a h istory of g lassmaking in i ndia

tara DesjarDins

tara DesjarDins

This publication, a culmination of over a decade of research, amalgamates scientific studies, chemical analyses, primary accounts, archival records, and art historical practices. Its dual purpose is to establish a coherent literature where none existed before, and to craft a comprehensive catalog of objects.

The history of Indian glass is, in fact, two histories: that of glass’ evolution within the history of glass production, and the other, the history of the Indian subcontinent during the early modern period. The first explores the experimentation of glass recipes and how these impacted production and industry, while the other examines the greater sociopolitical transformation of Mughal India during the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. Both histories develop in parallel until they collide at precisely the point where the development of new glass mixtures, the importation of foreign goods, and the increase in European hegemony in India intersects with the decline in Mughal power, the rise in concentrated wealth circulating around autonomous courts, and the development of a new class of wealthy individuals eager to commission and consume glass.

Prior to embarking on this subject, very little had been written on glass from Mughal India with even less documented in the primary sources dated to the period. Early Mughal chronicles such as the Āīn-e Akbarī (the Institutes of Akbar) attest to the existence of glass in several North Indian provinces, while contemporaneous accounts from East India Company ledgers confirm English glass

imports into India. Both records substantiate the circulation of glass within Mughal provinces and courts during the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, these sources remain silent on details such as techniques and traditions of glass working, or the scale and function of any industry. No further mention of glass production has been found in any other Mughal chronicles compiled between the reigns of emperors Akbar and Alamgir (1556–1707). In the eighteenth century, India Office Records – a collection of documents relating to the administration of India from 1600 to 1947 – begin to mention the import of English glass (cullet, lump glass, and ingots) in the private papers of British East India Company officers arriving into the Bay of Bengal and Madras (modern-day Chennai). It is only a century later, in 1807, however, that the earliest known description of glassblowing emerges from a British Industrial Survey.1 This account describes the use of recycled European glass in the manufacture of blown glass vessels in Patna city, Bihar, a practice which, by the late nineteenth century, had become widespread across much of northern India in the Hoshiarpur districts of the Punjab, the United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh), Madras, the Bombay Presidency (now Gujarat and the western two-thirds of Maharashtra), and Bengal.2

Several scholars have helped pave the way for the study of glass in Mughal India – the most notable amongst these being Moreshwar Dikshit, Simon Digby, Robert Skelton, Stephen Markel, and Stefano Carboni. Much of their research has formed the foundation upon which other scholars have since based their assertions and arguments. The vast majority of secondary scholarship written in the second half of the twentieth century, however, postulated that glass from Mughal India merely

