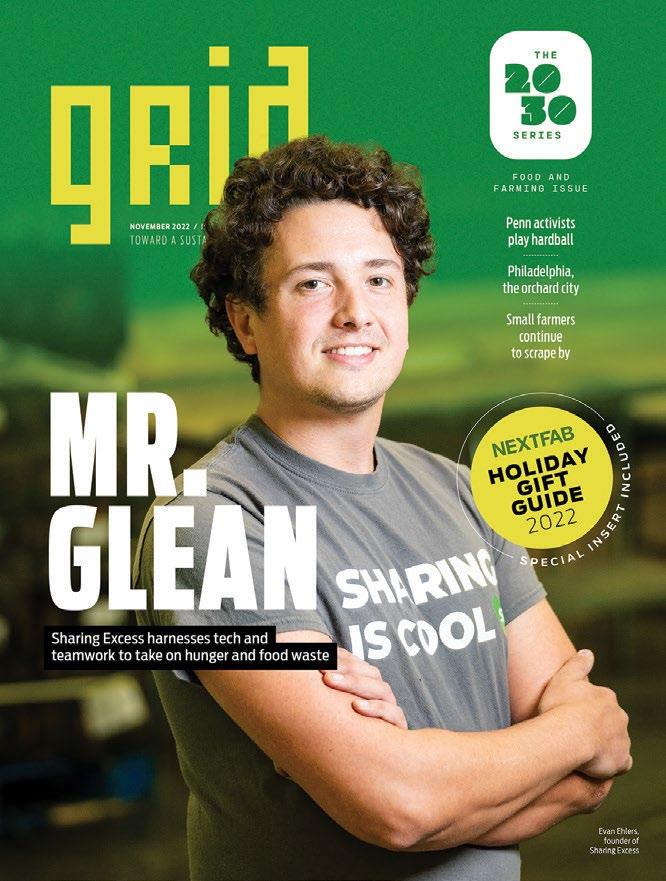

DECEMBER 2022 / ISSUE 163 / GRIDPHILLY.COM TOWARD A SUSTAINABLE PHILADELPHIA PARADISE A slim budget from the City for park maintenance leaves low-income neighborhoods to fend for themselves

■ A round of questions for Circular Philadelphia p. 18 ■ An inquisitive tween launches wildlife nonprofit p. 14 ■ Radical hospitality for the homeless p. 10 THE ECONOMY AND MAKERS ISSUE

Tacony Creek Park in Northeast Philadelphia

Kimberton Whole Foods is your one-stop shop for organic produce, raw dairy, local meats and cheeses, specialty items, baked goods, supplements, body care and more. COLLEGEVILLE | DOUGLASSVILLE | DOWNINGTOWN KIMBERTON | MALVERN | OTTSVILLE kimbertonwholefoods.com ORGANIC LOCAL FAMILY–OWNED NOW OPEN AT THE KNITTING MILLS IN WYOMISSING, BERKS COUNTY 810 KNITTING MILLS WAY | WYOMISSING, PA 19610

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 1 PLAN YOUR TRIP AT ISEPTAPHILLY.COM

publisher Alex Mulcahy director of operations Nic Esposito

associate editor & distribution Timothy Mulcahy tim@gridphilly.com

copy editor Sophia D. Merow art director Michael Wohlberg writers

Kiersten Adams Marilyn Anthony Bernard Brown Constance Garcia-Barrio Dawn Kane Sophia D. Merow Bryan Satalino Lois Volta

photographers Chris Baker Evens Jess Benjamin Troy Bynum Dawn Kane illustrators Bryan Satalino Lois Volta published by Red Flag Media 1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107 215.625.9850

GRIDPHILLY.COM

Going in Circles

It was almost 15 years ago that Van Jones wrote his book “The Green Col lar Economy: How One Solution Can Fix Our Two Biggest Problems,” and not quite four years ago that Alexan dria Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey intro duced the outline for the Green New Deal. The green economy was the holy grail, but now in sustainability circles, we are hearing more and more about a new para digm: the circular economy. The city has a thriving nonprofit Circular Philadelphia, co-founded by friends of mine, longtime Grid contributor Samanthan Wittchen, in terviewed on page 18, and our own direc tor of operations, Nic Esposito. Since these terms circular economy and green econo my are often being used interchangeably, I think it’s worth examining: Are they the same, and if not, what are the differences?

While the circular economy is a new con cept, it’s been practiced in the past. As a child, my dad would buy pickles at the corner store from a barrel, or milk from a milkman who would pick up your empties, which would then be washed and used again. In fact, my father worked for a while as a milkman. So we’re only a generation or two removed from widespread use of these practices and before the rampant use of catsup packets, plastic cutlery sealed in yet more plastic and count less other single-use containers.

The circular economy focuses on care fully using raw materials, and designing for the end of life of the product from the begin ning. When you reach the end of the line for your cell phone, in a circular economy there would be a robust take-back program where the rare-earth elements and other metals are reused, as well as the plastic casing and ev erything else that was used in manufactur ing. There would be few if any leftover parts.

While there might be some waste in man ufacturing, in the circular economy good de sign and mindful consumption can extend the life of everything that is used. For example, the modular design of carpet tiles from Inter face. If your brother spills some red wine on

your rug, you can just remove the square it’s on and clean it. In the event you can’t clean it, you only need to replace one square and not the entire carpet. Genius, right?

Look around whatever room you are in and imagine what it would be like if everything were designed to be dismantled and reused and not destined for the landfill. It’s a very exciting engineering and design problem to consider and the possibilities are tantalizing.

Back to the aforementioned Van Jones book to discuss the green economy. The two problems alluded to in the subtitle are cli mate change and economic inequality. At its core, the green economy is an attempt to con tinue to grow our economy, but inclusively and with low-carbon emissions as the goal. It revolves around energy efficiency and re newable energy, and solves those problems through creating jobs for communities that have long been disenfranchised.

There’s a lot in our current society that needs to be transformed. When I look at our cover image, a tire floating in Tacony Creek, I imagine how the circular economy could address that problem. If that used tire had value, and/or if it could easily be dropped off wherever it was purchased, there would be no need to dump it in a public park. Imagine what the landscape would look like there and everywhere in the city if waste were greatly reduced or eliminated.

But I think we have to keep our eye on eq uity as well. The green economy has a set of values key to our survival, and they should be mirrored by our local government. A low-carbon future needs lots of parks, and a city that cares for them.

So while the circular and green economies are not identical, they are certainly compati ble and complement each other. Dig into the solution wherever you like.

ILLUSTRATED PORTRAIT BY JAMES BOYLE • COVER PHOTO BY TROY BYNUM 2 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022

EDITOR’S NOTES by alex mulcahy alex mulcahy , Editor-in-Chief

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 3 OPEN WEDNESDAY-SUNDAY 8am to 4pm Enjoy Fresh Air, Beautiful Scenery, and Great Wholesome Food with your friends and family! Regatta Room available for rental 1 Boathouse Row • 215-978-0900 cosmicfoods.com EDUCATION THAT MATTERS Offering a holistic, experiential and academically-rich approach to education that integrates the arts and the natural world every day PRESCHOOL THROUGH GRADE 12 | KIMBERTON.ORG 610.933.3635

A Fond Farewell

Volta’s

In 2018 I wrote a zine called “Don’t Deny It, You Need a Self Help Manual on How to Be Clean.” I wrote it as a cheeky way to establish some ground rules or an understanding of domestic behaviors with any new cleaning clients. I also started to send it out to magazines and radio stations, hoping to gain some traction on thinking about the home in a new way.

To my delight, Grid Magazine contacted me in hopes to write an article about my busi ness and cleaning philosophy! It was so nice to have Grid reporter Claire Porter over to my home, show her around and talk about how my business is a feminist cleaning company that directly undercuts the systemic pres sures that predominantly fall onto women. She wrote a beautiful piece about me in the

June 2019 issue of Grid (#121).

This led to an extensive and bubbling con versation with Alex Mulcahy about being a writer for Grid . I started my “Dear Lois” column the very next month and have been writing each month for the last three years. The column was also a great creative outlet for me to draw and make illustrations.

As this year comes to an end my time with Grid has also come to an end. There are so many things on the horizon that I want to tell you about and I hope that we can con tinue in the dialogue we have been having about domesticity, equality, sustainability, and establishing a loving home.

If you liked my column, you’ll love my book, “Confessions of a Cleaning Lady,” which is coming out at the start of 2023. The

book is a collage of the Grid columns, my radio show musings, and workshops that I have given over the years. It also has my com pany’s cleaning manual to add some hands-on knowhow. You can pre-order a copy by going to my web site thevoltaway.com.

I’d also love it if you followed and listened to my radio show/podcast “The Everyday Feminist.” Me and my co-host, psy chologist Dr. Stephanie Heck, dive into matters of the head, heart and home through a feminist lens.

“The Everyday Femi nist” aims to expose and explore the dynamics of gender inequities that play out in the home so that everyone can be equally productive and feel equally satisfied with our domestic and relational lives.

“The Everyday Feminist” airs live weekly on Sundays from 5-6 pm on G-town Radio in Philadelphia. It can be heard on the air at 92.9FM, online at gtownradio.com, and on most podcast platforms.

I am also here for you in your home! If you have been on the fence about what di rection to take your home, need a strategy or just want to make your home more fluid and sustainable, let’s talk!

