“THERE IS NO SUCH WORD AS CAN’T”

GRANNY ELSIE

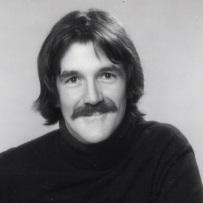

ERIC MCMILLAN BIOGRAPHY 1942 – 1980

Third Edition

© Eric McMillan 2024

HIGHLIGHTS

Chapter 1 – 1942 – 1960, page 5 - Being born and leaving home

Chapter 2 – 1960 – 1964, page 12 - Art Student

Chapter 3 – 1964 – 1968, page 16 - Miracle Lady

Chapter 4 – 1968 – 1974, page 20 - Canada

Chapter 5 – 1974 – 1980, page 28 - Sesame Place

The formation of the personality takes shape in the early days of one's life. The clay of DNA colors it’s shape. As I dip into my past life I try to understand what drove me. How did I earn my good fortune, or was it just my ‘ Veil’?

I tap into many possible source roots, the one that appears correct is an image of me the eager innocent child, and Grannie Elsie trying to correct my manner of speaking with 'There is no such word as can't'. I misinterpreted her meaning and came to understand under her authority that everything is possible. I think the idea lived in my mind and influenced my creativity.

The following pages are my biographical reflection from 1942 to 1980. It’s also a celebration of the amazing work of my creative partner Rosemarie Barbara Duell. Without her, this story of the flowering of my creativity never would have happened.

Eric

Anthony McMillan

Eric McMillan biography, 1942 to 1960

My birth was riddled with fate and indifference. It was April thirteenth 1942. My mother had earlier made many attempts to abort me, so she was much relieved when the midwife delivering me said “Mrs. McMillan you have a beautiful boy but he is dead”. These were strange times, the time of a World War, bombs were falling out of the sky and Sheffield the place of my birth was also the birthing place of English bombs, Hitler wanted to destroy its steel making mills.

Years before my birth my parent’s relationship had turned sour, filled with much disappointment on both sides. So adding another member to be fed was not an attractive prospect. In those times divorce was rare, particularly in the working class. In addition, my mother didn’t want another child and being a devout Roman Catholic believed a divorce would mean eternal banishment from Heaven and eternal residency in Hell.

According to my mother, a person of much superstition, I was born on Friday the 13th, (in fact it was a Monday) which apparently has high astrological implications. Plus, the real ‘Biggy’ was that I was born with a Caul covering my face, an after-birth veil covering the face of a newborn, soaked in powerful superstition. The veil prophesied a lucky life, born to travel, never drown. It is said a sea captain would give a fortune for one. Additionally to add to my psychic kitbag, I was born with a ‘giddy eye’ a squint! All these traits should have got me into the psychic hall of fame.

The ‘don’t give up’ attitude of the midwife is the beginning of my life’s long trail of luck. The midwife decided to try to shock my system, plunging me first into a bucket of cold water, then a bucket of hot water and to my mother’s surprise, I began to cry.

Shortly after my birth our house was bombed and we were then evacuated from Sheffield over the Pennines to damp Manchester to settle in a two-up-and -two -down terraced house in the shadow of Manchester’s notorious Strangeways jail.

My earliest memory, I am perhaps two years old, I have a feeling of sitting like a baby Buddha on top of a mountain of war rubble, looking down into the town below, watching the moving traffic riding the thin strip of open road.

Another memory is of two children, each about three year’s old, standing on a mound of freshly bombed rubble, World War Two was still raging. Each child has in its tiny hand a brick fragment, each child eagerly hitting the other child with its brick weapon, blood trickling from their heads. They are cheered on by their mothers, each wishing her child to be the winner of the bloody combat. I still have a clear memory of that event.

I was one of the same two kids, hungry and ignorant, rummaging through rubbish bins for food, only to discover a pop bottle with a very attractive looking liquid inside. We were shaking the carbonated bottle we had discovered. It had a pot stopper with a fussy wire clamp set up. We hadn’t the knowledge or the strength to operate it, so we tried smashing the pot stopper off, the pressure inside the bottle built, and it exploded. On that occasion both mothers pushed the two bleeding boys in a pram up the steep hill to the Jewish hospital. I was lucky, I still carry scars on my face, one on my left cheek and the other just above my right eye. I have no memory of the explosion just the appeal and sweet promise of the contents of the bottle.

Strangeways was a jail my family broke into during the bitterly cold winter of 1947. My father was unemployed, my mother was heavily pregnant, hiding her younger brother, my uncle Vic a wanted deserter from the Royal Navy, her father was in the middle of an epileptic fit, the result of a piece of World War 1 shrapnel lodged in his skull, his wife was dying a painful cancerous death, and Peter the Irish lodger who was the only person in the house with a job.

It was an unusually cold winter. My uncle Vic proposed a solution. They have coal in the jail, and that part of the prison would be easy to break into and get some coal to provide them with warmth and comfort. The plan was adopted. My uncle Vic, my father, and Peter the Irish lodger were to break into the jail yard to steal some coal, and bring it home.

The plan worked fine, they broke into the coal storage area and were just about to return home with the coal, when my uncle Vic with his sharp eyes noted the lead flashing protecting the roof edge of the jail. Scrap metal just after the Second World War was in big demand, and lead was like gold in the world of scrap metal. So ever ambitious, my Uncle Victor climbed up on the jail roof and began stripping the lead edging off, throwing it down to my father and Peter in the yard below. The noise of this roof activity alerted the guards inside so they came into the yard and captured all three who then spent the night in jail, inside a warm cell, whilst the rest of the family froze on in to the night.

