CAN YOU SEE ME NOW?

Forewords

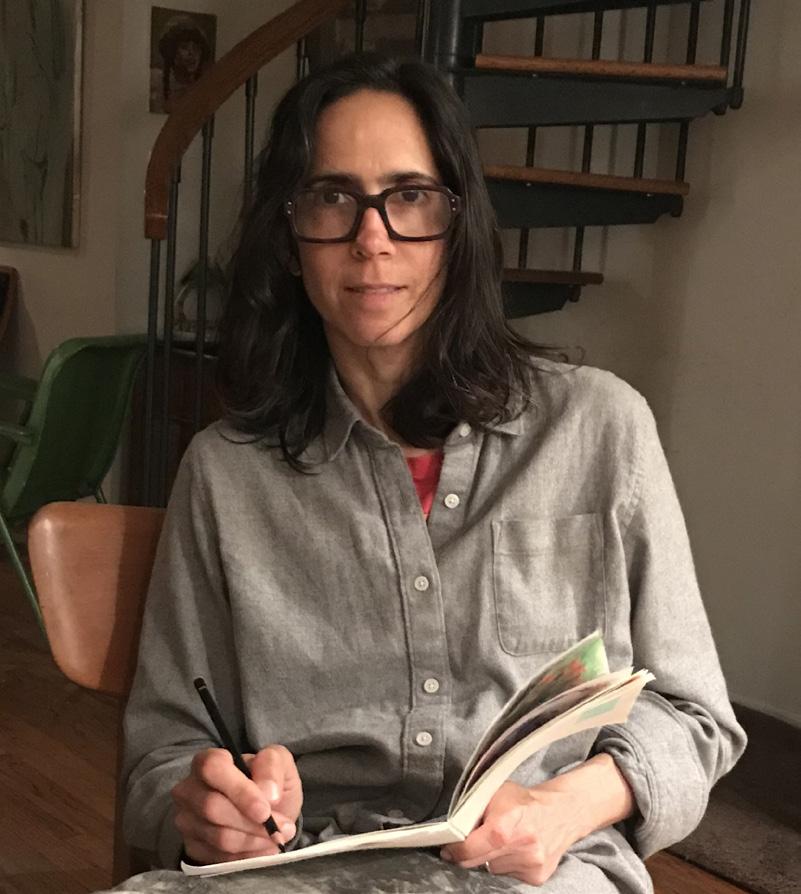

by Clarity HaynesPolitics

Plates & Artists's Reflections

by Jillian McManeminMay Stevens and Alice Stevens in Framingham, MA, 1982

Alice Stevens, a housewife, mother, and homemaker, deserves to be seen for the life that she lived. Hers was an ordinary life but full of many extraordinary moments. For her daughter May Stevens, this question of who deserves to be seen was a foundational one. By the early 1980s, she had established herself as an artist, activist, and a founding member of landmark feminist institutions including the Heresies Collective and SOHO20. It was during this time she turned to her mother, who was aging and living in a nursing home, and gave her a platform to be seen and not fall into obscurity. May bore witness to her mother in a dozen paintings celebrating her.

I have thought a lot about this series that celebrates her aging mother, painted in a scale where she cannot be denied. I think of my own mother.

The genesis of this exhibition was a reflection on May Stevens’s monumental paintings of her mother, unapologetically depicting the marks of aging with dignity, tenderness, and compassion. Why haven’t these works been seen and collected as the other series of work in her nearly six-decade career? They are equally powerful as her Big Daddy works, which denounce bigotry and patriarchy, her History paintings that lionize her feminist compatriots, as well as her poetic Sea of Words landscapes filled with poignant texts from Virginia Woolf and others. The paintings of Alice are of equal stature as her other major works, and yet—perhaps due to a societal aversion to considering aging women—these works were overlooked.

May wrote beautifully about aging in a collection of PROSEPOEMS ON AGING BODIES. Poignant, lyrical, atmospheric, the writings complement her paintings. She wrote about Bailey Doogan, a friend from the southwest, who devoted her entire practice to painting her own body. May greatly admired the courage it took to show what society shuns. She wrote about her own work:

“I WANT TO CELEBRATE THE OLD BODY, I WANT TO SHOW THE BEAUTY OF – AND THE FEAR AND DREAD IT GENERATES – THE FEMALE BODY AS IT AGES AND CHANGES, SAGS, THINS AND THICKENS. THIS TO ME IS A SACRED BODY.”

In researching this idea, I came across the work of Clarity Haynes, which led to conversations about aging women and the lack of representation in painting specifically. It has been a privilege to have such wonderful artists of various generations contribute important works that touch on the multifaceted aspects of aging. There have been very few shows devoted to this topic, and we hope this exhibition starts the conversation about creating not just visibility but a compassionate seeing of our aging population and our future selves. I want to thank all the artists in the show, who bring to life incredible subjects.

We all deserve to be seen.

~ Jeffrey LeeWhen Jeffrey Lee came to my studio, he told me he wanted work for a show about painting the aging body (or I should say, older bodies, or I should say, old bodies — there is so much delicacy around how to say this), and he asked if I was interested in participating. “1000%,” I responded. Not one hundred but one thousand percent. Because that’s how rare this is, that anyone shows any interest in paintings of aging bodies. There are plenty of depictions of bodies, these days; we’re in (some would say) a golden age of figurative painting. But the people depicted in these paintings? With very few exceptions, they are mostly young.

In fact, it’s challenging to think of painters of any age who spend their time rendering the wrinkles of flesh, the sagging of flesh, the embodiment of people who are middle-aged or older. So when I mentioned several artists I know of who do, Jeffrey invited me to co-curate the show with him. I am honored to have helped bring this cross-generational group of artists together who paint the older body in thought-provoking and loving ways.

