at first glance, the ten new watercolors by andrew raftery act like windows: the viewer peers into a living room, a bedroom, a study as a passer by would glance inside someone’s home. The resulting scene is a remarkably intimate composition—remarkable because the stars of the show are not people but objects, and yet, in their carefully handled rendering, the artist’s affection for them shines through. The scenes depicted in Raftery’s new works are set in no ordinary homes. Indeed, the houses and museums that Raftery visited to bring his vision to life are grand structures that boast ties to an older, storied chapter of American history. The interiors that Raftery found and visually transcribed for us are lavish, ornate rooms replete with antiques, handmade furniture and mahogany wood. They seem like they come from another time, and indeed they are designed to look that way. In his works, however, Raftery sprinkles details of contemporary life—a dog wagging its tail, a lady wearing rubber sandals, a student riding a bike to class down the leafy streets of Providence s College ill neighborhood firmly rooting each watercolor in the artist’s here and now. The leading ladies of each watercolor are the 18th and 19th century wallpapers which adorn the walls of each room that Raftery brings us to: these large, rare, and precious works are the focal point of Raftery’s gaze, and the subject of his work. The wallpapers, exquisitely detailed in person as well as in Raftery’s painstaking renderings, represent some of the most ambitious and impressive accomplishments in the history of woodcuts, as well as the pinnacle of early global trade. In his careful, loving depiction, Raftery invites us to join in their exaltation, and, as we look and think about them more deeply—question them.

Why would such objects of beauty need to be interrogated? It’s a good question. For centuries, these wallpapers, conceived and produced in 18th century China and 19th century France, have been admired for their ornamental powers. For a long time, these hand-painted murals and monumental prints, installed in homes in Europe and later, the nited States, e isted as little more than collectible items, class signifiers, and lu ury goods. Their cultural significance was either not fully considered or dismissed as unproblematic. Today, with our updated 21st century moral values, we look at these wallpapers and see the evidence of 18th and 19th century worldviews that make us uncomfortable. The epic narrative wallpapers that Raftery forces us to consider in his watercolors re ect realities that e ist beyond their aesthetic and technical value: installed in America at the apex of its power and produced and popularized when Europe was dominating the world, the wallpapers are the physical manifestations of cultural domination at everyone else’s expense. Their colonial subject matter (sometimes depicting Indian women as exotic, sensual dancers, their men as agile pre-industrial hunters, for example), the history of how they got where they are, how they were preserved and upheld in lofty homes and museums in Rhode

Island and Delaware, belies a history that we would rather gloss over, sweep under a rug, forget. Whether this cultural amnesia would manifest as a categoric denial of any wrongdoing or the removal of the papers from view, Raftery’s watercolors, which uietly weigh the wallpapers aws and strengths, suggest neither is the correct approach. In his tenderly rendered, intimate portraits of the wallpapers in their contemporary homes, Raftery pushes the limits of his own work, and trains our eye and his to the beautiful, terrible evidence of our collective past so that we may do the hard work of reckoning and appreciating the unavoidable existence of these wallpapers in public and private spaces.

Raftery’s engagement with wallpapers began in earnest in 2019, when he completed his own set of handmade wallpapers depicting the four annual seasons, which he installed in his home in Providence. As professor of printmaking at Rhode Island School of Design, he has always found the technical complexities of early wallpapers to be of interest. His previous projects Suit Shopping (2002) and Autobiography of a Garden in Twelve Engraved Plates (2008-2016) experimented with the use of the seemingly archaic mediums of copperplate engraving and ceramic transfer to express a contemporary condition, thus playing with time and style—all that to say, his fascination for wallpapers in 2019 and today continues a demonstrated interest in marrying ancient art-making processes with contemporary subject matter. His current project began as research to understand the technical and art historical complexities of the wallpapers that fascinated him. As he delved deeper into this subject, he found them rife with delicate socio-historical, political nuances that needed to be seriously considered: what does it mean to have these wallpapers today? What does it mean to look at them when their content, while beautifully rendered and art historically important, sometimes carries vile insinuations (and, sometimes, outright declarations) of Western racial and cultural supremacy? How did they get here? How did we get here?

When it comes to the careful reconsideration of the cultural value of antique wallpapers, Raftery is not acting alone. Throughout his ten watercolors, he studies six wallpapers: two were made in 18th and 19th century China, four were made in 19th century France. Of the French-made wallpapers is Les Vues d’Amérique du Nord (1834). In recent years, institutions holding impressions of this wallpaper have themselves reconsidered its role in their collections. For Raftery’s neighboring Brown University, the subject of what to do with its impression of Les Vues d’Amérique du Nord—this grand old French wallpaper depicting what seems today as a fictitious vision of a glorious, industrious and unracialized America—came about a few years ago. In 2019, graduate students petitioned to have it removed from its current home in the John Nicholas Brown Center for Public Humanities in the historic Nightingale-Brown House. In response to the outcry, the university established a two-year residency called Les Vues d’Amérique du Nord: Artists Respond, and invited local Rhode Islandbased artists to create site specific artworks responding to the wallpaper. Clearly, the question of how to consider and what to do with the historic wallpapers Raftery studies is very much a part of the zeitgeist.

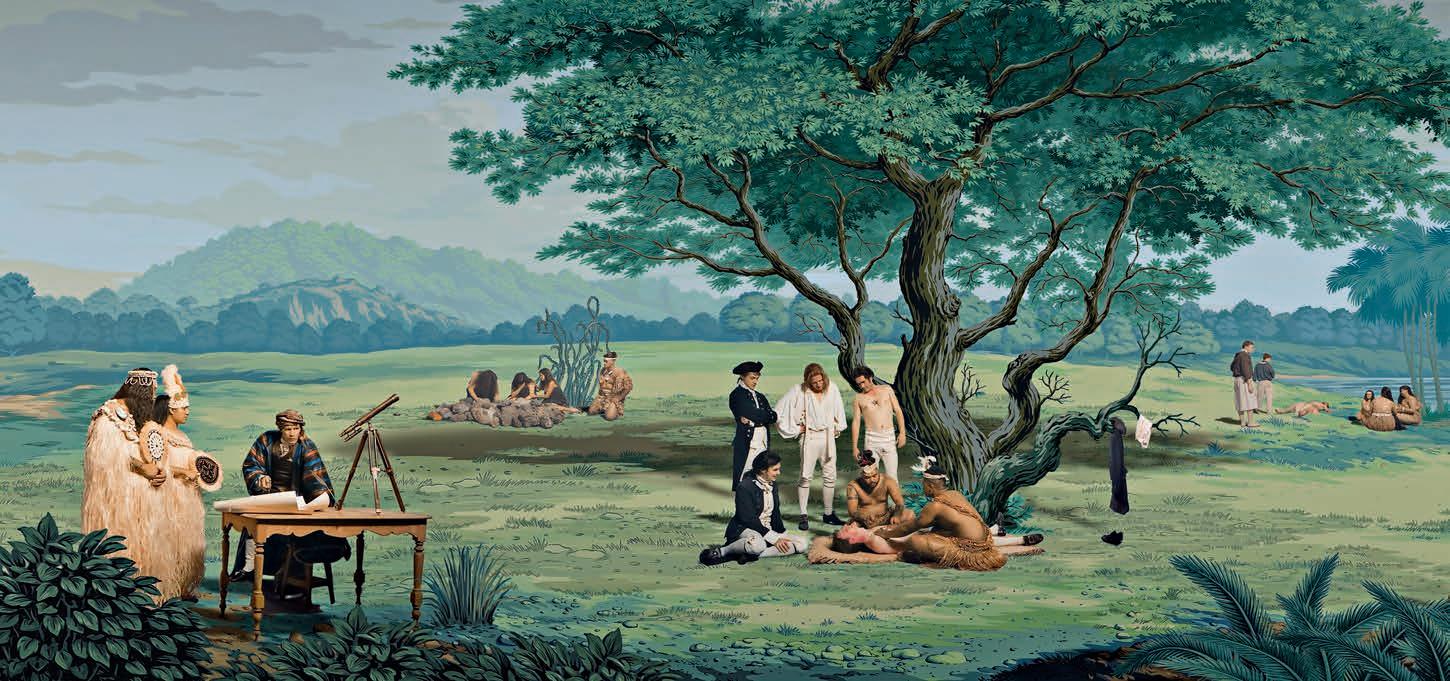

Elsewhere on Brown University’s campus, and a stone’s throw away from where Raftery teaches at risd , the David Winton Bell Gallery presented in 2022 Lisa Reihana’s in Pursuit of Venus [infected] (2015-17). This work is an immersive video installation delving into the legacy of scenic 19th century wallpapers as they portray urope s colonial e panse into the Pacific. moving interpretation of the narrative wallpaper entitled Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique (1804-05), Reihana’s rebuttal and interpretation of the two-century old wallpaper animates the indigenous people originally depicted as living simply in bucolic harmony in an imagined Tahitian landscape. Enlivened with performances by real people, Reihana’s video represents indigenous people from New Zealand and beyond, rooting them into real cultures and peoples rather than nameless, exoticized, savage “others.” In a 2015 interview, Reihana remarked, “Les Sauvages claimed to represent indigenous peoples, but like many things, it is a mirror of its time…I wanted to re-animate the wallpaper to present real Pacific peoples engaged in their own ceremonies here we are...living, breathing and beautiful.” 1

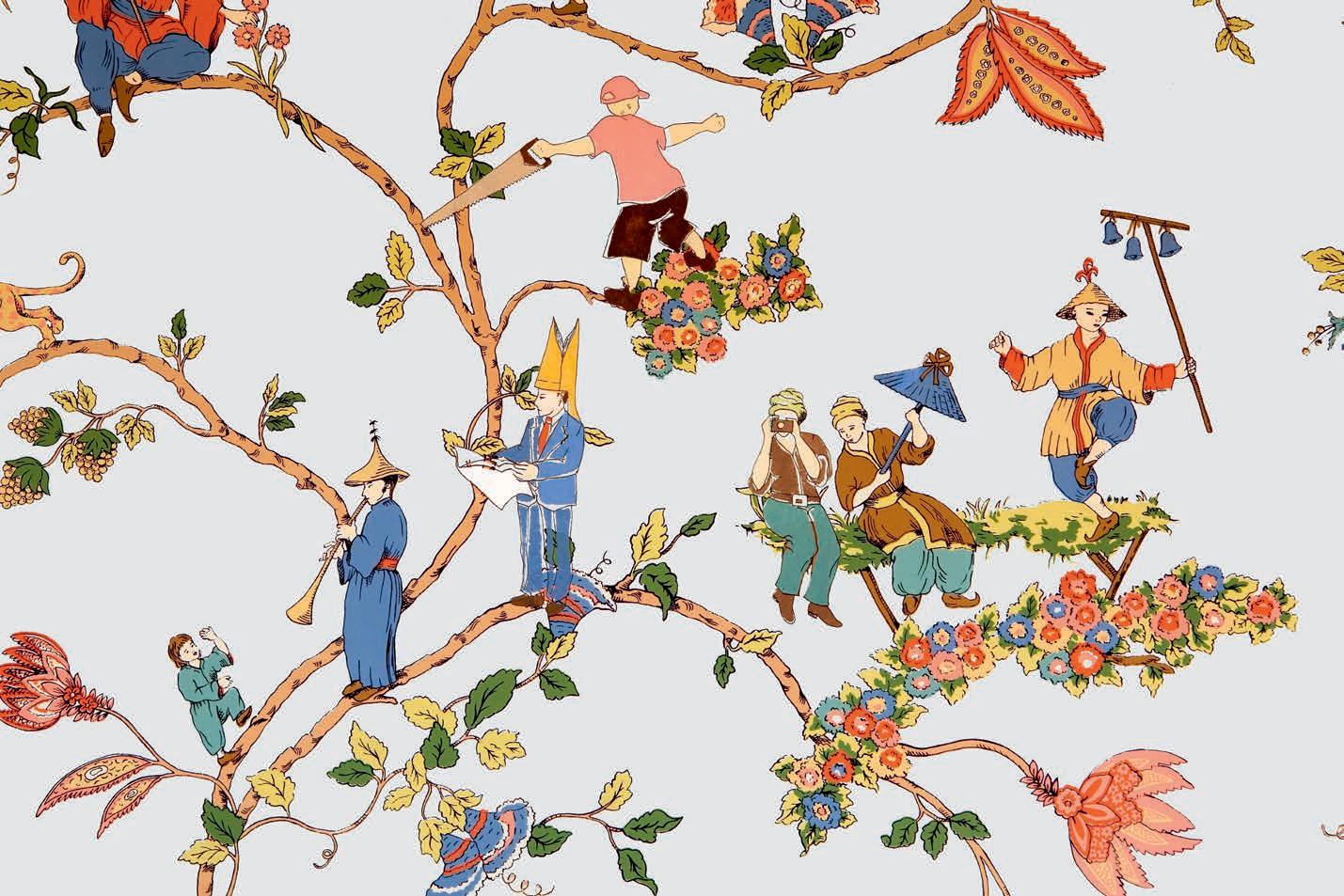

In 2007, Canadian artist Millie Chen considered the legacy of chinoiserie and Chinese-inspired wallpapers in an on-site intervention at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris, France. Responding to a real, Chinese-inspired wallpaper that remains in circulation today, Chen ipped the wallpaper s script on its head by replacing stereotypical depictions of Chinese men and women carrying umbrellas with humorous vignettes of French aristocrats, lost tourists, and contemporary European businessmen wearing Napoleon’s hat. In an artist statement based on the exhibition catalogue essay by Sandra Q. Firmin, Chen asserted, “By papering the walls of a 19th century parlor room at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris with a high-end wallpaper from a chinoiserie collection, attention is drawn to the continued domestication of the

fabled Orient as status symbol and magic carpet ride to a mystical land.” Her intervention, a reclaiming of Chinese ornamental systems displayed within European spaces, “turned the table on who is in control of the representational image.” 2

Raftery’s ten views of historic wallpapers differ from Chen and Reihana’s interventions. While theirs seek to update and reimagine their chosen subjects, Raftery does not so radically alter the form or message of the wallpapers—instead his watercolors borrow from a tradition of domestic interior painting, which was particularly popular in the 19th century. This genre of painting, practiced by women and men, amateurs and professionals, upper and lower classes, was used as a way to record daily life before photography, thereby offering a look into the past.