I was a feral child. Most of my early childhood was spent playing in the debris of war, climbing through bombed houses, and playing in bombed factories. At one bombed factory we discovered paint. We played Cowboys and Indians and I was the painted Indian. In my memory I can clearly see myself, a four year old naked little boy standing upright in a tin bathtub and my dad scrubbing me with a floor brush cursing my older brother John.

After the death of his first wife my grandfather moved back to his home town Sheffield. On his return visiting his brother he met Elsie Higgin, a servant working in some grand house. He must have charmed her, he was not in great health, in addition to being blind and epileptic. Elsie was one of twenty siblings. When her mother died, when she was eleven years old, her eldest sister put Elsie into the care of the Workhouse.

When they married I was handed to them as a wedding gift, the unwanted feral child. She was the first person ever to cry for me. It was a few weeks after I discovered myself living in Sheffield. Physically I wasn’t in great shape. One morning, as I lay in bed not wanting to get up my granny Elsie, in an attempt to get me out of bed, poured a cup of cold water over my head, she thought I was just pretending to be ill to avoid going to school. As they carried me out on a stretcher, I see her standing, crying, as I pass through the bedroom’s open door,

Looking back on the details of my earlier life, I believe I would have died by the age of six, had it not been for me being placed into the loving care of my Sheffield grandparents. The years I spent with my grandparents were critical to my personal development and shaped me and gave me the energy to overcome my family’s later attacks upon my psyche.

After five years my granddad decided to make a pilgrimage across the Pennines to make peace with my father about some long standing dispute. During those five years I hadn’t seen my parents nor my older brother and younger sister.

My granddad was very ill. It was a cold dark damp Manchester that greeted us. Initially, for a moment, it was a dream for me. There were my beautiful mother, my piano playing father, my brother John with his blue eyed charm and talent, and a little sister. We must have been there for about two weeks. I was enchanted by my family, it all felt very young and fresh after my time away. Meanwhile granddad and granny were abandoned, left like unwanted guests in an empty upstairs room. It was 1952, I was ten years old, granny Elsie came down and said “Tony granddad wants us to go back to Sheffield will you come?” I said “no grandma I want to stay ” . That night my grandfather died.

I often wonder had I agreed to return with them to Sheffield would he have lived longer, and what a different kind of person I might have grown up to. Following the death of my grandfather, my granny Elsie was told to leave my parent’s home, carrying with her my blind grandfathers white walking stick. For me it was as if my soul’s bubble had burst. I had landed back into the care of a violent, drunken, dysfunctional family.

My father played the piano quite well. He could make a week’s pay in a weekend playing in the parlours of local pubs. With the possibility of more piano playing jobs, we moved to Lancaster to be closer to Morcambe an English seaside resort. We moved in an ancient barely working car, its cruising speed must have been around fifteen miles per hour, I remember being overtaken by all other cars on the road. I think my father worried that the car might break down if he drove too fast. So, slowly we made our way to our new home.

Lancaster is an ancient town, sitting on the banks of the river Lune. We, a family of five moved into an equally ancient rooming house. It was stuffed with old and mainly busted furniture. There was an attic full of treasures. Snowshoes were one delight; another jewel was a wind up gramophone. The rooming house was run by some distant relative of my father. With some obscure connection to the entertainment business, Jim Firth the landlord did the occasional Father Christmas.

One of its lodgers I clearly remember was a young woman called Klondike. She had a glide, a squint that I found odd. She worked in the local cotton mill. Her dark curly hair was always filled with cotton fluff. The noises in such mills were so loud, that the cotton workers quickly learnt to lip read. The cotton fluff thrown off by the manufacturing process was considerable. She was always working in a fog of cotton fluff. I once saw her naked breasts. They were a sculptor’s dream.

Another was Aubrey St John. A fatherless child living with his unmarried mother at the edge of town, at the end of our street. He was ten years old, filled with amazing energy, and creativity. Aubrey was a natural leader, fun to be around, daring and creative, with little respect or fear of authority. One Sunday he led us four children over a high wall, to try driving the trucks in a storage yard. That’s where I first tried to drive a truck, but unfortunately one of us accidentally reversed into the wooden main gate. We tried to patch it, but on Monday morning it must have been obvious.

Aubrey spent such a short time in my life, but in my memory he blossoms. At age eleven he was removed from the care of his mother and placed into the care of a Borstal School for difficult and criminal children. He was the brightest of children, he was a mechanical wizard who transformed the timer from a street gas light into a large pocket watch, and he built my first bike from the scrap remains of other bikes. It was an amazing machine all for the cost of five shillings, my weekly pay from delivering newspapers I often think if his extraordinary talent was ever recognized and joyfully employed.

After several months living in Lancaster, my mother ran away, her plan was not working out. For me Lancaster holds the most painful of all my memories of time spent in the care of my parents. I was fresh from living with m y grandparents; I was both ignorant and innocent. I was a sensitive ten year old child. I had only recently rejoined my family. I still have the scars on my body from that time of my older brother’s knife attacks. It was during my time in Lancaster that I was sent to school dressed in rags, holes in the back of my pants, holes in the knees of my pants, but what hurt most of all is that nobody seemed to care what happened to me.

One night in Lancaster whilst playing the pub piano my father was persuaded to adopt a dog called Star, being assured of the dog’s value as breeding material. So my father returned to the rooming house drunk, with Star in tow. After a few days the Star money making illusion faded. But for me she was a gift, a pal, a friend, always pleased to see me, always welcoming, a companion. Following my fathers failed plan in the breeding venture, Star was just left to wander around the rooming house. The landlady complained the dog was defecating in the common spaces. My mother’s response was to instruct me to take Star, my best friend to the vet, and have her put to sleep. I was ten years old, but even then I saw the futility of running away from home with Star. So I obediently lead her to the vet and passed on my mother’s deadly instructions…

Lancaster was where I began at the age of ten to join the working world. Very early in the morning, before going to school, I was delivering the morning papers for W H Smith for a shilling a day. At the end of the week I was paid five shillings of which my mother took half.

