AUSTRALIAN FORESTERS in PAPUA NEW GUINEA 1922-1975

PNGAF MAGAZINE ISSUE # 9C2 of 2nd May 2024.

AUSTRALIAN FORESTERS in PAPUA NEW GUINEA 1922-1975

PNGAF MAGAZINE ISSUE # 9C2 of 2nd May 2024.

Editor R B McCarthy1 2024.

1 Dick McCarthy District Forester TPNG Forests 1963-1975.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FORWOOD page 3

Background to the Mokolkols page 6

Background to D M Fenbury page 14

J K McCarthy 1950 page 16

D M Fenbury 1950-51 page 18

Bill Heather’s Adventures with the Mokolkols page 28

MeetingtheMokolkols:JimToner2002 page33

A Mokolkol Sequel - Des Harries page 37

Ken Granger’s Experience with the Mokolkols page 41

An Example of a Timber Rights Purchase: Chris Borough page 47

TPNG Forester Chris Borough and the Mokolkols Page 53

Tsunami at Matanakunai by Chris Borough Page 60

Today Open Bay Timbers ltd.

Page 63

Sunset. Photo credit Chris Borough.

Foresters in PNG have forever been involved with the development of forest concessions on a sustainable basis.

Responsibility for the administration and development of the forest resources of Papua New Guinea and control of its forest industry was vested in the Department of Forests under powers conferred by the Forestry (New Guinea) Ordinance 1936-62 and the Forestry (Papua) Ordinance 1936-62 and the Forestry regulations as amended.

Nearly all forest in PNG is grown on customary-owned land. The Department of Forests after 1945 had to create a forest concession system that catered for all parties i.e., landowners, government agencies and developers.

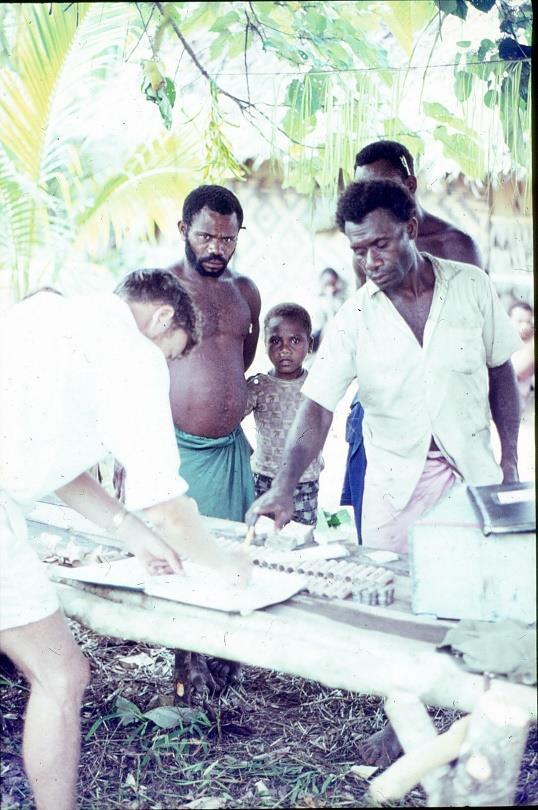

For any timber to be harvested on an area, the State had first to acquire timber rights from the landowners before allocating the rights to a logging company. Prior to 1992, this was done through either the negotiation of a timber rights purchase or a local forest agreement. Since 1992, when a new Forest Act came into force, state acquisition of timber rights has been through the negotiation of forest management agreements between the PNG Forest Authority and customary owners.

The Territory policy for the extraction of timber from customarily owned (‘native’) forests was developed over time through the mechanism of a ‘timber rights purchase’ (TRP) agreement, which was a way of purchasing so-called ‘timber rights’ from customary owners of forests, but not alienating the land. Virtually all logging companies in the territorial period were Australian-owned or Australian-based. Some of these did a degree of processing locally, but most timber was exported as round logs. The legal framework for forest exploitation had three main elements: Timber Rights Purchase (TRP). Under this arrangement the State acquired timber rights where customary owners were willing to sell. The State then issued a permit or licence to remove the timber on agreed terms and conditions, including the payment of royalties, a portion of which was passed on to customary owners. The TRP arrangement was intended for large-scale exploitation and was managed by the Department of Forestry.

Timber Authorities (TA) could be issued, on payment of a fee, to enable any person to purchase a limited quantity of timber directly from a customary owner. Without a TA, no one other than a Papua New Guinean could purchase forest produce from a customary owner.

However, there was no management control over TAs other than limitation on the quantity of timber purchased. Forestry (Private Dealings) Ordinance, 1971 (which became an Act in 1974). This enabled customary owners to dispose of their timber to whomever they wished, provided that (a) the interests of the owners were protected, (b) there was no conflict with national interest, (c) prospects for economic development were considered, and (d) the Administrator gave his approval. (Carson2 1974). At the time, many forestry officers were

2 2 Carson, G.L., 1974. Forestry and forest policy in Papua New Guinea. Commonwealth Fund for Technical Aid. 20 p.

concerned about these private dealings since their impact was diametrically opposed to proper management of the forest resource.

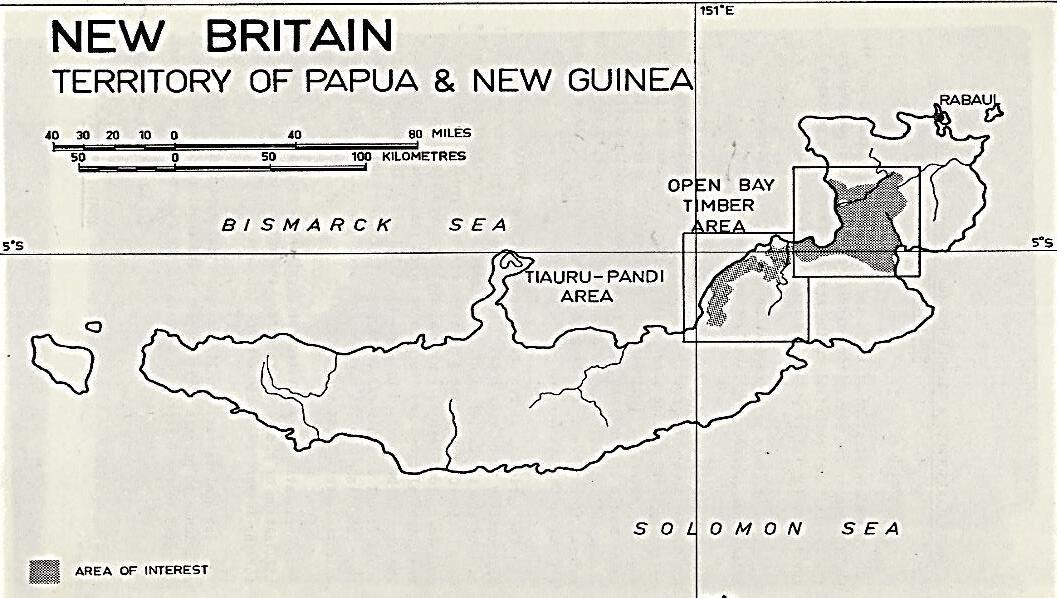

An example of a major forest concession development the three-way partnership –Government, traditional forest landowners and developers was the Open Bay Timber Area in which the Mokolkol tribe resided.

In dealing with tribal groups such as the Mokolkols, foresters were expected to resolve any people issues.

The fearsome reputation of the Mokolkols worried J K McCarthy (as did Ken Granger in later years) when he was organizing evacuation of theAustralisArmy Garrison from Rabaul which had been overrun by the Japanese in 1943. Escaping soldiers had to walk across Mokolkols lands to escape the Japanese invasion.

Des Harries’3 article provides a personal experience which throws some light on the nature of forestry activities in the Open Bay area at a time just preceding the period of active log exporting along the north-coast of New Britain in about 1965. This included the start of the massive oil palm plantation development in this area and the destruction of perhaps the best of PNG’s lowland forest resources.

The issue of log export was never a TPNG Forest Policy as Des Harries highlighted above. All forest management policy initiatives were to create an ongoing sustainable forest management regime producing wood fibre in the format of logs over a specified diameter on a 35-year rotation, suitable for conversion into sawn timber for domestic housing and export markets.

Separate TPNG Forests research efforts at the Forest Products Research Centre developed timber preservation methods to protect the ensuing sawn timber.At the same time, regulations were put in place to ensure all timbers used in PNG public housing projects were treated to defined timber preservation standards.

The Second Waigani Seminar, published in 1969, included an article by D.M. Fenbury, "Meeting the Mokolkol", New Britain, 1950-51. Bill Heather accompanied Fenbury on that patrol to contact the Mokolkols.

However, in Chris Borough’s articles by 1968, the Open Bay Forest Concession was established with the timber rights purchase successfully accomplished.

Since 1971 the Open Bay Timber Concession with currently an established plantation base of some 32,000 hectares of E deglupta (Kamarere) plantations (on state lands in Open Bay) has been continuously operated by Open Bay Timbers Limited (OBT) a subsidiary of the Sumitomo Forestry Group.

