wider iMplications, the ecology of healthy wetlands

The rehabilitation of this historic lake and the creation of an enchanting usable waterbody has been a technically outstanding achievement. The lake now has water supply through the year to a minimum water depth of 2 metres at any point which may be used for boating and recreational purposes. Irrigation demand has been delinked from the lake’s water reservoir and tourism activities have started around the lake. Nature has begun to heal itself with the creation of wetlands and appropriate vegetation; birds of varied hues are flocking in. Life has begun anew for the lake. Many species of birds, including migratory birds that were not visible here for many years, have started revisiting. In view of ongoing research and debate on the effects of climate change and global warming, the restoration of the lake has been a significant step in the right direction.

With the lake coming back to life, the easiest way to gauge its ecological health was to look at the locally thriving flora and fauna. Both were monitored to access sustainability of

the wetlands. Wetlands are a valuable natural resource for wildlife and human being. A vast variety of wildlife finds food and shelter in the rich vegetation and the shrubbery acts as a sponge, soaking up water and reducing flooding. It also helps break down of pollutants. In the Man Sagar Lake, an outflow weir regulates the uniform outflow from the wetlands into the lake. The quantity and attributes of the vegetation were studied to insure a limited water table fluctuation. The lowest level of the wetland would provide a minimum water depth of metre and 98.50 metres at the islands, sufficient for macrophytes to grow on the banks and islands and survive even if they were submerged during monsoons.

Wetlands are liminal spaces – spaces in between, where differing forces encounter one another. At Man Sagar, different habitats – terrestrial and aquatic – come together. Quite invisibly, they maintain several natural cycles, regulate water quantity and facilitate ground water recharge while enabling a rich biodiversity. As it purifies water, they replenish this most precious of commodities and behave like a shock absorber against flooding and drought. In today’s parlance, they are also a major means to store carbon and improve water security.

selection of aquatic species

Plants were selected and planted according to their ability to sustain the fluctuation of the water table. Aquatic species were selected for reintroduction to act as bio-cleaners of water, for multiple indigenous bird’s species to feed on round the year and be useful for habitat consolidation. Reeds and rushes were selected for deeper parts, and in the lowest parts, only submerged macrophytes were planted. The plan was to enhance the sedimentation of the suspended solids in the adjacent wetland via natural stems and plant surfaces. Aquatic biocenosis has a high turnover in hot climates and support in substantially reducing suspended/ dissolved nutrients and pollutants.

To keep a robust ecosystem going, the unplanned growth of one species would affect the growth and survival of other species and alter the entire wetland ecosystem. Fundamental data about the wetland vegetation of Man Sagar Lake and the biology of significant grasses were studied. Paspalum, vetivaria savannah and such grasses important to native ungulates were

considered. These survive flooding and are used extensively by ducks and geese to home in.

With the restoration of water and plants, the natural progression was for the bird population, particularly the breeding species of birds and wintering waterfowl, to flock back. Approximately 170 species of birds have so far been recorded in and around Man Sagar Lake. Wetland habitats are ideal for migratory species. Studies reveal that most migratory birds arrive at the same wetland annually, seemingly like clockwork every year, bringing their young ones from the breeding grounds who in turn imbibe the migratory route. Once familiar with the wintering habitat, they return as adults to the same habitat year after year.

greater flamingos at Man Sagar Lake, Jal Mahal eastern side and nahargarh hills in the backdrop.

FaCing page: view of Man Sagar Lake in winter with migratory birds like gadwall, northern pintail, northern shoveler, tufted duck, common teal, common pochard, garganey, bar-headed goose etc.

researching the original conteXt

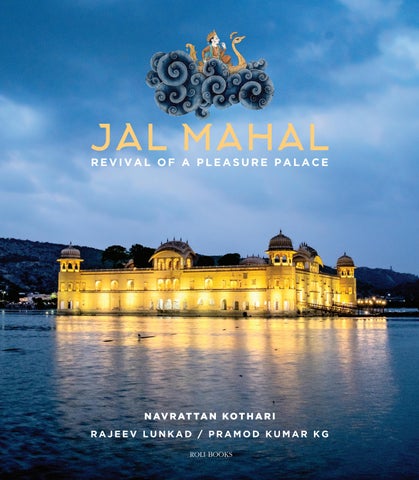

The restoration of the building and an understanding of its original context were to inspire much debate and discussion on other aspects of the complex. The idea of the ‘Pleasure Garden’ encapsulated as inbuilt expression within the Rajput architecture and cultural context became the seed of inspiration. The eventual expression and experience of the pleasure pavilion laid the larger context within which the revitalization vision evolved. The idea of creating a magnificent garden atop the Jal Mahal terrace became the focal point of the revitalization process.

