JULY 10 - SEPTEMBER 9, 2023

Cover: detail of A Race-Castor and Pollux, 1984

Left: detail of Billie Holiday as Leda and Black Swan, 1984

Cover: detail of A Race-Castor and Pollux, 1984

Left: detail of Billie Holiday as Leda and Black Swan, 1984

“Emma Veoria Amos!” To say the birth name of this artist is to proclaim a fundamental aspect of her essence. For the names behind her name are freighted with history. They honor the matrilineal side of her family. Emma Holmes Amos (1872-1927) was her grandmother and Veoria Warmsley Shivery (1907-1999) was a close friend of her mother, India Delaine Amos (1908-1979), and Emma’s godmother. These women and those she admired (or befriended during her lifetime) form a plumb line of commemorative invention that runs straight through her work. With paint, ink, thread, and the written word, she has celebrated the physical, the intellectual and the creative power of women past, present and future.

In 1988, Emma Amos (1937-2020) created ten epic-sized hand-painted monoprints for the Atlanta Arts Festival drawing from her own past. Named Odyssey, the ensemble work shows us her journey from Atlanta, the “Gate City of the South” to New York in 1960, made possible by her family’s source of financial stability and social class: the Gate City Drug Store. Founded by her grandfather, Moses Amos (1866-1928)—the first Black pharmacist in the state of Georgia—its opening was announced on June 10, 1914 with a huge front page advertisement in The Atlanta Independent. Later, in a new location under a new name, the Amos Drug Store was operated for many years by her grandfather, mother, and father, Miles Green Amos (1898-1995). Amos’s out and away direction in her Odyssey reverses the trajectory of the journey that her friend and mentor Romare Bearden took when he returned to his birthplace, Charlotte, NC, eleven years prior. Like Amos, Bearden’s visual commemoration of his journey home, Black Odyssey (1977), is a series of collages and watercolors based on Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey (c. 8th century BC).

Amos’s Odyssey and Greek references relate to both Bearden and to her membership in Spiral (the prestigious Black artist collective) whose emblem, the spiral of the Greek mathematician and inventor, Archimedes (c. 287-c. 212), was featured in the catalogue of the group’s first showing held in the late spring of 1965 in New York City. Hale Woodruff, credited with selecting the name, says it was “because from a starting point, it moves outward, embracing all directions, yet constantly forward.”1 A pamphlet describing the show similarly declares: “As a symbol for the group we chose a spiral—a particular kind of spiral, the Archimedean one; because, from a starting point, it moves outward embracing all directions, yet constantly upward.”2

By dropping anchor into the ocean of the classical past, these artists felt free to draw inspiration from any time, any place, and any culture. This was especially difficult for African American artists who were constrained by racism. “When African American artists cross boundaries,” Amos said, “we are often stopped at the border.”3 Thus, in a terrible irony, when we see the works of Cy Twombly infused with classical references, their meaning is immediately apparent, while African-American explorations into classical antiquity are still seen (assuming that they are seen at all) as aberrant, inappropriate or down-right peculiar. This idea is far from the truth. Classical studies formed the core curriculum in liberal arts for white and Black students for many years, and most HBCUs took pride in offering Greek and Latin to their students.4

It is no accident that the series begins with a page from Zora Neale Hurston’s Mules and Men, for the Odyssey’s viewpoint is pronouncedly female.5 There is a woman and/or women in eight of the ten hand-painted monoprints. In the first panel, we see a woman and man in street clothes moving toward us. They foreshadow a gloved Sugar Ray Robinson and a self-portrait of Amos herself running in the tenth panel. This pair of athletes are winning the ἆθλον, or athlon, the ancient Greek

noun for contest. Put in front of the Hall of Justice with its four Ionic columns and raised Romanstyle podium, the two athletes are leading the way for justice to follow. Indeed, the classical façade seems like the grill work of a locomotive whose cars must be directed by the athletes to avoid going off track.

By taking hold of ‘Ariadne’s thread’ we can move through the labyrinth of Amos’s work and discover the classical elements that she has woven into it.6 Two of her earliest works are Pompeii (Red) and Pompeii (White) which were made during or immediately after the period she spent studying etching and textile design at the Central School in London in the late 1950s. While the two works may have been something of an academic exercise for Amos, we can see that she is thinking about Pompeii’s history as a city that was turned red in 79 A.D. by the superheated magma from Mount Vesuvius, and later turned white ash after the eruption. The backgrounds of both pieces are marked by a series of marks which hint at some ancient, long-lost graffiti. Through the irregular shaped rondels, we can see the walls of a ruined building and four scorched, destabilized columns.