3 Personal communication Des Harries 21st Feb 2023.

Phil Fitzpatrick described the background to the Mokolkols in his article Days of the KiapCorporal Bosi & the mysterious Mokolkol4 29 January 2013.

The current traditional land owners of the Gazelle peninsula are the Tolais who are believed to have originally come from New Ireland. When they settled in the Gazelle Peninsula, they pushed out the Baining, who fled to the mountains. Those Baining on the coast not killed or eaten by the Tolai were used as slaves.

4

The surviving Baining retreated to occupy the foothills of the Rawlei Range and the land south west of Ataliklikun Bay. Other Baining villages were located north and south of the Warangoi River and in the hinterland west of the Rawlei Range. They are thought to be the descendants of the first people to reach New Guinea and its islands. Sometimes referred to as Negrito and in contrast to the tall and virile Tolai, they are small, stocky people.

One of the Baining groups caught up in the Tolai invasion was the Mokolkol5, who were located on the narrow isthmus between Wide and Open Bays.

For many years they remained beyond contact of the German and then Australian administrations. All that was known of them were their sudden raids on coastal villages. They would attack and then disappear back into the jungle.

They became legendary and were regarded by their victims as devils from another world. It wouldn’t be until 1950 that a patrol succeeded in reaching one of their hamlets.

The only weapon the Mokolkol used was a long-handled obsidian axe. The stories of the deadliness of these razor-sharp blades and the silence in which the Mokolkol approached struck terror into the hearts of people for hundreds of kilometres along the coast.

5 Ryan P Editor Encyclopedia of Papua and New Guinea. 1972. Publisher Melbourne University Press and UPNG. ISBN 0522840256.page 293.

The Mokolkols were a small group of less than a hundred people. No one knew where they originated.

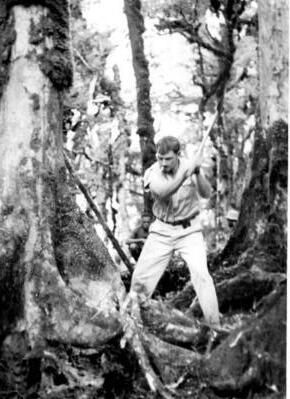

Typical vegetation on the Open Bay Isthmus. Photo credit Ian Whyte 1974.

Some said they were the survivors of a tribe wiped out by the fleeing Baining as they searched for new homelands. Others thought they were the Baining descendants of deserters from German plantations.

Typical vegetation on the Open Bay Isthmus.

Old village site.

Photo credit Ian Whyte 1974.

The story goes that a German kiap had called together the people living in the Tol area following several murders.

The Baining were fingered as the culprits and without warning the German police opened fire on them, killing many. A few got away into the bush and their descendants were said to be the dreaded Mokolkol.

The first Australian patrol to attempt contact with the Mokolkols went into the mountains in 1931. The kiap found one of their recently deserted settlements and set up camp to wait for them to come back.

The Mokolkols returned four days later under cover of drizzling, misty rain and, swinging their long axes, hit the patrol hard. They left two dead and four badly wounded and disappeared.

The next patrol into the area was in 1934. The kiap found an old man with two women and four children. On the way out the Mokolkols put an axe through the head of a lagging carrier.

The adult Mokolkol the patrol brought out of the mountains quickly succumbed to illness and died but the children survived with two of the girls eventually marrying policemen.

In 1939 a party of 10 Mokolkol raided Kalip. They swept through the village pillaging the houses for steel axes. In their wake they left 25 men, women and children hacked to death. When the Kalip people presented the kiap with a stick with 25 notches in it, he took off after the Mokolkol.

After several days, the patrol came across a small village behind a heavy stockade on a ridge. Kiap John Milligan and Corporal Yeng crept up for a closer look and were spotted by a lookout.

The man yodelled an alarm and then charged the kiap and policeman swinging his longhandled axe. They had little choice and shot him in the chest.

They followed the Mokolkol for two weeks but saw neither hide nor hair of them. When the village was revisited, it was found to be abandoned.

The following year a patrol investigating more Mokolkol outrages got close, but the wily bushmen slipped through the net. They abandoned a girl of about 10 with an injured leg. She had apparently been a member of the raiding party.

Nothing was heard of the Mokolkol for a while until 1944 when they attacked a party of Australian and Papua New Guinean troops operating behind enemy lines.

The troops were ready for the Japanese but not the Mokolkol, who swept through their camp in the early morning swinging their deadly axes. Neither side suffered any casualties beyond a rifle butt split by a long-handled axe.

Again, the Mokolkol went quiet but in 1950 they struck again and raided a village in the Kasalea area killing 11 people.

Around this time a Catalina pilot flying across the Gazelle Peninsula saw a small village in what had been presumed to be uninhabited country and reported it to District Commissioner Keith McCarthy.

The DC flew back over the village with the pilot, and they attempted to fix its position. The opinion in Rabaul was that the village was occupied by a remnant group of Japanese soldiers, but the DC thought otherwise.6

To find the village, he despatched Assistant District Officer David Fenbury7, Cadet Patrol Officer Chris Normoyle and Bill Heather, a forestry officer with surveying experience, along with eight police under the command of the experienced Corporal Bosi.

The patrol armed itself with a Bren gun just in case there were Japanese in the village.

When they came across a hunting camp Corporal Bosi said, “They’re Mokolkol Kiap. This is an old axe handle. We’re on their trail and by a count of their beds I’d say there are 15 of them.”

The Mokolkol led the patrol on a merry chase. After six days Corporal Bosi was moving alone down a gorge ahead of the main party when he came across a small stream. In the porous limestone country water was scarce and he hid in the bush and waited. Soon a woman appeared with some bamboo containers and filled them with water.

Fenbury and Corporal Bosi followed the woman’s path. When they came to the village it fitted the description given by the DC and the pilot. Corporal Bosi crept ahead When he came back, he said, “They’re Mokolkol and they’re not suspecting a thing.”

“I was afraid they would be Japs,” Fenbury whispered.

“Kiap, they’re not Japs,” said a surprised Corporal Bosi. “Japs could not get here without leaving tracks. And you know yourself what noisy buggers they are. Besides, I think I could smell a Jap even at this distance!”

7 Note David Fenbury changed his surname from Freiberg in 1960.

They decided to raid the village straight away.

Corporal Bosi led the two kiaps, six police and Luluai Moite and eight of his carriers back to the village. There was an open stretch of ground before the settlement. Then the ground fell away rapidly on the other side.

If the Mokolkol heard the patrol they could escape down, there easily. Corporal Kindili and three of the police worked their way around to the slope. When they were in position, the patrol moved on the village.

A pig sighted them and began snorting in alarm. Someone had said that the Mokolkol trained their pigs like dogs. A woman came to check and uttered a fearful yell and headed for the bush. Then the patrol was in the village.

The police went quickly through the houses. Then from the doorway of one of them, a huge man emerged. In each hand he swung a long-handled axe. The police and carriers backed away in awe.

He was a magnificent sight and for a brief moment, before Fenbury put a burst of fire from his carbine at his feet, he was master of the scene. The man dropped his axes and dived back into the house.

“Look out that he doesn’t break out through the back wall,” shouted Corporal Bosi. It took them a while to winkle the man out of the house.

When he was in the open and handcuffed, he made signs to the corporal to knock him on the head and be done with it. Corporal Bosi later said that he was tempted by the offer but declined.

The patrol managed to capture two men, a woman and four children. The rest of the Mokolkol, maybe 30 people, slipped away into the bush.

The village was well supplied with food with plenty of taro and slabs of pig meat hanging from the rafters in the houses. Corporal Bosi collected 42 axes. He guessed there might have been about 35 people in the village with maybe 10 being adult men.

The big man they captured and who was sawing at his handcuffs with a piece of obsidian appeared to be sick with malaria. The attempt to take his temperature was thwarted when he bit the thermometer in half and chewed up the glass pieces.

On the way back to the coast Corporal Bosi shared betel nut with the other man, who was called Malil. The big man was called Lamu, and he nearly died of pneumonia in Rabaul but, despite his determination to die, he was saved. The woman, Manu, quickly adapted to capture and began to enjoy herself in Rabaul.

Six months later the men and the woman were taken back to their village. Malil and Lamu went off, each holding a new steel axe. Manu stayed with the patrol and assured Fenbury the two men would soon be back with the rest of the clan.

In seven days Malil and Lamu returned with six other men in tow. They shouted greetings to Fenbury and Corporal Bosi. When the excitement of their arrival had died down, they began to chant.

It was one word: “Akis! Akis! Akis!” repeated over and over again. Corporal Bosi was already breaking open a case of axes.

Manu, who had learned Tok Pisin in Rabaul, interpreted for the patrol. Malil, now sporting a luluai’s cap said, “It is much easier to get axes from the white man than raiding for them. Come back in six months Kiap and we will have a proper road for you and a rest house for you to sleep in.”

