A PARTNERSHIP IN TRANSITION:

VISION 2030 AND THE FUTURE OF THE U.S.-SAUDI

BILATERAL RELATIONSHIP

January 2025

VISION 2030 AND THE FUTURE OF THE U.S.-SAUDI

BILATERAL RELATIONSHIP

January 2025

Saudi Arabia has long been a critical partner for the United States, serving as a foundation of U.S. policy toward the Middle East, a leader in global energy markets, and a pivotal actor in Middle Eastern diplomacy. The introduction of Vision 2030 in 2016 marked a transformative shift in this relationship, reframing Saudi Arabia’s role on the global stage as it seeks to diversify its economy, reduce its dependence on oil, and establish leadership in emerging industries like artificial intelligence, renewable energy, and critical minerals. The Kingdom’s transformation provides new avenues for cooperation in the bilateral relationship, while also posing new risks.

This report, A Partnership in Transition: Vision 2030 and the Future of the U.S.-Saudi Bilateral Relationship, offers an in-depth analysis of the evolving U.S.-Saudi partnership in light of Saudi Arabia’s ambitious Vision 2030 agenda. Section One traces the historical foundations of the bilateral relationship, highlighting its enduring strategic pillars and examining how Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s (MBS) leadership has reshaped these dynamics. Section Two delves into the energy sector, which has long underpinned the bilateral relationship through oil, but now includes renewable energy, a potential civil nuclear program, and hydrogen exports. Section Three explores key areas for both future collaboration and potential competition, including emerging sectors such as artificial intelligence, semiconductor chips, and critical minerals, all relevant to great power competition between the United States and China. Section Four broadens in scope to discuss the general investment environment in Saudi Arabia, outlining issues U.S. policymakers and firms should continue to monitor.

The success of Vision 2030 remains uncertain. Its reliance on top-down reforms under MBS introduces risks, including societal backlash and potential instability. Moreover, Saudi Arabia’s non-aligned approach between the United States and China adds complexity to the bilateral relationship, as Riyadh seeks opportunities from both Washington and Beijing. Policymakers must carefully navigate these uncertainties, addressing human rights concerns while ensuring reforms foster inclusive and sustainable growth.

Through this analysis, the report provides policymakers with actionable insights and policy recommendations to manage the complexities of the U.S.-Saudi relationship, emphasizing critical sectors such as security, energy, and technology. By addressing the opportunities and risks

inherent in this transformative period, the report seeks to equip U.S. leaders with the tools necessary to foster a partnership that advances mutual strategic interests while mitigating potential challenges.

This report includes recommendations that U.S. policymakers can adopt to navigate these changing dynamics. More detailed information on the recommendations is included within each section of the report.

Dimensions of the Bilateral Relationship

• Leverage Saudi Arabia’s Strategic Interests to Advance U.S. Goals

• Cooperate on Regional Stabilization and Reconstruction Efforts

• Prioritize Human Capacity Building

Energy: Oil Production and the Electricity Sector

• Utilize Energy Dialogues for Oil Diplomacy

• Invest in Joint Research on Carbon Capture and Storage Technologies

• Cooperate on Key Renewable Energy Sectors

• Continue to Negotiate a Civil Nuclear 123 Agreement

Emerging Technologies

• Strengthen Export Control Coordination with Allies

• Establish Educational Exchanges on Artificial Intelligence

• Formally Secure Shared Interests in Critical Minerals

Investment Considerations

• Maintain Guidance for U.S. Firms on Saudi Arabia’s Investment Environment

• Promote Labor Market Development Partnerships

This report aims to help U.S. policymakers gain a better understanding of the history of the U.S.-Saudi bilateral relationship, understand where emerging priorities for Saudi Arabia could pose opportunities for greater collaboration, and identify where risks remain in the bilateral relationship. The document examines Saudi Arabia’s economic history and recent efforts to modernize; opportunities and risks to the security relationship; the role shifting energy demands and emerging technologies play in shaping bilateral ties; and key uncertainties that could affect Saudi Arabia’s efforts to diversify. The contents of this report have been reviewed and updated to assure accuracy and relevance through December 21, 2024.

This publication was created for our client, the Middle East Institute (MEI). This report represents the analytical conclusions of the authors, and not those of MEI.

MEI is a non-partisan Washington-based think tank dedicated to studying the Middle East. MEI provides expert policy analysis, offers educational and professional development services, and serves as a hub for engaging with the region’s arts and culture. Find out more at https://www.mei.edu/.

This report was produced by twelve second-year students in the Master in Public Affairs (MPA) program at Princeton University’s School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA). It was completed under the supervision of Dr. Nicholas Lotito and fulfills the requirements of the Princeton SPIA MPA program.

Amana Abdurrezak

Maria Dooling

Jackson Blackwell Joshua Heupel

Nick Brown

Maddie Davet

Emily Davies

Dylan Gates

Anna Schaeffer

Rafael Swit

Sydney Taylor

Jennifer Williams

We extend our gratitude to the current and former government officials, scholars, journalists, and business leaders who generously offered their expertise and time to this policy workshop. The insights and resources they shared during interviews conducted in the United States and Saudi Arabia were pivotal in shaping and informing this report.

©2025. Princeton University, School of Public and International Affairs

Over 80 years ago, the bilateral relationship between the United States and Saudi Arabia began to take shape with the establishment of diplomatic ties in 1940 aboard USS Quincy and through the creation of the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco) in 1944. This critical partnership has been anchored in a security-for-oil arrangement since the end of World War II, with U.S. protection ensuring the movement of Saudi Arabia’s vast oil reserves. The Cold War period saw the United States rely on the Kingdom and Iran as part of its “Twin Pillar” policy to project stability in the region. This era also further solidified this partnership with Saudi oil playing a crucial role in rebuilding Europe and supporting mutual interests in countering communism. However, the relationship soon faced significant strains due to differing views on Israel and incidents like the 1973 oil embargo that caused economic turmoil in the West and highlighted their fragile ties.1

Despite strains, Saudi Arabia’s critical political and cultural influence in the Middle East—particularly its role as custodian of Islam’s holiest cities, Mecca and Medina—along with shared strategic priorities, such as stabilizing the Gulf and later countering Iranian aggression, have helped keep the partnership intact. This has largely remained true even as human rights concerns and political tensions have complicated the relationship over the years.

Mutual interests in ensuring regional stability in the Middle East have remained foundational to the bilateral relationship. This is particularly evident in the United States’ longstanding goal of normalizing ties between Saudi Arabia and Israel.2 The United States views such normalization as crucial to maintaining its influence in the Middle East, ensuring Israel’s security and long-term stability, and containing adversarial influences.3 For Saudi Arabia, normalization holds value in its economic opportunities and geopolitical leverage, particularly in securing a defense agreement that it views as vital for deterring Iran and maintaining its national security.4

Opportunities to collaborate on shared interests have blossomed into cooperation across multiple sectors. The partnership has focused

on enhancing security, namely fortifying coastal and border defense, as well as cybersecurity and counterterrorism.5 In other sectors, cultural and educational exchanges have been established for students, professionals, and researchers alike.6 Furthermore, economic ties have strengthened trade between and investments in both countries, facilitated by the establishment of the Trade Investment Framework Agreement in 2003.7

