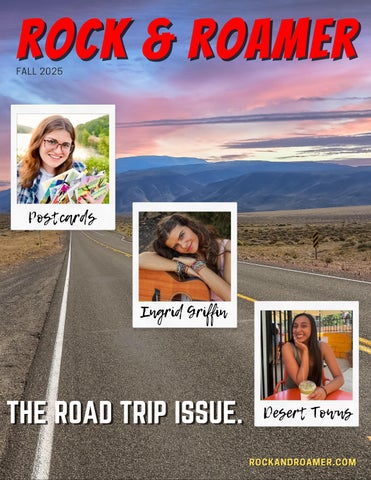

Rock & Roamer caters to good music, both mainstream and indie, finds you the most interesting places to travel, and the food to get you there.

Shapeshifting on a Saturday Night

Avery Cochrane

So American Olivia Rodrigo

Going to California Led Zeppelin

Truckin’ Grateful Dead

Please Mr. Postman

The Marvelettes

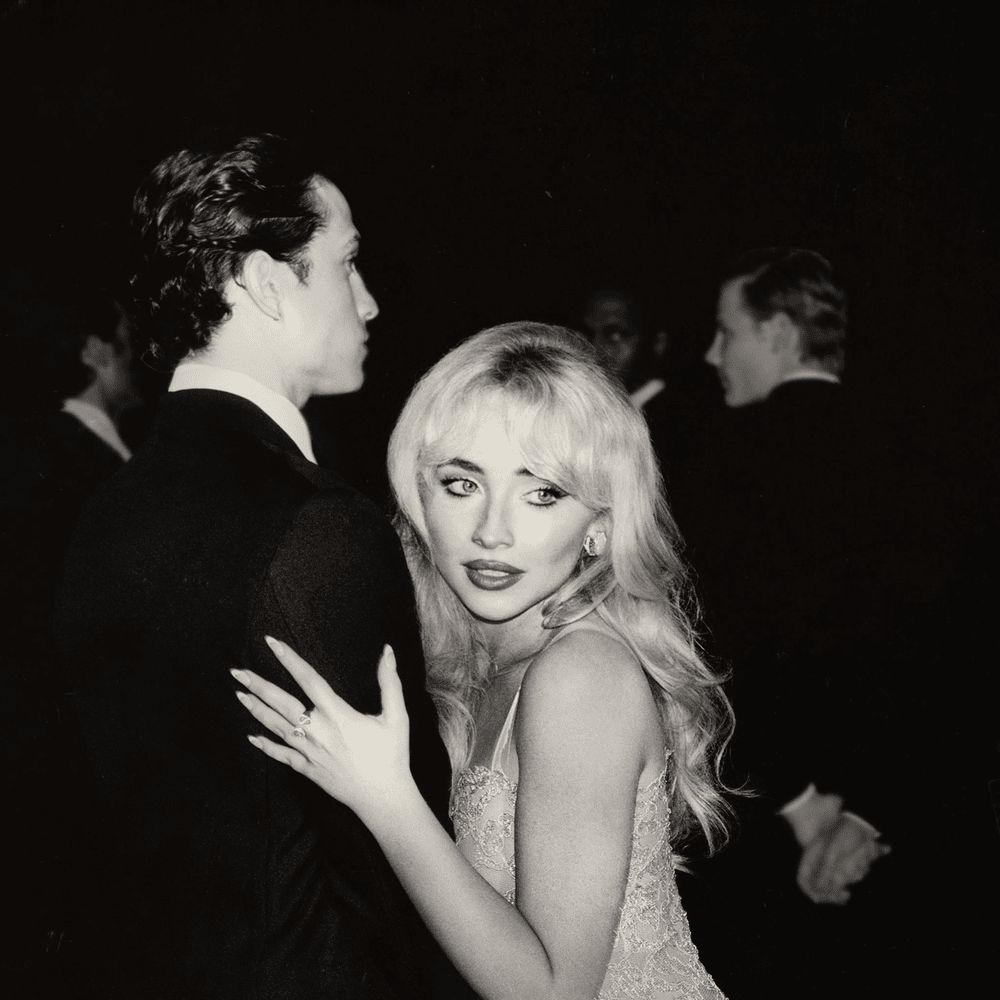

When Did You Get Hot? Sabrina Carpenter

Take It Easy

Eagles

So High School

Taylor Swift

Every road trip starts with big main-character energy: windows down, hair flying, snacks carefully curated. But the truth is, the magic usually happens when things go sideways: the detour eats up an hour, your photo op in front of a random wall is super weird, and a gas-station bracelet becomes a lifelong souvenir.

This issue of Rock & Roamer is our love letter to that chaos. We’ve got playlists for when your GPS betrays you, articles on postcards picked up between pit stops, and Ingrid Griffin’s sweep from Nebraska plains to Nashville honky-tonks. Taylor Swift steps in like the big sister who always has heartbreak advice before you even know you need it, and Sabrina Carpenter shows us how wit and vulnerability can ride shotgun together. The Grateful Dead keep proving that sixty years in, community is the real headline act, while the Inland Empire gets the radio-love ballad it deserves.

Think of this issue as part diary, part mix-tape, part messy scrapbook of the road. It’s meant to ride in your tote bag, get coffee stains, and make you want to take the long way home just to hear one more song. So buckle up, cue up the playlist, and let’s go.

LAUREN ELIZABETH CAMPBELL

Editor-in-Chief

Oliver

(Here’s Your Song)

Ingrid Griffin

Inland Empire

Ben Harper

Ripple Grateful Dead

Harvest Moon

Neil Young

Wild Thing

The Troggs

If You’re Too Shy

(Let Me Know) The 1975

While quickly moving state-to-state, I realized how easy picking up postcards on the road is.

A playlist for when Google Maps betrays you.

You could drive the same highway again, or catch the same band in another city, but it would not feel the same.

Taylor Swift was my close personal friend who somehow had the exact right advice for every heartbreak I hadn’t even had yet.

