A HOLAAfrica! Production

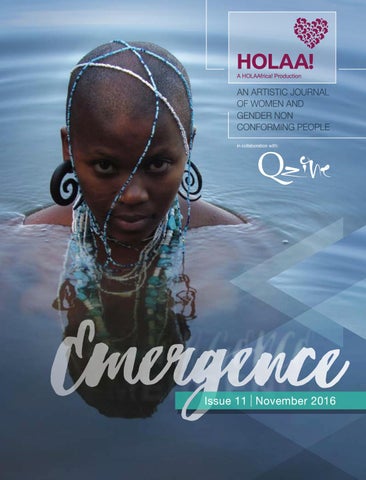

an artistic journal of women and gender non conforming people in collaboration with:

Emergence Emergence Emergence I

Issue 11 November 2016

Emergence

I

An artistic journal of women and gender non conforming people

1

A HOLAAfrica! Production

an artistic journal of women and gender non conforming people in collaboration with:

Emergence Emergence Emergence I

Issue 11 November 2016

Emergence

I

An artistic journal of women and gender non conforming people

1