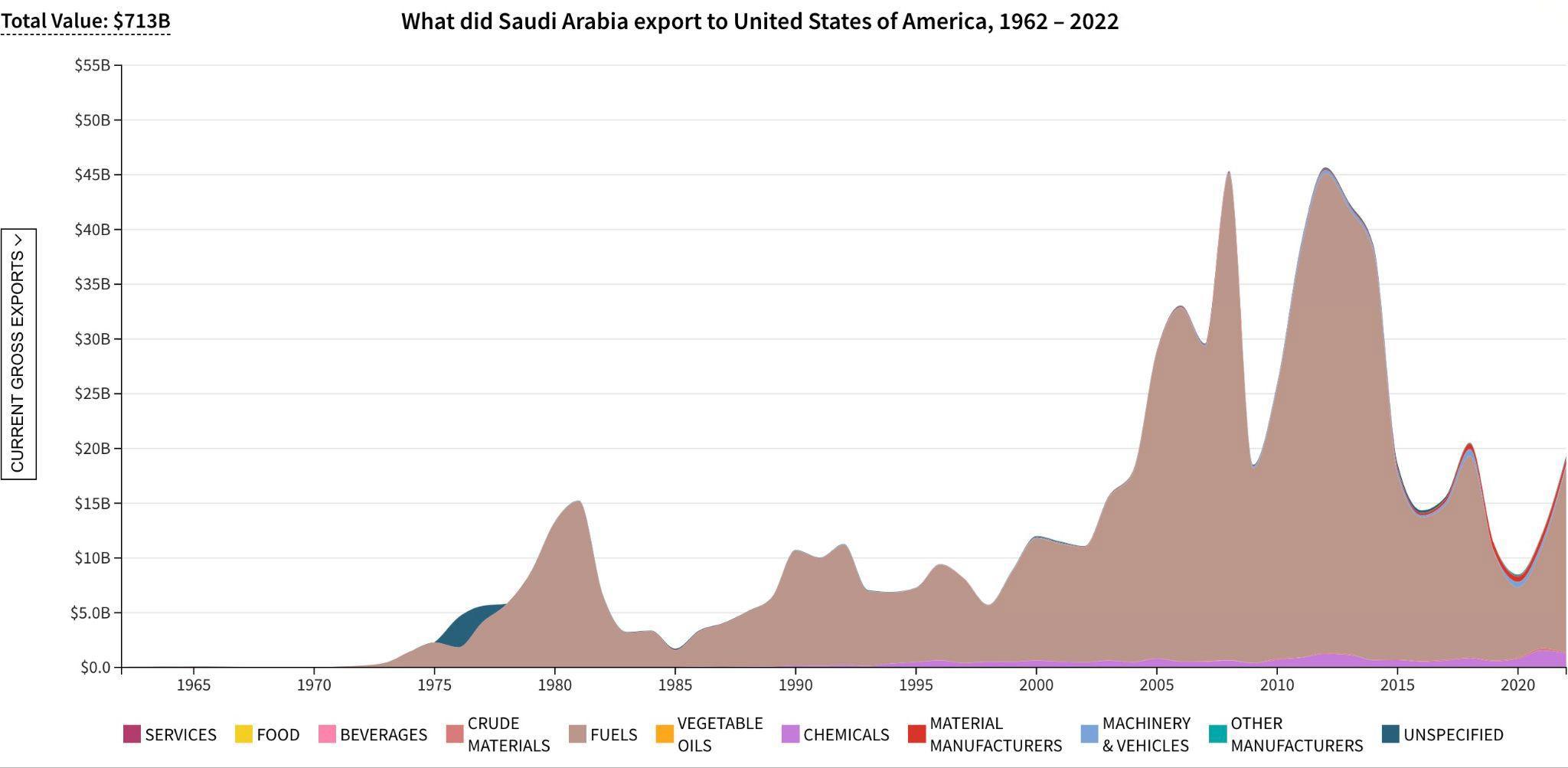

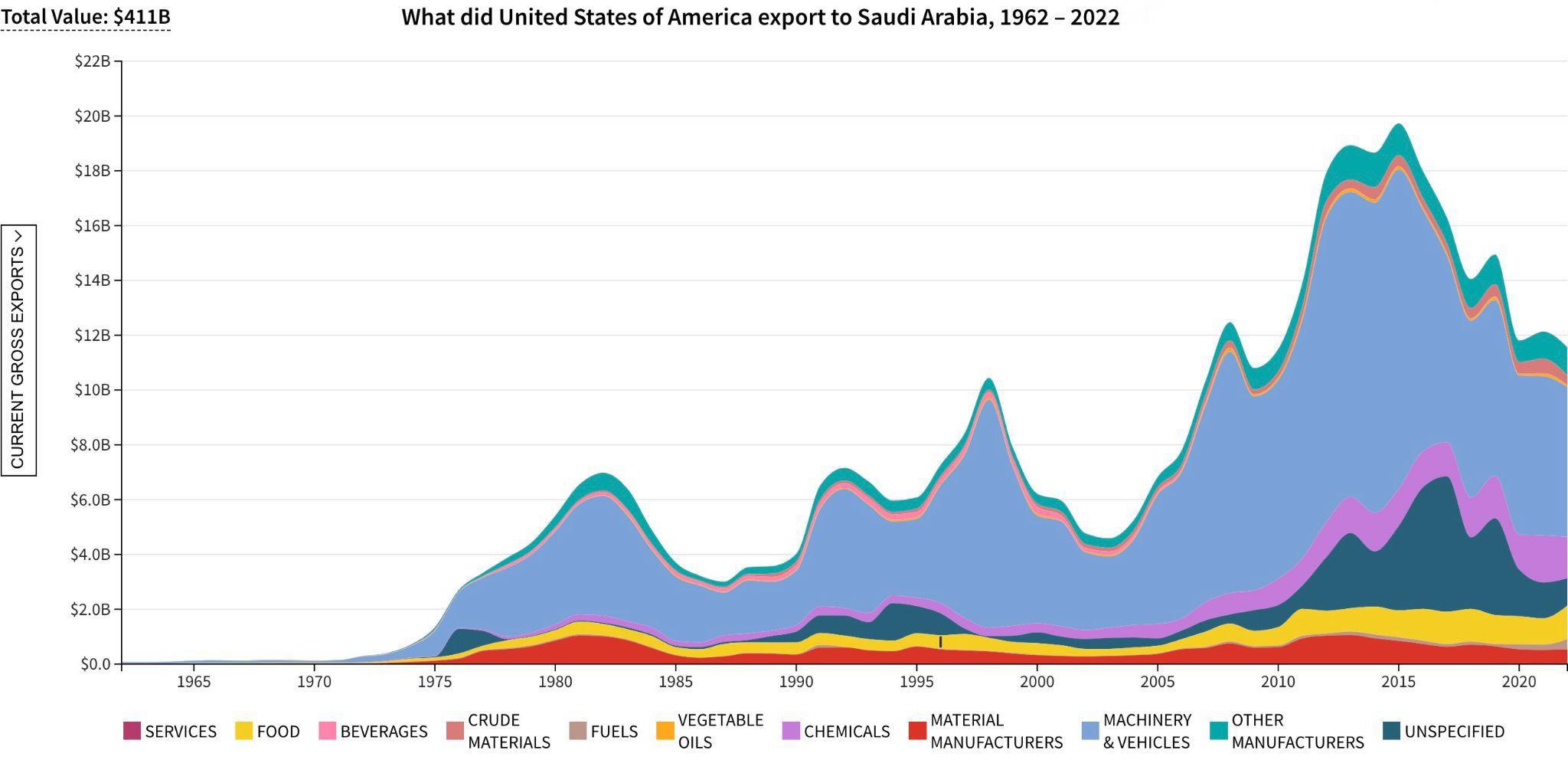

The United States and Saudi maintain a robust economic relationship. In 2022, total U.S.-Saudi trade in goods and services reached $46.6 billion, with crude oil exports dominating U.S.-Saudi trade. The United States exported $21.6 billion to Saudi Arabia and imported $24.9 billion from the Kingdom, resulting in a $3.3 billion U.S. trade deficit. The United States is Saudi Arabia’s fifth largest export destination, while Saudi Arabia ranks as the 30th largest U.S. trading partner.8

U.S. imports from Saudi Arabia mainly consist of crude oil imports which peaked in 2012 before declining as the United States met more of its own oil demand from domestic sources.9 Crude continues to dominate imports from Saudi Arabia, but a more balanced trade deficit reflects the Kingdom’s weakened influence on U.S. oil markets. Meanwhile, U.S. imports of petrochemicals and machinery have slightly risen over time.

U.S. exports to the Kingdom are more diverse, consisting of transportation equipment ($4.75 billion), non-electric machinery ($2.08 billion), chemicals ($1.48 billion), and food ($1.20 billion).10 The United States also has $126.6 billion in active cases in the Foreign Military Sales to Saudi Arabia, with over $27 billion in sales to date.11 The figures on the next page show the trade relationship between the United States and Saudi Arabia.12

Source: Atlas of Economic Complexity

The Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) holds $139 billion in U.S. Treasury securities to maintain the Saudi Arabian Riyal’s peg to the U.S. dollar. In the last two years, SAMA increased its Treasury holdings by $30 billion and now holds about 1.6 percent of Treasury securities held by foreign investors.13

Public and private sector Saudi investors hold approximately $207 billion in U.S. equities, representing a tiny fraction of total foreign holdings of U.S. equities ($17.5 trillion as of October 2024).14 The Public Investment Fund (PIF) is one of the largest Saudi investors in U.S. equities, holding around $26 billion in U.S. stocks as of September 2024. Close to 50 percent of PIF holdings are in Uber, Lucid, and Electronic Arts Inc. (“EA Games”).15 Holdings are down from a peak of $36 billion in September 2023, potentially reflecting a strategic shift to prioritize domestic investments by the Kingdom.16

In 2023, Saudi Arabia’s total FDI stock in the United States reached approximately $7.5 billion, an increase of about $1.5 billion since 2016, accounting for around 0.1 percent of the total FDI stock in the United States.17

U.S. FDI stock to Saudi Arabia totaled $15.4 billion in 2023, an increase from $13.1 billion in 2016. FDI from the United States is around seven percent of the Kingdom’s inbound FDI.18 U.S. FDI to Saudi Arabia is primarily from nonbank financial firms, and the mining and wholesale trade industries.19

Saudi Arabia is the world’s 19th largest economy, the second largest in the Middle East behind Turkey, and the largest economy in the Gulf. Saudi Arabia’s GDP grew from approximately $665 billion in 2016 to $1.07 trillion in 2023. In 2023, its economy contracted by 0.8 percent, due in part to a fall in oil prices. 20,21,22 Saudi Arabia’s debt-to-GDP increased from zero percent in 2016 to 26 percent in 2023 reflecting large investments associated with Vision 2030.

