6 minute read

Decarbonisation: BOC Industrial Gases

Can hydrogen solve the sector’s decarbonisation plans?

Industrial gases company BOC is a key provider of the UK’s hydrogen needs for industry and recently took part in successful trials at NSG Group’s St Helens, UK glass manufacturing plant. Wayne Bridger* describes how hydrogen could be the answer for glass’s problems, but it may take at least 10 years before adequate infrastructure is in place.

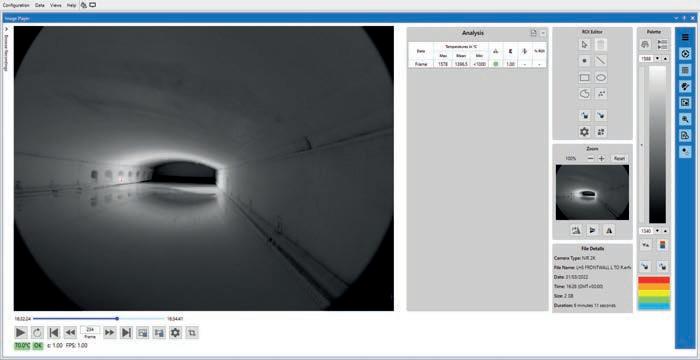

Flat glass manufacturer NSG group recently completed successful hydrogen trials at its Pilkington plant in St Helens, UK. The trials lasted for three weeks and had the aim of firing the furnace with 100% hydrogen with the quality of the manufactured glass unaffected. The trial resulted in a world first – the production of float glass using hydrogen

operates fi e h rogen pro ction facilities in the

The company mobilised 100 trucks to supply the NSG facility for its hydrogen trials.

The trials were part of the Hynet Northwest Fuel Switching Scheme - a UK-government funded scheme - to demonstrate the feasibility of switching several industrial processes from natural gas to hydrogen.

Pivotal to the success of the trial was the reliable supply of hydrogen from gas group BOC. The company is part of the Linde group and operates the largest network of gas production facilities across the UK. It operates five hydrogen production sites, in Margam, Barry, Newport, Teesside and one close to the NSG glass manufacturing facility in St Helens.

BOC’s role in the trial was to demonstrate that it could deliver enough hydrogen on a large scale for NSG. The organisation had to mobilise its supply to provide enough hydrogen for the entirety of the trial. At one point, when demand for hydrogen from the glass plant was at its peak, BOC provided a truckload of hydrogen to the facility every hour.

As Wayne Bridger, BOC UK and Ireland’s UK sales manager of decarbonisation and hydrogen applications, states, no other company in the UK would have the capability to mobilise a supply chain to do the trials and deliver what it did.

The group had been involved in hydrogen trials in other sectors such as cement, minerals and wine before but the one at NSG was its largest.

At its peak, NSG required about 3000 m3 an hour of hydrogen. The hydrogen was supplied from BOC’s production sites to NSG in its trucks, which have a typical capacity of 2800 m3. The company has 75 trucks in the UK so mobilised about 100 trucks from its European division to keep up with demand.

The trial presented several engineering challenges. BOC’s trucks had to be converted to carry 10 bar instead of

their usual 228 bar gas. Inside NSG’s facility, two seven-metre-high skids were constructed to help with ventilation due to hydrogen’s dispersal rate and flammability characteristics.

Mr Bridger said discussions about the trials started in 2018 and did not start until 2021 – although this was partly due to the pandemic. Planning of the trials took over a year

“If a company is considering embarking on a decarbonisation journey, it is worth saying the engineering and interface discussions for the trial lasted at least a year. These are not quick decisions, it is a thoughtful process. We were in the fortunate position where we could dedicate a small engineering team to the project because it requires a substantial engineering effort to do these things well.”

He added: “Summarising that journey, you need a lot of resources, and a lot of production, distribution and engineering capability to enable substantial trials to go ahead.”

Future

Looking ahead, Mr Bridger said BOC currently had enough hydrogen capacity to help run two or three average sized container glass plants in the UK.

“It gives you a sense of the scale in infrastructure required. I talk to a lot of people in industry and I repeatedly hear the weight of expectation in the future. There is almost a utopian view of the future where hydrogen will come along and solve our problems.”

But this utopian view is challenged by increased energy price volatility, likely higher energy costs and the cost of carbon compliance in future, he said.

“There is a gap in my mind between this utopian future of hydrogen that says ‘don’t worry it will be okay’ because there is lots of low cost hydrogen coming, while all the business models for hydrogen and carbon capture and carbon pricing are still in debate.

“Also, nothing is built yet. We have got this long horizon where all of this will come together but we have problems today. Somehow we have to survive this gap period between where we are today and what the future promises.

“I hear what people are quoting as the future cost of hydrogen and, well good luck, because it is going to be a long time coming. What we do know is that hydrogen is likely to be more expensive.

“We have options for the decarbonisation of industry such as hydrogen, biofuels, electrification and carbon capture but no of those are free and all require large infrastructure investment.”

He believes that, in the long term, renewable electricity will be the energy source to power the glass manufacturing industry but until then will be a bridging period where a variety of technologies will be used. Initially fuel efficiency should be a focus, with the use of oxy fuel technology and waste heat recovery before medium term technology such as hydrogen and carbon capture come into use.

Paralysis

He suggests business needs to take action quickly if they are to decarbonise their facilities in the near future.

“When I speak to industry there is this concern about a no regrets pathway, it seems industry doesn’t want to make regretful decisions about where it invests. It doesn’t want to put CAPEX into one technology which goes in one direction only to find that another technology has gone in another direction. That is paralysing industry to some extent, it is not making any decision because it doesn’t want to make the wrong decision.

“There is no single silver bullet to all of this, there are pathways which involve a number of technologies.

“It is a journey and we think the industry should be building more data and operating experience to begin to think how to begin this journey. It is lengthy and requires a lot of input from both sides but there are steps the industry could and should be taking.

“While hydrogen is part of the future we contend that other, well established technologies should be the early part of the solution.

“The UK industry will be reliant on a range of things and I guess the danger is that some of that is big, complex, expensive and long term so it needs to act now because the clock is ticking.

“People are talking about significant steps by 2030 to achieve that, so there is not a lot of time for experimentation and development, you have to start to rely on proven technology to move forward. That is the position we are advocating.” �

*UK Sales Manager-Applications at the Linde Group, BOC Industrial Gases, UK www.boconline.co.uk/en/index.html