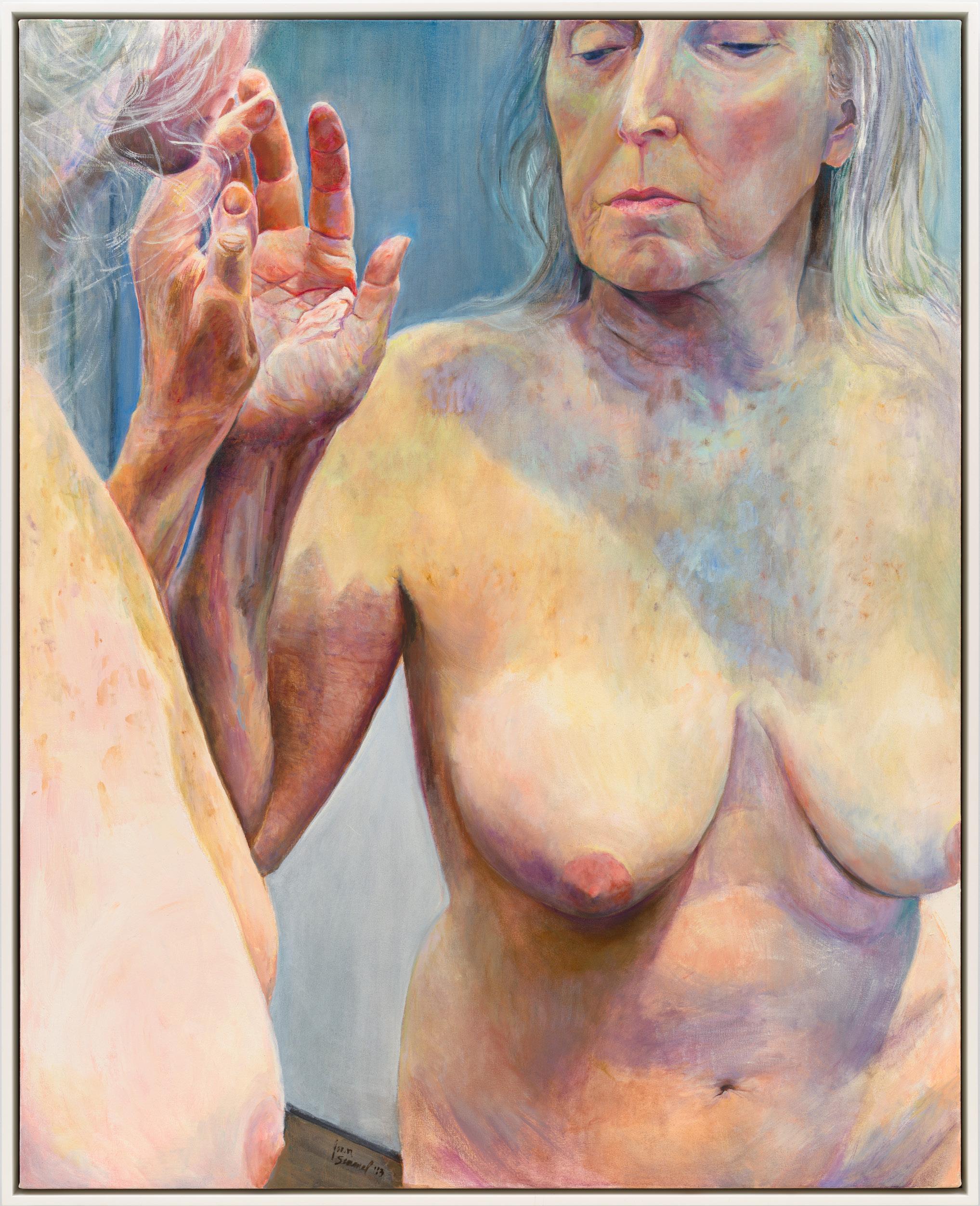

“The old(er) female body is the tomb of man’s desire. To picture the old(er) female nude is to represent the ultimate patriarchal taboo, which is the end of patriarchy.” In her excellent essay “Joan Semmel’s Body,” 1 art historian Amelia Jones cites this bold statement by Joanna Frueh. To say that the nonagenarian artist Joan Semmel’s nude self-portraits “kill” the patriarchy might sound hyperbolic, but it also has a ring of truth. And it just might help explain the general invisibility of old women in art.

As thrilled as I am to help bring this subject matter to light in this exhibition, I hope it is just a beginning. The patriarchy needs to die, along with the gender binary and all the insidious “isms” that keep the full spectrum of human beings from living fully and freely in our bodies. We need many more exhibitions that demonstrate ways of seeing and painting bodies that have lived. Bodies that are unapologetically dignified and self-possessed, creative and creating. We need art that questions what it means to be in one’s prime. The harmful double standard which values men for their ideas and experience and women primarily for their youthful beauty and reproductive labor needs to be burned down. I would posit that the subjects in this show are truly, powerfully, in their prime! And it is the failings of a market-driven art world predicated on a (cis het) male gaze that would erase them.

~ Clarity Haynes

Joan Semmel, Skin Patterns, 2013 (detail)

Joan Semmel, Skin Patterns, 2013 (detail)

While mindlessly scrolling through Instagram I saw that a new NYC-based publication posted an article on aging. It was an advice column; a 28-year-old woman wrote in fretting about getting older. The writer who answers is 35 and gripped by the terror herself—she confesses missing the number of catcalls she used to get and compares herself to her 11-year-old dog, who gets fewer pets as the years press on. She uses the popular social media age filter as evidence for a deep, widespread anxiety. The piece is common; reams of similar sentiments have been produced about the horrors of aging for women—and in the art world, it’s a known phenomenon that success is often only bestowed to women much later in their lives and careers, if at all. And what of the representations of aging?

There are endless paintings of sirens, nymphs, and maidens for millennia; and the art historical examples of the aging body are usually laced with shame and misogyny. Does rendering and viewing the aging body remind us of our mortality? Do these representations have the power to send us fleeing to compulsively distance ourselves from the real? Can You See Me Now: Painting the Aging Body at RYAN LEE Gallery curated by the artist Clarity Haynes and Jeffrey Lee gathers women-identifying artists to address the representational gap, politically and intimately.

There’s a meditative quality in Bailey Doogan’s Breasts, Age 59 . The painting appears to be a detail, but the self-portrait framing of the artist’s breasts and stomach fills the surface with delicately rendered skin illuminated by natural light. The viewer gets lost in lines, dapples, dimples, and folds. Light brings reverence to the form like a first class relic, an elevated and cared-for fragment of the body, while addressing the obvious taboo of fetishizing one’s breasts at age 59. The soft, small painting is defiant. I love how it invites you to stare.