Saudi Arabia has increased exports in petrochemicals, fertilizers, and aluminum over the last decade. In 2022, petroleum-related exports were nearly 72 percent ($255.6 billion) of the Kingdom’s total exports. Non-oil exports were valued at $99.4 billion, up from approximately $60 billion a decade ago. Much of the growth in non-oil exports is from petrochemicals produced mainly by Saudi Basic Industries Corporation (SABIC). Beyond petrochemicals, Saudi has expanded exports in fertilizers. Furthermore, a joint venture between state mining company Ma’aden and Alcoa in 2009 led to the mining and processing of aluminium, now worth $2.5 billion per year.

The Kingdom’s labor market continues to improve. The unemployment rate stands at a historic low of 8.5 percent. Total labor force participation rose from 40 to 50 percent from 2016-23 as a result of women entering the labor market in large numbers. From 2016-23, the female labor force participation rate rose from 22.8 percent to 36.2 percent.23

Vision 2030, Saudi Arabia’s plan to reestablish itself as “a vibrant society, a thriving economy, and an ambitious nation,” serves as MBS’s blueprint for creating a more sustainable and diversified Saudi economy.24 First announced in April 2016, Vision 2030 lays out a plethora of social, economic, energy, cultural, and governance goals that aim to reduce the country’s dependence on oil and position itself as a leader in several emerging industries.25 A number of social reforms (e.g., restructuring of the healthcare and education sectors) complement these economic goals, underscoring ways to create a workforce that can support the country’s push towards leadership in promising sectors.

Notably, Vision 2030 has served as the guidepost for the Kingdom to “open up” and reintroduce itself on the global stage. Sectors like tourism and entertainment play a central role in reshaping Saudi Arabia’s image, as it seeks to attract a broad range of visitors—casual, religious, and luxury— while addressing the social and recreational needs of its own population, especially its youth (see section 1d. Cultural and Public Diplomacy).26 In

parallel, giga-projects such as the Red Sea Project, Diriyah Gate, Qiddiya, and NEOM play a role in creating new economic ecosystems that fuel diversification efforts and attract further traffic to the Kingdom.27,28

Vision 2030 reflects Saudi Arabia’s broad ambition to elevate its global standing. This objective precipitates Saudi Arabia’s efforts to distance itself from its historical association with Wahhabism, a more traditional interpretation of Islamic doctrine and law.29 However, achieving this requires balancing a complex set of factors, including modernizing to meet global aspirations without undermining traditional values and religious roots. Ultimately, this pivotal strategy

document is the Kingdom’s blueprint to address an enduring conundrum: how to actualize its global and domestic aspirations, while still maintaining its cultural and religious identity.30

Vision 2030 signals Saudi Arabia’s aspirations to transform its society and bolster its global position, but by the ambitious nature of the reforms, Saudi Arabia faces many challenges in successfully implementing Vision 2030. The document provides insight for U.S. policymakers into the motivations of the Kingdom, making it necessary for interested parties in the United States to understand associated opportunities and risks as they navigate the U.S.-Saudi bilateral relationship.

The U.S.-Saudi relationship is rooted in shared interests, namely security and oil. Throughout their decades-long relationship, alignment on strategic priorities further solidified their partnership, even as their differing political systems, views on regional conflicts, and values introduced moments of tension.31 These shared interests and strategic considerations, along with scope for alignment with Vision 2030, underscore the Kingdom’s continued position as one of the important U.S. partners in the region.

Key Takeaway: Despite historical tensions, the U.S.-Saudi relationship endures, driven by strategic imperatives, with the Kingdom remaining a critical partner for advancing regional stability, defense cooperation, and countering adversarial influences in the Middle East.

The al-Qaeda terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 marked a watershed moment in the U.S.-Saudi relationship. Of the 19 al-Qaeda affiliated terrorists, 15 were Saudi citizens, and Osama bin Laden, the mastermind behind the attack, hailed from one of the Kingdom’s most successful business families.32 The Saudi government denied involvement and condemned the attack, and the bilateral relationship remained cooperative. Following the 2003 al-Qaeda attacks in the Kingdom, Saudi Arabia took the threat of extremism more seriously and U.S.-Saudi counterterrorism cooperation was significantly enhanced, an effort that continues today.33

Despite cooperation on counterterrorism, the U.S. invasion of Iraq raised Riyadh’s fears that Washington sought closer ties with Tehran. This fear escalated under the Obama administration, given efforts to engage Iran, withdraw from Iraq, and support the Arab Spring.34 Saudi leaders further questioned the United States’ commitment to their security with the administration’s “pivot” to Asia appearing to leave a vacuum for Iran to fill. This tension continued with the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, which the United States viewed as a landmark control on Iran’s nuclear program.35 Washington grew frustrated with Saudi Arabia’s opposition to the deal and its backing of regional counterrevolutionaries, while Riyadh felt the agreement ignored Iran’s destabilizing activities—a dynamic that contributed to Saudi Arabia’s intervention in Yemen.3637

The 2016 Trump administration ushered in a newfound positivity in the bilateral relationship, allowing actions that would have previously strained the U.S.-Saudi relations to draw only muted responses from the Kingdom (e.g., moving the U.S. embassy in Israel to Jerusalem).38 Yet, Saudi Arabia’s fears around U.S. security guarantees continued to grow after the 2019 Iranian attack on two major oil installations operated by Aramco. President Trump publicly threatened a military response, but never launched a retaliatory attack on Iran, instead opting to deploy additional troops to the Gulf and support Saudi’s air defense.39,40 Although not bound by any treaty, the

Kingdom expected U.S. retaliation against Iran due to Trump’s “maximum pressure” policies toward Iran and the oil price spike caused by the attack.41 Around this time, members of Congress and the public became increasingly critical of the Kingdom after the murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi. Though Trump largely shielded MBS, Congress and the American public paid increased attention to human rights violations in the Kingdom and the United States’ role in Saudi Arabia’s escalatory intervention in Yemen.42

Reflecting this mounting criticism, President Joe Biden called Saudi Arabia a “pariah,” pledging to “make them pay” for their actions during his 2020 presidential campaign.43 One of his first actions after his inauguration was halting the sale of offensive weaponry to Saudi Arabia. However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, combined with domestic inflation, raised energy prices and prompted a recalibration.44,45 This highlighted the continued importance of the Kingdom as a swing oil producer. The bilateral relationship improved further in the second half of the Biden administration, as they increasingly recognized Saudi Arabia’s role in regional stability—a dynamic reinforced by Israel’s war in Gaza. In August 2024, the Biden administration lifted its ban on offensive weapon sales to Saudi Arabia, demonstrating once again that broader strategic interests drive the strengthened relationship.46

Alignment on security priorities enables Saudi Arabia and the United States to partner on military and intelligence operations necessary to carry out shared security objectives. Saudi Arabia is the United States’ largest customer of foreign military sales, receiving 80 percent of its defense acquisitions from the United States.47

In terms of deployed forces, as of June 2023, the U.S. military deploys approximately 2,700 military personnel in the Kingdom and hundreds of personnel that support long-standing U.S.-Saudi security cooperation programs for military and internal security forces.48 These cooperation programs serve as an important pathway for closer bilateral ties, facilitating shared intelligence and military coordination. Counterterrorism remains a central focus of these collaborations, as Saudi Arabia seeks to counter extremist ideologies and encourage a culture of moderation in the aftermath of 9/11 and the 2003 attacks on the Kingdom.49,50,51 For instance, Saudi Arabia established and is the second-largest funder of the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Centre, contributing over $110 million since its inception in 2011.52

Prior to October 7, 2023, a U.S.-Saudi-Israel “megadeal” that reportedly included (1) a U.S. defense treaty for Saudi Arabia, (2) normalization of ties between Saudi Arabia and Israel, (3) a civilian nuclear energy program, and (4) dignity for the Palestinian people that fell short of declared Palestinian statehood was said to be within reach.53 However, this deal stalled following Hamas’ attack on Israel and the ensuing war in Gaza, as discontent in Israel, the United States, and the Kingdom eroded public support for a megadeal in the short-term.

Saudi-Israeli normalization remains a “declared national security interest of the United States” and an opportunity to stabilize the region and ultimately pivot away from the Middle East.54 Though the trilateral deal is on hold for the foreseeable future, Saudi Arabia continues to seek a bilateral treaty-level defense pact with the United States. However, treaties require two-thirds ratification of the U.S. Senate, a difficult feat under current political conditions. A U.S.-Saudi bilateral pact, absent progress on normalization, risks diluting U.S. leverage in the region, as Washington typically ties such commitments to broader concessions that align with its strategic objectives. At the same time, the Kingdom’s increasing engagement with rival powers like China and Russia raises the stakes for maintaining a strong partnership, as Saudi Arabia’s hedging and non-alignment strategies risk undermining U.S. regional influence. While offering a pact might secure short-term alignment and counter China’s expanding influence in the Gulf, it could also deepen U.S. entanglement in regional conflicts without securing the long-term benefits normalization could provide.

