DELHI THEN

Text

narayani gupta

Photo Research & Editing

pramod kapoor

Lustre Press

Roli Books •

FACING PAGE: BAHADUR SHAH II, POPULARLY KNOWN BY HIS PEN-NAME ‘ZAFAR’, DID NOT KNOW THAT HE WAS TO BE THE LAST RULER OF THE MUGHAL DYNASTY. IN 1858, AFTER THE GREAT REVOLT, THE BRITISH SUBJECTED HIM TO A LONG TRIAL AND PRONOUNCED HIM GUILTY. HIS PUNISHMENT, LIKE THAT OF NAPOLEON, AND OF THE MARATHA AND THE AWADH RULER, WAS EXILE TO A DISTANT PLACE, IN HIS CASE RANGOON, WHERE HE DIED IN 1861.*

BY MANY NAMES

‘Delhi’is a name which has a quality ofbeing attractive because of its brevity. It was only one ofthe many names by which they knew this city. They called it Indraprastha, Firozabad, Dinpanah, New Delhi … Only now has it been reduced to ‘Delhi’. It is spelt in different ways. An early version was Dillika. In Urdu it is ‘Dehli’, in Hindi ‘Dilli’. Its present spelling – which only Malayalis pronounce with careful precision – came into use in English from the end ofthe 19th century. Names at times have a special meaning, but sometimes they do not. No one is very sure where the name ‘Delhi’comes from. A candidate for the identity ofthe person after whom Delhi may have been named is Raja Dhilu, described by Ferishta, a 17th-century Persian chronicler. But was it named for a person at all? Many towns are not. Its other names are more intelligible – we can understand ‘Indraprastha’in Sanskrit as a levelled settlement named for the god ofthe monsoon which could swell a river into a raging torrent. ‘Qila Rai Pithaura’was named for a ruler, the Prithviraj immortalized in folk songs. In ‘Firozabad’the name ofa king was attached as a prefix to a populated place, an abadi, called into existence by the presence of aab, water. ‘Din-panah’ suggests refuge or sanctuary, a place ofsecurity for the loyal. Here, then, in this triangle enclosed by a curving line ofhills and bordered by a river, were prastha, levelled areas, panah, havens secure under a strong king or a benign saint, abads, well-watered and populous settlements. The many urban settlements in Delhi from the 12th century did not grow effortlessly out ofthe landscape. They were levelled sites to which people gravitated by choice, to live in the security ofa city wall and a royal army. It has been a continuouslyinhabited settlement for over a millennium. There are sections ofits history which are obscure, others well-lit. The landscape ofmodern

Delhi is a mosaic ofbits from the past. A 13th-century canal mirroring a 16th-century monument enclaved in a 19th-century village, both dwarfed by a modern high-rise building and skirted by a traffic flyover is a typical cross-section, which few bother to disaggregate. But to those who have curiosity and the leisure to take in the city in bite-sized pieces, there are satisfying rewards.

PRASTHA

The geography ofthe Delhi area is not kind. The river Yamuna used to deposit saline swathes along its banks. Over time it steadily moved eastward, leaving the saline soil behind. The soil is variable, fertile in pockets, stony for most part. The climate is harsh, a crackling dry summer followed by torrential rain, then by a bitterly cold winter. These uncompromising seasons are divided by all-tooshort weeks when the weather is magical – clear and crisp, with soft breezes often flowing directly down from the distant mountains in the north. Which makes one feel how much more evocative is aab-o-hawa – water and winds, the Urdu word for ‘climate’(itselfderived from the Persian aqalim)

The Aravalli range, hills far older than the Himalaya, tapers offin Delhi to sink into the river Yamuna. In Delhi this line ofhills is called the Pahari (hillock) – in English known by the less poetic term ‘The Ridge’. There are places in Delhi which have the prefix ‘ pahar’or ‘pahari’ in their names, though today it is hard to discern the variations of height which made these part ofan undulating landscape earlier –Paharganj is level land, and Muradabad Pahari, Pahari Dhiraj, Anand Parbat, and Bhojla Pahari do not seem to have enough ofa gradient to justify their names.

*The paintings reproduced from pages 12 to 25 were executed on paper or ivory by Indian miniaturists in the early 19th century, for a largely British market. Note the emphasis on perspective and on the picturesque.

DINPANAH (PURANA QILA, 1530S-50S) NORTH VIEW OF HUMAYUN AND SHER SHAH’S FORT, ON THE SITE OF OLDER SETTLEMENTS POPULARLY THOUGHT TO DATE BACK TO INDRAPRASTHA OF THE MAHABHARATA.