This mood is echoed in Joan Semmel’s Skin Patterns . Semmel’s frame zooms out to show the artist confronting herself in a mirror. We are invited to look at how she looks at herself, a play on the mirror selfie. Her skin is rendered as delicate, highly responsive to light, touch, and texture. Semmel’s work centers on the act of looking. She touches the mirror, embodying the

slippery distance between representation and self, and the desire to close it. Beverly McIver’s self-portrait Finding Comfort addresses this distance as well. The artist paints herself with a doll. A majority of dolls are created in the likeness of white people, and the doll McIver holds is black—self-comfort in representation.

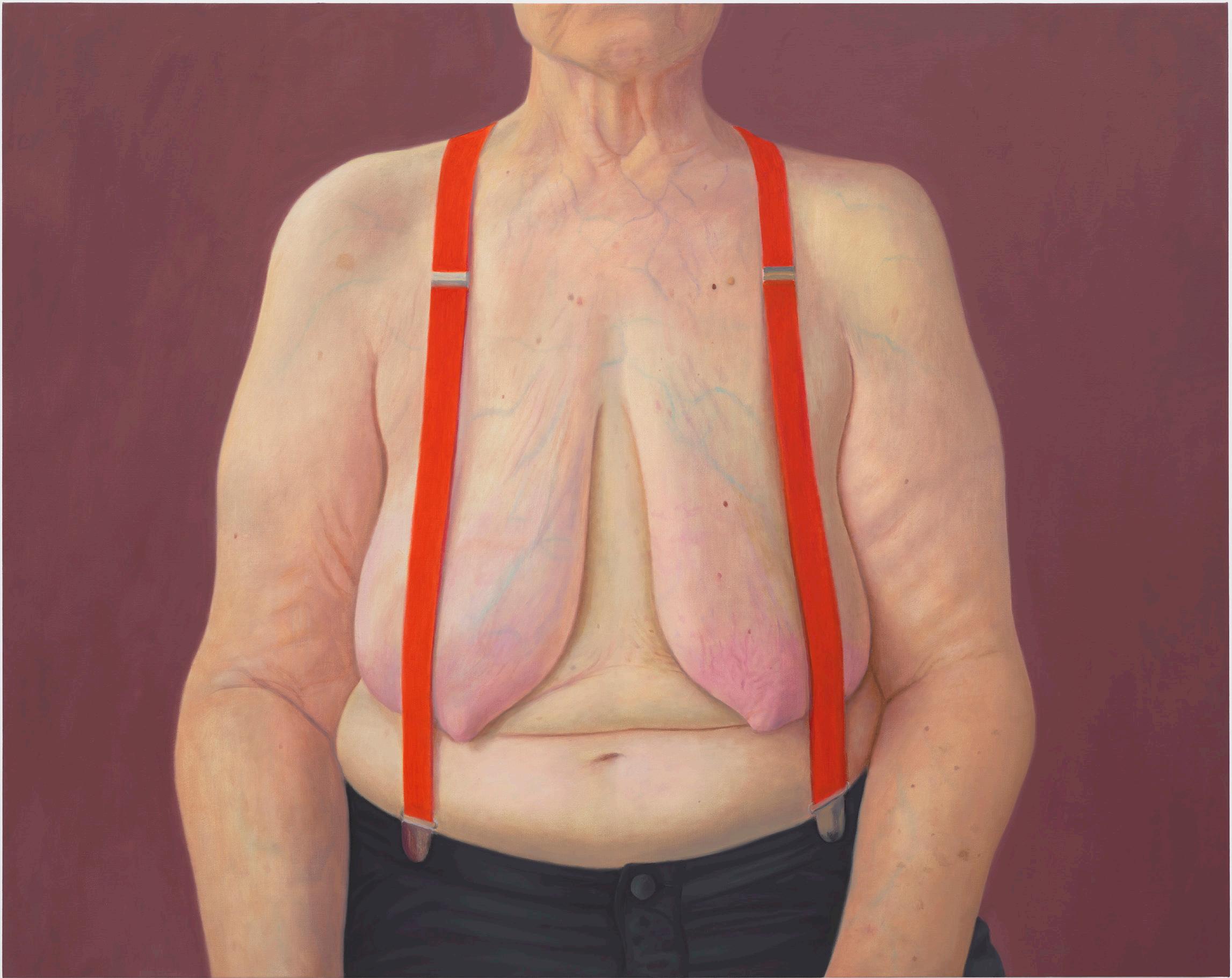

Angela Dufresne paints the artist Sheila Pepe in a red atmospheric landscape wearing a bright red shirt, either emerging or receding. The tension of this sightline mirrors the larger themes of the exhibition—what’s being done and undone in political spheres and in the art world concerning equality. Dufresne’s painting focuses on rupturing the hierarchies between creator and subject, refocusing on lesbian herstory and our vital, interwoven communities. Suspenders, which Sheila wears, are a well-known dyke fashion signifier; they also appear in Clarity Haynes’s portrait of Brenda Goodman.

Haynes has created hundreds of torso portraits of feminist and queer sitters over the past twenty five-plus years. Her aesthetic of slow looking is celebratory, liberating, and rooted deeply in the real. Isn’t this always the critique of radical spaces and visions of alternative communities, that they’re not rooted in the real? This non-utopian radical space is, however, fleshy—an archive and present within reach.