How can we create the magical connect with nature and human senses that derive pleasure from the smell of rain, see the arriving of monsoons from the north-east, watch the sun rise and moon shimmer and reflect in the Man Sagar at night.

s ensory engagement with nature is the real embodiment of pleasure and with every opportunity humans get to connect with its beauty and magnificence, we reach a higher state.

We aspired for the gardens at Jal Mahal to create an experience that’s transformative, leading the visitors to a journey and opening up their senses to experience the heightened beauty through inspired creative expression.

A primary problem that was posed time and again was the quality of water in the lake. While there are many buildings that are bigger and architecturally more magnificent than the Jal Mahal in Jaipur, none are set out in the context like the Jal Mahal. Floating on the waters of Man Sagar and being reflected in it is what makes the Jal Mahal spectacularly unique. It’s the framing of Jal Mahal with the hills and the lake that defines the perfect picture. The lake is the soul of the monument’s creation and its derelict state is what made the entire area around the lake a depressing site for more than a century.

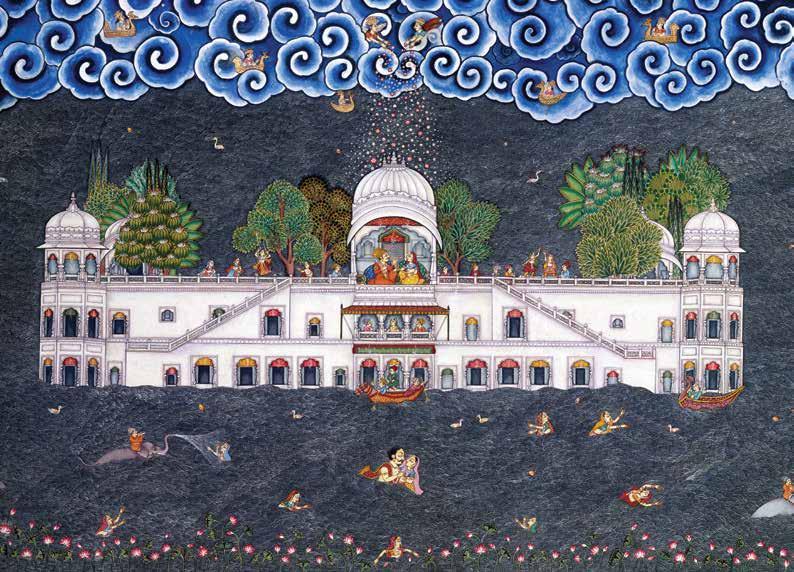

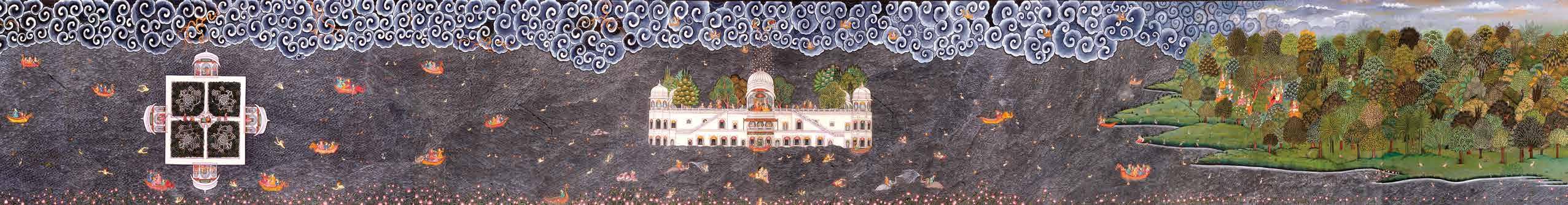