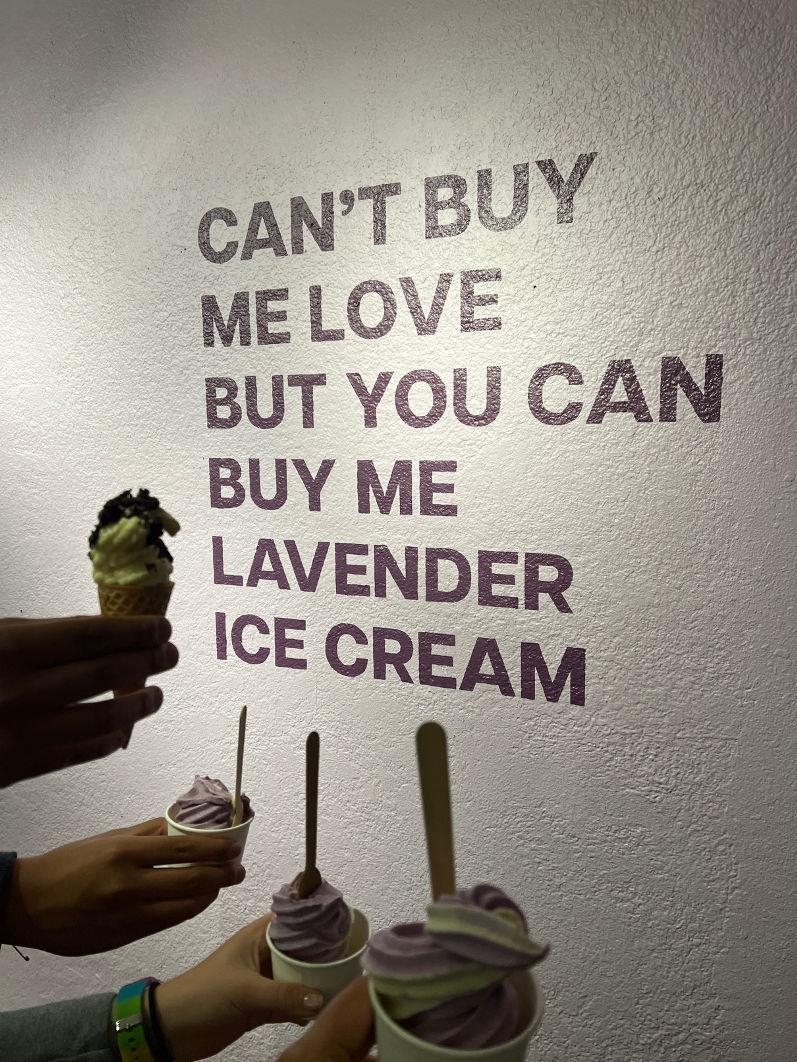

We will shamelessly spend twenty minutes in front of some random wall to get the shot.

From the wide-open plains of Nebraska to the canyon sounds of Los Angeles and the honky-tonk stages of Nashville.

The Grateful Dead isn’t just a band, but a living community.

Sabrina Carpenter has always had a way of pairing her razor-sharp wit with a kind of fearless vulnerability.

One of the best ways to feel the I.E. is just to let the radio guide you.

By Lauren Elizabeth Campbell Editor-in-Chief

I didn’t mean to have a road-trip summer. It just… happened. I wasn’t out to “find myself” or check off bucket-list landmarks. I didn’t even have a plan. I actually told myself, and everyone else, I wanted a lowkey summer. But nothing in my life stays low-key for long. One minute I was in Washington, D.C., speaking at a conference, and the next I was knee-deep in a monthslong game of domestic hopscotch across the country. It grew on its own, wild, looping, impossible to replicate. And along the way, I started mailing myself the proof.

The first trip was the seed of it all. During the conference, I wandered into the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, the kind of place you go not expecting a personal revelation. But there it was: a table of free postcards to write to yourself and have it delivered home.

A lightbulb went off. I travel a lot, and the sheer volume means I forget where I’ve been, when I went, what I did. The last couple of years, my mom has urged me to start a travel journal to remember. Keeping a travel journal always sounded romantic in theory, but in practice? A nuisance. I’ve never been a tote bag person, I like both hands free, and the thought of lugging around a notebook and actually sitting down to write in it? Not going to happen.

Postcards, though? Tiny. Manageable. No baggage. I could jot a few lines, drop it in a mailbox, and never think about it again until it magically appeared at home, a souvenir that also doubled as a gift to my future self. That first one from D.C. felt like a little experiment, but by the end of the summer, it had become the whole point.

After D.C., I ended up in Nashville for CMA Fest, which felt like stepping into a week-long street party where every block had its own soundtrack. My Nashville postcards were written in the gaps, on a curb waiting for a show to start, leaning

against a railing side-stage watching the river. One was just a sweaty, bullet-point list of everything I’d eaten that day, plus a stick figure in a cowboy hat.

Then came an unexpected big trip: West Virginia to Las Vegas in my brother’s car. He was moving there, and I had the time. From gas stations to curated town shops, I picked up postcards. And on a trip I was quickly moving state-to-state, I realized how easy picking up postcards on the road is.

Before postcards, I’d tried making my love of photo booths into a travel tradition, but the reality never matched the vision. Chasing down analog booths is a rewarding but often disappointing hobby, if you can even find one, they are often out of service, and digital booths can be wildly hit or miss…

assuming a town even has one at all. And while I still do the photo booth chase, postcards allow for a more consistent, travel journal feel.

Kentucky’s postcard was written in a parking lot during a thunderstorm describing what it was like being back in my old college town. Tennessee’s was written in Elvis’ Graceland. In Arkansas, I wrote one at the top of a grist mill watching a turtle swim.

Oklahoma was my favorite part of the drive. I drew on a postcard the most skystretching, scary beautiful lightening I had ever seen through Tornado Alley. And in Oklahoma City, I wrote about my surprise for how much I wanted to move there.

Texas got a postcard at Cadillac Ranch, and I wrote several in Santa Fe, New Mexico

describing the priceless works of art I was viewing and the sky, which felt too big for the Earth. Arizona’s was literally about standing on the corner in Winslow. And then finally, Vegas’ was about the joy of being able to sleep in the same bed for multiple nights.

From there, I hopped to Los Angeles, where my first postcard was a rant about traffic on the 405 which turned into an accidental love letter to a city that still feels like home. From L.A. to Chicago, where I wrote a letter to my younger self, sitting on a stage at The Second City where I used to perform improv as a teen. Then to Berkeley Springs, West Virginia, where I wrote about the way the air smelled like minerals and how everyone waves at each other from across the street.