I am truly thankful for Grid for giving me a forum to write about the home and the sys tems that play in it. I am sad to say goodbye, but I am so excited to keep connecting with you! Thank you for being with me on this journey. ◆

lois volta is a home life consultant, artist and founder of The Volta Way. Send questions to info@thevoltaway.com.

4 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022

As Lois

time writing for Grid comes to an end, many more exciting projects are in the works

ILLUSTRATION BY LOIS VOLTA

PORTRAIT BY JAMES

THE VOLTA WAY by lois volta

BOYLE

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 5

Critical Care

Mission Relief brings the power of CBD products to Weavers Way

When manny jose and Devon McCardell met in 2010, they dis covered two things in common: both were grappling with anxiety and neither was finding relief in conventional treatments (e.g., SSRIs).

Over the next decade, the friends kept in touch, doing their own separate research on the therapeutic effects of cannabidiol — or CBD, as it’s commonly known — the non-psychoactive component of the hemp plant. As an Army veteran who was running two daycare centers, Jose could certainly re late to McCardell’s stress level working as a nurse, especially during the pandemic.

Over time, as the pair discussed their use of CBD to manage anxiety, they agreed that there were varying degrees of effectiveness and consistency among the different CBD products they were consuming. Most of their products were produced many states away from their homes in South Jersey. But with marijuana laws changing in New Jersey — it was legalized for recreational use in 2022 — they decided it was time to research how they could bring CBD to the Garden State. In 2021, they became business partners and launched Mission Relief Therapeutics.

Reflecting on the name, Jose explains, “Putting CBD products out there for people is a number one mission to me.”

Today Mission Relief produces products such as elixirs that incorporate the healing effects of mushrooms (non-psychoactive), elderberry and turmeric. They even have an entire line of dog and cat products: McCardell reported that the “agility chews” were one of the top sellers. As Jose explained, dogs, cats and humans all have what’s called a “can nabinoid system” that, when activated with

CBD, can be extremely successful in reducing ailments like inflammation, which is why the agility chews are so popular for older dogs.

And for older humans or any person dealing with chronic pain, Mission Relief’s variety of muscle creams are a top seller at the Haddonfield Farmers Market, where Jose and McCardell focus not only on mak ing a sale, but also on educating the con sumer on the healing properties of CBD.

“Someone that has issues with their wrists or hands tries our stuff at the mar ket,” Jose explains. “By the time they walk around to the other side of the market, they’re coming back and are like, ‘Wow, like this stuff makes my hand feel great.’”

Jose is proud that the hemp he buys from Estelle Farms in Estell Manor, New Jersey is grown using fair labor practices, and that no additives are used to extract the hemp, but he’s also impressed with the use of both

indoor and outdoor growing space.

“You are enjoying all the benefits of grow ing outdoors such as a bigger yield and a hardier plant with thicker roots,” Jose ex plains. “But also you’re in a greenhouse that’s able to control the climate and in such a way that they produce the best product.”

As Jose acknowledges, this isn’t just an other product Weavers Way is putting on their shelves. It’s an investment in Mission Relief. For McCardell, she has full confi dence in Weavers Way to advance Mission Relief’s dual mission of sales and education.

“I can’t say enough good things about Chris Mallam and Nicolette Giannantonio from Weavers Way Next Door [Wellness Shop],” says McCardell. “They really help people in their store who come to them, tell them what their problems are, and they sit there and listen and give them the best rec ommendation they can.” ◆

6 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022 PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022

Putting CBD products out there for people is a number one mission to me.”

manny jose, co-owner of Mission Relief Therapeutics

sponsored content

Mission Relief founders Manny Jose and Devon McCardell are always willing to talk about the benefits of

using CBD.

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 7

Team Effort

On the trail of America’s pioneering ornithologists

by bernard brown

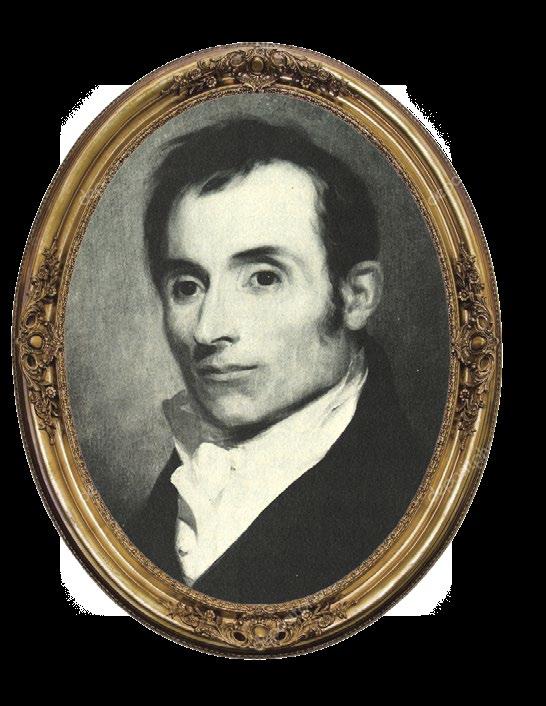

On a frigid January morning I made a pilgrimage to the grave of Alexander Wilson, the so-called “Father of American Ornithology,” at the Gloria Dei Church cemetery at Christian Street and Columbus Boule vard in South Philadelphia. I didn’t know exactly where it was, but the old cemetery is small, and in about five minutes I had found a tall and clearly inscribed granite stone that offered a brief biography, be ginning with “ This monument covers the remains of Alexander Wilson, Author of the American Ornithology … ”

I hadn’t heard of Wilson until a few years ago when I started spending a lot of time with birders. When he came up in conver sation, I noticed that birders often tacked on his popular title, as in, “I got a tat too of a belted kingfisher on my leg. It’s the drawing by Alexander Wilson, the Father of American Ornithology.”

Haven’t heard of Alexander Wilson? You could be excused. You might have encountered birds named after him, like Wilson’s warbler (a pretty yellow bird with a black cap), but, unlike John James Audubon, there are no national envi ronmental organizations named after him, no towns or guidebooks.

Wilson started off as a weaver and poet near Paisley, Scotland, and likely would have stayed there his entire life if he hadn’t writ ten poems criticizing how local mill owners were treating their workers. Finding himself suddenly unemployable, he immigrated to Philadelphia in 1794. He settled into a career as a school teacher, ultimately running a oneroom schoolhouse at Gray’s Ferry.

Philadelphia wasn’t just the capital of a

new nation: it was also the cap ital of American scientific exploration.

Wilson soon met William Bartram, the explorer, natural ist and nursery owner, who mentored him in his study of birds. By 1804 Wilson had decid ed to compile a comprehensive guide to the birds of his adopted country.

He succeeded, though he worked himself to death in the process. Wilson crisscrossed the land to study birds and collect (shoot) specimens to draw. He traveled on the cheap, which often meant walking hundreds of miles. In 1810 he covered 720 miles on the

Ohio River from Pittsburgh to Louisville on his own, in an open rowboat he named Orni thologist. The hard travel and intense effort of writing the nine-volume work, marketing it and hand-coloring the printed drawings took its toll on his health. In 1813, at age 47, he died of dysentery, leaving behind seven finished volumes of the landmark “Amer ican Ornithology.” (His friend George Ord completed the final two volumes based on Wilson’s notes and drawings.)

Wilson’s masterpiece had the misfortune of being followed about 15 years later by Audubon’s gorgeous “The Birds of Ameri ca.” While Wilson’s birds were carefully de tailed representations, Audubon’s look like

8 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022 urban naturalist

Alexander Wilson (portrait far left) traveled great distances to collect and document North American bird species.

Wilson’s comprehensive work included scientific drawings, such as the Carolina Parakeet (opposite page).

Wilson’s work was largely eclipsed by the more vibrant depictions by John James Audubon (this page).

they’re ready to fly out of the page. Wilson placed one Carolina parakeet (now extinct) above three warblers (then called flycatch ers) with its wings slightly open. In Audu bon’s version, seven parakeets twist, flutter and crane their necks to reach cockleburs, a favorite food. You can feel the commotion and chatter of the flock in action.

“What [Wilson] was trying to do was have a way for people to recognize different birds, so his paintings were more in the league of what you’d have in a standard field guide,” says Keith Russell, program manager for ur ban conservation for Audubon Mid-Atlantic. “I think Audubon eclipsed his fame because of the glamor of his paintings.”

While Audubon is unsurpassed as an artist, Wilson remains better respected as a scientist, someone who collected bird speci mens, gave them scientific names (though of course these birds bore indigenous names for thousands of years before that) and de scribed them in writing.

“They’re both great writers, but the dif ference is that Wilson is telling the truth,” says Matthew Halley, curator of birds and mammals at the Delaware Museum of Na ture and Science.

Halley has looked into Audubon’s sci entific accomplishments and found that he most likely made some of them up, includ ing his claim to have discovered an eagle he

called the Bird of Washington. Audubon’s reputation has also suffered due to his own ership of enslaved people and his support for slavery as an institution, leading the Audubon Naturalist Society (a Maryland group distinct from the National Audubon Society) to change its name to Nature For ward in 2021

Wilson himself might not deserve his “Fa ther of American Ornithology” title. His men tor, William Bartram, had himself collected several new species of birds. Wilson also col laborated with Charles Willson Peale, who ran a museum on the second floor of what is now Independence Hall. Wilson donat ed many of the birds he collected to Peale’s museum. In turn he used many of Peale’s specimens to produce his own work. So phonisba, Peale’s shotgun-wielding daughter, collected many of the birds in the museum and organized them in the exhibits by their relationships to each other. It turns out that American ornithology has a mother as well.