Even today, when the ground has been built over and roads have been laid out, layers ofdull pink sedimentary rock glimpsed through levelled surfaces and at the side oftarred roads remind us how old the land-surface is. When, in the 8th century, the Tomars, a Rajput clan from the west moved northwards, they recognized the landscape as not very different from what they were familiar with. Their tradition was to build forts on hills rather than to level the ground. As was their custom, they dug deep wells, and laid out large shallow tanks to collect rainwater. But they realized that the area was less arid than

their homeland, and was blessed with the Yamuna, a generous provider. The river flowed with abundance in the monsoon months when the snows ofYamnotri melted. Over the millennia, the river had, after leaving Delhi, turned, flowing not west into Rajasthan towards the Indus, but east to join the Ganga to create the prosperous interfleuve which later inhabitants called the Do-aab. Their hilltop fort was Lal Kot, built by Anangpala II in the 11th century, on the southern Ridge, in Mehrauli.

The Tomar settlement was annexed in the 12th century by another Rajput prince, the Chauhan Vigraharaja IV, who was succeeded by his

nephew Prithviraj III. The Chauhan Rajputs, for whom Delhi was a frontier post, did not lay out a city by the river, as the peoples further east would have done. Instead, Prithviraj built a large fort north of Lal Kot, named for him as Qila Rai Pithaura. From here, on a clear morning, through the unpolluted air, they could see the sparkle ofthe distant river, just as till only thirty years ago one could see its shimmering ribbon from the northern Ridge. Thus when legend rewrote history, the evocative image ofPrithviraj building the Qutb Minar as a ‘folly’for his daughter to ascend and gaze at the Yamuna, took a powerful hold on people’s imaginations.

Millennia earlier, when people used to move in little groups across the landscape, and did not ask much ofit, they had settled in the small valleys carved out by the streams that ran down the Ridge to join the Yamuna. They left tell-tale traces which modern-day archaeologists were delighted to find, stone tools used for preparing meals, from the largesse provided by the ample forests and the animals that lived there. In the valley created by streams near the village of Anangpur in south Delhi, and also on the northern Ridge, the visiting-cards ofearly stone-age communities have been found.

Paleolithic man is ofgreat interest to the small family of anthropologistsand archaeologists, but what has caught the imagination ofgenerations ofpeople in Delhi is the account in the Mahabharata ofthe founding ofIndraprastha, the city ofthe Pandavas, for which no definite date can be given, but can be roughly placed at about 1000 BC. It is described dramatically as having been built after the dense Khandava forest that skirted the right bank ofthe Yamuna was burned down. There is a certain comfort in linking the city one lives in to a virtuous city ofthe past, even more so when, in the Mahabharata that city is imagined in terms ofmagnificent palaces. In actual fact the buildings were probably small, constructed from material so biodegradable that later rains and storms washed them away. Even so, and even with its name reduced to ‘Inderpat’, the sense

QUTB MINAR (1190S-1350S). EXCEPT THAT THE QUTB IS SHOWN WITH FIVE STOREYS, ALL THE ARCHITECTURAL DETAILS IN THIS PAINTING ARE SURPRISINGLY INACCURATE!

ofits presence was to be strong enough to fire the imagination ofthe very English artist-architect Edwin Lutyens, who spoke about his modern capital city ofNew Delhi being linked in the east to ‘the most ancient Delhi’.

The next levelling ofland for a city happened centuries later – in the 13th century, when the royal fort ofMehrauli was abandoned in favour ofa new one laid out in Siri, on the plains south ofthe site of Indraprastha. This was a time ofrapid sedenterization in Asia, a time when there was increasing movement oftraders, ofambitious young men in search ofofficial positions, and ofscholars, when the people ofthe hills ofAfghanistan and central Asia mingled with the people ofthe riverine plains, in the service ofthe Sultans ofDelhi. The cosmopolitan character ofthe royal army must have been evident when reviews oftroops took place outside the palaces, on the maidan, stretches offlattened land.