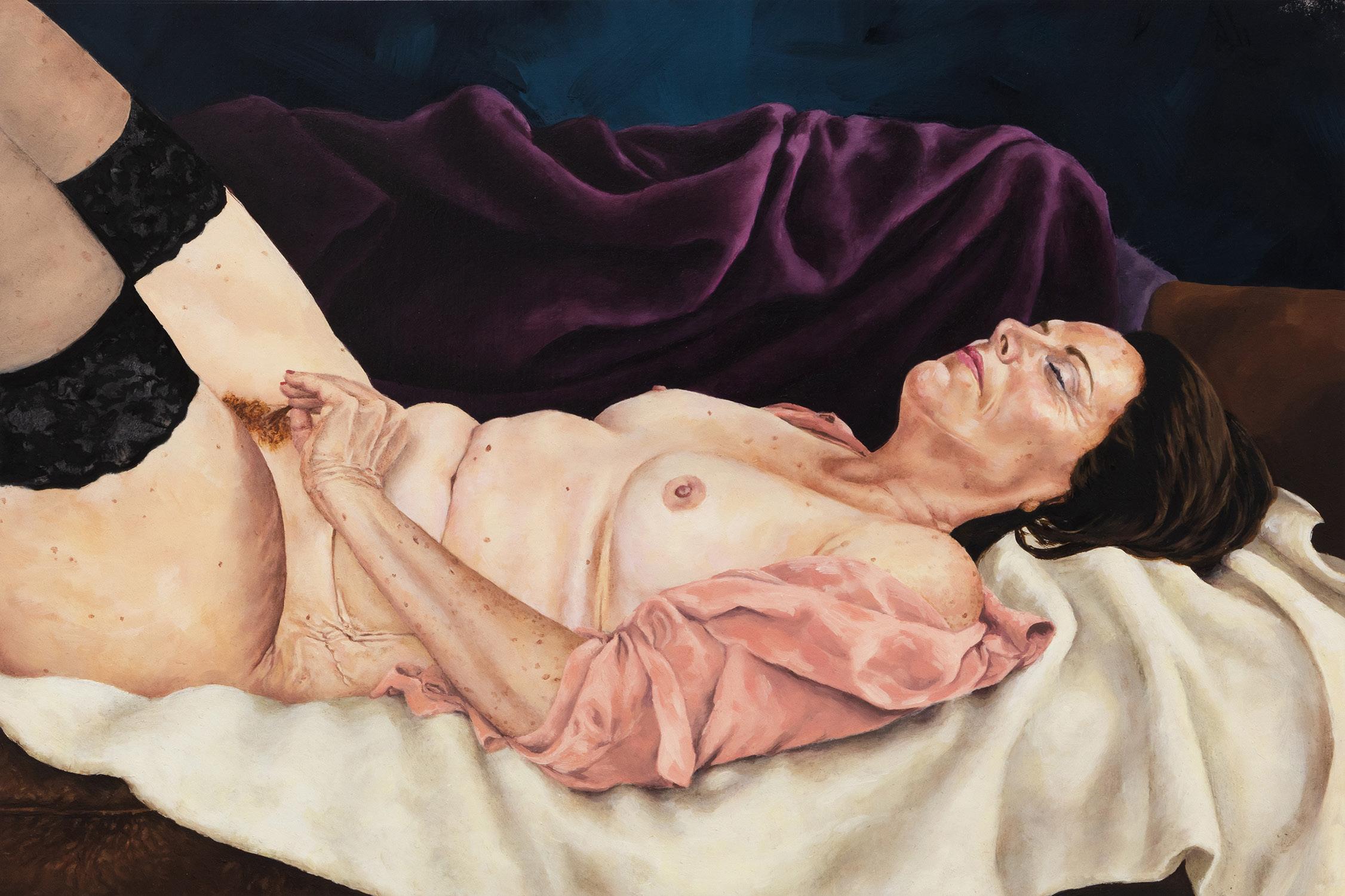

The real is in the present, and we enact the past in the present. We either repeat it or find a way to confront it. Brenda Goodman’s painting Double Portrait is a full-frontal nude of her and her partner. There’s a somber quality to this work; they’re posed in a gray studio with stoic looks on their faces. The tension between visibility and invisibility is critical, it points to the harsh dichotomy that both older women and lesbians experience— that Goodman doesn’t shy away from confronting. Samantha Nye cleverly plays with a similar tension. Her paintings feature cover girls reposed in their 1980s centerfolds. Tobi as pg. 97 - Entertainment for Men depicts a woman in an odalisquelike recline, her eyes closed, pulling her own pubic hair. Nye disrupts archetypes to bring more complexity, humanity, and reality to sexuality and power. We can view these paintings as reclamation, satire, a play on a cautionary tale regarding sex

work and the frequent comment, “you can’t do this forever!”. The paintings are an invitation to confront our younger and older selves at once. Most importantly, we want to know who these women are , what they think and know about sex, objectification, and themselves.

