the GOING BEYOND THE PAGE

STORIES BEYOND THE PAGE

Lucia Stacchiotti Editor Debbie Nicholas Editorial Board

STORIES BEYOND THE PAGE

Lucia Stacchiotti Editor Debbie Nicholas Editorial Board

The course of the human adventure is unpredictable: this should incite us to prepare our minds to expect the unexpected […] Every person who takes on educational responsibilities must be ready to go to the forward posts of uncertainty of our times. We should learn to navigate on a sea of uncertainties, sailing in and around islands of certainty (Morin, 2001, p. 3).

GOING BEYOND THE PAGE

REGGIO EMILIA AUSTRALIA INFORMATION EXCHANGE

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange Inc. Ground Floor, 1 Oxley Road, Hawthorn VIC 3122

WEBSITE: www.reggioaustralia.org.au

EMAIL: admin@reggioaustralia.org.au

REAIE acknowledges the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation and their continuing connection to country and culture. Our meetings and events take place on ancestral lands and nearby waterways. We pay our respects to the Elders and educators of each nation, past, present and emerging.

@reggioaustralia

Reggio Emilia

As I write this note, I return to Morin’s words, which continue to resonate with my journey — and perhaps with many of ours — as courageous and passionate dreamers across the world. This is our first digital edition, and while I sit with the curiosity and joy of expanding our possibilities, I also sit with the uncertainty that terrifies us as human beings at our very core, especially in these days and years. Can we sit with vulnerability? And, as Pelo and Carter wondered, “how do we begin telling a new story that will transform how we think and work?” (2018, p. 52)

This edition gathers stories of togetherness from the Landscapes of Collaboration Conference and the Mosaic of Marks exhibitions. These stories may illuminate how, even when the horizon is unclear, we can find in one another a dimension of strong collegiality (Giamminuti et al., 2024).

The voices and reflections collected here remind us that education is not about arriving at fixed destinations, but about nurturing the art of travelling together — with attentiveness, aliveness, and a willingness to sit with complexity. In this dimension of persistent movement (Moss, 2014), as transformative change within this open-endedness of continuous we-becoming “direction does matter: it is vital to the process” (Unger, 2004, p. civ).

May these pages invite you, dear reader, to lean into uncertainty not as a threat, but as a space of possibility. May they offer islands of inspiration, while encouraging you to keep sailing into the vast unknown with the courage of solidarity and the curiosity of hope — for, as Moss reminds us, having a sense of direction does not mean knowing for certain your final destination (2014). Times change, but the values that guide our direction remain, and we may ‘just’ learn to co-navigate.

With Care and Gratitude, Lucia StacchiottiDebbie Nicholas Editor Editorial Board

REFERENCES:

Giamminuti, S., Cagliari, P., Giudici, C., & Strozzi, P. (2024). The role of the pedagogista in Reggio Emilia: Voices and ideas for a dialectic educational experience. Routledge.

Morin, E. (2001). Seven complex lessons in education for the future. UNESCO.

Moss, P. (2014). Transformative change and real utopias in early childhood education: A story of democracy, experimentation and potentiality. Routledge.

Pelo, A., & Carter, M. (2018). From teaching to thinking: A pedagogy for reimagining our work. Exchange Press.

Unger, R. M. (2004). False necessity: Anti-necessitarian social theory in the service of radical democracy (2nd ed.). Verso.

So, my portrait in this exhibition honours, acknowledges, and represents all those who work, live, and learn with children and all those who have and continue to share their practice and professional thinking so the rights of children for a just and civil society, for an education that is meaningful, contextual, and authentic can be realized. It is my hope that in this portrait every one of you can see yourselves. My very best wishes to you all.

With gratitude to Semann & Slattery for permission to include excerpts from Jan Millikan’s speech at their Inspire Conference (2025), where the Legacy: A Story of Women Exhibition, was launched.

The Courage to Re-Imagine: Thirty Years of Dialogue Honouring the Landscapes of Collaboration

In the following words that she shared at the 2025 Landscapes of Collaboration conference, Jan Millikan, Founder and Patron of REAIE, offered more than reflection — she shared encounters of memory, gratitude, and vision. Jan's story reminded us that Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange (REAIE) was born of the courage to imagine and the commitment to defend children’s rights and possibilities. As Bruner (1990) invites us to consider, narrative is how we co-construct meaning from experience: knowing where our stories begin helps us to trace the paths they may travel. This article traces beginnings — and extends an invitation forward: to reimagine, together, for children — and indeed, for society.

These educators were prepared to take risks with their work and they courageously transformed what was historically practiced, transforming learning and teaching in their places of education (Jan Millikan, REAIE Conference Speech, 2025).

Hello everyone, and thank you Kate Mount, REAIE Chairperson, for your warm and kind introduction.

It is wonderful to be here with you today and congratulations to REAIE for offering a professional learning event for eight hundred plus people! This is a testament to what REAIE stands for and to REAIE’s purpose and values. Congratulations to all who have worked so hard to make a conference like this possible.

I am honoured to be the Patron of REAIE – an organisation that is deeply important and very special to me. REAIE has a long history of defending the rights of children to quality education, to play and to be respected as citizens from birth. I am grateful to be able to continue to be associated with this extraordinary, national organisation and congratulate REAIE on continuing to

REGGIO EMILIA AUSTRALIA INFORMATION EXCHANGE

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange Inc. Ground Floor, 1 Oxley Road, Hawthorn VIC 3122

WEBSITE: www.reggioaustralia.org.au

EMAIL: admin@reggioaustralia.org.au

REAIE acknowledges the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation and their continuing connection to country and culture. Our meetings and events take place on ancestral lands and nearby waterways. We pay our respects to the Elders and educators of each nation, past, present and emerging.

@reggioaustralia

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

The perceptions and opinions expressed in this journal are those of the contributors.

The material is not endorsed by Reggio Children or the schools of Reggio Emilia.

This digital offering is produced with the aim of promoting and provoking dialogue regarding the challenge of the Reggio Emilia Educational Project.

progress, to pivot during challenging times and for the organisation’s long standing and reciprocal relationship with Reggio Children.

A special hello to Elena, Consuela and Jane from Reggio Emilia – it warms my heart to be with you all here today.

Close to 30 years ago, Janet Robertson, Mary Featherson and I, organised for the Hundred Languages of Children Exhibition to come to Australia. I remember Loris Malaguzzi expressing great concern about this idea, fearful that they would never see the exhibition again, as it had so far to travel. It was at this time, knowing that the exhibition was coming to Australia, that we knew we needed to have a name for our organisation – an organisation that, up until that time, had been more like an informal gathering of friends and interested colleagues in education.

We decided on the name, Reggio Emilia Information Exchange, (REIE) so there might be an exchange of ideas, thinking and understandings. I really thought, at that time, that in a couple of years everyone would have exchanged their thinking and information, and the organisation would unlikely continue. How wrong I was. REIE later became REAIE, to include the name of Australia and the work we started, has only continued to grow.

In 1992 I took a group of twelve interested people from Australia on the first Study Group experience to Reggio Emilia and upon returning, one of the delegates, from Adelaide, suggested we introduce a newsletter, so the delegates could stay connected and continue to learn from one another. This newsletter later became ‘The Challenge’ journal, which continues to be a place of dialogue and exchange.