Let us consider this past: Coveted and consumed by western audiences in the 19th century, the enthusiasm and propagation of epic narrative wallpapers into the upper-middle market occurred during a high point of Europe’s cultural, political and economic dominance over the rest of the world. As European powers “discovered” the rest of the world, a thirst for the foreign developed at home. Ornate wallpapers were designed to offer the European public a glimpse of the world from the comfort of their living room as a form of “armchair travel.” Committees were assembled to determine topics and styles that would have broad commercial appeal,3 thus cementing the wallpapers in aftery s watercolors as relevant re ections of th century worldviews that we can ponder.

This genuine curiosity about the world led to genuine attempts to answer questions about the foreign in epic wallpapers made by artisans and manufacturers such as Velay Manufacture founded in c. 1807 in Paris, and Joseph Dufour et Cie, founded in 1797 in Mâcon.4 In promotional booklets about his wallpapers, Dufour himself wrote:

“We believe that we would earn the appreciation of the public by bringing together in a clear and accessible way the multitude of people who are separated from us by the vast oceans so that without leaving his apartment merely by looking around him the armchair traveler may experience for himself the journey that provided the subject matter.” 5

To design his wallpapers, Dufour relied on contemporary, colonial-era journals, scientific lithographs and reports from the mericas and the so called rient brought back by European travelers and adventurers. is depictions of the ther as seen in several of the wallpapers aftery found in merican homes and institutions such as Les Vues d’Italie (Dufour, c. 1823), Paysages de Télémanque dans l’Île de Calypso (Dufour, c.1818), LaGrande Chasse au Tigre dans l’Inde (Velay, c. 1818) and Les Vues d’Amérique du Nord uber, c. are highly ideali ed and pictures ue, though the reproduction of real Indian buildings in Chasse au Tigre, for example, roots Velay’s scenes to actual places. The foreign, in the French manufacturers’ unavoidably Eurocentric depictions, seems interesting, beautiful and e otic its resulting depictions impressive in scale and aesthetic value. But in their naïve depiction of what they did not know, the teams at Velay, Dufour, and Zuber waded into far deeper waters than intended. The ideali ed depictions of neighbor taly , and other ndia in the cluster of French wallpapers reveal a European vision of the world on its own terms. To claim to teach the public about a place you do not know is like trying to teach someone to read in a language you do not speak: though the intention might theoretically be noble, the results are ineffective, and, if mistaken as an authoritative source, damaging.

The hand-painted Chinese wallpapers Raftery selects as his subject are witness to a different history. Hand-painted by Chinese artists in Canton between the 18th and 19th century, these original Chinese wallpapers were an actual product of the country they came to represent in estern homes. esigned specifically for uropean and, to a lesser e tent, merican audiences, the wallpapers represent an artistic production that is distinctly Chinese while remaining somewhat inauthentic the products sold to foreigners did not resemble anything that Chinese people would have actually had in their own homes.6 Later, as the chinoiserie cra e in the est resulted in an outpacing of demand, Chinese wallpapers would be mimicked and reproduced by uropean manufacturers, resulting in the muddling of the very specific literary, artistic and historical references being made by Chinese artists in each of the original wallpapers. Thus, chinoiserie objects became further alienated from their original makers a state of affairs later re ected upon by Chen in her installation. pon being e ported from China and installed in nglish, French, and merican homes, the Chinese wallpapers took on a life of their own: they were items of great luxury that

encapsulated Chinese culture as it was understood by the West. In the context of an expanding Europe thirsty for the foreign, these exquisite wallpapers became canvases upon which Europeans projected their imagination.

The beautiful, ornate wallpapers depicted by Raftery and produced between 1770 and 1820 are precursors of a period of Chinese economic and political distress that had long-lasting effects on Sino-Western relations. China’s Daoguang Depression, a period of economic and political turmoil triggered, in large part, by the traumatizing events of the Opium War (1839-1842) and Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), led to a slump that branded China as a poor and undeveloped country in the eyes of the West, just as the latter’s economic fortunes took off with the rise of the Industrial Revolution.7 With the frantic consumption of Chinese goods and aesthetics within the context of rapidly shifting power dynamics, the world’s oldest continuous civilization was effectively reduced, in perception at least, to its ornamental powers. This limitation is one that many so-called “oriental” objects are confronted with today. Thus, popularized by Europeans when they were controlling the world, and displayed in mansions in the U.S. in the 20th and 21st century, the Chinese wallpapers represent a moment in time when the est wielded its financial, cultural and militaristic

power to extract what it wanted from others: in this case, a customized version of what they thought Chinese art looked like. The wallpapers observed and reproduced by Raftery bear witness to this shifting history of foreign enthusiasm, trade and international power dynamics.

A couple of centuries later, in the 1960s, the Corliss-Carrington House in Rhode Island (a national historical landmark) was being renovated nearly 150 years after being built. Carrington House is one of several illustrious homes that dot Providence’s College Hill neighborhood, one of the wealthiest areas in the city and home to Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design’s campuses. The house’s most prominent owner, Edward Carrington, was an evident admirer of wallpapers, and an important mercantile trader who conducted business in China, South America and Europe. During the 1960s renovations, the new owners of Carrington House, finding Carrington s original installation of Chasse au Tigre not to their taste, had it removed. The wallpaper was then conserved and placed on the walls of the neighboring Truman Beckwith House, home of the Handicraft Club, instead. A startling scene, Chasse au Tigre is firmly rooted within a colonial worldview. n fact, this imagined landscape of India takes its source images from William and Thomas Daniell’s 1795 Oriental Scenery published in London. Another impression of Chasse au Tigre exists in the “Indian Room” at Blenheim Palace, the birthplace and ancestral home of Sir Winston Churchill. Still on view in the Handicraft Club today, this relic of 19th century colonial thought conjures complicated legacies: bearing witness to an era that would seem safely distant in time, its continued existence and exposure to the public seems to lengthen the shelf life of its seminal idea. The act of preserving it, moving it from another house and installing it to a new home, in a relatively visible place, betrays a sense of nostalgia that implicates a much more recent generation of people than the original makers of this work.

The era of colonial revival in the twentieth century coincided with what would seem like a paradoxically self-conscious time for the United States. Following the Industrial evolution and the first and second world wars, the nited States found itself at the top of the political and economic pyramid. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, it was locked in a contest with the ussr, its only credible rival for world domination. At the same time, a desire to inherit a grandiose and imperial history persisted, and contemporary interpretations of art history seemed to bend context at will to fit into pervading narratives that merica, chosen by od, was glorious, and somehow always had been. It is during this time that American art historians seemed to excavate artists such as Thomas Cole, for example, from the annals of history and instrumentalize the power wielded by American institutions in the 20th century to make him and artists like him read that fit within the preferred narrative historically relevant.8 Attempts to put early Americana iconography on the same cultural playing field as internationally recogni ed masters such as . . . Turner or Caspar David Friedrich highlighted the lingering anxieties relating to the diminutive length of American history, even as the United States dominated the world.9

This is the context in which the Handicraft Club was gifted Chasse au Tigre in the 1960s. To contemplate it now, as we are compelled to with Raftery’s watercolors, is to consider its mid-century context in conjunction with the cultural circumstances in which the wallpaper was created in the 19th century. With his careful rendering of the exoticized depiction of Indian people dancing and hunting, Raftery leads us to ask the questions: What does it say about us that this wallpaper still exists, fastidiously cared for and preserved? What does it say about the generation just before ours, that they deemed this object culturally significant enough to move it from one Providence mansion to another? On one hand, this careful stewardship could be read as preserving an important piece of art history: as noted earlier in this essay, the wallpapers are each significant artistic accomplishments, beautiful in their own right, impressive in their scale and technical ambition, and bearing witness to an important chapter in history. A less charitable reading of the situation places recent generations as complicit in furthering colonial narratives in a bid to position themselves at the cultural apex of the world. Clearly, the colonial history implied by Chasse au Tigre was not only inoffensive to a mid-century American audience but desirable: by co-opting 19th century European imperialist grandeur, 20th century America, eager to impose itself on the world stage, picks up the baton of cultural supremacy.

A little further south, in 1961, Jackie Kennedy installed in the White House Les Vues d’Amérique du Nord—the wallpaper that was recently petitioned against at Brown University. It was designed in 1834 for the French manufacturer Zuber & Cie by an artist named Jean-Julien Deltil, who had most likely never set foot in America. Deltil created his composite and fictional view of North merica using as reference the travel journals of a contemporaneous French naturalist, published in 1828-29. Ambitious in scale and subject matter, the wallpaper inadvertently taps into powerful narratives surrounding ecclesiastical experiences of American nature, U.S. ingenuity and industrialism, and rosy recollections of racial felicity in Jacksonian America. By na vely placing lack and hite people as e uals, and Native mericans as part of the fauna and ora, Vues d’Amérique re ects a French vision of merica that supports the preferred recounting of American history, and if taken as fact rather than ornamental fiction, releases white society from accountability a state of affairs that is perhaps punctuated by its auspicious placement in the White House during the Civil Rights Movement. The myth of American excellence initially sold as a provincial daydream to European audiences unwittingly reinforced pervading contemporary narratives surrounding American Exceptionalism and Manifest Destiny that became relevant on the global stage as the United States grew more powerful. Certainly, the durability of the image far exceeded the artist’s initial expectations. The life led by eltil s wallpaper arguably re ects more on recent generations than it does the original makers: certainly, its existence rests on its makers’ decision to immortalize their misguided vision of the world. Its survival and propagation, though, rests on our own desire to hold on to this vision, and to keep it alive.

The wallpapers Raftery considers in his work represent the best and worst of us. In his watercolors, aftery s un inching ga e holds both admiration and criticism, and

