorithmsforlinearprogramming. SIAMJournalonOptimization,9(4):1159–1191,1999.

Supplement:ArtisticTechniquesandLessons

Wepresentinthissupplementtheartistictechniquesusedtocreatethelarge pieceofartinFigure12c.Thescaleofthisprojectchallengedourintentto usewhatwehadlearnedfromsmallerworkstocreateanexpansivepiecefor aspaciousandwell-traveledhallway.Techniquesthathadbeensuccessfulfor moderatepiecesjustdidn’tscaleeasily,andwespentmonthstinkeringwith software,3Dprinters,lasercutters,anddyeingprocessesbeforegainingthe finessetocreateaprofessionalproduct.Wecatalogourmethodsheretoaid othersinterestedinsimilarprojects.

Thisworkcombinedthreecomponents,thosebeingwoodcutoutsofcentral pathsforthefrontfacing‘frames,’3Dprintedtilingstoembosspatternsonthe underlyingpaper,andthedyeingprocesstocreatethedynamicofcolor.We addresseachoftheseprocessesbelow.

5.1WoodCutouts

Westartedwithacollectionofpathsina k-gonforeachwoodframe,butthese pathsaremathematicallyone-dimensionalandhavenoarea,whichmeansthat theycannotbeusedtocreatewoodframeswithoutimposingawidth,i.e.we neededto‘thicken’thepaths.Wesavedeachimageasascalablevectorgraphic (svg)fileandusedtheopen-sourcesvgeditorInkscapetothickenthepaths. TheautomatedprocessinInkscapeunfortunatelyleftthecornersemptyas seeninFigure16a.Thelight-bluecurvesareourcomputedcentralpaths,and thelargerdark-blueareasareInkscape’sthickenedversions.Theintersection ofthethickerpathsleftvoidsatthecornersthatwehadtomanuallycorrect ineachimage,seeFigure16b.Wethenusedalasercuttertocutwoodframes thattiledwithoutawkwardgaps.

5.2SolarFastDyeing

JohnHerschelinventedsolar/sunprints,calledcyanotypes,inthe1840s,which heproducedbysaturatingapieceofpaperorclothwithamixtureofferric ammoniumcitrateandpotassiumferricyanideandthenexposingthesaturated itemtoUVlight.Thechemicalsreactedunderthisexposureanddyedtheitem blue,withblueprintsbeinganearlyexampleofthetechnique.Adownsideof cyanotypingisthatweonlyhavethesinglecolorofblue,butwefortunately haveasimilarcontemporaryprocessthatusesSolarFastthatpermitsavariety ofcolors.WehaveexperimentedwithbothcyanotypesandSolarFast,andwe generallypreferSolarFast.

3DPatterns

Thesvgfilesof2Dpatterns,liketheonesthatweusedforlasercuttings,are notdirectly3Dprintablebecauseathickenedpathintwo-dimensionshasno volume,and3Dprintsrequiresurfacesofvolumes.Wehavealreadynotedour customsoftwarethatextrudescirclesalongapathtocreateaprintablestlfile inSection4.2.Thiscodealsoworksforpathsintwo-dimensionsbysetting thevertical z-coordinatetozero,butitdoessoinawaythatleavesthethreedimensionaltessellationsofthethickenedpathsshyofbeinghorizontallyflat. Wehaveinsteadusedstandardsoftwarein,forinstance,ourprinter’ssuiteof utilitiesthataccepts2Dsvgimagesandthickensthemverticallyforprinting. Thishasproventrustworthyandhasgivenuscontroloftheverticalheightof theprint,whichisanimportantdesignelementforthedyeingprocess.

The3Dprintedpatternsofthedyeingprocessarenegativesbecausethey shieldultravioletexposureandleaveanundyedpattern.Thegeneralprocess istoapplydyetowatercolorpaper,whichiscolorlessatthatpoint,placea 3Dprintedpatternonthepaper,coverthepatternwiththickglasstohold everythinginplace,exposethepapertosunlighttoactivatethechemicalsand createcolor,andthenwashanddrythepaper.Thisstraightforwardprocess workswellforsmalleritems,butitrequiresspecialattentionasitscalesfor largerpieces.Themostdauntingconcernisthatlargepiecesofwatercolor papertendtowarpandshrinkastheyareexposed,leavingthenegativeless thaneffective.Theflawedresulthasweaklookingpathsthatlackcontrastand thattarnishthevisualacuityoftheunderlyingmathematics.Wediscovered solutionstoseveraldesigndecisionstoremove,oratleastlimit,thisconcern.

