the shahjahanabad map

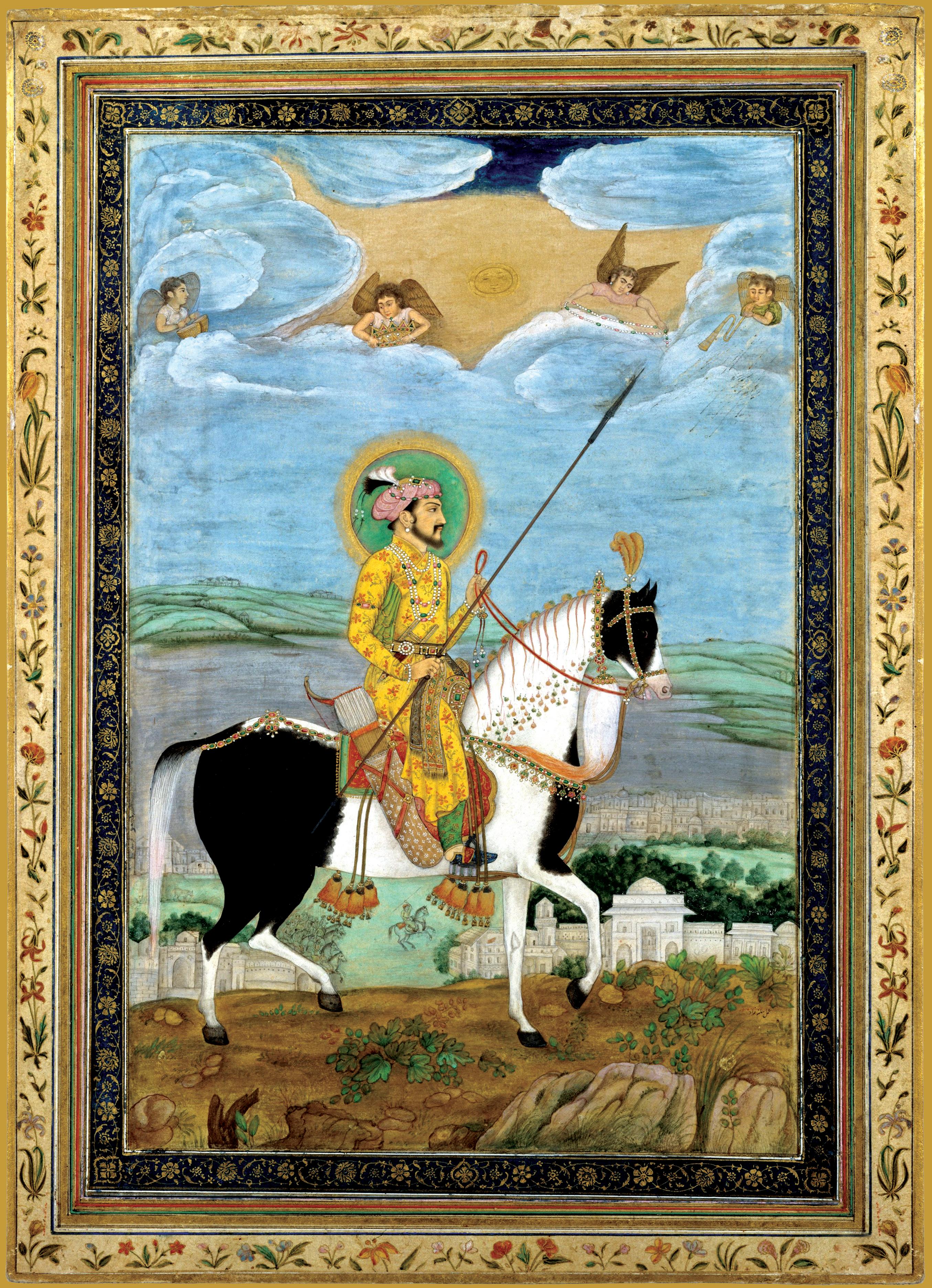

frontispiece: portrait of mughal emperor shahjahan on horseback.

