Conducted

by

Rokh Research & Design Studio

MARION COUNTY PUBLIC ART CENSUS

Conducted

by

Rokh Research & Design Studio

MARION COUNTY PUBLIC ART CENSUS

A project supported by the Indy Arts Council and the City of Indianapolis Bicentennial Commission

Produced in partnership with Art Strategies LLC, with funding provided by the Herbert Simon Family Foundation and the Central Indiana Community Foundation

Public art matters, and its definition must be broadened. Public art is an opportunity for residents and the city to have an exchange of values, and a reflection of a myriad of community values and experiences.

The Indy Arts Council, in conjunction with the City of Indianapolis Bicentennial Commission, partnered with Rokh Research & Design Studio to inventory the public art within Marion County, Indiana. Rokh analyzed the findings to generate an understanding of the relationship between public art and its spatial distribution across the County.

The research team conducted a street-bystreet census of existing public art, including memorials, monuments, and markers across Marion County, collecting information that identified, mapped, and profiled visible works including, and beyond, city-owned public art.

With the data points collected, the research team performed an analysis to identify spatial

patterns and evaluate the distribution of inequitable outcomes. A preliminary (not comprehensive) analysis was also conducted on the Indy Arts Council’s Public Art Directory.

While there is a bountiful selection of public art within the County, the questions of accessibility, equity, and inclusivity arise. This report seeks to explore the opportunities for Marion County’s public art sector to engage more comprehensively with community members, artists, and visitors to co-create a public art landscape for all. Public art has the ability to host a full range of human experiences and invigorate the quality of life for all, regardless of ethnicity, gender, age, or ability. With this as a guiding light, the need to reassess the inclusivity of our public spaces is paramount.

Marion County is the largest County in the State, it is home to Indianapolis, the State capital, County seat, and the largest city within its borders. It is delimited to the west by Raceway Boulevard, to the north by 96th Street, to the east by 800 West/Carrol Road and to the south by County Line Road. The cities within Marion County’s boundaries are Indianapolis, Speedway, Lawrence, Beech Grove, Southport, Clermont, Warren Park, Homecroft, Meridian Hills, Rocky Ripple, Wynnedale, North Crows Nest, Williams Creek, Crows Nest, and Spring Hill.

According to the 2020 United States Census, there are 964,582 residents in Marion County. The majority of the population identifies as White at the rate of 63.5%, Black or African Americans 29.1%, Latino/a/es 10.9%, and Asians 3.8%. We draw attention to this, because in order to have an equitable distribution of works, the public art within the county should reflect the population demographics.

When we stop seeing communities with art, we start seeing communities with problems. Public art is essential to fight against aesthetic apathy and coalesce community pride. It not only serves to beautify, but more importantly, it signals what’s important to neighbors.

Art in public places should be an opportunity for all to learn about themselves, celebrate the identities of others, and take stock of the history and heritage surrounding it. Public art and its creators are essential! Both directly influence one’s ability to have an enriching experience in the public sphere.

Inequities within public space are endemic, however, by isolating public art, this report investigates its relationship and potential to affecting spatial justice and economic equity.

Public art is ESSENTIAL!

Danicia

Planner, Compassionate Geographer & Interaction Designer, Rokh

H OW T O U S E T H I S R E

Our hope is that this report will be a tool of individual and collective action towards creating a public art landscape that welcomes and acknowledges all.

Learn key words and unfamiliar terms in the glossary page 19

Locate public artworks by zip code and by City-County Council district pages 22 & 23

This report is organized into three main sections:

Advocate for change with direct calls to action page 15

Review inventory conclusions & recommendations pages 67–74

Examining the number, type, condition, and authorship of artworks

Examining artwork location, density, and intersection with other place-based data

What can residents, advocates, and decision-makers do?

Public art is artwork in the public realm, regardless of whether is it situated on public or private property, or whether it is acquired through public or private funding.

Public art is sculpture, murals, manhole covers, paving patterns, lighting, street furniture, building facades, gates, fountains, playground equipment, engravings, carvings, frescos, mobiles, collages, mosaics, bas-reliefs, tapestries, photographs, drawings, architectural elements, graffiti, street art, tactical urbanism, pop up events, festivals, and more.

Public art includes contemporary-style art, civic art, art in public places, social practice art, community-engaged art, place-based interventions, digital art, sound art, and more.

Public art includes permanent, temporary, and ephemeral installations.

Monuments, as well as memorials, were defined as objects or spaces designed to honor people who have passed; and places, moments, and significant events from history. We included roadside memorials in this dataset.

Inspired by conversations exploring equity and spatial justice in the City of Indianapolis, we designed this inventory and analysis to answer the guiding question: “How can Marion County create more equitable public spaces for all?”

Public spaces are not accessible nor welcoming to all, as we see people of various ethnicities, creeds, and lifestyles being persecuted in public spaces. Our collective challenge is to reassess how we see, utilize, and design public spaces that are truly inclusive and sustainable.

All public spaces in Marion County will be safe, accessible, welcoming, easy-to-use, and flexible for anyone regardless of their personal or cultural characteristics.

Our communities shape us just as we shape our communities. In order to exist within spaces that reflect our desires, express our passions and celebrate our sensibilities, we must consider the distribution of public resources in showcasing the complexity of social and cultural differences. To that extent, spatial justice in this report adopts the definition by urbanist and expert geographer Dr. Ed Soja as “the fair and equitable distribution in space of socially valued resources and opportunities to use them.” 1

A collaborative network of arts advocates have a shared vision that a resident’s or visitor’s assumed race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity, physical ability, income level, or culture will not predict their public space experience.

Public space, and the activities that happen in it, will not deny anyone’s humanity or minimize their story.

The structural and systemic racism inherent in how public space has been conceptualized, developed, and managed to date will no longer be allowed to continue.

Groups that have been historically and structurally marginalized because of their perceived race, including (but not limited to) Black people, non-White immigrants, and American Indians, will be able to frequently encounter public art, monuments, memorials, and historic markers in the public spaces they move through.

These spaces will host artwork that respects and reflects their history, culture, contributions, lived experience, and values. These artworks will be created by artists from their own communities.

Further, the public art that they see will not voluntarily or involuntarily contribute to their emotional harm, ignore their perspective, or present a narrative that is inconsistent with, miscasts, or directly contradicts provable facts.

Finally, anyone with an interest in what happens in public space shall have the right, power, and voice to provide meaningful input into what they see, hear, and experience in public.

1. Soja, Ed., The City and Spatial Justice, 2009 p17

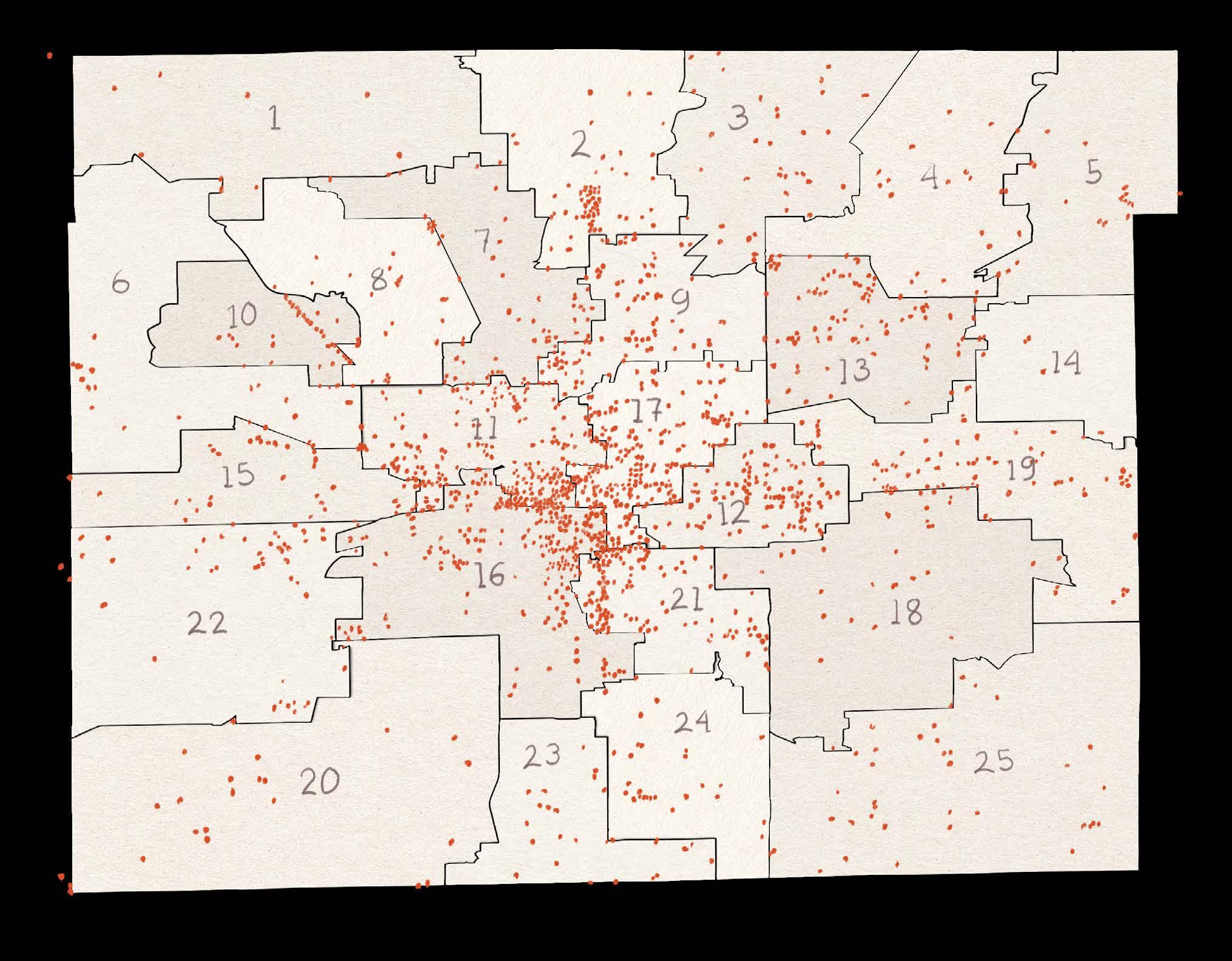

A total of 3,090 artworks were identified countywide. pages 22 & 23

The average condition of the artwork across the County is “GOOD.” pages 35 & 37

The authored artworks underrepresent artists of the global majority and women. page 32

18 artists account for 35% of the authored artworks. page 29

The most prevalent public art form across the County is murals, but they are also the least invested in. pages 50, 63, 67

Public art deserts have been defined and identified across the County. page 42

Roadside memorials are illegal in Indiana, but they outnumber traditional monuments and memorials. page 71

ESTABLISH support networks that assist artists in properly archiving their work, beginning with adequate signage notating the author and date at all public art sites.

page 30

BROADEN the style and spatial imagination of work associated with the built environment to ensure greater overall exposure to people of varying cultural backgrounds.

page 46

ENGAGE with artists and communities of various backgrounds, lifestyles, and abilities to generate a more socially and culturally diverse and physically accessible public art landscape.

page 33

CONDUCT a regular census and inventory of public art within the County. This is a necessary investment in the infrastructure and quality of life of residents.

page 38

page 43

EXPAND the Public Art for Neighborhoods Program beyond TIF districts and examine identified public art deserts for opportunities to activate public art within these areas.

EXPAND the definition of public art to continuously make room for and acknowledge work that highlights inclusive, accessible, and representative creations of the community.

page 48

SUPPORT existing public art efforts at the hyperlocal level. Specifically, partner with community centers and learning sites to equitably engage creatives of all backgrounds and abilities.

page 61

Between May and August 2021, a Rokhassembled team scouted roughly 6500 linear miles across Marion County, IN, cataloguing the artworks visible from the public right-of-way. This research and analysis was not limited to city-owned works; we looked at all creative (non-store bought), non-obstructed expressions within the built environment, including monuments, memorials, little free libraries, and roadside memorials. Along with the scouting, we reviewed public art records and County sources. Some data sets were not used if they were in the process of being updated or if they were invalid during the period of our review.

Using customized open source applications, we catalogued all of the works by a set of primary characteristics including a photograph, type, typology, creator, and coordinates.

We reviewed 12 key areas of civic and GIS spatial data, including: ethnicity, gender, crime, income, homeownership and rentership, education levels, schools/colleges, walkability, transit, and greenspaces. Part of this process required parsing and mapping data across multiple data sets. These data sets contained omissions, deficient information, and technical inaccuracies through which our team worked to cross-reference, condense, and analyze.

Our research team used this metadata to uncover trends relating to accessibility and preliminary understandings of equity across the public art population within Marion County. In reviewing our compre hensive data set, we detailed voids and gaps to underscore opportunities for a more inclusive public art landscape.