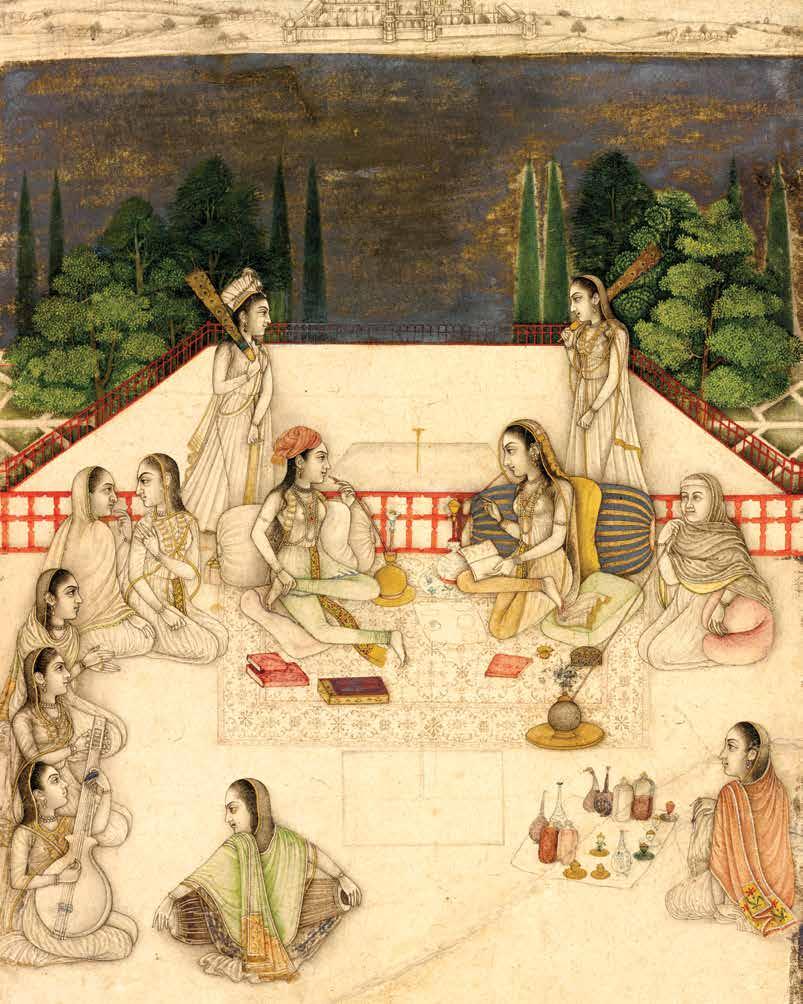

FIG. 3: A GARDEN GATHERING by Bichitr Mughal, ca. 1615–1620 | Opaque watercolor and gold on paper | Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (CBL In 07A.7)

With very few primary sources detailing glass production during the eighteenth century, assigning the objects in this Catalog to a specific place, let alone a region, becomes nearly impossible. Given this lack of vital information, only an imperfect or impartial picture of glass production can be constructed. The strongest sources remain those dated to the early Mughal period, in particular the Āīn-e Akbarī, yet this is recorded centuries before the dating of our objects, and certainly well before the creation of an English ‘potash-lead’ glass mixture made in the late seventeenth century. Whether further records exist in the archives of regional courts, or in the ledgers of one of the many East India Companies (in particular the Dutch) remains to be discovered.

As a result, the most effective method for determining both date and provenance combines three distinct classifications: glass composition, object shape, and decoration. The first explores the chemical composition of the glass, identifying certain families or schools of glass which can help to localize production. The second is object shape, which traces the history of shapes as a means of assigning place of production, such as ‘case’ bottles and huqqa bases, for example (object shapes will be explored in more detail within individual catalog entries). The third is decoration, which alone encompasses three individual components: technique, style, and image. The technical aspect of decoration falls under glass working traditions (discussed in more detail in ‘Glass Working’.). Both style and image, however, represent patterns, motifs, and imagery depicted on the objects.

In many ways, this serves as the most evident method for identifying the objects as Indian, even though linking the decorations to a specific painting school remains challenging. Nonetheless, examining both style and imagery represents an important means for identifying place of production and date, especially when compared to paintings or works on paper.

Another means of establishing dating is through provenance. Almost half of the objects in the Catalog currently remain in collections outside of India. Those in India have minimal detail regarding their provenance; at best, inventory records date back to the past fifty years. Conversely, provenance records in institutional collections in Europe have a much longer recorded history, the oldest being the British Museum. Examining when objects entered into museum collections has provided another lens into which these objects can be studied and understood. It has also, in turn, allowed for an entire group of stylistically similar objects to be more accurately and firmly dated.

The greatest contribution furthering our understanding of these objects has been through scientific studies and chemical analyses. However, unlike other materials such as ceramics and metal, which can benefit from radio-carbon testing to help determine dating, glass analyses can only create ‘families’ or ‘signatures’ based on the primary ingredients present within the mixture. Furthermore, interpreting the glass compositions requires supplementation from historical and archaeological investigations. Nonetheless, a variety of scientific methods exist to better inform

