Discussion Series

Join us for a Script Club with the Portland Public Library. Check out your copy of the script and join us two weeks before opening of each Mainstage Production. Scripts are available at the reference desk at the Main Branch of the Portland Public Library. This year discussions will be held in the Rines Room at 1:30pm two weeks before a show opens. Feel free to come and chat about the plays with Literary Manager, Todd Brian Backus; his Directing and Dramaturgy Apprentices, and special guests. Visit portlandlibrary.com/programs-events/ for more information.

The Artistic Perspective, hosted by Artistic Director Anita Stewart, is an opportunity for audience members to delve deeper into the themes of the show through conversation with special guests. A different scholar, visiting artist, playwright, or other expert will join the discussion each time. The Artistic Perspective discussions are held after the first Sunday matinee performance.

Curtain Call discussions offer a rare opportunity for audience members to talk about the production with the performers. Through this forum, the audience and cast explore topics that range from the process of rehearsing and producing the text to character development to issues raised by the work Curtain Call discussions are held after the second Sunday matinee performance.

All discussions are free and open to the public. Show attendance is not required. To subscribe to a discussion series performance, please call the Box Office at 207.774.0465.

Dramaturg Kimmarie mccrann, Playwright Bess welDen, anD artistic Director anita stewart, in a talKBacK after Madeleines By Bess welDen at PortlanD stage comPany

Not Quite Almost by John Cariani

PlayNotes Season 51 Editorial Staff

Editor in Chief

Todd Brian Backus

Contributors

Charlie Bowen, Sadie Goldstein, Micki Demby Kleinman, Kimmarie McCrann, Larsen Nichols

Copy Editor

Adam Thibodeau

Cover Illustration

James A. Hadley

Portland Stage Company Educational Programs, like PlayNotes, are generously supported through the annual donations of hundreds of individuals and businesses, as well as special funding from:

The Simmons Foundation

Susie Konkel

Harold & Betty Cottle Family Fund

Letter from the Editors

Dear PlayNotes Readers,

We're so excited to have you with us for the new year and our latest edition of Playnotes!

In this issue, we explore the world of Not Quite Almost. This world premiere by John Cariani is part of our New Work program, and likely to become another Maine classic! Near the Canadian Border the Perseid Meteor Showers are about to start, but the residents of a certain small town can’t decide if they’re a bad omen or a good luck charm. Not Quite Almost is an interconnected collection of short plays about young love, hope for the future, making wishes, and what it means to be truly understood. Meet a new cast of characters you’re sure to fall head over heels for.

Want to learn about this production of Not Quite Almost ? Head over to our "An Interview with the Director and Playwright: Sally Wood and John Cariani” (Pg. 9), and meet our actors in "About the Characters" (Pg. 8).

Are you curious about the stars? Check out "Perseids: Science and Culture" (pg. 16), or "Light Pollution and Dark Sky Places" (pg. 18). Want to foster your connection to this beautiful state we call home? Check out "Indigenous Stewardship in Maine" (pg. 24).

When compiling each issue of PlayNotes, we strive to provide articles and interviews that give you insight into what the process has been like behind the scenes (see articles in "Portland Stage's Not Quite Almost" ), contain pertinent information about the play’s setting and major themes (“The World of Not Quite Almost ”), and provide deeper dives into specific subjects that compelled our literary department (“Digging Deeper”). We include a list of books, plays, recipes, and other media that we hope audiences will access for more cultural content that relates to the play (“Recommended Resources”).

We are delighted to have you join us for this heartwarming world premiere, and we hope you enjoy seeing Not Quite Almost.

Sincerely yours,

The Portland Stage Literary Department

Todd Brian Backus

Micki Demby Kleinman

Kimmarie McCrann

Larsen Nichols

About the Play

by Micki Demby Kleinman

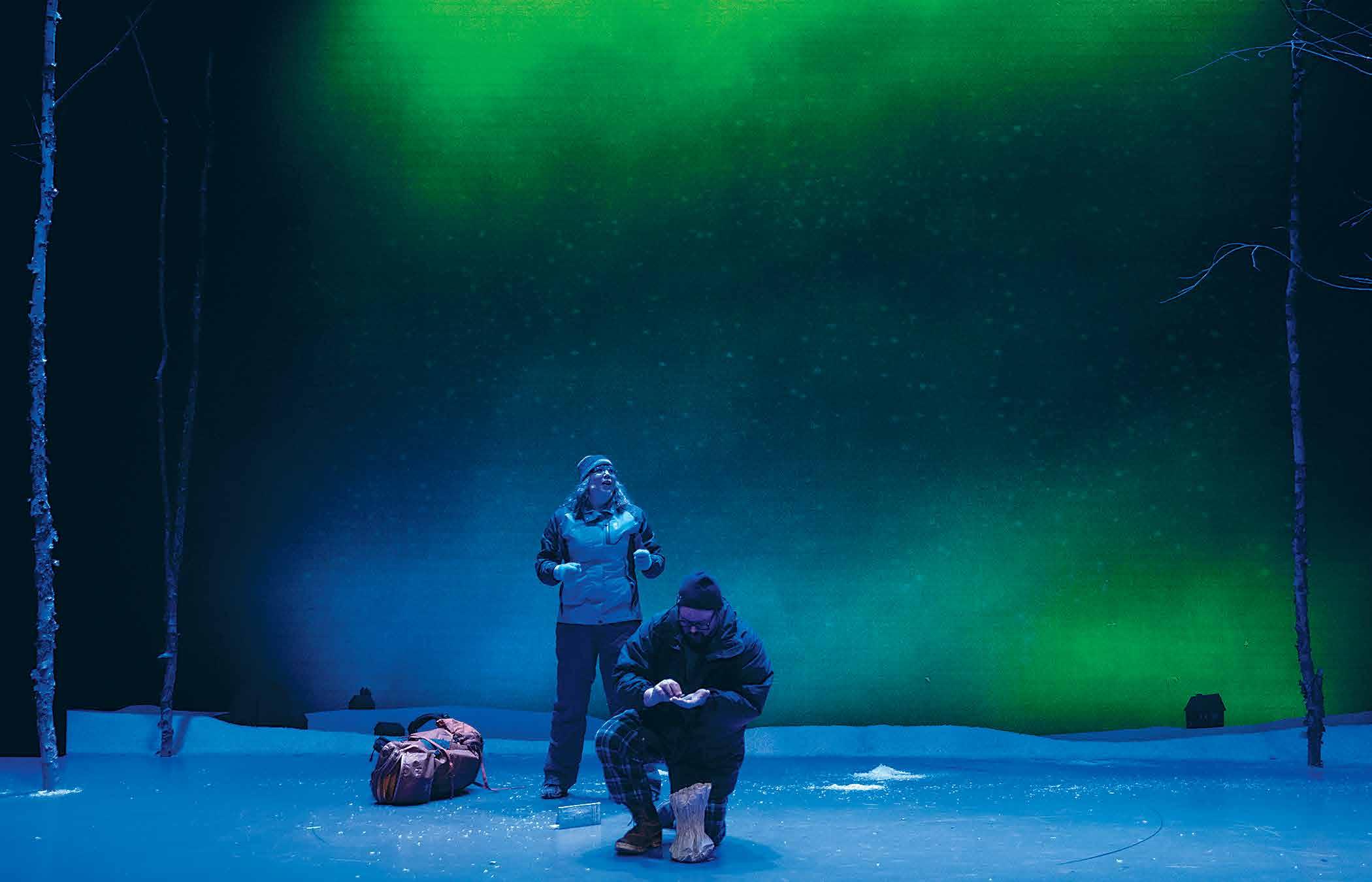

In far northern Maine, residents of a small town observe the annual Perseid meteor shower, wait for the northern lights to appear, and wish on some shooting stars. While witnessing the celestial beauty, the characters discover who they are, and figure out how they show up for their loved ones. Not Quite Almost is an interconnected collection of short plays about young love, hopeful futures, making wishes, and what it means to be truly understood.