The objective of this inventory is to be the second phase of a four phase endeavor, building towards a public art equity audit. You are here, at Phase 2: CENSUS, which seeks to establish a baseline inventory and analysis. This data will broaden the defi nition of public art within the County, establish a countywide framework for identify ing and cataloguing a more inclusive and widened listing of public art, and generate spatial analysis of the data to detail the role of public art in ensuring equitable public spaces. Future phases include community conversations about CENSUS findings, and actions to help increase equity and spatial justice for public art. To learn more about the other phases of the comprehensive public art equity audit, visit

The information in this report is broken down into 3 key areas:

Asian A person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Middle East, Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent. Including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Black/African American A person having origins in any of the Black ethnic groups of Africa.

Indigenous American A person having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America (including Central America) and who maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment.

Latino/a/e/ A person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture of origin.

Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.

White A person having origins in any of the original territories of Western or Eastern Europe.

Global Majority Persons who are Asian, Black, Indigenous, Latino/a/e, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.

LGBTQIA Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual

Note: This report employed census guidelines for categorizing race and ethnicity in order to compare the demographics of Marion County, IN and the United States. It is important to note that, as the Census guidelines state, these categories are not an attempt to define race biologically, anthropologically, or genetically. Our language however, centers people and attempts to honor their humanity.

O S SA RY O F T E R M S

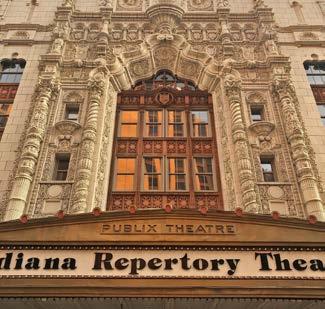

Architectural Aesthetic structures with unique details and component parts that, together, form the architectural style of a building facade.

Built Environment The humanmade elements of our lived experience that form the background or setting of our experiences.

Graffiti Writing or drawings made on a wall or other surface, often but not always, within public view and typically without permission.

Hand-Lettered Sign Signs for which the text is drawn by hand, rather than mechanically printed.

Installation Large-scale, mixed-media constructions, often designed for a specific place or for a temporary period of time. This definition does not conform to the traditional museum/fine arts definition of installation. Rather it is a 3-D multifaceted architectural, spatial, experiential display, including, among other forms, traditional and contemporary sculpture.

Intervention An action taken to improve a situation.

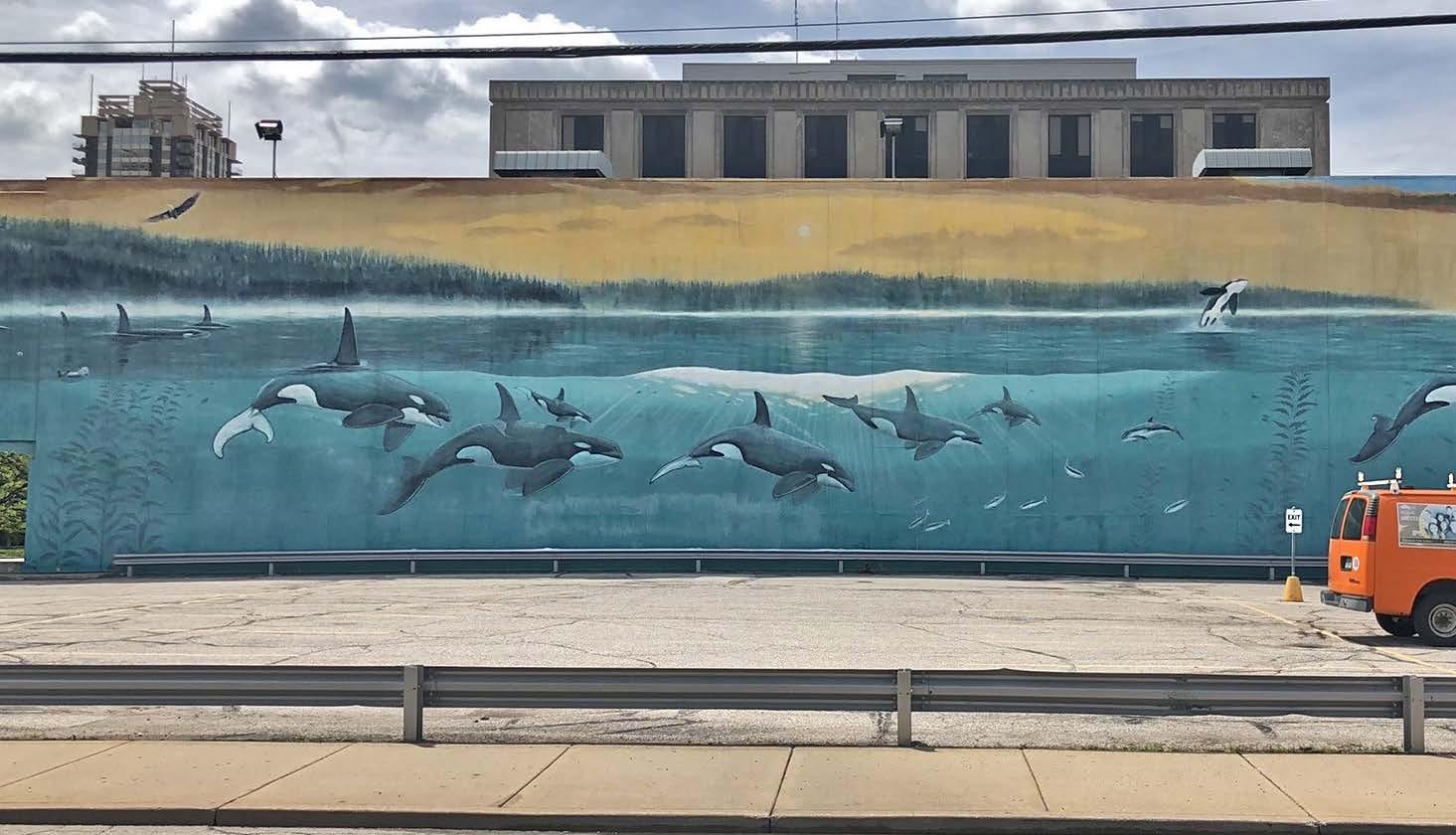

Mural Any piece of artwork painted or applied directly on a wall, ceiling or other substrate.

Placekeeping Engaging the residents who already live in a space, and allowing them to preserve the stories and culture of where they live.

Public Art Desert An area with a median family income not exceeding 80% AMI and no artwork within 1 mile (or) an area where there is no artwork within 1 mile.

Right-Of-Way (ROW) Streets, sidewalks, or greenspace publicly owned and for public use.

Roadside Memorial A resident-led commemorative marker typically along a public road or street.

Spatial Justice The fair and equitable distribution in space of socially valued resources and opportunities to use them.

Stained Glass Colored glass used to form decorative or pictorial designs.

Tactical Urbanism A city, organizational, and/or citizen-led approach to neighborhood change using short-term, low-cost, and scalable interventions to catalyze long-term change. Interventions include art-based approaches such as painted intersections and artistic wayfinding.

Tax Incremental Financing (TIF) A geographically targeted economic development tool that captures the increase in property taxes (and sometimes other taxes) resulting from new development, and diverts that revenue to subsidize that new development.