For these new towns, the Ridge was an outer fortification, and the river a highway, the road to the Doab. But the river was more than a highway. As the capital grew more populous, there was need for a regular supply ofwater, and serious attention had to be given to hydraulic support. Tanks were levelled and paved, and many step-wells were laid out – works ofart as well as utility. In addition, a huge labour force was recruited for one ofthe most extensive public works ofthe time, using quantities ofstone. This was a vast canal network to divert some ofthe water ofthe Yamuna from many miles upstream to irrigate the land around the citadels ofDelhi. This was levelled to make fields and gardens. Over the next five centuries, the landscape of Delhi changed, and the crowded urban area was surrounded not by undulating hills and streams, but by prosperous farms and orchards. Parcels ofland, with the right to collect revenue, were given by rulers as rewards to deserving officials or soldiers. The fields were cultivated by peasants, the Jats whose kinship networks were spread all across north India, while herds ofcattle owned by Gujjar families provided

milk to the town-dwellers. Orchards were a popular form of investment, since they were exempt from land-revenue. This levelling did not mean that all the land in the Delhi region had been tamed. The slopes ofthe Ridge were still thickly forested, impenetrable areas where mendicants and wild animals coexisted, where individuals who ran foul ofthe police could find refuge. The rulers and nobles ofthe court travelled great distances across the country both as part ofthe tasks ofadministration and during the exigencies ofbattles, but they were happy to have hunting-grounds near their capital city for

the occasional weekend of shikar. The northern Ridge, with its forest named Jahan-numa, and the woods ofPalam, were popular royal hunting-grounds. Today the number ofcheetal deer has shrunk, and the cheetah has vanished from Delhi, but one can still see the mendicants, the kaan-phata sadhus with their trademark black blankets, who have their camping-places and shrines on the Ridge. There were other places of worship which drew crowds during days offestival. These were either on the crests ofhills (as was Kalkaji Mandir on the east, and the Idgah on the western Ridge) or by the river (as were Wazirabad Masjid in the north, or Nil Chhatri Mandir further downstream).

This is one ofa series ofaerial views taken in the 1930s, which showed the twin cities ofMughal Shahjahanabad and British New Delhi (inaugurated in 1931). This one, ofthe southern end ofNew Delhi, has Safdarjang’s Tomb at the centre, the oval race-course on the left, and Safdarjang Road at a tangent. To the right is the Qutb Road (since renamed Aurobindo Marg), which linked Shahjahanabad to the hills and orchards near the Qutb Minar.

After the Great Revolt, the need to link the British-ruled territories by railway lines, desultorily discussed in 1853, acquired a sense ofurgency. This magnificent iron bridge, completed in 1867, was at two levels, the higher one for trains and the other for carts and pedestrians. It carried trains from Calcutta to Kalka, near the summer capital, Shimla, through Delhi. The track entered the city through Salimgarh Fort, occupied by the British Army.

Perhaps the most perfectly-proportioned ofthe Mughal mosques, the Jama Masjid was the centre-point ofShahjahanabad. Its spacious steps on three sides flow upward from the densely-built city, yet in a sense are also detached from it. Very popular public spaces, they were animated by story-tellers and performers, and commanded a wonderful view oflanes and neighbourhoods.

The Jama Masjid has always had a large congregation, except for five years following the Revolt when the government, as a punishment to the citizens, took the harsh measure ofclosing it for worship. A point of interest in this photograph is that it indicates that there was a separate enclosure for women during prayers.

Simultaneously with banishing Emperor Bahadur Shah II, his wife and son to Rangoon, the British recognized members ofa collateral branch ofthe royal family as the ‘Mughals’, which entitled them to claim allowances (called ‘pensions’) from the government. This photograph by Shepherd and Robertson ofMirza Ilahi Bux, a relative ofBahadur Shah Zafar’s wife, and his sons does not name them and just states that ‘The term Mughal applied to all the Mohammedans from the west and northwest ofIndia, except for the Pathans’.

Nautch (from the Hindustani word naach, or dance) was patronized not only by Indians but by the British in Indian towns, enjoyed by them as entertainment rather than to appreciate the music or the dance-form. Here the dancer, sarangi-player and the tabla-player are photographed in a rather anonymous setting ofa bare room.

This view ofChandni Chowk avenue, taken by Beato some years before that on page 46, shows clearly how much wider it was than it is today. The street faces the west, and is divided into two unequal corridors – the left is for pedestrians, the trees line the route ofthe central canal, and to the right is a wider passage for vehicles (here represented by Beato’s signature vehicle).