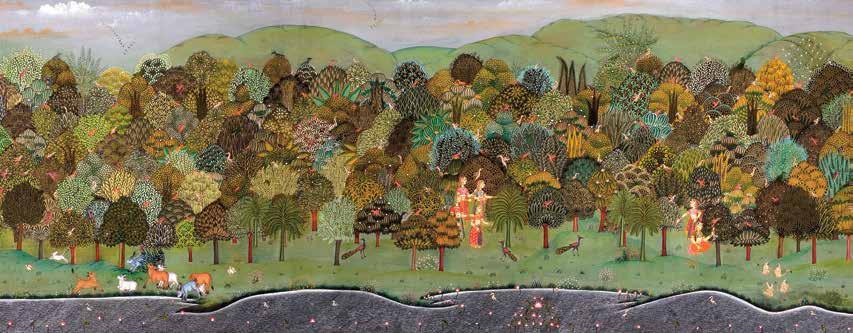

This 19th-century painting seems to mirror the promenade around Man Sagar Lake. The elaborate lakefront marina visualizes a series of palaces, pavilions and temples in great detail. The image is further animated with gods, temporal rulers and the laity alongside the distinct presence of Shiva and his sons ganesha and Kartikeya, sages and other celestial figures at the centre.

The rejuvenation of Man Sagar became the biggest achievement of the project to re-establishing the frame of reference for Jal Mahal. Reviving the blue waters and the sky reflecting in it made the Jal Mahal shimmer again, and that’s what we see today when we look at the glow of the monument.

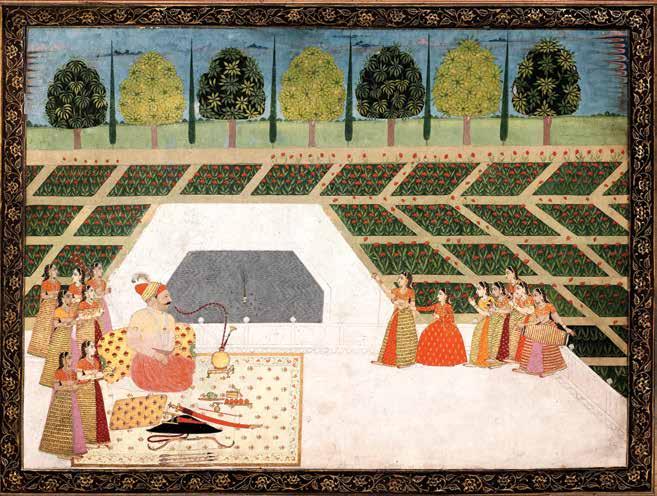

The next big challenge after the lake was the garden at Jal Mahal. The shape and form of its original gardens had been largely obliterated over time. An idea that resonated was to transform the terrace of Jal Mahal into a traditional ‘pavilion of pleasure’ through the creation of Chameli Bagh, a garden of great beauty and serenity, which would attract and delight the citizens of Jaipur as well as visitors from across India and around the world. To draw inspiration for the design of the Chameli Bagh, references were taken from the royal Rajput