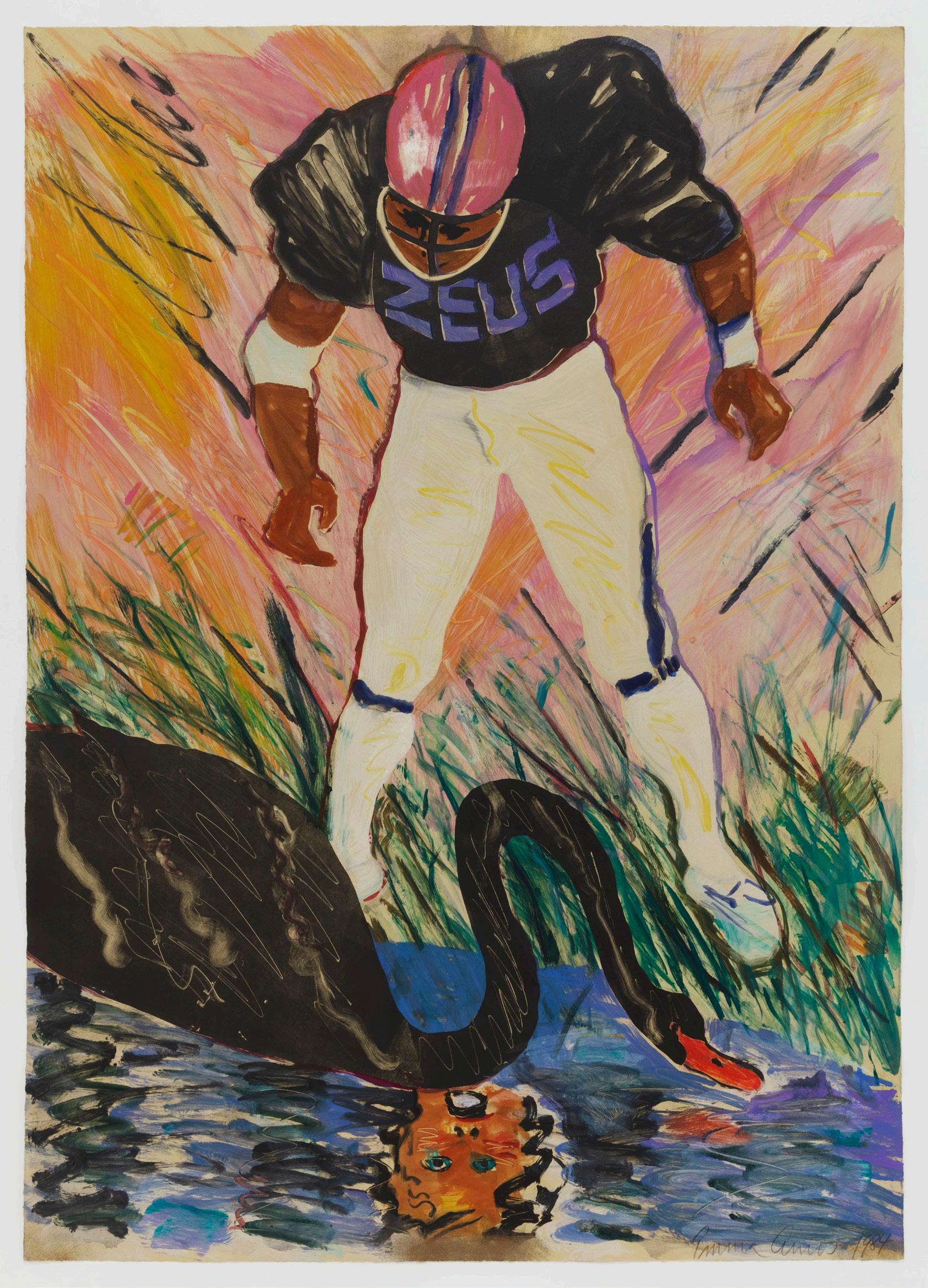

In 1980, Amos joined the faculty of the Mason Gross School of Art at Rutgers University. The biggest man on campus then and now was Paul Robeson (1898-1976), where he was an All-American football player, class valedictorian and Phi Beta Kappa graduate, class of 1919. As a child, he had studied Greek and Latin with his father, Reverend William Drew Robeson, a study he continued at Somerville High School in New Jersey, and later at Rutgers University. He also tutored the son of his football coach, G. Foster Sanford, well enough for Sanford Jr. to pass entrance exams at the University of Pennsylvania. While we cannot be certain that this Zeus is Robeson, Amos had an enduring interest in Robeson and placed him in several works including Thank You Jesus for Paul Robeson (and for Nicholas Murray's photograph-1926) (1995), Paul Robeson Frieze (1995), Robeson bell hooks KEYS (1996), A Reading at Bessie Smith’s Grave (1999) and Paul (2017).

In Zeus, Zeus gazes down upon an alter ego, the swan, the feathered guise he used in seducing Leda. Regularly depicted by artists as white, Amos’s swan is decidedly Black and stands out in sharp contrast to Zeus’s white socks and pants. Below the swan and aligned vertically with Zeus’s head is a shallow pool in which a self-portrait of Amos floats. Here Zeus is “reflecting” upon the object of his affection, and is perhaps showing the viewer how their aqueous assignation would, could or did take place. Amos’s Billie & Black Swan, a.k.a. Billie as Leda, also made in 1984, shows us that both Zeus and his avian disguise had engaged her imagination.

The image also reminds the viewer of connections to old Atlanta or to Harlem: in this monoprint one reads the logo of Black Swan Records, the first well-known label to be owned and marketed to African Americans. It was founded in 1921 in Harlem by Harry Herbert Pace (1884-1943). Pace had graduated in 1903 as valedictorian of his class at Atlanta University at the age of 19. He had taken the classical curriculum in college and spent two years teaching Greek and Latin at Lincoln Institute in Jefferson City, Missouri, before focusing on running the Pace Phonograph Company. Before Pace’s label, however, was the original ‘black swan’—the singer Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield (1819-1876) who was born in slavery in Natchez, Mississippi, and dubbed by a journalist from the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser in October of 1851 as “the Black swan.”7

Embodying the “deft assimilation of photography into painting, (a distinguishing characteristic of Amos’s work),” as Lisa Farrington describes it, Amos has positioned duplicate photos in Paul Robeson and Egyptian King, one clear and dark, and the other faded white, of Robeson in all of his Olympian beauty as captured by Nicholas Murray (1892-1965) in 1926.8 Below the two photos is one side of an Attic red-figure stamnos (470-460 B.C.) from the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford. It shows Hercules slaying Busiris, king of Egypt, along with Busiris’s son, Amphidamas and Busiris’s herald, Chalbes.9 Busiris had been sacrificing strangers as a fertility rite and Hercules was determined not to be the next victim.10 This exploit was often represented on vase paintings from the 6th century B.C. on, with the Egyptian leader and his companions being represented as so-called “negroes”. Lest we miss the connection, Amos has placed a text below the vase painting which breaks off at the end: “Busiris, son of Poseidon, and an Egyptian king, slaughtered on the altar of Zeus all foreigners who entered Egypt. Heracles…”11 Amos had used the same image six years before where it appears in triplicate on the right side of Amos’s diptych, Classic and Universal (1995). Murray’s photograph of Robeson reminds the viewer of the Farnese Hercules, the massive marble sculpture in Naples’s Museo Archeologico Nazionale made by Glykon of Athens in the third century A.D. The dark Robeson and light Robeson suggest that Busiris and Hercules may be one and the same in Amos’s eyes.

With this huge, color-saturated canvas, Amos has taken her viewers “under the big top.” Between the tent poles, the performers work without a net. For them the chronology of time has collapsed. Spinning in a vortex, the performers fall headfirst and downward through the air; their hands are grasping and empty. However displaced they may be in the world, the show must go on, either in the uncovered amphitheater on the far right, or beneath the dome of the small nearby sanctuary shaped like the Temple on the Mount in Jerusalem. On the left, a pair of white horses take a hairpin turn at full gallop around the outer edge of the arena while the daughters of Aeolus, the god of the winds, set the scene to music. Notes pour out from their lyres into the air, reminding the viewers of the wind-driven aeolian harp which was sent by divine powers to the Greek god, Hermes, and to David, King of Israel and Judah. The image also evokes the memory of the gilded wagon of sound, the so-called ‘steam car of the muses,’ the calliope which went on parade at every circus and whose namesake was the Greek muse, Calliope. Amos has drawn us into the first, the largest, and most famous track and entertainment venue in all of Rome and all of its empire, the Circus Maximus. Here the Romans watched beast hunts and gladiatorial contests, enjoyed public feasts, and various religious festivals. They saw theatrical presentations, watched jockeys on horseback, charioteers commanding their steeds, and long-distance runners. With this image she reminds us that, for each of us, the greatest arena of all is the encompassing circle of our lives from birth to death.

