Post-Travel Reflection for the Harvey Geiger Fellowship in Architecture and Lewis

P. Curtis Senior Independent Research Fellowship

Paula Toranzo Paredes, B.A. Architecture 2025

Post-Travel Reflection for the Harvey Geiger Fellowship in Architecture and Lewis

P. Curtis Senior Independent Research Fellowship

Paula Toranzo Paredes, B.A. Architecture 2025

Paula Toranzo Paredes, B.A. 2025

Across three months, I traveled to four countries: New Zealand, Japan, the UK, and Germany, capturing the social and physical state of convenience stores through in-person observation, interviews, and photography. Often overlooked, it is the transient quality of the convenience store that personally appealed to my passion for urban regeneration and my Angeleno childhood. The Latin specialty mini market down the road was essential to my immigrant experience for its convenience and cultural significance. This project seeks to address the lack of visual documentation and to legitimize the convenience store, no matter its product or software, as a small business with a valuable community presence.

I intentionally chose four countries with distinct socialization cultures, streetscapes, and broader city grids. When applying an architectural and sociological lens, themes quickly emerged not only grasping the heart of the typology but the quality I seek to carry forward in my own urban design. This research pushed me to spark hundreds of conversations with strangers. At first, they brushed off their regional typology as minimal, but through thoughtful questioning, we often ended with an acknowledgment of the childhood and daily attachment each person has to their local convenience store.

It’s 7 am on the corner of Huxley and Rogers. I pull in and am greeted by a friendly truck-side, painting dozens of cows over a green pasture, meeting the familiar Kiwi snow-capped mountains. The image’s horizon mirrors the Banks peninsula sitting behind and the perfect stillness before the morning rush. Moving my gaze to the dairyman and his cart, the thick-lettered advert for a Pepsi immediately catches my eye. Not only is it a good deal, but the signage is noticeably handwritten, and the human error in the ‘O’s warms my heart after years of freeway billboards in Los Angeles.

Mr. P moved to New Zealand over 30 years ago. Every day he prepares his chai tea with the spice proportions perfected to the point of muscle memory, there is no need for measuring

cups. As he sorts out frozen pies in the freezer, he lays out flat his and every other dairy owner’s top product. “Everyone gets energy drinks now and it isn’t good. I only need my tea to wake up, and at least I know what’s in it.” Continuing his preparation for his first customer, he draws the curtain separating the store from the ‘backroom’ or as I would quickly find out, his home. I was eager to find out more and suddenly a woman, practically floating through the door, yelled out,

No warm pies today, the machine isn’t working, but her 2 energy drinks and an extra chocolate are already waiting at the register. It reminded me of the panaderia back home and the tias who knew I wouldn’t stop at two bread rolls. Mr. P is an uncle to the community and a father to two sons. One in New Zealand, the other abroad in London, his store is named after the duo, printed in bright white letters. 90-hour weeks are typical for dairy owners, they operate on thin margins with no advantage selling at a local scale. Wholesaler bulk loads are too much inventory to handle, so owners must turn to nearly supermarket prices. Defeatedly, I ask Mr. P “Do you think the dairy will go away?”

“Never, it is central to the neighborhood.”

Every customer that flowed in over the next 3 hours was a regular. From the little boy begging for his baba for an extra gummy, to the dog and his owner settling into the day with a meat pie, even the sweaty carpool screeching the car to a halt with shotgun grabbing 5 iced coffees, this is Christchurch. More accurately, this is Sydenham, a neighborhood nestled between the CBD and Port Hills that values Mr. P and his dairy. The theme of “Homegrown” for this typology of convenience store quickly emerged from my first visit through the friendly interactions and especially the physical qualities of P and every dairy I passed on my trip.

Typically, a dairy either sits on a main road or a residential side road on a corner lot. They are single-family homes partially converted to storefronts. According to locals, it was only in the last decade that the bright-colored dairy emerged. There were some floating guesses of greater aesthetic value, a childish blue can up the charm, but on closer observation, the color corresponded to a sponsor. From cell carriers to the dairy brand that supplies milk nationally, I quickly grew an association for the brighter the color, the more advertising for a certain brand there will be. On my first attempt to find a dairy, I was met with an empty lot 2 blocks west of the CBD bus station, leveled to nothing. Connecting the dots, it makes sense that these small businesses and their geographic advantage equate to an ideal advertising opportunity. Sponsorships can support a low-margin business while advertising daily for the best cellular data plan.