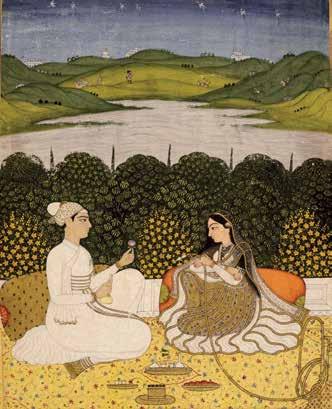

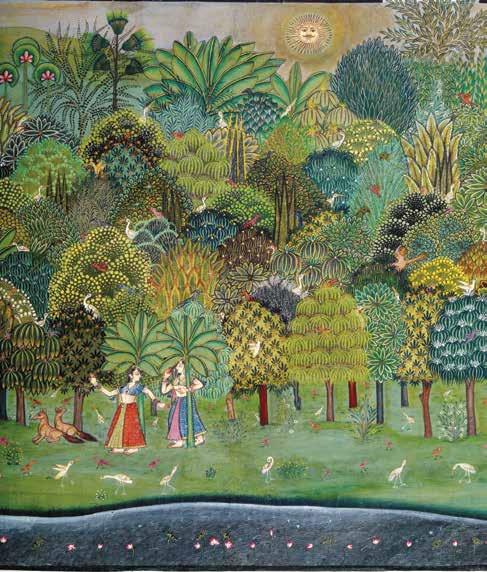

paintings from Jaipur in the 18th century frequently depict lovers seated in idyllic locations amidst views that may well have been the environs in and around the Jal Mahal complex. The background of flowing water amidst low-lying hills marks the site of the lover’s tryst, a vantage point to enjoy views.

gardens of Amber and Jaipur, simultaneously incorporating the latest advances in water technology and the art of gardening. The Chameli Bagh, the main focal point of the Jal Mahal terrace, has been planned as an oasis of calm and tranquillity offering visitors a welcome opportunity to sit quietly or be refreshed by a stroll through a lush garden experiencing an ever-changing play of light and water.

In the end, however, for the Jal Mahal to come alive as an experience, Man Sagar Lake needed to be cleaned up. No rejuvenation is possible without creating a befitting experience for those wishing to depart from the chaos of the city for a sojourn of peace and serenity. The rejuvenation of the lake and the multiple endemic issues was a very complex challenge. These ranged from problems of siltation, settled deposits, contamination from the inflow of wastewaters, decrease in water surface due to artificial land formation, decline in spread area due to downstream irrigation besides a host of other major and minor factors. From its historic use as a ‘source’ of water for the city, Man Sagar Lake had become a cesspool of garbage generated by Jaipur. Practicalities of running and maintaining efficient cost-effective systems were the need of the hour when a solution was sought from water and waste management issues at the lake. Eventually, for the rejuvenation of the Man Sagar Lake, a combination of natural treatment technology and advance tertiary treatments were envisaged for improving the quality of treated wastewater added to the lake .

Photographic images from the late nineteenth century and travellers’ description of the Jal Mahal, its adjoining lakebed and lands indicate that the site was largely abandoned by the midnineteenth century. The shift of the capital from Amber to Jaipur nearly a century earlier meant that Jaipur was now the focus of attention, and while the Kachhwaha past at Amber had been glorious, the future was clearly tied to the success of Jaipur. This could possibly explain the absolute lack of significant records of what use the Jal Mahal might have been put to historically. Hence, by the time the Jal Mahal rejuvenation project was embarked upon the site had to be cleansed of more than a century of apathy. Other sites of a similar nature in Rajasthan, namely at Udaipur, were also in decrepit condition in the nineteenth century; but the presence of larger more inhabitable rooms had meant that they were amenable to being repurposed as hotels and other tourist facilities in the twentieth century. Poignant images of the site in succeeding pages, though only allowing us a superficial glimpse, demonstrate the extent of the problem that the team faced as work began.

A distant view of the Jal Mahal on Man Sagar Lake, the Man Sagar Dam and the settlement of Jaisinghpura Khor beyond are framed from a vantage point up at the Charan Mandir. The temple complex is situated within the Nahargarh reserve forest and is a historic site believed to have existed from much before the establishment of Jaipur.

the function of Jal Mahal

t he complex in its fully restored glory today comes along with a larger plan and vision of revitalization both of its urban landscape and the wide expanse of natural habitat surrounding it.

Once a royal retreat, the complex is now in the public realm invoking a timeless quality that continues to draw people to it. Viewing the building from across the lake alludes to its past exclusivity, though today, we celebrate its universal access. Restoring the physicality of the Jal Mahal was an attempt to rejuvenate the monument to regain its earlier functions as a space for celebration, repose and contemplation.