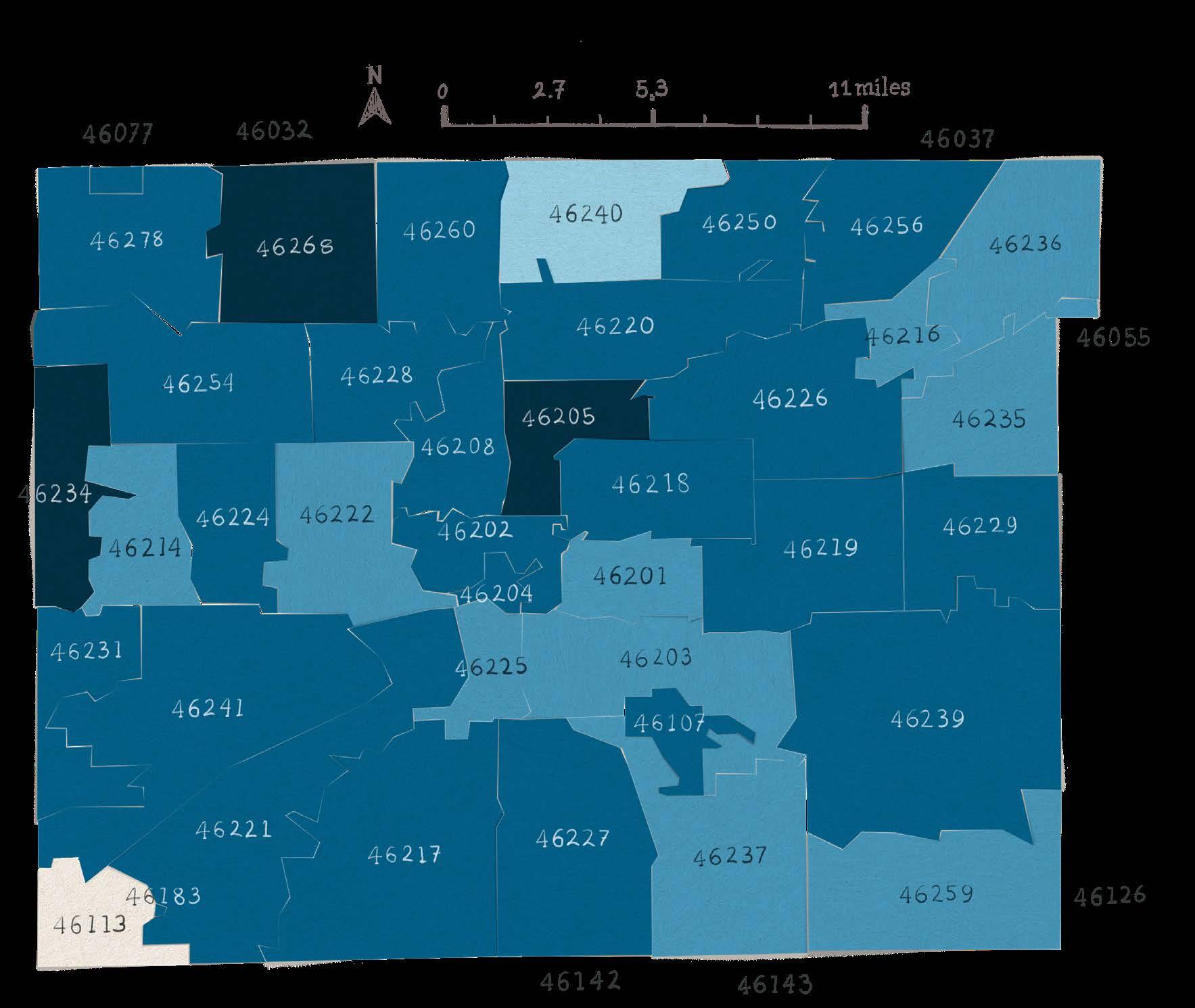

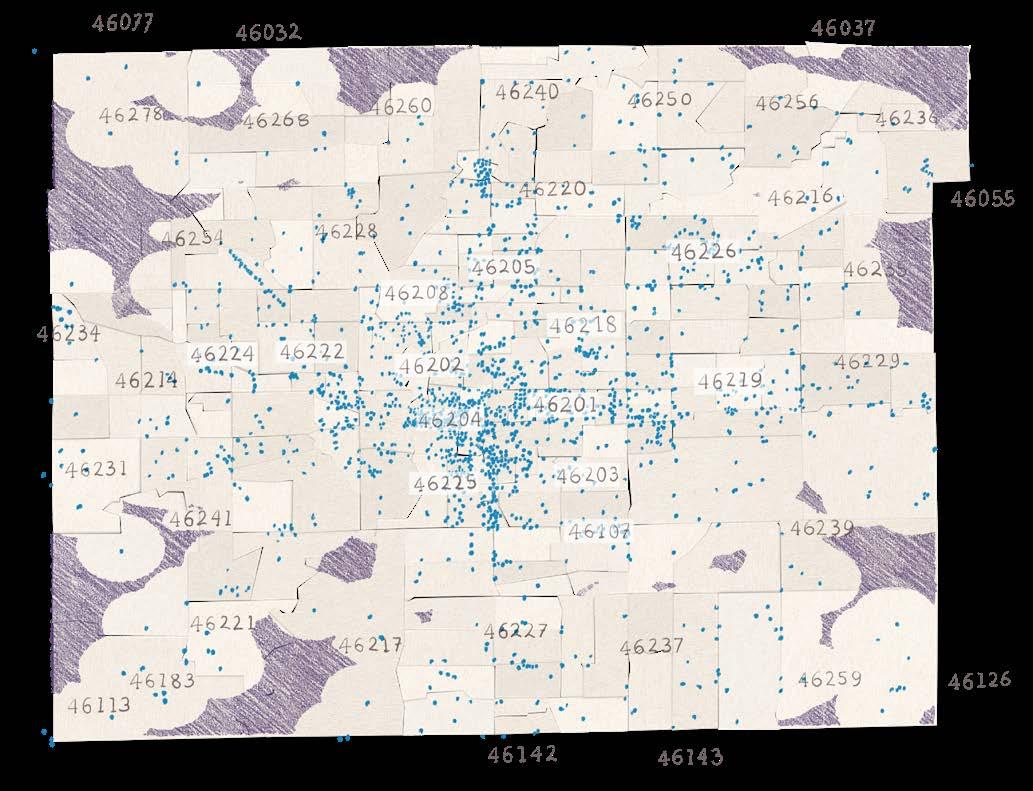

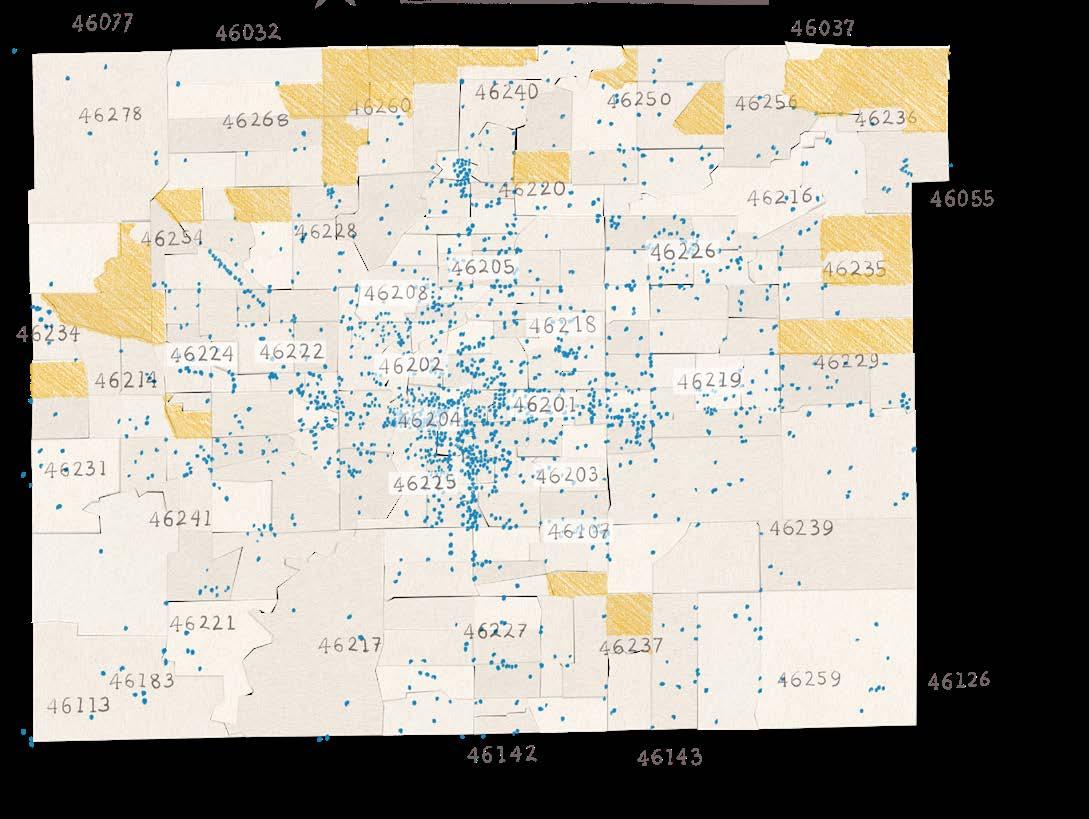

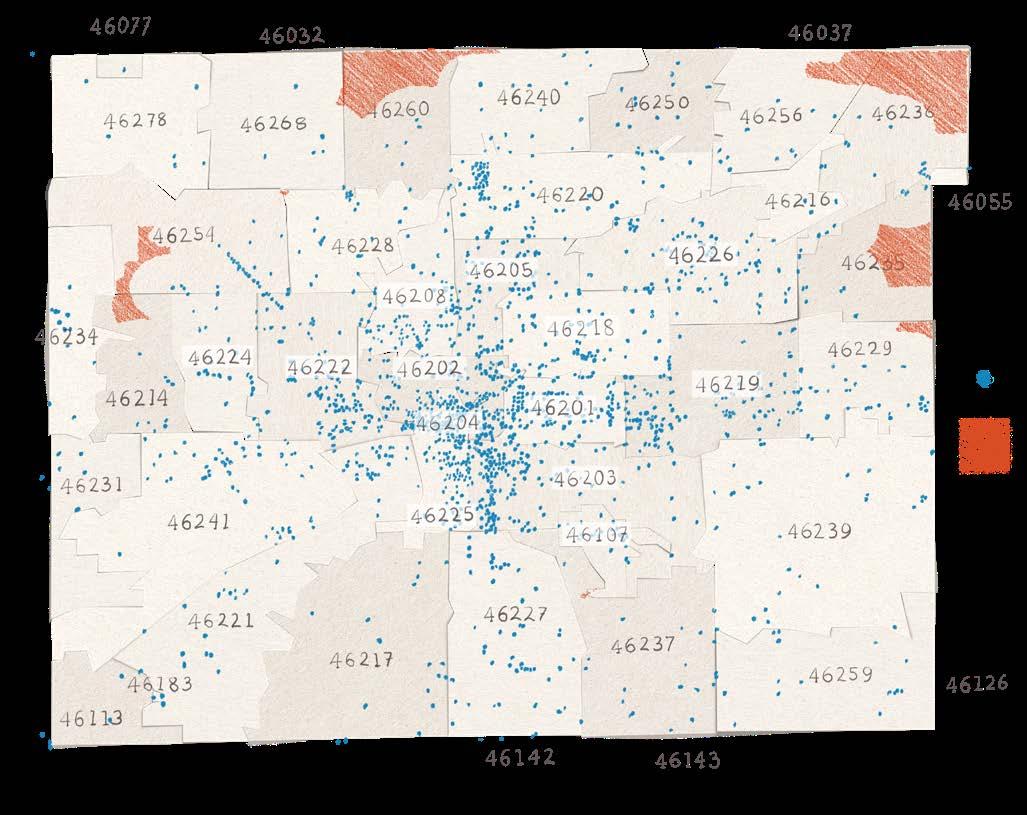

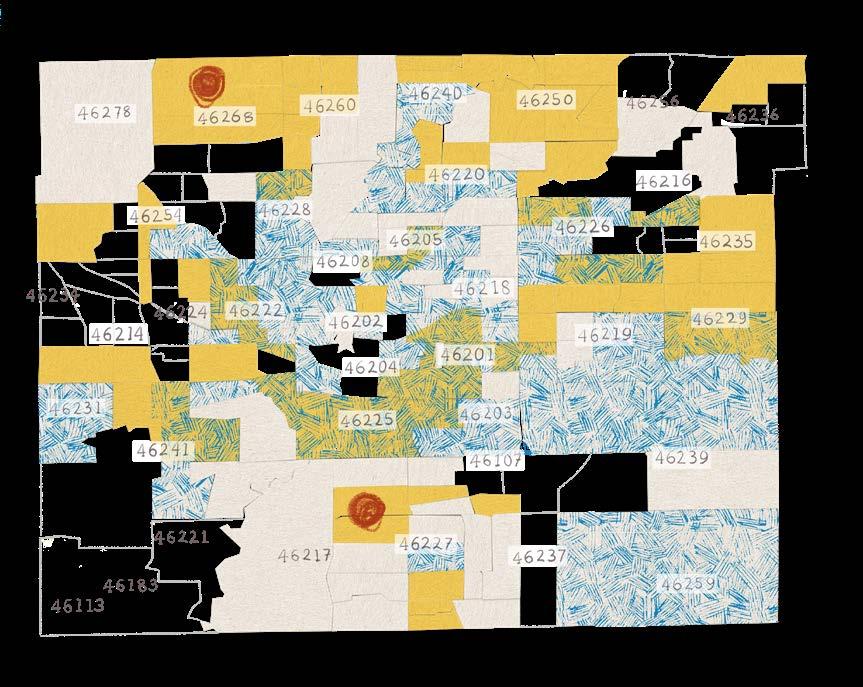

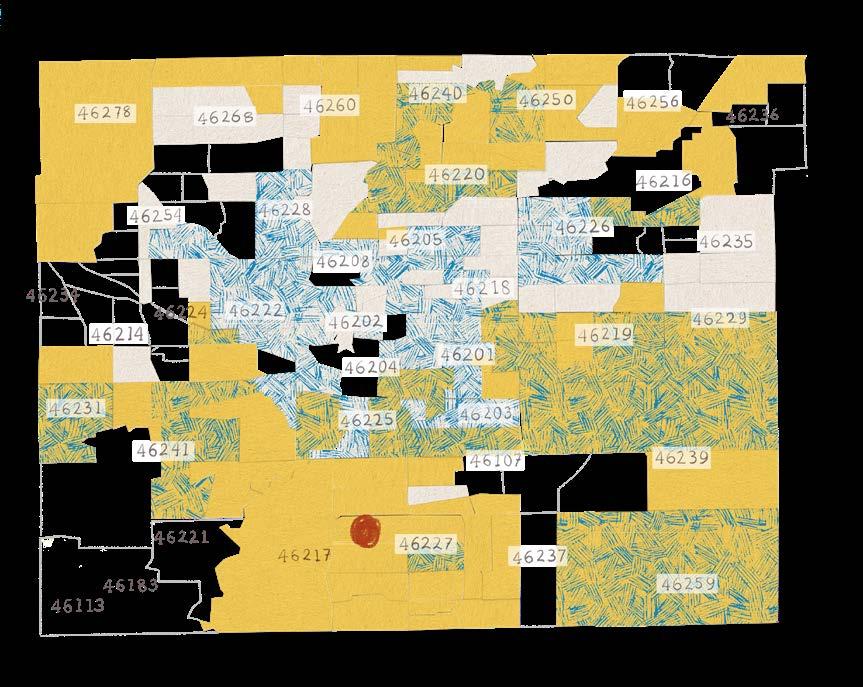

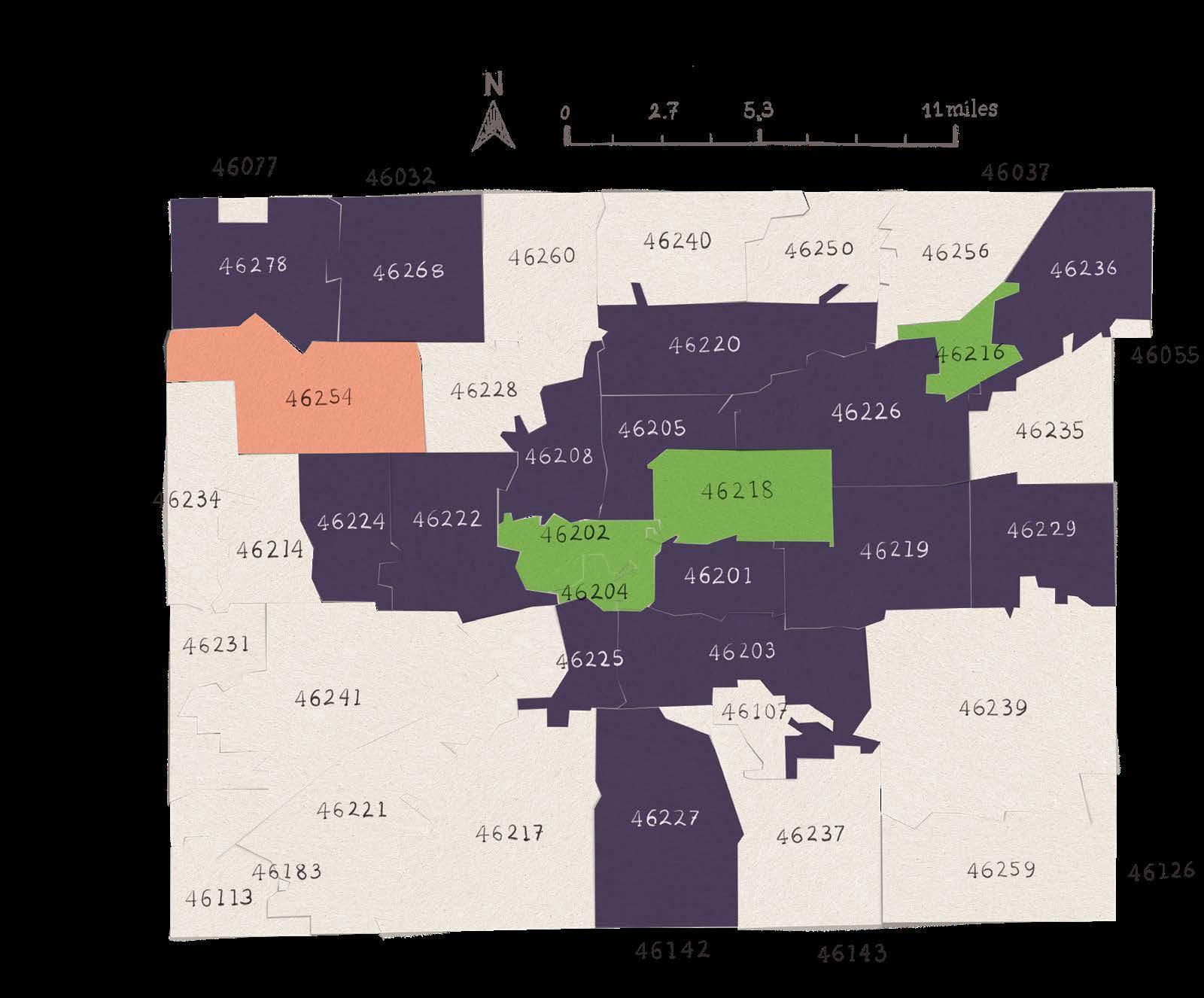

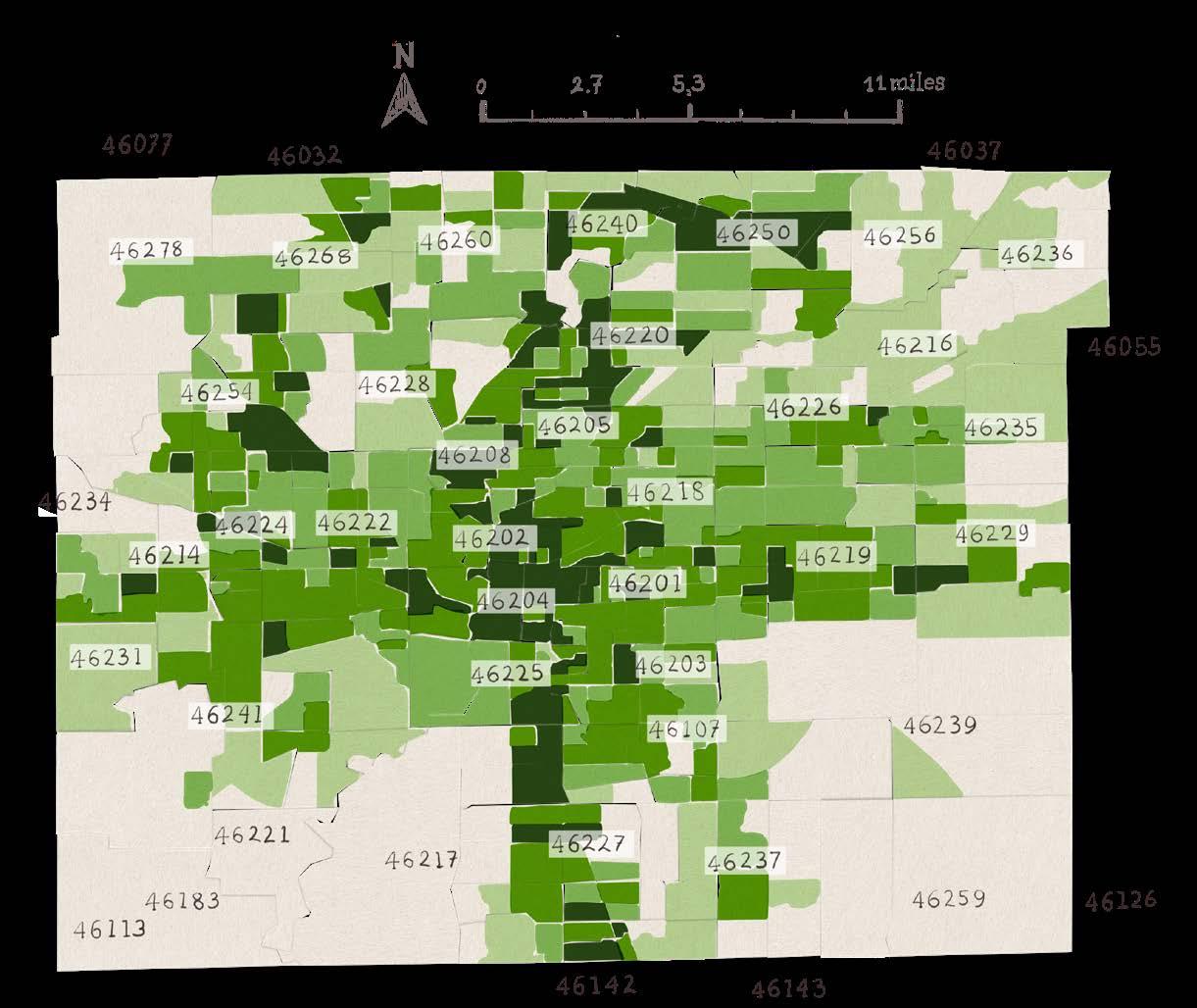

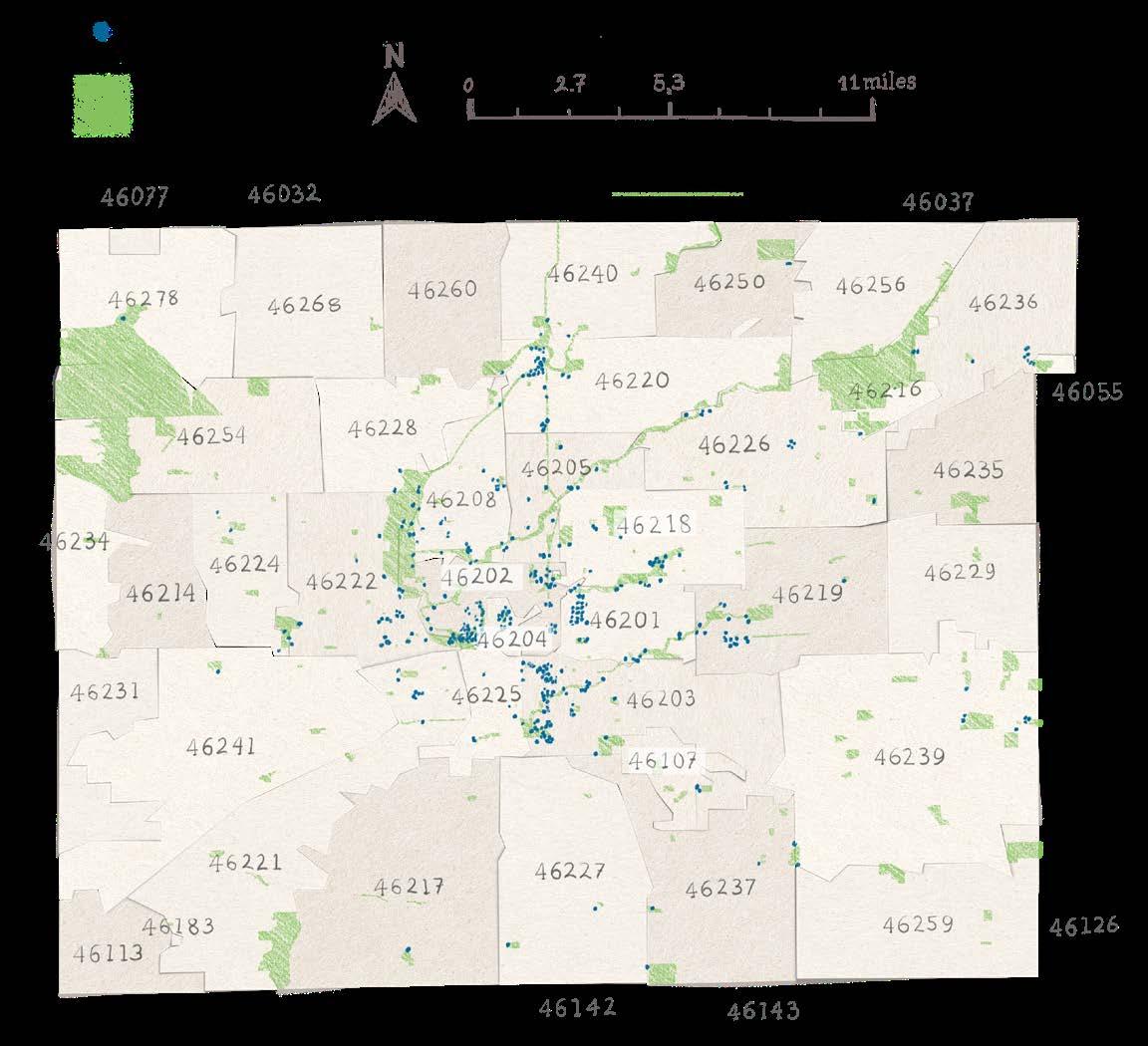

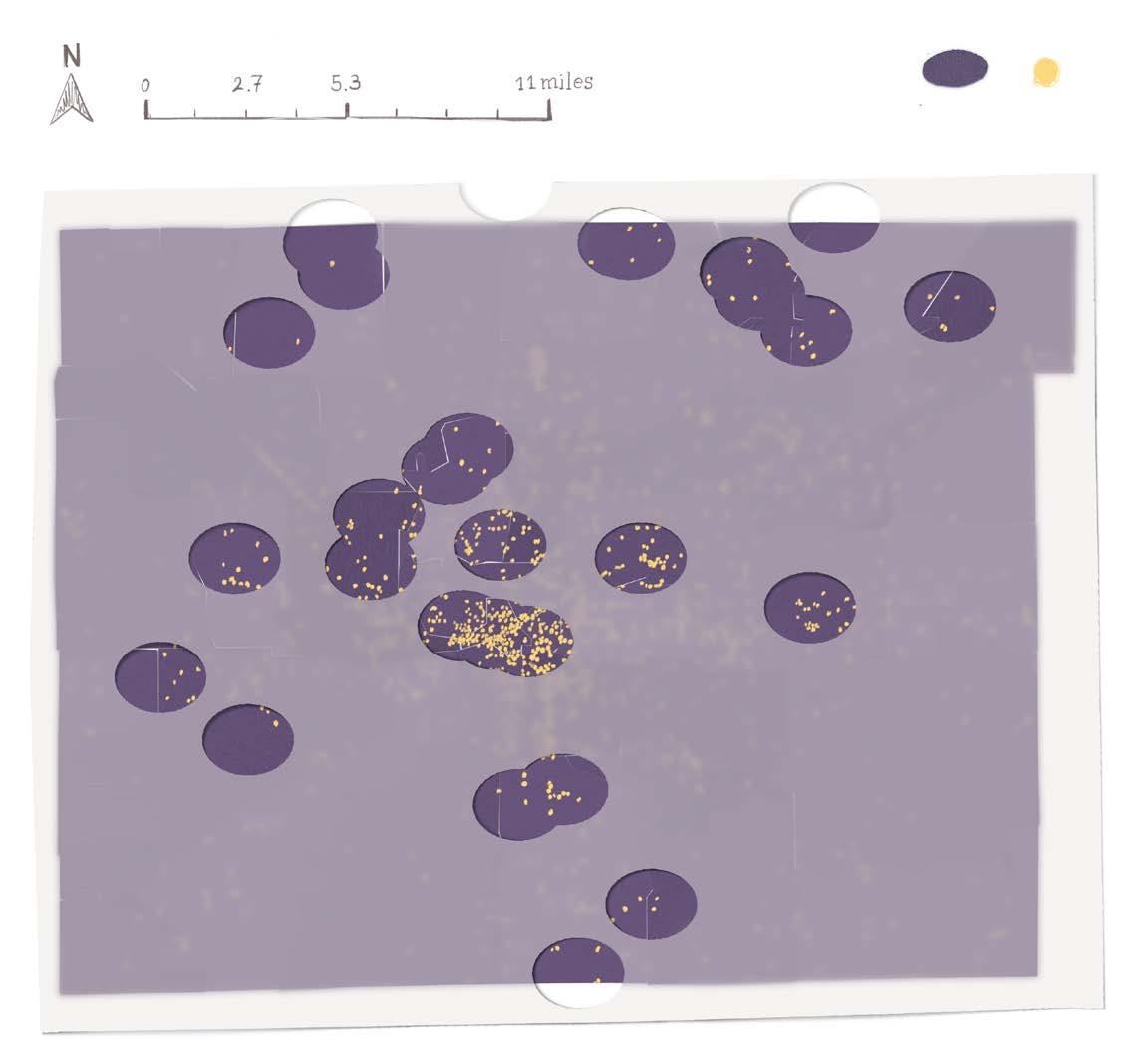

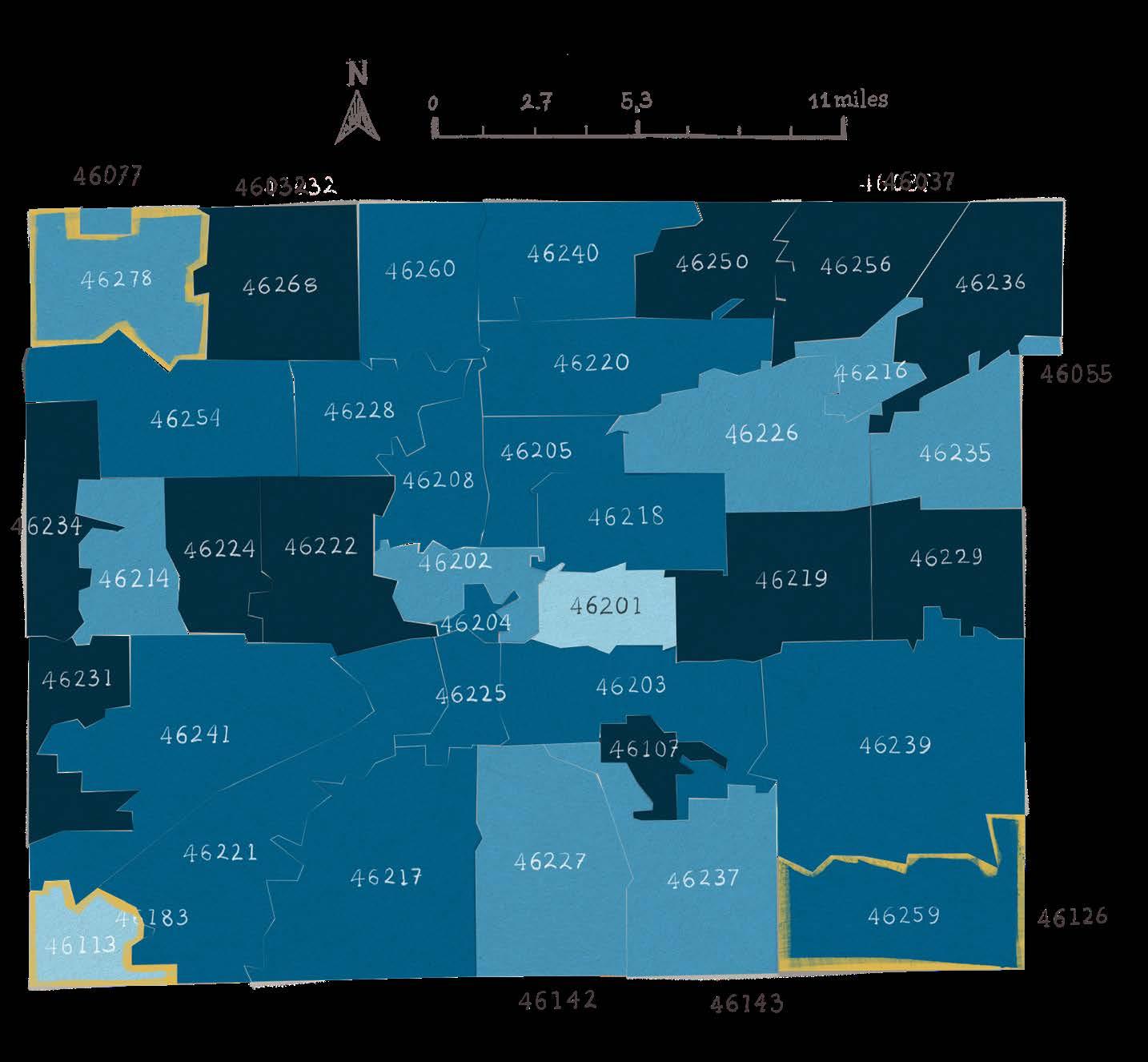

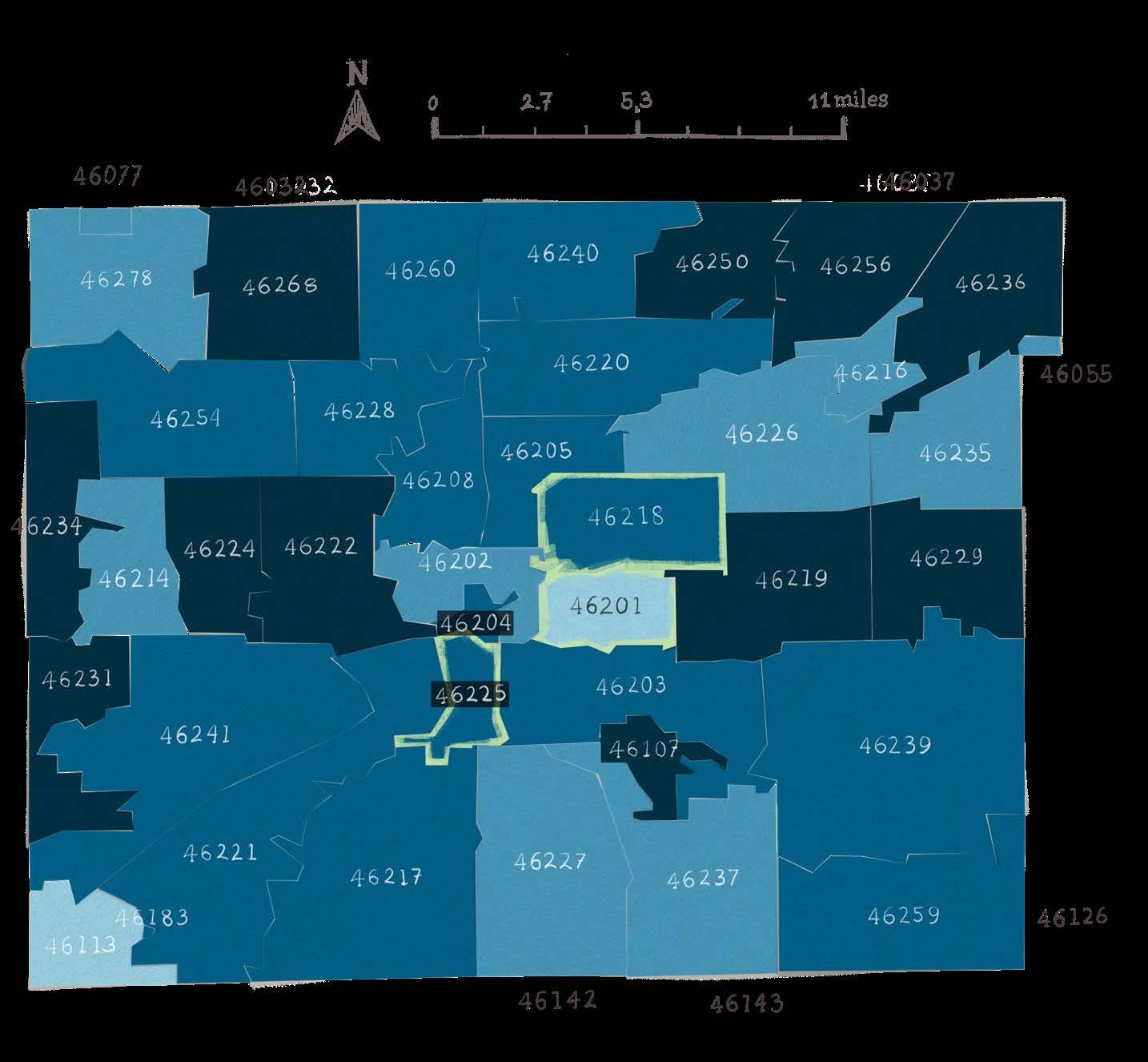

Most of the data throughout this report is provided at the zip code level. Use the map below for ease of orientation and comparison.

3,090 works within this data set = 1 public artwork

Reach out to your City-County Council representative to advocate for public art in your area.

3,090 works within this data set = 1 public artwork

As of August 2021: 3 , 0 9 0 A R T WO R KS I D E N T I F I E D

From May 2021 to August 2021, our research team assessed and inventoried all visible public artworks along major, local, and minor public roads and streets across Marion County, Indiana. The scouters did not traverse any private roads, streets, or properties, nor any closed roads. We did not capture items that were visually obstructed; however, artworks on private roads were captured if the work was visible from the public right-of-way (ROW). The research team did not enter public or private establishments; however, if work located inside public establishments was visible from the public ROW, those sites were catalogued.

At the time of this study, many new works were underway. Due to the unidirectional scouting pattern, this data set may not include any work that was started or completed after the scouting pass was conducted.

MURALS 1,299

INSTALLATIONS 1,079

HAND-LETTERED SIGNS 177

ARCHITECTURAL 158

GRAFFITI 109