Following my mothers’ departure, my father, my brother and I moved with our few possessions from Lancaster to Salford on a coal truck to join my mother. When we arrived at the Vernon street rooming house, my brother and I were black from sitting on the open deck of the coal truck with all its blowing coal dust. It was at Vernon Street where I taught myself to clamp my teeth onto the blanket and when securely locked on, fall to sleep still holding tight to the blanket with my teeth. Otherwise my brother who I was sharing the bed with would take all the blankets and left me exposed to the cold and damp. There was no heating other than blankets and body warmth.

It was from that rooming house I was sent to Lower Broughton Secondary Modern School, a school filled with eager, keen and qualified teachers. It was during my brief time attending this school that my artistic ability was noticed, with one of my drawings of a tree being exhibited at the Salford Art Gallery. But I was soon removed by my mother from that sensible secular school. The local Catholic school had a primary school for my younger sister. If I was sent there I would be saving my mother the time and effort to take my sister to school. So my mother enrolled me in Saint Boniface’s Roman Catholic School, Lower Broughton. It was an educational institute, run like a detention center with its Catholic Catechism of violence, hatred, prejudice, and ignorance.

It was in my final year, that the teacher ordered me to the front of the class, told me to put out my hands, and then proceeded to thrash both my hands with a splintered cane. The reason was simple: control by force. I had become the ‘cock of the school’ by responding to constant challenges to fight. I believe the teacher thought that by publicly humiliating me, making me cry and beg for mercy, he gained power over me and therefore the other children. But despite his best efforts I would not cry, this reaction appeared to increase the vigor of his lashings. He only stopped when he saw the blood from my butchered hands, dripping on to the classroom floor. When I later showed my hands to my mother her reply was “you must have done something wrong to deserve it.!”

My family were all petty thieves. When I rejoined my family the only book in the house was an English dictionary that had been stolen from a local police station. I remember my father coming home and like some illusionist pulling chickens out of his pants after a day’s work at a kosher chicken killing place and another time when he worked at a clothing factory, he came home wearing three pairs of pants. They even stole from each other, their own family members.

When I left school I wanted a motor bike but it would be a year before I would be able to legally drive one. I did extra work in the evening to assemble enough money to buy a second hand motor bike. By my sixteenth birthday I had saved twelve pounds, at a time when I was making thirty two shilling a week. But I was ignorant about the mechanics of motor bikes. So my father, brother, Uncle Vic, and Tom the one armed motor cycle expert, all volunteered to go to King Motor sales on Chester Road, Manchester and buy the right motor bike for me. The first thing they did on arrival at Kings Motors, was to take a pound each from my original twelve pounds , then proceed to buy for the remaining eight pounds an ex WD 1942 BSA 650 cc motor bike.

I was lucky I didn’t kill myself on it, I had a low speed crash but was thrown clear of the wrecked bike. But I do remember doing ‘The Ton’, a hundred miles an hour on it. My rimless spectacles snapped, I still had the choke on; the exhaust pipe was white hot. I really was not qualified to ride such a powerful machine.

Leaving school at the age of fifteen I thought of joining the Royal Navy and become an Able Seaman, like my hero, Uncle Vic. When I applied to join the Royal Navy they turned me down because of my poor eyesight

Other than “get a job” I received no career counseling from my parents. As a lanky semi illiterate, short sighted, ignorant, innocent fifteen year old I walked into the heart of the world’s first industrial park, Trafford Park, Manchester, looking for a job.

At the end of the day I did finally find a job. Thirty two shillings a week, I was hired by Banister and Walton, construction engineers as an apprentice Template Maker. The job turned out to be the cleaning of toilets, the brewing of tea, the getting of lunch orders and brushing the workshop floor. After three months I asked the foreman when I would get my own bench, he just laughed at me and said “perhaps in two years”.

I decided I couldn’t wait that long. I went off to the Youth Employment Exchange and they had a record of me being good at Art at school. They had a job for an apprentice House Painter; this became the beginning of my climb up and through the social escape hatch into a different reality.

Because of my mother’s thrift I almost became an apprentice carpenter because blue overalls were cheaper than white overalls. The building contractor I went to work for also had a carpentry department that could have been my job direction. For months I was the only house painter on the job dressed in blue overalls.

To begin with as an apprentice I was put in the charge of Bob a young recently married house painter. I worked with him painting the outside of public housing estates. Until one Christmas Eve, a time when nobody wanted painters around their homes, the owner brought us all back to the company workshop to paint the outside of the building. Bob always eager, in competition with another young painter dashed up the ladder to paint the inside of the cast iron gutter. Some mistake caused Bob to fall three stories to the pavement below.

My memory is of the owner’s reaction. The falling paint can full of red lead paint made a direct hit on his car. I had the impression that he was more concerned with his car’s new paint job than the affairs of Bob lying in pain on the pavement. I never saw Bob again although I later heard that his foot was permanently damaged and with the settlement from the accident insurance he was able to open a corner store.

In the New Year I was partnered with another painter and decorator, Harry Johnson a mature and wise man. A real craftsman, who as a hobby conducted a brass band, as well as being an accomplished trombone player. Working with him I worked on more interior jobs like the insides of pubs. I was keen and eager and by that time I think I was the fastest brush in Salford.