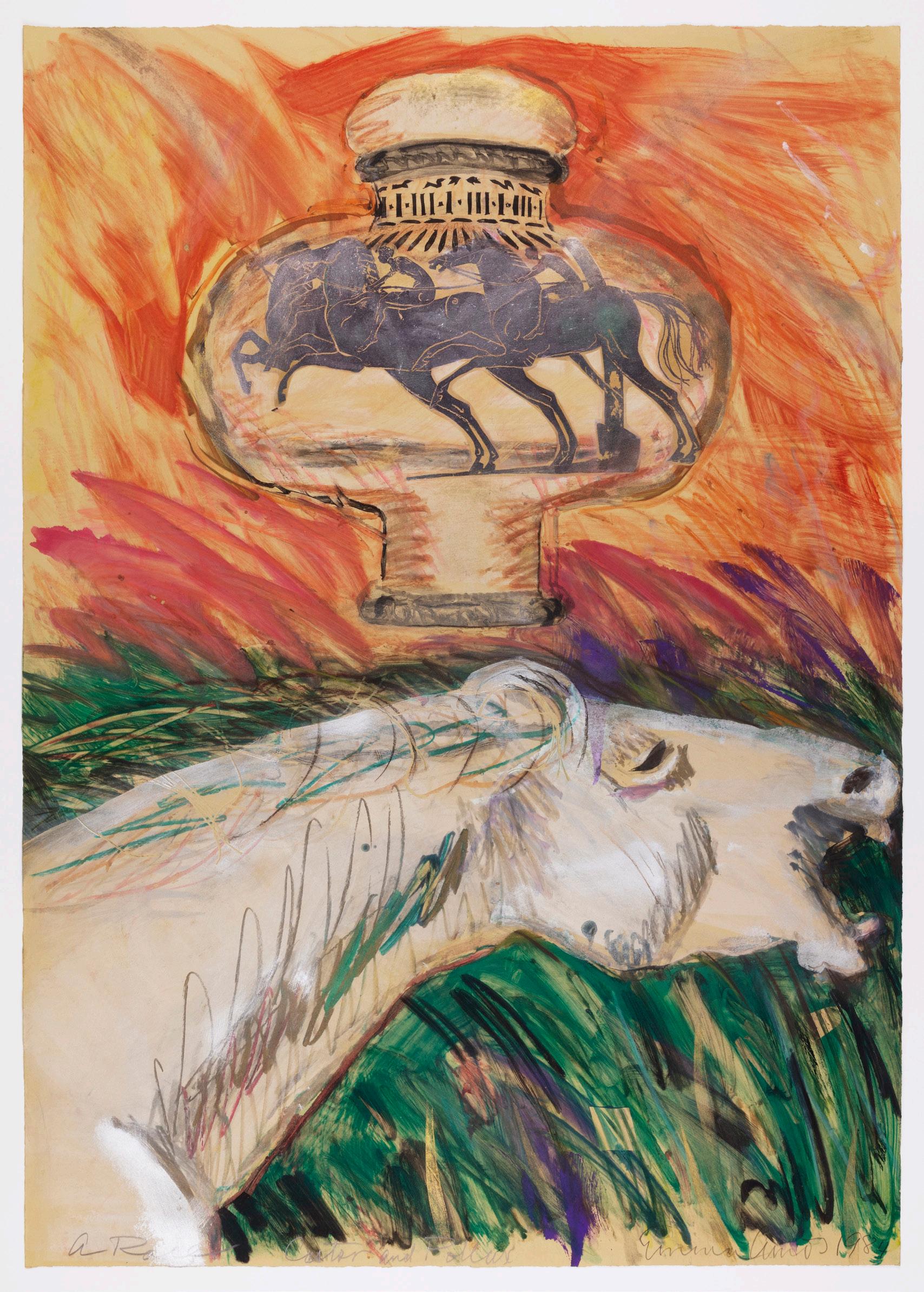

This monoprint combines the artist’s interest in antiquity with the joy she took in the dynamism of men and animals in action. She has taken an image depicting a horse race from a late sixth century Black figure amphora and placed it on a bulbous vase shaped along the lines of a psykter (ψυκτήρ), an ancient Greek wine cooler known for its round body and high, narrow foot.12 But Amos has reversed the image. On the ancient amphora the jockeys drive their steeds to the right from the goal post that is visible behind the hindquarters of the last horse, but on Amos’s vase they are galloping to the left. Below them is the head of a white horse, its teeth exposed and nostrils flaring with exertion. Here we have Amos’s interpretation of the Dioscuri, the twin sons of Leda whose names were Castor and Pollux. They were the patrons of horsemen in Graeco-Roman antiquity and at one time had abducted the daughters of Leucippus (Λεύκιππος), whose name comes from the Greek words for white (λευκός) and horse (ἵππος). The head of the horse itself looks like the heads of a pair of horses at Rome’s Fontana dei Dioscuri (The Fountain of the Dioscuri) in the Piazza del Quirinale. The father, personified by the horse, is no doubt racing after Castor and Pollux in an attempt to save his daughters.

Way Away, an acrylic on canvas (1996), and Aida, a silk collagraph monoprint (1999) testify to Amos’s interest in Egyptian antiquity. The male figures in Way Away, while walking in opposite directions, are both looking to the left. The position of their splayed-out arms recall figures out of an Egyptian wall painting. The nude figure on the left reminds the viewers of the so-called “sun-burned faces” of the people of Ethiopia (Αἰθιοπία) as they were described by many ancient Graeco-Roman authors. The figure on the right, however, is wearing the pleated kilt of a Roman soldier and muscles of his chest suggest the contrapposto armor of a Roman cuirass. In Aida, the figures are reversed. Here we see two women dressed in clothing from different eras who are looking toward each other. The Ethiopian princess is barefoot while the modern ‘Aida’ wears backless shoes called ‘mules.’ The princess stands up on a white plinth with her body facing forward, while the modern ‘Aida’ stands on the ground with her back turned to the viewer. Her head is turned to the left and her eyes are raised up at the Princess in sympathy and suppliance. The two women mirror each other, and they are having a conversation across the centuries. The wrists of both are constrained; the Princess’s fasteners are in front of her body and the modern Aida stands with her arms behind her back and her hands tightly handcuffed. The plinth’s red-lettered graffiti make certain that we understand that the women have been “captured.” They shout out “stop!”

Measuring, Measuring, 1995 in the collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art