As a curator and publisher I owe this book to J.P. Losty. Between us, there was always a book in progress and excitement of projects in the future, few of them at stages beyond discussion.

S hahjahanabad: Mapping a Mughal City was one of them. My last email to Jerry requesting an introduction to this book remained in my outbox waiting for the attachment for him to review. Alas, that is where it remained. Sadly, a few days later we got the news that Jerry had left us forever.

As a mark of our friendship s hahjahanabad: Mapping a Mughal City is dedicated to him.

p ramod k apoor

acknowledgements

WhenPramod kapoor suggested that i undertake the writing of a detailed analysis of this very important historic map of shahjahanabad, two factors emboldened me to take up the challenge. one was some knowledge of shahjahanabad as it was during the period of the east india Company, when this map was made. This knowledge was the direct result of a Phd at Jamia Millia islamia. The second was a familiarity with the streets and landmarks of shahjahanabad today, which in many ways has not changed much over the last two centuries. This familiarity is the result of personal explorations that were carried out in the process of conducting heritage walks for the india Habitat Centre and the indian national Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage. For this reason, i owe thanks to those who made my Phd possible, as also those who have made the walking tours possible, and/or accompanied me on them. They are too numerous to name individually, but i am grateful to them all.

i have specific reason to be grateful for the opportunity i had to contribute to the editing of a translation of sangin Beg’s Sair-ul-Manazil, by Tulika Books. This nineteenth-century text in many ways gave me an insight into how a person living in the nineteenth century would have viewed the city, and thus provided valuable context to understanding the nineteenthcentury city.

Finally i must thank roli Books, not only Pramod kapoor, whose idea it was, and who as always has brought his discerning curatorial eye to bear on the illustrations included in it, but the whole team, particularly sneha Pamneja, neelam narula, Jyoti dey and Bhagirath kumar, for their patience and painstaking attention to many minute details that this book required.

swapna liddle

the shahjahanabad map 1846-47

A Historical and Contextual Background

The Mughal emperor shahjahan founded the city of shahjahanabad in the mid-seventeenth century as his capital. The city was located close to a cluster of older sites, at delhi. There were several reasons for the selection of delhi as the capital. To begin with, there was an imperial aura, a long history of the city as a capital of empires. This dated from the earliest conquest of delhi by the Turks, in the late twelfth century, and the subsequent establishment of the delhi sultanate. The early Mughal emperors, Humayun and Akbar, had also ruled from delhi, though the latter had soon moved the capital to Agra. Apart from the imperial aura, delhi had a spiritual aura as well, as the seat of several sufi saints, most notably Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar kaki, nizamuddin Auliya, and nasiruddin Mahmud Chiragh-edehli, many of whom the Mughals revered. The Hindu subjects of the Mughal emperor associated the site with the ancient city of indraprastha, connected with events mentioned in ancient texts, including the Mahabharata.

shahjahanabad was a planned city, the only living, planned, Mughal city extant in largely its original form. encircled by a city wall, it was situated on the bank of the river Yamuna. The citadel housing the emperor and the royal family (officially named Qila-e-Moalla, ‘the exalted fort’, but today known as the red Fort) was an important focal point of the city, and the congregational mosque, the Jama Masjid, was the next most prominent landmark. The two main streets led from the Qila – one westwards and the other southwards. These ceremonial avenues were lined with trees and provided with a channel of water that flowed down the middle. some older road alignments were also preserved, particularly a diagonal axis that ran from the middle of the western stretch to the middle of the southern stretch of the wall of the city. The city included large gardens and channels of water, fed by a canal that brought water into the city from the Yamuna further upstream.