I flew back to California for the Grateful Dead’s 60th anniversary shows at Golden Gate Park. That postcard was half setlist, half overheard crowd quotes. “He’s not lost, he’s just somewhere else right now” earned its own underline. On another postcard, I picked up from Amoeba Music, I just drew a flower given to me by a hippie.

I wrapped the summer in my home state, West Virginia’s New River Gorge National Park, where my postcard was a few lines about the sound of water over rocks, and Lewisburg for the 100th annual state fair, that postcard may or may not still smell faintly like a farm, in the best way.

By the end of the summer, I’d mailed myself over a hundred postcards. They started showing up in uneven waves, some weeks, three or four; other weeks, just one,

battered and beautiful from the road. Many, not even in the order I’d mailed them. I’d read them like I hadn’t written them, because in a way, I hadn’t. They belonged to the version of me who was drinking a Shirley Temple at the Chateau Marmont lobby bar, or trying to keep a postcard from blowing away in Oklahoma.

I never planned to spend the summer on the road. I never planned to send over a hundred postcards to myself. But now they’re stacked in a shoebox, my whole summer, postmarked and permanent, proof that the best trips are the ones you don’t see coming, and the best souvenirs are the ones you mail home before you even realize what they mean.

Truckin’ Grateful Dead

Already Gone

Eagles

Keep the Car

Arcade Fire

Running

Part Of The Band

The 1975 By and By

Caamp

Go Your Own Way

Fleetwood Mac

She Calls Me Back

Noah Kahan

Long Way From Home

The Lumineers drivers license

Olivia Rodrigo

Best Day Of My Life

American Authors

Playlist by Lauren Elizabeth Campbell

ROCK

Saturday Sun

Vance Joy

Mrs. Robinson

Simon & Garfunkel

Ramblin’ Man

Allman Brothers Band

Joshua Tree

Rozzi

Keep Driving

Harry Styles

On The Way Home

John Mayer

Graceland

Paul Simon

I Wish You Would

Taylor Swift

Born to Run

Bruce Springsteen

Fast Car

Tracy Chapman

By Sebastian Potter Staff Writer

There is a moment, about an hour into any road trip, when the rhythm settles in. The car, once a static object, has become an instrument: the hum of the tires a bassline, the rattling dashboard a percussion section, the voices inside: singing, arguing, drifting into silence, layered like vocals. A highway is no mere route. It is a stage, long and narrow, stretching endlessly forward, and a road trip is nothing less than a performance.

Concerts and road trips share a secret: they are remembered less for their precision than for their imperfection. A flubbed lyric, a broken string, a stretch of road construction that reroutes the entire day, these interruptions become the highlights. The magic lies in the fact that the performance cannot be repeated. You could drive the same highway again, or catch the same band in another city, but it would not feel the same. Time, weather, company, mood— these are the stagehands, constantly reshuffling the scene.

Playlists are setlists, and they must be crafted with care, or at least with a sense of drama. The first song must announce: the show has begun. Somewhere in the middle, deep cuts emerge, the songs you didn’t know you needed until they arrive, perfectly timed with a sun-drenched valley or a sudden burst of rain. And inevitably, there’s a closer, the one that sees you through the final stretch, headlights sweeping forward like spotlights on the last chorus.

Even detours resemble encores. You thought the show was finished; the road was straight, the end was near. Then, an unexpected turn, a missed exit, a scenic byway flashing its invitation, and suddenly the performance extends. It is unplanned, unnecessary, yet unforgettable. Years later, you won’t remember the mileage, but you’ll remember the winding road that offered one last song.

What makes both concerts and road trips linger in memory is not efficiency but immersion. Miles, like measures, pass in sequence, yet meaning comes from the layering: the harmonies of voices drifting in and out of conversation, the crescendos of

laughter, the pauses of silence when everyone stares at the horizon. Each trip, like each performance, is communal, dependent not just on the main act (the road, the band), but on the crowd. The passenger who keeps watch for shooting stars, the driver who insists on one more song, even the landscape itself, all of them performers, all of them part of the ensemble. And when it ends, as it must, there is that

same ache as when the house lights rise after a final bow: the recognition that something rare has just happened, and will never happen in quite the same way again. Perhaps that is why we return, again and again, to highways and to concert halls, not for repetition, but for reinvention. The chance that this time, in this car, on this road, with this company, the performance might be transcendent.

by

By Lauren Elizabeth Campbell Editor-in-Chief

When I saw Taylor Swift was engaged, I could’t help but remember 10-year-old me, twirling around in my bedroom after the Fearless Tour, imagining that Taylor Swift was my close personal friend who somehow had the exact right advice for every heartbreak I hadn’t even had yet.

The kind of friend who would say, “Yes, you should wear sparkly eyeshadow,” and also, “No, you should not text that boy back.” The kind of friend who told me, before I had even kissed anyone, that sometimes it was better to be “Fearless” than to be polite, and sometimes the bravest thing you can do is be honest.

Back then, I thought love was going to look like a sparkly purple dress and a boy who would never leave me crying on the staircase. Over the years, I’ve learned it looks a lot messier. There have been the highs, the dizzying “Enchanted” moments, and the lows, the “you look like bad news, I gotta have you” chapters. I’ve been both terrified and revolted by love, and I’ve been “The Bolter” when I needed to be “Fearless.” But through all of it, I had Taylor, this everpresent chorus line reminding me to stay hopeful, to stay open, and to keep dancing even when my heels break.

Taylor Swift getting engaged is not just a headline. It’s an entire reframe of my own timeline. Because if Taylor has been my North Star of heartbreak, resilience, and romantic imagination for the past 16 years, then her saying “yes” to someone feels like a note from the universe: See? Love can happen. Even after everything. Even after writing “All Too Well (10 Minute Version).”

I have been many versions of myself in love: the dreamer, the realist, the girl who waited by the phone, and the girl who deleted his number with Olympic-level efficiency. But perhaps the most persistent persona is “The Bolter.”

You know, the girl who panics at the thought of someone liking her too much, makes an escape plan faster than you can say “1, 2, 3, Let’s go, bitch,” and leaves the ROCK &

party early without saying goodbye. But Taylor gave me permission to want more. She made being open-hearted seem like a strength, not a liability. And even when I failed at it, when I was scared or cynical or deeply unimpressed by a boy who probably doesn’t even remember my name, I never quite stopped believing.