The luluai kept his promise. Six months later a patrol visited Atar, a new village built along coastal lines with a commodious rest house and police barracks.

In 1956 a group of Mokolkol burst out of the bush into a settler’s place near Wide Bay. The men were carrying long-handled axes and the plantation labourers scurried for cover.

However, when the men saw the settler, they greeted him cheerfully and asked for salt. The settler handed out liberal portions and the Mokolkol left. They didn’t ask for axes, and they never raided again.

David Fenbury’s account of the Mokolkol patrol formed a series of three articles in the ‘Bulletin’ in 1956. Accounts of that and other patrols in quest of the Mokolkol appear in Malcolm Wright’s book, ‘The Gentle Savage’, published by Lansdowne Press of Melbourne in 1966

In the second Waigani Seminar, D M Fenbury8 who had much to do with forester Bill Heather presented a paper titled Meeting the Mokolkol New Britain 1950-51.

Trove describes David Maxwell Fenbury as born in Western Australia in 1916 and become a patrol officer in New Guinea in 1937. After wartime service with the AIF and ANGAU, followed by a period with the Government of Tanganyika, he returned to New Guinea in 1947 to become Assistant District Officer responsible for organising native local councils. After holding several other senior posts, he went to New York as the Australian Government Nominee in the trustee division of the United Nations Secretariat. In 1972, he became Secretary of the Department of the Administrator. His last post before retiring from the Territory was in 1962 was secretary of the Department of Social Development and Home Affairs.

The David Fenbury papers are stored in the National Library ofAustralia. (Ref # MS 6747) covering the period 1937 to 1976. The David Fenbury papers are arranged into various subject groups and relate to his career as Patrol Officer and later asAdministrator in Papua New Guinea.

The collection includes patrol reports, diaries, photographs, drafts of Fenbury's writings for publication and his officer correspondence. There are two diaries: 1941 diary with details of 144-day patrol nearAitape: 1944 diary documenting wartime patrol and includes an incident of the surrender of a Japanese officer and his men. Other material in the group concern Fenbury's Military Career and patrol reports for 1938 - 1945 in particular the Mokolkol Patrols. Series B: Newspaper cuttings. Manly PNG 1960-1971. Series C: Lecture notes short stories and addresses by Fenbury concerning PNG administration for the period 1940-1973. These include letters to the media and seminar papers. Of note in this group of people is DMF's short story MSS. The White cassowary and correspondence with Douglas Lockwood, war correspondence - but here Managing Director of S. P. Post. Series D-K - Native affairs: Memoranda, minutes, letters, reports concerning the administration and politics of local government, land tenure and the development of the native village count, particularly in the Gazette Peninsular. The correspondence includes letters by Paul Hasluck, J. K. McCarthy, M. Oken. Working papers, correspondence, and printers’proofs of Fenbury's book Practice without policy

8 David M. Fenbury. 1971. Meeting the Mokolkols, New Britain 1950-51. In Kenneth Stanley Inglis (ed.), The history of Melanesia: papers delivered at a seminar sponsored jointly by the UPNG, ANU University, the Administrative College of Papua and New Guinea, and the Council of New Guinea Affairs held at Port Moresby from 30 May to 5 June 1968, 153-176. Port Moresby: University of Papua and New Guinea; Canberra: Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. (Same as Fienberg, David M. 1959 Meeting the Mokolkols. The Bulletin 6/5/59, 19,45; 13/5/59, 19,45; 20/5/59, 19,45; 27/5/59, 19,82; 3/6/59,19.).

Note David Fenbury changed his surname from Fienberg around 19660.

J K McCarthy District Officer 1950

J K McCarthy in his book Patrol into Yesterday9 , during the rescue efforts of the Australia soldiers from Rabaul referred to the dangers of crossing the traditional lands of the ferocious Mokolkols. The Mokolkol reputation of silently sweeping into a camp, killing with long handled axes, and disappearing into the jungle was feared by all.

Air Search for N. Britain Nomads10 - From a Special Correspondent.

The district officer of Rabaul (Mr. J. K. McCarthy) has stated that an air reconnaissance of the mountain territory of the elusive Mokolkol peoples, on the island of New Britain, has just been completed, and a village has been observed. A patrol will be sent out to try to contact these natives.

The Mokolkol is a fierce nomad tribe, which has consistently evaded capture during the entire years of the Europeans’ rule of New Guinea. The only Mokolkols ever captured are children, abandoned by their parents in flight. There are believed to be two of them at present in Rabaul, now grown up, who were captured in this fashion. These young Mokolkols, it was hoped, could be trained, and sent back to their village to civilise their own people but under the influence of civilisation they soon lost the Mokolkol tongue.

These fierce natives hunt with a primitive axe, descending upon a village and leaving a trail of dead behind them, then disappearing again into the surrounding hills, where they live in temporary camps. Other New Britain natives live in mortal fear of the Mokolkol.

A successful patrol11 has been carried out in the Mokolkol country, in the region of Open Bay hinterland, on the island of New Britain. Seven Mokolkols were persuaded to return to Rabaul with the patrol, which was led by acting ADO Fienberg, accompanied by Cadet PO Normoyle (Junior), and Forestry Officer [Bill] Heather.

The “captives” consisted of two men, one woman, and four children. The men are about 33, and 38 years of age and therein lies the tremendous success of this patrol. Previously only aged men, women, or children have been picked up by expeditions into the Mokolkol strong hold.

They said that there is only this one Mokolkol village, containing twelve males, one youth, eight adult females, and about ten children. It seems incredible that this tiny band of hillpeople should dominate and terrorise, as they do, about 500 miles of country. The natives will be taught Pidgin and in a few months’ time it is hoped to send them back to their village as proselytes of civilisation.

9 McCarthy J K Patrol into Yesterday. Publisher F W Chesshire 1963. Page 200, 204, 207.

10 Pacific Islands Monthly PIM Vol XXI, No 3 (Oct 1, 1950).

11 Pacific islands Monthly: PIM.Vol. XXI, No. 5 (Dec. 1, 1950).

Meeting the Mokolkols by D M Fenbury 1950/51

Meeting the Mokolkols by

D M Fenbury12’13

In the second Waigani Seminar, D M Fenbury14 who had much to do with forester Bill Heather presented a paper titled Meeting the Mokolkol New Britain 1950-51.

In a report to the United Nations the Administration of the Trust Territory of New Guinea included the following note.

“The Mokolkol people were visited by Mr. D. M. Fenbury, Assistant District Officer, and Mr. C. Normoyle [Chris], Cadet Patrol Officer and Forest Officer Bill Heather.… For more than a quarter of a century the Mokolkols have been known to the Administration as a small band of primitive nomads, apparently of Bainings origin, living in the country at the foot of the Gazelle Peninsula. Administratively they have enjoyed a notoriety disproportionate to their slight numerical importance, through their long-standing habit of raiding outlying hamlets, want only butchering men, women, and children, and disappearing without trace. Before the war, several patrols endeavoured to get into friendly contact with these people, but they were always met with hostility.”

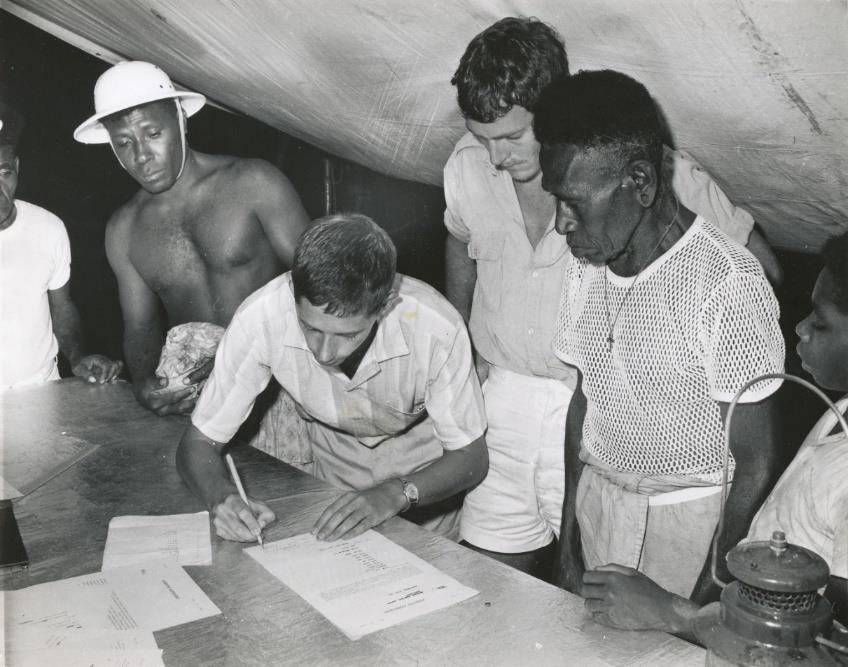

The patrol-party is about to lead-off into the wild Mokolkol country. [1950]

The continuing ability of a tiny band, adjacent to civilisation, to harass the countryside with impunity as the wild Mokolkols had done for years constituted an old and frustrating thorn in the professional pride of the Department of District Services and Native Affairs.