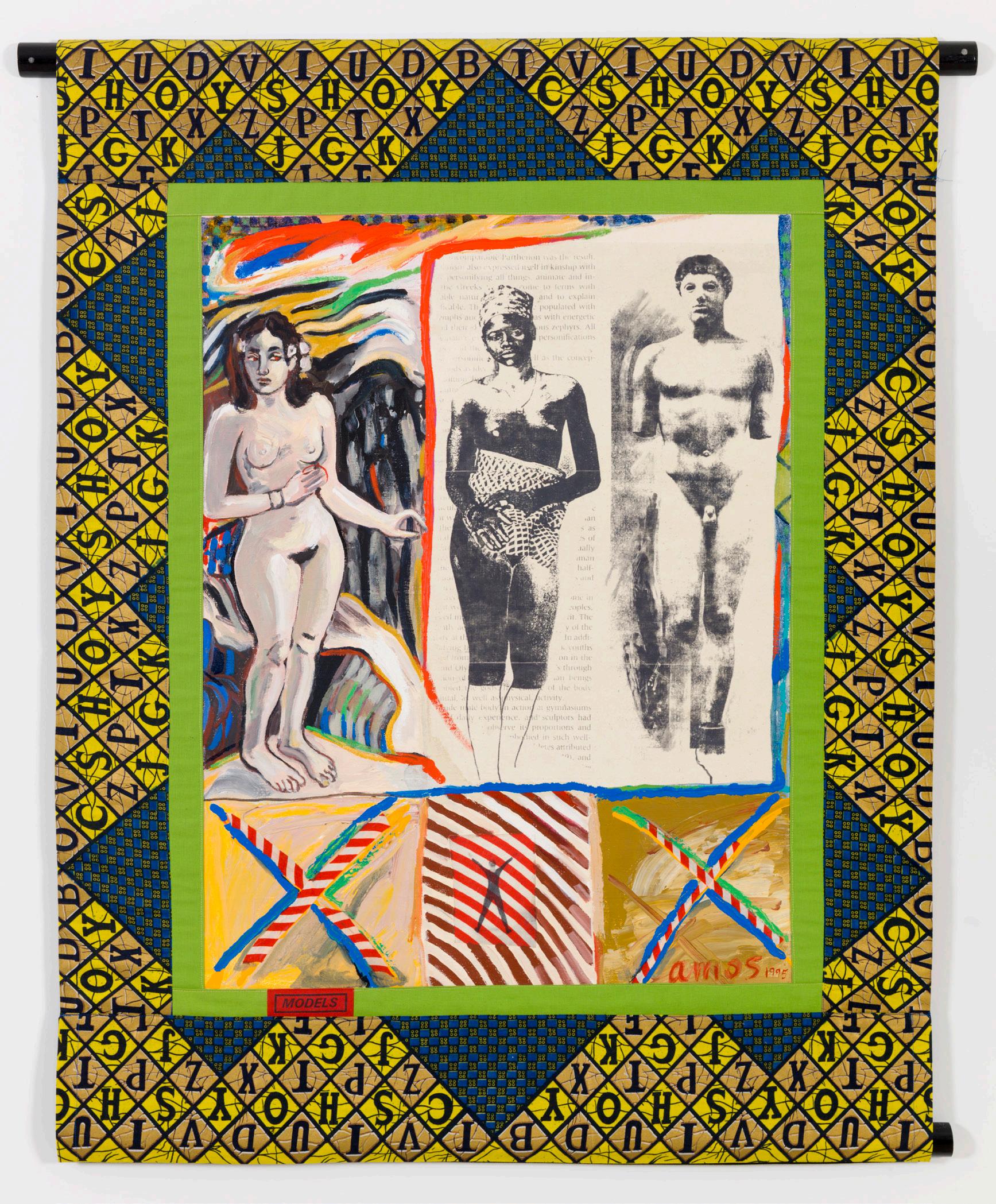

On the right of this large canvas is an image of a marble statue that Amos remembered from her childhood. This is the Kritios Boy, a kouros made c. 480 B.C. whose head and torso were found on the Acropolis in 1865 and 1888 respectively. He holds the same position in a similar work, Measuring, Measuring, which Amos also made in 1995. These paintings present the audience with an anthropological map of the human form moving across the continents from east to west: in these two works, Amos presents Aristide Maillol’s torso of Venus, an indigenous African woman and the Kritios Boy in Measuring, Measuring; in Models she presents Gauguin’s Ta Nave Nave Fenua as well as the same indigenous African woman and the Kritios Boy again. The three figures in Measuring, Measuring also appear in the same arrangement in Amos’s diptych Classic and Universal, made in 1995 as well.

Amos had an enduring memory of the Kritios Boy kouros. In 1999 she recalled: “About that kouros. As a child I was taught by the educated Black scholars who were relegated to teaching in elementary and high schools of Atlanta’s then segregated school system. I learned that the Greeks, who eschewed manual labor, used slaves as models for their sculptures, which celebrated the beautiful bodies of the gods. I then equated all slaves with the Black slaves of America, a few of whom I had been taken to visit when I was little. Though it may have been wrong to believe Ethiopians and West Africans were models for the treasured statues, I loved the thought. It helped me get through the endless readings that dismissed the presence of Blacks in history.”13

Standing on the same level and in gentle contrapposto, the three nudes hypnotize their viewers with their beauty. The figures, differing in gender, color, place and era, are captivating. But while the figures seem momentarily freed from a straitjacket of whiteness, clues in the painting suggest caution. The three Xs placed beneath the figures warn us not to harbor too much optimism about parity.

Fabric, whether African or woven from Amos’s own hands, gave Amos “an additional palette”, as she described it with which to create. “I’m a weaver, and actually at one idiotic time I wove my own canvasses.”14 Her dexterous amalgamation of the “‘fine art’ of painting with the ‘artistry’ of textiles,” as Lisa Farrington astutely observed, is “nothing short of alchemy.”15 Describing Amos’s art as alchemical is certainly correct. She saw her family members practicing their own form of pharmaceutical [al]chemistry: reading prescriptions written in Latin, dipping into apothecary jars, drawing from glass vials, pounding powders with mortar and pestle, and then arranging all these parts into something entirely new—their own hand-designed medicines. Amos took similar care in combining disparate materials in creating her work. She drew from every source and era, merging elements from Africa and antiquity with the modern and post-modern worlds. To do this she used her own cloth as well as wax dyed batiks exported to Africa from Holland, and fabric made by African men and women. In this way Amos is a modern Penelope. She is like that heroine who in Homer’s Odyssey brought up her son, sustained her home while outwitting her enemies with her loom. Stitched, stretched, painted, and rearranged, these works by Amos invite us to follow the warp and woof of her own unique weave, threads of which are clearly classical.

Dr. Michele Valerie Ronnick is a Distinguished Service Professor in the Department of Classical and Modern Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at Wayne State University in Detroit. Her scholarship includes studies of Latin literature, the classical tradition, and in particular the reception and impact of classical studies upon people of African descent. Classica Africana, a.k.a. Black classicism is a field of scholarship that she opened up in the 1990s. Her photo installation featuring the faces of 19th and early 20th century Black classicists, funded by the James Loeb Library Foundation at Harvard University, has been in circulation in the US and UK since its inaugural exhibit at the Detroit Public Library, September 2003.

1 See page 185 in Sharon Patton, African-American Art (New York and London: Oxford University Press, 1998).

2 https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/07/30/extract-or-arare-pamphlet-from-a-historic-black-art-exhibition-by-the-spiralcollective

3 See page 38 in Emma Amos, “Measuring Content,” in Looking Forward Looking Black, ed. Jo Anna Isaak (Geneva, NY: Hobart and William Smith Colleges Press, 1999): 38-39.

4 On this topic see, Michele Valerie Ronnick,“Classicism, Black, in the United States” by Michele Valerie Ronnick https://oxfordaasc.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.001.0001/ acref-9780195301731-e-40755

For an earlier version of this article see Michele Valerie Ronnick, Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, eds. Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (New York City: Oxford University Press, 1999): 120-123.