In each of the short plays we meet a pair of people who are struck by the wonder of the shooting stars in the deep, dark, late summer skies of northern Maine. Shay and Teddy strike up an unexpected friendship at a time when it feels like everything's over, or everything's beginning. Carly and Jared negotiate the meaning of making something “official.” Tiffany and Marc deal with the events of last year's

meteor shower. Scott and Marty reconnect and see if there's something to rekindle. Sam and Casey navigate what it means to keep loving another person when they grow and change. Siblings Lily and Derek’s familial love is put to the test. And Renee wants to show Gwen some beautiful things, even though Gwen only has eyes for her. Through each story we get to see Cariani's trademark wit and wisdom that's equal parts hilarious and heartbreaking.

In addition to half a dozen casual readings that Cariani facilitated, the script has been workshopped at high schools, colleges, and theaters, from places like Presque Isle to New York City. Not Quite Almost was developed in a professional workshop reading at Portland Stage’s 2024 Little Festival of the Unexpected. This production will be its World Premiere.

from left to right: shawn Denegre-Vaught (aea), John cariani (aea), emily Verla (aea), sally wooD, aiDan J. lawrence (aea), anD hannah Daly at rehearsal for not Quite alMost. Photo By aressa gooDrich

Focus Questions

by Charlie Bowen and Sadie Goldstein

1. Did you witness the total solar eclipse last spring (April 2024)? If not, have you seen any other astronomical event (meteor showers, other eclipses, the northern lights)? Where did you see it? Who were you with? Did the experience make you feel closer to the people around you? Did it make you feel closer to nature?

2. Where do you consider “home”? Is it one place or multiple places? Have you ever had to leave home for an extended period of time? How did that make you feel? What things did you miss or not miss?

3. The characters in Not Quite Almost all have different relationships with one another (siblings, friends, past lovers), but all are experiencing a kind of strain or separation. Have you ever gotten into an argument with someone you’re close to? How did you repair that relationship with them afterwards?

4. Many of the characters in Not Quite Almost talk about “wishing” and making wishes on shooting stars. Do you consider yourself a believer or a skeptic when it comes to making wishes and manifesting your hopes? Do you think the play takes a stance on whether or not wishes come true?

the Poster illustration for not Quite alMost, featuring two PeoPle sitting on a DocK stargazing illustrateD By James haDley

About the Characters

Actor: Hannah Daly

Characters: Shay, Tiffany, Gwen

Shay: 22, a little lost.

Tiffany: 23, widowed a year prior. Figuring out her future.

Gwen: 18, wants to make some heaven happen here on earth.

Actor: Shawn Denegre-Vaught (AEA)

Characters: Jared, Marc, Marty, Derek

Jared: 18, desperately loves Carly, and wants her to come back from war intact.

Marc: 23, dealing with his big mess-up as best he can.

Marty: College-aged, back home for the summer from Harvard.

Derek: 20s, acclaimed baker in Portland, former convict, learning to show up for his sister.

Actor: Emily Verla (AEA)

Characters: Carly, Sam, Lily, Renée

Carly: 18, heading off to war as a geospatial engineer technician.

Sam: Late teens, wondering about what they are.

Lily: 19, knows what she wants in life and unabashedly pursues it, even when others may have concerns.

Renée: 17, LOVES everything celestial.

Actor: Aidan J. Lawrence (AEA)

Characters: Teddy, Casey, Scott

Teddy: 18, state park summer employee. Helping out a friend.

Casey: Teenaged, loves his friend no matter what.

Scott: College-aged, Confident. Proud new business owner of Great Scott! Cleaning.

An Interview with the Director and Playwright: Sally Wood and John Cariani

Edited for length and clarity by Micki Demby Kleinman

Micki Demby Kleinman sat down with director Sally Wood and playwright John Cariani and spoke about their dynamic artistic collaboration, creating new plays, and the appeal of short-form stories.

Micki Demby Kleinman (MDK): You two have a longstanding artistic relationship and have worked on many plays together here at Portland Stage. How did this collaboration and friendship begin? How has it changed over time?

John Cariani (JC): Oh, I saw The Drawer Boy back in 2010. And I went to Anita [Stewart, Artistic Director] and I said, “Whoever directed that play is who I want to direct my new play [Last Gas].” And she said, “That's Sally Wood.” That was it.

Sally Wood (SW): That's so funny, you never even had laid eyes on me.

JC: No, but I had heard good things, you know, from other people. I saw that production. I was like, this is some of the clearest storytelling I’ve seen in the theater in a while… And then we met and we liked each other. Loved each other. Then we got to work and Sally just went at the script of Last Gas—like, really interrogated it— and gave it shape and momentum and helped it become a really good play. That was my first full-length play, Last Gas, and Sally had to really help me make that play work.

MDK: How many plays have you guys worked on together?

SW: Four, right?

JC: Last Gas; LOVE/SICK; cul-de-sac ; Almost, Maine; and this one. So five.

SW: Whoa! That's a lot.

MDK: John, what inspired you to write this play?

JC: I honestly don't remember. These are old plays. These are short plays of mine that

have been kicking around in colleges and universities that people will do for scene work. And I guess my publisher would get requests for some of these plays and my publisher would ask me what these orphan short plays were all about… And I explained that they were these short plays that I wrote when I was writing Almost, Maine, but they didn't really belong in Almost, Maine. I think I may have said, “They kind of stink,” and my publisher said, “Put them together and finish them and make them not stink,” basically. These plays have been sitting on a hard drive for a long time, and they kind of gnaw at me, my orphaned plays. And then my friend Elizabeth Guffey did one of these short plays at a short play festival in Freeport, and I told her there were more where that play came from, and she said, “You should work on those!” And then I gave them to Dan Burson [former Portland Stage Literary Manager], and Dan was like, “Yeah, I think there's something here.” And then I told Todd [Brian Backus, current Portland Stage Literary

Playwright John cariani.

Manager] and Anita about it, and next thing I knew, they were scheduling this new collection of plays for Little Fest[ival of the Unexpected]. I don't know if I would have trusted this collection of plays to be ready for Little Fest, but they knew that if they scheduled it, I would work my butt off to get it ready. And they told me I needed to, and I did. Side note: the plays in Darker the Night, Brighter the Stars are not at all what they once were! I have worked my butt off to make them worthy of being at Portland Stage!

Short answer: Northern Maine. I love where I’m from and the people who live there. That place and those people made me who I am. Think John Mellencamp’s “Small Town.”

MDK: Sally, I know that you work on a lot of world premieres and new scripts. What is it like as a director to work on a published play versus to develop a new play?

SW: You know, some playwrights are just not into Sally Wood, and that's okay. Some playwrights don't really want someone to come in and meddle with their work, and I totally get that. They probably workshopped it a thousand times and they're just done. That is my least favorite kind of scenario because they don't actually want input. It's funny, I find myself straining against already published plays because I'll see things and I'm like, oh man… I have a good relationship with John, a good relationship with Monica [Wood]. With people who I've worked with for a while, you get a shorthand… I'm way more mouthy in a way that I’ve never done before where I'm like, “Look—”

JC: She says things like, “I got a big one—a big change for you to make—” and she'll look at my face and realize that I might not be up for it and say, “We're gonna do it later.” Or if I look up for it, she'll say, “You ready?” And I go, “Yep, okay?” And then she works her Sally magic on my play— which usually means cutting, cutting, cutting.

MDK: Sally, what is it like to direct a play while the playwright is in the room with you?

SW: Well, it depends. You know, John is so great because, by having John in the room, the actors are basically seeing a case study on

one of John's characters. Because you [John] write the way that you speak. Also, there's something magical because John's not only taking ideas that I'm throwing out, but what the actors are throwing out. And that never happens, actors so rarely are allowed any kind of artistic space for that. Like, in a lot of cases, they are the puppet, you know what I mean? And it's just like, you fit the costume or whatever, this is the way so-and-so did it or whatever. And [with John] you just see [the actors] kind of open up, and I think that's remarkable. And some stuff isn't gonna be the way that John pictured in his head. Some stuff isn't gonna be the way that I pictured in my head. Because that's not the rehearsal room that we have now. We've got strengths that we didn't know we had, and we have some areas that aren't as strong as they are in my brain, and that’s okay. I can spend the entire rehearsal process trying to get people to do the play that's in my head, but that's so not interesting.