Thetypeofwatercolorpaperisimportant,andforlargerpieceswefound that140poundcold-pressedpaperwithacompositionof25%cottonworks well.Heavierweightslike300poundpapercanworknicelybecausetheyreduce buckling;however,theirheavierweightchallengesgluingthemtothewooden framesevenwithreducedbuckling.Weexperiencedmorebucklingwithlighter weightpaperbutwereabletobetterpresstheprintflataswegluedittothe frame,creatingapolishedandtaughtappearance.Usingacold-pressedpaper gaveusaslightlytexturedsurfacethatworkedwellwithSolarFast.

ThenegativesofourlargestprintsexceededthedimensionsofourFDM

printer,andassuch,weprintedthenegativesinpiecesthatwerethenwelded togetherwithasolderingirontocreateonelargepattern,seeFigure17.The dimensionsofthepathsandthetypeoffilamentarebothimportantforfitment anddyeing.WehaveusedbothPLAandPETGfilaments,butwepreferPETG becauseithasthermalpropertiesthatallowthereuseofthepattern.PLA patternsactuallyworkabitbetterforlargeprintsbecausetheyconformbetter tothesurfaceofthepaper,buttheywarmanddeformduringtheexposure period,leavingthemquestionableforsubsequentprints.SoPLApatternswork wellbutcreatewasteandlengthenthecreativetimelineduetotheneedtoprint andassembleanewpatternforeachprint.Thedimensionsofthe3Dprinted pathsareimportantbecausethewidthdefineswhattheeyewillseeofapath, andtheheightaltershowsunlightwillinteractwiththedye.Wehavefound thatPETGwithapathwidthvaryingfrom1to1.2mmandaverticalheightof 1 5mmresultsinanegativethathasaccuratefitmentandbalancedflexibility, resultinginprintswithgoodvisualacuityandcontrast.

SolarPrinting

Thegeneralprintingprocessdescribedabovehasseveralsmallerbutimportant stepsifyouwanttocreatehigh-qualitylargeprints.Themostimportanthindrancetoovercomeisthefactthatthepaperadjustsasitwarmsduringthe exposureperiod.Wewarnthatwetriedseveralwaysofimmobilizingthepapertolimitthedeleteriouseffectofexposingthepathsthatweresupposedto shieldedbythenegative.Noneofholdingthepapertaughtwithtape,adding additionalglassforextraweight,orpaddingthebacksideofthepapertohelp impressthenegativeworkedindividually.Thetensioncreatedbythewarming paperisimpressive,andattemptstophysicallyaffixitprovedineffective.What insteadworkedwastodelaythepaper’sdeformationbykeepingitwetduring thedyeingprocess.Weaccomplishedthistaskbywettingthepaperpriorto dyeingit,whichleftthepapersufficientlywetduringtheexposurethatitdid

notappreciablydeform.Thistechnique,alongwithsomephysicalbinding,gave excellentresults.Ourstandardprocedureforlargeprintsisbelow.

1. Soakthepaperinwaterforfivetotenminutes.

2. Combinedyeandwaterinsmallbowlsorcontainersinaroughly2:1ratio.

3. Brushdyeontopaperwithaone-inchfoambrush,witheachcolorgetting itsownbrush.

4. Lightlymistthepaperwithwaterusingaspraybottle.

5. Useatwo-inchroundspongetoblotthepaper,removebrushstokes,and spreadthecolor(inaquasi-randomway).

6. Placethepaperonaflatpaddedsurface.

7. Placethe3Dprintednegativeontopofthepaper.

8. Useyourhandsorarubberbrayertoslightlypressthenegativeontothe wetpaper,whichsomewhatadheresthenegativetothepaper.

9. Placeapieceofglassontopofthenegativeandpressdownfirmly.Multiplepiecesofglassforextraweightcanhelp.

10. Takethepieceoutsideandexposeitinashadyspotforaroundtwenty minutes-longeriftheUVindexislow.Theprintisdoneonceyouare happywiththecolor.

11. BringtheprintbackinsideandwashitfollowingtheSolarFastinstructions.Makesuretheprintdoesnotbecometranslucentwhilewashingit. Stopwashingimmediatelyifso.

12. Placethewashedprintonastretchingboard.

13. Wipethesurfaceofthepapertoremoveanyremainingdyewithadry papertowel.

14. Tapetheedgesofthepapertothestretchingboardandwaitfortheprint todry.

Wecommentthatpre-soakingthepaperaffectsthecolorofthedye,andmost notably,itresultsinthecolorbeingtruertotheadvertisedhue.Wesuspectthat thiseffectisduetotheextradilutionofthedye,butitcouldalsobedueinpart becausethedyeabsorbsdeeperintothepaper.Inanyevent,theconcentration ofthedyeisanimportantconsiderationofanartistastheyusethistechnique.