It feels like Taylor just turned a page in the giant, communal diary she’s been writing with all of us since “Tim McGraw.” And now, I get to believe that the best chapters for me haven’t been written yet either.

I can measure my entire coming-of-age in Taylor Swift albums. Taylor Swift: the electricity of realizing that maybe my fairytale won’t start with a stranger. Fearless: being so sure that the world would end if a boy didn’t like me back. Red: scarf-level regret. 1989: falling in love with a city instead of a boy. Reputation: understanding

that sometimes you have to burn it all down and start over again. Lover: being open is its own kind of strength. Folklore and Evermore: falling in love with the quiet parts of myself. Midnights: realizing that being awake at 2 a.m. sometimes just means you’re alive enough to feel things.

So what does Taylor Swift getting engaged really mean? It means that love is still possible, even after heartbreak so devastating you turn it into a stadium tour. It means that every single time I’ve loved, the wrong people, the right people, the friends, the places, the seasons, it wasn’t wasted. It means that hope is not naïve, that romance is not extinct, and that the ten-year-old dancing alone in her bedroom was onto something.

And if Taylor Swift still believes in love enough to keep choosing it, so can I.

By Lauren Elizabeth Campbell Editor-in-Chief

OK, I’ll be the first to admit it: I am a photo snob. My best friend knows this (she’s guilty too—we’re basically enablers). We will shamelessly spend twenty minutes in front of some random wall, tilting our heads like confused pigeons, adjusting our stance by millimeters, until one of us finally yells, “Yes! That’s the shot.” But listen, this isn’t about Instagram. This isn’t about thirst traps or fake-casual latte photos. This is about artistic integrity. About capturing lightning in a bottle. About holding a piece of time in your hand before it slips away.

Photography, for me, has always been a way of catching something fleeting, the exact shade of a Venice sunset, the way a laugh bounces off a cobblestoned street, the proof that I was here, before memory sands it down. Sometimes that means sculpting the perfect composition; other times it’s about surrendering, letting the bad lighting, the wind-tangled hair, the blurry joy tell the truth. I’ve learned it’s both.

My first encounter with real film was with disposable cameras. Clunky, plastic, and gloriously unreliable. There is no editing, no retakes, just the delicious suspense of waiting to see what you’d actually captured. Sometimes I even soak the film in flower petals or dye, chasing unpredictable effects, tiny experiments with fate. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t, but it always feels like magic. Disposable cameras taught me patience, the kind you don’t get in a world of instant previews. They also taught me boundaries. Because let’s be honest: they’re perfect for road trips, house parties, and nights you only half remember, when the blur becomes part of the story. But as a tool for serious travel photography? That’s another story. Do you really want your only souvenir of the Louvre to be a grainy, redeyed, off-center disaster? Editorially speaking, that’s a crime against humanity. And then of course, there’s the iPhone. Always there, always competent, and every year Apple insists it’s basically a DSLR in your pocket. Adorable. Don’t get me wrong,

I love my phone, it’s saved me more times than I can count. It’s perfect for snapping the name of a BBQ joint in Kansas or catching a skyline from the plane window, for proving to your mom you’re still alive in Texas. But the iPhone photo has a look, and you can spot it a mile away. To me, it’s the friend who will pick you up from the airport at 4 a.m. Loyal. Essential. But not the one who steals the show at dinner.

My real travel companion is my Leica. If cameras were people, Leica would be that devastatingly cool one who looks amazing even in fluorescent lighting and doesn’t even try. The film Leicas are legendary, nothing compares, but I don’t exactly have a darkroom tucked away in my apartment. My digital Leica, though, is my ride-or-die. It syncs to my phone in minutes, photographs like constellations in the dark, and delivers shots that make me stop scrolling and think, “Wow. I was really there.” It doesn’t just capture pixels; it captures atmosphere, texture, the shadow that tells the story behind the subject. Traveling with my Leica feels like traveling with a second set of eyes, ones that never miss the poetry in the scene.

Still, I chase other formats too. When I’m

traveling, I hunt down photo booths the way foodies chase Michelin stars. The real ones, the analog ones, the kind that spit out strips smelling of chemicals, where the lighting is unpredictable and the countdown is always faster than you expect. I’ve detoured whole afternoons in foreign cities just to find one, cramming in with friends or alone, fumbling for coins, then walking away clutching a strip of imperfect, glorious chaos. A photo booth doesn’t care about your angles or your hair. What you get is raw and beautiful. They’re impractical. But they’re irreplaceable, because they remind me that travel is supposed to be messy too.

Somewhere between the polished Leica and the unpredictable booth lies the Polaroid, which I think of as the flirty middle ground. Polaroids are fast, tangible, and still real film, you get the film without the heartbreak of waiting weeks. At my University of Southern California graduation, I carried both a Leica and a Polaroid. That day I didn’t mind the dual cameras. The Polaroids caught the unedited chaos: friends spilling champagne, and the California wind turning my hair into a personality of its own. The Leica gave me the glossy, professional shots. Between the two, I walked away with

both the magazine spread and the diary entry. That’s the beauty of Polaroids: they belong taped to your fridge or tucked into your journal, but scan them and they live anywhere. They bridge the gap between instant gratification and permanence.

Here’s the truth: when you travel, memories are slippery. The meals blur. The street names vanish. The people you meet become a hazy composite of accents and smiles. You remember the feeling, but the details fade like chalk in the rain. Photos

anchor it all. The staged influencer shots give you the idealistic, perfectly crafted and posed moment, and everything else helps you reconstruct the story when your brain edits out the texture.

That’s why I travel, at least for me, comes with a mix of photography. The Leica shot belongs on your wall. The Polaroid belongs in your journal. The disposable waits for you a month later with a crooked grin you forgot about. The iPhone snap reminds you of the name of that café in upstate New York when

someone asks for a recommendation. And the photo booth strip? That one gets tucked into your passport or your wallet, rediscovered months later like a secret love note from the trip itself. Each format fills a gap the others can’t.

Travel isn’t one-size-fits-all, and neither is photography. So yes, I’m a photo snob. But only because I believe this: if a moment is worth living, it’s worth capturing right.