MDK: The structure of this piece is in some ways similar to your other plays, such as Almost, Maine or LOVE/SICK , where there are stand-alone plays within a larger universe, or connected somehow. Why are you drawn to this structure?

JC: I just love the short form. I love short plays, I love short stories, I love short films, and I love songs. I love how efficiently they

Director sally wooD.

do what they do. I don't love novels and I don't love long movies, and I don't love very many long plays that I see. I hate to say it, but they're not committed to the form or the story they’re telling–they're committed to…I think whatever the creator wants to say more than they are to what the creator is making. I think short-form art is committed to what it’s doing, the story it’s telling, and to doing everything as efficiently as possible. And I'm just interested in that efficiency in what it does for storytelling, I guess that's what I would say.

SW: And I think it's just an accident, too. There was a vision for four actors in Almost, Maine when it started. When it began to propagate everywhere else, then it became a play for 20, you know what I mean? People want those plays. Well, it's remarkable if you're trying to find something with a big group of people, how to not have a play that is a star vehicle for two roles and everybody else has got their two seconds. A play like this, everyone's got their ten minutes. That's really such a gift, you know, especially if you've got a bunch of college

students that you're like, hey, I want to give everybody something to sink their teeth into.

MDK: There's a lot going on in this play, a lot of characters and a lot of different storylines. I'm just wondering, what do you hope that the audiences walk away with after seeing the play?

JC: Just knowing—remembering—that difficulty and beauty and happiness and pain can exist all at the same time, and that extraordinary things happen to ordinary people. Extraordinary isn’t owned or bought. It’s for everyone.

SW: It's funny. I keep hearing what you said at one of the Bates [College] talks, which was “queer, rural, and happy.” To have the girl from Walmart be able to have a happy ending feels outstanding to me. I just hope that people will turn to each other when it's over and be like, “There's so much to be happy about.” If we're just a tiny bit lucky, we can find it. And if it starts conversations, that's a million times better, too.

the cast anD crew of not Quite alMost.

Community Connections: An Interview with OUT Maine

Edited for length and clarity by Larsen Nichols

Directing and Dramaturgy Apprentice

Larsen Nichols sat down with Ellie Roy, OUT Maine’s Communications and Social Media Coordinator, for a conversation about the organization's programs and advocacy for queer youth in Maine.

Larsen Nichols (LN): Could you give me a brief overview of OUT Maine’s work as an organization and the kinds of programs it provides?

Ellie Roy (ER): OUT Maine is based in Rockland, but we provide programming all across Maine. We do a lot of virtual youth programs as well as adult programs for school staff support, parent support, GSTA [Gay/Straight/Trans Alliance] advisor support. For youth programs we do a lot of support groups, as well as a couple of yearly youth retreats [like] Rainbow Ball Weekend, which is our biggest event every spring. [Rainbow Ball Weekend] is a threeday, weekend-long retreat for youth with educational workshops and a queer-friendly prom with a bunch of donated clothing items so folks can dress in a way that they may not feel safe enough to do otherwise. We do a lot of really great things to help empower youth and educate adults throughout the state.

LN: How did you get involved at OUT Maine, and what does your work mean to you?

ER: I actually started in marketing so I come from a marketing agency background. My role at OUT Maine is more focused around the communications aspect of things—I handle a lot of the website tasks and social media press releases, things like that, which I really love. I've been able to develop my writing skills and graphic design skills in a way that feels productive. It's really nice to be able to put my creative skills to work with an organization that is making a difference in the community that I myself am a part of. It feels more meaningful that way, like I'm actually making a difference with the skills that I have.

LN: Did you grow up in Maine?

ER: I did, yeah, I grew up in Gray. I graduated from Gray–New Gloucester High School in 2017.

LN: What are the most important things for people to know about queer kids growing up in rural areas of Maine? What are some challenges that these kids face?

ER: Especially in a lot of the more rural places across the state, queer youth are disproportionately affected by homelessness, bullying, and harassment in schools and at home. They're a lot less likely to have those social supports that people can take for granted in bigger cities. So it's really important for organizations like OUT Maine to provide those virtual programs. We find a lot of kids from farther away, like smaller towns way out in western Maine and northern Maine, attend those virtual groups, where they may not have a lot of in-person programming close to them. So developing that social connection in a way that is accessible for everybody on a geographical level is a huge thing that we've been working on for the past few years.

ellie roy, communications anD social meDia coorDinator at out maine

LN: Can you tell me more about OUT Maine’s partnerships across Maine?

ER: We partner with a lot of different organizations across the state. We have a couple partnerships with some organizations in Aroostook [County], as well as some Portland and southern Maine organizations. We have programming all around the state and we often travel around to different schools throughout all 16 counties. We have connections with GSTA advisors in different school systems throughout the state. So we're kind of all over the place, but we are just based in Rockland for now.

LN: How do you find the climate towards queer youth in more rural areas of Maine? Do you ever encounter pushback in school districts or counties that are more conservative, and how do you handle this as an organization?

ER: There is definitely a difference in the tone in a lot of school systems [in rural areas]. If we go to a Portland school or a bigger city like that, folks are generally a lot more accepting of us teaching a workshop on, like, DEI best practices, than they would be if we were to go to a school up in Aroostook in Fort Kent. That's always difficult, but we also have to remember there's queer kids everywhere. In every town, in every school, there's going to be at least a handful of queer kids who, oftentimes, will feel very alone and isolated. So it's important for us to make the journey way out to the middle of nowhere, have those workshops, make those connections, and promote our programs wherever we can so that we can make sure we reach those kids who feel so isolated and alone and let them know that they’re not.

LN: What advice does OUT Maine have for building queer community in rural spaces?

ER: Our biggest advice would be to keep an open mind and find safe gathering spaces. We’re actually having a pilot program right now where we are training some public library staff to host queer-friendly game nights, and we are encouraging youth in that area to attend that as a safe, neutral-ground meeting

space. If one teacher in a school wants to start GSTA but they're having pushback from their administration, find that external safe space and promote it and see if you can create that safe space for students and kids.

LN: How can people learn more about OUT Maine’s work?

ER: Our website is OUTmaine.org, and that has a program calendar of all of our upcoming events all throughout the state, in person and online, as well as our social media. We're on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Bluesky and TikTok a little bit too nowadays, so folks can follow us there for any new program updates.

LN: And for my last question: how can the average individual support queer youth in Maine?

ER: By going to Pride, by attending school events where advocacy is a bigger deal. If your local school board is dealing with any pushback in regards to queer/trans issues, attending that and advocating for queer youth in your area is huge. Also donating your time—our youth programs, especially our in-person ones, are always looking for new volunteers, so that is a great way to get involved. And there's tons of other youthserving organizations all throughout the state that do similar things, so if you're into volunteering, there are innumerable ways to get involved, and I highly recommend that.

Pre-Show Activities

by Charlie Bowen and Sadie Goldstein

1. John Cariani, in his “Note for Readers” at the beginning of the script, says that Not Quite Almost “is an autobiographical and biographical collection of related short plays that will hopefully shine some light on what it’s like to grow up in rural northern Maine. Rural Americans are largely absent from contemporary American theater, TV, and film. And when they do appear on our stages and screens, they’re not portrayed with much complexity, compassion, or dimension.” Think about this quote by playwright John Cariani. Do you agree? Come up with a list of characters or stereotypes you have seen in media (theater, TV, or film) featuring rural Americans. What do you notice in common with the things you listed?