Looking around P&P Dairy, a bike rack, short-term parking bays, a bench, and a rubbish bin all suggest a simple hub for low-cost, grocery and leisure food items. They are not necessarily a multimodal, public service center, no bus route passed P&P, but there is a gravitational pull to the small-town charm and regularity Mr. P offers his neighbors daily. The white

shingled home that the dairy flowers from is like every other on the block, and that’s what makes it so humble, so Kiwi. In my conversations with locals, they acknowledge the community that Mr. P has built but have their doubts, especially in a business landscape where regulations slowly tighten the grip on what is and is not allowed to be sold. It started with liquor, then a heavy cigarette tax, even the vapes sold will most likely be unsustainable for dairy owners to stock. Yet Mr. P’s rows of candy stand strong, his pie freezer completely wiped after a full day, and his conviction to support his immigrant journey and family remains steadfast. The dairy provides a means for a newcomer to extend roots into the intimate, small island socialization New Zealand still embraces. Proud of his work after my third visit, Mr. P handed me a chocolate fish as a departing gift. There was no exchange of words needed to understand the importance of sharing his and every other dairy owner’s story.

Tokyo was my next stop, On the train from Haneda Airport to Shibuya I was frantically searching for an itinerary, a list of monuments loaded. There was the Imperial Palace a while away from my next stop, isolated, and according to the reviews mostly inaccessible to the public. The Skytree viewing ran over my college student budget, and the Tokyo Tower didn’t feel entirely worth the commute. It became apparent the best recommendations instead focused on entire neighborhoods, the walking experience of looking up at the tall buildings without a speck of fat, and the abundance that consumes every corner of your line of sight, fulfilling every need. That abundance was overwhelming at first. I was searching for a 3rd-floor luggage storage place until a sweet Japanese man noted my concerned frown and led me to the right door, the right elevator, and the right floor. It isn’t just Shibuya, Ginza, and Shinjuku, each level embraces an entirely different city. The top floors are reserved for the most expensive clubs and penthouses, while the first-floor occupants scurry around on their lunch break. I didn’t even enter my first store before a pang of hunger took over and was not leaving until I found a quick lunch before my hostel check-in. Ten steps forward and before me there were three different konbiniensu sutorus, konbinis for short. Lawson, 7-11 and i-Holdings, and Family Mart, all three glowing their franchise colors even under noon’s sun.

Walking in and checking out each one, reminded me of the Trader Joe’s franchise in the States. You walk into any store, anywhere in America and you will beeline quickly to your favorite pasta sauce. Similarly, I grasped the konbini layout

quickly, hot food items are by the cashier with fried chicken always being the best option, the frozen grape juice balls in the back freezer row to relieve my summer overheating, and of course the microwave by the door for a quick exit post-heating. Well-lit and always stocked, the reliability of the konbini was easy to adapt to.

Talking with locals, the konbini was not a hangout place, far from it, instead, it was the intermediary that fueled any urban adventure. From a simple trip, A to B, home to school, or a drunken stumble from point A to F back to C at the end of a long night, the konbini occupied a physical gap in the urban streetscape and a mental gap with its formulaic layout, making sure I could buy whatever I needed, whenever I needed it. I grew an odd reliance mentality from the convenience of the konbini. I stopped packing water since the weight didn’t make sense for my long days out, especially when an ice-cold bottle was guaranteed within a 2-minute walk.

As I continued, I noticed most buildings were 50 years or younger, Tokyo has history, but not presented explicitly through the built environment. I read later in Kaijima’s book, Made for Tokyo, an explanation for this observation, “Where cultural interest is low, interest in practical issues is high.” Make no mistake, there is no lack of spiritual temples from centuries ago, the parks are taken care of to the leaf, and the jazz clubs still rage with saxophone solos, but the konbini perfectly occupies a necessary intermediary space for its practicality and replicability. Spilling onto the narrow streets, little children walk down from their apartments every day to meet the 7-11 sign, this urban landscape and its regular pedestrian flow are necessary for the konbini’s success. On the other hand, the narrow streets depend on the konbini for its validity in a busy and walkable area. Neither can exist on their own. These buildings are symbiotic and respond to the here and now.