Apart from these landmarks, which were a result of imperial planning, the city contained the homes of its diverse population, and a variety of commercial and religious spaces. The amirs (nobles) built their grand mansions, which housed their extended households, including

shahjahan 1592–1666

shahjahan came to the throne in 1628 in Agra, and built on the legacy of his forefathers to create an empire that was one of the most extensive and prosperous of all time. He chose to devote the choicest resources and best talents of the land to the creation of masterpieces of architecture, and ultimately to a city that would rival the most celebrated cities of the world – shahjahanabad.

large entourages of retainers.Traders and artisans built more modest homes and workplaces, in localities which often housed others of their trade. specialist markets – bazaars, developed along the streets, or in enclosed spaces called katras. Places of worship – mosques and temples, were built, usually by individual patrons, though sometimes by community effort.

shahjahanabad remained the seat of the Mughal royal family for more than two centuries after its foundation, and important changes took place in the city during this period. Political upheavals associated with the decline of the Mughal empire, such as civil war between various factions within the Mughal nobility, and invasions, were crises that caused considerable human suffering and loss of property. They also led to some long-term changes in the structure of the city. There were sharp fluctuations in the fortunes of various amirs, and as a result some of the large estates declined. in general, the density of built-up area increased, both in the fort, as the royal family increased in numbers, and in the city, where many of the larger estates were subdivided into numerous smaller plots.

Construction was not the only way in which each era of the city’s history left its mark. For instance, in the late eighteenth century, the Marathas became the rulers of the city for a number of years. The legacy of that era was reflected in the numerous place names ending with ‘wara’ – Maliwara, Jogiwara, etc.

in 1803, shahjahanabad and the territory around it came under the control of the British east india Company.The Company became the de facto ruler of the city, while the emperor and the royal family continued to live in the palace complex, the Qila. The late eighteenth century had been a period of disorders and war in north india.With the British vanquishing most of the other powers by the beginning of the nineteenth century, peace descended. This led to a spurt of construction in the city, as well as greater attention to civic infrastructure, which had deteriorated in the previous years. The channel of water that ran down the two main streets and the gardens, was restored. The trees by the sides of the streets that had died, were replaced. The British also brought new styles of architecture and contributed a new layer of landmarks to the city.

The historical map shows in great detail what existed in the city in the 1840s. This picture was drastically altered in the years immediately after the revolt of 1857. large areas were almost completely cleared of buildings. The demolitions took place in and around the red Fort for security reasons; in Chandni Chowk and dariyaganj after the confiscation of royal and other properties, and in the northern part of the city for the railways.

The areas of demolition are shown as shaded portions in the overlay, with the few buildings that were preserved, marked with red dots and labelled as follows:

1. mosQue in salimgarh

2. baoli

3. bhadon

4. sawan

5. moti masjid

6. shah burj

7. hira mahal

8. hammam

9. diwan-e-khas

10. tasbih khana

11. rang mahal

12. mumtaz mahal

13. diwan-e-aam

14. naQQar khana

15. chhatta bazaar

16. baghichi madho das

17. gauri shankar mandir

18. digambar jain lal mandir

19. grave of syed bhure shah

20. grave of shah kalimullah jahanabadi

21. sunehri masjid

22. dargah sabir baksh

23. zinat-ul-masajid

important landmarks that came up after the demolitions have been marked with black dots:

1. colonial barracks

2. colonial army buildings

3. st. mary’s church

4. st stephen’s college (old building)

5. old delhi railway station

6. st stephen’s church

7. gadodia market

8. haveli chunna mal

9. town hall

10. nai sarak

11. hardayal public library (hardinge public library)

12. northbrook fountain (phawwara)