While tens of thousands of savage tribesmen were being brought under control each year on the New Guinea mainland, the Mokolkols, right under the noses of headquarters, continued merrily on their predatory course.

In the early days of Australian civil administration bitter native complaints about these wild men had resulted in attempted applications of the usual pacification techniques. At first special patrols were assigned to make contact and establish friendly relations.

One such expedition-was Penhallurick’s patrol, in 1931. After weeks of careful and arduous work in the inhospitable ranges, Penhallurick located a village on the edge of a steep ridge.

12 The Bulletin Vol 30 no 4135 (13th May 1959) Part 1.

13 Refer Second Waigani Seminar UPNG 30th May to 5th June 1968 p 153-176.

14 David M. Fenbury. 1971. Meeting the Mokolkols, New Britain 1950-51. In Kenneth Stanley Inglis (ed.), The history of Melanesia: papers delivered at a seminar sponsored jointly by the UPNG, ANU University, the Administrative College of Papua and New Guinea, and the Council of New Guinea Affairs held at Port Moresby from 30 May to 5 June 1968, 153-176. Port Moresby: University of Papua and New Guinea; Canberra: Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. (Same as Fienberg, David M. 1959 Meeting the Mokolkols. The Bulletin 6/5/59, 19,45; 13/5/59, 19,45; 20/5/59, 19,45; 27/5/59, 19,82; 3/6/59,19.).

Note David Fenbury changed his surname from Fienberg around 1960.

He was experienced in ordinary “uncontrolled area” work and proceeded accordingly. With his constabulary he crept up to the village just before dawn, laid out gifts of knives, axes, salt, mirrors, and cloth, retired a little distance, and, as the sun came up, yodelled in New Guinea mountain - fashion. The Mokolkols rushed out, snatched at the axes, jabbered excitedly, and fled into the bush. “New” people sometimes react that way, so Penhallurick made camp in the village, posted guards, and patiently waited for human curiosity to overcome primitive timidity.

That is a common method of extending Government influence. It nearly always works, provided you have the time and the rations, and can prevent your bored police and porters from getting into mischief. Once contact is made with one or two venturesome souls, others drift in; the patrol commences trading razorblades and salt for vegetables, dressing sores and injuries, and generally establishing friendly relations.

It is a hopeful sign when the women and children appear and the jungle housewife is quick to appreciate the advantages of commercial salt over the crude potash substitutes laboriously prepared from burning wild-sago roots.

• Occasionally there is trickery. In 1937, in the wild Saruwaket ranges behind the Rai coast, the warriors laid down their bows, and the women and children crowded around Assistant District Officer Nerton in the friendliest way. He reciprocated by sending most of his police off on jobs and began compiling a census. Suddenly some of the ladies pulled heavy bush-knives from beneath their grass-skirts and chopped at him. He survived but lost a leg.

Penhallurick waited four days without making any contacts. It was cold and wet in the mountains, and probably everyone became a little bored and careless. I can still recall the opening words of Penhallurick’s patrol – report diary covering the fifth day:

Drizzling: rain and mist. At 10.20 a.m., as I was sitting in my tent playing patience, a number of Mokolkols climbed the vertical side of the ridge unobserved and raced through the camp, swinging long-handled axes.

In that one rush the patrol-party had two men killed out-right, and four badly wounded porters were painfully carried back to the coast. Headquarters asked questions about playing patience in mid-morning.

Obviously, the Mokolkols were not quite like ordinary “new” people. And now the District Commissioner agreed to my suggestion that I should join the venerable ranks of Mokolkollers. After McCarthy himself whose duties, plus a war-souvenir in the form of an unpredictable knee, precluded lengthy mountaineering expeditions I was the most experienced field officer locally available.

From a comfortable chair on the lawn the idea of returning temporarily to the old bushwalking routine had a certain nostalgic charm and the Mokolkols had intrigued me for years.

Ernie Britten, the stipendiary magistrate, flouted the law by wagering a bottle of Scotch that the mysterious villagers would prove to be either Timoips or Japs.

McCarthy agreed to my claim that four Mokolkols equalled one month's use of the precious district trawler. As the village was located on the northern side of the central range-system, it was decided to go in from the north-coast side. We waited a month before setting-out, partly in case the unknown villagers had been disturbed by the aircraft’s circlings, and partly to arrive just before the onset of the north-west monsoon wet-season, when all good shifting cultivators should be at home clearing new garden sites.

The patrol included 12 native constabulary, mostly strangers to me, and two other white officers. Cadet Patrol Officer Chris Normoyle, tall and lean as an areca palm, was acquiring experience; Bill Heather, forestry-officer, and first-class survey-man, wanted to check the area’s timber resources.

Two good men, although I’d have preferred a smaller party. Extra officers necessitate a longer carrier-line. At halts they tend to talk together, and the simple tribesman with significant scraps of local information is often too shy to butt-in on the whiteman’s conversation. As we learnt during the war, that can be dangerous.

In the rainforest, even an experienced field-officer is relatively a blundering ignoramus, heavily dependent on the better-educated senses of his indigenous scouts. On ticklish jobs most officers prefer to work alone, with a small, hand-picked team of police.

Sea-transport was scarce, but ultimately, we loaded onto the Morobe patrol-trawler Huon, which had come over from Lae for minor repairs. Included in our party were two morose little survivors of the Kasalea raid, and two Bainings tultuls we hoped to use as interpreters.

We steamed around the Gazelle and anchored over-night at Massawa, where an old German missionary, resident in the Bainings, regaled us with villainous red wine and wildly improbable tales of past Mokolkol exploits. Thence to Baia inlet, on the sparsely populated east Nakanai beach, our jumping-off place.

Bill Heather continued down the coast to hire carriers for the trip from Ubili and Sule, where he was well known, and Chris and I set about preparing stores and sorting-out our policedetachment.

In routine foot-patrolling in the New Guinea bush you travel from village to village, hiring carriers at each, camping in little thatched rest houses, and subsisting largely on gardenproduce sold or bartered by the villagers.

Along the trails between villages, you shoot pigeons and hornbills for the pot, and occasionally bag a cassowary, possum, python, or tree kangaroo, which gladdens the light hearts and strong stomachs of the constabulary.

The elusive wild pig, while plentiful, is rarely encountered on the march. In localities where game is scare you eke out your canned meat with athletic village chickens and an occasional domestic pig.

The highly-prized indigenous hog is usually a crafty razorbacked misanthrope, long of snout and smouldering of eye unless blinded by his owner to prevent straying. He is apt to be an indiscriminate feeder, with a fondness for uprooting corpses from village cemeteries, and his flesh is more like mutton than pork. Not an engaging animal but nevertheless, fresh meat.

If you’re sound in legs, lungs and digestion, are tropic proofed against prickly-heat, safeguard your greased boots from starving village dogs, keep your basic stores dry, bring plenty of tobacco and an erudite tome you won’t finish quickly, cherish a folding camp-chair with back and arms, an efficient pressure lamp, and a henchman able to bake bread without an oven, then touring tribal areas can be reasonably carefree and comfortable.

But a jaunt like our assignment, into virtually uninhabited country, searching for humans much wilder than the local game, is a more exacting job, entailing careful preparation. Because of the need for secrecy of movement, you can’t establish advance-bases or be supplied by air; you can’t shoot for the pot; and you can’t expect to augment supplies by barter. It calls for night watches, no strong lights, and care regarding smoke and noise.

The patrol must be entirely self-sufficient, and its duration is limited by the rations that can be carried. Fancy foods must be discarded: rice, bully beef, Navy biscuits, sugar, tea, vegemite, and onions form the staple diet for all hands.

A permanent carrier-line is necessary, and this involves various little logistical calculations. The maximum load for a porter is 40 lb., and he’ll eat about 1 3/4lb. of rations a day. With strict supervision of meal issues, this means that in 23 days he will consume a weight of food equal to his original load and he can’t be sent home when his load is used.

On long-range intelligence patrols during the war, we learnt that, even with camping gear reduced to minimum essentials, and irrespective of the number of porters, a completely selfcontained one officer patrol can’t operate efficiently for much beyond 16 days.

Expeditions of this sort are rare. Administration patrols are primarily concerned with people, and in most populated areas of New Guinea root crop foods are plentiful. Except in times of seasonal shortage or local political crisis, a patrol can expect to live off the country, without touching the rice-reserve for days on end. In such areas Native Affairs patrols of up to four months’ duration are not uncommon. You camp in or near villages; and, in the best imperial tradition, trading literally follows the flag hoisting.

In the back-range country the supernatural origin still frequently ascribed to the whiteman’s manufactured goods is no bar: to men who have felled trees with stone axes the virtues of steel require no extolling. Granted a modicum of political adroitness and some knowledge of local supply-and-demand peculiarities, a patrol’s continuing subsistence then becomes a simple economic equation the convertibility of compact trade items such as salt,

razorblades, knives, fishhooks and cloth into bulky, stomach-filling yams, sweet-potato, taro, corn, bananas, sago, and pork.