To find a more comparable convenience store like that of P&P in Christchurch, I stayed out in the suburb of Shimokitazawa. Surrounded by a thick layer of residential homes, the train station was the heart of the neighborhood. The station served as a food hall, Daiso market, community garden, and leisure space at the same time. It didn’t take long to find a konbini a few steps from the south exit. Glowing just like every other one, the Lawsons storefront was indistinguishable from the Daikanyama neighborhood konbini I visited two stops earlier. Before entering I decided to take a few steps back, and then a spectacular view appeared. The train track dividers raised, allowing the Tokyo traffic to flow once again. First, a flood of bikes, babies strapped to the front wheel, then businessmen rushing to their warm dinner on foot, and finally, a truck slowly tailgating the parade. This time my heart warmed up with the sight of a true multimodal hub, in all its human messiness it was perfect and second nature to the Tokyo resident. I stood at this corner for nearly an hour, in awe of the same image every 5 minutes.

As the after-work rush settled, the fluorescent Lawsons grew brighter and drew me in. With no craving in mind, I felt odd standing in the middle of the konbini. Unlike the dairy with its social qualities, entering a konbini meant knowing exactly what hunger or errand I needed to fulfill. Never mind perusing, most customers were in and out in under a minute, and I was in their way. I decided quickly it would probably be best to find a reason for my visit. I slid my phone to the cashier, “I need a stamp for my postcard home please” typed out in Japanese on Google Translate. Before reading it, I could tell from his reaction this interaction was rare. Much like the store plan, there was a formula for check-out. “Hai” for the to-go bag. “Hai arigato gozaimasu” for the exact change in cash. He pointed at the Japanese language selection and said “Vietnamese please”. I quickly switched the language.

“Ahhh haiiii!”

He typed back the exact instructions for the post office 3 blocks away. His request and warm smile were more than enough help for my stamp search and curiosity. I tried to ask a couple more questions to figure out the owner, but it became clear quickly that these stores operate as franchises with owners often not being in store. We were then interrupted by a rumbling, a man hauling in dozens of crates for the 3rd shipment of the day. Egg sandwiches and onigiris restocked as soon as he entered, extra crates for him to pick up outside of the door. It is normal for the over 7,000 Tokyo konbinis to have a minimum of five deliveries a day. Another testament to the sheer scale of this typology.

The rest of my time in Tokyo was captured through my camera lens. I knew the language barrier wasn’t the problem, rather I figured that understanding these konbinis was less about the story behind the customer and owner, but rather the abundance of them and the flow they enabled in Tokyo residents’ lives. Konbinis are transient and practical to their core, fitting the exact demands of Japanese metropolitan culture.

After Tokyo, the pace of London somehow felt calm for the first time. Perhaps it was centuries-old townhomes or marble plazas that felt ancient compared to Shibuya Crossing. Even the tube grumbled along the tracks, unlike the smooth Japan Rail Express lines. I heard of a famous corner shop in Soho, supplying London fashionistas with all sorts of editorial magazines. I stood outside for a while, observing the morning and lunchtime peaks. Groups of tourists came by to buy a postcard, a young couple walked away with a Japanese street fashion magazine, and the occasional financier stopped by for water. It felt as though the corner shop behaved as a relic of an earlier mercantile time.

As much as I tried, it clicked that comparing central London with Christchurch did not feel particularly useful for this project. Close to the Thames, government buildings, museums, and commercial malls overhaul pedestrian flow so instead, I turned to the residential suburbs of South London. Familiar with Brixton and Peckham from previous visits, I hoped to find more movement or significance in convenience stores at the end of the tube line. Both boroughs are rich in history and now host the vibrant communities of British Latinos, Bengalis, Jamaicans, and Indians. I went to my favorite bookstore in Brixton Village and asked the owner, what do you know about corner shops? My knowledge started and stopped from sporadic mentions in UK grime rap songs. Thankfully she had the key to the rest of my visit. She explained that the corner shops aren’t necessarily the most convenient, but they do host immigrant families that have held together entire ethnic communities. She gave an example of a Bengali family that prepared a special yogurt exclusive to their shop. I asked about my initial observation of the multitude of magazines and newspapers that were fanned out of the tiny shop I saw down the block.

“Some act as relics to a time when British tabloids had much more power in controlling narratives.”

It made sense. The young family wasn’t reaching for the Prince Harry scandal headline, it was the elderly woman on her way back from the grocery store. Although I hoped to find more examples of these immigrant families, London was where I had to admit that the stores didn’t necessarily have as active of a role in a city that seemed to find space for a supermarket every five blocks and pubs for socialization. Instead, I decided to not focus so much on the programming of the corner shop and instead relish the architectural integration of these storefronts in a historical city. I took a couple of days to wander south of the Thames, photographing any mini market I came across. I found my favorite two off-licenses, Mary Russel Off-License on Herne Hill and Tigris Local Shop in Elephant and Castle.

“You have a beautiful store ma’am, the blue you picked is so vibrant!”