5 The book, Mules and Men (1935), is a collection of African American folklore. The page in Amos’s work comes from the story, “Member Youse a Nigger,” found in chapter 5.

6 I explored this idea in January 2020 with a paper I delivered at “Busboys and Poets” as part of the Society for Classical Studies’s annual meeting in Washington, D.C. https://classicalstudies.org/every-time-i-think-about-color-it’spolitical-statement-classical-elements-art-emma-amos

Bearden has his own questions about the coloration of Pompeiian mural decoration and said: “Even in what remains of some of the Pompeian frescos, it appears apparent that in spite of the orangered backgrounds, the figures and drapery were painted in tones of black, white and gray.” See page 15 in Romare Bearden, “Rectangular Structure in My Montage Paintings,” Leonardo 2 (Jan. 1969): 11-19.

7 See David Suisman, “Co-Workers in the Kingdom of Culture: Black Swan Records and the Political Economy of African American Music,” The Journal of American History 90 (March, 2004): 1297; 1301 and Julia J. Chybowskii, “Becoming the Black Sawn in Mid-NineteenthCentury America: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield’s Early Life and Debut Concert Tour,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 67 (Spring 2014): 125-6.

8 See page 5 in Lisa Farrington, “Emma Amos: Art as Legacy,” Woman’s Art Journal 28 (2007): 3-11. Nikolas Murray’s first name is sometimes spelled Nicholas as well as Nickolas.

9 Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, #AN1896-1908. G. 270, bequeathed by M. Edmund Oldfield in 1901.

10 See Leonhard Schmidt, “Busiris,” Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography, ed. William Smith (London: John Murray, 1849): 51 who says: “Egypt had been visited for nine years by uninterrupted scarcity, and at last there came a soothsayer… who declare that the scarcity would cease if the Egyptians would sacrifice a foreigner to Zeus every year. Busiris made the beginning with the prophet himself, and afterwards sacrificed all the foreigners that entered Egypt. Heracles on his arrival in Egypt was likewise seized and led to the altar, but he broke his chains and slew Busiris, together with his son Amphidamas or Iphidamas, and his herald Chalbes. This story gave rise to various disputes in later times, when a friendly intercourse between Greece and Egypt was established, both nations being anxious to do away with the stigma it attached to the Egyptians.” Some ancient writers reacted to the story by denying that the Egyptians carried out human sacrifices. Others tried to show that Heracles lived later than Busiris, that there never was a king of that name or that the people of Busiris were an inhospitable lot.

11 The text was taken from page 143 of Roy Willis’s World Mythology (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1965).

12 This is the terracotta neck-amphora, attributed to the Leagros Group, c. 510-500 B.C., 07.286.80 in Gallery 171 of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

13 See page 38-39 in Emma Amos, “Measuring Content,” Looking Forward Looking Black, ed. Jo Anna Isaak (Hobart and William Smith Colleges Press: Geneva, NY, 1999): 38-39.

14 See page 16 in Lucy R. Lippard, “Falling, Floating, Landing: An Interview with Emma Amos,” Art Papers 15 (1991): 13-16.

15 See page 5 in Lisa Farrington, “Emma Amos: Art as Legacy,” Woman’s Art 8 (Spring-Summer, 2007): 3-11.

Zeus, 1984

Monoprint with pochoir and hand coloring

41 1/2 x 29 3/4 inches (105.4 x 75.6 cm)

Exhibition history:

Emma Amos: Changing the Subject: Paintings and Prints 1992-1994, Art in General, New York, 1994

Emma Amos: Paintings and Prints 1982-1992, The College of Wooster Art Museum, OH, 1993; travelled to the Wayne Center for the Arts, OH; and the Studio Museum in Harlem, NY

Billie Holiday as Leda and Black Swan, 1984

Monoprint with pochoir and hand coloring

29 3/4 x 41 1/2 inches (75.6 x 105.4 cm)

Variant edition of 3

Exhibition history:

Emma Amos: Changing the Subject: Paintings and Prints 1992-1994, Art in General, New York, 1994

Emma Amos: Paintings and Prints 1982-1992, The College of Wooster Art Museum, OH, 1993; travelled to the Wayne Center for the Arts, OH; and the Studio Museum in Harlem, NY

Prints by Women: A Survey of Graphic Work by American Women Born Before World War II, Associated American Artists, 1986

Into the Air, Jump Birdpeople, Cats, Horses, 1987

Exhibition history:

Paintings, Women Artists Series, Douglass College, Rutgers University, New Jersey, 1989

Exhibition history:

Color Odyssey, Georgia Museum of Art, GA, 2021; travelled to Munson Museum, NY; and Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA

Emma Amos: Changing the Subject: Paintings and Prints 1992-1994, Art in General, New York, 1994

Emma Amos: Paintings and Prints 1982-1992, The College of Wooster Art Museum, OH, 1993; travelled to the Wayne Center for the Arts, OH; and the Studio Museum in Harlem, NY

Emma Amos: Paintings, Mary H. Dana Women Artists Series 1988/1989, Mabel Smith Douglass Library, Rutgers University, 1989

Selections: Six Contemporary African American Artists, Williams College Museum, Williamstown, MA, 1989

New Works by Emma Amos, Jersey City Museum, NJ, 1988

The triptych Flying Circus (1987), a large painting bordered with strips of colorful African textiles, depicts three women and a man falling through the night sky above a coliseum and a cathedral. Two galloping white horses, a ladder, a cheetah and a lyre-bearing Orpheus fall with them, like space debris. In Amos’s paintings, civilizations appear in disarray, while falling seems a metaphor for anxiety and dislocation. Like much of Amos’s recent work, this triptych seems to chart moments of the artist’s alienation from both Black and white worlds.

— Anastasia Aukeman, review of Amos’s Painting and Prints exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem, published in Art in America January 1996

Models, 1995

Acrylic on canvas with African fabric borders and photo transfer

51 x 39 inches (129.5 x 99.1 cm)

Exhibition history:

Color Odyssey, Georgia Museum of Art, GA, 2021; travelled to Munson Museum, NY; and Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA

Historias Afro-Atlanticas, Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, Brazil, 2018

Way Away, 1996

In the 1950s, Amos was introduced to the possibilities of printmaking at the London Central School of Art where she was a student, and from which she subsequently received a diploma in the etching technique. For the next two decades, lacking sufficient time and space to devote to painting while caring for her growing family, she continued her work as an etcher at Robert Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop. Amos eventually found the technique too constraining and began to experiment with other printmaking techniques that would convey the same degree of expressiveness that characterize her paintings. It was her investigation of the monoprint technique in 1984 that loosened Amos’s handling of line and form in her prints. Because the process in creating monoprints is similar to painting, she could more easily merge her subject matter with the gestural brushstrokes found in her paintings.