It only seemed fair to visit Sophonis ba Peale’s grave. I found it in West Laurel Hill Cemetery, with her married name, So phonisba Peale Sellers, listed on a low grave marker along with her husband Coleman Sellers. The stone in no way indicates that someone who played a key role in the sci ence history of our country rests beneath.

“I think there’s something to the fact that our culture idealizes and idolizes rugged individualism so much that we distort our history by elevating one or two individuals above anyone else,” Halley says. The Peale family, based in Philadelphia and operat ing a museum, can seem less exciting than a man who scoured a continent in search of new species, but they were no less import ant. Like all scientific enterprises, ornithol ogy was and is a team effort. ◆

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 9

Radical Hospitality

Through life-stabilizing services and treating guests with dignity, Broad Street Ministry meets great need by constance garcia-barrio

In 2005, Bill Golderer, then pastor of the Presbyterian church at 315 S. Broad Street, ripped the pews out of the sanctuary to create a big dining room bathed in light from stained glass windows. That move helped thrust the his toric limestone church, now Broad Street Ministry (BSM), toward radical, inclusive hospitality. Today, BSM offers, among other services, free hot lunches Monday through Friday to up to 400 guests each day, many of them living in extreme poverty.

“I know what it’s like to live on the streets,” says Donald Williams, 60, BSM’s associate culinary director, who fell in love with cook ing while preparing meals for his grand mother’s church in the shed kitchen of her North Philly home. “Coming in off the street, you’re looking for a home-cooked meal, for [being treated with] dignity,” says Williams, who takes pride in cooking from scratch us ing organic, locally-sourced ingredients. “At BSM you’re relaxed. You’re family.”

For guests, the meals often provide a gateway to transformative programs.

“Today, Broad Street Ministry has be come the region’s most creative social ser vice organization for people experiencing deep poverty,” says Laure Biron, 38, BSM’s CEO. “We provide life-stabilizing services to more than 7,000 guests a year,” she adds, noting that BSM enjoys a wide base of sup port through individual donors, foundation grants, a few small contracts with the City and fundraisers.

BSM’s community shapes its program, Biron says. Its mail service, begun in 2008, grew from a guest needing a secure address to receive a package. In 2018, BSM distribut ed 154,120 pieces of mail to guests, according to that year’s annual report.

“BSM gives me a mailing address,” says Lucretia Tanksey, 49. “I put in an applica tion for housing. I’m here today to check [if there’s a response].”

Besides determining key services, guests influence how services are delivered.

“Recently, guests talked about traveling long distances to check their mailboxes only to find them empty,” Biron says. “Now they can call in ahead of time and ask if they’ve received mail. We don’t open the mail, of course, but we can tell them what’s in their box.”

Clothes take priority too. Staff members help guests find the kinds of items they like in BSM’s clothing boutique, “almost like having a personal shopper,” Biron says. More than 5,000 guests selected items from

concept of radical hospitality was a big reason Laure Biron joined Broad Street Ministries as the new CEO.

the boutique, which relies solely on dona tions. In addition, volunteers mend guests’ clothes on Thursdays.

BSM also offers personal care items and distributes them discreetly. Guests tell staffers privately what they would like, be it underwear, socks, deodorant, femi nine hygiene supplies or other necessities. Guests then receive the requested items in an opaque bag for confidentiality.

The ministry extends its reach with a hygiene truck packed with personal care

10 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022 city healing

The

products. “We go to several locations each week,” says Shahid Guyton, 47, restorative services director, who adds that the truck made the rounds during the pandemic. “Toothbrushes, diapers and other items of ten cost more than many people have. Being a formerly homeless man, I can recall how receiving hygiene products helped me feel human,” says Guyton. “In the future, I hope to take the truck to more locations.”

Working in tandem with other local groups, BSM offers housing assistance, public benefits, reentry services, legal help and more. Through a partnership with Philadelphia FIGHT, a comprehensive healthcare organization, guests can receive primary medical care, Biron notes, while caseworkers and peer specialists are on hand to remove any administrative barriers such as insurance coverage.

BSM owes much of its success to a safe, welcoming ambience, the staff feels.

ARK OF SAFETY: LGBTQ+ SHELTER

Former BSM staffer Tatyana Woodard, 34, offers radical hospitality to some vulnerable Philadelphians.

“In 2021, I cofounded the Ark of Safety, a shelter for LGBTQ+ in North Philadelphia, with Bishop Romaine Gibbs, of the Next Level Revival Church,” says Woodard, a community affairs manager with Mazzoni Center, which offers health services and programs for the LGBTQ community. “I was sending my [Mazzoni] clients to City shelters, and they’d come back in tears. They were misgendered, mistreated and sexually assaulted.” Studies by the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law echo those outcomes. “They preferred to sleep on the street.”

“Ark has 12 beds and provides food, clothing and training in life skills,” says Woodard, a Black transgender woman forced to leave home at age 16. “We’re just a drop in the bucket. More funding is needed.” Once people have housing, issues like preventing AIDS and STIs can be addressed, Woodard explains.

To donate, visit gofundme com/f/phillys first trans focused lgbtq plus safe haven

“We don’t have security guards,” Biron says. Instead, BSM relies on a de-escalation team to cool down disputes. “Everyone who works here is trauma informed and has completed trainings in behavioral health.”

Besides formal training, de-escalation specialists like Guyton have street savvy. “If someone is upset about a situation, I tell them, ‘I know exactly what you’re going through,’” says Guyton, who was homeless for 12 years and is now a homeowner. “Estab lishing rapport can make a difference. Also, if you know that two guests sometimes clash, you steer them away from each other. I want to be a beacon of hope for guests. I love this work. It feels like a calling to me,” says Guy ton, who got married at BSM in 2019.

Accommodating a range of guests also distinguishes BSM, Biron points out. “We have the capacity to work with people who are having extraordinary symptoms,” says Biron, a psychotherapist and visual artist. BSM takes it a step further. “At times guests with difficult behaviors are barred from some places. We work with those places to have guests admitted again so they can receive services they need.”

BSM makes the most of its location on the Avenue of the Arts by folding creativity into its programs. Members of the Philadelphia Orchestra guide guests in composing songs and expressing themselves through music on Music Mondays. Staff members from the Wilma Theater give poetry workshops. Philly documentary filmmaker Glenn Holsten worked with guests to make firstperson shorts as part of “Voices from Broad Street Ministry,” available on YouTube.

With the holidays, a time of welcome and warmth, BSM plans to bump up its hospi tality even more. The annual Concert for

Coats, featuring seasonal favorites played by the Philadelphia Wind Symphony, will take place Thursday, December 16, from 6:30 p.m. to 9:30 p.m.

“No tickets are needed, but we encourage audience members to donate a gently used coat or winter gear like beanie-style hats, stretch gloves or backpacks,” Biron says. “I also hope to find a useful gift for our guests. One year we gave out boots, but it’s important to have a large enough quantity for everyone. Many guests have lived with scarcity. We don’t want to exacerbate that.”

Chef Don, for his part, will provide guests with “a traditional family-style holiday meal” during the week before Christmas. Given that menu, volunteers who serve meals may find themselves busier than ever.

“I love what I do here,” says volunteer Deidre Bernstein, 59, of Center City. “I get 10 times more than I give.”

Amid the season’s celebrations, Biron reflects on the ministry’s direction and challenges.

“We could do so many things, so we have to ask ourselves about our highest and best use constantly,” she says, “and it’s a peren nial challenge finding resources to make it possible to meet great need with abundant provisions.”

Ultimately, optimism about not only BSM but the future of social services citywide prevails.

“We sustain a … [hope] that one day this practice of hospitality will be pervasive,” Biron says, “and no longer considered a radical act.”

To learn more about Broad Street Min istry, which welcomes volunteers and do nations, visit broadstreetministry.org or call (215) 735-4847. ◆

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 11 PHOTOGRAPHY BY JESS BENJAMIN

Broad Street Ministries associate culi nary director Donald Williams knows what it’s like to live on the streets, so he goes the extra mile for guests.

program.

Hope Floats

Skiff construction builds STEM and carpentry skills while promoting connection with nature

Before boarding a 12-foot Bevin’s Skiff on the reservoir at the Discovery Center at the end of last school year, Northeast High School student Christopher Medina had never been on the water. “I never realized how awkward it was to row, sitting with your back to the front. We did sometimes mess up and did go in circles a lot,” he says.

Medina, then a 10th grader, took part in Philadelphia Waterborne, a program in which Glen Foerd (an organization based at

by bernard brown

a park on the Delaware River at the northeast edge of Philadelphia) partners with Outward Bound and local schools to teach students carpentry while practicing math and phys ics through the building of a boat. This year students at Chester’s Toby Farms Intermedi ate School and Philadelphia’s Lincoln High School, W. B. Saul High School and Northeast High School will be assembling boats, using a design called the Bevin’s Skiff

The Bevin’s Skiff is a simple rowboat designed to be built as a learning exercise.