The woman, who turned out to be the owner of Mary Russel, beamed out an earnest smile. She quietly thanked me, and I explained to her my project. She gestured for me to look

around and take photos of whatever I wanted. Corner shops, also known as off-licenses, are often wedged into early 20th century tenement buildings and now I had the opportunity to capture the transition between the first and second floor.

A dark stairwell with a little girl’s toys sprinkled all the way through, upstairs was her home. A vertical version of Mr. P’s ‘backroom’. I stood outside and watched as neighbors stepped in and out, noticing the sun-bleached gazebo, and a group of young teenagers ready for their Friday sweet. The same physical wear I observed at Mary Russel, Tigris Local Shop embraced with frail wooden fruit baskets and dusted light bulbs spelling out T-I-G-R-I-S. In the distance a public housing complex, common in South London, outlined the short frame of the shop, a mom in the foreground standing next to her daughter wrangling a lollipop wrapper.

I couldn’t force finding purpose, and perhaps time or integration into the communities would have led to more discovery. It was clear that these shops held a geographical advantage and carried a spark of true London identity from the childhood lollies to the Oyster card top-ups. There is a nostalgia that has potential and makes me excited to uncover what the off license can offer especially to these suburb boroughs.

My final stop went beyond discovering my favorite convenience store. I had heard of a half-Peruvian, half-German cousin my whole life, and now I was on the train to finally meet him. We had talked over WhatsApp for a few days, and it felt as though we had known each other our whole lives. Anasol grew up in the West End, his mom was a graphic designer who tapped into the rich leftist culture of Berlin.

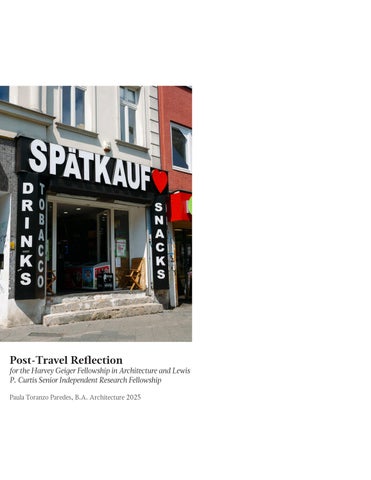

It wasn’t even 10 minutes in Berlin before I asked my cousin why everyone drank their juices from dark glass bottles. At 2 pm on a Wednesday, surely it was a juice or at the very least, in my California mindset, a kombucha. He laughed hard, “Paula, those are beer bottles, time for your first Sterni!” I didn’t expect to enter my first spätkauf -German for late purchase- so soon, but I was pleasantly surprised by how excited my cousin was to help me discover this new typology. On the way my cousin described the concept of a wegbier, beers you drink on the go. Every Berliner learns young that a wegbier is mandatory for any night out, whether a späti crawl or a techno club, the first beer will get you far. Even more traditional was the Sterni, Sternberg Export. Standing at half a liter, no two Sternis taste the same since they are made from leftover beer, at a bargain rate of 1.25 euros my cousin prayed for some luck on a sweeter batch.

“Did you bring Euros?

Up to this point in my travels there was no need to take out cash for a convenience store. I quickly learned that spätkaufs, or späti for short, only take cash and this antiquated, but charming condition hinted towards the aesthetic of the shop we were entering. Greeted by a bottle opener swinging from the door handle, faded photos by the register of a boy in the 90s who is surely 40 with kids by now, and 70s style wood clad walls, I felt like I was again standing in Mr. P’s store. Taking a closer look at the selection my initial association quickly fell apart, the walls were lined with beer fridges, beer crates, the occasional chips selection, and more beer fridges. In a frenzied excitement, I only later noticed the TV facing the sidewalk, blasting a Snoop Dogg music video, and the women speaking Turkish as they checked out the after-school rush. I began to piece together from my cousin’s storytelling and my first observations that the spätkauf nurtured a deep form of socialization for anyone, neighbour or tourist. It wasn’t just a quick hello or a lolly for a kid who completed his homework, the späti sat next to two parks, a bike garage, a daycare, a pizza restaurant, and a U-Bahn station, open late enough to hold together the vibrant community network with a space to socialize.

Originating in East Berlin to meet the needs of a late-night worker’s groceries, the government-run HO grocery store opened spätverkaufstellen, late-night outlets in the 1980s. Responding to a specific community need, these early versions of spätis were symbols of a modern socialist future. As time went on, the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and the späti jumped to

the West, with over 900 spätis across Berlin today. My cousin suggested Kreuzberg as my main research site, both physically and culturally dense, the abundance of spätis run by Turkish immigrants offers a unique lens to the convenience store. My first stop was Kotbusser Tor, endearingly called Kotti to locals, a U-Bahn station connecting the once-isolated Turkish community to the broader city circuit.