In 1988, Amos applied the monoprint technique in the creation of another major series of prints, entitled Odyssey. It was executed at Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop with the assistance of master printer Kathy Caraccio. The series consists of ten large monoprints with photographs of the artist’s family. They were printed on rice paper with printer’s oil-based colored inks, hand-painted on oversized plates. The series focused on 100 years of the history of the artist’s family in Atlanta, from the period shortly after slavery up to the 1960s. It was inspired by the splendid collection of family photographs belonging to Amos’s parents, and represents pride in her family and in their achievements. Combined with imagery created by the artist, these photographs transmit a narrative intended to be read left to right.

Exhibition history for Odyssey:

Emma Amos: Changing the Subject: Paintings and Prints 1992-1994, Art in General, New York; 1994

Emma Amos: Paintings and Prints 1982-1992, The College of Wooster Art Museum, OH, travelled to the Wayne Center for the Arts, OH, 1993; and the Studio Museum in Harlem, NY, 1995.

Loaded, curated by Glenna Park, Blue Star Art Space, 1989

Odyssey-And Our Paths Cross Again, Atlanta Arts Festival, 1988

Artist Statement from the Atlanta Arts Festival, 1988

Once upon a time in Georgia it was a criminal offense to teach Blacks to read and write.

Moses Amos, my mother's father, was born in Georgia in 1867, the first of his 14 brothers and sisters to be born free. Educated by apprenticing himself to a white druggist, he became the first Black pharmacist registered in the state. This grandfather I never knew was inspired by his hunting friend, Booker T. Washington, to help send more than 20 Black children through school.

Moses' wife, my grandmother Emma, born about 1878, was a graduate of an Atlanta teachers' preparatory college, later to become Atlanta University. She taught public school for over 10 years before marrying and leaving the school system, because of a then common requirement that teachers be unmarried. Emma Holmes Amos was part Cherokee, African and Norwegian. A handsome woman, she was an excellent cook and a hostess who entertained with style. Elegant and cultured, could she have been from a family of free Blacks? Of course, I prefer thinking that, rather than the more likely and less attractive probability that her family were slave house servants with the usual airs. There were free Black families during slavery, usually in the North and West, but even in the South some Blacks were free, if they were tied to Indian peoples. A Native American connection might account for the family assertion that the Holmeses (from the Norwegian name, Holm) were skilled and literate people at least one generation before Grandma Emma.

I used to enjoy speculating about my Indian ancestry. I imagined how the families might have mixed, as I knew there were cases of intermarriage between Blacks and Native Americans. Maybe Blacks helped Indians escape during the time of the forced Cherokee "Death March" to the West, just as many Blacks were helped to escape slavery by Indians.

It is true that many Black people have Native American blood. It is also true that some Indians bought, sold and kept slaves. As they were always on the edge of being themselves enslaved, Indians needed to separate themselves from the concept of being chattel. So some tribes wrote laws to prohibit intermarriage, while closing their eyes to commonlaw arrangements. Indians were usually more compassionate towards slaves than white slaveholders and were often suspected of aiding runaways.

The lexicon of miscegenation (mulatto, octaroon, quadroon) was never used in polite Black Atlanta society. As children, my friends and I wondered how we all got to be such different colors. We were either told a long story about slavery or simply that "so-and-so's grandfather was white," and that

was that. Raymond Andrews writes about the reactions to just such a family in his memoir, The Last Radio Baby, illustrated by his brother, Benny Andrews, and published by Peachtree Publishers, Ltd, Atlanta, 1990. Light-skinned children and their mothers were usually not ostracized or penalized by their own slave families. But the punishments the master's wife might inflict against mother and child under such circumstances would make chilling conjecture. Slave women were raped, or sexually coerced and degraded (in spite of having husbands and children) because it was the master's prerogative, because they were "property," or as punishment for being "uppity." Slaves tried to maintain families, in spite of the slave owners' vicious practice of selling children away from mothers. Staying alive and together was difficult enough without recriminations from the other Blacks about half-white children.

Short memories about paternity, and long memories about pain and who inflicted it, were survival techniques.

My father's grandfather was white. An Irishman named Donnelly from Hogansville, he raised redheaded, blue-eyed Minnie, my other grandma, as a servant to his other daughters. Her white halfsisters later became nuns and my father remembers them, in their habits, visiting and bringing presents when he was little.

Most Southern Blacks have some white blood.

My father, Miles Green Amos, born in 1897, was elected to the Atlanta City Executive Committee in 1953, making him one of the first Black men to be elected to public office since Reconstruction. In that same election, the President of Atlanta University, Dr. Samuel Clement, was the first Black elected to the School Board; this was the most important first for that decade's changing politics. A pharmacist like his uncle Moses, Miles graduated from Wilberforce College in Ohio, and then the Cincinatti College of Pharmacy, in 1923.

My mother, India DeLaine Amos, grew up on Houston Street in Atlanta with Grandma Emma, Grandpa Moses and brother Moses Jr. They lived in a large comfortable house, with a room-size playhouse in the backyard. Next door were the five beautiful and accomplished Dobbs sisters, one of whom is Mattiwilda Dobbs, the former Metropolitan Opera singer. My mother's favorite of the sisters was Irene Dobbs Jackson, later to become a concert pianist, a Professor and Doctor of French languages and the mother of Atlanta's Mayor, Maynard Jackson. India graduated from Nashville's Fisk University in 1930, with a degree in anthropology. Co-owner and full-time manager of Amos Drug Store from 1935 to her retirement in 1969, she was also active in the social and literary life of Black Atlanta. My mother was selected "Woman of the Year in Business" in 1949 by the Delta Sorority. I remember being proud that she was different from most of the working women we knew, who were school teachers or social workers.

My brother Larry and I attended the E. R. Carter elementary school, and Booker T. Washington High School, graduating before Atlanta public schools were desegregated. Larry spent a year at Morehouse College, then graduated from Lafayette College in Pennsylvania and went on to receive MBA and Law Degrees from Indiana University.

Many of the friends who grew up with us also left Atlanta to go to college and never returned: Nathaniel La Mar, Harvard to New York; David Levering Lewis, Fisk, London School of Economics and Columbia to New York and Washington; Gail Kendrick Morris, Ohio Wesleyan to California; Joyce McLendon, Connecticut to Washington; Charlotte Giles, Fisk and Indiana University to West Virginia; Suzanne Hill, Sarah Lawrence to… and so on.

I began making art from age 5, and was encouraged to paint by family and friends. As an 11-yearold, I was enrolled in Ruth Hall Hodges’ oil painting class at Morris Brown College, and exhibited at Atlanta University’s Annual art shows for 3 years until I left for Antioch College at 16.

There were some uneasy memories, too.

Like being pushed off the road by a KKK march near Stone Mountain one evening in 1947, and seeing my father in a submissive not-in-control role for the first time.

Like finding no rest rooms, or restaurants we could use when we shopped downtown.

Like being given second-hand books in elementary school.

Like taking the SAT’s at Emory University where the white kids whispered and pointed at the Black kids to wreck our concentration.