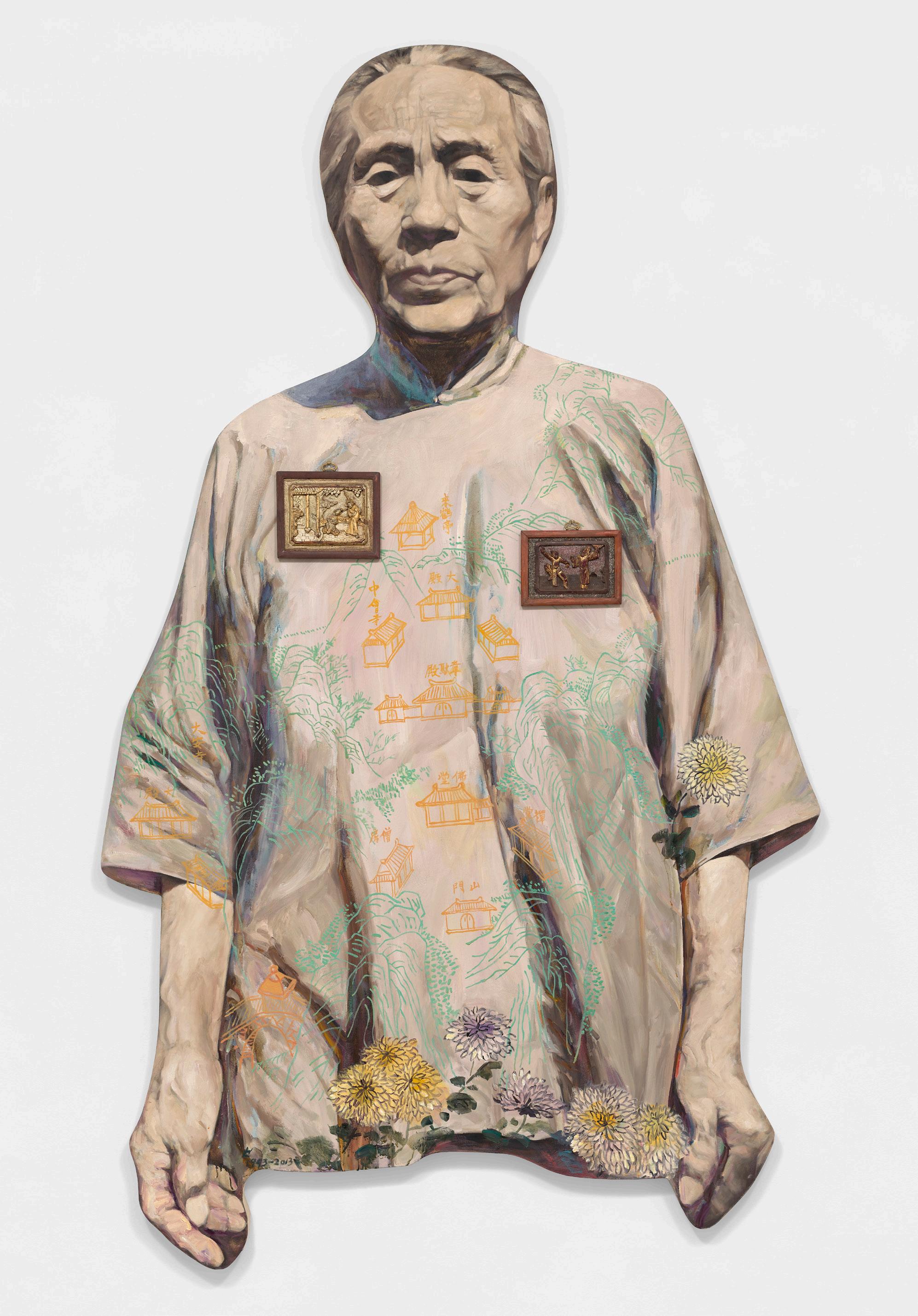

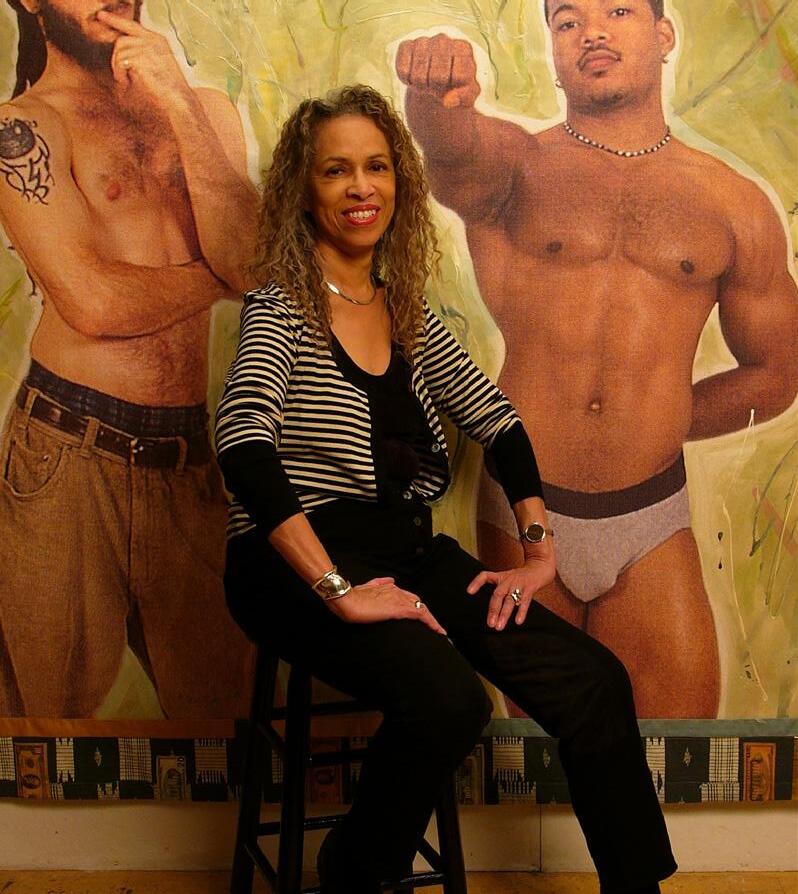

We have the whore and we have the mother: Emma Amos’ My Mother was the Greatest Dancer depicts her mother balancing on one leg, reminiscent of goddess iconography. The use of the past tense in the title transforms the painting into a commemorative artwork, while the intensity of Amos’s palette defies the norms of funereal commemorations of the West with bold African fabric borders. May Stevens’s A Life depicts her elderly mother, Alice Dick Stevens; this years-long practice between 1983-90 of producing large-scale paintings of her mother serves as a reminder of the inherently political act of women aging. The artist is trying to figure herself out via rendering her mother, in a practice of continuously looking at the matrilineal line. Hung Liu, who paints her grandmother as a strong figure standing on her own, engages in Grandma in this requisite practice as well. These works tap into the fear and embrace of becoming more like our mothers as we age.

What happens in these works is beyond representation, it’s about enactment. I imagine Brenda sitting for Clarity, I imagine the conversations that went into the creation of Sheila’s portrait by Angela, the stories of Samantha’s subjects, the psychological and emotional weight and softness of painting one’s mother. The layering of personal connections in the works becomes a body itself. Mala Iqbal’s portrait To Ponder is an invented amalgamation of women, yet the artist uses her own hands as a model.

So often the stigma of aging people, especially women, is that they’re functionless. That’s the horror that they produce—a void, an object taking up space past its use. Isn’t this what the fascists say about art? That it’s useless, ugly, horrific? Art asserts its own functionlessness as a means of revolutionary potential. I think of Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia , the gleaming bodies performing in step, a fascist monument that continuously replenishes itself with new male flesh. Would physical decline be as frightening

if our world was outfitted to accommodate difference? How we regard the aging body is directly linked to disability politics, fascist ideology, constructed space, and community.

