A Proposal for the African Climate Foundation (ACF)

A Proposal for the African Climate Foundation (ACF)

Princeton School of Public and International Affairs

January 2025

FacultyAdvisor

Dr.DevanneBéda-Geuder

AssociateResearchScholarandLecturerinPublicandInternationalAffairs,Princeton University

Authors

AmyChang|ManueldeFaria|KatieDeal|FranciscoGonzalez

SamHau|FatimaMumtaz|RosemaryNewsome|FerdinandQuayson RiasReed|EleniSmitham|AyushiVig|JingXie

FRONT MATTER

Preface and Acknowledgements

Glossary

Executive Summary

Purpose

I. CONTEXT

Climate Profile

Socioeconomic and Environmental Vulnerabilities

Policy and Institutional Landscape

II. METHODOLOGY

Literature Review

Stakeholder Interviews

Data Analysis and Synthesis

Limitations

III. FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

Current State

and Opportunities

IV. STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACF

1. Strengthen Senegal’s climate change data ecosystem

2. Launch a “Climate Finance Accelerator” program

3. Build capacity for accessing climate finance

4. Support and scale existing governmental efforts to facilitate local access to global climate financing

5. Bridge the implementation gap between finance & sustainability

6. Promote participatory monitoring and evaluation

7. Position the ACF as a voice for elevating regional stakeholders during the energy transition V. CONCLUSION

This report is the final product of a Policy Workshop sponsored by the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA), as part of the Master in Public Affairs (MPA) degree program. It was produced by twelve graduate students advised by Dr. Devanne Béda-Geuder, Associate Research Scholar and Lecturer in Public and International Affairs, Princeton University.

The report’s information and recommendations stem from four months of research and interviews with government agencies, civil society organizations, academics, and international institutions. A full list of stakeholders interviewed is Included at the end of the report. The group conducted in-person and virtual interviews in both Dakar, Senegal and Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

Throughout the report, we make reference to some of those we interviewed by name, indirectly by title, or as a workshop interview. This was done at the request of those we interviewed to allow them to speak freely and for us to be able to use the information they provided to us in this report. The report does not necessarily reflect the views of any individual interviewee or respondent, Princeton University, our client the African Climate Foundation, or any person or their affiliated organizations who collaborated with the workshop.

We are deeply grateful to the many people who supported us in our policy workshop. Thank you to the government officials, researchers, and civil society leaders who so generously shared their expertise with us. Thank you also to Dr. Devanne Béda-Geuder, Dean Amaney Jamal, Senior Associate Dean Paul Lipton, Associate Dean Karen McGuinness, Associate Director Tam Le Rovitto, Finance and Operations Manager Shannon Presha, and the rest of the SPIA team who made this learning experience possible.

A special thank you to the African Climate Foundation and Lamine Cissé for hosting us and providing invaluable guidance throughout our journey. We have greatly appreciated the opportunity to learn more about Senegal and its dynamic context of climate adaptation and mitigation. We look forward to carrying these insights with us as we move forward.

We are grateful to the stakeholders who took the time to speak with our Policy Workshop. Their comments were invaluable and helped to inform the perspectives and recommendations presented in this report. The content of the report does not necessarily reflect their views or the views of their affiliated organizations. The interviews are listed below in alphabetical order by organization.

African Development Bank (AfDB) Agence de Développement Municipal (ADM) Centre de Suivi Ecologique (CSE)

City of Dakar

Enda Energie Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ)

Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI) Heinrich Böll Stiftung

La Banque Agricole

Ministry of Environment

Prime Minister’s Office

Université Cheikh Anta Diop (UCAD)

World Bank

Definitions

Blendedfinance:Useofcatalyticcapitalfrom publicorphilanthropicsourcestoincreaseprivate sectorinvestmentinsustainabledevelopment.

Climateadaptation: Processofadjustingtoand preparingforthecurrentandprojectedeffectsof climatechange.

Climatemitigation:Actionstakentoreduceor preventthereleaseofgreenhousegasesintothe atmosphere,ortoincreasecarbonsinksthat removegreenhousegases.

Climatefinance:Local,nationalortransnational financing—drawnfrompublic,privateand alternativesourcesoffinancing—thatseeksto supportmitigationandadaptationactionsthatwill addressclimatechange.

Senegal2050:NationalAgendaforTransformation (orSenegalVision2050),introducedbyPresident BassirouDiomayeFaye’sadministration,outlininga strategicroadmaptotransformSenegalintoa sovereign,prosperous,andjustnationby2050. Targetedreformsandregionaldevelopment initiativesinclude:economic competitiveness, territorialimbalances,sustainability,and social equity.

UrbanMasterPlanoftheCityofDakar2035: Acomprehensivedevelopmentplantoguide Dakar’surbangrowthanddevelopmentuntil2035, focusingon:creatingamulti-polarurbanstructure withnewdevelopmentpoleslikeDiamniadioand DagaKholpa,improvingpublictransportation systems,andprioritizingenvironmental sustainabilitybymanagingflood-proneareasand preservinggreenspaces;essentiallyaimingto createamoreefficient,inclusive,and environmentallyconsciouscityby2035.

ACCF:AfricaClimateChangeFund

ACF:TheAfricanClimateFoundation

ADM:AgencedeDéveloppementMunicipal (MunicipalDevelopmentAgency)

AFD:AgenceFrançaisedeDéveloppement(French DevelopmentAgency)

AfDB:AfricanDevelopmentBank

ANSD:AgenceNationaledelaStatistiqueetdela Démographie(NationalAgencyforStatisticsand Demography)

APRI:AfricaPolicyResearchInstitute

CAR:Communautéd'AgglomérationdeRufisque (RufisqueAgglomerationCommunity)

CCDE:ClimateChangeDataEcosystem

CGQA:CentredeGestiondelaQualitédel'Air (CenterfortheControlofAirQualityofSenegal)

CIRAD:CentredeCoopérationInternationalen RecherchéAgronomiquepourleDéveloppement (InternationalCooperationCenterforAgricultural ResearchandDevelopment)

COMNACC:LeComitéNationalsurles ChangementsClimatiques(NationalCommitteeon ClimateChange)

COPERES:ConseilPatronaldesÉnergies RenewablesduSénégal(BusinessCouncilof RenewableEnergiesofSenegal)

CPI:ClimatePolicyInitiative

CRADESC:CentredeRechercheetd'Actionsurles DroitsÉconomiquesSociauxetCulturels(Centre forResearchandActiononEconomic,Socialand CulturalRights)

CRSE:CommissiondeRégulationduSecteurde l'Electricité(ElectricitySectorRegulation Commission)

CSE:CentredeSuiviEcologique(Ecological MonitoringCentre)

DHS:DemographicandHealthSurvey

EO4SD:EarthObservationforSustainable Development

ESG:Environmental,social,andgovernance

EV:ElectricVehicle

FCFA:FrancdelaCommunautéFinancièreAfricaine (FrancoftheFinancialCommunityofAfrica)

FONSIS:FondsSouveraind'Investissements Stratégiques(SovereignFundforStrategic Investments)

GCF:GreenClimateFund

GDP:GrossDomesticProduct

GEF:GlobalEnvironmentFacility

GGGI:GlobalGreenGrowthInstitute

GIZ:DeutscheGesellschaftfürInternationale Zusammenarbeit(GermanAgencyforInternational Cooperation)

IFC:InternationalFinanceCorporation

IRD:Institutderecherchepourledéveloppement (ResearchInstituteforDevelopment)

ISRA:InstitutSénégalaisdeRechercheAgricole (SenegaleseInstituteofAgriculturalResearch)

JETP:JustEnergyTransitionPartnerships

LBA:LaBanqueAgricole

MEDDTE:Ministèredel'Environnement,du DéveloppementDurableetdelaTransition Écologique(MinistryofEnvironmentandSustainable Development)

MRV:MonitoringReportingandVerification

MSSAT:MeghalayaSocietyforSocialAuditand Transparency

MTGDMT:MinistèredelaGouvernanceTerritoriale, duDéveloppementetdel’Aménagementdu Territoire(MinistryofTerritorialGovernance, Development,andSpatialPlanning)

NAP:NationalAdaptationPlan

NDC:NationallyDeterminedContribution

PARIS21:PartnershipinStatisticsforDevelopment inthe21stCentury

PASTEF:PatriotesafricainsduSénégalpourle travail,l'éthiqueetlafraternité(TheAfricanPatriots ofSenegalforWork,EthicsandFraternity)

PM2.5:ParticulateMatter2.5

PM10:ParticulateMatter10

PPA:PowerPurchaseAgreement

PROGEP:ProjetdeGestiondesEauxPluvialeset d’adaptationauchangementclimatique (StormwaterManagementandClimateChange AdaptationProject)

PSE:PlanSénégalEmergent(PlanforanEmerging Senegal)

QGIS:QuantumGeographicInformationSystem

Senelec:SociétéNationaled'ÉlectricitéduSénégal (Senegal’sNationalElectricityAgency)

TER:TrainExpressRégional(RegionalExpress Train)

UCAD:UniversitéCheikhAntaDiopdeDakar

UN:UnitedNations

UNCDF:UnitedNationsCapitalDevelopmentFund

UNFCCC:UnitedNationsFrameworkConventionon ClimateChange

SDI:SlumDwellersInitiative

SFI:SenegaleseFederationofInhabitants

WASCAL:WestAfricanScienceServiceCentreon ClimateChangeandAdaptedLandUse

WATHI:WestAfricaThinkTank

WB:WorldBank

WHO:WorldHealthOrganization

Across Sub-Saharan Africa, the impacts of climate change—ranging from coastal erosion to flooding, drought, and heatwaves—are becoming increasingly acute. Senegal is no exception, with its capital city, Dakar, facing disproportionate risks as a rapidly urbanizing coastal hub. Dakar’s unique position as the economic and cultural center of the country amplifies the urgency to address these challenges, particularly as vulnerable communities, including those in informal settlements, are disproportionately affected. The intersection of urban poverty, social inequality, and climate vulnerability underscores the need for coordinated, inclusive, and sustainable climate adaptation and mitigation strategies.