STAINED GLASS 80

ROADSIDE MEMORIALS 66

TACTICAL URBANISM 13

Visual samples of each type can be found on page 27.

Title Unknown | Artist Unknown 9623 Pendleton Pike, Indianapolis, IN

The Indy Arts Council maintains a public art directory (PAD) within Marion County and contiguous surrounding counties (Hamilton, Hendricks, Johnson, Shelby, Hancock, and Boone). At the time of this inventory, the PAD had a listing of 847 public artworks. Of those, 616 were within Marion County. The challenges inherent to the PAD include: lack of consistent outreach to the various regions across the county, creators being unaware of the database to share their work, the limited definition of public artwork, and low staff capacity to update the PAD in real-time. The term “creator” is being broadly defined here to underscore that the makers of art hold limitless identities. This inventory was designed to unearth artworks with this in mind.

Mural Any piece of artwork painted or applied directly on a wall, ceiling or other substrate.

Installation Large-scale, mixed-media constructions, often designed for a specific place or temporary period of time. 3-D, multifaceted architectural, spatial, experiential displays, including traditional and contemporary sculpture.

Hand-Lettered Sign Signs for which the text is drawn by hand, rather than mechanically printed.

Architectural Aesthetic structures with unique details and component parts that, together, form the architectural style of a building facade.

Graffiti Writing or drawings made on a wall or other surface, often but not always, within public view and typically without permission.

Stained Glass Colored glass used to form decorative or pictorial designs.

Roadside Memorial A resident-led commemorative marker typically along a public road or street.