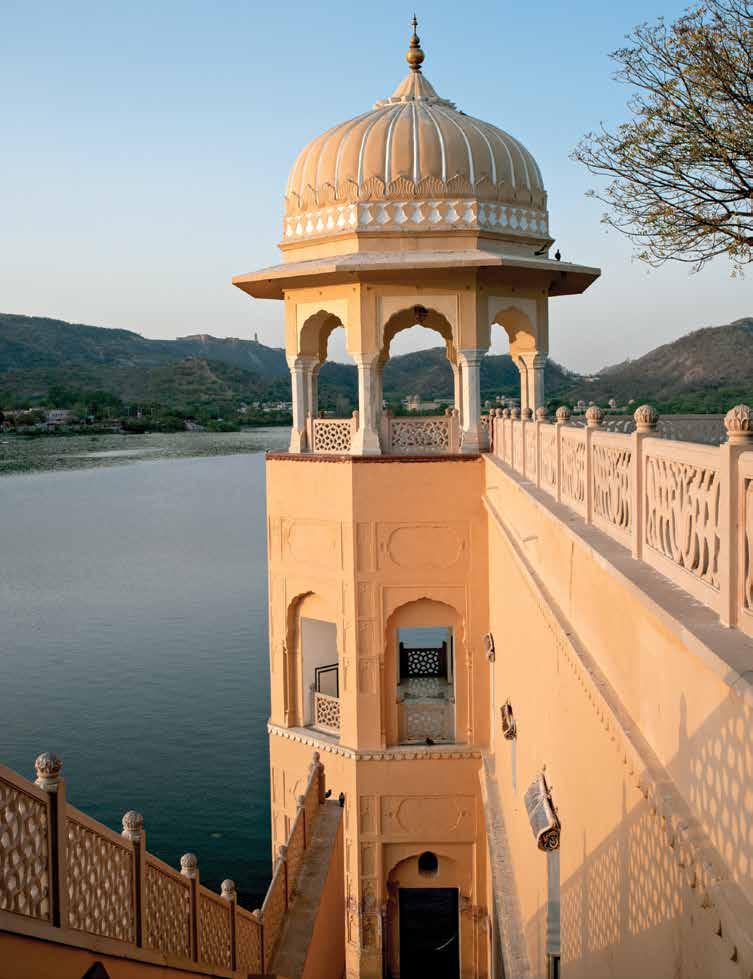

The Jal Mahal alludes structurally in its form to regional

specificities, besides pointing to a complex mix of influences that have long been assimilated in the local building idiom. The Islamic pointed arch is as prominent as the Rajput pavilions on the four-cornered turret-like structures. While the Bengal hut roof, a significant Jaipur adoption in the central pavilion, is visible on all four sides, nothing compromises the inherent diversity of influences that are beautifully articulated in the structure. The building to that end presents an outcome of resplendent harmony.

paintings from 18th-century Jaipur frequently portray rulers enjoying dance and musical soirees in various outdoor settings. a vast number of these showcase varied forms of garden design, perfectly delineated in great detail, frequently including water bodies. The idea of leisure in scenic settings, a well-established trope, offered much inspiration for the creation of new garden complexes.

The first floor of the Jal Mahal is one continuous foyer that circles the entire building, with alcoves that are screened with more jali windows overlooking the lake.

Despite its functional irrelevance, the framing spaces of light, air and sky continue to intrigue the visitor. This floor has been used intelligently as an art gallery, and the visual display is described in a later chapter titled Painted Pleasures.

An art gallery from our past does not mean rigid frames, borders or boundaries. In the original context of the Jal Mahal, wall murals that teem with the imagery of life, celebrated the many delights of the season, depicted in regional idioms that only the insider understood. Where art created by the human hand ended, god’s depiction of nature by way of the natural landscape began. Today’s choice of a word like an art gallery in many ways is thus inadequate to describe the older functions of many of Jal Mahal’s corridors. The art recreated on these walls, however, hope to allow our contemporary imagination to conjure the past.

flooring solution

The flooring at the Jal Mahal is of three kinds – lime, stone and soft ground. During restoration, it emerged that while the stone and lime flooring were part of the original architecture, there were some newer additions to the flooring too. While the stone flooring appeared in relative good condition, this was not the case with the flooring that was laid out in lime. At several places, the surface was worn out, broken or completely removed. The re-flooring of the complex, similar to its original pattern, was a major restorative process. With the adaptive reuse plans of the Jal Mahal, there are portions of the palace where there are likely to be more visitors. Stone flooring has been used in the areas where heavy footfall is expected, and in other areas, the traditional lime finish was restored.