The students who take part in Philadelphia Waterborne assemble the boats from wood parts produced at Glen Foerd. “Our car penters are making the kit, cutting pieces to size, then the kits are transported to the school,” says Trent Rhodes, assistant direc tor at Glen Foerd.

“I had absolutely zero experience with carpentry before the program. I actually didn’t even know what a sander looked like before then,” says Manar Albahadly, who, along with Medina, helped build two boats at Northeast High School last year. “I absolutely loved putting the pieces of wood together and watching them turn into a boat. It was like a blind puzzle where I was slowly putting pieces of it together without looking at the overall picture because I was so engrossed with the pieces themselves,

12 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022 COURTESY OF PHILADELPHIA WATERBORNE water

High school students have found a great sense of purpose and achievement through the Philadelphia Waterborne boat building

and then I looked at it one day and boom! It’s a literal boat!”

Dirk Parker and his daughter Nia in struct the students as they put the boats to gether, starting by nailing the sides to pieces at the front and back, filling in the frame, attaching the bottom, and then adding in terior woodwork including the seats. “The great part is that some of the technique re peats itself, like the way they do something they do it again, so it’s a great way to teach it,” Dirk says.

The Northeast High School boat builders constructed two skiffs in 2021. Building the boats meant following a plan with careful precision. After the woodwork, though, the students set their minds to the creative task of painting the boats. “After the boats were all done being built, we got to painting, and in this part the students were given full con trol,” says Albahadly.

The students painted one boat in the red and black colors of the Northeast High School Vikings, while the other was a little more freeform, with splashes of color and

environmental symbols.

Philadelphia Waterborne gives many of the boats away to local parks and nonprofit organizations. After more than six years of boat building, with multiple schools per year, the Philadelphia Waterborne skiffs have found their way onto the water, includ ing at Bartram’s Garden, where boaters can take them out during their Saturday free boating sessions during the summer. “If you have rowed in a boat with paint on it there, that’s one of our boats,” Dirk Parker says.

Andrew Adams, co-director of Project SPARC at Northeast High School, worked with the kids to integrate the boat building program into a broader environmental and

watershed curriculum. “The kids’ reaction was ‘How cool is it to build a 12-foot boat and take it out on the water?’ Of course to give the kids access to the water is so im portant. It’s not just the science of rowing and physics, but also getting them out on the water and connected to nature,” says Adams.

Not all the students were ready to trust the boats they had built. “A lot of them were scared,” Adams said. “‘We just built this boat. Are we sure it’s going to work?’”

Medina had no such doubts. “I was sure that nothing would happen. We took a lot of time building it and I was proud of the work we put into it.” ◆

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 13 COURTESY OF PHILADELPHIA WATERBORNE

Students from the Philadelphia Waterborne program rowing on a boat they built.

I absolutely loved putting the pieces of wood together and watching them turn into a boat.”

manar albahadly, Northeast High School student

If noah raven, founder of Monarch Defenders, dashes from plant to plant in his pollinator-friendly garden with the kinetic energy of a 12-year-old, there’s good reason: he is one.

Raven’s Monarch Defenders website rivals that of any big-budget nonprofit. Complete with a mission statement, educational facts, resource citations, ways to take action and an interactive map showing the locations of member gardens across the country, he offers

up a variety of conservation tools. Under the microhabitat link, for example, he provides tips for how to “ditch your lawn,” dishing out advice on selecting native plants, dealing with aphids and deciding whether to grow milkweed from seed. Raven, who considers writing a recreational activity, created the website in a few months.

During a chat in his family’s backyard, Ra ven points out wild visitors including a Coo per’s hawk, a red-headed woodpecker and a

rabbit. Although he has always cared about environmental issues, a family trip to the Piedra Herrada Monarch Butterfly Reserve in Mexico with his mom, Carolyn Kousky; his dad, Francis Raven; and his little broth er, Nate, 7, stirred a passion. Raven speaks quickly when he describes seeing his first real-life migration. “It was so amazing! There were floods of butterflies. We’d researched it, but it’s a lot more beautiful in real life.”

Raven came home from that trip in Feb ruary, did his research on monarchs and built the website. His grandmothers lent him financial support for his Squarespace fees and proofread the website’s content. By May it was up and running. The site now includes native plant lists for every region in the United States and one for Eastern Canada. “Noah doesn’t think small. He goes deep,” his mom says. And “he’s more focused on ecology now.”

His parents, who homeschool Raven and his brother, encourage integrated learning. His father Francis describes what it’s like to teach his son. “Whatever Noah is interested in he is really interested in. Homeschooling has allowed him to really deeply focus on those interests. I’m just lucky to be there for the ride. I try to stay two steps ahead of his knowledge base, but that takes a lot of work!”

The learning projects that Raven and his family take on tend to branch out. For example, during the pandemic, geography studies led to family dinners based on spe cific countries. They’re up to 150. And Ra ven has been keeping a vegetarian diet since reading a book on factory farming.

According to Francis, Raven’s interest in monarch butterflies also evolved from his previous passions. When he was about 7 he became very interested in archaeology. Af ter deep research on the subject and several international trips, Raven was fascinated by Native Americans and other indigenous peoples. He took a special interest in their stewardship of the land. At the time, Raven and a friend were also involved in a yearlong climate change project. These twin interests led to the family trip to see the overwintering site of the monarchs.

“We do lots of projects,” his mom Carolyn says. Raven’s mom, a writer and researcher at the Environmental Defense Fund, helps extend the learning with efforts like reduc ing their use of single-use plastics and in creasing the wildlife habitat in their yard.

14 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022 PHOTOGRAPHY BY DAWN

KANE

STEWARD LITTLE Twelve-year-old launches nonprofit to save butterflies by building one microhabitat at a time story and photos by dawn kane

Noah Raven and his mom Carolyn Kousky use their backyard to build pollinator garden habitats for migrating Monarch butterflies.

Not one to shy away from difficult real ities, Raven says he channels the bad stuff into action. For example, along with some Monarch Defenders friends, he recently met with United States Senator Bob Casey of Pennsylvania to lobby for the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, which has strong bipartisan support and may be passed be fore the legislature’s winter recess.

However, his number one priority is to persuade people to cultivate microhabitats, either in backyard gardens or in pollinatorfriendly containers.

“Planting milkweed is the most import ant thing because it’s the only plant mon archs will lay their eggs on,” Raven says. Scientists attribute the decline of monarch populations to the use of herbicides and the loss of milkweed and forest habitats. Raven explains that there are two monarch popu lations: the eastern population, which has declined by 80% in the past 30 years and travels from the northeastern side of the United States to central Mexico, and the western group, which overwinters in Cali fornia. The western population has declined more than 99% and is close to extinction.

When asked what he does when things seem too bleak, Raven explains that his process usually begins with writing. “It’s really depressing, the level of extinction,” he says. But he enjoys writing poems, essays and stories. In fact, he recently had a letter to the editor published by the Sierra Club.

According to his parents, Raven’s interest in writing isn’t all that surprising since both of them write. His mom writes research and policy analysis, including a couple books, and his dad has been writing poetry since high school.

Outside of his parental influence, Raven looks up to environmentalists like Greta Thunberg. “I like how she’s so young, but she doesn’t give up. She’s so determined,” he said. “People should listen to kids because we’re the generation that is going to be im pacted. All of my friends are passionate.”

For straight-up fun, Raven reads fan tasy books and throws seed bombs. Since September, Raven has amassed an im pressive collection of seeds. To make his seed bombs, he mixes them with compost and clay before locating suit able spaces to throw them. “I’ve been seed-bombing the Meadows,” he said. He has joined forces with South Philly Mead ows activists and co-led a seed-bombing

expedition in the areas that had been torn open by earthmovers.

Hope is the key driver for Raven, so he’s always on the lookout for positives. He de scribes the wonder of planting the family’s pollinator garden and then having butter flies show up almost immediately. He smiled thinking of the neighbor who turned their front lawn into a pollinator habitat. “It’s so amazing!” he said. “Even small actions can make a difference.”

Raven’s current endeavor is to get his par ents to turn more of their backyard over to the pollinators, but it won’t be that difficult. They love the idea. ◆

For more information on how to help monarch butterflies, visit the Monarch Defenders website and follow Raven on Instagram @monarchde fenders, where he posts ideas on everything from butterfly holiday decorations to pro tips for col lecting milkweed seeds and making seed bombs.

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 15

People should listen to kids because we’re the generation that is going to be impacted.”

noah raven, founder of Monarch Defenders

Butterfly milkweed is an important native plant for both Monarch butterfly habitat and sustenance.