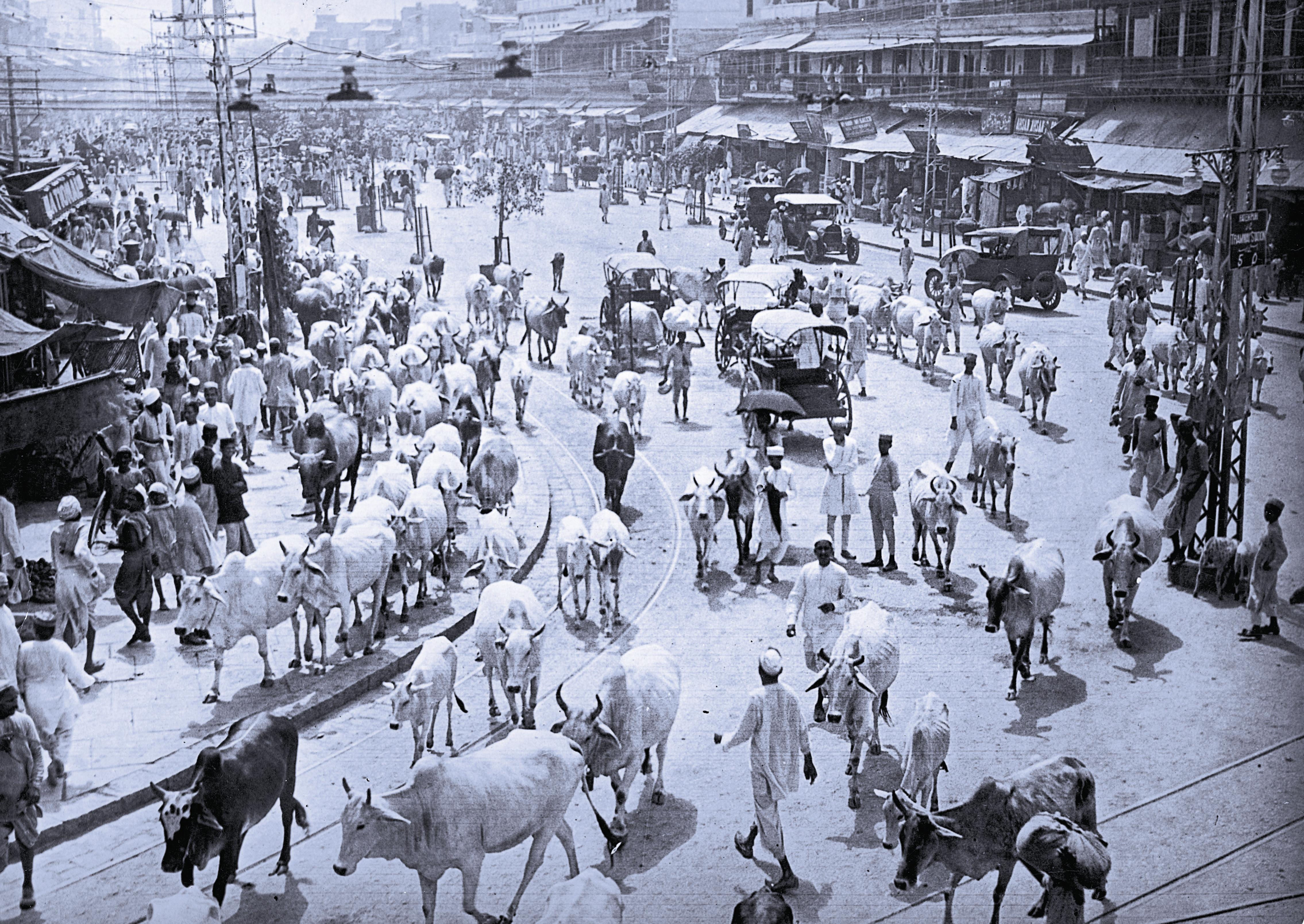

LEFT: Trams were introduced in Delhi from 1902. The tram from Chandni Chowk turns into Sadar Bazaar, the prosperous wholesale market that sprang up on the low hills to the west in response to the building of Delhi railway station in 1867.

to the

earlier, the

By contrast

view

street in the late afternoon is crowded with cows returning to the Sabzi Mandi suburbs after their milking sessions in the city, walking on the tram-tracks with the nonchalance common to all Indian cows at all times.

The ceremonial avenue designed at the centre of the imperial capital was turned to good use by the young republic, and the parade on 26 January 1951 shown here has become an annual celebration.

THEN DELHINOW THEN DELHINOW

A sight breathtaking, and emotions running high is what people experience witnessing the Republic Day celebrations. Parading the might ofthe country on this day are the armed forces, paramilitary forces and children making the morning of26 January on Rajpath a colourful and special day for everybody.

people from all faiths, this temple and its environs provide solace to the troubled mind.

temple is one ofDelhi’s modern architectural marvels. A haven ofpeace and tranquility in the midst ofthe city’s urban sprawl which attracts

FOLLOWING PAGES: The distinctive lotus shape ofthe Bahai

A home away from home: For innumerable daily-wage earners, labourers and workers, the city provides means to earn livelihood. Though life is tough, Delhi provides opportunities to earn, spend, and even meditate at times! As this labourer here who seems to be meditating inside a tunnel being made for the Metro.