Then one day Harry spoke of the need for qualifications to become the best painter and decorator. I believed Harry and asked my boss to allow me to go one day a week to attend trade school. My employer insisted that going to trade school was not necessary to my improving my skills and as a reward for my enthusiasm he gave me rolls of wallpaper to practice the trimming of wallpaper, with long wallpaper scissors. I practiced till my hands bled, but still I still believed Harry.

So I quit a perfectly good job, to go to work for a painting contractor who would agree to my getting one day a week off to attend painting and decorating school. I found such a person in Ernie Griffiths. My former employer had been high quality work. On my first day on the Ernie job we were painting the outside of a private school. Brush and paint can in hand I began my climb up the ladder, somewhere towards the top the rotten rungs of the ladder collapsed, I game sliding down without spilling my paint. In the first year he allowed me the day off to go to school, but he treated me like an indentured serf. In the second year he withdrew his offer.

Still determined to follow Harry’s advice, I went in search of another house painting contractor who would agree to my taking the day off to attend trade school. I found Eric Rose 43 Cavendish road. Through him I was able to see inside the workings of a Jewish community. At the end of the working day I would bicycle down from Cheetham Hill, back to my broken family living in the damp low lying swampy Lower Broughton, thinking “why don’t we, like them help each other”.

The painting and decorating school experience has left me with very few impressions. I was an eager student, in my first year I was given a book prize for excellent work. My mother adopted that book with great pride. My most memorable experience came at the end of the semester. At the beginning I was given a white painted wooden board, twelve inches by thirty six inches with a finish like glass. I had to burn the paint off with a blow torch and scraper. I spent a whole semester working on that one piece. When I had burnt off all the paint, I discovered ‘1923’ carved into the wood itself. Since that year and perhaps even before another person had stripped that same board and over several weeks brought it back to its impressive original glass like finish. I also had good marks in that department.

Painting and decorating school was my bridge into Art School. The Painting and Decorating Department was on the same floor as the Art School, yet we were in different social bubbles. In order to earn extra money I worked as a waiter in the evening. This presented the opportunity to swim in a different social bubble, beyond the booze and the winning the pools.

One night working as a waiter in the Left Wing club in Manchester, a group of customers, students from Salford Art School came in. Normally I would not have engaged with them, but as a waiter conversation was inevitable. They spoke of revolutionary changes taking place at Salford Art School. It’s main past focus had been on textile design. In order to adjust to the requirements of the times the school was adopting the Bauhaus approach to art education. But most important for me was that they were desperate for students to enroll in this adventure in art and design. The students encouraged me to apply and also told me that the Salford City Education Department gave out grants to promising students. I applied for a grant and qualified, my first year grant from the citizens of Salford was one hundred and twenty five pounds plus fees.

At first my parents didn’t like the idea of me going to school full time. They were concerned at the economics of it, that I would stop paying for my keep, but I demonstrated there would be no economic loss as I could supplement my grant from the Salford Council with working nights as a waiter I could still pay my way.

But once I began to attend the Art School, the flaring of tempers and heated violent arguments became normal. My father couldn’t deal with the idea of me lounging about at Art school, whilst he was laboring at some job he didn’t like. No longer were my hands crowded with dirty finger nails and calluses, the mark of the laboring class. In my first few months I was presented with a choice: leave Art School and stay home, or stay at Art School and leave home. It was not an easy choice, I clearly remember my mother on her knees, crying begging me to stay as I moved with my rucksack of possessions towards the front door of 14 Dow Street. I was almost persuaded by her, but I knew it would never change, I left.

Leaving my family was a challenge. I was not equipped to deal with setting out on my own journey, away from my family, away from my class, no longer anchored to the anger and bitterness of the life of my family, yet scarred by the experience.

Class awareness is an ego drain for the ones at the bottom. There is a certain manner of speaking English that still makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up, as with a dog on high alert. I was branded by my tongue, even though I spent years trying to disguise my working class accent, learning how to speak in a different way.

Academically I was a ruin of ignorance. From five to fifteen I went to nine schools, seven of which were Catholic with low standards. My eye sight changed when I was eleven years old, from that time on I couldn’t see the black board, and even the teachers became fuzzy.

To qualify for the Art School I had to take a written English test. With my educational background I would have failed but fortunately fate intervened: I was given a stolen copy of the English exam paper and so was prepared for it and passed. The Art exam was easy; it was the time of Jackson Pollock and Splash Painting.

I was now a full time student at Salford School of Art and Design for the next four years. My reality had been transformed. I was a stranger in a different world.

One of my first Art School adventures was to organize a children’s art exhibition. It’s curious how much of my creative work over the years touched the edges of children at play.

My class of 1960 was the first class in the Bauhaus experiment. 1960 was the Foundation year. After my previous working life experience, attending Art School was like being in an up market kindergarten, it was all playful: sculpting, life drawing, action painting, photography and other often insane academic attempts to infuse the student with creativity.

That was the first year, the year of my adjustment to no longer climb ladders to paint, but climbing up a different ladder into a different English class. It wasn’t only my thick accent that separated me from the other students, it was my working class habits - I rarely bathed. I had no forward plan, other than struggle to make it through the next four years. I knew I never wanted to return to the life I had left behind.

My first nest away from my family was an attic room in a dilapidated rooming house infested with rats. On one occasion I was about to devour a meal of eggs and bacon when I realized the very knife I used to cook my egg and bacon was the same unwashed knife I had employed to lay down rat poison. At that time in my life I had few possessions. I only had one knife. Simple choice: feast or famine. The egg and bacon tasted good, and in the adjacent space the rats were still scurryin g around.