SMALL BUT MIGHTY

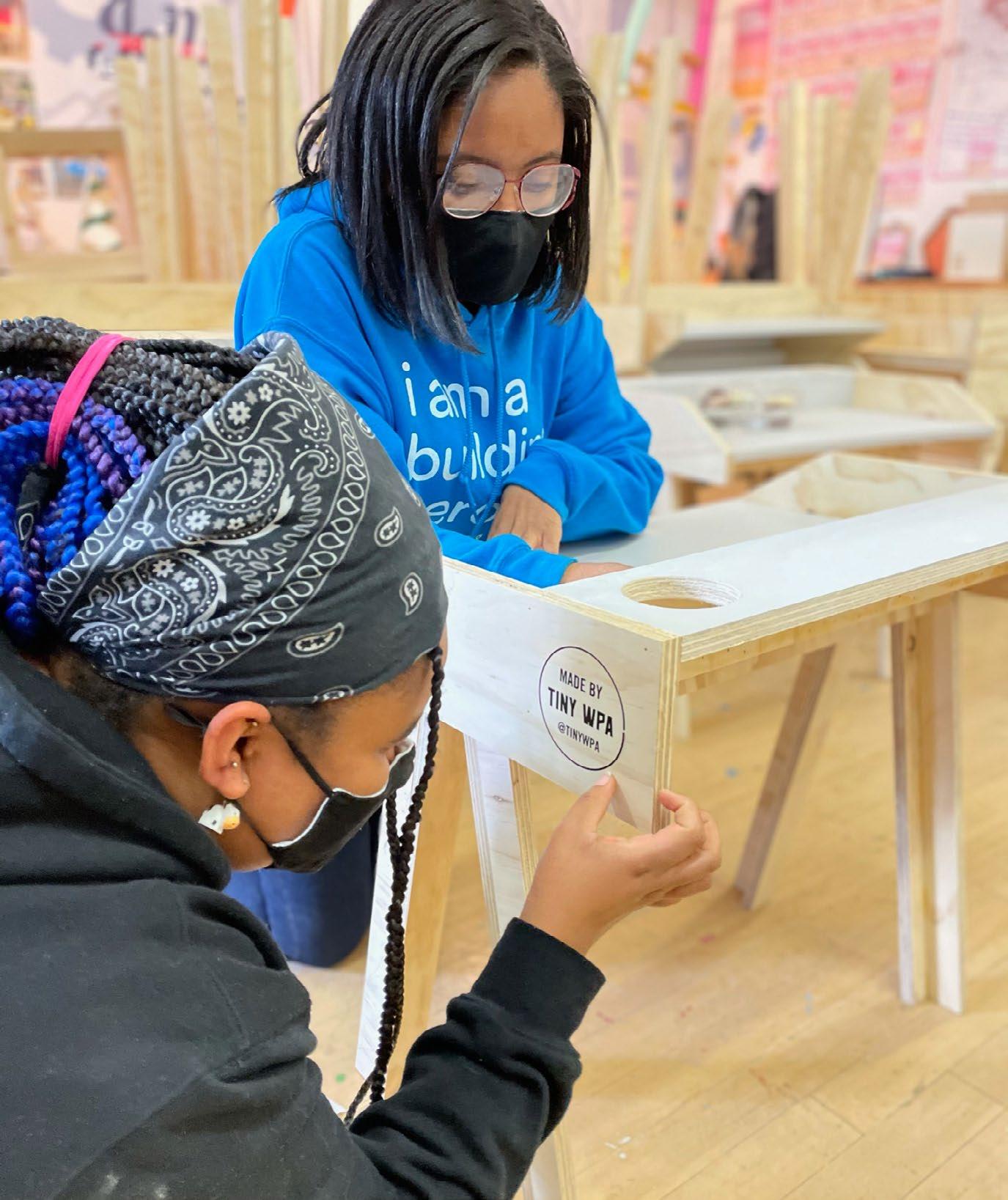

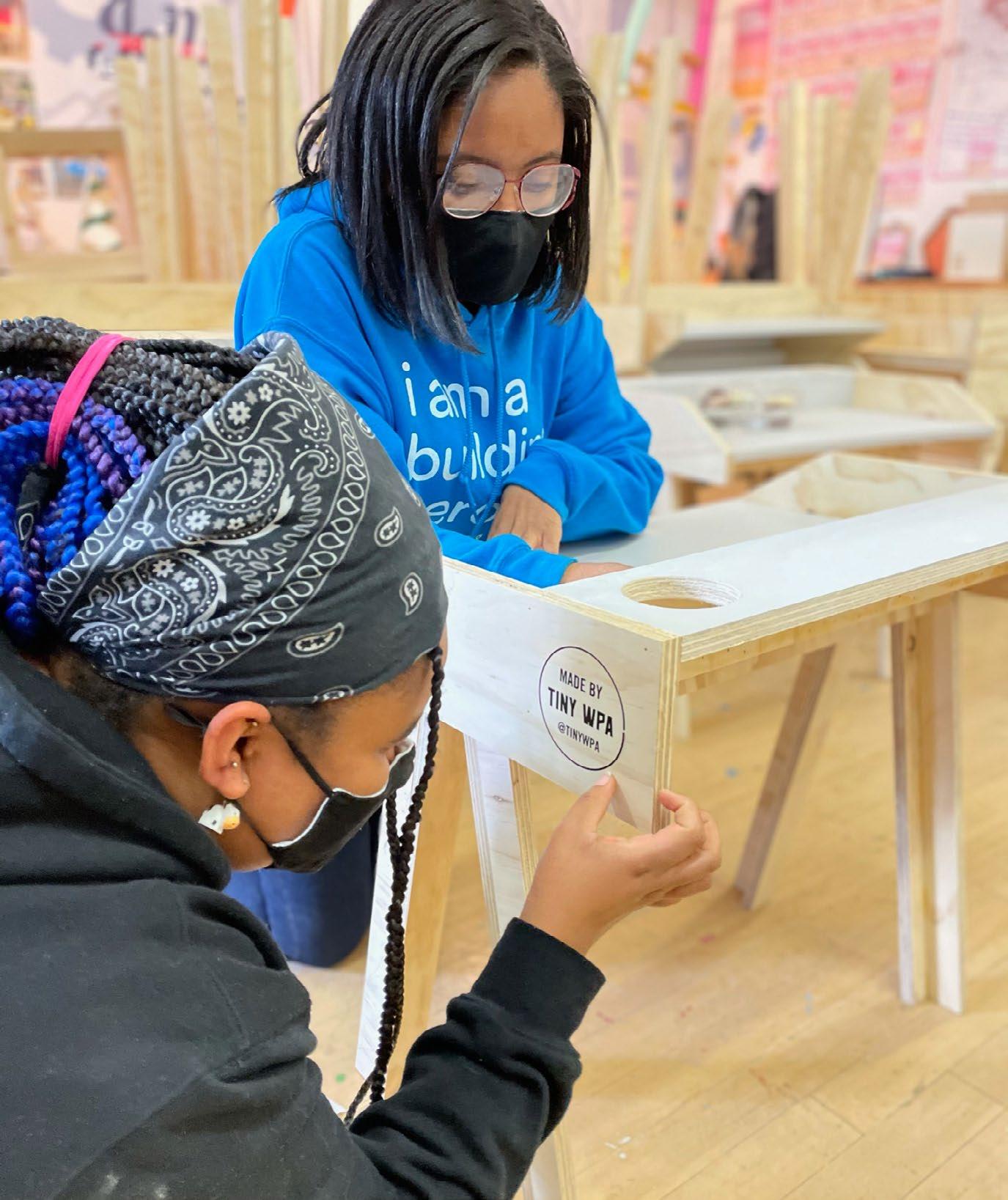

Philadelphia nonprofit uses innovation and creativity to support makers to impact their communities

story by kiersten adams

Taped onto the front wall of a small office and studio in West Phil ly are a plethora of colorful pages marking locations throughout the city. Some places are easily recog nizable, like Belmont Plateau or Mill Creek Playground, while others are lesser known community gardens and empty plots of land. To an outsider, it may look like a ran dom list, but to the builders and designers at Tiny WPA, these spots are promising opportunities for neighborhood care and development.

Established in 2012 by Renee Schacht and Alex Gilliam, the local organization aids in revitalizing Philly through communally built projects. Examples of their work in

clude pop-up play-sets, bus stop benches, flower beds and awnings for community gardens. Tiny WPA encourages residents to design and build for the betterment of their communities. “One of our core beliefs, at least in regards to building and design education, is to simply start with the basic need,” says Gilliam, director of design and learning, who goes on to emphasize that Tiny WPA isn’t building for the heck of it, but to create something of need for — and with — residents. “If it’s not for the commu nity, it’s not [worth it],” Gilliam says.

Through hands-on initiatives like their Building Hero Project, a free innovative program that teaches residents of all ages the basic knowledge of building, fabrication

and design, Gilliam and Schacht are creat ing, as they describe, the next generation of change agents who can utilize their skills for the city’s benefit and for their own career development. “When we are working with our smaller internal team and building he roes, there’s the direct community bottom line, but then there’s also the workforce de velopment side of it where you have 14- to 42-year-olds who are getting paid to learn how to fabricate and lead those projects,” Gilliam says.

Tiny WPA’s aim to address the needs of the community resulted in a sharp turn with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Gilliam and Schacht were asked if they could make desks to accommodate the new work-at-home reality. “I think one of the beauties of working here is you’re working on a lot of different projects,” Schacht says, “and projects change, but in this case, it was a solid six months of [knowing] what you’re gonna do … you’re going to keep mak ing desks and stools — and that’s it!” The result of that time: 800 desks and stools built for students homeschooled during the pandemic.

While the Tiny WPA mission is very practical, it requires considerable creativity. Tiny WPA uses reclaimed materials such as old lawn signs and lumber, and that re quires flexibility when building. Gilliam and Schacht have fostered a team of cre atives who explore art, culture and mean ing through function. “Our favorite times are when we create something together that none of us would have created alone. That’s innovative, that meets a need, that equals skills and empowerment and leadership and hopefully jobs,” Gilliam says. “That’s just utter joy.” ◆

COURTESY OF TINYWPA

Tiny WPA strives to engage diverse makers from the community to collaborate on their projects. Below right: Tiny WPA installed this nature-based playset made from reclaimed materials at FDR Park.