The works in the exhibition and discourses on aging are vital in their political potentials and intimacies. And then there is the displaying of the work, the act of gathering. Some of the artists in Can You See Me Now were instrumental in the groundbreaking collectives Spiral, Heresies, and the Guerrilla Girls. Embodied experience is the focal point of these paintings, a salve against the highly consumable figurative painting that explodes the market, enacting a capitalist, shallow politic. Can You See Me Now is about art and beholding beyond patriarchal values. It’s an art that demands attention.

My Mother was the Greatest Dancer is a celebration of mature Black womanhood, as depicted by Emma Amos at the age of 79. An artist known for pushing technical and thematic boundaries, Amos unabashedly made art that reflected the experiences and triumphs of Black women, even when such art elicited little to no response from her male peers and critics. Reminding the viewer, the critic, and the art world at large of the undeniably important presence of the Black female body, Amos frequently used images of her family in her celebration of Black femininity. In this tender celebration of India Amos, painted 28 years after she’d passed away, Amos extends to her mother—and by proxy, Black women—a thundering applause.

My Mother was the Greatest Dancer, 2007 | Acrylic on canvas with African fabric borders and fabric collage | 59 x 42 1/4 inches (149.9 x 107.3 cm)

Our bodies are full stories. They are detailed maps of our experiences. This corporeal topography of our hair patterns, veins, scars, calluses, wrinkles and flesh (both smooth and crenulated) speak of a life lived.

— Bailey Doogan, 2005Breasts (Age 59), 2001 | Oil on linen | 12 x 12 inches (30.5 x 30.5 cm)

Last summer I attended a crone-ing ritual. I am a crone, and I welcome the term. There were many amazing women at the event who joyfully accepted the transition out of youth, out of fertility—the two seemingly universal qualifiers of female value, into the crone stage of their lives—i.e., after 50. All welcomed the passage into ‘older’ age as a badge of honor, not as erasure or as the matrix for contempt and uselessness so many cultures associate with aged women. We all know capitalism and patriarchy stay strong when woman are only perceivable as either fetish and then hag. I say, fuck that! Embrace the hag, love the wisdom and courage of women as they grow old and wiley, celebrate them over the commodities we are apt to become in the hands of patriarchal forces.

— Angela Dufresne, 2023

In this body of work—Self Portraits 2003-2007—my desire is to address concerns I’m facing as a 63 year old woman and artist.

Through the process of painting myself, my intent is to extend the parameters of my specific personal issues to reveal and comment on basic universal emotions and conditions.

I want to remove the veils between myself and the viewer, and communicate the palpability of needs met, of needs unmet, of needs never met, of rage, of fear, of vulnerability, of aging, and finally of mortality.

My work is about reality, not irony.

— Brenda Goodman, 2006Double Portrait, 2006 | Oil on wood | 64 x 60 inches (162.6 x 152.4 cm)

This painting is of my dear friend the painter Brenda Goodman, who has recently turned 80, and whose work I have admired for years. It is a real honor to paint the body of a painter who has painted her own body, to offer my own perspective on this artist whose self-portraits are so iconic and powerful. Brenda knew exactly how she wanted to be portrayed in this portrait: with red suspenders. There are photographs of her going way back into the 80s in which she is wearing red suspenders. (There is sometimes a jaunty red bandana tied around her neck, too.) Brenda is a lesbian, a butch, a dyke. Brenda defines herself; she is anything but the stereotype of what an old woman is.

THIS is the essence of The Breast/Chest Portrait Project, which portrays the truth of my life, my feminist and LGBTQIA+ community, my friends, and shows what so often is not seen in the larger culture—or if it is, is often misunderstood. This painting of Brenda is one of many torso portraits I’ve made over more than 25 years. These paintings playfully and unapologetically honor our dignity, vibrancy and power.

— Clarity Haynes, 2023

In my favorite mystery novels written by Dorothy Sayers in the 1920s-30s, the protagonist (a man) is considered practically ancient at 40 and the women are old at 30. My mother, Inge Grundke-Iqbal, died at 75. She had not “retired” in any sense of the word—she was still a working research scientist and an active, vital, participant in the stuff of life—so it seemed very early to lose her. Galleries have always chased after the young, and younger. It made me mad in my thirties. Now well into “middle age” myself, it doesn’t seem worth bothering about.

The person in this painting has white hair and wrinkles. The big thoughtful eyes look slightly to the side and behind you. You are not the focus of this dreamer’s thoughts.

— Mala Iqbal, 2023

My grandparents, Dayi, and mom live in me, with me. They have never left.

Mom, Dayi, LaoLao (grandma) and Lao Ye (grandpa) miss me so much. I guess we will re-unite soon.

Grandma used the clothes and burned out coal ashes to make woman’s menstrual belt. MaMa used toilet paper for menstrual use. Women’s journey: grow up, mature, suffering. Three obediences, and four virtues。

Grandma tied the clothes around her waist under her outside clothes to hide, walked a long way to trade for food.

— Hung Liu's diary entries, 2021

The paintings hold up a mirror to whoever the viewer is. If you are coming to the painting and you look at it and you can't go beyond the surface, or the color, the lusciousness of the paint, that's all you want to see from the painting, then you can stop there. But if you want to go deeper, conceptually speaking— being uncomfortable about change and differences, growing, just being human and flawed—you can get that too.

— Beverly McIver in conversation with Chadd Scott, 2023

Entertainment For Men is a series of small oil paintings that reimagine the covers, inner pages, and centerfolds of Playboy Magazines from 1980-1993. In this case, the subjects are women from my immediate and extended family, ages 60-91, including my mother, grandmother, and their tight circles of life-long friends. Each woman is invited to sort through my collection of vintage magazines and asked to choose a scene to reenact. I ask them to consider the seduction tactics from these photographs that appeal to them, intimidate them, turn them on, make them uncomfortable, disappoint or inspire them. Viewing these vintage Playboys as a symbol of the sexual consciousness of my adolescence, I am examining the literal and conceptual models of sexuality that influenced my own Matriach and the generations of women from whom I inherited notions of gender, sexuality, and methods of seduction.