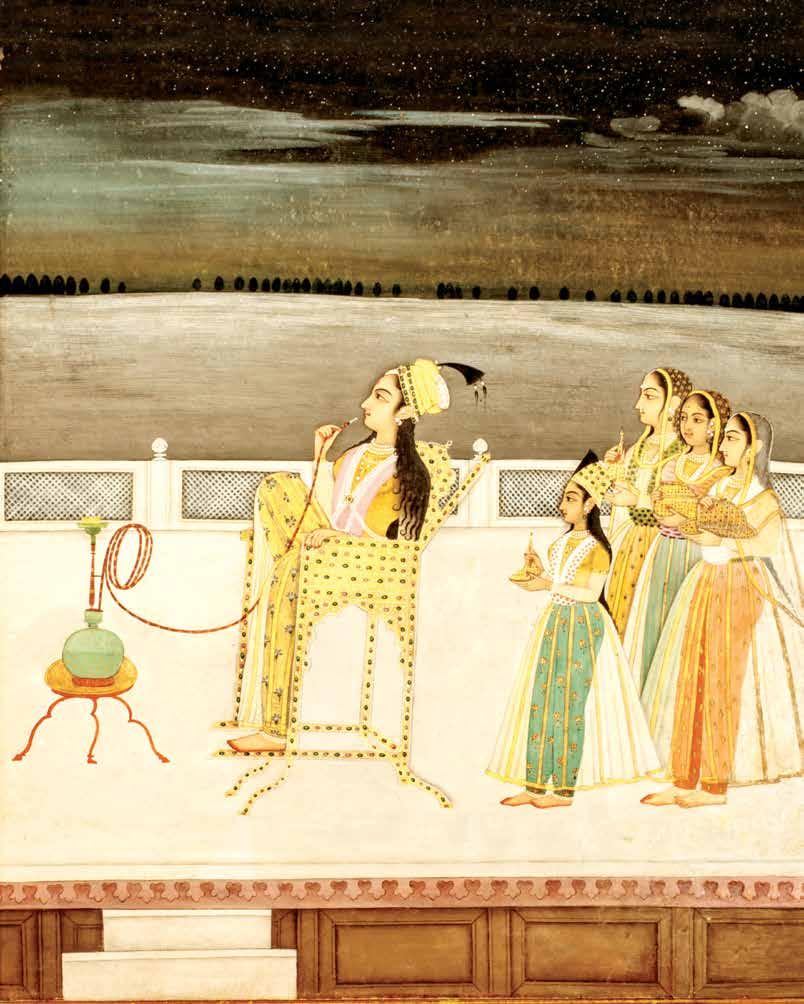

FIG. 5: TWO WOMEN SEATED ON A TERRACE, S u RRO u NDED

All glassmaking is divided into two or three stages of production: the engineering stage; the shaping of the glass into objects; and the decoration. The first stage involves making the matrix from raw materials, known as primary glass. Here, the glassmakers mix the ‘primary’ ingredients (typically, a variation of sodalime-silica) together in a hot furnace of at least 1,150 degrees Celsius (about 2,100 Fahrenheit) until they are transformed into a molten mass that can be worked. The vitreosity – that is the stiffness or hardness – of the molten mass will dictate how the glass can be worked and which type of object can be formed.

This primary glass working stage requires a substantial quantity of fuel – even for a small furnace – and is often the most expensive part of the glassmaking process. Since antiquity, two fundamental glassmaking traditions have existed, both yielding a distinct chemical type of glass known as the soda-lime-silica variety. This particular glass composition was employed by glassworkers across various ancient civilizations including Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Hellenistic, and Roman as well as later Islamic artisans. But even these mixtures varied based on access and treatment of raw ingredients: one used a natron-based soda, and the other a plantbased one. Natron glasses made along the Levantine coast were typically sourced from the natron beds of the Wadi Natrun in Egypt, whereas factories situated further inland used their own regional plant ash obtained by burning certain varieties of littoral or desert plants.1

The two types of soda (natron and plant) represent alkalis that traditionally function as

network modifiers and fluxers, and are used to lower the melting temperature of the glass mixture. By analyzing the respective levels of potassium oxide, magnesium oxide, and (sometimes) aluminum oxide in the mixture, chemists can distinguish between the two different types of soda. Magnesium oxide is particularly useful in distinguishing between glass made with a mineral source of alkali (natron) versus that made with plant ash, as glass made using natron generally has levels of about 1.5 weight percent or less; whereas glass made using plant ash as the alkali source typically has levels above 2.5 weight percent. Although glass mixtures typically contain three main components (soda, lime, silica), in many cases these primary ingredients actually come from only two batch ingredients. In the case of the natron-based glass, the necessary lime ingredient was probably introduced as an impurity in the beach sand, which served as the primary source of silica. Conversely, in the plant-ash based glass, the lime most likely came from the soda itself, which was introduced from the quartzite pebbles (considered as a relatively pure form of silica).