Interview By Lauren Elizabeth Campbell Editor-in-Chief

Ingrid Griffin has taken quite a journey from the wide-open plains of Nebraska to the canyon sounds of Los Angeles and the honky-tonk stages of Nashville. Her roots are grounded in small-town traditions: linedancing on Sundays, busking with her dad at the farmers market, and finding inspiration in the flat farmland she still insists rivals any mountain view. But Griffin’s artistry has been shaped as much by her hometown support as by the culture shocks of L.A. and the crash course of Nashville’s Broadway scene. With a style she describes as “1970s troubadour spirit with country/pop sparkle,” Griffin shamelessly pours her stories into her songs, balancing vulnerability with fearless honesty, and always keeping performance at the heart of it all.

You grew up in Nebraska, which is known for its wide-open spaces. Do you think the landscape or the pace of life there has influenced your songwriting style?

Absolutely! My hometown had Sunday night line-dancing with live country bands, which is where I first fell in love with country music. Another special place was our farmers market, where I busked with my dad, who still plays percussion with me, every Saturday, rain or shine. People were so supportive, and it really encouraged me to keep pursuing music. And honestly, I think the Midwest is more beautiful than mountains or oceans, some of my best song ideas have come while driving through the flat Nebraska farmland.

Moving from Lincoln to L.A. must have felt like culture shock, and now Nashville is a third chapter. How do you think each city has left a fingerprint on your artistry?

Los Angeles was an exciting chapter of my life, but it was definitely a culture shock, I even wrote a song called “Red Cup” about my very first L.A. party and feeling totally out of place. Nashville, on the other hand, has felt like home from day one. Both cities have such rich musical histories, and being immersed in them has shaped me in completely different but equally important ways.

What’s the difference like as an artist between playing venues in L.A. like Hotel Café and working the Broadway scene in Nashville?

I was a college student at University of Southern California. when I lived in L.A., and I was the only country artist I knew, so that was the biggest difference as far as L.A. is concerned. Broadway in Nashville is its own world! The sets are four hours long, based mostly on requests, there are no set lists. Sometimes I show up to a full-band gig without even knowing the musicians I’ll be playing with! It keeps you on your toes in the best way. Plus, it has forced me to learn hundreds of country and rock classics, which has been an amazing crash course in great songwriting.

Your album is called It’s All Just Songwriting Material. Is there a story you thought you’d never share in a song but eventually did?

I shamelessly spill secrets, reveal vulnerable truths, and name-drop in my songs. Nothing is off-limits! My song “Throwing Pebbles” is about a grand, romantic gesture to win someone back. It was a story I once thought I’d keep to myself, but writing it into a song helped me share it in a way that feels universal. And if you come to one of my gigs, you might find out the real-life twist to that story. You’ve marketed your music with bracelets, fortune cookies, and lyric-covered notebooks. How do you balance marketing and creating your music?

Though music marketing can be daunting, I like to think of it as part of the creation process. My mom is my secret weapon, she

has made thousands of bracelets for me over the years. It’s a fun way to get my songs into people’s hands, literally. If your younger self could see you now, what do you think she’d be most surprised by?

Growing up, I loved theater and dreamed of landing a lead in a Broadway musical in N.Y.C. Turns out, I did make it to Broadway, just the one in Nashville! My younger self would probably be surprised that I chose music over acting, but either way, I’ve always loved performing, and always will. You’ve said you want to be a role model for young women in music. What’s the best piece of advice you wish someone had given you at the start of your career?

There’s a speech by Teddy Roosevelt called “The Man In The Arena,” it basically says that “even if you fail, you’re braver than

anyone who never tried.” I wish I’d heard that earlier in my career. It’s a reminder to not let failure or judgement hold you back. As you dig deeper into the Nashville music scene, how do you see yourself blending your Laurel Canyon influences with Nashville’s evolving sound?

I like to describe my music as “1970s troubadour spirit with country/pop sparkle.” L.A. solidified my love for Laurel Canyon legends like The Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, and Joni Mitchell. Now, Nashville has sharpened my lyricism and storytelling. My producer, Ben Kirsch, does a great job at incorporating instrumentation and production styles that reflect The Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, and my other Laurel Canyon faves.

You can stream Ingrid Griffin’s music on Spotify and follow her journey on Instagram and TikTok @ingrid.griffinnn.

Photo By Susie Gessert

By Lauren Elizabeth Campbell Editor-in-Chief

Ten years ago, I started listening to the Grateful Dead because my guitar hero joined their band... John Mayer. It felt like musical worlds colliding: the guy who once sang “Your Body Is a Wonderland” standing shoulder to shoulder with Bob Weir, the cowboy-philosopher guiding the Dead into yet another era. Dead & Company, they called it. And while purists groaned, I was hooked. Mayer’s entrance gave me, and entire generations who had missed the Dead the first time around, an excuse to tumble headfirst onto the bus: endless jams, cosmic lyrics, and, yes, tie-dye.

But what exactly is the Grateful Dead? On paper, they’re a San Francisco rock band born in 1965, but in practice they became something far stranger: part jug band, part psychedelic orchestra, part American folk revival, and part traveling improvisational laboratory. They never settled on one sound or even one identity, blues one night, spacey jazz the next, then a country ballad that somehow lasted twenty minutes. That flexibility wasn’t just an aesthetic choice; it’s the reason they’ve endured. When one member left, when styles shifted, when tragedy struck, the music bent but it didn’t break. The Dead survived because they were never only one thing, and in being everything, they became timeless.

Rewind to 1965: a scruffy Bay Area bar band called The Warlocks renamed themselves the Grateful Dead and plugged into the counterculture. Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Phil Lesh, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, and Bill Kreutzmann began stretching rock and folk standards into psychedelic odysseys. Soon Mickey Hart joined, bringing the drummers’ duel that became a Dead signature. Over sixty years, members rotated in and out: Brent Mydland, Keith and Donna Godchaux, Vince Welnick, Bruce Hornsby, but the ethos remained: no setlist the same, no show without risk.

Some members left, some passed on, but the music kept morphing with whoever was there to play it. The music has been carried under banners like The Other Ones, The Dead, and most famously, Dead & Company.

The Grateful Dead isn’t just a band, but a living community. Their concerts became experiments in freedom. Fans taped the shows (with permission!), traded them like baseball cards, and built one of the most decentralized archives in music history. The culture of sharing helped invent the idea of open-source before Silicon Valley had a name for it.