— Samantha Nye, 2023

Irene as Cover, June 1986 -Entertainment for Me, 2006 Oil on paper

11 x 8 1/2 inches (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

Entertainment for Men - Mommom as July 1982, 2012 Oil on paper

11 x 8 1/2 inches (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

Barbara as Cover, September 1988 - Entertainment for Men, 2012 Oil on paper

11 x 8 1/2 inches (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

In my studio, I walk the tightrope between vulnerability and power; the vulnerability of the flesh and the power of my art to enable it. My work utilizes the body as symbolic and iconic as well as intimate and sensually communicative—both personal and political in its functions. My interest in the flesh lies in its dichotomies: its formal and conceptual implications aesthetically and its past centrality to the definition of women’s role in the culture. . .

My own image has been a convenient instrument with which to project my concerns. However, I never thought of the work as self-portraiture and have always been surprised to see it received as such. . . I have approached the flesh as primary, suspended in unidentifiable baths of color. The unclothed body, alone, unadorned, classless, is as the baby newly born, defenseless, except for its cry. The specificity of a non-idealized body that ages over the years raises the specter of mortality, that everpresent and timeless reality.

— Joan Semmel, artist statement for A Balancing Act at Alexander Gray Associates, 2021

MY MOTHER SITS AT A WINDOW WATCHING THE FIELD. WHEN I COME AFTER SIX MONTHS, A YEAR, SHE WAVES. MOVING FROM CHAIR TO BED TO TABLE SHE OPENS THE DOOR TO THE FIELD, WAITS TO RECEIVE WORDS OF PRAISE AND AFFECTION. THE DAYS OF NO FIGURE CROSSING THE FIELD HAVE MOVED TO THIS MOMENT. WE ARE TOGETHER. WE DRIVE OFF. SHE HAS NOTHING TO SAY. SHE IS HUMMING.

May Stevens, June 1976, NYC

Emma Amos was a dynamic painter and masterful colorist whose commitment to interrogating the art-historical status quo yielded a body of vibrant and intellectually rigorous work. Influenced by modern Western European art, Abstract Expressionism, the Civil Rights Movement, and feminism, Amos was drawn to exploring the politics of culture and issues of racism, sexism and ethnocentrism in her art. Amos was the youngest and only woman member of Spiral, the historic African American collective founded in 1963, as well as a member of the feminist collective and publication Heresies, established in the 1980s.

Bailey ‘Peggy’ Doogan was an American multidisciplinary artist best known for her large-scale feminist paintings and drawings focusing on the aging body. Born and raised in Philadelphia, PA, she earned a BFA from Moore College of Art and an MA in animated film from the University of California, Los Angeles. Her paintings and drawings were showcased in various solo and group exhibitions across the United States, including notable venues such as The New Museum of Contemporary Art and the Alternative Museum in New York. Her acclaimed animated film, SCREW, A Technical Love Poem, received numerous awards and was featured in festivals around the world. Doogan lived in Tucson, AZ, and Nova Scotia, Canada until her death in 2022.

Angela Dufresne explores the experience of American womanhood through painting, drawing, printmaking, performance, and community building. A contemporary lesbian painter committed to championing non-hierarchical narratives, Dufresne references other artists and films in her paintings, drawing connections between history and her own personal experiences and associations as a queer woman. She sees painting as a co-creative process, often prompting her subjects to interact with the painting process through dictation of the backdrop and deciding when the work is finished.

Brenda Goodman has relentlessly explored the physical and psychological limits of abstraction and figuration throughout her illustrious career. Regarded as a “painter’s painter” for her inventive handling of paint, Goodman’s paintings range from thick impasto to thin veils of color, creating deep, interior spaces of personal confrontation and reflection. Between 1994 and 2007, Goodman created a series of ground-breaking self-portraits which critic John Yau called “one of the most powerful and disturbing achievements of portraiture in modern art.” The series combines her expressionist tendencies with figuration to reveal the innate vulnerability and power within one’s own mortality.

Clarity Haynes is known for her longstanding explorations of the torso as a site for painted portraiture. Works in her Breast/Chest Portrait Project, painted from life and usually monumental in scale, have focused on themes of healing, trauma, and self-determination. While the torsos primarily tell the intimate stories of other people, her still life paintings of personal altars are self-portraits of sorts, made up of mementos and power objects collected by the artist over decades. Feminist and queer craft practices are often honored in Haynes’s work; bright colors, lively compositions and multiple narratives conjoin in her depictions of both bodies and altars.

Mala Iqbal was born in the Bronx in 1973 and grew up in a household where three cultures and four languages intersected. She has had solo exhibitions at Soloway Gallery in Brooklyn; Ulterior Gallery, Bellwether Gallery, and PPOW in New York; Taylor University in Upland, Indiana; Twelve Gates Arts in Philadelphia; and Richard Heller Gallery in Los Angeles. Her series of collaborative paintings, made with Angela Dufresne, was shown in October 2021 at the Richard and Dolly Maass Gallery, SUNY Purchase, and will be exhibited at LSU in Baton Rouge in Fall 2023. Her work has been exhibited in group shows throughout the United States as well as in Australia, China, Europe, and India. Mala Iqbal lives and works in New York City.

Hung Liu grew up in China under Mao’s regime, where her artmaking was initially constrained to Socialist Realist and mural painting. In 1984, Liu left China to attend graduate school at the University of California, San Diego, where she began implementing fluid materiality and surrealist visual strategies in her art. Her later works often dissolve historical Chinese photographs of overlooked subjects—prostitutes, refugees, street performers, soldiers, laborers, and prisoners—suggesting the passage of memory into history.

Beverly McIver is widely acknowledged as a significant presence in contemporary American painting, charting new directions as an African American woman artist committed to examining racial, gender, social and occupational identity through self-portraits and images of her family.

Samantha Nye is a painter, video, and installation artist currently living in Philadelphia. Her work reframes seduction through reenactments of 1960s pop culture. Her paintings, videos, and installations highlight aging bodies, celebrate queer kinship, and facilitate an intergenerational dialogue about sexuality and pleasure. Samantha is a 2023 Guggenheim Fellow. She had a solo booth of paintings at the Armory Fair in 2023. Her work is in the collections of the Arnhem Museum in the Netherlands and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. She has had several international large-scale video installations and paintings in shows in London, Korea, and several cities in The Netherlands and New York City.