These ‘two-part’ compositions appear more commonly in ancient glass. Early glassworkers generally lacked awareness of the primary, secondary, or trace elements studied by today’s scientists; nor were they necessarily aware of the purity of their initial ingredients or colorants (if used). Rather, most glassworkers preferentially used materials close to their primary manufacturing site. This practice has consequently resulted in a uniformity of compositions that have been able to connect certain ingredients with particular regions. Analyzing the type and purity of ingredients has proven exceedingly helpful in identifying broad characteristics present within a glass mixture, which in turn, have helped

In the late sixteenth century, a new empire encompassing much of North India and Pakistan emerged. This super-state, now known as the Mughal Empire, surpassed much of Europe in both wealth and power. The Mughals were a Muslim dynasty from Central Asia who proudly traced their lineage back to Timur and Genghis Khan. They invaded the land of Hindustan in the early sixteenth century and established an empire that, at its greatest extent, stretched from Kashmir in the north to Mysore in the south. Under their third emperor Akbar, the empire expanded to the western coast of Gujarat and eastwards to Bengal and included twelve royal subahs (provinces) spanning across much of North India.

Several types and centers of glass production were known to have existed during Akbar’s reign. One site was the town of Chandwar Nagar, later renamed ‘Firozabad’ after it was given to Akbar’s general, Firoz Shah, as a reward.1 While Firozabad is recognized today for crafting glass bangles and ‘block’ glass distributed to furnaces nationwide, during Akbar’s reign, this area – situated a mere 40 kilometers north of the imperial capital, Agra – manufactured a range of vessels intended for the court and local markets.

It was most probably glass from Firozabad that filled the rooms of Akbar’s royal treasury, which, according to European travelers’ accounts held ‘more than two million and a half rupees worth of the most elegant vessels of every kind in porcelain and colored glass.’2 But the imperial capital also produced other kinds of glass. The Ardhakathanaka – an autobiographical