COMPOSTING

Back to Earth Compost Crew

local

CAFE

businesses ready

MASSAGE

Residential curbside compost pick-up, commercial pick-up, five collection sites & compost education workshops. Montgomery County & parts of Chester County. First month free trial. backtoearthcompost.com

The Random Tea Room

A woman owned co-working cafe that seeks sustainability in every cup. Our tea and herbal products are available prepared hot or iced, loose leaf & wholesale for cafes and markets. therandomtearoom.com

Root & Branch Bodywork

Sports massage & therapeutic bodywork to enhance performance, optimize recovery and keep you moving! Only natural, nontoxic, hypoallergenic products are used. Book online at rootandbranchbodywork.com

GROCERY

Kimberton Whole Foods

A family-owned and operated natural grocery store with six locations in Southeastern PA, selling local, organic and sustainably-grown food for over thirty years. kimbertonwholefoods.com

BOOK STORE

Books & Stuff

Multicultural, Afrocentric books, gifts, and surprise packages for all! Founded in 2014, and recently online only at booksandstuff.info and teespring.com/ booksandstuff-stuff

BIKE SHOP

Trophy Bikes PHL

COMPOSTING

Mother Compost

Woman-owned composting company providing service to the Main Line & educational programs for those looking to compost at home. Interested? Find out more at mothercompost.com

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 17

In Center City! Since 2003, Selling + Servicing BROMPTON FOLDERS, and now the new Brompton ELECTRIC. *ALSO: The BEST selection of BICYCLE BELLS on the East Coast. @trophybikes to

serve

TOP OF MIND

LET’S GET CIRCULAR

A new nonprofit works to shift our economy from linear to loop

interview by sophia d. merow

interview by sophia d. merow

Grid spoke in October with Sa mantha Wittchen, director of pro grams and operations at Circular Philadelphia, which she cofounded (with Grid’s Nic Esposito) in June 2021. Circular Philadelphia aims to drive the growth of a thriving circular economy in Greater Philadelphia through advocacy, education, infrastructure development and collaboration.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is the circular economy? The circu lar economy reimagines our current takemake-waste system as a continuous loop where everything that we do from making goods to using goods to disposing of goods has waste basically engineered out of it. Natural systems operate on a circular ba sis. The circular economy tries to replicate that in a manmade environment. We used to have these sorts of things in practice. We had the milkman. We had a much more ro bust repair industry. The circular economy

hearkens back to those kinds of models and systems and seeks to apply them to every thing that we touch and use on a regular basis.

Why is it important to move toward a more circular economy? We live on a planet that has finite resources and finite space, and we simply cannot keep consuming resources and then throwing them out, putting them in the ground or burning them and creating greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change. We will reach our planet’s natural limit. And so we need to find ways to reuse and recycle the resources that we already have here and to reconsider what waste ac tually is. It’s not truly trash, but raw mate rial for the next process of making things.

How does Circular Philadelphia hope to spur this transition? Our theory of change is that first you set the policy conditions that level the playing field and, if you can, incentiv ize circular practices and operations. And then, once you have that, you do education and outreach not just to individuals about

18 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022 BETWEEN RIVERS

Samantha Wittchen mingles with members and partners at Circular Philadelphia’s launch party in June 2021.

the need for the circular economy but also to the businesses and organizations that can then use these new policies to either expand what they’re doing, change their operations, or even set up new lines of business. And then once you’ve done that education and outreach, it leads to market transformation in a way that’s large-scale and thoughtful and has all of the right in frastructure in place.

Circular Philadelphia currently has three market focuses: built environment, food systems and textiles. Why did you start with these sectors? We really wanted to find a way to accelerate what we knew was already happening here. There was some really great work already being done in the built environment and food systems and, to a lesser extent, in textiles. So it made sense to look at where some groundwork had already been laid. The second reason was that when you look at the things that touch people’s lives every day, these were the three obvious areas. Everybody has to live somewhere, in a building; we all have to eat; and we all have to clothe ourselves.

What are some accomplishments you’d like to highlight from Circular Philadelphia’s first year? In July of 2021 we were able to work with the Philadelphia Health Depart ment to update their regulations to allow Philadelphia food businesses and restau rants to offer reusable containers by right to their customers. Prior to us getting the regulation changed the Health Department said that food businesses and restaurants were not allowed to offer reusable contain ers for takeout or to-go, and if you wanted to do it you had to seek a variance and you had to pay $255 per location. That was our first big policy win.

In the built environment focus area, we realized that we needed to find a way to get more contractors and developers to look at using deconstruction as an alternative to demolition. We worked with the Depart ment of Licenses and Inspections to under stand what they allowed for. We took all this information and made a series of informa tion sheets and resources available and have now started doing outreach. Global build ing products manufacturer Saint Gobain, whose North American headquarters is in Malvern, got in touch with us and said, “Hey, this is part of our mission, and we

would really love to be able to partner with you to figure out how we grow this decon struction sector.” So they decided to become a sponsor of Circular Philadelphia. It’s go ing to be a way for us to scale our work in the built environment.

One more—the landscape firm OLIN has a really cool process to turn glass back into sand to be used in horticultural and green infrastructure projects. We helped them apply for an EPA Small Business Innova tion Research grant to commercialize this process. We’ve been working with them to help them secure a site in Philadelphia to be able to collect this material for processing, as well as the actual demonstration site off Kelly Drive where OLIN is using this mate rial in partnership with Parks and Rec on a land restoration project. This could be a real game changer as far as how sand is sourced for infrastructure projects.

What are some concrete actions Grid read ers can take to advance the circular economy cause? There’s a ton of stuff that you can do as a resident of Philadelphia or the surrounding area. We developed a “Zero Waste at Home Resource Directory,” and it basically gives you all of the different busi nesses and organizations that can help you move to a more circular lifestyle at home.

As far as advocating more broadly for cir cular practices within the city, we would love it if Grid readers all reached out to their district councilperson and said, “Hey, this is a really important thing for me, we need to be moving in this direction as a city, and we want you to make the circular economy a priority in policy and in practice.”

What are you excited about as 2022 is drawing to a close? I’m really interested in seeing how our mayoral race starts shaping up. We’re talking about putting together a platform for what we think needs to hap pen as far as how the City manages waste and materials that we can shop around to mayoral candidates and say, “Hey, are you willing to sign on to this?” I’m looking forward to having this conversation in a more public sphere, about thinking about our waste differently in the city of Phila delphia and thinking about it as raw mate rials that we can actually make use of. I’m really looking forward to that conversation heating up and becoming part of the larger conversation that we’re having about who the next mayor will be. ◆

For more information, see “Let ’s Get Circular,” Circular Philadelphia’s year one progress report.

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 19 SAMANTHA WITTCHEN

Samantha Wittchen created this illustration to show people how the circular economy flows.

After nine years working for a nonprofit organization, 41-yearold Erin Mattson was earning more seniority, more responsibil ity and more money than she ever thought possible. But she also experienced stress and anxiety levels that led to seri ous health problems. Her partner, Elissa Viscelli, 36, convinced her to quit her job

because, far more than a second income, Viscelli said, “I need a happy wife.”

Post-COVID stories about the changing workplace abound. The Great Resignation. Quiet quitting. Worker shortages. The rise of “solopreneurs” and gig workers. Patri cia Blumenauer, vice president for opera tions and data at Philadelphia Works, Inc. workforce development board, adds to

these trends longer life expectancies, post poned retirement and generational shifts in attitudes about work. Blumenauer says, “COVID opened up the eyes of workers a bit more to what their options might be, what their capabilities might be and where they might have more power than before.”

Other forces have been reshaping the work world for years. Maura Shenker, in her recent role as director of Temple’s Small Business Development Center (SBDC), cites the dete rioration of unions and a lack of job security. She feels that norms in the business commu nity drifted away from a stakeholder focus to a shareholder focus with an emphasis only on profit maximization. As a consequence, she believes, “people are time poor and mon ey poor and feel powerless at work.”

We may be at a critical juncture when the balance of power between employers and employees is tilting. Blumenauer de scribes workers who are “looking for more and less.” More money, higher titles, more responsibility and prestige, but less time in the office in a rigid 9-to-5 sense, less struc ture in the work environment and even less supervision. It’s a tall order that addresses a small segment of the workforce where only predominantly white-collar jobs can be done flexibly.

In Philadelphia, employers and workers face daunting challenges around opportuni ty and access to living-wage jobs, especially when remote or hybrid work is not an option.

“Philadelphia: Executive Summary of Economic and Demographic Trends 2021,” a study released by Philadelphia Works, analyzed 2019 United States Census Bureau data to uncover sobering statistics about our workforce. Even if you’re aware that Phila delphia is the poorest large city in America, this report has the power to shock.

While our city of 1.5 million residents is home to 131,900 households with annu al incomes of $100,000 or more, 237,900 households earn less than $35,000 annu ally. Within this group, 75,600 households have incomes less than $10,000. To put this number in context, it is equivalent to every family in Northern Liberties’ 19123 zip code, or Chestnut Hill’s 19118, or half of the resi dents in Center City’s 19103 neighborhood earning less than $10,000 a year.