First introduced in 2002, the Metro is rapidly covering the entire city and the National Capital Region as the system is a boon to commuters with its speed, efficiency and comfort.

The latest addition to Delhi’s public transport system and the pride of the city, is its spanking new Metro underground and elevated system.

intellectual role in the life ofthe citizens ofDelhi.

official organization in the capital, playing a unique cultural and

splendid is the aerial view ofIndia International Centre, a premier non-

Popularly called the ‘jewel in the crown ofGreen Delhi’, a visit to the Lodhi Gardens and its surrounding areas provide a visual treat. Equally

‘Best Urban Oasis in Asia’, and the adjoining Oberoi Hotel, which is the first five-star hotel in the capital, stands tall amidst the lush green trees ofthe New Delhi. These unique photographs were taken by a camera attached to a kite!

A kite’s eye view ofLodhi gardens, described by Time magazine as the

John Paul II who was instrumental in starting the process to grant sainthood to the late Mother Teresa. A rare photograph capturing two ofthe world’s leaders of peace and harmony, the picture brings into fore their love for humanity and the world.

Another famous visitor was the late Pope

Being the capital ofthe new emerging nation, Delhi attracts a steady stream of foreign dignataries and celebrities like world-renowned physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawkins, who used the occasion to visit some ofthe city’s famous monuments. Seen here is the physicist near Qutb Minar.

When India gained Independence on 15 August 1947, Delhi became the centre ofpower, as capital ofthe new nation. Every year the city gears up for major celebrations to commemorate the historic day. The prime minister addresses the countrymen and hoists the national flag at the Red Fort. Apart from rejoicing in our freedom, it is a day when Indians pay homage to their freedom fighters who sacrificed their lives for India’s Independence, and also celebrate the comimg together of more than 400 princely states into one unified force, India.

26 January 1950, when India became a sovereign state and the Constitution ofIndia came into effect. The parade, led by different regiments ofthe armed forces, marches down Rajpath and makes its way to the historic Red Fort, while India’s cultural diversity is highlighted by the floats representing various states. It is also a unique opportunity for schoolchildren from all over the country to perform on the national stage on such an important day when the entire country is watching the parade on TV or live in Delhi.

26 January each year. It marks the most important day in Indian history,

There is nothing quite like the majesty ofthe Republic Day parade which takes place in the capital on

Bhawan provides!

convertible being graced by a royal backdrop that the Rashtrapati

21st century showcases a young model sitting on an imported

rapidly changing city mindful ofits historic past. The New Delhi of

juxtaposition ofold culture and the new cool attitude mirrors a

growing affluence and youthful independence adding a new energy and a new layer to its traditional power circles, represented by the imperial Presidential Estate and its immediate surroundings. The

Delhi has undergone a dramatic transformation in recent years, with

spotlit, it is a breathtaking sight.

the Amar Jawan Jyoti, the eternal flame, symbolizing the tomb ofthe Unknown Soldier, a black marble cenotaph with a rifle placed on its barrel, crested by a soldier's helmet. On each ofits four corners are flames that are perpetually kept alive. At night, when India Gate is

historic arch ofIndia Gate, the 42-meter high war memorial built to commemorate Indian soldiers who died in World War 1 and the Afghan Wars with their names inscribed on the walls. Directly under the arch is

FACING PAGE: The grandeur ofRajpath is enhanced by the

reflected in the modern glass and steel temples ofenterprise and individual indulgence is a constant reminder ofthat historical and architectural marriage.Some large villages like Dera in Mehrauli or Rajokri in Najafgarh still retain some oftheir agricultural holdings and rustic village-type ambience, but the dominating feature ofthis former rural belt

culture have managed to coexist. Driving through this city ofcontrasts – the upscale enclaves cheek by jowl with sprawling slums, ancient royal monuments and forts

