Paul michael taylor

The Smithsonian’s Asian Cultural History Program, together with Roli Books (New Delhi), is pleased to present An Empire Speaks: Kavya Narratives of India’s Cultural History – a new historical and poetic work, written in English in the form of “kavya” or poems. “Kavya” (or kavya) is the Sanskrit term used to refer to a style of poetry which emerged from South Asia, possibly over two thousand years ago, and was a fully developed poetic form by about 700 AD.1 Kavya poetry often uses seemingly roundabout figures of speech or syntax or employs a seemingly ostentatious erudition to tell well-known tales derived from popular ancient epics or other traditional subject-matters. The poems are often interconnected in theme and may collectively imply a narrative from beginning to end; and yet each is a separate and rather short poem, though often presenting vignettes from the long epic poetry of the region such as the Mahabharata or Ramayana. Using varied metrics and sometimes a bit of hyperbole in recounting history, the kavya have long been a popular form of poetry for recounting episodes from epics or transforming historic events into something of similar gravitas.2 Early forms were told and written in Sanskrit, but over time the kavya poetry format spread to all the myriad other major literary languages of India, and even eastward to Indonesia.3

A well-known cardiologist, writer, and poet, Dr. Rupinder S. Brar has recognized that English is the newest entrant to the long list of major South Asian languages, so

it is logical that the great mythical and historical events of South Asia should be recounted in English – and why not also in the kavya poetic format? The kavya narratives in this book reflect some of South Asia’s on-going transformations. First, of course, is that these kavya are in English, now a major language of South Asia (more speakers of English reside there than in England). Second, they continue the narrative of South Asian history beyond the Indian subcontinent, through the kavya in Part Five, “Diasporic Reflections,” stories from South Asia’s diasporic communities.

The book’s title “An Empire Speaks” references the expression Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in reaction to his readings of the Bhagavad Gita, that in reading this he feels that “In the great books of India, an empire spoke to us, nothing small or unworthy, but large, serene, consistent, the voice of an old intelligence, which in another age and climate had pondered and thus disposed of the questions that exercise us.”4

An Empire Speaks: Kavya Narratives of India’s Cultural History is the second book by Dr. Brar that the Smithsonian’s Asian Cultural History Program, working with Roli Books in India, have published. The first was The Japji of Guru Nanak: A New Translation with Commentary, 5 which offered a new translation and analysis of the Japji, the best-known work of Guru Nanak, the first Sikh Guru and founder of the Sikh faith. The Japji constitutes the initial first

In the great books of India, an empire spoke to us, nothing small or unworthy, but large, serene, consistent, the voice of an old intelligence, which in another age and climate had pondered and thus disposed of the questions that exercise us.