Regional techniques of creating flooring patterns with stone elements were studied and adopted across the Jal Mahal complex in continuation with local building traditions. Several permutations and combinations for floor patterns were examined before a lexicon was adopted incorporating these designs.

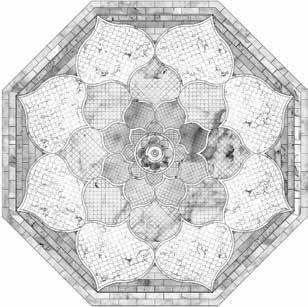

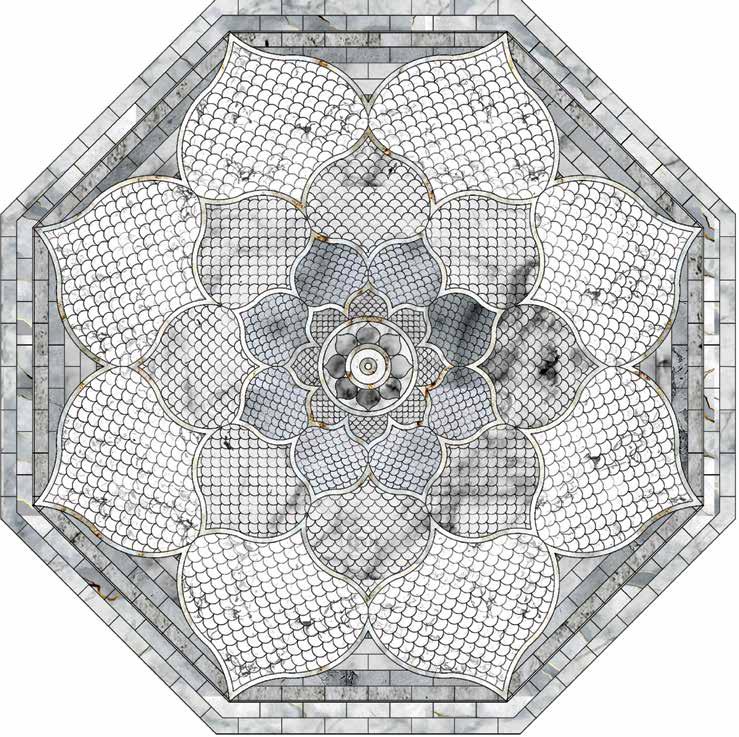

Several original artworks were commissioned for various aspects of the interiors. The octagonal platform at the centre of Chameli Bagh has the design of a lotus in full bloom. The concentric arrangement of petals is a

carefully considered detail which made use of local techniques of stone cutting in a fish-scale pattern to create individual wedges that form the plan. The design breakthrough helped minimize the wastage of material on site.

Monsoon unfolding

c louds pierce me with arrows, the peacocks dance in joy, the drunken frogs, make merry in the fields but the cries of the monsoon birds, burst open my heart.’

kA l dA s A m egh A dutA m, 5th century

Monsoon in Rajasthan is particularly welcome after the summer’s scorching heat. Rajput warriors traditionally went to battle in the dry season. The arrival of monsoon brings the warrior home. Lovers are reunited, wives perform aarti to welcome their husbands and weapons of war are put away.

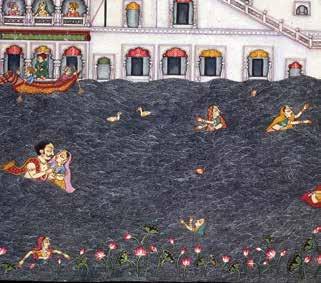

The mural begins at daybreak, as the sun rises in a red dawn, hinting at storms to come. The longed-for dark clouds, heavy with rain, swirl towards Jaipur. The sky quivers in anticipation as streaks of lightning announce the rains with an incandescent display, accompanied by a distant drum roll of thunder. With a great rush, the first drops throw themselves up on the parched earth, and everyone rushes out to greet the monsoon. As the rains envelop the land, the earth becomes lush and green. All nature awakens and delights in the life-giving rain. Elephants shower swimming maidens with bursts of water,

peacocks dance in stately splendour, and along the lakeshore, swans court among lotus buds. Festive boating parties embark from the shore, some heading for the Jal Mahal.