This report provides an in-depth analysis of the challenges and opportunities Dakar faces in implementing its climate agenda. It highlights the need to address critical gaps in data availability, institutional capacity, and access to climate finance while fostering collaboration between local, national, and international stakeholders. Our research aims to support the African Climate Foundation (ACF), the client for this policy workshop, in advancing Dakar’s climate resilience through targeted interventions that prioritize equity, transparency, and sustainability. Our findings are informed by stakeholder interviews, geospatial analysis, and a review of existing climate policies and frameworks.

This approach enabled us to offer the following recommendations for ACF:

1.FacilitatestrengtheningofSenegal’s ClimateChangeDataEcosystem: FacilitatetheClimateChangeDataEcosystem efforttoimproveaccessibility,identifygaps,and enableinnovativeapproachestounderstanding climaterisks.

2.LaunchaClimateFinanceAccelerator: Buildlocalcapacityforgrantwritingandproject development,whileleveragingAItoolstosimplify applicationprocessesandenhancefunding successrates.

3.FosterParticipatoryGovernance: Implementaframeworkforsocialauditsand communityengagementtoensurevulnerable populationsareempoweredandincludedin decision-making.

4.StrengthenLocal-NationalCollaboration: Partnerwithnationalentitiestoimproveaccessto climatefinanceandscalesuccessfulpilotprograms invulnerableregions.

5.ElevateDakar’sGlobalLeadership: PositionDakarasamodelcityforurbanclimate resiliencethroughstrategicadvocacy, partnerships,andshowcasinginnovativepractices onaninternationalstage.

6.PromoteParticipatoryMonitoringand Evaluation: Promotesocialauditsforitsfundedprojectsand programsinDakar.

7.PositiontheACFasaVoiceforElevating RegionalStakeholdersDuringtheEnergy Transition: AdvocateforregionalstakeholdersinAfrica’s energytransition,ensuringthatlocalperspectives, needs,andinnovationsareprioritizedinglobal climateconversations.

With a focus on inclusive, data-driven, and participatory approaches, the ACF can emerge as a global leader in climate adaptation and mitigation, ensuring a sustainable future for Dakar’s residents. This report provides a roadmap for action, empowering the ACF to champion these efforts and drive impactful change.

The African Climate Foundation (ACF) is a leading philanthropic organization dedicated to fostering climate resilience and advancing equitable development across the African continent. Guided by a mission to catalyze systemic change, the ACF works to bridge gaps between climate policy, finance, and implementation, with a focus on empowering communities most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. The ACF currently works in “pivot countries” which involve incountry work and act as entry points to expanding sub-regional work, including South Africa, Namibia, Nigeria, and Senegal. By leveraging strategic partnerships with government, private sector, philanthropic organizations, and civil society, the ACF seeks to bolster the climate agenda in Senegal and beyond.

The purpose of this workshop is to support the ACF in enhancing its work to implement its climate adaptation agenda. As a uniquely positioned institutional actor, the ACF offers distinct value by serving as an independent, agile convener of diverse stakeholders, enabling crosssectoral collaboration that is often challenging for government or private entities alone. The ACF’s ability to combine policy expertise with strategic funding, with an emphasis on equity and inclusion, positions the organization as a critical driver of transformative change in Senegal’s climate landscape.

Ourresearchquestionsfortheworkshopwere: Inthecurrentcontextofclimatepolicyand financeinSenegal,howdoesthecurrent landscapeofstakeholders,priorities,resources, andneedsshapethekeyopportunitiesfor impact?HowcantheACFbestsupportthose opportunities? 1.

2.

Whatarethecriticalalignmentpointsandgaps betweenclimatefinanceflows,policypriorities, andimplementationcapacityacrossSenegal's climateactionlandscape,andhowcanthese informtheACF'sstrategicinterventions?

Toaddressthesequestions,weidentifiedthree strategicobjectivesforourworkshop,whichform thebasisofthisreport:

AnalyzetheimplicationsofSenegal’srecently releasedSenegal2050forclimatemitigationand adaptationinDakar,particularlyinthecontextof pre-existinglocal,national,andinternational policiesandagreements,withafocuson vulnerablepopulations(women,youth,and informalsettlements).

3.

2. Developstrategicrecommendationstosupport theACFasachampionoftheclimatepolicyand financeagendainSenegal.

Identifythechallengesandopportunitiesin climaterisksandfinance,focusingonthegapsin bothfieldsthatwillproverelevanttotheACF executingitsmissioninSenegal.

Thisreportbuildsoninsightsgatheredthrough stakeholderengagement,policyanalysis,and geospatialassessments,offeringactionable pathwaysfortheACFtostrengthenitsimpactin Senegal.

WesoughttocenterourresearchonwhatwelearnedfromgovernmentandcivilsocietystakeholdersinDakar, prioritizingactionablerecommendationsthataresensitivetolocalcontextwhileincorporatingglobal perspectives.Nevertheless,wewishtoacknowledgeourpositionsandlimitationsasgraduatestudents receivingpolicytraininginaneliteWesterninstitution.Thistrainingoftenprivilegescertainparadigmsof development,suchastechnocraticsolutionsandassumptionsofobjectivityandneutrality,whichmaynotfully alignwithlocalrealities.ManyofusarefromtheGlobalSouth,butmosthavenopriorexperienceinSenegal. Whilewehavemadeeffortstoincludediversestakeholderviews–throughinterviews,literaturereviews,and othermeans–weacknowledgethatnotallvoicesarerepresented.Weofferthisreportnotasanauthoritative assessment,butratherasastartingpointfordialogueandcollaborationtowardsclimateadaptationand mitigationinDakar.

Senegal, situated along the Atlantic coast and within the Sahel and larger West African region, finds itself at the crossroads of climate change, urban transformation, and economic development. As a country with a rapidly growing population and a high reliance on climatesensitive industries such as agriculture, fishing, and tourism, Senegal is highly vulnerable to the impacts of a changing climate. Rising global temperatures, shifting weather patterns, and intensifying natural hazards are exacerbating pre-existing social and economic inequalities.

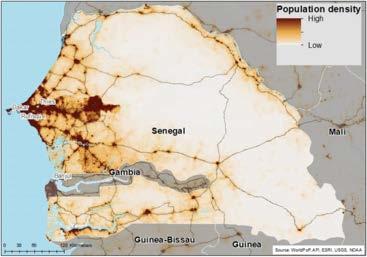

Rapid urban transformation in Senegal amplifies these risks. Over 49% of the country’s population now resides in urban areas, a figure projected to exceed 60% by 2035. However, this urbanization is starkly dominated by the Dakar metropolitan region, which, despite occupying only 0.3% of the national territory, houses 25% of the population (see Figure 1) and generates over half of the country’s GDP. This economic and demographic concentration also leaves secondary cities underdeveloped, with limited economic and infrastructural development.

The capital of Senegal, Dakar, faces unique urban and climate challenges. As the westernmost point of mainland Africa, situated on the Cap-Vert peninsula, the city is particularly at risk of coastal erosion due to its geographic position, coastline dynamics, and low-lying area. As the largest city of Senegal, Dakar city spreads across almost 80 square kilometers (~31 square miles). The department of Dakar, one of four administrative districts (Dakar, Guédiawaye, Pikine, and Rufisque) within the Dakar metropolitan region, has a population of more than 1 million, and the broader Dakar metropolitan area has a population of approximately 4 million.

Dakar’s historical trajectory under colonialism and beyond highlight the intersection of colonial urban planning and the ongoing challenges of urbanization combined with climate challenges. Colonized by the French in 1857, Dakar replaced the island city of Saint-Louis to the north as the capital of French West Africa in 1902. Initially, colonizers promoted the assimilation of the local population, and city plans incorporated European features. However, by the early 20th century,

Source: ISS African Futures (Link)

Source: Data from the Earth Observation for Sustainable Development (EO4SD) Urban Project Map, created by authors

assimilation efforts faltered and the French shifted to a policy of segregation. This policy was formalized in 1914 with the creation of the Médina, a “native quarter” to separate the African population. After World War II, rapid urban growth, fueled by migration and housing shortages, led to an increase in informal settlements. Today’s urban structure and infrastructure development stem from this colonial history, which created patterns of exclusion that persist.

Given this unique combination of factors, Dakar is the primary focus of this Policy Workshop and report.

Among Senegal’s pressing climate challenges, Dakar’s vulnerability stands out due to its geographical position, population density, and socioeconomic disparities. The city grapples with three interconnected natural hazards that threaten its urban development and resilience: coastal erosion and sea level rise, urban flooding, and extreme urban heat. These hazards not only disrupt daily life but also jeopardize critical infrastructure, health, and livelihoods. Understanding the drivers and scale of these vulnerabilities is essential to developing targeted solutions that can mitigate risks, protect communities, and support sustainable urban development.