2. All of the scenes of Not Quite Almost take place on August 12 around 9pm in different locations all over Maine. Pick a location that could have many people at or in it (a store, a park, perhaps even a whole state). Imagine the different types of people that could be at that place. Why might they be there? Who are they with? Come up with three pairs or groups of people in that location, and write a description of who they are and why they’re there.

3. What do you know about the northern lights and the Perseids? Have you ever experienced either? Find a partner. One of you can read the PlayNotes article “Northern Lights: Science and Culture” and the other can read “Perseids: Science and Culture.” Come back together and share what you have learned with your partner.

4. Many of the characters in Not Quite Almost are facing a turning point in their lives as they are about to graduate, or have just recently graduated, from high school. Not Quite Almost represents many different avenues that a young person can take outside of college. Do you find there is an expectation for you or those around you to seek higher education? Do you feel as though you are well-informed on other options that are available to you?

Post-Show Activities

by Charlie Bowen and Sadie Goldstein

1. Not Quite Almost has four actors who play different characters in most scenes. Did you enjoy this? Did you find it confusing? If you were putting on this play, would you stick with the four actors, or have a new actor for each character?

2. In the script of Not Quite Almost, John Cariani expresses in his note to readers (see question #1 of the pre-show activities) that he intends to portray those who reside in Maine authentically. After having seen the show, did you feel as though young people in Maine were portrayed authentically? Which characters shared similarities with you? Which characters did you have a harder time relating to?

3. The northern lights, Perseids, and different elements of nature are all important moments and themes in Not Quite Almost. How were they depicted in the play? Think about the different technical elements used to depict them onstage (lights, set, props).

4. Shay and Teddy connect with one another as they walk through the state park in Not Quite Almost. Consider planning an outdoor adventure of your own. This does not have to be as “grand” as a trip to a state park; all you have to do is open your front door. After the experience, journal your reflections. What did you take away from your time outside? Did you enjoy yourself? Is your relationship with nature important to you? Feel free to expand past these prompts!

Northern Nights, Northern Lights

by Micki Demby Kleinman

In John Cariani’s new play Not Quite Almost, a myriad of characters engage with the celestial beauty of the natural world. The northern lights are a phenomenon the characters marvel at the opportunity to see. What are the northern lights and why do they occur?

The northern lights, also known as aurora borealis, are a unique display of colorful lights that can occur in the Northern Hemisphere. Beautiful swaths of purple, pink, red, and green swirl and jump through the night sky. Astronomers have observed that these lights are a result of an interaction between the sun and earth’s respective magnetic fields. During solar storms, the sun emits energy and particles into the solar system. This explosion can cause a disturbance in earth’s magnetic field, creating undulations known as Alfvén waves. The more active the solar storm is, the further south the Alfvén waves extend. Particles from the solar storm travel along the Alfvén waves and collide with gases in earth’s atmosphere. The interactions between the particles and gases create the colorful flashes of aurora borealis.

Because of the erratic timing and otherworldly visuals of the northern lights, many cultures developed explanations for why the phenomenon occurs. The Sami are a group of Indigenous people native to primarily northern Norway. Some Sami groups believed that the lights were the spirits of their ancestors dancing in the afterlife. The movement of the lights corresponds to the movement of their ancestors’ spirits. Out of respect to their ancestors, the Sami behaved reverently and tried not to provoke the spirits, lest they be punished and taken into the afterlife unwittingly and prematurely. It was considered a sign of disrespect even to whistle or sing

in the presence of the northern lights for fear of disturbing the spiritual realm. Similar to the Sami people who believed the lights were spiritual communications, Indigenous Greenlanders, a branch of Inuit people, believe that the lights are the spirits of stillborn and dead babies in the afterlife. However, unlike the Sami, this interaction was not something to fear, as the lights were seen as an act of comfort for those still living.

According to North Germanic Norse culture, the northern lights valkyries are the reason the Northern Lights appear. Valkyries were women who helped fallen soldiers get to the afterlife in Asgard, the realm of the Norse gods. As the women carry the souls of the departed to the gods, their armor and chariots create a beautiful, colorful display in the night sky, which is what humans see as the northern lights.

Unlike the Norse, Sami, and Inuit people, certain cultures’ understandings in Finland surrounding the northern lights are quite different. The Finnish believed that a “firefox” scampered across the night sky, its tail brushing up against the snow, creating flame and sparks, which humans perceive as the northern lights. The Finnish term for the northern lights is “revontulet,” which translates to “fox fires.”

The folk tales regarding the northern lights extend to cultures further south than one would think. It has been proposed that a country as far south as China has mythology surrounding the northern lights. Although merely speculated, it has been said that the Chinese legend of the dragon was perhaps inspired by a rare glimpse of the fiery, flaming colors of the northern lights.

The phenomenon that is the northern lights used to be a mystery, and is now understood. However, just because this natural wonder has been scientifically ascertained, the spiritual connection with the lights does not need to be discarded. Paying attention and paying respect to these beautiful lights continues to be a sentimental activity and a way to learn about other cultures.

a View of the northern lights

Perseids: Science and Culture

by Casey Pitts

Have you ever seen a shooting star? Bright streaks of light, flying through the sky so fast that if you blink, you could miss them? Contrary to their namesake, these “shooting stars” are not stars at all! They are meteors, disintegrating in Earth’s atmosphere so rapidly that they leave behind trails of bright light. Throughout the production of Not Quite Almost, you will find that the characters frequently see, and miss, shooting stars from the Perseid (pronounced per-see-id) meteor shower.

You may have heard meteors referred to by various different names, such as “meteoroid” and “meteorite,” but these words just tell you where the object exists. When a small rock or piece of debris, typically ranging from the size of a dust grain to a small asteroid, is floating in space, we refer to it as a meteoroid. As a meteoroid enters Earth’s atmosphere at rapid speeds, it begins to disintegrate, leaving behind a trail of bright light. This is a meteor, or what we more affectionately call a “shooting star.” In the case that a meteor is lucky enough to survive its descent to Earth, the object we may find on the ground is called a meteorite.

Meteors can be seen at any time throughout the year, given that the night is clear enough. There are periods of time, though, where you might observe a far larger sum of meteors throughout the night. These are called meteor showers. Meteor showers occur when Earth’s orbit intersects with debris left behind by comets that have previously passed through the inner solar system. As Earth passes through these large concentrations of space debris, our gravitational field pulls in more meteors, causing them to streak through the sky at a higher frequency.

Arguably the most famous meteor shower, the Perseids, occurs annually from mid-July to late-August, with a peak centering around August 12. During the shower, these meteors can be seen at a rate of up to 100 meteors per hour! Perseids are particularly notable for their fireballs, a phenomenon in which larger

particles of material create larger explosions of color and light that often last longer than the average meteor streak. Considering this, it is no surprise that the Perseid meteor shower has become one of the most popular showers for viewing. But where does the Perseid meteor shower come from?

The concentration of debris that causes meteor showers is left behind by comets that orbit the sun. In the case of the Perseid meteor shower, the comet of origin is Comet Swift–Tuttle. Swift–Tuttle was discovered by and named for American astronomers Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle in 1862. Though the comet bears both of their names, these two were not partners, and instead discovered the

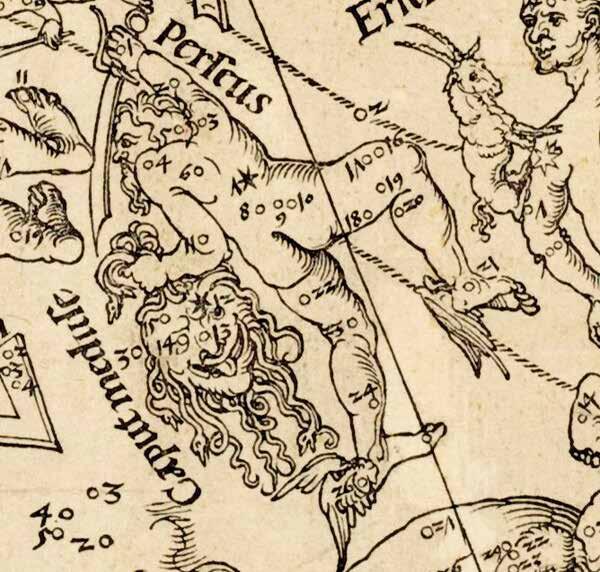

the constellation Perseus (laBelleD) as seen with the naKeD eye

comet independently three days apart. Years after Comet Swift–Tuttle’s discovery, in 1865, Giovanni Schiaparelli observed the connection between comet Swift–Tuttle and the Perseids, discovering that the comet left behind the debris we see as the Perseids. Swift–Tuttle orbits the sun once every 133 years, and was last found in the inner solar system in 1992, meaning it will not enter again until 2125.