Mokolkolling was a different proposition, and on this particular trip there would be three officers, 10 constabulary and two cooks. We studied the map and estimated for a comfortably rationed 12-days’ wander, with 36 porters. This included provision for young Chris’s fruitjuice and my bottle of rum.

During the next day a trickle of porters arrived, including a dozen rather scruffy little Kaulons from Kol, on the slopes of volcanic Mount Ulawun (the Father), New Britain's highest point (7546 ft.). This was a pleasant surprise, not only because mountaineers are best for mountainpatrols but also because the Kaulons (the word is a mildly derisive coastal Nakanai term, roughly equivalent to “hillbillies”) lived under a constant threat of Mokolkol raids and feared them intensely. They were eager to accompany us, they said as long as they weren’t expected to fight. They had no recent information of their predatory neighbours’ movements and had never ventured into enemy territory. The two survivors of the Kasalea raid flatly refused to move from Baia: they said they preferred to wait and see what happened to us.

I spent the afternoon giving firing-practice to the police, explaining to them the nature of the job, allotting positions in the column-of-route (a bush patrol necessarily moves in single-file, and rearguard duty is particularly important), and rehearsing the tactics to be adopted in the improbable event of our being attacked whilst on the march. Apart from the corporal and my old friend Bosi, the detachment comprised youngsters not long out of the training-depot.

Meantime Chris had made up the stores into man-loads, packing rice into the few rubberisedbags we had managed to cadge, and using leathery bark sheaths of the limbom-palm to waterproof the remainder. He had borrowed a couple of new sanitary-pans from the Rabaul sanitation depot galvanised drums with rubber-lined, clip-on lids and they proved ideal containers for sugar, salt, and tea.

At sundown Bill Heather Forest Officer arrived back in the Ulamona Mission launch, piloted by Father Stemper, late of Columbus, Ohio. They brought 20 more carriers, two fine Spanish mackerel picked up along the reef, and my garrulous old friend Moite, the luluai of Ubili, who had served on several Mokolkol expeditions in his youth. We ate the mackerel and listened to Moite’s tall stories.

The Father left at moonrise, after staking a claim to salvage rights over all Mokolkol souls.

After posting guards, I sent Bill Heather a note, telling him to cache part of the rice and have the main party carry up as much water as possible. The carriers arrived in high spirits and were even happier when they sighted a large heap of beautiful taro-corms. In New Guinea society, to eat our enemy's food and sometimes his person is to imprint the seal of victory. Besides, they were tired of rice.

Thick bush covered the slopes on three sides of the tiny clearing, and, remembering Penhallurick’s unfortunate experience, I set the line to building a crude anti-blitzkrieg fence. They needed no urging and finished the job by sundown.

There was some minor excitement when eight pigs, seeking their evening meal, appeared silently out of the darkening bush. Moite importuned, and Tolat longingly drew beads, but I was adamant; after sniffing at us briefly, the hogs vanished as silently as they had come. We did not sight them again.

In the meantime, to forestall looting, Chris concentrated all the village chattels in one hunt. The articles indicated a typical Bainings culture: crudely utilitarian. Except for a few beaded armlets, probably stolen, personal ornaments were singularly lacking; nor were any implements decorated with the magic motifs’ beloved by the artistic Melanesians. There were no cooking-vessels, food being either baked in the fire or roasted in pits between layers of heated stones. Bamboo water-carriers and lime - containers, string - bags, expertly constructed flexible wicker-baskets, oyster shell and obsidian taro-scrapers, digging-sticks, crochet-hooks wrought from the wing-bones of flying-foxes, a few stone adze-heads, a doughnut-type stone club-head, slings and water-rounded sling-stones, torches of congealed canarium-almond sap, and lengths of limbom-palm pith impregnated with sea-water, made up the household goods of local manufacture.

Wooden spears apparently had been discarded in favour of looted coastal pig-spears, made from steel rods, and mounted in bamboo handles. One of these, bound with U.S. Army telephone-cable, was newly made, and I set it aside.

Curiously, for raiders addicted to attacking people in gardens, there were very few knives, but this deficiency was more than compensated for by the hamlet’s wealth in axes. We counted 42 of them, mostly light tomahawk-heads. Many were worn-out, their temper destroyed by fire. Others were highly polished, razor-sharp, and mounted on straight limbom handles 4ft. to 5ft. in length. These were the fighting tools with which the Mokolkols had hacked out their legend. We searched in vain for whetstones.

The amount of freshly harvested taro in the village, while surprisingly large, was dwarfed by the quantities of nutritious canarium-almonds stored away in string-bags: Bill Heather calculated a total of six hundredweight of nuts. In addition, there were cooking-bananas, sugarcane, wild betel-nut, and pit-pit tops; a few joints of smoke-blackened pork hung from the roofs. Our hosts lived well. “They wanted to stage a feast for us,” said Bosi, “but we arrived too soon.” We had nobody able to understand the captives’ language, so could only guess at the import of some brief, spirited harangues delivered by the older man. It appeared that he wished us to release him.

His superbly muscled friend, similarly full-bearded, and clad in a palm-leaf breechclout, remained morosely silent, glaring steadily at us with murderous bloodshot eyes. Whenever he thought he was unobserved he sawed industriously with a flake of obsidian at the handcuff linking him to his companion. They did not smoke, but avidly accepted some of their own kabibi the wild betelnut.

The woman, aged about 25, short, plump, and round-headed, with an intelligent face, sported bunches of leaves fore and aft. She carried a baby girl, perhaps six months old, in a sling, and two of the three small boys apparently belonged to her.

On the slim chance that some of the people might still be lurking by, I decided to remain in the village for as long as the rations permitted. During the next day, after confirming that there was no potable water in the immediate vicinity, I kept all hands, except an escorted water-party, within the village. The police and carriers built a fine cookhouse and several latrines, including special arrangements for the lady. We learnt the captives’ names by calling our own whilst tapping ourselves on the chests in turn, then tapping them to the accompaniment of interrogative grunts.

The woman, named Manu, was easily the brightest pupil; during the day she became increasingly confident and even voluble. By indicating us, then making a circular motion with her hand, whilst pointing sky-wards and simultaneously emitting a growling noise, she demonstrated that she connected our arrival with the aerial reconnaissance. I abandoned a half-formed plan to release her and the children. She was going to be valuable.

The hamlet (or the mound on which it was built) was called Atar, which, after some mystifying pantomime by the lady with a strip of salted limbom-pith, we ultimately deduced meant “salt-water”: in clear weather a shimmering patch of distant sea was visible through a gap in the western ridges.

The elder man, Malil, became spasmodically co-operative, and was persuaded to join with Manu in directing some fruitless yodelling at his absent friends. Of course, we had no check on what they said. Their sombre companion, favoured crop, interspersed with a few clumps of sugarcane, bananas, and aipika spinach.

Work had evidently been in progress when the raid occurred a point from which old Moite derived peculiar satisfaction. “For years and years these Mokolkols have raided people working in their gardens,” he said, contemptuously squirting a crimson jet of betel-juice over a banana-trunk. “Now they know how it feels.”

Careful circling of the rain-washed ground indicated that, in traditional style, the Mokolkols had fled to distant parts, and that it was useless to wait longer.

The following morning, after leaving some trade goods prominently displayed, we commenced the return journey to Baia. The lady was placed in old Moite’s care; she walked in front of him, with a length the formidable Lamu, remained grimly uncommunicative. I suspected that he was suffering from fever and had been asleep when we raided the place. He could not be persuaded to swallow any tablets, and when, rather foolishly, I endeavoured to take his temperature, he promptly chewed-up our sole remaining thermometer.

Next morning we patrolled the area, without observing any signs of lurking humans. The gardens, 1000yds. from the village, were about five acres in extent, unfenced, and had been carefully tended. Taro, of extremely good quality, was the of light cord fastened around her waist and tied to his wrist. Risks had to be accepted during the intervals, including the daily changes of floral raiment, when ladies must be alone, but these were minimised by temporarily relieving her of the baby. The small boys, aged between four and eight, climbed the ridges with a nonchalant ease that put us to shame.

We made good time, working on a compass-bearing, and finally pitched camp, in heavy rain, on one of the Mavulu tributaries. There was a momentary panic when one of the kaulons, seeking firewood, wandered some little distance off in the gloom, and was mistaken by the nervous Nakanais for a Mokolkol. During the evening meal one of the small boys tearfully bemoaned the lack of pork (the word for pig boro, boroi, boroina, etc. is curiously similar in every New Guinea language). His irritated mother swiped at him with a piece of burning firewood, which he dodged with practised dexterity. Vocational training of the Mokolkol young apparently started at an early age.

When, late in the second day, we reached Baia I sent for the two miserable little Kasalea men. As expected, they swore they recognised the prisoners: under cross-examination their identification became increasingly suspect: only one of them had been near the scene of the murders, and he had got away to a flying-start. As they fidgeted, searching for more convincing lies, their attention became focused on the new iron spear with the telephonecable binding, which had been tossed, with careful negligence, into a corner of the rest-house veranda.