bars and restaurants that have mushroomed all over the city, catering to the new-found urge among young, affluent residents to party like there’s no tomorrow. Delhi was always a gourmet’s delight but mainly for its north Indian and frontier cuisine perfected in celebrated eating places like Karim’s in Old Delhi, Bukhara at the Maurya Sheraton, the ubiquitous Moti Mahals or the cluster ofclones on Pandara Road. Of late, however, contemporary changes in taste and lifestyles have sparked a boom in restaurants serving global cuisine, from Greek and Italian to French and Lebanese, Thai, Japanese and Korean. The trend of transplanting established stand-alone restaurants/lounge bars from other cities like Mumbai – Olive, Athena, Oliva and Imperial Garden are prominent examples – is indicative ofthe boom town status that Delhi has lately acquired. Yet, for all its contemporary chic and its modern adornments – the showpiece Metro being the latest – it is the combination ofthe old and the new that still has the most resonance, for visitors and residents alike.Delhi’s uniqueness lies in how that clash ofcultures, the grandeur and heritage ofthe past, and the brash new in-your-face

estate prices, the luxuriant, well-tended parks, to a rash ofchic pubs,

The rising affluence is reflected in a myriad ways, from the number ofluxury cars on the road to the expansive farmhouses, escalating real

expectancy stood at 47 years. It is now 65, much higher than the national average of56 years, mainly due to rising income levels and a better standard ofliving for most ofits residents.

cent, way over the national average ofaround 52 per cent. In 1951, life

The fallout has been positive in diverse ways but one statistic best illustrates the recent boom. The number ofpersons living below the poverty line has declined to around 8 per cent today from 15 per cent in 1994. Delhi excels in other areas on the development index. Despite the constant influx ofmigrants, the city’s literacy rate stands at 83 per

monuments attract a majority offoreign tourists coming to India, as does its location as a springboard for travel to the country’s northern states. In a way, Delhi is the most visible symbol ofthe country’s impressive economic growth.

In recent years, it has attracted new sectors like life sciences, telecom and Information Technology. A preferred destination due to the quantity and high calibre ofits English-speaking population, Delhi and its suburbs account for over 30 per cent ofIndia’s IT and IT-enabled services exports – the second-largest in the country (Bangalore accounts for 35 per cent). It is also the media capital ofthe country: headquarters ofall major newspapers, general and financial, are located in Delhi, as are major television companies. It is also the publishing capital ofthe country. In recent years, it has emerged as a world-class health care centre with some ofthe best hospitals and medical research institutes like the All India Institute ofMedical Sciences, Escorts Heart Institute and Research Centre and the Apollo, Max and Fortis chain of hospitals adding to its impressive facilities. Delhi also has the economic advantage ofbeing a major tourist hub. Delhi’s historic buildings and

grown at least twice as fast as in Mumbai.

HERE SHOWCASE THE PARTICIPANT DESIGNERS’ PRET AND COUTURE LINES IN INDO-WESTERN AND WESTERN CATEGORIES.

MOST EMINENT NAMES IN THE WORLD OF FASHION, ACCESSORIES AND TEXTILES PARTICIPATE. MODELS

LIKE WILLS LIFESTYLE FASHION WEEK WHERE INDIA’S

HOSTS SOME OF THE MOST POPULAR FASHION EVENTS

FACING PAGE & BELOW: A CITY OF WELL-KNOWN DESIGNERS AND FASHION EXTRAVAGANZAS, DELHI

industrial units every year since 1991. According to Amrop, a leading head-hunting agency, in the last few years, job creation in Delhi has

unceasing advent ofnew businesses has seen the growth of9,000

Sonys and Samsungs ofconsumer durables; Honda in the automobile sector (Maruti has always been headquartered here); the Motorolas and the Nokias oftelecom to the GE Caps and the ICRAs offinance. The

opened shop in India over the same period have chosen Delhi as their base. These span the entire spectrum ofbusiness activities, from the

Mumbai all his life. No other city in India has registered a faster rate of job creation in the last decade. More than halfthe MNCs that have

CEO ofProctor & Gamble, shifted to Delhi in 1994 after living in

states corporate guru Gurcharan Das. He should know. The former

Dream City ofIndia. A city that provides people with jobs and home,’

suburbs like Noida, Gurgaon and the industrial enclaves ofFaridabad and Ghaziabad, providing both jobs and affordable housing. The generous boundaries (30,242 sq km) ofwhat is now the National Capital Region (NCR) extends into Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan. ‘More by default than by design, Delhi is emerging as the

That has been fuelled, in large part, by the emergence ofaffluent

(about 20 per cent ofnational sales); and is the single-largest market for electronics and home appliances. Delhiites also own more washing machines (57 per cent oftotal population) than their counterparts in Mumbai (42 per cent). The number ofcredit cards registered in the capital has gone up by an astounding 62 per cent to 11 lakh (1.1 million) over the last decade, again the highest rate ofgrowth anywhere in the country. There are other equally significant pointers to Delhi’s flashy prosperity.The city has over 32 lakh mobile phone users, far in excess ofits total fixed telephone line connections. Without anyone quite noticing, Delhi has grown from a sleepy bureaucratic town into a dynamic, economic powerhouse.