They created an ecosystem that everyone wants to be apart of, which is why the Grateful Dead is one of the most imitated bands in the world, and yet they’re impossible to truly imitate. Try, and you inevitably end up doing your own thing. Just ask Phish. Or Dave Matthews Band. Or Billy Strings. Or Goose. Each of these artists is indebted to the Dead’s trailblazing improvisational spirit, but none of them are the Dead. Because there’s only one Grateful Dead.

If you’ve ever seen Phish noodle their way into a 25-minute jam, or Dave Matthews spin “Two Step” into a marathon encore, or

Billy Strings blend bluegrass with psychedelic fury, you’ve seen the Dead’s fingerprints. Yet those artists are also reminders of the Dead’s uniqueness: no one else has quite captured that precarious balance between chaos and transcendence. The Dead weren’t trying to sound perfect. They were trying to find magic in the moment. And somehow, sixty years on, they still are.

This summer, I traveled to San Francisco for the 60th anniversary shows at Golden Gate Park. Talk about full circle. In the late 1960s, they played free shows there that felt less like concerts and more like public experiments in how music could rewire a community. The park was their open-air laboratory: kids barefoot in the grass, the Hells Angels providing dubious “security,” and the Dead cranking their amps into the foggy San Francisco sky. Those shows weren’t just entertainment, they were civic events, shaping the cultural mythology of the Haight-Ashbury.

Then came November 3, 1991: the last time the Grateful Dead played Golden Gate Park with Jerry Garcia. By then, the band was a global phenomenon, but that day still felt like a hometown gathering. Tens of thousands filled the Polo Fields for a free memorial concert honoring promoter Bill Graham, who had died in a helicopter crash just a week earlier. The Dead closed the day after sets from friends and collaborators, with guest appearances by John Fogerty, John Popper, and Neil Young, adding to the sense of musical community and loss.

That concert was both triumphant and elegiac, the last great Golden Gate communion with the full lineup. For Deadheads, it became a historical marker, a kind of “where were you when” moment.

So when Dead & Company rolled back into Golden Gate Park for the Grateful Dead’s 60th anniversary, ghosts were everywhere. You could feel the echoes of those early free concerts and the shadow

of that monumental 1991 show.

Standing in the grass, I kept thinking about the continuum: the barefoot kids had grown into silver-haired veterans, some had brought their own children, and still others were newcomers like me, fans pulled in by curiosity, but all of us bound by the same long strange trip.

Bob Weir looked at home, his grey beard catching the California sun like he’d been waiting six decades for this exact day. Mayer bent notes into something halfway between blues and starlight. And when the crowd swayed as one, it wasn’t just to the music happening now, it was to every memory stitched into that space.

For me, it was more than just a concert. It was pilgrimage. I used to work for Rhino Entertainment, the Dead’s label under Warner Music, handling projects that connected me to the band’s vast legacy. To stand there in Golden Gate Park, decades after the band’s birth and thirty-plus years

after their last show with Garcia, knowing, just by being there, I get to be a small part of the machinery that keeps their music alive, was meaningful. The Grateful Dead have always been about time travel: songs from the ‘60s reinvented nightly, old venues reborn in new eras, memories looping back on themselves. That day in Golden Gate Park, it felt like all of it: past, present, and future, was alive at once.

Sixty years is a long, strange trip by any measure. The Dead have survived death, legal battles, and the music industry’s shifting sands. They’ve outlived countless trends, always orbiting their own sun. Because what the Dead does isn’t replicable, it’s alchemy. You can study the scales, the rhythms, the lyrics, but you can’t reproduce the way Garcia’s guitar seemed to ask questions more than it gave answers.

There is, and will only ever be, one Grateful Dead.

Rivers and Roads

The Head And The Heart

Ribs

Lorde Vienna

Billy Joel

Matilda

Harry Styles

You’re Gonna Go Far

Noah Kahan

Wild World

Yusuf / Cat Stevens

You’re On Your Own, Kid

Taylor Swift

Everybody’s Changing

Keane Scott Street

Phoebe Bridgers

Don’t Look Back In Anger

Oasis

Sleep On The Floor

The Lumineers

Garden Song

Phoebe Bridgers

Growing Sideways

Noah Kahan

In the Aeroplane Over the Sea

Neutral Milk Hotel

Piazza, New York Catcher

Belle and Sebastian

Father And Son

Yusuf / Cat Stevens

Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right

Bob Dylan

In My Life

The Beatles

Waiting Room

Phoebe Bridgers

Daisy Duke Rooney

By Lauren Elizabeth Campbell Editor-in-Chief

I’m not here to tell you not to use AI. That’d be ridiculous… and hypocritical. I use it every day. Not leaning into it in 2025 feels like refusing to pick up a guitar after Dylan went electric. The AI revolution isn’t coming, it’s here. If you’re not experimenting with it, not even trying to understand it, you’re already a generation behind.

But here’s the catch: how you use AI matters. Done right, it can spark ideas, push you into uncharted territory, and force your brain to stretch. Done wrong, it does your thinking for you. AI can sharpen your creativity, or dull it into mush. It can make you brilliant. It can also make you stupid. And nowhere is that line more fragile than in music.

Music is not data. It’s lived experience turned into rhythm, melody, and words. AI can clean up audio, suggest chord progressions, and even inspire new sonic textures. That’s exciting, technology has always been a collaborator, from the very first guitar pedal. But when AI crosses into cloning, stealing an artist’s voice, lifting their style without permission, it stops being collaboration and starts being theft.

There’s a difference between using AI to ask more questions of your own art, and using it to erase the humanity in someone else’s. A deepfake of Drake or a Frank Sinatra cover “sung” by an algorithm may be novel, but it’s not music in the way we’ve understood music for millennia. It’s an impersonation, an echo without a heartbeat. Which brings us to the law. After decades of the music industry chasing its own tail around Napster, LimeWire, and streaming royalties, we’re now staring down a new frontier: artificial voices and digital doubles. The fight is less about piracy than about personhood.

The centerpiece is the NO FAKES Act: federal legislation introduced in 2024 that would, for the first time, give every American control over their own voice, image, and likeness in the age of AI. It says you can’t just scrape, clone, or monetize someone’s identity without consent, and it creates takedown mechanisms to help remove unauthorized replicas.

In 2024, Tennessee passed the ELVIS Act, a state law that makes unauthorized voice cloning: using AI to replicate a singer’s or speaker’s distinctive voice without their permission, illegal, with both civil and criminal penalties attached. It’s a symbolic nod to the King, but also a blueprint for protecting future voices.