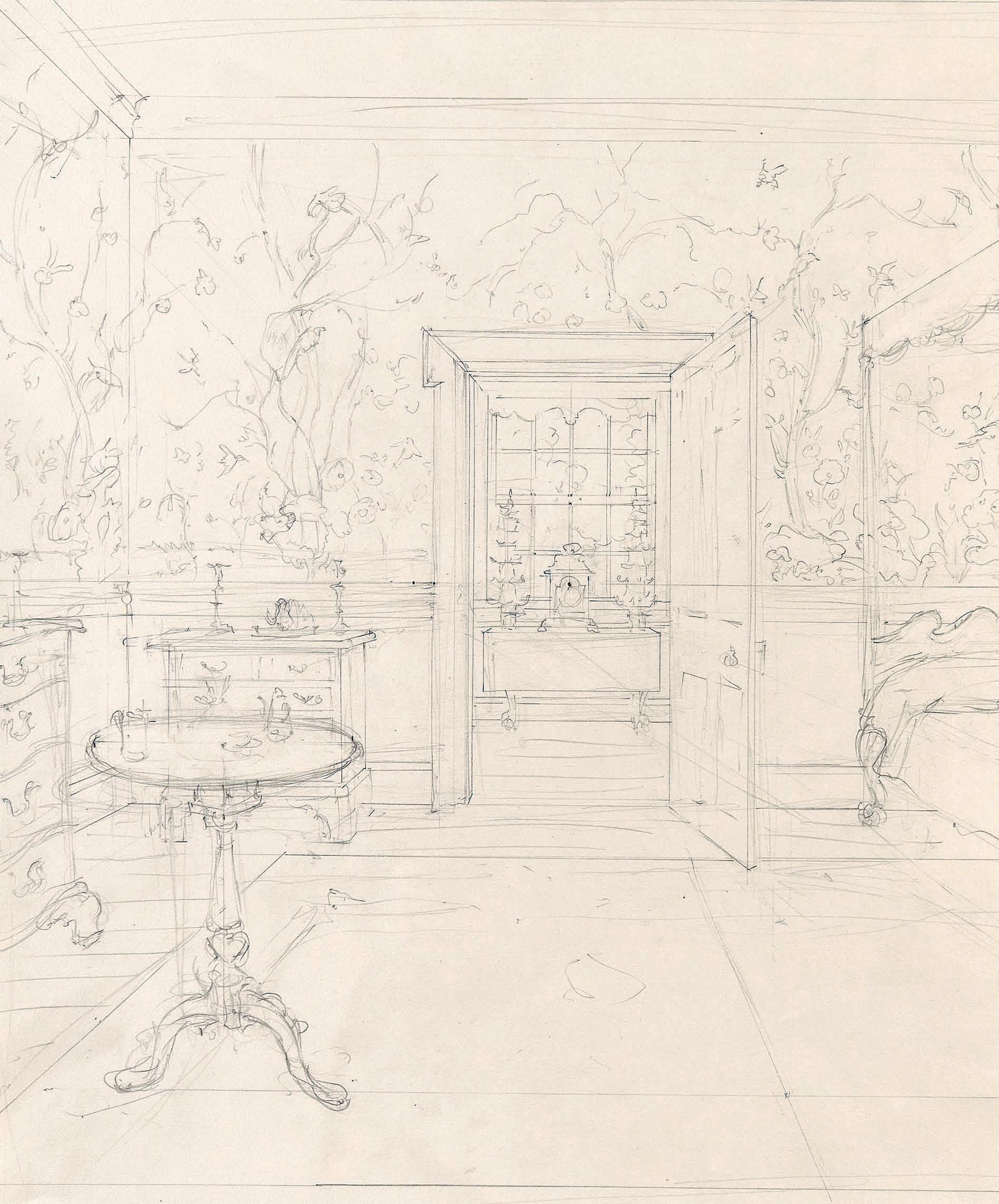

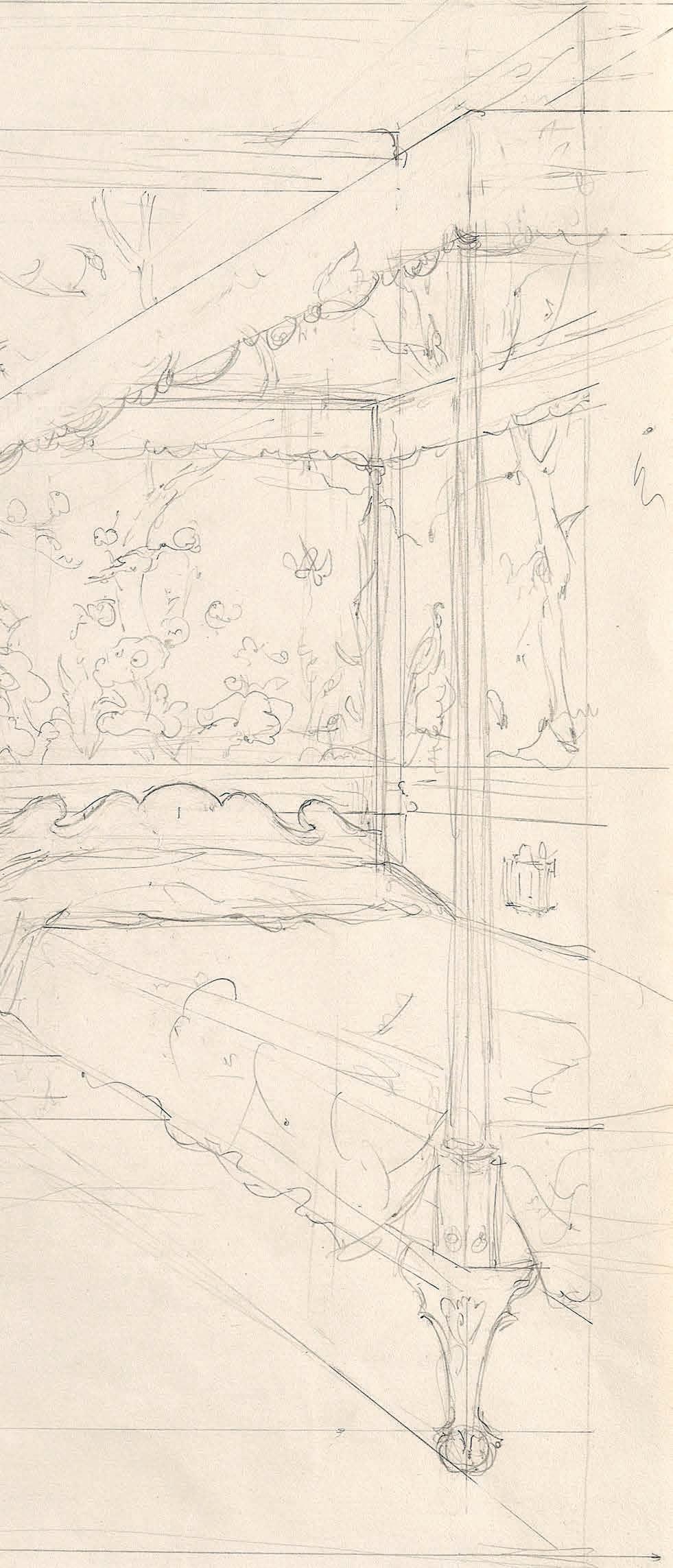

this dichotomy is evident in his thoughtful, careful, and technically complex handling of his subject. Raftery spent nearly four years studying or considering the composition, structure, and geography of each wallpaper. Beyond his intellectual musings and reckonings, to achieve these new works he poured countless hours in careful in-situ sketches which led to dozens of preliminary pencil drawings that later culminated in a lithographic drawing and grisaille for each work. The complexity of his process re ects the seriousness with which aftery approached his subject. These are watercolors that took time to create, and, like wallpapers themselves, take time to reveal their depth.

aftery s new work re ects on wallpapers that are symbolic of uctuating worldviews and politics. As our contemporary zeitgeist pushes for change, questions surround–ing what to do with the icons and relics of a past whose values do not match up with our own continue to preoccupy us. How does one handle an object of beauty that is at once a celebration of colonialist thought and a legitimately rare and precious relic of art history? Surely, it can no longer be responsibly treated and used as it was before—as simple ornament. Surely, these wallpapers, catering to broad cultural appeal in the 19th century, should be examined with a critical eye as artists, thinkers, home owners, institutions and society at large walk the fine line between moving forward from the past while also engaging with it. Surely, the solution to these questions lies with critical consideration, thoughtful discourse, and, at times, headon engagement. This is the work that Raftery undertakes in ten penetrating views of landmark wallpapers, which betray far more than initially meets the eye about the society they came from, and the society they exist in today.

1 McDougall, Ruth. “in Pursuit of Venus [infected] | An interview with Lisa Reihana.” Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, June 18, 2015.

2 Firmin, Sandra Q., “Sensory Navigation,” Millie Chen: Extreme Centre, Paris & Caen: Centre culturel canadien, Wharf Centre d’art contemporain de Basse Normandie, 2009.

3 Hendon, Zoe. “An Introduction to Wallpaper.” Wallpaper History Society (blog). Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.wallpaperhistorysociety.org.uk/an-introduction-to-wallpaper.

4 Claval, Paul. “Le Papier Peint Panoramique Français, Ou l’exotisme à Domicile.” Le Globe. Revue genevoise de géographie 148, no. 1 (2008): 65–87.

5 Emlen, Robert P. “Imagining America in 1834: Zuber’s Scenic Wallpaper ‘Vues d’Amérique Du Nord.’” Winterthur Portfolio 32, no. 2/3 (Summer 1997): 189–210.

6 Clifford, Helen. “Chinese Wallpaper: From Canton to Country House.” East India Company at Home, 1757-1857, 2018, 39–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt21c4tfn.9.

7 Glahn, Richard von. “Economic Depression and the Silver Question in Nineteenth-Century China.” Global History and New Polycentric Approaches, December 7, 2017, 81–118.

8 Flexner, James Thomas, That Wilder Image: The Painting of America’s Native School From Thomas Cole to Winslow Homer. [1st ed.] Boston: Little, Brown, 1962.

9 Novak, Barbara. Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting, 1825-1875. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

1. H. F. du Pont: “At the death of my father on the 31st of December, 1926, I took over the estate and in 1929 began to enlarge the house still further, building another wing, which was to take two years to complete, and installing into it rooms from old houses along the eastern seaboard… After about twenty years, I gave the house and my collection to the Winterthur Museum.” John A. H. Sweeney, introduction by Henry Francis du Pont, The Treasure House of Early American Rooms, The Viking Press, New York, 1963.

2. Cooper Hewitt Museum, Vues d’Italie, manufactured by Dufour et Leroy (France); block-printed on joined sheets of handmade paper; H x W: 221 x 1440.2 cm (7 ft. 3 in. x 47 ft. 3 in.); museum purchase from Sarah Cooper-Hewitt, Pauline Cooper Noyes, and General Acquisitions Endowment Funds; 2000-29-1-a/mm

3. The most complete information about French scenic wallpapers is in Odile Nouvel-Kammerer, French Scenic Wallpaper: 1795 – 1865, Musées des Arts décoratifs, Flammarion, 2000. The author summarizes the extensive records of the Carlhian Archives at the Getty Research Center, a collection of photos and records that catalogues almost every known scenic wallpaper design.