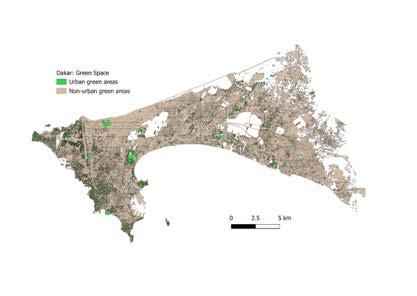

Urbanheatpresentsagrowingchallengefor Dakar,drivenbyrapidurbanization,limitedgreen spaces(seeFigure2),andtheuseofheatretainingconstructionmaterials.Risein temperatureacrossSenegalisexacerbatingthe urbanheatislandeffectinDakar,whichoccurs whenametropolitanareaismuchwarmerthan thesurroundingruralareas. Vulnerable communitiesaredisproportionatelyaffected,as theyoftenlackaccesstocoolinginfrastructureor resourcestoadapt.Inadequateurbanplanning andlimitedinvestmentingreeninfrastructure continuetoworsentheserisks,threateningpublic healthandproductivityinthecity.TheWorld HealthOrganization(WHO)hasemphasizedthat heatstresscanworsenconditionssuchas cardiovasculardisease,heatstroke,diabetes, mentalhealthdisorders,andasthma,whilealso heighteningtheriskofaccidentsandthespread ofcertaininfectiousdiseases.

Coastalerosionandsealevelrise Senegalhasexperiencedsevereimpactsof coastalerosion,withitscoastlineretreatingatan averageof2.2metersannuallybetween1954and 2002,acceleratingto3metersperyearfrom 2014to2018.Thiserosionhasdevastated housing,tourism,andfishinginfrastructure,while causingbeachloss,agriculturallanddegradation,

and increased salinity in groundwater and estuarine areas, which threatens mangroves and fisheries. Coastal erosion is projected to cause significant economic losses for the district municipalities along Dakar's coastline, estimated at 38.5 billion FCFA by 2030 and 57.8 billion FCFA by 2040. Without proactive adaptation measures, coastal erosion is poised to become one of the most severe climate threats to the Dakar region.

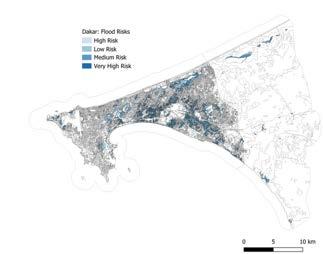

Flooding poses a significant and recurring challenge for Senegal, particularly coastal cities like Saint-Louis and Dakar. In 2018, the World Bank launched the Saint-Louis Emergency Recovery and Resilience Project, relocating nearly 10,000 people living within the 20-meter zone from the coastline considered at very high-risk of flooding. Dakar, driven by intense seasonal rainfall, limited urban planning, and inadequate drainage systems (see Figure 3). Since 2005, repeated flooding events have displaced thousands of residents in Dakar, particularly affecting low-income neighborhoods such as Pikine and Guédiawaye, to the east of the city center. A 2021 study estimated that nearly 40% of the population in Dakar and its peri-urban areas live in flood-prone areas, where unplanned urban expansion has exacerbated the issue. For instance, Grand Yoff is one of the areas most susceptible to flooding. Despite having a natural marshland where rainwater runoff from the surrounding watershed is collected, the marshland area was degraded by rapid urbanization, land use change, poor upstream management, and unmanaged wastewater discharge. This degradation means that the retention basin overflows during heavy rains and floods the surrounding catchment area with contaminated water that impacts health, the local economy, livelihood, and environment. The economic impacts are staggering: a 2021 report by the C40 Cities Finance Facility estimates that floods along Senegal's coast in 2017 cost the national economy approximately $230 million, equivalent to about 1.4% of the country's GDP. Moreover, floodwaters often remain stagnant for extended periods due to poor drainage, posing significant public health risks by facilitating the spread of waterborne

Source: World Bank Group (Link)

diseases such as cholera and malaria. In addition to economic and health impacts, flooding intensifies existing social inequalities in Dakar. Vulnerable communities in informal settlements are disproportionately affected, with limited access to resilient infrastructure and emergency response systems. For example, during the severe floods of 2009, approximately 360,000 people were directly affected, with the peri-urban areas of Pikine and Guédiawaye being the most impacted due to unfavorable existing condition in the area. The expansion of informal settlements into these high-risk areas reflects a combination of inadequate urban planning, lack of enforcement of land use regulations, and limited access to affordable, safe housing. These factors, rather than topographical realities alone, exacerbate the vulnerability of marginalized populations to the impacts of flooding. Climate projections indicate that extreme rainfall events in Dakar are likely to increase in frequency and intensity, further exacerbating the city’s vulnerability. The inadequate capacity of drainage systems, which is insufficient to handle the city's rainfall during heavy storms, highlights the urgent need for improvements in urban planning and management. Without targeted interventions, flooding will continue to undermine Dakar’s urban resilience, development, and public health.

Ontheoppositeendofthespectrum,Dakaralso experiencesrepeateddroughts,whichhas resultedinpooraccesstowaterresources.Urban areasandlow-incomecommunitiesexperience frequentwatershortagesandlimitedaccessto cleanwater.Insufficientwastemanagementand pollutionalsocontributetothedegradationof watersupply,reducingavailabilityandcreating healthrisksforlow-incomecommunities.For agriculture,watershortagesduringdroughts resultindiminishingproductivityandlossof crops,inmostcasesseverelyaffectingthe livelihoodsofcommunitiesdependenton agriculturalyields.

Dakarfacesaseriesofclimateadaptation challengesthatreflectitspositionasarapidly urbanizingcoastalcity.Increasinglysevere climateimpactsareexacerbatedbyinadequate urbandevelopment,infrastructure,and governancegaps.Thesechallengesdemanda deeperunderstandingofadaptationacross diversesectors.Whileclimatechangetouches nearlyeverysectorofurbanlife,threeareof primaryimportancebasedontheircriticalrolein supportingDakar’sresilienceanddevelopment, eachrepresentinganexuswhereclimateimpacts intersectwitheconomicandsocialvulnerabilities: agriculture,infrastructure,andhealth.

Agriculture

Climatechangeisoneofthegreatestthreatsto agricultureinSenegal,resultinginreduced productivityandseverelyaffectingthelivelihoods ofruralcommunities.Agricultureisaffectedby issuessuchasvulnerabilityoftraditional agriculturalsystems,limitedarableland,water andenergyscarcity,andurbanization.Traditional systemsaresusceptibletoclimatevariability, whichcontinuestoincreaseinrecentyearsas seenthroughunpredictablerainfallpatterns, temperatureshifts,andextremeweatherevents. These,combinedwithdroughtsandlackofwater andenergyforirrigationandotherprocesses, resultindecreasedproductivity.Urbansprawl alsocontinuestotakeoverperi-urbanareas, resultingindecreasingavailablelandfor

agriculture. These issues create challenges for local communities that rely on their agricultural production and have the potential of resulting in significant food shortages, highlighting the pressing need for adaptation efforts.

Gaps in the agricultural sector include urbanization of peri-urban areas, challenges in water access, and increased use of technological innovations. Even though urban sprawl is seen as a threat to agricultural production, particularly the availability of arable land, there is only a limited focus on the strategies that need to be implemented to preserve agricultural spaces. Similarly, even though new irrigation systems improve water usage, future shortages of water resources still need to be addressed to ensure that agricultural production is resilient to climate change. Lastly, small pilot projects to transition to solar water pumps and improved seeds need to make use of technologies for sustainable agriculture and be implemented at scale across the country and a variety of agricultural producers.

Dakar’s urban infrastructure plays a dual role in both mitigating and exacerbating climate risks. Gray infrastructure, such as drainage systems, is essential for managing flooding, while green infrastructure, such as urban vegetation, can help mitigate heat risks. However, Dakar's rapid urbanization has outpaced its infrastructure development, leaving critical gaps in access for the population as well as climate resilience.

18 19

Many neighborhoods lack adequate drainage systems, leading to frequent and severe flooding during the rainy season. Unplanned urban growth, coupled with outdated planning frameworks, exacerbates these vulnerabilities. Further, climate change also poses significant challenges to Dakar's transportation infrastructure. Extreme weather events such as flooding, sea level rise and urban heat can cause extensive structural damages to transport infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, and drainage systems, disrupting mobility and economic activities. The economic implications of these disruptions are significant, as Dakar is a key economic hub in Senegal. Without climate-resilient infrastructure, the city

faces escalating costs due to infrastructure damage, reduced productivity, and longer recovery times from extreme weather events. Interacting with these challenges is the city’s air quality, which has reached hazardous levels in Dakar according to the WHO guidelines. Airborne particulate matter (PM10) frequently exceeds recommended limits, sometimes by as much as sevenfold. Emissions from second-hand vehicles with outdated and inefficient engines is a major contributor to Dakar's worsening air pollution, as well as natural phenomena like the Harmattan winds, which carry fine desert dust particles into the urban atmosphere. Without proactive measures, Dakar faces a growing risk of worsening public health crises and escalating economic losses tied to its infrastructure vulnerabilities.

Human health is deeply intertwined with both the built and natural environments in Dakar. Not only does flooding ruin homes and cause displacement, but stagnant water resulting from flooding is also a breeding ground for water borne diseases like malaria, coughing, and diarrhea in children. Risks of vector-borne diseases like malaria are associated with rising temperatures and rainfall variability. Furthermore, air pollution, toxic smoke from improper waste disposal, and general rapid urbanization and density increase risks for respiratory illnesses like influenza, bronchitis, and tuberculosis. Hospitals in Dakar have reported a notable increase in admissions for respiratory illnesses such as asthma, bronchitis, and other chronic lung conditions.