The study found that 71,300 employed workers in Philadelphia live in poverty. And since 2019, 30,000 youth aged 16 to 24 are neither in school nor employed. That’s more

20 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022

OF WORK Philadelphia businesses are trying to keep up with society’s shifting views on employment

FUTURE

PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

story by marilyn anthony

During her time as Small Business Development Center Director at Temple, Maura Shenker worked with many “solopreneurs” to navigate non-traditional work circumstances.

than 100,000 residents sidelined from mean ingful participation in the local economy.

How are we as a city and a people trying to improve the future of work as we enter what some have dubbed the “fourth Indus trial Revolution”? Or, as one young profes sional, who preferred not to be identified due to concerns about negative feedback from their current employer, asks, “How can we build a world designed for the max imum enjoyment of life for the largest num ber of people for the longest time possible?”

Some public and private sector programs are tackling the challenge in various ways.

The SBDC’s no-cost programs are de signed to support the underserved com munity in North Philadelphia. SBDC saw a surge in “necessity solopreneurs,” individ uals starting businesses to earn income af ter being laid off or unemployed during the pandemic. Many of these small businesses were in child care, cleaning services and other sectors with low startup costs.

Former SBDC director Shenker depicts the aspirations of these solopreneurs as fi nancially modest. “It’s not about making as much money as possible—the race to a bil lion dollars is not what they’re looking for.”

Their business goals are aimed at achiev ing a comfortable lifestyle, one free from struggling to provide their families with a safe home, food security and some financial cushion against emergencies. Shenker notes that these businesspeople have different metrics for success. They don’t judge suc cess on business growth, but on earning enough and allowing for work-life balance.

Philadelphia Works, Inc. is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization whose mission is to increase economic opportunity for all Phil adelphians. In collaboration with business, government and other nonprofits, Philadel phia Works strives to identify and socialize workforce solutions. The organization has not been immune to COVID-19 stresses it self and has been reinventing the way it op erates in response to post-pandemic needs.

Philadelphia Works’ Blumenauer de scribed one shift in their focus as the “hyperlocalization of interventions.” Instead of devoting resources to top jobs in education and healthcare, they are investing in filling positions that were not affected or only min imally disrupted by the pandemic, those paying at least $15 an hour with low barriers to entry for education and experience.

Waiting for employment seekers to come

to the Philadelphia Works office is a thing of the past. The organization is doing far more outreach to neighborhoods with high em ployment needs while trying to improve the wraparound services necessary to remove some obstacles to employment. These may involve better vocational training, career coaching and helping with access to food and child care by beefing up coordination with partner service organizations.

Frances McNeal is the executive director for the Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Busi nesses program at the Community College of Philadelphia. The Goldman Sachs pro gram provides education to small business owners across the United States to help them strengthen and grow their enterprises.

McNeal says the opportunity landscape is changing as workers look for more au tonomy and flexibility. She sees workers re thinking what they want and need and what they are willing to do to reach their goals, and the stress that puts on small businesses.

McNeal knows local businesses are struggling to find good employees in part because many of these low-paying jobs in health care, education and in-home services require in-person work without flexible scheduling. If employers can’t adapt their operations to accommodate worker expec tations, it may force some businesses to close. Workers may end up choosing to hold two or three remote jobs rather than fulltime employment with a single employer.

McNeal believes “America’s contract with its people is fundamentally flawed.” She asks the hard question we all need to address: “Who as a society do we recognize is valuable as a worker?” In her view, too small a slice of the population is considered “worthy of work,” leaving out the formerly incarcerated or those with low levels of ed ucation or professional experience.

Co-founders Opéola Bukola and Alex Hillman are trying to build our local econ omy with 10k Independents. Their initiative

is based on the belief that the people, money and knowledge essential to creating 50,000 good jobs over the next decade already exist in Philadelphia. Their radical approach to economic recovery starts with “three core pillars of action”: assisting people to find new paths to a good career, enabling “inde pendents” or small businesses to move from survival mode to thriving, and prioritizing hiring and growth that benefits neighbor hoods and communities.

10k Independents provides events, infor mational guides and the “Career Control” digital ’zine (which can be downloaded upon request at their website), all aiming to co alesce the experience, energy and creativity of gig economy or “solopreneur” workers into a peer network of sharing and support. Hill man says that “the future of work is already here. It’s just unevenly distributed.” 10k Inde pendents wants to enable more workers, not just executives and entrepreneurs, to have greater autonomy and flexibility.

Attitudes and values have become central to any discussion of the future of work. Shenker says the pandemic shone a spotlight on exploitation in the workplace — who was at risk, whether the risk was worth the cost, who had to go into work, and who worked comfortably from home. The pandemic revealed that “normal” was unacceptable. “People want to work,” she says. “They just don’t want to be exploited.”

Many workers think that “quiet quitting,” defined as doing precisely what the job re quires, should be the expectation for employ ment rather than the 24/7 demands imposed by a constantly connected workplace. “Acting your wage” offers a saner approach to setting limits. Work-life balance comes down to the fact that we work for money. The amount we require depends on the strength or weakness of a social safety net. Most of us work to buy some security in our lives, not to pursue a passion or become mega rich.

Alex Torch, a recent college graduate,

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 21

People are time poor and money poor and feel powerless at work.”

maura shenker, former director of Temple’s Small Business Development Center

works a part-time job as they weigh their career prospects. They think a major shift needs to occur in our economy and that in dividuals have the power to effect change, as evidenced by stirrings of new unionizing efforts. “You’re a worker bee but you have a whole hive of other workers around you,” they say. Torch would like to see fair wages and respect for all work, enabling not just white-collar but blue-collar workers to earn a livable wage with time for family, friends and hobbies. Coupled with more affordable higher education, Torch believes, the result would be a much more diverse workforce.

Blumenauer acknowledges the possible widening opportunity gap that worker ex pectations may pose for employers. Creating or preserving diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) in a hybrid work world is a major hur dle. Remote work isn’t possible for everyone. As businesses redefine their work practices, Blumenauer cautions, there is the potential to undo whatever gains employers may have made in their DEI initiatives.

Still there is some cause for optimism.

patricia blumenauer, vice president for operations and data at Philadelphia Works, Inc.

Many businesses have shown their abili ty to be more flexible and innovative than they previously thought possible. Blu menauer predicts we will continue to see employment modes evolve. “The workday, the workplace and the work world aren’t going to look like they have. We’ve shown we know how to pivot.”

Nearly a year into her pivot, Erin Mattson is building a new career as a macramé ar tisan. At times that has meant working 80hour weeks while facing the uncertainty of any fledgling enterprise. For someone who is risk averse, it’s a big step into the un

known. But Mattson knows she is among the privileged few who can afford to step off the career treadmill to create a fuller life for herself and her partner Viscelli’s job pro vides steady income and health insurance, and the frugal couple have set aside savings to ease the transition. Mattson’s mother al ways advised her to find work she liked and was good at, but that would never dominate her life. “I don’t need to do something fab ulous for work,” she says. For this couple, success is to be found in a healthy life and healthy relationships. That’s what Mattson is working for. ◆

22 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022

Patricia Blumenauer works to bridge the gap between everchanging employer and employee needs at Philadelphia Works, Inc.

COVID opened up the eyes of workers a bit more to what their options might be.”

PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 23 GIVE THE GIFT OF LOCAL INDEPENDENT JOURNALISM! HAPPY HOLIDAYS and THANK YOU FOR SUPPORTING SUBSCRIPTIONS ARE AVAILABLE STARTING AT gridphilly.com/subscribe We appreciate your continued support! JUST $2.99 PER MONTH This holiday season, subscribe to the magazine you love.

RICH PARK, POOR PARK

story by bernard brown photography by troy bynum

On october 2 a large pile of tires was dumped below the Whitaker Avenue Bridge in Tacony Creek Park. One tire lodged in a forked trunk of a tree growing below the bridge. Two others had hooked a branch of another tree and remained suspended about 15 feet up in the air. A tire dropped from a bridge that happens to land on its edge can, of course, roll downhill, and several had ended up at the bottom of the creek, visible beneath the water.

Twenty days later, when Grid visited the park, the tires were still there.

Tacony Creek enters the city from Montgomery County, where it is called the Tookany, and forms a rough boundary be tween North Philadelphia and Northeast Philadelphia. For about three miles the

creek winds through the 300-acre, mostly wooded city park with the public Juniata Golf Course on the southern end (which the creek exits with yet another new name: Frankford).

Visitors to Tacony Creek Park will find a landscape similar to those of the city’s other creek-corridor parks such as Cobbs, Penny pack, and the Wissahickon: a trail running along the creek, with woods and meadows rising on either side and some manicured park spaces along the edge. It’s a world apart, where flowing water, singing birds and towering oak trees provide a respite from the landscape of brick, concrete and asphalt. Tacony Creek Park is on the small side at 300 acres, especially compared to the Wissahickon at over 2,000 acres.

The park serves a mostly Black and

Brown population living in a mix of workingclass and high-poverty neighborhoods. The problems of those neighborhoods spill into the park in the form of gun violence, ATV use, and trash dumping in a way that visitors to the Wissahickon, which cuts through some of the city’s wealthiest neigh borhoods, seldom encounter.