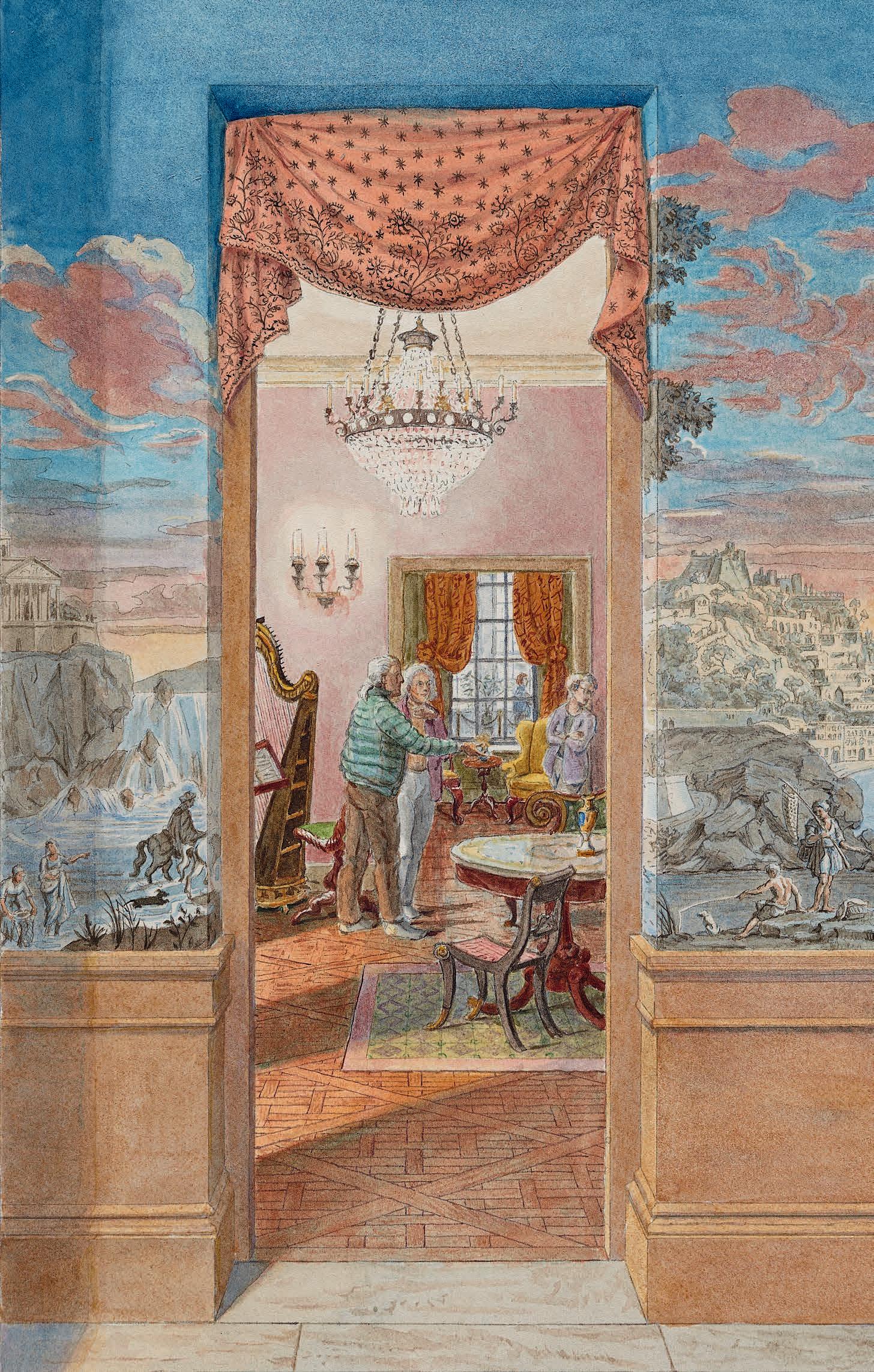

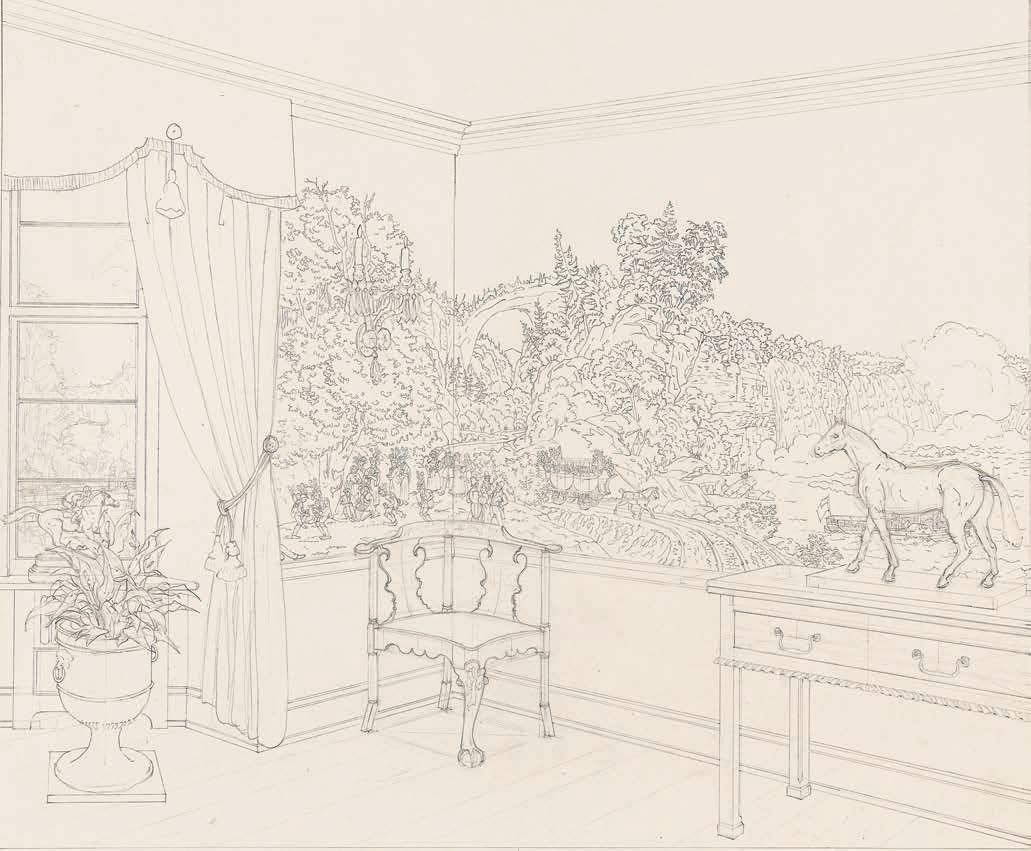

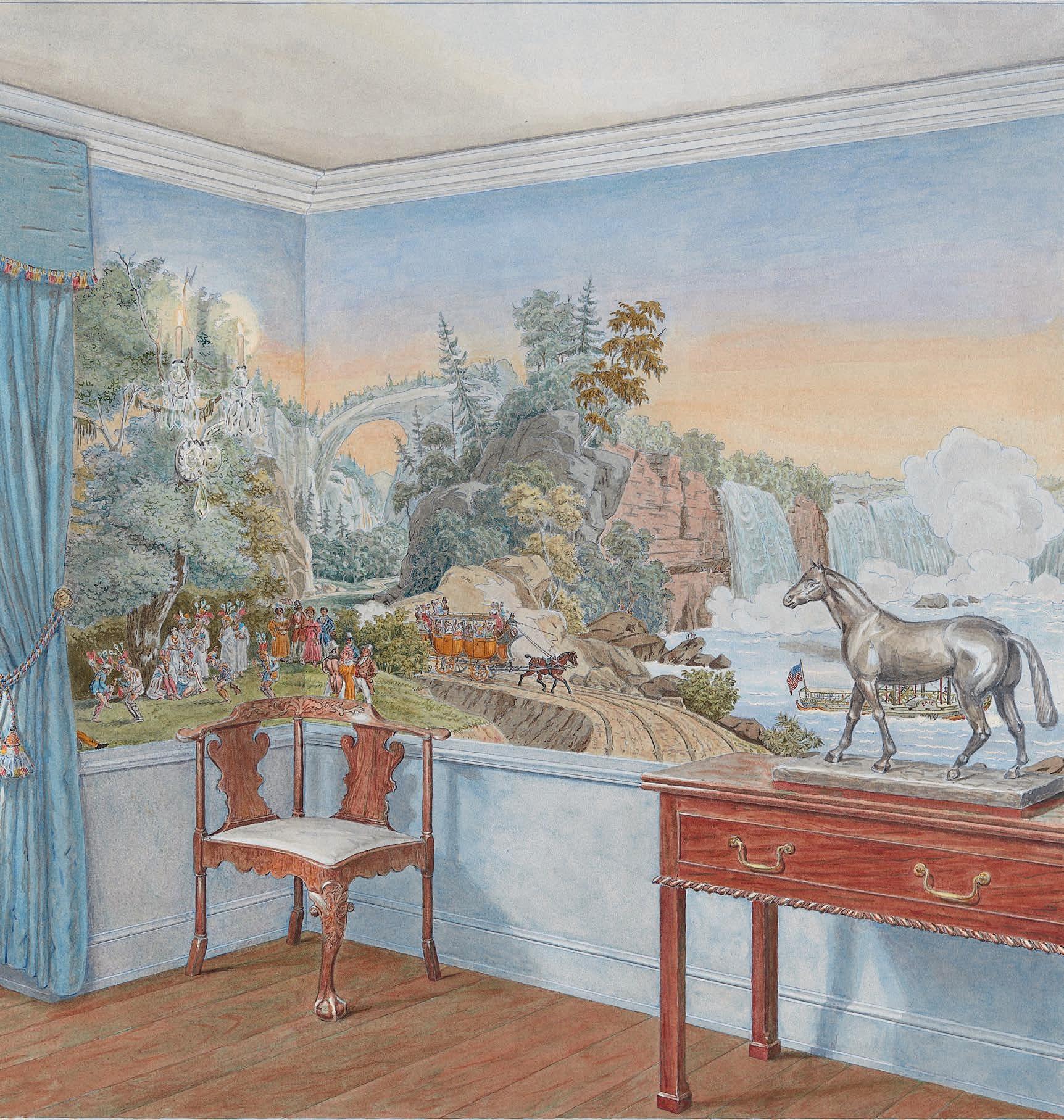

february 2021 was my first road trip/museum visit since the start of Covid, with the Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library in Delaware as my destination. After gloomy weather on the drive, the sun appeared just as I entered the estate, illuminating recent snow and, further along, the oddly oversized treasure house created in the 20th century by Henry Francis du Pont as he radically expanded his family home.1 Stephanie Delamaire, Curator of Paintings and Prints, whisked me through at least rooms. ven though was stunned by the magnificence of everything, knew where I would start drawing.

The Baltimore Drinking Room is dominated by Vues d’Italie, produced by Dufour, the French wallpaper company, circa 1820. The original version was printed in shades of ochre and brown 2, but Winterthur’s set is from the middle of the 19th century, after the woodblocks had passed to another manufacturer. The style of printing was updated to incorporate a blended ground of gold and salmon pink melded into Prussian blue, linking the water and sky. 3 The resulting sunset effect in this deeply idealized view of Italian ports, cities and countryside is unforgettable. It is also in perfect condition, never hung until acquired by du Pont.

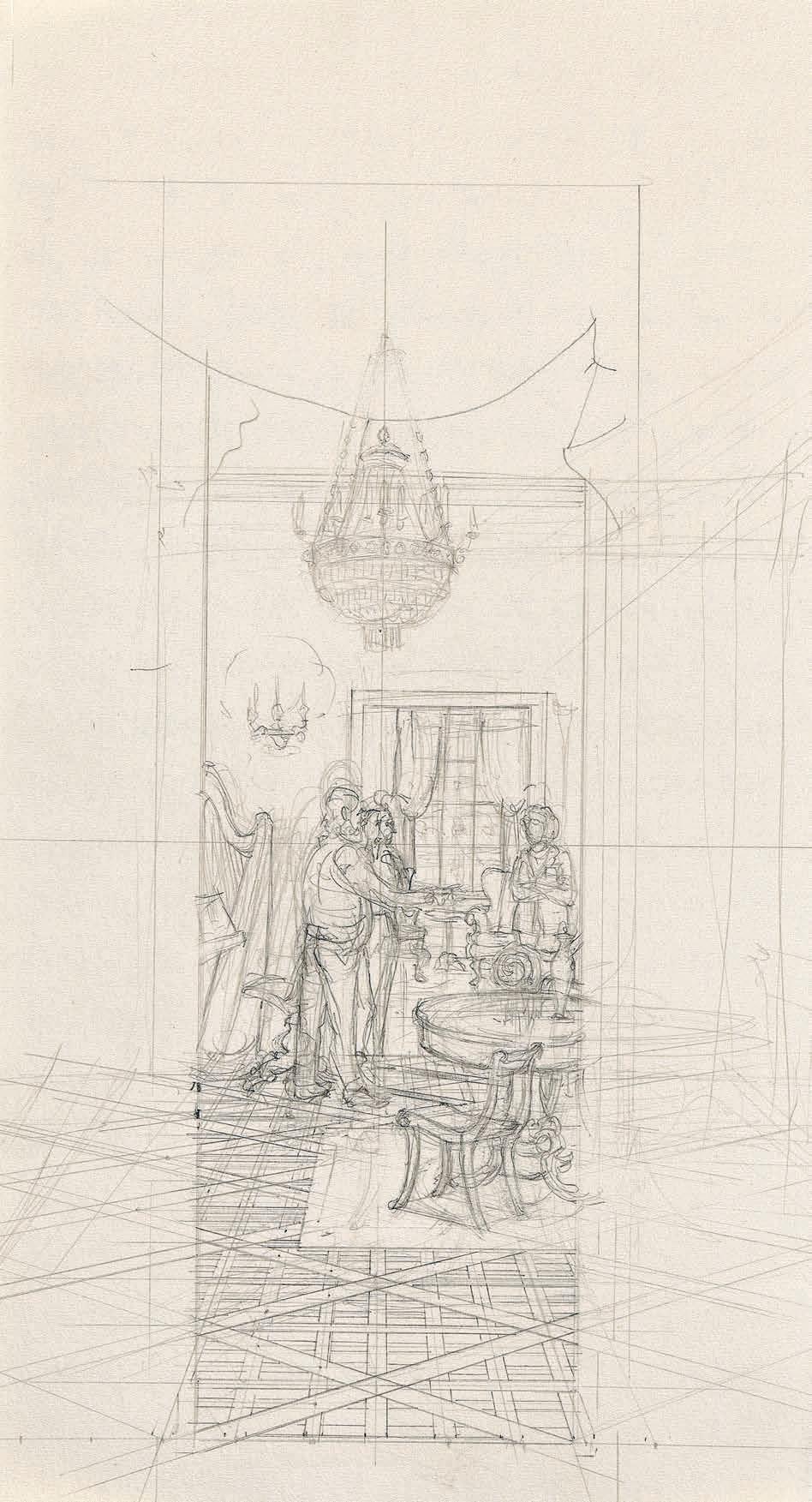

My intention in visiting Winterthur was to study the design imperatives of French scenic wallpaper in an effort to understand the formal mechanics embedded in these woodblock-printed murals. I needed to see them installed in rooms, framed by architectural elements, surrounded by furniture, people and views of the outdoors. As I started sketching Vues d’Italie, the power of the wallpaper’s horizon line dominated every aspect of the room and I made it into the focal point of the perspective scheme for my drawing. y doing this brought the fictive world of the wallpaper into the depicted world of the room and the view out the window.

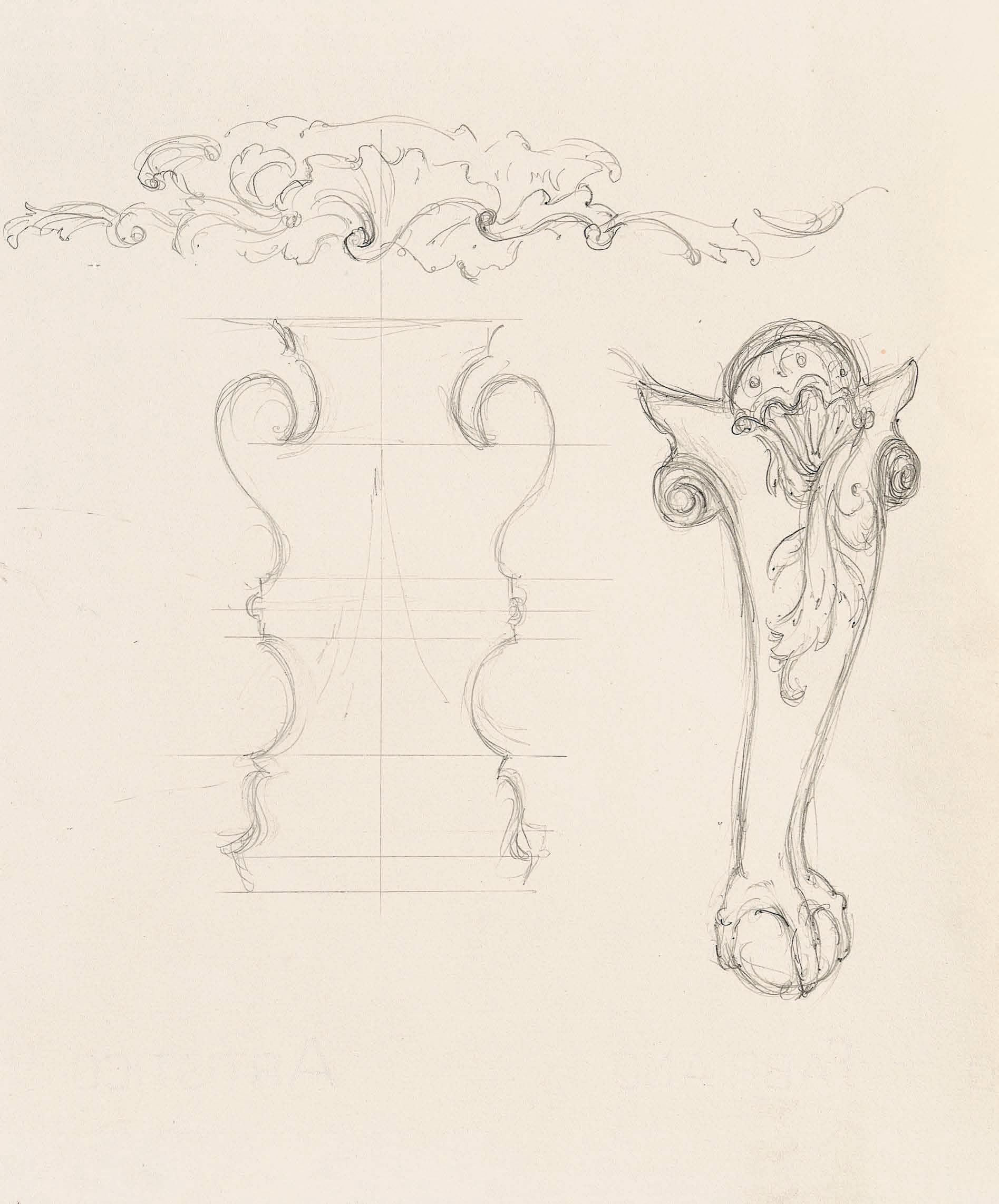

Drawing the wallpaper reverse engineers the complex design and production process that resulted in these monumental prints. A manufacturer such as Dufour presented his designer with a subject combining panoramic potential and appeal to a range of international consumers. Consulting available print sources and experts in scenic design, costume and botanical art, the designer pieced together a composition wide enough to make 25–35 nonrepeating lengths of wallpaper suited to hang in almost any large room. The final section joined with the first sheet to make a continuous scene. When the drawn design was approved, the designer made a full-scale painting with distemper, the glue-based paint that was also used to print the wallpapers. This painting was done in the exact color range proposed for the wallpaper and had to account for every detail. The painting was then traced onto the hundreds of hard pearwood woodblocks required to recreate the colors. These were carved and handed over to the printers, who had to print them in perfect registration and color matching over the entire panorama.