One can imagine court musicians playing a romantic Megh Malhar as the jasmine flowers of the Chameli Bagh release their seductive scent among the guests.

As night falls, the moon parts the curtain of monsoon clouds to fill the sky with silver gleams illuminating stray raindrops, while reunited lovers meet at last, eyes only for each other in this season of coming together.

every visitor to the complex encounters the Monsoon Rumal painting in the first wing of the Jal Mahal. here the Jal Mahal is rendered within a painted setting of thundering clouds with depiction of Chameli Bagh on the mural’s left.

Calmer skies and dense vegetation set the scene on the right of the mural. The details of the mural are all inspired by varying painted idioms from within Rajasthan’s painting traditions. while the upper register here depicts details from the complete mural, the full painting is visible across the lower register.

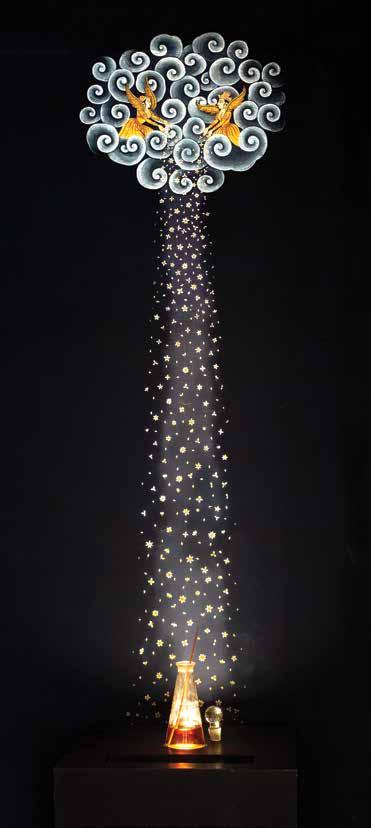

ittar Mahal, the scented chaMber

vetiver blinds, that lend to burning summer noons t he scented chill of winter nights.

For millennia, ittar (oil-based traditional perfumes) made from the aromatic oils of scented woods, flowers and grasses have graced the people of the Indian subcontinent, be it in the art of seduction, celebration or devotion. Perfumes were popular among all classes, but within aristocracy, they became highly sophisticated, precious and were much sought after with many a ruler being legendary patrons and connoisseurs of ittars.

Master perfumers were commissioned to create irresistible fragrances for both men and women. Popular ingredients included rose, sandalwood, jasmine, gardenia, frangipani, kadamba blossom, khus grass, heady musk oils and rarities like kewda from Orissa and saffron from Kashmir. No man or woman of any repute would feel dressed without a final touch of scent for the occasion, kept in a glittering array of cut crystal bottles called ittardans.

It was customary practice and a sign of great refinement to offer departing guests ittar. In keeping with this gracious tradition, the Scented Chamber at Jal Mahal invites you to experience and take home with you India’s iconic ittars, gill and khus.

Gill (also known as mitti or ‘sun-baked earth’) is redolent of the monsoon and that magic moment when the first drops of rain embrace the parched earth and the dry ground releases a fertile, earthy fragrance, full of the promise of harvests to come. Rich, mysterious and compelling, gill was a main ingredient for perfumes worn during the monsoon.

Khus, also known as vetiver, comes from grass reeds. Khus ittar, called ‘the oil of tranquillity’ for its soothing effect comes from these grass reeds that grow throughout India. The most prized for its unique fragrance is the Ruh Khus found across Rajasthan, which for centuries have also been woven into blinds.

When splashed with water and fanned, the khus blinds radiate a delightfully cool, mossy fragrance like a shaded grove by a clear stream of water.