Then the older man, Anuti, sulkily spoke up: “I would like that spear.” Ask the luluai here to sell it. The Lulai had made it.”

“No, he didn’t. My wife's brother, Kipu, made that spear two months ago, and gave it to Pagoni, the second son of my kinsman Timoni.”

He gave a lengthy discourse on the weapon’s history.

“All right. Tell Pagoni he can come to Rabaul and get it.”

“The Mokolkols killed Pagoni and his daughter.”

I gave him the spear.

It had established that our Atar friends were the South Coast raiders.

Bill Heather’s15 Adventures with the Mokolkols in East New Britain

THE District Officer of Rabaul (Mr. J. K. McCarthy) has stated that an air reconnaissance of the mountain territory of the elusive Mokolkol peoples, on the island of New Britain, has just been completed, and a village has been observed. A patrol will be sent out to try to contact these natives.

The Mokolkol is a fierce nomad tribe, which has consistently evaded capture during the entire years of the Europeans’ rule of New Guinea. The only Mokolkols ever captured are children, abandoned by their parents in flight. There are believed to be two of them at present in Rabaul, now grown up, who were captured in this fashion. These young Mokolkols, it was hoped, could be trained, and sent back to their village to civilise their own people but under the influence of civilisation they soon lost the Mokolkol tongue.

These fierce natives hunt with a primitive axe, descending upon a village and leaving a trail of dead behind them, then disappearing again into the surrounding hills, where they live in temporary camps. Other New Britain natives live in mortal fear of the Mokolkol.

Three editions of The Bulletin detailing capture of Mokolkols

1950 (November)16

195017

A SUCCESSFUL patrol has been carried out in the Mokolkol country, in the region of Open Bay hinterland, on the island of New Britain. Seven Mokolkols were persuaded to return to Rabaul with the patrol, which was led by acting ADO Fienberg, accompanied by Cadet PO Normoyle (Junior), and Forestry Officer [Bill] Heather.

The “captives” consisted of two men, one woman, and four children. The men are about 33, and 38 years of age and therein lies the tremendous success of this patrol. Previously only aged men, women, or children have been picked up by expeditions into the Mokolkol strong hold. They said that there is only this one Mokolkol village, containing twelve males, one youth, eight adult females, and about ten children. It seems incredible that this tiny band of hill-people should dominate and terrorise, as they do, about 500 miles of country.

The natives will be taught Pidgin and in a few months’ time it is hoped to send them back to their village as proselytes of civilisation.

195118

Meet the Mokolkols. The Ned Kellys of New Britain -from a Special Correspondent

15 PNGAF Mag Issue # 9B-5B4H5 Eminent TPNG Forester Bill Heather 1947-1954 of 17th April 2024.

16 The Bulletin. Vol. 80 No. 4134 (6 May 1959); The Bulletin. Vol. 80 No. 4135 (13 May 1959); The Bulletin. Vol. 80 No. 4136 (20 May 1959)/

17 Pacific Islands Monthly: PIM.Vol. XXI, No. 5 (Dec. 1, 1950)

18 Pacific Islands Monthly: PIM.Vol. XXI, No. 6 (Jan. 1, 1951)

Meeting the Mokolkols has been quite a job for the Administration of Papua-New Guinea, for this brown-skinned, Ned Kelly tribe has been successfully dodging Governmental authority for about 30 years.

In that time, they have raided and murdered far and wide in the country near the base of the Gazelle Peninsula, in New Britain until the mere name “Mokolkol” tends to cause panic among neighbouring tribes. In fact, they have few neighbours, for the latter tend to clear out and leave these New Britain hillbillies in undisputed control of about 500 square miles of countryside.

Patrols went out intermittently over the years to round up these anti-social Mokolkols, but never succeeded in really getting to grips with them. Sometimes there was a bit of a skirmish, but on most occasions, the natives just skipped into the jungle and faded out, like a conjurer’s rabbit.

These fierce natives hunt with a primitive axe, descending upon a village and leaving a trail of dead behind them, then disappearing again into the surrounding hills, where they live in temporary camps. Other New Britain natives live in mortal fear of the Mokolkol.

1950 (November)19

Three editions of The Bulletin detailing capture of Mokolkols

195020

A successful patrol has been carried out in the Mokolkol country, in the region of Open Bay hinterland, on the island of New Britain. Seven Mokolkols were persuaded to return to Rabaul with the patrol, which was led by acting ADO Fienberg, accompanied by Cadet PO Normoyle (Junior), and Forestry Officer [Bill] Heather.

The “captives” consisted of two men, one woman, and four children. The men are about 33, and 38 years of age and therein lies the tremendous success of this patrol. Previously only aged men, women, or children have been picked up by expeditions into the Mokolkol strong hold. They said that there is only this one Mokolkol village, containing twelve males, one youth, eight adult females, and about ten children. It seems incredible that this tiny band of hill-people should dominate and terrorise, as they do, about 500 miles of country.

The natives will be taught Pidgin and in a few months’ time it is hoped to send them back to their village as proselytes of civilisation.

19 The Bulletin. Vol. 80 No. 4134 (6 May 1959); The Bulletin. Vol. 80 No. 4135 (13 May 1959); The Bulletin. Vol. 80 No. 4136 (20 May 1959).

20 Pacific Islands Monthly: PIM.Vol. XXI, No. 5 (Dec. 1, 1950).

195121

Meet the Mokolkols. The Ned Kellys of New Britain. From a Special Correspondent

Meeting the Mokolkols has been quite a job for the Administration of Papua-New Guinea, for this brown-skinned, Ned Kelly tribe has been successfully dodging Governmental authority for about 30 years.

In that time, they have raided and murdered far and wide in the country near the base of the Gazelle Peninsula, in New Britain until the mere name “Mokolkol” tends to cause panic among neighbouring tribes. In fact, they have few neighbours, for the latter tend to clear out and leave these New Britain hillbillies in undisputed control of about 500 square miles of countryside.

Patrols went out intermittently over the years to round up these anti-social Mokolkols, but never succeeded in really getting to grips with them. Sometimes there was a bit of a skirmish, but on most occasions, the natives just skipped into the jungle and faded out, like a conjurer’s rabbit.

But in November of this year a patrol led by Assistant District Officer D. M. Feinberg, of Rabaul, with Cadet Patrol Officer C. Normoyle and 12 native police, finally tracked down the Ned Kelly hide-out. A Forestry officer, Mr. W [Bill]. Heather also accompanied the patrol.

They got within a few feet of the first house before first a pig and then a woman gave the alarm. The patrol immediately closed in, and two bearded warriors tried to bolt from their huts. But a shot into the ground at the door of one of the buildings dissuaded one black gentleman, who was then disarmed, and the other retreated indoors.

The first had obviously meant business, for he had a long-handled axe in each hand, and plenty of ability to swing both at once. The patrol picked up the second man, and a Mokolkol woman and four children before the villagers got away into the jungle.

These Mokolkols are now in Rabaul, learning Pidgin, as a preliminary to being taught to live in peace with their neighbours and the world in general.

A word about the history of these people. It seems that some 30 years ago they came from the general direction of the Bainings area; and, perhaps because of a quarrel or for some other reason, they took to the mountains between Wide Bay and Open Bay. There they have lived as nomads, making temporary gardens and raiding, with berserk ferocity, isolated natives working in the gardens of adjoining settlements.

Their ferocity, and the superb bushcraft which enabled them to appear and disappear at bewildering speed, added to the ill-repute gained by their wholesale slaughter, made them dreaded, for miles around. Not a native would wander knowingly within their area.

21 Pacific Islands Monthly: PIM.Vol. XXI, No. 6 (Jan. 1, 1951)

It appears that they raided mainly for axes, which apparently are not only their chief weapons but an important part of their culture. A search of the village showed that these are all of the tomahawk type, of Australian or American manufacture, and fitted with native-wood handles four or five feet long. They swing these with deadly effect, and they also use them on less murderous jobs for which other natives normally use knives. The axes are sharpened on whet stones to a razor edge; and this process is never allowed to be watched by the women of be tribe.

The two Mokolkol men taken by the patrol are both comparatively tall and well built, and both are bearded, one 33 years and the other 38. The woman is of the Baining type, with rounded head and a plump body. She is described as being extremely voluble and quite intelligent It was found that the Mokolkol language was somewhat similar to another dialect of Baining origin, and it was possible to get a halting and stumbling interpretation through the language of this second group.

THE patrol, working on preliminary information from the Mokolkols taken to Rabaul, and subject to later check ascertained that the entire Mokolkol group now numbers about 30, including women and children, and that the numerical strength of the tribe has been declining for some years. It is regarded as astounding that this small group should have built up such a reputation and spread such fear through so large an area. Even natives in quite distant areas regard the mere name of Mokolkol with dread.