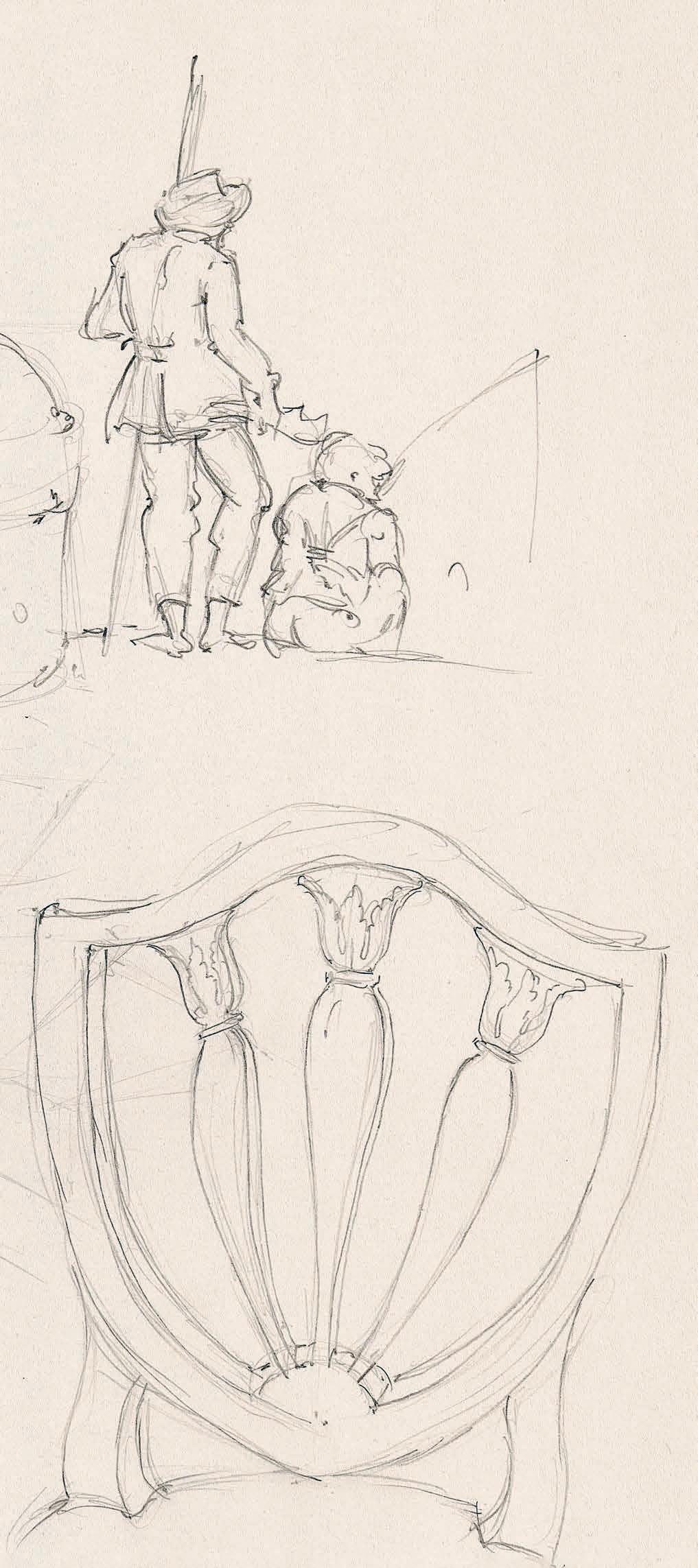

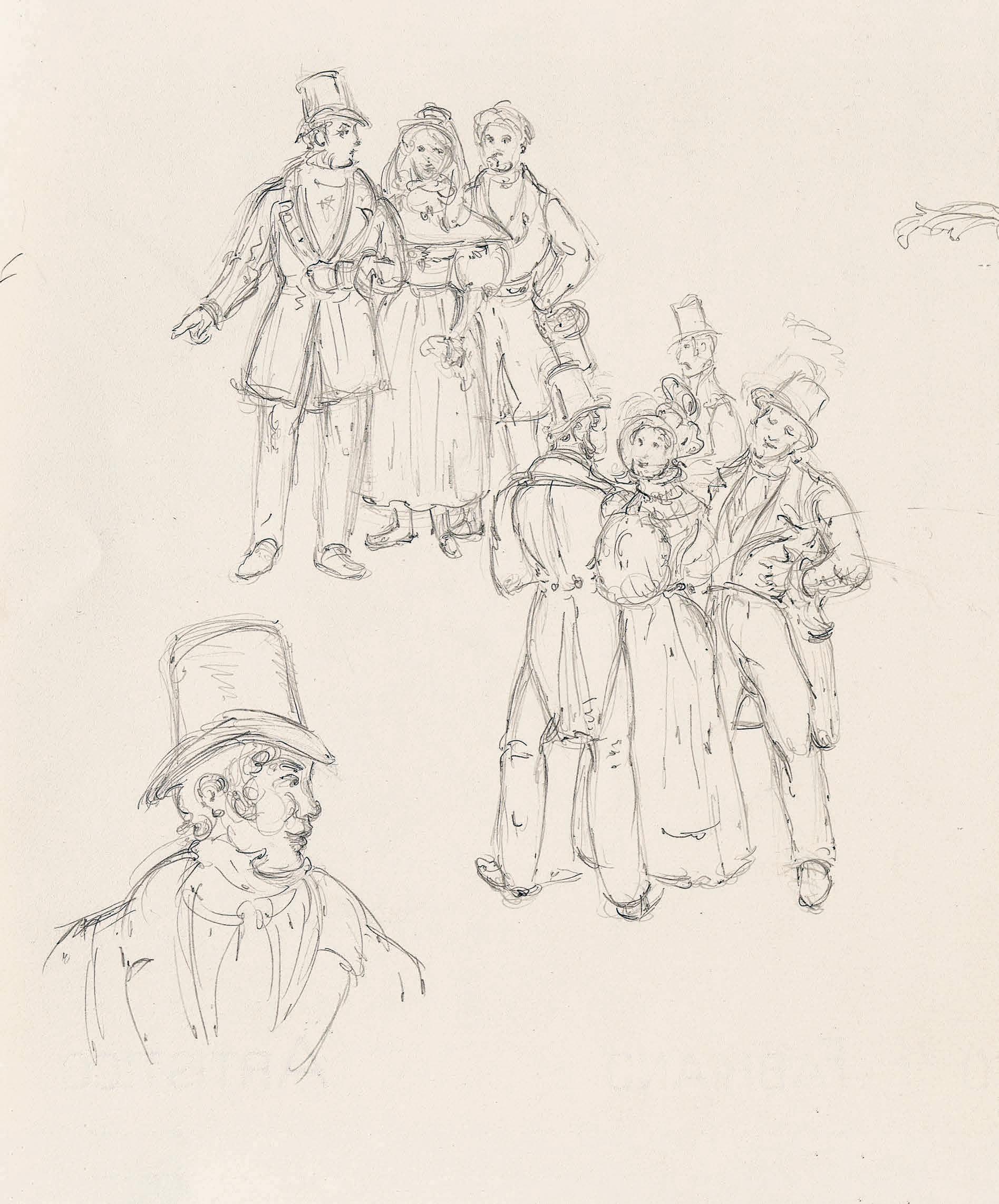

endering individual figures from the wallpaper in graphite removed the stiffening effect of their translation from painted cartoons into multiple carved woodblocks and revealed the classical academic training of the anonymous designers. Furniture proved especially difficult for me to draw. u Pont s e uisite e amples of altimore furniture from the Federal Period are deceptively simple, intolerant of any deviations from their harmonious proportions. The oval cellaret presented me with a new perspectival problem.

ack in Providence with my sketches and photos, wanted to make something that showed how see the room, not what it looks like. n reality, it is a bit gloomy because of the ultraviolet filters on the windows, and it is too small to allow a complete view while sitting in the space. oving through linear studies, tonal wash drawings, and finally, a grisaille ink drawing gla ed with transparent watercolor, found a way to blend the wallpaper and the room into a unified e perience a pictorial fiction, representing my understanding of this place.

vues d’italie is enormous . The entire décor comprises 33 strips, more than could fit into this room du Pont had to install the rest of his set in a corridor upstairs. hen it was designed, France had just returned some of the masterpieces of painting and sculpture removed from taly by Napoleon s army. There is no hint of politics in ufour s wallpaper. Pictures ue peasants dance around a statue of irgil as a volcano smokes in the distance. The fisherfolk appear to strike poses from the anti ue as they perform their tasks. The genius of ufour s designers is that this highly derivative image, incorporating do ens of print sources and every available clich , could be so authoritative. hen am in this room, am indeed in taly.

Figures

winterthur held two major revelations for me .

First, I realized Henry Francis du Pont was more than someone who amassed American antiques. He brought the eye of an artist to the rooms he created. His materials were the superb furniture, architectural elements, textiles, ceramics and wallpapers he collected. Expert craftsmen executed and installed Winterthur’s ensembles under his careful supervision. Although objects are related by historical context, these are not period rooms in the usual sense. As manifestations of du Pont’s sensibility, each installation rewards attention to its colors, textures and spatial relationships.