It may seem unbelievable that the Perseid meteor shower can occur at the same time every year, but the orbital path of Earth and comet Swift–Tuttle guarantee it. As Swift–Tuttle completes its 133-year orbit around the sun, it leaves behind a trail of debris that travels along the same orbit at a much slower pace. As Earth continues its 365-day orbit around the sun, it intersects with the orbit of Swift–Tuttle. The trail of abandoned debris then becomes the Perseids. Since the orbits of Earth and Swift–Tuttle are a predetermined path, Earth intersects with the debris of the comet at the same time each year.

You might be wondering why this meteor shower is called the Perseids. Meteor showers are named for the constellation in which their radiant, or apparent origin point, is located. Scientists find this spot by tracing the streaks of the meteors to find the point where the streaks appear to meet. The Perseids' radiant point lies within the Perseus constellation, giving them their namesake. The word “Perseid” comes from the Greek word “Perseides,” meaning “descendents of Perseus.”

Throughout time, there have been many different cultural, religious, and spiritual explanations for meteor showers. The Perseids, in particular, were known to early European Christians before their scientific discovery in 1865. In 258 CE, Roman Catholic deacon Lawrence refused to turn over the church’s money to Roman emperor Valerian, distributing it instead to those who were struggling in his community. For this, Valerian sentenced Lawrence to death, burning him over hot coals. It is believed that during his death, Lawrence told his executioners to “turn him over,” claiming that he was done on one side. Lawrence’s death designated him as a martyr and earned him sainthood shortly after his execution. When those followers of Saint Lawrence later made the connection that the then-unnamed Perseid meteor shower occurred annually around the time of Saint Lawrence’s death, they came to believe that the meteors were his burning tears. Thus, the Perseid meteor shower is known to some as “the Tears of Saint Lawrence.”

Before humans discovered the science around meteor showers and other astronomical events, we found other explanations for what they meant. Whether it be that the heavens were opening up to Earth, the spirits of our loved ones were passing by, or a wish could be granted, people have always found a meaning for shooting stars. Throughout Not Quite Almost, we are reminded of what that meaning is for different people.

the PerseiD meteor shower, in aDDition to the north america neBula anD the anDromeDa galaxy.

a meteor streaKs across the sKy During the annual PerseiD meteor shower. west Virginia, august 2015.

Light Pollution and Dark Sky Places

by Kimmarie McCrann

“...a small town in far northern Maine under a deep, dark, spectacular northern night sky.” -Not Quite Almost

We often associate pollution of the natural world with categories like air and water pollution. However, there is another kind which causes harm to the environment every night: light pollution. DarkSky International, the leading nonprofit organization combating light pollution in the United States, defines light pollution as “the human-made alteration of outdoor light levels from those occurring naturally.” A side effect of industrial civilization, light pollution is the overlighting of natural skies which makes it very difficult, even impossible in some regions, to see the stars at nighttime. Not only does light pollution deprive humans of spectacular views of the cosmos, but it has increasingly negative impacts on climate change, migratory animals, and overall human health.

According to a 2016 study published in Science Advances, 80 percent of the world’s population lives under light pollution, with 99 percent of the people living in Europe and the United States experiencing skyglow at night. An average year in the US alone uses about 120

terawatts of energy in outdoor lighting, which is enough energy to light all of New York City for two years. Only the most remote regions of the world, including sections of Siberia, the Amazon, and the Sahara Desert, are in total darkness. Astronauts from the International Space Station have observed light pollution growing, with glowing cities on Earth becoming increasingly easy to view from space over the past few decades. Fifteen million tons of carbon dioxide are emitted each year to power residential lighting, which gets stuck in the Earth’s atmosphere and adds to global warming and climate change risks.

So, what exactly causes light pollution? Several of the primary causes include streetlights, outdoor residential lights, electronic advertising, sports stadiums, and factory lighting. When these lights are left on 24/7 without a motion sensor or timer, they greatly contribute to the unnatural overlighting of the sky. These lights are particularly adverse when unshielded and pointed upwards towards the heavens, rather than only lighting the ground and necessary areas for sightlines to the human eye. Additionally, most wasted outdoor lighting

consists of harsh blue fluorescent lighting, rather than a softer, warm-toned alternative. Light temperature is measured in degrees Kelvin (K), and warmer lights (3000K or less) have the least impact on light pollution. Since blue light can simulate daylight and has an extremely high temperature (typically 4500–6500K), it too easily brightens the night sky.

An empty parking lot or sports arena that is lit up all night doesn’t serve any human activity, and only confuses local animals and insects. Migratory mammals accustomed to following natural light patterns have become progressively confused by excess night lighting, which is disrupting their paths and increasing mortality rates. Sea turtles are commonly affected by light pollution, because when their eggs hatch at night, the infant turtles are supposed to follow the light of the moon to safety in the ocean. However, many turtles are distracted by lighting from residential houses ashore and travel in the opposite direction, leading to their untimely deaths due to dehydration or traffic. Fireflies are in danger as well because the males are competing with artificial light and unable to attract female counterparts to reproduce. As a result, fewer fireflies are born each year, and it is almost impossible to see any at all in highly lit areas of the world. Tree frogs are experiencing similar difficulties because male tree frogs tend to stop or lessen their mating call in areas where there’s lots of light. Monarch butterflies and wild salmon are confused by artificial light, causing them to migrate more randomly during the year and off their typical, safer travel courses. Thousands of migratory birds have died or been caught in confusion as a result of the annual 9/11 “Tribute of Light” public art installation in NYC, when two beams of intense blue light shoot up from where the Twin Towers once stood. And that’s just from two lights. One can imagine what disruptions are being caused by the bright lights of cities all around the world.

Human beings are also detrimentally affected by light pollution. As a species, we adhere to a circadian rhythm, an intrinsic biological clock which follows the natural day and night cycle. This rhythm tells us when to sleep and wake

up, and is greatly influenced by photoreceptors in the eyes which are more sensitive to blue wavelengths of light. According to the American Medical Association, “it is estimated that white LED lamps have five times greater impact on circadian sleep rhythms than conventional street lamps.” Research suggests that exposure to artificial light at night (LAN) is associated with poorer sleep quality, impaired daytime functioning, and increased levels of obesity and depression. Additionally, several studies over the last few decades have indicated that humans are at a higher risk for hormonal-related diseases like breast or prostate cancer with exposure to too much harsh light. LAN also suppresses the body’s production of melatonin, which induces sleep, has antioxidant properties, boosts the immune system, and helps the functioning of the thyroid, pancreas, ovaries, testes, and adrenal glands. In 2007, the International Agency for Cancer Research declared night-shift work a probable human carcinogen.

There are many negative cultural implications associated with light pollution as well. Light pollutant researchers have discovered that we are losing our view of the sky at an astonishing rate of 10% each year. The Indigenous Wabanaki peoples of northeast America, with Wabanaki literally translating to “People of the First Light,” place a great deal of pride and religious association with the night sky. John

“triBute in light” 9/11 memorial in new yorK city.

Bear Mitchell, a Wabanaki lecturer currently working at the University of Maine, says that his culture believes that the stars are fires lit by our ancestors once they have passed away. And then, when we pass away, we search the cosmos to find the correct fire that our loved ones are gathered around, and we join them. Losing sight of the stars can make young Wabanaki people feel disconnected from their ancestry and history. And for all people, the stars often represent a sense of greater purpose and serve as a reminder of our small size in the large universe. Looking above at the vast night sky can help people to breathe and remember that their worldly problems aren’t so terrible in the grand scheme of things.