The little group at Rabaul expects to be able to make contact with the rest of the tribe when they return home. They will be sent back after a short time, accompanied by a patrol to ensure their safe acceptance by the tribe, and it is hoped that they will be the means of establishing permanent contact with the Administration. If so, the solution of this tough little spot of trouble will be only a matter of time.

Meanwhile, it would be interesting to know what these wild folk of the hills think of civilisation and the strange new world to which they are being introduced. Perhaps, with increasing knowledge of Pidgin, they will be able to express their views before they go home.

MeetingtheMokolkols:JimToner2002

Obligated to report annually to the United Nations on its Trusteeship of the Territory of New Guinea, Australia in 1951 mentioned inter alia that “For more than a quarter of a century, the Mokolkols have been known to the Administration as a small band of primitive nomads living in the country at the foot of the Gazelle Peninsula. They have enjoyed a notoriety disproportionate to their slight numerical importance through their long-standing habit of raiding outlying hamlets, wantonly butchering men, women, and children, and disappearing without trace”.

Heaven knows what tut-tutting this caused in the big building on Manhattan Island but in fact remedial action had already been taken. David Fienburg of the Department of District Services & Native Affairs led two patrols to the Mokolkol homeland and at the Waigani Seminar of 1968 he presented a paper detailing his experiences. By that time, he had, in what Jim Sinclair described (in his book Kiap) as a most uncharacteristic action, changed his name to Fenbury. Whatever the nomenclature his estimable command of the written word would normally deter me from tampering with his text. However, the Mokolkol story is overlong for Una Voce, and I therefore attempt a summary.

In 1938, raids by this small group of axe-lovers took the lives of 20 persons resulting in the establishment of a police post at Pomio. In 1940-41, 26 people, mostly women and children, were butchered by the Mokolkols. The war intervened and it was not until July 1950 that notification was received by the Administration that the predatory group still existed. This was contained in a signal from Pomio stating that the Mokolkols had raided an outlying hamlet killing nine inhabitants.

Subsequently Fenbury took a respite from organising Local Government for the relatively sophisticated Tolai and in November mounted a patrol consisting of 10 constabulary, Cadet Patrol Officer Normoyle, and Bill Heather of Forestry Department. The trawler trip to a spoton Open Bay was no problem. After that there was a 500 square miles tract of mountainous virgin bush shunned by natives and expatriates alike. Carriers were engaged, also an aged luluai from the Nakanai who had served on Mokolkol expeditions prewar, which brought the patrol’s strength to 54.

Then follows what I suppose could be called a layman’s guide to PNG “patrolmanship.” Much detail as to preparations, equipment, and arduous movement towards the notional camp of the subject group is provided. Fenbury reveals that the cadet had brought an Owen submachine gun with him against the remote contingency that stranded Japanese soldiers might be encountered in the rain forest.

22 MeetingtheMokolkols:JimToner22.BY PRESIDENT SEPTEMBER 16, 2015. (Published Una Voce, September 2002, page 33) Jim Toner: Chief Clerk, District Office, Mendi 1957-59; District Office, Rabaul 1960-64; Field Manager, New Guinea Research Unit (ANU), Port Moresby 1965-73

On the sixth day the tiny village was found and two men, one woman and four children were captured. After examining the 10 huts on site, Fenbury estimated a total population of less than 30. However, he counted 42 axes. Many were worn out, but others were highly polished, razor sharp and mounted on black limbom-palm handles some four to five feet in length. These were the unique tools with which the Mokolkol had hacked out their legend.

Of the men, a huge bearded fellow when winkled out of his hut made signs for the patrol to kill him there and then. Spared, and then quartered at Nonga outside Rabaul for six months, his eyes never lost their baleful stare. Both he and the older man, Malil, were initially as suspicious as newly caged animals and inclined to mope, but the latter adapted and Fenbury says that he had a sense of humour and some histrionic ability. He says, “On the Mokolkol’s first visit to the crowded Rabaul market, Malil had quickly detected the element of awe in the intense interest shown by the Tolais.” (Recalling for me the audible silence of the crowd surrounding but standing well back from a handful of Kukukukus brought to a Hagen Show.)

Fenbury goes on: “Surrounded by a respectful throng and excited by the noise and sight of the fabulous wealth in food displayed, Malil had suddenly embarked on an impromptu little song and dance act whose culminating point was a liberal sampling of whatever took his fancy. The owners declined to press for payment, and he finally staggered off with a huge load of fruit and vegetables.”

The woman, the brightest of the adults, learned some Pidgin but suffered tragedy when her youngest boy was admitted to hospital for dysentery. Fenbury says, “His condition was not considered serious, but he suddenly took a turn for the worse and died. It was then discovered that his mother, stubbornly fearful that he would starve to death on a liquid diet, had filled him with chunks of half-cooked taro which she had smuggled into the ward. She wept bitterly for two days and then with the stoicism of her kind appeared to forget the child completely.”

In May 1951, Fenbury and Normoyle repatriated the Mokolkols to Open Bay and while holding the woman and three remaining children at the beach released the two men (issued with axes without which they would have felt much as you or I am walking naked down Pitt Street). Their instructions were to bring the rest of the group “in from the cold”. A week later they returned with six other men to engage in what was probably the first amicable intercourse the Mokolkols had ever conducted with stranger.

Fenbury again: “The ice was broken when I presented the woman’s husband, Mulau, an impressively rugged fellow, with a new three-quarter axe with a hickory handle. His reunion with his wife and family had amounted to one or two casual grunts but the axe proved too much for Mokolkol reserve. The wild men patted it lovingly, laughing gaily and chattering at frantic speed in their high-pitched unpleasantly nasal dialect. Mulau tested the blade by taking some tremendous swings at a tree. After a few others had done likewise they sat down, and we conversed painfully of many things. But the axe was infinitely more attractive than any official discourse. At intervals, as though succumbing to sheer rapture, one of the Mokolkol would leap up, seize the tool, and try a few more strokes.”

The outcome was that the Mokolkols said, “We won’t raid anymore … now we know where the axes come from.” And seemingly they did not. By 1968 the group had moved to live alongside Bainings people at Matanakunai, had gained some wealth through sale of timber rights, and occasionally visited Rabaul in outboard-powered canoes! Their 1950 practice of killing women in raids instead of stealing them though short of breeding females themselves did not bode well for the future. Intermingling with Bainings would obviously alter their culture but it would still be interesting to learn their current status a half-century after David Fenbury’s expedition tracked them down.

A Mokolkol Sequel23 by

Des Harries24

Having read D.M. Fenbury’s paper, ‘Meeting the Mokolkols, New Britain 1950-51’, Fenbury’s story captured well the flavour and atmosphere of the time and place. It made me recall my experience at the end of it.

When I first arrived at Keravat, the Forest Station on the Gazelle Peninsula, in about April 1957, the Mokolkols were still ‘the talk of the town’. I think everyone at Kerevat, located as it was on the edge of Mokolkol country and really at the outer boundary of the Australian Administration’s effective area of influence on the Gazelle Peninsula, frequently felt that a big, bad, Mokolkol may be lurking just inside the edge of the vast forest surrounding us. But no-one ever saw one.

When I was next stationed there, after the rest of my cadetship year, plus two years at the Australian Forestry School in Canberra, and then two-year posting in Wau followed by a period of recreation leave in Queensland, the talk had virtually died down.

The Tolai people had continued to develop their strength but were still very much tied to the Gazelle Peninsula with a focus on their major market town of Rabaul. But as we developed our forestry area, with its network of good roads, I could not but feel the subtle pressure of these people, equipped with their village trucks, putting out exploratory feelers towards the Bainings.

The Territory of the Bainings people lay in the hilly country just beyond the limits of the Gazelle, and as it happened, the acid volcanic pumice soils of that area. In the Kerevat area the forest, untapped until now, had been a ‘no-man’s land’ between the two cultures. My understanding, which may bear checking, is that the original Administration land purchase in this area, post-World War 2, was from Bainings people, who regarded this purchase as one way of establishing a barrier between themselves and the expansionary Tolai.

In the next valley out from Rabaul, that of the Vudal, the country adjacent to the coast of Ataliklikan Bay and extending some miles inland had been purchased during the pre-World War 1 German administration. This land had been left deserted until the period of my posting at Kerevat, in 1963-65. Our major road development through the area known to us as the Trans Vudal, now brought us within fairly easy walking distance of the nearest, and probably major, centre of activity of the Bainings people, high on their hills overlooking the valleys of the Vudal and the Kerevat rivers, and the great sweep of Ataliklikan, towards the volcanic rim of the Rabaul caldera, the centre of the rival Tolai.

A year or so later I was posted into Rabaul, firstly as Acting Regional Forest Officer, then as the Regional Forest Management Officer.

23 PNGAF Mag Issue 9B-5B4H3 of 24th June 2022. Eminent TPNG Forester Des Harries 19551976.

24 Personal communication Des Harries 21 February 2023

This Region was vast, embracing not only New Britain, but also New Ireland, Manus, and Bougainville, but much of my focus remained, of necessity, on the commercially active timber area of the New Britain north coast. Pressures were now rapidly building within the Territory for economic expansion, and at the same time, the market for New Guinea timber, practically all as logs, was starting to boom in Japan.