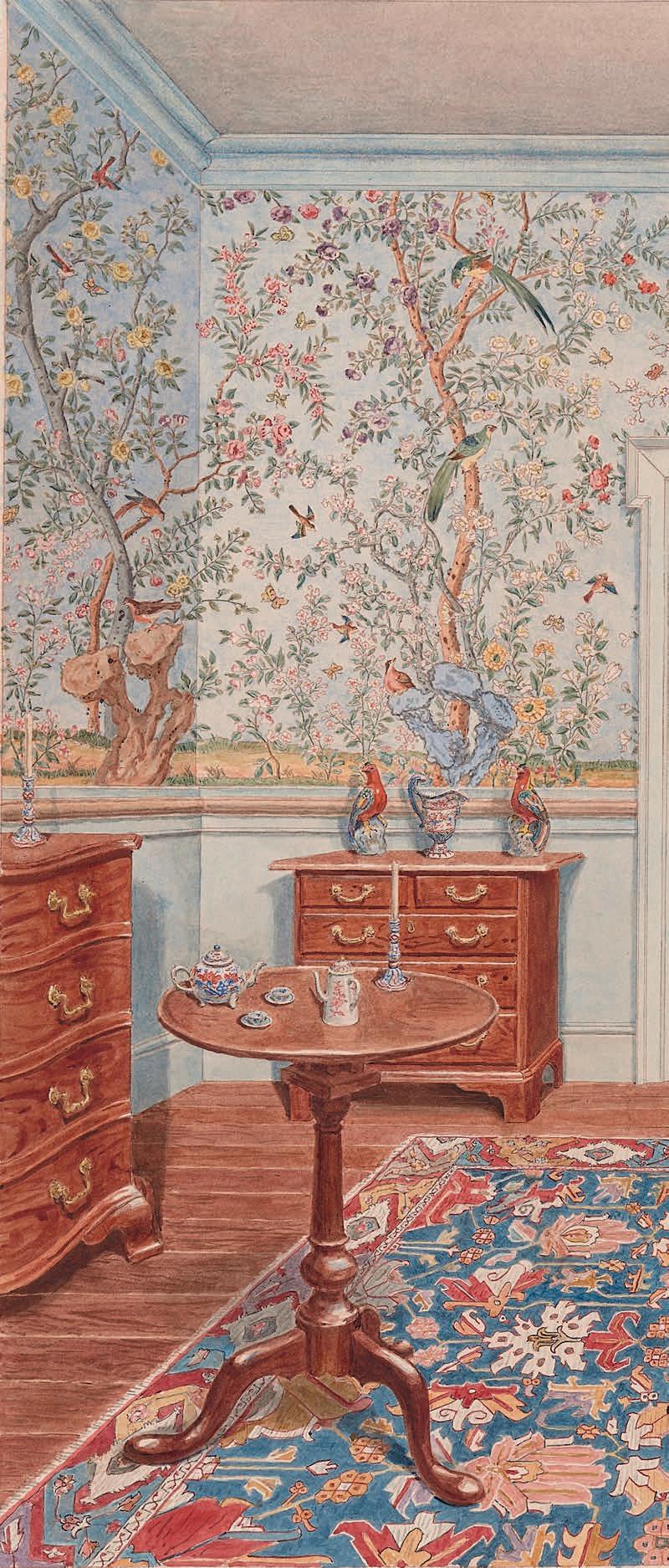

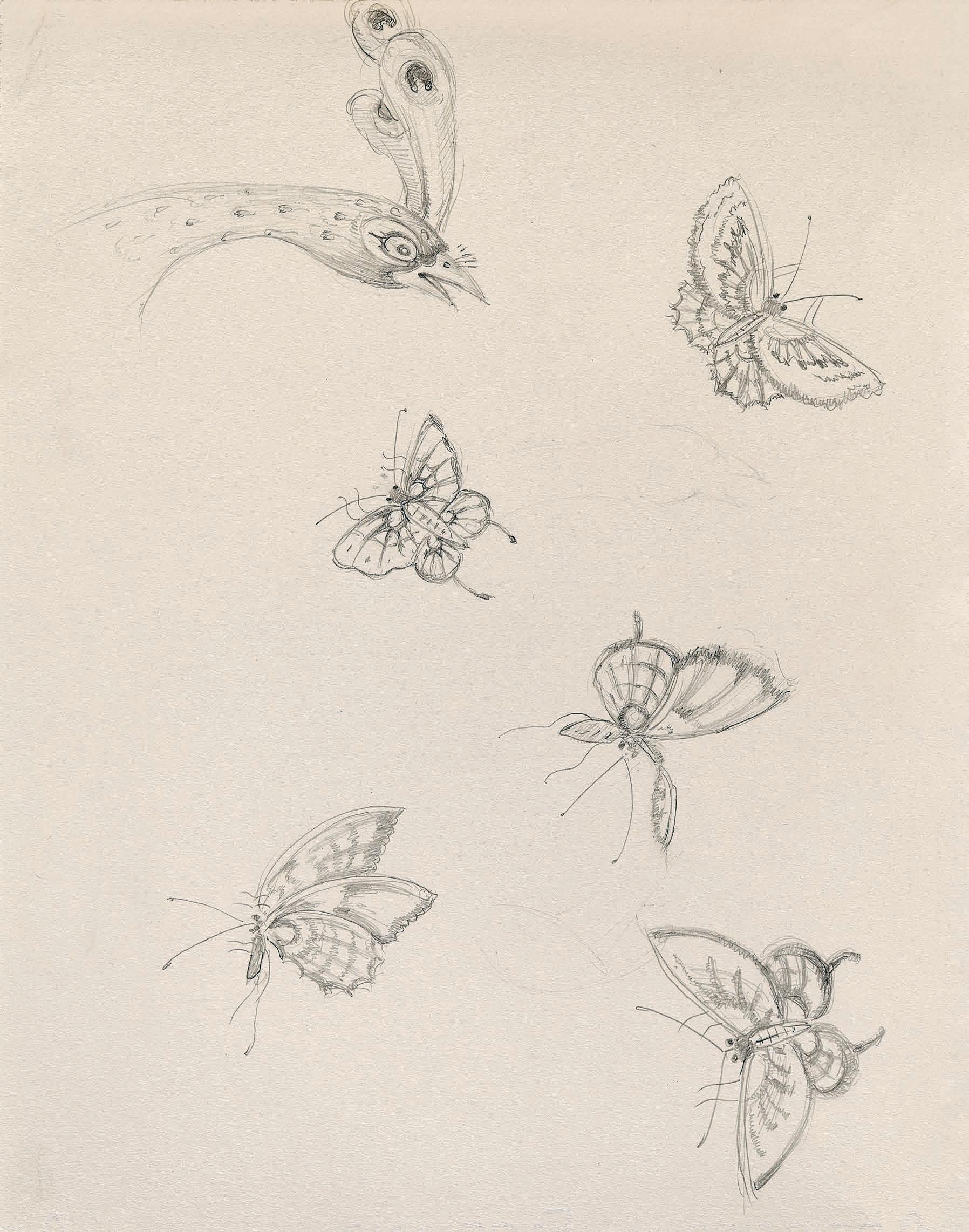

Second, I was exhilarated by the sheer beauty of Winterthur’s Chinese handpainted wallpapers. Though my focus had been on French wallpapers, the Chinese work in the Philadelphia edroom proved irresistible. Trees and owers, populated by birds and butter ies, emerge from scholar s rocks, joined by a Turkish carpet to form an ever-blooming garden. Du Pont matched these features with the pale apricot bedcoverings and the heartbreakingly lovely blue and brown of the walls and trim. Rich mahogany adds dignity to the color harmony.

It is no wonder that these wallpapers were embraced by Europeans and Americans as the ultimate decorative lu ury when they first emerged from the port of Canton in the 18th century. They are a commanding presence in any interior, holding their own through a succession of Western styles from rococo to neoclassical and Victorian. Never used in Chinese interiors, they are nonetheless completely Chinese. very ower, bird and color has a specific meaning, evident to the makers, hidden from the end users. 4

It is very challenging to draw the Chinese designs. When I look at the French wallpapers, I understand the purpose of each shadow, shape, line or perspectival move. These (primarily French) pictorial techniques were ingrained in my art education and are intimately attached to my way of seeing. I feel free to change things, generalize, fudge the details. Only by carefully following every stroke of the painters as I crawl across the image can I capture something of the Chinese pictorial values and avoid easy approximations of European cabbage roses and Audubon birds inculcated throughout my life.

Linking the Chinese and French wallpapers is absolute clarity in the depiction of all pictorial elements, down to the smallest leaf or rock. This overriding decorative lucidity explains why these exceptionally complex schemes have remained compelling over many generations and stylistic changes.

Chinese export porcelain candlesticks, 2022,graphite, 12” × 11”

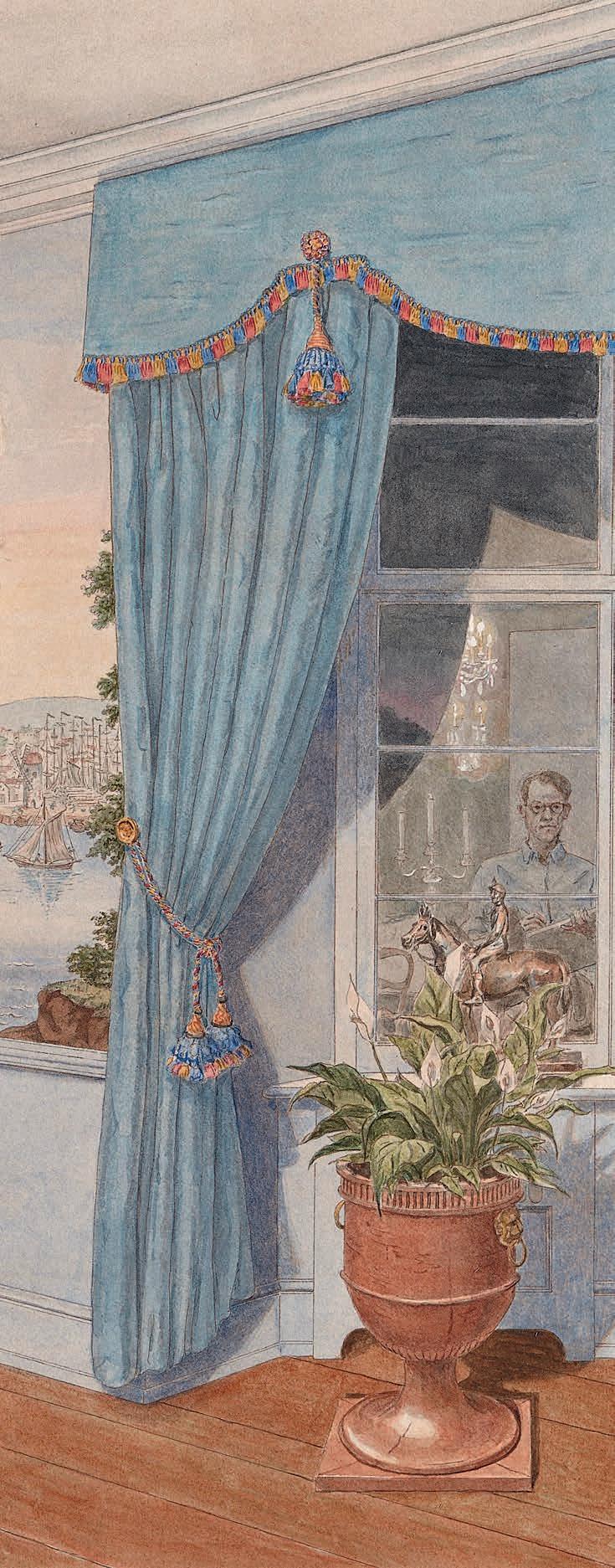

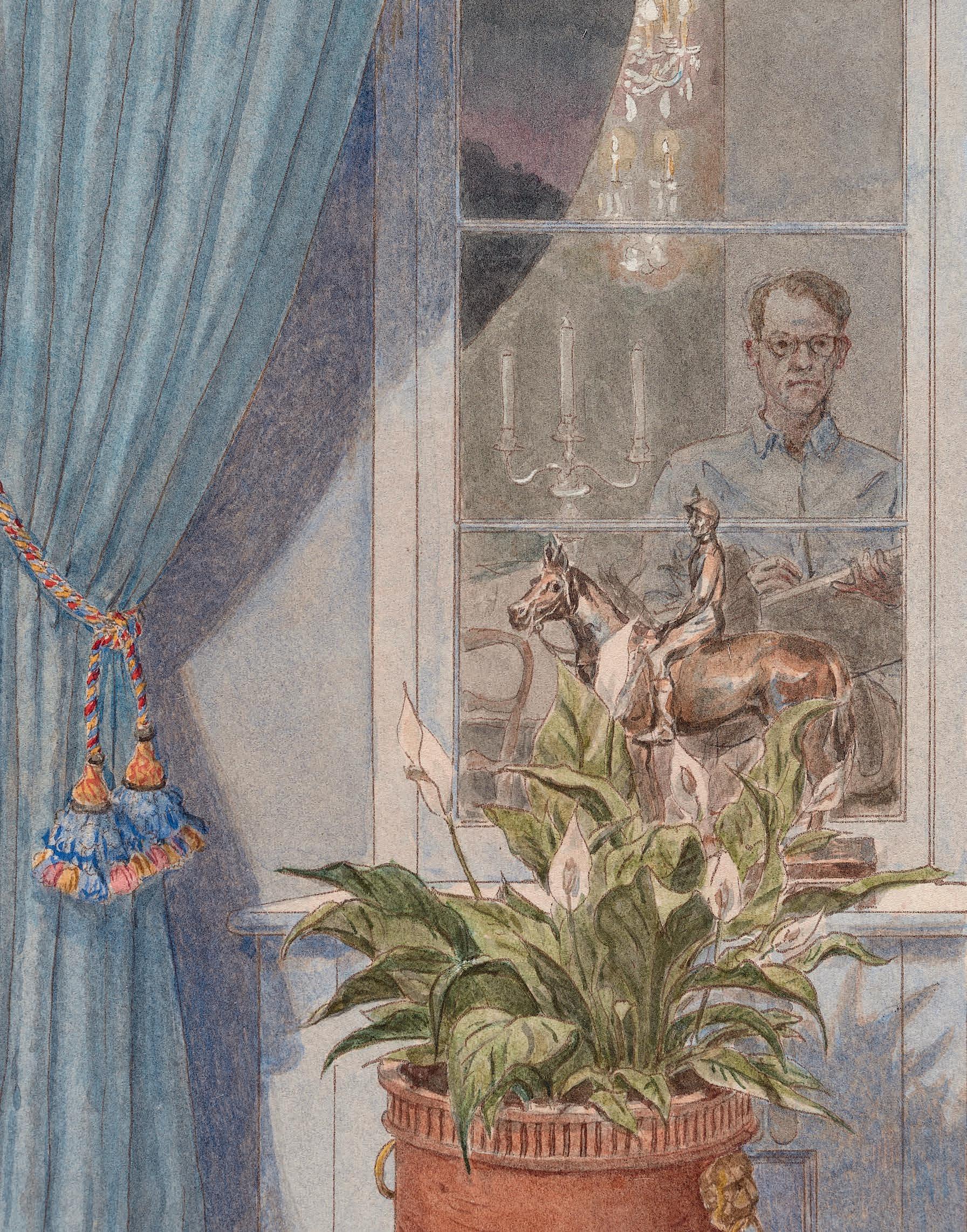

i first saw this room twenty years ago during a wallpaper tour of College Hill in Providence, Rhode Island. It was quite posh after a recent decoration executed by British designer John Stefanidis, but his luxurious surfaces and accessories were no match for the power of the pristine Chinese wallpaper or Federal era architect John Holden Greene’s perfectly proportioned woodwork. The owner told us he found the peacocks to be menacing. He was right. The Chinese painters unfailingly capture the dinosaur ancestry of birds.

In June 2021 I met the current owner, who agreed to let me draw the wallpaper (he doesn’t mind the peacocks).

Corliss-Carrington House was built by John Corliss in 1810 and sold in 1812 to China trader dward Carrington just as he was finishing his term as nited States Consul in Canton.5 Carrington obviously had access to the best Chinese stuff. This paper is remarkable because it has never been moved and has only been minimally treated. It was made with superb materials that have stood the test of 200 years. Every touch is fresh.

Because of this, I can follow each step in the process of executing the repeating panels. The translucent, pale cream paper does not have the applied ground often found on Chinese and French wallpapers. The studio director was able to trace the outlines of the design onto each sheet by placing one piece of paper on top of the other. White paint, with just the slightest gloss, came next, articulating the bamboo and setting up at pads on which the owers, birds and butter ies would be painted. Then the specialists did their work. Individual hands are recognizable in the different motifs only the butter y painter used drybrush. Finally, someone came in with an infinitely fine brush to outline the bamboo and articulate foliage and owers, delighting in the complex tendrils. I am sure it was all done at lightning speed.