Senegal struggles with an underfunded health system, a shortage of healthcare professionals, and overcrowded health facilities, which result in disparities in both accessing care and in health outcomes between regions, income levels, living environments, and education levels. Climate impacts reinforce existing health disparities and exacerbate vulnerabilities.

MostofSenegal'surbandevelopmentand economicactivityisconcentratedalongthe coast,withDakaratitscore—apatternshapedby thecountry’sgeographicfeatures,colonial presenceandresultantinvestmentsin infrastructure,housingandindustryaswellas currenteconomicdynamics.Thisconcentration hasledtosignificantpopulationclusteringin coastalzones,heighteningexposureto environmentalvulnerabilitiessuchasflooding andcoastalerosion,whichareworseningdueto climatechange. Atthesametime,secondary citiesinSenegalstruggletoattractinvestments andgenerateemploymentopportunities,limiting theircapacitytoeasetheburdenonDakar.

UnderpinningthiscontextisSenegal's macroeconomicenvironment,particularlythe risingpublicdebtlevels.Asthegovernment borrowstofinanceinfrastructureprojectsand socialprograms,thedebt-to-GDPratiohas increased,raisingconcernsaboutfiscal sustainability.Risingpublicdebtreduces Senegal’scapacitytodevelopinnovative instruments.Additionally,theburdenofdebt servicingcanlimitthegovernment’sabilityto investininfrastructuredevelopmentandcapacity building,furtherdiminishingtheattractivenessof theinvestmentlandscape.

Relatedly,theeconomy'svulnerabilitytoexternal shocksexacerbatesthesechallenges. Fluctuationsincommodityprices,whichheavily influenceSenegal'sexportrevenues,cancreate instabilityandunpredictabilityforinvestors. Coupledwithhighinflationrates,currency depreciation,andregulatorycomplexities,these factorscansignificantlyimpactbusiness operationsandprofitmarginsoratleastdeter prospectiveinvestors.

Socialvulnerabilityisacriticalfactorshapingthe adaptivecapacityofDakar'spopulationtoclimatehazards.Marginalizedgroups,particularly

those residing in informal settlements, face disproportionate risks due to their socioeconomic status and geographic location. These communities are often situated in flood-prone or precarious areas, where access to basic infrastructure and public services is minimal. Residents are excluded from formal urban planning processes, leaving them exposed to significant environmental hazards.

Moreover, insecure land tenure exacerbates vulnerability. Without legal rights to their homes, residents face potential eviction, which discourages investments in resilient housing or infrastructure. Systemic governance inequities further marginalize these populations, limiting their access to resources and adaptive support. The intersection of poverty, exclusion, and inadequate planning creates a cycle of vulnerability that requires urgent attention.

Because informal settlements are usually located in precarious locations, such as beside rivers, residents are vulnerable to floods. Meanwhile, many rivers next to informal settlements become dump grounds for trash and waste, attracting malariacarrying mosquitos and other blood-borne diseases. When climate-induced heavy rainfall occurs, residents lose their poorly built homes and are vulnerable to waterborne diseases. Furthermore, the high density of informal

settlements increases heat because of a lack of open space. Informal settlements, often constructed with heat-retaining materials like concrete and cinder blocks, are particularly vulnerable to rising maintenance of drainage systems compound the temperatures. Climate change has intensified these challenges by increasing the frequency and severity of heatwaves, disproportionately impacting residents in these densely populated areas. Additionally, these settlements are highly susceptible to flooding due to their location in low-lying or flood-prone areas. The lack of adequate drainage infrastructure exacerbates the risks, leaving residents exposed to stagnant water, property damage, and health hazards.

Rapid urbanization has intensified vulnerabilities of informal settlements, as unplanned expansions push settlements into high-risk zones. Weak enforcement of zoning regulations and inadequate problem. While initiatives like Stormwater Management and Climate Change Adaptation Project (PROGEP) have reclaimed 900 hectares of flood-prone land, fragmented coordination among stakeholders and the limited inclusion of informal settlements in flood management plans undermine sustainable resilience. Without cohesive urban planning and resource allocation, informal settlements remain disproportionately exposed to climate hazards.

NationalandurbanframeworksinSenegal(see Figure4)haverecognizedtheneedtobalance economicdevelopmentandclimateaction. AlignedwithSenegal’sdevelopmentframework underthePlanforanEmergingSenegal(PSE), thenationaimstoachieveeconomic developmentby2035throughatransitiontoa moresustainableanddiversifiedenergymix. Renewableenergyinvestmentsarecentraltothis strategy,withsolarandwindprojectsexpanding acrossruralareasandlarge-scalefacilities enhancingnationalelectricityproduction.These initiativesaimtopositionSenegalforeconomic growthwhileguidingittowardapathof sustainabledevelopment.

Senegalfindsitselfatacriticaljunctureinits developmenttrajectory,grapplingwiththedual challengesofeconomicgrowthand transformationandclimateresilience,while navigatingacomplexlandscapeofgovernance reformsandpoliticaltransition.Asthecountry workstoharmonizeitsdevelopmentgoalswith climateimperatives,itsapproachtoclimate financehasemergedasakeydeterminantofits future.

Thenation'searlyadoptionofclimateaction withintheAfricancontext,markedbyits1994 ratificationoftheUnitedNationsFramework ConventiononClimateChange(UNFCCC)and subsequentdevelopmentofitsfirstNational AdaptationProgrammeofActionin2006, establishedafoundationforprogressiveclimate policy.However,thisproactivestancehas consistentlyfacedtensionwithSenegal's pressingeconomicdevelopmentneedsand heightenedvulnerabilitytoclimateimpacts.

Thenation'sdevelopmentcontextpresentsa strikingparadox:whileachievingconsistent economicgrowth,averaging6%annually between2014and2018,Senegalcontinuesto strugglewithpersistentpoverty,withoverathird ofitspopulationlivingbelowthenationalpoverty lineasof2023. Additionally,thegeneral

government gross debt in Senegal is 84.3 percent of GDP, highlighting its high reliance on borrowing to finance its fiscal expenditures. The Senegalese economy struggles with several vulnerabilities such as low productivity, limited human capital, high levels of informality, and youth emigration. This economic precarity is concerning given the country's significant exposure to climate risks, especially in its densely populated and economically vital coastal regions.

The challenge of addressing these vulnerabilities has been further complicated by Senegal's evolving governance structure, which has undergone several significant phases of decentralization reform since independence. The evolution of Senegal's governance framework from a highly centralized system began with the 1972 reforms, which introduced limited administrative autonomy for rural communities while maintaining strict fiscal control at the national level. This initial step toward decentralization was followed by the more comprehensive 1996 Decentralization Law, which significantly expanded the powers of municipalities and regions, particularly in areas of urban management and infrastructure development. The 2013 Act III of Decentralization marked the most ambitious reform yet, emphasizing fiscal decentralization and the territorialization of public policy, though implementation challenges continue to constrain its effectiveness.

The transfer of climate adaptation responsibilities to local governments, especially in vulnerable cities like Dakar and Saint-Louis, illustrates both the potential and limitations of decentralized climate governance. In Dakar's flood-prone district of Grand Yoff, local governments have implemented stormwater retention basins. Yet, these efforts face challenges from rapid urbanization, unregulated construction, and inadequate waste management infrastructure. Similar governance challenges manifest in SaintLouis, where local authorities struggle to address coastal erosion and sea-level rise despite their mandate for climate resilience measures.

Senegal ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), becoming one of the early adopters of climate action In the African context.

The country developed its first National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA), identifying priority actions for climate resilience and funding strategies.

Act III of Decentralization was launched to empower local governments and facilitate local-level implementation of climate finance.

National government launches comprehensive national strategy to transform Senegal into an emerging economy by 2035. The framework integrates climate adaptation and emphasizes green investments.

Sangomar and Grande Tortue Ahmeyim (GTA) field discoveries presented new economic opportunities but added complexity to climate commitments.

Began as part of the broader PSE strategy, aiming to modernize infrastructure, address urban climate risks like sea-level rise and flooding, and enhance transportation and housing to meet the demands of rapid urbanization.

Senegal secured the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), a $2.7 billion international partnership to transition to renewable energy and reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

Senegal 2050 builds on the PSE, emphasizing sustainable development, green energy, and local autonomy. It promotes solar and wind power for energy independence and decentralizes governance into eight territorial poles for tailored regional growth. The plan seeks 40% private climate financing while enhancing multilateral and domestic partnerships to address climate challenges.

Thecentralizationofclimatefinance managementbymultilateralentitiesandnational governmentscreatesrisksofinequitable resourceallocation,potentiallybypassingthe mostvulnerablecommunities.While decentralizationhasopenednewpathwaysfor localgovernmentstoaccessinternationalfunding andtechnicalsupport,includinginitiativeslike theJustEnergyTransitionPartnership(JETP), effectiveimplementationremainsconstrainedby financial,institutional,andtechnicallimitationsat thelocallevel.

AsSenegalmovesforwardunderthenew presidencyofBassirouDiomayeFaye—whose partyTheAfricanPatriotsofSenegalforWork, EthicsandFraternity(PASTEF)wonanabsolute majorityinParliamentduringNovember2024 elections—thecountrymustnavigatethecomplex interplaybetweeneconomicdevelopment, climateaction,andfiscalsustainabilitywhile addressingpersistentchallengesingovernance reform.