What I hadn’t realised, when we initiated this organisation, was that this would bring together so many amazing educators who would take up the ideas and principles of the Reggio Emilia Approach® in their learning and teaching with children. These educators were prepared to take risks with their work and they courageously transformed what was historically practiced, transforming learning and teaching in their places of education. I learnt so much from these teachers and educators and began to see with more clarity, what was possible. The work of these teachers, and their willingness and openness to share their thinking and practice, was the catalyst for others to also become curious and to re-imagine and change their practice.

What an honour it is to continue to be part of REAIE, as Patron.

I would like to acknowledge the hard working and dedicated REAIE Committees and Board, over all these years, who have refused to lie down and be defeated when challenges arise – for always finding ways to reinvent themselves and the organisation; for committing to the value and important work of research, and to become a national organisation that defends the rights of children to education, especially in these complex times.

The title of the first, and all subsequent REAIE conferences, has been, The Landscapes of… This conference, entitled The Landscapes of Collaboration, accompanied by the brilliant Mosaic of Marks, Words and Materials Exhibition, offers yet another landscape for our consideration and learning.

I wish you all a wonderful conference experience and I acknowledge your courage and commitment to re-imagine and to work so hard, for the rich possibilities of education for children and indeed for society (Jan Millikan, REAIE Conference Speech, 2025).

This contribution honours the past and present while opening pathways for the future, inviting us all to nurture new possibilities together. It reminds us that courage and imagination remain our companions — and the horizon continues to open, inviting us to reimagine what is yet to come.

STORIES BEYOND THE PAGE

Curated by Stefania Giamminuti

Stefania Giamminuti

VID-20251010-WA0000.mpa

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the Kaurna people and pay my respects to Elders past, present and emerging and any Aboriginal people present here today. I would also like to acknowledge that this book was written in Reggio Emilia (Italy) and on the unceded Country of the Whadjuk people of the Noongar Nation.

Thank you to REAIE for being our unfaltering supporter during this journey, from the generous gift of a grant to fund the translation by the wonderful Jane – and wasn’t that fun! – to this moment, where together we celebrate a collaboration between Australia and Reggio Emilia that has its roots in a conference Jan Millikan attended in the United States in the early 90s, where she happened to choose, among many sessions, the one that spoke of a small city in Northern Italy with delicious food, a proud history of cooperation and resistance, and a brave educational project. I would like to acknowledge that we are all here because of Jan’s generosity and intellect, and that we continue to nurture our bonds of alliance because this organisation, the REAIE, has always believed that alternatives are possible. Thank you to the REAIE Board for your generosity and dedication to worlds of the possible.

Thank you to my co-authors Claudia Giudici, Paola Cagliari and Paola Strozzi, and to our partner Annamaria Mucchi. If I could share with you the recordings of the many Zoom meetings we had as we crafted and dissected this book, debating every single word and going on for hours as the world stopped and changed around us, I am sure you would delight in this collaboration as I have. What a privilege to lead this project, I will never forget it.

Thank you to all those who participated in interviews and meetings for this project, it was a privilege to witness this systemic generosity, artfulness, and dedication to children. Thank you to Reggio Children, to the Preschools and Infant-toddler Centres - Istituzione of the Municipality of Reggio Emilia, to the Pedagogical Coordination, for your warm welcome, enduring collegiality and tension towards research. Reggio Emilia is home.

As I look out on this collective that is gathered here today, I am grateful for the presence of so many of you, treasured colleagues and dear friends who have held me close and cheered me on over these two decades of dialogue with Reggio Emilia, through personal highlights and challenging times. Your thinking and practice are deeply woven into my writing and my work, thank you for your intellectual generosity and boundless curiosity.

We are privileged to bear witness to Reggio Emilia’s dedication to democracy and the common good. The experience of the municipal infant-toddler centres and schools of Reggio Emilia is lived fully, it is entirely pragmatic, and it is enduring; it is made of what Canadian philosopher Erin Manning (2016) calls “minor gestures”. The quality of the minor gesture is to displace the normative and the conventional. As philosopher Brian Massumi says, “minor gestures always have to play the major, subverting, perverting, hijacking, or hacking it” (Massumi, 2017, p. 65). Because they subvert the major, experiences like Reggio Emilia’s need to be constantly defended from within and through broader alliances. Erin Manning cautions that the minor gesture requires “the prudence of the experimenter” (Manning, 2016, p. 7), and she notes that “the register of the minor gesture is always political” (Manning, 2016, p. 8). In this generous space of collaboration and connection to Reggio Emilia, we are all experimenters, and we are all political.

The experience of Reggio Emilia is an example of resistance that has reverberated potential for difference throughout the world, providing a concrete story to counteract the threat

REGGIO EMILIA AUSTRALIA INFORMATION EXCHANGE

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange Inc. Ground Floor, 1 Oxley Road, Hawthorn VIC 3122

WEBSITE: www.reggioaustralia.org.au

EMAIL: admin@reggioaustralia.org.au

REAIE acknowledges the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation and their continuing connection to country and culture. Our meetings and events take place on ancestral lands and nearby waterways. We pay our respects to the Elders and educators of each nation, past, present and emerging.

@reggioaustralia

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

REFERENCES:

Giamminuti, S., Cagliari, P., Giudici, C., & Strozzi, P. (2024). The role of the pedagogista in Reggio Emilia: Voices and ideas for a dialectic educational experience. Routledge.

Manning, E. (2016). The minor gesture. Duke University Press. Massumi, B. (2017). The principle of unrest: activist philosophy in the expanded field. Open Humanities Press.

Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2017). Matters of care: speculative ethics in more than human worlds. University of Minnesota Press. van Dooren, T., & Bird Rose, D. (2016). Lively ethography: Storying animist worlds. Environmental Humanities, 8(1), 77-94. https://doi.org/10.1215/ 22011919-3527731

Curated by Stefania Giamminuti

GOING BEYOND THE PAGE democratic forms of solidarity. We imagine that the educational project of Reggio Emilia, by virtue of the contributions of all those who participate in its livelihood, has significant power of contagion, gesturing into existence the new in other places of early childhood education and care worldwide and building new horizons of hope.

I would like to acknowledge the distress and despair that many in our sector and those who are gathered here today might feel in response to recent events recorded in the news in Australia. I can offer only briefly an invitation to reclaim care. Care generates care. In the words of feminist scholar Maria Puig de la Bellacasa (2017), lack of care “undoes, allows unravelling” (p. 1). And I’d like to read a brief passage from the Preface to our book as an invitation:

We hope our readers will be “drawn into new connections and, with them, new accountabilities and obligations” (van Dooren & Bird Rose, 2016, p. 87), and we put forth an invitation to care, for “care is omnipresent, even though the effects of its absence. Like a longing emanating from the troubles of neglect, it passes within, across, throughout things. Its lack undoes, allows unravelling” (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017, p. 1).

As we trouble the state of early childhood education and care locally and worldwide we ask whether a lack of care might undo us all – children, families, educators, citizens and non-human others together. How can we counter a state of unravelling in our educational thinking and doing, and might collective care as a political, ethical, and affective act – such as in the enduring experience of Reggio Emilia – offer a way for re-imagining our common endeavours? As Puig de la Bellacasa (2017) invites us to consider, “caring here is a speculative affective mode that encourages intervention in what things could be” (p. 66). Our collective witnessing and storytelling bring forth speculations for what things could be, as we energise possibilities for thinking, acting, and resisting in alliance with Reggio Emilia. (Giamminuti et al., 2024, p. xxix)

In their generous endorsements for our book, Peter Moss and Gunilla Dahlberg spoke of its potential to generate hope. Peter Moss wrote: “this book […] contests the impoverished education of the neoliberal hegemony […] it leaves the reader with hope that another world is possible as that hegemony passes” Gunilla Dahlberg wrote that “the book also sends a message of hope and a call for an education commons, which is so important when education systems internationally are experiencing the dissolution of collective action”. In dark and disconcerting times, this book may give hope that something different is possible. If we can offer hope and propel resistance, we think this research project will have overshot its aims.