Saudi Arabia has also expressed interest in receiving U.S. assistance with the establishment and development of a Saudi civilian nuclear energy program as part of a megadeal (see section 2c. Nuclear Energy).55 Additionally, discussions have emerged around a “less-for-less” deal that falls short of a traditional treaty obligation but still includes an expansion of joint military exercises, partnerships between U.S. and Saudi defense firms, investments in advanced technologies, and an increase in weapon sales.56 This deal would likely include elements to prevent Riyadh from collaborating with Beijing in sensitive high-tech areas like artificial intelligence and data center development.57 It remains to be seen which of the aforementioned deals, if any, might gain traction among relevant parties or be preferred by the incoming Trump administration. Balancing the opportunities and risks of any strengthened security partnership requires a cautious approach that safeguards U.S. flexibility and long-term strategic interests.

Key Takeaway: Saudi Arabia’s recent shift toward diplomacy, economic development, and a more balanced foreign policy underscores its evolving role as a vital U.S. partner, crucial for fostering regional stability and countering adversarial influences in a rapidly changing Middle East.

Historically, Saudi Arabia served as a status quo power in the Middle East supporting stability in the region via partnerships with the United States and other Western nations. Following the 1979 Iranian Revolution, Saudi Arabia became the primary counterweight to revolutionary Iran, opposing its ideological and geopolitical ambitions.58 While Saudi Arabia and the United States faced different challenges in aligning their actions with their stated values – particularly around human rights – their mutual interest in containing Iran’s influence and countering Shia revolutionary movements helped sustain their partnership. To counter Iran and extend its own influence, Saudi Arabia exported Wahhabism by funding mosques, madrassas, and Sunni political factions around the world. While this religious soft power reinforced Saudi leadership, critics argue it also contributed to regional radicalization and instability.59

As MBS rose to influence in 2015, the Kingdom adopted a more assertive and interventionist foreign policy, attempting to reshape the region in Saudi Arabia’s image. In doing so, Saudi Arabia shifted from a stabilizing force to a regional destabilizer. The war in Yemen, spearheaded by MBS, devolved into a costly proxy war with Iran, causing one of the largest humanitarian crises without achieving Saudi objectives.60 The Qatar blockade similarly backfired, pushing Qatar closer to Turkey and Iran.61 Additionally, Saudi Arabia’s reported coercion of Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri into resigning under duress damaged its reputation as a reliable regional partner and underscored its heavy-handed and controversial approach to regional diplomacy.62 These ventures failed to achieve their desired outcomes, instead contributing to a global perception of MBS as belligerent, unpredictable, and impulsive. These setbacks and reputational damage prompted a recalibration of Saudi foreign policy, with MBS pivoting toward diplomacy and mediation. In recent years, Saudi Arabia has prioritized de-escalation, as exemplified by the 2022 ceasefire with the Houthis and the Chinesemediated 2023 détente with Iran.63 The Kingdom now relies on economic and development initiatives rather than religious export to exert influence, and increasingly

seeks to position itself as a regional and global diplomatic heavyweight. This shift is not merely a change in tactics but a necessity driven by the Kingdom’s economic priorities under Vision 2030.

Instability risks undermining Vision 2030 by deterring foreign investment, disrupting energy exports, and damaging Saudi Arabia’s image as a stable hub for tourism and economic innovation—core pillars of the plan and motivations behind the Kingdom’s foreign policy.

The war in Yemen remains a persistent challenge, with Houthi rebels threatening critical infrastructure in Saudi Arabia, energy exports, and maritime traffic, particularly in the critical Red Sea corridor, which hosts 15 percent of global maritime trade volume.64 Similarly, renewed uncertainty in Syria, the ongoing war in Gaza, and tensions in the West Bank risk spillover effects in border nations and within Saudi Arabia. Real and perceived insecurity jeopardizes the Kingdom’s regional comparative advantage as a stable destination for tourism and investment.

The war in Gaza has galvanized public opinion across the Muslim world, with the percentage of Saudi citizens viewing the Palestinian cause as central to Arab identity rising from 69 percent in 2022 to 95 percent in 2023.65 In response, MBS shifted from muted support for Palestinian dignity to explicitly reaffirming Saudi Arabia’s commitment to Palestinian statehood, balancing domestic pressures and regional dynamics.66,67 Given the Kingdom’s history of radicalization, MBS is also concerned with the effects of the war on his citizenry.68 Prolonged conflict or escalations, such as further annexation of Occupied Palestinian Territories, risk inflaming extremist sentiments, which could destabilize the Kingdom and threaten Vision 2030 implementation.

In recognizing the risks of over-reliance on the United States, the Kingdom has diversified its alliances. Saudi Arabia has deepened ties with China and – despite tensions – Russia to advance security and economic goals.69 China’s mediation in the Saudi-Iran détente and Saudi Arabia’s inclusion in BRICS, a group of nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) aiming to counter Western influence, highlight its multipolar strategy. Similarly, collaboration with Russia in OPEC+ (Organization of the

Petroleum Exporting Countries) reflects Saudi efforts to stabilize oil markets while reducing dependence on U.S. alignment. This pragmatic shift reflects an effort to shield itself from Western escalation with China and Russia, positioning itself as a swing power.

The incoming Trump administration inherits a region markedly different from the one it first encountered in 2017, but Saudi remains a vital player in it.

Saudi-Israeli normalization would signal a major shift in Arab-Israeli relations, offering opportunities for increased economic and diplomatic engagement and regional cooperation. While MBS has been cautious about championing Palestinian statehood in the past, domestic and regional pressures necessitate conditioning normalization efforts on a pathway for Palestinian statehood. However, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s political calculus makes such a pathway difficult in the near term.70,71 Given its vested interest in stability, Saudi Arabia will likely partner with U.S. efforts to broker a cease-fire and consider the future of governance and reconstruction in Gaza.

The United States looks to Saudi Arabia to support stabilization efforts in Lebanon, particularly in countering Hezbollah’s influence. Similarly, Saudi Arabia’s cautious approach to Yemen aligns with U.S. interests in reducing Iranian influence. Saudi Arabia is unlikely to pursue direct involvement that could provoke Houthi retaliation, even if U.S. policies shift toward renewed hostilities.72 But the United States can continue to encourage Saudi Arabia to serve as a financier and purveyor of reconstruction and development, central to any post-conflict recovery.

Former President Bashar al-Assad’s ousting in December took many by surprise.73 Saudi Arabia’s rapprochement with Iran and the Assad regime had signaled a pragmatic shift, but Syria’s future now remains uncertain. Saudi Arabia, like the rest of the world, is closely monitoring the developments in Syria and is in communication with leadership and stakeholders in the country.74 Saudi Arabia seeks to play a more active diplomatic role in shaping Syria’s post-Assad governance, leveraging its regional influence to support stabilization efforts and limit the resurgence of Iranian or extremist factions. What this – and a potential

clash between Turkish and Israeli interests in Syria – will mean for U.S. policy remains unclear, but Saudi Arabia could align with U.S. efforts to stabilize Syria, finance reconstruction, and reduce Iranian influence in the new era.75

While the Middle East’s future remains unpredictable, Saudi Arabia’s pivot toward diplomacy and conflict deescalation marks a significant evolution in its regional role, indicative of both lessons learned and geopolitical necessity. However, this nascent pivot carries the risk of reversal or inconsistency. As MBS continues to position the Kingdom as a regional stabilizer and global player, the country’s importance to both regional stability and U.S. interests cannot be overstated.

Key Takeaway: Human rights remain a critical tension in U.S.-Saudi relations and reforms under Vision 2030—such as advancements in women’s rights—are undercut by continued repression of dissent.

Human rights have become an unavoidable topic in U.S.Saudi relations, particularly in recent decades as Washington has increasingly scrutinized Riyadh’s treatment of women, political dissidents, and migrant laborers. While MBS introduced reforms expanding women’s rights and improving socioeconomic opportunities under Vision 2030, these advancements coexist with intensified repression. Ongoing concerns include the persecution of political dissidents and activists, executions for nonviolent offenses (e.g., drug-related crimes), a lack of due process in legal proceedings, inhumane treatment in the criminal justice system, alleged abuses of migrants seeking illegal entry into the Kingdom, and limited legal rights and protections for documented migrant workers under the kafala system.

Several high-profile events have underscored contradictions in Saudi Arabia’s human rights policy and their implications for the U.S.-Saudi relationship. The 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi drew global condemnation and remains a central reference point in discussions about the Kingdom’s human rights record. Meanwhile, the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen caused significant civilian casualties, sparking bipartisan concern in Washington over the U.S. role in providing arms and support.76 Harsh penalties for dissent, including multidecade prison sentences for critical tweets, reflect persistent contradictions in the Kingdom’s reform narrative.77

Saudi Arabia positions its reform agenda as evidence of modernization and improved human rights. At the January 2024 United Nations Human Rights Council review, the Kingdom cited over fifty reforms related to women’s rights in addition to strengthened protections for migrant workers and judicial modernization.78 While these measures push to bolster Saudi Arabia’s international reputation, critics argue the government’s focus on social reforms serves to deflect attention from ongoing political repression, record-level executions, continued gender-based discrimination, and restrictions on free speech.79 This calculated approach highlights the duality of Saudi Arabia’s human rights narrative: progress in areas aligned with its economic goals, coupled with continued intolerance for dissent.