There are still places where people can go to experience the natural night sky. These rare locations are known as Dark Sky Places, which have gone through critical assessment by the International Dark Sky Places program. The institution is an independent thirdparty organization that reviews the dark sky conditions and protection practices of candidate locations, and certifies only the most outstanding ones that meet all criteria. Several of the eligibility requirements for a Dark Sky Place to become certified by DarkSky International are as follows; the Milky Way must be readily visible to the unaided eye, there are no nearby artificial light sources yielding significant glare, and any light domes present are dim, restricted in extent, and close to the horizon. Over 200 places around the world have been certified since 2001.

Dark Sky Places are most commonly national and state parks, recognized for their minimal light pollution and ideal stargazing. Katahdin Woods and Waters was the first International Dark Sky Place certified in the State of Maine and New England, and it remains today one of the darkest places in the eastern US. The only other official Dark Sky Place currently located in the state is the Appalachian Mountain Club’s 114,000-acre forest located in central Maine. These places are rated at a 1 or 2 on the Bortle scale. Developed in 2001 by American astronomer John E. Bortle, the Bortle scale operates on a ranking scale of 1–9, with 1 being the most pristine and darkest skies, and 9

representing a severely light-polluted sky. Only a few areas in the lower 48 states display class 1 or 2 skies, while the skies in many western national parks are class 3 or 4. For perspective, the Bortle score of Portland, Maine, is 7, while Boston, Massachusetts, has a score of 9.

The good news is that light pollution is one of the only kinds of pollution on our planet that is reversible. While the long-term effects of air, land, and water pollution are difficult to undo, if all the lights in the world went out tonight, we would be able to see the stars. They are still there, just shrouded by glare and an overabundance of light. Everyone can take part in the solution by becoming educated and aware of the kinds of outdoor lighting they have, and how often they keep these lights turned on. People can join social and activist groups like the Dark Sky Society, Dark Sky Maine, and Mountains of Stars to support educational and legislative efforts to eliminate light pollution. Even taking a trip to visit a Dark Sky Place and making memories under the night sky is a great way to contribute to astrotourism and the financial support of these parks. Maybe one day Times Square won’t need to be brightly lit all night, and we can see an even more spectacular view up above.

granD canyon national ParK- international DarK sKy ParK certification ceremony

Glossary

by Micki Demby Kleinman

Asterism: A group of stars that form a pattern. A section within a larger constellation.

Cassiopeia: A constellation named after Cassiopeia, a queen in Greek mythology.

Celestial: Relating to heaven, the heavens, the sky, or divinity.

Comet: Hunks of ice and gas streaking through the universe.

Double-wide: Double-wide trailer. Mobile home.

Bear Constellation: Otherwise known as Ursa Major. Ursa Major is Latin for “large bear.”

Big Dipper: Asterism of stars within Ursa Major.

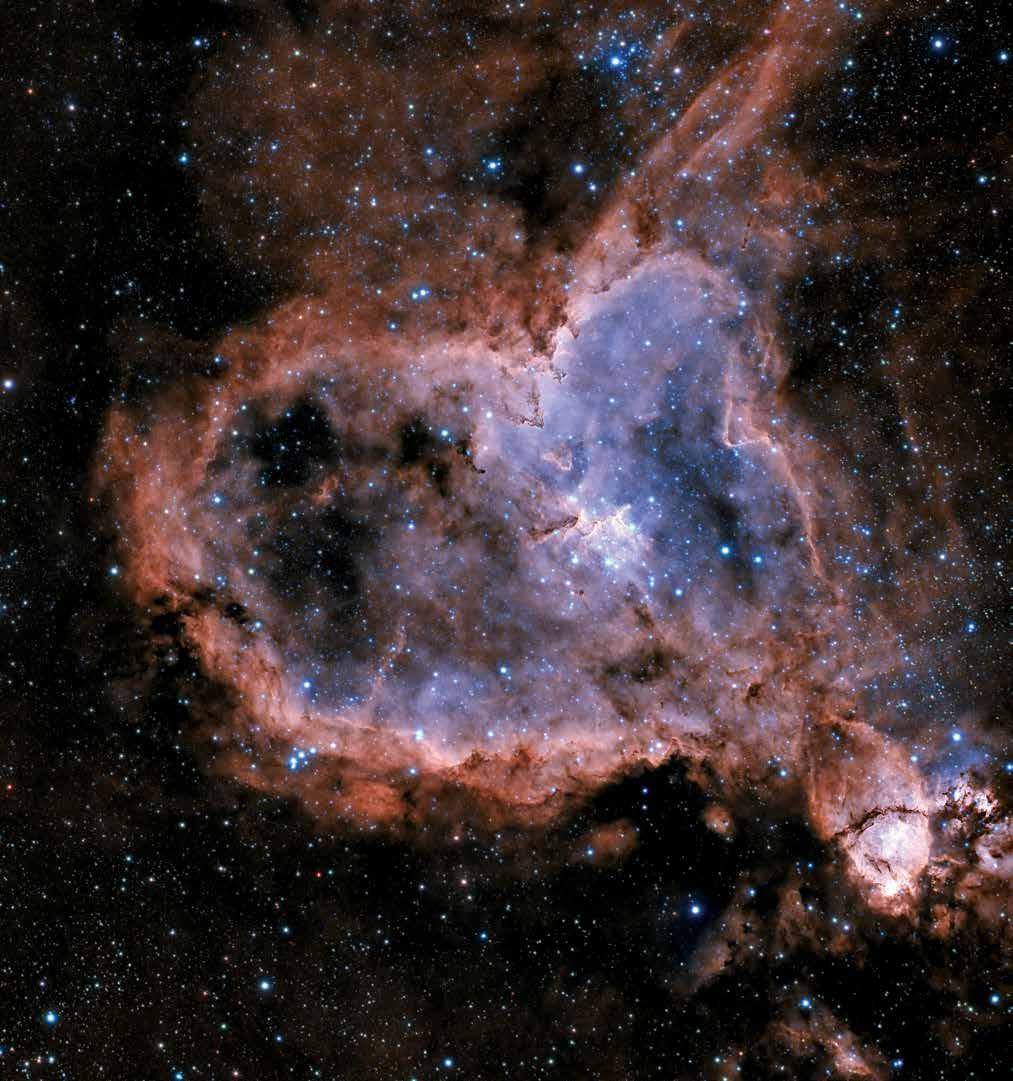

Heart Nebula: Nebulae are clusters of ionized gases and dust in space surrounding a dying star or a new star in the midst of creation. The Heart Nebula is reddish in color and in the shape of a heart. The nebula was discovered in the late 1700s.

Jump School: The United States Army Airborne School, where soldiers learn to jump out of airplanes with parachutes as part of their training.

Little Dipper: Constellation also known as Ursa Minor, Latin for “lesser bear.” Contains Polaris, the North Star.

Meteor: Rocky debris from comets that creates a streak of light when it burns up upon entering Earth’s atmosphere; often called a “shooting star.”

Meteorite: Rocky debris from comets that lands on Earth rather than burning up in the atmosphere.

Perseus: Figure of Greek mythology. Son of Zeus and the mortal Danaë. He beheaded Medusa.

Unorganized Territories: Areas in Maine with no local government. Services and tax responsibility are shared by county and state governments. More than half of Maine’s total land is unorganized; 9,000 people live in the unorganized territories year round, with more seasonally.

the heart neBula in the constellation cassioPeia.

the constellation Perseus DePicteD in alBrecht Dürer's maP of the northern sKy

Blue Collar Work in the Media

by Kimmarie McCrann

A theme in John Cariani’s Not Quite Almost is the depiction of blue-collar workers in rural, northern Maine. Many of the play’s characters have jobs working at places like Walmart, as park rangers, or running cleaning companies. In intimate two-hander scenes, these characters often discuss what it means to hold these kinds of jobs, to remain in the town they grew up in, and the social biases surrounding their choices in life. So, what exactly is a blue-collar job? And how are they portrayed in the media?