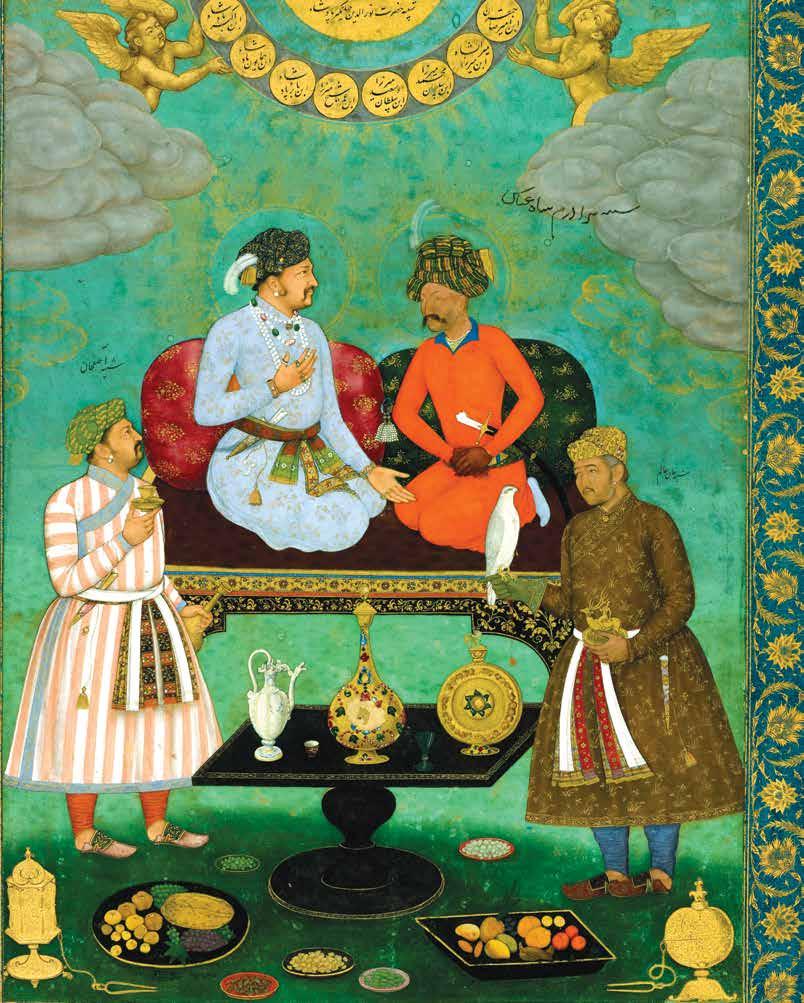

FIG. 11: jAHANGIR ENTERTAINS SHAH ABBAS by Bishandas Mughal, ca. 1620 Opaque watercolor and gold on paper | From the St. Petersburg Album, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (F1942.16a.)

text of the Mughal poet Banarasidas (1586–1643), written during the reigns of Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan (completed in 1641) – lists glassblowers amongst its list of service occupations in Agra.3 Not only did Agra serve as the most important commercial center, the road connecting it to Fatehpur Sikri (Akbar’s capital from 1571–85) was also described as one continuous market where everything could be procured in the royal bazaars accompanying the camp, including glassware.4

The Āīn-e Akbarī

The most substantive reference to glass recorded during the early Mughal period appears in the Āīn-e Akbarī, the third part of the Akbarnama (The Chronicle or History of Akbar), the official chronicle of the emperor’s reign. Compiled in 1589 by his court historian, Abu al-Fadl ‘Allami, the Āīn-e Akbarī is dedicated to Akbar’s administration and rule. Divided into five sections, the compendium offers detailed descriptions of the different administrative segments as well as occupations, including: the imperial household and royal ateliers; the division of the empire’s military and civil services; the imperial administration, including judiciary and executive departments, and land surveys; interpretations of social and religious customs, philosophy, and literature; and sayings of the Emperor, including his ancestry. Explicit references to glass appear in two of the five sections, the first and the third. In the former, the section is organized into ninety ‘Ains (‘Regulations’), each of which deals with a different segment of administration or occupation and includes laborers’ wages and building materials, for example. Of these, mention of glass only appears towards the end of the section: in ‘Ain 86, ‘The Prices

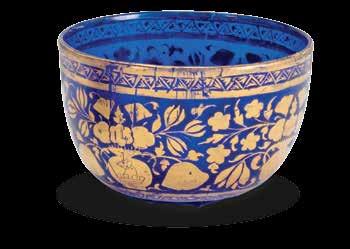

cat. 133 | SAUCER

Awadh or Bengal | 1725–1750 |

D: 14 cm | Free blown; tooled on the pontil; gilded | LOCATION: Victoria and Albert Museum, London (Ca.142–1936) | PROVENANCE: Given by Mrs. Buckley in memory of her husband, Wilfred, in 1936 | PUBLISHED: Pope and Ackerman 1938-39, vol. 6, pl. 1449; Skelton et al. 1982, 127, cat. 399; Swarup 1996, fig. 80

cat. 134 | CUPS

Awadh or Bengal | 1725–1750 | H: 4.3 cm; D (mouth): 7.3 cm; D (foot ring): 4 cm | Free blown; tooled on the pontil; gilded | LOCATION: Victoria and Albert Museum, London (Ca.140–1936; Ca.141–1936) | PROVENANCE: Given by Mrs. Buckley in memory of her husband, Wilfred, in 1936 | PUBLISHED: Pope and Ackerman 1938–39, vol. 6, pl. 1449; Skelton et al. 1982, 126, cat. 398; Swarup 1996, fig. 80; Liefkes 1997, 105; Desjardins 2021, 260, fig. 10

cat. 135 | EWER AND CUP

Awadh or Bengal | 1725–1750 | Ewer H: 15.24 cm; L: 18.73 cm; W: 12.06 cm; Cup: H: 5.08 cm | Free blown; tooled on the pontil; handle, footed pedestal and rim added; gilded | LOCATION: LACMA (M.84.124.2a-c) | PROVENANCE: Collection of Doris and Ed Wiener | PUBLISHED: Markel 1991, 87, fig. 8; Desjardins 2021, 260,