One of my Art School teachers, Dennis Milner, saw my situation and suggested I move in with him and his wife Sarah, a fellow artist, into their two bedroom, third floor flat. What a gift, what generosity. The arrangement lasted for about six months. I don’t think either Dennis or Sarah had realized quite what they had invited into their home, I was not house trained and my basic social ignorance must have been a challenge. But for me it was Happy Land, loving, polite, great food, jazz, lots of fascinating talking, books, and more, it was a wonderful reality. Then one dark damp Manchester night, the bell rang downstairs and I went down to see who was there I opened the door and there stood my mother, she looked Manchester-rain-damp and by her side stood one of her ever odd looking female friends, “I’m pregnant” she said. Shortly after that event I moved into another rooming house.

In the second year students were streamed into studies that suited their talent. My best work was considered to be more in the three dimensional direction rather than graphic design. So in my second year in 1961 I entered the General Design Course, for me a very fortunate title. I graduated in 1964 with distinction and a diploma. This was my get out of the English working class card.

During my summer holidays I worked at various jobs to make money. In 1961 I worked as a porter at the Marks and Spencer department store in Manchester. One of my tasks on Saturdays, when the tills were overflowing with cash, was together with another tall porter to carry suitcases filled with the money from the overflowing tills across the street to the bank on the corner. Our instructions were: “if challenged give up the suit cases and all the seventy five thousand pounds inside them” I thought of my family…

The following summer 1962, I worked at Withington hospital as a porter. It was there that I discovered the power of hypnosis. In the English class order the hospital porter would be some place at the bottom. But in this particular farce I had a College scarf and therefore was marked as being intelligent and from a different class. I felt like a visitor. One of the porters was a highly educated African, Pio Coko. He had come to study psychology in England but had run foul with the system. He was black; both his cheeks had scars that marked him to be the son of a tribal chief. He made amazing claims about the power of hypnosis, embraced me as someone intelligent, and eagerly gave me instructions on how I might practice it. Had I not personally experienced the power of hypnosis I would not have come to appreciate its amazing possibilities.

By 1962 I was runnin g out of steam, I was growing weary of my impoverished situation. Then Harry an old friend of the family came back into my life. My father and his father had both worked nights at Metro Vick's in Trafford Park. At one point earlier in my life we lived in the same street, Howard Street, a bombed Salford street sitting in the shadow of the 'Strangeways' jail. I didn't see him for many years until he found me again in my third year at Salford Art School. At that time I was on the edge of breaking up emoti onally and economically and collapsing back into the quagmire of the violent part of the English industrial working class. A situation that I was desperately trying to escape.

I received a small grant from the Salford Council. It helped but I still had to work nights and weekends as a waiter to fund my Art School studies whilst living alone in various dilapidated rooming houses.

"Come and live in my house for free" said big generous Harry Rowland. Somehow through my broken family connection he had heard of my difficulties and had come to offer me help.

So in 1963 I moved into the attic of Harry's Moss Side rooming house. Set in the middle of Europe's biggest black ghetto. The no rent arrangement had its economic impact but it was the act of someone caring that really helped me over my emotional hump. So now I was in good shape financially. I was going towards my last year at Salford School of Art and Design.

I thought I really needed practical experience, so that summer I offered to work for free in a local design studio, Research Design Company. As luck would have it, Frazer Crane a partner at RDC was generous and agreed to my proposal. The work was primarily in the design of interiors and was run by two partners who were more playboys than business men. Both were from privileged backgrounds and had all the accoutrements of the dashing young designers.

One day I was returning with one of the partners, driving back from a site visit in the partners two seater Lotus. We parked the car on the empty lot behind the old terraced building that housed the design office. I climbed out of the sports car and walked together with the partner towards the rear of the office building, when I saw Ernie Griffiths on a ladder painting the back of the adjacent dilapidated building. “It’s Eric” he said with much surprise in his voice. I quickly acknowledged him, and ran towards the design office door. In part I was afraid that somehow by staying around Ernie I might sink back into the social swamp of busted ladders, rusting gutters and smelly feet that he represented.

During those few years since I had last seen Ernie Griffiths, I had left home, financed my way through my art school studies, made three trips into Europe, marched twice with the campaign for nuclear disarmament from Aldermaston to London, and attended two student union conferences.

In my first year I met the president of the students union, he encouraged me to join the student council as an ordinary member. I clearly remember president Woodall driving me in his jaguar convertible, back to my attic home in a dark and dilapidated rooming house. Curiously, my mother’s maiden name was Woodall and it was my grandfather John Woodall who saved me from my family for those five years.

Looking back I don’t think I was qualified to take on the council rolls of ordinary member, treasurer, vice president and then, in my final year, president. But that did not stop me from trying to do the job.

In my final year thesis I did a study of children in poverty at play. Moss Side had once been a fashionable residential area. Time, changing demographics, and the bombings of the Second World War had left it the least desirable place to live in Manchester.

Yet living there I never felt the fear and anger I felt years later when I was passing through the black ghettos in American cities. I guess the difference was that one set had a history of free immigration, whilst the other had been taken against their will and became slaves with the legal rights of a cow in the field.

What drew my curiosity whilst living in Moss Side, was the responses of the children to dwelling in such an abandoned urban landscape. The ‘crofts’ generally were the platforms for their play.

Open spaces that once had grand terraced houses built on them had been bombed into existence in the wreckage of war.

Abandoned vehicles were often dumped in the crofts. The kids eagerly played with them and gradually took them apart.

Even the abandoned buildings were not immune from such powerful childish activity. Over several months I observed the demolition of an empty house by a small gang of local kids.