13. central baptist church

14. state bank of india

15. esplanade road

16. indraprastha school

17. anglo sanskrit victoria jubilee school

18. shroff’s charity eye hospital

19. holy trinity church

f aiz b azaar

The area called Faiz Bazaar when this map was made, is now better known to us as dariyaganj. The thana limits are quite extensive, as it spreads out from just south of the Qila, to the southernmost gate of the city, that is, dehli darwaza. its east to west spread is from the bank of the Yamuna westward to its boundaries with two other thanas – Turkman darwaza and Bhojla Pahadi. The thana gets its name from Faiz Bazaar, the broad street running between the dehli darwaza of the fort to the dehli darwaza of the city. This was one of the two main streets of shahjahan’s city, the other being the east-west avenue leading from the fort’s western gateway. in the map itself, the road is labelled guzar dehli darwaza (151). Faiz Bazaar had a channel of water running down the middle of the street, but by the time this map was made, there was no water in this channel. Faiz Bazaar is shown in the map as having two squares. one of them, which makes up kashmiri katra, is outside the thana limits. The other is shown half-way down the street, marked Phool ki Mandi (152), the ‘flower market’. in the middle of the square is a pool, which would have at one time contained water. By the mid-nineteenth century, not only was there no water in the channel or the pool, the flower market too had stopped functioning, though the name had survived. other landmarks on the main street include what is simply marked as Masjid (153), but is clearly the third sunehri Masjid of the city. This was the mosque built in 1744–45 by roshan-ud-daula Zafar khan, a nobleman. The gilt domes that gave the mosque its popular name, had disappeared by the time the map was made, and therefore it is shown without domes. next to the mosque is a large space designated sabir Baksh sarai (154) (the inn of sabir Baksh). shah sabir Baksh was a sufi saint who died in 1837. Close by, on the other side of the main street, sabir Baksh had built a complex including his khanqah or abode, a mosque and a musafirkhana, or guest house. This area is marked slightly differently in the map, which shows a kucha and a bagh named after the saint. in the area of this thana that borders the thana Turkman darwaza, we see a place marked Hauz Meer khan (155).This was no doubt part of the estate of Meer khan Chaghta, a noble of the reign of Mohammad shah, whose ganj was close to the khidki Meer khan in the neighbouring Turkman darwaza thana. Meer khan’s estate in earlier times was likely to have been even more extensive, because the main street too is named Bazaar Meer khan (156). not far from the Hauz of Meer khan, is dukan Banswala kewal (157), ‘the shop of kewal

tiraha bairam khan

This tiraha, or junction of three streets, was probably named after an early eighteenth-century noble of that name. The house of syed Ahmad khan, the reformer, was also located nearby. 159

175

masjid and kothi kala mahal

This extensive property belonged to the nawabs of Pataudi and Jhajjar.

173

kothi and bagh shamsuddin khan

The estate of the nawab of Firozpur Jhirka and loharu, nawab Ahmad Baksh khan. it later passed to his son shamsuddin khan, who was convicted of plotting the assassination of William Fraser, and hanged.

174

kothi jhajjar wale nawab

This was the estate of the nawab of Jhajjar, the ruler of one of the many principalities around delhi, who had bought property in delhi.

1840.

the bamboo seller’. Part of kewal’s property was also located in the limits of the thana Turkman darwaza.

Also in this part of the thana is the Haveli nawab Bangash (158), known in other sources also as Bangash ka kamra. The Bangash nawabs had risen in the eighteenth century from service of the Mughal empire, to being independent rulers of the territory of Farrukhabad. The founder of the family fortunes was Mohammad khan Bangash, who lived during the reign of Mohammad shah, and had been the governor of Farrukhabad, Agra, and Allahabad. like many other officers of the Mughal empire, however, he too built up a landed estate in delhi. After his death, his widow, rabia Begum, stationed her trusted agent, Faizullah khan Bangash, in

delhi to look after her interests at the Mughal court and manage the estate there. The lady took a keen interest in architecture, and Faizullah khan was also her superintendent of buildings. in that capacity he supervised the construction of several buildings on her behalf in delhi. it is said that this haveli had been built by him with a large sum of money.

An important landmark within this thana is the Tiraha Bairam khan (159), a junction of three streets. The name no doubt came from the nearby property of Bairam khan which is shown in the map as Baradari nawab Bairam khan (160), (baradari meaning pavilion). Though Zafar Hasan relates this to a descendant of the famous Bairam khan, a powerful noble of the era of Humayun and