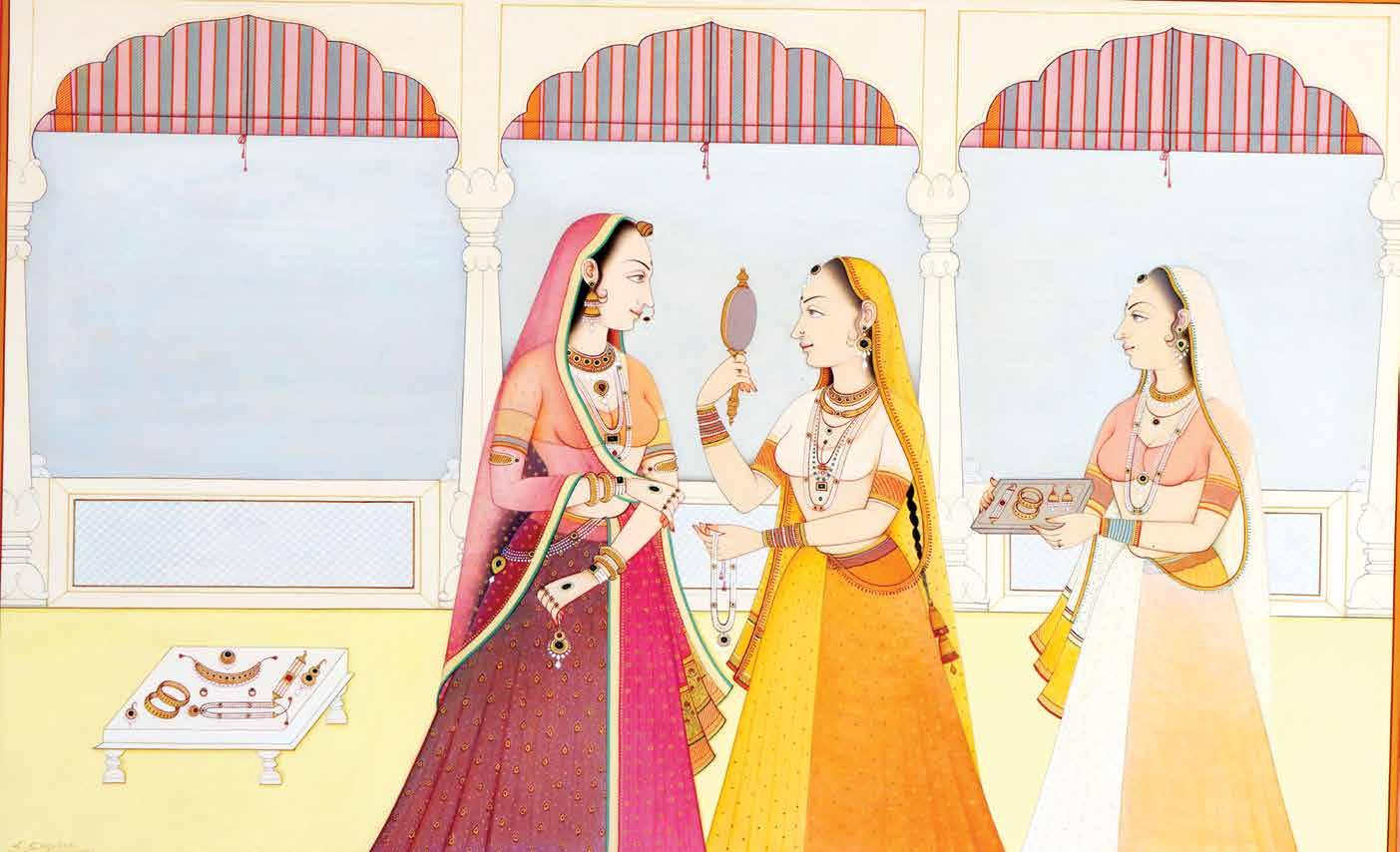

Shringar or the act of adornment is an important ritual often invoked in ndian music, dance, and painting. This contemporary take shows a lady getting ready with the help of her maids who help her choose jewels for the upcoming occasion. By the 19th century, traditional jewels of the region were frequently illustrated, and an array of traditional designs are seen in the image.

pRevioUS page 107: Shringara Rasa, the mood of adornment, was frequently invoked in paintings across the subcontinent. This contemporary rendition of pahari paintings depicts a royal lady at her toilette attended to by her maids. Looking into the mirror as an act of reflection was a philosophical move, but more literally, this is an invocation of the luxury of time and anticipated meetings with a beloved.