According to the latest figures for 2004-05, Delhi boasts ofa per capita income at current prices ofRs 53,976, more than double the national average ofRs 23,241. Income, however, is only halfthe story. Delhiites believe in conspicuous consumption. A report ofthe Delhi government shows that the average monthly expenditure for the capital’s citizens jumped by 9 per cent in 2005 over the previous year. No

influx ofover 5 lakh Punjabis from Pakistan, was politically inspired, the second wave, starting in the early 90s, which increased population figures by some 43 per cent, has been largely inspired by economic opportunities. The statistics tell the story.

The ‘vigour ofits life’has resulted in a level ofaspiration and prosperity that is a classic symbol ofthe new India. Ifthe first wave ofimmigrants, the post-Partition

‘I have been repelled by Delhi’s congestion, its overgrown trade and its lack ofpride. Yet, I am charmed by the romance ofits past, by the vigour ofits life.’

seen as effete into one that is forceful, extrovert and on the move. Former Lt Governor ofDelhi Jagmohan summed up the city perfectly when he recently stated:

gracious living before Partition, now it has become congested and loud.’Yet, no other city has shown such a discernible level ofupward mobility. The Punjabi influence that Khushwant derides has actually turned a culture that was

wonder Delhi has more vehicles on its roads than Mumbai, Chennai and Calcutta put together; it is the biggest consumer ofsoft drinks

unabashed admirer and critic, admits that: ‘The likes ofmy family brought the loud dhaba culture ofthe nouveau riche here. Today, it’s the Punjabis who dominate this city. It was

‘Tiger’Pataudi observes:‘Delhiites are obsessed with where you live and how much money you have. He’s not being rude, it’s just the way he is.’Khushwant Singh, India’s best-known author and the city’s

Nagar, the flashy lifestyles ofthe new breed ofnouveau-riche entrepreneurs is on full display, from the in-your-face, pink stucco houses to the luxury cars in the driveways and the air-conditioners hanging out from every available aperture. Keeping up with the Junejas’ is an expensive obsession but its one that Delhi indulges in with obvious relish, ifnot good taste. Delhi is, above all, an aspirational city, bold, brassy, and brash. As former Indian cricket captain and Delhi resident,

Beverly Hills an inferiority complex. Elsewhere, in affluent south Delhi enclaves or even former refugee colonies like Punjabi Bagh and Malviya

That, sadly enough, is in evidence all across the city. Start with the extravagant farmhouses in the Mehrauli-Rajokri belt which display a bewildering range ofarchitectural indulgences, from Spanish villas, to American-style ranch houses and marbled mansions that would give

ofgrand old aristocratic dowagers’had become ‘a nouveau-riche heiress: all show and vulgarity and conspicuous consumption.’

‘Full ofriches and heroes.’Ofcourse, he was justifiably scathing about what the city has evolved into, showing, in his words, how ‘the grandest

show how New Delhi resonates with the old, and bring to life a city

lay in his creative ability to peel the historical onion, so to speak, and

resident, captured the city with rare insight in his City ofDjinns. His skill

vigour and dynamism that has become unique to the city. Mumbai may have purloined the title ofCity ofDreams, but here in the capital, is where they have come true. A combination ofnorth Indian aggressiveness and ambition and expanding levels ofeconomic opportunity has created a sizeable generation offirst-time entrepreneurs and impresarios who today provide the city with its visible veneer ofaffluence. Author William Dalrymple, a long-time

often mistake for arrogance and boorishness. At another, it reveals a

At one level, this is the city’s negative face, one that first-time visitors

Reading the local newspapers, it almost appears that halfthe city is on the make, the other halfon the take.

Everybody is in a tearing hurry to get somewhere, everyone seems to have relatives in high places and even the beggars at traffic crossings bang on your car windows with an arrogance that is almost threatening.