Tactical Urbanism An approach to neighborhood change using short-term, lowcost, and scalable interventions, such as painted intersections and artistic wayfinding.

Our inventory uncovered that of the 3,090 works, only 537 of them were marked with an artist name. The act of signing one’s work is crucial to having an accurate account and equitable distribution of resources.

Just 18 artists account for 35% of the signed data set, and have each done 5 or more works across the County. A public art population that has been created by so few artists brings to light concerns of exclusionary expression, inequity in the distribution of funding, and lack of content diversity.

537 PUBLIC ARTWORKS include artist signature

18 ARTISTS account for 35% of the signed data set

KEY POINT Lack of adequate on-site signage creates a historical gap in information about the contributors to our built environment.

Across the 18 Artists...

8 artists account for 5 works

4 artists account for 6 works

1 artist accounts for 7 works

1 artist accounts for 9 works

1 artist accounts for 10 works

1 artist accounts for 11 works

1 artist accounts for 24 works

1 artist accounts for 43 works

Signage is crucial for a functional public art collection and archive. The requirements for sanctioned signage can be a cumbersome process for an artist/arts group at the completion of a new public artwork. With this in mind, we suggest placing more emphasis on the value of creators signing their work. We also suggest the creation of a signage guide that assists artists/arts groups in maneuvering the process of designing, laying out, and installing sanctioned signage on site.

To encourage an equitable public art landscape, creations should be physically accessible, feel relatable, and seek to embrace the differences within their host communities.