figs. 8 and 18

232 Mughal g lass

figs. 8 and 18

232 Mughal g lass

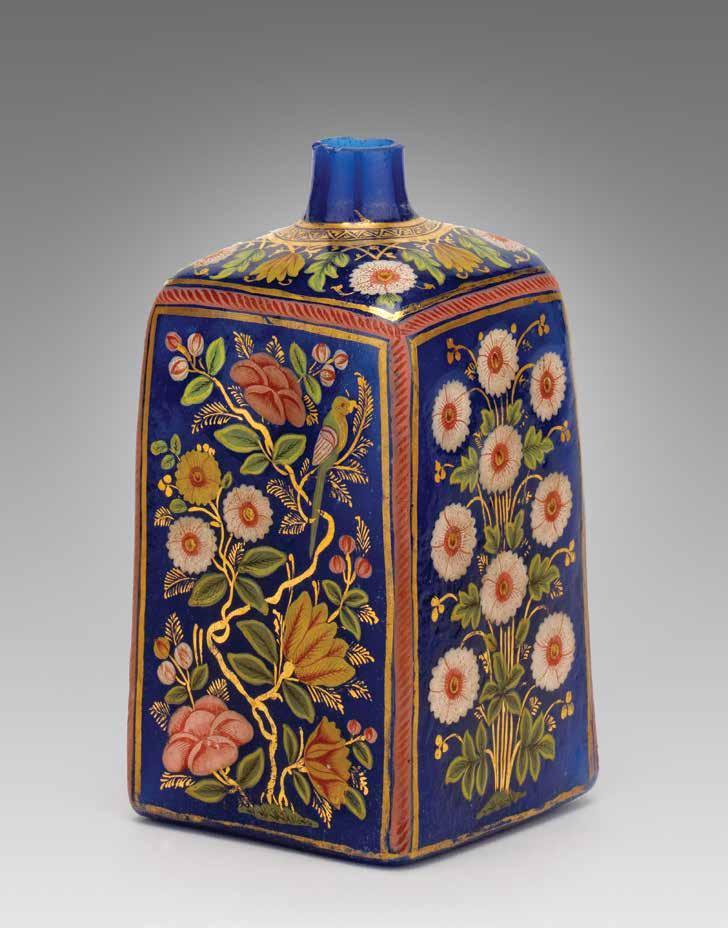

cat 7 | BOTTLE

Lucknow | 1725–1750 | H: 13 cm; W of base: 7.8 cm; W of opening: 1.4 cm; Wt: 314.8 g | Mold blown; tooled on the pontil; painted; gilded | LOCATION: British Museum, London (SLMisca.341) | PROVENANCE: Bequeathed by Sir Hans Sloane to the BM in 1753 | PUBLISHED: Tait 2012, 139, no. 76; Desjardins 2017, 652, fig. 2

Lucknow, where similar flowers are found on metalwork and works on paper (see Fig. 22).3

While neither bottle has been chemically analyzed, they were most likely formed from imported English glass. The 1765 Albion wreckage did reveal transparent blue-colored glass ingots amongst the ship’s cargo, which could have had locally sourced cobalt ore added to the mixture when remelted.4 According to late nineteenth-century records of the India Geological Department, cobalt ore naturally occurred in India but was only sourced from the ancient Babai copper mines at Khetri, in the province of Rajasthan between Delhi and Jaipur.5 Referred to as shta, it was extracted by crushing and panning black slate from these copper mines. Cobalt was predominantly used as a colorant for blue enamel by jewelers, metalworkers and, to a lesser extent, tile makers.6 Cobalt blue enamel features prominently in metalwork made in eighteenth-century Lucknow, serving as one of the distinctive traits that, today, helps assign metalware to the city. By the early twentieth century, however, the extraction of shta reportedly ceased being replaced instead by a better quality of imported cobalt.7

4. According to Redknap and Freestone, the ingots appeared almost opaque; however, even the stronger blues were quite pale and would have appeared transparent if the glass was used in thin-walled vessels; see Redknap and Freestone (1995), 146.