Now over to you, our readers, and allies. Thank you.

Curated by Debi Keyte-Hartland and Catherine Lee

Debi Keyte-Hartland Catherine Lee

Collaborating in Pedagogical Companionship

Participation in a community that learns-a community of researchers and thinkers bound together by the shared project of inquiry-calls forward and strengthens in us the capacity to be in discourse with all sorts of perspectives. Perspectives that challenge us and perspectives that expand our thinking (Pelo & Carter, 2018, p. 202).

What a pleasure it is to write together! Both Catherine and I found ourselves connected — one from Australia, the other from the UK — through a shared commitment to nurturing cultures of inquiry and learning. We share a commitment to developing cultures of inquiry in professional learning we lead to develop communities that learn together in their collaboration (Pelo & Carter, 2018). Our first encounter was in the UK at the 9th Arts in Early Childhood International Conference in 2023, when we discovered our shared connection and deep commitment to making children’s and their educators thinking and collaboration visible and have been exchanging perspectives, wonderings and questions across distance and time zones ever since. Our collaboration in thinking with each other strengthens our capacity to view our work from new perspectives, expanding and enriching our understandings in diverse and unexpected ways (Pelo & Carter, 2018).

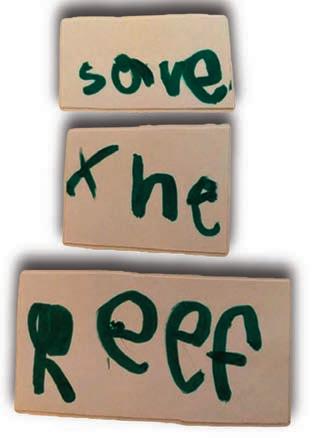

Our collaboration underpinned both our conference presentation at the 2025 REAIE Landscapes of Collaboration conference in Adelaide, and in the writing of this article which unfolded in dialogue. This dialogue remained open to transformation, enabling us to reconstruct theories and coconstruct new knowledge as we moved in our thinking together. Our collaboration created a generative space for critical dialogue about teaching and the impact of it on children’s learning, challenging one another to think-with each other to identify and unpack assumptions, and test out the strength of our individual interpretations of pedagogical documentation arising out of an inquiry at The Point Preschool in Sydney where Catherine was director and teacher. This inquiry focused on an unexpected find in the sandpit in which the children dug up a piece of fossilised coral originating from The Great Barrier Reef, over 1800km away.

This inquiry began when children unearthed a piece of fossilised coral in the sandpit—believed to have originated from the Great Barrier Reef, 1800 km away. Educators engaged in thinking with children, families, the coral, and the wider community, co-constructing understanding within a vibrant relational ecology where ideas evolved collectively (Lee, 2023). Educators listened to the ideas and working theories of the children, took their questions seriously, and co-constructed understanding within a relational ecology where knowledge and shifts in thinking emerged collectively. The coral provoked not only scientific inquiry — how had it travelled so far? — but also empathy and care — how had it become broken, bleached, and hurt?

C:The coral needs cold water, not the warmer water.

Z:When the sea gets too hot, it’s not good for the coral or for the fish and the crabs and jellyfish.

F:I spectacular find came from the same place where Nemo lives. It’s the Great Barrier Reef.

L:The coral doesn’t like warm water but the crown of thorns does and they eat the coral, and the coral dies.

H: When coral gets too warm and too stressed it gets bleached, and we need to invent to invent things to stop this.

This idea of innovating and inventing expressed by H. was taken up by L. who had learned that the warmer waters had encouraged an abundance of the Crown of Thorns starfish which then ate the coral, so he invented a Super-Pincer, which picked up the star fish and put them into a

REGGIO EMILIA AUSTRALIA INFORMATION EXCHANGE

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange Inc. Ground Floor, 1 Oxley Road, Hawthorn VIC 3122

WEBSITE: www.reggioaustralia.org.au

EMAIL: admin@reggioaustralia.org.au

REAIE acknowledges the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation and their continuing connection to country and culture. Our meetings and events take place on ancestral lands and nearby waterways. We pay our respects to the Elders and educators of each nation, past, present and emerging.

@reggioaustralia

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

REFERENCES:

Bahadin, K. (2013). Pedagogical awakenings and self-discovery in the light of imperatives, constraints and opportunities of teaching social studies in Singapore. PLS Working Papers Series, 6, 1–15. National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University. https://repository.nie.edu.sg/handle /10497/14435

Giamminuti, S., Cagliari, P., Giudici, C., & Strozzi, P. (2024). The role of the pedagogista in Reggio Emilia: Voices and ideas for a dialectic educational experience. Routledge. Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Lee, C. (2023). The spectacular find: The joy of possibility and listening to children and engaging in inquirybased projects. Pedagogy+, 14, xx–xx.

Keyte-Hartland, D. (2024). Attending to vitality and liveliness in learning. Innovations in Early Education: The International Reggio Emilia Exchange, 31(2), 8–xx.

Curated by Debi Keyte-Hartland and Catherine Lee

container so that they could be moved safely away from the coral. The children’s creative inventive thinking reflected deep ecological care and a collaborative spirit of love.

Other children soon joined this inventive thinking, offering practical and imaginative ideas to help the Great Barrier Reef protect itself from harm. Ideas included a teaching robot, which would help the coral to calm and regulate itself with breathing techniques and a special kind of underwater watering can which distributed important nutrients that would feed the coral to make it strong. Just as the children and educators thought-with one another, we too found joy in pedagogical companionship — exchanging perspectives, unsettling assumptions, and generating new understandings.

This ongoing dialogue mirrored the evolving inquiry with children revealing how thinking with cultivates joy, growth, and pedagogical renewal, highlighting how collaboration is a dynamic force that transforms practice and deepens our commitment to collective learning. Catherine’s lived experience as an early childhood teacher and pedagogical leader brought authenticity, realness, nuance and the texture of daily practice. Debi’s perspective as an artist-educator, researcher and writer brought new theoretical frames into the playground of thinking with, unsettling the familiar and widening what could be seen. Neither of our roles were fixed; Catherine as educator created theory; and Debi as theorist listened and constructed pedagogy. Together we re-discovered what

Keyte-Hartland, D., & Lowings, L. (2025). Learning to live well together. In Z. Moula & N. Walsh (Eds.), Arts in nature with children and young people: A guide towards health equality, wellbeing, and sustainability (pp. 98–107). Routledge. https://doi.org/ 10.4324/9781003357308-9

Kimmerer, R. W. (2024). The serviceberry: An economy of gifts and abundance. Penguin Books.

Malaguzzi, L. (1994). Your image of the child: Where teaching begins. Child Care Information Exchange, 94(3), 52–61.

Malaguzzi, L. (1993). For an education based on relationships. Young Children, 49(1), 9–12. https://www.reggioalliance.org/wp -content/uploads/2022/05/ education-based-onrelationships.pdf

Pascal, C., & Bertram, T. (2012). Praxis, ethics and power: Developing praxeology as a participatory paradigm for early childhood research. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 20(4), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X .2012.737236

Pelo, A., & Carter, M. (2018). From teaching to thinking: A pedagogy for reimagining our work. Exchange Press.