Duringourin-countryresearch,President DiomayelaunchedSenegal2050,anambitious frameworkthatbuildsuponandextendsthePSE whileemphasizinggreaterlocalautonomyin climateinvestmentdecisions.Theinitiative placesstrongemphasisonsustainable developmentandthetransitiontogreenenergy, aimingtoincreasetheshareofsolarandwind powerwhilereachingthecountry’sultimategoal ofenergyindependence.Theplanalsooutlinesa seriesofstrategicreformstostrengthen decentralizationefforts,concentrating administrativeservicesaroundeightterritorial “poles”promotinginclusivegrowthandtailored developmentstrategiesaccordingtoregion.To thatend,climatefinancemustaddressthe economicandclimatechallengesfacedbya particularregion,whilepromotingastronger enablingenvironmentforinvestmentacrossthe country.

Senegal’senergymixisshiftingtowards renewablesthroughbothnationaland internationalprograms.Akeycomponentof Senegal’srenewableenergyagendaistherecent JETP,acollaborativeefforttosupportthe country’sshiftfromfossilfuelstoarenewable energy-driveneconomy.Launchedaspartof globalclimatecommitments,theJETPaimsto increaserenewablesto40%ofinstalledcapacity by2030whilereducingthecarbonintensityof electricitygeneration.Thispartnershipinvolves financialandtechnicalassistancefrom internationalpartners,blendingconcessional loans,grants,andprivatesectorinvestment. AlongwithSenegal’sNationallyDetermined Contribution(NDC),theJETPaimstoreduce carbonemissionsandenablerenewableenergy transitions.

TheJETPnotonlyunderscoresSenegal’s ambitiontoaccelerateitscleanenergytransition butalsoservesasamodelforleveragingglobal partnershipstoachievesustainabledevelopment goals.However,challengesremain,includingthe needtoensureaninclusivetransitionthat prioritizesenergyaccessforall,addressesdisparitiesinruralelectrification,andminimizes socialdisruptionincommunitiesdependenton fossilfuelindustries.Additionally,long-term plansbeyond2030remainuncertain,raising questionsabouthowthecountrywillsustain momentumtowardanet-zerofuture.By capitalizingonJETPfundingandfosteringpublicprivatecollaborations,Senegalhasthepotential todrivesignificantinvestmentinrenewables, establishitselfasaregionalleaderinclean energy,andenhanceitsresilienceagainstclimate risks.Thepartnershiprepresentsapivotal opportunitytotransformSenegal’senergy landscapewhilefosteringbroadersocioeconomic benefits.

Recentdiscoveriesofsignificantoilandgas reservesoffSenegal’scoastlinehavethe potentialtotransformthenation’seconomybut carrytrade-offsforthecountry’sclimategoals.

Production from these recent discoveries began in 2024 at the Sangomar oil field, which is expected to produce up to 100,000 barrels of oil per day. Projections estimate these resources would generate billions of dollars in revenue, presenting a unique opportunity for economic growth and energy sector transformation.

Senegal’s oil and gas discoveries highlight the challenge of balancing economic growth with environmental sustainability. These resources offer opportunities to reduce energy costs, boost revenues, and address critical economic and human development priorities like education and infrastructure. However, reliance on fossil fuels risks undermining Senegal’s renewable energy ambitions and climate goals outlined in the PSE.

As a new entrant to the oil producing community, Senegal has an opportunity to make critical decisions regarding green infrastructure, renewable energy projects, and climate resilience initiatives, ensuring resource wealth supports long-term sustainability. By integrating environmental safeguards and prioritizing sustainable practices, Senegal can use its newfound resource wealth to advance both development and climate objectives, setting an example for resource-rich nations striving for sustainable development.

Dakar’seffortstotackleclimateadaptationand mitigation,aswellasSenegal’seffortsmore broadly,willrequiresignificantadditionalfunding. Historically,climatemitigationandadaptation fundinghascomefromdevelopmentfinance institutionsorofficialdevelopmentassistance, whichmaycomewithconditionalitiesaswellas createunpredictabilityanddisincentivesfor governmentstomaketheirowninvestments.

Fundsfromotherinternationalsources, particularlytheGlobalEnvironmentFacility(GEF) andAdaptationFund,poseotherchallenges— namely,theintegrationofclimatefinancewith botheconomicdevelopmentanddecentralization efforts.Internationalandmultilateralpartners haveleveragedfinancingagreementstosecure commitmentstorenewablepoweringrid modernization,asignificantshiftfromSenegal's currentenergymix,where61%ofenergycomes fromoil. Thispushforrenewableenergy coincidedwithsignificantoilandgasfield discoveriesbetween2014and2016,creating additionaltensionbe-tweeneconomic developmentandclimatechangemitigation goals.

ThePSE,launchedin2014,attemptstoreconcile thesecompetingprioritieswhileharmonizing internationalcommitments,includingtheUnited Nations'2030AgendaforSustainable DevelopmentGoals.ThePSEhasproveneffective inattractingforeigndirectinvestment,withthe InternationalTradeAdministrationnotinga40% increaseinFDIflowsfrom2020to2022, primarilydirectedtowardinfrastructure developmentprojectsrangingfromelectricityand agriculturalproductivityinvestmentstodrinking waterqualityimprovements.

Buildingonthiscontext,inthisreportweconduct adeeperdiveintopolicy,programs,andfinance tocreaterecommendationstosupporttheACFin bettercombatingSenegal’sconfluenceofclimate andeconomicchallenges.

Thisreportwasdevelopedthroughanalysisofa combinationofsecondaryresearchandprimary interviewswithkeystakeholders.Thereport’s objectiveswereco-developedwithourclient,the ACF.Ourworkconsistedofthreecorephases: reviewofliterature,interviewswithkey stakeholdersvirtuallyandin-country,anddata analysisandsynthesis.

Weconductedaliteraturereviewcenteredon threethemes:(1)urbanizationandinformality,(2) development,governance,anddecentralization, and(3)climateadaptationandmitigationpolicy andfinance.Ourliteraturereviewspannedboth academicliteratureaswellasgrayliterature includingpolicydocuments,strategicplans,press releases,andimplementationresources.

Weconductedin-personinterviewswithkey stakeholdersduringoneweekoffieldworkin DakarinOctober2024.Weidentifiedandreached outtokeystakeholdersworkingattheglobal, national,andlocallevels,informedbyour literaturereview.Wescheduledinterviewswithall stakeholderswhorespondedtoouroutreachand wereavailableduringourweekin-country,which primarilyincludedtheACF’sexistingpartners. Duringinterviews,wesolicitedadditional recommendationsandcontactinformationfor otherindividualsandorganizationstospeakwith. Stakeholdersincludedrepresentativesfrom governmentagencies,civilsocietyorganizations, academics,andinternationalinstitutions.Afull listofintervieweescanbefoundattheendofthis report.

Wedevelopedasemi-structuredinterviewprotocol,thatwasadaptedforstakeholder conversations,toaidconsistencyofcoding themeswhileprovidingflexibilitytoexplore specificinsights.Werecordedandtranscribed eachinterviewwithpermission.Forinterviews takingplaceinFrench,wewereaccompaniedby localtranslators.

Followingourin-countryexperience,we conducteddataanalysisandsynthesis,usinga rangeofqualitativedata.

Weidentifiedkeyoverallthemesthatemerged fromourinterviews.Wethenreviewedourinterviewtranscriptstoidentifystatementsand quotescorrespondingtoeachtheme.Inparallel, weanalyzedhowthesesamethemeswere discussedinkeynationalstrategiesand internationalagreementsshapingtheclimate policylandscape:Senegal2050,UrbanMaster PlanforDakar2035,ParisAgreement,andthe JETP.Thesefourdocumentscameupas frequentlyreferencedbothintheliteratureand stakeholderinterviews,highlightingtheir centralityinshapingclimateadaptationand mitigationagendasinDakar,particularlyin aligninglocalinitiativeswithbroadernationaland globalobjectives.WeexaminedhowSenegal's internationalclimatecommitments,asoutlinedin theParisAgreementandtheJETP,areintegrated intothenation'slong-termdevelopment framework,Senegal2050.Atthelocallevel,we analyzedDakar'sUrbanMasterPlanto understandhowittranslatessuchcommitments intoactionablestrategies,aligningthecity's urbanizationgoalswithbroadernationaland internationalobjectives.

Additionally,Dakar’svulnerablecommunities havelongexperienceddisparitiesinclimate adaptationandmitigationefforts,highlightingthe criticalneedtostrengthenunderstandingofthe interplaybetweensocialandclimate vulnerability. Targetedclimateresilienceefforts mustfocusonaddressingtheneedsofthosemost atrisk.Tosupportthis,weconducteda comprehensivegeospatialanalysisusing householdsurveyandgeospatialdatainQGISto examinetheoverlapofclimateandsocial vulnerabilitiesacrossDakarandcreatethemaps thatappearinthisdocument,basedon triangulateddatasources.Thisclimaterisk assessmentshowcaseshowexistingdatacanbe utilizedtoprovidevaluable

existing data can be utilized to provide valuable insights on sub-regional vulnerabilities. The outcomes of the assessment could be beneficial to multiple stakeholders, such as local and regional governments, urban planning departments, disaster management agencies, universities and think tanks, and international development partners to better support vulnerable communities (See Online Appendix: Spatial Analysis for Understanding Social and Climate Vulnerability in Dakar for more details).