The richness of my city's Black cultural life gave me a path to follow. I especially remember seeing murals by Hale Woodruff and Aaron Douglass at Atlanta University, and reading in "Black" public libraries—first in the main public library on Auburn Avenue, and then at the new library nearer to me on the West side. My parents proudly collected books by Black writers and poets like Georgia Douglass Johnson, Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes, and my father shared stories with Zora Neale Hurston on her anthropological treks through the South. W.E.B. DuBois was a guest in our house a few times. My mother took us to hear Roland Hayes, Hazel Scott, Mattiwilda Dobbs, the Fisk Jubilee Singers and many other artists who performed in Atlanta because it was home to an educated Black audience. My father took us to see Duke Ellington, Piano Red and Fats Waller. Larry and I were introduced to Paul Robeson and Uta Hagen backstage during the Broadway production of "Othello" on the trip to New York that also took us to see "Oklahoma!" and "Carmen Jones." On another New York trip we saw Nipsey Russell at the Baby Grand night club, and Archie Moore and Sugar Ray Robinson fights at Madison Square Garden.

Coming back to the South after graduating from Antioch College in Ohio and the London (England) Central School of Art, I found a much freer atmosphere than the one I remembered. Though many of my friends had left Atlanta forever, I made new ones, and even had a solo show at a mainstream Atlanta gallery during the 1959-1960 season.

These works recreate a history I wish to share with all Americans, especially young people with little access to family story tellers. The story of my family may seem unusual to people unfamiliar with the lives of educated Black Americans. Odyssey ends with me leaving Atlanta at the beginning of the 1960's, when a new South was rising and everything seemed to point to and invigorating and rewarding journey ahead for the whole nation. As a recorder of this bit of history I am a "witness to the future," as Alice Walker wrote in In Search of Our Mother's Gardens:

We are a people. A people do not throw their geniuses away. And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and as witnesses for the future to collect them again for the sake of our children, and if necessary, bone by bone.

Odyssey is my homage to family, friends, mentors, heroes and the stories that formed me in Atlanta, the "Gateway City of the South." Following is a list of books you might wish to read to augment my personal perspective.

Davis, Angela Y., Women, Race & Class, Random House, Inc., New York, 1981.

Du Bois, W.E.B., The Souls of Black Folk, The Blue Heron Press, Inc., New York, 1953.

Frazier, E. Franklin, Black Bourgeoisie, the Rise of A New Middle Class in the United States, Macmillan, New York, 1957.

Jones, Jacqueline, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work and the Family, From Slavery To The Present, Basic Books, New York, 1985.

hooks, bell, Black Looks: Race and Representation, South End Press, Boston, MA, 1992.

Katz, William Loren, Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage, Atheneum, New York, 1986.

Lewis, David Levering, When Harlem Was In Vogue, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1986.

Lightfoot, Sara Lawrence, Balm in Gilead: Journey of a Healer, Addison-Wesley Publishing Co. Inc., Reading, MA, 1988.

The climax, so far, of Amos’s Atlanta works is a series of ten oversized monoprints with photographs on rice paper called Odyssey, which she made with master printer Kathy Caraccio at Bob Blackburn’s studio in 1988. It was exhibited at the Atlanta Arts Festival that year, and shown again in San Antonio in 1989 in a show of political art, “which it is,” says Amos. “It’s always been my contention that for me, a Black woman artist, to walk into the studio is a political act.”

The imagery is powerfully narrative and visually fleeting, printed a kind of synchronistic rhythm. It begins with an image based on, and quoting of Mules and Men, a Zora Neale Hurston story, “because Odyssey is so middle class that you must know I remember where we came from and what it means to be Black. I’ll tell you a story:

John, who is a slave, saves the master’s children. The missy just thanks him for it, but the master says, I’ll send you to Canada if you fill up the barn with lots of corn or whatever, so John works himself really hard and the time comes and he is freed. The master says, I hate to get rid of a good nigger like you, but he gives him some clothes for his pack and sends him off. Then, Zora Neale Hurston writes, John starts off down the road and Massa yells after him, John, the children love ya. John says yassuh. John, I love ya. Yassuh. And Missy like ya. Yassuh. But remember, John, you still a nigger. Yassuh. As far as John went down the road, he was hearing, John, Oh John, Children loves you and I loves you and the Missy likes you. Yassuh. But you still a nigger. The old Massa kept calling till his voice was pitiful, but John kept right on stepping to Canada.”

Odyssey was based on Amos’ parents’ collection of “gorgeous family photos.” There is a fine portrait of her grandfather, Moses Amos, who was the first Black pharmacist in the state of Georgia. The youngest of 14 children, he was the first to be born out of slavery, in 1867. “Odyssey,” says Amos, “came from a need to express my pride in my family’s achievements. People assume you come from nothing, that you have no history. Odyssey was an homage. I’m trying to learn as much as I can through oral history and then put it down in my work—it’s a way of rewriting history. I love the idea that most of the good stuff comes from just people talking. I can put this in visual form, and it may mean something to somebody. So that’s what Odyssey is—a remembrance of Atlanta from a very early time—just after slavery all the way up to the ‘60s. It’s rampant with middle class Black glory, but it’s tempered by the fact that we’re nothing but ‘niggers’ in the ‘40s and ‘50s.

On looking back I find that past events form designs and patterns in the scrapbook of the mind. Paths have rampled and crossed, signs have been seen, calamity and fortune have mixed unevenly.

Here are pieces of my past: part of the history of Atlanta we all share. Our successes, failures, joys, evils, and accomodation to inequity add to an odyssey that includes me leaving and new Atlantans arriving. I am a “witness to the future.”

Pictured in this work: Grandma Emma, the artist’s grandmother Emma Holmes Amos, who was part Cherokee, African, and Norwegian, c. 1898 when she had graduated from college and was a teacher in an Atlanta school.

Emma Amos's Odyssey description, 1988

Article in the Dixie Pharmaceutical Journal, 1928

In Tea Ladies, Emma Holmes Amos and her friends were photographed dressed in Japanese kimonos and hairstyles for a Sunday tea party in Atlanta, c. 1900. An educated woman, Holmes Amos attended Atlanta University and graduated in 1891.

In transfer photo: Emma, Mrs. India, Ophelia, Euchee, Mrs. Hurst, Missie Gaines, Lonella, Ruth.

India, Miles and the Children’s Party, depict the artist’s parents at an early age. On the left is India Amos, the artist’s mother, c. 1920 at twelve or thirteen years old, Atlanta. On the right Miles G. Amos, the artist’s father, c. 1920, as a Wilberforce College student, Ohio. Finally, in the group photo on the bottom left is India (with big bow) at her sixth birthday party in 1914 on the porch of her backyard doll house.

Daddy had gone to college in Ohio, and he’s the one who told me to go to Antioch, because it was so liberal, it had Black students, even then! That was the only place I ever wanted to go.