Strozzi, P. (2024). Dialectical encounters in Reggio Emilia. In S. Giamminuti, P. Cagliari, C. Giudici, & P. Strozzi (Eds.), The role of the pedagogista in Reggio Emilia: Voices and ideas for a dialectic educational experience (pp. 86–126). Routledge.

Curated by Debi Keyte-Hartland and Catherine Lee

Loris Malaguzzi described as a pedagogy of relationship, in this case, not only with children, teachers and families, but with each other as pedagogical companions inviting exchanges of ideas and welcoming our differences in thinking and action as opportunities for learning (1993).

For Malaguzzi, this pedagogy of relationships enacted in collaboration is a powerful antidote to solitary teaching practices, which cause separation and indifference which he saw as a violence that characterised contemporary life back them (1983). We suggest this violence still continues today, as separation fosters division and a lack of empathy—an inability to recognise diverse ways of being in the world. It is why we, as authors are committed to cognitive tensions which provoke and enable shifts in our thinking that move us in our pedagogical praxis and living-inquiry which refuses certainty and closure in knowledge and insists on the collective actions of learning-living together which are open to somersaults in our thinking.

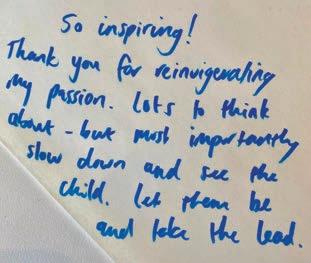

In collaborating on our past inquiry, we resisted the temptation to tell a simple, linear narrative which unfolded the chronological happenings and developments in an overly generalised way. For instance, by simplifying explanations by stating that “the children decided to...” without fully exploring the underlying cognitive tensions which revealed how choices were developed and made during the learning interactions between Catherine and the children. It was in digging into the details of cognitive conflicts, dissonances, and difficulties at play in teaching and learning such as: questioning how decisions were made either by children or teachers; or why specific materials were curated within learning contexts and not others; and what learning processes became evident through examination of pedagogical documentation which illuminated the moments of new thinking which arose that could also be described as pedagogical awakenings (Bahadin, 2013).

The kind of linear chronological narratives we were trying hard to avoid could be seen as warm and celebratory in amplifying a rich image of the child but could also easily fail to reveal the full tapestry of pedagogical interweaving’s that made up the complex relationships within this collective living-inquiry. It is the complex interweaving’s which enable insightful evaluation of the relationship of our teaching and the children’s learning, and it is the digging deep which lay at the heart of the gentle re-negotiations of meaning which led to the moments of surprise and illumination which marked the shifts in our thinking which brought this collective living-inquiry alive. These shifts in thinking differently which emerged in our collaboration (and which continue to disrupt our thinking) meant our teaching was different than what went before and thus was the most valuable form of formazione for us as early childhood educators, pedagogical leaders and companions.

GOING BEYOND THE PAGE

Curated by Debi Keyte-Hartland and Catherine Lee

Confronto 1(Giamminuti et.al. 2024) was also at the heart of our collaborative exchanges of practical and theoretical knowledge which re-examined the process of progettazione2 at play within the preschool’s inquiry with Catherine about their unexpected find. This confronto was shaped by examination of pedagogical traces such as drawings, photographs of models made, ideas of the children that were written down and expressed in group conversation and dialogue. But also, within this confronto was exploration and conversation about what was not documented and not recorded or collated as this revealed the gaps in reconstructing observations of the learning experience which makes shared interpretation of learning processes very difficult. These outcomes of our pedagogical companionship through engaging in confronto could perhaps also be viewed through a praxeological research paradigm, allowing us to reconsider reflection (phronesis) and action (praxis) as a process of examining cognitive tensions while becoming more aware of the issues of power (politics) at play occurring within interactions and surrounding and shaping our interactions, whilst also placing a greater emphasis on identifying and communicating our values (ethics) in our work with children and our continuing reflections on it (Pascal & Bertram, 2012).

For Catherine, this exchange of ideas led to her pedagogical awakening to redefine pedagogy not as a set of practical strategies within an inquiry process focused on children's ideas, but as a form of ongoing participation in collaborative webs that extended and diffused learning beyond the preschool boundary to include families, wider community members, museum experts, and local politicians.

This reconsideration of the theory of pedagogy presented an approach which emphasised humility, joy and response-ability (Haraway, 2016) within a renewed willingness to act together with children and educators in ways that mattered, and which enabled mutual flourishing (Wall Kimmerer, 2024) of all human beings and the more-than-human, even in situations when the path forward was uncertain.

For Debi, a pedagogical awakening for her within this confronto regarded potentia3 – a concept described by Baruch Spinoza (1632 – 1677) as being a kind of collective force within everyone and everything that when activated, creates trust and joyful energy that is powered up when acting collectively (Braidotti, 2019). This potentia became evident when evaluating the way in which children’s motivation increased as they worked together to creatively communicate and raise public awareness (diffusing again beyond the preschool’s walls) through modalities of song and film their collective ethic of care for The Great Barrier Reef

Debi now views collaboration as not only a process of children working together within a shared inquiry but also in the outcomes of that inquiry that intensified within a community to care for the more-than-human world. In this context, ethical and ecological pedagogical practices are vitally important for supporting Kimmerer’s (2024) description of mutual flourishing and the aspect of learning to live well together with nature rather than merely learning in nature (Keyte-Hartland & Lowings, 2024).

In collaborating in preparation for our presentation and in collaborating in writing this article that you are now reading, we experienced further provocations and pedagogical awakenings as drafts exchanged became sites of dialectical encounter (Strozzi, 2024) and their revisions acting as the fuel which ignited our thinking with each other. Our dialogue was at times playful, at other times challenging, but always generative. Across the oceans our thinking with each other as pedagogical companions has intertwined in producing not consensus between us, but a mosaic of perspectives and possibilities. This reminds us that collaboration is not about finding the one best interpretation, but about holding open space to invite diverse ways of thinking and different interpretations into it. These ways of thinking, which can still be in tension can sit alongside one another to enrich the possibilities of our future practices of working with educators and young children.

It is interesting that we now wonder if collaboration is not just a method of working in a participatory way with others, but is an ecology or living system of interconnected ideas and practices which needs others to grow and evolve it - much like Malaguzzi’s metaphor of schools as living, dynamic organisms (1994). In this collaborative ecology, the vitality of early childhood

1 Confronto is an Italian term used in Reggio Emilia to describe the process of sharing personnel perspectives and points of view which enable all to gain the possibility to think differently. It can lead to improvements to both knowledge and action in teaching and is related to participation in a circular process that disrupts hierarchal authority. The circulatory is the encounter between differing perspectives and interpretations of what has taken place with the children. Confronto is a site of exchange in which educators and children are constantly re-elaborating their ideas and points of view in relation to others.

2 Progettazione is an Italian term which is not easily or simply translated into English. It is a term used to describe a process of interpretation of the learning processes of children and adults. It could be seen as being close to the idea of ‘design’ rather than ‘programming’ in which there is possibility for transformation as an attitude of constant reflection in which there is an openness to somersaults in thinking

3 Potentia refers to a concept described by Dutch philosopher Spinoza (1632 - 1677) as being a kind of collective force within everyone and everything that when activated, creates trust and joyful energy powered in group interactions of human beings acting collectively

Curated by Debi Keyte-Hartland and Catherine Lee

GOING BEYOND THE PAGE education emerges, and is characterised by the lively changes and shifts in our thinking (and that of the children) through our learning together in ways which are aesthetic, cognitive, affective, and relational (Keyte-Hartland, 2024).