To balance strategic interests with human rights concerns and public scrutiny of its partnership, U.S. policymakers should focus on actionable priorities, understanding that U.S. credibility on human rights is already weakened in the region.80 Collaborative initiatives that align with Vision 2030, such as judicial modernization, could link U.S. support to measurable improvements. Public-private partnerships leveraging U.S. businesses operating in Saudi Arabia may also help advance greater transparency and accountability. U.S. policymakers should also emphasize the importance of expanding civil liberties for the stability of the Kingdom, as political liberals could serve as a counterweight to any conservative backlash to reform efforts. Supporting Saudi Arabia’s genuine progress while encouraging further reforms is essential as the United States navigates the complexities of balancing its strategic partnership with its commitment to human rights.

Saudi Arabia’s ambitions outside of the region reflect strategic diplomacy, complex multipolarity, and soft power projection. The Kingdom aims to serve as a global peace broker, expanding its global economic influence through sovereign wealth investments, and asserting itself as a swing power by balancing influence between the United States, China, and Russia. This can be seen in Sudan, which holds a Red Sea coastline crucial for global trade and Saudi Arabia’s regional maritime security. The Kingdom co-hosted talks with the United States in Jeddah in 2023 and cohosted further talks with Switzerland in Geneva in 2024 aimed at halting the war between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces.81 Elsewhere in Africa, the PIF invests in critical infrastructure, mining, and agriculture (see section 3c. Critical Minerals).82 These investments aim to ensure food security, diversify Saudi Arabia’s supply chains, and create markets for energy exports. In Europe, Saudi Arabia mediated prisoner swaps between Russia and Ukraine and hosted diplomatic summits.83 The Kingdom’s involvement in Ukraine, in particular, demonstrates not only its desire to be a global power broker, but also its attempt to straddle both Western and non-Western spheres of influence. These actions reflect Saudi Arabia’s ambition to gain credibility and legitimacy as a reliable global actor, elevating its status as a mediator and economic partner. By projecting itself as a stabilizing force, the Kingdom not only seeks to reshape perceptions of its role in the international order but to also secure diplomatic leverage and foster economic resilience across diverse geopolitical blocs. Saudi Arabia joining BRICS further symbolizes its aspiration to diversify from over-reliance on the United States and contribute to a multipolar world.84

Authors meet with scholars at the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC).

Key takeaway: Cultural and public diplomacy remain integral to U.S.-Saudi relations, fostering people-to-people connections through educational exchanges, professional partnerships, and cultural initiatives that promote human capital development and mutual understanding.

Through the ebbs and flows of the U.S.-Saudi relationship, cultural diplomacy remained a cornerstone of the bilateral partnership. As the United States works to strengthen its partnership with Saudi Arabia—aiming to improve channels of communication and its image in a region that is, at best, hesitant and, at worst, overwhelmingly distrustful of U.S. influence—people-to-people connections are pivotal.85 These nongovernmental ties are essential for bolstering reputational security and human capital, both of which are critical to advancing broader social, energy, and technology goals. By investing in Saudi human capital—reducing unemployment, fortifying the economy, and cultivating a vibrant cultural scene—the United States not only strengthens its partner but also can push the Kingdom to align with U.S. values. This in turn contributes to regional stability and advances U.S. foreign policy objectives.

Educational exchanges between Saudi Arabia and the United States fostered a generation of leaders whose influence extends to the highest levels of the Saudi government, with U.S.-educated officials occupying key roles, such as the Foreign Minister and Ambassador to the United States.86,87 Over 700,000 Saudis have studied in the United States, and while the number of Saudi students studying in the United States has fallen in recent years as the Kingdom prioritizes sending students to only the top U.S. universities, thousands continue to do so and go on to fill prominent government positions.88,89 Programs like Fulbright are also expanding to deepen bilateral ties, with plans to increase the number of U.S. students conducting research in Saudi Arabia in the coming years.90 Saudi Arabia’s reputation as a stable and safe destination for linguistic and cultural exchanges positions it as an increasingly attractive alternative to regional competitors. Yet, public diplomacy through exchanges faces challenges. While Saudi Arabia launched programs to increase reciprocal exchanges, U.S. students remain hesitant to study long-term in the Kingdom, often opting for shorter

visits or semester-long programs due in part to the relative newness of these opportunities. Additionally, stagnant funding for U.S.-based exchange programs, such as the State Department’s International Visitor Leadership Program, limits their potential. Capacity-building goals in newer sectors like tourism and cultural industries may also outpace Saudi institutional readiness, creating a gap in achieving Vision 2030 objectives.

Given these challenges, the United States should seek mutually beneficial partnerships that combine Saudi funding with U.S. institutional expertise. Examples include collaborations between vocational schools and Saudi educational institutions, training programs for college counselors, and projects focused on cultural diplomacy, such as arts-focused initiatives at institutions like the Kennedy Center.91 Expanding university partnerships, similar to Arizona State University’s new campus in Saudi Arabia, could also further educational and professional exchanges.92

Saudi Arabia’s decision to open the country to expand its tourism and entertainment sectors offers areas for increased cultural exchange. The ensuing cultural reform efforts (e.g., lifting the ban on cinemas, reducing gender segregation in restaurants) reflect the Kingdom’s broader goals of transforming its society, in part aligning more closely with Western cultural norms.93 Additionally, major investments into high-profile events like the 2022 debut of LIV Golf and the Kingdom’s successful bid to host the 2034 FIFA Men’s World Cup position Saudi Arabia to attract a greater international audience.94 However, these reforms and investments are not without controversy. Accusations of “sportswashing” and questions about the financial, environmental, and social stability of these investments raise concerns among investors, foreign partners, and human rights groups.95,96 Despite these challenges, Saudi Arabia’s interest in these sectors offers new avenues for cultural exchange and opportunities for the United States to engage in diplomatic efforts that support stable and sustainable change in Saudi Arabia.

Vision 2030 highlights sports—from soccer teams to individual exercise—as a cornerstone of physical and societal health, offering significant opportunities for U.S.-Saudi sports diplomacy. Programs like the State Department’s Global Sports Mentoring Program, in partnership with ESPN, can empower Saudi women in sports while fostering cross-cultural connections.97

Unlike larger-scale sporting investments criticized as sportswashing, these initiatives focus on youth engagement and capacity building, emphasizing tangible, long-term impact.

Esports have also garnered popularity in the Kingdom in recent years, with an estimated 67 percent of its population involved in gaming in some capacity.98 The sector is projected to contribute over $13 billion to the economy by 2030.99 Gaming is an effective channel for cultural diplomacy with the potential to reach a large swath of the Saudi youth population who may otherwise not engage with a U.S. audience. A new State Department initiative or partnerships between U.S. and Saudi enterprises in gaming could utilize U.S. industry know-how and extend the impact of cultural diplomacy into this growing field.

Congressional Delegations, or CODELs, inform the legislative process through hands-on experience interacting with international policymakers, business owners, and students.100 By engaging directly with Saudi business leaders, youth, and government officials, these visits can demonstrate U.S. commitment to the bilateral relationship while building familiarity with the opportunities for collaboration. Such efforts may mitigate reputational concerns and outdated perceptions. They may also equip U.S. policymakers with nuanced insights to inform legislation and collaboration in the bilateral relationship across strategic sectors.

Saudi Arabia remains a critical U.S. partner, but its evolving foreign policy under MBS introduces both opportunities and challenges. The Kingdom’s relatively recent assertive interventions, growing ties with China and others, and its ambitious Vision 2030 agenda reflect a dual pursuit of regional integration and global influence. While tensions over human rights and shifting partnerships complicate the bilateral relationship, Saudi Arabia’s efforts to diversify its economy, stabilize the region, and reform domestic structures align with key U.S. strategic interests. Recent setbacks, such as the stalled U.S.-Saudi-Israel “megadeal,” highlight regional volatility but also underline the need for sustained, adaptable engagement. The United States should prioritize strengthening its partnership with Saudi Arabia through public diplomacy, capacity building, and strategic collaboration, leveraging shared goals to promote regional stability and mutual growth in an increasingly multipolar world.

Leverage Saudi Arabia’s Strategic Interests to Advance U.S. Goals: If the next administration chooses to pursue a U.S.-Saudi-Israel megadeal, the United States should leverage Saudi strategic priorities to advance human rights, such as through judicial reform and promoting civil liberties, and establish limits on Chinese involvement in critical sectors to protect U.S. national security interests.

Cooperate on Regional Stabilization and Reconstruction Efforts: The United States should cooperate with Saudi Arabia on regional stabilization by supporting diplomatic efforts to de-escalate conflicts, financing post-conflict reconstruction, and promoting greater regional integration.

Prioritize Human Capacity Building: U.S. public diplomacy in Saudi Arabia should prioritize human capacity building by expanding two-way exchange programs, fostering vocational and higher education partnerships, and promoting sports initiatives that enhance mutual understanding and economic development.