Not surprisingly, Tacony Creek Park visi tors that Grid spoke with complained about dumping. “The park is something very pret ty, but the people don’t take care of it, like here up ahead they dumped a pile of tires,” said a park visitor whom Grid interviewed

24 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022

Philadelphians struggle with insufficient resources for park development and maintenance

Tire dumping has been a long time problem in the Tacony Creek.

in Spanish and who asked to remain anon ymous out of fear of reprisal from illegal dumpers and ATV riders. She lives about three blocks from the park and takes a daily exercise walk with her husband. “After that the tires ended up in the creek as well. Also there were two cars; they burned them.”

According to Julie Slavet, the director of the Tookany/Tacony-Frankford (TTF) Watershed Partnership, an organization that has taken on a stewardship role in the park, she had gotten in touch with the 25th Police District to point out the danger of abandoned cars next to a pile of flamma

ble tires. “I said, ‘We’re going to have a tire fire,’” she says, and that motivated them to remove the cars.

The chronic dumping, and the City’s slow response, communicates a low regard for the park. Grid asked Silvina Godoy, who was walking on the main trail on October 22 and who serves on TTF’s board, what she’d like to see in the park. “More funding for safety, less dumping, more respect for the space. You can go to other parks and see that people don’t dump as much as they do here.”

Luanda Morris, a TTF board member who lives in Frankford, wishes the City did

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 25

If these tires were in the Wissahickon or on the [Benjamin Franklin] Parkway, they’d be gone.”

julie slavet, executive director of the Tookany/TaconyFrankford Watershed Partnership

more to clean up the park. “Because we as TTF and as the community, we do a bunch of cleanups, and there’s never a cleanup where all the trash is removed. It’s not fea sible for us,” she says. “I happened to be in the suburbs the other week and my family went on a walk in a state park. They had trash cans. You could tell they were cleaning it and making investments in it.”

Slavet was more blunt. “If these tires were in the Wissahickon or on the [Ben jamin Franklin] Parkway, they’d be gone.”

According to Philadelphia Parks & Rec reation (PPR) spokesperson Maita Soukup,

who responded to a Grid request for com ment for this article by email, the department removed 18 tons of tires from the pile, though, by November 2, when TTF held a cleanup event to remove the tires, there was still a substantial pile under the bridge. According to Soukup, the department has responded to “more than 20 requests in the last 12 months to address short dumping, graffiti removal, or other repair needs resulting from nuisance behavior.”

Grid visited Tacony Creek Park on a sun ny Saturday for two hours around midday and encountered no more than 20 park vis

itors, a distinct contrast with busier parks such as the Wissahickon that are packed on nice weekend days.

According to community members who visit Tacony Creek Park, there are good reasons to avoid it, or at least to carefully choose safe times to visit. One of the trail signs had bullet holes. “On the path you can see many bullets,” said the same anon ymous park visitor who had pointed out the tires. She only visits accompanied by her husband.

Siani Colón, who volunteers in park cleanups and who lives in the watershed,

26 GRIDPHILLY.COM DECEMBER 2022

also talked about gun use in the park. “One thing in terms of safety that people are con cerned about is gun violence. I have walked the trail many times and have found mul tiple casings along the trail,” she says. “At night you can hear gunshots and you can tell it’s coming from the park.”

Dirt bikes and four-wheel ATVs also endanger park visitors. “I was at an event going on, a bird walk, and I could hear the ATV from a distance, but as it got closer that’s when we started pulling the children aside,” Colón says. “The kids could have been hit. There was an instance where a child was hit by an ATV.”

Tim and Hope Johnston have taken their four children for nature walks and other programming in the park for the past 10 years. “We have found it can be difficult to use it at certain times because of the ATV use in the parks,” Hope says. “If you go in the morning, you’re probably okay. If you go in the afternoon it can be much more diffi cult, particularly with kids.”

Like other park stakeholders Grid spoke with, the Johnstons wish there were a place that ATV users could ride without putting others at risk. “I grew up in northern Ver mont, and I have family members who love using ATVs in those rural communities,” Tim says. “I understand that they’re really fun, but it just does not work in a city park.”

PPR’s Soukup said that the department has installed new park gates and has placed logs and boulders at park access points “to discourage ATV use and limit access for potential short dumpers.”

ATV use came up at a June presenta tion of a draft master plan for the park, spearheaded by TTF in collaboration with conservation nonprofit Natural Lands and PPR. A neighbor of the park complained about the ATVs tearing up the vegetation and running families with children out of the park. The Natural Lands consultants presenting the draft plan mentioned phys ical changes to the park meant to deter ATV use. Ultimately, though, getting more people into the park is itself the best way to make ATV riding there less popular.

Along with safety concerns, a survey conducted for the planning process found that the biggest barrier to using the park more was that the park wasn’t clean. These themes echoed throughout the survey. The top four answers to a question about preferred improvements to the park were

“trash cans,” “make park safer,” “deter ATV use” and “improve trail surface.”

Accomplishing all of these improvements won’t be easy. A more crowded park is less inviting to people engaged in illicit activi ties such as shooting guns, dumping tires or riding ATVs, but those same activities drive visitors away. Improving park maintenance, including picking up litter and emptying trash cans, is labor intensive, and it runs into the hurdle of an under-resourced PPR.

Toward the end of 2019 TTF, partnering with the Partnership for the Delaware Es tuary, the Philadelphia Water Department, Clean PHL and the Managing Director’s Of fice, installed 20 “community cans” around the Juniata Park end of the park, including Ferko Playground. These were not simply off-the-shelf garbage receptacles, but cans painted in a community event and designed by local artist Jay Coreano. But at the start of the pandemic, as the Department of Streets fell behind in collecting trash throughout the city, household trash started piling up next to them. Then the community cans started to disappear. “We thought they had been stolen,” Slavet says.

She learned the truth when she happened to see the cans piled up at a PPR mainte nance facility. Slavet says she called PPR’s deputy commissioner of operations, Sue Buck, who, according to Slavet, apologized and explained that PPR maintenance crews pulled the cans to stop attracting trash. Slavet sympathizes with the overworked PPR staff. “I know [Buck’s] life is crazy, and she has been responsive to us,” Slavet said, but she disagrees that removing trash cans is the right way to deal with the city’s waste problem. “There is an unwillingness to ad mit lack of capacity and plan how to solve it. The city has all these problems caused by poverty, and the way we’re going to deal with them is to say people can’t have nice things because it will make the problems more visible.”

There is widespread agreement that PPR lacks the money to adequately and equitably maintain Philadelphia’s park system.

According to the Trust for Public Land’s ParkScore, which is based on figures re ported to the trust by city parks depart ments, Philadelphia budgets $50 per capita for PPR’s capital and operations budgets (capital refers to one-time expenses like constructing and renovating buildings, which usually is paid for by the City bor

DECEMBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 27 ALEX MULCAHY

It is my belief that neighborhood parks do not receive the same attention and investment as Center City areas .”

cherelle parker, former Philadelphia City Councilmember and current mayoral candidate

Luanda Morris has been advocating for years for a cleaner Tacony Creek as a board member of TTF Watershed Partnership.

rowing money by issuing bonds, while the operations budget, which includes main tenance and programming, comes from annual tax revenue and other income such as grants), well below the national aver age for park budgets of $83. Philadelphia also gets an unusually high total of $22 per capita (30% of total parks spending) from volunteer hours and spending from private groups, compared to the national average of $8 (8% of total spending).

Another way to measure the underspending in Philadelphia parks is the decline in spending relative to the overall City oper ating budget. A 2021 study examining the increase of tree cover in Philadelphia drew a connection to reduced park spending. As maintenance budgets declined in the 20th century, the reduced mowing and trimming let trees grow in untended areas.

The budget for the Fairmount Park Com mission, which governed watershed parks such as Tacony Creek and the Wissahick on, and which merged with the Recreation Department in 2010 to create Philadelphia Parks & Recreation, went from 2.26% of the City’s operating budget in 1960 to 0.32% in 2009, approximately one-seventh of what it was almost 50 years prior.

The parks budget still has not recovered. According to City budget figures, in fiscal year 2022 PPR spent $77.8 million in oper ating funds (this includes $65.4 million from the tax-funded general fund as well as $12.4 million in grants) out of a total City operating budget of about $5.5 billion. It is difficult to completely separate spending on what used to be the Fairmount Park system, but sub tract $34.5 million spent on recreation ser vices (mostly rec centers), and the remaining $43.3 million is 0.78% of the total City operat ing budget, more than the low point in 2009, but about a third of the percentage that the City spent on parks at its peak.

PPR’s Soukup wrote that the department spends about 20% of its operating budget, or about $15 million, on “park operations and ground maintenance staff and turf and tree maintenance for the entire system.”

Although Philadelphia spends relative ly little on its parks, it is not alone in see ing park spending decline, particularly on maintenance. “Maintenance and funding are the number one questions that we hear from cities across the country,” says Bian ca Shulaker, the Trust for Public Land’s Parks Initiative lead and director of the 10-

Minute Walk Program, which aims to close the parks equity gap. She pointed to a na tional decline in average park spending per capita from 2007 to today, in spite of the pandemic demonstrating the need for clean and safe parks.

The challenge of funding maintenance also holds back growth in park systems. “The number one thing we hear from cities is they can’t add new park spaces in places that really need them since they don’t have the budgets to maintain parks that they al ready do have,” Schulaker says.