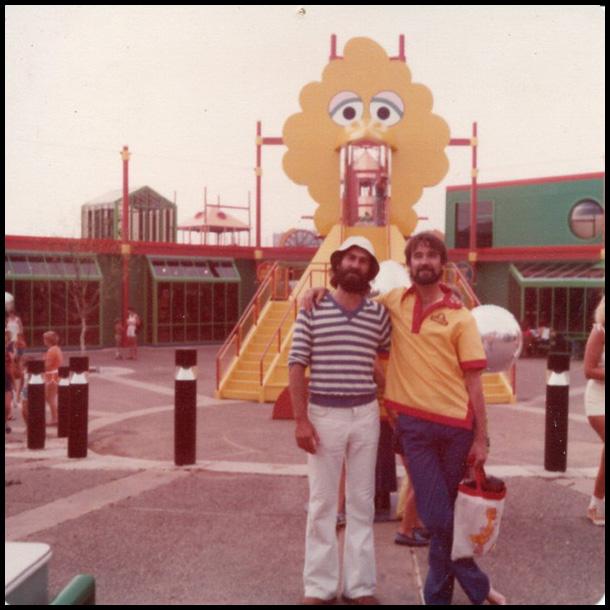

Since that experience I have become an expert on child's play and came to understand the importance of play in broken and busted communities. When we were planning Sesame Place for CTW I suggested to the folks in New York that we build the first one in Harlem, They just laughed at me.

In my final year as President of the Students Union I was looking for a partner to take to my ball, The Presidents Ball. That’s when I fell in love with the miracle lady of my life, Rosemarie Barbara Duell. We had met on a blind date organized by a friend. She was a ‘Bavarian princess’ working as an ‘au pair’ and studying English in Manchester. That’s a student union rented suit I am wearing.

Without Rose’s steadying influence I would have crashed my very early design career. My first job out of art school was a dream job: Senior Exhibition Designer. David Kerslake, who hired me, was a fantastic boss. He allowed creativity to flourish and was kind to me and Rose personally.

At one point I was irritated with him over some minor issue, so when I was leaving for my next job, I informed Rose I planned to give him a good beating before I left. Well, Rose being the wise one persuaded me into not implementing my plan. It’s hard to believe that such primitive behaviour still haunted me; it was the habit of my family.

Eric McMillan biography, 1964 to 1968

The shaping of my mind, the influence of others, and the circumstances of my reality all that changed when Rosemarie Barbara Duell entered my life. I was at that time in desperate need of stability. Having the love and devotion of another being, made my emotional life easier. Her wise, civilized, and educated view ensured that I didn’t fail. I went from living alone in an abandoned house in damp Manchester’s black ghetto, Moss Side, to living on the edge of a forest. Knole Park, one of Anne Boleyn’s hang-outs was just up the road with its herds of deer.

We moved from the dark Industrial North, to the clean sunny Kent, the garden of England in the South. I was lucky to find a magical place for our first home, a four bed room furnished flat, above the estate’s worker cottages.

When Rose and I first met our landlord, Sir Russell Vic, we were a newly married couple; Rose, a German student had only spent six months in England learning English, whilst I the man in charge with the thick Northern accent was born in Sheffield. It was during the discussion with Sir Russell Vic, relating to renting the flat that I realized Rose was often translating what I was saying to him. It reminded me of my class and my branded tongue.

When Rose came into my life I had few clothes and all were well worn. My favorite coat was a corduroy jacket, with its buttons chewed by a pup I once had, as well as the occasional art school ink stains. Clothing can build and unbuild confidence. I learnt that lesson as a ten year old child in rags: only a few of the children in the street where I lived were permitted to play with me.

But now in 1964, as an ambitious designer in the 1960's, clothing was my uniform. But the purchase of such a custom made item was out of my financial range. Then Rose came to the rescue. As a dress designer she had to know how to sew. So Rose went out, bought a sewing machine, measured me, made a pattern, and finished this marvelous suit with a little hand stitching. That was the light grey suit. After that she made me others over the next eight years. It was quality time, I never again felt insecure about my clothing. I was the best dressed designer I knew. That’s me and my young sister at Victoria’s monument. I’m wearing my Rosie-made designer suit

The Marley Tile job as Senior Exhibition designer was a bit of a challenge, but what a lucky break. I still don’t quite understand why David Kerslake the head of the design department selected me for the job. I guess my ‘veil’ was activated again. I was treated well and given great work. Marley Tile was my first significant break into the world of design with such creative freedom.

For me the pleasure came when the projects were built: show rooms, furniture, exhibitions, and finally at the 1965 National Building Exhibition.

Traditionally Marley Tile had built a full scale Oast House to house the exhibit of their products. But to show their products in 1965 they needed more exhibit space. I persuaded them to float a real twenty four ton authentic Oast House on an exhibition pedestal I had designed. All that effort just for the ten days of the International Building Exhibition. During that time I was given much creative freedom but somewhere in my soul there appears to be a wandering spirit seeking greater ambition and purpose

The Central Office of Information in London had at that time the best exhibit design unit in England. They advertised a vacancy that I understood to be that of an exhibition designer. I eagerly went for the interview with my portfolio of work which I presented to the examining board. I was offered the job, I gave my notice to Marley and a few weeks later turned up to what I expected to be a studio job. To my complete surprise it was not a design position but a junior management job of a government exhibition department. I was desperate I wanted to design I didn’t have bureaucratic ambitions. In my panic I thought that my design career was over.