While Vision 2030 provides a robust framework to diversify Saudi Arabia’s economy from its primary dependence on oil, energy in many forms, including oil, will continue to be critical to Saudi Arabia’s economic and geopolitical goals. Oil will continue to be a key export, while growing investment in clean energy sources hedges against a future decline in oil demand. Renewable energy sources such as wind and solar hold strong potential in Saudi Arabia, particularly for domestic grid decarbonization, but progress has been slow. The Kingdom is also interested in pursuing traditional nuclear energy, but has yet to sign a nuclear agreement with the United States. Finally, clean hydrogen has the potential to become a valuable export, contingent upon global demand. Each of these energy sectors are relevant to U.S. geopolitical and economic interests given the Kingdom’s influence in energy markets.

Key takeaway: Oil will remain a key export of Saudi Arabia for at least the next two decades, with the Kingdom’s low-cost production, vast reserves, and political leadership of OPEC giving it significant market power. However, U.S. shale production is challenging the Kingdom’s role as a swing producer in the oil market.

Oil, the original cornerstone of the U.S.-Saudi bilateral relationship, propelled the Kingdom’s growth and supported its citizens since it was first discovered in Dammam in 1938.101 Saudi Arabia’s low cost of oil production has resulted in enormous profits from oil sales and left it well-positioned to drill so long as there is demand for oil.102 The global economy will likely depend on oil through 2050, and Saudi Arabia’s oil market remains the foundation of the country’s fiscal health and economic strategy. Riyadh aims to leverage its cheap production capabilities to support reliable and promising revenue streams in petrochemical and EV manufacturing.103,104 In preparation of a future decline in oil demand, there are opportunities for the U.S. government and private sector to work with Saudi Arabia on innovative early stage frameworks, like the circular carbon economy.

Saudi Arabia is the world’s second largest oil producer behind only the United States, and considered to be the most powerful player in the oil market through its defacto leadership of OPEC.105 OPEC produces 40 percent of global oil supply, and Saudi Arabia is the highest capacity producer.106 These endowments make it a swing producer, allowing it to heavily influence the price of oil in the global market.107 In addition to vast reserves, Saudi Arabia produces oil more cheaply than anyone else, at an estimated $3-10 per barrel, giving Saudi Arabia significant leverage over the international oil market (for comparison, U.S. shale oil averages a $45 per barrel breakeven price).108,109 While OPEC’s mavrket share has declined, preventing it from imposing an embargo as it did against the United States in 1973, it can still impact economies by increasing or curtailing production. In general, Saudi Arabia carefully manages its production to ensure prices remain high enough to fund its budget without depressing global demand.110 As the influential swing producer, Saudi Arabia historically has curtailed production far more than other OPEC members to deter defection.111

The rapid rise of U.S. shale oil is challenging OPEC, and thus Saudi Arabia’s role as the swing producer in the oil market, straining the bilateral relationship.112,113 President-elect Trump has pledged to facilitate boosting U.S. shale oil production, with federal officials projecting U.S. outputs are on track to average 13.5 million barrels a day (mb/d), nearly 50 percent higher than Saudi Arabia’s October 2024 output.114 However, ramping up U.S. shale production to these levels will not be a simple endeavor, given private U.S. shale firms profit incentives to drill less unless prices spike.115 Both Saudi Arabia and the United States face relative unknowns regarding the other’s intentions in oil production, complicated by divergent political and private sector interests, creating a risk for future fissures in the bilateral relationship given the importance of the global oil market.116,117

The medium-term outlook for oil demand will impact Saudi Arabia’s fiscal position and its capacity to achieve the goals laid out by Vision 2030. However, industry analysts disagree on demand projections. OPEC projects rising global oil demand until 2050, while the International Energy Agency projects demand peaking in 2030. Others predict a peak occurring sometime between 2030 and 2035.118,119,120,121 There is uncertainty in oil demand projections because of (1) economic growth in China, which heavily relies on Saudi crude, and in other emerging markets, (2) the effectiveness of fuel economy standards, and (3) the global uptake of electric vehicles (EVs), among others.122,123 The Energy Information Agency’s short-term outlook projects that, along current trends, the Brent crude oil spot price will remain stable around $74 a barrel through 2025.124

Regardless of differing projections for global demand, Saudi Arabia is also leveraging its cheap oil production capacity to spur growth in its petrochemical and manufacturing industries. Saudi Arabia’s cheap oil positions petrochemicals as Saudi Arabia’s most competitive manufacturing industry. Even as global oil demand levels out, Saudi Arabia aims to grow its petrochemical and derivative plastics manufacturing, which will provide a modest domestic demand for its oil reserves. If the Kingdom can entice private investment in the industry, they can more feasibly ease historically high domestic subsidies on oil to stimulate revenue.

Expanding into other manufacturing sectors will require intense process heat that renewable resources struggle to provide.125 Therefore, Saudi Arabia may require other

types of energy including nuclear, hydrogen, geothermal and solar concentrate to support manufacturing heat requirements. Hydrogen is most promising for petrochemicals, but will require plants to switch furnace technologies.126,127,128 In the interim, manufacturing processes will demand crude as a source of process heat.

The United States can advance its climate mitigation goals by expanding efforts to improve Saudi Arabia’s carbon capture and storage (CCS) and direct air capture technologies to limit emissions associated with oil production and oil-intensive manufacturing. The Kingdom aims to use oil in a more sustainable way to encourage greater FDI inflows by implementing its Circular Carbon Economy (CCE) framework.129 This framework will reduce, recycle, reuse, and remove carbon to create a closed loop system for carbon usage. Examples of more sustainable oil use include creating more efficient and less energy-intensive production processes and improving carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies. However, expensive capital, lagging CCS and direct air capture (DAC) technologies, and carbon leak risks have hindered its efforts so far.130,131 To mitigate these challenges, in 2024, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) signed three memorandums of understanding (MOUs) between Aramco and American companies on joint technology testing of DAC and heat batteries.132 The U.S. should continue to partner with the Kingdom on CCS research and development, aligning U.S. interests in climate mitigation with Saudi priorities for sustainable hydrocarbon use.

Key takeaway: Saudi Arabia has ambitious plans to decarbonize its domestic electricity production through renewable energy sources, notably solar, wind, and geothermal, however this implementation is occurring slowly. China maintains a strong advantage in solar energy partnerships, but less so in geothermal and biofuels.

Renewable energy is increasingly important to the energy diplomacy of both the United States and Saudi Arabia. In 2024, representatives from the U.S. DOE met with Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Energy to build on the Partnership Framework for Advancing Clean Energy, first announced as part of the Jeddah Communique in 2022.133 The roadmap for cooperation included knowledge exchange, regulatory reform, joint research and development, and human capital expansion.

Saudi Arabia has continuously revised its renewable energy goals, including solar, wind, and geothermal, since the release of Vision 2030. The initial target of 9.5 GW has now risen to 130 GW, and the country aims to source at least 50 percent of power from renewables by 2030. Renewable deployment aligns with both domestic diversification efforts and international climate priorities. Despite this, the Kingdom has yet to successfully deploy renewables at scale, with renewable energy currently accounting for less than one percent of the country’s electricity generation.134

Saudi Arabia’s natural endowment extends beyond oil and gas to a prime location along the world’s sun belt.135 According to the World Bank, Saudi Arabia has some of the highest practical photovoltaic potential in the world.136 There are also high wind speeds and promising capacity factors across several regions, with onshore potential as high as 200 GW.137 While the Kingdom has high ambitions for solar and wind energy, from powering giga-projects to scaling green hydrogen, the pace of investment is advancing slowly.138

Challenges to the expansion of renewable energy include workforce development lags, limited incentives for decentralized household production, and continued regulatory angst.139,140 The government has made strides to encourage investment, like implementing competitive procurement procedures, but these efforts have yet to yield major changes in the energy mix.141 The 400MW Dumat Al-Jandal project is the Kingdom’s only utility-scale wind farm in operation to-date.142 However, several large wind projects are in the planning phase, including the country’s first offshore farm.143 As grid and storage technology advance, more capacity may come online.

Saudi Arabia is investing not only in installation, but across the renewable energy supply chain. The PIF recently announced intentions to localize 75 percent of the production of the components in renewable projects by 2030.144 This increasing localization aligns with the country’s aspirations to bolster manufacturing and export renewable energy to other countries in the region.145 However, economic collaborations go beyond regional energy pacts; many of the manufacturing projects being announced are in cooperation with Chinese firms, as exemplified by Chinese Energy Engineering signing a nearly $1 billion contract to build a solar plant in the Kingdom.146,147 This signals an important trade expansion between the two countries and reflects the continued global dominance of China in solar energy.148,149 If the United States seeks to bolster clean-energy partnerships outside of

China, U.S. policymakers may consider fostering similar partnerships with Saudi Arabia.150 However, U.S. industry may struggle to compete against China’s dominance in solar technology exports and therefore should focus on areas in which the United States is more competitive, like geothermal energy.