Giventhestrongrolethattheclient’sexisting relationshipsplayedinsettingupinterviews,our in-countryinterviewswerebasedonpurposive selectionandarenotfullyrepresentativeofthe broaderstakeholderlandscape.Inparticular, community-basedandprivatesectoractorsare underrepresentedinourinterviews.Additionally, languagebarriersposedachallengetoseveral interviews,wheretranslatorswerenot sufficientlyfamiliarwithtechnicalterminologyor contextualfactorstopreciselyposequestionsor relayresponses.Thislimitationnotonlyimpacted ourfindingsbutalsoreflectsabroaderchallenge forclimateadaptationeffortsinSenegal,as effectivecommunicationandshared understandingarecriticalforfosteringinclusive andcollaborativesolutionsacrossdiverse stakeholders.Ourinterviewanalysis consequentlyreliesonalesssemanticinterview codingtechniquethatfocusesinsteadonthe mainpointsofinterviewees’comments.

Tomeetourstrategicobjectivesasdefinedwith theACF,weconductedaseriesofqualitativeand quantitativeanalysestosupplementour stakeholderinterviewsandbetterunderstandthe currentstateofpolicyandoperationsinSenegal. Theseanalysesrevealasetofcontinued challengesandopportunitiestostrengthen existingworkinclimatepolicyandfinance,which directlyinformourrecommendationstotheACF inthenextsection.

ToaddressStrategicObjective1—toanalyzethe implicationsofthenewlyreleasedSenegal2050 inthecontextofpre-existingpolicyand agreements,withafocusonvulnerable populations–weanalyzehowSenegal2050 intersectswith:(a)urbanpolicy,namelythe UrbanMasterPlanforDakar2035,(b) internationalclimateagreements,chieflythe JETPandParisAgreements,and(c)thenational landscape,namelytheclimatefinanceecosystem.

Senegal2050placesastrongemphasison sustainabledevelopmentasanessential componentofSenegal'slong-termstrategy.It highlightstheneedtoaddressenvironmental challengeswhilefosteringabalancedand equitabletransformation.Thedocument underscorestheimportanceofpreserving biodiversity,integratingacirculareconomy,and transitioningtorenewableenergysystemsaskey measurestoensureasustainablefuture.This visionalsoacknowledgesthecriticalroleof equitableurbanandruraldevelopment,aimingto provideallcitizenswithaccesstoessential servicesandopportunities,irrespectiveof geographiclocation.

Similarly,theUrbanMasterPlanforDakar2035 integratesclimateadaptationandurban resilienceascentralpriorities.Theplan specificallyaimstomitigateurbanvulnerabilities suchasfloodingandheatstressthrough

investmentsingreeninfrastructureand sustainableurbanplaning. Acriticalcomponent ofthisstrategyisitsfocusoninfrastructureasa keyinterventionlinkingclimateresilienceand urbandevelopment.Investmentsinstormwater managementsystems,sustainablehousing,urban transportnetworks,andrenewableenergy solutionsareoutlinedasmeasurestoreduce climateriskswhilefosteringinclusivegrowth. Theseinfrastructureprojectsplayadualrolein addressingenvironmentalchallengesand improvingaccesstoessentialservicesforDakar’s population.

Whilebothframeworksemphasizesustainability andinclusivity,gapsremaininfullyoperationalizingthesegoals.Forinstance,ourgeospatial analysisrevealedthattheUrbanMasterPlandoes notcomprehensivelymapallhigh-riskareas,such asCommunedeParcellesAssainiesand CommunedeDakar-Plateau.Addressingthese omissionsrequiresenhanceddatacollectionand coordinationbetweennationalandurban stakeholderstoprotectvulnerablecommunities fromclimaterisks

Tobridgethegapbetweenurbanizationand climateadaptation,investmentinresilientinfrastructuremustremainacentralfocus.By ensuringtheimplementationofinfrastructure projectslikestormwatersystems,efficienturban transport,andclimate-resilienthousing,the UrbanMasterPlannotonlyalignswithSenegal 2050'semphasisonsustainabilitybutalso addressestheimmediateandlong-term challengesposedbyrapidurbanizationand environmentalvulnerabilities.

Strengtheningcollaborationbetweennationaland urbanstakeholdersremainsessentialtotranslate Senegal2050'saspirationalgoalsintoactionable policieswithinDakar'surbanplanningframework (seeTable1foraside-by-sidecomparisonof salientpolicies).Withconcertedefforts,both Senegal2050andtheUrbanMasterPlancan serveascomplementarytoolstoachievea sustainable,inclusive,andclimate-resilientfuture forSenegal.

GOVERNANCE LEVEL

Domestic Municipal International Multilateral PURPOSE

Achieve economic sovereignty and sustainable development by 2050

MAIN PROVISIONS

CLIMATE FINANCE

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Focus on economic growth, job creation, energy selfsufficiency, and governance

Emphasis on leveraging local resources and reducing foreign aid dependency

Develop a comprehensive urban strategy for Dakar and neighboring areas by 2035

Urban development management, environmental management, inclusiveness, and sustainable land use planning

Not specifically focused on climate finance, but includes environmental management objectives

Triple per capita income by 2050, focus on industrialization and digital economy

SUSTAINABILITY GOALS

Achieve energy selfsufficiency, enhance natural resource management

Global agreement to combat climate change and limit global warming

Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) for emission reductions, climate finance commitments

Developed countries to provide financial resources to assist developing countries in mitigation/ adaptation

Promote economic growth through improved urban infrastructure, public transportation, and service sector development Encourage sustainable economic growth while reducing greenhouse gas emissions

Preserve green spaces, reduce urban sprawl, promote efficient public transportation

Limit global temperature rise to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels

Facilitate Senegal's transition to a lowcarbon economy while ensuring energy access and equity

Increase renewable energy share to 40% by 2030, develop a long-term lowemission strategy

$2.7 billion secured from international partners for renewable energy projects

Support economic growth through investment in renewable energy and infrastructure

Ensure a socially just transition with universal energy access and sustainable development objectives

Senegal2050buildsonSenegal’scommitments tointernationalclimateagreements,includingthe JETPandtheParisAgreement,byprioritizing renewableenergyadoption,emissionsreduction, andlong-termclimateresilience.TheseagreementsformthefoundationofSenegal’sclimate ambitions,withtheJETPaimingtoincrease renewableenergyto40%ofinstalledcapacityby 2030andtheParisAgreementemphasizing NDCstoalignwithglobaltemperaturelimits.

Senegal2050integratestheseinternational goalsbypromotingenergyself-sufficiencyanda greenenergytransitionwhileaddressingsocial inequalitiesthroughinclusivedevelopment.For instance,Senegal2050highlightsthepotentialof renewableenergytocreategreenjobsand improveenergyaccessforunderserved communities,aligningwiththeJETP’sfocuson energyequity.Similarly,theParisAgreement’s emphasisonadaptationisreflectedinSenegal 2050’sstrategiestomitigateclimate vulnerabilitiesinruralandurbansettings.

Despitethesesynergies,criticalgapsremain. TensionsbetweenSenegal’srecentoilandgas discoveriesanditsrenewableenergygoalsunder JETPrevealtrade-offsbetweenshort-term economicgrowthandlong-termclimate commitments.Additionally,international financingmechanismsoftenprioritizemitigation efforts,leavingadaptationneedsunderfunded. ThiscreateschallengesforimplementingSenegal 2050’scomprehensivegoals,particularlyin vulnerableregionsthatrequireadaptation investments.

Amajorchallengeliesintherelianceon internationalfunding,whichcanbypasslocal actorsandexcludemarginalizedcommunities fromdecision-making.WhileSenegal2050aims toharmonizeinternationalcommitmentswith domesticpriorities,limitedlocalcapacityto absorbanddeploythesefundshamperseffective

implementation.Addressingthesegapsrequires strengtheninginstitutionalframeworksand ensuringthatinternationalfundingmechanisms alignwithSenegal2050’sinclusive,equityfocusedapproach.

ThetransformationofSenegal'sgreeninitiatives, includingtosupportSenegal2050,currently involvesandneedstocontinuetoinvolvea complexnetworkofstakeholdersoperating acrossglobal,regional,andnationallevels.Each organizationplaysacrucialroleacrossthreekey strategicareas:financingthetransformation, projectimplementationandmonitoring,and thoughtleadership(seeFigure5).

Infinancing,severalmajorinstitutionshave demonstratedstrongcommitmentstoinclusive development.TheAfricanDevelopmentBank (AfDB)hasbeenfirmlycommittedtocentering women,youth,andothervulnerablegroups throughoutitsprojectdesignsandimplementationefforts.Forinstance,whenevaluatingan electricityaccessproject,thebankgoesbeyond theaggregateincreaseinelectricityaccessand extendstoevaluatingtheimpactsspecificallyon women.Inanotherprojectinstallinghydropower, thebankofficialsincorporatedcommunityfeedbackintheoperation,includingspecificmeetings withwomenintheabsenceofmentoensurea safeenvironmentforwomentoexpresstheir opinions.Similarly,theyinvitedyouthfromthe communitytofocusgroupstounderstandtheir perspectivesandneedsontheprojects.Working alongsideAfDB,otherglobalfinancialactorssuch astheUnitedNationsCapitalDevelopmentFund (UNCDF)focusonmakingfinanceworkfor vulnerablepopulations,andnationalinstitutions liketheSovereignFundforStrategicInvestments (FONSIS)andLaBanqueAgricoleprovide strategicinvestmentandagriculturalfinancing support.