5. Sir George Watt, ed., A Dictionary of the Economic Products of India Vol. 1-3, Calcutta: Department of Revenue and Agriculture, 1880, vol. 2, 396.

6. Thomas Hendley, ‘Art Industries in Jeypore and Rajputam,’ The Journal of Indian Art vol. II, nos. 1-16 (London: Hanover Street Press, 1886), section 10, 4.

7. Maninder Gill, Thilo Rehren, and Ian Freestone, ‘Tradition and Indigeneity in Mughal architectural glazed tiles,’ Journal of Archaeological Science 49 (2014), 553; and Edward Dixon, ‘The Industrial outlook: Indian glass industry (part 1),’ Current Science no. 3 (1937), 184.

CAT. 5: Top view of the bottle including the Dutch coin.

76 Mughal g lass

CAT. 5: Top view of the bottle including the Dutch coin.

76 Mughal g lass

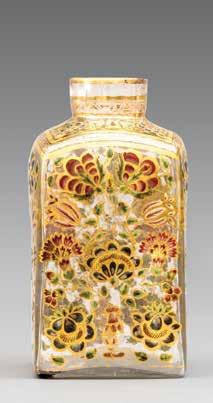

14 | BOTTLES

Gujarat or Rajasthan | 1725–1775 | A: H: 13.6 cm; L: 6.5 cm; W: 6.3 cm; Wt: 265.0 g; B: H: 10.5 cm; L: 5.7 cm; W: 5.5 cm; Wt: 198.2 g; C: H: 13.7 cm; L: 6.3 cm; W: 5.9 cm; Wt: 296.7 g; D: H: 10.6 cm; L: 6.3 cm; W: 6.3 cm; Wt: 200.8 g | Mold blown; tooled on the pontil; painted; gilded | LOCATION: LACMA (M.88.129.198; 199; 200; 202) | PROVENANCE: Gift of Varya and Hans Cohn | PUBLISHED: Saldern 1980, 189, cat. 195; Markel 1991, 89, figs. 11–12; 14–15

cat. 17 | BOTTLES WITH FUNNEL AND WOODEN CASE BOX

Lucknow | 1750–1800 | H: 15.1 cm | Mold blown; tooled on the pontil; gilded | LOCATION: Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum (201300749) | PUBLISHED: Um 2018, 200, figs. 1 and 2

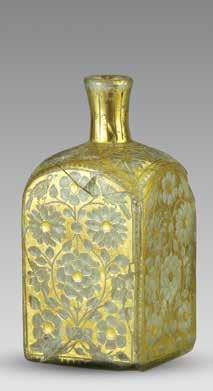

cat. 18 | BOTTLE

Lucknow | 1750–1800 | H: 15.7 cm; W: 8.1 cm Mold blown; tooled on the pontil; gilded; brass fixtures added | LOCATION: Stiftung Museum Kunstpalast Glasmuseum Hentrich, Düsseldorf (P.1985–98)

cat. 19 (Left) | BOTTLE

Lucknow | 1750–1800 | H: 14 cm; L: 7.2 cm | Mold blown; tooled on the pontil; painted; gilded | LOCATION: Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia (2013-7-29) | PROVENANCE: Christie’s South Kensington, 22 April 2013 (lot 271); Collection of Saeed Motamed, Frankfurt

cat 20 (Right) | BOTTLE

Gujarat or Rajasthan | 1725–1775 | H: 15 cm; W: 7.8 cm | Mold blown; tooled on the pontil; painted; gilded | LOCATION: Corning Museum of Glass, New York (82.6.10) | PROVENANCE: Acquired from Harcos in Nancy, France, July 1982

cat. 21 (Left) | BOTTLE

Lucknow | 1725–1775 | H: 14.6 cm; W: 7 cm | Mold blown; tooled on the pontil; gilded LOCATION: Corning Museum of Glass, New York (62.1.6) | PROVENANCE: Carlebach Gallery, New York

cat. 22 (Right) | BOTTLE

Lucknow | 1725–1775 | H: 14.5 cm (approx.); W: 7 cm (approx.) | Mold blown; tooled on the pontil; gilded | LOCATION: Benaki Museum, Athens (3339) | PUBLISHED: Clairmont 1977, pl. 32, no. 520