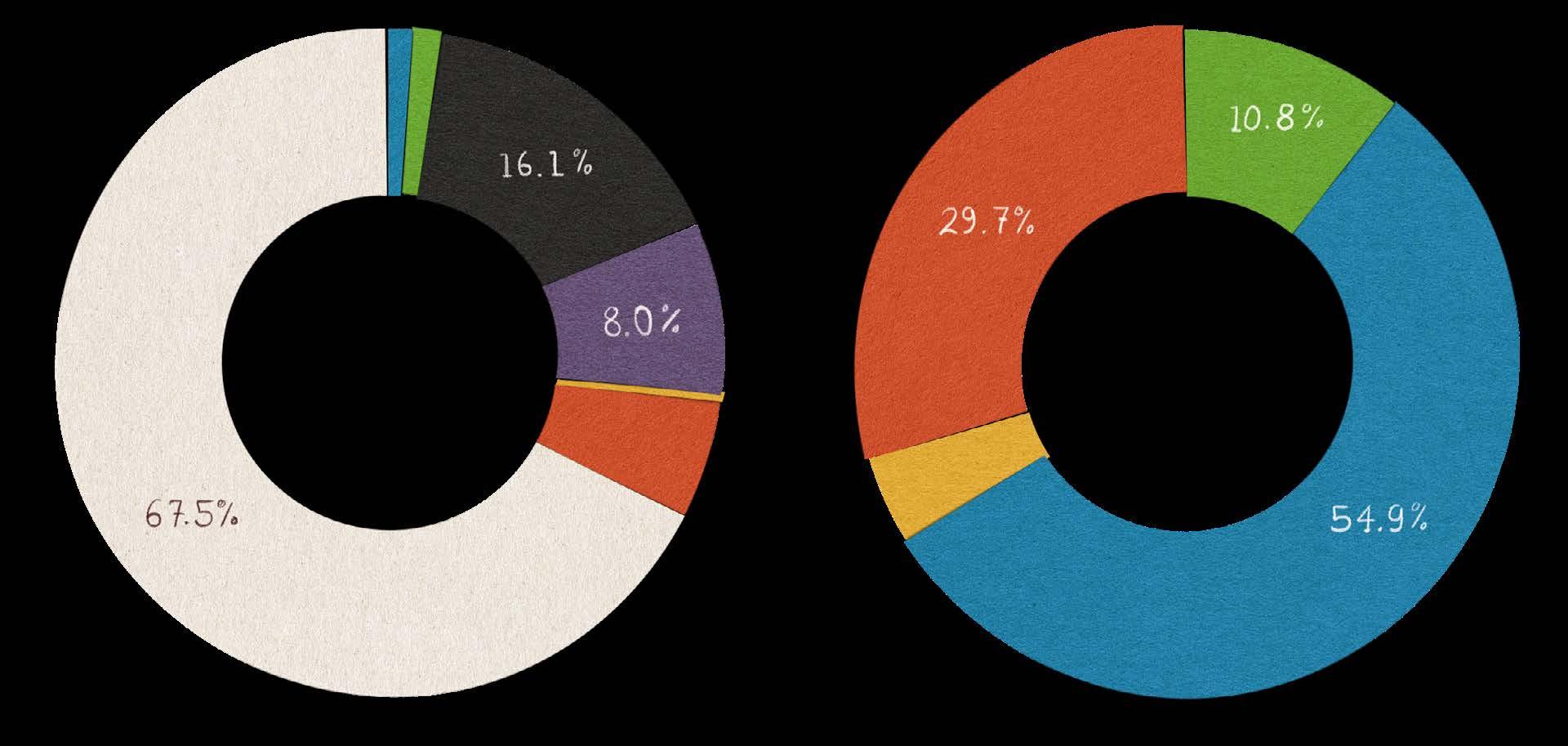

Figure 1 below details the ethnic composition of the artists who created the 537 works for which a name was available. We acknowledge that these are sitebased observations and may not align with how the artists self-identify.

The majority of the 537 works were completed by White artists (67.5%) and men (54.9%). Black artists account for 16.1% in comparison to a 29% County population. Latino/a/e artists account for 8% of the works compared to a 10.9% County population. Figure 2 indicates that women comprised only 29.7%; although they outnumber men by 7% countywide.

We also found that a significant portion (over 10%) of the works are completed by groups (Fig. 2). The significant rate of group work could be a method for artists to build internal capacity, share knowledge, and practice resource sharing in an effort to reduce the cost burden of supplies and labor.

KEY POINT A disparity exists with the rate to which women and creators from the global majority are engaged countywide.

Note: An artwork may be completed by a pair or group of artists (M/W and/or different ethnicities) and therefore represent multiple identities, so percentage exceeds 100% out of 537 artworks. We acknowledge that gender and ethnicity are not static and thus our observations may not align with how the artists self-identify.

The talent pool within Marion County is vast and spans people of distinct cultural backgrounds, abilities, beliefs, and aesthetic tastes. Black, Latino/a/e, Asian, and Indigenous residents as a global majority account for 47.2% of the County population but as creatives, collectively, they only account for 26.5% of the works found.

Inviting and supporting more community members towards the creation of public art will spur engagement and generate more artistic styles.

1

Less than 5% surface area damage

Public artwork, like other elements of the built environment (such as roads, highways, water supplies, and transit) requires upkeep and maintenance.

When gathering the data points for this inventory, our study documented the condition of each artwork based on several criteria, primarily surface area damage. This included evidence of weathering, chipping, and/or defacement. Each site was ranked on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being the worst and 5 being the best.

While the average overall health is "good," nevertheless, the most frequently observed condition of individual works was “fair," and this observation should spur action. Without a dedicated plan to address public art maintenance, works will continue to deteriorate, causing potential damage to surrounding infrastructure and, more importantly, weakening community spirit.

Reviewing the condition across the County, one area of note is the zip code of 46205 (considered one of the County's most "dangerous"). Known as United Northeast, 46205 is one of the three zip codes across the County where the average condition of the artworks is "excellent." However, robberies in this zip code are 42% more likely than in any other zip code in the County. This report did not have access to dates in order to cross reference years of public artwork with crime incident archives.

One may expect that a high crime area would have work in poorer condition, equating high crime with lack of care. However, our findings present a different possibility. The percentage of public works found in good condition within communities battling higher crime rates could be attributed to newer works in the area as crime prevention measures, or perhaps, to the caretaking residents offer their surroundings.

While the overall condition of the Marion County public art collection is rated as “GOOD” (defined as having 11–20% surface area damage), there are many public artworks that are deteriorating and in need of repair. We suggest implementing a source of funding that supports a neighborhood-led approach to tracking and improving the health, physical condition, and vitality of the artworks across the County.

Public art is a driver for both tourism and quality of life. As such, we also suggest a city-based investment to support a biennial countywide public art inventory and analysis to catalogue new works and determine ongoing maintenance needs.

Public art should be available to all, regardless of means or physical ability.

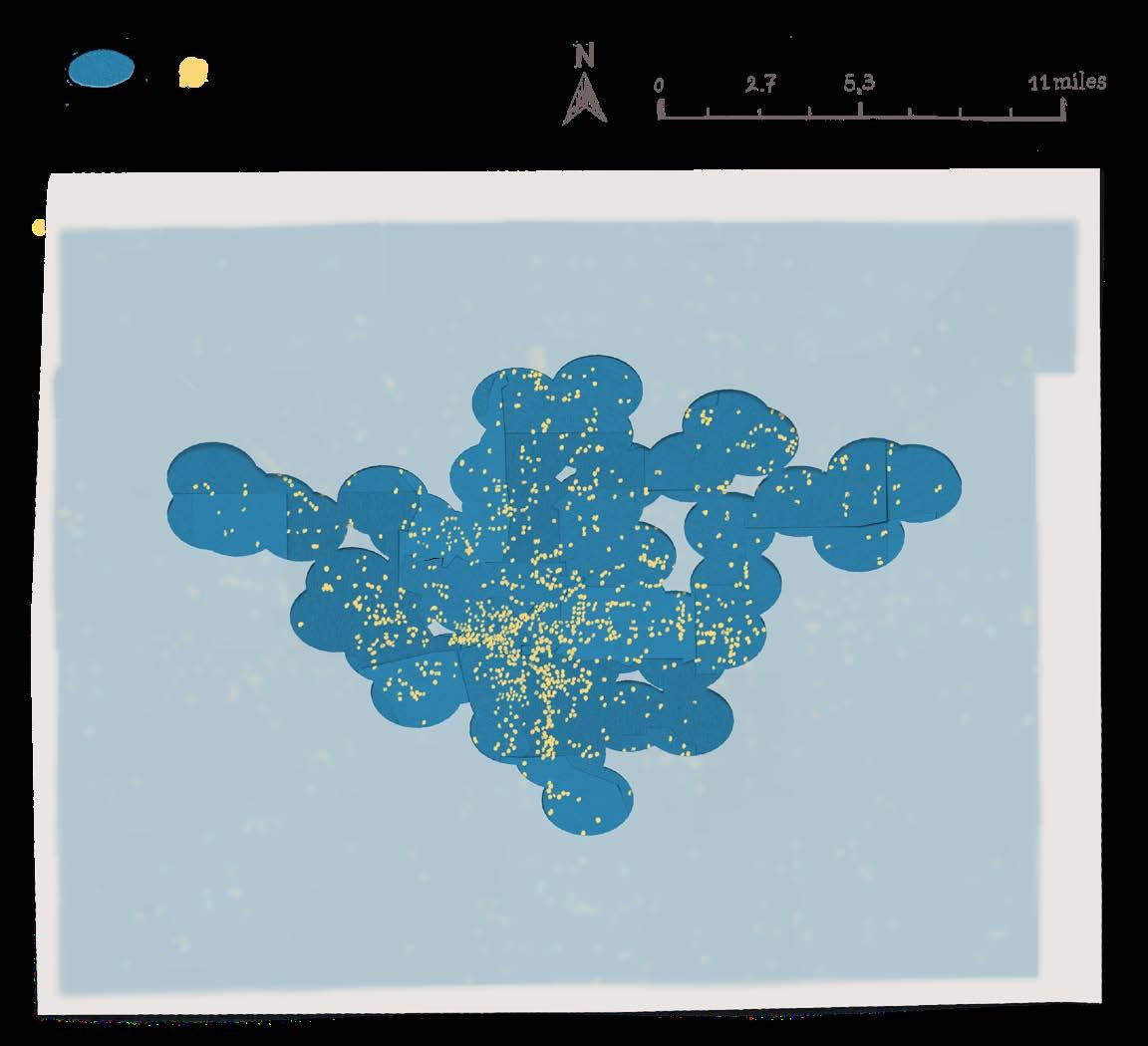

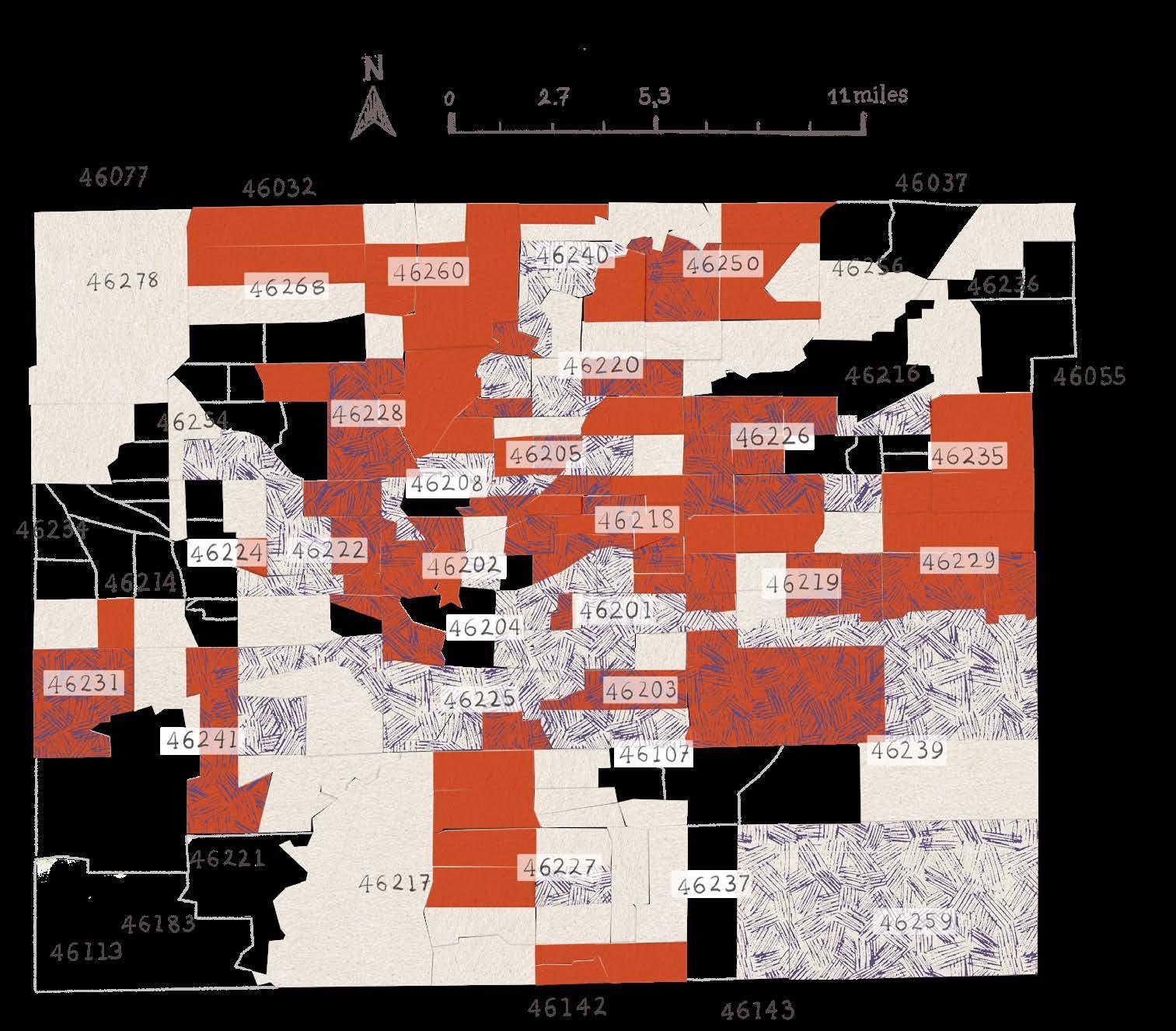

It's often assumed that public art is everywhere, but this is a myth and not the case universally (see Appendix Fig. 2, 3, and 4 for more data regarding artwork density and socioeconomic variables.) While this report identified a large number of artworks across the County and many along public transit lines, there were a considerable amount of areas still lacking accessibility to public art. These zones are known as "public art deserts." We identified three distinct types of public art desert: The first (Fig.4) is an area where public artwork is completely unavailable. The second, a semi-desert (Fig. 5), is a zone where public artwork is not accessible within 1 mile. And, the third (Fig. 6) is a zone that has less than 80% area median income and no artwork within a mile.