The United States, a leader in geothermal installation, should provide technical assistance and pursue partnerships with Saudi firms to support geothermal expansion in Saudi Arabia, which would contribute to Saudi Arabia’s renewable goals.151 Unlike wind and solar, geothermal provides a reliable base load source of energy with a relatively small surface footprint. However, commercial scale expansion is limited by the relatively high costs of geothermal investment. American companies could also pursue partnerships such as the one between TAQA and Iceland’s Reykjavik Geothermal, aimed at initiating geothermal projects of up to 1GW.152

Biofuel technology is another area for potential collaboration between the United States and Saudi Arabia. The Kingdom’s only biofuel producer, the Biofuel Company, announced plans to triple refining capacity to 36 million liters, opening new sites in Jeddah and Riyadh.153 The biofuel industry is expected to grow further as the International Maritime Organization transforms global shipping standards, with biofuel as a “green” shipping fuel.154

Significantly scaling renewable electricity in Saudi Arabia will require substantial investments in new T&D infrastructure, because wind and solar assets will not be co-located with existing infrastructure which was designed to transport electricity generated with oil. New infrastructure requirements will be even greater if Saudi Arabia wishes to export renewable energy to its neighbors via high-voltage interconnectors, like the proposed EgyptSaudi project.155 American companies could stand to play a role in these expansions.

Key takeaway: Saudi Arabia is actively pursuing civilian nuclear energy to decarbonize its electricity grid, but has not yet selected a vendor. U.S. policymakers face a critical decision on whether to engage Saudi Arabia’s civilian nuclear ambitions, balancing nonproliferation risks against strategic concerns of losing influence to competitors like China and Russia.

Beginning in 2010 with a royal decree, Saudi Arabia began developing a civilian nuclear energy program to diversify its energy mix and as a key source of zero-emissions electricity, in cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).156 The Kingdom has expressed interest in acquiring nuclear energy technology from the United States, a critical point in negotiations over a potential U.S.Saudi-Israel deal. However, the United States has remained hesitant to formalize nuclear technology cooperation via a “123 Agreement” due to a lack of Saudi commitment to forswear domestic uranium enrichment and reprocessing rights, pillars of U.S. nonproliferation standards.157 Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia has engaged with other countries, including South Korea, China, and Russia, to advance its nuclear ambitions, raising questions about the strategic implications of U.S. disengagement and who would fill this role.158

As the Kingdom makes slow, but steady progress toward realizing its nuclear energy goals, an incoming U.S. administration will face pivotal decisions about the level and nature of support, if any, to extend to an imminent Saudi nuclear energy program.

Nuclear energy is the process of inducing fission in uranium atoms to generate energy, which then heats a reactor’s cooling agent to produce steam, spin turbines, and generate low-carbon electricity.159 While nuclear energy provides approximately nine percent of the world’s total electricity, it is nearly 25 percent of the world’s low-carbon electricity.160 After COP29 in 2024, more than 30 countries pledged to triple their nuclear energy capacity by 2050 to reach global decarbonization targets, both through the adoption of small modular reactors (SMRs) and traditional large reactor nuclear power plants (NPP).161 Civilian nuclear energy programs can be challenging due to extremely high up-front capital costs, licensing and regulation approvals, long lead times and construction delays, high operating costs, and safety and security concerns.162 Furthermore, nuclear commerce is a highly geopolitical endeavor, a multi-decade process that

generally strengthens ties between the supplier and the host state.163

With growing energy demands, Saudi Arabia has demonstrated continued interest in diversifying its energy mix through the adoption of a civilian nuclear energy program. Currently, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is the only country in the Middle East with a civilian nuclear energy program, with a capacity of 5600 MW or 25 percent of the UAE’s current electricity needs, at the Barakah NPP.164 While the UAE worked with South Korea to build the reactors, the United States also provided technical consultations, given the 123 Agreement in place. Elsewhere in the region, Egypt and Turkey both have MOUs with Russia’s Rosatom for traditional reactors.165

In 2017, the Saudi government began a formal bidding process with potential international companies for reactor construction, however, it extended the formal bidding process several times. Until now, technical bids have been invited from China’s National Nuclear Corporation of China, France’s Électricité de France, Russia’s Rosatom, and Korea’s Korea Electric Power Corporation. Westinghouse, a leading U.S. company, was excluded from the bidding process largely due to the lack of a bilateral nuclear cooperation agreement in place between the United States and Saudi Arabia.166

In 2023, the Kingdom reiterated its plans to develop “peaceful uses for nuclear energy across various fields,” including building a NPP to help meet sustainable development requirements as outlined in Vision 2030.167 Working with the IAEA, the Kingdom is progressing on implementing a full Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement (CSA), as required by all non-nuclear weapons states party to the nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT).168 The Kingdom recently transitioned from the Small Quantities Protocol to a CSA, signaling the Kingdom’s continued commitment to transparently advancing nuclear energy ambitions.

Saudi Arabia consistently expresses interest in acquiring nuclear energy technology and expertise from the United States. However, the Kingdom has also been forthcoming about its interest in pursuing a full-fuel cycle, meaning the production, enrichment, and reprocessing of uranium. As recently as January 2023, the Saudi Energy Minister stated that the Kingdom intends to use its domestic uranium resources for producing low enriched uranium (LEU).169

Domestic enrichment and reprocessing is not compliant with the United States’ “gold standard” of nonproliferation norms, which has contributed to the lack of a mutually agreeable U.S.-Saudi civil nuclear cooperation agreement, as required by section 123 of the 1954 Atomic Energy Act. The United States has reportedly considered a U.S.run uranium enrichment operation in Saudi Arabia as a middle ground, or a delayed decision (such as a tenyear moratorium) on domestic enrichment, with others critiquing this as deferring action.170

While Saudi Arabia is party to the NPT and therefore legally bound to not pursue nuclear weapons, in 2018 the government stated that if Iran were to obtain a nuclear weapon, the Kingdom would “follow suit as soon as possible.”171 This clearly stated risk presents a challenge to the United States, as it decides what level of support to lend to the Kingdom’s nuclear energy ambitions. Some experts emphasize the need for continued technical and strategic involvement to limit enrichment and reprocessing risks, arguing that decoupling could strengthen Saudi Arabia’s ties with strategic competitors and reduce U.S. leverage, while others believe the risk of abandoning nonproliferation standards far outweighs any strategic gains.172,173,174

Balancing geopolitical, nonproliferation, and economic considerations, a civilian nuclear deal could also help revitalize a slowing U.S. nuclear industry. Nuclear energy will remain important for U.S. policymakers to consider as the United States seeks to lead in future SMR exports, in addition to large reactors. These decisions will carry far-reaching implications for regional security, nonproliferation norms, and the evolving geopolitical landscape.

Key takeaway: Saudi Arabia has a competitive edge in low-carbon hydrogen production, which positions it as both a potential strategic partner and rival to the United States in global hydrogen markets. However, the future of global demand for hydrogen remains uncertain.

The use of hydrogen in industry has been widespread with demand in 2023 at 97 million tons per annum. Today, the most common uses of hydrogen are in refining (i.e., reducing the sulfur content of fuels) and chemical production (e.g. ammonia).175 Approximately 80 percent of global hydrogen is produced onsite, rather than traded.176 Saudi Arabia is already a major producer and consumer of

hydrogen given the presence of large refineries and some ammonia production in the country.177

Low-carbon hydrogen technologies have a potentially large role to play in the global energy transition. There are three techniques for the low-carbon production of hydrogen: “green” hydrogen, produced via the electrolysis of water and powered by renewable energy; “pink” hydrogen, using the same technology but with a nuclear energy source; and “blue” hydrogen, using traditional steam methane reformation but in conjunction with CCUS. Initial projections forecast that hydrogen could extend beyond traditional uses, including as a source of process heat in industry, as a fuel source for light and heavy vehicles, and as a way to “firm” electrical grids.178

Despite the potential, expectations for the global hydrogen market have fallen in recent years. For instance, McKinsey’s latest analysis suggested hydrogen demand in 2050 to be 10-25 percent lower than anticipated the year prior, due to decreased expectations for use in home heating, light vehicle transportation, and air fuels.179 Lowcarbon hydrogen is now assessed as unlikely to become a dominant energy source in any use cases in which it is not already dominant (i.e., refining and chemical production), though it could still become a significant energy source for other use cases such as shipping and jet fuels, steel production, long-duration energy storage and as a synthetic chemical feedstock.180

Despite uncertainties in demand, hydrogen is a major pillar of Saudi Arabia’s low-carbon industrial strategy, with the Kingdom placing significant focus on the production of low-carbon hydrogen. The planned green hydrogen plant at NEOM promises to be the largest in the world, and the Kingdom has expressed an ambition to obtain 15 percent of world production of blue hydrogen.181,182

Production costs for low-carbon hydrogen in Saudi Arabia are likely to be low, given its comparative advantage in renewable energy resources. The Kingdom’s abundant renewable resources described above (electricity makes up approximately 40-50 percent of levelized cost) mean that production of green hydrogen in the Kingdom is currently estimated at $2.16/kg of hydrogen, rendering it highly competitive.183 For comparison, the cheapest zero-carbon technology in the United States is currently estimated at $3.07-$3.86/kg, though Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) subsidies could take this below

the cost of Saudi Arabia’s production.184 The Kingdom’s abundant natural gas resources and existing capability for producing “gray” hydrogen (traditional carbon-intensive production that releases carbon dioxide) could also enable it to produce very cheap blue hydrogen by adding CCUS facilities to existing plants. Infrastructure will also help, as extensive gas export terminals near the Strait of Hormuz and the proposed megaplant at NEOM mean that Saudi Arabia may either already have suitable infrastructure, or the expertise to be able to construct it more easily than competitors. This helps position the Kingdom to remain as a strategic energy exporter should oil demand decrease.