Collaborating as pedagogical companions has thus broadened our perspectives about what it is ‘to collaborate’ and has fostered a greater intellectual openness to diversity and differences in how we each see the world of teaching and learning. This shared approach has created such valuable opportunities for our growth and learning, encouraging us to renew and transform our practices in early childhood as pedagogical companions with others we work with through consultancy and coaching. By thinking together, we recognise how we can build solidarity even at such distance as ours and continue to evolve within a living-inquiry, much like Malaguzzi’s (1994) metaphor of school as a living system.

So, we share this story of our collaboration, as an invitation for you to think with us about collaboration in your context in its fullest sense. Collaboration not as seeking agreement or consensus and not as a neat and tidy process, but one that is dynamic and messy and occurring in the lively and entangled relationships between children, adults, families, communities, materials, Country and across continents and time zones in which pedagogy can become, as in Malaguzzi’s words “teaching [that] can strengthen learning and how to learn” (1998, p. 83): a shared way of constructing knowledge and understanding that is always provisional and always open to renewal, growth and illuminative pedagogical awakenings.

Collaboration, then, is less about agreement than about courage; the courage to live and learn together in ways that are provisional, unpredictable, and alive. We invite you to join us in imagining these pedagogical awakenings, wherever you are, and to continue weaving the tapestry of possibilities that collaboration makes visible. Our call to action for you as reader is to find someone with whom you can think-with — a pedagogical companion who listens, questions, and ignites your thinking as you explore the processes of children’s learning alongside your own. Such encounters can open new territories of thought and reflection, leading you both to places you may never have reached alone.

When Debi arrived at my home to stay for four weeks, she brought with her a beautiful gift. Deeply connected to The Spectacular Find inquiry, she had slow-stitched a stunning wall hanging for me (Catherine, personal communication, 12 September 2025). A sense of pedagogical companionship emerged through engagement and expression with materials, as we thought through ideas of coral and our own experiences in stitching (Debi, personal communication, 12 September 2025).

Curated by Caterina Pennestri Caterina Pennestri

(Ruozzi & Vecchi, 2019, pp. 12–13)

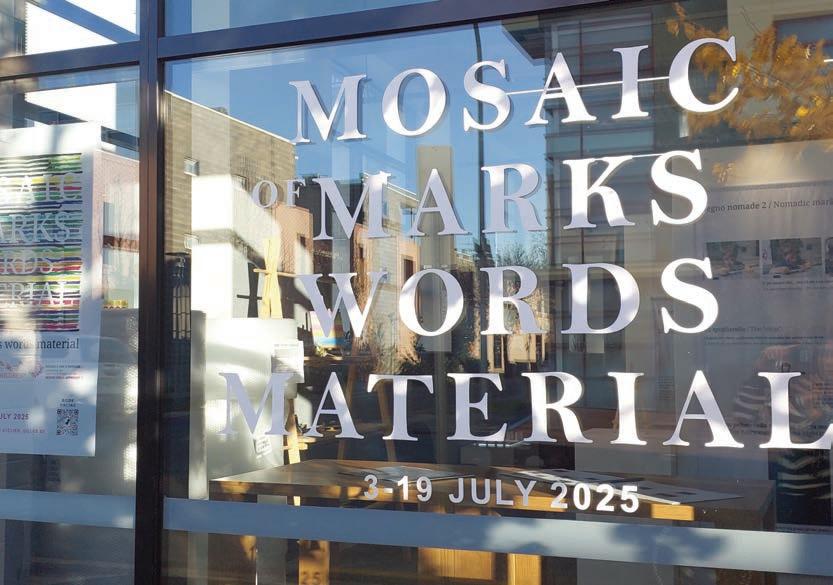

Mosaic of Marks, Words, and Material encountering Australia

For the first time, the Mosaic of Marks, Words, and Material exhibition arrives in Australia—marking a significant milestone in a long and passionate journey.

This exhibition-atelier, born from the research of Reggio Emilia, has been dreamed of, planned, and coordinated by Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange (REAIE), whose commitment to bringing this project to life has been rooted in the values of the Reggio Emilia Approach®.

This dream became reality through the genuine collaboration of professionals across borders, inspired by shared values and a collective desire to create spaces for dialogue around childhood.

This exhibition is a metaphorical la piazza—a space for encounter, dialogue, and shared reflection. Many international le piazze have hosted the exhibition, transforming into landscapes of pedagogical encounters.

Hosted by Reggio Emilia in Asia for Children (REACH) –in Singapore in November 2024, and later in China in January 2025, the exhibition has become a symbol of international pedagogical exchange. In preparation for this journey, our connection with REACH in Singapore was strengthened. In October 2024, four REAIE members attended a professional development program at REACH headquarters, guided by Mirella Ruozzi, Maddalena Tedeschi, and Asia Giannelli. The training deepened our understanding of the pedagogical foundations and historical context of the research. Over four days, we unpacked the research questions, explored the organisational structure, and engaged in rich analysis of spaces, graphic tools, surfaces, and materials. It was a transformative experience that sparked international dialogue and generated anticipation, reflection, and new questions.

The anticipation and preparation for the exhibition for the first time in Australia revealed a profound need: for the exhibition to be nomadic, itinerant—moving across the country to reach diverse communities.

It began its Australian journey alongside the 2025 REAIE Conference Landscapes of Collaboration in Adelaide, enriching the learning experiences of the biennial event. From there, it travelled to

REGGIO EMILIA AUSTRALIA INFORMATION EXCHANGE

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange Inc. Ground Floor, 1 Oxley Road, Hawthorn VIC 3122

WEBSITE: www.reggioaustralia.org.au

EMAIL: admin@reggioaustralia.org.au

REAIE acknowledges the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation and their continuing connection to country and culture. Our meetings and events take place on ancestral lands and nearby waterways. We pay our respects to the Elders and educators of each nation, past, present and emerging.

@reggioaustralia

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

Curated by Caterina Pennestri

Sydney and will conclude in Rockhampton, Queensland, each stop a wish fulfilled, igniting curiosity and motivating educators to reflect deeply on the principles and practices of the Reggio Emilia educational project.

From this emerged the need for consistency and continuity across the Country. Each location, though unique, is connected by the same spirit and values, highlighting the cohesion of a network and the depth of understanding of the research project that inspired it.

The exhibition is also an Atelier, recognising that theory and practice are always in dialogue— inseparable and continuously nourishing each other.

An atelier space for drawing and narration situated within the exhibition as part of the display: this is an interactive strategy that often characterizes the exhibitions created by the municipal infant toddler centres and preschools of Reggio Emilia. It is a choice that underscores how theory and practice are inseparable and indispensable to the quality of the educational experience. The MoM collective and the REAIE network shared many questions that raised from the spirit of research:

•How should we set up the ateliers in Adelaide?

•Which materials could honour the vast and multicultural identity of Australia?

•How could we acknowledge the history and culture of this land while telling the story of Mosaic of Marks’ research?

•How could we design an atelier concept that could travel across the country, sharing both specific identities and common narratives?