It was during that time I found myself locked in an office with my boss, Cliff Seymour. A guy from Lancashire who had once worked in the cotton mills, ‘a man who could talk a glass eye to sleep’. Just for a break, to avoid his constant chatter I pretended telephone conversations with no one on the other end of the line, except the silence of my boss. Looking back I think I was selected for the job not for my design skills, but because of my Northern accent. Cliff Seymour my boss was quite old and had serious health issues. The selection board hearing that I spoke with the same Northern working class accent thought I might be good company for Cliff. Fortunately that COI madness lasted only three months, before I was able to obtain a real design job. The whole event sits in my memory as a bizarre bureaucratic event.

It was sheer luck to get the job at the Electrical Development Association as Exhibit Designer. The design studio window looked over Trafalgar Square and beyond Nelson’s Column I could see the National Art Gallery where I could take in a lunch-time-lecture. My street number was Number One Charing Cross. I had been in Trafalgar Square five years earlier in 1960. It was at the end of marching from Aldermaston to London with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) that I heard Bertrand Russell speak standing between Lanseer’s lions guarding Nelson’s column.

My boss at EDA Norman Philips was a cigar smoking English eccentric. He dashed in an out of the design studio like some cloaked wizard, giving the design brief for some project and then disappearing again into London's club land. He taught me a lot about building a three dimensional story. I worked with him on the ‘Half a Man’s Lifetime - 1927-1957’ exhibit at the 1965 School Boys and Girls exhibition. He really tried to nurture my talent. In the School Boys and Girls exhibition, we asked the children to imagine their father was born 1927, and what amazing electrical progress had since taken place. The children were taken in groups through a series of animated historical exhibit performances, starting in 1927 through to 1937, 1947, and 1957. The exhibit was a great success and Philips applauded my effort by giving me a mickey of the very finest whisky when the exhibit opened.

At EDA I was given great work, but the challenge to survive financially as a family on twenty pounds a week started to come into play , as well as the long daily commute from Seal to London and then back again. I was spending four hours a day commuting. By the time the Brighton commuter train arrived at Sevenoaks station it was stuffed full like a cattle truck, with bowler hatted business men all clinging to their damp umbrellas. There was standing room only for those boarding in Sevenoaks. I was fortunate I finished my transit journey at Charring Cross railway station; others had to go underground and take the Tube to get to their work.

On the EDA exhibit for the 1966 Electrical Engineers Exhibition I met Ken Young, the designer of the Canadian exhibit. He was impressed by my work and spoke with great enthusiasm of the design work at Expo 67. He encouraged me to send a copy of my resume to the head of design at the Canadian Government Exhibition Commission in Ottawa. I did receive a response, it was: ‘if you happen to be in Ottawa we will give you an interview’ which given my position then was like inviting me to an interview on the dark side of the moon. But the idea of working on Expo 67 began to ferment; I was growing weary at the prospect of spending years commuting in crowded railway carriages.

I was slipping again into my time-to-move-on -mood. I have never been stable in my employment. Eighteen months was the longest I lasted at any job, always eager to find another color in the rainbow of my creativity. It is a pattern that echoes my early childhood: forever moving, nine schools in ten years up to the age of fifteen.

I found a job advertised for an exhibition designer in Montreal. It was in an obscure magazine ‘Display’ whose main clientele were involved in window displays. I sent off my portfolio. Initially the two brothers who ran De Nova thought me to be overqualified. The person they selected at first insisted they pay his travel expenses to Canada. The brothers refused. They then started their search over again looking through the fifty applications they had received for the job. At the bottom of the pile they found my portfolio and decided to offer me the job. I arrived in Montréal on December 12th 1966. The climatic change was a challenge, having just come from swinging London I was wearing my designer raincoat. I was not prepared to deal with Montreal's 35c below weather, with its howling winter winds dashing down the frozen St. Lawrence

The propaganda of Montréal being the Paris of North America was a bit of a disappointment. I found it to be dirty, provincial and unfriendly. But my job was my greatest disappointment. I was not doing any work on Expo 67, but was employed in coming up with speculative designs, that the salesman would then try to sell. It wasn't working, my confidence as a designer was beginning to melt, I was not used to such speculative ego crushing activity, and I seriously considered returning to England.

Then I remembered the offer of an Ottawa interview at the CGEC exhibition design office. One Saturday morning I traveled up from Montréal by train arriving at Ottawa's new railway station, had my interview in the afternoon and some days later I received a letter dated April 13th 1967, my birthday, offering me a job as exhibit designer in the Canadian division of the Canadian Government Exhibition Commission. It was a life raft for me and my design career. Ottawa in 1967 was an amazing place it was at that time the most magical of places to work and live.

Ottawa in 1967 was the capital in the wilderness. Bank Street, its main North/South Route was a dirt road. The Performing Arts Center shared its stage with the local strip joint. One lunch time a group from the studio decided to go for a swim in the Ottawa River. Even though I could barely swim I joined in and nearly drowned. I can still remember clearly the moment I decided it was easier to drown. Fortunately my fellow designers held me up until the lifeguards could come and do their work. The veil appears to have kicked in again.

The studio work was great and the fabrication shop was full of gifted craftsmen. In 1968 Ken Young came back into my life, he was working on the Ontario Pavilion at Expo 70 in Osaka and informed me that the design group he worked for, Stewart and Morrison, were looking for designers to work on a permanent Toronto attraction inspired by Montreal's Expo 67 .