The coastal country, easy pickings for small operators, had largely been taken up with relatively minor “timber permits” based on fairly small “timber rights” purchases.

Bill Heather, who features in Fenbury’s paper, had done very well in East New Britain. By the time I first arrived at Kerevat, he had departed, probably five years, and become the lecturer in wood technology and forest pathology at the Australian Forestry School in Canberra where we had first met. Yet, amazingly, his influence was still present, and especially in the camps of the Bainings people. After all these years, his established trust was still encountered in my dealings with native timber interests.

The Mokolkol sequel happens here. As Fenbury relates at the end of his paper, on advice from District Commissioner, Harry West, the remaining clansmen were now settled adjacent to the northern shores of Open Bay. Prior to the following incident, I had been along that coast in a Government boat looking out keenly for signs of life where I expected there to be but had seen nothing.

As it happens, during the pre-World War 1 German administration, two land purchases on the shores of Open Bay had been made, vested in the Roman Catholic Mission. One of these was quite a large block. They were now deserted, but as the freehold title was still honoured by the Australian Administration, we had no control over the exploitation of the timber on these blocks.

In fact, they were a niche in my armour, as I embarked on a strategy to squeeze out the small, nuisance operators along this coast in order to allow the implementation of some major timber resource development plans.

A very canny timber logger found this niche and purchased the timber from the Catholic Mission. He was a hardworking and basically honest operator, and we got on very well.

But one day as I sat in my office in Rabaul, word came via a Bainings runner across the mountains from Open Bay, that the logger had breached the boundary of the Mission land and cut some trees belonging to them. I still feel the sense of amazement experienced then, that this could happen.

.

A few days later, the logger came into my office, having travelled around the coast via. speed 25boat. He, naturally enough, was also amazed to learn that I already knew of his indiscretion. He explained that he had not been able to locate all the boundary markers, and, assuming a straight line between some that he had found, had fallen some trees which proved to be outside.

I immediately dispatched John Clark, a young English forester working in my resource assessment team, to investigate. John did an excellent job of sorting out the boundary, although we could never really explain the odd shape of the boundary where our logger had gone wrong. All those years ago, near the turn of the century, the boundary must have made a detour to avoid a special tree, or a special piece of ground; we shall probably never know. But it not only illustrated the strong feelings of this small and isolated group of people to their territory, but the amazing tenacity of their oral tradition which kept this concern accurately in place.

And, in conclusion, I think it is reasonably accurate to conclude that by the time of the incident outlined above, the former outlawed and troublesome Mokolkols had finally been well and truly reabsorbed into their Bainings mainstream.

A possible sacred tree in Open Bay TA.

Photo credit Ian Whyte 1974.

Ken Granger’s Experience with the Mokolkols

:

On this part of the survey, we had the first of the nationals to graduate as TOs from the Forestry College at Bulolo so there was an early emphasis on training and checking their work. Among the first graduates to join the survey effort were James Isorua, John Toropis, Jenship Wazob and Missi. John Lake had been replaced (I think) by Rex Grattidge and Robin Hosking had gone on leave.

After establishing our first base camp at Malalia United Church Mission around the coast from Cape Hoskins, Neil Brightwell and I began our reconnaissance flights mostly into the interior of the island – i.e., along the route of the proposed “Bill Suttee Highway” that Rod Bartlett and I had been mooted to survey in 1964. Our pilot was, once more, Peter Hurst.

Our second base was at Bialla further to the east. We set up the camp along the beach front and the office in a haus wind right on the water. There was a log export operation under way just next to the old Bialla Plantation.

The Bialla office and pad, 1965. Photo credit Ken Granger.

After a reconnaissance into the Nakanai Mountains it was decided that we needed to get some strip lines into the Nothofagus forest on the Plateau. There was a very dicey pad on the edge

26 Extract pages 30-33 of PNGAF Mag Issue #9B-5B4G1 Eminent TPNG Forester Ken Granger’of 22nd July 2021.

of the plateau at about 5500’ ASL that would need to be improved before it was safe to send in teams. Keith Pearson and I with two labourers went in with minimal gear to fell enough Nothofagus to improve the pad. After felling a couple of trees, the chainsaw packed it in, so it was then into the work with axes. Once the moss and mulch of decades of leaves were cleared from around the base it was somewhat easier to fell the trees by cutting out their roots. A slow and rather hairy approach but it worked. We took the opportunity to do detailed log measurements and investigate defects.

Our third camp was at the Ulamona Catholic Mission and sawmill. The office and mess were again combined under the one structure. It contained a working space for the maps and air photos as well as the Crammond transceiver that we now had available to communicate to the outside world (via Rabaul Radio). Its call sign was VL8PN. We had also acquired small, transistorised HF radios for the field teams so that regular schedules could be had with the field teams to give them updates on pickup times and so on and for them to call in if there were problems such as sickness or injury.

The mission was at the foot of Mt Uluwun (The Father), an active volcano. The sawmill sourced most of its logs from the stands of kamarere that grew on the old blast areas around the base of the mountain. The mill was steam powered and supplied all of the mission needs for sawn timber throughout New Britain. It was a well-run establishment managed by German lay brothers.

We had a visit from a volcanologist from the Rabaul Volcanological Observatory, Dr Giani D’Addario, during our stay at Ulamona. He had arranged for the use of our chopper to survey Ulawun and he and an assistant were lifted to the rim of the crater at over 7000’ by Peter Hurst to make their observations. Giani worked for the Bureau of Mineral Resources (BMR) in Canberra and had a rather interesting Northern Italian accent.

Returning from one of our reconnaissance flights “Thirsty” flew past the rim of the Ulawun crater before doing an autorotation onto the water in front of Ulamona Mission – i.e., he throttled the engine right back and “glided” down. I enjoyed it but I do not think “Brighteyes” did.

ItwasaSaint’sDaythedaywewereduetomoveontothenextcampatMatanakunaiPlantation,sothe Brothersinvitedustohavebreakfastwiththembeforeweleft.Breakfastconsistedofapeanutbutterjar threequartersfullof Bavarian brandyandablackcheroot!Thethoughtwasappreciated.

The Matanakunai camp was on a new plantation, and we had the use of the plantation house for our office. Our pilot for the first time was Bill Wallace, an ex-RAF fighter pilot. He became something of an institution on future helicopter surveys.

Matanakunai Plantation, June 1965. Photo credit Ken Granger.

Three events stand out from that camp. First, one of the TOs, with his team, caught a 2 m crocodile just near their fly camp. They radioed in requesting permission to bring the croc back on the chopper and Bill was happy to do that as long as it was well trussed up.

The second was that we appeared to have sparked a cargo cult in the southern Baining Mountains where the Mokolkol people lived. They were a semi-nomadic group that had had very little contact with the outside world, and it seems that they saw the chopper operating in and out of a small pad in their area with our teams and so started the “Golden Egg” cargo cult.

The third was receiving the news via telegram that my father had passed away. It was not possible for me to realistically get from Matanakunai to Goulburn (NSW) in time for the funeral, so I stayed in the field.

An Example of a Timber Rights Purchase: Chris Borough

An Example of a Timber Rights Purchase: Chris Borough2728

A few months of Chris’s life as a Forest Officer in TPNG

This was but a small part of Chris’s experience as a Forest Officer in TPNG – an experience that made a lifetime impression on him.

It was September 1967 and Chris’s first Timber Rights Purchase – Collectively known as East New Britain TRP from memory. Jim Cavanaugh from HQ at Konedobu knew of Chris’s assessment experience in New Britain and gave him the task of organising a Timber Rights Purchase (TRP) covering an area from Wide Bay to Open Bay. It was a rapid learning process. The purchase of the Right to harvest timber was being used as a method of securing timber resources without the need to purchase land – land purchase was a concept that was totally rejected by the traditional owners across the nation. It was around this time that the Mandated Territory of New Guinea was under increasing scrutiny by the United Nations and activities that had once been taken for granted no longer applied. One of the constraints was that money could not be withheld to be paid over a longer period of time. Also, every person who was identified as an owner would need to be identified and their consent agreed. In addition, the money paid for the Purchase would have to be distributed in accordance with the area owned. For a Timber Rights Purchase this meant that Chris would be responsible for handing out a considerable amount of money and would need an accurate assessment of area by clan.

The project required a range of skills – few of which were part of Chris’s forestry training! A helicopter was hired from Helicopter Utilities with Bill Wallace as pilot and Brian Turner as engineer. Other staff on the project included Gary Flegg (draftsman) and Dave Num (Forest Officer) and local staff Technical Officers/TechnicalAssistants. The project would require legal assistance in the field and Patrol Officer (Kiap) Bob Willis was appointed. In addition, they needed a typist as the legal documentation required very accurate typing with NO mistakes as well as a lot of skill in translating names. As Chris recalled, the trickiest name to be translated from tok ples was a clan leader that he translated into English as Manas Lariangsenggerriu.