GOING BEYOND THE PAGE

Curated by Caterina Pennestri

Mosaic of Marks, Words, and Material tells the story of a research journey from Reggio Emilia, a journey of reinvention and revitalisation of the graphic and narrative languages. It is a poetic dance between two universal languages—drawing and storytelling—where the materiality of the materials becomes both protagonist and inspiration.

Though drawing and words are autonomous languages, for the children’s words and stories, silent or spoken, almost always go hand in hand or intertwine with the drawing, creating an intelligent and often poetic mosaic (Ruozzi & Vecchi, 2019, p. 15).

REAIE’s reflection on the Australian educational landscape led to the creation of organisational structures that would ensure the research was faithfully represented and facilitated across the country. Kirsty Liljegren’s role as coordinator of Mosaic of Mark in Australia has been fundamental, anchoring our work and providing steady guidance.

Maintaining a continuous dialogue with Reggio Children and local networks, REAIE supported the exhibition’s logistics, materials, and spatial organisation. More than ever, the network became a web of bridges—roles, nodes, and people helping one another, sharing ideas, expertise, and resources.

From this collaborative spirit emerged the idea of a dedicated role to preserve the integrity of the exhibition and its values: the Integrity Facilitator. This role ensures the consistency of materials and atelier proposals across all locations, safeguarding the essence of the exhibition and nurturing its pedagogical depth.

The scent of the atelier

It was a profound honour to be invited, as atelierista, to coordinate the organisation of materials and spaces. My role as integrity facilitator has been to ensure that the materials suggested by our colleagues in Reggio Emilia were present and that they embodied the spirit of the research. Equally important was the representation of the identity of each place hosting the exhibition—through graphic tools, surfaces, and materials that evoke the history, culture, and essence of the local context. Colours, textures, and shades were carefully selected to enter into respectful dialogue with the materials used in the palettes of the Reggio Emilia research, creating a new narrative: the story of Mosaic of Marks, Words, and Material in Australia.

The exhibitions mirror the experience from which they arose and in which they arose and in which they are rooted, but at the same time they show what is real, by way of the possible and the desirable (Ruozzi & Vecchi, 2019, p. 11).

The integrity of Mosaic of Marks, Words, and Material lies in its capacity to remain faithful to the pedagogical values of Reggio Emilia while embracing the uniqueness of each place it visits. As Mirella Ruozzi beautifully described, this exhibition is not a static display—it is a living, breathing presence, capable of generating dialogue, reflection, and transformation.

VID-20250703-WA0036

A last-minute change of venue in Adelaide opened new possibilities of collaboration. The beauty of the spaces at Pulteney Grammar School, which offered to host the exhibition, enriching its

Curated by Caterina Pennestri

GOING BEYOND THE PAGE potential and aesthetic. Ali Blake, ELC Director, coordinated logistics between the school and REAIE with grace and operational skill, guided by the principle of thoughtful organisation.

The exhibition layout, designed by Reggio Children in collaboration with Michela Bendotti and REAIE, was followed rigorously. The layout transformed the space into an architectural dialogue, as if the venue had always been destined to host the Mosaic of Mark words and material exhibition.

The Manifesto Table and the Interactive Atelier Table became metaphors of the land—an embracing motherland welcoming diverse cultures, a Mosaic of cultures symbolised by tools and surfaces in dialogue, generating intrecci4, encounters, and interwoven narratives.

The joy and emotion of the first visit by Jane McCall, Elena Maccaferri, and Consuelo Damasi 5remains vivid. Elena’s words: “Sento il profumo dell’Atelier” (“I smell/feel the scent of the atelier”), captured the essence of that moment (personal communication, 3 July 2025). We felt proud that, as a collective and a strong network, we had honoured the values of Reggio Emilia with respect and integrity, while also telling part of our own story. Their advice, and their interaction with the space and materials, has provided an opportunity to deepen our understanding of the Reggio Emilia Approach within an ecological relationship to the Australian educational context.

The network continued to collaborate, supporting the Sydney team in preparation for hosting the exhibition at Marrickville Library Pavilion in August and September.

1 Intrecci (Italian, “weavings,” “intertwinings”) conveys the idea of threads, stories, and relationships woven together — a fabric of encounters and shared narratives at the heart of the Reggio Emilia vision.

2 Jane McCall is the interpreter for Reggio Children and Servizi Educativi of Reggio Emilia; Elena Maccaferri is a pedagogista at the Infanttoddler Centres and the Preschools of the Municipality of Reggio Emilia; and Consuelo Damasi is an atelierista at the Infant-toddler Centres and the Preschools of the Municipality of Reggio Emilia. They participated and presented at the Landscapes of Collaboration conference in Adelaide, 2025 as well as the Mosaic of Marks opening.

3 The Marrickville Library & Pavilion was designed by BVN Architects, winners of an invited design competition run by Marrickville Council in 2011.

4 Intrecci (Italian, “weavings,” “intertwinings”) conveys the idea of threads, stories, and relationships woven together — a fabric of encounters and shared narratives at the heart of the Reggio Emilia vision.

5 Jane McCall is the interpreter for Reggio Children and Servizi Educativi of Reggio Emilia; Elena Maccaferri is a pedagogista at the Infanttoddler Centres and the Preschools of the Municipality of Reggio Emilia; and Consuelo Damasi is an Atelierista at the Infant-toddler Centres and the Preschools of the Municipality of Reggio Emilia. They participated and presented at the Landscapes of Collaboration conference in Adelaide, 2025 as well as the Mosaic of Marks opening.

Curated by Caterina Pennestri

Carefully wrapped, the materials travelled across the country—a precious cargo of possibilities. A vibrant network of educators awaited coordinated by Ruth Weinstein, ready to welcome and set up the exhibition. Their ideas and initiatives inspired and enriched the Sydney installation.

The architectural beauty of Marrickville6 Library and its dynamic community shaped the exhibition’s spaces and materials. The architects who designed Marrickville Library imagined it as a living room for the community, a place where people of all ages could gather, learn, and connect. Sydney’s identity—its coastlines, ocean, and waves—was evoked through graphic tools and surfaces: watercolour shades of aqua, blue ultramarine, and greens; curled materials and pearlescent

Curated by Caterina Pennestri

GOING BEYOND THE PAGE cardboards enriched the Manifesto Table, symbolising the sea, its colours and shapes. A storeroom was transformed into a new atelier, born from the vision of passionate educators who saw the potential of a space inspired by Sydney’s landmarks. Here, graphic language, surfaces, narratives and light danced together, generating transformed landscapes. Natural materials evoking Sydney’s botany across the exhibition’s space, created a dialogue with the urban context.

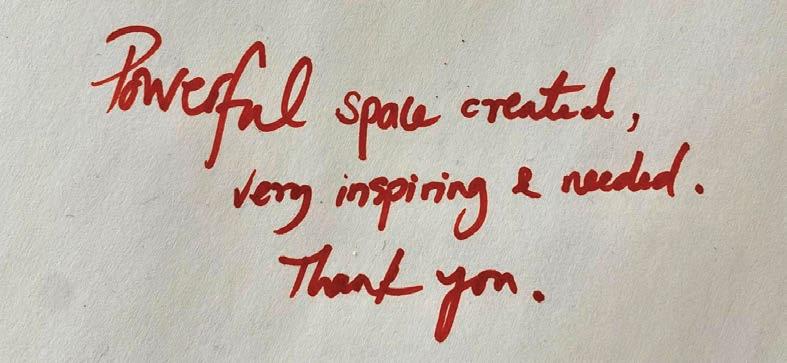

The joy of the exhibition’s openings in Adelaide and Sydney will be remembered as a celebration of collaboration and participation. It was also an act of gratitude to the volunteers—the soul and hands of the exhibition—who ensured that materials and spaces were welcoming to children, families, and educators, and that professional development opportunities were supported with care and dedication.