1. Financing the Transition

National Agency for Renewable Energies (ANER)

Ministry of Finance & Budget

2. Project Implementation and Monitoring

Ministry of Interior (Department of Civil Protection) Ministry of Environment & Sustainable Development (MEDDTE)

3. Thought Leadership

Theprojectimplementationlandscapeshows similardedicationtoinclusivepractices.The GlobalGreenGrowthInstitute(GGGI)elevatesthe importanceofincludingwomeninthedecisionmakinganddevelopmentphase.Inarecentsolar panelinstallationproject,GGGIworkedtoensure thatwomenengineersinthecommunitywere involvedintheprocesstosharetheirunique experiencesandperspectives.Additionally,GGGI protectschildrenandyouthfromchildlabourand exploitativeworkintheprivatesector.TheWorld Bank(WB)describestheireffortsinintegrating environmentalandclimate-relatedprogramsinto theprimaryschoolcurriculumtopromoteyouth awarenessandparticipationinclimate-related projects.Meanwhile,WBprovidesfundingfor smallurbanprojectsforyouthtobeinvolvedand appreciatestheimplementationofclimaterelatedprojects.

InthoughtleadershipaddressingSenegal’s climatetransition,regionalthinktankssuchas theAfricaPolicyResearchInstitute(APRI)and WestAfricaThinkTank(WATHI)contribute valuablelocalperspectivestopolicydiscussions. Theseeffortsarecomplementedbynational researchcentersliketheCentreforResearchand ActiononEconomic,SocialandCulturalRights (CRADESC),whichensureseconomicandsocial rightsremaincentraltodevelopmentinitiatives.

TosupportSenegal2050,eachplayerinthis multi-layeredstakeholderecosystem,fromglobal tolocallevels,mustcontinuetobeengagedto ensurethatSenegal'sgreentransformation benefitsallmembersofsociety,withparticular attentiontowomen,youth,andvulnerable populations.Further,asthefirstAfrican-led strategicgrantmakeroperatingatthe intersectionofclimatechangeanddevelopment, theAfricanClimateFoundation(ACF)occupiesa uniquepositioninthisecosystem,servingasa vitalbridgethatspansallthreestrategicareas: abletochannelfinancing,support implementation,andprovidethoughtleadership whileworkingfluidlyacrossglobal,regional,and localcontextstounlockdevelopment opportunitiesinclimateactionthroughoutAfrica.

Takentogether,thecurrentstatedescribedabove revealsaseriesofchallengesandopportunitiesto strengthenpoliciesforclimatefinanceand climatemitigationandadaptation.Inalignment withStrategicObjective2—toidentifythe challengesandopportunitiesinclimaterisksand finance—thissectionfocusesontheremaining gaps,consideringpastandongoingeffortsto addresschallenges.

Wehaveorganizedthechallengesand opportunitiesintofourthemes:(1)data availability,(2)institutionalcapacity,(3) governanceofthegreenenergytransition,and (4)urbanizedinfrastructure.

Althoughtherehasbeenprogressoverthepast decadeestablishingdatatosupportclimate action,severallimitationspersist:insufficient(1) usabilityofclimateriskandvulnerabilitydata,(2) prospective,disaggregateddataonavailable supplyanddemandofclimatefinancing,and(3) marketandmodelingdata.Thesechallenges affecttheclimatepolicyandprojectprocessfrom end-to-end,limitingdesign,implementation, financing,andmonitoringandcontinuous improvement.

TheNationalAgencyforStatisticsand Demography(ANSD),theMinistryofEnvironment andSustainableDevelopment(MEDDTE),andthe NationalCommitteeonClimateChange (COMNACC)leadeffortstoproduceandutilize climatedata,supportedbynon-governmentaland internationalorganizationsincludingthe SenegaleseInstituteofAgriculturalResearch (ISRA),InternationalCooperationCenterfor AgriculturalResearchandDevelopment(CIRAD), andResearchInstituteforDevelopment(IRD). Over78climateindicatorsarecurrentlyproduced andaccessiblethroughonlineportals.

52

Effortsareunderwaytofurtherenhancedata availability:ANSDandRufisqueAgglomeration Community(CAR)areworkingtoestablisha

statistical framework to monitor and evaluate public policies and programs at the regional level; ANSD, MEDDTE, and COMNACC are integrating climate change data into policy making and monitoring activities under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change; CSE is organizing capacity building workshops to enhance staff proficiency in monitoring and analyzing weather data; and the Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar (UCAD) conducts diagnostics and surveys in municipalities to gather local data and support municipal master plans to align adaptation strategies with community needs.

However, despite this progress, 112 indicators are still needed to monitor development plans related to climate change. This count does not include the potential new data needs associated with Senegal 2050. In 2023, the Partnership in Statistics for Development in the 21st Century (Paris21) identified two continued weaknesses in Senegal’s climate change data environment. First, resources are insufficient for sustained production of disaggregated, timely, and usable environmental and climate change statistics. Second, there is a shortage of technical capabilities for using climate change and related statistics, including GIS analysis and visualization. Our field interviews affirmed these weaknesses. Stakeholders identified two main drivers of these challenges: insufficient resources for ongoing data collection, maintenance, storage, and capacity building, as well as a lack of standardized protocols for data sharing between agencies, research institutions, and local governments, resulting in fragmented planning and decisionmaking.

Our interviews further highlighted the downstream implications of these data limitations. As representatives from the World Bank Group noted, "When you want to address challenges linked to climate change and climate impact, you need data and you need modeling. [But in Senegal,] data scalability is a real problem," (2024). A key contributor to data challenges is the fragmentation of data systems—data is often siloed within specific agencies or organizations, making it difficult to integrate or share across stakeholders. This issue is exacerbated in

resource-constrainedsettings,wheretechnical infrastructureanddatamanagementcapacity maybeinsufficient.Thischallengeisparticularly pronouncedforadaptationprojects,where proposalstypicallyrequireextensivebaseline dataandclimatemodeling.Thecombinationof insufficientdataandcapacitycreatesacircular problem,whereaccessingsustainedfundingis moredifficult,andlimitedfunding,inturn,makes itdifficulttoimproveneededdatacollectionand analysiscapabilities.

AccordingtoSenegal'sNDC2020,Senegal's cumulativefinancingneedstoadequately respondtoclimatechangeareestimatedatUSD $13billionover2020-2030,withUSD$8.7billion neededformitigationandUSD$4.3billionfor adaptation. Onaverage,theseneedsamountto $1.3billion(6.1%ofGDP)annually,$870million formitigationand$430millionforadaptation. Thisamountdoesnotcoveraspectsrelatedto capacitybuildingatthelocallevel,estimatedat $0.1billionduringtheperiod2020-2030. However,limiteddataareavailabletosupport differentactorsinunderstandingclimate financingneedsatthecommunityandproject level.Thesedataareneededtohelpguide allocationofresources.

Fundingagencieshighlightanapparentdearthof knowledgeregardingthecurrentdemandfor climatefinancing.Nostakeholderweinterviewed wasawareofrobustdatasourcesonclimate financingdemand,atanylevelofaggregation.As oneindicationofthelevelofneedforthisdata, theGCF,throughitsReadinessProgramme, providesdevelopingcountrieswithanallocation ofuptoUSD$3millionfortheformulationof NationalAdaptationPlans(NAPs)andother adaptationplanningprocesses.However,as referencedinaninterviewwithFONSIS,uptake hasbeenlow,suchthattheGCFissettoincrease thisallocationtoUSD$4millioninanattemptto generateinterestandsolicitproposals.

Similar data availability and granularity challenges exist regarding climate finance supply. The CPI regularly aggregates climate finance supply data bottom-up from other stakeholders’ data sets and reports to provide an overall picture of the state of climate finance at a country level. In its most recent 2024 data set, the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) estimates that across 2019/2020, $562 million of primary climate financing was available across Senegal.

However, the CPI data set is a static and retrospective resource. The main need for climate finance supply data is to provide different actors with a prospective understanding of where to access climate financing and how. Moreover, most sources of funding captured in the CPI dataset are only accessible to national governments and cannot be pursued by subnational actors. We are unaware of any datasets that support local actors in identifying viable sources of funding to address certain needs or projects.

Paris21identifiedkeyweaknessesinSenegal’sclimatechangedataecosystemasashortageof dataavailabilityandusability,aswellastechnicalcapabilitiessuchasforGISanalysisand visualization.Ourteam’sgeospatialanalysisdemonstratesakeyusecaseforenhancingsuchdata andtechnicalcapabilities:toanalyzeclimateandsocialvulnerabilityinDakarandidentifythe highest-riskcommunitiesinneedofclimateadaptationprojectsupport.

Inourgeospatialanalysisofclimateandsocialvulnerability(seeOnlineAppendix:SpatialAnalysis forUnderstandingSocialandClimateVulnerabilityinDakarformoreinformation),wefoundthat southernandcentralareasofDakarexperienceveryhighclimaterisk.Forexample,the ArrondissementdeDiamniadio,locatedaboutthirtykilometersfromthecenterofDakar, experiencesthehighestclimaterisk.TheUrbanPoleofDiamniadiowascreatedin2014withthe goalofturningitintoanewurbancenteranddecongestingthecapital.However,Diamniadiois locatedinaflood-pronearea,mainlycomposedofswellingclay,marlstone,andlimestone unsuitableforconstruction. Withincreasedprecipitationandrainfallsince2000,thisregionis highlyvulnerabletohydrologicalhazardsandneedsimmediateattentiontoenhanceitsresilience.

Additionally,easternandnortheasternDakarexperiencehighlevelsofsocialvulnerability comparedtoregionswithlowvulnerabilityincentralandwesternDakar.Forinstance,Unit13within ParcellesAssinies,locatedinthenorthernpartofDakar,hasthehighestsocialvulnerability.A ParcellesAssiniesprojectwasdesignedtoaddresshousingneedswiththeurbanexpansion, especiallyforlow-incomehouseholdsintheinformalsector.Althoughtheprojectsupplied householdswithbasicinfrastructureandservices,therecentDemographicandHealthSurvey (DHS)showstheneedforhigheraccesstoelectricityanddrinkingwaterandhighrelianceon agricultureproduction.Thesecharacteristicsreflecttheregion’svulnerabilitytoclimateriskdueto alackofinfrastructureandlimitedeconomicresilience,highlightingtheneedtostrengthen infrastructureandeconomiccapacitywiththeriseofclimaterisks.

