3 minute read

The Bellicose Nature of Natália Correia

Victor Rui Dores

Translated

Advertisement

by

Katharine F. Baker

more spacious. But almost fifty years on, what I still recall is the bar’s thick haze. Everyone there was smoking: politicians, members of the military, journalists, people in the arts and letters. I recall my waiter Bandola’s friendliness, the tables, chairs, tall bar, red upholstery, engravings on the walls, upright piano along the right-hand wall – and, dotting the open space, the small bust of La Poésie on a high pedestal.

It was courtesy of Carlos Alberto Moniz’s helping hand that I crossed the threshold of the Botequim, conceived and founded by writer Natália Correia (1923-93), for the first time one rainy night in November 1978. Back then, her salon-bar located on Largo da Graça was a nerve center for Lisboan cultural gatherings and political conspiring.

A recent arrival in Lisbon, dazzled by the capital’s magnificence, I was a student in the University of Lisbon’s School of Humanities, leading a life full of new hopes for my future. I took pride in having published my first book of poetry a year before – Poemas de Fogo e Mar [Poems of Fire and the Sea], the upshot of an emotional and romantic crisis that had scarred my adolescence on Terceira. So that night I secretly tucked a copy of the book in my overcoat pocket to offer to “Dona Natália,” this force of nature and veritable living legend.

My first impression of her Botequim was rather disappointing, because frankly I assumed it would be

Natália had turned the Botequim into her personal salon. It was there that she kept appointments with friends and acquaintances. Natália was said to be unsubmissive and insubordinate, egocentric and exuberant, argumentative and contradictory. It was also widely known that, being fond of the sensual and spiritual, she exuded freedom, daring, passion, culture and justice – she who had been the most censored author in Portugal during the dictatorship.

Wearing eye-catching scarves, with her ever-present cigarette holder and almost always a glass of whisky in her hand, Natália reveled in being the center of everyone’s attention, circulating from table to table to crack jokes and hurl criticisms and provocations at her select clientèle. And the writer was indeed selective, keeping her bar’s door shut, thus obliging anyone who wanted to enter to ring the doorbell. And the truth is that only those she wanted to admit got in.

By this point I already appreciated Natália Correia’s poetry. An islander torn from his island, I was discovering my own Azoreanness through Natálian verses:

“Não sou daqui, mamei em peitos oceânicos

Minha mãe era ninfa, meu pai chuva de lava

Mestiça de onda e de enxofres vulcânicos

Sou de mim mesma pomba húmida e brava”.

[I’m not from here, I nursed on ocean breasts.

My mother was a nymph, my father a downpour of lava.

A mix of waves and volcanic sulfur, I myself am a wet, angry dove.]

That night our hostess spotted Carlos Alberto Moniz as he entered the Botequim with me in tow. And because another Azorean, Duarte Brás, was already seated at one of the tables, she promptly announced with expressive sweeping gestures, “Well now, this is going to be a night for us to sing the Lira and Samacaio!”

A round of applause from the crowd.

Natália, who was always posing and posturing, approached me, disdainfully inspected me from head to toe, and after blowing a puff of smoke in my face asked Carlos, “So, whom have we here today?”

“An Azorean from Graciosa, a university student,” my friend answered.

I nervously introduced myself, and offered my little book to the great poet shyly.

Natália opened the book, flipped perfunctorily through it, read the dedication, and with a sarcastic smile on her face asked me, “How old are you, lad?”

“Going on 21,” I replied fearfully.

Then Natália at her haughtiest retorted in her dramatic booming voice, “Not much can be hoped for when you’re at the age of poetic masturbation.

And upon saying this, she returned my book and conspicuously turned her back to me as she left.

Standing there with book in hand, I swallowed hard, and according to Carlos I turned redder than a beet.

Perceiving my embarrassment, Natália increased her pace, turned back and, placing her right hand on my left shoulder, said to me with undisguised coquetry, “But continue writing. Continue writing, you’ll get there.”

Then she surreptitiously took the book from my hand, and carried it off with her as she headed for the bar.

“You’re lucky, she kept your book,” Carlos whispered in my ear.

I spent the rest of the night feeling sorry and sad for myself. Only after downing two whiskies did I muster enough courage to sing the Lira and Samacaio, chiming in with Natália, Carlos and Duarte.

Originally published as “Da natureza belicosa de Natália Correia”: https://portuguesetimes. com/admin/archive/ Edi%C3%A7%C3%A3o%202737%20 -%2006%20de%20dezembro%20 de%202023.pdf (p. 24)

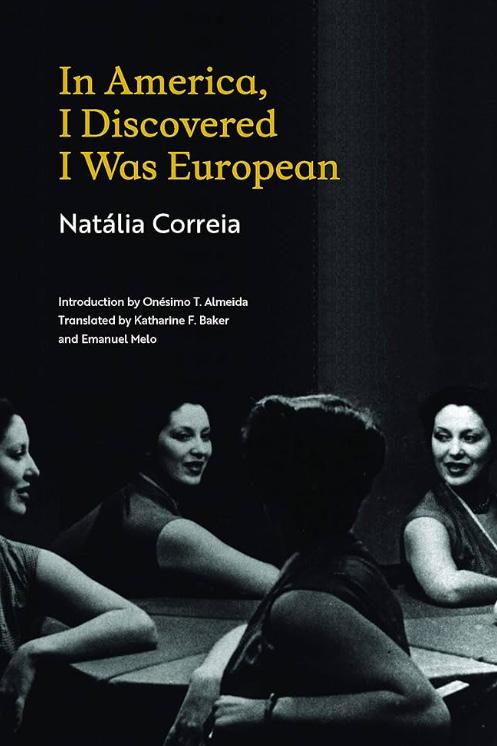

Editor’s note: Katharine F. Baker and Emanuel Melo have translated Natália Correia’s travelog of her first trip to the United States at in 1950 age 26, Descobri Que Era Europeia, being published by Tagus Press as In America, I Discovered I Was European.