Immediately I stepped out to the most lively roundabout I had ever seen. Yellow and white public housing units and fruit vendors spilled onto the sidewalk, I made a Spanish friend on the U-Bahn who had lived in Berlin for a couple of years. He had a couple of hours before his shift in the taqueria nearby and offered to give me a tour of the area. He pointed out the Turkish translation for market written on the main gate into the roundabout. A reflection of the community and the people we were going to meet on our journey soon enough.

“Well, we have a long walk ahead of us, there are at least a dozen späti down whichever road we pick first.”

Some had neon pink signs, they could easily be confused for a nightclub. One had kids’ drawings displayed on the storefront depicting the Spti through their eyes. Each had its version of outdoor seating whether a wobbly Coca-Cola picnic table and skinny bench, or a thick, wood, primary-coloured chair, some had fold-ups, and one even had a leather booth. The interiors were much like the first späti I visited, crates of beer spilling out to the aisles. The Eurocup semi-finals were approaching and no amount of beer was too much. Families stood outside, mom with a beer bottle in hand, kids chugging their juice, it was a normal Wednesday.

After visiting and photographing over a dozen späti, I had to sit down and find a way to classify this typology. The typical spati is defined by product and program, not necessarily aesthetic. Each facilitated what I reflect as a deep connection. You buy a beer and catch up with a childhood friend. You try your first ayran, a Turkish yogurt drink, as a Berlin newcomer. Even the 20-year-old smoking alone sat out connecting to the environment around him, gazing out to the plaza by the späti, no phone screen in sight. The späti functions both as a passageway or the final destination.

The culmination of my späti experience was the Spain versus France Eurocup semifinal. At least a hundred people huddled around the tv, grabbing whatever they could to sit down, beer crates, beach chairs, the park benches, and watched with a Sterni in hand. Children waltzed around in their roller skates, awkward shuffling through the rows of people formed on the roadside. I felt at home. It probably helped that my newfound cousin was sitting next to me, but the accessibility of this social atmosphere felt special.

This project pushed my boundaries in every way imaginable— whether it was starting conversations with strangers, navigating 20-hour travel days, or carrying my growing Osprey through hostels without speaking to anyone for days at a time. Each challenge revealed more about the community networks that exist all around us, often unnoticed, yet eager to share not just opinions, but essential observations—on habits, purchases, and struggles. This reinforced for me that co-development is something I want to pursue, not only through my remaining courses but also throughout my career. I’ve learned that being a designer means taking a step back, actively listening, and respecting the balance between aesthetic vision and community needs. Whether it’s the kooky, neon späti or the modest craftsman extensions, each space had a profound impact because of how deeply they were integrated into the local fabric.

This summer also allowed me to engage with people from all walks of life—entrepreneurs, artists, financiers, and graphic designers—and through these conversations about my project, I noticed a ripple effect. Often, days later, I would receive messages from people saying they had started to notice more around them too. They would share quirky details, like the vintage shop with its playful signage, the hooks at the tops of Copenhagen homes, the strategic placement of bike racks, or how far they had to walk to their nearest grocery store. These small but meaningful details are part of a larger narrative that we are rarely taught to see—one that connects the specific to the broader context. This experience has shown me the importance of questioning more, standing back, and creating visions that can shape a city, a neighbourhood, or even a brand.

I found myself thriving in temporary communities—joining rugby clubs for a week, sketching with groups in South London, and running along the South Island Kiwi coast. These interactions taught me how to embed myself into new environments, even if just for a short time. I’ve become more comfortable being alone, embracing an incredibly rewarding self-starter attitude. From reading more books than I have in the past ten years to adopting new customs like eating alone at restaurants or attending jazz clubs and even theme parks solo, I’ve learned that solitude is not something to fear. It’s allowed me to constantly process and reflect on what I’m experiencing, making me feel more prepared for what’s next.

Looking ahead, I’ve always envisioned London as the next chapter in my growth, and this experience has solidified that. I now have a network of professionals and friendships that make the move not only feasible but exciting. What once felt like a distant dream is now a clear path, and I’m ready to take it with confidence. This summer has not only prepared me for what lies ahead after graduation but has also deepened my appreciation for the importance of community, curiosity, and taking a step back to notice the world in all its complexity.