Anyway, even though my father had this very respected uncle, his side of the family was poor, so he worked his way through college as a Pullman porter. He loved sports and all the things young Black men (with fresh images of slavery in their heads) admired in the 20’s and 30’s. Joe Louis was his hero then, and he read a lot. In this picture there are references to W. E. B. DuBois, who came to our house when I was growing up, and to Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen. Both my mother and father bought us those writers, and we grew up reading them and others. Zora Neale Hurston would come through Atlanta on her trips to gather information for her anthropological work (she was studying at Columbia with Franz Boas) and she would come to my father’s drug store. He would get a whole bunch of guys together, and after the drugstore closed, they would sit around drinking bourbon with Zora. And she would tell stories, and they would tell stories (and she would write those stories down). She came several times, and Daddy said she was wonderful.

Irene, India and Friends at Graduation depicts Irene Dobbs Jackson at twelve or thirteen in Atlanta. She was one of the five beautiful Dobbs sisters living next door to the Amos’s, including Mattiwilda Jackson, the Metropolitan Opera singer. Dr. Irene Dobbs Jackson was a Professor of French and the mother of Atlanta’s Mayor Maynard Jackson.

The young women on the porch are friends gathering after graduating from high school before going off to college. In the middle is India Amos and top left, Irene Dobbs, all eighteen.

Left to right, back row: India Ruth King, Lucile Harper, Josephine Post, Michaela Wimberly

Standing, second row: Ruth Wheeler, Josephine Davis

Seated, second row: Ruby Meade, Ruth Jackson, India Amos, India March, Cecile McCay

Emma Amos, 1988

Pictured: Ku Klux Klan, Miles, India, artist Emma and brother Larry, c. 1944, Atlanta.

"The next to last piece in Odyssey is about the KKK march I witnessed on Stone Mountain as a kid, a very sad memory, because all of a sudden it came to me that my father, who I looked up to, who was a very important person in the Black community, couldn’t protect us in that situation. Here he was nothing, had no power. The only thing that protected us was class. The redneck cop who was leading the KKK march recognized, I think, that those colored folk in the nice Packard were not folks from the ‘black bottom’ he was accustomed to pushing around. He was almost respectful.”

The series goes up to the ‘60s, with images of “Sugar Ray Robinson and the Halls of Justice flying through the air on a hopeful note with coon hounds running: there—we have that loaded word.”

Emma Amos in Lucy R. Lippard's “Falling, Floating, Landing: An Interview with Emma Amos,” Art Papers 15 (1991): 13-16

Since grade school, Emma Amos’s mother instilled the ambition that she, like her grandmother and mother before her, would go to college and have a career—a rare generational expectation at that time, and one that would shape the artist and feminist that she would become. Around 1973, Amos looked for feminist writing that addressed the lives of Black women and became a devoted reader of Black women authors throughout the 1970s and 1980s, including Alice Walker and Zora Neale Hurston, whom her father met in the 1940s. She recounted:

“I read Betty Friedan, but found her work irrelevant to me as a witness to the lives of black women. My mother told me when I was in grade school that I must expect to work. She and my father were partners in the family drugstore, while other black college educated wives worked as social workers or teachers…. I became an avid reader of black women writers. I read Zora Neale Hurston, who my father had known in the 40's. My mother was an anthropology major at Fisk University, as was Hurston, at Columbia. I remember Mama talking about women poets and she collected their works, when published. In the 70’s and 80’s I read Gwendolyn Brooks, Ntozake Shange, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Angela Davis, Maxine Gong Kingston, [and] Paule Marshall.”

Indeed, Amos’s landmark Odyssey is rooted in the rich heritage passed down by her family and that of Black women artists and writers past and present. Hurston’s autoethnography, Mules and Men (1935, reprinted in 1969) is excerpted in the first print of Odyssey, a series of ten autobiographical, hand-painted monoprints, grounding the work’s middle-class narrative in the wake of chattel slavery. In 1975, Hurston’s significance as a precedent for Black feminists was recovered through the efforts of Walker, who wrote of the generative ways that Hurston’s documentation of Black southern folklore affirmed her mother’s life as historical. Walker’s own writing is also excerpted by Amos in Odyssey, highlighting the specific matrilineal heritage of Black Southern artists and writers—like Hurston, Walker, and Amos—as well as a sense of responsibility to witness and record “centuries not only of silent bitterness and hate but also of neighborly kindness and sustaining love.”

While working on Odyssey, Amos participated in a group exhibition, Autobiography: In Her Own Image (1988), curated by fellow artist and friend Howardena Pindell, which explored selfrepresentation by women artists of color. Like Amos, Pindell began making large autobiographical works in the mid-1980s that grappled with ancestral roots, particularly the “paradox and conflict” of her multiracial background. Similarly preoccupied with ideas of legacy and memory within the Black women artist community, Amos confronted parallel issues in her conceptualization of Odyssey

regarding her maternal grandmother, Emma Holmes (Amos), who was Cherokee, Norwegian, and African. In her statement accompanying Odyssey, Amos imagines what relationships and interracial solidarities could have taken place in her lineage and more broadly in Georgia during the Trail of Tears (1830–50). Amos continued to honor the intellectual, artistic, and social support of women artists in her work of the 1990s, embodying a joyous embrace of continuity and collectivity among women that began in Odyssey

Gabriella Shypula is a curator and PhD Candidate in Art History and Criticism at Stony Brook University. Her dissertation examines New York-based women artists who explored the significance of autobiography as a site for critical resistance against dominant art historical narratives in the 1970s and 1980s. Gabriella has worked on curatorial and research projects at SFMOMA, the Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, the Baltimore Museum of Art, MoMA, the Willem de Kooning Foundation, SculptureCenter, A.I.R. Gallery, and Princeton University Art Museum.

1 Emma Amos, “Art Can Make You See In The Dark,” unpublished typescript lecture, November 10, 1995, Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI. Emma Amos papers, Archives of American Art.

2 Alice Walker, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” Ms. Magazine (March 1975): 74–79, 85–89; Alice Walker, “Saving the Life That Is Your Own: The Importance of Models in the Artist’s Life,” in In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (1976; New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1983), 13.

3 Alice Walker, “The Black Writer and the Southern Experience,” in In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (1970); New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1983), 17. Amos recorded this quote in her notebook on June 2, 1988, at the time of making Odyssey. Notebook, c. 1985–88. Amos papers, AAA. See also Emma Amos’s Odyssey artist statement, reproduced in this catalogue pp. 47-50.

4 Howardena Pindell, “Autobiography: In Her Own Image,” unpublished typescript notes. Amos papers, AAA.

5 A notebook reveals that Amos was considering histories of Native and Black Americans in the South as early as 1985, after reading recent publications on the subject. “Progressions 1985” notebook, c. 1985–87. Amos papers, AAA.

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

EMMA AMOS: CLASSICAL LEGACIES

July 10 - September 9, 2023

RYAN LEE Gallery

515 West 26th Street

New York NY 10011 212 397 0742

www.ryanleegallery.com

Member, Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA)

Essay by Michele Valerie Ronnick

Appreciation by Gabriella Shypula

Catalogue management and editing by Ethel Renia

Photography by Adam Reich, Luke Austin, and Mikhail Mishin

Design by Mikhail Mishin

Publication copyright © 2023 RYAN LEE Gallery

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023909037