In public art deserts Types 2 and 3, artworks were more readily found at daycares, schools, and residential areas. We attribute this to intersectional issues of lacking public transportation, mobility, and connectivity which prevent residents from easily accessing public art. Thus, their sites of daily use, such as daycares and schools, have been activated to support the desire for creative expression and community care.

Policies and programs that result in commissioned public art are not widely known by all. Communities on the periphery of the County are eager to have representative and culturally relevant artworks near their live/work/play spaces.

Engaging with these areas will aid in community resiliency. This could justify infrastructure improvements in marginalized areas, ultimately prompting new policies that broaden the content of the region’s public art collection.

Conventional wisdom proposes that public art can act to reduce crime by instilling a sense of pride and “ownership” among the residents of a community. To test this assertion, our inventory collected crime data for the 46205 and 46208 zip codes (both predominantly Black) which are considered two of the "most dangerous" in the United States. We compared the crime data to several other metrics gathered during our census.

Contrary to public sentiment, the data shows that these two perceived "most dangerous" zip codes, statistically, were actually not the zip codes with the most crime. The zip codes with the most crime were 46201 (predominantly White) and 46218 (predominantly Black).

Perceived most dangerous (predominantly Black zip codes)

with statistically more

The condition of work in 46205 is rated as "excellent" and the condition of work in 46208 is rated as "very good." These findings suggest the need for a debunking of the stereotypes placed on dense Black urban communities. They also complicate assumptions of how residents in high crime areas treat their surroundings.

A common assumption is that areas with higher crime will have artwork in poorer condition. On the contrary, our inventory highlighted that on average, art in zip codes with high crime ranked in "fair" rather than "poor" condition. Studies show that marginalized neighborhoods have experienced structural disadvantages that may have directly led to high crime rates.1 Public art may act as place-based interventions to alleviate such pressures.

Studies show that communities with high crime are also divested communities with crumbling infrastructure, higher poverty rates, and strained social networks. Investing in neighborhood stabilization programs that center and fund creative placekeeping could stimulate economic circulation while incentivizing the skills and talents of neighbors. Activating areas of high crime has the potential to reduce negative activity and signal care and surveillance of place.

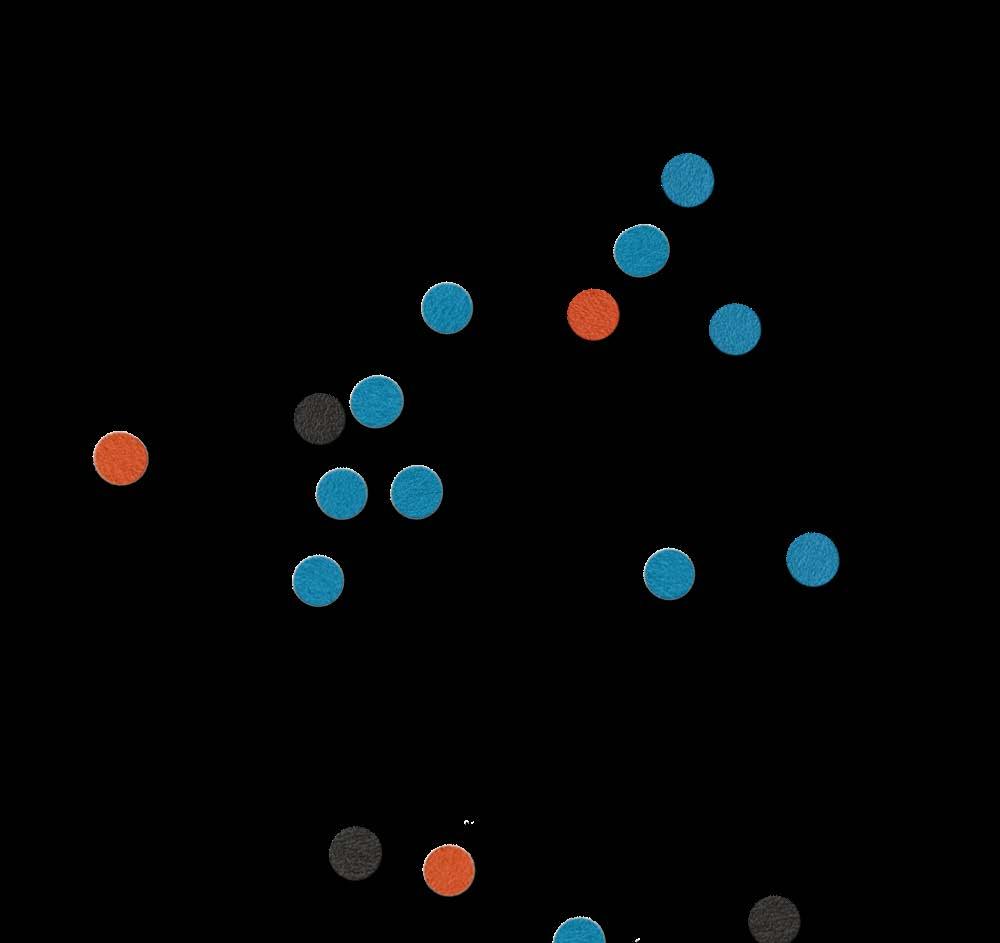

Conducting a spatial comparison of public art to ethnic concentration of County residents, we identified areas of overlapping density to determine the opportunities for different demographics to access public art.

The maps below illustrate, at the census tract level, a public art gap on the periphery of the County when race is specifically considered. We defined a “gap”

High ethnic concentration

High public art density

as the space where there is a high percentage of a particular non-White ethnicity combined with low density of public art in that area. Density is measured by the quantity of public artwork within the boundary, in comparison to the County. All of these “gap” areas, moreover, are regions that are classified overall as public art deserts (further defined on page 42).

High ethnic concentration + low public art = area for investment

Insufficient data

Asian residents comprise 3.8% of the Marion County population. Figure 9 shows that Asian residents have a strong presence in the northwest and south central regions, where is relatively low availability of public art.

Latino/a/e residents comprise 10.9% of the Marion County population. This map shows opportunity zones for public art investment in the south central and the northwest regions, similar to Figure 9.

Black residents make up 29.1% of the Marion County population. Figure 10 shows that Black residents have low accessibility to public art in the central west and the northwest regions.

White residents comprise 63.5% of the Marion County population. The south central area, as is common to most groups, has little public art availability to the White population as well.

Art can act as a disruptor to harmful power dynamics. Investing in both art and artists in ethnically marginalized communities generates economic impact, establishes visual presence, and cements cultural memory of who resides within a community.

We recommend two distinct agendas. The first is enacting policies that seek to hire local creators who are caretakers within these areas. The second is to develop guidelines that support the incorporation of public art that acknowledges the history and heritage of a neighborhood.

Physical and cultural accessibility to a wide range of art types is important to building a spatially just public art landscape.

Figure 13 shows the majority type of work found within each zip code across the County. Indianapolis, the largest and most populous city within the County, has more monuments than any other city in the United States besides Washington, D.C. During our inventory, we uncovered that roadside memorials are even more prevalent

KEY POINT

in Marion County than traditional monuments and memorials. Most traditional monuments and memorials in Marion County are dedicated to men and war. Roadside memorials, as an alternative, may be dedicated to anyone and for various reasons. This indicates that these sites may be a testament to the desire of local residents to acknowledge people and places that are more meaningful to their lived experiences than traditional memorials and monuments. Although roadside memorials are not permitted in the state of Indiana, we recommend that consideration and protections be given to this type of memorialization in an effort to honor resident engagement.

The ability to experience art across a variety of public places is crucial to addressing the question of accessibility.

While Percent for Art programs were first established in 19591, it's becoming a growing trend in larger cities to find public artworks at newer, privately-owned buildings or spaces that are taking advantage of development incentives.2 These incentivized Percent for Art or public art in private development programs, can lead to artwashing, which is a tactic traditionally but not exclusively used by corporations and developers to enlist cultural capital to rebrand an area, or attempt to associate one's corporate reputation with the positive benefits of art. Without careful attention, artwashing can lead to exploitation and displacement in diverse communities.

This report accessed the various topologies where artworks were found across Marion County, with the primary categories being Residential, Commercial, Religious, Fencing, Schools, Hospitals,

*County Infrastructure consists of underpasses, bridges, bus stops, utility boxes, traffic signal boxes, the curb, light poles, roadside memorials, and the like.

Daycares, Community Spaces, Parks/ Greenspaces, and County Infrastructure.* This inventory did not survey ADA compliance or physical accessibility at sites.

Indianapolis has had a version of a public art in private development program since 2016. As such, this inventory forecasted that public art would most frequently be found at retail/ commercial sites and private developments (see Figure 14 below). Our inventory also uncovered that large quantities of work were found in single family residential neighborhoods, community spaces, churches, and daycares. Spotting works in these unconventional zones led us to understand that residents are activating their social and cultural spaces with creative expressions outside of the traditional public art forms.

Rosela.,

Arts & Planning Toolkit, 2022

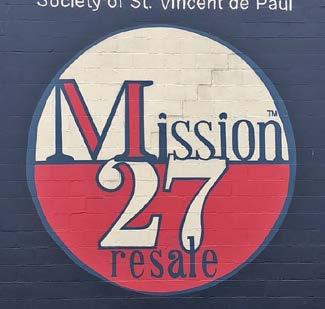

Additionally, our data showcased that many of the works found at commercial/retail sites were in the form of hand-lettered signs. This is a category not currently listed within the Indy Arts Council's Public Art Directory. However, sign painting is a historic and highly skilled professional art form. Hand-lettered signs include signage with hand-lettering, and often painted images, along with hand-lettered text that functions as commercial or wayfinding signage. The growing number of hand-lettered signs bring awareness to the many ways art is a driver for economic impact, community-building and encouraging competency within the built environment.

This inventory found 177 hand-lettered signs countywide.

Studies suggest that people walk at least 30 minutes a day, equating to a slow-paced mile. With that in mind, we measured accessibility of public art with respect to walkability, and proximity to transit, parks, greenspaces, and schools.

Walkability and transit connectivity are important metrics for measuring equity of public spaces. A walkable city is one where pedestrian transportation is convenient and safe, as measured by six dimensions of walkability: pedestrian-oriented design, dense networks of streets, trails and greenways, mixed-use environments, understandable organization around centers, direct and comfortable connections to frequent transit, and managed parking and right-of-way. According to United States Environmental Protection Agency data, the majority of Marion County has high walkability.1

High walkability

High public art density

Hyper local areas with low walkability, within high walkability + high public art density zip codes