Eric McMillan biography, 1968 to 1974

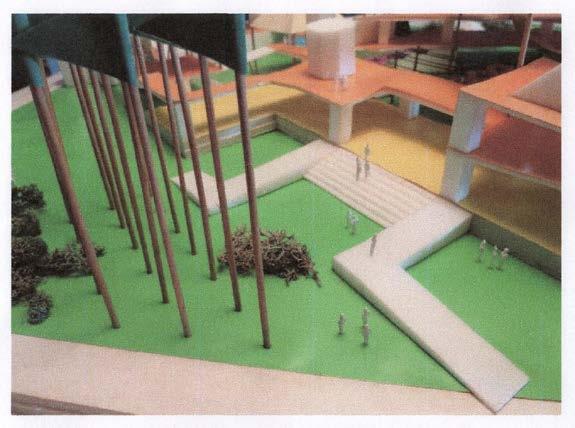

In the four years since leaving Art school, from 1964 to 1968, I had worked in six studios, all filled with creative challenge. But of them all Ontario Place was my journey into a much wider horizon, what became for me an Aladdin's cave of creativity.

Ontario Place had an interesting start because to begin with nobody had a clear idea of what the project was, other than being inspired by the wonderful reaction of the thirty three million people who attended Montreal’s World’s Fair Expo 67. Being there in 1967 as an exhibit designer was great but the positive energy that flooded the Expo site was both rare and wonderful. Mayor Jean Drapeau did a great job.

The Ontario Pavilion was a hit with its Oscar winning movie, Chris Chapman's ‘A Place to Stand’. There is a legend of Ontario premier John Robarts visiting Expo 67 in Montreal and crying to Jim Ramsay responsible for the successful Ontario Pavilion ''Why can’t we do something like this?'' and Ramsey replied ''We can''.

Had Ontario Place succeeded as planned, Toronto would have become the Venice of North America with the building of Harbor City. The corner stone of that project was Ontario Place.

When I first joined the OP-71 team in 1968 I designed its symbol and alphabet. It all felt quite revolutionary. The population was transforming itself; we had gone to the moon.

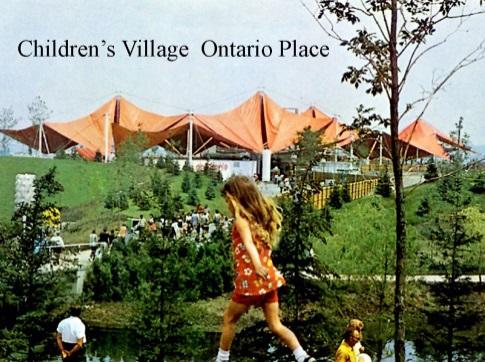

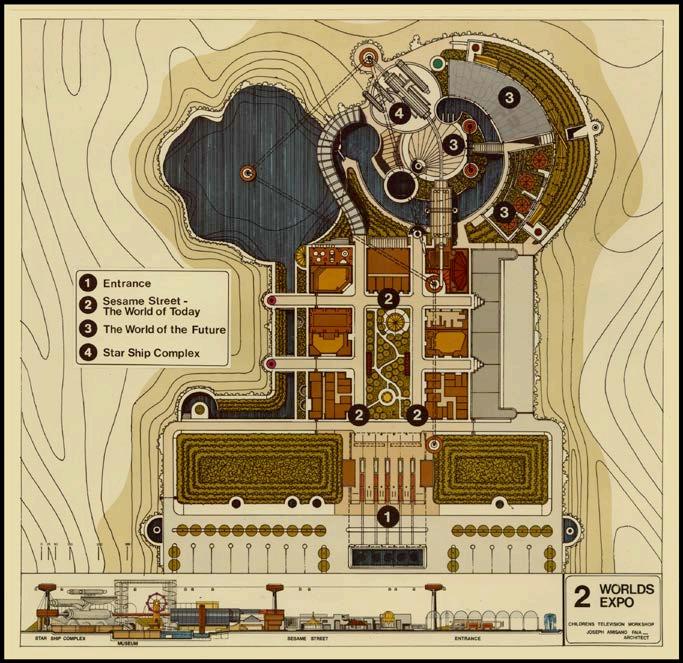

Ontario Place________________________________________________________________

The original plan was a modest redo of the existing Ontario Government pavilion at the CNE. But it quickly became a more ambitious plan when Noel Hancock the project architect proposed we build the exhibition pods in the lake. At first there were to be seven exhibition pods providing a circular traffic pattern.

That was early in the project’s development. Because of cost considerations the exhibition pods were reduced from seven to five which proved disorienting from a visitor’s point of view, who at the end of the exhibition experience found themselves dumped into a foreign landscape.

Another significant design change was the relocation of the support columns. The brief we exhibition designers gave to the architects was for an empty, dark square box 80ft x 80ft, with 20ft ceiling. And that was what we were given in the early design development with the supporting columns in the corners of each pod. But for some absurd architectural gift shop thinking that plan changed. The four columns supporting the exhibition pods were relocated from the corners into the middle of the dark box. It was like trying to fit a body into a coffin with four columns driven through its middle. It was at this time my faith in the gods of architecture began to diminish.

Despite that architectural challenge my design for pod 3 ‘Explosions’ was the most successful exhibit when Ontario place opened in 1971.

Ramsey was certainly a key player in the course of my fate; he was a very intimidating person with a great nose for creative talent. I remember when I first ran the Explosions exhibit, it was a preview performance. Ramsey and some other high ranking official then found themselves in a forest. The amazingly complex exhibit worked like clockwork, objects appearing then disappearing, phantoms moving through space and time, the telling of a three-hundred-year story in ten minutes. Explosions was the most elaborate audio visual experience ever built.

It was to my complete surprise that Ramsey, the head man from Special Projects, the Government agency responsible for the development and construction of Ontario Place, selected me to run the Design Unit after Ontario Place opened to the public in May of 1971.