Joan Semmel began her painting career in the 1960s while living in Madrid as an Abstract Expressionist, exhibiting in Spain and South America. Returning to New York in 1970, she moved to figuration in response to pornography and concerns around representation of women in culture. Since the late-1980s, Semmel has meditated on the aging female physique. Recent paintings continue the artist’s exploration of self-portraiture and female identity, representing the artist’s body doubled, fragmented, and in-motion. Dissolving the space between artist and model, viewer and subject, the paintings are notable for their celebration of color and flesh.

May Stevens was a painter and printmaker whose work was shaped by the various political and social movements she participated in. A founding member of Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics and the Guerilla Girls, Stevens is known for her politically charged paintings that challenge the patriarchal power dynamics of American society. While her political commitment drove her earlier work, her later works tend to be more lyrical, her Ordinary/Extraordinary series highlighting the simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary potential of women through pictures of her mother, Alice Stevens, and the Marxist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg.

Applewhite, Ashton. This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism. New York, NY: Celadon Books, 2016.

Aronson, Louise. Elderhood: Redefining aging, transforming medicine, reimagining life. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021.

Beam, Cris. “There’s No Road Map for an Aging Lesbian.” The New York Times, April 8, 2023.

Blackie, Sharon. Hagitude: Reimagining the second half of life. Novato, CA: New World Library, 2022.

Bruder, Jessica. Nomadland: Surviving America in the twenty-first century. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017.

Carrington, Leonora. The Hearing Trumpet. Paris, France: Flammarion, 1974.

Carter, Angela. Wise Children. London, UK: Chatto & Windus, 1991.

Coleman, Chloe. “Aging Can Be Hard for Those in the Trans Community.” The Washington Post, October 27, 2018.

“Coming of Age.” Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Arts & Politics 6, no. 3 (28) (January 1, 1988).

Cruikshank, Margaret. Learning to Be Old: Gender, Culture, and Aging. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003.

Emre, Merve. "What Susan Sontag Wanted for Women.” The New Yorker, May 23, 2023.

Ephron, Nora. I Remember Nothing and Other Reflections. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

Gendron, Tracey. Ageism unmasked: Exploring age bias and how to end it. Lebanon, NH: Steerforth Press, 2022.

Gullette, Margaret Morganroth. Agewise: Fighting the New Ageism in America. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Hinchliff, Sharron, Merryn Gott, and Christine Ingleton. “Sex,

Menopause and Social Context.” Journal of Health Psychology 15, no. 5 (2010): 724–33.

Holstein, Martha. “Productive Aging: A Feminist Critique.” Productive Aging: A Feminist Critique 4, no. 3–4 (1993): 17–34. Holstein, Martha. Women in Late Life: Critical Perspectives on Gender and Age (Diversity and Aging). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

Jansson, Tove. The Summer Book. Stockholm, Sweden: Bonnier, 1972.

Juhasz, Suzanna. “Feminism, Aging and Discovering Senior Space.” Ms Magazine, November 19, 2019.

Leardi, Jeanette. “The Aging Equivalent of High Heels.” Jeanette Leardi | social gerontologist | public speaker, April 30, 2020. https:// www.jeanetteleardi.com/post/the-aging-equivalent-of-highheels.

Levy, Becca. Breaking the Age Code: How Your Beliefs About Aging Determine How Long and Well You Live. New York, NY: William Morrow, 2023.

Macdonald, Barbara, and Cynthia Rich. Look Me in the Eye: Old Women, Aging and Ageism. San Francisco, CA: Spinsters Ink Books, 1983.

Marshall, Leni. “Aging: A Feminist Issue.” NWSA Journal 18, no. 1 (Spring 2006): vii–xiii.

Medetti, Stefania. “The Age Buster.” THE AGE BUSTER. Accessed August 3, 2023. https://www.theagebuster.com/

Moshfegh, Ottessa. Death in Her Hands. New York, NY: Penguin Press, 2020.

Peasall, Marilyn. The Other Within Us: Feminist Explorations of Women and Aging. New York, NY: Routledge, 2019.

Porter, Nancy. “The Art of Aging: A Review Essay.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 17, no. 1/2 (1989): 97–108.

Poo, Ai-jen, and Ariane Conrad. The Age of Dignity: Preparing for the Elder Boom in a Changing America. New York, NY: The New Press, 2016.

Rosenfeld, Dana. “Identity Work among Lesbian and Gay Elderly.” Journal of Aging Studies 13, no. 2 (Summer 1999): 121–44.

Sapienza, Goliarda. The Art of Joy. Turin, Italy: Giulio Einaudi s.p.a., 2008.

Sargeant, Malcolm. Age discrimination and diversity: Multiple discrimination from an age perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Semmel, Joan, Jodi Throckmorton, and Amelia Jones. Joan Semmel: Skin in the Game. Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2021.

Sontag, Sunsan. “The Double Standard of Aging.” The Saturday Review, September 23, 1972.

Spark, Muriel. The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. London: Macmillan, 1961.

Steinhauer, Jillian. “Old Women.” The Believer, June 1, 2021.

Woolf, Virginia. Mrs. Dalloway. London, UK: Hogarth Press, 1925.

Painting the Aging Body

September 14 - October 21, 2023

RYAN LEE Gallery

515 West 26th Street

New York NY 10011

212 397 0742

www.ryanleegallery.com

Co-curated by Jeffrey Lee and Clarity Haynes

Essay by Jillian McManemin

Catalogue management & editing by Ethel Renia

Photography credits:

© Emma Amos | © Bailey Doogan. Private Collection, NC; Courtesy of the estate of the artist. | © Angela Dufresne, Courtesy of Yossi Milo, New York. | © Brenda Goodman; Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co, New York. | © Clarity Haynes; Courtesy of the artist and New Discretions, New York. | © Mala Iqbal; Courtesy of the artist. | © Hung Liu Estate/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York. | © Beverly McIver; Photo by Ben Alper. Courtesy of the artist. | © Samantha Nye. Collection of Lisa Ziemer; Courtesy of the artist. | © 2023 Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York. | © May Stevens

Publication copyright © 2023 RYAN LEE Gallery

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023915165