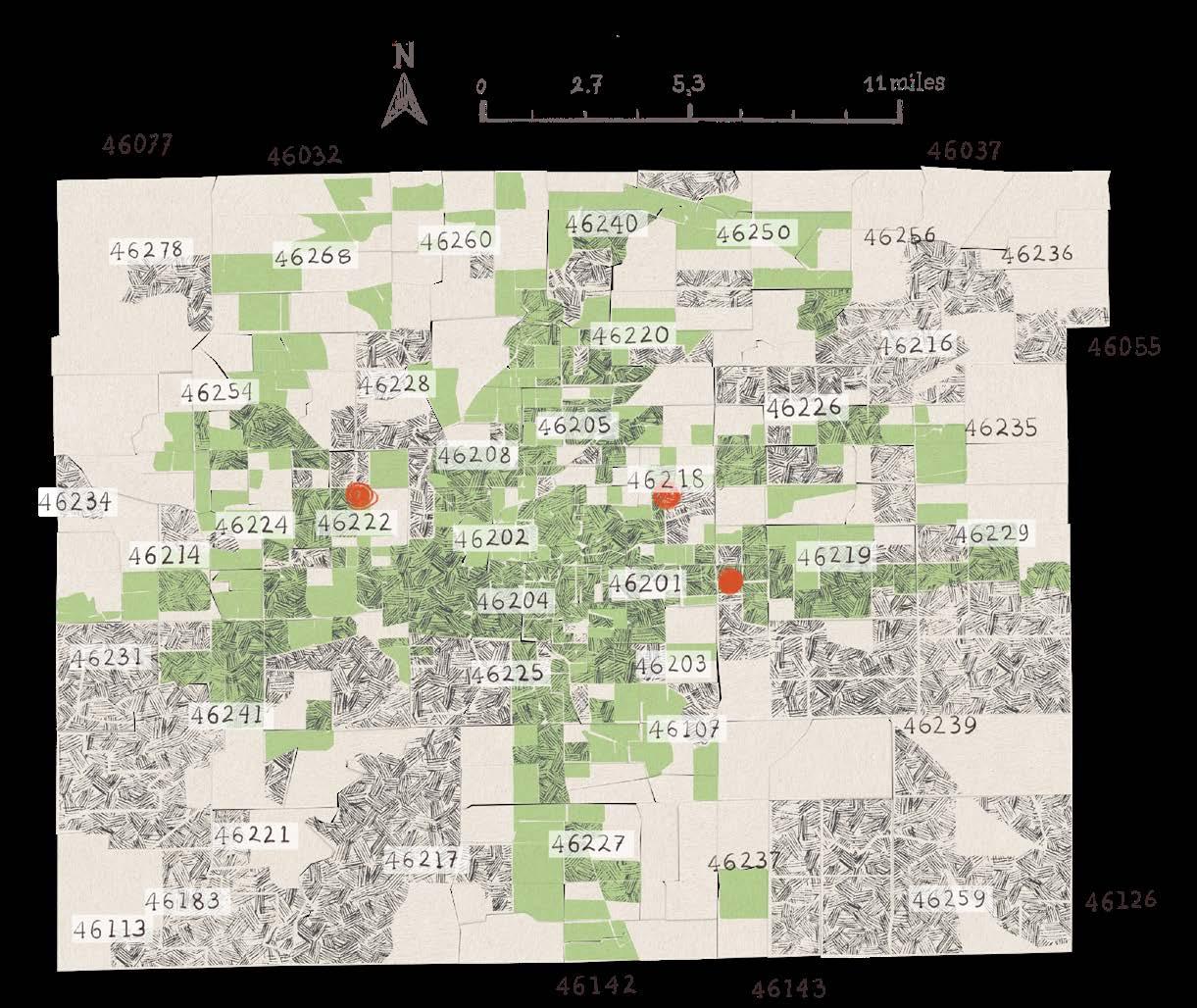

Figure 16 shows the walkability index countywide. Figure 17 details the correlation between the density of artwork and walkability. The two images show that the locations of public art deserts identified on page 42 strongly correlate with areas of low walkability. Figure 17 also shows that even within overall highly walkable areas, there may be still be zones experiencing less walkability to public art, as highlighted with red dots in specific areas within zip codes 46205, 46222, and 46218. Further study in these areas could identify potential opportunities to support community efforts to increase public artwork and access thereto.

1. United States Environmental Protection Agency Walkability Index, 2009

Parks are ideally democratic spaces where the community can meet to exchange values and share in celebrations. Activating parks through the use of public art can create a place that is meaningful and personal to the visitor, as well as connect the site to the broader community. Our inventory located 32% of the artworks in Marion County in public parks and greenspaces. With nearly a third of the artworks hosted in public parks and greenspaces, therein lies an opportunity for continued investment and support to uplift inclusive partnerships between parks and creatives.

Public transit contributes to a healthy community in various ways, one of which is effectively and efficiently moving people throughout a community. It can connect denizens with resources and amenities. While there is not a standard, research has found that people will walk between .25 to .5 miles to access public transportation. Within Marion County, our inventory found that 54% of the artworks found were within a 1-mile buffer to public transit lines. Having more than half of the inventory accessible along or near the local bus line indicates opportunities for residents and visitors to have access to an art-based experience as a part of their daily routine. Aesthetic enhancements at or near stations and facilities could be an integral component of broader community outreach and partnership building efforts.

Public artwork

996 artworks found within 150 meters of park / public greenspace

150m buffer around bus routes

Public artwork 1676 artworks found within buffer

When children engage with the arts, it positively impacts their social-emotional growth and understanding of the world around them. Our inventory found that 75% of the public art catalogued was within 1 mile of the 75 registered K-12 schools across Marion County (see Figure 20). This is a striking figure that implies school-aged children have access to visually engage with public art en route to and/or from their school sites. Our inventory also found 44 public artworks directly on school grounds. From the works seen, we consider this to be an activation by school stakeholders to enliven their campuses, and by communities centering student voices.

greenspaces, and learning sites are strong community partners for the creation of accessible public art.

1500m buffer around a K–12 school

Public artwork

2326 artworks found within buffers

Colleges and universities are also sites of public art density. Our survey revealed that 32% of public art found was within 1 mile of one of the 29 public colleges and universities in Marion County. Assuming that college and university campuses have larger footprints, the count is not quite as robust as K-12 but nevertheless, university campuses act as intermediary community resources. This implies that they, too, are sites for public art collaboration.

1500 meters is just under 1 mile

1500 m buffer around a college/university

1500 meters is just under 1 mile

Public artwork

995 artworks found within buffers

To improve livability and boost economies, we recommend the establishment of a public arts master plan that centers residents and is integral to city development and capital improvement plans.

Invest in and partner with alternative host sites for public art. Greenspaces, schools, and transit nodes can act as wonderful opportunities to build civic pride, encourage community connectivity, and improve quality of life for all.

This inventory collected and analyzed a subset of data to understand funding opportunities, barriers, and past inequities that could be affecting current realities. Reviewing financial data from three arts organizations (The Indianapolis Cultural Trail, Indy Arts Council, and Indiana War Memorials), which provided financial data for a set of 129 public artworks, we outlined a limited spatial analysis to detail the distribution of various types of investment across the County. As Figure 22 displays, areas outside of the red circle (downtown) have far fewer artworks and less investment per zip code. Refer also to Appendix Figure 1 for the average artwork funding by zip code.

Gathering of financial data exposed gaps in transparency and record-keeping. We found opportunities to establish public statements in an effort to commit to pay equity within the art ecosystem, and to the invest in public art in communities on the periphery of the County.

(in order of funding, the data set sourced more variables for installations than monuments)

KEY POINT Murals are more prevalent countywide; however, they receive the least financial investment based on this data set.

There was a far greater body of public art across the County than the Indy Arts Council Public Art Directory showcased. 3,090 works were found of various types and across various topologies. However, the PAD only listed 616 within Marion County. This indicates a few critical gaps. The first suggests that only certain types of artwork were considered valid public art, and second, that artwork countywide was not adequately recognized or catalogued.

landscape in real time. In doing so, broadening the definition of public art, monuments and memorials will make room for a diversity of creations to be observed and acknowledged.

Invest in murals, muralists, and mural mentorship programs, as mural programs may be more manageable entry points for resident engagement, site activation, placekeeping, and overall community building. We also recommend recognizing and investing in other artistic skillsets to encourage more variety within the public art landscape.

While murals were the most prevalent form of public art countywide (especially within residential and K–12 school zones), murals also received the least amount of financial investment on average and by individual commission. Less frequently created, but more lucrative, types of public art such as memorials, installations, and sculptures typically require training that may not be afforded to all — in particular to women and people of the global majority. Creating a mural is regularly seen as an activation that can be done collaboratively with the community and with the guidance of a tenured muralist.

C O N C L U S I O N S & R E C O M M E N DAT

Schools, daycares, and religious spaces have acted as sites for public art interventions, providing public art to areas that are otherwise public art deserts. Nevertheless, in areas where commissioned public art may be less likely to appear, communities

Generate cross-county partnerships that 1) encourage the sharing of work, 2) assist artists and arts organizations with data management, and 3) offer support for any artist seeking to catalogue their work on-site and within a comprehensive database. We also recommend the establishment of a permanent and expansive process and team with the capacity to document new works in real time.

Arts organizations seeking to support their community members could look to partner with K-12 schools, daycares, and religious institutions as these may be trusted sites that local residents are more inclined to visit and seek support.

83% of the works found did not have an identifying sign or signature on site. This creates a barrier in acknowledging the changes taking place across the public landscape. This lack of information begets a lack of transparency within the data relating to equity and inclusion, spanning from representation to funding.

Our report identified 73 historical markers, 10 major monuments, 11 minor memorial statues, and 66 roadside memorials. While Indianapolis-Marion County is known to devote more acreage to monuments than any other city in the United States besides Washington, D.C., the state of Indiana does not recognize roadside memorials as a valid form of memorialization. With the quantity of roadside memorials outnumbering the County's major and minor monuments/ memorials, and approaching the number of historical markers, this begins to highlight another manner in which residents are making space to creatively express their desires within the built environment.

Redefine "memorial" to include the agency expressed by residents who seek to commemorate their fallen loved ones and adjust policies to accommodate them safely. We also recommend hosting public meetings to gain a better understanding of the role roadside memorials play within the community and how policy can be structured to support their existence.

During our inventory we found that the average condition of public artwork across the county was "good." This ranking should not mislead. A ranking of "good" means that 11–20% of the piece in question is deteriorating or damaged. If left untreated, these artworks will worsen, attracting negative attention, becoming an eyesore or potentially causing harm to the surrounding area.

C O N C L U S I O N S & R E C O M M E N DAT I O N S

Due to the incongruent data sets, this inventory required a robust amount of archival research and cross referencing. We want to acknowledge that race, ethnicity, and gender are not prescriptive characteristics. Unless evident within the data, this report did not assume or attribute identity onto the artists, artworks, or their host communities.

Recommendation 8

Establish mentorship programs that support the capacity-building of emerging artists and creatives who have been traditionally underengaged: women and people of the global majority. Form County-based equity standards and require that artworks supported by public funding meet these standards. Partner across the County with more socially engaged local groups and institutions to elicit a wider variety of participation.

Recommendation 7

Implement in-take processes that allows the creator to self-identify the characteristics of their lived experience that are important to their creative life. County with more socially engaged local groups and institutions to elicit a wider variety of participation.

18 artists make up 35% of the authored works. Of those 18, four are Latino/a/e, 5 are Women and 1 is Black. These 18 artists each created 5 or more works across the County, some upwards of 43 individual works. This saturation by a small number of artists is harmful and antithetical to creating a public art landscape that is welcoming to all.

Collectively, the zip codes that make up the downtown region (46202, 46203, 46204, and 46225) have a total population of 67,729, making it the County’s most populous region. However, the most populous single zip code is further south (46227), with a population of 57,086. Yet, this area falls within the definition of a public art desert. There are many other communities seeking public art, and residents are proving that they will produce it however and whenever they can. The sheer number of artworks downtown could be termed a public art swamp — where the public art is too concentrated, incoherent, incongruent with the demographics of the local residents, and unadaptive with the constant physical changes that are happening in the city center.

Artworks in the downtown zip codes: 1,241

Artworks in 46227: 57

Decentralize funding from the downtown area while seeking opportunities to disseminate resources to areas with little to no public art engagement.

46201 $ 7,000

46202 $49,324

46203 $39,534

46204 $170,038

46205 $1,000

46208 $ 5,300

46219 $ 6,500

46220 $ 25,192

46222 $14,667

46224 $14,000

46225 $95,687

46226 $20,000

46227 $10,000

46229 $10,000

46240 $ 50,000

46241 $ 50,000

46254 $ 5,000

46256 $10,000

46268 $12,000 46278 $10,000

Notes: Funding data was not available for all zip codes. The average funding is not aggregated by art type.

Fig. 5

Percentage of Women & Artwork Density by census tract, zip codes overlaid for ease of orientation

High % of women

High public art density

Insufficient data

Fig. 6

Percentage of Renters & Artwork Density by census tract, zip codes overlaid for ease of orientation

High % of renters

High public art density

Insufficient data

Fig. 7

Percentage of Homeowners & Artwork Density by census tract, zip codes overlaid for ease of orientation

High % of homeowners

High public art density

Insufficient data

Fig. 8

Walkability & Average Artwork Condition by census tract, zip codes overlaid for ease of orientation

High walkability

High public art condition

Insufficient data

T H E T E A M

Author & Lead Researcher

Danicia Monét Malone

GIS Specialists

Thomas McKeon

Monica Pagán

Data Lighthouse Consulting, LLC

Scouters

Brooke Foyer

Sarah Fox

Jake Warner

Cleopatrah Smith

Special Thanks to

Dana Radford

Ajarea Underwood

Sylvia Rivers

Lobyn Hamilton

Marisol Gouveia

Desiree Gouveia

Manón Voice

Cane

Jordan Edwards

Nasreen Khan

Paige Vlietstra

Shade Bell

Fact Checking Intern

Elizabeth Cleary

Copy Editor

Kavita Mahoney

Julia Muney Moore

Graphic Designer

Rachel Leigh

Supported by

The Indy Arts Council

Art Strategies, LLC

The City Of Indianapolis

The Central Indiana Community Foundation

The Herbert Simon Family Foundation

Rokh is a multidisciplinary, cultural equity, research & design studio.

Founded in 2016, our work encompasses identity, communications, and critical spatial activation. Our partners are scholars, researchers, creatives, and practitioners who work collaboratively and independently towards rooting tactical and somatic equity & liberation in the civic sphere.

All images used are the property of Rokh.

rokh.co | info@rokh.co