The learning curve for all of us has been immense—from logistics to social skills, from pedagogical concepts to material research. Mosaic of Marks has truly been a mosaic of learning opportunities. As atelierista, my research into materials connected with the Australian territory and history has been constant and sincere. With deep respect for a country that has hosted me for 15 years, I asked myself:

•How can we avoid tokenism while making visible the complexity of First Nations mark-making techniques?

•How can we honour the intrinsic traditions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, deeply connected to the land?

•How can nature—so wild, rich, and prominent—become a protagonist in dialogue with the cities?

•How can we acknowledge First Nations perspectives, valuing the language of welcome and multiculturalism as defining features of Australia’s current social landscape?

•How can I listen to ideas and perspectives of so many professionals across the country acknowledging and valuing their contribution?

•How can we maintain prominent and protagonist the Reggio Emilia research project?

There were questions, many questions, much uncertainty—but never isolation. The network was always present, a web of support and shared reflection. The research became our answer. The materials told the story. The ateliers came alive through the curiosity of children and visitors. Their explorations, their layers of research, their voices and narrations—activated by the materiality of the materials—spoke volumes.

VID-20250703-WA0035

Curated by Caterina Pennestri

As Atelierista, I re-discovered that the ocean isn’t just blue. I learnt to observe, to deep listen, to slow down, to resist the temptation of rushed answers and stand still in front of my assumptions. The ocean is not just blue—it is green, dark blue, aqua, deep green, purple, white, azure. It holds infinite shades, changing with light, time, and perspective. Perhaps it’s not a discovery, but a rediscovery. I believe every child already knows this truth. They see with eyes unclouded by habit, they know how to feel, listen and really to see.

This way of seeing and not just looking, guided my approach to curating the spaces and materials of the exhibition. Every choice was grounded in research, collective dialogue, and reflection. The intention was to inspire creativity and support the expression of the Hundred Languages—from birth to one hundred years old. Materials were selected not only for their aesthetic qualities but for their capacity to provoke thinking, invite exploration, and honour the poetic intelligence of children. I have re-learnt how to recognise and value the potential of the material.

As we prepare for the final chapter of Mosaic ofMarks, Words, and Material in Rockhampton (10 –26 October), there is a sense of joyful anticipation. The Central Queensland University will host the exhibition, welcoming educators, children, and families into a new piazza of possibilities. The emerging Rockhampton working group coordinated by Heather Conroy, full of energy and commitment, is ready to embrace this experience, adding its own voice to the evolving narrative. Despite the challenges of distance and logistics, the desire to connect, collaborate, and contribute has always prevailed. The exhibition has travelled far, not only across geography but through layers of meaning, relationships, and pedagogical reflection.

And when the last panel is gently rolled down, when the final visitor steps out of the atelier, we will feel a quiet nostalgia—but also a deep pride.

Pride in having honoured the image of the child.

Pride in having nurtured spaces where rights, potential, and research were visible and celebrated.

Pride in having offered something meaningful to our educational landscape in complex times. As REAIE, we have walked this journey with care and conviction, guided by the belief that education is a collective act of hope. The exhibition has not only displayed research—it has been research. It has invited questions, provoked wonder, and created spaces where the Hundred Languages could speak freely.

Curated by Caterina Pennestri

This exhibition has truly been a la piazza. A place of encounter. A place of listening. A place where materials, stories, and relationships have intertwined to form a mosaic—not only of marks and words, but of shared pedagogical dreams.

“To speak to the world about children ‘s infinite wealth of potential, their ability to wonder and investigate, their ability to co construct their knowledge through active and original relational processes: this has always been the primary objective of the exhibit” (Malaguzzi, in Ruozzi & Vecchi, 2019, p. 9).

And though the panels may be packed away, the la piazza remains. It lives in the reflections of educators, in the gestures of children, in the conversations sparked by a colour, a texture, a line. It continues in the networks that have grown stronger, in the questions that remain open, and in the commitment to keep learning together. “We continue to work with tenacious optimism in this perspective of the future” (Ruozzi & Vecchi, 2019, p.11). https://youtu.be/8Cg_U5u4QyM

REFERENCES:

Ruozzi, M., & Vecchi, V. (Eds.). (2019). Mosaic of marks, words, material (2nd ed.). Reggio Children srl.

Curated by Caterina Pennestri

To all the educators, professionals, volunteers, and collaborators who generously contributed their time, energy, materials, and hearts to Mosaic of Marks, Words and Material in Australia— Thank you.

Each gesture of participation—whether through sharing resources, offering support, engaging in dialogue, or simply being present—has been deeply appreciated and lovingly treasured. Your contributions have not only enriched this project but have also helped illuminate the profound beauty and potential of the Reggio Emilia approach in the Australian context.

Together, you have nurtured a space where the rights of children are honoured, their voices amplified, and their expressions celebrated. Through your dedication, you have helped shape an experience grounded in listening, shared learning, and a deep respect for the many ways children think, create, and communicate.

Your commitment has made a lasting impact—not only here in Australia, but as a small and hopeful step toward a world where children’s rights are valued and respected, and their languages recognised, cherished, and embraced.

With deep gratitude and admiration for your generosity and spirit, Caterina Pennestri.

Active Hope is not wishful thinking.

Active Hope is not waiting to be rescued.

[ … ]

Active Hope is a readiness to engage.

Active Hope is a readiness to discover the strengths in ourselves and in others; a readiness to discover the reasons for hope and the occasions for love.

A readiness to discover the size and strength of our hearts, our quickness of mind, our steadiness of purpose, our own authority, our love for life, the liveliness of our curiosity, the unsuspected deep well of patience and diligence, the keenness of our senses, and our capacity to lead.

None of these can be discovered in an armchair or without risk (Macy & Johnstone, 2012, p. 35).

Active Hope is about becoming active participants in bringing about what we hope for (Macy & Johnstone, 2012, p. 3).

I have written a message of gratitude for everyone who collaborated or shared ideas with us for Mosaic of Marks. Although we cannot list everyone by name, I believe it's important to acknowledge and appreciate all the contributions—big and small—that helped bring this project to life (Caterina Pennestri personal communication, September 2025).

REFERENCES:

Macy, J., & Johnstone, C. (2012). Active hope: How to face the mess we’re in without going crazy.New World Library.

Curated by Lucia Stacchiotti

Lucia Stacchiotti

We are all researchers of the meaning of life

The exhibition is like a la piazza — a public square where people gather, connect, enter into dialogues, and feel part of collective stories. It is a space in dialogue with entire communities.

Earlier this month, we carried REAIE into the airwaves through a special feature on 2SER Radio in Sydney. In correspondence with Angus Sharpe (Ingold, 2021), we shared stories from the exhibition Mosaic of Marks, Words and Materials and reflected on the living principles of Reggio Emilia — democracy practiced in the everyday, listening that becomes solidarity, curiosity grounded in research, and joy affirmed as a collective right. The radio format opened a new la piazza-like space — a la piazza within a la piazza — entangled with voices, pauses, rhythms, and curiosity to research.

Together we imagined the exhibition as an ongoing research process, rich with questions: How do children’s marks carry memory, thought, and imagination? What stories do families take away when they encounter these traces?