And there are other measures bubbling up in Congress: the TRAIN Act would give creators the right to know if their songs were used to train AI models; the Generative AI Copyright Disclosure Act would require developers to disclose what copyrighted works they feed into their algorithms. Meanwhile, the U.S. Copyright Office has made it clear: works entirely generated by AI aren’t eligible for copyright. Human input is still the line that makes something legally art.

Harvey Mason Jr., CEO of the Recording Academy, has been vocal about the threat, calling AI both an opportunity and an existential danger. “The bill establishes in federal law that an individual has a personal property right in the use of their image and voice. That’s just common sense, and it is long overdue,” Mason Jr. stated.

The bigger issue isn’t whether machines can make music. They can. The question is whether we, as a culture, want them to, or at least, whether we’re willing to blur the boundary between authentic and artificial.

AI has always promised efficiency. But art isn’t supposed to be efficient. It’s supposed

to be messy, human, full of flaws and contradictions. Strip that away, and you risk hollowing out the very thing that makes music worth listening to in the first place. This isn’t about Luddites clutching their vinyl collections. It’s about ensuring the next Bob Dylan or Joni Mitchell or Kendrick Lamar isn’t drowned out by an algorithm spitting out Franken-songs. AI can be a collaborator. It cannot be the author. Which is why this is bigger than just industry hand-wringing. It’s political. If you care about music, whether you’re a fan or a creator, you need to care about the laws being written right now. Urge your representatives to support the NO FAKES Act. Push for the TRAIN Act. Defend the ELVIS precedent. These aren’t niche debates, they’re about whether art retains its humanity in an age of machines. Because AI will either enhance us or erase us. And in music, the choice should be clear: machines can play along. But the song still belongs to us.

The 11th annual Music Advocacy Day on September 25 continues the push for the NO FAKES Act. Organized by the Recording Academy, it’s the largest grassroots movement for music in the country. If you believe music should remain human at its core, this is your chance to join in, add your voice, and help shape the laws that will define the industry’s future by contacting your local lawmakers.

By Lauren Elizabeth Campbell Editor-in-Chief

Sabrina Carpenter has always had a way of pairing her razor-sharp wit with a kind of fearless vulnerability, but Man’s Best Friend feels like a culmination of that duality. It’s playful and biting, dreamy and devastating, often in the same verse. What makes this record remarkable is how it reads like a diary you weren’t supposed to find, but she left it out on the counter anyway, glitter pen doodles in the margins and all.

This is not just an album about love and heartbreak; it’s about the small, almost comical tragedies of modern romance, about the ways we make fun of our own pain in order to survive it. Each song is a vignette, a little Polaroid of a moment that’s both hyper-specific and universally relatable. “Manchild”

As the lead single, “Manchild” sets the tone perfectly. This song will let an innocent woman not be, it flips the script on fragility and asks what happens when you stop giving men the benefit of the doubt. Sabrina delivers it with a sly smirk, balancing pop gloss with lyrics that carry real bite. It’s not just an pop knockout, it’s a thesis statement. “Tears”

“Tears” takes us into a dreamy ABBA-style number and definitely gives us what we want and treats us like a good song is supposed to. And it adds a much-needed dance break…the neighbors who live below me probably know this best. It’s the kind of track that makes you twirl around the kitchen at 1 a.m., where happiness itself feels like it’s dissolving into glitter. And as for what kind of “tears” Sabrina’s really singing about, I’ll let you listen to hear what that’s an analogy for. The way she pulls from disco lineage feels intentional: she understands that joy, like heartbreak, has always been best processed under a mirror ball.

“My Man on Willpower”

Any girl who has ever felt a man pull back will truly understand this song. It plays out the scenario like a delusional rom-com where the girl doesn’t end up with the guy,

but in the best way. We’ve all been there, waiting for someone who’s half-invested, convincing ourselves the story will change. And this song makes it fun, poking holes in the fantasy with just enough irony to make you laugh through the sting.

“Sugar Talking”

“Sugar Talking” demands action: “put your loving where your mouth is.” It insists on more than flowers, calling out men who hide behind charm but offer nothing real. A great contrast and lesson to girls that flowers and words mean shit if actual care isn’t there. It’s sharp, it’s defiant, and it’s easily one of the most empowering moments on the record.

“We Almost Broke Up Again Last Night”

This one sounds like it could be sung by a dirty Sandy from Grease: longing, wistful, with a sing-song feel. The POV is almost self-mocking: the girl she sings about probably should break up with the guy, but the song exists, so maybe not. Sabrina leans into the contradiction of romance, the way we cling to what hurts because it still feels like love when it’s in motion.

“Nobody’s Son”

Here, the album digs deeper into the musical-type feel. “Nobody’s Son” sounds like an end-of-summer-relationship song,

the kind where the guy is just… over it. The lyric about friends in love calling her to third-wheel hits a little too close to home. It’s devastating in its understatement, the kind of track that doesn’t break you loudly, but does leave a message for the parents of corrupted boys.

“Never Getting Laid”

This one’s deliciously ironic. It has the musical vibe of the type of song I think a guy would turn on if I was guided into a bedroom in the 1970s, but with the complete opposite lyrics. Instead of seduction, she’s actually wishing the guy never gets laid. And yet, wishing him happiness too. It’s biting but benevolent, like saying: if you don’t want me, that’s completely fine, but just please stay abstinent. Thanks.

“When Did You Get Hot?”

This has got to be my favorite song off the album. It’s about finding someone from your past and getting hot and bothered by the glow-up. It makes me want to go to this socalled prospect convention, but really host it at my apartment with only one person. Or play naked Twister back at their place… I’ve said too much. It’s cheeky but also deeply human, how attraction sneaks up on you and

turns the ordinary into spectacle.

“Go Go Juice”

The fiddle in this song is what got me. It took me back to a time when I was at The Old Saloon in Emigrant, Montana, having a lot of feelings. But really, you can picture yourself drinking in any bar. Or at home. Or in a bathtub. This song gives off the vibe of drinking a beer in a bubble bath, comforting and messy, indulgent and intimate. Sabrina has a knack for grounding pop songs in sensory detail, and this is a perfect example. “Don’t Worry I’ll Make You Worry”

Song-title wise, this might be my favorite. Clever, sharp, and knowingly chaotic. It’s the kind of phrase you’d scrawl in lipstick on a bathroom mirror, equal parts confession and threat. The track itself plays with that

tension, love as both solace and sabotage.