Yet, like people, cities acquire signatures, a universally recognized leitmotif: New York’s skyline, Paris and romance, Milan is synonymous with style and Venice has its waterways. The connection, whether abstract or physical, becomes as permanent a symbol ofthe city as monuments and memorials. Shorn ofits historical influences and privileged status as India’s capital, and political and constitutional crossbreeding that makes it one ofthe world’s few remaining citystates, contemporary Delhi flaunts one undeniable signature: an air of aggressive intent. From the frenetic traffic to its egoistic bureaucrats, pampered politicians and social prima donnas, the flashy, nouveau riche and the policemen on the roads: everyone displays a practiced assertiveness that says, louder than words: ‘Get out ofmy way.’

a single identity or cultural characteristic that defines Delhi, a single way ofgrasping its complexity.

contrast, New Delhi, or more precisely, Lutyens’Delhi, (named after its original architect and planner Edwin Lutyens and still referred to in official municipal records as Lutyens’Bungalow Zone or LBZ), portrays a combination ofunderstated refinement and political and bureaucratic privilege. The two worlds rarely meet but together they convey a true sense ofDelhi’s romantic appeal. It’s an appeal that has largely been submerged under the undisciplined urban jungle that has sprouted at such a frenzied pace over the last three decades and diluted all traces of Hindu, Islamic or British influences. Today, it would be difficult to find

somewhat bedraggled old-world charm: lively, colourful bazaars, celebrated eateries, narrow streets and barely controlled chaos. In

Visitors to the capital got two cities for the price ofone. There was ‘Old’Delhi, Mughal and Islamic heritage intact, dominated by imposing mosques, monuments and forts that even today resonate with the famous declaration by legendary poet Mirza Ghalib: ‘The world is the body and Delhi its soul.’Behind the history, the old city displays a

as late as the mid-70s, Delhi was easier to define, and negotiate.

illT

A UNIQUE LEGACY

could easily be defined as the Alchemy ofan Unloved City.

loyalty, pride and a sense ofbelonging, contemporary Delhi’s culture

Hindu Punjabi families from Pakistan. A recent survey revealed that 60 per cent ofthe capital’s residents are not Delhi born. In terms of

In fact, well over halfofthe capital’s population, close to 14 million, are migrants from other parts ofIndia attracted by employment opportunities or owing their origins to the post-Partition influx of

Even its politicians and bureaucrats, the fountainhead ofpower and patronage, are mostly from outside the city. Their loyalty lies elsewhere.

Chennai is, well …, Chennai, ultra-conservative, fiercely protective of its Dravidian roots and larger than life politicians but growing in corporate stature as India’s Detroit thanks to the automobile majors who have headquarters there. Delhi arouses no such loyalty or affection.

Information Technology capital and software supplier to the world.

loyalty among its residents. Bangalore basks in its undisputed reign as

edges, still revels in its intellectual and cultural elitism, inspiring intense

Mumbai conveys Bollywood glamour and high-stakes finance, secure in its status as India’s commercial capital. Kolkata, somewhat frayed at the

Other metropolitan cities in India have less ofan identity crisis.

stereotypes dictate much ofthe city’s character.

The imperial city created by the British, ofspacious, tree-lined avenues, graceful bungalows and imposing government buildings still exists, conveying a sense oftimeless elegance and serenity that is in stark contrast to other parts ofthe capital. Contemporary Delhi, frequently defined as a ‘city ofcities’, is, however, characterized by visible fragmentation, the heterogeneity ofits urban fabric becoming almost a modern-day caricature ofthe empires and dynasties that shaped its destiny and evolution. Indeed, Delhi has more layers ofculture, civilization and history extant in it than most cities in the world. While this may have left behind an architectural heritage that is a permanent reminder ofthe city’s historical past, the frenetic growth in urbanization and population between 1977 and 1999 ensured that

The result is that the reality ofIndia’s sprawling capital is more diverse, more anarchic and more contradictory than the near-mythical Delhi of Lonely Planet guides.

Delhi: chaotic traffic, an urban anthology ofindiscriminate growth, prevailing architectural styles that defy genre or genesis and a population influx that has put civic services under excessive pressure.

With a unique legacy spanning 3000 years ofrecorded history and seven dynasties (excluding more recent political dynasties) which have left behind spectacular monuments and forts, Delhi deserves its status as one ofIndia’s most iconic cities. Yet, at a subliminal level, it’s the ‘madcap façade’that is the dominant image ofcontemporary

the inner peace ofa city rich with culture, architecture and human diversity, deep with history and totally addictive to epicureans.’That is the eminently sensible advice that Lonely Planet offers first-time tourists.

AN ICONIC CITY on’t‘D let your first impressions ofDelhi stick like a sacred cow in a traffic jam: get behind the madcap facade and discover

Delhi has morphed into a multi-layered megapolis made up of innumerable, self-sustaining enclaves. That perhaps explains why