Thecompositevulnerabilityindexalignscloselywiththesocialandclimatevulnerabilityindex presentedabove.Similarly,easternandnortheasternDakarexperiencedualchallengesofsocial vulnerability(e.g.,poverty,lackofaccesstobasicservices)andclimaterisk(e.g.,susceptibilityto floodingandwaterscarcity).Incontrast,westernDakarexperiencesrelativelylowvulnerability. Thesedisparitiesemphasizetheneedfortargetedresourceallocationtoaddressandmitigate vulnerabilitiesinthemostaffectedregions.

Detailed SpatialAnalysisforUnderstandingSocialandClimateVulnerabilityinDakarcanbefoundat: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1FXcvfVbvWxjOuHFWaP45e1ve9g1IQxNw/view?usp=sharing

Climatefinancemodelsrelyheavilyonaccurate dataaboutconsumermarkets,socioeconomicand geographiccharacteristics,andenvironmental risks.Theseinputsarecrucialforassessing financialfeasibility,tailoringinterventionstolocal conditions,andreducinguncertaintyfor investors.

However,alackofaccessibleandreliabledatain Senegalunderminesthereliabilityofthese models.Keygapsincludedataonhousehold incomelevels,consumptionpatterns,geographic vulnerabilities,andtheeconomicimpactof climateadaptationmeasures.Forinstance, financialmodelsforrenewableenergyprojects oftenrequiregranulardataonconsumerdemand, includingincomeelasticity,energyconsumption trends,andtheabilitytopay.Onekeyfinancial stakeholder(FONSIS)highlightedthatthese missingdatapointsincreaseperceived investmentrisks,makingitdifficulttoattract financingandraisingcostsforclimate-related initiatives.

Thischallengeisparticularlysignificantfor adaptationprojects,suchasflood-resilient housing,wheremissinginformationonlocalrisks andaffordabilityfurtherlimitsthedevelopmentof bankableprojects.Thesedatagapscontributeto acyclewhereinsufficientdatadetersinvestment, andlimitedinvestmenthampersthecreationof comprehensivedatasystems.

Thesuccessfulimplementationofclimate-related measuresinSenegalisfundamentally constrainedbyinadequatecapacity.These inadequaciesimpedethedevelopmentof‘soft’ architectureneededtoimplementprojectsand heightenthecomplexityofmeetingstandards neededforaccessingvitalfunding.Without sufficientcapacity,therearedifficultiesin preparing,tendering,andoverseeingprojects.

Inacontinuallychanginginternationalpolicy context,itisdifficultforgovernmentagenciesto keepupwithnewregulationsandopportunities. Forinstance,governmentagenciesarestruggling

tounderstandhowtoapplyforandleverage emergingformsofclimatefinance–everything fromapplicationcriteriaforinternationalclimate funds,tounderstandinghowtomobilize additionalfinanceforblendedfinance.AsanAfDB bankrepresentativeexplained,"GCFproposals.. [requireapplicationsupto]170pageswith annexesandcalculations."Thistechnical complexitymeansthatmanylocalandnational entities,intherepresentative’swords,"arenot yetequippedtobeabletotacklethat,"(2024). Whilemultilateralinstitutionshavesubstantial capitalavailable,actuallydeployingthose resourcesremainsachallenge.Whilesignificant progresshasbeenmadetowardsmobilizing capital,Senegalstillrequirescapacityinvestment anddevelopmenttoensureflowsreachrelevant projectsandstakeholders.

However,werecognizethatdifferentactorsare betterpositionedtooperateathighcapacities andinsufficientcapacitydoesnotcharacterizeall actors.Forexample,Dakar’sMunicipal DevelopmentAgency(ADM)isworkingto strengthenthecapacityshortcomingsthatso frequentlyplaguetheclimateadaptationand mitigationspace.InourdiscussionwithADM, representativeshigh-lightedtheirowncapacitybuildinginitiatives,including“skillsenhancement andlocalplanningimprovements.”Byseekingto systematizebestpracticesandengageand educatelocalcommunitiesthroughouttheproject lifecycle,agenciescandirectlyaddresscapacityrelatedchallenges.

Ambiguouspoliciesandoverlapping responsibilitiesamonggovernmentagenciescan exacerbateinstitutionalchallengesinnumerous ways.Fragmentationandinsufficiently coordinatedgovernmentstrategyinvite internationalactorstosettheconditionsfortheir engagement. Institutionalweaknessesallow externalactorstohaveoutsizedinfluencein policy-makingprocesses.Forexample,Senegal’s NationalElectricityAgency(Senelec)underwent un-bundlingandprivatizationreformsunder pressurefrommultilateralactorsleveraging financialinfluence.

Greenjobandgreenentrepreneurshippromotion, astatedgoalofthenationalgovernment,is insufficientlysupported.Ourconversations highlightedadisconnectbetweenhigh-level policyobjectivesandtheavailabilityoftraining andfundingforlocalentrepreneurs,whichlimits thescalabilityofgreeneconomyinitiatives.One cityofficialnoted,“ourpoliciesalwaysinclude sustainabledevelopmentconsiderations, encouragingyoungentrepreneurstoadopt sustainablepracticesintheirprojects.”However, withouttargetedinvestmentsandcoordination, policiesmayfailtoachievetheirintendedimpact.

Weakenforcementofzoninglawshasallowed unregulatedconstructioninflood-proneand high-riskareas,particularlyininformal settlements. Senegal2050emphasizesland-use reformsandbalancedurbangrowthtoreduce suchvulnerabilities. However,asoneofthe governmentstakeholdersfromourmeetingsin Dakarexplained,enforcementmechanisms remaininconsistent,andinformalsettlements continuetoexpandwithoutadequateservicesor infrastructure.Equitableland-usereformsare neededtoensurethatallcommunitiesare includedinclimate-resilienturbanplanning.

Attractinginvestmentforclimate-relatedprojects dependsheavilyontransparency,reliability,and stablerevenueprojections,allofwhichareoften guaranteedintheformofeligibilityrequirements andconditionalities.Whiletheseconditionshelp promoteinvestorconfidence,theyalsoplace substantialdemandsonthecapacityof developingnationslikeSenegal.These conditionalitiesincreaseprojectcomplexityand requireSenegaleseinstitutionstobuildcapacity inareaslikecompliance,evaluation,andreporting inordertomeethigherstandards.These requirementsplaceadditionalburdenson ministriesandstakeholdersalreadyfacing limitationswithintheirroles.Therequirementto meetfirmenvironmentalandsocialsafeguards pairedwiththeneedforongoingcompliance, evaluation,andreportinghasincreasedthe demandfortechnicalexpertisewithininstitutions thatmayalreadybestretchedforsufficient

resourcesorstaff.Ontheotherhand,the structuringofprojectsinthiswayinviteslocal ministriesandrelevantstakeholderstoprovide valuableinputonprojectexecutionand maintenance.

Projectpreparation,specificallyforrenewable energyprojects,alsorevealsthechallengesand opportunitiesrelatedtoinstitutionalcapacity. StakeholdersfromourmeetingsinDakarciteda shortageof‘bankable’projects,meaningthat whilethereisdemandandmarketopportunities, projectstructuresareoftennotprofitableor attractivetoinvestors.Moreover,evenwithan influxofcapital,theremustbesufficientcapacity toabsorbfunding.Alackofawarenessregarding fundingopportunities,oralackofcapacityto implementprojects,canleadtomissed opportunitiesinaccessingcriticalfinancial support.

PlayerssuchastheGermanAgencyfor InternationalCooperation(GIZ)areworkingto combatthischallenge.GIZhasconducted workshopsforlocalauthoritiesininformal settlementsonenergyefficiency,community engagement,andequityinclusiontoensurethey canhandletherapidsustainablegrowthinthese areas.Similarly,AfDBtiesclimatefinancein informalsettlementstocapacitybuildingto ensurethatutilitiesandlocalauthoritiesare trainedtoincorporateclimateadaptation measuresintheseareas.

Lackofcommunicationamongrelevantactors canalsohinderprojectdevelopment.For instance,stakeholdersfromourmeetingsin Dakarreportedthatrenewableenergyprojects oftenfacechallengesintegratingintonational gridsduetomisalignmentbetweentheenergy sectorandmunicipalurbanplans.Thiscanleadto projectsthataredisjointedinnature.Similarly, urbaninfrastructuredevelopmentfrequently excludesconsiderationsforclimateresilience, resultinginunsustainablegrowthpatterns. Conversationswithinnovativefinanciers,suchas LBA,suggestthatdurabilityisthegoalwhen securingclimatefinance.Awareofcapacity

The Scaling Solar project exemplifies capacity constraints. For instance, the Electricity Sector Regulation Commission (CRSE), a pre-existing regulatory body, was required to enhance its abilities to effectively manage large-scale solar projects. Additionally, the project required updates to regulatory frameworks, particularly around Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), to meet international standards and attract investment. This relationship was made viable through the 'take-or-pay' structure in PPAs, which ensures that private sector investors are guaranteed payment for a certain amount of electricity, even if the government does not end up using all the power due to issues like grid limitations. While this approach provides security for investors, making their participation more likely, it also places a financial burden on the governmental entities, which may have to pay for power it ultimately cannot use.