“House Tour”

Immediate disco vibes. Immediate reckless dancing. Immediate wanting to invite a guy over. Very disco Barbie—in a world where Ken is important, but only as a side character. It’s euphoric, campy, and irresistible. Carpenter knows how to write a track that makes you want to redecorate your life in neon.

“Goodbye”

“Goodbye” closes the record with the weight of finality. It literally gives an ending to the album that feels like a story, like you’ve lived through a whirlwind of flirtations, heartbreaks, hookups, and false starts, and now you’re sitting with the silence after it all. It’s both cinematic and

intimate, the perfect curtain call. Final Thoughts

Man’s Best Friend is both tongue-in-cheek and heart-on-sleeve. It’s an album that laughs at the absurdity of romance while still taking its bruises seriously. Sabrina Carpenter delivers sharp lyrics, disco-soaked melodies, and moments of genuine confession that make you feel like you’re not just listening, you’re in on the joke, crying on the dance floor, smoking outside the bar, or sharing secrets on the fire escape at 2 a.m.

It’s an album for anyone who’s ever been left on read, danced through tears, or said “goodbye” when they didn’t mean it. And in Sabrina’s hands, it’s more than pop, it’s survival, set to a beat.

By Tiana Perez Staff Writer

There’s a stretch of freeway I know all too well. From the edges of Los Angeles through the San Bernardino pass, past windmills that spin like giant metronomes keeping time for the desert. For most people, it’s a drive to be endured, a blank stretch of highway between L.A. and Palm Springs. For me, it’s the most familiar road in the world, a recurring loop that ties my hometown, my family, and my present life together.

I grew up in Santa Clarita, where the soundtrack was equal parts suburban hum and roller-coaster screams. Six Flags Magic Mountain was practically in my backyard, its skyline of looping tracks and steel peaks became the unofficial landmarks of my childhood. Teenagers compared which rides they could conquer, and the distant roar of coasters was just part of the atmosphere, like cicadas in other towns.

It was a place of malls and movie nights, garage bands in cul-de-sacs, and endless sunshine. Some people might call Santa Clarita a stopover town between L.A. and the grapevine, but to me it was a foundation: steady, familiar, and always buzzing with its own brand of energy. It’s my baseline, the measure I hold other places against.

When my family moved to Beaumont, I thought it was small. Quieter, slower, the kind of place people only knew because of a freeway exit sign. Coming back now, I see it differently.

Beaumont has its own texture. Antique shops with crates of vinyl and guitars collecting dust. The Cherry Festival every summer, where local bands cover everything from Tom Petty to Selena. Apple picking in Oak Glen once the air turns crisp. Small things, sure, but they add up.

What I dismissed as “quiet” when I was younger feels more like breathing room now. Beaumont is less about spectacle and more about noticing: the way the mountains look

at golden hour, the way the desert wind never really stops.

But Beaumont isn’t just its own town, it’s also my gateway into the Inland Empire, that wide swath of Southern California stretching east of Los Angeles and west of Palm Springs.

The I.E. isn’t a single city but a cluster of them: Riverside, San Bernardino, Redlands, Yucaipa, Banning, Joshua Tree, Big Bear, a patchwork of desert towns, mountain hideaways, orchards, outlet malls, taco stands, and music scenes.

Through Beaumont, I’ve gotten to experience that whole stretch of land. Apple picking in Oak Glen when fall hits, winding mountain drives up to Big Bear for alpine air, detours into Riverside for its Mission Inn and music venues, nights out in Joshua Tree

where the stars feel like part of the performance.

The Cabazon Dinosaurs are impossible to ignore, massive fiberglass creatures parked right off the 10. They’ve starred in movies, ended up on postcards, and been the backdrop for countless Instagram stops. For me, they’re part of the landscape, equal parts ridiculous and comforting.

Keep driving and the exits open up options. Head north and you’re climbing into the San Bernardino Mountains. Big Bear feels like a completely different world: pine trees, cold air, a lake that flips from summer parties to winter snowglobe. The energy is looser, slower, and it has its own music scene if you know where to look, acoustic sets in mountain bars, festivals tucked into the calendar.

Or you head further into the desert, toward Joshua Tree. That stretch of land has been mythologized by musicians for decades. Gram Parsons made it legendary, U2 named an album after it, and Pappy & Harriet’s still pulls artists who’d rather play to a dusty desert crowd than a stadium. Spend a night out there and you get why, the silence is heavy, the stars feel endless, and every sound carries. It’s the kind of place that makes music sharper, more necessary.

One of the best ways to feel the I.E. is just to let the radio guide you. L.A.’s indie and college stations fade to static as you hit the pass, replaced by Spanish-language ballads, Norteño beats, old-school country. By the time you’re in Beaumont, it’s Top 40 and throwback rock, songs made for belting with the windows down.

The I.E. has always been a crossroads like that. Riverside punk, San Bernardino hip hop, mariachi bands in strip mall restaurants, it’s a mix, layered and rough around the edges, but that’s what makes it interesting.

And while nothing beats a day in Palm Springs, the stops before matter just as much. Beaumont. Big Bear. Redlands. Yucaipa. Riverside. They don’t need to be detours, they’re destinations in their own right.

You can chase nostalgia at the Cherry Festival, dig through crates of vinyl in an antique shop, sip a date shake at Hadley’s, or stand under a T. Rex in Cabazon and feel like a kid again. You can catch a band in a bar in Riverside or watch the stars swallow the sky in Joshua Tree.

The Inland Empire has a way of producing voices that cut through. Olivia Rodrigo grew up here, too. Like me, she’s Filipino, and there’s something grounding about seeing someone with roots like mine come from the same stretch of land. It makes the highways feel less like borders and more like a current we’re both part of, a reminder that creativity can come out of suburbs, orchards, and desert winds just as easily as Hollywood.

Santa Clarita will always be the place that built my rhythm. Los Angeles is the home base I’m living now: loud, messy, endlessly alive. Beaumont is the rediscovery, proof that quiet doesn’t equal boring, that there’s texture in slowing down. Together they make a loop I keep driving, a circuit that reminds me who I was, who I am, and who I’m becoming. And every time I catch the dinosaurs rising out of the desert, I know for sure: the I.E. is its own destination.