As Jerome Bruner (1990) reminds us, knowing where we are, where we find ourselves, helps shape identity and belonging. For us, the radio became another way of sitting in dialogue, in community, in hope.

As the conversation unfolded, themes of democracy, participation, and joy were woven through. We recalled that after the Second World War, the citizens of Reggio Emilia literally built their first school ‘brick by brick’ as an act of solidarity and determination to create something different for future generations. In today’s fragile civic climate, Giroux (2005) reminds us that democracy cannot exist without informed and critically engaged citizens. In this spirit, Reggio Emilia’s Approach is not confined to classrooms, but resonates as a cultural and civic practice: defending children’s rights, nurturing curiosity, and affirming — as Malaguzzi insisted — that ‘nothing without joy’. By situating the exhibition in civic places such as Marrickville Library in Sydney, we affirm that education is a common good — that the marks and words of children deserve to live in shared, democratic spaces.

The exhibition is an invitation to continue researching together — research that is part of our human nature. Carla Rinaldi (2006) describes research as a relational and ethical dialogue: a process rooted in listening, solidarity, and the courage to remain open to the unknown. When visitors encounter the marks, the documentation, and the materials, they are not only observing —

REGGIO EMILIA AUSTRALIA INFORMATION EXCHANGE

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange Inc. Ground Floor, 1 Oxley Road, Hawthorn VIC 3122

WEBSITE: www.reggioaustralia.org.au

EMAIL: admin@reggioaustralia.org.au

REAIE acknowledges the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation and their continuing connection to country and culture. Our meetings and events take place on ancestral lands and nearby waterways. We pay our respects to the Elders and educators of each nation, past, present and emerging.

@reggioaustralia

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

Curated by Lucia Stacchiotti

they are becoming co-researchers. In the Reggio Emilia Approach®, the environment is understood as a living organism. Spaces breathe, evolve, and respond to the people within them. They welcome curiosity and cura — a Latin word meaning both care and cure — creating ecosystems of encounters, relationships, ideas, and possibilities.

The hope is that they leave not only inspired, but carrying new questions into their own contexts: What does creative thinking and research look like in my life? How do I listen more closely — to children, to others, to the world?

The Mosaic of Marks is about unfinished stories seeking wider spaces for reflection and collective imagination. It opens possibilities for new perspectives with hope, curiosity, wonder, and joy, because, as Malaguzzi reminded us, nothing without joy. This exhibition also invites us to wonder: what do we carry away from these traces? How might these stories become part of our everyday lives and imaginaries? Time to encounter. Time to wonder. And to wonder. And to wonder. For us, the radio broadcast embodied this complexity and invitation. These moments, these interactions, this exhibition — and even this program — are calls to listen, to pause, to share stories of possibility. Stories that evolve and expand through multidimensional languages, including radio.

Listen back here: https://www.2ser.com/episodes/1756879200

GOING BEYOND THE PAGE

REFERENCES:

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

Giroux, H. A. (2005). Border crossings: Cultural workers and the politics of education (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Ingold, T. (2021). Correspondences Polity Press.

Malaguzzi, L. (1996). The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education (2nd ed.). Ablex.

Rinaldi, C. (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, researching and learning. Routledge.

Curated by Lucia Stacchiotti

The human desire for connection

Lucia Stacchiotti

[…] the human desire for connection, for honour, to be in reciprocity with the gifts that are given you. […] After all, what we crave is not tickle-down, faceless profits but reciprocal, face-to-face relationships, which are naturally abundant but made scarce by the anonymity of large-scale economics. We have the power to change it (Kimmerer, 2024, pp. 92-93).

Reading Caterina’s message of gratitude, selecting images of the Landscapes of Collaboration Conference, adding the MoM acknowledgments messages, I feel a deep sense of gratitude, of reciprocity, of revolutionary re-generation, of desire to connect, share, of offering to each other and the community our uniqueness, our participation. Living this introspective and reflective experience, though images, memories, dialogues, conversations, words, reading, I feel Kimmerer’s vision connecting with ours:

GOING BEYOND THE PAGE

REGGIO EMILIA AUSTRALIA INFORMATION EXCHANGE

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange Inc. Ground Floor, 1 Oxley Road, Hawthorn VIC 3122

WEBSITE: www.reggioaustralia.org.au

EMAIL: admin@reggioaustralia.org.au

REAIE acknowledges the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation and their continuing connection to country and culture. Our meetings and events take place on ancestral lands and nearby waterways. We pay our respects to the Elders and educators of each nation, past, present and emerging.

@reggioaustralia

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

Reggio Emilia Australia Information Exchange

Curated by Debi Keyte-Hartland and Catherine Lee

GOING BEYOND THE PAGE I cherish the notion of the gift economy, that we might back away from the grinding system, which reduces everything to a commodity and leaves most of us bereft of what we really want: a sense of belonging and relationship and purpose and beauty, which can never be commoditised. […] I want to live in a society where the currency of exchange is gratitude and the infinitely renewable resource of kindness, which multiplies every time is shared rather than depreciating with use. (Kimmerer, 2024, pp. 90-91).

I think these words, experiences, ideas, are metaphysical le piazze, spaces where there are intergenerational encounters, where we can simply be in reciprocity, which enriches and make us feel naturally abundant. They remind us that education is about the society of today and tomorrow, it is about crossing borders with curiosity, with reverence, with courage to dare new possibilities for children, for us, for the human and the non-human, locally and globally. To remind to each other that worlding is always unfinished — a holding space for the unknowing and the ongoing, where joy and challenge coexist. Their invitation to dwell with an ethic of enchantment speaks to the same reciprocity that Kimmerer describes — a way of living that honours the gifts of relationship and the slow, regenerative movements of care. In these intergenerational le piazze, learning and teaching become acts of sustained through gratitude, sense of wonder, and an attentiveness to the fragile beauty of our entanglements (Malone & Crinall, 2023) these giants hugs of care-fullness that surrounded us in Adelaide and in all the dialogues and conversations we have been generating as passionate dreamers, deep thinkers and visionary collective.

“The currency of this gift economy is relationship […] This is a gift economy in reach of everyone. It’s subversive. And delicious.” Re-generative economies […] “They invite us all into the circle to give our human gifts in return for all we are given. How will we answer?” (Kimmerer, 2024, p. 105)

Kimmerer, R. W. (2024). The serviceberry: An economy of gifts and abundance. Penguin Books. Malone, K., & Crinall, S. (2023). Children as worlding but not only: Holding space for unknowing and undoing, unfolding and ongoing. Children’s Geographies, 21(6), 1186–1200. https://doi.org/10.1080/1473328 5.2023.2219624

No way. The hundred is there.

The child is made of one hundred. The child has a hundred languages a hundred hands a hundred thoughts a hundred ways of thinking of playing, of speaking.

A hundred, always a hundred ways of listening, of marvelling, of loving, a hundred joys for singing and understanding. a hundred worlds to discover, a hundred worlds to invent, a hundred worlds to dream.

The child has a hundred languages (and a hundred hundred hundred more) but they steal ninety nine. The school and the culture separate the head from the body. They tell the child: to think without hands to do without head to listen and not to speak to understand without joy love and marvelling only at Easter and Christmas.

They tell the child: to discover the world already there and of the hundred they steal ninety nine. They tell the child: that work and play reality and fantasy, science and imagination, sky and earth, reason and dream are things that do not belong together.

And thus they tell the child that the hundred is not there. The child says: No way.The Hundred is there.