The term “blue-collar” has been around since the 1920s in America to refer to a specific type of work. “Blue-collar” typically means jobs that require hands-on physical labor, including work in farming, manufacturing, cleaning, construction, and maintenance sectors of the economy. The phrase was first used to allude to these kinds of jobs in an Iowa newspaper in 1924, directly referencing the blue-colored denim and chambray shirts that trade workers of the time frequently wore. These shirts served a practical purpose for employees because dark colors would help to hide dirt, grease, and other materials that might soil their clothes during the workday. By the mid1920s, collared work shirts were being mass-

produced by companies like Montgomery Ward, who featured a “Guaranteed Work Shirt” that came in two colors: blue and gray.

As a result of the increasingly common “bluecollar” phrase, the juxtaposing term “whitecollar” also rose to popularity in the early 20th century. “White-collar” is associated with jobs in office settings, such as lawyers, accountants, marketing and financial consultants, doctors, and upper-level business managers and executives. In 1945, Rear Admiral F. G. Crisp even used the phrase before the US Congress, testifying, “The Navy’s civilian employees fall into two broad groups, blue-collar workers and white-collar workers.” People who worked white-collar jobs were traditionally able to wear starchy white, pressed dress shirts because they did not interact with raw materials during their workday that might stain their clothes in the same way that blue-collar employees did. In the 1970s, social critic Louise Knapp coined the phrase “pink-collar” to describe jobs that were often held by women in America at the time. These included occupations like nursing, teaching, childcare, and other roles that received lower salaries because they were held by women.

a worKer in a leaD-aciD Battery recoVery facility.

The term “white-collar” has a far more favorable connotation than “blue-collar” in mainstream media today. Blue-collar workers are often portrayed as less intelligent and as gruffer, lazier members of society than their whitecollar counterparts. American media has certainly contributed to the harmful social bias that blue-collar work is worth less than whitecollar jobs. Time and time again in Hollywood, blue-collar workers have been portrayed as crude, low-IQ people who typically end up becoming the butt of the joke. A few examples of these characters include Bob from Bob’s Burgers, Tow Mater from Cars, and many of the blue-collar workers in the TV show Shameless. These characters are a gross misrepresentation of the kind, smart, and empathetic people that work blue-collar jobs in real life.

Pop culture depictions such as these can have real-world impacts. Terrence Lurry, a 21-yearold student at Emory University, told Newsweek that he was considering pursuing a career as an electrician, but that societal expectations convinced him to switch to medical school instead. Lurry said, “I think Hollywood is also pushing a narrative towards more postsecondary education. Not often in film and media do you see high school students portrayed as having dreams of entering the blue-collar workforce.” According to the 2024 Blue-Collar Annual Report released by management company Jobber, 76% of Gen Z individuals agree there is a stigma associated with going to vocational school over a traditional four-year university. The same report says that 61% of Gen Z says their parents told them not to consider vocational school or haven't spoken to them about it at all . Additionally, nearly half (48%) of Gen Zs agreed that women were discouraged from pursuing trade careers from a young age. These old-fashioned mindsets, combined with a discouragement from family members, can make blue-collar work seem less and less appealing to young people trying to choose a career path.

This negative portrayal of blue-collar work and a push towards four-year degrees has led to a growing labor shortage in America. The US Chamber of Commerce analysis and

Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in 2022 that 65% of durable goods manufacturing jobs were unfilled, and 40% of wholesale and retail trade jobs were as well. Additionally, ABC News reported in 2024 that “the construction industry will need to attract an estimated 501,000 additional workers on top of the normal pace of hiring in 2024 to meet the demand for labor, according to a proprietary model developed by Associated Builders and Contractors.” The ABC News report went on to estimate that the construction industry will need to bring in nearly 454,000 new workers to meet labor demands in 2025.

The disadvantageous portrayal of bluecollar workers in society and the media is a misrepresentation of the value of the kind and empathetic humans who work these jobs. Blue-collar workers are the most essential to the functioning of our daily lives. If all the plumbers and mechanics went on strike today, we would be in huge trouble. There’s a reason that blue-collar workers were deemed “essential” during the COVID-19 pandemic. John Cariani hopes to shed light on these social biases in Not Quite Almost, and shows how these workers are intelligent people, with dreams, in rural America. Working at Walmart isn’t a “bad” job. There’s no such thing as a bad job—only bad perceptions.

grouP station manager cherry wiltshire anD Bus oPerator aleJanDra frino as guests at the unVeiling of the coViD-19 essential worKers PlaQue in new yorK.

Indigenous Stewardship in Maine

by Larsen Nichols

In an early draft of Not Quite Almost, Teddy mentioned the Mi’kmaq people, and when Shay asked who he meant, Teddy replied, “The people who were here first.” This moment subtly underscored a deeper truth that often goes unacknowledged: long before any of the characters we see in Not Quite Almost inhabited Maine, Indigenous peoples like the Abenaki, Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot had been stewarding the land with care and respect for thousands of years prior. When European colonizers arrived in Maine, the Indigenous population was decimated, and their connection to the land severed as land rights were increasingly stripped away. Today, as the impact of climate change and global warming become more and more pressing, looking to Indigenous wisdom offers us a path to healing. By turning to the wisdom of those who have cared for this land for millennia, we can find ways to restore balance and work together to maintain and restore Maine’s natural beauty.

The definition of Indigenous Stewardship Methods, according to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, is “the ecologically sustainable use of natural resources within their capacity to sustain natural processes, while honoring the wisdom of past generations, and ensuring that the use does not diminish the potential to meet the needs and aspirations of future generations.” In other words, it is the process of building on generational wisdom to use our resources sustainably, so that generations to come are provided for. The practice of prescribed burns, or the use of controlled fires to burn grasslands to ensure the sustainability of the ecosystem, is a chief example of Indigenous Stewardship Methods. While there has been an increase in documentation in recent years of Indigenous Stewardship Methods, it’s important to highlight that this information is traditionally orally transmitted between generations of people, and Indigenous languages often articulate values that are sometimes hard to translate into English.

A key facet of Indigenous Stewardship Methods detailed in the USDA’s guidebook is that “everything is connected: living and non-living things, air, land, water, animals, plants, humans, our ancestors and the future generations, things we cannot see and things we can see, spirits and the creator, the way we act and the way we treat the earth and other human beings.” In western science, taught in most public schools in the US, there is emphasis on division and categorization: biotic versus abiotic, plant versus animal, amphibian versus mammal. While scientific concepts like ecosystems teach the interconnection of living things, many are brought up learning to divide and categorize what we see around us in the natural world. What’s more, our society teaches us that as human beings, we are more valuable than “lesser” beings like plants. Along with other factors like technology and urbanization, these divisions and hierarchies contribute to a feeling of separation from the natural world.

However, Indigenous concepts of connectivity show a different way of relating to our environment. We can see this connectivity in action in the context of farming and agriculture. Hopi farmer Stewart Koyiyumptewa, who farms in the Hopi village of Hotevilla in northern Arizona, says, “It is not the farmer alone who grows the plant. It is the wind and animals that help to pollinate; the sun that gives warmth for growth; the rain that gives moisture for growth; and the farmer’s and people’s heartfelt prayers for just enough food to survive. It is all things.” While western science doesn’t consider rain or wind as being “alive,” these parts of our ecosystems are essential to maintaining balance, and just as important as living beings like humans and animals. Recognizing that these parts of our ecosystem are interconnected promotes a better understanding of and connection to the earth, and is important in understanding initiatives like Water Rights Advocacy, which advocates for the protection of crucial water sources, and Land Back Initiatives, which advocate for public lands once stewarded by Indigenous people to be returned to and

protected by these communities. These movements are crucial to the health of our earth and the health of Indigenous communities across North America.