The birds, butter ies and owers are in color. The bamboo is rendered in white with black outlines with just the paper color for contrast – unbelievably beautiful!

There are still many questions about the Chinese painters. Their wallpapers are usually studied in relation to European and American decorative arts and are separated from canonical literati and amateur brush-painting traditions valorized by most collections of Asian art around the world. Research has not revealed anything about the identity of artists or workshops, how they came up with their designs or how they communicated with the end users.

East Parlor with Chinese hand-painted paper, 2023, artists unknown, watercolor, 16” × 22.5”

carrington, or perhaps his wife, loriana hoppin , also acquired French scenic wallpapers, which were available from sellers in Providence. They selected Les Paysages de Télémaque dans l’île de Calypso, attributed to Xavier Mader and printed on 25 eight-foot long strips of paper from 2,027 woodblocks in 85 colors by Dufour and Cie., Paris circa 1818.6 This bare description explains why such panoramic wallpapers are the pinnacle of color printing in any period. Nothing of comparable scale and technical ambition had ever been attempted. Issued in large editions over many decades and marketed to customers of upper middle wealth, they survive in significant numbers, attesting to the continuing value placed on them by successive generations.

Based on François Fénélon’s 1699 continuation of Homer’s Odyssey, the wallpaper tells the story of Telemachus’ search for his father, Odysseus. This early e ample of fan fiction was controversial in its time, understood as an allegory of moderate government aimed at the autocratic Louis XIV. It became one of the most popular texts of the 18th and early 19th centuries, inspiring many works of fine and decorative art.

The encounter between Telemachus and Calypso takes place on her magical island. This geographic conceit proposes a vantage point in the center of the room from which we can survey the entire tale as it progresses from right to left. Starting from the door, Telemachus, encouraged by Cupid, moves to embrace the nymph, Eucharis, while a jealous Calypso spies on them from her garden. Further on, two nymphs offer owers at an altar. The action continues on the other side of the room where we see that the sacrifice is to a statue of emeter. eyond this is a beach with the boat Telemachus has built in order to continue his quest for Odysseus. It is being set on fire by nymphs, once again egged on by Cupid. entor, the goddess inerva in disguise, throws Telemachus off a cliff so he can swim to a ship seen in the distance as a despairing Calypso collapses into the arms of her attendant.

In this wallpaper we see France presenting her best self. Mader’s elegant neoclassicism was a bit conservative by 1818, but is the ideal style for this classic text. Layers of erudition are displayed in the accurate botanicals, elaborate perspectives and carefully realized architecture and statuary. This is very much a work of the early 19th century, but the timeless setting allows us to contemplate it without reference to the politics and problems of the period when it was made. Fénélon’s romance, and the art it engendered, including Dufour’s wallpaper, came to mean many things to many people. ne wonders how ndrew ackson re ected on the version of Télémaque that hangs in his retirement home, The Hermitage, near Nashville, Tennessee.

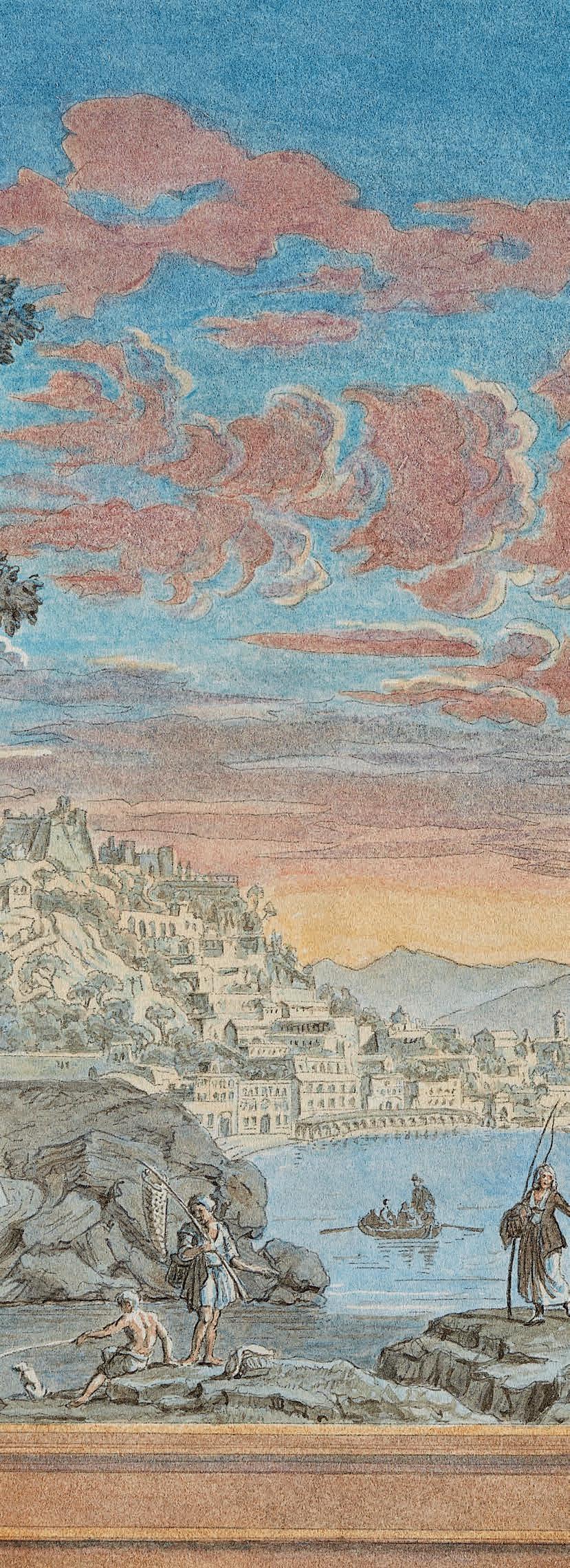

wallpaper manufacturers recognized the allure of far ung places of the globe to consumers stuck in prosaic estern circum stances in urope or North merica, creating products that feature e otic settings though often under uropean imperial rule buffered by a gloss of educational value. Their prime function was entertainment. Set in distant but actual locations, they share a great deal with story ballets, comic operas and popular theater depicting similar subjects. This is certainly the case with Grande chasse au tigre dans l’Inde, published by elay in Paris prior to .

The version drew is installed in the andicrafts Club in Providence. Previously, it hung for years in the northwest parlor of Corliss Carrington ouse. ocumentary photographs show it covered with Chinese objects collected by Carrington. n the s it was removed from its original setting and conserved before being donated to the Providence Preservation Society. Since that time it has been the primary feature in the assembly room of the club s e traordinary home in the Truman eckwith ouse, designed by ohn olden reene in . 7

Tiger hunting was a trope of th century representations of ndia, as attested by illiam akepeace Thackeray s satirical account of oseph Sedley s e ploits in Vanity Fair . elay s designers found specific details in the work of ndian artists employed by the ast ndia Company, as seen in the elaborately outfitted elephant loaded with hunters or the e uisitely turned out rider leaping at the doorframe. ritish topographi cal prints were culled for a documentary touch. The shoreline of the anges was taken from Oriental Scenery, a series of a uatints published by Thomas and illiam aniell between and . uotes from earlier uropean art abound the hunter on the rock gestures with the hand of ichelangelo s dam, and the archer, in his heroic nudity, recalls any number of reek, oman or Neoclassical e emplars.

The producers of this wallpaper and their designers had no direct knowledge of ndia, but they knew what their customers wanted some thing to take them beyond their ordinary worlds, an escape. n this case, the ndians are stereotyped as fearless hunters and e ceptional horsemen, their ferocity e uated with that of the tigers and leopards. hen in this room often ponder the irony of this strange scene being acted in perpetuity as life goes on at one of the most charmingly genteel corners in Providence.

Grande chasse au tigre dans l’Inde by Velay: Hunters, 2022, ink wash, 16” × 17”

OPPOSITE Grande chasse au tigre dans l’Inde by Velay: Hunters, 2022, watercolor, DETAIL

in 1904 the handicrafts club was founded in the wake of the Arts and Crafts Movement for the “promotion of artistic work in all branches of Handicrafts.” It was and remains an all-women’s club where members learn techniques and make and exhibit their work. For many years each member constructed and decorated her own Hitchcock chair from scratch. Every chair was carved and turned in a different form, seats done in caning or rush, woodwork lacquered red, stenciled in gold with a personal design and signed by the maker. These chairs, and other objects and collections scattered over the club, attest to the avid creativity of the members for almost 120 years.

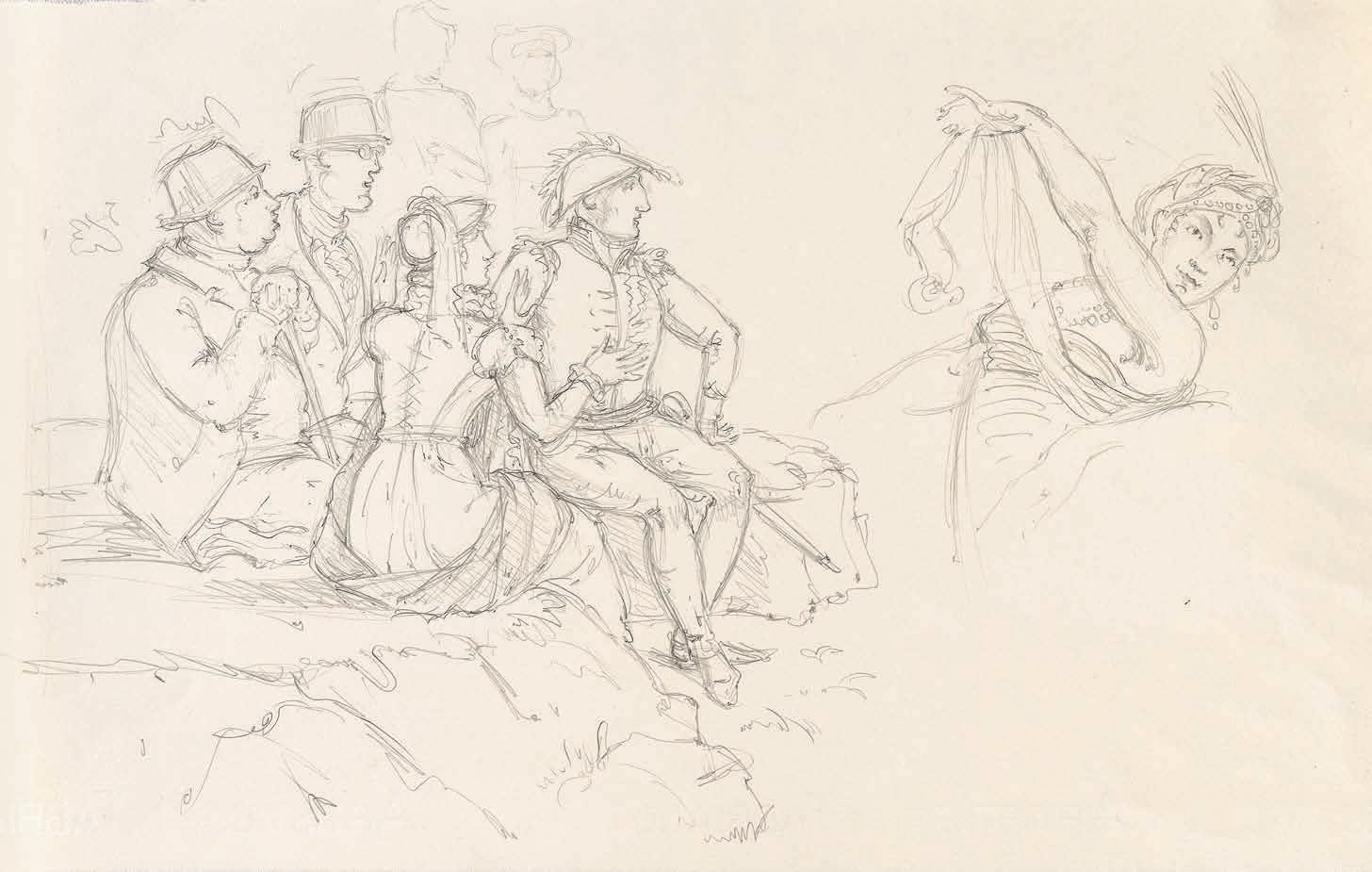

I wonder what these generations of New England women, including the occupants of Corliss-Carrington House, some of them undoubtedly quite proper and upright, thought of this provocative scene. It could hardly be more extreme. The dancers in their revealing spangled costumes leap and pose with alarming vivacity. In this highly racialized rendering, careful attention is given to varied skin tones in the dancers, musicians and the ring of Indian participants. The pink English observers are based on French caricatures. verdressed in a heavily layered, tightly laced outfit appropriate for a cold climate (not India), the Englishwoman is a foil for the evident freedom of the dancers. The officer has a tiny head and the two civilians, one obese, the other emaciated, stare stupidly.

The backdrop of this phantasmagoria is derived from prints in Thomas and William Daniell’s Oriental Scenery. The west gate of the Taj Mahal looms over the right half of the composition while two temples from Bindrabund (Vindavan) make up the left distance. gnoring the fact that these edifices are from different religious cultures and that the spatial construction of the landscape offers no clue of how to travel from one place to another, their basis in the real world lends a misleading credibility to the scene.