R ALPH WALDO E MERSON Journal VII, October 1st, 1848

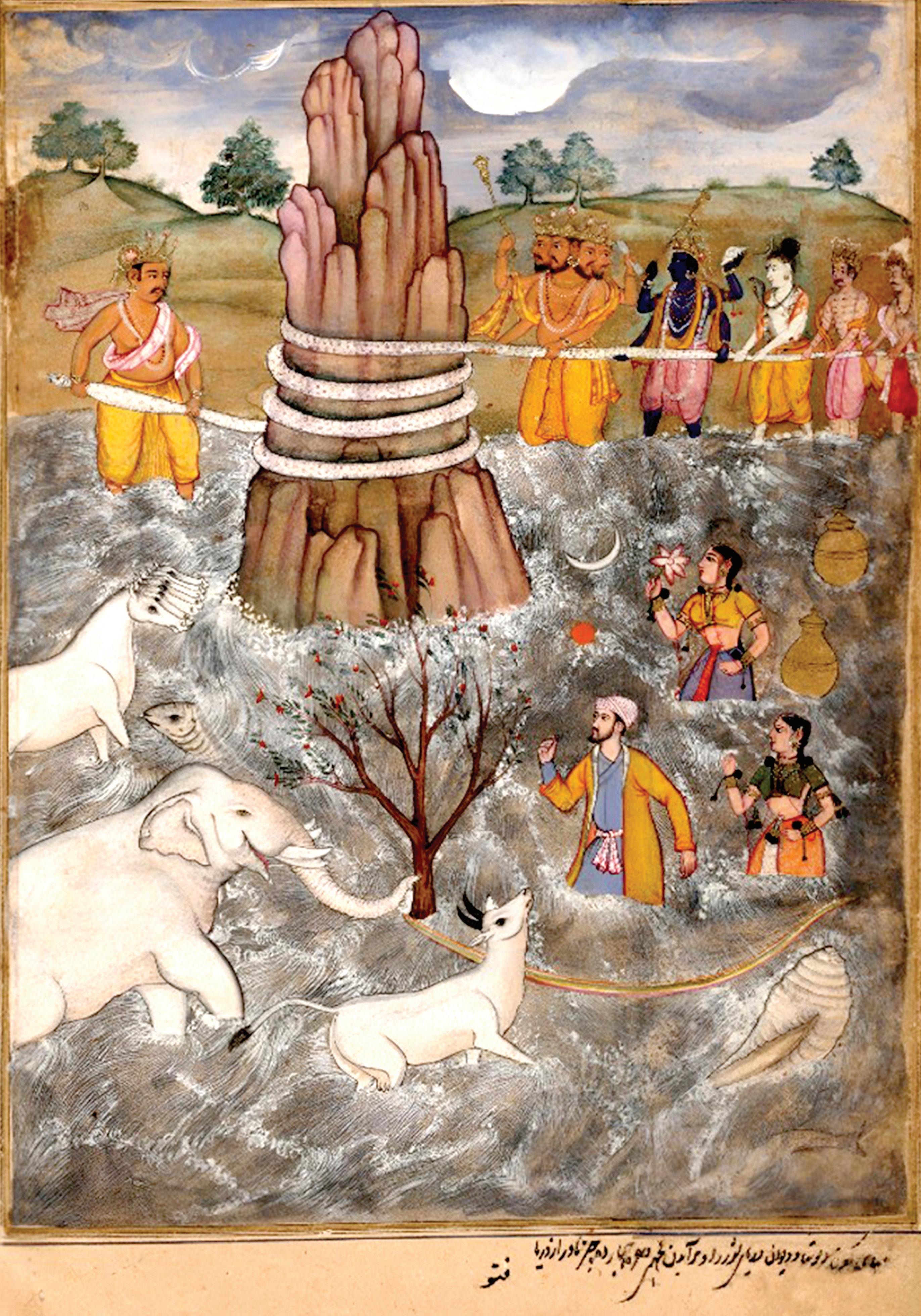

The Gods and Asuras Churn the Ocean of Milk Page from a dispersed Razmnama (Book of War) | ca. 1598-99 Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department, mcom00151

Head bowed, shoulders stooped, sat the blindfolded queen Gandhari, Amidst guts and heads, arms and legs, shattered bodies, scattered remains, that were once, her hundred valiant sons.

Suddenly she sensed, Krishna’s presence, man amongst men, the God among the gods. Grief became defiance, briefly she turned, something snapped and abruptly she asked:

“Lord; they call you—Savior, Protector. What kind of savior sits to watch, men devour men, a world torn apart? Elysian sport—Kurukshetra’s bloodbath.

Omnipotent if you be, then not caring, for no loving god lets such evil win. If willing you were, but unable to stop, then imposter you are, not a god. If both loving and willing, then where from came such villainy?

Beheld Krishna, in her face, an aching heart, a sad, lonely place. A mother’s price for son’s vice—pride and war. Softly he approached, kindly he spoke: “Sons you lost, your woe is plain, my queen, yours is a mother’s pain.”

But consider then, if you must, an adoring father’s angst. The one who creates and dissipates, a hundreds thousands sons, and hundreds of thousand times. Shouldn’t such misery also be mine?

Obsessed with dogma, of caste, purity, and pollution, most putrid words ever spoken, came from a Brahmin’s tongue; “Eklavya, give me your thumb.”

A land fixated on sanctity, forgot its security—and lost both. Five words, crippled a warrior, and a civilization stood exposed.

Inky dark dripped the Nishada blood, blotted it out the Arya future. Each drop became a name, for a millennia long shame; Somnath, Talikota, and Panipat.

Came along others to tap, into long neglected veins, of India’s valorous sap. At Koregaon, to hold account, for Eklavya’s thumb.

Five hundred Mahars, backed by few British guns, shattered a host that was once, twenty-eight thousand strong.

Crimson turned the field, mingled Sudra blood with the Brahmin, now blood brothers in death. Returned home the warriors, to the sole arbitrator of their valor, their common mother, Bharat Varash.

No, I never did, for a moment desire to save my neck at the cost of my (dis)belief.

Belief is easy, it softens the hardships, even makes them pleasant. For in God, man finds both consolation and support.

Without Him one has to depend only upon oneself. Upon one’s own two legs one must learn to stand, amid hurricanes and storms.

I know the moment a rope is fitted around my neck and removed are the rafters, that will be the final moment. Finished will be my entire being, or the soul to be precise, as understood by theology.

My fate I know is already settled, within a week, I will be gone. What consolation have I, except the thought that mine was a sacrifice, for the cause of humanity?

Three homelands I claim, in the name of generations three. The first is my birthplace, the second that of my offspring, the third, where once thrived, my kin and forefathers.

First homeland is my birthright. The second is by choice, my adopted land. The third is an Eden unseen, where perhaps, I am still— a persona non grata. It is complicated.

My birthplace is a land of ancient peoples, many beliefs. Among them, that sacred and profane, are one and the same. That permeates within all, the same Divine being.

That tolerance is strength, not a mark of the weak. That wind is teacher, father is water, that Earth is mother of us all, not a domain of a few.

Born in my second homeland, are my children. A land that taught, that Sovereign is the self, and freedom a birthright.

A shining city on the hill, an inspiration for many, even though many a time, its own ideals it defies.