Another important concept in Indigenous Stewardship is recognizing that land belongs to no one. Donald Soctomah, Maine’s Passamaquoddy tribe’s historic preservation officer, says, “Nobody ‘owns’ land. Instead, we have a sacred duty to protect it.” While land can be bought and sold according to the legal systems in place in the United States, contracts such as these really only allow a person to borrow land for a period of time. After we are gone and these intangible contracts are void, this land will continue to belong to itself. But what if we reframe our thinking, and commit to having an active relationship with the land? Indigenous Stewardship Methods teach that we have a responsibility to take care of this land like it takes care of us. This idea can lead us to a practice of reciprocity—giving back to the land as much as it gives to us, so we may be able to provide for ourselves and future generations.

The effects of colonization and US legislation have led to the loss of nearly 90 million acres, or 99 percent, of the land that Indigenous peoples once stewarded in what is now the United States. This dispossession has resulted in significant environmental damage. However, in recent decades, Land Back Initiatives have successfully returned some of this land to Indigenous stewardship. While justice is nowhere near achieved, the impact of Indigenous stewardship has become clear through a variety of studies. A 2008 report by Dr. Claudia Sobrevila, an environmental specialist at the World Bank, noted that although Indigenous people make up just 4 percent of the world’s population, they control or influence the management of 17 percent of the planet’s land, which is home to 80 percent of its terrestrial biodiversity—biodiversity that is crucial to the health of the planet and human well-being. This statistic is just one of many that demonstrates the wealth of knowledge that Indigenous communities bring to land management and stewardship.

Additionally, the UN’s Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services found that harmful environmental impacts are less severe or entirely avoided in areas managed by Indigenous peoples and local communities. As efforts to combat climate change intensify, conservationists have increasingly recognized the importance of Indigenous knowledge and leadership in protecting the environment. Despite this, Indigenous voices remain significantly underrepresented in scientific fields and unable to steward lands they once held. There is still much work to be done to return these land holdings and ensure Indigenous peoples are fully integrated into global environmental efforts.

Not Quite Almost expresses a love and reverence for the Maine’s lands that calls into conversation the Indigenous peoples who first inhabited and cared for that land. Through the principles of Indigenous Stewardship Methods, we are reminded of the deep interconnectedness of all life—humans, plants, animals, and the very land itself. Concepts like reciprocity and connectivity urge us to recognize our responsibility in nurturing the Earth, not just as individuals, but as part of a broader, sustainable relationship. While the loss of land and the continued effects of colonization have deeply impacted Indigenous communities, Land Back Initiatives offer a path toward healing, restoring balance, and fostering environmental resilience. The average person can contribute by listening to Indigenous voices, learning from their wisdom, and applying the principles of stewardship in their own lives—whether it’s through sustainable practices, advocating for environmental justice, or simply acknowledging that, as Teddy once said in Not Quite Almost, “they were here first.”

Recommended Resources

by Editors

Watch

Defending the Dark by Tara Roberts Zabriski

Lost on a Mountain in Maine by Andrew Boodhoo Kightlinger

Rural by Amelia Annen

Read

Almost, Maine by John Cariani

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Lost on a Mountain in Maine by Donn Fendler

Last Gas by John Cariani

Skeleton Crew by Dominique Morisseau

Listen

Light Pollution News podcast by Bill McGeeney

Get Involved

Dark Sky Maine, darkskymaine.com

OUT Maine, outmaine.org

Mountains of Stars, mountainsofstars.org

Maine Bureau of Parks and Land, maine.gov/dacf/parks

samantha rosentrater (aea), anD raymonD mcanally (aea) in PortlanD stage's 2020 ProDuction of alMost, Maine By John cariani. PhotograPh By mical hutson.

Portland Stage Company Education Programs

Student Matinee Series

The Portland Stage Student Matinee Program provides students with discounted tickets for student matinees. Following the performance, students participate in a conversation with the cast and crew, which helps them gain awareness of the creative process and encourages them to think critically about the themes and messages of the play.

Play Me a Story

Experience the fun and magic of theater on Saturday mornings with Play Me a Story! Ages 4 – 10 enjoy a performance of children’s stories followed by an interactive acting workshop with Portland Stage’s Education Artists for $15. Sign up for the month and save or pick individual days that work for you. Build literacy, encourage creativity and spark dramatic dreams!

Shakespeare Teen Company

In April and May of 2025, students will come together as an ensemble to create a fully-staged Shakespeare production in Portland Stage’s studio theater. Participants in grades 7-12 take on a variety of roles including acting, costume design, marketing, and more!

Vacation and Summer Camps

Dive into theater for five exciting days while on your school breaks! Our theater camps immerse participants in all aspects of theater, culminating in an open studio performance for friends and family at the end of the week! Camps are taught by professional actors, directors, and artisans. Students are invited to think imaginatively, critically, and creatively in an environment of inclusivity and safe play.

PLAY Program

An interactive dramatic reading and acting workshop tour for elementary school students in grades pre-k through 5. Professional education artists perform children’s literature and poetry and then involve students directly in classroom workshops based on the stories. Artists actively engage students in in small group workshop using their bodies, voices, and imaginations to build understanding of the text while bringing the stories and characters to life. PLAY helps develop literacy and reading fluency, character recall, understanding of themes, social emotional skills, physical storytelling, and vocal characterization. The program also comes with a comprehensive Resource Guide filled with information and activities based on the books and poems.

Directors Lab

Professional actors perform a 50-minute adaptation of a Shakespeare play, followed by a talkback. In 2025 we will be touring Hamlet to middle and high schools. After the performance, students engage directly with the text in an interactive workshop with the actors and creative team. In these workshops, students practice effective communication, creative collaboration, rhetoric, and critical analysis. The program also comes with a comprehensive Resource Guide filled with information and resources about the play we are focusing on. Directors Lab puts Shakespeare’s language into the hands and mouths of the students, empowering them to be the artists, directors, and ensemble with the power to interpret the text and produce meaning.

Portland Stage Company

Anita Stewart Artistic Director

Martin Lodish Managing Director

Artistic & Production Staff

Todd Brian Backus Literary Manager

Jacob Coombs Associate Technical Director

Ted Gallant Technical Director

Myles C. Hatch Stage Manager

Meg Lydon Stage Manager

Elliot Nye Props Coordinator

Mary Lana Rice Production Manager, Lighting Supervisor, & Resident Lighting Designer

Seth Asa Sengel Asst. Production Manager, Sound Supervisor, & Resident Sound Designer

Susan Thomas Costume Shop Manager

Administrative Staff

Paul Ainsworth Business Manager

Covey Crolius Development Director

Erin Elizabeth Marketing & Communications Director

Cassie Endicott Assistant Box Office Manager

Lake Marshburn-Ersek Audience Services Associate

Allison Fry Grants Coordinator

Aressa Goodrich Marketing and Graphic Design Associate

Lindsey Higgins Development Associate

Katie Hodgdon House & Concessions Manager

Savannah Irish Marketing Assistant

Jennifer London Company Manager, Apprentice Coordinator

Carrigan O'Brien Audience Services Associate

Stacey Salotto-Cristobol Education Assistant

Don Smith Audience Services Manager

Julianne Shea Education Administrator, Apprentice Coordinator

Adam Thibodeau House Manager

Michael Dix Thomas Education Director

Apprentice Company

Charlie Bowen Education Apprentice

Kevin Commander Stage Management Apprentice

Renata Cortés Costumes Apprentice

Sadie Goldstein Education Apprentice

Micki Demby Kleinman Directing & Dramaturgy Apprentice

Kimmarie McCrann Directing & Dramaturgy Apprentice

Larsen Nichols Directing & Dramaturgy Apprentice

Casey Pitts Company Management Apprentice

Jessica Podemski Costumes Apprentice

Sierra Riley Electrics Apprentice

Grάinne Sheehan Props Apprentice

Charlotte Teplitz Stage Management Apprentice