This was not by accident. The manufacturers touted the educational value of Grande chasse au tigre in the materials they published to promote the wallpaper. The sensational dancers are even given a gloss of reality: “This scene represents bayadères; or Indian dancers; these women are highly respected in this country; the dances are very voluptuous and even lascivious. In the foreground on the left, an English family is viewing with astonishment a dance by several of these women.” 9

As I reconstructed these scenes in drawing and watercolor, I was drawn into their dreamy, almost hypnotic world. The rapt attention of the circle of viewers surrounding the dancers and the hermetic gestures of the tiny figures wandering around the stage set architecture would have been appreciated by Giorgio De Chirico. The cut and paste process of the designer paradoxically resulted in a convincing visual experience, much the same as in Vues d’Italie.

The watercolors in this series all have a view into the distance indicating the contemporary world beyond the historic interior. In this case the vista is personal. We see Memorial Hall, formerly Central Congregational Church, a Romanesque Revival building designed by Thomas Tefft in 1853. Tefft is thought to have conceived the porch on my house, which is just a few blocks away. My employer, Rhode Island School of Design, now owns Memorial Hall, where I often teach drawing. Closer still, my department, Printmaking, is on enefit Street ne t door to the andicrafts Club and my office is just yards asunder from the wall holding the scene with the dancers. History, with all its unease, may be closer than we think.

the preponderance of scenic papers devoted to armchair travel evoke the colonial world. As we saw in Grande chasse au tigre dans l’Inde,Westerners exist merely as observers. Encountering a French scenic wallpaper populated primarily by the colonizers of the “exotic” setting is disconcerting. When it happens to depict my own country, a historical period I have studied, and places I have seen, my impulse is to point out a thousand perceived inaccuracies in the depiction of social interactions. I eventually admit I have once again been seduced into believing in a wallpaper as a document of something that actually happened. I remind myself that these wallpapers, in common with most works of art, are constructions, not transcriptions of how things actually looked. The primary insights have to do with the original makers and consumers, followed by everyone who lived with, worked in front of, preserved, cared for, collected and responded to these objects, down to myself as I render the wallpapers as they exist today.

. obert P. mlen, mag ining merica in uber s Scenic allpaper ues d m ri ue du Nord, Winterthur Portfolio, Summer utumn, , ol. , No. , pp. 189-210.

. asmine Nichole Cobb, Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century, New ork niversity Press, New ork and London, , pp. .

Vues d’Amérique du Nord was designed by Jean-Julien Deltil and manufactured by Zuber in Rixheim starting in 1834. It has been in almost continuous production ever since. eltil placed five merican beauty spots the ay of New ork, est Point, oston arbor, Natural ridge and Niagara Falls side by side in a continuous strip on a consistent hori on line. The topography was taken from French lithographs by . Milbert published in 1828.10 Deltil effected the transitions between scenes by inserting large rocky hills and trees to create pleasing compositional rhythms when the wallpaper is hung around any given room. e added the figures, dressed from fashion plates advertising the pinnacle of French fashions from leg of mutton sleeves, bi arre headgear for the women and attering light trousers for the men. ost everyone is at leisure, engaged in tourism, showing off brand new finery, carriages and horses. Novelty abounds in the steamships and the rail drawn carriage. eltil eschews timelessness, embracing fashions and trends that would be obsolete within a few years and seem infinitely uaint today. Perhaps this is part of the attraction that made this Zuber’s greatest hit.

first saw Vues d’Amérique du Nord on a hite ouse tour when was in high school. ac ueline ennedy had installed it in the iplomatic eception oom during her decoration campaign. The hite ouse set is certainly the most famous version, but have seen the wallpaper many times since in private homes, clubs, schools and museums. interthur has a detached set that was recently removed from an inn in oungstown, hio, complete with graffiti drawn by diners. From this array of choices selected a private residence in elaware, built in the th century, the wallpaper from a 19th century printing. Legend asserts the rolls were brought from France by an merican soldier after orld ar . t is a superb e ample, installed to take advantage of the beautiful scenery out the windows.

Even as a teenager I found some images in Vues d’Amérique du Nord to be disturbing. already knew that depicting ndigenous people performing ritual dances for tourists was inappropriate. Noticing the frican mericans among the spectators, wondered if such an integrated gathering would have indeed occurred in the 1830s. ventually came to see that several of the lack figures were drawn with e aggerated features and gestures, so was not surprised when scholars identified their source in racist caricatures, published in Philadelphia and London shortly before eltil made his design.11 e see this use of scurrilous images to enhance entertainment value in Grande chasse au tigre dans l’Inde,but, when viewed in light of the racial politics of acksonian merica, eltil s uotations are much more dis uieting.

t first glance, the brightly clad figures populating the foreground of Vues d’Amérique du Nord evoke nothing so much as the chorus of a comic opera bursting into their first number as the curtain rises. rawing individual figures and groups reveals that eltil s stage direction failed to coalesce them into unified action. tomi ed and self involved, they hardly seem to look at the marvelous views dominating the scheme the Natural ridge is right there lthough am sure eltil s intentions were not satirical, cannot help but see a criti ue of fashionable tourism.

Vues d’Amérique du Nord by Zuber, Natural Bridge and Niagara Falls, 2023, watercolor, DETAIL

Figure and furniture study, 2023, graphite, 12” × 22”

Figure and furniture study, 2023, graphite, 12” × 22”

wilmington

to contemporary eyes , the Boston Harbor scene is much more felicitous in its relationships between characters and its narrative tone. The figure types are stockier and scruffier than the stylish leisure seekers populating other scenes. They engage in conversation, active listening, and hard work, shared between frican merican and white laborers. ven if the topography of oston is a bit generali ed, the idea of a lively harbor in the s is convincingly portrayed. ore evocative and mysterious are the two small figures emerging from the rocky woods to the left of the oston scene. They are both frican merican. The woman carries a basket on her head, the man a pack and staff. re they eeing enslavement f so, they are the sole reminder of the political reality of the time when Vues d’Amérique du Nord was made.

13. This wallpaper is a romanticized version of the voyage of Captain Cook. Maori artist Lisa Reihana re-envisioned it in her video installation in Pursuit of Venus [Infected], 2015.

The pictures comprising this visual essay take inspiration from watercolors of domestic interiors made during the 19th century throughout Europe and the Americas. I love this egalitarian, noncanonical art form. Practitioners from all walks of life –women, men, amateurs, professional artists, nobility and not – made drawings to record dwelling places both humble and grand. When viewed in a group, as in the collection assembled by Eugene Thaw now housed at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum in New York, 12 they are utterly charming, vividly bringing to life specific details of a world that has long ceased to exist.

Of course, the development of photography made such representations democratic to the point of saturation. Today, a handmade image of an interior space is less about verisimilitude and more a record of time spent sitting in a room, studying each element and eventually constructing a convincing pictorial container for the depicted items. It is an invention as much as any of the scenes on the wallpapers.

The constant real-world element in these pictures is my presence in the rooms. Much of my time is spent reveling in the brilliant achievements of the artists and craftspeople who preceded me. But the seductiveness of their achievements does not hide those images in the wallpapers that sit uncomfortably at this point in history. Contemplating these works in the rooms and recreating them in the studio counters the impulse to elide or gloss over what was there to be seen ever since the first magnificent and problematic scenic paper, Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique, 13 was released by Dufour in 1804.

The survival of these gigantic works on paper over 200+ years in the face of renovations, demolitions, redecorations and any number of adversities is nothing short of miraculous. Due to their massive size, they are even more vulnerable to destruction than most prints and drawings. Unprotected by collector’s albums, as smaller paper objects were in the past, or solander boxes and light exposure limits imposed by curators and conservators today, they endure. For this I am grateful. French scenic and Chinese hand-painted wallpapers have waited a long time to be seen as more than pretty decorative schemes or marvels of industrial production. They are comple art objects filled with serious content. argue for continued preservation of this legacy. e have no idea what future generations of artists and scholars might find in this work. My own experience: nothing matches close looking in the presence of the actual art.

Andrew Raftery (b. 1962 Goldsboro, NC; lives and works in Providence, RI) is an artist whose work explores both observational and autobiographic narratives of contemporary American life. His artistic practice rests upon a deep expertise and appreciation for antique methods of art-making, in particular, engraving. His precise and labor intensive works demonstrate the enduring relevance and efficiency of this medium’s application on contemporary subjects to disseminate images that are universally accessible. Raftery pools his expansive knowledge and care into his works to create intimate and inventive portraits of his 21st century life using techniques that date back to the 15th century, thus paying homage to the vast history of printmaking in an updated, modern setting. A professor of printmaking at Rhode Island School of Design, his practice is simultaneously heavily research-based as a scholar and collector, as well as both personal and objective: his work constitutes a constant practice of self re ection within his contemporary society.

Previous major projects by Raftery include Suit Shopping: An Engraved Narrative (2002), Open House: Five Engraved Scenes (2016), and Autobiography of a Garden on Twelve Engraved Plates (2016). Each of these works uses the historical tradition of engraving to disseminate the daily intimacies of his private life and conception of the world. The dichotomy between contemporary subject matter and antique medium provides a simultaneous harmony and welcome tension within each project, enabling aftery s study of current definitions of home, family, and the standards of interpersonal interaction.

In 2016, Raftery debuted his own letterpress wallpaper at his solo presentation of Autobiography of a Garden on Twelve Engraved Plates at RYAN LEE Gallery. His deep and thoughtful engagement with wallpapers has ourished since then, resulting in important projects such as his 2019 set of seasonal wallpapers that he installed in his Providence home, and this current body of work.

Raftery received his BFA from Boston University in 1984 and his MFA from Yale University in 1988. He has been Professor of Printmaking at Rhode Island School of Design since 1991. He has earned many awards, including the Winterthur Research Fellowship in 2022, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship

in 2008, the American Academy of Arts and Letters Purchase Award in 2006, and the Louis Comfort Tiffany Award in 2003. He was elected to membership of the National Academy in New York City in 2009 and Print Council of America in 2012.

His work can be found in the collections of Baltimore Museum of Art, MD; British Museum, London; Cleveland Museum of Art, OH; Davis Museum at Wellesley College, MA; Davison Art Center at Wesleyan University, CT; Detroit Institute of Arts, MI; Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, MA; Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University, NY; The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, CA; Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA; RISD Museum, RI; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, MO; Spencer Museum of Art at University of Kansas, KS; Whitney Museum of American Art, NY; and Yale University Art Gallery, CT, among others.

This project started when Stephanie Delamaire suggested I apply for the Maker/ Creator Fellowship at Winterthur. Over 36 days, on intermittent visits, Stephanie and her colleagues, Thomas Guiler, Catharine Dann Roeber, Jackie Killian and Chase Markee made the museum and its collections accessible, patiently accompanying me as I drew in the galleries. I am ever grateful to be part of the Winterthur family.

Rebecca Siemering generously responded to my request to draw in the Handicrafts Club, gave me unlimited time in the rooms and allowed me to arrange objects in their collection. Club members were especially kind to me. We forged new friendships through our shared creative endeavors.

Corliss-Carrington House is an architectural gem that Lorne Adrain and Victoria Huijie Zhu eagerly share with others. Victoria and I drew together a couple of times, something I hope will happen again. Their spirited poodle, BeiBei, was a good sport about posing for two of my pictures.

My visit to Ann and Andrew Rose was full of art, gardens, landscapes and historic places. There was just enough time left after sightseeing to immerse myself in their wallpaper and the objects they let me move from room to room. Andrew is a connoisseur and enthusiast. I have so much to learn from him.

During the many hours I developed the images in the studio, I often thought about these new friends. They may not be visible in the finished pictures, but their presence is palpable to me in the work.

t first, watercolor seemed anomalous in a body of work mostly done in monochrome print techniques, but I was compelled to continue. Eventually Mary Ryan visited my studio and agreed that they formed a potential exhibition. This powerful support is echoed by the entire staff at RYAN LEE Gallery. Above all, I deeply appreciate Ethel Renia’s engagement with my work over the past few years. Her essay reveals a strong voice for her generation.

I have long waited for the opportunity to make a book with Ernesto Aparicio. His deep expertise in typography and design with images is evident on these pages. Ernesto uncovered new ways of seeing my watercolors and drawings.

Ernesto and I were fortunate to draw on the long experience of Danny Frank at Meridian Printing in East Greenwich, Rhode Island. Printed with new digital methods, this book was guided by eyes that have directed the production of some of the finest printing over the past decades. pert photography by rik ould ensured a superb outcome.

My essay was edited by two friends who understand my art and the ideas behind it. Susan Tallman challenged me to find my own voice in discussing some of the difficult subjects in the scenic wallpapers. Prudence Crowther followed by tightening the logic of my arguments. Their sympathetic assistance helped me better understand this project.

Through it all, my mother Annetrude and my brothers Bernie and Terrence were always encouraging and supportive.

Finally, thanks to Ned Lochaya for his humor and stories that form the backdrop of our lives.

This book accompanies the exhibition:

SCENIC MICROCOSMS : Wallpapered Rooms Painted by Andrew Raftery

RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

October 25–November 25, 2023

Printed in an edition of 200 copies at Meridian Printing in East Greenwich, Rhode Island under the supervision of Daniel Frank

Designed by Ernesto Aparicio

Art photographed by Erik Gould

Essays by Andrew Raftery and Ethel Renia

Published by RYAN LEE Gallery

515 West 26th Street

New York, NY 10001

ISBN: 979-8-9864991-2-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023915393

Baltimore Drinking Room, Vues d’Italie by Dufour: Scene I, 2021,watercolor and ink wash, 16” × 14.5”

Baltimore Drinking Room, Vues d’Italie by Dufour: Scene I, 2021,watercolor and ink wash, 16” × 14.5”