While Saudi Arabia has a comparative advantage in hydrogen production, it also faces significant competition in a global market, including from the United States. Many countries have set out roadmaps for national hydrogen production strategies.185 Global demand for traded hydrogen is anticipated to be highest in Europe and East Asia, potential areas of export. Within the region, the UAE, Morocco, and Egypt have all announced plans for large-scale hydrogen production, relying on similar potential strengths as Saudi Arabia.186 The locations of Egypt and Morocco, closer to key customers in Europe, may make Saudi Arabia less competitive in the European market. Similarly, hydrogen production has become an energy transition priority for the United States, where a $3/kg tax credit for the lowest-carbon production was established under the IRA.187

While U.S. companies might benefit from investments in the hydrogen sector in Saudi Arabia, the Kingdom also represents a competitive threat to U.S. production. A key objective of the IRA is to incentivize domestic hydrogen production through a subsidized reduction in the cost of production in the United States. As a result, Saudi Arabia and the United States may compete for the same international customers. In 2023, Saudi Arabia completed eight successful trade pilots, of which six involved transport to Asia.188 This is an early indicator that trade with Asia may be seen as a more viable hydrogen strategy for the Kingdom. However, policymakers should bear in mind that a greater number of successful hydrogen projects in Saudi Arabia could mean fewer projects, and therefore fewer jobs, in the United States.

Despite U.S. oil production sharply increasing in recent decades, Saudi Arabia’s vast oil reserves and influence on the global market mean that oil remains central to the U.S.-Saudi relationship. Furthermore, the broader world of energy is also in the process of a profound transformation, requiring robust partnerships between countries and industries. The next four years are likely to bring instability in world oil prices, as Trump administration policies and OPEC production plans clash, coupled with uncertainties in electric vehicle demand. Engagement with Saudi Arabia and OPEC could allow the United States to exert greater influence on world oil markets in this context. Similarly, the United States and Saudi Arabia may become competitors in the emerging global hydrogen market—active engagement on this topic could avoid a situation where Saudi Arabia’s production undercuts American jobs. At the same time, low-carbon energy technologies present opportunities for American

businesses to launch new ventures inside the Kingdom. Given the current lack of U.S. exports, renewable energy supply chains are unlikely to include U.S. companies unless the administration makes this a priority. Nuclear energy remains an important area of future cooperation due to the potential export of U.S. SMR technology, regardless of Saudi Arabia’s vendor selection for its traditional reactor build. Should the United States be able to secure commitments from the Kingdom, such deals could be worth billions of dollars to U.S. companies, as well as contribute to bolstering energy security.

Utilize Energy Dialogues for Oil Diplomacy: Saudi policymakers are likely to react negatively to proposed administration policies to encourage higher oil production in the United States. It is critical that U.S. policymakers utilize existing bilateral and multilateral energy dialogues to discuss policy changes, as ignoring the reaction could lead to negative spillover into other areas of U.S.Saudi cooperation.

Invest in Joint Research on Carbon Capture and Storage Technologies: Continue facilitating partnerships between governments, academic institutions, and private businesses to drive innovation in direct air capture, carbon capture and underground storage, and improving next-generation battery technology. Improving these technologies aligns with Saudi priorities on clean hydrocarbon use and U.S. emissions reduction goals, offering mutual environmental benefits.

Encourage Commercial Partnership in Gas and Renewable Energy: U.S. policymakers should facilitate partnerships with U.S. businesses in Saudi Arabia where feasible. Areas where U.S. businesses have strong experience – such as gas supply chains, geothermal energy and T&D infrastructure – should be prioritized. Renewable energy projects and supply chains, though more of a stretch due to China’s sectoral dominance, could also be an ambition.

Continue to Negotiate a Civil Nuclear 123 Agreement: U.S. policymakers should continue to negotiate a civil nuclear energy “123 Agreement” that upholds safety, security, and nonproliferation norms. In turn, the U.S. nuclear industry could provide technical and regulatory assistance to the Kingdom.

Saudi Arabia is emerging as a global hub for innovation and technology, driven by Vision 2030’s ambitious goal of increasing the technology sector’s contribution to GDP from one to five percent.189 The Kingdom’s growing technology sector and substantial investments in artificial intelligence and critical mineral supply chains demonstrate its commitment to diversifying beyond traditional revenue streams.190 Against the backdrop of great power competition between the United States and China, Saudi Arabia’s collaborations with both countries highlight the opportunity for the United States to strengthen bilateral cooperation with the Kingdom and curb malign foreign influence in emerging technology sectors.191

Key Takeaway: By focusing on artificial intelligence, data centers, and semiconductors, Saudi Arabia seeks to position itself as a regional technology powerhouse that is willing to hedge between the U.S. and China. While economically beneficial, these technologies could also facilitate increased digital authoritarianism in the Kingdom.

Saudi Arabia is heavily investing in artificial intelligence (AI) and large-scale data centers, which are projected to contribute over $135.2 billion to the Saudi economy by 2030, supporting its ambition to become a global technology hub. Recently, the Kingdom announced a $100 billion initiative called Project Transcendence, aimed at establishing itself in AI, data analytics, and advanced technology.192,193 Saudi Arabia, while keen on hosting data centers for international technology companies, aims to also develop new technologies, Arabic-language AI models, and ultimately export developed AI technology. AI and high-end semiconductor chips are at the heart of the U.S.-China technology competition, and will likely be a main area of focus for the incoming Trump administration. U.S. policy should aim to minimize the risks posed by geopolitical tensions, communicate export control decisions, and align technical standards, encouraging Saudi Arabia to prioritize collaboration with the United States over China, given the Kingdom’s current incentives to engage with both.

Saudi Arabia is well-positioned to host large data centers for technology companies interested in taking advantage of the Kingdom’s spacious land, affordable and reliable energy, and desire to become a bigger player in advanced technology. Data centers are a critical infrastructure underpinning much of today’s digital economy, as they host private cloud applications for businesses, process big data and power machine learning and AI, support high-volume eCommerce platforms, and more.194 Data centers require consistent and reliable power, cooling infrastructure, and additional designs based on their intended use.

Domestic demand is also rising as Saudi Arabia advances into high-tech industries such as EVs, helicopters, and drones, which require significant numbers of semiconductors.195 Saudi Arabia has launched a National

Semiconductor Hub to attract international chipmakers, with the goal of 50 semiconductor design companies setting up business in the Kingdom by 2030.196

Saudi Arabia will need to build partnerships with leading technology companies to advance in AI, rather than relying solely on indigenous development, given current skilled labor constraints. Towards this goal, in October 2024, Google and the PIF announced a strategic partnership to establish a new AI hub in Saudi Arabia.197 The partnership aims to bolster the Kingdom’s information and communication technology sector (ICT) by 50 percent and develop a skilled AI workforce including students and professionals. Joint research will focus on Arabic language models and AI applications. Experts estimate the new AI hub could contribute over $70 billion to the Kingdom’s GDP over the next eight years.198

The Google-PIF deal also emphasizes and prioritizes upskilling the local workforce. One stated goal is to train 5,000 engineers in chip design by 2030.199 The strong emphasis on workforce development signals the Kingdom’s determined push to invest in the groundwork and talent needed to become a key player in what could turn into an AI cluster in the Middle East, and subsequently compete with the UAE to become the region’s technology superpower.200,201,202 The partnership also recognizes the energy advantages in the region, attracting not just Google, but other large technology companies such as Microsoft, Nvidia, and Amazon.

While the Google-PIF partnership is significant in scope, it differs substantially from the G42-Microsoft deal with the UAE. The deal does not transfer model weights, which govern how models behave, or co-create non-commercially available AI technology, nor does it involve proprietary transfers.203,204 These limitations signal leading U.S. technology companies are taking cautious steps forward as the U.S.-Saudi bilateral relationship expands beyond energy to emerging technologies. Given the national security implications of AI, data centers, and semiconductor chips, U.S. companies will closely follow rapidly changing export controls and foreign investment reviews related to the hardware and software underpinning AI.

There was once a belief, accelerated by the early months of the Arab Spring, that technology could play a role in democratization and greater connectivity would

weaken authoritarian control over populations through information sharing, organizing, and limiting capacity for repression and control.205 Instead, a new area of digital authoritarianism has emerged in the form of facial recognition systems, disinformation campaigns, advanced biometrics, civilian surveillance, and suppression of dissenting voices on social media.